#coastal sagebrush

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Sphaeralcea munroana (Munro's desert-mallow)

Munro's desert-mallow is native to dryer areas of the Great Basin in Western North America (sagebrush country). Vancouver is classified as coastal rainforest and you have to know what you're doing to make it prosper in this much wetter environment. This is what I love about botanical gardens; not only do they expose me to flowers that I can't grow in my back garden but, thoughtfully, they label these exotic species so I know what to call them.

#flowers#photographers on tumblr#Desert-mallow#orange#UBC Botanical Garden#fleurs#fiori#flores#blumen#bloemen#Vancouver

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from this story from The Revelator:

At first glance the hills and valleys covered in coastal sage scrub oak are little more than a featureless green swath. On closer inspection, however, you can recognize it for what it truly is: the beating heart of one of the most genetically rich ecosystems on the planet. Birds, insects, mammals, fungi, and even some other plants find refuge under the boughs of coastal sage scrub oak, while water drawn up from its deep roots spreads out to sustain ground-dwelling organisms.

Species name:

Coastal sage scrub oak or Nuttall’s scrub oak (Quercus dumosa)

Description:

The coastal sage scrub oak rarely grows more than about 7 feet tall, but it can spread outward a great distance thanks to its lateral branches and multiple trunks. The trees’ small, spiny leaves emerge in the spring soft and bright green, but gradually toughen and darken to a dusty dark green by summer. Their acorns tend to be thin and elongated, almost conical.

Where it’s found:

The coastal sage scrub oak, as its name implies, is found along coastal areas in Southern and Baja California. The full extent of its range is the subject of spirited debate, as it shares many similar physical characteristics with other scrub oaks found more inland. In San Diego County, the remaining populations of coastal sage scrub oak exist in fragmented populations, usually in wildlife reserves, like islands in a sea of urban development.

IUCN Red List status:

Endangered

Major threats:

Urban development destroyed much of this tree’s habitat, and its remnant population still faces this threat, along with several others. The introduction of grasses and other highly flammable nonnative species, like eucalyptus, have increased fire frequency and intensity. Escaped ornamental plants and grasses can outcompete oak saplings for light, space, and water. And climate change is resulting in disruptions to precipitation, which stresses all populations.

My favorite experience:

While collecting tissue samples after a spring rain, I took a moment to look at the tracks imprinted into the soft ground. Animal prints were everywhere — mule deer, raccoon, fox, opossum, roadrunner, and what I hoped were those of an exceedingly large bobcat and not a mountain lion. I rarely saw any of these animals during the day but, thanks to the rain, it was clear that they were all around me — present but hidden within the oaks.

My favorite experience:

What I could see, however, were the many birds flying from tree to tree, reminding me of fish swimming among outcrops of coral. Insects buzzed all around. Galls created by tiny wasps were starting to grow from some of the oaks. By summer, some of these galls would grow to the size and color of a peach, bobbing slowly in wind scented with wildflowers, sunbaked dust, and sagebrush. I knew that under my feet deep roots reached toward the precious groundwater that would sustain the forest during the dry season, and spreading from those roots were mycorrhizal fungi that would work with the oaks to support each other.

I grew up among the firs, cedars, hemlocks, and maples of the Pacific Northwest. I always thought forests needed to be composed of tall, majestic trees christened with carpets of rolling moss. Yet this sea of small, scraggly oaks held so much life. My perspective grew. It’s one thing to read about this ecosystem and another matter entirely to truly see it and understand how precious it is.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tidepools of La Jolla, California – Nursery of The Pacific Ocean Marine Life - Torrey Pines, California – San Diego Pacific Ocean Beach Adventure

youtube

To the north and east of the beach Los Peñasquitos Marsh Natural Preserve is one of the last remaining salt marsh areas and waterfowl refuges in southern California. The marsh, coves, and tidepools are rich in sea life: limpets, shore crabs and hermit crabs, mussels, barnacles, sea anemones, and many species of snails and cast-off shells.

This is the perfect place to watch the annual gray whale migration. All year round, you can see Seals, dolphins, porpoises, and sea lions in the ocean. About two hundred species of birds are protected at the reserve, including migratory ones.

Year round Resident shore birds include brown and American white pelicans, black-bellied and snowy plovers, American avocets, western sandpipers, willets, whimbrels, sanderlings, great egrets, and longbilled curlews. Occasionally, visitors may see gray foxes, bobcats, coyotes, and mule deer. Reptile residents include rattlesnakes and various other snakes and species of lizards, including the endangered horned lizard.

The Torrey Pines 2,000-acre reserve contains about 300 endangered and protected species of native plants. These vanishing habitats are home to sand verbena and beach primrose on the beach, as well as California sagebrush, California buckwheat, black sage, and coastal barrel cactus. On the cliffs other high elevations there are many chaparral plants, including chamise, manzanita, ceanothus, California scrub oak, toyon, and mountain mahogany. Many of these scrub plants in particular provide the refreshing herbal fragrance that mixes so incredibly with the ocean breeze.

Before this area was colonized by Spain, the Kumeyaay tribes migrated lived here, and migrated between here, the deserts, and the mountains throughout the seasons. The land was bountiful, and the Kumeyaay would have fished, hunted, collected crustaceans, and gathered seeds, fruit, roots, to create probably a very healthy and tasty diet. The Kumeyaay have left an indelible archaeological and cultural legacy here in San Diego county and they continue to be a strong tribal nation today both here and south of the border in Baja Norte state.

The water is usually so clean and clear here, and because of the lack of shoreline development, and the underwater marine reserve, this constantly ranks as one of the 3 cleanest beaches in SoCal. This is a wonderful rare instance of extremely valuable real estate, both being a wildlife refuge and habitat, and a beautiful escape from civilization for people to enjoy for the most part in harmony.

It’s been an incredible day on the coast here in Torrey Pines and La Jolla, and I’m so glad that we were able to explore my favorite beach together. You can enjoy my series: Torrey Pines – La Jolla, California – San Diego Pacific Ocean Beach Adventure, full length, 3 glorious days on the North County coast, and experience all of the different moods and landscapes from the ever-changing interplay between the coastal inversion and sunlight.

youtube

Full Length Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eLyySza85jA

Thank you so much for joining me for this adventure in my favorite beach town on the west coast, the gem of the San Diego coastline, La Jolla, California. It means the world to me to be able to share my treasured slice of heaven in the summer heat with you, and thank you so much for watching, upvoting, commenting, and subscribing.

All the best,

William Z. Brennan & Desert Mountain Apothecary

Please Enjoy Anza Borrego Desert Wildflower Superbloom – We had the most incredible wildflower superbloom in the California Desert this past year, join me from the beginning of the cold winter through the waves of dazzling blooms to the hot end of the season.

youtube

Web: https://desertmountainapothecary.com/

Medium: https://desertmountainapothecary.medium.com/

Mastodon: https://mindly.social/@DesertMountainApothecary

Spoutible: https://spoutible.com/DesertMountainApothecary

Pinterest: https://www.pinterest.com/desertmountainapothecary/

Reddit: https://www.reddit.com/user/desertmtnapothecary/

Tumblr: https://www.tumblr.com/desertmountainapothecary

Please Enjoy More Videos!

Supreme Superbloom! Anza Borrego Desert Spring Wildflowers! - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jGDPHEmN3v8

Grateful Desert Ocotillos - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bstybc3XcAk

Coyote Canyon Offroad Adventure! - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WQYPvqj2ouU

Julian & Santa Ysabel, CA Epic San Diego Backcountry Road Trip- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r2Z_o0S4Hpg

Bellport in Spring - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_J9hzsFhS-k

Santa Ysabel Preserve – Backcountry Hiking - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2XLrSJMLXUw

#youtube#california#southern california#beach#travel#la jolla#socal#north county san diego#san diego#ocean#Tidepools#Tide Pools#Tide-pools#Marine Biology#nature

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

32, 42?

32. Is there a smell that reminds you of your childhood?

Sagebrush! I grew up in coastal California, and the the coast sage scrub, especially after rain, smells like home to me!

42. Do you have a favourite swear word?

I like them all. I love to use words other than shit and fuck when something goes wrong though. I live to stub my toe and yell "Cock!" I trip and fall and yell "Piss!" It's just nice to say a bad word.

