#cinerama orchestra

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Alex North & Cinerama Orchestra: South Seas Adventure (1958)

Audio Fidelity Inc.

#my vinyl playlist#alex north#cinerama orchestra#cinerama#audio fidelity inc#movie soundtrack#movie score#folk music#world music#1950’s music#pacific islander music#record cover#album cover#album art#vinyl records

1 note

·

View note

Photo

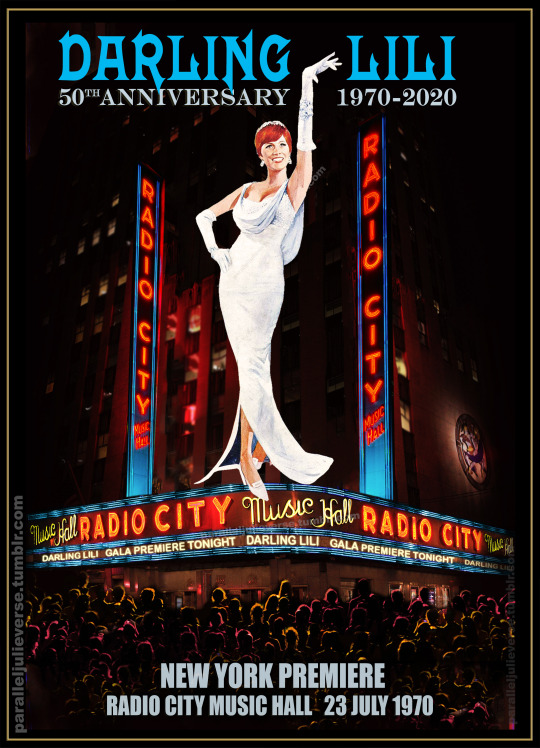

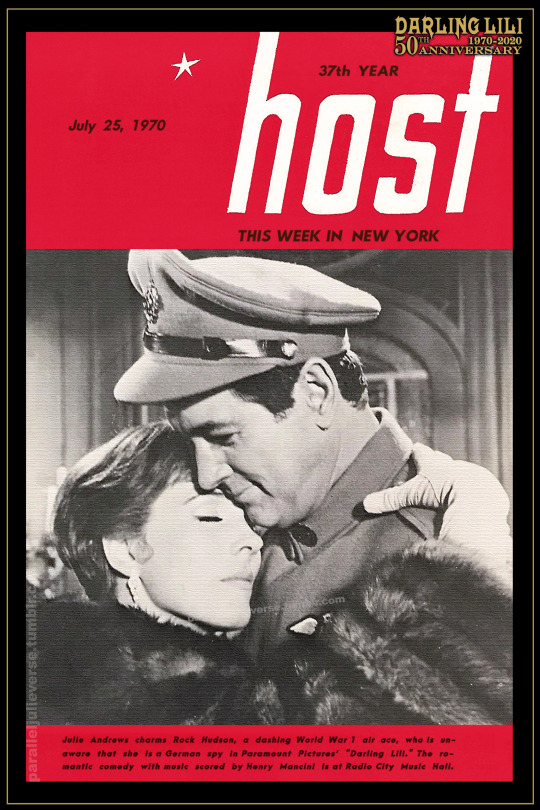

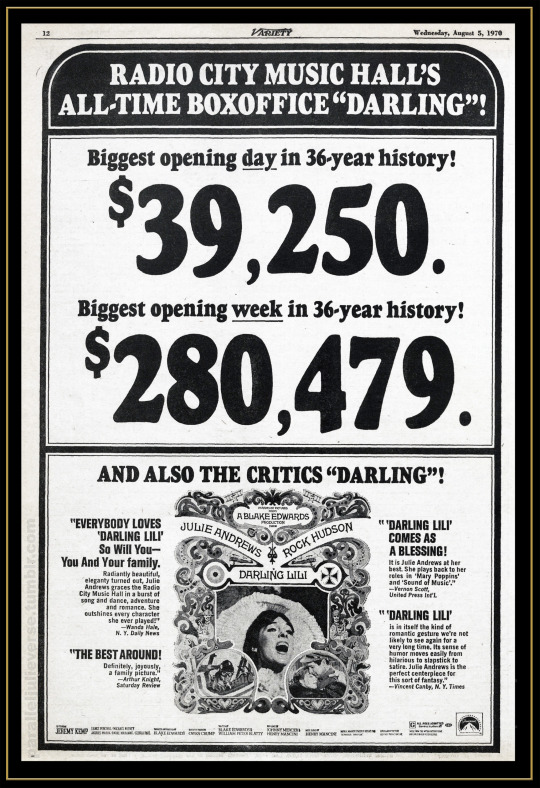

Darling Lili in New York, or Where Were You the Night Julie Andrews Played Radio City Music Hall and Stole Manhattan’s Heart?

This is the second in a series of commemorative posts to mark the 50th anniversary of Darling Lili, the last of the 1960s Julie Andrews screen musicals. In the preceding post, we looked at the film’s fraught production history up to and including its World Premiere at Hollywood’s Cinerama Dome on 23 June 1970. Here, we turn attention to the film’s New York bow which took place a month later on 23 July at the city’s fabled Radio City Music Hall.

Nicknamed “the show place of the nation”, Radio City Music Hall was for much of the mid-twentieth century the venue of choice for big event film releases. The theatre’s monumental size, architectural opulence, state-of-the-art technology, and pre-show stage spectacles made it “the quintessential motion picture palace,” and Hollywood studios jockeyed to secure bookings at “the Hall” for their most prestigious pictures (Goldman, 97-98).

