#charles x

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

the grandchildren of louis XV through his son, the dauphin

#historyedit#perioddramaedit#18th century#19th century#louis xvi#louis xviii#charles x#madame elisabeth#madame clotilde#ngl i did sob a little bit making these#there's just something heartbreaking about artois and provence ending up where they ended up because who would have thought?#mine#*

182 notes

·

View notes

Text

A set of porcelain dishes with images of the French Royal family on it, made in 1778-1779.

The coffee pot has an image of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette.

The milk jug shows the Comte and Comtesse de Provence.

The sugar pot depicts the Comte and Comtesse d'Artois.

The cups portray 3 princesses: Madame Louise, Madame Clotilde, and Madame Elisabeth.

Source

#marie antoinette#louis xvi#comtesse d'artois#charles x#louis xviii#madame louise#madame clotilde#madame elisabeth#chateau de versailles#marie josephine of savoy#maria theresa of savoy#long live the queue

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reflection Post on Marie-Thérèse

I am not as well-versed in the subject of Marie-Thérèse of France as I am in other topics, as I have only encountered a few serious historians on the matter. My study of her has mainly been through the lens of André Castelot and Waresquiel (although I never had the chance to finish Hélène Becquet’s biography of Marie-Thérèse, having unfortunately lost the book). Furthermore, at some point, I will talk more about historical events than about Marie-Thérèse herself.

The more I read about her, the more I find myself torn between two feelings: compassion for whatshe went through as a child and a sense of contempt for her ultra-royalist views. She didn’t listen to her uncle, Louis XVIII, who, on the whole, was the wisest in the family, even though she remained loyal to him all her life. Instead, she leaned toward the political views of her other uncle, Charles X (who was a fool during his reign, trying to turn back French ideals without learning from the failures of Louis XVI). Some have claimed that, because Marie-Thérèse had a difficult character that her mother, MarieAntoinette, tried to correct, her flaws only worsened after she endured her trials. Personally, I don’t believe this. Let’s not forget that when she threw tantrums as a child, she was probably just testing her limits, like any other child (although I have no doubt that her parents and aunt taught her that absolute monarchy was the best system). In short, she witnessed the execution of her parents and her aunt (though let’s be honest, Louis XVI was solely responsible for his own demise, betraying the nation in his attempt to restore absolute monarchy. He accepted war, knowing that the soldiers had little chance of survival, allowed his wife to correspond with the enemy despite the little she knew, and, at the very least, we are dealing with a case of massive involuntary manslaughter. Even in the 21st century, a leader could be condemned to death for what Louis XVI did). Furthermore, as much as Marie-Antoinette was made a scapegoat for many of the regime’s ills, and Elisabeth too, I find it hard to sympathize with them, although I was against theirs executions with so little evidence. Regardless of what can be reproached to them, nothing could have been worse than what happened. She saw her brother forcibly separated from her, her mother, and her aunt (and on this point, I sympathize—there should never have been such a forced separation, regardless of how guilty her mother and aunt were), and he died not long after. Therefore, I believe that Marie-Thérèse of France, no matter how right the revolutionary government may have been and how wrong her family’s actions were, had the right to bear no grudge against them, especially since she was the only one in her family—along with her brother— who wasn’t guilty. She suffered simply because she was born into the wrong family, which loved her dearly, despite everything. In fact, I don’t fault her for having ultra-royalist views, because, first of all, everyone has the right to hold different political opinions, and second, as I’ve mentioned, she suffered from a young age, in a time when therapists didn’t exist. So imagine the damage… It is especially when she returned to France that I feel compelled to make some criticisms.

