#ceratopsian month 2017

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

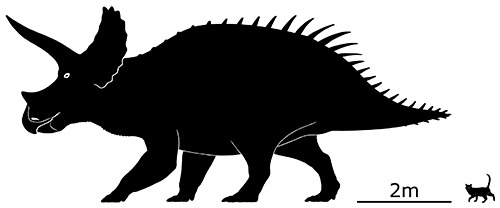

Ceratopsian Month #20 -- Styracosaurus albertensis

The last centrosaur for this month is one of the most distinctive and recognizable of all ceratopsians -- the elaborate Styracosaurus (“spiked lizard”).

Known from Alberta, Canada, about 75 million years ago, it was part of the Centrosaurini branch of the centrosaur evolutionary tree, closely related to both Centrosaurus and Coronosaurus. Many fossils have been found in several different bonebeds, including some nearly complete skeletons with body lengths of around 5.5m (18′).

There was a lot of variation in the frill ornamentaion between different Styracosaurus individuals. They could have either two or three pairs of very long spikes at least 50cm long (19″), along with various smaller hooks, knobs, or tab-shaped projections.

The long nose horn was also very variable between specimens, with some pointing slightly backwards, some being straight, and others pointing forwards. Juveniles are known to have had small pointed brow horns which became even more reduced in adults.

Tomorrow we’re moving on to the chasmosaurs, so here’s the centrosaur evolutionary tree:

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#ceratopsian month 2017#styracosaurus#centrosaurini#centrosaurinae#ceratopsidae#neoceratopsia#ceratopsian#marginocephalia#neornithischia#ornithischia#dinosaur#archosaur#art#speculative fluffiness#feather ALL the dinosaurs#who wanted manes beards and mustaches? because here you go :D#also All The Quills#maximum spikiness

497 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Science of Jurassic Park & More: Part Two

Today we are incredibly excited to be continuing our deep-dive into the world of palaeontology with Doctor David Button from London’s Natural History Museum.

In Part One, David tackled questions such as feathers on dinosaurs, the pose-ability of Sauropod’s necks, and much more. If you missed it, click here to take a read.

All images in the article ahead are also courtesy of our friends at Jurassic Vault – so go show them some love if you haven’t already!

We’re excited to dive into today’s part – where we will kick off by talking about new dinosaur species!

Any dinos we don’t know about yet?

Yep: many new dinosaur species are still being discovered every year, and this shows no signs of stopping anytime soon. Some of these are very unusual – for example the ‘batwing’ dinosaurus Yi and Ambopteryx have only been discovered in the past couple of years. So, amazing things are undoubtedly still to be discovered.

What are the chances of finding another BIG carnivore or sauropod, like bigger than anything known right now?

Interestingly, recent years have seen the discovery of multiple species of very large sauropods – e.g. Dreadnoughtus in 2014, Notocolossus in 2016, and Patagotitan in 2017. Cretaceous fossil sites in South America are becoming increasingly well-known, and Cretaceous strata across Africa are also starting to be better explored. These are both times and places from which titanosaurs were particularly common, and so are the most likely places to yield both new exceptionally large sauropods, and massive theropods that may have fed on them. So, I reckon there is a good chance of finding more colossal dinosaurs in the future.

Were dinosaur’s adequate swimmers? Also, how long did young dinos stay in their "fledgling" stage with mother? Is there a way to tell?

The powerful legs of dinosaurs meant that most were probably competent swimmers. Evidence from oxygen isotopes, preserved gut contents and tooth marks indicates that spinosaurids mainly ate aquatic organisms and probably spent a lot of time in the water – indicating that they must have been able to swim well. The unusual dromaeosaurid Halszkaraptor, meanwhile, shows skeletal characteristics very similar to living aquatic birds, with powerful kicking legs, and short, flipper-like forelimbs. It also seems to have been semiaquatic in lifestyle.

