#but it does come from a fundamental misunderstanding of what autism actually is like like

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Once again just find it really rich that people claim this is like the autistic website meanwhile everyone is mean as fuck about people actually having autistic traits

#but it does come from a fundamental misunderstanding of what autism actually is like like#im not sure why but people on this site seem to think autism just means youre normal but like smart and have intense interests and thats al#it means or something . and then are like if you find socializing painful and have trouble maintaining friendships have you considered that#youre just a pathetic person?????#its frustrating too cos i really am trying to improve all these aspects of my life but im also trying to stop judging myself for strugglin#with them in the first place!!!!!! because thats literally just something i have no control over i can only control how i choose to cope#and like deal with it#but idk this idea of like well im autistic but not like those annoying gross autistic people who like lame baby suff and dont go outside .#its just like Rolls my eyes i dont know like .... sure whatever

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

I feel like the weird thing with autistic representation is like

It's hard to do it wrong on terms of it being an inaccurate portrayal of autism. Nearly every "inaccurate" criticism I see levied at a particular autistic character always makes me quirk an eyebrow, because most of the time I literally know someone in real life who is exactly like them. Sometimes it's me.

Autism is a spectrum in virtually every way possible, and as a consequence it's pretty rare that I see a portrayal of autism that makes me outright say "that's not what autism looks like", because for a lot of them, it CAN be what autism looks like. It's just uncommon. Or maybe it's something heavily influenced by autism, rather than being an explicitly autistic trait. It's not impossible to make something that's bad autistic rep because "that's just not what it looks like", but autism is such a wide experience that it's difficult. Yes, this even goes for very showy, stereotypical portrayals of autism. I know people who are very stereotypically autistic. It's a stereotype because there's some truth to it.

That's not typically why autistic representation is bad.

More often than not, the biggest problem with autistic representation is actually that it insists that there IS one mold of autism that autistic characters (and therefore, autistic people) fit into. They have to be an ugly, sweaty, socially inept nerd, who does weird things for absolutely no reason, and can't empathize with other people.

And that isn't a problem because that isn't what autism looks like. That's a problem because in most media, that's all autism looks like.

I'll say quickly as a disclaimer that autism doesn't make you a racist, or a sexist, or a homophobe, or a transphobe. Autism doesn't make you an idiot, you do that on your own.

But I do know people whose own racist, sexist, homophobic, or transphobic beliefs are influenced very greatly by their particular brand of autism, due to the way they think about things. Obviously it doesn't excuse it, and no, autism isn't why they have those beliefs, but it does play a role in building and cementing them. It's something you have to peel back if you want to have a serious conversation with them about it.

This goes for a lot of different problematic aspects of how people might portray autism in a work. No, impaired empathy and more black and white thinking don't make you transphobic; if that was the case most autistic people would be. But it certainly doesn't help you gain a more open-minded perspective. Having sensory issues and increased sensitivities to certain smells or feelings doesn't make it impossible for you to clean yourself, but it certainly doesn't help you feel comfortable showering.

The links between these things aren't typically as simple as media portrays them as. But they do happen, too, let's not pretend they don't. They are real. Autism influences a lot about a person, but it's very nuanced. People are complicated.

I think the real problem arises in the harm that comes from a portrayal, typically in reinforcing fundamental misunderstandings about autism, as well as perpetuating the particular way people unacquainted with it perceive both autism and autistic people. They aren't bad because "This isn't what autism looks like", the worst autistic rep you know probably has someone who heavily relates to it. They're bad because they present bad ideas about autistic people. Sometimes they perpetuate wrong ideas about how to "treat" autistic people, like certain therapies or treatments which are literally, actually dangerous for their health. But more than anything, they just don't help with the concept people have of autistic people simply being an intellectually disabled "other", which is cringe.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hellooo!! Just curious to see your opinion, what are your thoughts on age regression and the trauma surrounding it? Or possibly the percentage of people who age regress that are ND? (You don't have to answer btw I just wanna see what you think!)

Oh I age regress myself actually! I've made a few posts about it but I haven't talked about it a whole lot on here so I understand why you wouldn't have seen it/g

My thoughts on this got too long so I'm putting it under a cut but beforehand

tl;dr: I'm an involuntary age regressor and this is inherently linked to my childhood trauma, my autism, and my plurality. I do Not Support the sexualization of regression in any capacity and am deeply hurt by it as a survivor. I also find anti-regression sentiments incredibly frustrating because it's hypocritical to boast about how everyone needs to nurture their inner child only to lash out at whoever does so in a way that's "too cringy." Etc.

Mine is involuntary so I think that especially gives me a perspective on the whole thing like, I absolutely support people who do it voluntarily and generally think that's healthier, but like I think it's a natural progression that people who didn't experience a good childhood or even a childhood at all are going to have times where they need to act like a child and I tried to repress mine for a number of years because I was afraid of what people would think of me but it turns out that things only get worse when you do that and also that the people who really matter in the long run just want me to exist as I am and to accept the parts of myself that I'm self-conscious about.

I do get why a lot of people initially are wary around it due to the way that it's sexualized (which as a survivor of the trauma sexualized and someone who is actually age regressing I find absolutely fucking disgusting) but I really don't think that traumatized and nd people should have to answer for the people who are by all intents and purposes targeting us first and foremost.

But aside from the valid concerns that are very easily handled by simply separating our communities from the harmful ones, any other argument for it misunderstands what it is on a fundamental level and often falls into a lot of ableist rhetoric.

I mean I've gotten a number of anons at this point criticizing me for being "too childish" for (casually) enjoying a lot of children's media and for being too child-like and whiny and that isn't in any direct response to my age regressing but it is attached to this idea that to be a valid autistic person I need to "act my age (whatever that means in this case, considering I very much Am Aware of the bodies age at all times lol)" and that if I come off as childish at all that I'm somehow infantilizing other autistics and making the community look bad etc.

And it's extremely frustrating when you spent the first 5/6ths of your childhood trying to act like an adult because you're in a trauma environment and that's what's being demanded of you, then you realize you've never been a child so you snap and try to get some semblance of having had a good experience in your late teens, and then are immediately expected to "act your age" when there's no one in your life to model exactly what that looks like.

Additionally, all of the markers of having grown up, and a few of the things that ableist anons tell me to "just go and do" like it's super easy, are things that most marginalized gen Zers just cannot afford to do in this economy?

For one I was never sent to school in the first place so I never had the progression of going through different grades and I didn't ever have a graduation of any kind but I also currently am struggling to get my GED and I've completely sworn off college for now because it's not worth it to go into debt when a degree does very little for me in this economy. I'm too disabled to get a car or learn to drive, too queer and plural for a traditional marriage, and though I am working on trying to get a job and am going to give that all once I can that still hasn't been a reality and I've been an adult for a few years now already.

And being physically disabled, a little person, and visibly autistic on top of all that means that I'm not treated like an adult in any capacity no matter where I go unless it's legally required for people to do so. So it sometimes feels deeply unfair to hear that it's somehow fine to have any semblance of adult independence and opportunity taken from me but then to turn around and demonize me for returning to things that comforted me in childhood or to allow myself, in safe environments, to finally decompress and be myself for a while.

