#but it still had the original install from 1999

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

well, the new monitor doesn't seem to want to display any picture, i can hear it degaussing when i power it up, but then nothing. it's a multisync with a few different inputs so i might have something set up wrong there or it might just be my cable or something, but im not super sure yet. on the upside, it looks good on my desk and serves as a great place to stick all my tiny robots, so like, def not a complete loss there at least!!

#the imac i got worked first try and seems to be in great shape#besides a dead optical drive but that's fixable#and the drive is old enough that it makes me a bit nervous#but it still had the original install from 1999#files mostly untouched since 2002 and control panel shows that the last time it connected to a time server was in 2007#and it's got all sorts of stuff installed#documents folder was wiped but still some adobe stuff and a couple varieties of napster and like 3 or 4 different internet utilities#and the website listed in the photoshop registration is still live and everything#really cool piece esp for only like $30#and the color matches the clamshell ibook we already have too#good day at vcf today!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apollo’s Chariot( BGW) and Nitro (SFGradv) side by side

Only built two years apart, Apollo’s Chariot has a pre-drop while Nitro was the first B&M hyper to not have one. Definitely a big size jump from 170ft to 230ft, Nitro dominates the skyline while Apollo is barely half that height. Apollo is still considered a hyper coaster since that term describes any coaster over 200ft elevation wise. Apollo’s Chariot’s first drop falls into a ravine of the Rhine River, adding an extra 30 feet to the drop, therefore, Apollo’s Chariot being deemed a hyper coaster. It’s B&M’s first hyper coaster installment so Apollo’s Chariot is a prototype. The ride has been running strong for well over 25 years now and I’m glad he’s gonna be running more years to come! Busch Gardens Williamsburg celebrated Apollo’s 20th birthday in 2019 and even gave him a fresh coat of paint making him look as gorgeous as he did in 1999.

Nitro had yet to get that special paint treatment, but his trains has, even including a fourth train. Nitro’s color scheme is very 2000’s and if they repaint him, I hope it’s the same colors. Going back to the two hypers side by side, Nitro’s support columns are A support structured and create a triangle look at the top of the crest as the track goes strait down at a 65 degree angle. Apollo’s Chariot also has the A support structured columns but they aren’t like Nitro’s set up placement wise. Apollo had two A support columns that one, holds up the top of the lift and the other holds up the crest/pre-drop.

Regarding color scheme, Nitro has magenta railings, blue support columns and yellow track. Apollo’s Chariot has purple track, yellow support columns and grey railings on the track.

Train Color:

Apollo’s Chariot trains are Red with Black seats(four across) with some purple and gold as well as a custom zero car cover with the Original Busch Gardens Logo on the front.

Nitro’s previous train colors use to resemble his structure colors, however, later changed to blue and black.

All photo’s are mine except this one of Nitro’s original colors.⬇️

#roller coasters#busch gardens#six flags great adventure#apollos chariot#Nitro Six Flags#busch gardens williamsburg#hyper coaster

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

OK! In an attempt to move on from those asshats, how about you give us some more nuclear facts? Assuming you're still interested in that topic.

(Also Jeffrey Wright is obviously the far superior Jim Gordon. No shade on Goldman but come on)

Sure thing! :D

So back in December 2001, 3 men 50km from Lia, Georgia (the country, not the state) came across 2 metal cylinders in the middle of the forest. They noticed that the snow was melted around the cylinders and decided to use them as heat sources when they camped for the night.

What they didn't know was that these cylinders were actually radioisotope thermal electric generators a.k.a. RTGs.

RTGs carry extremely radioactive material meant to generate electricity via radioactive decay. We actually use RTGs for spacecraft or remote areas like the Arctic. The Soviet Union was even using RTGs to power lighthouses and navigational beacons.

The Soviet Union had created 8 of these RTGs full of strontium 90 (a man-made radioactive isotope with many uses from medical studies to space stations, and a half life of 28yrs) in order for Georgia to better power their relay stations and the Khudoni Dam (which was meant to generate electricity to areas without power) throughout the country.

I believe it was in 1983 or 1984 when they made these, but don't quote me on that.

HOWEVER.

Before the RTGs could even be installed, Georgia gained it's independence from the Soviet Union (8 months before the fall of the Soviet Union). So the RTGs and the Khudoni Dam were temporarily abandoned as a result.

When the Soviet Union fell, orphan sources ("self-contained radioactive source that is no longer under proper regulatory control and poses an immediate radiological threat") were left behind without any warning signs or protection. Orphan sources can be anything from an abandoned RTG, medical equipment, to a nuclear warhead.

Just in case it wasn't clear, orphan sources are not a strictly Soviet Union thing. There have been many unfortunate cases of orphan sources killing people from all over the world.

4 of the 8 abandoned RTGs meant for Georgia were found between 1998-1999 and were safely discovered and removed.

Which brings us back to the 2 RTGs discovered in Lia in 2001. The 3 men were originally looking for firewood when they came across the 2 abandoned RTGs. By the time they discovered the RTGs, it was already really late in the evening so the men decided to make camp instead of traveling all the way back to Lia and decided to use the RTGs as heat sources.

Keep in mind, the men had no idea that the metal cylinders they found were RTGs. They were in the middle of the forest in extremely cold temperatures and were simply looking for a suitable heat source to keep them warm until they could go looking for more firewood again in the morning.

Unfortunately, one of the men tried to picking it up one of the RTGs with their bare hands and dropped it immediately because of how hot it was. They dragged the RTGs with some metal wires to their camp and sat with their backs touching the RTGs while they ate dinner.

Within a few hours they were vomiting. When they woke up the next morning, they were so dizzy and weak that they could barely load up even half of the firewood they had originally gathered up. Still not knowing that their heat sources were RTGs, 2 of them created packs to carry the RTGS on their backs as they continued to make the trek through the forest for hours in an attempt to try and find the additional firewood they needed.

Eventually, they abandoned the RTGs, but by then it was far too late. For weeks their symptoms persisted and grew worse until their families notified the local authorities of the men's conditions. They were, of course, immediately hospitalized.

If you weren't aware already, radiation breaks DNA down on the atomic level which leads to cancer, cell mutation or impaired function of the body's cells and organs. White blood cells, our body's natural defense mechanism, can't fight off any infections because the radiation straight up kills them. As a result, wounds don't heal and it's incredibly difficult to treat them.

I'll spare you the gory details.

One of the men died from cardiac arrest and multiple organ failure after 893 days of exposure to the RTGs. Another man recovered and was discharged from the hospital after 490 days of exposure. The third man was released early as his injuries were mild in comparison to the others after only 52 days of exposure.

Fortunately, the IAEA a.k.a. the International Atomic Energy Agency was quick to get involved once Georgia's government reached out to them for assistance. They were able to successfully remove the abandoned RTGs and even came back in 2003 to extensively search the rest of Georgia for any other potential orphan sources.

They found 300.

As far as we know, 2 of the remaining 8 RTGs are still missing to this day.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

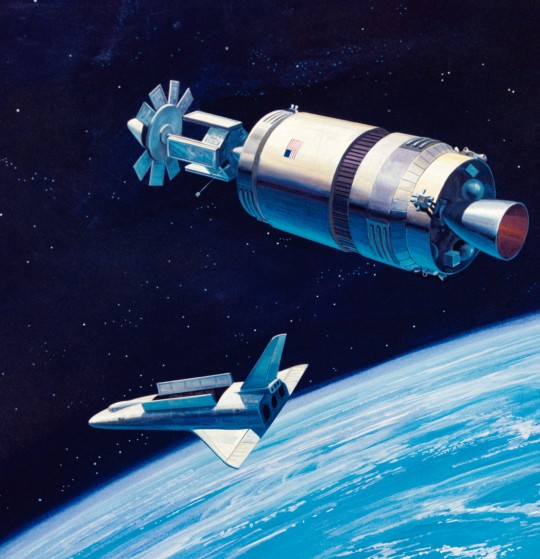

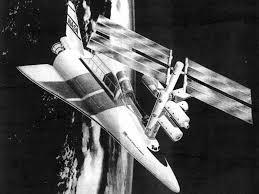

Space Shuttle Development, Phase B: North American Rockwell and General Dynamics B9U/NAR-161-B

North American and General Dynamics B9U / NAR-161-B proposed their final Phase B shuttle proposal on June 25, 1971.

"The fully reusable 'B9U / NAR-161-B' configuration would now weigh 2,290t at liftoff vs. the Phase-A limit of 1,587t and the total estimated cost of the development project had doubled, to almost $10 billion. The thrust of the space shuttle main engines had to be increased from 1,850KN to 2,450KN. Part of the problem was the shuttle now would have to be a much more versatile and capable vehicle than originally anticipated, since the space station and the manned lunar/planetary program evaporated in 1970. Critics in Congress contended that it was 'a project searching for a mission.' As a result, the new space transportation system was instead increasingly being promoted as a low-cost 'space truck' for unmanned NASA & USAF satellites."

