#but if i elaborated more the post would wind up like 10 miles long

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Hi! Can I pelqwe request head canons for Shanks, Ace, Sabo and Benn for their Female S/O flinching during an arguement? Tysm in advance❤️❤️❤️ :) (also if u don’t write for Benn, just leave him out haha)

I actually only take 3 characters at a time for hc requests - and I remember veeery little about Benn, so yeah I’ll leave him out lol. thank you for sending anon!

Fem!S/O flinching during an argument: Shanks, Ace, & Sabo

Shanks

↳ Shanks hardly ever becomes genuinely angry, especially toward his loved ones. I don't see him as the type who becomes very animated or loud at those times, but there's just an intensity to him that's quite off-putting. Like there's something so obviously boiling under the surface and you don't know whether it's about to explode. So when the flinch happens, everything was so silent that it was unsettling. He had just stood up from his chair, and then his s/o was suddenly skittering back, instinct hurrying her away from his heavy glare.

↳ It probably takes a few moments for Shanks to connect the dots & realize what just happened. Usually he's always got something to say, but in this situation he really doesn't know what to say. So he'd just take his seat again, hoping the height reduction would helps ease the intimidation factor.

↳ I could actually see him sort of nervous-laughing? Just like a breathy, disbelieving huff of laughter, while he rubs a hand over his face. Once he has his mind a little more together he'd probably say something like, "I'm sorry, Y/N. I– Here, I'm gonna calm down. Let's just calm down, yeah?" And he'd definitely take a few deep, deliberate breaths to make sure he does calm down, because Shanks hates the look of fear that crossed her face a moment ago. He never imagined he could ever be the cause of it.

↳ He'd open his arm to her after a little bit, hoping she'd come and sit with him. He's so relieved when she accepts him, letting him hold her in his lap and stroke his hand up and down her back and apologize. He makes a hundred promises to make it up to her; he'd probably yield on their earlier argument, too. He feels like it's not worth arguing about it anymore if this was the outcome, anyway.

Portgas D. Ace

↳ He is SO distraught. He can't even describe it. Once it really sinks in, it's even worse. His throat goes tight, and he can feel heat pricking behind his eyes, but he really doesn't want to cry. Not in front of her. Because it's really not about him at the moment, it's about how he let his emotions get so out of hand that he made the person he loves afraid of him.

↳ So he doesn't accept it when she comes closer and tries to wipe at his eyes. Ace just takes her hand and apologizes. Profusely. The argument really doesn't matter to him anymore– if it's that important, they can return to it another time. He tells her he didn't mean to scare her, that he'd never even dream of hurting her like that; and if she allows it, he'll draw her in for a hug and hold her and kiss her head until he knows that she believes him.

↳ Ace kind of doesn't know how to act around her for a while after this. All of a sudden he doesn't fully trust himself. And he knows he shouldn't be treating her like a glass doll, but he really can't help it for like a day or two; he probably spends the next few days just absolutely spoiling her as well. He treats her to good food, they do whatever she wants to do, he's always running errands for her. He lost ALL his good-boyfriend points and he needs to make them up to her somehow

↳ Even if this never happens again, even if his s/o promises him she's not afraid, he'll remember it every time they get in an argument. He really tries not to get so heated. He could get pretty mean with his words, but in the future he tries to make absolute sure that none of it leaks into his body language and actions the way it must've back then.

↳ But if it was on a bad day, I could see Ace just... spiraling. He'd feel so mad at himself, but it'd quickly melt into bitter shame. It's one thing for him to annoy or anger her, but to make his partner fear him? He feels like a monster. The memory of her flinching definitely comes back up on those nights when he's already feeling down on himself. He really tries to keep it from her, though, because he doesn't think she should be responsible for how he feels.

Sabo

↳ The second he sees her flinch, he freezes. It's like a mental reset. All his earlier anger drains out of his body, and there's this heavy silence when he realizes what he just caused. And he feels absolutely awful. He's stood there, looking incredibly hurt, before just stuttering out, "Sorry. I'm sorry." He'd probably leave the room, too, even if she tries to ask him to stay– he doesn't want to make things worse for her.

↳ While they're both taking time to cool down, Sabo can't help but wonder if it was something from her past that made her respond that way, or if he was really that frightening in her eyes. He over-analyzes all their past interactions, wondering where this came from. Does she really believe he would lay a hand on her? How many times has he scared her before, and he just never noticed? Has she been afraid of him this whole time they've been together?

↳ I could actually see him going to Koala and asking her all these conspicuously vague but pointed questions... "Am I a scary person? Do you think I'm too violent? Do I intimidate people?" and she's just like Sabo wth are you talking about. (She probably has to talk him down a bit. The boy's having an inner crisis and it shows)

↳ But once he and his s/o finally talk again (probably sometime later that day - Sabo wouldn't let this go unaddressed for too long), he's apologizing immediately. For whatever the argument was about, for getting not controlling his anger, for letting things get out of hand. He really wishes he could go back & change how he acted, but he knows it's not possible. He's another one that never forgets this incident– and he does everything he can not to repeat it.

#shanks#sabo#portgas d. ace#one piece#one piece imagines#not suuuper confident abt this one#but if i elaborated more the post would wind up like 10 miles long#sabo x reader#shanks x reader#ace x reader

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dive Bar Ch. 11/11 - Fin

Pairing: Dean x Sam

Rating: 18+

Summary: After a one night stand with a random college chick turns into a threesome that also featured his little brother, Dean- well, frankly, he panics. What’s even worse than gay panicking? Gay incest panicking. Luckily, Sam winds up being a little more cool about the whole thing than Dean ever would have imagined.

WC: 3,001

Tags: brother/brother incest, loss of anal virginity, anal sex, blow job, incest kink, dirty talk, top!sam, bottom!dean, happy ending - sue me

Beta: @negans-lucille-tblr and @daydream3r-xo

Divider: @firefly-graphics ❤️

A/N: Okay I’m gonna do a separate post with a long sappy note so this post doesn’t become a mile long but TLDR - thank you for reading and coming with me on this wild ride 🥰

Fic Masterlist

Chapter 10

A few weeks later

Another hunt. Another drink. Another dive bar.

Sam killed his beer before Dean could even get his lips around his own, and once he saw Sam downing the drink, condensation running over his knuckles, his lips, down his throat– Dean didn’t care he had lost the game, he just wanted to lick the moisture off Sam’s neck.

“Take a picture,” Sam laughed when he noticed Dean’s staring, “it’ll last longer.” Dean dropped his gaze to his bottle and took a long swig. “Something on your mind?”

“Wh– nope, nothing,” Dean denied, seeing his beer off. “I’m buying right? You want the same?”

“Yeah, sure,” Sam looked suspicious, but let Dean go off to get their second round.

Dean grabbed the bartender’s attention and held up two fingers, pointing to the bottles he was returning, then dropped his head in his hands. God, he had to get himself under control. He couldn’t just zone out every time Sam did something that made him half hard in his jeans – he’d wind up getting them both killed at some point. It didn’t help that every time Sam had tried to fuck him, he’d chicken out the second he got another look at Sam’s dick. He needed to nut up and go through with it already. The bartender pushed new drinks at Dean, breaking him out of his reverie.

When he spun back towards Sam with their drinks, he saw a table of girls a few spots over from them making eyes at Sam, and he noticed one in particular looked exactly his type. She had those ‘come hither’ bedroom eyes, long hair you could wrap your hands up in, great boobs – This is perfect.

“You’ve got an admirer little bro,” Dean teased when he dropped the fresh bottle on the table in front of Sam. Sam glanced up and noticed the girl Dean was talking about, dropping his head behind his hair quickly. Dean caught her eye and gave her a wink before taking a draught of his beer and turning back to Sam.

“Stop being a jerk,” Sam shoved at Dean, “it’s not nice to lead people on.”

“What if I’m not?” Dean held his breath as he watched Sam’s face, unsure of how he was going to react to that.

“What are you asking me, Dean?” Sam fingered the label on his beer bottle – one of his nervous tics – and Dean realised he fucked that up.

“No! That’s – shit, that’s not what I meant. I meant like, what we did before, with Dany, we… y’know.” Dean fumbled through an explanation, but he saw Sam let out a breath and knew he was okay.

“You want to have another threesome?” Sam smirked, bemused, which was better than pissed so Dean was fine with that.

“Why not?” he shrugged, glancing back to the girl, who was still checking them both out, before focusing back on Sam. “We were pretty damn good at it the first time,” Dean grinned, pulling a huff from Sam.

“Yeah,” he shrugged, still smirking at Dean, “it was good.” Sam’s smirking was starting to unnerve Dean a little.

