#chen lingyu

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

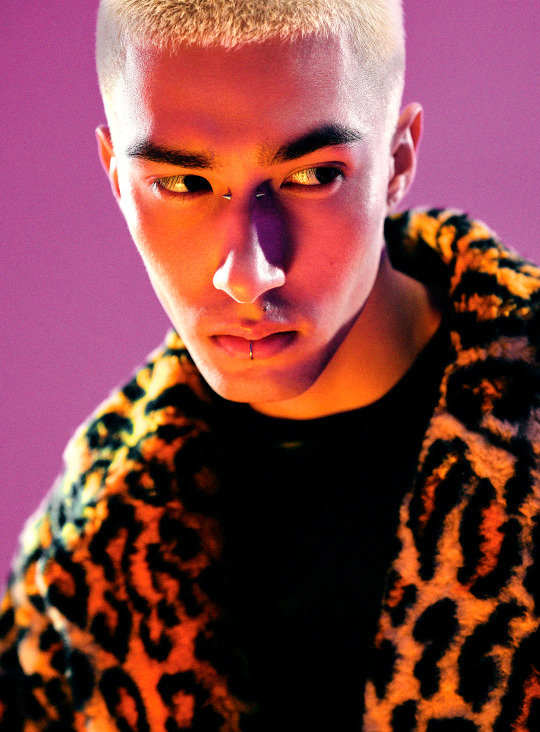

hashizume mika by chen lingyu for men's uno china jan '24 makeup & hair by zhao shu

41 notes

·

View notes

Note

hello ! Sorry to bother But I was wondering if u had any 90's Hong Kong movies that you could recommend me ? I'm researching them for school and I usually get the most interesting and gutwrenching sinophone movie recs from your blog so I thought I should ask if u had any ! Thank u ❣️

Hey you 🥰 this is probably waaaaaay to late to be of any help with your research (sorry!) but I'll answer anyway just in case <3 (also, it got. a bit long 😳 so sorry about that lmao)

I'll start off by addressing the elephant in the room, a.k.a. Wong Kar-wai: the director you really can't avoid mentioning when talking about 90s and 00s Hong Kong cinema, and for good reason. I won't mention all his films here, but his best known are probably In the Mood for Love (which is regularly hailed as one of the greatest films ever made, which. yes); Happy Together (a staple of queer cinema starring Tony Leung and Leslie Cheung caught up in a fever-like, destructive love affair in Buenos Aires); Chungking Express (another classic beloved by many, many people); Fallen Angels (a stylish and chaotically seductive about eccentric figures inhabiting Hong Kong's nightlife).

Another director from this period who I think is worth highlighting is Stanley Kwan. He's probably best known for Rouge, which is from 1987 but which I’m including because it’s a classic; it stars the wonderful Leslie Cheung and Anita Mui as the principals in a doomed, decades-spanning love affair, featuring sumptuous visuals, ghosts, and time-slippages between the 1930s and 1980s. His other most notable work is probably Center Stage (1991); it's a very meta biopic of the 1930s actress Ruan Lingyu, who is portrayed by Maggie Cheung, and Kwan uses the film to draw parallels between the two actresses living decades apart. And I'll also mention his Lan Yu (2001), a gay love story set against the backdrop of Tiananmen Square and its aftermath (it's probably weird to admit that this is one of my comfort films but shrugs).

Comrades: Almost a Love Story (1996) is an absolute favourite of mine, about immigrant identity, missed chances and lives you could have led, human connection under capitalism, and the love story between two people whose paths keep crossing despite everything--all of which is topped off with fantastic performances from Maggie Cheung and Leon Lai.

Farewell My Concubine (1993) was a Hong Kong-mainland co-production and is probably one of the best known films on this list, starring the fantastic Leslie Cheung in one of the defining performances of his career (tbh it would be worth watching for his performance alone). Coming in at just under 3 hours, it's a cinematic epic in pretty much every sense of the word.

Speaking of Leslie Cheung: Viva Erotica (1996), in which he plays an arthouse director whose Serious Films keep flopping, so he has to turn his next film into an erotic movie financed by a triad boss. It’s funny and big-hearted and has some unexpectedly interesting things to say about filmmaking and cinema as both an industry and as an artform.

Ann Hui is one of the few female big-name Hong Kong directors of the 90s; I'd recommend her 1990 film Song of the Exile--a film about generational conflict, immigration, cultural alienation and family ties, which takes place across the UK, Hong Kong, and Japan, and stars Maggie Cheung in the lead role. (Another prominent woman director from the period whom I've been meaning to watch since forever Mabel Cheung--really looking forward to finally seeing something of hers soon.)

Takeshi Kaneshiro and Kelly Chen had quite a few collaborations which are rather nice. Their Anna Magdalena (1998) is a quirky but poignant love-triangle story that inexplicably turns into a delightful steampunk romp. Lost and Found (1996) is another quirky-but-poignant love story, albeit a little more sedate.

For action films, there's the legendary John Woo, whose films are pretty quintessential action flicks--Hard Boiled is a pretty good example of his filmography. There's also The Heroic Trio and Executioners (both 1993): an action duology starring Michelle Yeoh, Maggie Cheung and Anita Mui as a trio of ass-kicking vigilante superheroes. It's sooooo much fun, peak cinema, marvel could never, etc. etc. I'm also going to mention Infernal Affairs (2002), starring Tony Leung Chiu-wai and Andy Lau, because it's one of my favourite action thriller films of all time.

Wuxia: a lot of the most well-known titles of the genre are from the first decades of the 2000s, and because of their scope they tend to be international productions, but often had veteran Hong Kong actors in main roles (for example, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000), Hero (2002), House of Flying Daggers (2004)--all of which I would recommend, btw). But there were also quite a few wuxia films that came out of Hong Kong in the 90s, including New Dragon Gate Inn (a fun 1992 remake of the 1960s wuxia classic, starring Brigitte Lin, Tony Leung Ka-fai, Maggie Cheung); The Green Snake (1993), a retelling of the traditional Legend of the White Snake that doubles as an interesting deconstruction of lots of the main tropes of the wuxia genre; Wong Kar-wai's 1994 Ashes of Time, which has an insanely star-studded cast and is pretty much what you'd expect a wkw wuxia film to be like.

.......aaaaaaand i'm going to stop there, because this is already a Lot😅 but hopefully there's something of use in here--if not for your research, then at least recommending a new film to watch <3

#mandatory 'sorry for the late reply i was on hiatus'#or well semi-hiatus#although i think everyone knows by now how useless i am at remembering to check my inbox#😅#bbscclmate#ask response#hong kong movie#i also should add the necessary disclaimer that i am by no means an expert and there are definitely lots more films worth mentioning that..#.....i simply haven't seen yet#i've only mentioned ones that i've watched but they're just a tiny fraction of everything on offer!!!!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chen Xiao, Mao Xiaotong reunite in wuxia drama The Ingenious One

#ChenXiao, #MaoXiaotong reunite in wuxia drama #TheIngeniousOne

Good news for Guofu shippers – Chen Xiao and Mao Xiaotong, who played Yang Guo and Guo Fu in Romance of the Condor Heroes 2013, will be playing the leads in iQiyi’s wuxia drama The Ingenious One 云襄传 (also the drama at the centre of the script re-edit controversy in showbiz drama We Are All Alone). (more…)

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

vimeo

Center Stage - Stanley Kwan (1991)

trailer

Watch on the Criterion Channel

#center stage#stanley kwan#maggie cheung#1991#1990s#china#hong kong#ruan lingyu#carina lau#tony leung ka fai#drama#golden way films#johnny chen

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Here’s a masterlist of over 420+ Chinese faceclaims with their age and ethnicity noted if there was a reliable source! If you have any suggestions or know any missing information feel free to send us an ask. Please give this post a like or reblog if you found it useful.