It's just really telling that everyone is all "give your inner child time and nurture them... unless you do so in a way that's cringy in any conceivable way why aren't you acting your own age why do you like a kids movie ew what the fuck is wrong with you get a therapist lol"

Lastly, it's deeply frustrating as a system member because internally I'm not even the body's age. This does NOT mean that at any point I can act in a way that would be flat out inappropriate for the body's age or that my being younger internally is at all comparable to being a minor externally/for real. But like in terms of maturity and stress management I still am stuck around age fifteen, I had this weird experience of watching all my peers grow up and change a lot and move on with their lives but I stayed very much stagnated both in the sense of my development mentally and in the sense that I just have not felt like any time has passed since I formed in 2016.

If I were able to be healthy about everything then I would not be hosting this system and someone closer to the body's age would be because they have the maturity to keep up with our brain and to manage our life better (so many of our headmates do!) but I cannot control it I am stuck in control of the body permanently for now so it's like yeah mentally I'm still very much an exhausted teenager who has to meet expectations that are far beyond what they are able to do regularly. So I Really Just Cannot Blame Myself for sometimes having had enough of all that and regressing. I cannot control when this happens (it tends to happen when I get overwhelmed) but even if I could I would choose to regress because it is one of the few healthy coping mechanisms I have at this point honestly.

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

A bit of reading : orwomen.()scot/did-you-know/?fbclid=IwAR0H7TqxQNqemZcAGFtvR_HLkbkxmZ4FY6srcgrULWxGPyWuc6QPTmDQfVI

Did you know…

…that 80-95% of people who say they are trans choose to have no medical treatment at all – no surgery, no drugs, not even therapy? Transwomen are just male people who subjectively believe that they are female. That’s it. That is all that’s required.

Despite some commentators describing an “epidemic of violence against trans people“, transwomen are no more likely to be murdered than anyone else, and the best data available shows it’s half as likely. In Scotland, zero have been killed. In fact, transwomen are almost twice as likely to be the perpetrator of a murder than to be murdered in the UK, which is not surprising since a male pattern of violence is retained regardless of any transition or cross-dressing.

The 48% of trans youth have attempted suicide statistic is nonsense too. It was based on just 27 trans people (aged 26 and under), from a self-selecting online survey – which made the data worthless. Yet that hasn’t stopped the TIE Campaign peddling similar in Scottish schools (or is it 27%, they seem confused?), contrary to Samaritans advice on avoiding attributing the cause to any one incident. The NHS Gender Identity Development Service actually says “suicide is extremely rare” and rates of self-harm, distress and suicide ideation are similar to other children seen by CAMHS.

Did you know that 1 in 50 males in prison now self-id as trans according to Ministry of Justice figures? If it is so dangerous to be trans why do so many choose to come out when in jail?

Were you aware that 95% of prisoners are men, and 5% women? That most women in prison are there for financial crime, and most men are in for violent offending. Did you know that men commit 98% of sex offences? That 48% of transwomen prisoners are sex offenders (compared to less than 20% in the general male estate) and would swamp the female estate if they all transferred.

What makes these convicted sex offenders, who were born male, women? Why should female prisoners be locked up with rapists if they say “I am a woman”? Are you willing to be in a prison cell with a male rapist on that basis? And if not, do you think other women should be? Are you aware that women have already been sexually assaulted and raped, in several countries, because of this policy?

Did you know that Scotland already has a policy significantly more liberal than England’s, stating that transgender prisoners must normally be housed according to the “social gender” with which they self-identify? And that this policy was brought in by a senior prison officer, himself now a convicted sex offender? A policy put in place without even talking to women’s groups or considering that there would be any impact on female prisoners at all. Despite warnings of abuse, including from former women’s prison governor Rhona Hotchkiss, the promised policy review has not been forthcoming.

What about women’s refuges, have you considered what it could do to a woman fleeing male violence to encounter a male in that refuge? Read why the CEO of a domestic violence charity, Karen Ingala Smith, considers it imperative that refuges remain women-only, and her speech at the Scottish Parliament.

Did you know that a woman was asked to leave a shelter because, as a rape survivor, she couldn’t sleep in the same room as a strange male, regardless of how he identified? Are you aware that a man used self-id to access a women’s shelter where he sexually assaulted vulnerable women? Are you aware that a rape relief shelter in Canada lost all public funding for insisting they remain women-only, and had a dead rat nailed to their door?

Are you aware that the Scottish Government imposes a transwomen inclusive policy on Scottish Women’s Aid as a condition of funding and that Rape Crisis Scotland refused to guarantee a female counsellor for a traumatised teenager? We know from private meetings that they erroneously believe they cannot provide a single-sex service due to a lack of ‘case law’, despite having previously done so for many years. Did you know there is a male manager of a rape crisis centre, who failed to disclose his sex at interview, and which still claims to be women-led?

Are you aware that despite less than half of changing rooms in swimming pools and sports centres being mixed sex, 90% of sexual assaults have happened in them? Yet mixed-sex, ‘gender-neutral’ facilities are constantly pushed, including in schools – contrary to law and building regulations requiring separate sex provision – when it would be more responsible to increase third space unisex provision for the comfort of those who need it.

That’s before you even get into the issue of how to keep out predatory men who aren’t trans, if you say that any man who ‘identifies as a woman’ can use communal changing/showering areas at will. A man exposing himself in a park commits a crime. A man doing so in a women’s changing room, where you’re also naked, who need not have even told staff he identifies as a woman, may no longer be committing an offence.

Did you know that the Scottish Government funded LGBT Youth Scotland, a spin-off group from Stonewall, to write guidance for schools that breaches children’s rights in at least eleven ways? This includes the unscientific belief in gender identity, which even the Justice Minister is at a loss to define, the promotion of harmful breast binding and the removal of all single-sex spaces and sports. No-one should be surprised at this as Stonewall have long campaigned for the removal of women’s rights, although single issue political pressure groups should have been no-where near schoolchildren.

It took the Government until June 2019 to commit to replacing this guidance, having privately received advice that it was “not legal“. Yet, this new legally compliant guidance is seven months overdue and the Education Minister is refusing to withdraw LGBTYS’s guidance in the interim.

Why should we accept smear tests from any male who feels they have a womanly gender identity – what does that even mean (let’s ask the Justice Minister again)? And yes, it is happening. A rape survivor who wanted a woman to carry out her breast screening found her letter used as an example in hospital trans guidance as ‘unacceptable’ and ‘highly discriminatory’. And a woman in a psychiatric ward who was terrified at being locked in a ward with an “extremely male-bodied” fellow patient was regarded as a transphobic bigot. The truth is that women in mixed-sex hospital wards, particularly psych, have very real reasons to fear men.

Did you know that 35 clinicians have resigned from the Tavistock (children’s gender clinic in London) over their failings, including the Governor? Who later wrote a damning account of the abject failure to heed evidence that their affirmation-only policy is harmful to children, especially to the huge influx in girls who may suffer other complex problems, such as trauma, autism, a history of sexual abuse or discomfort with their developing sexuality. A staggering 48% of children referred to Tavistock have ASD traits, and a BBC Newsnight investigation revealed significant numbers of children seeking transition treatment based on their family’s homophobia.

Are you aware that studies show that puberty blockers result in 100% of children progressing to cross-sex hormones – whereas, if left unmedicated, the Tavistocks’s own research shows over 90%, if supported by counselling, are happy with their sex once they emerge from puberty. Did you know hormone blockers may cause sterility, a large decrease in IQ, bone density loss, and more? An investigation by the Health Review Authority concluded that blockers are really the start of irreversible physical transition and recommended that “Researchers and clinical staff should…avoid referring to puberty suppression as providing a ‘breathing space’, to avoid risk of misunderstanding.” This led to a major overhaul of the NHS UK website which no longer considers blockers to be fully reversible and confirms long-term effects are unknown.