An exception to this may be provided by the ceratopsians. Multiple large bone beds are known which preserve the remains of ceratopsian herds that drowned in flash floods. Hadrosaurs, meanwhile, were common in the same times and places, but do not occur in these death assemblages. Modelling of the centre of gravity shows that the heavy heads of ceratopsians would have pulled them forwards in the water, making it difficult for them to stay afloat. It hence seems that, during these events, hadrosaurs were able to easily swim to safety whereas many more ceratopsians struggled and drowned.

It is hard to tell how long dinosaur chicks stayed with their parents – or, in many cases, whether parental care was performed at all. Footprint evidence shows young dinosaurs associating with adults, but it is unclear whether these represent parents with their babies, or simply casual mixed-age associations. Furthermore, age segregated trackways are also known. Collections of footprints from a small number of differently-sized individuals – for example from rebbachisaurid sauropods – have been suggested to represent family groups, but this is similarly difficult to test. Similarly, although mixed-age associations of Psittacosaurus are known, it is unclear if they represent a parent or helper watching over a crèche or, more likely, simply young psittacosaurs joining together for safety in numbers.

Consequently, even though we know of cooperative behaviour in many dinosaurs, it is hard to distinguish whether genuine parental care from simple gregariousness. Even when we do have strong evidence of parental care in dinosaurs – such as in oviraptorosaurs – we unfortunately still have no real evidence as to how long that care may have lasted after hatching. Nevertheless, it seems plausible that many dinosaurs would have cared for their young for weeks or even months after hatching, like modern-day birds.

Is the Spinosaurus quadrupedal or bipedal?.. or is it still a great mystery within the palaeontology community?

Establishing exactly what Spinosaurus looked like is difficult, as we have so little fossil material of it to go on. Not only are only a small number of Spinosaurus skeletons known, but each is also highly incomplete. As a result, reconstructing a complete view of Spinosaurus requires comparison between the skeletons of different individuals, which can make figuring out accurate proportions difficult. Furthermore, it seems likely that some of the material referred to Spinosaurus actually belongs to a related genus, Sigilmassasaurus, posing even more problems for trying to extrapolate between them to get an overall picture of Spinosaurus.

With all those caveats, I hence think it is most likely that Spinosaurus was capable of bipedal locomotion �� like its relatives such as Baryonyx. However, it does still seem likely that its legs were at least relatively short, and so it would look different to its depiction in the Jurassic Park franchise. Still, greater certainty on how Spinosaurus looked and moved will need to wait for the discovery of more complete skeletons of the animal.

Was there any dinosaur media (film, cartoons, documentary, series) that influenced them to follow the path resulting in palaeontology?

Many of my colleagues list Jurassic Park as their single biggest influence in pursuing palaeontology. However, for me, the biggest influence was a magazine series – Dinosaurs! – published by Orbis in the ‘80s and ‘90s. It was very effective at presenting dinosaurs as animals that we could learn about, rather than as monsters, as well as the lines of thinking that allowed us to do so. Certainly, fondly remembered, and almost certainly my single biggest early childhood influence.

In your opinion, where is the line drawn between entertainment and reality? e.g. Would a chase scene in Jurassic Park be as entertaining to a cinema audience if the animal was paleo-accurate to current knowledge and theories.

I, obviously, would generally prefer it if films were as accurate as possible, simple as that is something I find satisfying and interesting. I was, for example, very disappointed by the lack of feathers in Jurassic World, not only because they would have been accurate but also, more importantly, it showed a lack of imagination on the film maker’s part. They could have made all sorts of cool, modern-looking dinosaurs, reaching deeper horror through mixing something we think we know – a bird – with something primordial and deadly. It would also have furthered one of the key threads of Jurassic Park itself.

However, that does not mean I necessarily expect films to be accurate – after all, their job is to sell movie tickets, not to educate. Films in general make continual errors regarding everything from computer science through basic human biology, and I think that audiences are aware of that. Jurassic Park holds up despite being scientifically dated because the movie is effectively using the dinosaurs as metaphors – both for arrogance and the power of nature – as opposed to being a documentary about them. Whereas I would expect a documentary film (e.g. the Walking with Dinosaurs movie) to be well-researched, a genre-film’s job is to relate a narrative, not present facts.

