#chickadee pathologic

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

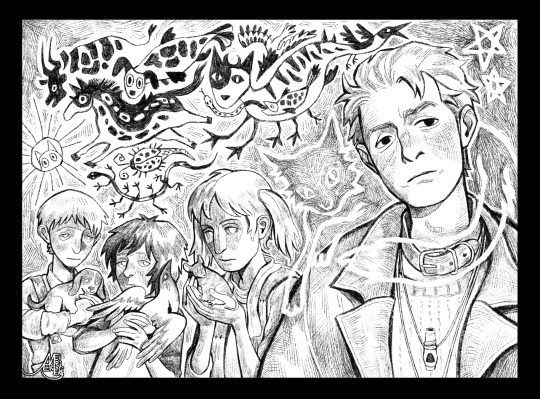

your dogs and my hounds.

#pathologic#pathologic 2#khan kain#notkin pathologic#kaspar kain#dogheads#soul and a halves#teensy pathologic#chickadee pathologic#tot pathologic#there is no murky in these images 🙏🙏🙏#indeed there is no named character beyond khan & notkin the rest are S&H & DHs NPCs#my art#let me be 99 those were supposed to be sketches for etchings but like.#i ain't. doing alldat. peace and love for i will try#this would be my portfolio tag if i had a portfolio [portfolio tag]

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

I Love Pathologic NPCs so much I'm replaying p2 and writing down different names and random lore

Recently a friend and I made our own pathologic OCS, and I made mine have a connection with one of the kin woman NPCs, which in turn made me interested in all the p2 npcs

I'm only on day 5 of my replay, and i'm aware some of this is probably on the wiki, but here are some random bits of lore and info anyway

NAMES:

Some names of kids that are part of the Soul-and-Halves names: Dandy, Catnip, Ace, Ginger, Snout Smokey and Scout

Some names of the Dogheads: Lika, Chara, Maera

Names of other kids: Siskin, Finch, Uta, Swift, Chickadee, Teensy, Wench, Barb, Pup, Goldfinch, Hatchling, Verochka, Basya

Women's names: Kayura, Aigul, Khetey, Dove, Urmaan, Agnia, Starling

Men's names: Shiner, Piecework, Whistler, Kestrel, Ouzel, Crow, Lefty, Stump, Pochard, Pigeon

Dandy is the kid who trades you sharp things at Notkin's hideout. He also trades the infection maps which he and some others make by scouting the infected districts in hopes it will be useful to Artemy. He specifically sits outside the hideout some days to avoid infecting others inside. He thanks you when you come see a sick Notkin.

Catnip gives you bread and milk on day one if you accept it. You can also go back the next day with a piece of bread to thank her for it. Ginger is another girl waiting outside Rubin's house to notify you about Lika's trial.

Ace is the boy waiting outside of Rubin's house on day 1 whose mission is to notify you about the death of their dogs (Alma, Duke and Wokfling). He can also be found a couple days later on The Cape when you start playing The Kids Game. He tells you not to wake up Nina and also invites you to the Nutshell.

Smokey is the boy who gets surrounded by some Dogheads in one of the stairs to heaven. When you ask him if he needs help he says that he's fine, just admiring the view, and very clearly doesn't want adults to intrude in their business and show up in their places. One of the Dogheads waiting for him to come down is called Chara.

Lika is of course the Doghead you see at the start of the game who gives you a tourniquet but later doesn't show up at the town hall to clear your name. And the Doghead trading a schmowder at the Nutshell is Maera.

Finch is random kid with dialogue, so I'm not sure if it's always him saying this, but he asks Artemy if he saw any trains coming, and later mentions how Uta traded all her buttons for just some sugar, which is outrageous.

You then can find Uta later on! specifically during Capella's piano quest. On the second house you go to Uta is playing the piano, and in her conversation she's just shouting at you to go away and threatens to scream if you get closer. Specifically doesn't say "fuck off" because her mom told her not to but she says a couple of "flick off" and "eff off"

Teensy is a little girl who says she still thinks you're good and nice. And Wench is the little girl playing with the bones and scaring boys away. Basya is a little boy who gets surrounded by other kids because his father is a "bad man" (called Whitebeard), and one of those kids is a girl called Barb.

Hatchling is one of the boys staring at Isidor's infected house, and who says Isidor was helpful when Verochka had shingles last year. I haven't actually found anyone called Verochka around the town

There are some kin women like Kayura, who tells you about the Shabnak and says she doesn't believe people kill other people in this town. There's also Aigul and Khetey, who can be found at Aspity's house.