The young person’s gender clinic at Sandyford, Glasgow has recently withdrawn their information booklet and we trust it will be similarly updated. Do you think all the government funded trans organisations will be scrupulous in updating their information too – including LGBT Youth guidance in Dumfries and Galloway, Scottish Trans/NHS guidance, and Stonewall advice, among many more, including of course the already deemed “not legal” school guidance by LGBT Youth?

Are you aware that the number of children referred to Sandyford is rising at a faster rate than the rest of the UK? Yet they don’t actually know how many girls have been referred as children can select what sex they want recorded on medical records – although unofficially, clinicians report similar concerns as elsewhere about the huge proportional rise in young girls seeking to transition. Did you know that bias, and not evidence, dominates the WPATH transgender standard of care followed in Scotland? And it is woefully out-of-date considering the fundamental change in patient make up since it was written in 2011.

Read the speech given by Dr David Bell at the Scottish Parliament and consider why, if his report about issues at the Tavistock prompted the Director to resign, was it not enough for the Health Minister, Jeane Freeman, to instigate an enquiry into identical practices at Sandyford? Perhaps the Government will listen to the outcome of a Judicial Review that is being sought by Keira Bell, a detransitioning woman, who wants to protect other troubled young girls from similar treatment.

Are you aware that women with our views are threatened with violence, rape and death, almost as an everyday occurrence? We are told TERF is not a slur, but I challenge you to find any instances of it being used without abuse or threats attached to it. Do you think it’s in any way acceptable for lesbians to be on the receiving end of these menaces for asserting, or even just trying to be proud of, their right to be same-sex attracted? Do you really think there’s such a thing as a lesbian with a penis?

All that hate is from transactivists, and is aimed at women with our views. I challenge you to find anything remotely equivalent from here, from our recorded talks, or indeed anywhere else. This is NOT a case of two sides as bad as each other. And it’s notable that the hate is not aimed at genuinely transphobic, aggressive men. It’s aimed at women. It’s aimed at us.

And JK Rowling. Read the tweets she posted and look at the replies. Read the essay further explaining her thoughts and ask how anyone could possibly think she deserved such atrocious abuse, or how transactivists thought it in any way acceptable to post penis images in retaliation (don’t worry, it’s been edited!) on a child’s thread about Ickabog art.

Did you know women can be, and often are, fired for believing sex is real, that humans cannot change sex, and women and girls are entitled to privacy when undressing or otherwise vulnerable? And yet poll, after poll, after poll, after poll show that this is the majority view, by at least 80%. You may well wonder why then, is the Scottish Government proposing to bring in Hate Crime legislation that would see even JK Rowling imprisoned for up to seven years for expressing views deemed abusive by transactivists, yet affords women no such protection in law, based on their sex.

Innate gender identity is a belief system. There’s no evidence one exists. If our Government cannot even define it, then it should not be presented as fact to our children. It should not over-ride women’s hard fought for rights.

Do you know that the very word ‘woman’ will change definition, if the trans lobby succeed? If we can’t define what a woman is, how can we accurately capture data? How can we record male violence, the pay gap, our representation in government, business, finance, law, media…anywhere? Police Scotland already record incidences on the basis of gender identity, but can’t seem to recall when, or why that happened, and the census looks to be going the same way, despite the importance of recognising sex being shown quite dramatically by COVID-19.

An influential lobby loudly insisting that they won’t be erased (when trans organisations are heavily state funded and train all major businesses, branches of government, school teachers, universities and NHS boards) are actively campaigning to erase the very definition of what a woman is – best archive it, just in case! Have you noticed how easy it is to define a woman when we’re being aborted, subjected to FGM, married off, denied the vote, raped, murdered, paid less, represented less in every single sector of government and industry, expected to perform most of the world’s unpaid labour, and constituting 71% of the world’s modern slaves? The only places that seem unsure on what a woman is are the places feminism was starting to make inroads. It’s almost like there must be some sort of a connection, isn’t it?

We don’t have any fear, resentment or hatred for trans people. We agree there should be protection in law against discrimination and violence. We just don’t agree that our rights need to be railroaded over in the process. We don’t agree that male people should access women’s spaces, or benefit from women’s provision, at will, without our consent. Our name is WOMEN and our rights matter.

Don’t you agree…?

148 notes

·

View notes

Text

Agent 47 being autistic coded; a post ( that ive tried to write about seven times ). And yes I am autistic, so this comes from a desire for representation and my own experiences and isn't just a NT extrapolating a headcanon based upon a list of vague traits found online. I'm a fan of lists so I'm gonna use one to explain my reasoning and why people who claim it's Bad Representation or that it can't be canon are wrong.

Generally huge chunks of 47's development and arc as a character revolve heavily about the deconstruction of Ort-Meyers hypothesis that he created a human being that did not feel emotions or form connections or have autonomy. Because he didn't, as Ort-Meyer based his presumptions on; a) his own biased perspective, research and his clones' upbringing, b) an extrapolation from 47's -- largely autistic coded -- traits, which he misinterpreted as a luck of humanity. I doubt it was intentional, but this is a surprisingly apt tackling of the perception of autistic people as the "heartless genius with completely no feelings" type. As while 47 has traits that make him seem this way, his personal growth displays that he is far from that.

47 having so many autistic traits, a comprehensive list of one's I came up with off the top of my head:

Finding it hard to make friends or preferring to be on own; this is a very obvious trait in 47's character. He has very few friends and actively avoids other people, particularly those who seem to irritate him despite their friendliness ( Smith being a key example or this ).

Seeming blunt, rude or not interested in others; Smith and 47's handshake scene. It could very well just be an inability to read " obvious social rules " as Smith does little aside hold his hand out to indicate the action he wants, 47 simply may have not read well and walked off ( hey man, it happens ).

Finding it hard to express emotions; 47 doesn't express emotions verbally very well. He experiences numerous, has flashbacks due to his childhood trauma and more, but even when confronted by someone close to him who is asking about his emotions in concern he does not actually rely how is feeling, and instead describes what he is experiencing ( in his usual fashion ) instead. "Are you alright?" "-It comes back in flashes" and then a very basic list of names for feelings. It is often easier for autistic people, myself very much included, to explain emotion via the narrative events resulting in them instead of the feelings in of themselves or just using one word descriptors to get by. 47's couples with his dissociation from his childhood emotions, due to forced repression.

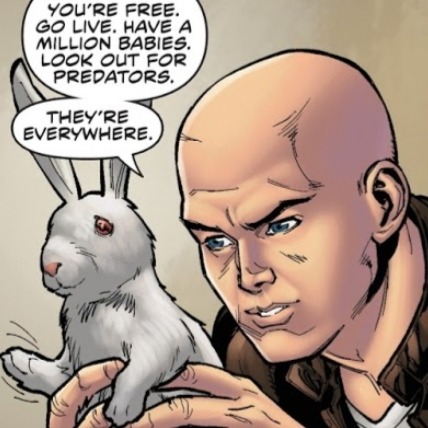

Stronger attachment to animals; all you have to look at is 47's desire to have pets when possible and how he engages with them in comparison to his attitude with other people. As a child, despite his trauma, he manages to establish an attachment to a lab rabbit ( multiple rabbits in the comics ) and maintain these affectionate connections until they die.

