#but this has the classic herbie hancock sample

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Spotify Playlist: Jazz House

Are you a fan of both jazz and house music? If so, you're in luck! We have curated a special Spotify playlist called "Jazz House" that combines the best of both genres. Get ready to groove to the smooth sounds of jazz with a modern twist of house beats. What is Jazz House? Jazz House is a unique blend of jazz and house music, bringing together the sophistication and improvisation of jazz with the infectious energy and electronic elements of house. This fusion genre emerged in the 1990s and has since gained popularity among music lovers who appreciate the fusion of old and new. Why Jazz House? Jazz House offers a refreshing and dynamic listening experience. It combines the timeless melodies and complex harmonies of jazz with the infectious rhythms and pulsating basslines of house music. This fusion creates a vibrant and uplifting atmosphere, perfect for both relaxing and dancing. The Playlist Our "Jazz House" playlist features a carefully curated selection of tracks that showcase the best of this genre. From classic jazz standards reimagined with a house twist to contemporary tracks that seamlessly blend jazz and electronic elements, this playlist offers a diverse range of musical styles and moods. 1. "Cantaloupe Island" - Herbie Hancock (Remixed by US3) This track takes Herbie Hancock's iconic jazz composition and gives it a fresh and funky house makeover. The result is a catchy and groovy tune that will get your head nodding and your feet tapping. 2. "Street Life" - Randy Crawford (The Crusaders, Sampled by Nuyorican Soul) Featuring the soulful vocals of Randy Crawford, this track combines the smoothness of jazz with the infectious energy of house. The sample from The Crusaders' original adds a nostalgic touch to this modern classic. 3. "Moanin'" - Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers (Bobby Blanco's Block Party Mix) Bobby Blanco's remix of "Moanin'" brings a fresh and energetic house groove to this jazz standard. The driving beats and infectious bassline give this track a modern edge while still paying homage to the original. 4. "So What" - Miles Davis (DJ Cam Remix) This remix of Miles Davis' legendary track "So What" adds a laid-back and atmospheric house vibe to the timeless jazz composition. It's the perfect blend of old and new, creating a captivating listening experience. 5. "Take Five" - Dave Brubeck Quartet (The Cinematic Orchestra Remix) The Cinematic Orchestra's remix of "Take Five" breathes new life into this jazz classic. With its mesmerizing electronic elements and hypnotic rhythms, this track takes you on a musical journey like no other. How to Enjoy the Playlist To enjoy our "Jazz House" playlist, simply open Spotify and search for the playlist title. You can also follow the playlist to receive regular updates and discover new tracks that fit the genre. Whether you're hosting a party, studying, or simply looking for some great music to relax to, our "Jazz House" playlist has got you covered. https://open.spotify.com/playlist/5pcU1JB2yM2f5OO90PQyAO?si=ba90de6fa35a44cf Conclusion Jazz House is a genre that brings together the best of jazz and house music. With its infectious rhythms, soulful melodies, and vibrant energy, it offers a unique and captivating listening experience. Our "Jazz House" playlist on Spotify features a diverse selection of tracks that showcase the beauty of this fusion genre. So sit back, relax, and let the smooth sounds of jazz house transport you to a world of musical bliss. Read the full article

0 notes

Photo

Herbert Jeffrey “Herbie” Hancock (born April 12, 1940) is a child prodigy that began playing classical music. At college, he was able to work alongside several prominent members of jazz music and was able to impress them. He recorded his first album solo Takin’ Off, in 1962. the single “ Watermelon Man” got the attention of Miles Davis, who was assembling a new band at the time. After he left Miles’ band, Hancock was able to branch out on his own by forming various other bands defining jazz with a mix of sounds and different genres each decade. In the ‘80s, he gained a new fanbase with his song “Rockit,” a hybrid of hip-hop and electronic music; a music video gave vision to the strange sound. In the ‘90s, the rap group sampled his song, Cantaloupe Island. My dad and friend both suggested I start with his album Maiden Voyage. Hancock can go from playing standard jazz to playing funky, gritty sounds, then playing “beep-boop” electronic sounds; he played a large part in shaping funk, hip-hop, and electronic It is fantastic to see his sound keep growing. Hancock has won numerous awards for his work and collaborates with various artists in music. Hancock can still play traditional jazz and his classical and innovative material. He is one of jazz’s living legends.

#Musician#Composer#Bandleader#Record Producer#Jazz#Post-Bop#Modal Jazz#Experimental Jazz#Funk#Electro

0 notes

Audio

Arena - s/t - reissue of 1975 private-press fusion LP from Australia

If you can imagine the gathering of a group of Australian session musicians channelling the sounds of Herbie Hancock Headhunter’s and Marc Moulin’s Placebo, recording an album out of hours at a TV studio and then releasing a privately pressed hard hitting jazz funk record then what you have is Arena, one of Australia’s most revered and scarce rare groove records. This was the name given to a pick-up group of session players led by Ted White, a veteran of the British big band jazz scene (an associate of Ted Heath and Basil Kirchin) who had immigrated to Australia in the 1960s to work in the burgeoning television industry. This one-time studio project (recorded only to test out the facilities for a new studio) barely yet thankfully saw an LP release in 1975. Pressed in minute quantities only with limited distribution, the album was subsequently forgotten and obscured by time, only to be resurrected in the 90s by DJs and collectors seeking out lost and rare records. The album has since become one of the country’s most celebrated and collectible jazz funk recordings and has proved to be a pivotal point in Australian jazz, marking a shift from the modern jazz and R&B sounds of the previous decades to the cross pollinating electric jazz funk of the 70s. Characterized by the heavy use of electronically treated saxophone, psychedelic guitar, Moog and spacey Fender Rhodes, the album is a classic of the genre. While acknowledging the often compiled and sampled breaks track, The Long One, the complete album offers much more, exemplified by its complicated and obsessive jazz rhythms, abstract and middle-eastern horn lines and pulsing electric funk. The Roundtable are pleased to offer the long awaited reissue of this highly collectible Australian rare groove LP.

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

Visiting Asheville, North Carolina, in December, I walked past a sandwich board that read, “Synth you’re here, come on in.” It was a pop-up store selling T-shirts, mugs, and other memorabilia commemorating one of the town’s most famous citizens, electronic music pioneer Bob Moog.

This month, celebrating what would be the inventor’s 85th birthday, that storefront reopens as the Moogseum. It celebrates not only Moog’s innovations, but also those of his contemporaries who created the synthesizers and other devices that transformed music beginning in the ’60s and ’70s. It’s the latest project of the Bob Moog Foundation–the nonprofit archive and educational institution established in 2006 by his youngest daughter, Michelle Moog-Koussa. (It’s unaffiliated with Moog Music, the company her father founded.)

Moog, who died in 2005, did not invent the synthesizer. Instead, “he’s the one who made it mainstream,” says Mark Ballora, professor of music technology at Penn State University. He became a celebrity, and people used “Moog” (which rhymes with “vogue”) as a synonym for electronic music.

A classically trained pianist, Moog worked closely with a wide range of musicians to understand what they wanted out of a device for generating electronic music. His synthesizers found incredibly diverse applications–from Herb Deutsch’s avant-garde compositions to Bernie Worrell’s funkadelic jams to Wendy Carlos’s classical music blockbuster Switched on Bach. Moog also collaborated with other inventors–including digital music pioneer Max Mathews and even rival synth maker Alan Pearlman (who died in January).

With today’s software-defined digital media, it’s harder to appreciate the naked physics of early electronic music and the radical transformation that manipulating these forces enabled. “Nothing fazes the students now,” says Richard Boulanger, professor of electronic production and design at the Berklee College of Music in Boston, and a protégée of both Moog and Pearlman. “We’re transforming their voices and turning trash cans into drum kits, and we’re sounding like aliens just when we cough.”

ADVERTISING

inRead invented by Teads

But “when we first heard the sound of a Moog synthesizer in the late ’60s and early ’70s . . . it just blew your mind,” says Boulanger. “It was like the sound of the future.” Indeed it was: Today, Moog synthesizers are standard kit for many leading musicians, from Kanye to Lady Gaga.