During the late-60s, Paramount, the studio behind Darling Lili, enjoyed a run of extremely successful summer bookings at Radio City Music Hall. Its 1967 release, Barefoot in the Park broke house records for the longest run at the Hall with a 12-week season, only to be bested the following year by another Paramount comedy, The Odd Couple which ran for 14-weeks (”Trouble”, 114). It was something of a PR coup, therefore, when, in January 1970, Paramount announced with much fanfare that Darling Lili would make its official premiere as the summer attraction at Radio City Music Hall later in the year (”Par Gets”, 3). The deal even made the front cover of Boxoffice magazine with a photo of Frank Yablans, Paramount general sales manager, proudly signing the booking contract with Music Hall president, James F. Gould (″Sign of Summer,”, cover).

Barely had the ink dried on the deal, however, when Paramount changed tack. Hit by the toughest industry recession in decades and spooked by a precipitous downturn in the market for big-budget roadshow films, Paramount execs implemented a wholesale revision of studio operations, including a brutal hard-prune of their production and release schedules (Dick, 120ff). By April, earlier plans to give Darling Lili a high profile release had been ditched and, in its stead, Paramount decided to offload the film cheaply as part of a bundle of eight titles slated for saturation release during the summer off-season. Dubbed the “Big Summer Playoff,” the aim was to issue the films widely and quickly so that they could “saturate every major and minor market with single-house firstruns and key city multiples” (“Paramount’s Summer Playoff”, 5). In an era when important films were typically given carefully staggered roll-outs, it was an unorthodox move that fuelled advance perceptions of Darling Lili as a bomb of such magnitude that even its own studio had lost hope. As one newspaper commentator put it, Paramount “seems to have dumped the expensive movie rather than spend any more on it” (Taylor, 21-E).

Radio City Music Hall, by contrast, stuck to its original plans to exhibit Darling Lili as a high-profile summer spectacular. With Paramount having started to issue the film haphazardly to theatres across the nation in June, the opening of Darling Lili at Radio City on July 23 would no longer be a world premiere -- that honour was hastily devolved to Hollywood’s Cinerama Dome -- but the Hall persisted in proudly billing its run as “the New York premiere”. As Variety wryly noted: “Music Hall has never played a pic which hasn’t been a New York first, although perhaps someone there thought the tourists may have thought Lili was otherwise in that the film opened nationally a month ago” (”New York”, 20).

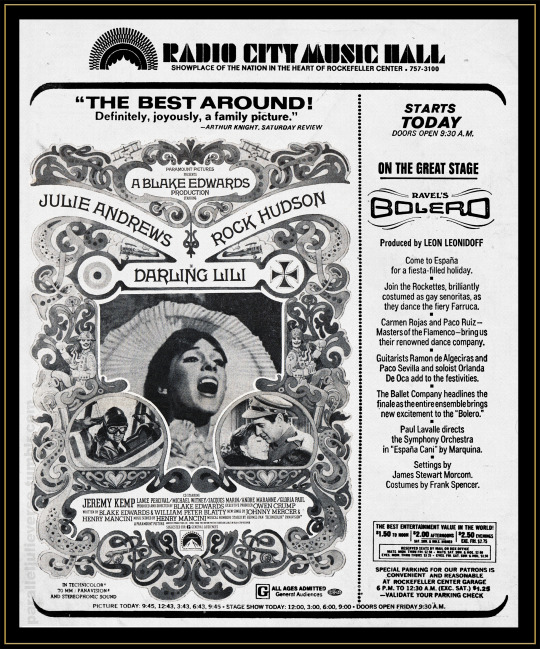

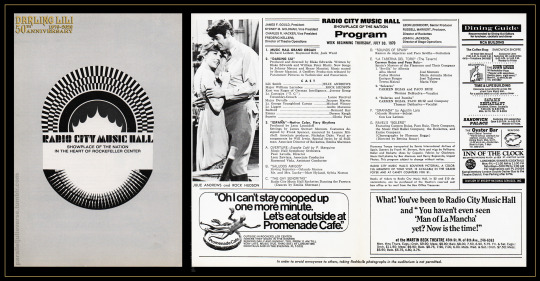

While not strictly a roadshow presentation, Radio City Music Hall exhibited Darling Lili with all the trappings of a hardticket prestige release. Seats were available via a mix of both premium reserved and general admission with special complimentary programs issued to patrons at all sessions. The theatre screened the film in wide-gauge 70mm with 6-track stereophonic sound, one of only two US venues to do so. Projected on the Hall’s 70′x40′ motion picture screen -- the largest indoor screen in the world at the time -- the film would have looked and sounded amazing (Goldman, 99). As an added point of appeal, screenings were supported by one of the Hall‘s famous live stage entertainments: in this case, a Spanish-themed spectacular with symphony orchestra, flamenco dancers, guitarists and, of course, the legendary high-kicking Rockettes (Jose, 54). In addition, the Hall lavished Darling Lili with a solid promotional buildup, taking out full page ads in key newspapers, and using strategically-placed billboards and transit ads around town.

It was an old-school approach of event-style cinema showmanship that paid off handsomely. Even before Darling Lili opened at the Hall, there was “an unprecedented advance demand” for tickets, leading the theatre to double the number of reserved seats from 900 to 1,800 for all sessions. “We’ve added reserve seats on a few occasions previously,” observed a theatre rep, but “only during the heavily crowded Christmas and Easter holiday seasons” and never...during the summer,” adding that he had “no idea” what had generated the extraordinary advance demand (Weiler, 37).

The good news continued when the film opened on July 23 with a box-office rush that broke all house records, prompting the theatre to increase reserve bookings even further to 2500 seats in an effort to accommodate the clamour for tickets (“’Lili’ Hitting Peak,” E-2). As Variety commented:

“Radio City’s Darling Lili...is the summer blockbuster all the auspices hoped it would be, with $285,000 or close expected for kickoff session. Pic is curious in that its longtime postproduction shelving had spurred rumors of disastrous artistic results. But film has shown legs in crosscountry openings and both critical and word-of-mouth opinion in Manhattan has been mixed at worst. Some response is downright enthusiastic” (“’Lili’ and Revue,” 9).

