#communication has its place in conflict and it is before and after narrative/dramatic action!!!!!!!!

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Recently Viewed: Tomorrow There Will Be Fine Weather

[The following review contains MINOR SPOILERS; YOU HAVE BEEN WARNED!]

Hiroshi Shimizu’s Tomorrow There Will Be Fine Weather is a fascinating companion piece to the director’s own Mr. Thank You. The earlier film (released in 1936, an… eventful year in Japanese history) is set entirely on a crowded bus navigating the winding mountain paths to Tokyo, a narrative gimmick that lends the otherwise minimalistic slice-of-life story a sense of urgency and relentless forward momentum. While this spiritual successor (made in the aftermath of World War II, which obviously gives it a markedly different cultural context) begins with a similar premise, it quickly subverts the expected structure by having the vehicle break down in short order, stranding the frustrated commuters on the side of a barren, dusty road miles from the nearest town.

Despite the comparative physical inertia of the plot, Shimizu keeps the action emotionally dynamic by emphasizing the myriad interpersonal conflicts that gradually develop between the wonderfully nuanced characters. In the movie’s most dramatic scene, for example, a one-legged veteran confronts a remorseful army officer on a pilgrimage to visit the graves of the many soldiers that perished under his command—a mutually traumatic encounter that inevitably erupts into violence. In a more comedic episode, a blind masseur—who has up until this point consistently impressed his fellow travelers with his insightful observations and keen attention to detail—struggles to communicate with a deaf-mute octogenarian. And then, of course, there’s the surprising relationship between the beleaguered driver and his most conspicuously out-of-place passenger: a glamorous celebrity with a scandalous reputation back in the big city.

Running a lean, breezy sixty-five minutes, Tomorrow There Will Be Fine Weather is nevertheless packed with so much deliciously compelling material that it feels… not longer, necessarily, but certainly more substantial than its relatively brief duration would suggest. Richly textured and thematically dense, its intimacy and economy make it more genuinely cinematic than any of the superficially spectacular blockbusters currently screening at multiplexes. I’m glad that it was recently rediscovered after languishing in obscurity for almost three quarters of a century (to the extent that it was actually considered lost media before being salvaged from the vault of a studio that neither produced nor distributed it—I’m not particularly religious, but that must have been an act of divine intervention); now let’s hurry and get it on home video, where it can be properly appreciated by a wider audience.

#Tomorrow There Will Be Fine Weather#Hiroshi Shimizu#Japanese film#Japanese cinema#Japan Society#film#writing#movie review

0 notes

Text

How to Start a Story

As a follow-up to last night’s post, I wanted to offer a little bit more by way of concrete advice -- because while it can be helpful to hear what not to do (and how to subvert those problems), sometimes you just want someone to give you a concrete plan.

Unfortunately, I can’t tell you how to start your story, because I have no idea what your story is about. But I can give you some tips that will help you figure it out for your specific circumstances.

*note: I’m using Harry Potter as one example because it’s a thing most people have read, don’t @ me about your JKR hot takes. I use other examples too.

Step One: Figure out your inciting incident

What is your story going to be about? What is the main conflict? When you think about the story, what are the characters going to be spending most of their time doing? What’s it about? The inciting incident is going to be the thing that begins doing what the story is about:

In Harry Potter, the titular character attends a school for wizards. The inciting incident is receiving his invitation to that school.

In Lord of the Rings, Frodo goes on a journey across Middle Earth to destroy the One Ring. The inciting incident is receiving the ring and learning about its dark history/why it needs to be destroyed.

In Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Arthur Dent goes on a universe-saving adventure across space. The inciting incident is being whisked off to adventure by a space-traveling acquaintance.

So figure out what the story is about, or what you’re going to be spending most of that story doing -- going on a quest, fighting a demon, exploring a haunted house, falling in love.

Figure out the exact moment where that begins. That’s the inciting incident. This is a thing that happens that is a change in circumstance from who the character was before/what they used to do with their life.

Step Two: What was the character doing immediately before that?

Since the whole point of the inciting incident is that the character’s life has changed, we need to see what their life was like before that event. What were they doing?

Harry Potter was living in a cupboard, having unusual magical experiences that enraged his abusive aunt and uncle

Frodo was living a quiet life in the shadow of his eccentric uncle

Arthur Dent was trying to have a perfectly normal life (except for the jerks trying to tear down his house)

You have to spend some time establishing “normal” for the character so that we can appreciate why the inciting incident is an unusual change in their circumstances. Was the hero a farmhand before he went on this quest? Was the demon summoned by accident when five friends read a book they found in a cabin? Did the main character decide to investigate the house after seeing it every day on his paper route? Has the romantic lead been so focused on her career that she hasn’t had time for love? Who are these people, and why is this situation only happening to them right now?

Step Three: Explain exactly as much as you need to make sense

You don’t have to give the character’s entire backstory (please don’t), but you should be able to show us a decent glimpse of who this person is, what kind of world they’re occupying, and what the rules of the story will be.

Dramatize this with a scene (or a few scenes) that show some minor conflict, mystery or paradox to incite some mystery and show us what the characters are like. Establish the rules by showing them in action.

In Harry Potter, we first get a prologue showing Harry’s revered status in the wizarding community, which is juxtaposed with the people who raise him. The conflict between who he is and how he is raised is interesting.

In Lord of the Rings, we open with a spectacular birthday party celebration that shows off how strange Bilbo is compared to the other hobbits, gives an excuse for the wizard Gandalf to be there, and establishes a baseline for what hobbit life (and Frodo’s life) is like. The party is full of conflict because Bilbo flaunts social norms (even living to the age of 111 is extraordinary!) which drives the narrative in the early parts.

In Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Arthur wakes up with a hangover to discover that his house is scheduled for demolition without his knowledge, and his day is only going to get worse from there. But in order to understand that, we first have a prologue explaining some of the rules of the universe and what type of story will follow.

If it helps, instead of thinking about conflict in terms of fighting or arguing or life-or-death situations, think of conflict in terms of contrast.How can you illustrate the contrast between a character’s normal life and the life they’re about to have once this story gets rolling? How can you contrast between the reader’s expectations and the world’s reality? How can you contrast between this character and the other people in their world?

Your inciting incident should take place about 10-15% of the way into a story. The longer the story will be, the more time you can spend at the beginning getting things set up. The shorter the story, the less time you’ll spend.

Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy is 180 pages long. The inciting incident occurs on page 11, when Ford Prefect shows up to invite him to adventure.

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone is 309 pages long. The inciting incident begins on page 30, when magical letters begin to arrive.

The Fellowship of the Ring is 410 pages long. The inciting incident occurs somewhere between page 45, where Gandalf starts to explain the history of the ring left in Frodo’s possession, and page 58, where he gets around to explaining that the ring is no longer safe to keep in the Shire.

*Note: Lord of the Rings is exceptionally slow-paced by the standards of many modern readers, and characters take their sweet time in acting on this information. Even still, that 10% mark is pretty consistent.