“And, y’know, the past couple weeks have been – awesome, really – but maybe we uh, spice things up again, huh?” Dean waited for Sam to chime in with something, maybe tell him what all the goddamn smirking was about.

“Already getting bored of me, Dean?” Sam’s smirk was actually becoming irritating, now.

“You know that’s not what I meant, stop being a bitch,” Dean grunted. Sam laughed to himself and took another drink. “So, what d’ya say, Sammy?” Dean waggled his brow, trying to draw an answer out of his brother. “Show another gal the time of her life?”

Sam could tell Dean was stalling. He’d been jumpy the past few times Sam had brought up having actual sexual intercourse – his cock in Dean’s ass – saying he wanted it, but not letting Sam go past fingering him open a little. And now Dean was finding another excuse to put it off, and Sam was getting desperate. It was time to give Dean a push off his cliff.

“We can do it again,” Sam nodded, rounding the table so he was behind Dean, and looking towards the girl he’d been pointing out. “But not just yet.”

“Hm?” Dean looked over his shoulder at Sam, puzzled. Sam bent over his big brother, bringing his lips close enough to his ear that he wouldn’t have to shout to be heard in the crowded bar.

“I don’t want anyone else fucking you before I get the chance to do it properly.” Sam felt Dean shiver against him. “Gonna let me fuck you, big brother?”

“Fuck,” Dean exhaled, trying to compose himself behind a swig of his drink.

“How much longer you gonna hold out on me?” Sam scraped his teeth along the back of Dean’s ear, pulling a whimper from him.

“You know what, fine,” Dean stood abruptly, knocking Sam off balance behind him. “You wanna do this? Let’s do this. Get in the car, Sam.”

Sam grinned triumphantly as he followed Dean out of the bar and out to the Impala, back to their motel room for the night.

-

Sam pushed Dean against the door the second it closed behind them. They were good at this part. He could take Dean apart with a few calculated bites along his neck and some very enthusiastic kissing, and Dean was becoming more and more comfortable letting himself be putty in Sam’s hands.

Not that Dean didn’t have the same effect on Sam. A short tug on his hair and Dean’s tongue between his lips and he would melt in his brother’s arms. Dean was a mind-blowing kisser.

Sam trailed his hands down Dean’s arms and grabbed his wrists, pulling him off the wall and towards the bed; still messy from the previous night. He sat Dean down on the mattress and stood back to strip off his shirts. He felt Dean’s hands at his belt undoing the buckle so he could pull his jeans down, and Sam kicked them off along with his boots. Dean went to unbutton his own shirt but Sam stopped him.

“Hey – I want to do that.” Dean gave him a confused sort of smile, but let Sam’s fingers cover his and take over stripping him out of his layers. He kissed Dean again, sucking on his lower lip and licking into his mouth, inhaling his every breath - consuming him. He dragged his fingers over every inch of skin that was revealed as he pulled off the flannel and then the t-shirt, kissing down his legs as he tugged him out of his jeans, before he had to kneel to unlace Dean’s boots. Dean propped himself up on his elbows to look down at Sam, still knelt at his feet.

“I know what you’re doing Sam, so you can quit it now,” Dean griped. “Stop treating me like some blushing virgin, I’m not a girl.” Sam grinned wolfishly and sprang back on the bed once he’d gotten Dean’s jeans off.

“No, you’re definitely not a girl,” he agreed, squeezing the bulge in Dean’s underwear and pulling a groan from his brother. “But I’m still gonna make you scream like one,” Sam breathed against Dean’s lips before he devoured them. “Gonna make you feel so good, Dean,” Sam groaned, pushing his hand into Dean’s briefs and grabbing hold of his length. “Love your cock so much, so hot,” Sam wasn’t sure what he was saying anymore, whatever popped into his head was going straight to his mouth without any filter, which wasn’t helped by the fact that Dean had gotten his hand inside Sam’s boxers and was jerking him off now too.

“God, wanted this for so long,” Sam moaned, sucking a bruise into the join between Dean’s shoulder and his throat. “Thought about fucking you so much,” Sam admitted, to hell with embarrassment at this point. “When I went home with that guy from the bar, I wanted it to be you. I thought about you when I was fucking him – said your name when I came inside him.”

“Jesus, Sammy,” Dean groaned, his mocking tone not disguising his arousal very well, “s’cute you’re so sweet on me.”

“Shut up,” Sam bit at Dean’s lip gently, “before I make you.”

“So then make me,” Dean growled, flipping them so Sam was below him and he could grind their erections together while he sucked his own mark into Sam’s skin. He dragged his lips down Sam’s chest, goal evident. Sam didn’t want to get too carried away, but he’d be lying if he said he didn’t want Dean’s mouth on him; blowjobs were a skill Dean had really been perfecting over the past few weeks.

Dean hummed happily when he got Sam’s cock in his mouth, and Sam relished the wet warmth that enveloped him, thrusting up into Dean involuntarily.

“Someone’s eager,” Dean chuckled before taking Sam back in his mouth.

“Someone’s being a tease,” Sam grunted, hauling himself up on his elbows so he could pull Dean off his dick and throw him onto his side on the bed. They kissed again, Dean wrapping his arms around Sam and getting his hands in his hair, like he knew Sam liked. Without breaking from the kiss, Sam grabbed for the lube that was still under the pillow from the previous night.

Dean was expecting what came next, and didn’t flinch when he felt Sam’s fingers trailing over his ass and dipping between his cheeks to find his entrance. Sam kept the touches light, teasing – soothing – until he felt Dean relax against him again.

“I want you to do it,” Sam breathed against his neck. Dean didn’t follow.

“Want me to do what?”

“Get yourself ready for me,” Sam elaborated, kissing along Dean’s neck. “Want you to finger yourself open for me.”

“Why?” Dean wasn’t necessarily opposed to the idea, but Sam had always been the one to do this part before.

“Because you’ll be able to feel when you’re ready, won’t be as nervous.” Sam kissed further down Dean’s chest, stopping to suck one of his nipples into his mouth, and pulling a gasp from Dean. “Plus, I think it would be hot,” he grinned up at Dean. “Want to see fucking yourself so good on your fingers that you’re begging for my cock.”

Dean felt his cock twitch against Sam’s hip, and he had to admit, when he said it like that, it did sound fucking incredible. “Yeah. Yeah, okay.” He grabbed the lube from Sam and turned over so he was on his knees, letting his shoulders drop to the mattress, his ass in the air.

“Fuck, you look hot like that,” Sam moaned. Dean could see Sam was touching himself as he watched and found that he liked putting on a bit of a show.

“You like watching me, Sammy?” Dean shivered as he pushed one slicked-up finger into himself. “Like thinkin’ ‘bout how much you wanna fuck me while you touch yourself?” He started to move his finger inside himself, in and out, searching… “Like thinkin’ about your big brother when you get off?” Dean moaned when his fingertip skirted by the spot he was trying to find.

“Fuck, yes,” Sam breathed, eyes fixed on Dean’s finger moving in and out of his ass. “Add another one, Dean.” Dean did as he was told and added a second finger, hissing at the stretch. “There you go.” Sam reached between his legs to play with Dean’s cock, and his hand felt so fucking good against his skin. That, coupled with the fact that Dean had managed to find the spot inside his ass Sam had shown him that made everything go fuzzy, Dean was pretty blissed out. “Think you can do one more for me?” Sam squeezed his fingers in a ring around the head of Dean’s cock, drawing another whimper from him.

Dean nodded and pulled his hand away to add more lube, and went back to his hole with three fingers. He pressed at his entrance slowly, testing the give, and found that when he finally pushed his fingers inside, he loved how full he felt, and he loved the small tingle of pain that was mixing with the overwhelming pleasure.

“Fuck.” Pumping his fingers into himself faster, Dean groaned wantonly, unreserved, relaxing into the feeling of being stretched so open.

“Think you’re ready?” Sam asked, obviously hopeful.

“Yeah,” Dean gasped, “yeah, Sam, want you. Please.” He let himself sag to the bed and rolled over onto his back. Sam kissed him shortly and pulled back, searching his eyes for one last okay, before Dean felt the tip of Sam’s cock pressing against his entrance.

When Sam pushed inside of him, Dean’s whole world whited out. He was bigger than the fingers he had been working himself with, and so fucking hard, but Dean loved every second of it. He couldn’t believe he’d made Sam wait to do this for so long.

“Oh my god, Sam, fuck -“ Dean panted.

“Told ya I’d make you feel good,” Sam groaned, pushing in a little more. “You’re doing so good, De, taking me so fucking good, so fucking tight.”

“Goddamn, you really never shut up, do ya Sammy?”

