#coastal invertebrates

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Slip on the Common Slipper Limpet

The common slipper limpet, also known as the boat shell or the fornicating slipper snail (Crepidula fornicata) is a species of sea snail native to the North American coast of the Atlantic Ocean. In addition, it has been introduced to the eastern coasts of Europe and parts of the Pacific Northwest and Japan. They can reside in a variety of habitats including bays, estuaries, island shores, and rocky intertidal zones; their maximum depth tolerance is 70m (229 ft).

Fornicating slipper snails are noted for their unique mating methods. Adults typically live stacked on top of each other, with up to 12 to 14 individuals in a group. The largest, and oldest adults are at the bottom of the stack, while the younger, smaller adults are at the top. C. fornicata is a sequential hermaphrodite; new adults are all male, and will change into females as they get older or if they become the oldest in a stack of all males.

Breeding can occur between Februrary and October, although the peak season is in May or June. Unlike other marine mollusks, which are broadcast spawners, the common slipper limpet utilizes internal fertilization. The male closest to the female at the bottom extends his penis under her shell and fertilize up to 11000 eggs. These eggs hatch after about 3-4 weeks, and the planktonic larvae are released into the water. These larvae take 4-5 weeks to develop into juveniles, at which point they settle either on bare rock or on top of an established limpet chain. If it settles in isolation, the young adult immediately changes into a female; if it settles on a chain, it remains a male. Adults can live on these chains for up to 6 years.

Adult boat shells are rather small, ranging in length from 20–50 mm (0.7-1.9 in). The shell is distinctly arched, with a flat underside that gives it a slipper-like appearance. The shell can be white, pink, or yellow with red or brown streaks; older adults are often covered in algal growth.

Conservation status: The common slipper limpet has not been evaluated by the IUCN. Although they are commonly harvested for food, populations are considered stable. Outside its native range, this species is considered invasive and harmful to other limpet snails.

If you like what I do, consider buying me a ko-fi!

Photos

Dr Keith Hiscock

Sytske Dijksen

#common slipper limpet#Littorinimorpha#Calyptraeidae#slipper snails#limpets#gastropods#mollusks#invertebrates#marine fauna#marine invertebrates#intertidal fauna#intertidal invertebrates#coasts#coastal invertebrates#atlantic ocean#queer animals#queer fauna#nature is queer

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

🎨 InsertAnInvert 2024

Coastal week 3: Intertidal

carpet sea star (meridiastra calcor)

#art#digital art#invertebrate#invertebrates#halftone#screentone#illustration#nature#animals#InsertAnInvert#InsertAnInvert2024#blue#cyan#noAI#sea#ocean#ocean creatures#sea creatures#animal art#Old Art#sea star#carpet sea star#coastal#intertidal

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

#i wish i was a banana slug#🩻#banana slug#woods#forest#muir woods#fern#san francisco#california#wilderness#redwoods#sequoia trees#green#plants#plantblr#coastal redwood#trees#woodland#trails#hiking#hiking trail#nature hikes#nature#naturecore#creepy forest#norcal#bugs#creatures#gastropods#invertebrates

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Autumn Millifae

This shiny arthropod is a deft swimmer; it is quite a treat to see one swirling and twirling down a creek during the waning sunlight of autumn.

#environ: coastal#environ: water#colour: brown#invertebrate#millipede#aesthetic: fae#aesthetic: autumn

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Xerces Blue (Glaucopsyche xerces) has been extinct since the 1940s; they used to live in the coastal meadows and sand dunes around San Francisco, before urban expansion and loss of habitat caused their decline. They are the namesake of the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation.

924 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ok, another Mexidracon thread because I find this critter just fascinating. In our latest stream I tried to illustrate my point further by showing the proposed sediment probing behavior I assume for this animal.

I did the image on the left on stream but I wasn't that happy with the background so i did the second version above. Again, I don't think these arms were made for fishing, it's arms don't appear flexible or powerful enough to grab or spear fish.

It's relatively short legs also might hint at an overall slower locomotion style, like wading through shallow water, something that would have been abundant in its coastal/deltic environment...

Something that I also let influence this reconstruction is a certain specimen of Ornithomimus which shows traces of feathers on the forearm but NOT of the metacarpals. This might mean that the primaries were just smaller but for the purpose of this reconstruction I went with naked hands... (artwork by Julius Csotonyi)

In this last quick doodle I wanted to show the way I imagine these guys going after invertebrates. This of course assumes many things. Like, that the interpretation of the original authors of this fossil is correct; that the rest of the animal was rather "normal" for an ornithomimosaur or that these limbs had a practical use at all. Another thing that is of course possible is that these arms actually were display structures, very colorful, maybe fully feathered. But I personally prefer the sediment probing idea for now and would avoid yet another display function case.