FEMALE:

Vera Wang (1949) — Fashion Designer

Liu Xiao Qing (1955) — Actor

Deng Jie (1957) — Actor

Velina Hasu Houston (1957) African-American, Pikuni Blackfoot, Japanese, Chinese, Native Hawaiian, Cuban, Argentinian, Brazilian, Armenian, Greek, German, English — Playwright and Author.

Jennifer Tilly (1958) ½ Chinese ½ Finnish, Irish, First Nations — Actor

Liu Xue Hua (1959) — Actor

Teresa Mo (1959) Hongkonger — Actor

Ding Jiali (1959) — Actor

Leanne Liu (1959) — Actor

Candice Yu (1959) Hongkonger — Actor

Kiki Sheung (1959) Hongkonger — Actor

Candice Yu (1959) Hongkonger — Actor and Singer

Ni Ping (1959) — Actor and TV Host.

Emily Chu (1960) Hongkonger — Actor

Lü Liping (1960) — Actor

Olivia Cheng (1960) Hongkonger — Actor

Kara Hui (1960) Manchu — Actor

Idy Chan (1960) Hongkonger — Actor

Meg Tilly (1960) ½ Chinese ½ Finnish, Irish, First Nations — Actor

Rae Dawn Chong (1961) ½ Chinese, Scots-Irish ½ Black Canadian, Cherokee — Actor

Joan Chen (1961) — Actor

Song Dandan (1961) — Actor

Rae Dawn Chong (1961) Chinese, Scots-Irish / African-American — Actor

Joan Chen (1961) — Actor, Director, Screenwriter, and Producer

Mao Weitao (1962) — Actor and Singer

Hong Yue (1962) — Actor

Rosamund Kwan (1962) Manchu / Chinese — Actor

Kingdom Yuen (1962) Hongkonger — Actor

Jaime Chik (1962) Hongkonger — Actor

Michelle Yeoh (1962) — Actor

Cecilia Yip (1963) Hongkonger — Actor

Ming Na Wen (1963) — Actor

Carrie Ng (1963) Hongkonger — Actor

Charlene Tse (1963) Hongkonger — Actor

Li Lingyu (1963) — Actor and Singer

He Saifei (1963) — Actor

Ming-Na Wen (1963) — Actor

Phoebe Cates (1963) ¾ Ashkenazi Jewish ¼ Chinese — Actor and Model

Maggie Cheung (1964) Hongkonger — Actor

Chen Jin (1964) — Actor

Esther Kwan (1964) Hongkonger — Actor

Fu Yiwei (1964) — Actor

Moon Lee (1964) Hongkonger — Actor

Carina Lau (1964) Hongkonger — Actor and Singer

Gong Li (1965) — Actor

Yu Hui (1965) — Actor

Maggie Shiu (1965) — Actor

Amy Yip (1965) Hongkonger — Actor

Kathy Chow (1966) Machu — Actor

Irene Wan (1966) Hongkonger — Actor

May Mei-Mei Lo (1966) Hongkonger — Actor

Sheren Tang (1966) Hongkonger — Actor

Bai Ling (1966) — Actor

Cutie Mui (1966) Hongkonger — Actor and TV Host

Loletta Lee (1966) Hongkonger — Actor

Vivian Wu (1966) — Actor

Monica Chan (1966) Hongkonger — Actor and Model

Ellen Chan (1966) Hongkonger — Actor

Shirley Kwan (1966) Hongkonger — Singer

Xu Fan (1967) — Actor

Celine Ma (1967) Hongkonger — Actor

Li Shengsu (1967) — Actor and Singer

Jin Xing (1967) — Dancer and Actress — Trans

Vivian Chow (1967) Hongkonger — Actor and Singer

Amy Kwok (1967) Hongkonger — Actor

Elvina Kong (1967) Hongkonger — Actor and Presenter

Florence Kwok (1968) Hongkonger — Actor

Chen Hong (1968) — Actor

Chingmy Yau (1968) Hongkonger — Actor

Ju Xue (1968) Chinese — Actor

Kelly Hu (1968) English, Chinese, Hawaiian — Actor

Louisa So (1968) Hongkonger — Actor

Yvonne Yung (1968) Hongkonger — Actor

Lucy Liu (1968) — Actor

Canny Leung (1968) Hongkonger — Singer and Author

Boh Runga (1969) ½ Chinese ½ Māori — Singer

Kenix Kwok (1969) Hongkonger — Actor

Naomi Campbell (1970) Jamaican (African, ¼ Chinese, possibly other) — Actor and Model

Maxine Bahns (1971) ½ German ½ Chinese, Portuguese-Brazilian — Actor and Singer

Yuen Wing Yi (1971) — Actor

Li Bingbing (1973) — Actor

Sharin Foo (1973) 2/4 Danish,¼ Chinese — Musician

Natassia Malthe (1974) ½ Norwegian, ½ Chinese-Malaysian — Actor and Model

China Chow (1974) Chinese, Japanese, German — Model and Actor

Zhou Xun (1974) — Actor

Coco Lee (1975) ½ Hongkonger ½ Chinese — Singer, Dancer, and Actor

He Meitian (1975) — Actor

Katja Schuurman (1975) Chinese, Dutch, Surinamese — Actor, Singer and TV Personality.

Sheh Charmaine (1975) Hongkonger — Actor

KT Tunstall (1975) ½ Chinese, Scottish ½ Irish — Singer

Bic Runga (1976) ½ Chinese ½ Māori — Singer

Zhao Wei (1976) — Actor

Li Xiao Ran (1976) — Actor

Chen Si Si (1976) — Actor

Yang Ming Na (1976) — Actor

Lu Min Tao (1978) — Actor

Gong Beibi (1978) — Actor

Nicole Lyn (1978) Afro-Jamaican, Chinese, Anglo — Actor

Liu Tao (1978) — Actor

Michaela Conlin (1978) ½ Chinese, ½ Irish — Actor

Zhang Ziyi (1979) — Actor

Bérénice Marlohe (1979) ½ Chinese, Cambodian ½ French — Actor

Chen Hao (1979) — Actor, Singer, and Model

Elaine Tan (1979) — Actor

Chen Yao (1979) — Actor

Gao Yuan Yuan (1979) — Actor

Zhao Yuan Yuan (1979) — Actor

Wu Hang Yee / Wu Myolie (1979) Hongkonger — Actor

Yeung Yi / Tavia Yeung (1979) Hongkonger — Actor

Cecilia Cheung (1980) ¼ White British, ¾ Hongkonger — Actor

Lena Hall (1980) Filipino, Spanish, possibly Chinese, Swedish, English, possibly other — Actor and Singer

Chen Lili (1980) — Singer, Model and Actor — Trans

Myl��ne Jampanoï (1980) ½ Chinese ½ Breton — Actor

Olivia Munn (1980) ½ Chinese, ½ English, Scottish, German — Model and Actor

Jolin Tsai (1980) 75% Han Chinese 25% Aboriginal Taiwanese (Papora) — Singer

Chung Ka Lai/Gillian Chung (1981) Hongkonger — Actor

Fan Bingbing (1981) — Actor

Liza Lapira (1981) Filipino, Spanish, Chinese — Actor

Zhang Meng/Zhang Alina (1988) — Actor

Yang Rong (1981) — Actor

Zhang Xin Yi (1981) — Actor

Francine Prieto (1982) ½ Filipino, Chinese ½ Norwegian — Actress, Singer, and Model

Gemma Chan (1982) — Actor

Jia Xiao Chen/Jia JJ (1982) — Actor

Lee Kai Sum (1982) Hongkonger — Actor

Li Xiao Lu (1982) — Actor

Kristin Kreuk (1982) ½ Chinese, with some Scottish and African, ½ Dutch — Actor

Sun Li/Sun Betty (1982) — Actor

Constance Wu (1982) Han Chinese — Actor

Yan Yi Dan (1982) — Actor

Wang Ou/Angel Wang (1982) — Actor

Christina Chong (1983) ½ Chinese ½ English — Actor

Lan Xi (1983) — Actor

Tang Yan/Tiffany Tang (1983) — Actor

Teresa Castillo (1983) Mexican, Chinese, Spanish — Actor

Huang Lu (1983) — Actor

Alexa Chung (1983) 37.5% Chinese 62.5% English and Scottish — Fashion Designer, TV presenter, Model and Writer.