"The North American Rockwell 'NAR-161-B' orbiter was designed for carrying a crew of two plus up to ten passengers in the forward crew module. Note the four deployable landing jet engines on top of the vehicle; NASA was planning to use modified F-15 or B-1B aircraft jet engines on some missions and for ferry flights from test sites or alternative landing fields. But the jets would be omitted for heavy-lift missions since the additional weight greatly reduced the shuttle's payload capability. The thermal protection system was based on silica tiles. The blended wing/body design was chosen for uniform load distribution. It would have produced a 2300-kilometer crossrange capability to satisfy USAF reentry requirements; North American also decided to replace the wingtip fins with a single vertical tail. The 2,450KN main engine thrust upgrade was motivated in part by the need to have a single engine-out abort capability. Analysis showed that the orbiter still would be able to return to the launch site after a single orbit in case one of its two main engines failed during ascent, but only if the engines were powerful enough. Unlike McDonnell-Douglas (who proposed to use RL-10s), North American favored a brand new oxygen/hydrogen 45KN-thrust orbital maneuvering system (OMS) engines. Three OMS engines would have been carried for orbit insertion, orbital changes and the de-orbit burn."

"General Dynamics' final 'B9U' booster design differed considerably from the earlier straight-wing 'B8D' concept. The landing jets were moved from the nose back to the delta wing in order to reduce the launch drag & heating effects and to minimize the jet engine exhaust effects on stability, control and drag. General Dynamics felt the delta wing would provide better stability & control over the entire flight regime than the B8's straight wing. It would also create more room for the main landing gear and jet engine installation. The gross liftoff mass was 1,886.2t including a jet fuel load of 62.2t for the 850km flight back to the launch site. The high staging velocity (3300m/s) and altitude (73.8km) created some problems since the booster would have to be very large, require a relatively advanced thermal protection system and carry lots of jet fuel for the return flight. The contractors also examined downrange landing sites or in-flight propellant transfer in order to reduce the amount of booster jet fuel. NASA also seriously considered a proposal to use gaseous hydrogen rather than jet fuel since it would have saved thousands of kilograms, but decided against the idea in the end since it would have increased the technical risk."

North American Rockwell Phase-B shuttle orbiter docks with modular space station.

"Payload capability (without landing jets): 29,484kg into a 185km 28.5 deg. Orbit; 18,144kg into a 185km 90 deg. polar orbit; 11,340kg into a 500km 55 deg. orbit with landing jets installed on orbiter and 20,411kg without landing engines.

Cost per mission: $100-200/lb. [1970 rates] or $950-$1900/kg in 1999. 75 missions/year max. Space station rescue mission capability within 48 hours of emergency call.

Liftoff Thrust: 2,606,810 kgf. Total Mass: 2,188,488 kg. Core Diameter: 10.4 m. Total Length: 98.0 m.

Stage Number: 1. 1 x Shuttle R134C-1 Gross Mass: 1,886,200 kg. Empty Mass: 290,000 kg. Thrust: 29,370-32,233.575 KN. Isp: 442 sec. Burn time: 209 sec. Isp(sl): 392 sec. Diameter: 10.4 m. Span: 43.9 m. Length: 82 m. Propellants: Lox/LH2 No Engines: 12. SSME Study

Stage Number: 2. 1 x Shuttle R134C-2 Gross Mass: 383,260 kg. Empty Mass: 121,560 kg. Thrust (vac): 5,624.8 KN. Isp: 459 sec. Burn time: 264 sec. Isp(sl): 359 sec. Diameter: 4.6 m. Span: 32.6 m. Length: 62.8 m. Propellants: Lox/LH2 No Engines: 2. SSME Study

- information from "INTRODUCTION TO FUTURE LAUNCH VEHICLE PLANS [1963-2001]" by Marcus Lindroos: link

SDASM Archives: 08_00941, 08_00943, 08_00944

Mike Acs's Collection: link, link

Numbers Station: link, link, link, link, link

source

Boeing image: 71SV13043

#Space Shuttle Development#Phase B#North American Rockwell General Dynamics B9U/NAR-161-B#North American RockwellNAR-161-B#NAR-160-B#General Dynamics B9U#concept art#Space Shuttle Phase B#Space Shuttle#Orbiter#NASA#Space Shuttle Program#June#1971#B9U#my post

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Attempted Breaking by Talking and Some Armor Piercing Questions"

Summary: After the "black wedding" has been stopped, Ashley finds out who the "higher power" is and the latter tries to break her spirit. Then she has some important questions for the Undertaker. 30th instalment of Two Brothers, One Friend, Many Stories series. Kayfabe details used only.

Disclaimer: I don't own any of the pro wrestling gimmicks/characters used here. I only own my original characters.

It was April 26th, 1999, one day after Backlash. Steve Austin had stopped the "black wedding" between the Undertaker and Stephanie McMahon while X-Pac, despite being blamed for the "blood bath" that he and Kane had been given by the Brood, tried to break into the dressing room of the Ministry of Darkness to free Ashley. The second thing had not gone well; the "higher power" had snuck up on the man and knocked him out.

Ashley had been left sitting in the dressing room alone with just a closed circuit TV to show what had been going on in the ring; she wasn't tied up and thus had been able to go and use the bathroom in that room. She couldn't escape though and she had been losing hope for quite a while now. Things were about to get worse as the man who claimed to be the "higher power" opened the door and entered the room. His face was hidden by the hood on his red robe and yet Ashley had the sense that he had an evil smile on said face. Raw had just gone off the air but there was still a camera man present to film the conversation to be shown at a later time on WWF TV.

The single mom glared at the hooded figure in front of her. She didn't know what to say.

"I should have realized that Kane would try to get someone else to play the hero and rescue you, Ashley McCormick." The man said to her. "Who would have guessed that a big red monster was capable of finding loopholes?" He removed his hood, ready to reveal his identity. It was being done much earlier than planned but it would serve a purpose of helping to break her spirit.

Ashley stared in horror at the man who had claimed to be the higher power to the Ministry of Darkness. "Jackal?!" She didn't know what else to say. Why did he brainwash the Undertaker? What was the point of the cult leader wanting to take over the World Wrestling Federation? Why use her to send a message of what would have been in store for Stephanie McMahon had Steve Austin not rescued the youngest child of Mr. McMahon?

"Who were you expecting, someone from the McMahon family?" The Jackal asked her, sarcasm lacing his voice. He returned to being sincere. "I told others of my plans to take over the World Wrestling Federation many times before, but no one thought I could do it! I brainwashed the Undertaker as a favor to Paul Bearer to bring the Deadman back to the dark side after he had been moving away from there for too long in exchange for help bringing my plans to fruition. It was easy to do because of his hatred for Steve Austin! You were one of the innocents targeted because Paul wanted to torture you with the knowledge that your childhood friend can never be how you prefer to remember him, as is the case with his beloved little brother. I also wanted to show the masses exactly what I am capable of!"

"You fucking, evil bastard!" Ashley shouted angrily, getting up from the folding chair she was sitting in. She was about to punch him in the face with her left hand as she walked over to him.

The Jackal grabbed her wrist. "And I'm proud of it! Pity you reverted to being as impulsive as you were in childhood; I could easily break your wrist. Breaking your spirit will suffice though!" He let go of her and then left the room to get the Undertaker; X-Pac had been taken to get medical attention by now.

Ashley had no idea what to do now; there was only a small amount of comfort in the fact that the Undertaker hadn't been acting of his own free will. Was there a way to break him free from that control though?

The Undertaker had returned to the dressing room a few minutes later with the rest of the Ministry of Darkness to take Ashley with them on the road to the next arena. They did let her have a bathroom break before leaving though as there was no window in it for her to climb out of. Once she was tossed into the backseat of a rental car once more, Ashley fell asleep since she didn't know what else to do. Tomorrow night, a pilot episode of a new WWF TV show would be filmed and then aired on Friday. She wanted to get free that night if at all possible; she was not going to let what the Jackal had said get to her.

It was the very next night when something unexpected happened. Halfway through the filming of what would eventually become the first episode of Smackdown, Ashley McCormick had been left alone with the Undertaker backstage in the locker room of the Ministry of Darkness. The Jackal had left them like that in the hope that the single mother would be too broken emotionally to try to get the Deadman to see reason. The cult leader seemed to think that even if she did try, she would fail. Assumptions are dangerous things though and can be proven wrong.