I hope we find some more specimens in the near future and I would love to see some more takes on this animal. It's been a while since I thought about a new dinosaur this much.

#paleoart#sciart#paleostream#palaeoblr#cretaceous#dinosaur#ornithomimosaur#mexidracon#theropod#mexico

829 notes

·

View notes

Text

Round 3 - Reptilia - Charadriiformes

(Sources - 1, 2, 3, 4)

Our next order of birds are the diverse Charadriiformes, collectively called “shorebirds”. This large order contains the families Burhinidae (“stone-curlews” and “thick-knees”), Pluvianellidae (“Magellanic Plover”), Chionidae (“sheathbills”), Pluvianidae (“Egyptian Plover”), Charadriidae (“plovers”), Recurvirostridae (“stilts” and “avocets”), Ibidorhynchidae (“Ibisbill”), Haematopodidae (“oystercatchers”), Rostratulidae (“painted-snipes”), Jacanidae (“jacanas”), Pedionomidae (“Plains-wanderer”), Thinocoridae (“seedsnipes”), Scolopacidae (“sandpipers”, “snipes”, “curlew”, and kin), Turnicidae (“buttonquails”), Dromadidae (“Crab-plover”), Glareolidae (“coursers” and “pratincoles”), Laridae (“gulls”, “terns”, “skimmers”, and kin), Stercorariidae (“skuas”), and Alcidae (“auks”, “puffins”, “guillemots”, and kin).

Charadriiformes are small to medium-large birds that typically live near water, however, some live in the open sea, some live in dense forest, and some living in deserts. Most eat small animals ranging from invertebrates to fish to other birds. The order was formerly divided into three suborders based on behavior, the “waders”, the “gulls”, and the “auks”, but these three groups were paraphyletic. However, they represent a good summary of the main forms charadriiformes can take. The “waders” are generally long-legged, long-beaked birds which tend to feed by probing in the mud or picking items off the surface in both coastal and freshwater environments (however, terrestrial shorebirds like the Woodcock [Scolopax minor] and thick-knees [family Burhinidae] would also be considered “waders”). The “gulls” are generally larger species which catch fish from the sea, scavenge, or steal food from other animals. The “auks” are coastal species which nest on sea cliffs and dive underwater to catch fish, on flipper-like wings that can swim as well as fly. Now, it is generally understood that the auks are closer related to the gulls than any other family, and birds traditionally considered “waders” exist in all three suborders. Charadriiformes are one of the most, if not the most, widely dispersed bird orders, living on every continent and in almost every habitat.

Charadriiformes demonstrate a larger diversity of reproduction strategies than do most other bird orders (see propaganda below the cut for more). In most species, both parents take care of the young, but in some, the father is the main caretaker. Some breed and raise young in large colonies, while others nest alone.

Alongside the waterfowl, the Charadriiformes are the only other order of modern bird to have an established fossil record within the Late Cretaceous, living alongside the other dinosaurs. The modern groups of charadriiformes emerged around the Eocene-Oligocene boundary, roughly 35–30 million years ago.

Propaganda under the cut:

Many of the “stone-curlews” or “thick-knees” (family Burhinidae) are nocturnal, singing their eerie wailing songs at night. Suiting their nocturnal habits, they have very large, yellow eyes. They are effective hunters of insects, and some farmers will keep tamed thick-knees around their fields for pest control.

Like flamingos, the rare Magellanic Plover (Pluvianellus socialis) lives and breeds near saline lakes.

The unique Sheathbills (genus Chionis) are the only Antarctic birds without webbed feet.

Sheathbills and the Spur-winged Lapwing (Vanellus spinosus) have rudimentary spurs on their “wrists”, in place of wing claws, which they use for defense.

The “Trochilus” or “Trochilos”, sometimes called the “Crocodile Bird”, is a mythical bird first described by Herodotus (c. 440 BC), and later by Aristotle, Pliny, and Aelian, which was supposed to have been in a symbiotic relationship with the Nile Crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus), supposedly cleaning parasites and debris from the crocodile’s mouth and teeth. Various charadriiformes have been suggested as the inspiration for the Trochilus, including the Spur-winged Lapwing and Egyptian Plover (Pluvianus aegyptius). These birds are the most likely to feed around basking crocodiles, and tend to be tolerated by them, but this “tooth-cleaning” behavior has never been witnessed in the modern day. Nevertheless, the legend has become so prominent that these birds are sometimes still used as examples of symbiotic relationships!