Darling Lili continued its bullish box-office run in New York, long after any initial novelty buzz should have subsided. Weekly grosses inched higher for a few weeks before settling into a very healthy $200K+ per week plateau. Come mid-August, Variety noted with thinly-veiled surprise that:

“Radio City Music Hall is experiencing a slight phenomenon with its current Darling Lili attraction. It’s not unusual during the summer tourist season for popular Hall programs to maintain or build grosses...but few remain in such a narrow range as has Lili to date. First week tally of $280,000 was a non-holiday record. Second was upped to $288,000. Now third session is headed for $280,000....70mm projection and sound are plus-values in a package which Hall president James Gould predicts will run until late September” (“N.Y. Full,” 9).

In the end Darling Lili did run at Radio City Music Hall until late-September -- September 23, to be precise -- when it closed to make way for the pre-booked Sophia Loren-vehicle, Sunflower. Across its 9-week run, the film grossed in excess of $2million in ticket sales, making it one of the theatre’s biggest summer hits to date (“Picture Grosses,” 15).

The commercial success of Darling Lili at the Hall was music to the ears of the film’s star who, in a rare moment of unguarded hubris, admitted to a measure of self-satisfaction at news of the booming box office receipts:

“‘I’m not so interested for myself,’ she explained, ‘but I’m happy for Blake. He has been so maligned about this picture that I am delighted he is receiving some vindication...I think he managed to make a vastly enjoyable film...People are entertained by it; the Music Hall figures seem to prove that.’ [T]he actress had mild reproof for the releasing company, Paramount, over its handling of the film: ‘Three weeks before the opening, there was no advertising campaign. None whatsoever. Paramount didn’t seem to know how it was going to sell the picture--or if. I simply can’t understand an attitude like that’” (Thomas: 13).

Julie’s chiding of Paramount for its poor handling of Darling Lili was not mere sour grapes. Once the studio had decided to issue the film as part of a summer saturation bundle, it effectively abandoned any semblance of cogent or even halfway organised marketing. As outlined in our earlier post, there was little rationale to the film’s distribution. Lili appeared suddenly and briefly at second-run theatres and drive-ins across disparate suburban and provincial areas, while major metropolitan venues didn’t get the film till much later, if at all. In many markets, the film was booked for a fleeting season of a week or two – in some cases, just a few days -- and it was frequently paired as a double-bill with a host of poorly selected partner titles (Caen, 6-B).

The studio’s approach to promotion was no better. A generic pressbook and merchandising manual was issued, but it was very bare-bones and perfunctory. In the absence of a clear marketing plan, local exhibitors were left to promote the film more or less any way they liked. Advertisements were frequently altered to pitch Darling Lili in diverse, and often contradictory, ways. The main advertising art provided by Paramount -- with its central image of Julie in mid-song set within a sepia frame of art nouveau swirls -- positioned the film principally as a nostalgic star musical with touches of adult romance. Many local exhibitors took a very different approach. Some tried to reframe it as wholesome child-friendly fare: “This summer’s one and only total family entertainment;” “It’s Julie at her best! It’s for your family” (“This Summer,” 24). Other theatres pegged it as “a man’s movie,” stressing the action and warfare elements with taglines like “See the Best Dogfights of World War I” or “If you enjoyed Blue Max you’ll love Darling Lili” (“Man’s Movie”, 13; “Palms”, 64). Some exhibitors even openly recycled graphics from The Blue Max and other WW1 action films, with one Florida venue going so far as to revive the film’s original working title: Darling Lili, or Where Were You the Night You Said You Shot Down Baron Von Richtofen? (“Amusements,” 11A).

Elsewhere, exhibitors implemented a rash of dubious promotional incentives such as “twofers” or free entry to "one child under 12...with the purchase of one adult admission to Darling Lili” (“Capri”, 2D). A theatre in Fort Lauderdale offered “free admission to World War I veterans in uniform during matinees Monday through Friday” (“’Darling Lili’ Ducats,” 5D). Possibly well-intentioned gestures but it was bottom-barrel marketing that fostered an unfortunate aura of abject desperation around the film that likely turned off more patrons than it enticed.

Against this sorry backdrop of shambolic distribution and ham-fisted marketing, the meticulous handling of Darling Lili at Radio City Music Hall served as a strikingly singular counterpoint. The remarkable commercial success of the film at that venue -- which, if reported figures are to be believed, represented well over a third of the film’s entire US grosses (“US Films,” 184) -- can only be attributed in good part to the care and professionalism with which the Hall managed the film’s exhibition. One can’t help but wonder, therefore, how different the overall commercial fate of Darling Lili might have been had Paramount exercised a more discriminating distribution plan, affording the film the kind of special-event release it enjoyed in New York. It’s unlikely Lili would ever have been a major hit -- it was simply too narrow in appeal and out-of-step with the rapidly changing times -- but it certainly could have gone much further in recouping costs and might even have realised a modest profit. At a minimum, it would have helped redeem the film from its unjust reputation as the “Edsel that almost bankrupted Paramount Pictures” (Rosenfield, 5).