Other women are Dove, whose children are in the tower and won't come back and doesn't personally believe in Shabnaks. Agnia, who is spending her day outside the Judge's door to check which men come asking if killing at night is legal so she can keep herself safe. And there's also Starling who is particularly worried about the people trying to burn off the plague in the streets.

There's of course Piecework, the man Grief asks you to do surgery on. The reason he got injured is because he and Shiner attacked a woman of the Kin. Piecework managed to kill her and the others fought back. They clearly have no medical knowledge.

Kestrel is one of the men trying to stop the mob justice on day one. Stump is the first person you see playing the piano during capella's quest, he's from the Cannery. Pochard is a kin man who says they've lost faith in Artemy and have decided to fight back. And finally Pigeon is complaining on the street about the Kin revolting with no reason.

AND FOR NOW THAT'S ALL I'VE GOT (kinda) if anyone has more small details like these PLEASE add them. can be from pathologic classic too! There's so many good classic npcs like Willow or the Harpist

#pathologic#pathologic 2#pathologic npcs#anyway sorry for ranting i just love all of this sm#one day i'll make a post abt my oc for me and my friend only#shout out to Smokey and Kayura theyre my guys

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

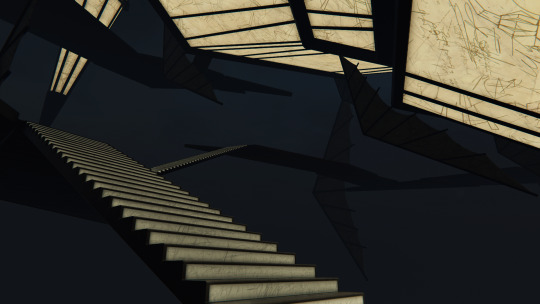

the polyhedron

#pathologic#pathologic 2#the polyhedron#the bridge square#teensy npc#tot npc#chickadee npc#the town#townsfolk

745 notes

·

View notes

Quote

One and two and one and two, Steppe has gotten into you. Who breathes the air in the fall, Dies before he sees it all.

Chickadee, Pathologic 2

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Stamatin’s have ADHD, the meta post.

As someone with ADHD the Stamatin twins really stood out to me as having ADHD so I’ve decided to compile my reasons why I think they do.

This will be put under a cut since this is probably going to get long. There are some spoilers for both games but no end game stuff and only things related to the two and the characters closest to them.

As I get further in the games I may add on to this. So check the notes.

Also I will be posting a headcanon post for stuff that isn’t as supported by canon which shall be linked here once it’s up!

The Twins (As a unit)

While they are fictional characters so real life information may not apply I felt it was worth it to mention that twins are more likely to have ADHD vs non-twins and it’s more likely to have ADHD if your twin also has it.

They both have the habit of ending questions by repeating part of the question. “Do you understand? Do you?! ” & “Do you get it? Do you?” which as mentioned later on people with ADHD can be misunderstood frequently which could lead to double checking if they are being understood.

They both tend to hyperfocus on the polyhedron and it’s well being and status. It also could be a comfort item for the both of them.

Both are described as renaissance men, which is an archetype that frequently show signs of having ADHD. Here’s a post about Leonardo da Vinci possibly having ADHD.

ADHD people frequently are known for their unique and vast creativity, something neither Stamatin lacks in.

They are both very reliant on the other and won’t do major actions without knowing if the other will approve which could be a sign of rejection sensitive dysphoria.

Peter

I would say that he suffers from predominantly inattentive ADHD. He does certainly have other mental things going on (Depression, alcoholism, likely paranoia, and likely schizophrenia) which can make pointing out the things unique to ADHD more difficult but I will try.

From the design documents for P1: “-The walls are covered in spots of wine, paint and blood, traces of sleepless nights and creative search.” People with ADHD tend towards having trouble sleeping or having a sleep cycle that differs from a neurotypical person. Also the quote (at least to me) makes it sound like he’s trying to bounce around different ideas hoping one will stick which is something common with ADHD people.

From the design documents for P2: “-At times, he seems to lose interest in what he’s talking about before finishing his sentence as if he’s given up all hope of being understood.” People with ADHD tend to have a train of thought that goes fast and in ways that others may not understand leading to feeling misunderstood or assuming that they will be.