So, overall, I as a moviegoer would personally would prefer it is dinosaurs in films were accurate. However, I do not expect it, and certainly think the use of artistic licence to make the films more entertaining is entirely appropriate. After all, this is their job, not education. Indeed, if we are relying on blockbuster films to educate people about science, we have much bigger societal problems than public understanding of dinosaurs at hand.

How do you feel about Jurassic Park/Worlds speculation on soft tissue and threats? For example Dilophosaurus frill and venom, Troodon venom and nesting habits, and the T. rex "bad eye sight". Also re classification like Deinonychus = Velociraptor???

The ‘bad eyesight’ of Tyrannosaurus in the films actually annoys me, as the size of the orbit and the brain structure indicates that Tyrannosaurus would actually have had good eyesight (like modern birds). The “it cannot see you if you don’t move” thing never made any sense, as a large predator would not be able to function like that. Consequently, I am glad that the Jurassic Park franchise has moved away from that in more recent years, as it has produced a persistent belief about dinosaurs that is entirely inaccurate. Similarly, there is no evidence for venom or an extendable frill in Dilophosaurus (or any other dinosaurs). Consequently, these are best viewed as not so much soft tissue speculation as just making things up for cinematic sake.

That being said, I do appreciate the need for artistic licence in movies, and giving those animals those attributes certainly did help add tension, excitement and action to those scenes. I hence can understand why those features – especially in Dilophosaurus – are included, even though they are entirely fictitious. I am glad that the movies have since acknowledged that many of the cloned dinosaurs are very different to their real counterparts, as it helps balance the need for spectacle with an open admission that these attributes are entirely fictitious.

However, I must admit that I sort of draw the line at the nesting habits of Troodon. I can accept the venom as artistic licence, but the whole thing about it laying its eggs in bodies in Jurassic Park: The Game is so absurd and preposterous that I cannot even enjoy it. I get that they wanted a new level of threat and horror from a dinosaur, but it just makes no sense at any level – no large vertebrate would incubate its eggs in that way, as it would just be a recipe for infection and death of the chicks. I mean, what, were they supposed to have spliced its DNA with an ichneumon wasp or something? Why on Earth would they have done that?!

The Deinonychus were reclassified as Velociraptor in Jurassic Park partially due to the arguments of Greg Paul, who generally supports lumping many dinosaur species together. However, this view is not backed by any other palaeontologist, and so I would rather it was not used and the dinosaurs were correctly classified. However, I acknowledge that the other half of the argument - that “Velociraptor just sounds cooler” – means that this will never happen in the Jurassic Park franchise.

And fave dino?

It is hard to say, but my favourite dinosaur may be the prosauropod Plateosaurus. This is for a couple of reasons: firstly, a lot of my PhD research was on this animal; and secondly, I just like prosauropods. They seem like they would have been rather incompetent, unintelligent, cumbersome, bulky, reeking, omnivorous, foul-tempered animals, and something about that appeals to me. I am also fond of sauropods – particularly Camarasaurus, as a lot of my PhD research also concerned that animal.

Other favourite dinosaurs include the ornithischian Thescelosaurus (again, this is helped by me having worked closely on it) and hadrosaurs such as Corythosaurus. I also like rebbachisaurid sauropods such as Nigersaurus.

That draws a close to part two of our “The Science of Jurassic Park & More” series. Make sure to join us next week for our third and final installment.

For now, make sure to follow him on Twitter if you aren’t already, and stay tuned to The Jurassic Park Podcast for all the latest Jurassic Park news!