Of course, she wasn’t at the head of the Kingdom of France and didn’t make the decisions, but let’s not forget two things: she was on track to become the next queen consort (since she married LouisAntoine de Bourbon), and she approved of ultra-royalist ideas. First, when Louis XVIII returned to the throne for the second and final time, facing Bonaparte, Marie-Thérèse naturally wanted to erase all traces of Napoleon. This seems understandable, as a new regime was being established, and it needed to be clear that Bonaparte’s reign was over. Here’s an excerpt from André Castelot’s book: "All the walls of the palace, the furniture, the hardware, the lamps, are covered in imperial crowns and the cursed 'N'. Eagles soar on the ceiling, bees flutter on the draperies, and the carpets are covered with violets. Efforts were made with fervor to hunt down the bees, to turn the eagles into swans, and to change the 'N' into two 'L's back to back. But the task was considerable! The Count of Artois found that nothing was progressing. Urged by Madame, he came to complain bitterly to his brother, who shrugged. Had he not promised to pardon even the symbolic violets of the Empire?"

Now, here are two things that struck me. At a time when the situation in France was catastrophic, with foreign powers demanding terrifying compensation, not to mention the issues of the White Terror and the loss of territories, she advised (although Artois would have done this with or without her) focusing on real estate, rather than advising him to deal with much more urgent matters. Moreover, I feel like these works cost quite a bit of money, particularly in silverware. Again, this is in poor taste when considering the state of France’s finances.

She would quickly oppose, as I mentioned earlier, the fact that Louis XVIII was a bit more flexible than they were, although she should have listened to him. Nevertheless, it’s important to note that she deserves credit for remaining loyal to him.

This ultra-royalism that Marie-Thérèse supported would do a lot of harm to France. To begin with, it veered into mysticism, with some ridiculous aspects, such as the Thomas Martin case. This peasant, convinced that an archangel had sent him to the king to ask for a counter-revolutionary crusade, was even received by Louis XVIII. While the right (some insincerely) claimed that they were right, the left considered him a victim of hallucinations. The ultras, faced with what they saw as revolutionary individualism, advocated for a society based on divine right, where man has no rights but only duties toward God. There was a rejection of the concepts of liberty and equality, claiming that man would be happier accepting the place God had for him, rather than attempting to transform the world.

It goes without saying why this idea was a catastrophe.

Finally, the assassination of the Duke of Berry, made a martyr (who had been a worldly and libertine figure previously looked down upon by the ultras), ensured that the ultras succeeded in pushing out the liberal minister Decazes, leading to an even harsher regime. As a result, figures like Lafayette found themselves at the head of movements like the Carbonari, composed of Bonapartist nostalgics, republicans, and royalists loyal to Decazes. In 1820, the “French Bazaar” plot, aimed at a coup, was discovered and suppressed with moderation. Other uprisings were planned, particularly in the West. In 1822, there was the affair of the four sergeants of La Rochelle: these noncommissioned officers, accused of conspiring against the regime, were arrested and sentenced to death despite the lack of concrete acts (they had only had discussions about their opposition). Their execution turned them into martyrs for the liberal-royalist opposition, republicans, and Bonapartists.

Once again, Marie-Thérèse is clearly not the person responsible for this fiasco, and I don’t believe she wanted the death of these four sergeants. It wasn’t her who led France, and she wasn’t the minister. However, the fact that she supported this ultra-royalism, despite seeing the damage it was causing, shows that she didn’t realize ( or didn’t want to see) the the dangers of ultra politics.

It seems that she approved of the coronation ceremony of Charles X in Reims, which cost a vast sum of money—an imprudent reminder of the time of absolute monarchy and a justified anger from Parisians. There was even a law that Charles X enacted which pleased the ultras: the death penalty for sacrilege, which caused an outcry. Although this law was not adopted, the dangers of such a measure were clear. Another law was the one on the billion, compensating émigrés who had lost their properties sold as national goods during the revolution. Again, not only was this not a priority for rebuilding the country, but it also showed a condemnation of the revolution. Furthermore, this decision ultimately angered even the most meticulous ultras who simply wanted the restitution of their properties. The amount paid didn’t reach the billion, which might have frustrated the recipients, but it was still significant enough to further irritate the opposition.