In Pathologic 2 after Grace has come under his care Artemy can speak to him about an idea he’s had and mention some fair and reasonable ideas he could have had, which he completely ignores as he tells Artemy about his pit idea. This could be an incident of hyperfocusing on a project/idea for a project.

One reason for Peter drinking (besides from his depression and alcoholism) could be to help quiet down his head. Sometimes for someone with ADHD their thoughts can get so overwhelming or go so fast even they can’t keep up. One quote from him is “Bad twyrine makes your head feel like lead. Good.”

There is a connection between ADHD and addiction along with having addictive tendencies.

Part of his calmer, more thoughtful persona (as opposed to his brother) could be that he needs more time to process things and come up with a response.

His coat could act as a pressure stim (while stimming is more classically associated with autism it also shows up with ADHD)

This one may be a stretch but the developers decided to out of the animations they had in the beta the Chickadee ones fit him the best. The behavior in the animations could be seen as stimming.

Andrey

I would say he suffers from predominantly hyperactive-impulsive ADHD. It is easier to point out things for him as he deals with better known symptoms of ADHD and has less co-morbid conditions than Peter, although there are less bullet points for the same reason.

He can experience emotional dysregulation, see day 5 of the changeling route where he yells at her due to her request for Peter to join the humbles. It would be understandable to be upset but he takes it way too far

There is a lot of evidence of his recklessness and lack of forethought but one very good example is on day 7 of the Bachelor’s route where upon being told that some “her” had been taken he immediately assumed it was Eva and then ran off to try to rescue her without even stopping to think, only realizing what had actually happened after the action was over.

From the P1 design document: “Wild, hedonistic, energetic. Fearless, a glutton for pleasure, fierce and jovial.” Those are all traits that can be an extension of the inability to regulate responses and dopamine which can lead a ADHD person to seek out more thrilling and intense experiences (along with bounce from one hyperfocus to another).

Also from the P1 design document: “-He works in chaotic and unstable surges.” That is literally one of the most well known and easy to see symptoms of ADHD there are and it’s mentioned right in the design document.

#pathologic#peter stamatin#andrey stamatin#pathologic meta#pathologic 2#adhd headcanon#my meta#my writing#.txt

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Snow hares show changes in their behavior and brain chemistry that appear similar to PTSD in humans (Credit: Jim Cumming/Getty Images)

Do Animals Suffer From Post-Traumatic Stress?

Commonly thought of as a human response to danger, injury and loss, there is growing evidence that many animals show lasting changes in their behaviour after traumatic events. Can they point to an evolutionary source for PTSD?

— Sharon Levy | BBC News

Every few years, snowshoe hare numbers in the Canadian Yukon climb to a peak. As hare populations increase, so do those of their predators, lynx and coyotes. Then the hare population plummets and predators start to die off. The cycle is a famous phenomenon among ecologists and has been studied since the 1920s.

In recent years, though, researchers have come to a startling conclusion – hare numbers fall from their peak not just because predators eat too many of them. There's another factor: chronic stress from living surrounded by killers causes mother hares to eat less food and bear fewer babies. The trauma of living through repeated predator chases triggers lasting changes in brain chemistry that parallel those seen in the brains of traumatised people. Those changes keep the hares from reproducing at normal levels, even after their predators have died off.

And it's not just snowshoe hares, as behavioural ecologists Liana Zanette and Michael Clinchy have shown. Zanette and Clinchy, both at the University of Western Ontario, are a married couple who majored in psychology as undergraduates. Today, they study what they call the ecology of fear, which combines the psychology of trauma with the behavioural ecology of fear in wild animals. They've found that fear of predators can cause other wild mammals and songbirds to bear and raise fewer young. The offspring of frightened voles and song sparrows, like those of stressed snowshoe hares, are less likely to survive to adulthood and succeed in reproducing.

These findings add to a growing body of evidence showing that fearful experiences can have long-lasting effects on wildlife and suggesting that post-traumatic stress disorder, with its intrusive flashback memories, hypervigilance and anxiety, is part of an ancient, evolved response to danger. The work is part of a wider scientific debate over the nature of PTSD and whether it is an evolved response shared among mammals, birds and other creatures, or is unique to humans.

Studies of the ecology of fear started in the 1990s. Before then, scientists assumed that the impact of a predator on an individual prey animal was either deadly or fleeting. If a hare survived a coyote attack, or a zebra escaped the claws of a lion, it would move on and live its life as before.

But research shows that fear can alter the long-term behaviour and physiology of wild animals, from fish to elephants. "Fear is a response all animals mount to avoid being killed by predators," says Zanette. "It's enormously beneficial, because it keeps you alive to breed another day. But it does carry costs."