Written by: Tom Fishenden

#article#doctor david button#david button#paleontologist#paleontology#ask a palaeontologist#ask a paleontologist#natural history museum london#tom jurassic#tom fishenden

0 notes

Photo

Ceratopsian Month #31 -- Triceratops horridus

Of course we’re ending this month with the most famous of the ceratopsians, the dinosaur superstar Triceratops (“three-horned face”).

Dating to the very end of the Cretaceous, between 68 and 66 million years ago, it was the most common ceratopsid in North America at the time, ranging from Alberta, Canada down to Colorado, USA. Two different species are currently recognized within the genus -- T. horridus in the older part of that time range, and T. prorsus in the younger rock layers.

It was one of the very largest ceratopsians, with the biggest individuals reaching sizes of about 7.9-9m (26’-29’6”). Many fossil remains have been found, representing growth stages from juveniles to adults (with Torosaurus speculated to represent the most fully mature individuals), and a lot of variation in exact horn and frill shape is seen between different skulls. One specimen nicknamed “Yoshi’s trike” had some of the longest brow horns of any ceratopsid, with the bony cores alone measuring 1.15m long (3′9″).

Unusually for a chasmosaur, it had a very short and solid frill with no weight-reducing holes, suggesting the structure served a much more defensive role than in other ceratopsids. Damage to the frill bones in some specimens appears to have been caused by other Triceratops, giving support to the popular depiction of these dinosaurs locking horns in fights.

Tooth-marks from the equally-famous Tyrannosaurus have also been found on Triceratops bones. Not all of these predator-prey encounters were fatal, however, with some specimens showing evidence of healing around the damaged areas.

Fossilized skin impressions show that Triceratops was scaly -- but with scales unlike those of any other known dinosaur, showing large polygonal scales interspersed with even bigger knobbly scales with odd “nipple-shaped” conical projections in their centers. It’s possible that the “nipples” may have supported larger structures (as I’ve illustrated above), but unfortunately no official scientific description of this skin has been published yet and details about it are vague.

And with this final entry, here’s the chasmosaur evolutionary tree:

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#ceratopsian month 2017#triceratops#triceratopsini#chasmosaurinae#ceratopsidae#neoceratopsia#ceratopsian#marginocephalia#neornithischia#ornithischia#dinosaur#archosaur#the 'toromorph' debate#art#have some actually scaly dinosaurs#triceratops' weird nipple-scales#go home evolution you're drunk

226 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ceratopsian Month #25 -- Pentaceratops sternbergii

Despite its name, Pentaceratops (“five-horned face”) only had three main facial horns just like most other ceratopsids. The extra two “horns” actually refer to the cheek spikes which protruded out sideways from its face -- a feature seen in all ceratopsids to some degree, but especially long and sharply pointed in Pentaceratops.

Living about 76-73 million years ago, its fossils are known from New Mexico and Colorado, USA. A possible second species, P. aquilonius, was discovered much farther north in Alberta, Canada, but this identification is somewhat dubious due to the remains being highly fragmentary.

Multiple specimens have been found, with a full body length of around 5-6m (16’4"-19’8”). One especially large specimen previously identified as Pentaceratops was nearly 7m long (23′), but has since been moved into its own separate genus Titanoceratops.

Pentaceratops’ frill was one of the largest of all known ceratopsids, similar in size and shape to that of its close relative Utahceratops, with a U-shaped top edge and a pair of forward-curving spikes.

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#ceratopsian month 2017#pentaceratops#chasmosaurini#chasmosaurinae#ceratopsidae#neoceratopsia#ceratopsian#marginocephalia#neornithischia#ornithischia#dinosaur#archosaur#art

228 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ceratopsian Month #14 -- Wendiceratops pinhornensis

Wendiceratops (“Wendy’s horned face”) was one of the older known centrosaurs, living about 79 million years ago in Alberta, Canada -- but it had a slightly higher position in the evolutionary tree than more basal forms like Xenoceratops, indicating just how incredibly quickly the early ceratopsids diversified.

Partial remains of several individuals have been found, representing both adults and juveniles, with an estimated full size of around 6m long (19′8″).