168 notes

·

View notes

Text

Headcanon abt Prussia’s psychology and historical relationship with Poland underthe cut. I hope you like it :)

Fact: The Polish-Teutonic wars were a series of military conflicts that started in 1308 when Teutonic Order took over polish city of Gdańsk (Danzing) and annexed it (event is knows as Slaughter of Danzing). After that came the first Teutonic War, in which the Order won Pomerelia from Poland. It was the beggining of larger Polish-Teutonic conflict that lasted for over 200 years and some following wars include:

- The second Teutonic War, a conflictr that took place between 1409 (when the Grand Master declared war on Poland and Lithuania) and 1411 when the conflict ended with Battle Of Grunewald. Teutonic Order lost and had to retreat, then manage to withstand the Siege of Malbork. The Knights did survive the defeat, but they never again gained their previous influence and power, while Poland-Lithuania was established as one of main powers in Central Europe. After wiki: "Most of the brothers of the Order were killed (during the final battle), including most of the Teutonic leadership". Many Teutonic fortresses were taken over and only eight castles reminded in Teutonic hands after this conflict. - The Thirteen Years' War, when the Order's Prussian territories began a revolt against the Order and asked Poland for help. Poland was like ‘hell yeah, let me make this my problem!’ and Prussian Confederacy/Kingdom of Poland truce was created. This war ended with the Knights losing and having to give up Western Prussia to Poland. - The Polish–Teutonic War 0f 1519–1521 that ended with a treaty of Kraków - this treaty resulted in parts of Order's Prussian territories becoming secularized as the Duchy of Prussia under polish rule (4 years later). This was sealed by the Prussian Homage of 10 April. There were more conflicts between 1308 and 1521, but I don't want to write an entire book here, so I reccomend the Polish-Teutonic War site on wiki, it has a pretty comprehensive list :). So in super short oversimplified terms, as I understand it: The wars started at the beginning of the 14th century with Teutonic aggression and lasted for over 200 years, during which Poland and the Order pretty much became THE RIVALS. The turning point was the battle of Grunwald when the Order lost a lot of its power, but still had some fight in it. It ended with Teutonic Knights secularizing and becoming a vassal state to Poland. This of course completely turned upside down after Prussia became independent again, got the status of a Kingdom and pretty much whipped Poland off the map in 1700s for 100 years, so I guess Prussia never forgets (which is one of my fav HCs for him xD).

Headcanon:

So my most obvious headcanon that comes from this is the hate/hate relationship that Poland and Prussia have. I believe they really can't stand each other and view each other as enemies. Their whole history is pretty much one somehow dominating the other or attempting to dominate him - from the Teutonic Wars, through Prussia becoming Poland’s vassal and then tables turning and Prussia (& Austria & Russia) partitioning Poland into nonexistence & and the Germanization that followed, until WW2 when they also fought. It’s a pattern.

It's like they live for revenge and each revenge has to be more brutal and dramatic than what happened before. It’s a snowball of anger that escalates. And I HC that yes, all of this was seen by both of them as revenge for the previous hurts and both of them believe the other deserved it for what he did before. The difference between them is that Poland views himself mostly as the victim that fights back (due to Polish martyrology culture, which is strong in the historical nation narrative [The Christ of Nations, etc], and the general belief in the “Germanic Aggressor”) and Prussia sees himself as the conqueror who has been humiliated by someone lesser (due to his general lack of empathy for those he sees as victims, so he would never cast himself as one, he himself wants to be casted as the aggressor, as to him this position means power and agency).

Prussia can never get why Poland kinda glorifies himself as the Victim and The Martyr (an important element of Poland’s identity), as to him that makes no sense, being a victim is pathetic, right? and Poland can't understand why Prussia glorifies himself as the conqueror as to him he's just a bloody tyrant so why would you be proud of that, right?

They see value in different things to the most basic level, which makes communications very hard - and both of them see value in things that end up being destructive to them, bc both the ‘Might is Right!’ and the ‘My suffering makes me SpEcIaL!’ thinking is not healthy. They are both messed up, just differently. But the way they are messed up kinda... makes them the perfect enemies and makes it easy to escalate conflict. They fit in this very pathological way, when Poland needs to “suffer” for his national identity of the Martyr of Europe to make sense and he needs someone to cast as the aggressor, while Prussia needs to attack and conquer to see himself as the badass powerhouse of Europe he wants to be. They are like the perfect toxic relationship - they bring out the worst in each other due to their specific world-view quircks, so it kinda makes sense that their history is so bad.

But my second less-obvious headcanon is:

Prussia began the Teutonic Wars with the slaughter of Danzing because he was young, ambitious and very impulsive. Gilbert has a hot temperament and a strong desire to be active - and he did exactly that, without really thinking through the ramifications of attacking a big established country while being just a young Knights Order. You can see this on macro scale in the Teutonic Wars and on micro scale in the Battle on lake Pejpus where he charged on a frozen lake. He was so into attacking that he never even considered the environment. The thing is, this failures (and his hot temper!) almost killed him. He literally almost died due to the lost wars, lost most of his power and had to completely re-invent himself from a military crusading catolic Knights Order into a secularized Duchy just to SURVIVE and ended up under the Polish boot for years. His biggest enemy’s boot. And he needed to kneel in front of him. This is IMO an incredibly important moment for how his further development went. The Ordnung Muss Sein discipline-is-key culture and the strategic mindfulness that become a second nature to him start here, when he almost dies because of his reckless actions. It also ingrained a sense of deep humiliation connected to the Prussian Homage that only installed the need for power EVEN MORE. Before he wanted power because he hated the feeling that he is less important than Actual Counties and believed he was given unfairly bad cards by being born without land. Now tho there's an extra motive: fear. Fear of being subjugated. And revenge. This kick started the process of creation of Kingdom of Prussia as we know it - so the transition from a wild-child-Order that just went with the flow and threw himself into battle on literal iced-over lake, into a very calculating, rational thinking soldier who assesses the room and everyone in it at the moment he enters and is hyper aware of all the environment and situation that accompanies his conflicts. So I guess the short version is: Prussia is very disciplined and controls his anger very well but that's not how he always was. He’s a powerful force of nature, a wildfire, that is being reigned in by the self-imposed diligent soldier discipline in order not self destruct. It becomes his second nature, he becomes the Machine, bc if he stayed the Wild Child he started as, he would have perished and he is aware of that. So this explains why he is so merciless about his discipline and order - it’s not just a preference he has, on a more primal level it’s about survival to him. Natural tendencies still sometimes slip through, especially when he's tired, drunk or in any way vulnerable. I like to HC that you can hear the more crazy part of him when he laughs - it's such a loud, boisterous, overwhelming laughter that it does not seem to fit his cold, diligent matter-of-fact soldier-persona at all. It's bc what's inside is spilling out in the laughter. You can also see it when he parties ;)

You can also see it in violent outbursts of anger that happen when he is REALLY on edge. They are kinda scary. But most of his ‘anger outbursts’ (and wars) are calculated and planned to get his way with minimal consequences. The truth is, he feels like he failed himself whenever he really looses control.

My other HC about Gil as Teutonic Knghts can be found here, here, here and here if you like my rambly takes :)

#aph prussia#gilbert beilschmidt#hws prussia#hetalia#aph poland#aph lithuania#hws poland#Axis Powers Hetalia#historical hetalia#hetalia headcanons#aph#hetalia world series#feliks łukasiewicz#queque

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

My email to Failbetter Games

I rarely see a reason to hide my motivations or actions. I don’t have a lot of regrets in life, because as I got older- I’m 34 now- I came to understand that it’s pointless. Try to learn, grieve things like lost friendships and loved ones as best you can, and be the best person your emotional and physical state allows you to be.

Anyway

To that end, I thought I’d air out my grievances to FBG in a rather long email. It was a long time coming as I wasn’t convinced emails would do anything. Elias on the Failbetter Community discord server suggested I at least try, and I spent a week of proofreading to make sure I was as courteous as I could manage to be despite my feelings. I’m angry, angry because this game was so dear for me for so long and it feels like the current team has taken it in a direction so much in the opposite of what I find fun.

That anger is unhealthy, of course. Art evolves. Bands change their sound because they get bored or they want to make money tapping into a new audience. Painters refine and improve their style. Writers improve the range of their vocabulary and change tone. Everything shifts in this world. The healthiest thing to keep in mind is the fact that the thing you loved was there for that point in time and nothing can take that away from you, from your favorite game as a child to your favorite bands in your teenage years, you’ll always have those moments of joy.

I want to hold onto this moment of joy that I experience with Fallen London as long as possible, so I wrote this email in the hope of convincing them to alter their direction so I can enjoy it a little bit longer. Except for the signature that contained my real name at the end- not that it’s hard to find if you care, as my facebook url is /tranderas- the text is unmodified. Hopefully this shines light on what I want.

What I don’t want is discussion about my needs. This is my place to explain, to vent, to point people to instead of typing everything out every time someone asks. But enough stalling.

