#but i feel like moon has a larger gameplay purpose than a story purpose... it was supposed to enforce a time limit

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

I thought the books said that Sun and Moon used to be theatre animatronics repurposed for the daycare?

to my knowledge the story is that they used to work in the theater, with sun serving as the main act who would turn evil when the lights turned off (which is where moon came from). when they were moved into the daycare they were reprogrammed to remove all their performance functions, but that darkness trigger couldn't be removed. and that, combined with the daycare area being prone to blackouts, caused moon to be a thing?

i don't know if their past as a theater animatronic is actually elaborated on beyond that though.. we actually don't even know if they were supposed to be important to the story at all

#ask#im not an expert on what happens in the books.. you can read more about them on the wiki if you'd like#but i feel like moon has a larger gameplay purpose than a story purpose... it was supposed to enforce a time limit#since iirc during development time was actually supposed to be constantly running.. rather than time changes being tied to other triggers#but sb had a lot of upheaval during the development process so now they've gotta make sense with what they've got#and that includes any possible story relevance for the dca

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

I Regret Buying Pokémon Shield

I told myself I wouldn’t do it. I’ve seen time and again the lack of innovation from main-series Pokémon games, and I insisted nothing would convince me to buy this latest atrocity. Yet here I am, reviewing the game I said I’d never purchase. I should have listened to myself. I KNEW BETTER! Strap in, ‘cause this one’s pretty long.

Pokémon has been around for a long time—like, a long, long time—and I’ve been around for every single new main-series game that’s been released since the franchise’s first arrival in North America back in 1996 with Red/Blue. I was not yet 10 years old, and I still remember the childlike excitement of finding rare, never-before seen creatures, the stress of trying to catch a wily Abra or elusive Pinsir, and the challenging first encounter with the Elite Four and the Champion, a 5-man gauntlet of trainers with powerful Pokémon rarely (if ever) seen in the game prior to that moment. It was exhilarating in a way that keeps me coming back for more, hoping to rekindle those same flames of wonder.

While the main gist of the games hasn’t changed much over the years, one of my favorite parts of playing a new Pokémon game is seeing the improvements each game brings to the series. Many of the initial sequels made huge leaps in progress: Gold/Silver introduced a plethora of new mechanics like held items and breeding; Ruby/Sapphire introduced passive abilities and was the first to include multi-battles in the form of double-battles; Diamond/Pearl was the first generation capable of trading and battling online and brought us the revolutionary physical/special split so elements were no longer locked into one or the other. These changes all had significant impacts on how players approached battles, formed their teams, and used each Pokémon.

Those changes, combined with the addition of new Pokémon to catch, regions to explore, and enemies to fight, were enough to keep me interested. But I know I wasn’t alone in imagining all the possibilities of taking the franchise off the handheld platforms and moving the main series games over to a more powerful home console. In the meantime, each generation that followed Gen IV highlighted a new, troubling pattern that became more and more prevalent with each addition to the series.

1. Gen V: Lack of meaningful gameplay innovation

By Generation V with Black/White, not only was Game Freak quickly running out of colors, they were quite obviously running out of ideas for significant gameplay innovation. The bulk of Black/White’s biggest changes were improvements on or adaptations to existing staples to the franchise: many new Pokémon, moves, and abilities were added, and the DS platform allowed for greater graphical quality where Pokémon could move around a bit more on-screen during battles, the camera wasn’t as rigid as it had to be in previous games due to machine limitations; perhaps most importantly, they FINALLY decided to make TMs infinite. Thank goodness. While the updates were nice, they were nowhere near as impactful on the game as previous generations’ changes were and served more as needed quality of life adjustments.

I would also argue Gen V also had the least inspired Pokémon designs (like Vanillux and Klinklang) with the worst starter choices of any Pokémon game, but that’s a discussion for another time. Excadrill and Volcarona were pretty cool, though.

2. Gen VI: Gimmicks as the main draw

Pokémon X/Y (See? They ran out of colors) continued this new downward trend in innovation. Mega-evolution—while admittedly pretty cool—wasn’t enough to carry the new generation into an era of meaningful improvement because it was equivalent to adding new Pokémon rather than developing innovative gameplay, ushering in a new era of gimmicks in lieu of substantial updates.