I grew up in a household where we really didn't swear (well, my dad did, but my mom was extremely against it). So I learned how to swear as an adult. It's a fun hobby.

Random Ask Game

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love the intermountain west I love being able to wander in and out of the mountains and deserts and sagebrush steppe and work with wildlife. It is NOT just Mormons and evil ranchers ffs and there are so many queers from so many walks of life here and if another coastal lib/queer tells me I need to move to a coast I am going to lose my goddamned mind. The folks here are fighting tooth and nail and the strongest and best queer communities I know are in Utah and Texas and North Carolina because they have to be.

USAmericans: This pride month, talk to the queer people who actually live in all those bad evil icky red states and find out what it's actually like, how we actually feel about it, and who here is actively fighting against it. No more telling us to "just leave" or reducing us to innocent victims who are "trapped" here. There are so many of us and we live here for so many reasons, none of which should be justified. We are resilient, we are powerful, and we are fighting against the fascist laws working to eradicate us or scare us away. Being trans in a red state right now is in and of itself an act of resistance. That being said, pay attention to the brave souls on the front lines, pushing against the laws, making good trouble, and refusing to be silenced.

I won't let myself be talked about like I'm stupid to live here.

I won't let myself be talked about like I'm a helpless victim who's trapped here.

If you can't join the fight by standing beside us, then the least you can do is empower us, amplify our voices, and pay more attention to the ones who are FIGHTING AGAINST THESE LAWS than you are to the chucklefucks trying to pass them.

23K notes

·

View notes

Text

What happens to birds when it's smoky outside?

New Post has been published on https://petn.ws/GmXgu

What happens to birds when it's smoky outside?

Last summer, Carrie Brown-Kornarens spent 10 minutes every week observing birds in her Los Angeles backyard and at nearby Griffith Park. Brown-Kornarens, a ceramicist with a background in graphic design and animation, looked and listened closely for birds amid the coastal sagebrush, scrub, oak and walnut trees. She was already collecting data for a local […]

See full article at https://petn.ws/GmXgu #BirdNews

0 notes

Text

Watching a streamer I like compose music, and its paintin such a picture in my head I wanted to save it.

Magenta fades into peach into pale pink into blue as the clouds whisp in. They dont roll, but start as light little whispy things that just chase each other across the early mornin sky colliding until they build up into a dusky puffy cloud that hides the pink behind it, causing the surrounding sky to pale further in comparison as the cloud grows darker and whisps out, spreadin slightly as it dissipates and a light sprinkle early mornin sunshower starts. the edge of the large cloud fuzzes and dissipates, with a whispy playful nature loosing its clean edge as the rain slowly falls on coastal scrub mountains, bringing for the scent of creosote, sage and petrichor washing away the dust and enhancing the various subtle shades of green found in the desert from the waxy evergreen of some of the shrubs to the velvet grey green of the sagebrush, to the yellow green and cream of the yucca and the soft blue green of a succulent. The dirt beneath slowly drinking in the winter rain, revealing all of the different shades of brown from a deep dark grey that turns into the best kind of mud to play in, to a rich red brown full of clay, to a sparkling pale tan as water runs down a rock face accenting the quartz and mica, causing them to sparkle in the sun. and above it all, the clouds continue to chase and build and spread across the sky, over the land, bringing depth to a new day.

#from the desk of the minister#my writing#feelin poetic i suppose#clouds#jonosmithers#man's streamin and the music is doin nice things in my brain

0 notes

Text

The Mountain Topography Surrounding Hollywood, California

Tours of Hollywood Sign and More

Hollywood sightseeing tours all include spectacular (and cost-free) views of the surrounding mountains (the famous Hollywood Hills) but just how much do you know about the topography of this part of the city of Los Angeles?

The vibrant city of Hollywood, California, renowned for its glitz and glamour, is nestled in the heart of Los Angeles County. Beyond the bustling urban landscape, Hollywood is enveloped by a picturesque mountainous terrain. This article explores the fascinating mountain topography surrounding Hollywood, providing insights into its geology, prominent peaks, recreational opportunities, and the breathtaking views they offer to residents and visitors alike.

Geological Background

The mountainous landscape around Hollywood owes its origins to the complex geological history of the region. The area lies within the southern portion of the Santa Monica Mountains, a range that stretches approximately 40 miles parallel to the coast of Southern California. The Santa Monica Mountains are part of the Transverse Ranges, which were formed by the tectonic forces of the Pacific and North American plates. Over millions of years, uplift, faulting, and erosion shaped the mountains we see today.

Prominent Peaks

Several notable peaks dot the mountainous terrain around Hollywood, offering stunning vistas and recreational opportunities for outdoor enthusiasts. Mount Lee, crowned by the iconic Hollywood Sign, is a prominent feature that rises to an elevation of 1,708 feet. Griffith Observatory, situated atop Mount Hollywood (1,625 feet), provides breathtaking panoramic views of the cityscape, the Pacific Ocean, and the surrounding mountains. Another prominent peak is Cahuenga Peak (1,820 feet), located within Griffith Park, offering commanding views of the San Fernando Valley.

Recreational Opportunities

The mountainous landscape surrounding Hollywood provides a haven for outdoor activities and recreation. Griffith Park, one of the largest urban parks in the United States, offers an extensive trail network for hiking, jogging, and horseback riding. The popular Griffith Observatory and its surrounding trails provide opportunities for both nature exploration and stargazing. Runyon Canyon Park, located just south of the Hollywood Hills, is a favored destination for hiking, with trails offering panoramic views of the city and the Pacific Ocean. These mountains also attract rock climbers, who can challenge themselves on the steep cliffs and boulders that punctuate the landscape.

Flora and Fauna

The mountainous terrain surrounding Hollywood supports a diverse array of flora and fauna. Chaparral, characterized by drought-tolerant shrubs, dominates the landscape. Common plant species include California sagebrush, toyon, and coastal sage scrub. The mountains are also home to a variety of wildlife, including deer, coyotes, bobcats, and numerous bird species. Protected areas within the mountain range, such as the Griffith Park Nature Reserve, ensure the preservation of these natural habitats.

Breathtaking Views

The mountain topography around Hollywood offers breathtaking views that have captured the imagination of artists, photographers, and visitors for decades. The panoramic vistas from Griffith Observatory showcase the sprawling cityscape of Los Angeles, the glimmering Pacific Ocean, and the silhouettes of neighboring mountain ranges. Atop Cahuenga Peak, one can marvel at the sweeping vistas of the San Fernando Valley, extending to the majestic Santa Susana Mountains. These awe-inspiring views serve as a reminder of the natural beauty that coexists with the vibrant urban setting of Hollywood.

youtube

The mountain topography surrounding Hollywood adds a natural grandeur and serenity to the bustling cityscape. From the iconic peaks like Mount Lee to the panoramic views from Griffith Observatory, these mountains provide a refuge for outdoor enthusiasts and a source of inspiration for those seeking respite from the urban bustle. The diverse flora, fauna, and recreational opportunities within this mountainous landscape create a unique juxtaposition with the glitz and glamour of Hollywood, enhancing the overall charm of the region.

0 notes

Text

I think the issue is that the landscape of the non-coastal PNW isn’t unique to the PNW.

So apart from specific geological features like the Scablands, the sagebrush is indistinguishable from generic cowboy gothic

No horror media has used the true potential of the PNW as a setting since everyone is fixated on mossy doug firs and not sagebrush. Go east of the cascades for a real sense of dread

#don’t get me wrong I am the Great Missoula Floods’ number one fan#that shit is mind-blowingly cool#but it is not sufficient to weight the region’s balance away from a unique biome

190 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was tired of living in a "dead" area.

I was stuck on the idea that "nothing grows around here" and "everything is dead." I was convinced that there wasn't any life here.

I was wrong.

I finally went out today to try and identify different plants I could find growing wild. I found...

Horseweed...

Telegraph weed...

A pear tree (planted by one of the first settlers here)

Coast live oak (also planted by the settler)

Pecan trees (settler)

Australian salt bush...

Alkali mallow...