___

Hello, I was encouraged in a Twitter interaction to write in and expand on my thoughts on the game so I figured I would do so now. Since I started writing this email before reading the December balance announcement, I'll address that at the bottom. The sparknotes version of what I'd like is as such: More content in London itself (especially socials), more Zee destinations, a profession uptuning, a fundamental rework of the deck that goes beyond favors, and a non-docks favor buff. From most to least important, the things I'd like to see addressed are:

1. The lack of endgame content within London itself is concerning to me for two reasons:

a. I play FL because it is a social electronic game, and I want to stay in zones in which I can continue to do social interactions. This is the reason I stay in London rather than going to Iron Republic and Port Carnelian, my first and second favorite zones respectively. If I wanted a story rich solo game I'd play Sunless Sea; if I wanted an analogue experience I'd play Blades in the Dark or read one of the books that influenced FL's style.

b. I simply don't like the mechanics of lab or parabola or how they gatekeep content. Because of this I haven't had any free content to pursue since the release of the new heists, and for a much longer length of time before that.

2. I'd love to see the remaining tier 3 professions given something they can do at lodgings. In general I prefer buffs instead of nerfs, especially in story games, and think it would be silly to nerf midnighter/correspondent/crooked-cross downward. Instead, give the others roles, perhaps in special options in the 4/5 card lodgings.

3. With the changes to Paramount Presence and the BDR power creep Notability has been significantly de-emphasized. I'd like that changed. To me the notability grind had the best balance of difficulty to cost-benefit analysis to end reward in the game, and while overcapping removed that, I would like something to use it again to make going above 10 worthwhile more often. Recent BDR items should make going even beyond 15 possible for very lategame players.

4. In addition to more endgame content within London, I'd like more midgame content at Zee. Sunless Sea got me especially interested in Frostfound and Irem, and a roleplay point for my OC is that she'd like to quite literally punch Mt. Nomad to death. Please don't feed us to spiders, though. The ones in London cause enough sorrow.

5. I would enjoy more free spouses that are not seasonal, and more ways to interact with player spouses. Again, it's a social game, and it makes sense to reward a desire to be social with the community. On the other hand, the NPC spouses in the game are limiting in their roleplay potential to the point that I've created a character around the Esoteric Accomplice for one of my OCs to get involved with between one roleplay relationship and another. Now allow me to take a deep breath while I discuss the proposed balance pass. The short version here is that I think it's wrong to release a deck refresh nerf without a fundamental change to what cards appear in the deck, and that the nerf to docks favors and yet another nerf to revs favors is misguided.

Here's the long version: I actually support a removal of the deck refresh mechanic. I got in trouble for calling flash lay resets an exploit on a private Fallen London fan server, and refused to use it until the lab convinced me it was a mechanic intended for use by FBG.

The widespread use of deck resets isn't a problem in its own right; rather, it's a symptom of how fundamentally broken the deck is in its current state. You have cards that are so bad that the narrative acknowledges they're awful and the mechanics give you a way to get rid of them at the cost of objectively worse lodgings. You have story signpost cards that clog up space held by desired cards. It can be nearly impossible to get Portly Sommelier (before deck refreshes i was getting one a month playing 60 actions a day) and dream qualities (my PoSI-ready SMEN alt has DbW3 playing every dream card that comes around). And most lodgings have cards that are objectively bad in a way that no new player can know without reading the wiki or asking someone- the exact problem you claim a desire to address in your announcement.

It's telling that players will do SMEN- a quest chain ostensibly about how much you're willing to sacrifice to some faceless maybe-god- in order to get rid of bad lodgings. I personally only bought back salon (Notability grind), rooftop shack (3 epa wine option), and bazaar premises (5-card potential plus good certifiable scraps/money option) after Trand got St. Beau's Candle, and JanieS only ever got the bazaar premises, her Remote Lodging, and the Orphanage. Even the other 4-card lodgings are only good under specific circumstances, and the rest of the 3s have worse cards with no endgame benefit.

Tranderas and JanieS both use remote lodgings. Trand is stuck with the Advertisements of a New Venture and Devices and Desires cards in his hand. Advertisements is an Abundant-rarity card. Since I have no intention of doing railroad due to disliking its mechanics the card simply sits in my hand. If I discard it, its rarity means it pops back up quickly. I think a way to opt out of story signpost cards such as aunt and railroad would be good progress toward solving the deck problem. There could be a large action or monetary cost involved with both removing it and reactivating it to balance, but without a way to get rid of these story hooks I need to keep refreshing to draw other cards around them.

As for the favors, I consider that part of the change mostly good. However, the docks favors -> Silk expedition doesn't really compete that well with other endgame grinds at the moment. Further, the Revolutionaries favor turn-in was already reduced dramatically this year, and I don't think it needs further tweaking. Rather than tuning docks and revs down, I would prefer to see the other factions tuned upwards, and the cost of earning favors eliminated from their cards (no 10 rostygold donation to the Church, for example). I'd still like to see the faction cards remain in the deck after they're given storylet sources, but made more rare, with the conflict options getting a boost to remain attractive in line with my proposed buff to payouts as they are good for London from a flavor/narrative perspective. In closing, it feels like the current FBG's team has a vision for the game that doesn't mesh well with how I see it and want to play it. Content has consistently moved away from what I want to do, leaving me with only SMEN and cider as goals to pursue (and as mentioned, I've run two characters- Samia R and Tranderas- through the quest chain to its completion). I obviously care about the game enough to want more things I like or else I wouldn't bother writing and proofreading this post or discussing and debating changes on the community discord, so I hope you'll take these opinions and suggestions into consideration moving forward. Regards,

Tranderas

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

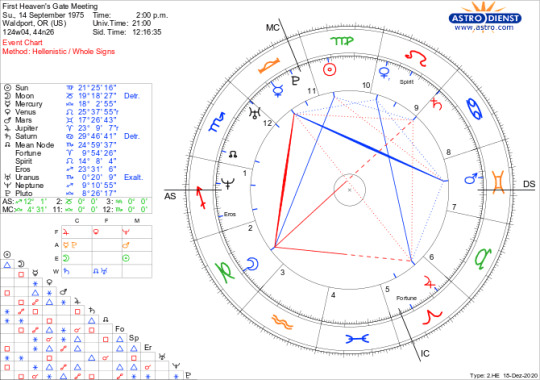

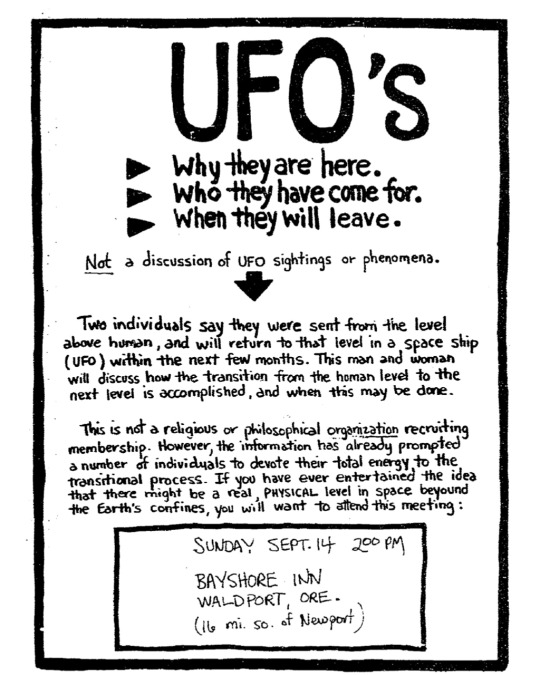

Some thoughts on the natal chart of Heaven’s Gate

William Lilly (b. 1608) popularized the natal chart as a reflection of the individual, but ancient astrology was utilized more as a lens for global (relatively speaking) events like war, agricultural cycles, weather, and the longevity or character of royal dynasties. I love looking at charts in general but I especially enjoy thinking about events’ inceptions as individual narratives that are socially metabolized. Stories jump out of event charts differently than they do from individual charts. If you are someone who considers your own birth chart or the charts of others, make sure also to explore the dates of different events in your life (books, films etc are also fun to examine in this way). Any moment you select is subject to the same archetypal cast of symbols as is an individual life.