“Sorry,” Sam ducked his head into Dean’s neck, embarrassed.

“No, hey,” Dean pulled Sam back up to face him. “S’okay little brother. I, uh – I kinda like it.”

“Yeah?” Sam’s grin was unsure, but relieved.

“Yeah,” Dean nodded, kissing along the column of Sam’s neck, sucking the skin between his lips to leave another mark. “Never would have thought you’d be so good at dirty talk.”

“That’s not the only thing I’m good at,” Sam smirked, and pressed the last inch of himself inside Dean, pulling a muffled ‘fuck’ from Dean. “You still good?” Sam checked.

“So good,” Dean moaned, pressing his hips back into Sam’s, like he was hoping to fuse the two of them together permanently.

“Can I move yet, or do you need a minute?” Sam asked.

“Would you just shut up and fuck me alrea –” Dean’s gripe was cut off abruptly by a moan when Sam pulled his hips back and slammed home again. Dean couldn’t get too many words out after that – the pleasure thrumming through his body had short circuited his brain. All he could think about, all he could feel, was Sam’s cock moving inside of him. The hot drag of Sam’s flesh against his was intoxicating, and he felt himself fucking his hips back up into Sam’s without necessarily deciding to do that.

“Shit, that’s it baby,” Sam hissed through gritted teeth, picking up the pace of his thrusts. “Feel so good Dean.” Dean could barely manage a whimper in acknowledgement. Sam leaned back on his heels to get better leverage, moving Dean’s ankles to his shoulders, and on the next thrust in he found Dean’s prostate, which Dean’s choked whine made very clear. “There we go,” Sam grinned down at him. “Bet you're glad I didn’t let you go home with that girl now, huh? No girl could ever make you feel like this, could they?”

“No,” Dean admitted. “Fuck no.” And it was true. Sex had never felt this intense before, this all-consuming, this nerve-frying. Sam hadn’t even touched his cock since he’d pushed inside him and he was already so fucking close to losing it. And he knew Sam could tell, too.

“You gonna cum for me, big brother?” Sam started fucking into him even harder, quicker. “Gonna cum with your little brother’s cock inside you?” Dean thought he nodded, but to be honest, he couldn’t be sure. “Good,” Sam groaned, “because I am so fucking close.”

Dean reached up to pull Sam back down to him. He wanted every inch of his body covered by Sam’s, wanted to drown under him. They kissed fiercely, tongues tangling and teeth clacking against each other as Sam fucked him faster and faster. The sweat coating their bodies made for an easy slide of Sam’s stomach against Dean’s cock and that extra bit of pressure was exactly what he needed to finally spiral out of control. He came noiselessly, any sound he might have made dying in his throat as every muscle in his body seized up. Thick white spurts caught against the hair on their chests, smearing between them.

“Holy shit,” Sam gasped as he suddenly ceased his frantic pace and froze, cock buried inside of Dean as deep as it could go. “Fuck,” Sam’s whimper was barely audible, but it was there. Dean’s hands absentmindedly combed through Sam’s hair as they both calmed down their breathing, soothing his little brother like he’d always tried to do, even though, given the circumstances, it probably should have been the other way around right now.

Eventually, Sam pulled out carefully and flopped down on the vacant side of the mattress. Dean dragged the crumpled sheet from the foot of the bed and wiped over his chest, then over Sam’s, to get the cum off before it dried too badly, before dropping back against the pillows and rolling into Sam’s side. He felt Sam startle for a moment before pulling Dean against him, arm curling around his shoulder.

“Hey, you okay, man?” Sam’s voice was soft, like he was worried he would scare Dean off.

“Yeah,” Dean considered, “yeah, I’m good, brother.”

“Not too disappointed I didn’t let that blonde come back with us?”

Dean laughed. “No, Sammy, not disappointed.”

“What if I said that … I thought that – maybe – I wanted you all to myself from now on?” Sam’s eyes caught his, hesitant.

“I’d say…” Dean let sharp exhale and a short laugh. “I’d say, it’s always been you and me. And I’ve never needed anyone else.”

Sam beamed down at him. “Good enough for me.”

Tags: @vulgar-library @tintentrinkerin @negans-lucille-tblr @fandomfic-galore @petitgateau911 @whoreforackles @schaefchenherde @kickingitwithkirk @little-diable @delightfullykrispypeach @hawkerz12 @dylansbabygirl24 @mineshinamary @popsensationnicole23 @spn-problems @donthateme454 @doyouknowsamw @peridottea91 @delightfulbakeryaliendeputy @fictionallemons @natastic @marvelfansworld @half-closeted-bi-girl @je-ai-de-la-amour-pour-dean @kiss-my-peachy-arse @tftumblin @alice101macwil @disneysloot @caitlinvd @crashlyrose @miufel @itsthedoctah10 @leftlokiofpuppy @devilsbbyy @austin-winchester67 @spnobsessed50

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

BLOGTOBER 10/7/2020

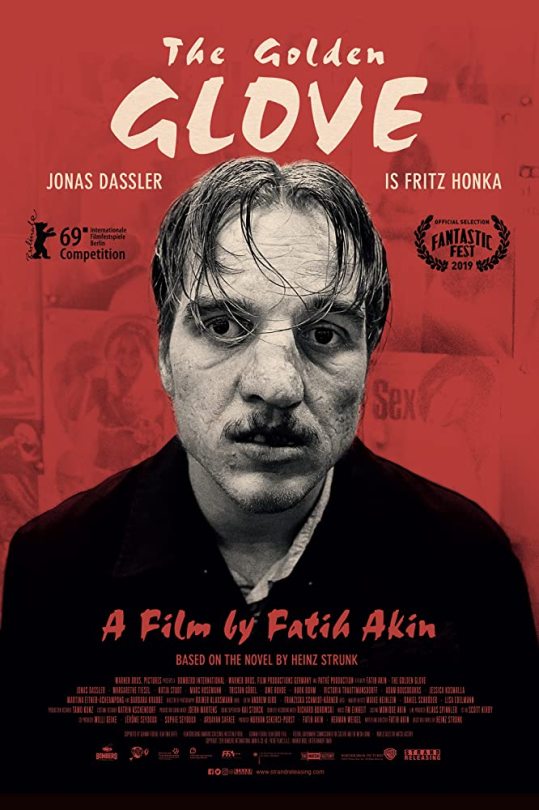

I missed THE GOLDEN GLOVE at Fantastic Fest last year. It was one of my only regrets of the whole experience, but it was basically mandatory since the available screenings were opposite the much-hyped PARASITE. As annoying as that sounds, it was actually a major compliment, since what could possibly serve as a consolation prize for the most hotly anticipated movie of the year? Needless to say, I heard great things, but I could never have imagined what it was actually like. I'm still wrapping my mind around it.

Between 1970 and 1975, an exceptionally depraved serial killer named Fritz Honka murdered at least four prostitutes in Hamburg's red light district. Today, we tend to think of the archetypal serial killer in terms of ironic contradictions: The public is attracted by Ted Bundy's dashing looks and suave manner, and John Wayne Gayce's dual careers as politician and party clown. Lacking anything so remarkable, we associate psychopathy with Norman Bates' boy-next-door charm, and repeat "It's always the quiet ones" with a smirk whenever a new Jeffrey Dahmer or Dennis Nilsen is exposed to the public. The popular conception of a bloodthirsty maniac is not the fairytale monster of yore, but a wolf in sheep's clothing, whose hygienic appearance and lifestyle belie his twisted desires. In our post-everything world, the ironic surprise has become the rule. In this light, THE GOLDEN GLOVE represents a refreshing return to naked truth.

To say that writer-director Fatih Akin's version of the Fritz Honka story is shocking, repulsive, and utterly degenerated would be a gross understatement. We first meet the killer frantically trying to dispose of a corpse in his filthy flat, wallpapered with porno pinups, strewn with broken toys, and virtually projecting smell lines off of the screen. One's sense of embodiment is oppressive, even claustrophobic, as the petite Honka tries and fails to collapse the full dead weight of a human corpse into a garbage bag, before giving up and dismembering it, with nearly equal difficulty. The scene is appalling, utterly debased, and yet nothing is as shocking as the killer's visage. When he finally turns to look into the camera, it's hard to believe he's even human: the rolling glass eye, the smashed and inflated nose, the tombstone teeth and cratered skin, are almost too extreme to bear. Actually, suffering from a touch of facial blindness, I had to stare intently at Honka's face for nearly half the movie before I could fully convince myself that I was, in fact, looking at an elaborate prosthetic operation used to transform 23 year old boy band candidate Jonas Dassler into the disfigured 35 year old serial murderer.