Monotonous speech and lack of inflection; 47 can convey emotions when actively putting on a character or attitude on missions, but so can quite a lot of autistic people. It's often called "masking" and it's a phenomenon where an autistic person consciouslly acts "more neurotypically" to fit in. And it is evident by 47's awkwardly, forced sarcastic humour that this is not his natural dictation. When speaking amongst allies, 47's delivery is equally as monotonous as to enemies, his natural manner of speech is "bland".

Getting very upset or uncomfortable if someone touches or gets too close; 47 seems willing to let a couple of people max touch him -- that being Diana and Victoria, plus Lucas to a slightly lesser extent, all of these people are those who he knows and is comfortable with. Whilst on the other hand the likes of Lei/Mei Ling, who after kissing/hugging 47 abruptly has him immediately reel back, despite his sympathy for her. He does not like touch from people, even those who he has a substantial amount of positive emotions for. This also includes Smith, who 47 reluctantly rescues, but develops into actively saving him even when unnecessary; he is not keen on contact even as mild as handshake.

Preferably to plan things carefully before doing them; the overachievers short story essentially establishes that, canonically, 47's modus operandi is extravagant, expertly pre planned hits. He seems to ( according to Soders and Diana ) favour these, especially in comparison to other agents, to which it does not come naturally. (NT trying to understand a ND's thinking)

Having a lack off or little empathy; I want to preface that a lack of empathy is not a lack of sympathy or an inability to feel compassion, empathy is an entirely different sensation that some autistic people don't have, 47 is one of them. A key example of this is 47's lack of empathy for other clones with similar experiences: specifically agent 17 ( his biological brother ) and Mark Parchezzi, both of who he murders. While both of these men were bred by malevolent groups and raised to kill; Mark in a more extreme sense than even 47. He seems to be unable to conjure up empathy for people who he does not have an established connection or a need to keep them alive long enough to form the sympathetic connections that he is capable of. This is true to quite a lot of people with autism, it is hard to empathise to someone you don't know, regardless of how intertwined your situations are.

Debunking one of the reasons why 47 would "not make good autistic rep"

"47 doesn't have emotions, which creates a bad stereotype". This isn't even a problem with the reasoning, if 47 was an emotionless being I'd actually agree with you. But instead this criticism is more so a fundamental misunderstanding of 47 as a character, because he is not emotionless by any extent of the definition, he lacks empathy but that doesn't reduce his ability to have sympathy or show compassion, nor does it really reduce any other emotion that he posses. 47 gets visibly angry ( blood money after diana injects him, absolution at travis, damnation.. throughout just that whole book ), he shows compassion towards people that he doesn't have to regularly ( victoria, emilio, smith ) and that extends to animals too. If 47's character was more reminiscent of this "human robot" trope - say, he bore more resemblance to one of his brothers: 17, then I would understand. But he doesn't. He's just a monotonous autistic coded man.

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

I actually sat down and read all of To Siri With Love since there’s been so much talk about it. I have a lot of thoughts about it; it has several problems that haven’t been discussed much because its biggest problems are so egregious. Writing all of that down would make one hell of a long post, though, so right now I’m just going to talk about the worst of it: the eugenics.

I don’t have page numbers for citations because I’m using the ebook version, but I’ll include the chapters the quotes are from.

Here’s the full quotation of the first time in the book that Judith Newman advocates eugenics against her son, in Chapter 8:

A vasectomy is so easy. A couple of snips, a couple of days of ice in your pants, and voilà. A life free of worry. Or one less worry. For me.

How do you say “I’m sterilizing my son” without sounding like a eugenicist? I start thinking about all the people, outliers in some way, who had this fundamental choice in life stolen from them—sometimes cruelly, sometimes by well-meaning people like me. The eugenics movement can be traced back to psychiatrist Alfred Hoche and penal law expert Karl Binding, who in 1920 published a book called The Liberation and Destruction of Life Unworthy of Life. Its popularity fostered the first eugenics conference in the United States in 1921. The term “eugenics” means “the good birth.” Sample papers: “Distribution and Increase of Negroes in the United States,” “Racial Differences in Musical Ability,” and “Some Notes on the Jewish Problem.”

“Liberation” is such a wonderful euphemism, and in this context many people like my son—and undoubtedly some even less impaired—were “liberated” from the burden of life by those enthusiastic proponents of culling the herd, the National Socialists. An estimated four hundred thousand “imbeciles” were euthanized during Hitler’s rule, but not before they were the subjects of all sorts of medical experimentation. For a while there, Austria seemed to have cornered the market on brains in jars.

The idea of outright murdering “nature’s mistakes,” as the disabled were called, was softened somewhat in the United States. As the psychiatrist Leo Kanner was observing and defining autism, he was also lobbying for sterilization, but not death, of disabled populations. This was considered a progressive view at the time. (He believed there were all sorts of repetitive tasks autistic people could perform that would be good for society, and he wasn’t wrong here, that’s for sure. But we didn’t have computer programming at the time, so he proposed a population of ditch diggers and oyster shuckers.) Around the same time Hans Asperger, the Austrian pediatrician who was the first to identify autism as a unique mental condition, was concluding that “not everything that steps out of the line, and is thus ‘abnormal,’ must necessarily be ‘inferior.’”

That was an even more radical line of thought, and one society struggles with to this day. But wherever you stand on this question, when you start considering how the history of disability is inextricably intertwined with the history of euthanizing and enforced sterilization, you come away unsettled. I began to question my certainty that Gus should never have kids. There is a good success rate in vasectomy reversals, and surely there will be even easier, more reversible methods for men soon. And when there are, I’m going to be the first in line to sign him up. Kids at twenty or twenty-five? No. Thirty-five? I can hope.

I know this is a long quote, but I wanted to share it because I think it’s noteworthy that Newman is aware of the history of eugenics. She knows that it’s the ideology that Nazis used to justify the Holocaust; she knows that it’s been used in the United States to discriminate against disabled people. She knows that it’s a racist and antisemitic tool of oppression. And yet, she still wants to forcibly sterilize her son.

She reiterates her stance in Chapter 13, after watching her son go on a date.

Newman repeatedly emphasizes that vasectomies are reversible, as though that’s a justification for medical abuse. That’s not always true, though:

It's best to consider a vasectomy to be completely permanent. Although the procedure is reversible, and advances in microsurgery techniques have made vasectomy reversal far more successful in recent decades, it is not always a guaranteed success.

...

If fewer than three years have passed since the original vasectomy, patency success rates are around 97 percent and pregnancy success rates are 76 percent. But success rates can fall over time. In men who had a vasectomy 15 years or more before their reversal, the likelihood of restoring the vas deferens is 71 percent and chances of subsequent pregnancy hover around 30 percent.

Since Newman states that she wants to have power of attorney to make a decision about a vasectomy when her son turns 18, and since she later says that she “can hope” her son might have children at 35, it’s most likely that the lower rates of success would be the relevant statistics.

More importantly, though, I think we can all agree that abuse is still abuse even if the medical effects truly are reversible.

If the possibility of an unwanted pregnancy is such a major concern, wouldn’t the best solution be sex education, the same as any child needs? Newman has some thoughts on this in Chapter 13:

Nobody really thinks she has to teach her children about sex. I mean, not really, not in the way you might have to teach them, say, how to use a credit card (amazing how fast they catch on to that). Kids learn the basics of reproduction, what goes where, and then their natural curiosity takes over. They ask a zillion questions, of either you or their idiot friends, and eventually they figure it out.