Seaside heliotrope...

Tree tobacco...

American black nightshade (yikes!)...

And so so so much more! Tumblr mobile will only let me post ten pictures at a time. There's so much living here. I was so ignorant to think it was dead. I even found white horehound and sacred datura.

So I guess the lesson here is, if you feel like you don't live in a good place for Witchcraft™... Look again! Put in some effort to SEARCH for witchy things and different resources available to you!

#witchcraft#plants#wildlife#nature#botany#green witch#chaparral#coastal sagebrush#inland empire#southern california#work with what you are given

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cool times. 🦌

#chaparrals#yucca#oak#sagebrush#white sage#fungi#white horehound#broomsage#buckwheat#black sage#sage#hiking#wildlife#horehound#shrubs#coastal sage scrub#plants#botany#biodiversity#california biodiversity

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Species: Wolves (Canis)

This series focuses on helping people choose interesting species for their fursona through informing them of the many, often overlooked, species out there! This post is about wolves.

──── ◉ ────

Species:

Red Wolf (Canis rufus)

Size: 66cm (26in) height (at shoulder), 121cm (4ft) lenght, 20-36kg (45-80lbs)

Diet: carnivorous, preys on deer, small mammals

Habitat: coastal prairies, marshes, forests

Range:

Status: critically endangered/endangered

──── ◉ ────

Eastern Wolf/Timber Wolf (Canis lycaon)

Size: 63-91cm (25-36in) height (at shoulder), 160cm (5.5ft) lenght, 23-30kg (53-67lbs) weight

Diet: carnivorous, preys on deer, large herbivores

Habitat: deciduous forests, coniferous forests, mixed forests

Range (in blue):

Status: imperiled/threatened

──── ◉ ────

Coyote (Canis latrans)

Size: 58-66cm (21-25in) height (at shoulder), 76-86cm (2.4-2.8ft) lenght, 6.8-21kg (14-46lbs) weight

Diet: omnivorous, preys and scavenges small mammals, deer, livestock, insects, carrion, berries

Habitat: varied, sagebrush-steppe, forests, prairies, deserts, savannahs, alpine meadows, temperate ranforests, urban

Range:

Please note, the coyote has 19 subspecies!

They all have small but interesting variation, and can vary in size quite dramatically. If you'd like a coyote fursona, I recommend checking them out! The picture above is of a mountain coyote (Canis latrans lestes)

Status: least concern

──── ◉ ────

Grey Wolf (Canis lupus)

Size: 80-85cm (31-33in) height (at shoulder), 100-160cm (3.2-5.2ft) length, 23-80kg (50-176lbs) weight

Diet: carnivorous, preys on large ungulates, small mammals

Habitat: varied, temperate forests, mountains, tundra, taiga, grasslands, deserts

Range:

Please note, the grey wolf has 38 subspecies (the above pictured being eurasian wolf, Canis lupus lupus)!

Of which I would like to highlight:

Arabian Wolf (Canis lupus arabs)

Arctic Wolf (Canis lupus arctos)

Mexican Wolf (Canis lupus baileyi)

Also, please note the grey wolf comes in a variety of colors, regardless of subspecies

Status: least concern

──── ◉ ────

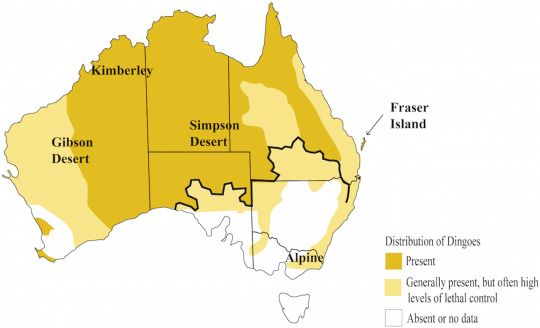

Dingo (Canis dingo)

Size: 52-60cm (20-23in) height (at shoulder), 120-150cm (3.9-4.9ft) lenght, 10-15kg (22-33 lbs) weight

Diet: carnivorous, preys on small mammals, livestock

Habitat: varied, spanning all if Australia

Range:

Please note, the dingo's taxonomic classification is debated - you may find it also listed as Canis familiaris, Canis familiaris dingo, or Canis lupus dingo

Status: threatened

──── ◉ ────

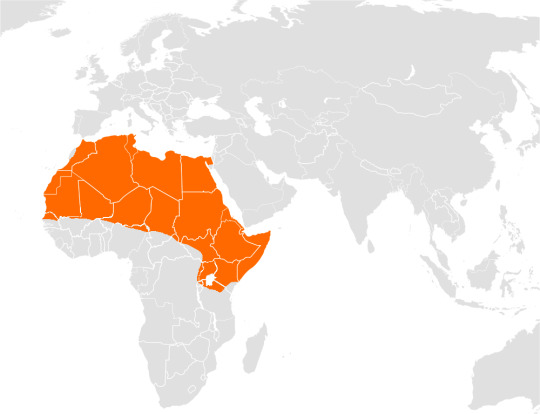

African Wolf/Golden Wolf (Canis lupaster)

Size: 40cm (15in) height, 7-15kg (14-33lbs) weight

Diet: Carnivorous, preys on small mammals, small reptiles, ground-nesting birds, insects

Habitat: mediterranean, scrublands, forests, savannahs

Range:

Please note! The african wolf has 6 subspecies!

Status: least concern

──── ◉ ────

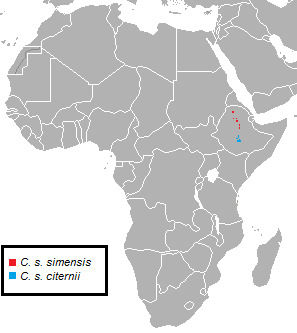

Ethiopian Wolf (Canis simensis)

The Ethiopian wolf has 2 subspecies:

Northern Ethiopian Wolf (Canis simensis simensis)

Southern Ethiopian Wolf (Canis simensis citernii)

Size: 53-61cm (20-24in) height (at shoulder), 100cm (3.2ft) lenght, 11-20kg (24-44lbs) weight

Diet: carnivorous, preys on small mammals

Habitat: afroalpine grasslands, heathlands

Range:

Status: threatened

──── ◉ ────

Golden Jackal (Canis aureus)

Size: 46-51cm (18-20in) height (at shoulder), 69-84cm (27-33in) lenght, 8-11kg (18-24lbs) weight

Diet: omnivorous, preys and scavenges small mammals, small reptiles, ground birds, fish, insects, fruit

Habitat: open savannahs, deserts, arid grasslands

Range:

Please note! The golden jackal has 7 subspecies!

Status: least concern

──── ◉ ────

#fursona resources#species#furry#fursona#mammals#canidae#canids#canis#wolf#wolves#red wolf#timber wolf#coyote#grey wolf#dingo#african wolf#ethiopian wolf#golden jackal

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

There is a Nez Perce name for condors: qu’nes (distinct from the word for the turkey vulture, q’ispa’laya, a similar bird locally differentiated by its bent wing profile). And the great bird historically lived here, in the Palouse Prairie, Hells Canyon, and the inland Pacific Northwest along the slopes of the Northern Rockies. The bird was here not during some lost ancient “primordial” Pleistocene past, but recently; the bird lived here relatively few decades ago. “California” condors living quite far from California. These local names for were relayed to scholar Brian Sharp, and there are other condor-names from the Pacific Northwest (also recorded by Sharp). There is a Wasco word for condors, k’unwakshun (according to scholars of the Warm Springs’ Wasco language program, distinct from the word for turkey vulture, q’ispa’laya), evidencing the bird’s presence at the Dalles, along the inland Columbia River, and in the Blue Mountains. From near the sagebrush steppe east of the Cascades, a Yakama word: patsami hu’u, “rough or crooked beak” (according to scholars of the Yakama Cultural Center). There is lakessltl’nos, possibly the word for condor, which is distinct from the turkey vulture, hem-letet (”stinkhead,” according to Johnson of the Grande Ronde Tribe Cultural Affairs Program). Condor bones exist on islands in the Salish Sea. Sonny McHalsie Naxaxalhts’i (researcher of cultural heritage and Salish place names) identifies a Salish Sto:lo name for condor from the Fraser River: sxwe-xwo:s, “opening his eyes.”