MOOG FOR THE MASSES

The Moogseum packs a lot into its 1,400 square feet, including iconic instruments like the Minimoog Model D and Minimoog Voyager synthesizers, an interactive timeline of synth technology from 1898 to today, and a replica of Moog’s workbench.

Beyond celebrating the past, the Moogseum aims to teach future generations, including non-musicians. The central vehicle for this is the exhibit Tracing Electricity as It Becomes Sound–an interactive wraparound video projected inside an 8-foot-tall, 11-foot-wide half dome, created by Milwaukee-based media company Elumenati.

“What we’re trying to impart is that you are in the middle of the circuit board, observing what’s going on,” says Moog-Koussa. “There will be a custom knob controller, so that people can actually interact with representations of transistors, capacitors, and resistors,” she adds. “So that they can actually become part of the circuit.” (The foundation aspires to create online versions of exhibits in the coming year.)

This honors Moog’s visceral, even New-Agey, relationship with physics. “I can feel what’s going inside of a piece of electronic equipment,” the inventor said in the 2004 documentary Moog.

He developed that feel when he started building and selling theremins, beginning at age 14 or 15 (Moog said both in different interviews). Invented by Léon Theremin in the 1920s and a staple of sci-fi classics like The Day the Earth Stood Still, the instrument allows players to create eerie tones by moving their hands through electrical fields. Three Moog theremins are on display in the museum.

Moog-Koussa isn’t just trying to cater to people who are already familiar with her father’s work. “Our work in education and archives preservation, and now with the Moogseum, will extend way beyond people who play synthesizers,” she says. The foundation she leads has an ambitious plan to bring hands-on education to schools across the country. It’s finalizing the design for the ThereScope, a battery-powered device that combines a theremin, amplifier, and oscilloscope to visualize the electrical waveforms behind sounds.

This would extend the foundation’s regional education program, Doctor Bob’s Sound School, which began in 2011. The 10-week curriculum now reaches about 3,000 second-graders a year in western North Carolina. “We have 13,000 young children who can read waveforms and explain to you the variances in pitch and volume,” says Moog-Koussa. “And that’s just one of our lessons, out of 10.”

THE STRADIVARIUS OF ELECTRONICS

Unlike the college-dropout entrepreneurs of Silicon Valley, Moog stayed in school–earning a PhD in physics from Cornell in 1965, while continuing his theremin business. In 1964, he built his first “portable electronic music composition system,” later dubbed a synthesizer. The device was capable of producing over 250,000 sounds.

It was not the first synthesizer–a point that Moog-Koussa herself emphasizes. But the high quality captivated musicians. That was despite its temperamental nature. Moog’s early voltage-controlled oscillators, which produce the raw electrical waveforms, were susceptible to current fluctuations from the electric grid and to temperature changes. As they warmed up, the synthesizers drifted out of tune.

To solve the problem, Moog partnered with Pearlman, founder of rival company ARP Instruments. In exchange for Pearlman’s stable oscillator circuit, Moog offered his elegant ladder filter technology, which refines the oscillator output.

“If you start with a raw analog waveform . . . it’s a buzz, like your alarm system,” says Boulanger. “Are you ready to make love songs to the sound of your smoke detector?” He calls Moog’s oscillators and filters “the Stradivarius of electronic instruments.”

Moog’s first synthesizers were huge boxes of electronics stacked and wired together in a spaghetti tangle of patch cables. In 1970, he combined the functions of his modulars into a compact device called the Minimoog Model D, which featured a piano-style keyboard as the main interface. (Pearlman did the same with his iconic ARP 2500.)

The Minimoog eliminated patch cables but included a wide assortment of knobs and switches, plus Moog’s signature mod and pitch-bend wheels. It gave musicians huge latitude in crafting the sounds underlying those piano keys. It also featured a pitch controller, an electronically conductive metal strip that sensed static discharge from the players’ fingers, allowing pitch inflections like those of a stringed instrument. Invented in the 1930s, the technology is proof that touch interfaces long predate the smartphone era.

The Model D controls “liberated” keyboard players, says Boulanger. “It allowed a keyboard player . . . to take a lead role and be so expressive with unique new sounds that reached through and spoke to an audience, like a singer could, like a guitarist could, like a cellist could.”

SUSTAINED SOUND

Moog synths are so central to the music of past-century icons like George Harrison, Herbie Hancock, Kraftwerk, and Parliament-Funkadelic that it’s easy to dismiss them as the sound of the past. Documentaries and articles about the inventor tend to focus on those formative years in the ’60s and ’70s. Moog’s New-Agey sensibilities and lingo further reinforce the old hippy vibe.

But Moog continued innovating into the 21st century. His swan song, the Minimoog Voyager, was released in 2002, just three years before his death from brain cancer at age 71. It was an analog synthesizer, but equipped to interface with digital music equipment.

The synth sounds of Moog and his contemporaries have persisted though a variety of genres and artists. When I asked Moog Music–the company that Bob Moog founded, lost, and then reacquired in his final years–for examples of artists currently using its instruments, I got a list of over 30 acts. The diverse assortment includes Alicia Keys, Deadmau5, Flying Lotus, James Blake, Kanye West, Lady Gaga, LCD Soundsystem, Queens of the Stone Age, Sigur Ros, St. Vincent, and Trent Reznor.

Moog Music’s brand director Logan Kelly also called out up-and-comers, including trippy synth instrumentalist Lisa Bella Donna and the Prince-mentored, all-woman soul trio We Are King. (See the embedded playlist below for samples–or full versions if you’re a Spotify subscriber–from these and other artists.)

And despite the digital tools at their disposal, Boulanger says that his students are also pulling analog devices into their compositions–even modular synthesizers, which are experiencing a revival in a somewhat-miniaturized style called Eurorack.

Moog Music continues to turn out new, hand-built synthesizers. “A lot of the circuitry that Bob designed, we still look to that for inspiration and use it in almost all of our instruments,” says Kelly. Its newest, a semi modular synthesizer called Matriarch, has just gone on sale. The company also puts out limited reissues of classic full-size modulars and synths like the Minimoog Model D.

There are also mobile-app recreations of instruments including the

Minimoog Model D

(which sells for $15) and the

modular Model 15

($30). “It was a UI/UX challenge to capture the feeling and the fun of actually patching [cables for] this instrument on a mobile device,” says Kelly. Companies such as Arturia also make software emulations of Moog’s analog circuits, used as plug-ins for digital music composition. A 2012 Google Doodle even honored the 78th anniversary of Moog’s birth with a

tiny online playable synthesizer

.

And with many of Moog’s, Pearlman’s, and other inventors’ patents having expired, companies such as Behringer and Korg are turning out budget reproductions of classics. They’ve won praise from some musicians, such as Boulanger, for making the devices accessible to starving students, but derision from others who feel the companies are free-riding off the inventors’ legacies.

Behringer’s stripped-down reproduction of the Model D, for instance, sells for around $300 (without a keyboard), vs. $3,749 for Moog Music’s full re-issue (which is no longer in production). Kelly declined to speak on the record about Behringer’s and others’ third-party devices, but emphasized that Moog sells synthesizers in a wide price range, starting at $499.

CONTINUING EDUCATION

We don’t know how Bob Moog would have felt about the knockoffs, but he did work hard to bring music technology to as many people as possible.

“He would champion anyone and everyone,” says Boulanger, who describes himself as being “just some little guy” composing music when he met Moog in 1974. “He ended up writing articles about some of my music in Keyboard magazine [in the mid-1980s] and helped launch my career,” says Boulanger.

“When my father developed a brain tumor and was quite ill, we set up a page on CaringBridge for him,” says Michelle Moog-Koussa. “And from that we got thousands of testimonials from people all over the world about how Bob Moog had impacted and sometimes transformed people’s lives.”

But Moog’s five children were largely left out of that experience. “My father really held his career at arm’s length from our family,” says Moog-Koussa. She believes this comes from her father’s wariness of parents projecting desires onto their children.