This strikes me as rather irresponsible. Newman assumes that all parents share her position on this, but I find that very unlikely; at the very least, my own parents were much more proactive than Newman seems to be. Sex education is too important a topic to leave up to chance. Especially when you consider that a key part of autism is struggling with communication, it’s irresponsible to assume that an autistic child will be able to know the right questions to ask, and also that he’ll be comfortable enough to talk about it on his own.

Newman mentions trying to discuss sex with her son, again in Chapter 13:

... it was very distressing that he seemed to not understand anything about reproduction and sexually transmitted disease, never mind anything about affection and romance. Could I let him be in high school—even a high school for other special ed kids—with this degree of ignorance? But I just didn’t know how to broach the subject, because when I mentioned it—“Gus, do you know where babies come from?”—he’d say, “They come from mommies,” and then continue talking about the weather or sea turtles or whatever happened to be on his mind at that moment.

At another point in the book (Chapter 8), Newman describes a time when Gus’s brother teasingly asks him where babies come from, and Gus changes the subject. From this, and from the above quote, Newman assumes that her son knows nothing about sex, but she never considers the possibility that he might be embarrassed to talk about it. This may be because of her bizarre belief that her son can’t feel embarrassment.

From Chapter 6:

But what if you have a child who cannot be embarrassed by you—and doesn’t understand when he embarrasses you? What then? Nothing makes you appreciate the ability to be embarrassed more than having a child immune from embarrassment.

Later in the same chapter:

Do I want my son to feel self-conscious and embarrassed? I do. Yes. Gus does not yet have self-awareness, and embarrassment is part of self-awareness. It is an acknowledgment that you live in a world where people may think differently than you do. Shame humbles and shame teaches. One side of the no-shame equation is ruthlessness, and often success. But if you live on the side Gus does, the rainbows and unicorns and “what’s wrong with walking through a crowd naked” side of shamelessness, you never truly understand how others think or feel. I want him to understand the norm, even if ultimately he rejects it.

This is actually a fairly common misunderstanding for neurotypicals to have: that if an autistic person doesn’t show an emotion the same way that a neurotypical person does, they must not experience that emotion. Still, you’d think that a mother writing a book about her autistic child would make the effort to figure out if her assumptions were true, or at least that an editor might have brought this to attention. Since it seems that no one involved in the book’s publishing process seems to have figured this out, let me clarify: Autistic people absolutely feel embarrassment. In fact, I’d say it’s a major factor in the prevalence of depression and anxiety among autistic people because of the social rejection many if not all of us have had to deal with.

Back to the original point, however: In Chapter 13, Newman looks through her son’s internet search history (ignoring the “tiny flicker of alarm in Gus’s eyes” - because, after all, he can’t be embarrassed, right?) and finds the porn that he’d been looking at. Clearly, then, he has more understanding of sexuality than Newman realizes, but as far as anyone knows, he’s had to learn it from porn rather than his parents.

As anyone reading this probably already knows, Newman has faced a lot of criticism about her book. For the most part, she’s responded to it badly. Some of her reaction can be seen in this article from the Observer:

While Newman’s stories are meant to be humorous, one of the hallmarks of people with autism is that they think literally and have difficulty understanding jokes. Newman knew this and wrote it that way on purpose.

“This book really wasn’t written for an autistic audience,” she said. “It was written for parents, neighbors, people who may love and hopefully will work with someone who is on the spectrum.”

Setting aside the childish implication that anyone who disagrees with her book must not understand it, what stands out to me in this quote is how unreasonable it is to write a book about autistic people and which affects autistic people and then to say it’s not “for an autistic audience.”

A common mantra for disability activism is “Nothing about us without us” - that is to say, we have a right to be involved in things that affect us. In the above quote, Newman stands against this maxim. She assumes that she can say whatever she wants about without being criticized - and that she can communicate her ideas to all of the people around autistic people without any consideration for autistic people themselves.

Newman doubles down on this in a tweet from a few days ago:

Beginning to think well meaning people of #actuallyautistic are in fact enemies of free thought and free speech. Which is not so good, coming from a group who say they’ve been silenced.

This tweet equates us with oppressive censors rather than people who’ve been hurt by her work. She portrays us as unreasonable for opposing eugenics against our community.

We might sigh a small breath of relief from this quote from the Observer article:

“I am much less worried now and hoping to be a grandmother someday,” she [Newman] said. “That’s a result of my son’s growth and my own.”

That may be good news for her son, but it’s far too little too late for the autistic community at large. Her book is still being printed as it was written. We still have to contend with a critically acclaimed book that advocates for eugenics. There is a great deal of ignorance about autism in our society, and now the ideas in this popular book will be what some of that ignorance is replaced with.

#ableism#eugenics#to siri with love#boycotttosiri#OOPS this is still an enormous post#actuallyautistic

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

Notes for the “Asexuality & Academia” Carnival of Aces from an (autistic) asexual academic

Submitted by CJ DeLuzio Chasin

Some Carnival of Aces readers will probably already be familiar with my name 1. I've published several academic papers about asexuality 2. And for a while, I was one of only 2 asexual people writing academically about asexuality (the other being Andrew Hinderliter). There are many more of us now—mostly students. Some are out about their aceness, some are not (so I won't name anyone). My participation in academic writing about asexuality is intrinsically linked with my own asexuality.

This post addresses 2 topics:

why I have written about asexuality academically, specifically as an “out” ace person (and more recently an autistic aromantic asexual)

what's involved in the peer-review process (for people who aren't already familiar with this) and why it isn't (yet) working “properly” for asexuality scholarship

Why / how I somehow ended up being one of the first out “ace” asexuality scholars:

I didn't start out wanting to write academically about asexuality. I actually tried to avoid it and have been studying other things in grad school—asexuality is not the focus of my research. In the first few years of my grad school experience, anything about asexuality beyond the basics (e.g., info that might be found within AVEN's FAQ's) would have been incomprehensible to an academic audience (and therefore unpublishable). Things were so basic that “this research finding has implications for asexual people and by the way, asexuality is a thing” was a viable academic paper/poster/presentation on its own 3. I wasn't really interested in committing myself to a career of doing ace 101 for academics— I was already doing enough of that in my community and everyday life.

But apparently, I can't help myself. Fumbling along hap-hazardly in my life, reacting to various things as the ace I am, there have been a number of times when I've been inspired to throw my thoughts at academic audiences. (Afterall, I am one of the aces with the capacity to produce academic-speak relevant to the specific disciplines primarily generating asexuality scholarship, and I was apparently one of the first to endeavour to do so.) At this point, I've published more about asexuality than anything else, so I've had to admit to myself that, despite my intentions, I'm something of an asexuality scholar. Part of that, though, is that I've been largely out of the “academic game” for the past few years for medical reasons— hopefully temporarily. The type of theoretical work involved in my writing about asexuality fits better within the context of my current limitations than, say, the type of intensive data-driven qualitative work involved in my ongoing (non-asexuality-focused) research. (The same applies to clinical-audiological applications of probability theory—my second-place topic, entirely unrelated to my main research area.)