The “official” story as reported in most literature from settler-colonial land management agencies is that condors disappeared from the Pacific Northwest before the 20th century. There are records, even from the mid-20th century, of condors glimpsed flying over the Cascades in the Pacific Northwest, sometimes far from the coast.

Why are Native observations of condors -- from the Pacific Northwest as recently as the 1950s and 1960s -- generally ignored?

Because of the locations of the last remaining populations of the bird (the Grand Canyon, Mojave Desert, canyonlands of southern Utah, and southern California), condors might be associated in popular consciousness with arid landscapes and deserts. A distribution map of where condors survive in the 21st century would give the impression that the bird is associated solely with California deserts of the so-called “American Southwest”. (The Hopi Cultural Office references a Hopi name for condor, kwaatoko, “big eagle.”) But as recently as the early 1800s, the bird apparently still lived all along the coast between the deserts and chaparral of Baja California, past the foggy redwoods forests, to the Garry oak savanna of Vancouver Island, the Gulf Islands, and the Fraser Delta of present-day Vancouver, on the edges of rainforest and beneath the Pacific Northwest’s glaciers.

-------

During the early Holocene, the California condor apparently lived across the mountains of western North America (and perhaps some birds traveled father eastward into the continent, with Pleistocene fossils found in Texas and elsewhere). But in recent centuries, condors seem associated with the Pacific coastline (maybe similar to how the bird’s counterpart, the Andean condor, lives in a narrow corridor along the Pacific coastline of South America, which shares the climate and environments -- including chaparral, temperate rainforest, and desert -- of the coast of North America, at mirrored latitudes). Early Russian colonizers, traveling from the Aleutian Islands and Alaska towards northern California, reported the condor along the shores of the North Pacific.

How far inland, away from the sea, could condors travel? There are reports from 1818 of what are likely condors living in Hells Canyon, far away from the coast. Condors were also glimpsed above the Snake River Plain near present-day Boise. Into the 1890s, condors were (possibly/probably?) observed over the Rocky Mountain Front in present-day Alberta, where the prairies of the edge of the Great Plains meet the steep Rockies. (This is reported in a 1951 academic article, “Was the California condor known to the Blackfoot ...?”, which also describes a history of apparent condors feeding on bison carcasses.). In 1897, Fannin (who Sharp describes as “perhaps the most highly respected ornithologist in British Columbia”) caused debate when he reported a sighting of condors near Calgary; that same year, a condor was reportedly observed on the Blackfoot reservation in Montana along the Rocky Mountain Front (just south of the Alberta border).

-------

Some remain very skeptical of the existence of a few condors in the Northern Rockies, so far inland. What is more generally accepted, though, is that condors were residents in the coastal Pacific Northwest and what is now called “eastern Washington.” However, some settler-colonial scholars continued to doubt the possibility that condors were regular, year-round, permanent residents. Evidence for this permanent residency (as opposed to mere seasonal migration from California) includes Native oral histories from multiple tribes and in multiple languages; great numbers of condors historically seen along the lower Columbia and in Willamette Valley; condor bones from the Salish Sea region; the 20th-century reports of condor roosts from Washington State and the Mt. Hood area; and the Columbia River Gorge would’ve apparently provided ample nesting habitat.

In 1817, a condor was apparently shot by a settler in interior British Columbia, far from the coast. Between 1805 and 1825, Euro-American surveyors harvested condors which lived between the Columbia River Gorge and the mouth of the Columbia near present-day Portland and Astoria, where the L*wis and Cl*rk expedition "collected” at least four or five condors. Into the 1830s, settler surveyors Douglas and Townsend both reported condors “in abundance” along the lower Columbia and in western “Oregon.” Condors were still regularly seen in Willamette Valley until the 1850s.

-------

In the “official” narrative of Euro-American institutions, the last certain observation of a condor within the borders of “Oregon” was famously seen in 1904, a bit south of the Siuslaw River in the passage between Willamette Valley and the Umpqua River corridor. But there are other observations of the condor in the Pacific Northwest in recent decades, observations which don’t get a lot of publicity. But, as Sharp reports: “The paleontological record is proof of condors’ long-term presence in the region, [and] cultural connections between the condor and northwestern Native American tribes were [and are] rich and diverse [...].”

Co-author of Birds of Oregon, David Marshall, has asked: “How could such a huge, charismatic species have been missed in the 20th century?” To which Sharp responds:

The explanation is [...] simple: Euro-Americans did not explore parts of the Cascade Mountains until the mid-1900s. [...] The eastern slope of Mt. Jefferson is within the Warm Springs Indian Reservation [...]. The upper Clackamas drainage was rarely visited by [non-Indigenous people] before roads penetrated the Cascades in the 1950s [...] and before logging in national forests increased from the 1960s [...]. That federal and state wildlife biologists “missed” condors in roadless wilderness until the mid-1900s is not surprising. The condors were not really “missed” but were known to Native Americans and early [settler-colonial] forest workers [...].

Condors were still observed near Mount St. Helens in the 1930s. Many of these more recent observations were also reported by Brian Sharp. Multiple times, between the 1920s and 1940s, Yakama communities reported condors near Mount Adams in the Cascades of Washington State. In the 1950s, land management agency fire lookout staff observed several condors near Myrtle Creek in the Cascades of Oregon. In the 1960s, Forest Survey road-survey crews reported encountering condors multiple times at the Collawash and Clackamas rivers near Mt. Hood, east of the Cascades crest. And the communities of Warm Springs also regularly reported the birds near Mt. Hood well into the 20th century.

These observations don’t really get mentioned by settler-colonial land management agencies.

But, if you trust Native communities to know the difference between a turkey vulture and a condor, then there were great birds with a 10-foot wingspan flying over the Salish Sea, the sagebrush steppe and oak savanna of the Columbia River, and these rainforest-shrouded volcanoes in the recent past.

181 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sage advice: An illustrated guide to smudging herbs

by Michelle Gruben

Once upon a time, there were only three kinds of smudge sticks in most witchy shops: Small, medium, and large. These days, you can choose from a vast array of smudging herbs, each with a different energy, aroma, and cultural history.

In this article, I’ll walk you through the plants that are most commonly used for smudging. (We’ll limit it to smudges that are derived from woods and leaves. Resin incenses are divine—but that’s a topic for another article.)

The variety of smudging herbs is incredible. But you’ll also notice some similarities. First, most of them come from the leaf and stem parts of bushes and small trees. (Fruits and flowers make wonderful sachets, baths, and teas, but lose all their charm when burned.) Second, most smudging plants grow in desert and mountain regions, where the soil is poor. Plants in these climates tend to be short and shrubby, and they rely on fragrant oils as a way to keep insects and other animals from munching on them to get to their water and nutrients.

You’ll also notice that many excellent smudging plants come from the genus Salvia (true sages). There are several hundred distinct species of Salvia, but only the most aromatic varieties are used for smudging. Many other varieties grow wild, or are cultivated as hardy ornamentals. Sage’s reputation as a beneficial plant is ancient and well-deserved. The Romans named the plant Salvia after the Latin verb meaning to save, redeem, or heal.

So where can you find these delicious-smelling plants? Well, just about any New Age store will have smudges for sale. (White Sage, at least—you may have to search online for some of the more exotic varieties.) Also try health food grocers, yoga studios, artisan and farmer’s markets. You may even want to consider growing smudging plants in your garden, or gathering them in the wild.

A quick warning: The plants listed below are not harmful or dangerous under normal circumstances. Still, they can cause irritation and allergic reactions in some people. If you have asthma or respiratory problems, burning anything may not be great for your health. (Consult a doctor or herbalist if you have concerns.) Burn smudges in a well-ventilated area—coughing and choking on the smoke will not enhance their effects! Always be mindful of fire safety, especially indoors and in dry climates.

Finally, please don’t rely on herbal remedies as a substitute for medical treatment. When I describe an herb as healing, I mean only that it will contribute to your general well-being—not that it will cure cancer, toenail fungus, or anything in between. I always recommend that you store herbs in labeled packages, out of the reach of children and pets.