The European Golden Plover (Pluvialis apricaria) spends its summers in Iceland, and in Icelandic folklore, the appearance of the first plover in the country means that spring has arrived. The Icelandic media always covers the first plover sighting.

The avocets (genus Recurvirostra) (image 2) are some of the only birds with upturned beaks. They use their strange beaks to feed on small invertebrates such as brine shrimp (genus Artemia) and brine fly (family Ephydridae) larvae.

The unique Ibisbill (Ibidorhyncha struthersii) has evolved a convergent appearance to the unrelated Ibises (subfamily Threskiornithinae), which are Pelecaniformes. Its long, downward-curved bill is used similarly to the ibises, as it probes under rocks or gravel for aquatic insect larvae.

Another charadriiform to convergently evolve with a pelecaniform is the Spoon-billed Sandpiper (Calidris pygmaea). While it is the size of a typical sandpiper, it has the spoon-shaped bill of a Spoonbill (genus Platalea). It has a similar feeding behavior to spoonbills, moving its bill side-to-side as it walks forward with its head down. However, this sandpiper typically feeds on tundra mosses, as well as small animals like mosquitoes, flies, beetles, and spiders, as well as brine shrimp occasionally. The Spoon-billed Sandpiper is critically endangered, and its population has been decreasing since the 1970s. It is estimated the species may become extinct in 10–20 years if its habitat is not protected. The Spoon-billed Sandpiper was the milestone 13,000th animal photographed for Joel Sartore’s The Photo Ark.

While oystercatchers (genus Haematopus) are monogamous and tend to return to the same nesting site every year, some have been observed “egg dumping”, laying their eggs in the nests of other birds such as gulls.

The Jacanas (family Jacanidae) (image 4) are sometimes referred to as “Jesus Birds” or “Lily Trotters” due to their highly elongated toes and toenails that allow them to spread out their weight while foraging on floating vegetation, giving them the appearance of walking on water. They are one of the rare groups of birds in which females are larger, and several species maintain harems of males in the breeding season with males solely responsible for incubating eggs and taking care of the chicks.

A “snipe hunt” is a type of practical joke or hazing, in existence in summer camps and scout groups in North America as early as the 1840s, in which an unsuspecting newcomer is duped into trying to catch an elusive animal called a snipe, a creature whose description varies. However, snipes (three separate genera in the family Scolopacidae) are actual birds, who search for invertebrates in marshland mud with their long, sensitive bills, and are highly alert. They would be hard to catch in a pillow case.

The Ruff (Calidris pugnax) is notable for having 4 separate sexes: 1 female and 3 types of male. The most common male, called the “territorial male” has a black or chestnut ruff, is much larger than the female, and stakes out a small mating territory in the lek. They perform elaborate displays that include wing fluttering, jumping, standing upright, crouching with their ruff erect, or lunging at rivals. The second type of male is the “satellite male”, which have white or mottled ruffs, are larger than females but smaller than territorial males, and do not occupy territories. Satellite males enter leks and attempt to mate with the females visiting the territories occupied by territorial males. Territorial males tolerate the satellite males because, although they are competitors for mating with the females, the presence of both types of male on a territory attracts additional females. The rarest type of male is the cryptic male, or "faeder", which permanently mimics the females in both size and plumage. Faeders migrate with the larger males and spend the winter with them, but use their appearance to “sneak” into leks and gain access to females. Females often seem to prefer mating with faeders to the more common males, and those males also copulate with faeders (and vice versa) relatively more often than with females. Homosexual copulations may attract females to the lek, like the presence of satellite males. Satellite males seem to be more attracted to faeders, and in homosexual encounters, the faeders are usually “on top”, suggesting that the satellite males know their true identity. The behaviour and appearance of each male Ruff remains constant through its adult life, and is determined by genetics.

The unique buttonquails (family Turnicidae) convergently evolved the small, round shape of the galliform quails. Unlike true quails, the female buttonquail is the more richly colored of the sexes. Both sexes cooperate in building a nest in the earth, but normally only the male incubates the eggs and tends the young, while the female may go on to mate with other males.

The stork-like Crab-plover (Dromas ardeola) is unique among waders for the shape of its bill, specialized for eating crabs, and for making use of ground warmth to aid the incubation of its eggs. The nest burrow temperature is optimal due to solar radiation and the parents are able to leave the nest unattended for as long as 58 hours, protected by large colonies of up to 1,500 pairs. The chicks are also unique for for being less precocial than other waders, and are unable to walk and remain in the nest for several days after hatching, having food brought to them. Even once they fledge they have a long period of parental care afterwards.