Though the gameplay innovation for X/Y was minimal, the graphic updates were substantial: Pokémon X/Y was the first generation to introduce the main series to a fully 3-dimensional world populated by 3D characters. However, since X/Y was on the 3DS, it was a ripe target for the 3D gimmick seen in almost all games on the console, which I personally used for all of 5 minutes before feeling nauseous and never using the function again.

Despite the fresh look of the new 3D models, the battle animations were, to be frank, incredibly disappointing. Pokémon still barely moved and never physically interacted with opponents, nor did they use moves in uniquely appropriate ways. To my point, for years now there’s been a meme about Blastoise opting to shoot water out of his face rather than his cannons. I was sad to see that they didn’t take the time to give each Pokémon’s animations a little more love. But I figured, in time, when or if the franchise ever moved to a more powerful machine, they would be better equipped to make it happen, right? I also convinced myself that the lack of refined animations were kind of charming, harkening back to the games’ original (terrible) animations.

3. Gen VII: Focus on Minigames

The main innovation (gimmick) that came with Generation VII, Sun/Moon, was the lack of HMs in lieu of riding certain Pokémon. Sun/Moon also added Ultra Beasts (essentially just new Pokémon) and Z-moves (just new moves) which only added to the number of gimmicks present in the games. These changes, which provide some mild adaptations to gameplay from previous generations, don’t fundamentally change the way players go through each game, the way that updates in the earlier generations did. I personally played through the entirety of Sun/Moon without using a single Z-move or seeing a single Ultra Beast outside the one you’re required to fight to progress the main story. Ultimately, these changes were not a significant enough experience to warrant an entirely new game that is otherwise full of more of the same stuff with slightly different creatures who have slightly different stats and occupy a slightly different world.

Though Sun/Moon was comfortably embracing the franchise’s affinity for gimmicks, it brought to the forefront yet another troubling trend: mini games. Between photography, the Festival Plaza, and Poké Pelago, the focus on and attention to detail toward mini games had grown considerably over the years. Pokémon games have always had minigames and other time-sinks—which is great! Don’t get me wrong, I appreciate having more to do than trudge through the main story. But it is apparent that, with each new generation, more time seems dedicated to development of these extras. Pokémon Contests, Secret Bases, Super Training, feeding/grooming; a lot of their larger innovations after Gen IV were centered on non-essential parts of the game, which results in diminished game and story quality overall.

Admittedly, Sun/Moon did have some of the best exploration moments of any of the Pokémon games, which I did very much appreciate. More on that later as it relates to Sword/Shield…

4. Generation VIII: You Can’t Be Serious

When Game Freak finally announced they were launching Generation VIII, Sword and Shield, on the Switch rather than a dedicated handheld console, I was beside myself with excitement.

And then I saw gameplay footage like this, and my heart sank.

What is the purpose of launching the game on a stronger console if they are going to continue copy/pasting their sprites and their animations? If they aren’t going to provide the Pokémon any unique flair or create more appropriate animations? It was disappointing enough seeing the same animations/models from X/Y for Sun/Moon, but that was sort of expected since the games were on the same console. But now that the game has moved to the Switch, this is unacceptable.

When I learned that they were significantly cutting the number of Pokémon available in the game, I thought for certain that would translate to more time dedicated to the ones that made the cut, to focus on adding animations and character to the critters to make them feel like real parts of the world, rather than avatars of a child’s imagination, unable to fully process how the world functions. Alas, what was I thinking?

I thought the Dynamax gimmick would be one of my biggest gripes because it’s so pointless, or maybe the Wild Area’s severe lack of organic belonging (all Pokémon are just wandering aimlessly, weather can change drastically after crossing an invisible line, trees look like they were cut and pasted out of Mario 64, you can’t even catch Pokémon if they’re too high a level) but honestly the most disappointing part of the game for me was the pitiful routes between towns/gyms. Previous installments of the game included routes full of trainers and puzzles you needed to defeat or solve before you could progress—in Sword/Shield, the only thing that ever prevents you from progressing are some Team Yell grunts barricading paths the game doesn’t want you to take yet, for literally no reason. It completely removes player autonomy and a sense of accomplishment earned through overcoming challenges—now instead of learning that you need to find an item that allows you to cut through certain trees to gain access to new areas, you simply follow the story beats and then, upon returning, the path will be open. It’s inorganic, it’s clunky, and it’s extremely lazy.