This is a bit Aquarian in the idea that we can examine the social through a zooming out from or the collapsing of individual psychologies into macro, mythic surfaces. In keeping with Aquarian themes, I watched a bit of the new Heaven’s Gate doc last night. I wouldn’t say I’m fascinated by cults etc etc, but I can’t help responding to a birth time, and Heaven’s Gate has one! For me this is an ideal reading, where most of what I know about Heaven’s Gate is largely through osmosis. It wasn’t until after watching some of the first episode that I learned that the buildup to what we consider the culminating event was actually ~20 years in the making. I have not studied the progression of--or figures central to--the movement. Some people do their best work when they are immersed in research of a subject; I myself tend toward flash or impressionism, so I want to capture this phase before I continue watching the documentary.

RISING NEPTUNE IN SAGITTARIUS

I’m thinking of this placement less as a moment of inception (the way we might read it in the chart of an individual, as the experience of separation from the body of the parent, becoming a discrete entity) and more descriptive of the way we might encounter the cultural phenomenon of Heaven’s Gate at first glance. It may feel rooted in occultism or obscurity—Sagittarius carries notions of philosophy, education, intellectual magic; I’m thinking of The Magician card and its depiction of a single figure controlling all the elements, convening heaven and earth in their alchemical process of discovery. We often characterize movements as centering around a single idea, or a powerful persona, as with Charles Manson or Jim Jones, but there is always a larger atmosphere to examine. Neptune asks us to look beyond superficial characterizations of events in order to understand their mundanity in equal measure to their mystique. Foucault refers to all research as archaeological in that it is a type of unearthing or excavation, a making-sense of objects that may no longer exist and so deliver not direct answers but different articulations of fragmented meaning. What is important too is that Neptune may represent the illusion of origins and root causes. From Stalker (1979), “I dig for the truth, but while I do, something happens to it.” Obscurity is not dispelled, but re-oriented.

CAPRICORN MOON IN 2ND HOUSE opposite SATURN IN CANCER, 8TH HOUSE

We might think of the moon as the id or the unconscious. Liz Greene describes the difference between the sun and the moon as the difference between aspiration and unconscious emotional need—the former describes an active mode of attainment or embodiment, while the latter is a pulsing lack to which one cannot help but respond. The moon is in detriment in Capricorn, in mutual reception with Saturn, who also experiences detriment in Cancer. This opposition is uncomfortable—the emotional needs are difficult to meet. This difficulty may describe the dispositions of those drawn to the Heaven’s Gate movement; Cancer in 8th may describe one who doesn’t feel “at home”—like the Gnostic subject, who pledges allegiance to the god of an entirely different realm, and must suffer alienation in this realm as a result. The moon’s placement speaks to an unsettled sense of self, a need to strive or work toward a comfortable psychological situation. This moon does not “have enough”—not necessarily in a material sense, but they do feel dispossessed, as if their history and culture do not belong to them, or they do not belong to the history they have been given.

ARIES JUPITER IN 5TH HOUSE

The 5th house speaks to creation, production, a making manifest. What Heaven’s Gate purported to give was a way forward—a strategy, a directive. It doesn’t take particularly complex analysis to guess that for the emotionally listless or dislocated, this resolve would have been seductive. Joan Didion’s collection, The White Album (1979), describes this generation far more incisively and expertly than I will attempt to do here; instead, picture the Aries Jupiter as striding confidently forward without fear, of translating subjective experience into universal understanding, resulting in decisive action. This was not just an idea, but a way to manifest one’s presence in the world; not just about joining a collective, but about using the language of collective experience to articulate higher individual selfhood.

GEMINI MARS IN 7TH TRINE LIBRA MERCURY + PLUTO IN 11TH

With two Geminis exiting the White House next month, it feels important to acknowledge the more toxic stereotypical Gemini qualities at play in tearing the country apart for the last four years (though of course the foundation for such a conflict is deeper-rooted and further-reaching than a single presidential term, as it is unrealistic to attribute the momentum of such movements to simply a demagogue). The Trump argument for a stolen election is one element of what has been described as “mass political disinformation.” Gemini cares less about the truth, and more about how a truth is expressed; less about the effectiveness of an idea, and more about being pleased by its shape. And they won’t be pinned down, held to anything they’ve previously said, if in some later context that thing no longer serves them (if you watch enough Bob Dylan interviews you’ll see what I mean—don’t ask him about folk music, don’t ask him what he believes, don’t ask him where he’s from—if you never tell the truth, then it’s almost like you’re never really lying, you’re just saying things, creating momentum through language).

We can see this stereotype on the one hand as, yes, members of Heaven’s Gate were lied to and manipulated. Gemini’s ruler, Mercury, is a slick operator in Libra. Libra quells doubt, seals holes, soothes unease—all the dynamics involved in the appearance of equilibrium or social harmony. We can see Mercury’s conjunction with Pluto as the god of communication acting in service to the god of death. The rhetoric of Heaven’s Gate is designed to ease its members toward radical sacrifice. The 11th house speaks to communities, groups, friends—the social world, and, in this case, social organization and purpose.

The 7th house is the house of the Other, and is where we may look in an individual’s chart to read their close 1:1 relationships. It would have been important for Heaven’s Gate to discredit the friends and families of their members, to emphasize that these are the people that the members should no longer trust and confide in. The Gemini stereotype here, of manipulation and dishonesty, is projected onto the Other—a Them—to consolidate the self, an Us. Mars here makes the disconnection from loved ones particularly dramatic. Mars wants to cut, to define, to separate; it is the individuating act. It is also worth mentioning Lynn Bell’s description of Mars as the protector of the moon, of the unconscious; if the moon feels threatened, it is Mars who steps in and takes over. If an increased involvement in Heaven’s Gate results in members’ loved one’s questioning their involvement, then it is the deep-seated sense of alienation (the moon) that is heightened, ameliorated by a severing of ties (Mars). If Gemini speaks to duality or two-ness, Mars is about making that division manifest.

LEO VENUS IN 9TH

The 9th House in Hellenistic astrology represents temple work or religious duties, and so for readings of individuals alive today we typically adapt this meaning to describe academic or professional institutions, but here we can really embrace the ancient associations. This is absolutely how the institution of Heaven’s Gate represented itself—transparent, loving, and in loyal service to the good, and to the happiness of its members. The “gate” itself feels as if it refers to a 9th house structure (thinking of heaven elsewhere described as a “kingdom”), with Venus at the threshold guiding members toward an embrace of institutional values. I haven’t looked at the charts for Ti and Do, but it feels significant that they are “the Two”—a platonic pair whose relationship forms the wellspring of the movement, which feels very Venusian. We might place The Lovers card beside the card of The Devil, and see the same figures in both cards. The Lovers’ equivalent in the zodiac, of course, is Gemini.

VIRGO SUN IN 10th

If the moon is the id, the sun is the ego—the conscious experience of the self, the path that is chosen, the disposition by which the self feels most connected to worldly perception. The 10th house, “the crown you wear,” positions the ego identity of Heaven’s Gate; what it thinks it is, as a public organization that is meant to efficiently serve its members—to construct and carry out a plan. It is interesting to think of Virgo and Scorpio on either side of Libra, two weights in balance on the scale; this also describes the Persephone myth, in which Virgo descends to the realm of Scorpio and returns with divine knowledge, incurring the changing of the seasons; whose being is intricately tied to the rotation of the earth. Virgo’s responsibility, then, is to bear the fate of the world in their minute actions. Heaven’s Gate in this way positions itself as serving humanity through a practical, incremental system, which relies on everyone “doing their part.”