Though West Germany remained on a steady economic upturn beginning in the 1950s and throughout the 1970s, you wouldn't know it from THE GOLDEN GLOVE. If Honka's outsides match his insides, they are further matched by his stomping grounds in the Reeperbahn, a dirty, violent, booze-soaked repository for the dregs of humanity. Though its denizens may come from different walks of life, one thing is certain: Whoever winds up there, belongs there. Honka was the child of a communist and grew up in a concentration camp, yet he swills vodka side by side with an ex-SS officer, among other societal rejects, in a crumbling dive called The Golden Glove. The scene is an excellent source of hopeless prostitutes at the end of their career, who are Honka's prime victims, as he is too frightful-looking to ensnare an attractive young girl. These pitiful women all display a peculiarly hypnotic willingness to go along with Honka, no matter how sadistic he becomes; this seems to have less to do with money, which rarely comes up, and more to do with their shared awareness that for them, and for Honka too, it's been all over, for a long time.

Not to reduce someone’s performance to their physical appearance, but ???

To call Dassler's portrayal of Honka "sympathetic" would be a bridge too far, but it is undeniably compelling. He supports the startling impact of his facial prostheses with a performance of rare intensity, a full-body transformation into a person in so much pain that a normal life will never become an option. His physical vocabulary reminded me of the stage version of The Elephant Man, in which the lead actor wears no makeup, but conveys John Merrick's deformities using his body alone. Although there is an abundance of makeup in THE GOLDEN GLOVE, Dassler's silhouette and agonized movements would be recognizable from a mile away. In spite of his near-constant screaming rage, the actor manages to craft a rich and convincing persona. During a chapter in which Honka experiments with sobriety, we find a stunning image of him hunched in the corner of his ordinarily chaotic flat, now deathly still, his eyes gazing at nothing as cigarette smoke seeps from his pores, having no idea what to do with himself when he isn't in a rolling alcoholic rampage. The moment is brief but haunting in its contrast to the rest of the film, having everything to do with Dassler's quietly vibrating anxiety.

Performances are roundly excellent here, not that least of which are from Honka's victims. The cast of middle-aged actresses looking their most disastrous is hugely responsible for the film's impact. These are the kinds of performances people call "brave", which is a euphemism for making audiences uncomfortable with an uncompromising presentation of one's own self, unvarnished by any masturbatory solicitation. Among these women is Margarete Tiesel, herself no stranger to difficult cinema: She was the star of 2012's PARADISE: LOVE, a harrowing drama about a woman who copes with her midlife crisis by pursuing sex tourism in Kenya. Her brilliant, instinctive performance as one of Honka's only survivors--though she nearly meets a fate worse than death--makes her the leading lady of a movie that was never meant to have one.

So, what does all this unpleasantness add up to, you might be asking? It's hard to say. THE GOLDEN GLOVE is a film of enormous power, but it can be difficult to explain what the point of it is, in a world where most people feel that the purpose of art is to produce some form of pleasure. This is the challenge faced by difficult movies throughout history, like THE GOLDEN GLOVE's obvious ancestors, HENRY: PORTRAIT OF A SERIAL KILLER, MANIAC and THE TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE. Describing unremitting cruelty with relentless realism is not considered a worthy endeavor by many, even if there is real artistry in your execution; some people will even mistake you for advocating and enjoying violence and despair, as we live in a world where huge amount of movie and TV production is devoted to aspirational subjects. (The fact that people won't turn away from the Marvel Cinematic Universe movies, no matter how monotonous and condescending they become, should tell you something) How do you justify to such people, that you want to make or see work that portrays ugliness and evil with as much commitment as other movies seek to portray love, beauty, and family values? Why isn't it enough to say that these things exist, and their existence alone makes them worth contemplation?

A rare, perhaps exclusive “beautiful image” in THE GOLDEN GLOVE, from Fritz Honka’s absurd fantasies.

You may detect that I have attempted to have this frustrating conversation with many people, strangers, enemies, and friends I love and respect. I find that for some, it is simply too hard to divorce themselves from the pleasure principle. I don't say this to demean them; some hold the philosophy that art be reserved for beauty, and others have a more literary feeling that it's ok to show characters in grim circumstances, as long as the ultimate goal is to uplift the human spirit. Even I draw the line somewhere; I appreciate the punk rebellion of Troma movies as a cultural force, but I do not enjoy watching them, because I dislike what I perceive as contempt for the audience and the aestheticization of laziness--making something shitty more or less on purpose. A step or three up from that, you land in Todd Solondz territory, where you find materially gorgeous movies whose explicit statement is that our collective reverence for a quality called "humanity" is based on nothing. I like some of those movies, and sometimes I even like them when I don't like them, because I'm entranced by Solondz's technical proficiency...and maybe, deep down, I'm not completely convinced about "humanity", either. However, I don't fight very hard in arguments about him; I understand the objections. Still, I've been surprised by peers who I think of as bright and tasteful, who absolutely hated movies I thought were unassailable, like OLDBOY and WE NEED TO TALK ABOUT KEVIN. In both cases, the ultimate objection was that they accuse humans of being pretentious and self-deceptive, aspiring to heroism or bemoaning their victimhood while wallowing in their own cowardice and perversity. Ok, I get it...but, not really. Why isn't it ever wholly acceptable to discuss, honestly, what we do not like about ourselves?

The beguiling thing about THE GOLDEN GLOVE is that, although it is instantly horrifying, is it also an impeccable production. The director can't help showing you crime scene photos during the ending credits, and I can't really blame him, when his crew worked so hard to bring us a vision of Fritz Honka's world that approaches virtual reality. But it isn't just slavishly realistic; it is vivid, immersive, an experience of total sensory overload. Not a square inch of this movie has been left to chance, and the product of all this graceful control is totally spellbinding. I started to think to myself that, when you've achieved this level of artifice, what really differentiates a movie like THE GOLDEN GLOVE from something like THE RED SHOES? I mean, aside from their obvious narrative differences. Both films plunge the viewer into a world that is complete beyond imagination, crafted with a rigor and sincerity that is rarely paralleled. And, I will dare to say, both films penetrate to the depths of the human soul. What Fatih Akin finds there is not the same as what Powell and Pressburger found, of course, but I don't think that makes it any less real. Akin's film is adapted from a novel by Heinz Strunk, and apparently, some critics have accused Akin of leaving behind the depth and nuance of the book, to focus instead on all that is gruesome about it. This may be true, on some level; I wouldn't know. For now, I can only insist that on watching THE GOLDEN GLOVE, for all its grotesquerie, I still got the message.

#blogtober#2020#the golden glove#fatih akın#heinz stronk#jonas dassler#margarete tiesel#difficult cinema#horror#slasher#serial killer#period piece#adaptation#historical#biopic#fritz honka#i may have been watching a lot of powell and pressburger movies recently#sorry...

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scientists are putting antibiotics into the ocean—on purpose. And it's our only hope.

New Post has been published on https://nexcraft.co/scientists-are-putting-antibiotics-into-the-ocean-on-purpose-and-its-our-only-hope/

Scientists are putting antibiotics into the ocean—on purpose. And it's our only hope.

Struggling crops. Salty aquifers. Invading wildlife. Piles of dead fish. The Sunshine State feels the squeeze of environmental change on its beaches, farms, wetlands, and cities. But what afflicts the peninsula predicts the perils that will strike north and west of Apalachicola, and so it demands our attention. If Florida is in trouble, then so are we all.

Just off the coast of the Keys, wind-driven swells toss our little boat like a bath toy. Nearly 30 feet below, in the blue murk, divers tend their plot: a sparse patch of sea-floor 10 meters square.

One swimmer hovers over a brain coral the size of a fishbowl, studying its corduroy surface as she readies a syringe in one hand. She dispenses a droplet of white putty and dabs it onto the edge of the colony.

Back at the surface, Karen Neely, a Nova Southeastern University marine biologist with the easy manner (and tan) of someone who spends her professional life on the water, scans survey sheets marked with terse scribbles of observation. Coral reefs are bleaching around the globe, but Neely and her collaborators are grappling with a new, more mysterious epidemic. And to fight it, they’re using a weapon scientists never thought they’d unleash.

Stony corals, though easily mistaken for rocks, are animals. Each colony is made up of tiny tentacled polyps crowded together to form a living skin that grows, mosslike, over an elaborate calcium-carbonate skeleton laid down by generations of clones. Like all animals, they get sick. Bleaching—an increasingly common affliction where heat-stressed colonies expel their colorful photosynthetic algae and turn white—could be akin to an autoimmune disease. Bacteria and viruses threaten them too.