It had forward-curving frill spikes, similar to those of its close relative Sinoceratops, and a large nose horn. The size of its brow horns are unknown, so the ones seen in this reconstruction are based on the fairly well-developed horns of other similarly-aged centrosaurs.

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#ceratopsian month 2017#wendiceratops#centrosaurinae#ceratopsidae#neoceratopsia#ceratopsian#marginocephalia#neornithischia#ornithischia#dinosaur#archosaur#art

259 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ceratopsian Month #13 -- Sinoceratops zhuchengensis

Sinoceratops (“Chinese horned face”) was the first and only ceratopsid known from China, and possibly also the only one known from the entirety of Asia -- depending on whether Turanoceratops counts as a true ceratopsid or not.

Discovered in the Shandong province, it dates to about 73 million years ago and was one of the larger centrosaurs at an estimated length of at least 6m (19′8″).

It had a well-developed nose horn and highly reduced brow horns, and forward-curving spikes around the edge of its frill that gave it a crown-like appearance. Uniquely for a ceratopsid, it also had some protruding bumps just below the spikes, creating a second row of ornamentation.

The presence of Sinoceratops in China shows that at least one lineage of centrosaurs dispersed across to Asia in the Late Cretaceous, but they seem to have been quite rare animals on that side of Beringia. While other dinosaur groups such as hadrosaurs and tyrannosaurs seemed to do just fine on both continents, something prevented the ceratopsids from being nearly as prolific as their North American relatives.

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#ceratopsian month 2017#sinoceratops#centrosaurinae#ceratopsidae#neoceratopsia#ceratopsian#marginocephalia#neornithischia#ornithischia#dinosaur#archosaur#art

245 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ceratopsian Month #30 -- Torosaurus latus

Torosaurus (“perforated lizard”) was a particularly widespread member of the Triceratopsini, found across western North America. Fossils are known from Canada all the way down to New Mexico and Texas in the southern regions of the USA, although the southernmost specimens represent a second species within the genus, T. utahensis.

Living about 68-66 million years ago, it was one of the largest ceratopsids, reaching body lengths of around 7.5m (24’7"). The size and shape of its three horns varied between individuals, from short and straight to much longer and curving forwards.

It had one of the longest skulls of any known land animal, with some specimens’ heads measuring at least 2.5m long (8′2″). Around half of that length consisted solely of its frill, the shape of which was also quite variable -- some were very flat while others curved upwards, and the top edge could be either rounded, straight, or have a “heart-shaped” notch.

In 2010 a study was published by John Scannella and Jack Horner, hypothesizing that Torosaurus wasn’t a unique genus and was actually the fully mature form of Triceratops. While poor media reporting briefly sent the internet into a panic about Triceratops “never existing”, further studies by other paleontologists have failed to come up with the same results, and the debate doesn’t seem to have come to any overall consensus yet.

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#ceratopsian month 2017#torosaurus#triceratopsini#chasmosaurinae#ceratopsidae#neoceratopsia#ceratopsian#marginocephalia#neornithischia#ornithischia#dinosaur#archosaur#art#the 'toromorph' debate

143 notes

·

View notes

Photo

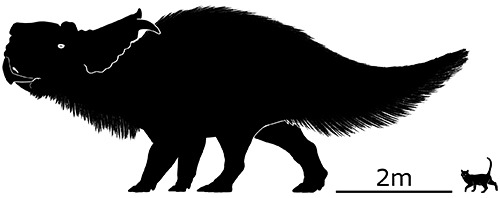

Ceratopsian Month #17 -- Pachyrhinosaurus canadensis

Pachyrhinosaurus (“thick-nosed lizard”) has become one of the more recognizable ceratopsian names in the last couple of decades, but its remains have actually been known for over 70 years, first discovered in the mid-1940s.

Three different species have been named within the genus, all living about 74-69 million years ago in Alberta, Canada, and Alaska, USA. The type species P. canadensis dates to roughly the middle of that time span, at an age of around 71 million years.