Honestly, even some of the successes achieved by the minister Villele (who, although more reactionary than Decazes and detesting liberalism, didn’t want to strengthen the position of the ultras) under Charles X don’t make me want to praise him, especially regarding Haiti. Charles X would have liked to, but he knew it wasn’t possible to reconquer Haiti. He would, therefore, force this new country, under the threat of war (which Haiti knew must be avoided), to pay France 150 million gold francs as compensation. It wasn’t until the 20th century that this debt was paid, showing the financial difficulties Haiti had to face. This is dishonest, because if we look at the facts, it was really France that should have compensated Haiti, given the harm they had done, especially when Bonaparte attempted to restore slavery, as you can see in this post:https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/758502228409614336/here-we-come-about-a-shocking-act-by-french-army?source=share .

Then, Charles X would go even further into ultra-royalism by appointing Polignac. Upon taking office, Polignac’s government, seen as ultra-royalist, sparked strong liberal opposition. Polignac, though aware of the limitations of his actions, struggled to align his policy with the Constitutional Charter, leading to conflicts with the Chamber of Deputies. In March 1830, an address passed by 221 deputies clearly manifested their opposition to the king, who responded by dissolving the Chamber and organizing new elections. However, despite dubious maneuvers to influence the results, the liberals won an even greater victory, deepening the political crisis. Meanwhile, the economic situation worsened: a banking crisis, poor harvests, and rising unemployment weakened the population, while social and generational tensions heightened.

The frustrations of students, workers, and peasants fueled a climate of unrest conducive to revolt. Faced with this growing opposition, Charles X attempted a power grab in July 1830, imposing ordinances to dissolve the Chamber, strictly control the press, and reform the electoral system to favor the aristocracy. These measures provoked an immediate reaction: the press called for resistance, workers and students rose up, and barricades multiplied in Paris.

The incompetence of the government and the absence of military reinforcements (which shows Charles X’s narrowmindedness since his best fighters were sent to Algeria,Charles having waged this war of conquest in order to distract people from real political problems ) facilitated the insurgents’ victory, and they took control of the capital on July 29. Faced with this insurrection, Charles X withdrew his ordinances and attempted a government reshuffle, but it was already too late. On July 30, his regime was condemned, paving the way for a dynastic change and the July Monarchy.

What about Marie-Thérèse? She didn’t hesitate to support the ultra-royalism advocated by Charles X, against all common sense. She let her personal grudges take precedence over the good of France and its people, to whom she was destined to be queen consort. As I said earlier, her convictions could have been forgiven if she had chosen not to get involved in politics. But the moment she decided to participate, whether directly or indirectly, since she held the position of first lady of the court, she had the responsibility not to act on her grudges and to push aside her overly reactionary ideas for the good of her country and its people. Many people suffered as much as, if not more than, she did during the French Revolution, and they decided to fulfill what they considered their duty for the good of their country.

There are even leaders in history who suffered before being crowned and later worked with people who had directly or indirectly harmed them personally.

Yet they adopted the right attitude, surely they despised them in public, but they set aside their grudges for the good of their countries, which was the essential thing to do (although, to be fair, the monarchs I have in mind didn’t face cases of regicide themselves and were horrified by it, and were called to obey the sovereignty, even though Elizabeth I did ultimately have Mary Stuart executed after much hesitation—though that’s a complex story).

Marie-Thérèse didn’t do that. Yes, she was charitable, loyal and very courageous, but that’s not enough when you see that she supported policies that wasted money for nothing. Severe, atrocious measures came from those who supported the ultra-royalism she backed, and she saw how this affected grieving families (especially with the case of the four sergeants of La Rochelle), but she was too rigid to change her attitude, disconnected from reality, and stubborn.