The skimmers (genus Rynchops) are the only birds which have a built-in underbite, where the lower mandible is longer than the upper. This adaptation allows them to fish in a unique way, flying low and fast over streams, letting their lower mandible skim over the water's surface, ready to snap shut the moment it touches a fish.

The Black Skimmer (Rynchops niger) is the only species of bird known to have slit-shaped pupils.

Gulls, Skimmers, and Noddies can see ultraviolet light.

The snow-white, pigeon-like Ivory Gull (Pagophila eburnea) breeds in the high Arctic and is an opportunistic scavenger. It has been known to follow Polar Bears (Ursus maritimus) and other predators to feed on the remains of their kills.

Some species of gull, such as the Laughing Gull (Leucophaeus atricilla) and Great Black-backed Gull (Larus marinus) have adapted to live alongside humans in places where humans have overtaken their habitat. These gulls have little fear of humans, and will pirate food from them just as they would any other animal.

Auks are superficially similar to penguins, having black-and-white colours, upright posture, and adaptations for swimming underwater. However, they are an example of convergent evolution, and are not closely related to penguins. Auks fill the niche of penguins around the arctic, while penguins fill the niche of auks around the antarctic.

In fact, the extinct, flightless Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis) was the original “penguin”. Penguin was the Spanish, Portuguese and French name for the species, derived from the Latin pinguis, meaning "plump". The penguins of the Southern Hemisphere were named after it because of their similar appearance and flightlessness. The last two confirmed Great Auks were killed on Eldey, off the coast of Iceland, on June 3, 1844.

193 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have any prions? The bird. The birds with the common name of "prion".

PRIONS aka "Whalebirds"

Prions are Petrels in the genus Pachyptila. Also called "whalebirds", because some species feed near feeding or surfacing whales.

These pelagic birds feed mainly of marine invertebrates and small fishes.

Dove or Antarctic Prion (Pachyptila desolata), family Procellariidae, order Procellariiformes, found in the Southern Ocean

photograph by JJ Harrison

Fairy Prion (Pachyptila turtur) at the nest, family Procellariidae, order Procellariiformes, found in the southern coastal areas near the Sout America, Australia, and Southern Africa in the Southern Ocean

photograph by ZooPro

Fairy Prion (Pachyptila turtur), family Procellariidae, order Procellariiformes, East of Eaglehawk Neck, Tasmania, Australia

photograph by Christopher Watson

#pachyptila#prion#petrel#seabird#procellariidae#procellariiformes#tubenose#bird#ornithology#animals#nature#ocean

351 notes

·

View notes

Text

Бабочка-енот, лунула — Chaetodon lunula. Бабочка-енот, лунула (Chaetodon lunula, raccoon butterflyfish) — узнаваемая рыба бабочка с красивой, выразительной окраской. Максимальная длина лунулы 21 см. Тело и плавники окрашены в желтый цвет, темнеющий ближе к спине и иногда переходящий практически в черный. На боках от грудных плавников к хвосту идут диагональные темные полосы. На морде контрастная маска: черная полоса, проходящая через лоб и маскирующая глаза, и следующая за ней белая, почти такой же ширины. От заднего края этой белой полосы к основанию спинного плавника тянется сужающаяся черная полоса, окаймленная светло-желтыми участками. На хвостовом стебле округлое черное пятно, переходящее в темное основание спинного плавника. Молодые отличаются более светлым, белесым рострумом и округлым черным пятном на задней лопасти спинного плавника.

Населяет мелководные лагуны и внешние склоны рифов. Держится на глубине до 30 метров, парами или небольшими группами. Одна из немногих бабочек, ведущих ночной образ жизни. Питается преимущественно голожаберными моллюсками, кольчатыми червями и другими донными беспозвоночными, однако нередко поедает коралловые полипы и водоросли. Молодые предпочитают каменистые участки на прибрежных рифах в приливно-оливной зоне.

Дайверы и другие любители коралловых лесов могут встретить этот вид бабочек в лагунах и на внешних склонах рифов Индо-Пацифики: от востока Африки, у Мальдивских островов, далее оги��ая Австралию, где они обитают у берегов Индонезии, Папуа-Новой Гвинеи и Фиджи, и дальше в Океанию, где их можно лицезреть у Гавайев, а с юга – недалеко от берегов Таити — и это лишь малая доля их мест обитания. Иногда они встречаются на юго-востоке Атлантического океана.