Ashley had never begged anyone for anything ever; she was desperate enough to do that now though despite being tied up once again. "Please stop this, Mark! There have been too many people that have suffered because of what you've been doing! I'm worried about them and you! I don't care what kind of torture is in store for me for doing this! I will still try to get you to listen to reason because you are my best friend and I don't want to lose you." She then had some questions for him as tears started running down her face. "Do you even know what you'll do next if you succeed in taking over the World Wrestling Federation? Why should you listen to the man claiming to be your higher power? Do I deserve to be kept from my children, especially when they and I didn't do anything wrong to you or him? Maybe things can't be the same as when we were kids and I've known that for a long time! The Mark I know now, whether he is the Undertaker or not, has to still be in there somewhere! Is he though?"

The Deadman did not seem to have an answer to any of those questions. It was as if he had been metaphorically pierced by them as he looked at his best friend.

Neither one had noticed that the rest of the Ministry of Darkness had entered to witness what was occurring. It seemed that like their higher power, they felt that these efforts of Ashley to try to get the Undertaker back to himself wouldn't work. Those watching at home and those in the audience at the New Haven Coliseum weren't sure what to think either. All of Ashley's family had been praying for her, the Undertaker, and Kane since the Ministry of Darkness had officially been established though and had not lost hope. These prayers were about to be answered.

It wasn't the tears or the begging alone that had broken the brainwashing spell cast by the Jackal and Paul Bearer as the Undertaker rolled his eyes up briefly to reveal the whites and then removed his hooded robe. It was the fact that both had come from a genuine place of concern for others involved in the whole situation and Ashley's willingness to go through Hell by trying to get him back in control of himself. Memories of times that Ashley had been there for him flashed through the Undertaker's mind as he choke slammed Bradshaw onto the floor. He didn't seem to know how he had ended up here, only that his best friend was in danger as he tried to untie her. Everyone else attacked him and Paul Bearer screamed "Nooooo!!!"

Kane immediately ran in once he noticed the door unlocked to help as he had been passing by. Unfortunately, the numbers game was still against the future Brothers of Destruction as they had to retreat and wound up in a different backstage area, that being where the main locker room was.

"What the Hell is going on here, Kane?" The Undertaker asked, worry made obvious on his face before a janitor appeared.

"Find a TV with a VHS player and some tapes from the last few months! I need to show my brother what he did!" Kane demanded, the frightened janitor running off to do so without question. The big red monster then dragged the Phenom into the locker room. "You were brainwashed by the Jackal and Paul Bearer and put a lot of people in danger, big brother! Especially our best friend!"

The Undertaker had no reply as he found his cell phone. He read the text messages that Ashley had sent expressing worry about what he and the Ministry of Darkness had been doing and played several voicemail messages while waiting for the equipment Kane had requested to be brought in. One voicemail message put him on the verge of tears. The message was from March 24th, 1999, and how it was still there after a month was a mystery. The content was Ashley saying "Hey Mark, I hope you come to your senses soon. Just wanted to wish you a happy birthday." Then she had sung "Happy Birthday" to her best friend, struggling not to cry while doing so. That was when the message ended.

One moment later, the TV and VHS player had been brought in and hooked up and the tapes handed to Kane. Once he and his brother had been left alone once more, he started playing the tapes after turning the TV and VHS player on. One thing that the Big Red Machine noticed was that the Undertaker was becoming more and more horrified at what he was seeing, especially when he realized that he had targeted so many innocents, Ashley included, and he remembered his best friend's warning: "If you don't drop your hatred for Stone Cold Steve Austin, you'll do something you'll likely regret later!"

"Kane, what did I do? Her parents are going to kill me for this." The Undertaker looked down in shame, tears of guilt threatening to fall. Mr. McMahon would likely kill him for it as well. First, he had to go out and say something to the world. He quickly composed himself and anger that he had been made to be worse than he would willingly be became evident. "I am going to kill the Jackal first though!" He paused the VHS player and turned off the TV before leaving the locker room.

Kane was not far behind. "I want a piece of him too!" He shouted. It was needless to say that this confrontation would be very interesting.

#fan fiction#professional wrestling#wwe the undertaker#wwe kane#wwe the jackal#or jackyl#i don't know how to spell it#original characters

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

I assume youre not much of an oc type of person, but did you have any like backstory or smth planned for Rev Tal?

Oh buddy you have no idea how wrong you are about me not being an oc person. I have a spreadsheet of like 40-ish ocs. This here blog voidtongued used to be a full on warframe roleplay blog but. most of my rp parners went inactive in terms of the writing aspect (we still chat and play the game and talk about how much we miss role-playing from time to time but a lot of us are. adults with full time jobs now and it makes it difficult to do that)

ANYWAY. Short answer is yes. Long answer is beneath the cut lmao

Rev Tal is a Venusian-born Tenno, raised by people who would later become some of the first Solaris. They were on the Zariman Ten-Zero, and after the void jump accident their possible existences diverged into The Operator and The Drifter. Blah blah, events of the game story quests with some minor canon divergence (Rev Tal being far warmer to the Grineer in any situation because they recognize the average Grineer trooper as a brainwashed soldier and as much of a victim as they are, etc), and slowly began to develop an intense distrust bordering on hatred of The Lotus. After the events of The Apostasy Prologue, they effectively renounced the Lotus and became a full-time Arbiters of Hexis operative Tenno, preparing for the coming Sentient invasion.

Things... Changed after The New War, with the apparent death of The Operator, a rift opened to Duviri, where the Drifter had been. Drifting. Surviving. Trying to find a way out and back into the reality they were "originally" from. The Drifter learned how to navigate the Void's reality and unreality, and has had dealings with the Murmur that left them changed and bitter. During the events of The New War, the Drifter and the Operator met face-to-face and realized that they were technically two parts of a whole individual, now styling themself Big Rev to differentiate from the child Rev Tal had been.

Big Rev is the best of both worlds - The Operator's energy and drive to succeed tempered by The Drifter's perspective and adult emotional maturity.

I've written two fics on ao3 from. forever ago. regarding Rev Tal's story - How to Make a Martyr and Voidtouched. HTMAM was written after I finished the Sacrifice iirc and was determined to un-fuck the in-game depiction of Rell and TMITW in Chains of Harrow, and Operation Hostile Mergers was the impetus for me writing Voidtouched (iirc Hostile Mergers dropped like, while I was writing it and I went back and reworked some things? it's been like three+ years i do Not remember). I was gonna write more, but I got busy with school and life and my brain, computer, and hands decided to explode and I had to take an extended break from the game. I'm back now though, and very behind, and I keep toying with going back to what was going to be the third installment in Rev Tal's story, the Guardian's Song, which would've gotten into their backstory more formally, but with the number of things that have changed with TNW and the Duviri Paradox and now Whispers in the Walls and eventually Warframe 1999. I'd have to do a LOT of reworking and i dont. wanna.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Monolith Soft’s Future Was Redeemed

Whether you’ve heard of game developer Monolith Soft before or not, if you’re into the gaming landscape they’re definitely a name worth remembering, and they’ve had quite the history over their 23 years in the business. Founded by Tetsuya Takahashi and Hirohide Sugiura, themselves veterans of Square from the 1990s, the company has undergone many trials and tribulations and worked with a variety of different companies from 1999 to the present day. With their latest release wrapping up the current trilogy in the Xenoblade series, I figured there was no better time than to look back and reflect on the journey the company and the founders of that company have gone through, so let’s get right to it!

TAKAHASHI’S PERFECT WORKS

Looking at Takahashi’s resume alone will show that he had a hand in a variety of beloved games during his time at Square. Working on Final Fantasy IV, V and VI among a few other titles such as Romancing Saga, Takahashi and his wife, Soraya Saga, would pitch an idea for the seventh Final Fantasy game. While rejected for being considered too dark for the brand, they were eventually given permission to develop it into their own title, which would become known as Xenogears. Takahashi and Saga had ambitious plans for the title, believing it could become a massive franchise in its own right, though the actual game’s development was fraught with issues.

Xenogears was composed of two discs, and the first disc set up lofty expectations for the rest of the game, balancing a story steeped in religious and philosophical themes alongside turn-based battles that would utilize giant robots, or “Gears.” However, the second disc was mostly comprised of narration from characters with hardly any gameplay or cinematics. This was allegedly done as a result of both the development team’s inexperience and inability to extend the two year development deadline, and thus was done as a compromise of sorts, or else the game would have shipped half-complete. The game’s English localization almost didn’t happen, with several translators quitting the project, both due to the difficulty of translating a game loaded up with references to various scientific and philosophical concepts, on top of controversy surrounding its religious themes. Despite these setbacks, the game was still critically acclaimed and it was clear that Takahashi and Saga were keen on developing the game’s world more. Alongside development of Xenogears they had also crafted “Perfect Works,” their plans for other installments in the setting that would span a much larger story. Xenogears itself was considered, chronologically, to be the fifth part of what would have eventually been six entries.