Speaking of lazy, the story itself was another massive disappointment for me. Pokémon games are not particularly known for having deep stories, but Sword/Shield takes it to a new low. Every NPC simply pushes you to battle in gyms, and every interesting story beat that occurs happens just outside the player-character’s reach. Any time something interesting happens, you are shooed away and told to let the grown-ups handle it while you just get your gym badges. There COULD have been some interesting story moments where your character gets more involved with helping fix the havoc occurring around the Galar Region, but instead we as the player are simply TOLD what happened, why it happened, and who fixed it (usually the champion, Leon).

I honestly think having the game focus on the story of Sonia, Bede, Marnie, or even Hop (was not a fan of this kid) would have been a much more interesting game, because those characters actually had some depth to them, some bigger reason for taking on the gym challenges than simply “I want to be the very best.” Albeit those stories would have required a tremendous amount of work to add depth and details, the potential for a better story is in those characters. There is just no story at all to the main character, who is ushered from gym to gym because…because? Because that’s what kids do? I’m not even really sure what the motivation is.

There are SO MANY exciting, interesting, innovative ways Game Freak could drive Pokémon into a new and exciting direction while still maintaining its charm and building on existing mechanics, but they instead choose to demonstrate their lack of interest in significant graphical and gameplay innovation. I imagine this is largely because the masses will eat up just about any Pokémon product produced so long as there’s a new bunny to catch, and Pikachu is still involved. I’m disappointed, and I wish the Galar region could meet the expectations of my 10-year old mind’s imagination.

When abilities were added, we suddenly had to consider whether our Earthquake could even hit the enemy Weezing and adapt to the tremendous changes the passive skills added, reconsidering how we faced each battle. When the physical/special split occurred, entirely new opportunities opened up and certain Pokémon who were banished to obscurity due to their poor typing and stat distribution, like Weavile, were suddenly viable. Some even became incredibly powerful, like Gyarados, who had been hit pretty hard by the Special attack/defense split. There were also already-powerful Pokémon (Gengar, Dragon-types) who became even more so through access to STAB moves that benefited off their strongest stats.

I want new games to include updates that feel as impactful as these changes. If you’re interested in how Game Freak can improve on the main gameplay, I have some fun ideas that will be fleshed out in another article: How to Breathe New Life into the Pokémon Franchise. That article will be dedicated to explaining what those changes are, why I want them, and how they can improve future games.

#pokemon#pokemon shield#pokemon sword/shield#game review#review#hilltop sunset#streamer#gamefreak#gen viii#gen 8

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pistols at Dawn: A Look at Doom and Marathon

In the mid-1990s, the first-person shooter genre was born with Doom. It wasn't the first game of its type. Games like Wolfenstein 3D and Blake Stone: Aliens of Gold preceded it. Catacomb 3D came before either of those. And you can trace the lineage further back if you like. But it was Doom that saw the kind of runaway success most development studios live and die without ever attaining. That success spawned imitators. It was the imitators and their imitations – some of them using the very same engine – that made it a genre. It's how genres are born.

It was interesting to watch that happen in real time.

But that's the PC side of history.

If you were a Macintosh user, you were probably sick to death of your PC-owning friends crowing about Doom, all the more because it wasn't available for your system of choice. Doom would eventually make its way Mac-ward... after its own sequel was eventually released for the system first. Absurd as this sounds, it didn’t really matter too much. Story, and the importance of continuity between games, wasn't exactly a big concern in Doom.

But Mac users had little reason to despair. Because although Doom was and is rightly remembered as a classic, Mac users were privy to a game nearly as good – probably even equal, maybe even better, depending on who you talk to.