In 2014, a scientist diving just off Miami noticed some mangy-looking corals with white bull’s-eyes where dead tissue had recently peeled away from the skeleton. It was the first sighting of a new condition called stony coral tissue loss disease (SCTLD). The ailment would tear through reefs in waters along Broward and Miami-Dade counties over the next two years, targeting more than 20 different species, including massive mounding varieties like brain and boulder coral that make up the foundation of the reef.

The contagion can knock out an 800-year-old colony the size of a car in a matter of weeks. Important habitats vanished and the wave-breaking power of the reef diminished, leaving the shoreline increasingly vulnerable to storms. As scientists scrambled to assess the damage, the mysterious malady started chewing its way into the Florida Keys, sometimes moving 10 miles in a month. By January 2019, it had infected areas as far south as Key West, encompassing much of the national marine sanctuary that protects more than 50 kinds of coral and hundreds of species of fish. This wasn’t just another illness, but a plague. And it had infiltrated one of the best-preserved stretches of coral reef left in the U.S.

With no diagnosis to guide them—most marine microbes don’t thrive in lab cultures, making the usual approach to identifying diseases basically useless—scientists still sought solutions. One hint of hope: Infected colonies kept in captivity recovered with the help of antibiotics.

But putting antibiotics into the ocean is problematic. The fish-farming industry uses them plenty but faces criticism for causing bacterial resistance in surrounding waters. The drugs also end up in marine food chains because wastewater plants have no way to remove the compounds from sewage and runoff. Now, with the blessing of the FDA, Neely and her colleagues are adding more chemicals to the load.

Neely and I take a boat from Ramrod Key, a lacy island in the Lower Keys where the tissue-loss disease showed up a few months earlier. It’s a short ride to the site, where we gear up and, palming our masks to our faces, roll backward into the water.

From 20 feet up, it’s hard to see anything amiss. Fish dart around swaying purple sea fans. Mounds of living coral rise from the sand, swirled with velvety brown ridges or freckled with green-blue buds. As we swim closer, Neely zeroes in on a maze coral as wide as a tire, its tawny skin marred by white splotches. She points out a puttylike line scrawled midway through one of the bare spots. This marks where she applied antibiotics two weeks earlier. At the time, it was the edge of the infection. Now, she writes: “Ineffective, disease passed” on her waterproof clipboard. She pantomimes wiping away a tear below her mask.

Three of the four colonies Neely treated are still sick. In some cases, SCTLD sneaked through the pharmaceutical barrier. In others, new white spots popped up elsewhere. Only on the last, a boulder coral roughly the size and shape of an overstuffed ottoman, has the treatment mostly succeeded.

This is what it’s supposed to do,” Neely writes, indicating the line that has held off bacterial siege. On one side, the deeply ridged surface is plush and healthy; the other is a bare, razor-edged skeleton. Antibiotics won’t undo the damage, but they can keep it from spreading through the entire colony. When we surface, Neely admits she’s surprised the meds haven’t worked better. She seems thoughtful but not despairing. “We’ve been studying coral diseases for 30 or 40 years,” she points out. “We’re still in the Dark Ages. Our treatments are like sticking leeches on and hoping for the best.”

The history of humans intervening in wildlife disease is brief and strange. Over the past three decades, we’ve tried to treat prairie dogs for plague and help chimps fight Ebola. We’re battling ongoing outbreaks of chlamydia in koalas and transmissible cancer in Tasmanian devils. Given the choice between losing species and medicating them, it seems, humans prefer playing doctor to undertaker.

In the ocean, however, we’re still out of our depth. “Where we are with coral disease is about where we were with human health in the 1800s,” says Andy Bruckner, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration researcher in charge of coordinating much of the work on SCTLD, echoing Neely’s assessment. “On land you can cull animals, you can put up some barrier to prevent an outbreak from spreading. We can’t do that in the water.”

We do know that we’ve made the emergence and spread of infections more likely. Corals already stressed by heat or pollution get sick more easily, and damage from human activity can give pathogens a foothold. And while most blights go into remission when temperatures drop, Bruckner says, SCTLD does not seem to take winter vacations. That’s left reefs without their usual span of recovery time. SCTLD’s unrelenting progress has felled as much as a third of Florida’s corals, making it perhaps the most destructive illness ever to hit the reef.

Global warming makes these sorts of fast-growing, far-reaching, and seemingly unstoppable plagues more likely. “In a lot of cases, warming is at least a double whammy for disease,” explains Drew Harvell, Cornell University marine ecologist and author of the book Ocean Outbreak. “It can stress the host and make it more susceptible, and warmer conditions allow a lot of microbes to grow faster.” Hotter water likely contributed to the sea star wasting disease that was first identified in Washington in 2013 and quickly spread from Alaska to Mexico, as well as other recent die-offs in lobsters, oysters, abalone, and sea grasses.

This isn’t just a marine problem. Some studies suggest that heat made amphibians more susceptible to a fungus that’s driving many of them to extinction. Just an extra degree or two may enable infectious bacteria and fungi in every sort of ecosystem to grow faster, with fewer periods of dormancy. “A planet that’s good for microbes is not going to be that safe for us,” Harvell says.

Even with stakes as high as these, the decision to apply antibiotics is still risky. Widespread use in agriculture and medicine has already led to a rise in drug-resistant bacteria. To minimize the danger, Neely and her colleagues mix amoxicillin, a common, broad-spectrum antiseptic that killed the disease in lab trials, into a paste that slowly releases the drug into the coral’s tissues. The concoction hardens when exposed to seawater, making its contents less likely to seep into the ocean. As Neely and I saw firsthand, however, these targeted doses might fall short. Despite the millions of dollars marshalled in ongoing efforts to fight this outbreak, there aren’t enough bodies in the water to treat every diseased coral on every ailing reef before SCTLD obliterates them. Instead, researchers and managers are focusing on a handful of key spots where endangered species could vanish. There is no guarantee they can defeat such an aggressive pathogen, but they’ll fend it off as long as possible.

In the meantime, scientists have begun to explore other, more-audacious schemes, including a massive operation to rescue the rarest corals from the reef before they disappear altogether.

“I don’t know if we can do anything with him,” says Cynthia Lewis, squinting into a basin of seawater, where a piece of pillar coral about the size and shape of a leg of lamb is looking very unhappy. Lewis is deputy director of the Keys Marine Laboratory and a specialist in this particular animal. Extremely rare and susceptible to disease, the species boasts fewer than 50 genetically unique individuals in Florida. In 2018, with SCTLD advancing on some of these last holdouts, Lewis and Neely led a campaign to collect fragments from all the remaining colonies, preserving as much of their genetic diversity as possible.

This one is pale and pinkish, flesh fraying off its skeleton. The infection is so advanced that Lewis suspects she might not be able to save it, but she will pass much of the day trying. As Neely says, surfacing from a dive where she spent half an hour chiseling this chunk off an ailing colony, “It’s a lot of work for so little tissue, but when you have 70 pandas, you do a lot for each panda.”

Lewis pauses her examination to glance at her phone. Her contractor is calling. When Irma hit Florida in 2017, the Category 4 hurricane destroyed Lewis’ house on Long Key. She is still rebuilding more than a year later.

The reef shapes any storm’s impact on the Keys. Irma churned up 30-foot swells on the open ocean, but inside the protective buffer of coral, the surge was only 10 feet high—still enough to do a lot of damage but stripped of much of its destructive force.

As the ecosystem degrades, it loses its ability to absorb that energy. Previous diseases have already nearly eliminated species like elkhorn coral, which once grew in dense shallow thickets throughout the Caribbean. Now SCTLD threatens to demolish several others, and not just in Florida: Something that looks a lot like it popped up in Jamaica in 2017 and Mexico in mid-2018, and divers spotted telltale lesions off the U.S. Virgin Islands and the Dominican Republic early in 2019. If the infection continues to spread, pillar coral could disappear from the Caribbean completely, along with a handful of other major wave-breaking species. Reefs will grow weaker with every storm, and it might be up to us to replenish their ranks.

A plump coral polyp clings to a ceramic tile; it’s barely bigger than a period, with light brown specks suspended through glassy flesh like dust in a sunbeam. “This is actually more high-tech than it looks,” Keri O’Neil jokes with me in the shade of a greenhouse outside Tampa. She’s tending to 60 of the tiny animals in a plastic dish pan.

O’Neil, senior coral scientist of the coral nursery at the Florida Aquarium, is a kind of no-boat Noah; she ushers animals onto land to give them safe harbor until the cataclysm passes. Her tanks are filled with rare specimens rescued as SCTLD took hold.