However, Takahashi and company had routinely faced issues with Square both before and during development of this title. Growing frustrated with their prioritizing of the Final Fantasy brand above all else, they would eventually found Monolith Soft, taking with them a number of other staff they worked with. They found themselves in bed with Namco, who would publish their games for much of the 2000s. Monolith Soft would then decide to start over and craft a new franchise that would follow Perfect Works…and that game would become the Xenosaga series.

A more explicitly sci-fi series from the get go, Xenosaga was conceived as a six game series, with possible plans for it branching out into multimedia, with an animated series and manga series produced, alongside a few spinoffs titles that would end up staying Japan exclusive. A spiritual successor through and through, Xenosaga contained a number of references to the Xenogears series, alongside a continued focus on mech battles, religious and philosophical themes and turn-based combat. While the first game was a strong debut for this new franchise, each subsequent entry would sell less and less, eventually trimming the series down to three games out of its originally planned six. History repeated with regards to development issues, particularly with Xenosaga: Episode II, as Takahashi had taken on a supervising role, and the team itself was composed of newer staff that wasn’t prepared for such an ambitious title. Takahashi would admit the series underperformed on the whole, part of the reason for the sudden halving of the planned story. Despite a clean start, it seemed as if Perfect Works was anything but a perfect project, with now two failed franchises behind them. However, the winds of fate would wind up changing.

FINDING THEIR FOOTING WITH NINTENDO

Monolith Soft ended up cozying up with Nintendo as the years went on, eventually being purchased by the company and becoming a first-party studio in the late 2000s. Morale at the studio was low after Xenosaga’s abrupt ending, but Takahashi was ready to move onto a new project as a way to boost employee spirits. Coming from an image that appeared in his head of two gigantic gods locked in fierce battle, the idea would develop into a game originally titled Monado: Beginning of the World. However, at the behest of former Nintendo CEO Satoru Iwata, the title would be changed to Xenoblade, to honor the struggles Monolith Soft had undergone over the years and serve as a slight connecting thread to past projects. And the rest is history…to a point.

The original Xenoblade Chronicles debuted on the Wii in 2010, a massive near open-world RPG with a deep MMO-inspired combat system and an ambitious story. Compared to past efforts, Xenoblade was a game that Takahashi and company were able to realize with a comparatively smooth development, with few compromises to the original vision of the game at that. Releasing to relatively high critical acclaim, the game was initially not localized outside of Japan. Eventually Nintendo of Europe showed interest and would localize it, but Nintendo of America wouldn’t budge. This game, alongside a few others, actually inspired the “Operation Rainfall” fan movement to give them more attention and see localization (and I’ve even written about it before LINK HERE), and while Nintendo might not publically acknowledge the campaign as a deciding factor the game would eventually be brought to North America…exclusively in Gamestop stores. A low initial print, combined with Gamestop selling “used” copies at high prices, insured it became one of the harder to find Wii games, and while it was somewhat better known outside of Japan, it was still rather niche.

That began to change in the Wii U era, however. In a 2013 Nintendo Direct showcasing early looks at various Wii U games, a mysterious title from Monolith Soft was shown. Codenamed X, it was yet another massive RPG with a decidedly more sci-fi look…that sure seemed familiar. Eventually releasing as Xenoblade Chronicles X in 2015, this title would also see acclaim for its massive world and complex combat, though being a Wii U release it didn’t exactly reach many players. A year prior however, Shulk was revealed to be included in the base roster for Super Smash Bros. for Nintendo 3DS and Wii U, being the last character announced before launch. This helped to put Xenoblade as a series on the map, and gave some momentum that Monolith Soft would continue into the Nintendo Switch era.

Since their acquisition, Monolith Soft would also work as a support studio for Nintendo, particular with their Kyoto office comprised mainly of artists, creating assets for a variety of projects. Over the years, they’ve worked on the Super Smash. Bros. series (Brawl), the Legend of Zelda series (from Skyward Sword all the way to Tears of the Kingdom), the Animal Crossing series from New Leaf onward as well as the Splatoon series. Their help was greatly appreciated with the more recent console Zelda titles in particular, as they were instrumental in creating the vast expanses that would help make Breath of the Wild a smash hit. Considering they’ve lent their talents to a variety of games that have gone on to sell like hotcakes and break past previous franchise records, I think that really helped them prove their worth as an asset for Nintendo, and as such they are given license to continue their own ambitious projects.

At the tail end of 2017, the Switch’s debut year, we would get Xenoblade Chronicles 2, which would go on to become the best-selling entry in the series and experience a boon of new players. More in-line with the fantasy aesthetics of the Wii game, 2 also continued exploring similar themes and further developing the battle system shared across both previous games in the series. Despite its success, the game itself still ran into problems though. With much of Monolith staff working on BOTW it was mostly a skeleton crew on Xenoblade 2, resulting in a number of third-party artists being brought on to ensure the game could be completed, though that also led to complaints about the inconsistent art style and character designs. Technically, the game had issues at launch that were slowly patched out, and being the first simultaneous worldwide launch of the series, it was clear that the English localization was not given as much care as previous games. Despite this, it was clear that this title was what helped to establish Xenoblade as a core Nintendo IP moving forward, and the franchise continues to do well.

A BRIGHT FUTURE AHEAD

Following Xenoblade 2’s release, it would receive a prequel game as part of its expansion pass, Torna: The Golden Country, which fleshed out events happening in that game’s distant past, alongside polishing up gameplay to relative acclaim. In 2020, an enhanced port of Xenoblade Chronicles 1 would release on the Switch, with updated visuals (in particular polishing up the character models), and a new epilogue story, Future Connected. The heroines of Xenoblade 2, Pyra and Mythra, would be announced as playable characters in Super Smash Bros. Ultimate’s second Fighters Pass as well.

In 2022, Xenoblade Chronicles 3 would see a surprise reveal at the start of the year, releasing just a few months later. After the somewhat mixed reception of the previous game, 3 received rave reviews and several Game of the Year nominations. Many felt it to be an emotionally charged journey, once again spanning a massive world and containing complex combat to wrap it all together. In just a few years, the entire trilogy was now available all on one system. Not too shabby for a series initially struggling to get localized.

The major thing to remember with the Xenoblade series is that it was yet another fresh start for Takahashi and company. While still clearly its own thing, as the years went on many eagle-eyed fans would spot various references to past Xeno games. These often were seen as knowing winks and nods, but little else. When it came to various characters and story beats, there were also some connecting threads indicating that Takahashi, after all of these years, might finally be dusting off “Perfect Works” and starting anew again, after he had previously sworn it off and considered the ideas scrapped. One major change this time around however seemed to be based around making sure each individual game in the Xenoblade series would be a standalone tale that wouldn’t require playing previous entries. There were some connecting threads, yes, but ultimately each entry could stand on its own and fully realize a given theme or story idea without having to overtly connect into a larger narrative. And then Xenoblade 3’s story DLC happened.

Released at the tail-end of April 2023, Xenoblade Chronicles 3: Future Redeemed was yet another prequel campaign in a similar vein to Torna. Future Redeemed would cover events that occurred in the backstory for the base game, however this time around it became clear VERY quickly that this was where it would all come together. Without getting into the details of things, on top of being wary of spoiling this expansion after it just released, Future Redeemed ends up being the means to tie the trilogy together and end it on a satisfying note, with a conclusion that gave fans a lot of closure. Various theories were finally put to rest, though just as many have sprung up in the wake of that game’s ending.

It isn’t immediately clear just where this franchise, or Monolith Soft as a company, will be going next, but my gut tells me we have some great things in store. The core Xenoblade trilogy may be done, but Takahashi has gone on record stating he wants the series to continue for as long as he can do so. There’s still a lot of clear affection for their previous efforts as well. Xenosaga’s KOS-MOS and T-ELOS were guest characters in Xenoblade Chronicles 2’s expansion pass, and there have been more…overt nods to the series in general as time has gone on. There are rumors here and there that the series might return in some form. At the very least, I’m sure many a fan would be happy with simple ports to current systems, but we’ll have to wait and see just where Takahashi’s Wild Ride takes us.

In the end, I’m just happy to see that Monolith Soft has managed to turn out alright after all these years. I first became aware of them when, on a lark, I picked up a copy of the original Xenoblade. I was struck by that game’s scope and ambition and I’ve been a diehard fan ever since. Seeing just how much they’ve been carrying Nintendo into the Switch era, I think it’s only fair that they get the respect they deserve. On top of it all, it sounds like the company promotes a fairly healthy work/life balance, and their time with Nintendo has enabled them to see their visions through with few compromises. A win-win for all involved, really. Their own original entries might always be a bit niche and definitely won’t be everyone’s cup of tea, but I’m glad their ambitions are becoming more and more realized as time goes on. From humble beginnings in the trenches at Square, to now being a pillar of one of the Big Three game publishers, I can’t wait to see the heights that Monolith Soft can climb.