Raccoon butterflyfish, lunula — Chaetodon lunula. Raccoon butterflyfish, lunula (Chaetodon lunula, raccoon butterflyfish) is a recognizable butterfly fish with a beautiful, expressive coloration. The maximum length of the lunula is 21 cm. The body and fins are colored yellow, darkening closer to the back and sometimes turning almost black. On the sides from the pectoral fins to the tail there are diagonal dark stripes. On the muzzle there is a contrasting mask: a black stripe passing across the forehead and masking the eyes, and the following white one, almost the same width. From the rear edge of this white stripe to the base of the dorsal fin there is a tapering black stripe, bordered by light yellow areas. On the caudal peduncle there is a rounded black spot, turning into a dark base of the dorsal fin. Juveniles have a lighter, whitish rostrum and a rounded black spot on the back lobe of the dorsal fin.

Inhabits shallow lagoons and outer reef slopes. Stays at depths of up to 30 meters, in pairs or small groups. One of the few butterflies that lead a nocturnal lifestyle. It feeds mainly on nudibranchs, annelids and other bottom invertebrates, but often eats coral polyps and algae. Juveniles prefer rocky areas on coastal reefs in the tidal-olive zone.

Divers and other coral enthusiasts can encounter this butterfly species in the lagoons and outer reef slopes of the Indo-Pacific: from eastern Africa, near the Maldives, around Australia, where they live off the coasts of Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, and Fiji, and on into Oceania, where they can be seen off Hawaii and, to the south, near the coast of Tahiti, to name just a few of their habitats. They are also occasionally found in the southeastern Atlantic.

Источник: //t.me/+E4YBiErj0A8wOGUy, //www.aqua-shop.ru/live/ morskie_ryby/shchetinozubyue_ryubyu-babochki/prod_H3h60_M, //es.pinterest.com/pin/729301733429659096/, ://vk.com/wall-43552186_885, //www.posterazzi.com/hawaii-school-of-racoon-butterflyfish-chaetodon-lunula-along-reef-posterprint-item-vardpi1989862/.

#fauna#video#animal video#marine life#marine biology#nature#aquatic animals#sea creatures#ocean#sea#fish#Chaetodon lunula#Raccoon butterflyfish#reef#corals#sand#animal photography#beautiful#nature aesthetic#видео#фауна#природнаякрасота#природа#океан#море#Бабочка-енот#рыбы#песок#риф#кораллы

222 notes

·

View notes

Text

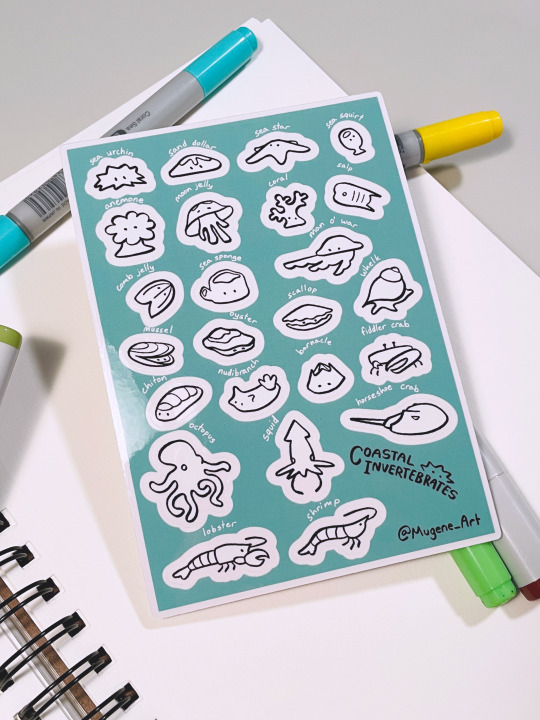

#marine invertebrates#marine biology#invertebrates#shrimp#horseshoe crab#nudibranch#coral#squid#sea anemone#cnidarians#echinoderms#crustacean#mollusk#molluscs#tunicate#sea creatures#sea animals#biology#sticker sheet#stickers#clear stickers#artists on etsy#artists on tumblr#mu's wares

896 notes

·

View notes

Text

InsertAnInvert 2024

Coastal week 1: Tropical reef

bubble-tip anemone (entacmaea guadricolor)

#art#comics#artists on tumblr#screentone#halftone#invertebrates#inverts#sciart#noAI#human artist#queer artist#nonbinary artist#cute#animals#SciArt#insertaninvert2024#insertaninvert#nature#funny little guys#anemone#bubble-tip anemone#ocean#sea#sea creature#ocean animals#trypophobia cw#coastal

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Life-List Series #8: MUDU

Common Name: Muscovy Duck Species: Cairina moschata

Description: A dark-colored duck with green and blue wings, and bare skin around the eyes with red wattles Motto: Waddling the line between wild and domestic.