The reasons to fear are clear. Recent studies have found that up to 32% of adult female giraffes in parts of the Serengeti carry scars from lion attacks, 25% of harbour porpoises in the southern North Sea have claw and bite marks from grey seals and three quarters of manta rays in some African waters bear multiple bite wounds from sharks. These survivors may carry memories of terror along with their physical scars.

Rudy Boonstra, a population ecologist at the University of Toronto, has studied the impacts of extreme stress on the snowshoe hares and other small mammals of the Canadian Yukon since the 1970s. He was inspired by his own family history: Boonstra was born in the Netherlands, where his mother — like many of the Dutch — experienced severe stress during World War Two. "That likely affected her children," he says. "That sense of stress being a relevant factor in our biology was always in the back of my mind."

Boonstra knew that during the decline phase of the snowshoe hare cycle, the great majority of hares are killed by predators. But there turned out to be more to the story. When Boonstra's student, Michael Sheriff, tested faeces of live-caught hares during the rise and fall phases of the population cycle, he found that levels of the stress hormone cortisol in mother hares fluctuated with predator density, peaking when predators were most numerous.

Those highly-stressed mothers, the researchers found, bore fewer, smaller babies. And heightened stress hormone levels were also passed from mothers to daughters, slowing the rates of hare reproduction even after predators had died off and abundant vegetation was available for hares to eat. This explains why the hare population remains low for three to five years after predators have all but vanished from Boonstra's study site.

Animals stressed by many predators spend more time hiding and less time feeding, so they produce fewer young — but that may allow more adult hares to survive to rebuild the population

Early pioneers of stress physiology focused on human problems and viewed such stress responses as pathological, but Boonstra has come to disagree. He sees the response of snowshoe hares as an adaptation that allows the animals to make the best of a bad situation. Animals stressed by many predators spend more time hiding and less time feeding, so they produce fewer young — but that may allow more adult hares to survive to rebuild the population when the cycle starts again.

Fearful experience such as being hunted by predators or humans may leave a long-lasting effects on animals. (Credit: Arctic Images/Getty Images)

Some of the most dramatic impacts of wildlife trauma have been observed in African elephants. Their populations have declined drastically due to poaching, legal culling and habitat loss. Undisturbed elephants live in extended family groups ruled by matriarchs, with males departing when they reach puberty. Today, many surviving elephants have witnessed their mothers and aunts slaughtered before their eyes. A combination of early trauma and the lack of stable families that would ordinarily be anchored by elder elephants has resulted in orphaned elephants running amok as they grow into adolescence.

"There are interesting parallels between what we see in humans and elephants," says Graeme Shannon, a behavioural ecologist at Bangor University in Wales who studies the African elephant. Trauma in childhood and the lack of a stable family are major risk factors for PTSD in people. And among elephants who've experienced trauma, Shannon notes, "we're seeing a radical change in their development and their behaviour as they mature". Elephants can remain on high alert years after a terrifying experience, he says, and react with heightened aggression.

Shannon experienced this first-hand when he and his colleagues were following a herd of elephants in South Africa's Pongola Game Reserve. The researchers kept their car at a respectful distance. But when they rounded a curve, Buga, the herd’s matriarch, stood blocking the road. The driver immediately turned off the engine, which generally causes elephants to move on peaceably. Instead, Buga charged the car. "Next thing we knew, the car was upside down and we were running," remembers Shannon. Buga's extreme reaction, he suspects, was linked to trauma she experienced when she was captured and relocated six years earlier.

Human responses to danger, injury and loss are likely part of this same evolved set of responses. A vast body of evidence shows that the brains of mice, men — in fact, all mammals and birds, fish, even some invertebrates — share a common basic structure, and common responses to terror or joy. The brain circuitry that signals fear and holds memories of terrifying events lies in the amygdala, a structure that evolved long before hominids with bulging forebrains came into being.

Many adult giraffes bear the scars from lions, but these encounters may leave non-physical marks too (Credit: BiosPhoto/Alamy)

Most modern people with PTSD have been traumatised in combat or during a criminal attack or a car crash. But the intrusive memories of trauma, the constant state of alarm that can wear down the body's defences and lead to physical illness — these arise from the same ancient brain circuits that keep the snowshoe hare on the lookout for hungry lynx, or the giraffe alert for lions.