It was one of the largest of the centrosaurs, with the biggest specimens estimated to have measured up to 8m long (26′). Thousands of fossils have been found in a bone bed that seems to represent a mass mortality event -- possibly a herd caught in a flash flood -- with ages ranging from juveniles to adults.

Rather than horns, Pachyrhinosaurus had huge flattened bosses on its skull, which nearly grew together into a single large mass in both P. canandensis and the younger species P. perotorum. The older species P. lakustai instead had more separated bosses and a “unicorn horn” on its forehead.

(I’m also hardly the first person to speculate about fluffy pachyrhinosaurs, but since they lived in a chilly Arctic environment it’s certainly an interesting possibility.)

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#ceratopsian month 2017#pachyrhinosaurus#pachyrhinosaurini#centrosaurinae#ceratopsidae#neoceratopsia#ceratopsian#marginocephalia#neornithischia#ornithischia#dinosaur#archosaur#art#speculative fluffiness#feather ALL the dinosaurs

219 notes

·

View notes

Photo

At this point in ceratopsian evolution we’ve reached the ceratopsids -- the big, elaborately horned and frilled group that includes famous names like Triceratops and Styracosaurus. First evolving from their smaller North American ancestors around 90-80 million years ago, these dinosaurs rapidly diversified and developed a huge variety of different head ornamentations during the last 20 million years or so of the Cretaceous.

Here the family tree gets a little more complicated, with two major subdivisions of the ceratopsids splitting off from a common ancestor: the centrosaurs and the chasmosaurs. We’ll be focusing on the centrosaurs to start off, and moving on to chasmosaurs later in the month.

Ceratopsian Month #09 -- Diabloceratops eatoni

The centrosaurs are known mainly from the northern region of western North America (Alaska, Alberta, and Montana) -- although a few ranged further south with remains found as far away as Mexico, and one even made it into Asia. They often had prominent spikes on their frills, and many also developed large nose horns or nasal bosses.

Diabloceratops (“devil horned face”) was one of the earliest members of the group, dating to about 80 million years ago in the Late Cretaceous. Discovered in Utah, USA, it was probably around 5.5m long (18′), with a small nose horn, relatively short brow horns, and a pair of long “devil horn” spikes at the top of its frill that inspired its genus name.

Its skull was shorter and deeper than those of its later relatives, and retained a few “primitive” features from its ancestors. It was also the first centrosaur found further south than Montana, and with it being such a basal member it’s possible the group may have actually originated in the southern part of the continent with their descendants dispersing northwards.

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#ceratopsian month 2017#diabloceratops#centrosaurinae#ceratopsidae#neoceratopsia#ceratopsian#marginocephalia#neornithischia#ornithischia#dinosaur#archosaur#art#transitional forms

260 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ceratopsian Month #29 -- Regaliceratops peterhewsi

The Triceratopsini branch of the chasmosaurs first split off somewhere around 75 million years ago, with Titanoceratops being the earliest known member. But they don’t seem to have really diversified until several million years later, towards the very end of the Cretaceous 70-68 million years ago, around the time the centrosaurs had already mostly disappeared.

Regaliceratops (“royal horned face”) dates to about 68-67 million years ago, and is estimated to have measured around 5m long (16’4"). Known from a single near-complete skull discovered in Alberta, Canada, the fossil specimen was nicknamed “Hellboy” for both its stubby brow horns and the immense difficulty of removing it from the surrounding rock.

It had highly unusual ornamentation for a chasmosaur -- a long nose horn, short brow horns, and large crown-like spikes ringing its relatively short frill -- convergently resembling the sort of arrangement seen in many centrosaurs.