The academic asexuality writing that I've done has been in my capacity as a member of a community that other academics and clinicians were studying (or treating), albeit as an academically inclined one— certainly not as “the voice of that community”, but nevertheless as “a voice from that community”. This writing is grounded in who I am as an ace person, saying things I have to say because I'm ace (largely either implicitly or explicitly in response to various misunderstandings surrounding asexuality in academic and popular spaces). For this reason, I have engaged in this writing as an “out” asexual person. The asexual part of my experience and identity matters to my academic writing about asexuality.

For similar reasons, I've also named some other aspects of my experience in this writing—specifically situating myself also as aromantic and autistic 4 in contexts where those things were specifically relevant. Naming myself publicly as autistic is something I thought long and hard about, especially because I can't take it back and don't know what the long-term professional consequences might be. However, academics have now started discussing “autism” when considering whether asexuality might “represent a symptom of a mental disorder (or a mental disorder itself,)” 5 even if some endorse a paradigm of neurodiversity or “neuro-atypicality”6. Because of this, I felt it was important for me to declare my presence as an autistic asexual within the academic conversation. Especially as someone whose name would already be recognisable to many asexuality scholars, situating myself as autistic partly functioned as an assertion that at least one of us autistic aces has been part of asexuality scholarship from early on (and therefore that others may already be present too).

At the same time, I am mindful that my (autistic) asexual positionality limits the kinds of arguments people would be willing to accept from me. Who I am, and the space I occupy in society, really matters to the academic writing I do about asexuality. My asexuality doesn't matter because I think it will make non-ace academics take me more seriously— I think my own asexuality actually makes some people less inclined to take me seriously when writing about asexuality. (In contrast, my whiteness does not make people less likely to take me seriously writing about asexuality, even if perhaps it should— my whiteness means that my asexual experience is very specifically a white asexual experience.) The reason my asexuality matters to my academic asexuality writing is because it's part of why I'm doing that writing in the first place... even if it limits what kinds of arguments I can make “work”. That kind of limitation is also part of why it's not always safe for people (especially students) to be “out” about various aspects of their identities, why I am cautious about which parts of my experience I share, and why I have chosen to keep certain things off the academic/public record. My interest in asexuality scholarship isn't “academic” really: it's personal and political. This isn't my career— it's my life.

And in deference to Chrysocolla Town's comment about scholars “who insist in presenting asexuality as an messianic ideology that will not only end cisheteronormativity, but also the patriarchy, traditional politics and capitalism”... I should note that I do believe that an ace-friendly social context would be radically different than the ones we have today. I believe that in order to re-shape societies in such a way that they would become genuinely hospitable to ace folks, some fundamental social changes would have to happen, including ending both cisheteronormativity and patriarchy. I don't believe that asexuality will create those changes, just by existing. But gosh darn it, I will work toward the revolution. (As I said, this is my life.)

Demystifying the Peer Review Process (as it applies to asexuality scholarship):

Anyone in academia will already be familiar with the peer review process, but there are a lot of ace community members who read the asexuality literature who've never been through grad school or the scholarly peer review process. I strongly believe that asexuality scholarship should be accessible to (non-academic) ace community members. Part of understanding the academic literature, though, is understanding its context. Academic publications need to go through the lengthy, complicated peer review process. Since ace discourse and community have developed so quickly, the landscape of asexuality has time to shift between when articles are first written and when they are finally published. Also, while the peer review process generally functions to improve the quality of scholarship by making it more of a collaborative project, that isn't really working yet when it comes to articles about asexuality, for various reasons.

So here's some info:

what happens during the peer review process?

making required changes while keeping the integrity of the text

post-acceptance: copy-editing, copyright transfer agreements and “open access”

quality of peer review and “relevant expertise” to review asexuality-related works

Logistics: what happens during the peer review process?

When an author submits something to an academic journal, the editor has a quick look at it. As long as the article seems like it reasonably fits the scope of the journal and the submission guidelines (e.g., it's the appropriate length), then the editor passes it along for peer review. The editor invites reviewers who have “relevant expertise” (based on their publication record or recommendations from colleagues with “relevant expertise”). For most scholarly publications, reviewers are not paid to review articles— it's considered a type of “academic service” that people participate in voluntarily because it's necessary to the project of having peer reviewed journals. In psych and social sciences, there are often around 3 reviewers. Things might be different in other fields of study.

The process is supposed to be “blind” (the reviewers aren't supposed to know who wrote the article, and the authors aren't supposed to know who is reviewing it). Invited reviewers who agree are sent an anonymous version of the manuscript and have a set amount of time to write up comments on the paper. (Reviewers who decline are often asked for recommendations of colleagues to serve as reviewers for the paper.)

Reviewers are tasked with giving (ideally constructive) feedback to authors and recommendations to the editor— for example, about whether the article should be accepted for publication, accepted conditional on some revisions, rejected but invited to resubmit when changes are made, or rejected outright (and not invited to resubmit the piece). Different journals have different options. In my discipline, reviewers have about a month to submit their reviews (although some journals have longer or shorter time frames). Reviewer time frames might be different in other disciplines. Depending on the journal and the editor's workload, sometimes the editor makes a decision quickly, while at other times, it takes months after the reviews are in.

The editor looks at the reviews and makes a decision, informed by the reviews but not necessarily limited by them—editors have a lot of discretion. The editor sends a decision letter to the corresponding author which includes their own feedback, saying which changes are mandatory and which are more discretionary. The letter includes the anonymous reviews in their entirety. Sometimes the editor interjects comments into reviews if the editor has a reason to disagree (or to tell the author that they either must follow or alternatively don't need to follow the reviewer's particular recommendation about something).

Typically, the author revises the piece and resubmits it along with a letter explaining how they incorporated the reviewer feedback, and if they didn't follow a particular reviewer recommendation, justifying why they didn't. Depending on the editor's original decision, that might be the end of things and the paper gets accepted, or it goes back to the same reviewers (or occasionally to a new set of reviewers if the original reviewers don't agree to re-review the paper).

Sometimes (but not always) reviewers get to see the other reviewers' reviews (also anonymous to each other)— typically though only after they've submitted their own review and/or after the decision letter goes out. Sometimes (but not always) reviewers get to see the decision letter send by the editor to the corresponding author. As the decision letter is typically addressed to the corresponding author, this can lead to anonymous reviewers finding out the authorship of the paper (meaning that reviewers might know whose work they are reviewing when they re-review manuscripts).

The pragmatic balancing act of revisions: making required changes while keeping the integrity of the text

There are often changes that are required in order for the piece to be published. If the anonymous reviewers want you to explain basic stuff, you need to include that explanation. (Often this is helpful because if they don't understand what you're talking about, chances are that your readers won't either. But it also means that a lot of the content will be redundant for ace community folks reading the research.) But the flip side of that, since journals have pretty strict word-limits (or page limits) is that you can only do so much in a particular paper. If the area of study (like asexuality) is still relatively new, it might not be possible to get to the more advanced analyses in a paper until at least someone publishes the basic introductory overview in an academic space. (Even if that info is published in many non-academic places already, academia requires the very basic things to be established in academic journals before authors writing about more complex ideas can take any of that content for granted.)

If your editor wants you to talk about a particular area in the literature, then you need to talk about it—you don't necessarily need to take the position the editor takes toward that literature, but you do need to address is. (For example, the only reason I discussed research measuring physiological genital arousal in my 2011 paper was because this was one of the editor's requirements. My discussion was a fairly harsh critique of that line of research, but I had to include something about it even though I would have preferred to avoid it entirely for various reasons.)