As a coda to this account of the exceptional history of Darling Lili at the Radio City Music Hall, it is interesting to note that the film fared well in New York not just commercially but also critically, Some of the film’s best US reviews came from New York critics -- a surprising turn-of-events given how notoriously hostile the East Coast critical establishment had been to Julie Andrews’ earlier screen musicals. Wanda Hale of the New York Daily News gave Darling Lili three-and-a-half stars out of four, writing:

“Radiantly beautiful, elegantly turned out, Julie Andrews graces Radio City Music Hall in a burst of song and dance, adventure and romance...[I]t’s Darling Lili everybody loves, so will you, you Music Hall patrons--you and the family” (Hale, 39).

Vincent Canby (1970) of the New York Times found Darling Lili “a pure if not perfect comedy” with “a lot of perverse charm and real cinematic beauty.” He continued:

“Although Julie Andrews (the film, not stage, star) has always struck me as a very mitigated delight, she may be the perfect centerpiece for this sort of fantasy. That is, her angular, aggressive profile, combined with her coolness and precision as a comedienne and a singer, give the immediate, comic lie to the adventures of a supposedly irresistible femme fatale. She thus is immensely funny...” (16).

In a rare honour, the New York Times afforded Darling Lili a second review from Roger Greenspan (1970) who argued for the film as a minor masterpiece of refined, borderline philosophical, sensibilities. “[O]ne very bright critic I know...has already compared the film, ecstatically, with Max Ophul’s great Lola Montes,” he remarked before launching into his own rhapsodic paean:

“To her characterisation, Miss Andrews brings a precision of gesture that matches Edwards’s directorial precision and that constitutes one of the most excitingly controlled expressions of theatrical presence I have ever seen in a movie. Not cold; elegant, finely drawn, perfect of its period--and yet inward, self-sustaining, as if already committed to that gorgeously contemplative state of transport that is the subject of the movie within the movie to look for in Darling Lili” (S2-10).

In a similar move, the inaugural issue of the New York-based cinephile journal, On Film devoted not one but two essay-tributes to Darling Lili from Stuart Byron and Mike Prokosch respectively. The former gushed:

“Darling Lili comes at the end of the big-budget musical cycle, and it [is] one of the only...good things to come out of the whole rotten effort to reduplicate The Sound of Music. But in any case, a masterpiece it is--Blake Edwards’ most beautiful film to date and surely his most meaningful. ... Edwards is the first director to utilise Julie Andrews’ full resources. Her rapid manner of speaking becomes the neutral fulcrum of her moods--it is sincerity hiding danger, or bitterness hiding love. Her singing, however tender on the surface, always gives the impression of concealing a quick intelligence ready to spring forth when needed” (Byron 1970, 31, 34).

Prokosch (1970) was equally smitten, calling Darling Lili “the only work of art Hollywood ha[s] released in 1970″:

“First. one must forget one’s preconceptions of Julie Andrews and look at the way Blake Edwards, the film’s director, casts his wife with remarkable shrewdness: Lili Smith is a young British singer caught in a situation she cannot master. What more natural part could Julie Andrews want? ... Darling Lili is really gutsy in its formal expression...Edwards’ control of the...formal means at his disposal--stylized lighting and colour, split-up background compositions, and especially cutting--displays a...complete knowledge of their emotional effect. What makes Darling Lili unique among recent releases, though, is its careful structuring. Almost every sequence...takes a clear place in the design of the film” (96).

If it sounds like these critics were a little woozy on the then new wine of auteur film theory, a measure of sobriety was served by none other than Andrew Sarris, chief architect of American auteurism, who filed a somewhat more reserved, but nevertheless appreciative, review of Darling Lili for the Village Voice:

“Darling Lili is cinema a la folie, a rhapsody of romantic madness amid the current cacophony of absurdist dissonances, a sentimental valentine from Blake Edwards to Julie Andrews complete with gypsy violins and a Snoopy sub-plot about the Red Baron and the Dawn Patrol...but I’m afraid it won’t work for most audiences on any level. Its ingredients -- romance, satire, musical comedy, deadpan farce -- mix without blending. The song numbers don’t soar high enough and the prats don’t fall hard enough. But Darling Lili is never less than likeable, and its graceful professionalism is especially refreshing in this long hot summer of assorted crudities” (Sarris 1970, 47).

Despite his reservations, Sarris still included Darling Lili in his end-of-year list of the best films of 1970 -- as did several other Village Voice critics: Stuart Byron, Richard Corliss, Stephen Gottlieb, and William Paul (Sarris 1971, 59).

Now, if only the critics and audiences west of the Hudson had shown Darling Lili half-as-much love as the crowds at New York’s Radio City Music Hall, who knows how different the course of Hollywood history -- or at least that of the Julie Andrews screen musical -- might have been...

Sources:

“Amusements Today.” Florida Today. 2 October 1970: 11A.

Byron, Stuart. “Darling Lili.” On Film. 1: 1, 1970: 30-34.

Caen, Herb. “It’s News to Me.” Hartford Sentinel. 5 August 1970: 6-B.

Canby, Vincent. “Screen: ‘Darling Lili’ Sets the Stage for Pure Comedy of Romantic gestures.” New York Times. 24 July 1970: 16.

“Capri: Florentines! Something Wonderful! Has Happened to the Movies!” Florence Morning News. 12 August 1970: 2-A.

“‘Darling Lili’ Ducats Pared for Retirees.” Fort Lauderdale News and Sun-Sentinel. 27 June 1970: 5D.

Dick, Bernard F. Engulfed: The Death of Paramount Pictures and the Birth of Corporate Hollywood. Louisville, KY: University of Kentucky Press, 2001.

Francisco, Charles. The Radio City Music Hall: An Affectionate History of the World's Greatest Theater. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1979.

Goldman, Harry. “Radio City Music Hall.” Journal of American Culture. 1 1, Spring 1978: 96-111.

Greenspan. Roger. “Oh! What a Lovely Spy.” New York Times. 9 August 1970: S2-1, 10.