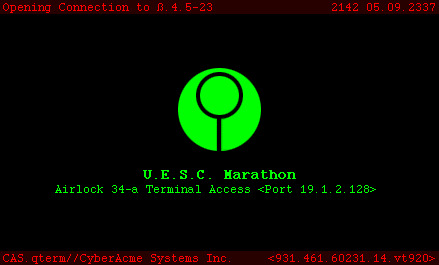

That game was Marathon.

More below the cut.

It's hard trying to justify comparisons between Doom and Marathon, because despite their similarities, they aren't really in the same league. It's hard to compare any game that became the jumping-off point for a whole genre to its contemporaries. But as much as I lionize Doom, and as much as everyone else does the same, it's perhaps helpful to think that this is done with the benefit of hindsight. Today, in 2018, we've had nearly two-and-a-half decades of Doom being available for almost every single thing that could conceivably run it.

Remembering Doom in its time, it would have been hard to predict that it would go on to achieve quite the level of adulation it's garnered over the years. It's not that Doom doesn't deserve it. It's more that any game attaining this level of success both in its time and in the long term is basically impossible to predict. Doom was much talked about, it was wildly popular, you heard rumors of whole IT departments losing days of productivity to it in network games, but... Well, it was just one game. Later two. It was perfectly valid to suppose, in the mid-90s, that some developer would surely supplant it with something even better. That's just the way things worked. It's just that Doom was well-made enough, well-balanced enough, that "something even better" didn't come around for a long time.

Still, the Macintosh is not where I would have expected to look for real competition for Doom.

The Mac wasn't actually a barren wasteland, game-wise. It's just easy to remember it that way, especially if, like me, you grew up playing PC games. Most of the games we think of as being influential in the realm of computer gaming tended not to come from that direction. Mac users made up a smaller portion of overall computer users at that point. PCs (still often referred to as "IBM/PC compatibles" at the time) being the larger market and thus a source of larger potential profits, that was where the majority of developers focused their attention. The hassles of porting a game to Mac, whether handled by the original developer or farmed out to somebody else, were frequently judged not to be worth the potential profit. At times, it was determined not to be profitable in the first place.

There were a few games – Myst comes immediately to mind – that bucked this trend, but most Mac games only became influential once they crossed over to PCs, like... Well, like Myst did. The Mac ecosystem just wasn't big enough for anything that happened in it exclusively to influence the wider world of PC gaming.

Actually, let's go with that ecosystem analogy for a minute.

Mac gaming in the early 90s was sort of like Australia. It's a tiny system that only accounted for a small percentage of the biosphere. It had its own unique creatures, similar to animals occupying equivalent ecological niches elsewhere in the world. But on closer inspection, these turned out to all be very different from their counterparts, often in fundamental ways. And then you had some creatures with no real equivalents elsewhere. There was a lot of parallel evolution.

Case in point: Marathon.

Being released a scant eleven days after Doom, you definitely can't accuse it of being one of the imitators. It didn't happen in a vacuum, though.

Its creators, Bungie, were a sort of oddball company whose founders openly admitted that they started off in the Macintosh market not because of any fervent belief in the superiority of the platform, but because it was far less competitive than the PC market at the time.

They started off with Minotaur: The Labyrinths of Crete, a multiplayer-only (more or less) first-person maze game, and followed it up with Pathways Into Darkness.

Pathways was meant to be a sequel to Minotaur at first, until it morphed into its own thing over the course of its development. In genre terms, it's most like a first-person shooter. Except there are heavy adventure game elements, nonlinearity, and multiple endings depending on decisions you make during the game, which are pretty foreign to the genre. It also features a level of resource scarcity that wouldn't be at all out of place in a survival horror game.

Incidentally, I would love to see a source port of Pathways Into Darkness. It is its own weird, awkward beast of a game, and I would dearly love to be able to play it, after having seen only maybe ten minutes of gameplay at a friend's house one time when I was about twelve.

They followed this up with the original Marathon.