SCORPIO URANUS IN 12TH

To me it is difficult to find more aptly conflated synonyms for death, unless maybe you replace Uranus with Pluto. Uranian matters are dramatic, revolutionary. They speak to transformative change—as does the 12th house, as does Scorpio. This placement imbues Heaven’s Gate with such an inevitability of death, but the kind of death that is cosmically resonant in that it has the power to change how death in this context is understood. This 12th house, “the bottoming out,” feels like a reservoir that feeds into the Sagittarian Neptune, the sediment that must be continuously re-worked or rediscovered in whatever form it takes in its periods of hibernation. Neptune in Sagittarius may represent the fossilization process of Uranus in Scorpio. I may have more to say about this once I finish the documentary, but I am looking forward to watching for impressions of how “death” is constructed, or re-made as an artifact of social, extraterrestrial liberation.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

McFarland, USA (2015)

In Hollywood, certain sports have dominated the sports genre. The proportions reflect their popularity as Hollywood’s Studio System reached its zenith. America’s national pastime, baseball, is well represented. As is boxing, which was once arguably one of the United States’ favorite sports alongside horse racing. American football and basketball had been underrepresented until the last few decades; soccer and ice hockey – perhaps given the demographics of the average Hollywood executive past and present – have not gained much traction among major movie studios (how I hope that changes soon for soccer, but among all the sports I have mentioned, it is the hardest to “fake”). Track and field and distance running occasionally have their moments, like Chariots of Fire (1981) and Race (2016). Simulating amateur or professional running comes down to correcting an actors’ running form – a far cry from teaching someone how to kick a soccer ball properly and strenuous boxing training.

McFarland, USA, directed by New Zealander Niki Caro (2002’s Whale Rider, the pandemic-delayed live-action adaptation of Disney’s Mulan), is the first Disney live-action film on a track and field/distance running story since The World’s Greatest Athlete (1973) – a film that slathers on the slapstick and the cultural stereotypes. Set in the small town of McFarland in California’s Central Valley, McFarland, USA looks at a community glanced over by Hollywood and independent filmmakers. A few hours’ drive from Los Angeles and the Pacific Ocean, McFarland is an agricultural community that is heavily Latino, with limited economic opportunities for its residents. That, of course, makes McFarland and places like it the butt of derision from some of its residents and those who do not know any better. It can be a difficult place to live, but even here, the film says, Americana thrives and the American Dream abides.

In the late summer/early fall of 1987, football coach Jim White (Kevin Costner) loses his job at an Idaho high school after losing his temper, accidentally injuring a smack-talking player. He and his family – wife Cheryl (Maria Bello), elder daughter Julie (Morgan Saylor), and younger daughter Jamie White (Elsie Fisher from 2018’s Eighth Grade) – pack their belongings and settle in McFarland, California. Even on their first day, the Whites are frightened of their new home. The place is unkempt, and it is difficult for the daughters to believe they are in America. Jim takes his new job as assistant football coach and PE teacher at McFarland High School, but is soon stripped of assistant coaching duties after a dispute with the head coach. Noticing how many of McFarland’s boys are excellent runners, he convinces the high school principal to support boys’ cross country running – the first year it is sanctioned by the California Interscholastic Federation (CIF, the governing body of California high school sports).

The team, some more skeptical than others, assemble: Thomas Valles (Carlos Pratts), Jose Cardenas (Johnny Ortiz), Johnny Sameniego (Hector Duran), Victor Puentes (Sergio Avelar), and brothers David (Rafael Martinez) and Danny Diaz (Ramiro Rodriguez).

When one thinks of the word “Americana”, certain things come to mind. Small towns with everybody knows your name and white picket fences, children playing baseball in the park, and the corner store/malt shop are elements of Americana, exported to the world via films and television shows made in the United States. But these images are specific to an America of an earlier, more monochromatic time and is arguably geographically specific (not reflecting the diverse Southwest, let alone Alaska and Hawai’i). The country, no matter the time period, is too large to distill into a single idea.

McFarland, California of the late 1980s looks a lot like what it is today. Instead of burger joints, there are taquerías. Quinceañeras are celebrated; there’s a group of men who get together to cruise their classic cars through town (they are mistaken by the White family as “gangbangers” their first night there); and much of the population works throughout the week picking fruits and vegetables in the fields – work that is backbreaking, sweltering, honest, essential.

What makes McFarland, USA most appealing is its normalization and celebration of life in McFarland. Though dramatized, the cinematic reality of this film’s McFarland, California is largely the reality for small agricultural towns up and down California’s Central Valley. The narratives of McFarland deserve to be considered as “American” as equally those from Bedford Falls (1946’s It’s a Wonderful Life), the middle of nowhere in Iowa (1989’s Field of Dreams); and Greenbow, Alabama (1994’s Forrest Gump). Conflict and personal discontent always simmered in these places, despite the idyllic community in Bedford Falls (minus Mr. Potter) and the natural beauty of the middle of nowhere in Iowa and Greenbow, Alabama.

Those things exist, too, in McFarland, California. Jim White, in his first days at McFarland High, obviously does not want to be there nor does he plan on staying longer than he needs to. In forming and coaching cross country, he contends with the familial, economic, and other cultural factors facing his student-athletes’ lives in addition to learning how to coach a sport he has no experience in. As the film reaches the end of its first act, the screenplay by Christopher Cleveland (2006’s Glory Road), Bettina Gilois (Glory Road), and Grant Thompson (his screenwriting debut for a feature film) strays from the White family to show us the familial and peer pressures the student-athletes face. Here, McFarland, USA captures the vulnerability, confusion, friendship (or lack of it), and desire to forge one’s own fate that high schoolers can easily identify with. Many sports movies focusing on a team rather than a single person would allow those individuals to be dramatically indistinguishable (a major problem in 1986’s Hoosiers, a personal favorite). That is not the case in McFarland, USA, which allows its young Latino characters to occupy their unique niche in this film. Thus, in conjunction with its normalization of McFarland’s heavily Latino culture, the film becomes a rousing slice of Americana. Certain people who might be defensive over what “Americana” entails might find issue with what I just wrote, but their definition is exclusionary by default.

With a white coach named White (if this was a professional sport, headline writers for sports sections might be having a field day) training and mentoring seven Latino cross country runners, some people might dismiss McFarland, USA outright as a “white savior” movie even though it avoids such trappings. The “white savior” narrative is one where a white character enters a difficult situation created or exacerbated by the personal/sociopolitical/cultural qualities of a non-white character(s) – the former, by exemplifying traits unlike the latter’s, rescues the non-white characters from that situation. The term “white savior” originated from academic analyses of narrative art and has passed into the political liberal vernacular. Too often among political liberals, the label of a “white savior” narrative is enough to dissuade certain individuals from even considering to consume such a narrative – this reviewer is guilty of using that term in a dismissive fashion.

McFarland, USA circumvents the tropes of white savior narratives by framing Jim White as a flawed character, its post-first act glimpses at life among the boys’ families, and White’s attempts to understand the lives of his student-athletes and neighbors. White, who comes off as an impersonal and stubborn ass with a short-fused temper at first, is played wonderfully by Costner. His character learns, through cultural and neighborly diffusion, how those qualities fail to resonant with his student-athletes, their elders, his wife, and two daughters. Over time, he learns more about the boys’ lives and – on his own volition – the difficult work their families tend to. He acknowledges their personal and familial sacrifices, acknowledging that his hardscrabble life is fundamentally different than theirs. In a final pep talk before the inaugural CIF state championships for cross country, White says:

Every team that’s here deserves to be, including you. But they haven’t got what you got. All right? They don’t get up at dawn like you and go to work in the fields… They don’t go to school all day and then go back to those same fields… These kids don’t do what you do. They can’t even imagine it… What you endure just to be here, to get a shot at this, the kind of privilege that someone like me takes for granted? There’s nothing you can’t do with that kind of strength, with that kind of heart.

It is a beautiful moment made possible by the acting from all involved. That though someone like Jim White may never understand the poverty or the anguish that comes with these boys’ lives, their dedication and work ethic is equal to, if not surpassing, that of their affluent counterparts. To whom much is given, much is required. Jim White has given the boys his dedication to themselves as athletes, students, and human beings; the boys of McFarland’s cross country team have given to their coach lifelong respect and the embrace of community.

As a sports film, McFarland, USA is neither innovative nor does it shake off the coil of predictability that almost every sports film is plagued with. Quite a few of its elements are simplified and sanitized (White revived a cross country program that had been dropped rather than establishing it, he also revived the girls’ cross country team that is not depicted at all here, among other things) but that might be expected given the studio (Disney) behind it. But this film is based on a real story and hews as closely as it can to the spirit of the actual story when it can. If I saw the pitch for this film without any prior knowledge, I might have dismissed it as fantasy. McFarland High School’s boys’ cross country team won nine state championships under White until his retirement in the early 2000s, and qualified for consecutive state championships from 1987 to 2013.