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#ceratopsian month 2017#regaliceratops#triceratopsini#chasmosaurinae#ceratopsidae#neoceratopsia#ceratopsian#marginocephalia#neornithischia#ornithischia#dinosaur#archosaur#art#convergent evolution#a triceratopsin trying to be a styracosaurus

141 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ceratopsian Month #24 -- Utahceratops gettyi

Utahceratops (“Utah horned face”) lived about 76-75 million years ago in Utah, USA. Partial remains of six different individuals have been found, allowing for about 95% of the skull and 70% of the rest of the skeleton to be accurately reconstructed -- giving a full body length of around 4.5m (14’9"), with the skull alone being over 2m long (6′6″).

Its nose horn was positioned quite far back on its snout, and its short blunt brow horns pointed out to the sides. The top of its long frill ended in a U-shaped notch, with the first pair of spikes curving forwards.

Despite how proportionally large the skulls of chasmosaurs like Utahceratops were, they weren’t nearly as heavy as they might look. Instead of being made of solid bone, there were large openings in the frill (known as fenestrae) that helped to significantly reduce its weight.

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#ceratopsian month 2017#utahceratops#chasmosaurini#chasmosaurinae#ceratopsidae#neoceratopsia#ceratopsian#marginocephalia#neornithischia#ornithischia#dinosaur#archosaur#art

156 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ceratopsian Month #12 -- Albertaceratops nesmoi

As its name suggests, Albertaceratops (“Alberta horned face”) was discovered in Alberta, Canada. Living around 77 million years ago, it’s known from an almost complete skull and would have had an estimated full body length of about 5.8m (19′).

It had fairly long brow horns and a boss-like nasal horn, similar to the arrangement in Xenoceratops, with a pair of large curving hook-shaped spikes at the top of its frill.

Some similar fossil remains found in Montana, USA, were attributed to Albertaceratops, but later studies showed that they actually belonged to a completely different ceratopsid -- a chasmosaur eventually named as Medusaceratops.

[2018 update: Medusaceratops wasn’t actually a chasmosaur, but a centrosaur closely related to Albertaceratops!]

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#ceratopsian month 2017#albertaceratops#centrosaurinae#ceratopsidae#neoceratopsia#ceratopsian#marginocephalia#neornithischia#ornithischia#dinosaur#archosaur#art#strawberryceratops

212 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ceratopsian Month #28 -- Vagaceratops irvinensis

Vagaceratops (“wandering horned face”) was originally thought to be a species of Chasmosaurus, but was separated out into its own genus in 2010 after new studies suggested it was much more closely related to Kosmoceratops.

Measuring around 5m long (16’4”), it lived about 75 million years ago in Alberta, Canada -- much farther north than its Utahn relative, inspiring its “wandering” genus name. It had a short nose horn, and brow horns reduced down to low bosses, along with a distinctive squared-off frill topped with a row of forward-curving spikes.

Ceratopsid forelimb posture has been a long-standing puzzle in paleontology. While the hindlimbs were clearly held straight under the body, the bones of the forelimbs are a lot more ambiguous, and various different arrangements have been proposed over the years from straight to heavily sprawled and lizard-like.

While the fully sprawled position mostly fell out of favor during the dinosaur renaissance, debate continued about whether ceratopsids had a fully straight forelimb posture or some sort of in-between arrangement with the elbows slightly bent out to the sides. In 2007, digital scans of Vagaceratops’ forelimb bones were used to model how it could have walked, suggesting the best fit was in fact the intermediate position.

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#ceratopsian month 2017#vagaceratops#chasmosaurini#chasmosaurinae#ceratopsidae#neoceratopsia#ceratopsian#marginocephalia#neornithischia#ornithischia#dinosaur#archosaur#art#speculative fluffiness#feather ALL the dinosaurs

127 notes

·

View notes

Photo

It’s time for another month of themed blog posts, and this August features one of the most iconic groups of dinosaurs: the “horn-faced” ceratopsians!