Hale, Wanda. “Darling Julie Sparkles as Musical Spy.” Daily News. 24 July 1970: 57.

Jose, “House Review: Music Hall N.Y.” Variety. 29 July 1970: 54.

“’Lili’ and Revues, Tally Darling 285G.” Variety. 29 July 1970: 9.

“’Lili’ Hitting Peak.” Boxoffice. 10 August 1970: E-2.

“Man’s Movie.” Winona Daily News. 7 August 1970: 13.

“N.Y. Full of Tourists; Divided Between ‘Darling’ and ‘Denmark’.” Variety. 12 August 1970: 9.

“New York Sound Track.” Variety. 29 July 1970: 20.

“Palms Advertisement.” Arizona Republic. 31 July 1970: 64.

“Par Gets Hall’s Summer Spot for its ‘Darling Lili’.” Variety. 21 January 1970: 3.

“Paramount’s Summer Playoff Strategy: 5,000 Bookings for Eight Major Films.” Variety. 3 June 1970: 5.

“Picture Grosses: Broadway.” Variety. 23 September 1970: 15.

Prokosch, Mike. “On Film/Feature Film: Darling Lili.” On Film. 1: 1, 1970: 96-97.

“Radio City Music Hall’s All-Time Boxoffice Darling.” Variety. 5 August 1970: 12.

Rosenfield, Paul. “Reconcilable Differences.” Los Angeles Times-Calendar. 12 July 1987: 4-5.

Sarris, Andrew. “Films In Focus: ‘Darling Lili’.” The Village Voice. 13 August 1970: 47, 52.

________. “Films In Focus” The Village Voice. 21 January 1971: 59.

“Sign of Summer.” Boxoffice. 26 January 1970: cover.

Taylor, Robert. “‘Lili’ Can Be Charming.” Oakland Tribune. 27 June 1970: 21-E.

“This Summer’s One and Only Total Family Entertainment.” Tucson Daily Citizen. 5 August 1970: 24

Thomas, Bob. “Julie Andrews Praises ‘Lili’.” Courier-News. 15 September 1970: 13.

“Trouble in Paradise.” Newsweek. 25 October 1971: 113-115.

“U.S. Films’ Share-of-Market Profile.” Variety. 12 May 1971: 36-38, 122, 171-174, 178-179, 182-183, 186-187, 190-191, 205-206.

Weiler, A.H. “Big ‘Darling Lili’ Advance.” New York Times. 23 June 1970: 37.

Copyright © Brett Farmer 2020

#julie andrews#Darling Lili#blake edwards#radio city music hall#old hollywood#musicals#film premiere#new york#1970

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

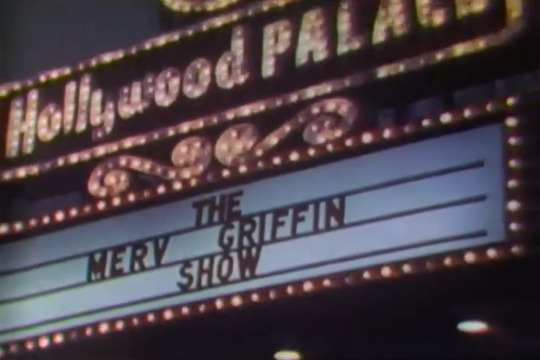

LUCY on MERV

1971-1986

Mervyn Edward Griffin Jr. (1925 – 2007) was an American television host and media mogul. He began his career as a radio and big band singer who went on to appear in film and on Broadway. From 1965 to 1986, Griffin hosted his own talk show, “The Merv Griffin Show.” He also created the internationally popular game shows “Jeopardy!” and “Wheel of Fortune” through his television production companies, Merv Griffin Enterprises and Merv Griffin Entertainment. Both game shows are still airing as of this writing.

“The Merv Griffin Show” ran from October 1962 to March 1963 on NBC; May 1965 to August 1969 in first-run syndication; from 1969 to 1972 late night weeknights on CBS; and again in first-run syndication from 1972 to 1986. The show's longtime bandleader was Mort Lindsey. Griffin frequently clowned and sang novelty songs with trumpeter Jack Sheldon. Griffin's conversational style created the perfect atmosphere for conducting intelligent interviews that could be serious with some and light-hearted with others. Rather than interview a guest for a cursory 5- or 6-minute segment, Merv preferred lengthy, in-depth discussions with many stretching out past 30 minutes. In addition, Griffin sometimes dedicated an entire show to a single person or topic, allowing for greater exploration of his guests’ personality and thoughts. More than 25,000 guests appeared on “The Merv Griffin Show” including numerous significant cultural, political, social and musical icons including four U.S. Presidents. From 1974 to 1986 the show won twelve daytime Emmy Awards.

“The Merv Griffin Show: A Salute To George Marshall” ~ July 29, 1971

Guests: Lucille Ball, George Marshall, Edgar Buchanan, Glenn Ford, William Holden, Mort Lindsay & His Orchestra

Director George Marshall worked with Lucille Ball on Fancy Pants (1950), Valley of the Sun (1942) and 11 1969 episodes of “Here’s Lucy,” mostly location shoots.

“The Merv Griffin Show” ~ October 12, 1973

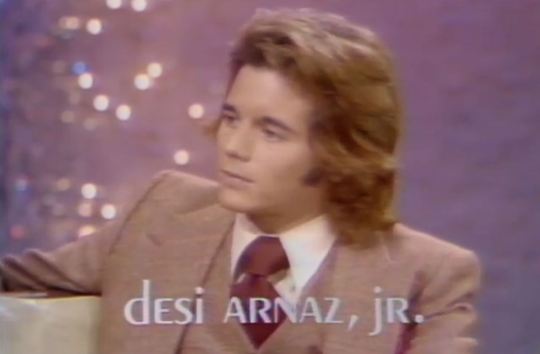

Guests: Lucille Ball, Gary Morton, Desi Arnaz Jr., Lucie Arnaz, Gale Gordon, Robert Lewin, Ronald Reagan (recorded voice message)

A Salute to Lucille Ball featuring her husband and children, and her two most famous co-stars. Ronald Reagan, then Governor of California, calls in.