In the end, she and her husband, Louis XIX, could only be king and queen for 20 minutes because they were too tied to ultra-royalism, which ended up being the best thing. We can only understand the general indifference when Charles X, his son, and Marie-Thérèse left once again.

However, far from me the idea that this woman was a bloodthirsty person—that’s not true. But it would be a good idea if one day there were a historically accurate series from 1789 to 1848 (without demonizing the government of Year II or over-glorifying Bonaparte, as we see nowadays). It would be so interesting to follow Marie-Thérèse’s journey from a joyful child to a sad teenager due to all the misfortunes she endured, and then to a stubborn ultra-royalist woman. That would be fascinating.

P.S. After some hesitation, I didn’t mention how the regicides who rallied to Bonaparte were exiled and suffered from that exile, as one might argue it was a necessary repression since they supported Bonaparte, who had ousted Louis XVIII from the throne. For the same reasons, I didn’t include the story of the so-called repression of the patriots in 1816. Sources :

Hélène Becquet

André Castelot

Antoine Resche

P.S : To see the complexity of the political scale (there is a short excerpt on the Restoration period here: https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/758891467906465792/mini-history-on-a-short-period-concerning?source=share)

#history#france#frev#french revolution#restauration#of the bourbons#marie therese charlotte#reflexions#ultra royalism#Charles X#louis xviii

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

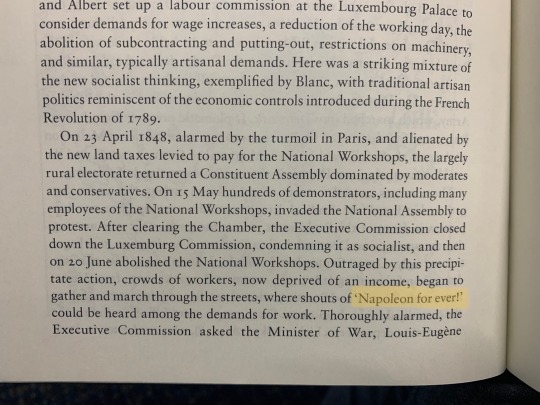

Napoleon as a rallying cry during the revolutions in France during the 19th century

July Revolution (French Revolution of 1830):

French Revolution of 1848:

Source: The Pursuit of Power: Europe 1815-1914, Richard J. Evans

#The Pursuit of Power#Richard J. Evans#Evans#Napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#Talleyrand#Charles X#Thiers#Marmont#Lafitte#Jacques Lafitte#Louis-Philippe#Lafayette#Revolution#french revolution#July Revolution#1848 revolutions#Revolution of 1848#1848#napoleonic era#Blanc#first french empire#napoleonic#history#french history#my pics#book#book quotes#revolution of 1830#France

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Charles X (1757–1836), King of France, after Gérard

Artist: Henry Bone (British, 1755-1834)

Date: 1829

Medium: Enamel

Collection: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, United States

Charles X, King of France

Charles X (Charles Philippe; 9 October 1757 – 6 November 1836) was King of France from 16 September 1824 until 2 August 1830. An uncle of the uncrowned Louis XVII and younger brother of reigning kings Louis XVI and Louis XVIII, he supported the latter in exile. After the Bourbon Restoration in 1814, Charles (as heir-presumptive) became the leader of the ultra-royalists, a radical monarchist faction within the French court that affirmed absolute monarchy by divine right and opposed the constitutional monarchy concessions towards liberals and the guarantees of civil liberties granted by the Charter of 1814. Charles gained influence within the French court after the assassination of his son Charles Ferdinand, Duke of Berry, in 1820 and succeeded his brother Louis XVIII in 1824.

#portrait#charles x#king#french king#standing#royal robes#indoors#classic architecture#full length#drapes#hat#table#cushion#british art#european art#french culture#french monarchy#french history#19th century painting#enamel#painting#artwork#fine art#metropolitan museum of art

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

CHARLES X OF FRANCE

CHARLES X OF FRANCE

9 October 1757 – 6 November 1836

King Charles X of France was the younger brother of Louis XVI. He was born at the Palace of Versailles, whilst his grandfather was king. His brother Louis married Marie Antoinette and later became king.