White Sage (Salvia apiana—also known as Bee Sage, California Sage, Sacred Sage)

For many people, “smudging” means one thing only—White Sage. (Its Latin name refers to its main pollinator, the honeybee.) White Sage is the bread and butter of any smudging kit. Versatile and effective, it’s suitable for most any smudging ritual—cleansing, healing, protection, meditation, and so on. When mixed with other herbs, it makes a wonderful base for a custom smudging blend.

White Sage grows wild across the American Southwest in bushy clumps. (The strongest-smelling product comes from the western fringes of the Mojave and Sonoran deserts.) The plant has been gathered for thousands of years by Native Americans, particularly the Chumash. It is regarded as a sacred plant—an important source of food, medicine, and benevolent Spirit.

White Sage is herbaceous, sweet, and slightly astringent. It's rather similar to Eucalyptus, but more complex. Some people say it smells like Marijuana when burned. (To me, burning White Sage just smells like burning White Sage—but the similarity is something to keep in mind if you’re going to use it in public.) The smell of White Sage is so strong that just rubbing its fuzzy leaves between your fingers is enough to release the scent.

Almost all of the White Sage on the market comes from California. Most of it is wild-gathered and hand-tied by producers large and small. There really isn’t much difference in quality between brands. However, if it matters to you, you may want to seek out a producer who gathers Sage with the proper prayers and observances. It’s even possible to buy White Sage that is harvested by American Indians according to traditional practices, just as they have done for centuries.

Because it is the most widely available smudge, you can buy White Sage in many sizes and formats. Small Sage wands (3-4 inches) are ideal for small spaces, solitary practice, or to keep handy in a ritual kit. The big boys (8 inches and up) are best reserved for outdoor use and large group rituals—unless a wailing smoke detector is part of your space-clearing strategy! You can also buy the loose leaves and stems by the ounce or pound. This lets you control the amount you use, and allows for blending with other herbs.

White Sage is affected by periodic droughts, meaning it has years in which the harvest is smaller. The price and quality fluctuate accordingly. Still, there’s no need to pester your local New Age emporium about the vintage year of their stock. Freshness isn’t a huge consideration, either. The volatile oils in dried Sage will dissipate somewhat over time—but I’ve used Sage sticks that were hiding in my altar cupboard for years and no one was the wiser. Buy it, it’ll burn just fine.

Common Sage (Salvia officianalis—also known as Garden Sage, Common Sage, Green Sage, or Kitchen Sage)

Many a hard-up Witch has wondered if it’s okay to use culinary Sage—the kind that goes in turkey stuffing and breakfast sausage—for smudging. The answer is yes! Common Sage is a close relative of White Sage, and has many of the same beneficial properties as its superstar cousin, White Sage. Common Sage originates in Europe, and its medicinal and folkloric uses date back to the Middle Ages. For those involved in the European traditions of Witchcraft, it may make more sense to smudge with Common Sage than one of the North American varieties.

Besides, not everybody has a metaphysical store that they can rush to for supplies, and a good Witch knows how to improvise. The main advantage of Common Sage is that it grows in many climates, and is readily available in fresh and dried form at most supermarkets. Will Sage ward off bad vibes when used in food? I don’t know, but I’ll take another slice of Sage Derby while I mull it over.

Not everyone agrees that the smell of burning Common Sage is pleasant. A little goes a long way. Also, the herb must be quite dry to smolder effectively. If burning Sage doesn't work for you, remember that you can still use the plant to cleanse and bless your space. Add the essential oil to sprays and washes, or put the leaves in sachets, witch bottles, or mojo bags.

Blue Sage (Salvia clevelandii or Artemisia tridentata—also known as New Mexico Sage, Desert Sage, Grandmother Sage)

Blue Sage is a hardy bush found in the deserts of the Southwest. It’s named for its abundant blue flowers, but the leaves also have a blue-ish cast. It has thin leaves and a fragrance that is both herbaceous and floral, similar to Lavender.

A close relative of White Sage, Blue Sage is also good for healing and cleansing rituals. Its soothing, relaxing smell can be used to aid meditation, or burned simply for enjoyment. It’s not as pungent as White Sage, and is more agreeable to some folks who find the strong, bracing scent of White Sage overpowering. You can find Blue Sage in smudge sticks and in loose-leaf form.

Another pale sagebrush, Artemisia tridentata, is pictured above. It goes by the trade name "Blue Sage," but is not a member of the Salvia clan.

Lavender Sage (Salvia leucophylla or Salvia mellifera)—also know as Gray Sage, Purple Sage, Wild Lavender)

Yet another far-flung member of the Salvia family, Lavender Sage is a sun-loving plant that grows in southern coastal California. It’s named for its clusters of purple flowers—the leaves are rounded, green, and fuzzy like Common Sage. (They darken to gray when dried.) Lavender Sage is unrelated to the flower Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia). However, it physically resembles Lavender (especially when in bloom) and has a similar clean, flowery fragrance. As if that wasn’t screwy enough, some artisan producers do use true Lavender as an ingredient in smudges, and they don’t always make it clear which plant is meant. Lavender Sage is known for its calming, peaceful, and sedating effects. It inspires love and relieves anxiety. Because of its irresistible scent and natural beauty, a Lavender Sage smudge is a great choice for your spells of attraction. Lavender Sage is often combined with White Sage for a killer duo. Like a 2-in-1 shampoo, this pair will cleanse and condition in a single step! Black Sage (Salvia mellifera, Artemisia nova, Artemisia douglasiana and others—also known as Mugwort, Magical Sage, Black Sagebrush, Dream Weed)

Used to encourage dreams and visions, Black Sage is an herb of introspection and inner healing. When burned before bedtime, it aids in restful sleep and pleasant dreams. Black Sage is used for astral travel, shamanic journeying, and for protection during such excursions. One Pagan priest I know begins group trance workings by smudging the participants with Black Sage. Black Sage is like the mystical, shifty-acting cousin of the Sage clan—so shifty, in fact, that people can’t even agree on what plant it is! There are a few different products sold under the name “Black Sage.” I found this out when I noticed that the Black Sage I ordered for the store looked different from month to month. I called my supplier, and he confessed that the exact composition of the smudge changes based on availability. A true Sage, Salvia mellifera has long leaves that are dark green on top and silver underneath. It is found in the mountains of the West Coast from California north through British Columbia. The plant can be difficult to identify because it resembles other species. The leaves only darken dramatically in times of drought. To add to the confusion, there are several cultivars, and Black Sage readily hybridizes with Purple Sage and Blue Sage plants. Other Black Sage products come from shrubs in the genus Artemisia. They are commonly called sagebrushes, but these dark-green plants are more closely related to the Daisy than to true Sage. When dried, Artemisia tridentata has a lighter, straw-brown color, and may also have small crowded blossoms on its stalks. But Artemisia douglasiana (shown in the photo above) is leafier and easy to mistake for dark Sage such as Salvia mellifera. Why does it matter? The metaphysical properties of both plants are similar, but Artemisia-based smudges may also contain small amounts of thujone. This mildly trance-inducing compound is best-known as the active ingredient in traditional absinthe liqueur. Black Sage contains less thujone than the common herbs Mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris) and Wormwood (Artemisia absinthium). Black Sage won’t cause you to “trip” or wildly hallucinate. At most, it may intensify your efforts at visualization and vivify your dreams. Even so, some people (like pregnant women and straight-edgers) should avoid using Black Sage. Desert Sage (Artemisia tridentata or Artemisia californica [pictured]—Desert Magic, Mountain Sage, Grey Sage, New Mexico Sage, Sagebrush Smudge)

This aromatic shrub thrives in the windswept deserts of the Santa Fe/Taos area. It has skinny, branched leaves and a light brown color. Desert Sage shares some common nicknames with Blue Sage, and the two plants are sometimes sold interchangeably. (Are you noticing a pattern here?) Desert Sage has a warm herbaceous aroma that is a bit peppery (think Bay leaves or Mint tea). It is used for cleansing and purifying, protection, and inner strength. It is said to bring pleasant thoughts and relieve headaches and anxiety. Desert Sage is available both loose and in smudge sticks. It blends well with most other smudging herbs. Desert Sage produces a dense, straw-like bundle that is sometimes sprinkled with resin incenses for an especially rich combination. Desert Sage laced with Dragon’s Blood or Copal is just delicious! Dakota Sage (Artemisia ludoviciana—Badlands Sage, Silver Wormwood, Old Man Sage, Silver King, Western Mugwort, Dakota White Sage)