“He had a very domineering mother who wanted him to be a concert pianist, and was quite heartbroken when he decided to pursue electronics,” she says. (Moog studied piano from age 4 to 18 and was on his way to a professional musical career when he pivoted to engineering.)

“We kind of knew the basics [of his work], but, at least half of those basics, we learned from external sources,” says Moog-Koussa. They also knew few of their father’s collaborators, aside from Switched-On Bach creator Wendy Carlos.

Since her father’s death, Moog-Koussa says she’s developed relationships with many of the legends her father worked with, such as composers Herb Deutsch and Gershon Kingsley and musicians Rick Wakeman, Herbie Hancock, Stevie Wonder, and the late Keith Emerson.

In a way, the foundation and Moog Museum seem as much an effort of Moog’s own family to discover their father as to educate the rest of the world.

“I don’t think we realized the widespread global impact and the depth of that impact,” she tells me. “And we thought, here’s the legacy that has inspired so many people from all over the world. That not only deserves to be carried forward, but it demands to be carried forward.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Songs in the Key of Life

This is an entry I posted yesterday on Facebook but was quickly told that it was entirely too long for Facebook. However it was suggested that I write a blog instead so … here goes we’ll see how this goes… please read and enjoy …

"Songs in the Key of Life" is the eighteenth album by American recording artist Stevie Wonder, released on September 28, 1976, by Motown Records, through its division Tamla Records. It was the culmination of his "classic period" albums. An ambitious double LP that included a four-song bonus EP, the album became the best-selling and most critically acclaimed album of Wonder's career. In 2003, it was ranked number 57 on Rolling Stone magazine's list of the 500 greatest albums of all time. In 2005, it was inducted into the National Recording Registry by the Library of Congress, which deemed it "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."

By 1976, Stevie Wonder had become one of the most popular figures in R&B and pop music, not only in the U.S., but worldwide. Within a short space of time, the albums Talking Book, Innervisions and Fulfillingness' First Finale were all back-to-back top five successes, with the latter two winning Grammy Award for Album of the Year, in 1974 and 1975, respectively. By the end of 1975, Wonder became serious about quitting the music industry and emigrating to Ghana to work with handicapped children. He had expressed his anger with the way that the U.S. government was running the country. A farewell concert was being considered as the best way to bring down the curtain on his career. Wonder changed his decision, when he signed a new contract with Motown on August 5, 1975, thinking he was better off making the most of his career. At the time, rivals such as Arista and Epic were also interested in him. The contract was laid out as a seven-year, seven LP, $37 million deal ($172,277,675 in today's money) and gave him full artistic control, making this the largest deal made with a recording star up to that point. Almost at the beginning Wonder took a year off from the music market, with a project for a double album to be released in 1976. There was huge anticipation for the new album which was initially scheduled for release around October 1975. It was delayed on short notice when Wonder felt that further remixing was essential. According to Wonder, the marketing campaign at Motown decided to take advantage of the delay by producing "We're almost finished" T-shirts. Work on the new album continued into early 1976. A name was finally chosen for the album: Songs in the Key of Life. The title would represent the formula of a complex "key of life" and the proposals for indefinite success. The album was released on September 28, 1976, after a two-year wait as a double LP album with a four-track seven-inch EP titled A Something's Extra ("Saturn", "Ebony Eyes", "All Day Sucker" and "Easy Goin' Evening (My Mama's Call)") and a 24-page lyric and credit booklet. A total of 130 people worked on the album, but Wonder's preeminence during the album was evident. Among the people present during the sessions, there were legendary figures of R&B, soul and jazz music – Herbie Hancock played Fender Rhodes on "As", George Benson played electric guitar on "Another Star", and Minnie Riperton and Deniece Williams added backing vocals on "Ordinary Pain". Mike Sembello was a prominent personality throughout the album, playing guitar on several tracks and also co-writing "Saturn" with Wonder. Some of the most socially conscious songs of the album were actually written by Wonder with other people – these included "Village Ghetto Land" and "Black Man" (co-written with Gary Byrd) and "Have a Talk with God" (co-written by Calvin Hardaway). Nathan Watts, Wonder's newest bass player at the time, originally recorded a bass track for "Isn't She Lovely" that Wonder replaced with his own keyboard bass for the final version. The same guide-track method was employed for "Knocks Me Off My Feet". At the time of release, reporters and music critics, and everyone who had worked on the album, traveled to Long View Farm, a recording studio in Massachusetts for a press preview of the album. Everybody received autographed copies of the album and Wonder gave interviews. Critical reception was positive. The album was viewed as a guided tour through a wide range of musical styles and the life and feelings of the artist. It included recollections of childhood, of first love and lost love. It contained songs about faith and love among all peoples and songs about social justice for the poor and downtrodden. On February 19, 1977, Stevie was nominated for seven Grammy Awards, including Album of the Year, an award that he had already won twice, in 1974 and 1975, for Innervisions and Fulfillingness’ First Finale. Since 1973, Stevie’s presence at the Grammy ceremonies had been consistent – he attended most of the ceremonies and also used to perform on stage. But in 1976, he did not attend as he was not nominated for any awards (as he had not released any new material during the past year). Paul Simon, who received the Grammy for Album of the Year in that occasion (for Still Crazy After All These Years) jokingly thanked Stevie “for not releasing an album” that year. A year after, Wonder was nominated for Songs in the Key of Life in that same category, and was widely favored by many critics to take the award. The other nominees were Breezin’ by George Benson, Chicago X by Chicago, Silk Degrees by Boz Scaggs, and the other favorite, Peter Frampton’s Frampton Comes Alive!, which was also a huge critical and commercial success. Wonder was again absent from the ceremony, as he had developed an interest in visiting Africa. In February he traveled to Nigeria for two weeks, primarily to explore his musical heritage, as he put it. A satellite hook-up was arranged so that Stevie could be awarded his Grammys from across the sea. Bette Midler announced the results during the ceremony, and the audience was only able to see Wonder at a phone smiling and giving thanks. The video signal was poor and the audio inaudible. Andy Williams went on to make a public blunder when he asked the blind-since-birth Wonder, “Stevie, can you see us?” In all, Wonder won four out of seven nominations at the Grammys: Album of the Year, Best Male Pop Vocal Performance, Best Male R&B Vocal Performance and Producer of the Year. Over time, the album became a standard, and it is considered Wonder's signature album. "Of all the albums," he told Q magazine (April 1995 issue), "Songs in the Key of Life I'm most happy about. Just the time, being alive then. To be a father and then… letting go and letting God give me the energy and strength I needed." Songs in the Key of Life is often cited as one of the greatest albums in popular music history. It was voted as the best album of the year in The Village Voice's annual Pazz & Jop critics poll; in 2001 the TV network VH1 named it the seventh greatest album of all time; in 2003, the album was ranked number 57 on Rolling Stone Magazine's list of the 500 greatest albums of all time. Many musicians have also remarked on the quality of the album and its influence on their own work. For example, Elton John said, in his notes for Wonder on the 2003 Rolling Stone's list of "The Immortals – The Greatest Artists of All Time" (in which Stevie Wonder was ranked number 15): "Let me put it this way: wherever I go in the world, I always take a copy of Songs in the Key of Life. For me, it's the best album ever made, and I'm always left in awe after I listen to it." In an interview with Ebony magazine, Michael Jackson called Songs in the Key of Life his favorite Stevie Wonder album. George Michael cited the album as his favorite of all time and with Mary J. Blige covered "As" for a 1999 hit single. Michael performed "Love's in Need of Love Today" on his Faith tour in 1988, and released it as a B-side to "Father Figure". He also performed "Village Ghetto Land" at the Nelson Mandela 70th Birthday Tribute in 1988. He later covered "Pastime Paradise" and "Knocks Me Off My Feet" in his 1991 Cover to Cover tour. R&B singers in particular have praised the album – Prince called it the best album ever recorded, Mariah Carey generally names the album as one of her favorites, and Whitney Houston also remarked on the influence of Songs in the Key of Life on her singing. (During the photoshoot for her Whitney: The Greatest Hits, as seen on its respective home video, the album was played throughout the photo sessions, at Houston’s request.) The album's importance has even been recognized by heavy metal musicians, with singer Phil Anselmo describing a live performance of Songs in the Key of Life as "a living, breathing miracle". The album’s tracks have provided numerous samples for rap and hip-hop artists; for example, "Pastime Paradise", which itself drew on the first eight notes and four chords of J.S. Bach's Prelude No. 2 in C minor, was reworked by Coolio as "Gangsta's Paradise". In 1995, smooth jazz artist Najee recorded a cover album titled Najee Plays Songs from the Key of Life, which is based entirely on Wonder's album. In 1999, Will Smith used "I Wish" as the base for his US number-one single "Wild Wild West". The song repeated the main melody of "I Wish" as a riff and some lyrics re-formed. In April 2008, the album was voted the "Top Album of All Time" by the Yahoo! Music Playlist Blog, using a formula that combined four parameters – "Album Staying Power Value + Sales Value + Critical Rating Value + Grammy Award Value". In December 2013, Wonder did a live concert performance of the entire Songs in the Key of Life album at the Nokia Theater in Los Angeles. The event was his 18th annual House Full of Toys Benefit Concert, and featured some of the original singers and musicians from the 1976 double-album as well as several from the contemporary scene. In November 2014, Stevie began performing the entire album in a series of concert dates in the U.S. and Canada. The start of the tour coincided with the 38th anniversary of the release of Songs in the Key of Life. Highly anticipated at the time, the album surpassed all commercial expectations. It debuted at number 1 on the Billboard Pop Albums Chart on October 8, 1976, becoming only the third album in history to achieve that feat and the first by an American artist (after British singer/composer Elton John's albums Captain Fantastic and the Brown Dirt Cowboy and Rock of the Westies, both in 1975). In Canada, the album achieved the same feat, entering at number one on the RPM national albums chart on October 16. Songs in the Key of Life spent thirteen consecutive weeks at number one in the U.S., and 11 during 1976. It was the album with the most weeks at number one during the year. In those eleven weeks, Songs in the Key of Life managed to block four other albums from reaching the top – in order, Boz Scaggs’s Silk Degrees, Earth, Wind & Fire's Spirit, Led Zeppelin's soundtrack for The Song Remains the Same and Rod Stewart's A Night on the Town. On January 15, 1977, the album finally dropped to number two behind Eagles' Hotel California and the following week it fell to number four. On January 29 it returned to the top for a fourteenth and final week. The album then began its final fall. It spent a total of 35 weeks inside the top ten and 80 weeks on the Billboard albums chart. Songs in the Key of Life also saw longevity at number one on the Billboard R&B/Black Albums chart, spending 20 non-consecutive weeks there. In all, Songs in the Key of Life became the second best-selling album of 1977 in the U.S., only behind Fleetwood Mac's blockbuster Rumours, and was certified as a diamond album by the RIAA, for sales of 10 million units in the U.S. alone (each individual record or disc included with an album counts towards RIAA certifications).[33] It was the highest selling R&B/Soul album on the Billboard Year-End chart that same year.[34] Songs in the Key of Life was also the most successful Wonder project in terms of singles. The lead-off, the upbeat "I Wish" was released in November 1976, over a month after the album was released. On January 15, 1977, it reached number one on the Billboard R&B chart, where it spent five weeks at the top. Seven days after, it also reached the summit of the Billboard Hot 100, although it spent only one week at number one. The track became an international top 10 single, and also reached number five in the UK. "I Wish" became one of Wonder's standards and remained one of his most sampled songs. The follow-up, the jazzy "Sir Duke", surpassed the commercial success of "I Wish". It was released in March 1977 and also reached number one on the Billboard Hot 100 (spending three weeks at the top starting on May 21) and the R&B chart (for one week, starting on May 28). It also reached number two in the UK, where it was kept off the top spot by the song "Free" by Deniece Williams, who had provided backing vocals on the album. As sales for the album began to decline during the second half of 1977, the two other singles from Songs in the Key of Life failed to achieve the commercial success of "I Wish" and "Sir Duke". "Another Star" was released in August and reached only number 32 on the Hot 100 (number 18 on the R&B chart, and number 29 in the UK) and "As" came out two months later, peaking at number 36 on both the Pop and R&B charts. Though not released as a single, "Isn't She Lovely" received wide airplay and became one of Wonder's most popular songs. It was soon released by David Parton as a single in 1977 and became a top 10 hit in the UK.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Casio CT-S1000V Evaluate: A Synth That Can Sing