Conservation: Least Concern Range: Coasts of Mexico and Central America, extending into South America, down to northern Argentina and Uruguay; introduced to Florida, Texas, and the UK Habitat: Tropical wetlands, coastal lagoons, and lowland marshes; varied for introduced populations, but usually in areas near water

Food: Stems, seeds, grasses, aquatic plants and leaves, small fish and reptiles, invertebrates (especially termites) Breeding Info: Polygamous, although males are territorial and aggressive; single-brooders with mostly maternal care and loose paternal contact after hatching; nest-box and tree-hollow users when nesting, with a clutch of 8 - 15 white eggs that hatch precocial young Sound: ...

Ornithologist's Notes: Is the Muscovy duck actually distributed in Florida? Well, yes and no. Fun fact, first off, there isn't a lot of actual work done on wild Muscovy Duck in their South American range. Most papers you'll see focus on the domesticated variety, which is also the version of the duck introduced outside of its range. But even then, do feral ducks count as a wild species in parts of its range? Maybe. In central and southern Florida, the species has populations in the thousands, distributing far outside of domestic settlements, and enmeshing themselves within wild environments. It's not necessarily invasive, and it fits within existing niches with little overlap, except for one closely-related species I'll get to in the next entry. Also, quick note, those white patches vary wildly in the domestic variety, where they're basically just restricted to those big white wing patches in the wild populations. Is that from introgression from domestic mallards, or a result of hybridization? Maybe. Is that because of the fixing of a deleterious copy of the MYOT and MB gene pairing that controls melanization, alongside differential expression throughout the feathers dependent on some mystery of genomic structure? Very well could be? Are there any papers on that comparison? Not yet. We'll see, though.

Life List Notes: Does this count as a life-list bird? I think so! To be clear, I saw these guys for the first time in central Florida (Orlando), and while they were around a human settlement, they weren't kept in a domestic setting, and seemed like a wild (or feral) flock that had arrived to the water-dominated resort independently, rather than being brought there and fed there. What's more, they weren't heavily domesticated, and at least appeared to be pure Muscovy Duck, rather than hybrids with Mallards (Anas platyrhynchos) or other domesticated duck species. Plus, Florida birders seem to think that these count for life-lists, since they're independently distributed and established. So, does it count? We're gonna say yes! And now, for the next one, we move on to a species that definitely counts for the life-list...even if it is a really common duck to see. Also, we're in ducks now! Excited, I love ducks.

Previous: TRSW

Next: WODU

#birds#birding#birdwatching#birdblr#birblr#birder#black birder#birds of tumblr#life list#bird life list#duck#muscovy duck#cairina#cairina moschata#art#artist#bird art#stylized#sticker#sticker art#domestic duck

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wet Beast Wednesday: vaquita

This is the 2-year anniversary of me writing weekly posts about the biology and ecology of aquatic animals. The very first one I ever wrote was on the vaquita, the world's smallest and most endangered cetacean. That post was pretty clumsy and I didn't settle into my style until later, so for the anniversary, I'm going to redo it. This may be shorter than many of my WBW posts because there's not a whole lot we know about these animals.

(Image: a vaquita swimming just below the surface of the water. It is a small, grey porpoise with a rounded, snoutless head. There are black markings around its eyes and mouth. and a dark strip that runs from the cheeks to the pectoral fins. End ID)

The vaquita (Phocoena sinus) is a tiny porpoise that reaches a maximum of 150 cm (5 ft) and 68 kg (150 lbs). Porpoises are the smallest of the cetaceans and vaquitas are the smallest of them. Vaquitas have a dolphin-like shape, but without a noticeable beak, giving them rounded heads. Their dorsal fins are unusually long for a cetacean of their size. Vaquitas have light grey bodies with white underbellies that provide countershading. When something looks down on a vaquita from above, its darker body blends in with the sea floor. When something looks up at a vaquita from below, its white underbelly blends in with the sunlight. Vaquitas can be recognized by the dark markings around the eyes and mouth and a dark stripe that runs from the cheek to the pectoral fins.

(Image: a close-up of a vaquita's head poking out of the water. The dark markings around the yes and mouth and the stripe are clearly visible. End ID)

Vaquitas are found only in the northernmost reach of the Gulf of California, also known as the Sea of Cortez. The Gulf is one of the most ecologically diverse seas in the world, with vast quantities of life fed by the output of the Colorado and other rivers. Vaquitas have a range of roughly 3885 square km (1500 square miles), the smallest of any cetacean. They may have spanned the length of the Gulf before they became endangered. Vaquitas live in shallow, coastal waters, rarely living in water more than 50 m (164 ft) deep. They will enter and hunt in estuaries and lagoons so shallow the do not fully submerge the animal. Vaquitas are unique amongst porpoises for inhabiting warm water and being able to tolerate a wide range of temperatures. They are predators of fish, squid, and other invertebrates. Juveniles hunt fish in the water column while adults primarily target bottom-dwellers. They play an ecological role of transporting nutrients from the seafloor back into thee water column. Vaquitas are found either alone or in small pods. It is common among cetaceans for females and juveniles to form pods while makes either swim alone or with other males. This may be the case with vaquitas as well. Mating occurs in spring and summer, with a gestation period of 11 months. Calves are born one at a time weighing as little as 9 kg (20 lbs) and nurse for less than a year before weaning. Females mate every other year and the estimated life span is 21 years.