Yasmin Lee (1983) Thai, Cambodian and Chinese — Model — Trans

Jiang Xin (1983) — Actor

Chung Ka Yan/Linda Chung (1984) Hongkonger — Actor and Singer

Bai Xui/Bai Fay (1984) — Actor

Wu You (1984) — Actor

Wang Li Kun (1985) — Actor

Li Cheng Yuan (1984) — Actor

Xhang Li (1984) — Actor

Hai Lu (1984) — Actor

Jane Zhang (1984) — Singer

Lu Jia Rong/Lu Kelsey (1984) — Actor

Tami Chynn (1984) Chinese, Cherokee, Afro-Jamaican, English — Singer and Dancer

Qi Wei (1984) — Actor and Singer

Du Ruo Xi (1985) — Actor

Heart Evangelista (1985) Filipino (Tagalog), Chinese, Spanish (Asturian) — Actor and Model.

Juliana Harkavy (1985) ½ Ashkenazi Jewish ½ Dominican Republic, African, Chinese — Actor

Celina Jade (1985) ½ Chinese ½ English, Irish, German, French — Actor, Singer, Model and Martial Artist

Tong Yi La/Yi Yi (1989) — Actor

Angel Locsin (1985) Filipino (including Hiligaynon), Chinese, Spanish (Galician) — Actor

Jessica Lu (1985) ½ Chinese, Japanese ½ Chinese — Actor

Jing Lusi (1985) — Actor

Joséphine Jobert (1985) Sephardi Jewish / Martiniquais, Spanish, possibly Chinese — Actor

Kirby Ann Basken (1985) ½ Norwegian ½ Filipino (Tagalog), Chinese — Model

Li Sheng (1985) — Actor

Cindy Sun (1985) — Actor

Suzuki Emi (1985) — Model and Actor

Tong Yao (1985) — Actor

Tessanne Chin (1985) ½ Chinese, Cherokee Native American ½ Jewish, Afro-Jamaican, likely other — Singer

Tao Xin Ran (1986) — Actor

Michelle Bai (1986) — Actor

Gan Ting Ting (1986) — Actor

Jia Qing (1986) — Actor

Maggie Jiang (1986) — Actor

Lin Peng (1986) — Actor

Yang Mi (1986) — Actor

Mao Lin Lin/Nikia Mao (1986) — Actor

Liu Shishi (1987) — Actor

Victoria Song (1987) — Actor and Idol.

Sun Yao Qi (1987) — Actor

Wang Olivia (1987) — Actor

Yuan Shan Shan/Mabel Yuan (1987) — Actor

Zhang Xin Yu/Zhang Viann (1987) — Actor

Cao Lu (1987) — Actor and Singer

Ellen Adarna (1988) 68.75% Filipino (Cebuano), 25% Chinese, 6.25% unknown — Actress and Model

Jiao Jun Yan (1987) — Actor

Li Fei Er (1987) — Actor

Liu Yifei (1987) — Actor

Li Chun/Li Frida (1988) — Actor

Amanda Du-Pont (1988) Portuguese, Chinese, French and Swazi — Actor

Ma Si Chun/Sandra Ma (1988) — Actor

Mao Xiaotong (1988) — Actor

Wang Feifei (1987) — Actor and Idol

Zhao Li Ying (1987) — Actor

Crystal Yu (1988) Hongkonger — Actor

Feng Jing (1988) — Actor

Adesuwa Aighewi (1988) Nigerian / Chinese — Model

Han Qing Zi/Kan Adi (1988) — Actor

Hou Meng Yao (1988) — Actor

Jing Tian (1988) — Actor and Singer

Liu Wen (1988) — Model

Li Yi Xiao (1988) — Actor

Li Xi Rui/Sierra Li (1989) — Actor

Lou Yi Xiao (1988) — Actor

Ni Ni (1988) — Actor

Sarah Geronimo (1988) Filipino, Chinese — Singer and Actor

Wang Xiao Chen (1988) — Actor

Ying Liu/Ying Er (1988) — Actor

Zhang Meng/Zhang Lemon (1988) — Actor

Meng Jia (1989) — Actor and Singer

Helena Chan (1989) Swedish, Chinese — TV Presenter and Model

Anna Akana (1989) Japanese, Native Hawaiian, possibly English, Irish, German, French, Chinese / Filipino, possibly Spanish — Actor, Author and Comedian

Ayesha Curry (1989) ½ Polish, African-American ½ Chinese, African-Jamaican — Actor

Sun Fei Fei (1989) — Model

Xi Mengyao/Ming Xi (1989) — Model

Angelababy (1989) ¼ German, ¼ Hongkonger, ½ Shanghainese — Actor

An Yue Xi (1989) — Actor

Sammi Maria (1989) English, Afro Guyanese, Chinese — YouTuber

He Sui (1989) — Model and Actor

Jiang Kai Tong (1989) — Actor

Jiang Meng Jie (1989) — Actor

Mi Lu/Mi Viola (1989) — Actor

Miller/Vespa Miller (1989) — Actor

Shen Meng Chen (1989) — Actor

Adrianne Ho (1989) Chinese, French — Model

Sui He (1989) — Actor and Model.

Tang Yi Xin/Tang Tina (1989) — Actor

Xiao Wen Ju (1989) — Model

Awkwafina (1989) Chinese / Korean — Rapper and Actor

Zhang Han Yun/Zhang Baby (1989) — Actor

Zhang Tian Ai/Crystal Zhang (1990) — Actor

Li Yitong (1990) — Actor

Elizabeth Tan (1990) — Actor

Gong Mi (1990) — Actor

Jin Chen (1990) — Actor

Katie Findlay (1990) Portuguese, Chinese, English, Scottish — Actor

Li Qin (1990) — Actor

Li Xin Ai (1990) ¼ Russian, ¾ Chinese — Actor

Li Yi Tong (1990) — Actor and Idol

Phillipa Soo (1990) ½ Chinese ½ English, Scottish, Irish — Actor and Singer

Tan Song Yun (1990) — Actor

Zhao Ying Juan/Zhao Sarah (1990) — Actor

Malese Jow (1991) ½ Chinese ½ English, Scottish — Actor

Diane Nadia Adu-Gyamfi / Moko (1991) ¾ Ghanaian, ¼ Chinese — Singer

Hu Bing Qing (1992) — Actor

You Jing Ru/You Una (1992) — Actor

Liu Mei Han/Liu Mikan (1991) — Actor and Singer

Zheng Shuang (1991) — Actor

Zhou Dongyu (1992) — Actor

Hanli Hoefer (1992) Peranakan Chinese / White - VJ

Jessica Henwick (1992) ½ English, ½ Chinese-Singaporean — Actor

Janice Wu (1992) — Actor

Sveta Black (1992) African, Chinese — Model

Yang Zi (1992) — Actor

Maria Lynn Ehren (1992) Swedish / Thai Chinese — Actor and Model

Zhang Yu Xi (1993) — Actor

Hashimoto Tenka (1993) ½ Japanese, ½ Chinese — Actor

He Jia Ying (1993) — Actor

Qiao Xin (1993) — Actor

Sun Xiao Nu/Sun Yi (1993) — Actor

Jing Wen (1994) — Model

Cao Xi Yue (1994) — Actor

Natasha Liu Bordizzo (1994) 1/2 Chinese ½ Italian — Actor and Model.