-B

#xenoblade#xenoblade chronicles#xenogears#xenosaga#perfect works#KOS-MOS#rex#shulk#elma#noah#mio#monolith soft#tetsuya takahashi#wii u#switch#videogames#blog#xb-squaredx

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Star Trek: Hidden Evil

Original Release: 1999

Developer: Presto

Publisher: Activision

Platform: PC

This was the first one that was a nightmare to get running. Even though it’s on GoG, it requires audio hardware acceleration to be turned off, which isn’t an option on Windows 11. In the end, I had to install Windows 10 on a partition to get it working. Was it worth it? Definitely not.

Hidden Evil starts out quite promising. You play as Ensign Sovok, a human that was raised by Vulcans and is the first human to have mastered the Vulcan neck pinch (which you use in the stealth sections of the game). He serves on a station near Ba’ku, that has discovered ancient ruins near where the Son’a are settling, and they have requested Picard to look into it.

Leaving the Enterprise E and everyone but Data behind Picard has Sovok take him to Ba’ku to investigate, although the Son’a soon start a rebellion.

The game is played form a stationary camera. The controls aren’t as bad as I expected, and worked well when mapped to a controller. Aiming isn’t easy, so you’ll just flail and spam the shoot button until you hit something. There’s a few basic puzzles, but most of the game is just roaming around, occasionally shooting things. There’s a lot of pointless back and forth and padding to the game – which is astonishing for a game that is shorter than Insurrection.

The plot starts to pick up when you discover one of the ancient beings: one of the aliens from The Chase. Then, just as things get interesting, she’s immediately disposed of and instead the real villain is revealed: a big organic blob that spews out insect soldiers. Given time, this thing could overrun the entire galaxy. Romulans take her and then you have two really boring missions aimlessly roaming corridors on a Romulan space station and the Enterprise E – somehow they made exploring the Enterprise boring (also, only Picard and Data still talk to you on the Enterprise).

Hidden Evil feels like a game that had big plans, but the developers didn’t have the budget to do what they want. As a result, it feels like they gave up on their own story half way through this short game.

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

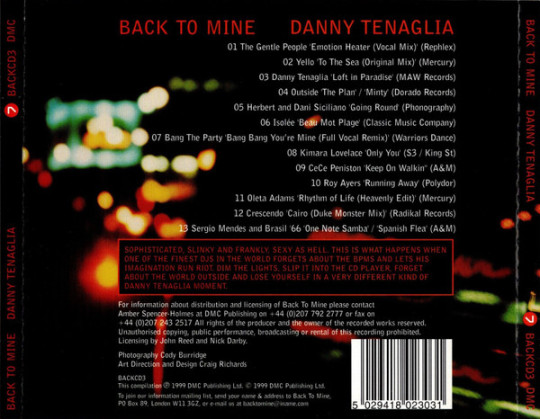

Today’s mix:

Back to Mine by Danny Tenaglia 1999 Deep House / Downtempo

Well, this was definitely quite something. New York's Danny Tenaglia is chiefly known as a consummate conqueror of the packed house dancefloor, but here, with this third installment in the DMC label's popular Back to Mine series from '99, the DJ delivers a compilation that's wholly unorthodox.

Back to Mine is known for presenting mixes that are of a chillout nature, but this is actually barely a DJ mix or a chillout release. It's basically a jumbled up mess of songs, from the 60s through late 90s, that express Tenaglia's very own eclectic taste in music as it extends past the nightclub.

Guardian Critic Alex Petridis tries to gussy up this CD in the liner notes, showering it with ebullient praise by describing it as both slinky and seamless, but this feels pretty charitable on his part, because there's almost no cohesion between any of these selections and the transitions are almost nonexistent; a carefully crafted DJ mix this most certainly is not.

But that's okay, really, as long as you understand what this release actually is, which is a seemingly random scattershot of some of Danny's personal favorites.

Now, the heading in this post might feel a little bit misleading, because I've only classed this "mix" as being both deep house and downtempo, when in actuality, it's a bit more than that. But when I decide what genres to include in those headings, I only list the genres that have at least two songs to them, unless the release is too short or eclectic to do that, in which case, I list every genre that appears on the release, which is a pretty rare occurrence anyway.

So, while this CD has a few deep house and a couple downtempo cuts on it, it also has some vocal breakbeat-chill from Yello—evidently, that quirky electronic duo from Switzerland that gave us hits in the 80s like "Oh Yeah" from the Ferris Bueller soundtrack and "Bostich" still had plenty left to contribute in the late 90s—delightfully classy mid-90s acid jazz from UK group Outside, an innovative late 90s funky microhouse cut from Isolée, soulful mid-90s garage house from New Jersey's Kimara Lovelace, the second biggest hit of Ce Ce Peniston's career in her 1992 dancy R&B bop, "Keep On Walkin," a late 70s disco-funk classic from Roy Ayers, a mid-90s edit of the debut soul single from Oleta Adams, and a nice and fun piece of bossa from Sérgio Mendes & Brasil '66.

*panting*

See what I mean? A totally discombobulated smorgasbord of music here; like throwing a long playlist of your favorites on shuffle and plucking out the first 74 minutes and then putting some rudimentary effects on it.

So, there's some really wonderful music on this album that spans a bunch of different genres and decades, but don't expect any of it to sequentially make much sense, because there doesn't appear to be any kind of thoughtful narrative here; it's just a bunch of songs that Danny Tenaglia's a personal fan of, from obscure to popular. All in all, it's worth listening to because the songs are good, but if you think you're getting a different type of Danny Tenaglia set here, you're not. because you’re not getting a set at all. He even admits it himself in the CD booklet, but back in '99, you'd only learn that fact after removing the plastic-wrap from the jewel case, which presumably happens only after you've purchased the CD itself 😉. And given that the previous volume in this series from Dave Seaman was an actual chillout DJ mix, from a guy who's not known for chillout mixes, I can see how a bunch of people would end up with buyer's remorse from this release, because of its lack of coherence.

But it's still ultimately a good time once you come to understand it for what it is!

Listen to the full mix here.

Highlights:

Yello - "To the Sea (Original Mix)" Danny Tenaglia - "Loft in Paradise" Outside - "The Plan/Minty" Isolée - "Beau Mot Plage" Bang the Party - "Bang Bang You're Mine (Full Vocal Remix)" Kimara Lovelace - "Only You" Ce Ce Peniston - "Keep On Walkin'" Roy Ayers - "Running Away" Oleta Adams - "Rhythm of Life (Heavenly Edit)" Crescendo - "Cairo (Duke Monster Mix)" Sérgio Mendes & Brasil '66 - "One Note Samba/Spanish Flea"

#deep house#house#house music#downtempo#dance#dance music#electronic#electronic music#music#60s#60s music#60's#60's music#70s#70s music#70's#70's music#80s#80s music#80's#80's music#90s#90s music#90's#90's music

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

If "Nightmare Ned" was featured/promoted at Disneyland and Walt Disney World at the time

On this day, the nighttime musical spectacular, "Fantasmic!" made its way to Disney's Hollywood Studios (AKA, "Disney's MGM Studios" at the time) at Walt Disney World in Florida. A year before that, the PC game, "Nightmare Ned" was released on CD-Rom for Windows 95.

While the game itself is considered "obscured" or "a hidden gem", whatever you call it, I feel like this game would've had better marketing if it was advertised at the Disney Parks.

For instance, at Downtown Disney, or whatever large spot of land was affordable at the time, there would be this tent where visitors could try the game out on Windows computers that have the game pre-installed (kind of like what E3 does for games being presented at a specific booth). And for two months only in 1997, Walt Dohrn and Donovan Cook would've been available for signing autographs for the PC game's box cover. Another part of the tent would've also sold yo-yos like the one Ned uses in the game for attacking monsters and ghouls, or to solve in-game puzzles.

And then there's Ned, our 10 year old titular character who has all these delusions and gets overwhelmed very easily. Ned would be a mascot character who would've had character meet-and-greets from 1997 to either 1999 or 2000. Because of this, "Fantasmic!" would've had a temporary revision (at least in the California Disneyland) where Ned would've made a guest appearance in helping Mickey (in his famous "Sorcerer's Apprentice" outfit from "Fantasia") fight off the Disney Villains, including his monster self from the good ending of the game. Courtland Mead (the original voice of Ned) and Wayne Allwine (who voiced Mickey until his death in 2009) would've still been available to record new lines for Ned and Mickey just for this temporary revision. A way to advertise this (at least in the case of Disneyland in California) would be that you could meet Ned during the daytime, and at night, the love Ned got from the guests would encourage him to face his demons with Mickey.