Lucy says she has finished Mame which won't be released for six months. Merv says the buzz is that the film is one of the best musicals in history. Lucy refutes the rumor that Lisa Kirk dubbed her singing voice. As for dancing, Lucy credits choreographer Ona White with getting her in shape after breaking her leg. Lucy says she wore eight to ten wigs in the picture.

Ball says she usually refers to the ‘Lucy’ character in the the third person.

Lucy says the Goldwyn Girls never wore costumes, only wigs [a slight embellishment]. She mentions Eddie Cantor and Roman Scandals (1933, above).

Merv: “Did a man one day say 'Make her a star?'” Lucy: “No, he said 'make her.'”

Lucy references the “Here's Lucy” episode in which Lucie Arnaz imitates Cher: “The Carters Meet Frankie Avalon” (HL S6;E11) aired a month after this interview, on November 19, 1973.

Lucy says that she met Gary Morton while doing Wildcat on Broadway. She says that she wasn't feeling at her best at the time and had taken on too much. Merv says he knew Gary Morton before Lucy did. Morton jokes that Merv had one voice for speaking and another for singing; the ‘Jim Nabors’ of his time.

Lucy: “The one thing I'm very proud of is that I know my craft.”

Lucy says that her daughter is the more successfully independent. She says her son is independent, but not sure how successful it is.

They talk about their neighbor, Jimmy Stewart and how he walks his big dogs around the block. Lucy says that Jimmy and Gloria Stewart have a huge vegetable garden. A Romanian neighbor did not recognize Stewart and turned him away when he came to the door trying to give away some of their surplus crops.

Lucie and Desi Arnaz Jr. join the conversation. Lucie says that she sees her mother frequently because they work together. Desi and Merv talk about tennis, a sport they both played avidly. Once again, Desi says that he did not play Little Ricky on “I Love Lucy,” although they were born on the same day.

Lucie recalls her first appearance on her mother's show: as Cynthia on “The Lucy Show.” Merv puts up the now familiar (but colorized as the original was in black and white) publicity photo of Lucy and her children taken during “Lucy is a Soda Jerk” (TLS S1;E23) when Lucie was eleven years old. Although this is her first ‘named’ character in the series, Lucie was an extra in “Lucy is a Referee” (TLS S1;E3) in 1962.

Desi Jr. says that he left “Here's Lucy” during season three in order to do a film, but by the time the shooting was over, his contract had expired and he decided to move on to do other things. Desi Jr. went to college for a short period of time - a week and a half.

Lucie: “I think I've been to the best dramatic school by just being on her [Lucy's] show for six years.”

Gary Morton tells how he and Lucy flew to Warrensburg, Ohio, to see Lucie do a summer stock production of Once Upon a Mattress. He then talks about how proud he is of Desi Jr.'s performance as Marco Polo in the film Marco (1973).The film wasn't actually released until two months after this interview. Lucy hosted a home screening of the film.

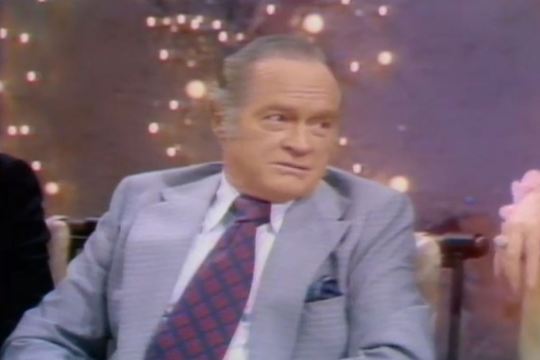

Merv welcomes a surprise guest, Bob Hope. They talk about Bob Hope's house, which was under construction in Palm Springs when it was engulfed by fire, allegedly through arson. Joking, Gary Morton holds out a lit cigarette lighter!

Hope mentions the four films he did with Lucy, even the one they consider the least memorable, Critic's Choice (1963). Lucy calls it a flop. During the filming of The Facts of Life, Lucy was always asking Hope if she had successfully shed the 'Lucy' character. Bob tells the story (which he has told before) of when a Desilu stockholder interrupted the filming with her super 8 camera.

Hope: (about Lucy’s reruns) “She's on so much, you can just flip the dial and see her raise her children.”

Lucy compliments her writers, Bob (Carroll) and Madelyn (Davis).

Hope jokingly says they shouldn't talk about his political affiliations with Washington because he's having enough trouble with his taxes as it is. Lucie says that the President [Richard Nixon] is having trouble with his, too! In late 1973, Nixon was in the headlines for mistakes on his tax returns.

Merv runs the first clip of Mame, despite it not being completely finished in post-production. Lucy says it will be released at Easter. Even Lucy hasn't seen it! [The MPI DVD version of this interview does not include the clip.]

After a commercial break, Merv introduces “Uncle Harry himself” Gale Gordon. Gordon says that he just adores Lucy, even after fifty years in the business. Lucy claims that Gordon is just as good at the table reading as at the final filming. He tells Merv that his mother Gloria Gordon played the landlady on “My Friend Irma” both in the 1949 film and the 1952 television series.

They talk about about Gale Gordon's on-set nickname, 'Old Soggy Crotch', because he was constantly getting wet during episodes of “Here's Lucy.” The show actually bleeps out the nickname because the word ‘crotch’ would not pass the censors! Merv puts up a still from “Lucy Makes A Few Extra Dollars” (HL S4;E6) which depicts Gordon covered with food!