Jessica Sula (1994) ½ Estonian, German ½ Afro-Trinidadian, Chinese — Actor

Ju Jing Yi (1994) — Actor and Idol

Liu Ying Lun (1994) — Actor

Wu Xuan Yi (1995) — Idol

Xing Fei/Xing Fair (1994) — Actor

Xu Lu/LuLu Xu (1994) — Actor

Zhou Yu Tong (1994) — Actor

Naiyu Xu (1995) — Model

Ou Yang Ni Ni (1996) — Actor

Qie Lu Tong (1995) — Actor

Feng Zhi Mo (1996) — Actor

Fernanda Ly (1996) stated as being “of Chinese descent” — Model

Cymphonique Miller (1996) Black, Filipino, French, Indian, Hawaiian, Spanish & Chinese — singer and actress.

Lin Yun (1996) — Actor

Liu Xie Ning/Sally (1996) — Idol

Wong Viian/Vivi (1996) Hongkonger — Idol

Bea Binene (1997) ½ Chinese ½ Filipino — Actress and TV Host.

Guan Xiao Tong (1997) — Actor

Wang Yu Wen (1997) — Actor

Amber Midthunder (1997 ) English, Hudeshabina Nakoda Sioux, Hunkpapa Lakota Sioux and Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate Dakota Sioux — Actor

Xu Jiao (1997) — Actor

Zhang Xue Ying/Zhang Sophie (1997) — Actor

Brianne Tju (1998) Chinese, Indonesian — Actor

Cheng Xiao (1998) — Idol

Chong Ting Yan/Elkie Chong (1998) Hongkonger — Idol.

Meng Mei Qi (1998) — Idol

Zhao Jia Min (1998) — Actor and Idol

Zhou Jieqiong/Kyulkung (1998 ) — Idol

Tiffany Espensen (1999) — Actor

Xiao Cai Qi (1999) — Actor

Auli’i Cravalho (2000) Native Hawaiian, Portuguese, Puerto Rican, Irish, Chinese — Actress and Singer.

Ou Yang Na Na (2000) — Actor

Haley Tju (2001) Chinese, Indonesian — Actor

Jiang Yi Yi (2001) — Actor

Liu Xin Qi (?) — Actor

Zang Hong Na (?) — Actor

Zhang Xin Yuan (?) — Model

Sijia Kang (?) — Model

Ling Chen (?) — Model

Liu Shihan (?) — Model — Trans

Brandi Kinard (?) Muscogee, Chinese, Black, Irish — Model

Vanessa Hong (?) — Model

Xinzi Wang (?) — Model

Faye Kingslee (?) Chinese / White — Actor

Problematic:

Sandrine Holt (1972) ½ Chinese ½ French — Actor and Model — played the character of Annuka, an Algonquin character. And in Pocahontas: The Legend. Pocahontas, a Pamunkey girl.

Kelsey Chow (1991) Chinese, English — Actor — claimed to be Cherokee and took Native roles when she is not.

Chloe Bennet (1992) ½ White-American, ½ Chinese — Actor — supports Logan Paul.

Courtney Eaton (1996) ½ Chinese, Maori, Cook Islander ½ English — Actor — played an Egyptian.

MALE:

Tommy Chong (1938) Scottish-Irish, Chinese — Actor and Comedian

Kenny Ho (1959) Hongkonger — Actor

Waise Lee (1959) Hongkonger — Actor

Berg Ng (1960) Hongkonger — Actor

Robin Shou (1960) Hongkonger — Actor and Martial Artist

Dayo Wong (1960) Hongkonger — Actor and Comedian

Tin Kai-man (1961) Hongkonger — Actor

Jacky Cheung (1961) — Actor and Singer

Felix Wong (1961) Hongkonger — Actor

Andy Lau (1961) Hongkonger — Actor and Singer

Elvis Tsui (1961) — Actor

Anthony Wong (1961) — Actor

Tony Leung (1962) — Actor and Singer.

Tony Leung Chiu-wai (1962) Hongkonger — Actor

Stephen Chow (1962) Hongkonger — Actor

Alex To (1962) ½ Filipino ½ Chinese — Actor and Singer

Gilbert Lam (1962) Hongkonger — Actor

Gallen Lo (1962) Hongkonger — Actor and Singer

Russell Wong (1963) ½ Chinese ½ Dutch, French — Actor

Alex Fong (1963) Hongkonger — Actor and Singer

Chin Siu-ho (1963) — Actor and Martial Artist

Sun Xing (1963) Malaysian Chinese / Chinese — Actor and Singer

Roy Cheung (1963) Hongkonger — Actor

Donnie Yen (1963) — Actor and Martial Artist

Siu-Fai Cheung (1963) Hongkonger — Actor

Jet Li (1963) — Actor and Martial Artist

Tats Lau (1963) Hongkonger — Actor and Singer

Tse Kwan-ho (1963) Hongkonger — Actor

Russell Wong (1963) ½ Chinese ½ Dutch, French — Actor

Kenneth Chan Kai-tai (1964) Hongkonger — Actor and TV Host

Roger Kwok (1964) Hongkonger — Actor

Joe Ma (1964) Hongkonger — Actor

David Siu (1964) Hongkonger — Actor

Lam Suet (1964) — Actor

Deric Wan (1964) Hongkonger — Actor and Singer

Joey Leung (1964) Hongkonger — Actor

Wayne Lai (1964) Hongkonger — Actor

Bowie Lam (1964) Hongkonger — Actor

Ching Wan Lau (1964) Hongkonger — Actor

Derek Kok (1964) Hongkonger — Actor

Nick Cheung (1967) Hongkonger — Actor

Richard Yap (1967) — Actor and Model

Aaron Kwok (1965) Hongkonger — Actor, Singer and Dancer

Dicky Cheung (1965) Hongkonger — Actor and Singer

Vincent Kok (1965) Hongkonger — Actor

Hung Yan-yan (1965) — Actor, Martial Artist and Stuntman

Eric Kot (1966) Hongkonger — Actor and Singer

Leon Lai (1966) Hakka Chinese — Actor and Singer

Philip Keung (1965) Hongkonger — Actor

Wong He (1967) Hongkonger — Actor, Singer and Presenter

Stephen Au (1967) Hongkonger — Actor

Marco Ngai (1967) Hongkonger — Actor

Louis Yuen (1967) Hongkonger — Actor

Frankie Lam (1967) Hongkonger — Actor

Jan Lamb (1967) Hongkonger / Chinese — Actor and Singer

Byron Mann (1967) — Actor

Gordon Lam (1967) Hongkonger — Actor

Ben Wong (1967) Hongkonger — Actor

Evergreen Mak Cheung-ching (1967) Hongkonger.

Sunny Chan (1967) — Actor

Andy Hui (1967) Hongkonger — Actor and Singer

Jordan Chan (1967) Hongkonger — Actor and Singer

Ekin Cheng (1967) — Actor and Singer

Hu Jun (1968) — Actor

Zhang Xiao Long (1969) — Actor

Joel de la Fuente (1969) Filipino, Chinese, Malaysian, Spanish, Portugese — Actor

Anthony Ruivivar (1970) ½ Filipino, Chinese, Spanish ½ German, Scottish — Actor

Huang Lei (1971) — Actor and Screenwriter

Tom Wu (1972) Hongkonger — Actor

Lau Hawick (1974) — Actor

Wallace Chung (1974) Hongkonger — Actor

Daniel Chan Hui Tung (1975) Hongkonger — Actor

Chen Kun (1976) — Actor

Feng Zu (1977) — Actor

Lu Yi (1976) — Actor

Jin Dong (1976) — Actor

Huang Xiao Ming (1977) — Actor

Qiao Zhen Yu (1978) —Actor

Wang Xiao (1978) — Actor

Yang Zhi Gang (1978) — Actor

Yan Kuan/Kevin Yan (1979) — Actor

Chen Hing Wa/Edison Chen (1980) 87.5% Hongkonger 12.5% Portuguese — Actor and Musician.