Prior to Jim White’s pre-meet speech, there is a montage set to “The Star-Spangled Banner” – commemorating the boys’ brotherhood now linked inextricably with their coach. The attendees’ and athletes’ singing gives way to a solo guitar, showing the audience scenes of that brotherhood. We see the team on a late afternoon run just outside the barbed wire fencing surrounding the prison located near their school. After that run, we see them, talking with their coach amid the crepuscular Central Valley sun, taking a moment to catch their breath. They are all sitting and relaxing atop a tarp-covered mound of almonds ready for market. If that isn’t an example of Americana at its finest, I don’t know what is.

My rating: 7/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. Half-points are always rounded down. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found here.

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, click here.

#McFarland USA#Niki Caro#Kevin Costner#Maria Bello#Morgan Saylor#Carlos Pratts#Elsie Fisher#Johnny Ortiz#Hector Duran#Sergio Avelar#Michael Aguero#Rafael Martinez#Ramiro Rodriguez#Christopher Cleveland#Bettina Gilois#Grant Thompson#My Movie Odyssey

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ok, ok, Hieron wrapup notes, pending epilogue

Hadrian: Strengths and problems of Hadrian’s arc are for me aptly summarized in the jump from 1) Hadrian eking out a moral victory of sorts over Samot and the gods at the not inconsiderable cost of taking judgment into his own hands one last time---it’s all well and good to talk about Hadrian being in no position to pass judgment, but then, he wasn’t with Jericho, either, and sending Samot to Aubade is not a neutral choice. Of course no neutral choice exists! and the important thing is he no longer considers himself a mere weapon in the hands of a higher justice, but a person making a decision, which (as it turns out) simplifies the decision exactly as much as being a weapon did back in the day.---to 2) Hadrian cracking a joke about how, if his wife and child were hurt, of course he would pursue Samot to hell and back. Hadrian the family man exists, conflict-free, on a planet of eyewatering sentimentalism. I don’t really understand why. It has something to do with how they chose to handle Hadrian’s “redemption” or anyway recuperation as a character capable of normal communal life, after what I guess we’re now supposed to understand as his antisocial spiral in s1---laugh with me, it’s good to laugh---with his somber diagnosis of Samot as having spent Too Long Away From His Family also applying to his past self. Um.

Of course Hadrian was never intended as a reliable narrator, but it’s hard for me to do much with that when his narrative isn’t countered by anything else in the text; we meet Benjamin and (less often) Rosana in other contexts, but we don’t get their view of Hadrian, much, and when we do it hews to a narrow pattern of concern and exasperation, as if Hadrian were only an aging action hero this close to claiming his retirement benefits. They lament his recklessness but seem not to notice the dogmatism or the listless doubts that replace it. (That’s with the fact that doubt, if anything, makes him a worse husband and father.) Despite her often-stressed importance to the surviving followers of the church, Rosana’s religious feelings are largely a cipher, and she’s almost never in a position to witness or comment on Hadrian’s most dramatic struggles with faith. So “family” and “faith” remain separate, unable to complicate or inform each other. It’s a shame, because I theoretically am really charmed by the story where a man’s incrementally degraded---not even broken!---faith is the mechanism of his salvation, and by the end he and Samot have swapped places, Samot incapable of not pursuing bitter, futile, barbarous justice and Hadrian very relaxed. The problem for me is that Hadrian ironically restored to his devout family through heresy is never treated as the strange accomplishment it is, and it’s not something he has to work for; I know we get Benjamin scenes this season, I understand the narrative function is to gesture to the very thing I’m describing, but I don’t mean “work for” in the sense of “carving out more time for family dinners.” I mean “acknowledging and accounting for Hadrian’s failings,” rather than glossing his escape almost as a matter of removing the temptation of belief, problem solved.

Hella: I’m in a similar place with Hella; I like the skeleton of her complete arc, I don’t think it ever got the development it needed and it’s missing some key connections. I got a lot of joy from Ali affirming the thread of Hella’s relationship to Ordenna, from s1 avoidance to s2 voluntary exile to s3 final, reluctant return and assumption of responsibility. For me, it’s compelling to look back and realize that Hella essentially begins in a place that Hadrian only reaches circa Winter: having not rejected, but unobtrusively fled, a culture which failed to inculcate her completely with its horrible values---in part because she was too cowardly to adopt them---but that left her with a tangle of blind prejudice and bravado, the relief of freedom making her that much happier to perform “big tough Ordennan,” as long as she stayed far away from Ordenna. I love... of course I love Velas, in concept, I love and will always love FATT’s shitty compromise cities, cosmopolitan and democratic of necessity rather than out of any high ideal. Yes! We get it! I imprinted on Terry Pratchett, I don’t need to say it every time! But the fact that Hella identifies with Velas and befriends Calhoun in Velas and that they have this common experience of “shit, maybe the world is a bigger place than I realized, maybe it’s not actually a choice between tyranny and anarchy every time” ... makes me really verklempt. And in Nacre they both fall back on old habits and Velas barely seems real; for both of them, Nacre has an unpleasant tinge of “reality” asserting itself over a dream---for Calhoun, returning there is obviously something he’s always feared, but for Hella it’s the discovery that the Ordennan state was more right than she knew, that gods and magic exist, and aren’t just bogeymen used to keep Ordennans off the mainland; and, on a deeper level, that Ordenna’s narrow pride is a reaction to a far older and more arbitrary authority.

So she kills Calhoun---“If she’s going to, then why don’t I?” Escape is so unlikely, caught between Ordenna and Nacre, that helping others find it would be a frivolous proposition: the only person Hella hopes to save is Hella. Then she goes home to learn that Velas is also in mortal danger, that the whole world will soon be Ordenna (and Nacre.) She’s ensured it. No wonder her nihilism at the start of Winter is much more marked, and she finally starts to accept that escape isn’t there for the seizing, that there isn’t an outside.

And then she... goes to Aubade?

This is where it starts to break down for me, as with Hadrian and his family. In theory, I get why actually showing Hella what it means to live away from savage god-eat-god imperialism gives her the courage and vision to face Hieron head-on. I think the line about “surrounding herself with clever people” is great and gets at the point that her education, her personal growth, are not meaningless just because they’re the product of artificial intervention, fantastical prosthesis. But, I dunno, in execution it’s so spotty. Part of it is that Adelaide has to come to her senses at the same time, but that process happens very quietly and never gets free of Hella’s orbit---the scene where she asks Hella for a reason to leave Aubade is good, but comes at the price of other scenes in which we see them, for example, negotiate the terms of Adularia’s existence together. Hella as Death’s Servant reads too much as "running Adelaide’s errands,” not enough as her ardent champion, and I’m not saying that every Ali character has to become a zealot before they’re done for me to be satisfied, but hey! If this is you redeeming Nacre and its ideals from the start of the show, then redeem those things! And give Hella the space for her return to Ordenna to feel like atonement, rather than “one last job”... it’s such a good atonement, is the thing, the only possible one, because for all that she’s changed, Ordenna is still the one place where you can imagine Hella Varal having something to teach people.

Probably the solution to this would involve triangulating with the sentience of the Anchor; since Ordenna got the plans from Nacre, Adelaide should take partial responsibility in the cleanup there, as well, and not only in releasing Hieron from the curse. Keep the two plots in conversation to the end. But I’m not sure what exactly that would have looked like; something with Hella’s new body, maybe.

Fantasmo: I love Nick. Thanks to Nick for half-assedly speedrunning Fantasmo through Fourteen’s bit of “in lieu of character development, what if: uplifting character regression?” I cracked the fuck up at him using “Dominate” solely to make Samot captive audience. Audience... to the world’s most insipid power-of-heart lecture, which was honestly very sweet as an obvious truth Fantasmo once knew, or knew well enough to mouth. I did love all the grace notes about the Last University in the finale, still nameless, still a refuge.