Another Artemisia smudge, this one grows all over the badlands of South Dakota stretching all the way south to Louisiana. Dakota Sage is rarely found in commercial Sage products, but I’ve included it because it’s easily gathered in many places across the United States. The aroma and appearance of Dakota Sage is very similar to that of Desert Sage. However, the fragrance is usually less intense. Piñon Pine (Pinus edulis and others—also known as Pinyon Pine)

The Piñon Pine is a generous evergreen tree from the foothills of the American Southwest. The nuts were an important food source for early Americans--these days, the tree is best known for stocking chimineas (Southwestern patio stoves). Piñon has a smooth, woodsy scent that's especially powerful, thanks to its high concentration of pine resin. Piñon is an excellent all-purpose smudge, and a capable stand-in for White Sage, if you prefer to avoid the latter. Its energy is cleansing, healing, and strengthening. Oh, and it repels insects, too. Cedar (Calocedrus decurrens [California Incense Cedar], and many other species)

Cedar is an ancient tree, one of the oldest beings still thriving on the Earth. Cedar trees look much the same as they did when dinosaurs roamed the land. Back when other trees were trying out those newfangled “leaves,” Cedar said “I’m good” and stayed with the tried and true. The smell of Cedar is woodsy and fresh. It recalls ancient forests, and invokes their protection and wisdom. Both the wood (in the form of chips or shavings) and the foliage make effective smudges.

Cedar smudges carry a medicine of protection. Cedar is often used to cleanse a home or apartment when first moving in, inviting unwanted spirits to leave and protecting a person, place or object from unwanted influences. Along with Rosemary and White Sage, Cedar is one of the most aggressively cleansing smudges you can choose. Juniper (Juniperus communis)

Juniper has a sweet and spicy "Christmas tree" fragrance and abundant blue berries. Like Cedar, Juniper is probably one of the most ancient plants. Juniper is said to have a masculine, protective energy, and is used in spells of cleansing and prosperity. Juniper berries are popular in good luck charms, while the leaves are often used for smudging. Juniper is best used for blessing a new venture or dwelling, and inviting in abundance. Bearberry (Uva ursi)

Bearberry is a low-growing North American shrub in the Heather family. As its name suggests, it is a favorite of foraging bears. It is used for smudging, animal magic, shape-shifting, and other shamanic work. Native Americans traditionally mix it with Tobacco leaf to create a ritual smoke blend (called kinnikinnick), said to carry prayers and bring visions. Sometimes the leaves come mixed with peppercorn-sized berries. Don't throw these out—the Bear spirit is said to appreciate the offering. Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalus)

A culinary herb with an assertive fragrance, this woody perennial may also be used for smudging. It clears negativity, inspires confidence, and invigorates the mind and body.

Some people prefer to avoid herbs associated with Native American cultures out of concerns about cultural appropriation. Rosemary is an Old World herb with a long history of use in incenses, and so makes a guilt-free alternative for Western practitioners. Sweetgrass (Hierochloe odorata or Anthoxanthum nitens—also known as Seneca Grass, Holy Grass, Vanilla Grass, Mary’s Grass, Bison Grass)

Sweetgrass is a long, fragrant grass that grows wild across portions of the American Great Plains. It's frequently braided or tied in bundles, then dried.

Sweetgrass is sacred to several Plains tribes. They have traditionally burned it to drive out evil and harm, and allow benevolent spirits to approach. Ancient lore states that Sweetgrass is the hair of the Earth Mother, and invokes love, kindness, and honesty.

A relative of American Sweetgrass was known in medieval Europe. Sheaves of the sweet-smelling grass were strewn across thresholds, especially of churches, where it would release a gentle aroma when trod upon.

Sweetgrass smells of fresh hay with hints of warm vanilla. It induces a mellow, almost soporific state when burned. (It contains coumarin, which is thought to be mildly psychoactive.) Some say the proper way to burn Sweetgrass braids is to shave small portions off with a knife, allowing them to fall on hot coals. Yerba Santa (Eriodictyon glutinosum and Eriodictyon californicum—also known as Holy Herb, Mountain Balm, Consumptive’s Weed, Bear Weed)

Yerba Santa ("holy herb") is a sweet-smelling plant that grows in the arid hills of the Southwest. It got its common name from Spanish monks who were impressed with its healing properties. Yerba Santa is burned to honor ancestors, increase psychic powers, and bring healing and protection. It is also a traditional remedy against coughing and many other ailments. Yerba Santa grows wild only in certain areas of California and Northern Mexico—a true regional treasure. Tobacco (Genus Nicotiana)

The health hazards of Tobacco are well-known, so much that its sacred uses have fallen by the wayside. Wild-growing and cultivated Tobacco had a place in the rituals of many Native American tribes. Aleister Crowley considered Tobacco a consummate herb of Mars. And it is said that Faeries particularly enjoy offerings of the stuff. (Along with other human vices, like whiskey and sweets!) Commercially packaged cigarettes are full of reconstituted crud, chemicals and additives that make them unsuitable for magickal use. If you’re going to burn tobacco ritually, the best option is loose tobacco leaves, but they aren’t easy to find. The next best thing might be a shredded pipe tobacco that is additive-free. Palo Santo (Bursera graveolens—also known as Holy Wood)

Palo Santo (or “Holy Wood”) is a sweet-smelling tropical wood that is a natural incense. Palo Santo is said to clear out negative spirits and energies, increase relaxation, and bring joy and harmony to the home. It is in the family of trees that produces Frankincense and Myrrh, but is native only to Ecuador, Peru, and the Galapagos Islands. Its aroma is smooth, aromatic and spicy. (I think it smells a bit like gingerbread!) The holy reputation of Palo Santo dates back to the time of the Incas, who used it in their ceremonies of healing and cleansing. When the Spaniards arrived in South America, they couldn’t easily obtain their preferred church incenses, so they substituted the local equivalent. To this day, Palo Santo is used there for Catholic holy days and processions. Palo Santo comes from a slow-growing tree that is in danger of over-harvesting. Both Ecuador and Peru have laws on the books designed to protect this rare species. Reputable importers use only fallen limbs and strive to minimize waste. Sticks, chips and even sawdust are sold by the ounce, with the scraps being compressed into incense cones or distilled for their essential oil. Sticks of Palo Santo can be lit on one end and burned just like any other smudge stick, but in humid conditions charcoal may be required. The chips and powder are best burned over charcoal.

Mixed smudges

Sometimes you may want to use a smudge with multiple ingredients, combining the aromas and properties of two or more plants. Mixed smudges come in a huge array of combinations, some laced with resins or flowers—far too many to list. A Black and White Sage smudge (pictured) combines the psychic openness granted by Black Sage with the protective qualities of White Sage. However, it's worth noting that in some Native American traditions, the Four Sacred Medicines (White Sage, Cedar, Tobacco, and Sweetgrass) are never mixed.

Hope you've found this tour of smudging herbs useful and enlightening. Happy smudging—and for godsakes, open a window!

https://www.groveandgrotto.com/blogs/articles/100896071-sage-advice-an-illustrated-guide-to-smudging-herbs

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

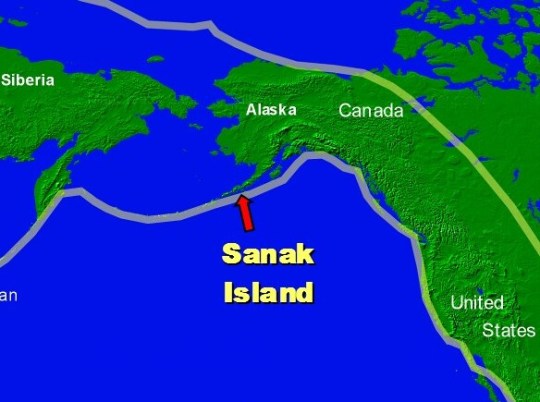

Cap 168 : Paleoindios en Islas del Pacífico de Canadá y Estados Unidos.