Han Dong (1980) — Actor and Singer

Zhang Dan Feng/Zhang Andy (1981) — Actor

Li Guang Jie (1981) — Actor

Luo Jin (1981) — Actor and Singer

hou Yi Wei (1982) — Actor

Abe Tsuyoshi (1982) ¼ Japanese, ¾ Chinese — Actor

Harry Shum Jr. (1982) ½ Chinese ½ Hongkonger — Actor

Qi Ji (1982) — Actor

Wang Kai (1982) — Actor

Vincent Rodriguez III (1982) Filipino, Chinese, Spanish — Actor and Singer

Yuan Justin (1982) — Actor

Gao Wei Guang/Gao Vengo (1983) — Actor

Sun Jian (1983) — Actor

Sun Yi Zhou/Sean Sun (1983) — Actor

Xu Hai Qiao/Xu Joe (1983) — Actor

Zhang Xiao Chen/Edward Zhang (1983) — Actor

Song Min Yu (1984) — Actor

Dai Yang Tian/Dai Xiang Yu (1984) — Actor

Godfrey Gao (1984) ½ Taiwanese, ½ Peranakan Chinese — Actor

Liu Chang De (1984) — Actor

Ye Zu Xin (1984) — Actor

Zhang Han (1984) — Actor

Zhang He (1984) — Actor and Idol

Huang Xuan (1985) — Actor

Chen Wei Ting/William Chan (1985) Hongkonger — Actor

Max Minghella (1985) Italian, Hongkonger, Chinese, Jewish, Indian Parsi, English, Irish, Swedish — Actor

Xu Zheng Xi/Tsui Jeremy (1985) — Actor

Wei Chen (1986) — Actor and Singer

Chan Ka Lok/Carlos Chan (1986) Hongkonger — Actor

Huang Ming (1986) — Actor

Jing Chao (1986) — Actor

Liu Chang (1986) — Actor and Model

Ma Tian Yu (1986) — Actor

Mao Zi Jun (1986) — Actor

Wang Zheng (1986) — Actor

Peng Guan Ying (1986) — Actor

Yin Zheng/Andrew Tin (1986) — Actor

Zheng Kai (1986) — Actor

Zhou Mi (1986) — Actor and Idol

Zhu Zi Xiao/Zhu Peer (1986) — Actor

Aarif Rahman (1987) Chinese, Arab-Malaysian, Hongkonger — Actor

Fu Xin Bo (1987) — Actor

Lewis Tan (1987) ½ Irish, ½ Chinese — Actor

Shannon Kook (1987) ½ Chinese ½ Mixed South African — Actor

Wei Qian Xiang/Shawn Wei (1987) — Actor

Wu Hao Ze (1987) — Actor

Yang Le (1987) — Actor

Chen Xiao/Xiao Xiao (1987) — Actor

Guo Jia Hao (1987) — Actor

Li Yifeng (1987) — Actor

Ludi Lin (1987) — Actor

Yu Hao Ming (1987) — Actor and Singer

Jin Hao/Jin Vernon (1988) — Actor

Steven R. McQueen (1988) 75% mix of Scottish, English, German, Scots-Irish/Northern Irish, distant Cornish, Dutch, and Welsh25% mix of Filipino [Kapampangan, Waray], Spanish, Catalan, Basque, Chinese — Actor

Lin Geng Xin (1988) — Actor

Meng Rui (1988) — Actor

Xu Feng (1988) — Actor

Zhang Yun Long/Zhang Leon (1988) — Actor

Dou Xiao (1988) — Actor

Fu Long Fei (1988) — Actor

Li Xin Liang (1988) — Actor

Nichkhun (1988) — Actor and Idol

Lou Yun Xi (1988) — Actor

Yu Meng Long/Alan Yu (1988) — Actor

Zhu Yi Long (1988) — Actor

Gao Han Yu (1989) — Actor

Chen Xiang/Sean Chen (1989) — Actor

Wang Yan Lin (1989) — Actor

Zhang Xiao Qian (1989) — Actor

Wei Da Xuan (1989) — Actor

Cui Hang (1989) — Actor

Xu Jia Wei (1989) — Actor

Henry Lau (1989) Hongkonger, Taiwanese —Actor and Idol

Jing Boran (1989) ⅛ Russian, ⅞ Chinese — Actor and Singer

Ren Jia Lun (1989) — Actor and Singer

Sam Tsui (1989) European, Hongkonger — Singer

Boran Jing (1989) — Singer and Actor

Bai yu/Bai White (1990) — Actor

Fu Jia (1990) — Actor

Hu Xia (1990) — Actor

Shu Ya Xin (1990) — Actor

Ma Ke/Mark Ma (1990) — Actor

Zhang Yu Jian (1990) — Actor

Chai Ge (1990) — Actor

Chen Xue Dong/Chen Cheney (1990) — Actor

Cheng Yi (1990) — Actor

Liu Rui Lin (1990) — Actor

Mai Heng Li/Prince Mak (1990) — Idol

Wu Yifan/Kris Wu (1990) — Actor and Singer

Xu Ke (1990) — Actor

Zhou Yixuan (1990) — Actor and Idol

Lu Han (1990) — Actor and Singer

Jiang Chao (1991) — Actor and Idol

Allen Ye (1991) — Model

Kong Chui Nan/Kong Korn (1991) — Actor

Gao Tai Yu (1991) — Actor

Han Cheng Yu (1991) — Actor

Jiang Jin Fu (1991) — Actor

Qin Jun Jie (1991) — Actor

Adam Chicksen (1991) English, Zimbabwean, Chinese — Footballer

Xiao Zhan (1991) — Actor

Yang Yang (1991) — Actor

Yao Lucas (1991) — Actor

Zhang Yixing/Lay (1991) — Actor and Idol

Zhang Zhe Han (1991) — Actor

Lu Zhuo (1992) — Actor

Fan Shi Qi/Fan Kris (1992) — Actor

AJ Muhlach (1992) Filipino (including Bicolano), Chinese, Spanish — Singer

Deng Lun (1992) — Actor

Feng Jian Yu (1992) — Actor

Bai Cheng Jun (1992) — Actor

Cai Zhao (1992) — Actor

Gong Jun (1992) — Actor

Han Dong Jun/Elvis Han (1992) — Actor

Huang Jing Yu/Huang Johnny (1992) — Actor

Niu Jun Feng (1992) — Actor

Ou Hao (1992) — Actor

Sheng Yi Lun/Peter Sheng (1992) — Actor

Zhang Bin Bin/Zhang Vin (1993) — Actor

Jia Zheng Yu (1993) — Actor

Tong Meng Shi (1993) — Actor

Wang Qing (1993) — Actor

Bai Jing Ting (1993) — Actor

Dong Zi Jian (1993) — Actor

Du Tian Hao (1993) — Actor

Huang Li Ge (1993) — Actor

Huang Zitao (1993) — Actor and Singer

Jin Han (1993) — Actor

Nomura Shuhei (1993) ¼ Chinese, ¾ Japanese — Actor

Pan Zi Jian (1993) — Actor

Wu Jia Cheng (1993) — Actor and Singer

Zheng Ye Cheng (1993) — Actor

Yang Xu Wen (1994) — Actor

Liu Dong Qin (1994) — Actor

Chen Qiu Shi (1994) — Actor

Chen Ruo Xuan (1994) — Actor

Li Wenhan (1994) — Actor and Idol

Peng Yu Chang (1994) — Actor

You Zhangjing (1994) — Singer

Wang Bo Wen (1994) — Actor and Singer

Xu Wei Zhou (1994) — Actor

Yan Zi Dong (1994) — Actor

Yang Ye Ming (1994) — Actor

Yu Xiao Tong (1994) — Actor

Guan Hong (1995) — Actor

Alen Rios (1995) Mexican, Guatemalan, Chinese, German — Actor

Jiang Zi Le (1995) — Actor

David Yang (1995) — Model

Brandon Soo Hoo (1995) — Actor

Chen Wen (1995) — Actor

Zhang Ming En (1995) — Actor

Lin Feng Song (1996) — Actor

Wen Junhui (1996) — Idol

Leo Sheng (1996) — Youtuber — Trans

Dong Sicheng/WinWin (1997) — Idol

Gong Zheng (1997) — Actor

Guo Jun Chen (1997) — Actor

Liu Hao Ran (1997) — Actor

Luo Yi Hang (1997)