#seasons of hieron#spring in hieron#friends at the table#happy deathday to hieron congratulations on becoming: discworld

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

I apologize if this comes off as a rude question to a Killian fan, but I think you’d be the best person to answer in a real and logical way: Do you think, given what we know of how the series went, Killian’s character arc might have ended better had he either died from the Excalibur wound or if he had been allowed to maintain his heroic sacrifice at the end of the Dark Swan arc? Not necessarily ‘would he be better off dead than married’, just whether those would’ve been more Him.

Woo boy nonny, you’re out for my life today, aren’t you? xD

OK arggggk ok this is complicated for me bc those two ‘death points’ are very different imo, and also have different implications depending on how close to the story you’re zooming in. For the purposes of this, I’m going to focus on the Camelot death from the Excalibur wound.

On the purely ~*~i’m love him~*~ level, of course I’m rather dang pleased that he didn’t die…permanently in either of those scenarios. I’m always pleased to get more of Killian on my screen. Even if the situations leave me feeling frustrated, I think that he’s a character that’s complexly written enough and well acted enough to be someone I can enjoy picking apart in any scenario.

So OK dealing with both of these scenarios I think you can tackle this from a few different viewpoints (and I hate to always go back to this, but it’s literally like the fundamental way my brain works, so I’m gonna kind of be flirting with those ideas the whole time). Looking at the situations as if I were imagining all the characters in the story to be real people? I think it’s clear what the characters wanted: in the case of the Excalibur wound, Killian would rather have died while helping free his friends than Emma turn him into the dark one, and expressed that clearly. In the case of his death at the end of the Dark Arc, he chose death in part as a way to free everyone from the fate he’d doomed them to, but also to eradicate the darkness once and for all. Because of Rumple’s failsafe, that choice was predicated on false circumstances, and so the idea of Emma going to bring him back, and him not wanting to stay dead as long as everyone else was safe, makes more character sense and is more of a plot point to get everyone to The Underworld. Because the first is more character based and the latter more plot based, I’m gonna focus my attention on the first.

If we’re talking about the character arcs? It’s hard. Basically the way that I would approach that would be “how fruitful were these events in catalysing character progression and growth” and as I’ve said in other posts, I don’t think they—especially the Camelot death—were fruitful at all, and in fact were regressive. This is going to focus mainly on CS in 4-6 as that’s pretty much what I see those events and their value enmeshed with (and, as I’ve stated before, IMO nearly all of Killian’s S4-6 interactions are filtered through CS anyway, so I think it’s appropriate to talk mostly about CS here) and bc I’m a lengthy ho it’s going below the cut.

The thing I had loved about CS was that during the S3 build up to their actually entering a relationship, the relationship was set up to challenge both of their character weaknesses. For Killian, his weakness centres around his desire for freedom and agency (for himself or others), when challenged, leading him to close himself off and/or make pretty shitty and harmful decisions. For Emma, you have the fear from the trauma of abandonment leading her to isolate herself, or sometimes not even enter decisions as to not present the opportunity for abandonment.

So the S3 push-and-pull of Killian giving the reins of the relationship to Emma—stepping in as support when her life or familial relationships were at risk, yes, but in their interpersonal relationship, letting her evaluate him and move at her own pace—addressed both of their weaknesses. Killian explored the vulnerability of willingly giving up control of a situation, and Emma, by going at her own pace, was able to evaluate his steadfastness and begin to trust him for it.

And that was the dynamic that each needed in that moment, and why early CS is still in ways compelling for me — if I ignore the follow through. Because the problem with the two “deaths”, as far as I see, is that they follow this pattern of taking that previous dynamic, and digging in the heels and exaggerating it to an unhealthy level, instead of exploring how the two characters heal together and adopt a new dynamic. The important thing in that push-and-pull exchange is the agency both characters have in it — however, you start to see what, in my opinion, is Emma assuming Killian’s willingness to follow her lead is given, which removes his agency from the exchange…and the narrative starts to romanticise it.

I think you start seeing it from the beginning of S4 with Emma getting angry at Hook when he doesn’t do as she says and stay put with Elsa in 4x03. We get insight into both of their mindsets during the confrontation at the end – Emma is terrified that she’ll lose him and that’s the reason she orders him earlier; he, used to being dynamic, struck out on his own in response. But the point we got by the end of the episode wasn’t that she was right, but that she was expressing her valid fears irrationally by trying to tell Killian to do what she said, no questions asked. And he was wrong in that he didn’t counter a demand he didn’t agree with right away and directly, but took back his agency behind her back when he should have communicated that he had a problem with what she was asking. So you have the unhealthy level of the dynamic being played out, handled poorly, and a set up for forward motion into healthiness being presented.

Except it never really followed through—oh it did in dribs and drabs, which makes this so much more frustrating (their conflict over his holding back information about Ursula, and then the resolution they come to together being one positive move I can think of where they’re venturing more into equal partner territory), but overall the idea of Killian’s capitulating to Emma being a given instead of a choice is the theme that continued—to its unhealthiest apex in S5, with the Dark One arc being the dramatic climax of Emma assuming Killian’s eventual compliance and overriding his agency with her own desires, and Killian, when confronted with being controlled, going to harmful extremes.

And, what that should have done, and what I thought it was doing at the time, was to drag that increasingly issue-laden agency problem out into the harshest light, to the most extreme situation of life or death, and create maximum drama over it so that it could reach a resolution both through character interaction and plot resolution. So that going forward, you would have the two entering into a more communicative partnership and presenting a united front (and negotiating how to navigate what that means) against whatever conflict showed up next (insert forever bitter I NEVER GOT MY FUCKING BATTLE COUPLE face here), or deciding to step back and change their dynamic by moving away from presenting a romantic unit.

But what happened was more of the same, except this time it was treated by the narrative as being just part of their relationship’s standard operating procedure, part of the new ‘normal’ after the major conflict of S5, and not as a problem to be solved. It was romanticised. So you end up with S6 which makes me just want to fling myself into the sun with rage. Lies about the saviour premonitions are Emma taking agency away from not only Killian but everyone around her — it’s the same story all over again, ***walls*** so it’s OK, but no one has the agency to react and to help her because she doesn’t allow it. And as it relates to CS, you don’t get Killian’s reaction to this at all except in sad looks (and That Fucking Cut Scene That Shouldn’t Have Been Cut).

You get a redux of 4x03 with Killian hiding the shears as a way to try to reclaim some agency behind Emma’s back, because she’s shut him out of any solution they could have reached together as partners. But the narrative focuses on what he does as the only grave error of the situation. You have the agency problem embedded in the first proposal – from going through his private things that trusted as a safe hiding place, to her instigating the proposal over his coming to her for help — but this time, unlike in the Camelot situation, her actions aren’t called into question by the narrative, but his immediately very much are both by her at the character level, and at the narrative by isolating him on the realm-hopping extravaganza. Her taking away his agency is very literally romanticised in a proposal.

You have it again right before the wedding with yet another lie to cut Killian off from being able to actively step back to or to step in and help her as her supposed partner — and again, this time the narrative frames this not only as the act of a hero, culminating in her solo take-down of the Black Fairy (with her family literally frozen out of supporting her), but it actually intersperses her actions of lying to him to force him act as she alone thinks is right in with the build up to their actual wedding. Not only does the narrative not call her actions into question, they’re literally put into the most romantic of contexts. The question at that point is never whether or not Killian will follow Emma’s lead, because the relationship never moved past the S5 conflict of Emma assuming he would and acting on his behalf, except unlike in S5, this isn’t portrayed as a relationship weakness, but as Emma’s strength of character, and their romantic apex.

So that comes back to the death question. And my returning question: narratively what was the payoff?

It’s not that from a story standpoint I think that Killian’s character arc was finished when he was dying from the Excalibur wound — for me it’s that, if that moment is a pivotal moment crafted to show the height of agency imbalance in the only real relationship he has on the show in S4-6, then it should have been addressed and resolved with a pivot in dynamic after the dramatic fallout — with the characters either moving together or apart.