I don't know where Ned would've been located, even if he ends up as a meet-and-greet character at the Magic Kingdom, but regardless, I have some ideas in terms of what interaction tips would've worked. If I had to guess, interaction tips would've included talking to Ned about a nightmare you had to help relate to him, or something like that. And in terms of photo tips, one idea that would've worked would be if you and Ned hugged for the camera or if you had a yo-yo, maybe pose like you're gonna attack one of the enemies from the game itself.

This is all I got, but that's how I would imagine "Nightmare Ned" being promoted at the Disney Parks. If anyone else as a better imagining of this concept, feel free to comment.

#321SPONGEBOLT's Ideas#ideas that could've happened at the time#what could have been#what could've been#Nightmare Ned#Fantasmic#Fantasmic!#Disneyland#Disneyland Resort#Walt Disney World#Walt Disney World Resort#Disney Parks#idea blog

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Fatal Fury: City of the Wolves' is back, watch the first trailer

It's time to dust off those combos and practice those special moves because "Fatal Fury: City of the Wolves" is on the horizon! Get ready to battle it out in the streets as legendary fighters collide once again. Who's your favorite character from the series? SNK Corporation has released a fairly short trailer for the new Fatal Fury, which is titled 'City of Wolves' and is still in development. The new Fatal Fury is real and it's already underway at the hands of SNK. The company has just announced that the latest installment in the saga, the first since 1999's Garou: Mark of the Wolves, will be called Fatal Fury: City of Wolves. The new trailer shows Rock Howard and Terry Bogard, two of the characters most loved by fans, and the voices of some of their most familiar faces. This fighting game series hasn't had a new installment for 24 years, so it's cause for celebration. The EVO 2023, and for this alone, is to be framed and worth remembering. Fatal Fury (known as Garō Densetsu in Japan) is one of SNK's most iconic fighting game franchises, and is the origin of some of the company's most recognizable characters, including Terry Bogard, Andy Bogard, Mai Shiranui, Blue Mary, Geese Howard, and more. Fatal Fury: King of Fighters debuted in arcades in 1991, and the latest installment, Garou: Mark of the Wolves, debuted in 1999. SNK's separate fighting game franchise The King of Fighters initially began as a crossover fighter for SNK's Fatal Fury and Art of Fighting franchises, and their characters have been mainstays in the long-running series until today. Read the full article

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 1999 romantic comedy Notting Hill, starring Julia Roberts and Hugh Grant, almost had a sequel-but the idea was halted in its tracks for an unexpected reason. Richard Curtis, the writer behind the iconic film, recently shared the backstory that led to Julia Roberts rejecting the concept. Speaking with IndieWire, Curtis explained if he ever considered doing sequels to his previous works. He said that he actually considered a sequel for Notting Hill but the storyline was not okay with Roberts. "I tried doing one with Notting Hill where they were going to get divorced, and Julia thought that was a very poor idea," Curtis explained. The movie would have seen the central couple of the film, Hollywood actress Anna Scott and bookshop owner William Thacker, go through the challenges of a turbulent divorce. Roberts did not agree to the dark direction the beloved characters were being taken and dismissed the concept altogether. U.S. Department of State from United States, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Unlike Roberts, her co-star Hugh Grant seemed slightly more receptive. In an interview conducted by HBO with their official Twitter account, in 2020, Grant teased the possibility of a second installment centered around Anna and William's union. He suggested a storyline that would explore “the hideous divorce that’s ensued,” complete with emotional turmoil. According to Grant, the sequel would include “children involved in tug of love, floods of tears, psychologically scarred forever.” “I’d love to do that film,” the actor quipped, showing his enthusiasm for revisiting the characters, albeit in a less-than-rosy scenario. The original Notting Hill captivated audiences with its heartwarming story of two unlikely lovers navigating the challenges of fame, class differences, and the complications of modern romance. Roberts played the glamorous yet relatable Anna Scott, while Grant charmed viewers as the affable bookshop owner William Thacker. Their chemistry, combined with Curtis's clever script, made the movie a blockbuster, and people and critics alike raved about it. A few might have been tempted by the idea of reliving those characters in a dramatically different context, but it is quite evident that Roberts felt very strongly that the premise of the sequel did not do justice to the legacy of the original. Although Notting Hill is a movie of its own, the very chance of the sequel, although minute, always raises fans' interest in it. Both Roberts and Grant have been talking against it, which has left the story of Anna and William frozen in their classic original. While some fans will wonder what could have been, Roberts' decision speaks for her commitment to preserving the magic of a story that made millions feel it. And while Curtis and Grant are receptive to new narrative directions, there is always the reminder of some creative risks often considered in film-making. At the end, Notting Hill is still a classic romantic comedy that is loved and appreciated because of its humor and those touching moments, its own charm, and endurance. As for whether or not there ever could have been a viable sequel, that's one that might be debated, but here is the thing: what actually is in the original. Read the full article

0 notes

Text

From Tekken 1 to Tekken 8

As many of you probably know by now, I am an avid gamer. Since childhood, I have immersed myself in the world of video games, with one franchise holding a special place in my heart: Tekken. Having played every instalment from the original 1994 release to the latest Tekken 8 in 2024, I feel compelled to share my journey through this legendary series and how the newest release brings back the nostalgia of arcade days while showcasing the series' evolution over three decades.

Tekken (1994)

My love affair with Tekken began in 1996, when the first game hit the arcades in 1994 I was only one years old. The groundbreaking 3D graphics and the unique roster of characters instantly captivated me. I have many vivid memories on my PS1 playing the game. Each fighter had a distinct style, from Kazuya Mishima's powerful moves to Yoshimitsu's enigmatic techniques. This game set the stage for what would become a cornerstone of the fighting game genre.

Tekken 2 (1995)

Tekken 2 arrived just a year later, refining the mechanics and expanding the character roster. The introduction of characters like Lei Wulong and Jun Kazama added depth to the gameplay. The improved graphics and more fluid animations made it clear that Tekken was here to stay.

Tekken 3 (1997)

Tekken 3 was a monumental leap forward. The game introduced faster gameplay, sidestepping, and a plethora of new characters, including Jin Kazama, who would become a central figure in the series. Tekken 3 was not just a game; it was a phenomenon, especially on the PlayStation. The console version's Tekken Force mode added an extra layer of fun, making this instalment a fan favourite. It here on this Tekken my favourite character came into being and before you ask "Who is it?" I shall tell you It was and still remains to this day. King.

Tekken Tag Tournament (1999)

The spin-off Tekken Tag Tournament was a delightful addition, allowing players to form teams of two fighters. This new dynamic added strategic depth and provided endless fun, especially in multiplayer battles. The game’s polished graphics and smooth gameplay on the PS2 showcased the potential of the new generation of consoles. I almost broke my PS2 once by pulling the controller so hard out of the console while playing. (Thank God for wireless controllers nowadays eh?)

Tekken 4 (2001)

Tekken 4 brought significant changes, with a focus on more realistic environments and the introduction of walls and terrain effects. While it received mixed reviews, it was a bold step in the series’ evolution. The game’s story mode provided deeper insights into the Mishima family saga, which continued to be a driving force behind the series’ lore.

Tekken 5 and Tekken 5: Dark Resurrection (2004-2005)

Tekken 5 was a return to form, blending the best elements of its predecessors with stunning visuals and a robust character roster. The game’s mechanics were refined to near perfection, making it a competitive staple. Dark Resurrection, an update to Tekken 5, added even more characters and balance tweaks, solidifying its place in the hearts of fans.

Tekken 6 and Tekken 6: Bloodline Rebellion (2007-2008)

Tekken 6 took the franchise to new heights with its extensive character customization and the introduction of the Bound system, which allowed for extended combos. Bloodline Rebellion, an update, further polished the experience, adding new characters and stages. The game’s release on the PS3 and Xbox 360 meant that high-definition Tekken was now a reality.

Tekken Tag Tournament 2 (2011)

A sequel to the beloved tag team entry, Tekken Tag Tournament 2 expanded the roster to include nearly every character from the series' history. The game’s refined tag mechanics and gorgeous visuals made it a hit among fans. The sheer variety of characters and team combinations ensured endless replayability.

Tekken Revolution (2013)

Tekken Revolution was a free-to-play experiment that introduced new players to the series while offering veterans a fresh challenge. Simplified mechanics and a smaller roster made it more accessible, though it lacked the depth of mainline entries. Nevertheless, it was an interesting chapter in the Tekken saga.

Tekken 7 (2015)

Tekken 7 marked a new era with its transition to the Unreal Engine, delivering breathtaking visuals and dynamic stages. The game’s story mode concluded the Mishima saga, providing closure to the long-running family feud. New mechanics like Rage Arts and Rage Drives added strategic layers to the combat. Tekken 7 was a fitting celebration of the series' legacy.