You may want to study music, however no one needs to spend a thousand {dollars} on a keyboard solely to understand they hate it. Most individuals purchase a newbie keyboard to pound out “Hey Jude,” the type of plasticky mannequin that you just in all probability bear in mind from center faculty. They work advantageous as instruments to fabricate sound along with your fingers, however the precise tones depart a bit to be desired. That’s why I’ve loved my time with the Casio CT-S1000V. It is a modern $470 mannequin that acts as a wonderful newbie keyboard, however with one significantly cool get together trick: You’ll be able to program lyrics into it and have the keyboard sing for you. It’s a rad software for these of us with voices like indignant crows. Between strong building, good sounds, and an easy-to-navigate interface, I feel this board is the right place for freshmen to start out. The vocal synthesis engine is cool sufficient that even die-hard synth nerds will need to fiddle after they come verify your progress. Traditional Casio Classic Casio fashions are beloved by indie darlings like Mac Demarco for a purpose. These fundamental, utilitarian keyboards sound as nostalgic as they’re practical. Like many Casios earlier than it, this one has a good keyboard and 800 built-in sounds, with every thing from boring piano to spacey synths represented. You additionally get 243 rhythms to play together with, must you want some inspiration. You’d be shocked how far sounds have come because you final messed with a keyboard at Guitar Heart earlier than Covid. The workforce at Casio has included some legitimately nice sounds, stuff you’d have paid hundreds of {dollars} for earlier than the iPhone period (hear samples beneath). You’ll be able to plug the keyboard into an amp or use it as a MIDI keyboard with a pc, however I truly appreciated simply utilizing the built-in audio system on the highest. It makes it simple to jam together with music, or to shortly pattern sounds with out the effort of turning on an amp or opening the Casio Music Area app (which works for iOS and Android and pairs to the keyboard). The included LCD show works nicely in darkish rooms, and it offers you fairly granular management over every thing you would possibly need to regulate when enjoying. You’ll be able to assign two knobs on the highest left of the board to do numerous filters, results, and EQ strikes, and there’s a very usable pitch-bend wheel on the far left aspect, for whenever you need to really feel like Herbie Hancock within the Nineteen Seventies. Getting Related {Photograph}: Casio You will get sound data out of the keyboard 4 methods: by the aforementioned audio system, a headphone jack, stereo ¼-inch outputs, or through USB. It’s also possible to use the keyboard as a sampler on your favourite music, with the power to seize sounds from Bluetooth audio and use an inside six-track sequencer to line up a beat. When you’re plugged in, you may simply fiddle and save any sounds that you just discover you want for later. Talking of mucking round and discovering cool sounds, I actually did fall in love with the brand new vocal synthesis engine. It’s simple to sort lyrics into the Casio Lyric Creator app (iOS, Android) after which switch entire songs of lyrics to the keyboard. When you actually hate to sing, otherwise you significantly love Daft Punk or Peter Frampton, you’ll be in love. You should utilize 22 totally different vocal sounds and manipulate them with a reasonably broad number of results and different sound parameters. The vocal synth is polyphonic, which suggests you may play actually cool harmonies (hear beneath) over your personal phrases. Originally published at Fresno News HQ