The dots she’s nurturing are the first pillar corals spawned and raised in captivity. At two months old, they are barely visible. Pillar coral grow only a couple of centimeters in a year, meaning each might take decades to get as big as Lewis’ leg-of-lamb patient. In the meantime, O’Neil and her staff clean the tiles they grow on with makeup brushes, and feed them concoctions of oyster eggs and supplements. And for the next generation, they’re building a spawning facility containing tanks fitted with blackout shades and full-spectrum lights to mimic the natural cycles of moon and sun.

“It’s really just about giving them everything they would get in the wild,” O’Neil says. She believes this is the necessary next step in saving Florida’s reefs. Researchers will observe previously undocumented spawning behaviors and learn how to reestablish species when the current outbreak finally passes, whether that takes two years or 10.

To hear O’Neil describe the time and effort required to breed, raise, care for, and eventually replant these captive corals in an unspecified and uncertain future is to understand the ambitious scope of ongoing efforts in the Keys. Antibiotics may have been a shocking step, but they’re just the beginning; the end goal is a wholesale renewal of an ecosystem that has been slowly degraded over decades, worn down by pollution, overfishing, and climate change.

“It’s a big mission,” O’Neil admits, and it depends on some of the smallest creatures on the reef. In the tanks beside us, pieces of pillar coral extend their tentacles in the sunlight. The golden-brown tendrils part and ripple in the current of the water-filtration system, growing and waiting for an ocean in which they can survive.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2019 Make It Last issue of Popular Science.

Written By Amelia Urry

0 notes

Text

Greeting the New Year in Earth’s Northernmost Settlement

On the flight from Oslo to Svalbard, the sun gave way to night as we crossed the Arctic Circle; for one magical moment, the plane’s wing bisected light and dark perfectly. This would be the last natural light I would see for a week. For half the year, Svalbard, the northernmost inhabited place in the world, is lit by the midnight sun. The other half of the year, the Norwegian archipelago is plunged into the purple darkness of polar night.

Few people have heard of Svalbard and even fewer have seen it. The isolated group of islands is an old mining settlement turned glacial adventuring outpost located 1,200 miles north of mainland Norway, one of the closest landmasses to the North Pole, along with Greenland and Nunavut. The approximately 2,200 inhabitants dotting the desolate tundra are itinerant, a mix of climate scientists, miners and globe-trotting explorers mostly from Russia, Scandinavia and Canada. There are more polar bears than people.

Historically, this archipelago was the isolated purview of turn-of-the-century airship explorers obsessed with finding the Northwest Passage; more recently Svalbard served as the fantastical setting for Phillip Pullman’s “His Dark Materials” trilogy. Today, it is poised to be the next extreme vacation destination for tourists obsessed with climate change, wilderness and chasing the Northern Lights.

Svalbard is an Arctic desert. Its permafrost makes it the ideal home for the Global Seed Vault, an underground repository for the world’s most vital crops (and likely Svalbard’s most famous tourist attraction, though no tourists are allowed inside). But this permafrost also means nothing can take root, giving the place an eerily lunar landscape, with no trees and few animals.

The extreme isolation and hardness of the landscape is what drew me here, too. I took the trip with my partner Noah. Both of our marriages had recently ended, and in our 40s, we were suddenly rootless, dislocated in a way neither of us had expected. It was as though we’d sat on the shoreline, watching a glacier crumble into the ocean. We’d found each other, but our relationship was still new and untested. Perhaps we’d been drawn to the Arctic to see if anything permanent in the world still existed.

And so, at the end of December, after spending a few days in Oslo exploring Grünerløkka’s record shops and the Viking Museum’s ships, we took a direct morning flight to Svalbard. I imagined stepping off the plane into a sea of phosphorescent green aurora, but when we arrived, the sky was cloudy. Noah had seen the Northern lights many times, mostly in Iceland, but this would be my first experience. I loved the idea of the sun setting off a solar flare 92 million miles away, and having it appear here in all its eerie ectoplasmic beauty, like some ghostly atomic postcard.

A set of stairs was rolled up to the plane’s exit door and along with everyone else we wrapped our bodies in our serious coats and hats and mittens before stepping out into the icy air. At the bottom of the slippery staircase, a woman in a reflective flightsuit directed us toward the airport with hand-held lantern flares. A silver foil tiara spelled out Happy New Year on top of her white-blond bun. It was 10 in the morning on New Year’s Eve and pitch black.

Longyearbyen, Svalbard’s main settlement, is essentially two roads in a giant T. This once untouchable frontier has evolved into a study in contrasts, a balance of scarcity and opulence, some of the world’s roughest terrain inexplicably mixed with luxury. For a long time, Svalbard was reserved for the tourist elite because of the difficulty and cost of travel, not to mention the expense of outfitting yourself with the right boots, parka, layers and more to withstand the cold. Visitors tend to be either young adventurers working their way across the world or high-end travelers checking off their bucket lists, and most of the lodging and restaurant options fall into either the budget or splurge category. There is little middle ground.

We booked a room at Funken Lodge, a modern hotel with clean lines and Scandinavian efficiency, where we were welcomed with drinks by the fireplace at the hotel bar (rooms are currently about $150 to $180 a night, breakfast included). We’d made New Year’s Eve dinner reservations at Huset, the highest-end of the handful of restaurants in town, and that evening took a taxi to the unassuming building tucked dramatically at the foot of a towering glacier, where the row of snowmobiles parked out front made it look more ski-lodge than fine Nordic dining. The building has, at various times served as the island’s post office, church, school and airport terminal, as well as a miner’s boardinghouse. Today it is also the understated home to one of the largest wine cellars in Scandinavia with 15,000 bottles and a Two Wine Glass distinction from Wine Spectator magazine.

Huset’s staid interior was in stark contrast to the decadence of the plates. Our five-course meal (1,200 Norwegian krone each, or about $131 per person) started with an appetizer of woody chanterelles that had been foraged locally. Glistening cuts of Isfjord cod and roe were nestled atop beds of lichen and ptarmigan feathers. The main course showcased local reindeer two ways (tartare and made into hearty sausage), accompanied by strands of salty kelp harvested from the island’s shoreline and microgreens provided by the island’s sole greenhouse, a pink geodesic dome visible from the main road. The structure’s neon blink was the only colored light on the island, like a pair of neon Wayfarers in a sea of mirrored Aviators.

The waiter told us that the restaurant turned into a local’s nightclub after dinner, so we stayed in our corner, sipping from our many half-glasses of wine as the demure dining room changed over to flashing lights and techno. A few minutes before midnight, Noah and I pulled our coats and boots on and half-stumbled, half-skated to the edge of the parking lot between the restaurant and the high wall of the glacier. Some of the kitchen staff lit off fireworks, holding the cardboard containers as the flares launched into the air, refracting off the towering wall of glittering ice until everything was bathed in flame. They were not Northern Lights, but these man-made sparkles of color had their own kind of otherworldly beauty.

We woke to the first day of the new year and nursed our hangovers, grateful for the dark. Months earlier, we’d booked a Northern Light Safari with Dog Sled (2,780 krone for two). In the safe glow of a computer screen at home, this had sounded whimsical and romantic. Now, it was mildly terrifying.

Our guide picked us up in a cube van from the hotel, and as we drove farther out of town the streetlamps disappeared, replaced by polar bear warning signs. From a distance, Green Dog Svalbard looked more like a maximum-security prison than a dog-sledding outfit, but the guide explained the chain-link fence and floodlights were needed to keep the dogs safe from polar bears. This was comforting, until I realized the point of our trip was to take the dogs from camp out onto the glacier.

Before sledding, we hung up our fancy parkas and shouldered into bulky jumpsuits that smelled like dog and hooked oversized sheepskin mitts on a string around our necks. This reminded me sweetly of a child’s mittens, until the guide warned us that unguarded our hands would get frostbitten in less than five minutes.

From the hut we followed the guide into the open-air kennel. Names were painted onto each of the dozens of doghouses, and dogs whimpered and leapt with excitement, pulling on their chains staked to the frozen ground. Each sledge held two people and the dogs were organized into teams of six. The guide shouted some general directions over the deafening howling; I tried to listen while wrestling our dogs into formation, sweating profusely under my layers, goggles completely fogged. “Here is your anchor!” He held up a heavy ball of spiked metal attached to the sled. “Make sure you secure your anchor, or it will flop around dangerously and claw you in the leg!”

Noah and I got our bearings on the sledge, essentially a roughhewn Flexible Flyer with a high back, which I sat against and he stood behind. With no fanfare, the guide’s whistle pierced the night, and our six huskies were running, the lights and safety and noise of the kennel disappearing behind us.