Tekken 8 (2024)

And now, we arrive at Tekken 8. This latest installment is a testament to how far the series has come since its inception. Tekken 8 feels like a love letter to fans, combining the nostalgic elements of the original games with cutting-edge technology. The graphics are more realistic than ever, and the gameplay is both familiar and innovative. The new mechanics and refined combat system make each match feel fresh and exciting.

Playing Tekken 8 takes me back to the days of crowded arcades and the early PlayStation era, yet it also showcases the incredible advancements in gaming over the past 30 years. The game's ability to evoke such nostalgia while pushing the boundaries of the genre is a remarkable achievement. From the simple yet addictive gameplay of the first Tekken to the complex and visually stunning battles of Tekken 8, this series has been a constant source of joy and excitement for me.

As I look back on my journey through the Tekken series, I am filled with a sense of pride and nostalgia. Tekken has not only shaped my gaming experience but also influenced the fighting game genre as a whole. Tekken 8 stands as a testament to the enduring legacy of this iconic franchise, and I can't wait to see what the future holds for the King of Iron Fist Tournament.

Though in saying this. I did read somewhere that the next Tekken might be the last. Don't get me wrong I could be wrong. I so hope I am wrong as its been with me pretty much my whole gaming life.

#Tekken series#Tekken review#Fighting games#Arcade games#PlayStation games#Tekken history#Tekken evolution#Gaming nostalgia#Tekken characters#Tekken gameplay#Tekken graphics#Tekken mechanics#Mishima saga#King of Iron Fist Tournament#Tekken fans#Classic video games#Video game franchise#Tekken milestones#new blog#today on tumblr

1 note

·

View note

Text

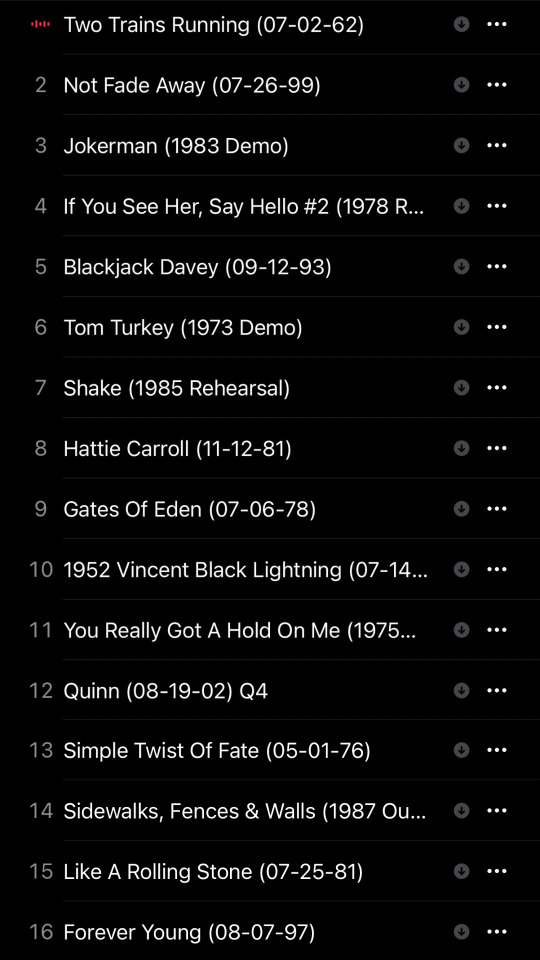

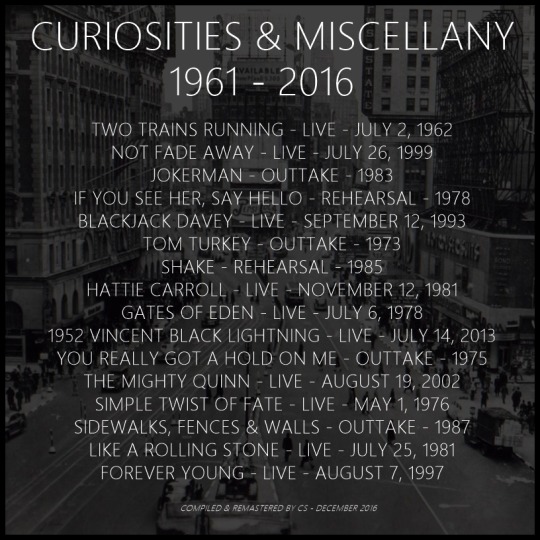

Welcome to the final installment of The Thousand Highways Collection. The previous volume of this series, Another Night Volume One, established the formula for this volume - a compilation of assorted curiosities and notable performances that did not make it onto more thematically coherent titles. Volume Two has some real humdingers, so open up those ears and listen in.

"Two Trains Running" is an old Muddy Waters track, and Dylan does it justice in this early solo performance from Montreal's Finjan Club. As with many of the singer's earliest uptempo songs, he powers along the tempo with a rhythmic tapping that's luckily been preserved by this crisp recording.

"Not Fade Away" is another cover, this time originating with Buddy Holly. Holly had been quite influential to the young Bob Dylan, as indicated by the Martin Scorcese's 2005 documentary, No Direction Home. Still, few of Holly's own compositions had been played by Dylan over the years. The Never-Ending Tour altered this, though, and a number of Holly's tracks entered the setlist between 1988 and 2016; none appeared more often, though, than the heavily rhythmic "Not Fade Away." This rendition from the much-loved Tramps show in 1999 is particularly well-executed.

"Jokerman" was the lead song on 1983's Infidels, and became quite a classic in its own right. This alternative version offers a very different vocal performance and a handful of lyrical variants. Instrumentally, it's quite similar to the final version.

"If You See Her, Say Hello" may sound familiar, as a roughly identical arrangement appeared on an earlier Thousand Highways compilation covering rehearsals from 1971 to 1989. This version, though, features a slightly more prominent harpsichord and violin, which improves the strangely baroque sound of the arrangement. It's a shame this didn't stay in the set past the first weeks of 1978's World Tour.

"Blackjack Davey" was one of the standout songs on Good As I Been To You in 1992, but only appeared live the following year. It's a very old song, and was also performed by Bob Dylan at the start of his career in 1961. Like "Barbara Allen" to "Scarlet Town," "Blackjack Davey" served as an inspiration for "Tin Angel" on Dylan's Tempest record from 2012. This arrangement is interesting, since live versions from 1993 are the only time when Dylan played the song with (limited) instrumental backing.

"Tom Turkey" is an outtake from 1973's Pat Garrett & Billy The Kid. Like other songs recorded for that soundtrack, it's effectively an excerpt from the "Billy" narrative with some unique instrumentation. Mostly instrumental, it includes only two verses of the "Billy" along with some intriguing harmonica fills.

"Shake" was an original Bob Dylan composition based roughly on Roy Head's "Treat Her Right." It was played briefly in 1985 and 1986 at the first Farm Aid show and on tour with Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers. This is the clearest recording, though even here the lyrics seem unfinished. It's quite groovy, if nothing else.

"The Lonesome Death Of Hattie Carroll" is one of only a handful of performances of this song from my favorite Bob Dylan touring year - 1981. Like most of the year, it features a compelling, rich vocal performance and a loose arrangement.

"Gates Of Eden" was played very rarely from 1965 to 1988, and one of the finest outings for the song was as a solo performance in 1978. This spot of the setlist was typically reserved for "It Ain't Me, Babe," but other classic 1960s tracks featured a few times, including "Fourth Time Around" and "A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall." Unfortunately, only "Gates Of Eden" was preserved with a lovely recording. Luckily, the performance is excellent.

"1952 Vincent Black Lightning" barely saw the light of day. It was recorded by an intrepid amateur taper in 2013, and only began to circulate two years later in a handful of alternative mixes. There are some chatty audience members near the tape recorder, but they do little to reduce the passion of this unique one-time performance of Richard Thompson's motorcycle epic.

"You Really Got A Hold On Me" was played by Bob Dylan and Bette Midler in the midst of a recording session for Midler's Songs For The New Depression. Much of the session consists of shaky takes on a rewrite of "Buckets Of Rain," but the two spontaneously burst into an equally shaky (yet delightful) performance of this Smokey Robinson gem. Bob Dylan has spoken of his admiration for Robinson, but this is one of the only times he played a song written by that American icon.

"The Mighty Quinn" is one of the most celebrated songs from The Basement Tapes, but the writer only sang it live a few times over the past fifty years. Other versions can be found elsewhere on The Thousand Highways Collection, but this is the only time that the song featured Dylan's excellent backing band harmonizing as it did on bluegrass classics from 1998 to 2002.