0 notes

Text

Interview: Seth Graham

The music published by Orange Milk, an underground behemoth of experimental music and cassette culture co-founded by Seth Graham and Keith Rankin (a.k.a. Giant Claw), feels like multiple authors contributing their stories to one sprawling space opera. The label has been lauded by a wide spectrum of listeners and critics, and is instantly recognized through a delightful, kaleidoscopic approach to color, sound, and aesthetic identity. Themes and approaches in the collective Orange Milk output seem impossible to define coherently. There are oozing, primordial cultures of bacterial sound, moments of pure, demented bliss; Seth Graham’s own music, especially on his latest album Gasp, refines these abstract elements while rocketing them farther into space. It is intrepid music that deliberately hovers on the edge of order, a space that the composer challenges himself to explore. We caught up with Seth Graham over the phone to talk about Herbie Hancock, the various MIDI instruments he chose to explore on Gasp, and the experiences in his life that brought the album to bear. The album is available to pre-order here (LP) and here (CD), but you can also listen to the full release below before its March 23 release. --- Gasp contains a wide variety of sounds, but it’s very focused too. Some of them appear multiple times, like the woodwind, the voices. Did you have a clear idea of what instruments you wanted to appear, and when? I definitely had a very specific idea… like that composer Gerard Grisey, he has pieces where he records the cello super close to the mic. You can almost hear the rustling, and it’s high-res. It almost sounds like, I don’t wanna say explosion, but it’s a bigger, weirder experience. With classical, when they record it, you hear that typical Tchaikovsky crap; it almost sounds generic. Grisey changed it and put it in your face, and I love that so much. So what I did with the record is any of the instruments that had a really close mic sample [in the VST], I kind of only used those because I liked how they sounded, and I liked how much you could manipulate it. Like for example in the track “Kimochi,” which just means emotion in Japanese, that track starts off with this voice that says one syllable, and that goes into almost sheer metal grinding, and that’s actually just a shit-ton of manipulation of different acoustic instruments with a certain synth. I love to do that and contrast it with that close-mic’d sound. With the flute, you can hear the wind of the person playing. I was obsessed with that. It ended up being a lot of flute, clarinet, cello, and that was kind of it. I think I used some trombone — there’s certain things you can do with the VST where you can hear the whole sample play out, and you can hear the clicking, and I would use that too, people clicking the wind instruments. I was thinking I should just hire people and record it my fucking self. That was something I wanted to ask you about — whether you had plans — or already did — record live instruments and manipulate that? I actually sort of did that already. A record is supposed to come out; it’s pieces from Gasp and a couple of unreleased pieces that this ensemble in Russia asked me to write for a tribute to Philip Glass that they were doing. They asked me and Sean McCann and Sarah Davachi, and I was really honest, like, I’ve never written a classical piece before, I just write MIDI data and mess with it. I just kind of read up on how to write for an ensemble, looked up the instruments they use, re-wrote it all in MIDI. I basically converted that to notation and sent four pieces to them that are pieces from Gasp, but real people. And they did it! They played it at the Museum of Multimedia and Arts in Moscow, and then they played it in a studio, and they were supposed to send us the stems for us to mix and Sean to put out on his label, Recital… and I don’t know, I’m waiting for it. It should be here. But to answer your question, I’ve been trying to think of ways for a new record where I hire people and I write out pieces, and they play it-slash-sing it, because I want really weird things to happen that I can’t make software do. I go to school with someone who’s a trained opera singer, and I want to pay her to sing what I have all notated, her to sing in this key, but then go “Bleahghghg.” I would love to hear that happen, a magnificent operatic voice just shit the bed. That would be awesome. I’ve been trying to think of ways for a new record where I hire people and I write out pieces, and they play it-slash-sing it, because I want really weird things to happen that I can’t make software do. I go to school with someone who’s a trained opera singer, and I want to pay her to sing what I have all notated, her to sing in this key, but then go “Bleahghghg.” Your use of “real instruments” stands apart from other kind of abstract electronic music, like PC Music, where they’re deliberately trying to sound as synthetic as they can. I’m really influenced by a lot of the modern computer music, like Halcyon Veil, or Jesse Osborne-Lanthier, or Rabit, or Chino Amobi… I like all that stuff, but I have a weird aversion to reverb. I feel like reverb makes things cloudy, and in the listening experience, it kind of masks nothing. It could be an art in itself, but I really tried to stay away from it but still be influenced by their aesthetic. That’s interesting you mention that, because Gasp contains lots of open, bare spaces, which really struck me when I heard it. Yeah, and I interpret that as straight-up vulnerability. Just let myself be vulnerable. Vulnerability is such a strength that I admire in people, people who can just admit things and let it be. There’s not even close to enough of that in our world. Even myself I don’t let myself be vulnerable enough, but I think it’s such a beautiful thing, and if the music is kind of awkward and there’s that space, I think it conveys vulnerability. It conveys a sense of drama, too. It does, doesn’t it? I am dramatic, I guess. Ha! Going back to that idea of fate you mentioned earlier, I’m curious as to what the events were that would construct that fate. Like what events took place in your life to form your influences? Well, I had a really crazy life. I grew up in Japan; my parents were missionaries. I went there when I was six, my mom got really sick — I don’t know why to this day, my parents are, uh, really weird. I was kind of shoved into a public school at six; my dad was studying Japanese at a language school. The language school was across the street from a tennis court. The city is Kadiza, in Nagano-ken — it’s kind of considered the Aspen of Japan — is very ritzy and beautiful. And one day I’m at the language school waiting for my dad, and I was just starting to learn Japanese. I was immersed in it because nobody spoke English, and I couldn’t understand anything. And literally, one day I understood everything everyone was saying. It was about seven months in and it was so surreal. I remember thinking “What is my life? This is not normal…” And I knew it, but I didn’t even know how to think of it as a six-, seven-year-old. I’m sitting there, and I’m watching all these people playing tennis, and there are cameras there, but I’m just watching with my face against the fence. Someone comes up to me and says, “That’s the emperor of Japan.” I always remembered that. There was a lot of shit that happened there. I started to be a teenager in Japan, and we moved back when I was 15… So you spent your formative years there? Yeah, my formative years were spent in Japan. I started skateboarding in Japan, became a really avid skateboarder, and we even were responsible for finding a really famous skate spot. We came back to the US when I was 15. I was really into Japanese punk-rock; I remember the day Kurt Cobain died — I was really into Nirvana. The real formative thing was when I came back to the US. My parents were really conservative… like I can’t overstate it enough. So I came back from Japan, skateboarding, and punk rock, to rural Ohio, where everyone played football. My parents didn’t want me to go to school because they thought I would become a corrupt atheist, so I didn’t. I was homeschooled and worked at a movie theater from 15 to 18, and I would pretend to do my homework and finish by 11, and then go work the matinee shift with this old woman named Phyllis. The reason I tell you all this is that the shock of cultural difference put my brain into a spin. Everything became very existential to me at a very young age. I was like, “Nothing means anything.” I realized in 6th grade that the Japanese didn’t like America — I went to Hiroshima on a field trip and they were all like, fuck America — but all my life I had heard about how great America was, so you start to see the dissonance at a young age. Which is true? So when I was really young I started to throw it all out the window, like all of it was a joke to me, but not as a rebellious teenager, it was a true existential crisis to me. I started to notice the deep contrast in everything, and I started to notice all the little things instead of the big things. That changed how I perceived everything, I think. And I think that’s what helps me be creative, if I am even creative. That was the most colossal thing, that upbringing and those events. Goop by Seth Graham You and [ex-TMT contributor] Keith Rankin knew each other in Ohio when you both started Orange Milk around 2010. Could you explain the environment you were in and your ideas of what the label was going to be like? People want like a glorious answer when they ask that, but there isn’t one. It was honestly Keith and I were making music ourselves, and we both kept getting rejected by labels… Probably for good reasons. We were like, “Aw, fuck that, let’s start our own label to release our own stuff.” It was kind of a hybrid between there being certain artists who were only on tape who we thought should come out on LP. One of them was an album called Crowded Out Memory by this band called Caboladies. This band Talkies. That was kind of the Robert Beatty crew, like Eric Lampan and Christopher Bush; they had this band that were kind of spastic, fun electronica. We loved it, and that album in particular came on a really limited CD-R, and we were like, “That should be on LP!” It was like when all that rage with Emeralds was happening in our little pocket scene. And not that it was a competition, but we thought Caboladies was far more interesting, and we wanted to bolster it for that reason. We were just like… I don’t want to hear synth drone. We would send each other clips by a really wide variety of artists. We were imaging things we wanted to hear together, in some weird way. Like the Herbie Hancock Raindance record. All kinds of little clips, like, “This album, but only these parts.” We did have a very conscious conversation to decide where we wanted to go, and then we just started digging it up. We just started searching for things that we liked on SoundCloud. Would you consider that your contribution to music or to your pocket of the music world? Is establishing that family your driving force? I think Keith and I really wanted to be in the music world, and we kind of constantly got rejected a lot. We wanted to find our own. And we were, I wouldn’t say critical, but we were really into this idea of experimental music being really joyous and really accessible. Like folk music or something. And we really consciously saw it that way. We would sit down and listen to Herbie Hancock — I think I’ve mentioned him a few times, but we’re obsessed — and we would listen to his records and say, “This part is pure joy, but it sounds insane.” We want to make that, and we want to hear that, and have a label go full-tilt on making that. It’s one of my favorite things about Hancock. His music is chill and inviting and so weird at times. I just love that. It feels like you can let go — it can be contemplative, it can be deep, it can be all that Tiny Mix Tapes stuff, or it can just be pure fun! I think we both find it really refreshing. And we like releasing our own stuff because it just gives us control and makes it less bureaucratic or political. It’s less about hustling. I don’t have to worry about being judged. That freedom is nice as an artist. You’ve mentioned joy a few times as an important theme in your music… I feel joy a lot, so I was just trying to convey that as much as I could. Vulnerability is such a strength that I admire in people, people who can just admit things and let it be. There’s not even close to enough of that in our world. Even myself I don’t let myself be vulnerable enough, but I think it’s such a beautiful thing, and if the music is kind of awkward and there’s that space, I think it conveys vulnerability. What about the process of making music? Does that bring joy? Your music sounds very playful, so I’m wondering to what degree your process involves discovery or “play,” in the kind of childlike way of working things out? Ha! Making the music is torture. I feel like Keith and I have high standards with each other. If I make a track and send it to him, he’s going to kind of rip it apart. It’s kind of like a professor reviewing your work. We both treat it as a helpful device, we’re not trying to shit on each other, we both really love each other so there’s that trust. It’s a rare thing. But in that sense, my record felt like a master’s thesis. It was so much work, and so much time, and agony. But I still love doing it. To answer your question, I was trying to be super-direct — this is how I feel, a lot of the time. It’s kind of funny, joyous, kind of awkward at times. I wanted those elements to be in there, and I have this kind of aversion to authority. I associate it with pretension. I’m not saying it’s objective, but pretension and authority to me are the same thing. It’s about controlling you, or controlling how you will experience something. And if you let that go, you can make with it what you will, know what I mean? That might sound like pretentious nonsense, I don’t know. Was the record heavily composed our conceptually wrought before you began to work on it? It was a mixture of everything. After talking to people who are actually trained classically, I get the vibe that everybody has a similar method. Some things are conceptually thought out, like I want this sound or that sound, and then you build a structure to execute that sound. I would write MIDI parts that were like, a cello pizzicato, and I would write it until I really liked it, and then let it sit. And I would play with Serum [VST], and be like, I like this sound that sounds like metal is coming out of my eyeball, how can I fixate on this thing? It’s almost like assembling a painting — I like this shape, this color, and then you just edit it and fit it in. OK, now I’m going to add clarinet, like right here. You mess with that sequence forever. That’s what I did, but with Gasp, I tried to take it as far as I could. In that once I had a structure I really liked, I would hate the song. Even though I liked all the parts, I would then edit it down — like how fucked up could I make this? — until it feels barely cohesive. So did this process yield tons of material? How did you decide what would make the final cut? At one point when I was making it, I got so tired that I just wanted to put it up on Bandcamp and never think about it again. I basically revised like 70% of it, and that was like a year in. But I just knew it wasn’t done. So you just keep going with the record. There were moments when I was just completely improvising. I would take Push 2 [the Ableton Live controller/sequencer], just randomly play it, hit things, turn things. I don’t come up with much that way, but every once in a while when I get really frustrated, I’ll just improvise and see what happens. It usually yields like three hours of dicking around. But I always end up in what seems like a final crescendo, where I think back through so many times, you have to do, over and over, tedious. Sometimes you have to delete everything, and you go over it again and half of it is good. And once you’re 80% done, you can’t stand the other 20%, but you’re so sick and tired of it, it’s torture. That’s what it felt like. But I love it, and now I’m all ready to do another one. It’s kind of all I can think about. http://j.mp/2u69i63