Even with a hood, balaclava and goggles, the wind froze my breath in my chest. We were racing through the Bolterdalen Valley, but we could have been on the moon, and I felt like an astronaut floating in space. Our path was lit only by my headlamp, though the dogs clearly knew where to go, and although Noah held reins in his hands, we were just passengers. A few minutes in, we were so completely alone on the ridge of the glacier, so completely in the middle of nowhere, that I began to feel panicky. I concentrated on the dogs’ rhythmic breathing echoing into the icy silence and tried to calm down.

By the time we returned to camp more than an hour later, I could not feel my jaw or feet. Noah and I worked at unhooking our dogs and returning them to their doghouses, and suddenly I was a sweaty mess again, jaw and feet tingling back to life.

In the van on the way back to the hotel, Noah cracked a handwarmer to life and slipped it between our palms. “Did you see the Northern lights?” he asked, flushed. Apparently they’d appeared in the middle of the trip, but I’d been so focused on the dogs, and keeping my balance on the sledge, I’d completely missed them.

Going inside the glacier

The next few days blended into one long night. We ate elaborate meals of Arctic char and gravlax at our hotel restaurant and handmade chocolates from Fruene, the world’s northernmost chocolate shop. We slept late and took long walks through town, wary of bears. Everywhere we went, our snow pants made a shush-shush sound.

One night, we layered up for an evening glacier hike. Our guide Martin drove us to a cluster of miner’s cabins at the edge of town where he handed out headlamps and springy-teethed crampons for the bottoms of our boots.

Martin was tall and trim and he secured his rifle to his back with an embroidered strap of red and green and gold. He cautioned us to stay together — our group of six could only go as fast as the slowest hiker to stay safe from polar bears since he was the only one with a gun. His husky, Tequila, joined us on the two-hours of precarious ice trekking, until we arrived at an unassuming hole the size of a sewer grate on the top of the glacier. We took turns sliding down a tunnel into the dark.

The ice came alive under our headlamps, and the glossy gray ribcages of stalagmites and stalactites made me feel like Jonah inside his whale. The swirls of sediment made wavy marbled ribbons in the wall, and the clicking of our crampons echoed through the tunnels. It felt like walking on teeth and bone and glass.

Summer snowmelt created these caverns. We’d been hiking above a network of underground tunnels. Martin passed around cookies and cups of syrupy blackcurrant juice, leaving purple stains on a makeshift ice bar, and after an hour of wandering inside the tunnels, we crawled back out to Tequila and into a snowstorm. We trekked downhill in an ebullient line, giddy despite the icy crevices and drop-offs that lurked beyond the pale light of our headlamps under the cloudy night sky. There were no Northern Lights, but as we hiked back, a small triangle of light appeared between the glaciers. Town.

I spied the strange pink glow of the geodesic dome, the island’s unlikely greenhouse. As my crampons gripped the ice, I thought about the beds of tender green leaves that I imagined populated it. Why try to grow something in an Arctic desert, a place that by nature is uninhabitable to anything with roots? No one can be born in Svalbard — pregnant women are required to leave the island weeks before their due date — and you cannot be buried there because of the permafrost. And yet, this neon dome pulsed, a pink heart on an otherwise blank slate, offering the promise of new growth where none was expected, roots where otherwise there were none.

Hot dogs and the aurora

Noah’s birthday arrived on the final day of our trip, and I packed our hotel towels and slippers into a bag and told him I’d arranged for a surprise. I’d reserved space on an excursion called “Sauna Meal & Aurora Borealis,” and soon, after driving in a cube van to an isolated campsite on the tundra, we were helping our guide Misha stretch a canvas cover across the crisscrossed spines of a tent frame over a portable sauna. Misha made hot dogs over an open fire in a steel caldron on the ice while we waited for the sauna to heat up. This was the least glamorous meal we ate in Svalbard, and yet it managed to still feel extraordinary as we sat together around the fire, drinking tea and eating hot dogs in the Arctic.

After the barbecue, we stripped off layer after thermal layer, scuttling the 20-foot distance between tents in just a towel and slippers. Once the sauna tent’s flap was securely zipped, we sat in lawn chairs on the ice in the small dark space, listening to the hiss of the water on the rocks. We sweated, luxuriating in the heat, pawing snowballs from the floor and running them against our bare skin. This was the strangest but perhaps most fitting way for our time in the Arctic to end, I thought, huddled together with full bellies on the tundra, Misha patrolling the perimeter for polar bears.

After some time, I wiped the fog from the small slice of clear plastic in the side of the tent and realized the stars were ablaze in the sky, and as I scanned the edge of the glacier I saw something forming: like a cloud, but more ghostly. I grabbed Noah’s arm and we ran outside.

We stood, staring, in slippers and towels on the tundra, as the milky wash of the aurora sparkled across the sky. The lights weren’t green; they weren’t any color, really, but I’d never seen anything like it. My sweat felt like all the stars in the sky were wrapped around my body in a blanket, little spears of heat and ice, and when I turned to Noah his skin was bathed in silver, as if his body was part of the aurora itself.

52 PLACES AND MUCH, MUCH MORE Follow our 52 Places traveler, Sebastian Modak, on Instagram as he travels the world, and discover more Travel coverage by following us on Twitter and Facebook. And sign up for our Travel Dispatch newsletter: Each week you’ll receive tips on traveling smarter, stories on hot destinations and access to photos from all over the world.

Sahred From Source link Travel

from WordPress http://bit.ly/2QvqGsK via IFTTT

0 notes

Photo

Day 16—September 15

The bed at this place was incredible. It’s GIANT. I can be sprawled out and taylor can be too and we’re barely touching. We got up around 9:30 and came out to breakfast on the living room table. A beautiful set up with cereal, fruit, yogurt, toast, and espresso all served in her husbands beautiful glass art. (Did I mention that she’s an artist too? She does intricate mosaics and they are absolutely stunning). And taylor and I couldn’t get over how sweet our host was to set all this up, it was fantastic. She just asked that we don’t post anything about the breakfast on Airbnb because apparently in Italy you can rent out a room but you can’t provide any services so she could get fined and shut down. We ate and Kimmie joined us and 2 cups of espresso later I was beyond pumped to start the day. Kinda cool to say my first time trying espresso was in Venice :p We decided to get lost in Venice which, we learned, is not only simple to do but impossible NOT to do. We walked around for 9 and a half hours and, no exaggeration, only sat down or stopped really for 45 minutes of that. The day is a blur of beautiful streets and stairs crossing canals. The streets had no rhyme to them and some would end abruptly or get incredibly narrow for a short while. Sometimes it felt as though we were lost in a labyrinth only to emerge onto a Main Street filed with tourists. The only down side was that there were so many people in parts that we felt a little like cattle being herded and the locals are very impatient, pushing themselves through the crowded streets. There were a few things I definitely wanted to see so we sporadically used google maps to head in the right direction. Taylor said she had thought if we wandered enough we would bump into everything but that was so far from the case. Small as it may be, getting around can turn you in circles so fast and we got lost a few times even with the assistance of google maps. Here is a list of highlights from today:

- We got pizza and it was quite possibly my favorite ever. One bite into that crust and I knew that American pizza will never taste the same. Just being aware of the fact that such a level of deliciousness is possible, I’m spoiled forever. It’s the crust. The dough they use is magnifico! - Trying to find the grand canal we basically gave up using a map and I saw a bridge that I was drawn to. We went over the bridge and found the view I’d been looking for. The grand canal was indeed, pretty grand. There were a few women with their canvases set up painting the view, their talent so obvious. - We passed a woman playing an instrument that I’d never seen. It looked almost like a kind of harp laying down but she used a combination of finger picking and rubber hammer instruments to play if. She was playing a song that I love and we stopped and watched her in awe for a few minutes before giving her a tip. - I fell in love with a purse. It was small, leather, deep teal, said “made in Italy” and was only €20. (I didn’t get it because I thought we’d end up passing that store again, which we didn’t, but I’m still glad I didn’t get it. The next day our host informed us that a lot of Chinese people come and have shops in Venice where they sell knock off versions of things that are made in china but are stamped with “made it Italy” so people buy them. They have giant factories I guess just 30 minutes away and none of it is made here. Good to know!) - There were a lot of gondolas and without even paying for it, we got to hear their music a few times as they passed under a remote bridge down a random street. One time there was this woman playing the accordion and i just fell in love with the song she played. She looked like Lorena McKennit and had the same whimsical music trance aura about her. - Walking around they have men outside restaurants trying to recruit people to come eat there. One young man after greeting us with a “buena cera” asked us to come inside. We politely declined and he yelled to us “maybe at least come back and talk to me?” With a charming smile haha Italian men really are flirts - We were on a mission to find st marks (Marco) basilicas and wow did that prove to be a struggle haha never thought it was possible to take so long to walk 0.2 miles! But then all the sudden we turned a corner and bam we were there! This wide open space, the plazza, and the basilica front and center! Such a gigantic and elaborately decorated building it was difficult to grasp. There were pigeons everywhere and the children chasing them warmed my heart. I wish I was about 20 years younger–an age when that still is socially acceptable. Still I was tempted. - The pigeons deserve their own bullet point. I felt like I hadn’t looked at the basilica enough so we went back but the pigeons stole the show. People were feeding them and they’d land all over them and eat out of their hands. I instantly wanted to do the same but we didn’t have any food. Taylor said to just hold my hand out and trick them. I didn’t think this would work but I did it anyway and it worked!!!! I made a pigeon friend and I was so happy. I even got taylor to do it too :p - Learning our lesson from Ljubljana we bought umbrellas before the rain and they came in handy as we could still roam the streets while other sought the dryness under awnings. We also wore samples which I’m sure looked bizarre with the umbrella- “they were prepare enough to bring an umbrella but not closed shoes??”–but it ended up being perfect. Besides, our other shoes are still soaked from the rain we got caught in all day 3 days ago. - We stumbled on this art exhibit that had a few displays outside, one of which was a life size woman in a swim suit and cap that looked like she was sitting on the edge of a pool. It looked so realistic that I half expected it to move, and the close I go the more real she looked. The recent rain made it look even more realistic, and the wisps of hair blowing in the wind were tripping me out. I’m in awe of that talent. How does someone do that?! As I got close to take a look taylor went “AH!” Like trying to scare me and everyone around laughed haha I guess pranking is a universal language too! - This one shop looked like a promising chocolate shop so side stepped into it and pulled taylor in with me. We were enthusiastically greeted and promptly given about 4 different samples of candy. One was dark chocolate covered orange peel, then dark chocolate covered almond, a hard candy with melon liquor, and the absolute best lemon cookie I've had in my life. It was like god himself made that cookie. It had this tiny cream center and I had to really talk myself out of buying a box. But the €8.50 price tag was enough of a deterrent. - Not sure what it is about this town but they had soooo many mascaraed shops with hand painted paper mache masks, wall hangings, ornaments, you name it. They were elaborate and intricate and expensive but we had fun gawking over them! - Taylor was dragging big time when we were heading back, asking me how I was still going so strong. We decided we needed to stop for food and looked at about 10 different places before deciding on one. We chose it for its prices and learned we shouldn’t do that anymore. The ambiance was, well, pretty bad and the service was subpar. Compared to the place we had passed this one wasn’t nearly as enjoyable to sit in. The food was stellar though, oh wow. The best pesto I’ve ever had in my life. It tasted/smelled like they went out back and had picked fresh pesto right before cooking it–wouldn’t at all surprise me to hear this was the case. But taylor and I vowed not to cheap out anymore because in the grand scheme it’s only a few euro difference and the ambiance is pretty memorable.

Around 9:00 we got back on the water taxi and headed back to Murano and it was nice to have a few hours to decompress. All that walking caught up to us and just laying in bed was incredible. We ate leftover pizza and went to bed. Eating carbs all day, I think we’re doing this Italy thing right :p

0 notes

Text

Exploding bolts let us travel through space

New Post has been published on https://nexcraft.co/exploding-bolts-let-us-travel-through-space/

Exploding bolts let us travel through space

From the next room, through a thick granite wall, comes a chug-a-chug-a-chug-a, like an old steam train closing in. Rounding the corner, I see the source of the racket: a table, shaking. The long, metal slab jerks quickly back and forth. On it, in two neat rows, are a half-dozen rectangular prisms packed with sensors measuring pressure and motion. Each one holds a titanium-alloy bolt the size of a grown man’s forearm and weighing about 10 pounds. As the elaborate assemblage might hint, these bolts are special.

Eventually, this remarkable hardware will go to space. The bolts, or ones like them, will hold together sections of the Orion spacecraft, a new vehicle that, sometime in the next decade, will carry humans out of low-Earth orbit for the first time since 1972—initially to the moon and later on trips to Mars. But before that, the fasteners must survive a mock version of their journey. Only worse.

The shaking they’re enduring is merely the beginning, intended to simulate the violence of a launch. The parts also brave hammering, baking, and freezing—24 tests in total. All this before any metal even reaches the launchpad. The abuse ensures not only that the bolts will hold together massive space-faring machines, but that, at the exact right moment, they’ll break neatly apart. More specifically, they’ll explode, strategically jettisoning segments of Orion’s rocketry as they do.

The design, manufacture, and most of the testing of this combustible hardware happens in an old stone factory in Eastern Connecticut, where engineers have crammed various items full of pyrotechnic material for well over a century. The 200-acre campus of 19th-century brownstone, granite, and brick—a look that’s part factory town, part college—is the home of the Ensign-Bickford Aerospace & Defense Company (or EBAD, because what’s a defense contractor without a vaguely sinister acronym?). EBAD is one of more than 2,000 companies making Orion’s nuts and bolts (and ceramics, fabrics, and springs) for Lockheed Martin, NASA’s main contractor on the project.

EBAD’s components are a bit player in this space epic, but the firm’s mission-critical role gives it an outsize gravitational pull. Of the 5.5 million pounds of rocketry (collectively known as NASA’s Space Launch System) and other equipment that will hurtle Orion out of the atmosphere, only 20,500—less than 0.38 percent—will come back to Earth. “The last thing we want to do is take all the stuff at launch to the moon and back,” explains Carolyn Overmyer, Lockheed’s deputy manager for the Orion crew capsule (where the astronauts ride). “We don’t need the blast system at the moon. So where does it go? It separates. It’s a ‘sep event.’” In plain English: Stuff falls off.

The exploding bolts are the catalyst in that process, “central to our mission,” Overmyer says.

There are eight separations in a complete Orion journey to the moon and back. One of the first occurs three minutes after launch: The bolts split alongside explosive-powder-laced zippering fissures called frangible joints to discard the loads that get Orion off the ground. Three nearly-two-story panels, called fairings, that protected the craft from the heat of liftoff simply drop. “A 15-foot-tall coffee can goes boom! and just flies away,” Overmyer says, recalling the first time she watched the panels split from the craft during a test flight. “I know it sounds silly to say it, but I found it very, very beautiful.”

As the mission progresses, more systems become irrelevant and break off. The final thing to go is the service module, a trash-can-shaped pod that houses all the liquids and gases for the mission; it holds on to the Orion capsule throughout the 1.3-million-mile journey on the strength of four fasteners made for this exact task. When the crew-carrying vessel begins its dive back to Earth, the fasteners split and release the pod, which then burns up.

Preparing these bolts for their pivotal moment—their perfect failure—presents as a kind of Zen koan. How to fully test a thing that works exactly once? How do you design something that, in order to do its job, must fail?

Part of the answer is revealed in the threaded fasteners, called release and retention bolts, shaking and rattling on the table. Of all the variations of hardware EBAD builds for Orion, these must suffer the most intense torture, both here on Earth and in space. “We beat the hell out of ’em,” says Steve Thurston, EBAD’s manager of test services, as he watches the heroic fixtures rumble angrily against the table’s motion. Thurston turns and walks toward a quieter spot and says softly, almost solemnly: “It’s really not fair to the parts. But that’s the point—to find their limits, to push the envelope.”

Outside, a morning rain gives way to the bright-green beginning of a fall day. A river, which once powered EBAD’s works, winds through the campus; a family of otters has taken up residence. It’s hard to square the setting with what goes on behind the aged stone walls: space-age bolts getting stretched (and mashed and bashed and rattled) to their limits.

Simsbury, Connecticut, has been home to EBAD since well before the Civil War. Back then, there were iron and copper mines and granite quarries throughout the region, which meant a lot of digging and an awful lot of booms. The methods were crude: Dig a hole, fill it with gunpowder, plug it except for a small space to run a fuse (usually string or cloth), light, run. Men died by the hundreds, often because things blew when they weren’t supposed to—mostly too soon.

In 1831, these techniques began to change—become more refined, predictable, safe. In the city of Cornwall in Old England, where there was even more mining than in New England, an inventor named William Bickford patented the first safety fuse. Bickford packed gunpowder into a hollow jute rope, which then fizzled at a predictable clip of roughly 30 seconds per foot. In 1839, he partnered with a Connecticut mining company to manufacture and sell his burners stateside. Ralph Hart Ensign joined on in 1870. His heirs would later expand the firm’s explosives business beyond fuses, developing products such as a banker’s bag that smoked when a crook tampered with it.