"Simple Twist Of Fate" is a heartbreaking song, but rarely has it been performed with the pathos instilled on this night in Hattiesburg during the Rolling Thunder Revue. It sounds fairly similar to the style used to great effect earlier in the tour on "If You See Her, Say Hello," though this song is not nearly as re-written as its Blood On The Tracks companion.

"Sidewalks, Fences & Walls" did not circulate for decades, but this outtake from Down In The Groove finally appeared in the taper community during the 2000s. It's a straightforward soul song infused with depth by a passionate vocal performance. The sound is less than stellar, as it only circulates as a fairly compromised lossy recording, but we should be grateful that it appeared at all.

"Like A Rolling Stone" is my favorite rendition of a Bob Dylan classic. It's not quite as tight as earlier performances from the 1981 tour, but it makes up for that looseness with one of Dylan's most inventive, passionate, shredded vocal tracks you'll ever hear. You can point to moments like this as one of the reasons that the singer's voice deepened and lost some of the range it displayed in the 1970s, but at least we received incredible recordings like this one from the singer pushing his art outside of his comfort zone.

"Forever Young," a sentimental song written by the singer for his child, is as appropriate an ending as you could ask for on this long listening journey. Happily, it features one of Dylan's unique lead guitar performances and a touching harmonica solo.

0 notes

Text

Sofia Coppola’s Path to Filming Gilded Adolescence

There are few Hollywood families in which one famous director has spawned another. Coppola says, “It’s not easy for anyone in this business, even though it looks easy for me.”

By Rachel Syme January 22, 2024

From Marie Antoinette to Priscilla Presley, Coppola’s protagonists enjoy enormous privilege but little autonomy.Photograph by Thea Traff for The New Yorker

Wshen Eleanor Coppola went into labor with her third child, on May 14, 1971, at a hospital in Manhattan, her husband, the director Francis Ford Coppola, was on location in Harlem, shooting a scene for “The Godfather.” Hearing the news, he grabbed a camcorder from the set and raced over to capture the moment. “When they say, ‘It’s a girl,’ my dad gasps and nearly drops the camera,” Sofia Coppola told me recently, of her birth video. “My mom is there, just trying to focus.” The footage—which has been screened by the family multiple times over the years, and as part of a feminist art installation designed by Eleanor—was the first of many instances in which Sofia would be seen through her father’s lens. When she was just a few months old, Francis cast her in her first official film role, as the infant in the dénouement of “The Godfather,” in which Michael Corleone, the ascendant boss of the Corleone crime family, anoints the head of his newborn nephew as his associates murder rival gangsters one by one.

There are plenty of distinguished bloodlines in the history of Hollywood—the Selznicks and the Mayers, the Warners, the Hustons, the Bergman-Rossellinis, the Fondas—but very few, like the Coppolas, in which one famous director has spawned another. After an early life spent in front of the camera, Sofia Coppola made a career behind it, becoming one of the most influential and visually distinctive filmmakers of her generation, with eight features to her name. Her second, “Lost in Translation,” from 2003, earned her an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay and a nomination for Best Director, making her the first American woman recognized in that category. Her career, of course, has been bolstered by an unusual wealth of resources. Francis’s company, American Zoetrope, has been a producer on all her movies. When she made her début, “The Virgin Suicides,” in 1999, she was able to cast an established star, Kathleen Turner, with whom she’d appeared as a teen-ager in her father’s movie “Peggy Sue Got Married.” She got permission to shoot “Somewhere,” her fourth film, inside the clubby Hollywood hotel the Chateau Marmont because in her youth she was a regular there, and even had a private key to the hotel pool. Still, no director can get a project green-lighted at a snap of the fingers, especially in today’s franchise-glutted Hollywood, and especially as a female director in an industry that remains dominated by men. Coppola is self-aware enough to know that it would be bad manners for someone in her position to complain. But she told me, “It’s not easy for anyone in this business, even though it looks easy for me.”

When we first met, in the fall of 2021, for breakfast near her home in the West Village, Coppola had spent the previous two years at work on her most ambitious venture to date, a miniseries, for Apple TV+, based on the Edith Wharton novel “The Custom of the Country,” from 1913. Coppola had adapted the book into five episodes and cast Florence Pugh in the lead role of Undine Spragg, a Midwestern arriviste on a desperate quest to infiltrate Gilded Age Manhattan society. Coppola, like Wharton, is known for her gimlet-eyed portrayals of a rarefied milieu, and for her insight into female characters who enjoy enormous privilege but little autonomy. “Marie Antoinette,” her most expensive movie, had a budget of forty million dollars, still modest by Hollywood standards; for “Custom,” she was planning for, as she put it, “five ‘Marie Antoinettes.’ ”

At breakfast, though, she told me, “Apple just pulled out. They pulled our funding.” Her voice was quiet, and her face—high cheekbones, Roman nose—was placid. “It’s a real drag,” she said. “I thought they had endless resources.” During the project’s development, she’d gone back and forth with executives (“mostly dudes”) on everything from the budget to the script. “They didn’t get the character of Undine,” she recalled. “She’s so ‘unlikable.’ But so is Tony Soprano!” She added, “It was like a relationship that you know you probably should’ve gotten out of a while ago.” (Apple did not respond to request for comment.)

Coppola grew up watching Francis do battle with movie studios. The success of the “Godfather” films hardly assured him funding equal to his ambitions, and he often went to harrowing lengths to get his projects made independently, driving himself to the brink of bankruptcy or nervous breakdown. “Hearts of Darkness,” a documentary co-directed by Eleanor about the notoriously tortured production of “Apocalypse Now,” is subtitled, only a bit hyperbolically, “A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse.” (At the age of eighty-four, Francis is financing a new film, “Megalopolis,” with a hundred and twenty million dollars of his own money, freed up by the sale of a portion of the family’s wine business.) Coppola absorbed from her father the ethos that it was never worth it to cave to the creative demands of executives. In 2014, she agreed to make a live-action version of “The Little Mermaid” for Universal Studios, but amid disputes during development (including, she said at the time, an executive asking her, “What’s gonna get the thirty-five-year-old man in the audience?”) she walked away from the job. “I don’t actually want a hundred million dollars to make a movie,” she told me, of studio deals with strings attached. “I learned it’s better to do your own thing.” She refuses to take on projects unless she is guaranteed the right to choose her creative team and control the final cut.

In January of 2022, after trying in vain to secure alternative funding for “Custom,” Coppola moved on to a new project, an independent film adapted from Priscilla Presley’s 1985 memoir, “Elvis and Me.” Presley’s relationship with Elvis began when she was just fourteen. Like Marie Antoinette, she found herself unhappily married to a King. Paging through the book while in bed with a case of covid, Coppola had begun to see the picture unfolding in her mind. “I just thought about her sitting on that shag carpet all day,” she recalled. She wrote a draft of the script quickly and told her longtime producer, Youree Henley, that she wanted to be done shooting by the end of the year. She was undeterred by the coming release of Baz Luhrmann’s eighty-five-million-dollar film “Elvis,” which was due out in a few months. A rhinestoned frenzy of a bio-pic, Luhrmann’s movie portrayed Priscilla as a marginal character and a happy helpmate. Coppola called Presley and said, “That’s not how I see you at all,” and after hearing Coppola’s vision Presley signed on as a producer.

“Marie Antoinette” was filmed inside the real Versailles, a cinematic coup. For “Priscilla,” the Elvis Presley estate, wary of a film told from Priscilla’s perspective, denied Coppola access to Graceland. Coppola’s production team instead constructed the façade and the interiors of Elvis’s Memphis mansion on a soundstage outside Toronto. I visited one afternoon in November of 2022, as the shoot was under way. Off set, Coppola, who is fifty-two, dresses with understated elegance—Chanel slingbacks, collared blouses. Now she was wearing her only slightly less polished “set uniform,” gray New Balances and a black Carhartt fleece over a Charvet button-down. She led me through the hangarlike space and into the ersatz Presley home. The entrance was flanked by two large lion statues. In the gaudy living room, she pointed to a floral arrangement. “Those are real orchids,” she said. “It surprised me, with our budget. How extravagant.”

Coppola’s team had budgeted for forty days of shooting, already a squeeze, but at the last minute a piece of financing had fallen through, and she’d had to slash the story to be filmed in just a month, for less than twenty million dollars. Much of the movie is set in the Memphis summer, but they were filming as winter approached, which was cheaper, so Coppola had to coach her cast, shivering through outdoor scenes in their bathing suits, to “act warm.” Instead of filming two long shots she’d wanted in Los Angeles, of Priscilla driving a convertible down a palm-lined street and swan-diving into a pool, Coppola saved money by borrowing footage from a Cartier commercial she’d shot in 2018, with an actress who kind of looks like “Priscilla” ’s lead, Cailee Spaeny, at least from behind.