1 note

·

View note

Text

Takuya Kuroda announces a new album “'Fly Moon Die Soon” and shares his first single “Change” with Corey King.

Takuya Kuroda announces a new album “'Fly Moon Die Soon” and shares his first single “Change” with Corey King. Takuya Kuroda is a highly-respected trumpeter, is a forward-thinking musician that has developed a unique hybrid sound, blending classic groovy hard-bop, post-bop, soulful jazz, contemporary funk, fusion and hip hop music. The album consists of nine tracks, seven original compositions, and two classics Ohio Players “Sweet Sticky Thing” featuring Alina Engibaryan on vocals, and Herbie Hancock “Tell Me A Bedtime Story”. For this record Takuya Kuroda freed himself from the constraints of standard tracking with a live band and made hearty use of beats, sampling, overdubs, and other studio magic while also inviting musicians into the studio periodically to collaborate, keeping the collaborative and rough-edged spirit intact. After first listen of the album ended up straight on my personal “best albums of 2020”. It’ s great music, from soul-jazz to funk-jazz through beats, great grooves, heavy basslines and unique sound of Takuya’s trumpet. This album is a must. Watch below a video to Takuya Kuroda feat Corey King new song “Change”, the first single from his forthcoming album “'Fly Moon Die Soon”: Takuya Kuroda has come a long way from his early forays into jazz. Born and raised in Ashiya, a coastal city located between Kobe and Osaka, he has been a resident of New York for the past 15 years, and now channels the energy of both cultures. Read the full article

#AdamJackson#ChrisMcCarthy#CoreyKing#CraigHill#FirstWordRecords#Japan#jazz#RashaanCarter#SolomonDorsey#TakeshiOhbayashi#TakuyaKuroda#USA

0 notes

Photo

Herbert Jeffrey “Herbie” Hancock (born April 12, 1940) is a child prodigy that began playing classical music. college he was able to work alongside a number of prominent members in jazz and was able to impress them. He recorded his first album solo Takin’ Off in 1962 the single “ Watermelon Man” got the attention of Miles Davis, who was at the time assembling a new band. After he left Miles’ band Hancock was able to branch out on his own by forming various other bands defining jazz with a mix of sounds and other genres each decade. In the ‘80s he gained a new fanbase with his song “Rockit ” which is a hybrid of hip hop and electronic music there was a music video that gave vision to the eccentric sound In the '90s the rap group sampled his song, Cantaloupe Island. My dad and friend both suggested I start with his album Maiden Voyage. Hancock can go from playing standard jazz to playing funky, gritty sounds then playing "beep-boop" electronic sounds he played a large part in shaping funk, hip-hop, and electronic It is amazing to see his sound keep growing. Hancock has won numerous awards for his work and collaborates with various artists in music Hancock can still play traditional jazz as well as his classical and his own innovative material he is one of jazz’s living legends.

#Musician#Singer-Songwriter#Composer#DJ#Record Producer#Jazz#Post-Bop#Modal Jazz#Fusion#Clark Terry#Miles Davis#Wayne Shorter#The Headhunters#Howard Jones

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Avishai Cohen: Big Vicious (ECM, 2020)

Note: Jazz Views with CJ Shearn will now have a more detailed sound category offering audiophile insight into recordings as part of review thanks to upgraded equipment.

Key terms:

Sound stage: The audio depiction of the placement of instruments, as if one were to go see a play and see the position of the actors/actresses on stage, when a listener closes their eyes, they can see and hear the placement of the players and instruments. The term stereo image can also be applied.