.

Para la Teoría de la Llegada Costera de los Paleoindios desde Beringia hasta Norte América es vital estudiar los Yacimientos Arqueológicos en Islas del Océano Pacífico de Canadá y Estados Unidos.

.

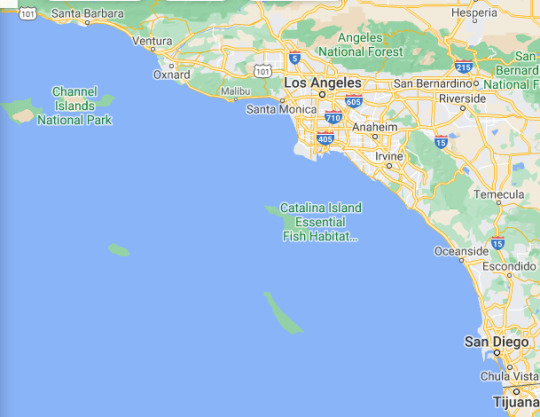

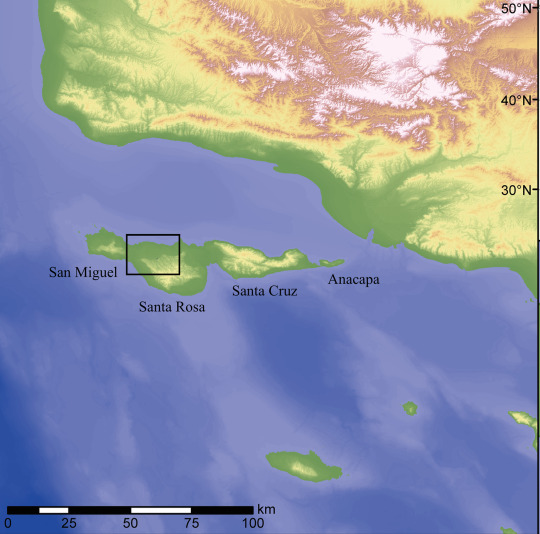

Siguiente Mapa : Ves las Ciudadades de Los Angeles y San Diego en California y las Islas del Canal a la Izquierda arriba = Santa Rosa a la izquierda y Santa Cruz a la derecha.

.

. En el siguiente Mapa ves a toda California, Tijuana queda en México. Las Islas del Canal son las muy cercanas a la Ciudad de Los Angeles. .

Aunque no es la Prueba Reina, ni es la Seguridad definitiva y total, si es cierto que se acumulan Evidencias en las Islas del Pacífico Norte, frente a Canada y Estados Unidos de que los Paleoindios eran fuertes inteligentes navegantes en Botes y que estaban acostumbrados a comer productos Marinos como Peces, Moluscos, Mamíferos Marinos, etc ..

.

Las Islas del Canal se pueden divisar desde las Montañas de Santa Bárbara, California. Los Paleoindios tenían que ser buenos Navegantes en Botes para recorrer los 10 Kilómetros de Mar que separaban al Continente de las Islas en ese Tiempo de 12,000 Años antes del Presente.

.

*******************************

.

Abstract

Three archaeological sites on California’s Channel Islands show that Paleoindians relied heavily on marine resources. The Paleocoastal sites, dated between ~12,200 and 11,200 years ago, contain numerous stemmed projectile points and crescents associated with a variety of marine and aquatic faunal remains.

At site CA-SRI-512 on Santa Rosa Island, Paleocoastal peoples used such tools to capture geese, cormorants, and other birds, along with marine mammals and finfish. At Cardwell Bluffs on San Miguel Island, Paleocoastal peoples collected local chert cobbles, worked them into bifaces and projectile points, and discarded thousands of marine shells.

With bifacial technologies similar to those seen in Western Pluvial Lakes Tradition assemblages of western North America, the sites provide evidence for seafaring and island colonization by Paleoindians with a diversified maritime economy.

.

Fuente : Revisa Science

Paleoindian Seafaring, Maritime Technologies, and Coastal Foraging on California’s Channel Islands

.

https://science.sciencemag.org/content/331/6021/1181

.

*******************************

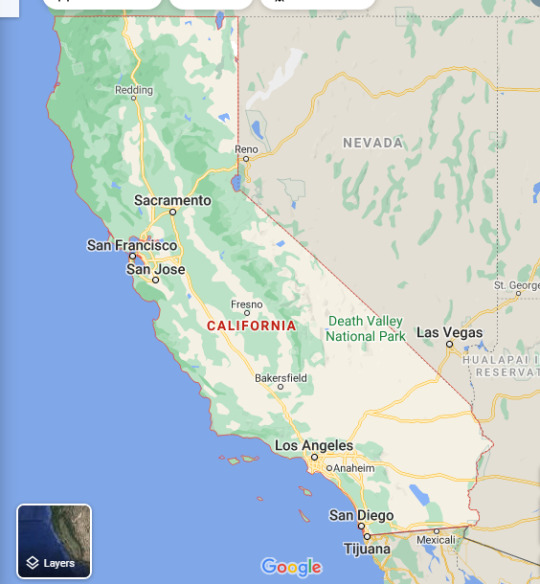

-

El Corredor del Río MacKenzie entre las Capas de Hielo Laurentida y Cordillerana pudo demorarse mucho en ser abierto y transitable. Y es posible que los Paleoindios ya estuvieran en Estados Undios por Vía Marítima, es decir navegando en Botes.

.

.

Fuente : Is the Ice-Free Corridor an Early Pathway into Americas? - By K. Kris Hirst

Updated July, 2019

https://www.thoughtco.com/ice-free-corridor-clovis-pathway-171386

.

*******************************

.

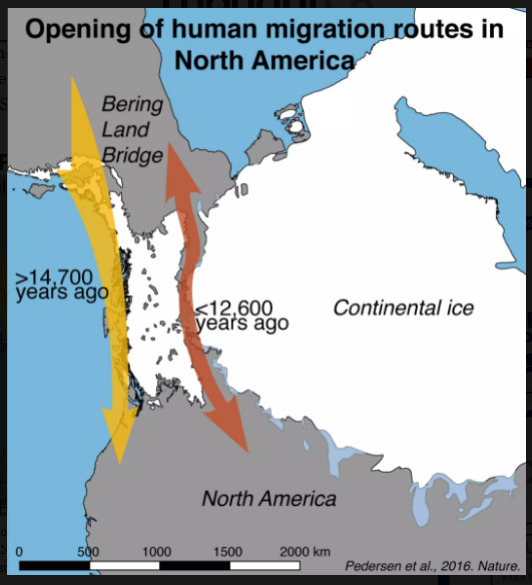

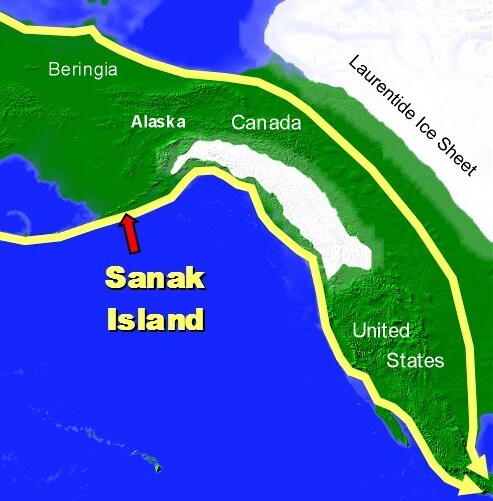

Sedimentos extraídos con Taladro como un Tubo de la Isla Sanak en Archipiélago de las Aleutas de Alaska muestran que había un Corredor Marino libre para los Paleoindios. El Siguiente Mapa muestra donde queda la Isla Sanak en la Geografía de Hoy, las Investigaciones dan prueba de no estar cubierta de Hielos antes de que se abriera el Corredor terrestre entre las Capas de Hielo Laurentida y Cordillerana. Y de que pudiera haber dado Alimentos para la Vida Humana.

.

.