(Image: a pair of vaquitas swimming. Both have their heads poking out of the water to breathe. End ID)

The vaquita is one of the least well-known cetaceans. It was only formally classified as an animal in 1958 based on the discovery of their skulls. We know very little about them and may soon lose them forever. The total population is estimated to be less than 10 as of this year, making them the most endangered marine mammal in the world. The biggest threat to vaquitas is gill nets. The Gulf of California is home to major poaching operations for the totoaba drum (Totoaba macdonaldi), whose swim bladders are considered a delicacy and used for quack medicine in China. Totoaba are a similar size to vaquitas and so the gill nets used to catch them are also very likely to entangle vaquitas, who then drown. The vaquita's range was legally protected from gill net fishing by the governments of Mexico and the United States, but poaching continues despite patrols and the placing of structures intended to damage nets. Current conservation efforts largely focus on population monitoring and the detection and removal of illegal gill nets as well as attempted disruption of the black market totoaba trade. Colossal Biosciences, a company that is trying to revive recently extinct species such as the woolly mammoth and thylacine, has announced a plan to obtain and store Vaquita DNA to possibly revive the species if it goes extinct. Previous attempts to capture and breed vaquitas in captivity failed after the animals died of stress. Shrimp nets also pose a risk of bycatch and 80% of shrimp caught in the northern Gulf are eaten in the USA. It is useful to research where the fish and shrimp you eat comes from to avoid buying shrimp caught in Vaquita habitat. Other threats include habitat change driven by the damming of the Colorado River and pollution. Some biologists consider the vaquita to be functionally extinct, meaning that even if conservation efforts are immediately effective, the population is so low that they are below the minimum viable population needed to sustain viable genetic diversity and will go extinct anyway.

(Image: a vaquita being handles by conservationists. Two people are holding it out of the water. End ID)

I've had a lot of fun doing this series and have learned a lot about new and interesting animals. This series, (especially the bonnethead shark post) helped me expand from a nobody blog to having lots of followers and making friends. I started the series to encourage me to use Tumblr more and its safe to say that worked out. Thanks for reading and enjoying these posts. Here's to year 3.

#wet beast wednesday#vaquita#porpoise#cetacean#cetaceans#endangered species#extinction#critically endangered#marine biology#marine mammals#marine life#biology#ecology#zoology#animal facts#image described#informative#educational

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

Good morning yall! Hope you're ready for a new fish today cuz we got an all timer here today!

Today's fish is none other than my personal favorite fish, the Brook Trout (salvelinus fontinalis)! These beauties are native to Eastern North America, in both Canada and the United States, ranging from Lake Superior, to the coastal waterways from the Hudson Bay to Long Island, though they have spread far beyond their native ranges, mostly via aquacultural practices and artificial propagation, making them invasive species in many regions of North America and the world at large!

Two ecological forms of Brook Trout have been recognized by the US Forest Service, the longer-living potamodromous (fish whose migration occurs fully within fresh water) population, known as coasters , and the anadromous (fish whose migration occurs from fresh water to salt water) population, known as salters. Adult coasters typically reach lengths over 2 feet in length and weigh up to 15lbs, compared to adult salters, which average between 6 to 15 inches and about 5lbs. They're characterized by their vibrant coloration, with olive green bodies and spectacular yellow and blue rimmed red spots, white and black trimming along their orange fins, and dense, irregular lines along the top of their bodies. Often, the bellies of male Brook Trout becomes bright red or orange when spawning.

During the spawning season, female Brook Trout will construct a depression in the stream bed, referred to as a "redd", where groundwater percolates upward through the gravel. Male Brook Trout will approach the female, fertilizing the eggs. The eggs are only slightly denser than water, and can easily be swept away by the current. To avoid this, the female will bury the eggs in a small gravel mound, from which they hatch 4 to 6 weeks later. During this incubation period, the eggs receive oxygen from the streamwater that passes through the gravel beds and into their gelatinous shells. Once they hatch into small fry fish that retain their yolk sack for nutrients, which compensates for the lack of nutrients provided by the parents during the early stages of development. Following the consumption of the yolk, the fry Brook Trout will shelter from predatory species in rocky crevices and inlets, growing from fry to fingerlings, until reaching full maturation at the ripe old age of 6 months.