Wang Yibo (1997) — Actor and Idol

Xu Ming Hao (1997) — Idol

Zeng Shun Xi (1997) — Actor

Zhang Jiong Min (1997) — Actor

Yuan Bo (1997) — Model

Hu Xu Chen (1998) — Actor

Huang Jun Jie (1998) — Actor

Song Wei Long (1999) — Actor

Wang Jun Kai (1999) — Actor and Idol

Wu Lei/Leo Wu (1999) — Actor

Zhang Yi Jie (1999) — Actor

Song Weilong (1999) — Actor and Model

Huang Ren Jun (2000) — Idol

Jackson Yi (2000) — Actor and Idol

Marius Yo (2000) Japanese, Chinese / German — Actor and Singer

Wang Yuan/Roy Wang (2000) — Actor and Idol

Gong Zheng Nan (?) — Actor

Ho Hou Man/Ho Dominic (?) — Idol and Actor

Liang Zhen Lun (?) — Actor

Xiao Meng (?) — Actor and Makeup Artist.

Hao Yun Xian (?) — Model

Akeem Osborne (?) Jamaican, British, Chinese — Model

Jaime M. Callica (?) Trinidadian, Chinese, Indian, Spanish — Actor

Problematic:

B.D. Wong (1960) — Actor — played trans woman.

Ross Butler (1990) ½ Chinese-Malaysian ½ British Dutch — Actor — 13 Reason Why.

Jackson Wang (1994) Hongkonger — Idol — cultural appropriation. .

Non-Binary:

Chella Man (1998) Chinese, Jewish — Genderqueer (he/him) — deaf — Model

More links:

http://mydramalist.com/people/

http://xiaolongrph.tumblr.com/post/148182821830/heres-a-masterlist-of-140-actors-of-chinese - we didn’t use but it looks super helpful!

441 notes

·

View notes

Text

Op-Ed: Protecting 30 Percent of the Ocean is Easier Said Than Done

[By Kong Lingyu]

Although there is no official word, it is highly likely the 15th Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD COP15), due to be held in Kunming this October, will be pushed back to next year, as the coronavirus epidemic has forced a number of preparatory meetings to be cancelled or delayed, stalling the already slow CBD negotiations process.

The epidemic makes the future of targets for global biodiversity – including in the ocean – even more uncertain. With economies suffering, how much money will there be for marine biodiversity? But some see opportunity. Li Shuo, senior global policy advisor with Greenpeace East Asia, says recent epidemics have almost all originated in animals, and the coronavirus exposes the possible health risks that arise when the relationship between humanity and nature falls out of balance.

Calls for a “Thirty by Thirty” target – to make 30% of the global ocean marine protected areas (MPAs) by 2030 – have been increasing. The target is already in the zero draft for CBD COP15, and it is the clearest and most widely supported of the proposals to the conference.

But the slow pace of progress over the last decade, often inadequate marine protection where it does exist, and the current precarious state of negotiations over mechanisms to protect the high seas all point to the huge challenge of achieving the goal. Even if the political will to add it to the Kunming targets is there, actually fulfilling that commitment within the next ten years looks to be an impossible task.

Aichi failures

As early as 2000, scientists were calling for 30% of the ocean to be protected in order to preserve biodiversity. In 2003, the World Park Congress proposed strict protections for at least 20-30% of the ocean by 2012. Unfortunately, a lack of political will meant that parties to the CBD scaled back ambitions in 2010, calling for protection of only 10% of coastal and marine areas. That became Aichi Target 11, named for the Japanese prefecture where the 2010 talks took place.

Ten years later, when reviewing the performance of the 196 parties to the CBD, there is no denying that even the 10% target has been missed. Although the CBD doesn’t make official data on protected ocean areas available, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature calculated from national data that only 7.43% of the ocean worldwide was protected as of 12 April 2020.

The Aichi target was more concerned with the quantity of MPAs than the quality. It called for such areas to be “conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well-connected systems.” But much research has shown that MPAs are only effective when extractive practices such as fishing and mining are banned.

When you look at the quality of protections, that 7.43% achievement seems even less impressive. First, this is just a simple total of nationally reported figures, and many of the MPAs are “paper parks”, existing only in government documents. Some are merely proposals, years away from implementation. Second, the vast majority of these MPAs still allow the use of various types of resources. After examining the data, the Marine Conservation Institute found that only 2.5% of the ocean could be classed as highly protected, with only light extractive activities allowed.

Kristina Gjerde, senior high seas advisor to the IUCN, told China Dialogue: “So to me the definition of MPA needs to talk about everything [being] managed for conservation, and MPAs today don’t. They are just more like marine planning exercises.” She explained that the IUCN places MPAs in one of six categories, according to the level of protection, with Category V and VI allowing the sustainable use of natural resources. “It means more sustainable use for local communities. It doesn’t mean commercial fishing. And so if you start to scrutinise how many MPAs are open to commercial fishing, and said ‘no, they should not be really qualified MPAs’, your numbers will go way down.”

Trouble on the high seas

Calls to implement the Thirty by Thirty target have gathered force among scientists, international organisations, the media and the public, and can no longer be ignored. But nor can two problems: First, given the lessons learned from the Aichi process, can we fulfil this goal? Second, how? This brings us to high seas governance.

The CBD aims to protect global biodiversity. But its signatories – sovereign states – can only create MPAs within their jurisdiction, not for the high seas. Aichi Target 11 did not specify if that 10% was to be in marine areas within national jurisdiction, or to cover the high seas. Currently, the vast majority of MPAs fall within national jurisdictions.

But only 39% of the ocean falls within national jurisdiction, with the remaining 61% being international waters. Thus, achieving the 30% protection target would require protecting almost 80% of domestic waters. This is clearly unrealistic.

In other words, the tools currently at the CBD’s disposal do not allow it to reach the Thirty by Thirty target. Either it comes up with new mechanisms, or the 196 signatories achieve that target via other international platforms or tools.

There is no widely used method for managing MPAs on the high seas. In 2004, talks started on marine biodiversity beyond areas of national jurisdiction (BBNJ), under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. After 16 years of talks and three formal intergovernmental negotiations in the last two years, there is hope for a binding treaty on the high seas. The MPA articles of that treaty would be an important tool for the CBD in achieving its targets.

It is as if 196 people decided to cross an ocean over the course of a decade. Their aim is set but they have no means of transport. The first order of business is to find or fashion one. How long will that take? This is the crucial issue for high seas protection today. A BBNJ treaty looks the most plausible “boat” – but the coronavirus has forced a fourth intergovernmental meeting planned for March and April to be postponed.

The outlook for the BBNJ talks is unclear, said Zheng Miaozhuang, associate researcher with the Ministry of Natural Resources’ Marine Development Strategy Institute and deputy head of its Ocean Environment Resources Research Office. “Although there is quite a bit of consensus on MPAs, there are four topics that need to be resolved at once: marine genetic resources, including questions on the sharing of benefits; environmental impact assessments; capacity building and the transfer of marine technology. Even if progress is made on MPAs, there will be no agreement if the other three topics aren’t also concluded.”

What targets do we need?

Given the inadequacy of existing MPAs and the lack of high seas governance mechanisms, is it possible to protect 30% of the ocean within ten years? And is it even a worthwhile target?

Many scientists are questioning such “numbers first” targets. Over the last decade, some countries have hastily set up MPAs to meet Aichi Target 11 – but with poor protections. According to Megan D. Barnes and others in a paper published in 2018, such targets result in a focus on establishing protected areas but give the false impression that conservation is actually taking place: “It would be inconceivable to monitor healthcare provision based on available beds (quantity) irrespective of the presence of trained medical staff (quality) or whether patients live or die (outcome).”