Different journals have different politics and particular topics that are considered important to address or even sacrosanct. While any decent editor will allow pieces from various different perspectives, including ones with which they personally disagree. Nevertheless, not everything will be acceptable in any given journal. The review process can sometimes be a balancing act trying to preserve the integrity of the piece while making it acceptable to the journal. This isn't always possible (but in theory authors will pick journals where their work will “fit”). Ideally, the final article will communicate something the author believe in, even if it's not the same thing the author set out to communicate in the first place.

Understandably, the peer review process often takes a long time. Depending on how many rounds of reviews happen, how long they take, the editorial queue, and how much time passes between the piece being accepted and actually being published, it's possible that a couple years will have passed between when you first submitted the piece and when it comes out. The discursive landscape can change so radically in that time, especially in the context of asexuality. Journal often list the “submitted on” and “accepted on” dates (along with other dates for revisions, etc.) when the articles are finally published. And many articles are published rather quickly “online first” these days (even if they aren't assigned to a journal for a significant period of time).

There's a lot that goes into shaping academic papers beyond what the people writing them have to say that's worth considering when you pick up an academic paper. Even academic papers are artifacts that are necessarily embedded within particular contexts and are best understood in that context. Why was a piece written the way it was? Why did an author make a particular argument— what other arguments were they explicitly or implicitly responding to? Some part of the “why” should ideally be because it's what the author wanted to say. But some of the answer will always have to do with what went on behind the scenes. Academic articles are strategic texts, created in particular contexts for particular purposes and with definite limits and limitations (like length)—just like other texts, except that the academic part of the context isn't necessarily obvious or accessible to readers.

After a paper is accepted: copy-editing and copyright transfer agreements and limits of “open-access”

When a paper is accepted (and any needed revisions submitted), it needs to be typeset. Depending on the timeline of the journal—whether they wait to typeset it until the issue of the journal comes along where it will finally appear, or whether they typeset it right away and post an “online first” version online, before it actually appears in an issue—the wait-times vary. But once it reaches typesetting, there's usually a quick turnaround time.

Authors might have a week or so to look over and provide corrections to the galley proofs. (This is important because sometimes they accidentally chop off a chunk of text, or maybe the editor re-words something to streamline the writing style that ends up completely changing its meaning. Or maybe they spell your name wrong repeatedly, or completely forget to include the names of co-authors...) Usually changes at this stage are supposed to be very small, and literally correcting errors that they make, but this is also the last opportunity to correct any content-errors (or to add any last minute details, especially if they are really small in terms of wording changes).

Typically, it will also be necessary for authors to sign over the copyright of the work to the publisher. Different journals have different copyright transfer agreements. This is a complicated issue. (It is extremely rare for journals to allow authors the possibility of keeping the copyright themselves, and Feminist Studies is the only journal I know of that does this.) Sometimes the copyright transfer agreements go as far as to prevent the authors from re-using their own work (or requiring that they pay the journal for the privilege of using it, just like anyone else)! They almost always disallow authors from posting the final version of their text online, either ever or for an initial period of time (e.g., 1-2 years after publication).

Often journals allow authors to go with the “open access” option where their work will be “open access” (i.e., not behind a paywall and therefore freely available online) forever. The catch, unfortunately, is that authors typically have to pay a fee of several thousand dollars 7 for this option, though there are some universities (especially in various countries in Europe) which pay the fees for their people. Basically, (if you're not from one of those universities), if you have a fancy research grant that will pay the fee, you can have your work be freely available, but otherwise, the paywall is unavoidable.

While there are a handful of “open access journals” (where all content is freely available), the quality of the peer review and standard for publication is (at this early stage) suspect in many of them which are legitimate scholarly publications; and many other “open access journals” are predatory journals (that charge authors fees to have their work published, and often forgo the peer review process entirely). Fortunately, legitimate scholarly open access publications are increasingly establishing themselves, particularly in the humanities— often as “online only” journals. Many academics in fields where there are viable open access journal options are choosing only to publish in those journals. (Unfortunately, the overwhelming majority of “open access” journals in psychology—where much of the asexuality scholarship is coming from— are predatory journals.)

The journals themselves are directly making money from the publications, but they're alone in that benefit. Authors don't get paid for their publications in academic journals. In contrast, for example, if a fiction periodical or a newspaper include a piece in their publication, the authors—the fiction writer or journalist—will typically get paid for their work. Academic journals don't work that way. 8

Instead, this is in a system where academic publications are supposed to be written by professors—professors being paid to do academic activities including writing, and the publications themselves are “products” proving their productivity. Other people who write academic papers aren't being paid to do it. Any personal benefits of publishing are indirect. For example, grad students' publications help their careers insofar as they might ultimately lead to jobs (or at least are necessary preconditions for employment). And tenure-track faculty need to publish a certain number of papers in order to get tenure (i.e., “publish or perish”).

If academics aren't sharing their work publicly, it's generally because doing so would be breaking the law and risking significant fines and/or being banned from future publishing in scholarly journals... not because they'll loose money.

Quality of peer review and “relevant expertise” to review asexuality-related works

Until a couple years ago, it was almost guaranteed that most or all the people serving as anonymous peer reviewers for papers on asexuality were themselves only vaguely familiar with asexuality and existing asexuality scholarship. Now, from what I can tell, it's kind of hit and miss.

I have certainly had feedback from reviewers on my own work, and seen feedback on other people's work from co-reviewers, that revealed that those reviewers either did not know what they were talking about or didn't have the background to give meaningful feedback. This is slowly changing, as more and more people get involved in asexuality scholarship and therefore find themselves in the pool of people being asked to review potential publications.

However, with a few notable exception, most of the people working on asexuality-related topics are students (and early career professors). That's not a bad thing, but it does mean the the people publishing about asexuality generally have less experience with the peer review process than people publishing in many other areas 9. And that will impact the learning curve of new reviewers. People aren't typically ever formally “taught” how to give peer reviews. Reviewing is a skill people develop as they go, and model after the reviews of others on their own work, sometimes under the guidance of an academic supervisor. Students generally have had fewer reviews of their work to learn from. Also, students studying asexuality will generally be less likely to have invitations for peer review passed along by their supervisors than students studying other things (because their supervisors generally aren't reviewing asexuality-related manuscripts).

Typically (in my field at least) it is unusual for someone who is not at least a senior PhD student to be asked to review an article, and even then, they are often invited by referral from a supervisor. (Even if a senior student hasn't yet “proven” their expertise to their colleagues through their publications, their supervisor would know if they are ready for the tasks and can appropriately refer them.) This means that students studying asexuality will have to have garnered the attention of people who don't work directly with them (i.e., via their publications) in order to get invited to serve as peer reviewers. Fortunately, the number of people publishing about asexuality has massively increased over the past 5 years.

I am hopeful that within the next few years, most of the people serving as peer reviewers for manuscripts about asexuality will actually have “expertise” in asexuality / asexuality scholarship (and not just tangentially relevant “expertise”). And I believe that will significantly improve the quality of the peer review process.