Stereo imaging refers to the aspect of sound recording and reproduction of stereophonic sound concerning the perceived spatial locations of the sound source(s), both laterally and in depth. (source for stereo image definition: wikipedia)

Avishai Cohen: trumpet, effects, synthesizer; Uzi Ramirez: guitar; Jonathan Albalak: guitar; bass; Aviv Cohen: drums; Ziv Ravitz: drums, live sampling.

Jazz, over the past three decades especially has become a global language. The music by it's very nature is inclusive, taking on elements from all over the world, while maintaining it's core identity. Yet despite this statement, a debate still rages on about what jazz is, for some it may be Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, the acoustic period of Miles Davis. While Miles Davis' electric music, Weather Report, Return to Forever, Bill Frisell, John Abercrombie, John McLaughlin and Pat Metheny among others were all artists that brought something inherently fresh to the table. All these artists were rooted in jazz tradition but not hemmed in. Since Wynton Marsalis arrived on the jazz scene in the late 1970's, and after garnering a major label deal with Columbia in 1981, continuing on to his becoming director of the newly founded Jazz At Lincoln Center in 1987, the age old debates of what jazz is flared up. These debates always existed but began to intensify when record labels, who had been on the cutting edge of recording jazz-funk, jazz-rock and other needlessly coined permutations, suddenly sharply focused on acoustic straight ahead jazz. The music was made by young, primarily African American musicians, and like earlier decades, statements on who they were as players, and their place in society. Many of the musicians from that specific time period of the 80's-90's have had a strong impact on current jazz, and a lot of the musicians who are major figures, like Wynton and Branford Marsalis, Jeff “Tain” Watts, the late Roy Hargrove, Nicholas Payton and Joshua Redman have been influences on the generations of 20 and 30 somethings who are on the front lines.

Israeli born trumpeter Avishai Cohen is just one of many musicians, who have been influenced by this so called “young lion” period, but has distinctly, like fellow Israeli ECM labelmates Oded Tzur, Anat Fort and Shai Maestro brought forth influences from that country's music but also music across genres that were inspiring. This is the name of the game in jazz now, musicians bringing forth what inspired them, whether it be Nirvana, Radiohead, Boards of Canada, Wu Tang Clan or anything they grew up with.

For the fourth album bearing his name for ECM, Cohen debuts an exciting new quintet project Big Vicious. The quintet, made up of the leader on trumpet, effects and synthesizer, guitarist Uzi Ramirez, guitarist and bassist Jonathan Albalak, and the double drum tandem of Aviv Cohen and Ziv Ravitz on drums and live sampling, an all Israeli group bring a powerful and potent combination... acoustic and electric hybrid music with slamming grooves, textures reaching the cosmos and some tight rope walking improvisation that is a very distinct and personal blend. The group had been playing much of the music on the road for sometime, playing the originals here and covers such as Massive Attack's trip hop classic “Teardrop” part of a stream of music which all had grown up on. The mix of jazz and electronic proclivities is a result of all their collective experience and was tightened in the studio at producer Manfred Eicher's suggestion which distilled the music to it’s essence considerably. Each player in the group brings their experiences of jazz and elsewhere, and the notion of soloing is less important than overall feeling and textures. This practice governed much of Weather Report’s early work as well, but it is only a surface resemblance in this new collection.

Aviv Cohen's fat, thudding kick, and deep, thunderous dead snare set the tone for the sing songy “Honey Fountain” of which the trumpeter's bright tone make the most of. Albalak and Ramirez' guitars and bass are an important component, and Cohen's groove are important because, a variation of the same groove is also found on the penultimate “Teno Neno”. The track is like an movie introduction. “Hidden Chamber” introduces much darker sonic tapestries including a weird, altered pitch underpinning with fuzzy harmonics, somewhat reminiscent of the T-1000 sound effects from Terminator 2. Ravitz's more jazz centric approach tease at some burning swing as things build to a sparkling climax, drummer Cohen more in the pocket over Ravitz' implied swing. The spoken word samples of Einstein and Wayne Shorter are a nice touch as they suggest the infinite nature of space. “King Kutner” is a joyous anthemic blast, Guitar and synth together combine like lovely shining stars.

Three pieces in particular serve as album centerpieces. The group's treatment of “Moonlight Sonata” is breathtaking with Cohen's almost bucolic melodic treatment, the guitars, and electronics stroke bold dark colors on a beautiful canvas. The trumpeter uses the melodic contours for wonderful dynamic exploration, with dark, scratchy guitar again suggesting the beauty of the cosmos. Cohen's trumpet and subtle ad libs are almost operatic in nature, bright like the stars on this wonderful moonlight night. “Fractals” is dark and foreboding, with usage of Israeli scales. The strange, bubbling electronic world at times recalls Herbie Hancock's Mwandishi at their abstract best on the pivotal Crossings (Warner Brothers, 1972). The lengthy treatment of Massive Attack's classic trip hop opus of love and obsession “Teardrop” (also recently covered by Thana Alexa) allows Big Vicious to really stretch in a vast atmosphere. Ravitz' treatment of the iconic beat, gets additional assistance from Aviv Cohen and through improvisation, reversed sounds and distorted, delayed trumpet explore the psychological aspect of obsession and longing. The trumpeter cries out almost in anguish. Whereas Alexa's version faithfully captures the tale of sensuality and obsession, Cohen really plumes the psychological aspect and in his solo really flies in the upper register. “The Cow and The Calf” ends things on a note as cinematic as the album began, Cohen's trumpet states the reflective melody, then contrasts in the bridge section with a quasi boogaloo feel reminiscent of 60's Blue Note classics.

Sound:

Big Vicious' debut is filled with a ton of sonic ear candy and a huge sound stage. The drums of Aviv Cohen and Ziv Ravitz take up the far left, center left, right center and far right of the stereo image. The drums have a real deep percussive snap to them with Cohen often employing effect laden snares with tambourines on the drum heads, and other devices to simulate electronic drums acoustically, much in the domain of Mark Giuliana, Chris Dave, Antonio Sanchez and Eric Harland. There is also a satisfying dead drum sound here recalling that of classic 70's groups like that of The Eagles, or the Alan Parsons Project. A few cool moments appear on “Teardrop” with Ravitz' rim shots trailing off into reverb in the invisible center and stick drags from snare in the left channel translate to reverbed snare hits from Ravitz in the center channel. Odd, at times sinister synthesizers, guitars and effects are present throughout various areas of the sound stage, and Avishai Cohen's trumpet is brilliantly clear and realistic despite both subtle and heavier uses of effects. Manfred Eicher's production with a firm grip of contemporary trends results in a dynamically exciting recording that leaps from the Focal Chorus 716 floor standing speakers with accurately rendered tones.

Final thoughts:

Avishai Cohen with the debut of exciting new band, his golden, singing beautiful trumpet, and a wealth of collective musical experience is what makes Big Vicious a joy to listen to, start to finish. Cohen is a diverse musician that with his fourth ECM recording taps into yet another wellspring for different ideas. With relatively brief catchy tunes, blending the acoustic and electronic, with the current woes of contemporary society in a post COVID-19 world, this is the kind of recording that will appeal to traditionally non jazz listeners, and for some perhaps be a catalyst to dive into the enchanting back catalog of ECM records.

Music rating: 9.5/10

Sound rating: 9.5/10

Equipment used:

HP Pavilion laptop

Yamaha RS 202 stereo receiver

Musicbee library (for digital file playback)

Sony Playstation 3 (for CD playback)

youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

Journal Update #14 APR - Spider-Man

I arranged a session with my cousin Callum who brought a few of my uncle's old synths to the studio. Specifically the Arp Odyssey and Roland Jupiter MKS80, we worked for around two days creating new material for the tape.

It was cool to get him involved and this particular collaboration linked in with the themes of family connections and relationships explored on The Tape. My family has a lot to do with my early musical influence and my memories of jamming with my cousins are happy times. As we grew up and both started to specialise in different areas of music but we continued these ‘jam’ sessions usually me on drums and cal on keys, (see pic below) but usually for fun or when the time allowed. So it was great to actually collaborate for a project that will be released.