Gary Morton relates that when Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor guest starred on the show, he complimented Gordon on his performance, and assumed that he must have been born in England. Although raised in England, Gordon was actually born in New York City. Lucy says he is now the mayor of Borrego Springs, California.

After a break, Merv introduces the President of the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences Robert Lewin, who presents Ball with a plaque of commemorating her 13 Emmy nominations since 1951. Lewin says the plaque has an 'extension' for her next 13!

Merv shows a clip of Lucy accepting her Emmy for Best Actress. He claims it is 1967, which Lucy questions: “67? I didn't know I won one in 67.” Lucy is correct. The year was 1968.

“The Merv Griffin Show” ~ April 9, 1974

Guests: Lucille Ball, Bea Arthur, Gene Saks, Gary Morton

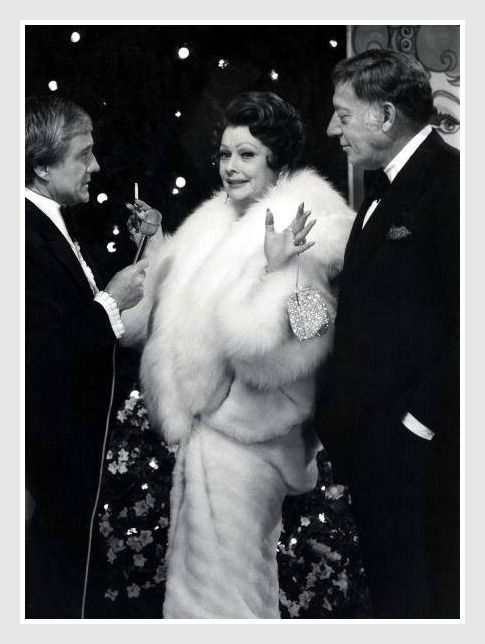

This show was taped on March 24, 1974, on location at the Hollywood premiere of Mame at the Cinerama Dome in Hollywood. Among those interviewed are Lucille Ball and husband Gary Morton; Beatrice Arthur and husband, director Gene Saks.

One of the many fans lining the red carpet for Merv's interview with Lucy was Michael Z. Stern. He later wrote about the experience in his book I Had a Ball: My Friendship With Lucille Ball. Stern recounts that he made a large sign that read “WE LOVE LUCY” which (along with his arm) made it onscreen on “The Merv Griffin Show.”

“The Merv Griffin Show” ~ February 4, 1980

Guests: Lucille Ball, James Brolin, Michele Lee, Natalie Wood

Lucy talks about teaching comedy seminars in college, although the grading confounded her as it was solely a question and answer seminar. Lucy points out someone named Stuart (although he doesn’t appear on camera), one of her former seminar students who is in the studio audience.

Lucy compliments Merv as one of the best 'listeners' of all talk show hosts.

Lucy stresses that she's not a funny person, but credits her daughter and Gary, her husband, with the attribute.

youtube

Merv begs Lucy to do the Lucy Ricardo “Waaaa” cry for him. Lucy is initially reluctant, but she does it for him.

Four days later, “Lucy Moves To NBC” was aired. Lucy's visit is likely to promote that event.

In 2017, Get TV celebrated Lucille Ball's birthday by airing this interview and the 1973 “Merv Griffin Show” interview of Lucy back to back, followed by a rare screening of Lucy's appearance on “Van Dyke & Company.”

“The Merv Griffin Show” ~ June 24, 1982

Guests: Lucille Ball, Ethel Merman, Ginger Rogers

Lucy shares the stage with two powerhouse performers from her past. Merman guest-starred in two back-to-back episodes of “The Lucy Show” in 1964. Ball had done five films with Rogers during the 1930s. She guest-starred as herself on a 1971 episode of “Here's Lucy” (S4;E11).

TRIVIA

Lucille Ball is responsible for Alex Trebek hosting "Jeopardy"! Lucy was a fan of the short-lived game show "High Rollers" hosted by Trebek. When Merv Griffin was looking to reboot "Jeopardy" Lucy suggested he consider hiring Trebek and the rest is history!

#The Merv Griffin Show#Merv Griffin#Lucille Ball#Gary Morton#Lucie Arnaz#Desi Arnaz Jr.#TV#Talk Show#Lucy#Here's Lucy#The Lucy Show#Robert Lewin#Emmy Awards#Michael Z. Stern#Gale Gordon#Bob Hope#Ethel Merman#Ginger Rogers#Mame#alex trebek#Ronald Reagan#Roman Scandals#Jeopardy#Get TV

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Valentine Theatre

410 Adams St.

Toledo, OH 43604

The Valentine Theatre is located in the downtown district of Toledo, Ohio at the corner of Superior and Adams Streets at N. St. Clair Street. The Valentine Theatre opened on December 25 1895, with Joseph Jefferson in ‘Rip Van Winkle.’ It was designed in a Sulivanesque style by architect E.O. Fallis. In 1918 Loew’s took over the lease and it became Loew’s Valentine Theatre. It was converted to an Art Deco/Oriental styled auditorium in a major overhaul of its interior in 1942 by the architectural firm of Rapp and Rapp, and was most likely one of architect George Leslie Rapp’s last projects as he died in 1941.

Another remodeling took place in the 1960’s in which the theatre, at the time run by the Armstrong Theatre chain of Bowling Green, OH (which owned it for 10 years after Loew’s abandoned it), turned it into a 70mm-Cinerama house. A new projection booth was built on the main floor, thus abandoning the upstairs booth, and a custom made Cinerama screen was installed, changing the front of the auditorium by removing the proscenium and stage. This turned the Valentine Theatre into a state-of-the-art cinema. The opening movie was “It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World”.