Siguiente Mapa : Como era la Isla Sanak integrada al Continente Beringia. Cuando se abrió el Corredor ( Corridor ), Pasadizo o Brecha ya habían llegado los Paleoindios a British Columbia y a Estados Unidos. Los Científicos dudan que el Corredor proporcionara Alimentos a Animales y Hombres en sus Primeros Cientos de Años libre de Hielo.

.

.

Sanak Island lies around the midpoint of the Aleutian Archipelago extending off Alaska. It is 15 miles long by 6 miles wide and is capped by a single volcano called Sanak Peak. The Aleutians would have been the highest point on the Beringian landmass. The analysis of pollen from sagebrush, heather, willow and grasses, as well as radiocarbon-dated deep water sediments, from the bottom of 3 lakes on Sanak indicate that the island and its now-submerged coastal plains (and therefore the northern part of the Pacific coastal route) were free of ice by around 17,000 years ago.

Th Island is capped by a single volcano called Sanak Peak. The Aleutians would have been the highest point on the Beringian landmass.

.

New evidence suggests sea-faring Paleo-Indians were colonising America 2,000 years before Ice Free Corridor opened --- by Lee Rimmer

.

https://www.abroadintheyard.com/evidence-suggests-seafaring-paleoindians-colonising-americas-before-ice-free-corridor-opened/

.

*******************************

.

Fuente : Revista Nature, ver link abajo

Humanos habitando las Islas del Canal de California hace 13,000 Años y cambiando la Fauna.

.

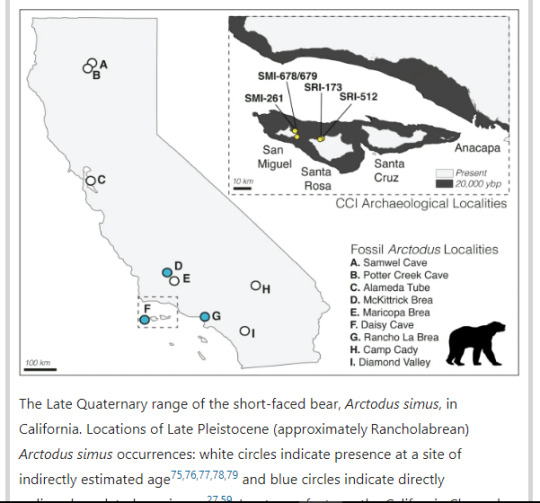

California’s Channel Islands (CCI) are an ideal system to refine our diagnostic toolkit due to the well-studied geologic and human histories and communities of iconic endemic fauna. The CCI consist of eight islands that are currently located approximately 20–100 km from the California coastline.

The size of the islands and their distance to the mainland has shifted with past glacial-interglacial cycles, but they were never connected by a land or ice bridge during the Quaternary .

The CCI are split into two north–south island groupings with distinct geologic histories: the northern islands (Santa Rosa, San Miguel, Santa Cruz, Anacapa) were joined as a single superisland, Santarosae, as recently as 10,000 years ago, whereas the southern islands have always been more isolated.

.

.

Humans colonized Santarosae ~ 13,000 years ago, although there are hints of a possible earlier human presence. The island’s more than 700 archaeological sites document substantial anthropogenic influences on the ecology of the islands from the Late Pleistocene to the present, including the introduction of taxa previously considered to be native endemic lineages. Daisy Cave (CA-SMI-261), a well-studied and finely stratified archaeological and paleontological site on San Miguel Island, has yielded a diverse assemblage of faunal remains that provide critical insights about the relationships between Indigenous peoples and the endemic fauna of the CCI.

.

Biogeographic problem-solving reveals the Late Pleistocene translocation of a short-faced bear to the California Channel Islands.

.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-71572-z

.

*******************************

.

The three island camps, which are between about 11,000 and 12,000 years old, show that some early Americans were well adapted to coastal living.

........

Because the Channel Islands would have lain some 10 kilometres off the California coast at the time, the hunters must have reached them by boat, Rick says. Once they found the islands, which are visible from present-day Santa Barbara, the mariners would have found ample food and few predators. "They would have found an amazing suite of resources — massive amounts of seabirds, seals and sea lions" not found on the mainland, he says. "In my view it would have seemed like a paradise."

The archaeologists surmise that the people who lived at the Channel Island sites were adept at making a living from the sea, and were not from the interior of North America. The tools found on the Channel Islands are a better match to tools attributed to the Western Pluvial Lakes Tradition in the Pacific Northwest than to the inland Clovis culture, which, also, had disappeared by around 12,000 years ago. "What it tells us is that these weren't people who came from the continental interior and stumbled onto the coast," says Rick.

........................

Ted Goebel, an archaeologist at Texas A&M University in College Station, says the stemmed stone points found on the Channel Islands resemble those found in Kamchatka, Russia, dating from 1,000 years earlier,

March 2011 Seafront property attracts ancient Californians Ewen Callaway Nature (2011)

.

https://www.nature.com/articles/news.2011.135

.

.

*******************************

.

Hay varios Yacimientos Arqueológicos en las Islas del Norte del Canal de California, muy cercanas a la Ciudad de Los Angeles. Estos se detallan en el Link al Art��culo mas abajo.

Aquí están sus Nombres en este Mapa. Estas Islas estaban Unidas hace 14,000 Años y a esa gran Isla se le llama Santarosae, para distinguirla de la Santa Rosa actual.

Algunos hallazgos dan Cronologías de 13,500 Años antes del Presente, y varios intermedios hasta 11,000 AP.

Estos Yacimientos demuestran que los Paleoindios dominaban la Navegación en Botes, la Subsistencia de Animales Marinos como Peces, Moluscos y Mamíferos Marinos, también capturaban Aves Marinas y sus Huevos. Y se demuestra que perfectamente se podían desplazar por la Costa hasta llegar al antiquísimo Yacimiento Paleoindio de Monte Verde en Chile. El que destruyó la Hipótesis del “Clovis Primero” por su brutal Antiguedad.

Como estas Islas de California prometen tanto, entonces los Científicos están empezando a hacer Arqueología submarina con Vehículos no tripulados a Profundidad y con muchos Instrumentos, tratando de no arriesgar Humanos en una Labor muy pesada, demorada y ardua para hallar yacimientos sumergidos bajo mas de 100 mts que subió el Nivel del Mar desde hace 14,000 Años hasta el Presente.

Los mejores Hallazgos están por hacerse a mas de 100 mts de Profundidad pues ahí deber estar los Asentamientos Pesqueros Paleoindios. .

.

.

Site setting, stratigraphy, and dating

Today the NCI—consisting of Anacapa, Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa, and San Miguel islands—are located between 20 and 44 km from the adjacent mainland coast (Fig 1). Near the end of the Last Glacial Maximum (ca 20,000 cal BP), however, the islands were united into a single ~125 km long island known as Santarosae [12], the eastern end of which was as little as 6–8 km from the mainland.

The latest reconstructions of Santarosae’s paleogeography suggest that rising post-glacial sea level reduced the landmass by as much as 70–75 percent, causing the NCI to separate between about 11,000 and 9,000 years ago. Then and now, the NCI had a relatively impoverished terrestrial fauna, a fairly diverse and productive flora, and a wealth of edible marine resources, from seaweeds to marine mammals, shellfish, fish, and seabirds.

.

Maritime Paleoindian technology, subsistence, and ecology at an ~11,700 year old Paleocoastal site on California’s Northern Channel Islands, USA

.

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0238866

.

*******************************

.

.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

This isn’t a very dramatic story, but it’s one of the few paranormal experiences I’ve had. My friends and I used to go on night drives to the local beach and just hang out watching the waves until like 1 am. After one of these sessions, we started driving back home. This highway is 2 lanes, and it goes through miles of unlit coastal sagebrush. We’re all laughing, having a good time talking, and then we see a figure walking around the side of the road. As the front of him is illuminated, my stomach gets a sickening feeling. Then I realize that this person has no face - just pale flat skin. We pass the person quickly and everyone in the car is silent. Then my now husband says in a shaky voice, “hey, did anybody see a face on that guy?” All of us saw that he was faceless. I’ve never seen anything similar there since then, and we all still wonder what it could’ve been.

Are you FUCKING kidding me? Beings with no faces are said to be demons.

15 notes

·

View notes