In 1773, Charles married Marie Therese and had five children. Charles was considered the most attractive member of his family, his wife Marie was considered ugly, and she was known for having many affairs. Charles was on good terms with Louis and Marie Antoinette. After the storming of the Bastille, Charles, his wife and children left France and fled to Savoy, where his wife was born. His brother Louis and Marie Antoinette were both executed during the French Revolution in 1793. Louis’s son and heir was tortured and died of neglect. Charles moved to England, where George III looked after him. Charles’ older brother Louis XVIII was named king of France. Charles’s son Louis Antoine married Marie Therese in 1799, she was the daughter of his brother and Marie Antoinette.

Louis XVIII moved to England and was now in a wheelchair. The Allies captured Paris a week after Napoleon abdicated and Louis XVIII was restored as king. Louis Antoine and Marie Therese returned to France and stayed in the Tuileries Palace, on arrival Marie Therese fainted because that is where she and her family where imprisoned before her family were killed, she was the only survivor. Louis XVIII died in 1824, and Charles X became king. He ruled for 6 years from 1824 – 1830 until the July Revolution of 1830, which resulted in his abdication in favour of his grandson Henry. Charles went into exile to England and then to Austria.

Charles died in Gorizia, in the Austrian Empire. He was the last of the French rulers from the House of Bourbon who were descended from King Henry IV.

#CharlesX #CharlesXofFrance #LouisXVI #marieantoinette #frenchrevolution #napoleon

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Richard III and The July Revolution

When I finally saw the Ian McKellan Richard III film I was a bit disappointed, his performance was great and there were interesting ideas to come from the concept of adapting this play to the 1930s. But those ideas weren’t explored fully and the other performances were kinda dull.

But my biggest pet peeve was removing Margaret of Anjou, now her presence in this play is it’s most explicit historical inaccuracy, the historical Margaret was not in England anymore during any of this time period, but an adaptation that removes it from even the pretense of being about actual history doesn’t need to worry about that. As a story, her functioning as a Prophetess of Doom is a lot of why this play works and is why I’m glad the first version of it I ever watched was The Hollow Crown series where she’s played by Sophi Okonedo.

Thinking about the idea of adapting this play to other time periods got me to thinking as a part-time Francophile about the idea of using it as a framing device for a fictionalization of the July Revolution of 1830.

Charles X of France and this popular view of Richard III have in common being the youngest of three brothers who was more of a blatant tyrant then his older brothers and the end of his Dynasty overthrown in a Revolution that could also be viewed as more of a Coup.

Charles was also rumored to have had an extramarital affair with Marie Antionette. Meanwhile he never married a daughter of Marie Antionette but his son did.

Orleans would thus fill the role of Richmond and everyone’s favorite crossover plot-line between the American and French Revolution the Marquis de Lafayette can fill the role of Lord Stanley crowning the new King at the end.

But here’s where specifically my Shadowmen interests come into play. The quasi Prophetess role of Margaret of Anjou can be filled by Josephine Balsamo the Countess of Cagliostro. As a daughter of Josephine she too has a connection to a recently overthrown dynasty.

#Josephine Balsamo#Countess Cagliostro#Margaret of Anjou#Richard III#July Revolution#July Monarchy#Charles X#Francophile#Olreanist#Marie Antionette

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

My incredible drawing of "the Virgin Mary holding baby Polignac and her AK47"

this is a private joke about french politician Jules de Polignac ignoring the literal french revolution in Paris's streets back in 1830, and saying to king Charles Xth "the virgin mary told me not to worry", which became a running gag. and don't worry to much about the ak47. with @justanothergaynerd <3

#artists on tumblr#art#drawing#illustration#doodles#sketches#my art#charles x#polignac#history#historical memes#historical meme

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Louis Philippe I vs Charles X (It's King vs King.) During the July Revolution.