The amygdala creates emotional memories, and has an important connection to the hippocampus, which forms conscious memories of everyday events and stores them in different areas of the brain. People or other animals with damaged amygdalae can't remember the feeling of fear, and so fail to avoid danger.

Brain imaging studies have shown that people with PTSD have less volume in their hippocampus, a sign that neurogenesis — the growth of new neurons — is impaired. Neurogenesis is essential to the process of forgetting, or putting memories into perspective. When this process is inhibited, the memory of trauma becomes engraved in the mind. This is why people with PTSD are haunted by vivid memories of an ordeal long after they've reached safety.

In a similar manner, fear of predators suppresses neurogenesis in lab rats. And Zanette and Clinchy are demonstrating that the same pattern holds in wild creatures living in their native habitats.

The scientists began by broadcasting the calls of hawks in a forest and found that nesting female song sparrows that heard the calls produced 40% fewer live offspring than those that did not. In later experiments, they showed that brown-headed cowbirds and black-capped chickadees that heard predator calls showed enduring neurochemical changes due to fear a full week later. The cowbirds had lowered levels of doublecortin, a marker for the birth of new neurons, in both the amygdala and hippocampus.

Repeated chases by predators can alter snowshoe hare behaviour and lead them to have fewer young (Credit: Tom Brakefield/Getty Images)

The same pattern has been shown in wild mice and in fish living with high levels of predator threat. These neurochemical signals parallel those seen in rodent models of PTSD that researchers have long used to understand the syndrome in humans.

Despite the mounting evidence that a wide range of animals experience long-term impacts of extreme stress, many psychologists still see PTSD as a uniquely human problem. "PTSD is defined in terms of human responses," says David Diamond, a neurobiologist at the University of South Florida. "There is no biological measure — you can't get a blood test that says someone has PTSD. This is a psychological disease, and that's why I call it a human disorder. Because a rat can't tell you how it feels."

Some researchers now disagree with this human-centric view of PTSD, however. "A lot of things are shared between humans and other mammals," says Sarah Mathew, an evolutionary anthropologist at Arizona State University. This includes learning about and responding to danger, and avoiding situations that present life-threatening risks. Mathew believes that PTSD has deep evolutionary roots, and that some of its symptoms arise from adaptations — like a heightened state of alert — that allow individuals of many species, including our own, to manage danger.

This evolutionary perspective is beginning to change minds. Clinchy and Zanette have organized conferences on the ecology of fear and PTSD that bring together ecologists, psychiatrists and psychologists. "The psychiatrists and psychologists were talking about PTSD as maladaptive," recalls Clinchy. "We were arguing that this is an adaptive behaviour, to show these extreme reactions in this particular context, because that increases your survival."

Diamond came to agree. The brain of someone with PTSD, he says, "is not a damaged or dysfunctional brain, but an overprotective brain".

"You're talking about someone that has survived an attack on his or her life," he adds. "So the hypervigilance, the inability to sleep, the persistent nightmares that cause the person to relive the trauma — this is part of an adaptive response gone awry."

"There's a stigma involved in PTSD, frequently," says Zanette, "so people don't seek treatment. But if patients can understand that their symptoms are perfectly normal, that there is an evolutionary function for their symptoms, this might relieve some of the stigma around it so that people might go and seek treatment."

* This article originally appeared in Knowable Magazine, and is republished under a Creative Commons licence.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

“one of our lads, patches, came down with somethin' nasty.” (day 3); the soul-and-a-halves’ fortress, the warehouse district

#pathologic#pathologic 2#swift npc#teensy npc#tot npc#chickadee npc#finch npc#the soul and a halves#soul and a halves' fortress#the warehouse district#townsfolk#clara#notkin#character#the town

60 notes

·

View notes

Photo

funeral for the eighth, day 2; the gut

58 notes

·

View notes

Photo

shrew and sleepyhead (chickadee and finch npcs); dialog screen

#pathologic#pathologic 2#the marble nest#shrew#sleepyhead#townsfolk#dialog screen#chickadee npc#finch npc

53 notes

·

View notes

Photo

day 12, introduction

#pathologic#pathologic 2#introduction#day 12#the town#infected#infected district#chickadee npc#doghead npc#pochard npc#odongh#measly#thrush#the powers that be#character

47 notes

·

View notes

Photo

blood, nerve, and skin, day 3; the bridge square

#pathologic#pathologic 2#goose npc#chickadee npc#pochard npc#the town#townsfolk#the cathedral#the bridge square

28 notes

·

View notes