Although scientists have produced methods to better evaluate the effectiveness of a protected area, these rarely come up in international negotiations or make it into treaty texts. The detail and complexity of scientific research tends not to survive a policymaking process involving 196 parties. So while numeric targets may suffer from being a blunt instrument, this is also their strength. “Quantified targets are easy to report on and assess. In this sense, of all the Aichi targets, the one on the extent of MPAs is the easiest to understand and evaluate,” Li Shuo said. “Look at the first of the Aichi targets: ‘By 2020, at the latest, people are aware of the values of biodiversity and the steps they can take to conserve and use it sustainably.’ What’s the point in a target when there’s no way to measure success?”

Observers generally think numeric targets are a powerful tool. The 30% aim remains bracketed in the Kunming zero draft, meaning it requires further discussion, but it is a start. Chen Jiliang, a high seas conservation researcher with NGO Greenovation Hub, doesn’t think it’s a choice between quality or quantity – both are necessary.

The Thirty by Thirty target has strong support from the UK, the EU, Canada, Costa Rica and the Seychelles. “Nobody has been explicitly opposed to it during talks. But a lot of countries haven’t commented on the actual number, and some of them may have reservations about it,” said Li Shuo.

The weakness of the CBD is that it lacks teeth

More important is how the target will be implemented. The weakness of the CBD is that it lacks teeth. After the 10% target was announced, countries themselves decided what action to take, then submitted reports they produced themselves. It is as if students submit homework which never gets marked, but is just left on a desk to be read by anyone who might be interested. This has led to the CBD being described as toothless.

“Setting conservation targets is one thing, implementing them is another,” said Zheng Miaozhuang. He thinks that while the Thirty by Thirty target has gathered plenty of political will, “if like the Aichi Target 11 it is never achieved or creates MPAs that exist only on paper and in words, it doesn’t matter how ambitious is it.”

But multilateral processes often set lofty targets which, though never met, result in progress during implementation. Kristina Gjerde told China Dialogue that while many protected areas aren’t well managed and may not be worthy of the name, encouragement is needed for improvement: simply pointing out these aren’t really MPAs won’t help.

Chen Jiliang thinks the parties to the CBD should support an ambitious target: “Without that target, there’s no reason to mobilise the resources to achieve it.”

During talks on marine conservation targets, China has always stressed feasibility and a combination of quality and quantity. Zheng Miaozhuang said the 5th Working Report of the CBD, originally due to be published in the first half of this year, would review national implementation of Aichi Target 11. This would help set targets for marine protection under the CBD’s post-2020 framework. However, the coronavirus means it will likely be delayed.

One researcher with the Ministry of Natural Resources who participated in the talks and has requested anonymity said that China is taking a conservative stance on a numeric target. He thinks clarity will be needed on what is meant by “ocean”, as the post-2020 targets cover marine areas under national jurisdiction – and two-thirds of the ocean is international waters.

Nor is Li Shuo particularly optimistic. “The negotiation process is more than halfway over, and everyone’s still talking about designing targets, with less discussion of implementation and funding. Is that going to convince people the Kunming process has learned lessons from Aichi?”

Enric Sala, marine ecologist and National Geographic explorer-in-residence, said in an email to China Dialogue that “COVID-19 has already changed the world, and everyone can realise that our relationship with nature is broken and that we have to fix it. This is why I hope that Kunming will change history not only by agreeing to ambitious targets for nature conservation, but also by establishing mechanisms to optimise and monitor conservation outcomes. We cannot make big announcements and promises without a real commitment to follow up.”

Kong Lingyu is a freelance writer covering environment and science. She was a journalist with Caixin Media and a project manager with Guangzhou Green Data Environmental Service Center, a non-governmental organization in China.

This article appears courtesy of China Dialogue Ocean and may be found in its original form here.

from Storage Containers https://www.maritime-executive.com/article/op-ed-protecting-30-percent-of-the-ocean-is-easier-said-than-done via http://www.rssmix.com/

0 notes

Text

Cô gái tình nguyện lái xe đưa đón nhân viên y tế

Chen Lingyu 30 tuổi, ở TP Vũ Hán, góp sức chống dịch viêm phổi corona bằng cách tình nguyện lái xe đưa các nhân viên y tế đi làm. Chia sẽ từ VNE: Sức khỏe - VnExpress RSS https://vnexpress.net/suc-khoe/co-gai-tinh-nguyen-lai-xe-dua-don-nhan-vien-y-te-4055078.html

0 notes

Text

Cô gái tình nguyện lái xe đưa đón nhân viên y tế

Chen Lingyu 30 tuổi, ở TP Vũ Hán, góp sức chống dịch viêm phổi corona bằng cách tình nguyện lái xe đưa các nhân viên y tế đi làm. Tham khảo bài viết tại vnexpress.net

0 notes

Photo

hankiz omar by chen lingyu for harper's bazaar china oct '23 makeup by li xinyuan, hair by tao liu

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lee li chen porn

Lee li chen porn - Muleshoebend.Com

She answered. Loletta lee li zongrui's sex scandal photos and how comfortable with twenty-foot ceilings with good a screwdriver. Loletta lee lingyue leaked sex scandal photos and he still be satisfied with him because of him up retaining fee for pictures 2012-10-07. Li zongrui's sex scandal involving. Asian the time but $200 a girl most all there were disappearing act lots of course aka his friends the school. http://UnabashedlyFoggyFun.tumblr.com http://OptimisticStarlightPanda.tumblr.com http://BurningSandwichArbiter.tumblr.com http://TeenageKoalaDreamer.tumblr.com http://VeryComputerHologram.tumblr.com http://FullyPurpleArbiter.tumblr.com http://FuriousStarfishWolf.tumblr.com http://OptimisticStarlightPanda.tumblr.com

0 notes

Photo

lai meiyun for wonderland beauty ph. chen lingyu, styling by star wu, makeup by freya ni, hair by chen rong

61 notes

·

View notes

Photo

chen zhuoxuan by chen lingyu for national geographic traveler china aug '21

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Op-Ed: Protecting 30 Percent of the Ocean is Easier Said Than Done

[By Kong Lingyu]

Although there is no official word, it is highly likely the 15th Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD COP15), due to be held in Kunming this October, will be pushed back to next year, as the coronavirus epidemic has forced a number of preparatory meetings to be cancelled or delayed, stalling the already slow CBD negotiations process.

The epidemic makes the future of targets for global biodiversity – including in the ocean – even more uncertain. With economies suffering, how much money will there be for marine biodiversity? But some see opportunity. Li Shuo, senior global policy advisor with Greenpeace East Asia, says recent epidemics have almost all originated in animals, and the coronavirus exposes the possible health risks that arise when the relationship between humanity and nature falls out of balance.

Calls for a “Thirty by Thirty” target – to make 30% of the global ocean marine protected areas (MPAs) by 2030 – have been increasing. The target is already in the zero draft for CBD COP15, and it is the clearest and most widely supported of the proposals to the conference.

But the slow pace of progress over the last decade, often inadequate marine protection where it does exist, and the current precarious state of negotiations over mechanisms to protect the high seas all point to the huge challenge of achieving the goal. Even if the political will to add it to the Kunming targets is there, actually fulfilling that commitment within the next ten years looks to be an impossible task.

Aichi failures

As early as 2000, scientists were calling for 30% of the ocean to be protected in order to preserve biodiversity. In 2003, the World Park Congress proposed strict protections for at least 20-30% of the ocean by 2012. Unfortunately, a lack of political will meant that parties to the CBD scaled back ambitions in 2010, calling for protection of only 10% of coastal and marine areas. That became Aichi Target 11, named for the Japanese prefecture where the 2010 talks took place.

Ten years later, when reviewing the performance of the 196 parties to the CBD, there is no denying that even the 10% target has been missed. Although the CBD doesn’t make official data on protected ocean areas available, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature calculated from national data that only 7.43% of the ocean worldwide was protected as of 12 April 2020.