This is a revolution between Kings. First one is Louis Philippe I, and the Second one i is Charles X. The fight between the Kings of France.

#kingdom of france#July Revolution#July monarchy#Bourbon restoration#Charles X#Louis Philippe I#Revolutions of 1830#History#Historical#King#Kings

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#delusional til i die#x reader#star wars x reader#anakin skywalker x reader#anakin skywalker#tom riddle#slytherin boys x reader#formula 1#f1 x reader#leon kennedy x reader#the vampire diaries#the originals#max verstappen x reader#spencer reid x reader#klaus mikaelson x reader#genshin impact#genshin impact x reader#harry potter#harry potter x reader#fanfic#fan fiction#charles leclerc#lando norris#kpop#dean winchester x reader#sam winchester x reader#anime#naruto#gojo satoru x reader#jujutsu kaisen

83K notes

·

View notes

Text

Bee Movie (2007) dir. Simon J. Smith & Steve Hickner X-Men: First Class (2011) dir. Matthew Vaughn

#bee movie#x men first class#xmenedit#beemovieedit#jerry seinfeld#charles xavier#erik lehnsherr#marveledit#filmedit#filmgifs#doyouevenfilm#fyeahmovies#moviegifs#cinemapix#dailyflicks#chewieblog#userelysia#userrobin#userrlaura#usergal#userel#mikaeled#useraurore#userallisyn#userfilm#usersugar#userclayy#kane52630#gifs#movie

47K notes

·

View notes

Text

I commend to God my wife and my children, my sister, my aunts, my brothers, and all those who are attached to me by ties of blood, or by any other manner whatsoever. I pray God especially to cast the eyes of his mercy on my wife, my children, and my sister, who have suffered so long with me; to support them by his grace if they lose me, and for as long as they remain in this perishable world.

#louis xvi#marie antoinette#marie therese charlotte#louis xvii#madame elisabeth#madame victoire#madame adelaide#louis xviii#charles x#house of bourbon#french monarchy#long live the queue

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

Post on a Short Period Concerning Political Spectrums from 1789 to 1848 to Counter Misconceptions About the Far Left and Far Right

Sociétés des Jacobins (Jacobin Societies)

We all know the famous phrase: “The far right and the far left are the same thing; they’re no better, etc.” However, the far right and the far left are clearly not the same. This definition should not be taken literally, as it pertains more to the Restoration period concerning property rights (and even then, it’s more complex). The far right believes that property should belong to the traditional elites (the emigrated nobility), while the far left has a different view like sharing the property for maximum people . And first, on which political spectrum are we basing this? From which period?

In 1789, those considered far left were deputies like Pétion, François Buzot, and Maximilien Robespierre. Non-deputies aligned with the far left included figures like Danton, Camille Desmoulins, and Manon Roland, among many others.

However, during the second revolution in 1792, these figures would split. What came to be known as the Girondins (though there were many differences within this group) would constitute the more conservative wing (including Buzot, Pétion, and Manon Roland), while the Montagnards represented the far left. Yet, on the issue of slavery, many from both sides agreed on its abolition: Brissot proposed a gradual abolition, Sonthonax was sent to Saint-Domingue to enforce it, and Abbé Raynal (though seemingly conservative on property rights) was highly reformist on slavery, even calling Toussaint Louverture the “Black Spartacus.” The Montagnards, like Danton and Jean-Paul Marat (who supported the Haitian revolt and predicted its independence), joined in this cause, as did the Hébertists like Pierre Gaspard Chaumette, who shared Marat's views on Haiti.