As it stands, the dynamic stagnated and regressed so badly into that stagnation that the whole issue that the “death” brought up, with the extreme violation of agency and resulting trauma of S5, was angst for angst sake without resulting growth. Without a complete overhaul of the plot from that point out where CS either grow together or apart due to the consequences of that moment, I tend to view that moment when he’s begging to die in the Middlemist field as just a deeply sad one, now made the sadder for its pointlessness. It’s harbinger of the future unchanging and then utterly romanticised removal of his agency within the relationship continuing through the end of the series. The shower of resulting S5 angst affects his character/relationship arc through S6 about as much as a fridging would have anyway, and it’s really bleeding hard for me to side against the character’s wishes knowing all that in retrospect.

(that said, to reiterate, as a killian fan, i am glad he stuck around? but i’m also glad i get to live in a world where there’s a him that didn’t go through that depressing stagnation? ugh HI YEAH!)

#Anonymous#ouat critical#cs critical#emma swan critical#killian jones#mabsplaining#killian jones meta#I DON'T KNOW LADS#moar tags? pls let me know#lol basically the way i look at it now i'm like -- honestly shit or get off the pot.....or die i guess?#and there was a whole lot of narrative constipation going on there

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

No Honour by Awais Khan

No Honour

Awais Khan

Orenda Books

Publication Date: 19 August 2021

Through the fictional story of Abidi and her father Jamil, Awais Khan presents many of the societal difficulties encountered in everyday life both within rural and urban Pakistan. This is a novel routed in love and loyalty which convincingly makes a case for social change and greater equality within his homeland.

This book commences with a tragic sequence of events which demonstrates how traditional attitudes towards family honour have compelled men to do what would normally be considered unthinkable acts to their own relatives. The impression this gives to the reader is an emerging comprehension that normal life for inhabitants of small countryside communities within Pakistan includes a large degree of fear and suspicion of their neighbours.

This opening highlights how behaviours are monitored through the village elders known as the jirga. Led by Pir Saqid there is danger implicit for anyone who is perceived to break their fundamental interpretation of Islam. Reading this book at the same time as the news was coming through about the Taliban retaking control of Afghanistan, there were definite parallels. As Khan’s poignant narrative reveals to us, the majority of men in the village appear to support the actions and beliefs of the elders, domestic violence against women is very common and perhaps sadly girls in the village do not go to school and cannot read and write.

Living modestly within the village is local butcher Jamil. He is in his mid forties and married to Farida and they have seven children. Their eldest daughter is sixteen year old Abida. She was born quite a few years before the couple were able to conceive again so she is several years older than her two brothers while her sisters are even younger. As his first born child, Abida is the apple of her father’s eye. His deep love and admiration for his daughter is genuine and shines through the novel. He bestows much more attention to her than the rest of his family but he also turns a blind eye to her worrying behaviour. Unlike Farida who is preoccupied with the younger children, he is aware that his eldest is spending a lot of time away from the family home.

No Honour has two narrators with chapters alternating between Jamil and Abida so we get both their perspectives. This is key to the novel as by virtue of their different gender and generation we perceive how both are conflicted between the behaviour expected of them and their own personal attitudes and desires. This reveals a lot about Pakistani society and reveals that while the traditional attitudes are deep routed, they live by their own moral codes.

Abida is able to escape the fate that has befallen some of her peers in the village and the focus of the story moves to the busy and bustling city of Lahore. After leaving the village behind Abida hopes to feel safer but soon realises that there are many more threats in the city. She has also put her trust in a weaker person who is unable to resist the temptations that life in the city brings.

While Abida has been liberated from the deadly motives of the jirga, without the security of her family, her life takes a dramatic downward spiral. Khan immerses us in each development in such an emotive fashion as if each step is painful to write. The only hope for Abida is that somehow the fleeting acquaintances that she has made can somehow lead her father Jamil to her and rescue her from her increasingly desperate ordeals.

Jamil does arrive in Lahore once the family grow concerned at the lack of contact from their daughter, but he is wholly unfamiliar with the city and the lives lived by its residents. Through his viewpoint we encounter a range of characters from different social statuses. An exciting thriller develops where cultural norms are approached and challenged leading Abida to eventually confront her greatest fears. Encouraging by the waning appeal of the jirga, she is then eventually able to contemplate what differences she can hope to bring.

No Honour succeeds in so many ways as a compelling and informative work of fiction. Through Khan’s dialogue we have an exceptionally strong story about family love that is very relatable and believable. The novel also reveals so much about what is good and bad in contemporary Pakistani society. If you read No Honour, I can promise you will be constantly engaged by words that will provoke a range of emotions from sadness, despair and fear to anger and finally, most importantly to hope. The onset of modernity takes place at different stages around the world but there is a realisation that through education and increased awareness the radical interpretations of what is a peaceful religion are no longer legal nor durable. In addition to being a convincing novel, No Honour can be seen as Awais Khan’s tool to bring greater awareness to western audiences of the daily challenges faced in his part of the world and perhaps some inspiration directed towards the domestic market. Without doubt the future must see more liberal attitudes prevail, self interest diminish and a more positive future for Sharmeela’s generation.

Many thanks to Orenda Books and Anne Cater for an advance copy of No Honour and inclusion on the book tour. Please check out the other reviews of this book as shown below.

Awais Khan is a graduate of the University of Western Ontario and Durham University. He is also an alum of Faber Academy. He is the Founding Director of the Writing Institute and has delivered lectures at Durham University, American University of Dubai, Canadian University of Dubai to name a few. He has appeared on BBC World Service, Dubai Eye, Voice of America, City42, Cambridge Radio, Samaa TV, Indus TV, PTV Home and several other radio and TV channels. His work has appeared in The Aleph Review, The Hindu, The Missing Slate etc.

He is the author of In the Company of Strangers (published by Simon & Schuster, The Book Guild and Isis Audio) and No Honour published by Orenda Books.

0 notes

Text

2. Inspiration from competition #competitoranalysis

This campaign is influenced by campaigns and strategies employed by various "competitors" who have successfully expanded their interests and outreach online.

The key strategy of creating viral content to market one's music is inspired by Jacob Collier and Lil NasX. They have both successfully established a professional career and a large fanbase through a 'grassroots' approach of advertising their music and brand through short homemade clips that are popular with audiences online (Feldman, 2021) (Pearce, et al., 2021), as opposed to a more 'traditional' approach which relies on studio quality media advertising supported and sponsored by labels with large financial resources (artists like BTS and Harry Styles are two prime examples who have found success through this technique). There are two main rationales behind choosing a grassroots approach. Firstly, Tenzin does not have the backing of a label or large financial resources to produce and commission professional quality advertising, and therefore must resort to more accessible means. Secondly, this grassroots approach helps initiate the 'genuine' and 'personal' relationship that Tenzin seeks to establish with his fans, the medium of homemade videos helping create an intimate and authentic relationship with his fans. Although having a similar campaign strategy to NasX and Collier, Tenzin's end product that is being sold, which is his music, is unique to him which allows his campaign to stands out from the two competitors'.

Going viral or creating engaging content that can penetrate through the noise on social media, however, can be incredibly difficult (Bigne, et al., 2021). This is why the campaign also takes inspiration from popular influencers or content creators who make videos that go viral frequently. Zach King and Noah Requel are two prime competitors/inspirations who have been selected among the millions of creators who Tenzin needs to compete with to attract and retain attention from online audiences.

After studying hundreds of these creators and viral videos, I have observed that they all employ these key features, knowingly or unknowingly, to create compelling content:

1. Attractive

The first few seconds of a viral video always has an attractive introduction. Whether it is dramatic or unusual scenes, title cards with unique phrases or a person simply announcing that they are going to do something peculiar, the viewer is placed right in the action, drawing their attention and keeping them in suspense.

2. Engaging

The video uses several technical elements of audiovisual storytelling, often unique to this medium, that keep the viewer engaged with the content on the screen. Fast cuts, music, narration, closed captions, video effects and emojis are often used to create dynamic experiences for the viewers and keep them from turning away.

3. Entertaining