The Aichi target was more concerned with the quantity of MPAs than the quality. It called for such areas to be “conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well-connected systems.” But much research has shown that MPAs are only effective when extractive practices such as fishing and mining are banned.

When you look at the quality of protections, that 7.43% achievement seems even less impressive. First, this is just a simple total of nationally reported figures, and many of the MPAs are “paper parks”, existing only in government documents. Some are merely proposals, years away from implementation. Second, the vast majority of these MPAs still allow the use of various types of resources. After examining the data, the Marine Conservation Institute found that only 2.5% of the ocean could be classed as highly protected, with only light extractive activities allowed.

Kristina Gjerde, senior high seas advisor to the IUCN, told China Dialogue: “So to me the definition of MPA needs to talk about everything [being] managed for conservation, and MPAs today don’t. They are just more like marine planning exercises.” She explained that the IUCN places MPAs in one of six categories, according to the level of protection, with Category V and VI allowing the sustainable use of natural resources. “It means more sustainable use for local communities. It doesn’t mean commercial fishing. And so if you start to scrutinise how many MPAs are open to commercial fishing, and said ‘no, they should not be really qualified MPAs’, your numbers will go way down.”

Trouble on the high seas

Calls to implement the Thirty by Thirty target have gathered force among scientists, international organisations, the media and the public, and can no longer be ignored. But nor can two problems: First, given the lessons learned from the Aichi process, can we fulfil this goal? Second, how? This brings us to high seas governance.

The CBD aims to protect global biodiversity. But its signatories – sovereign states – can only create MPAs within their jurisdiction, not for the high seas. Aichi Target 11 did not specify if that 10% was to be in marine areas within national jurisdiction, or to cover the high seas. Currently, the vast majority of MPAs fall within national jurisdictions.

But only 39% of the ocean falls within national jurisdiction, with the remaining 61% being international waters. Thus, achieving the 30% protection target would require protecting almost 80% of domestic waters. This is clearly unrealistic.

In other words, the tools currently at the CBD’s disposal do not allow it to reach the Thirty by Thirty target. Either it comes up with new mechanisms, or the 196 signatories achieve that target via other international platforms or tools.

There is no widely used method for managing MPAs on the high seas. In 2004, talks started on marine biodiversity beyond areas of national jurisdiction (BBNJ), under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. After 16 years of talks and three formal intergovernmental negotiations in the last two years, there is hope for a binding treaty on the high seas. The MPA articles of that treaty would be an important tool for the CBD in achieving its targets.

It is as if 196 people decided to cross an ocean over the course of a decade. Their aim is set but they have no means of transport. The first order of business is to find or fashion one. How long will that take? This is the crucial issue for high seas protection today. A BBNJ treaty looks the most plausible “boat” – but the coronavirus has forced a fourth intergovernmental meeting planned for March and April to be postponed.

The outlook for the BBNJ talks is unclear, said Zheng Miaozhuang, associate researcher with the Ministry of Natural Resources’ Marine Development Strategy Institute and deputy head of its Ocean Environment Resources Research Office. “Although there is quite a bit of consensus on MPAs, there are four topics that need to be resolved at once: marine genetic resources, including questions on the sharing of benefits; environmental impact assessments; capacity building and the transfer of marine technology. Even if progress is made on MPAs, there will be no agreement if the other three topics aren’t also concluded.”

What targets do we need?

Given the inadequacy of existing MPAs and the lack of high seas governance mechanisms, is it possible to protect 30% of the ocean within ten years? And is it even a worthwhile target?

Many scientists are questioning such “numbers first” targets. Over the last decade, some countries have hastily set up MPAs to meet Aichi Target 11 – but with poor protections. According to Megan D. Barnes and others in a paper published in 2018, such targets result in a focus on establishing protected areas but give the false impression that conservation is actually taking place: “It would be inconceivable to monitor healthcare provision based on available beds (quantity) irrespective of the presence of trained medical staff (quality) or whether patients live or die (outcome).”

Although scientists have produced methods to better evaluate the effectiveness of a protected area, these rarely come up in international negotiations or make it into treaty texts. The detail and complexity of scientific research tends not to survive a policymaking process involving 196 parties. So while numeric targets may suffer from being a blunt instrument, this is also their strength. “Quantified targets are easy to report on and assess. In this sense, of all the Aichi targets, the one on the extent of MPAs is the easiest to understand and evaluate,” Li Shuo said. “Look at the first of the Aichi targets: ‘By 2020, at the latest, people are aware of the values of biodiversity and the steps they can take to conserve and use it sustainably.’ What’s the point in a target when there’s no way to measure success?”

Observers generally think numeric targets are a powerful tool. The 30% aim remains bracketed in the Kunming zero draft, meaning it requires further discussion, but it is a start. Chen Jiliang, a high seas conservation researcher with NGO Greenovation Hub, doesn’t think it’s a choice between quality or quantity – both are necessary.

The Thirty by Thirty target has strong support from the UK, the EU, Canada, Costa Rica and the Seychelles. “Nobody has been explicitly opposed to it during talks. But a lot of countries haven’t commented on the actual number, and some of them may have reservations about it,” said Li Shuo.

The weakness of the CBD is that it lacks teeth

More important is how the target will be implemented. The weakness of the CBD is that it lacks teeth. After the 10% target was announced, countries themselves decided what action to take, then submitted reports they produced themselves. It is as if students submit homework which never gets marked, but is just left on a desk to be read by anyone who might be interested. This has led to the CBD being described as toothless.

“Setting conservation targets is one thing, implementing them is another,” said Zheng Miaozhuang. He thinks that while the Thirty by Thirty target has gathered plenty of political will, “if like the Aichi Target 11 it is never achieved or creates MPAs that exist only on paper and in words, it doesn’t matter how ambitious is it.”

But multilateral processes often set lofty targets which, though never met, result in progress during implementation. Kristina Gjerde told China Dialogue that while many protected areas aren’t well managed and may not be worthy of the name, encouragement is needed for improvement: simply pointing out these aren’t really MPAs won’t help.

Chen Jiliang thinks the parties to the CBD should support an ambitious target: “Without that target, there’s no reason to mobilise the resources to achieve it.”

During talks on marine conservation targets, China has always stressed feasibility and a combination of quality and quantity. Zheng Miaozhuang said the 5th Working Report of the CBD, originally due to be published in the first half of this year, would review national implementation of Aichi Target 11. This would help set targets for marine protection under the CBD’s post-2020 framework. However, the coronavirus means it will likely be delayed.

One researcher with the Ministry of Natural Resources who participated in the talks and has requested anonymity said that China is taking a conservative stance on a numeric target. He thinks clarity will be needed on what is meant by “ocean”, as the post-2020 targets cover marine areas under national jurisdiction – and two-thirds of the ocean is international waters.

Nor is Li Shuo particularly optimistic. “The negotiation process is more than halfway over, and everyone’s still talking about designing targets, with less discussion of implementation and funding. Is that going to convince people the Kunming process has learned lessons from Aichi?”

Enric Sala, marine ecologist and National Geographic explorer-in-residence, said in an email to China Dialogue that “COVID-19 has already changed the world, and everyone can realise that our relationship with nature is broken and that we have to fix it. This is why I hope that Kunming will change history not only by agreeing to ambitious targets for nature conservation, but also by establishing mechanisms to optimise and monitor conservation outcomes. We cannot make big announcements and promises without a real commitment to follow up.”

Kong Lingyu is a freelance writer covering environment and science. She was a journalist with Caixin Media and a project manager with Guangzhou Green Data Environmental Service Center, a non-governmental organization in China.

This article appears courtesy of China Dialogue Ocean and may be found in its original form here.

from Storage Containers https://maritime-executive.com/article/op-ed-protecting-30-percent-of-the-ocean-is-easier-said-than-done via http://www.rssmix.com/

0 notes