Callum is a talented multi-instrumentalist and all-round nice guy who specialises in piano (he currently teaches piano at a school). Cal has a great understanding of jazz, and I was able to learn from his knowledge on the keys and record multiple parts of him playing melodies and chords on synths. He contributed to the tracks Kick About, TOAST OF PARIS, Drink it Up and Spidey.

(Pictured above is the Arp Odyssey and the Super Jupiter MKS-80)

It was great that he bought these two of my uncles synths along, because they produced solidly fat, analogue, retro sounds and fed into the idea of nostalgia. Adding analogue ‘warmth’ to the beats was something that was important for me because I love the concept of noise and in particular I am a fan of Lo-Fi Hip-Hop. Although I would not describe the beats on The Tape as Lo-Fi Hip-Hop there are certainly some elements of the genre included like my use of the SP-404 effects and tape hiss. The Roland Jupiter’s “great sound is due in part to the classic analog Roland technology in its filters, modulation capabilities and a thick cluster of 16 analog oscillators at 2 per voice.” (Vintage Synth Explorer, 2017). The Arp Odyssey is a revolutionary analogue synth and I am glad to say it has featured on The Tape. The Odyssey is a “duophonic unit with two VCOs, most notable for its sharp sound and the versatile sound-creating possibilities” not easily available on other small synths of the time. With functions and modulation options such as oscillator sync, sample & hold, pulse width modulation, high-pass filter, and two types of envelope generator, it featured a rich array of sound-generating potential. The Arp Odyssey's signal path had a major impact on synth manufacturers that followed. It became the standard for subsequent eras, influencing even the polyphonic and digital synthesisers that were to come later. The Arp Odyssey was used by many great musicians including Herbie Hancock, George Duke and Kraftwerk (ARP, 2015).

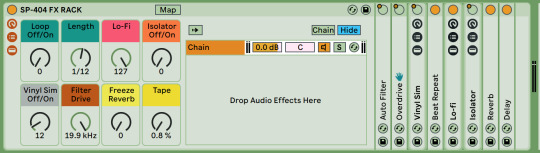

I made a special SP-404 emulation effects rack for use in live performances to market and create hype for Easy The Tape (pictured below)

What went well:

We created quite a few new ideas and also recorded multiple parts on more than one of my beats, which gave me a lot to work with and choose from. It was also good to learn from Cals knowledge on the keys. And because we knew each other creativity flowed and the session was productive.

What didn’t go so well:

Didn’t get as much done as I could have due to having too much fun in the sessions and getting distracted listening to music, playing Gamecube and watching old TV and films... to find samples though, all of which you can hear in the beat ‘Spidey’.

The Artwork for the track is pictured below.

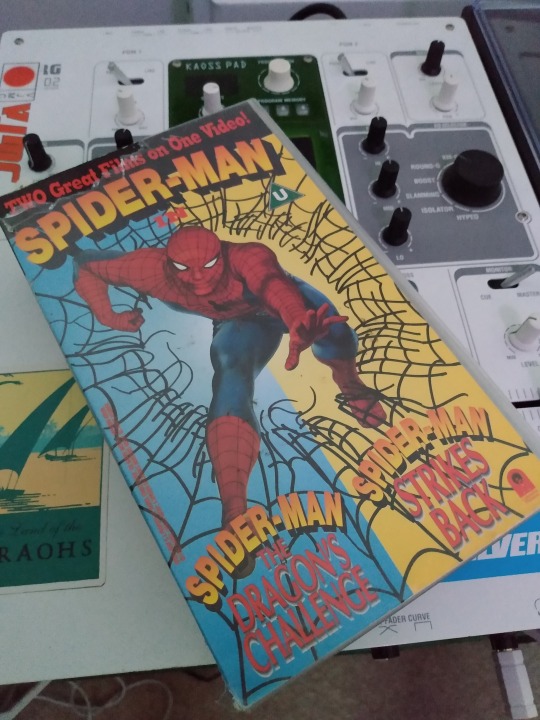

The main sample on Spidey is recorded directly from the original VHS of one of my favourite spider-man films when I was a kid (pictured below)

The use of sampling directly from VHS references not only the sample itself but the sonic characteristic it carries with it. This piece of technology is obsolete now and only used in a nostalgia inspired visual art or music, and sometimes as an effect for music videos that reference the nostalgic and ‘Lo-Fi’ aesthetic. Hopefully incorporating samples like this will evoke a nostalgic response in the listener with realising. In addition Multiple samples from vintage spider man cartoons of my childhood were recorded from Lo-Fi (obsolete technology, such as VHS and DVD). I remember being so excited to wake up on Saturday morning and sit in front of the massive flickering box in the front room with my cheerios for double bills of Spider-Man: The Animated Series. When I think about it now it brings back happy memories and it has a lot to do with that ‘Lo-Fi’ aesthetic, the flicker of the CRT screen which always seemed giant compared to little me and the crunchy nature of the sound coming out of the low budget TV speakers... simpler times. Hopefully listeners will get these same feelings when listening to the beat.

Once I’d finished a first mix on Spidey I showed the track in one of our production showcases for feedback

Feedback on the first mix of ‘Spidey’ from the peer review session:

Nick (tutor): The use of samples is great and the elements all work together and communicate well with each other. The stereo image is a little strange however. The snare feels too wide and leaves a gap in the centre. The kick is central and acts as an anchor to a point but there isn’t any central information in the mid range, which is needed. It’s ok to have the wide information with the snare but consider layering this with a mono version of the snare to give focus whilst also sounding wide. I also think the distorted bass sound should be in mono and the piano sample should be more central. Overall the mix seems lopsided towards the right, so some attention towards balancing out your panning is necessary.

Nice placement of all the elements of the track sounds tight and professional, although feel parts are possibly a little dry and could move about a little more to fill spaces that sometimes feel a bit empty, vocals are cool!

Production sounds great, the structure is all there, maybe the backing sample (horns and keys) could come up in the mix a bit more?

Real nice stereo spreadage, could even play with that as the track develops? Really like the subtle pad in the second half. Real nice velocity control on the drums and stuff, sounds smooth as a babies bum. Mix sounds pretty tasty too.

NY/Parallel compress those intro vocals. Beat is nice and breathy though.

This is ace. Really great use of the chosen samples. Maybe spread out a bit too much.

Kick is really punchy and clean! Maybe some saturation and stereo spread of the hats. Overall sounds really nice, good mix.

Drums sound really nice, the stereo spread on the snare works well although there could be a layer in mono.

This track reminds me of some of the songs included in the Baz Luhrmann production of Great Gatsby - mainly "No Church in the Wild" and "Ni**as in Paris" by Jay-Z. Not sure if he's an influence but it might be interesting listening to some of the production techniques he uses to enhance the mix of this track.

I think it's great and has a strong foundation.

Really great track! Love the way you’ve played with the stereo field although the hard pan of the piano sample feels a bit extreme for me. Texturally it sounds great and got me rockin’!

Above is a picture of just an excerpt of my large spidey comics collection. I started collecting around 2006/07, and if I remember correctly the right comic is the first issue I ever bought, the left is probably my most prized comic in that collection, 30th anniversary edition... nerd...

References:

Vintage Synth Explorer. (2017). Roland MKS-80. Retrieved 2020, from Vintagesynth.com website: http://www.vintagesynth.com/roland/mks80.php

ARP. (2015). ABOUT | ARP. Retrieved 2020, from ARP - The Legendary Analog Synthesizer website: http://www.arpsynth.com/en/about/

#family#work#beats#studio#arp odessy#synth#synths#jazz#the tape#spider-man#spidey#beat#easy#easy green#tape#comics#production#session#feedback

0 notes

Text

Le Guess Who? 2019 - Here's what to look out for

Le Guess Who? Festival kicks off its 4 day celebration of genrebending, boundary crossing music from across the world. If you're lost in the clashfinder and not sure who to prioritise, here's some of the top names to look out for, with descriptions provided straight from Le Guess Who?...