Endnotes:

People are constantly misspelling my name, mistaking the two-letter “CJ” first-name for initials. My actual initials (“ “C. D. C.”), by sheer unfortunate happenstance, coincide with a major US body focused on disease (i.e., the CDC). ↩︎

Despite my somewhat technophobic sensibilities, I have a very rudimentary website for the sole purpose of making my asexuality-related work available to people in the community. Links to some of my papers are available there. However, because of how copyright transfer agreements work, what I'm legally allowed to post online is limited. But I am allowed to e-mail articles that are only available behind a paywall to people who specifically ask me for them (so please do!). My brother set up my website for me (in about 15 minutes) in a format I'd be able to update myself. As might be obvious to more technically inclined folks, it's a subdomain of his professional composer website—which is significantly snazzier than my simple list and which hosts some of his music for people to check out. ↩︎

For instance, this is a poster I presented in 2009 at the Canadian Psychological Association conference. In order to present it, I needed to give some asexuality 101 just so that people could follow what I was saying. Eventually, I'll get around to writing up it up as a paper now that I wouldn't have to spend a significant chunk of the paper explaining asexuality and justifying its existence. ↩︎

Chasin, C. D. (2017). Considering Asexuality as a Sexual Orientation and Implications for Acquired Female Sexual Arousal/Interest Disorder. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46 (3), 631-635. DOI: 10.1007/s10508-016-0893-1. [currently available without a paywall] ↩︎

Brotto, L. A., & Yule, M. (2017). Asexuality: Sexual orientation, paraphilia, sexual dysfunction, or none of the above? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46 (3), 619-627. DOI:10.1007/s10508-016-0802-7. [currently available without a paywall] ↩︎

Scherrer, K. S., & Pfeffer, C. A. (2017). None of the above: Toward identity and community-based understandings of (a)sexualities. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46 (3), 643–646. DOI: 10.1007/s10508-016-0900-6. [currently available without a paywall] ↩︎

As much as peer-reviewed academic journals rely on unpaid service from academics to keep them functioning, the journals themselves are for-profit enterprises and not social services, for better or worse. Journals make money from the work of authors. The justification for charging very large fees for “open access” seems to be for the journal to get money upfront to offset the “lost future revenues” from article-sales that will no longer happen. ↩︎

Book-writing is the only forum where academics might directly benefit financially from their writing, and even then, that's usually limited to earning a small portion of the profits from writing/editing a book that sells many copies (i.e., the editors of popular first-year textbooks make significant money from them). Even then, contributors to edited books—e.g., books with pieces with a number of different authors— typically don't get any financial compensation at all, just like for journal articles. And books about more specific topics or “upper-level” textbooks (often written by a single author) typically sell few copies, so authors' royalties from them are typically also minimal. ↩︎

It also means that students researching asexuality don't benefit from the expertise of their supervisors as much as students doing other research, which can impact the ultimate quality of the work. Even single-author papers are typically informed by collective scholarship— and this is especially true for student-led publications. The networks of people able to add meaningful contributions to asexuality-related work are still underdeveloped: supervisors and peer reviewers have themselves mostly been topic-novices. So this work is going to be at a disadvantage when it comes to looking a the overall calibre of the scholarship. Hopefully this will change as these former students move into more senior positions and start supervising students of their own. ↩︎

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

The following is the email I sent to Sesame Street, using the link above.

I highly recommend reading this article by Autism Self Advocacy Network if you want to know more about this issue, and why this could be extremely dangerous for autistic children.

As an autistic person, I cannot condone your partnership with Autism Speaks.

A brief summary of what is to come:

Autism Speaks:

demonises autism

promotes negative attitudes towards autism

and fundamentally misunderstands the nature of autism

This attitude is evident in Sesame Street's recent work in autism awareness:

e.g. "What to Say to a Parent of a Child With Autism" and (for similiar reasons) "Taking Care of the Caretaker” (chosen due to being quick examples I can find on your site within five minutes (not including videos as those are less accessible))

e.g. The 100 Day Kit actively encourages parents to blame family difficulties on their autistic child - "When you find yourself arguing with your spouse… be careful not to get mad at each other when it really is the autism that has you so upset and angry" and claims that a child can "get better" from autism

Sesame Street as an organisation should know better due to its previous partnership with Autistic Self Advocacy Network (ASAN)

Autism Speaks is an organisation that demonises autism - presents it as a curse that will tear apart families and ruin children's lives, which is not conductive to the spread of autism awareness, nor does it help when trying to genuinely aid autistic children. This bias is actually reinforced within Sesame Street's own article: "What to Say to a Parent of a Child With Autism". While the sentiment of "How can you, a person without autism, help care for those who have autism?" is a genuinely admirable one, and I applaud you for trying to address it, this article is not helpful in any way. One of the most egregious parts of that article is the suggestion that people should ask parents of autistic children if they could "come with [aforementioned parent of autistic child] to appointments for support". First: the idea that the parent of an autistic child would a) have "appointments" (while this is helpful in some cases, this is far from a universal constant) and b) would need "support", as presumably the impossible drain of caring for an autistic child is too much. This advice is completely inappropriate - would this apply in any equivalent case, but without an autistic child? You wouldn't invite a friend to your divorce proceedings "for support" - that's widely understood as being completely inappropriate. What entitles the person asking to have presume any involvement in this?

A much better piece of advice would be to say this: you support an autistic person/person caring for an autistic person by treating them with kindness. You listen to them, acknowledge their problems and aid them in sorting out their lives. Any person with empathy should be able to understand and tailor their support to their friends problems, whether that be with an autistic child or a difficult break-up.

Autism Speaks also seeks to cure autism, as evidenced in the 100 Day Kit, saying that a child can "get better" from autism. This shows a fundamental misunderstanding in that autism is a behavioural and social disorder - a mental disorder in that it cannot be cured (as opposed to a mental illness) and a behavioural and social disorder in that it forms a genuine part of who I am as a person. There is no me without my autism - I would be completely different without it. This applies to people with both "high-functioning" and "low-functioning" autism - unlike how Autism Speaks likes to present it in some of its campaigns, autism is not holding your non-verbal child hostage; it is a part of your child. Separating autism from the child in this way dismisses the issues that the child goes through, as something that is not truly a part of them and something they can overcome. While people with autism must make allowances for the fact that we live in a society that does not cater to us, society must also have a little bend for us - if autism and the person who has said autism are presented as two separate entities, that lets society off the hook for not giving us the necessary leeway.

This partnership is particularly tragic in light of Sesame Street's previous partnership with ASAN. ASAN is openly against Autism Speaks, and unlike Autism Speaks, ASAN is actually run by autistic people.

In partnering with Autism Speaks, Sesame Street has become a part of the spread of negative stigma (100 Day Kit telling parents to go through the five stages of grief after finding out their child is autistic, as if someone had died) and misinformation (encouragement of pseudoscientific "autism diets") about autism. I hope you take the steps to withdraw from and erase evidence of your partnership with Autism Speaks, before you do real damage to an autistic child.

Sincerely, [redacted]

Well, I have three important announcements to make today.

1) Requests and submissions are now open! Feel free to check through the rules and the blog to see who’s been requested before before requesting your character.

2) It’s my birthday-I’m 26 today!

3) In lieu of ‘happy birthdays’, please sign this petition telling Sesame Street to stop partnering with Autism Speaks. I don’t know if it’ll make a difference, but we can damn well try. And trust me, it’s better to fail trying than to do nothing and wonder ‘what if’.

http://chng.it/CQZZ7YmR8R

-Mod Rowlf

#autism#aspergers#sesame street#fuck you autism speaks#autism speaks#yes im tagging the fuckers#i want all of their supporters to see this

236 notes

·

View notes