After a 21-year effort by the Board of Trustees and the community, a $28 million interpretive renovation of the building carried out by architect Charles H. Stark, begun in 1978 and taking 21 years to complete, was unveiled on October 9, 1999, long after the Valentine Theatre had ceased showing movies. The building was added to the National Register of Historic Places on May 19, 1987. On November 23, 2007, a natural gas explosion in the basement caused extensive damage and forced the evacuation of the adjoining Renaissance Senior Apartments. The theater reopened in April 2008 after repairs costing $3.5 million.

Since the Gala re-opening, nearly 1,340,000 people have attended 2,760 international, national and area presentations, weddings and events. The over 125-year-old facility seats 901 and is operated by the Toledo Cultural Arts Center, Inc.. The Toledo Cultural Arts Center, a non profit organization, produces and provides cultural and performing arts experiences for diverse audiences of all ages, to enhance the quality of the cultural and economic life of the City of Toledo, Lucas County, Northwestern Ohio and Southeast Michigan. Groups in residence include the Toledo Symphony Orchestra, Toledo Opera, Toledo Ballet, Toledo Jazz Society, Toledo Jazz Orchestra, Toledo Masterworks Chorale,and Toledo Repertory Theatre.

0 notes

Text

Things to Do

Reel Pizza Cinerama! Located in central Bar Harbor, Reel Pizza is a funky, old fashioned movie theater that serves high quality pizza and fantastic other foods. There are couches in the theater on which you can relax or seats with tables so you can eat your food. I recommend putting the nutritional yeast that they provide on your popcorn because it is absolutely excellent.

A concert at the Village Green. Also located in central BH, various orchestras perform within a lovely little gazebo on the Village Green where you can sit around with your family and hang out while listening to incredible music. There is a wall made of rock that my cousins and I would always climb onto to get the best view (and, consequently, to test how strong our ankles were). It is such a fun thing to do on a warm summer evening. You can also visit Mount Desert Ice Cream while you’re there because you’ll be in the center of BH.

There are so many more fun things to do in MDI, but here are a couple you might like.

0 notes

Text

4 Film Series to Catch in N.Y.C. This Weekend

Our guide to film series and special screenings happening this weekend and in the week ahead. All our movie reviews are at nytimes.com/reviews/movies.

BLACK WOMEN: TRAILBLAZING AFRICAN AMERICAN ACTRESSES AND IMAGES, 1920-2001 at Film Forum (Jan. 17-Feb. 13). In an extraordinarily wide-ranging series, Film Forum examines the portrayal of African-American women throughout film history and celebrates the legacies of the actresses who played them. They range from Evelyn Preer (“Within Our Gates,” on Jan. 28) and Iris Hall (“The Symbol of the Unconquered,” on Jan. 30), who starred in silent films by the pioneering black director Oscar Micheaux, to the blaxploitation icon Pam Grier (“Coffy,” on Saturday, and “Foxy Brown,” on Feb. 1, among others) and beyond. The program’s nominal endpoint, 2001, was the year that “Monster’s Ball” (on Feb. 11 and 13) came out. Its star, Halle Berry, won the best actress Oscar for her role, becoming the first and so far only black woman to receive that honor. 212-727-8110, filmforum.org

INFLUENCING THE ODYSSEY: FILMS THAT INSPIRED STANLEY KUBRICK AND ARTHUR C. CLARKE at the Museum of the Moving Image (Jan. 17-Feb. 2). As a sidebar to a new exhibition on the making of “2001: A Space Odyssey,” the museum is screening movies that had an influence, direct or oblique, on Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 masterpiece. The impact of Max Ophüls’s “The Earrings of Madame De …” (on Friday and Sunday) can perhaps be seen in the elegant movement and tempo of Kubrick’s film. The museum cites “How the West Was Won” (on Saturday and Sunday), which was originally shown in three-strip Cinerama, as being an inspiration for the scale and multipart structure of “2001.” 718-784-0077, movingimage.us

[Read about the events that our other critics have chosen for the week ahead.]

NEW YORK JEWISH FILM FESTIVAL at Film at Lincoln Center (through Jan. 28). The tension between modernity and tradition is always on display at this annual series, whose lineup blends the new and the old. Old in this case stretches back to “Broken Barriers” (on Sunday), a silent feature from 1919 based on the writing of Sholem Aleichem; it’s showing in a new restoration with live accompaniment. The festival will also host 50th-anniversary screenings of “The Garden of the Finzi-Continis” (on Jan. 26 and 27), Vittorio De Sica’s portrait of a Jewish Italian family facing the tightening grip of Fascism. The closing-night feature, “Crescendo,” stars Peter Simonischek (“Toni Erdmann”) as a conductor who tries to convene a youth orchestra that combines Israeli and Palestinian musicians. 212-875-5601, filmlinc.org

ORIGIN STORIES: BERTRAND BONELLO’S FOOTNOTES TO ‘ZOMBI CHILD’ at the Quad Cinema (Jan. 17-23). “Zombi Child,” an odd, elusive new movie from the French director Bonello (“Nocturama”), centers on a group of upper-class schoolgirls, one of whom makes the mistake of exploiting the ostensible magical traditions of a new Haitian classmate. Among other influences, Bonello drew on Jacques Tourneur’s atmospheric B movie “I Walked With a Zombie” (on Monday and Wednesday) and Peter Weir’s Australian classic “Picnic at Hanging Rock” (on Saturday and Tuesday), in which schoolgirls go on an outing and disappear. 212-255-2243, quadcinema.com

from WordPress https://mastcomm.com/4-film-series-to-catch-in-n-y-c-this-weekend/

0 notes