The first major division between the Girondins and the Montagnards was over the issue of war, and it’s clear that the Montagnards were ultimately proven right on these question. What we now call the far left of this period consisted of elements considered a faction called the Hébertists (including individuals like Momoro, Chaumette, Hébert, François Hanriot, Charles Philippe Ronsin, Vincent François Nicolas, etc.) and another group known as the Enragés (Jacques Roux, Théophile Leclerc, Jean-François Varlet, Pauline Léon, Claire Lacombe, etc.). These two factions were also called ultra-revolutionaries and were much more socially engaged on certain political issues than Montagnards like Robespierre, Desmoulins, Danton, etc.

During the insurrection from May 31, 1793, to June 2, 1793, in which the Paris Commune, led in part by François Hanriot (following the arrest of Hébert and the Sans-Culotte delegation demanding his release, along with Isnard’s speech and the Commission of Twelve), expelled 21 Girondins who were initially placed under house arrest (we all know what happened next, but that’s not the focus here). The Montagnards who approved this insurrection portrayed themselves as allies of the Sans-Culottes. However, it’s important to note that not many of them viewed this leftist faction favorably (Marat became an opponent of Jacques Roux, and after his death, his widow Simone Evrard gave a speech against Jacques Roux and Théophile Leclerc among others ). The Committee of Public Safety and the Convention illegally persecuted Jacques Roux to the point where he committed suicide, suggesting that the Montagnards were beginning to shift further to the right. Furthermore, there were internal conflicts within the far left. The Hébertists clashed with the Enragés and later took up their petitions after many of them were removed from the political scene.

Later, on September 5, 1793, as the French Revolution seemed more endangered than ever, the Commune, led by figures like Chaumette, Hanriot, and Pache, arrived at the Convention without opposition, securing concessions such as the maximum price controls and the raising of a revolutionary army. The Montagnards seemed ready once again to support this far left on some points. However, conflicts and internal struggles soon reemerged. This time, the Indulgents, including Camille Desmoulins, Georges Jacques Danton, and Pierre Philippeaux, formed the Montagnards’ right wing. Initially, the majority of the Convention supported them against the elements considered far left (notably Robespierre, among others), but the majority of the Committee of Public Safety eventually realized they had also underestimated the Indulgents and opted for a middle-ground policy. The struggles among these different factions further weakened the Montagnards. However, they all shared a common goal of celebrating the abolition of slavery. This wasn’t enough for reconciliation; most far-left elements (Pache and Hanriot were notably spared from the Hébertist arrests) were politically eliminated (and it’s important to note that Billaud-Varenne and Collot d’Herbois, who represented the far left of the Committee of Public Safety, participated in this elimination).

Regarding property rights, the entire political class was very timid, even the Enragés and Hébertists, who were more focused on economic issues like taxation. However, some like Momoro apparently began to consider land redistribution like sharing large farms, but without a clear plan (and far from any notion of collectivization of agriculture) . There was a concession made by the Convention on property rights with the Ventôse Laws, perhaps? Previously, when the property of someone convicted of being an enemy of the Republic was seized, it went directly to the state. With these laws, the property was supposed to be redistributed to the needy, perhaps even the property left by émigrés. This was rarely, if ever, implemented.

Later, the eliminations continued with the Indulgents, internal struggles persisted in Thermidor, and the left suffered its final blow following the repression of May 20, 1795.

Indeed, even before May 20, 1795, there was a rightward turn at the end of 1794. In 1795, economic liberalism exacerbated the situation of the popular classes, leading to the insurrection of 1st Prairial Year III. The repression provided an opportunity for the right to eliminate from the political scene people like Goujon and Charles Gilbert Romme, who were considered the last Montagnards.

During the Directory, new far-left elements emerged, the most well-known being the Babouvists. Gracchus Babeuf’s “Manifesto of the Equals” was seen as promoting equality. Nevertheless, while some consider Babeuf to be a precursor to communism and he did advocate for deep social change, his interest was limited to agricultural domains. Lazare Carnot, who led the repression of the Babouvists, was seen as belonging to the right political wing .