Existing for almost 100 million years, from the Late Jurassic all the way up to the K-Pg mass extinction, ceratopsians originated in Asia and were part of a group called marginocephalians, sharing a common ancestor with the closely related pachycephalosaurs. The earliest members barely resembled their more famous descendants, lacking showy headgear and looking more like fairly generic basal neornithischians -- but by the time of the Late Cretaceous their descendants had migrated across to North America and evolved into large quadrupeds, with some forms like Triceratops being so incredibly common that they must have been the dominant herbivores in their environments.

So let’s start right at the beginning of the group with...

Ceratopsian Month #01 -- Yinlong downsi

Yinlong (meaning “hidden dragon”) was the earliest ceratopsian that we currently know about. Living in China during the Late Jurassic (~161-156 mya), it measured around 1.2m long (4′) and was a transitional form between the basic neornithischian body plan and the later more specialized ceratopsians.

There was only a very small ridge of raised bone at the back of its skull, and its skeleton shared several important anatomical features with pachycephalosaurs. This suggests that many of the characteristics thought to be unique to pachys were actually ancestral to all marginocephalians, and the ceratopsians lost those features early on in their evolution.

It also had enlarged canine-like teeth at the front of its snout, a feature very similar to heterodontosaurids -- which could be the result of convergent evolution, or could mean that heterodontosaurids were much more closely related to marginocephalians than previously thought.

We don’t yet know whether early ceratopsians like Yinlong were fluffy, as depicted above, but the presence of extensive fuzz in basal neornithischians means it was at least a possibility.

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#ceratopsian month 2017#yinlong#ceratopsian#marginocephalia#neornithischia#ornithischia#dinosaur#archosaur#art#feather ALL the dinosaurs#speculative fluffiness#tomorrow: less fluff more quills

292 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ceratopsian Month #18 -- Centrosaurus apertus

Centrosaurus (“pointy lizard”) lends its name to the entire centrosaur group of ceratopsids -- and also to a major branch within the centrosaur evolutionary tree, the Centrosaurini.

Known from Alberta, Cananda, around 76-75 million years ago, it grew up to about 6m long (19′8″) and is known from a huge number of fossils from thousands of individuals in gigantic bonebeds. These seem to represent enormous herds, making Centrosaurus one of of the most common dinosaurs in the region at the time.

It had a single large horn on its nose, which started off pointing backwards as a juvenile and changed shape as it grew, gradually hooking forwards. Two especially long spikes at the top of its frill curved strongly downwards, while its brow horns were reduced to small points.

Skin impressions are also known from one specimen, preserving a region around the right hip and upper leg, showing a pattern of small polygonal scales interspersed with larger rounded scales.

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#ceratopsian month 2017#centrosaurus#centrosaurini#centrosaurinae#ceratopsidae#neoceratopsia#ceratopsian#marginocephalia#neornithischia#ornithischia#dinosaur#archosaur#art#speculative fluffiness#feather ALL the dinosaurs#giving these guys manes because WHY NOT

175 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ceratopsian Month #19 -- Coronosaurus brinkmani

Coronosaurus (“crowned lizard”) was a very close relative of Centrosaurus -- so close, in fact, that it was originally named as a second species of Centrosaurus itself, before being recognized as a separate genus a few years later.

Living around 77 million years ago, it was a medium-sized centrosaur about 5m long (16′4″). Multiple specimens are known from two bone beds in Alberta, Canada, with different ages represented. Juvenile Coronosaurus skulls looked very similar to juvenile Centrosaurus, only developing their own distinct ornamentation as they matured.

It had a slightly backwards-pointing nose horn, brow horns that curved out to the sides, and a pair of downward-curving frill spikes. Uniquely among all known ceratopsians, it also had large irregular masses of short spikelets at the top of its frill forming a distinctive “crown”.

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#ceratopsian month 2017#coronosaurus#centrosaurini#centrosaurinae#ceratopsidae#neoceratopsia#ceratopsian#marginocephalia#neornithischia#ornithischia#dinosaur#archosaur#art#speculative fluffiness#feather ALL the dinosaurs#giving these guys manes because WHY NOT

165 notes

·

View notes