Despite their native range spanning across low-elevation lakes and watersheds, Brook Trout are increasingly confined to higher elevations in the Appalachian Mountains, especially in southern regions of Appalachia. Over seas, however, Brook Trout have thrived in introduced populations in much of Europe, Argentina, and New Zealand since as early as the 1850's! Their typical habitats include large and small lakes, rivers, creeks, and spring ponds in cold temperate climates. They thrive in clear spring water with moderate flow rates and healthy vegetation populations and other resources which provide natural hiding places. Although they are more resilient and adaptable to varying environmental changes, such as pH levels and temperatures, Brook Trout struggle in temperatures warmer than 72 degrees Fahrenheit. Their diets include aquatic insects at all stages of life, adult terrestrial insects such as grasshoppers and crickets, crustaceans and frogs, molluscs, invertebrates, smaller fish, and even small aquatic mammals such as voles, and even other young Brook Trout! This highly indiscriminate diet and environmental resiliency allows for their success across the globe.

Given all of this, Brook Trout are classified as a Secure by NatureServe's conservation metrics, but that label may be misleading; these incredible fish face severe and repeated extirpation (localized extinction) in many of their native habitats due to habitat destruction, pollution, damming, and invasive species. Meanwhile, Brook Trout present the danger of extirpation to other fish in their nonnative habitats, indicating that efforts must be taken to curb these populations. In short, there are more than enough Brook Trout, but they simply are not where they are meant to be.

A true fish out of (the specifically correct body of) water, the Brook Trout scores within the top percentile of all fishies on our highly advanced fish ranking scale.

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Armadiles, surface molrocks in the "stem-rattiles" branch of the cladistic tree, were among the first of the molrock family to attain large predatory niches in the Glaciocene. Dominating as the top predators of Fissor, the armadiles preyed on walkabies, rhinocheirids and rattiles alike, spreading onto the Gestaltian mainland when Fissor at last collided with the landmass.

But while the armadiles were initially successful, they would ultimately be a short-lived early experiment in the molrock evolutionary path. They had, unfortunately, spread out during the Glaciocene: a time of cold periods and unpredictable weather, which proved to be disastrous to the armadiles when their ectothermic metabolisms made them barely functional on cold days. Their smaller cousins, the rattiles, were able to endure by becoming dormant and subsisting on small insects and invertebrates, but the Glaciocene and its clime was no time and place for a large, cold-blooded terrestrial carnivore to thrive.

The last surviving species would be the armored brushscute (Pilosquamomys minimus), a species native to northern Gestaltia in the Late Glaciocene, 115 million years PE. A relatively small species weighing two kilograms, it ended up outliving the other armadiles due to its size, meaning it needed less food to survive and could subsist on smaller prey like furbils and duskmice as well as a variety of invertebrates. Brushscutes would enjoy a fair amount of success, inhabiting habitats such as coastal shores, grasslands and temperate forests, and hibernated through the cold winters, taking advantage of brief summers to replenish their stores of food as well as breed. With their very slow metabolisms, their gestation periods were equally long, roughly almost a year: at the end of a summer the females would mate, go dormant, and pass their entire duration of pregnancy during a state of hibernation, birthing their young when they awaken next year to a dozen or so already-independent young that nursed only very briefly before leaving for good: an earlier remnant of a trend that led to rattiles eventually fully abandoning lactation only to re-evolve numerous branches of male-centered parental care now that this constraint was no longer a problem.

Unfortunately, the last of the armadiles would meet their end at the final cold snap of the Late Glaciocene, bringing about harsh winters even they in their hibernation would not survive. The smaller rattiles, better able to wait out the cold with fewer needs, would make it through the brief period of extreme temperatures and begin to re-diversify in the Temperocene, with some, such as the garitors and the varats, eventually coming to fill the empty niches of large predators that the armadiles had left vacant.

----------

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#speculative zoology#spec evo#hamster's paradise#species profile

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

February 12, 2025 - Blue Malkoha or Chattering Yellowbill (Ceuthmochares aereus) These cuckoos are found in and around forests, sometimes near rivers, or in coastal scrub. Foraging alone, in pairs, or in small groups, they feed on insects and other invertebrates as well as tree frogs, fruits, seeds, and leaves, sometimes following mixed-species flocks or squirrels to capture fleeing insects. Their nests are open or domed masses of sticks built in thick vegetation where females lay clutches of one to four eggs. Both parents care for the chicks.

66 notes

·

View notes