The most interesting case considered far left is the neo-Jacobin Bernard Metge. In his work “Dialogue between a Representative of the People and a Former Administrator,” he sharply criticizes the Council of Five Hundred for ignoring the opinions of citizens, yet he also delivers a violent critique of the Babouvists, arguing that their ideology would, in his own words, produce nothing but lazy people. He wrote to the Minister of Police from prison, where he was detained, saying, “Indeed, preach the sharing and equality of goods, and you will have lazy people.” Although a fierce opponent of Sieyès, he advocated political liberalism and supported the Constitution of Year III. However, in his writing that sealed his fate, “The Turk and the French Soldier,” we see another side of Metge: he could be interpreted as opposing expansionist and conquest wars, notably by defending the Egyptians, but also as glorifying the right to resist. He also glorifies Brutus.

When he was arrested and executed by the Bonaparte regime (then the First Consul) for his opinions, he was considered one of the 34 anarchist leaders by the Brumaire regime. On this political spectrum, he was seen as a far-left figure, while on another spectrum, like in 1794 or around 1848, he would likely have been considered a right-wing figure. Metge was executed in a parody of justice. For more details on this revolutionary, visit this Tumblr post: https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/756533326215528448/the-jacobins-executed-by-bonaparte.

The most interesting example from this period is Lazare Carnot. Initially a Montagnard in 1793 when he was on the Committee of Public Safety, during the Directory, he took an increasingly right-wing position, including the repression of the Babouvists, where even Barras hesitated. He was certainly the Minister of War under Bonaparte, but in a sense, he found himself once again on the far left of the political spectrum under Bonaparte’s Consulate (a deliberate provocation on my part to better highlight the complexity of different periods on the political spectrum) because he was in the official opposition (after all, the rest of the opposition was either silenced, imprisoned, or deported, like Félix Lepeletier, etc.). He was marginalized for opposing the creation of the Empire.

Then we have the case of the Restoration with the “Chambre introuvable” appointed by Louis XVIII, long considered a chamber more royalist than the King (including figures like Louis de Bonald). Some analyses tend to moderate this; while it’s true there were émigrés from the nobility, the bourgeoisie aspiring to be ennobled, turncoats, and provincial notables, it’s also true that ultra-royalists like Charles X influenced it, making it far more right-wing politically than any other period. Decazes and, more importantly, François Guizot stood up to the ultra-royalists and advised dissolving the Chamber.

Chambre introuvable

Constitutionalists (39) Color to the left Ultraroyalists (350) Even if we have to give more thought to the ultra-royalist side

Yet, under Louis Philippe I’s political spectrum, Guizot was one of the most conservative figures. He was the staunchest defender of conservative and right-wing policies.

François Guizot (1787-1874) painted by Jean-Georges Vibert after a portrait by Paul Delaroche.

Through all these examples, I wanted to caution against the misconception that far left equals far right. History has shown the opposite through the examples cited above, demonstrating that the economic or property-related views of the far left and far right are not the same at all. Individuals situated on the far left can shift to the most conservative right-wing positions depending on the political spectrum of the period, and vice versa, without necessarily changing their political ideas.

Sources:

Antoine Resche

Jean Marc Schiappa

Jean Clément Martin

Bernard Gainot

#frev#french revolution#napoleonic era#louis xviii#Charles X#Monarchy#political spectrum#convention#constitutional monarchy

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

the world needs to see this tweet

56K notes

·

View notes

Text

Portrait of Charles X

Artist: Horace Vernet (French, 1789–1863)

Charles X King of France

Charles X (Charles Philippe; 9 October 1757 – 6 November 1836) was King of France from 16 September 1824 until 2 August 1830. An uncle of the uncrowned Louis XVII and younger brother of reigning kings Louis XVI and Louis XVIII, he supported the latter in exile.

#portrait#charles x#french monarch#french#european#Horace vernet#french painter#man#uniform#king#french royalty6

2 notes

·

View notes