Doom is largely iterative. It follows on from a tradition of older FPS games made by its developer, like Wolfenstein 3D and Catacombs 3D. Like those predecessors, it relegates the little apparent story to pre-game and post-game text, and features a very video game-y structure that relies on discrete levels and fast, reflex-oriented play. It adds complexity and sophistication to these elements as seen in previous games, introducing more enemies, more weapons, and more complex and varied environments, then layers all of this on top of an already proven, solid gameplay core.

Marathon, by contrast, simplified and distilled the elements of previous games by its developer. It opts to be more clearly an FPS (as we understand it in modern terms) than any of its predecessors, shedding Pathways' adventure elements and non-linearity while increasing the player's arsenal. However, it's still less straightforward than Doom's pure level-by-level structure. Marathon presents itself as a series of objectives given to the player character (the Security Officer) by various other characters to be achieved within the level. These can range from scouting out particular areas, to ferrying items around the level, to clearing out enemies, to rescuing friendly characters, and so on.

Marathon's story, unlike Doom's, is front and center. Where Doom leaves the player to satisfy themselves that they are slowly progressing toward some ultimate enemy with every stage, Marathon gives the player concrete goals each step of the way, framing each objective as either a way to gain advantage over the enemy, or to recover from setbacks inflicted by them. Doom's story is focused on the player character and their direct actions. For narrative purposes, anything happening beyond your ability to observe is irrelevant. Marathon instead opts to give the player a feeling that although they are the one making crucial things happen in the story, they are not directing the action themselves.

Which brings me to something interesting about Marathon's story.

The player character, the Security Officer, has surprisingly little agency within the narrative. At a guess, I'd say that's because it would be almost impossible to express his own thoughts and emotions with the way the plot is relayed. It's true that most games -- especially in the FPS genre -- tell you what to do. Rescue the princess. Save the world. Prevent nuclear catastrophe. Etc. Etc. But this is normally done in an abstract sense, by presenting you a clear goal and some means to achieve it. Even open-world games like The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim have an overarching goal that you're meant to be slowly working your way toward.

But while your actions in a given game are generally understood to be working toward the stated goal, the player is usually presented in the narrative as having a choice – or perhaps more accurately as having chosen prior to the beginning of the game proper – regarding whatever path the game puts them on. Mario has chosen to go save Princess Toadstool. Link has chosen to go find the pieces of the Triforce and save Princess Zelda. Sonic has chosen to confront Doctor Robotnik. Even the Doom Guy has chosen to fight the demons infesting the moons of Mars on his own rather than saying "fuck it" and running. The reasons for these choices may in some cases be left up to the player to sort out or to apply their imagination, but the point remains. These characters have chosen their destinies.

The Security Officer from the Marathon trilogy, by contrast, does not. Throughout the games, he is presented as following orders. "Install these three circuits in such-and-such locations". "Scout out this area". "Clear the hostile aliens out of this section of the ship". And so on, and so forth. Even in the backstory, found in the manual, the character is just doing his job, responding to a distress call before he fully realizes the sheer scale of the problem. The player, as the Security Officer, is always moving from one objective to the next on the orders of different AI constructs who happen to be in control of him – more or less – at a given time. The Security Officer is clearly a participant in events, but he lacks true agency.

In fairness, it must have been hard to figure out how to tell a compelling story within the context of a first-person shooter back in the early 90s, which is why so few people did it.

I'm not enough of a programmer to be able to explain it well (understatement; I'm not any kind of programmer), but the basic gist of it is that games like Doom weren't technically in 3D. The environments were rendered in such a way that they appeared in three dimensions from the player's perspective, but as earlier versions of source ports like ZDoom made clear, this was an illusion, one that was shattered the moment you enabled mouse aiming and observed the environments from any angle other than dead-ahead. The enemies, meanwhile, were 2D sprites, which was common in video games of any type for the day.

This was how Marathon was set up as well. It's how basically every first-person shooter worked until the release of Quake – and some after it.

The problem is that this doesn't lend itself very well to more cinematic storytelling. Sprites tended not to be very expressive given the lower resolutions of the day. At least, not sprites drawn to relatively realistic proportions like the ones in Doom and Marathon. So you couldn't really do cinematic storytelling sequences with them, and that left only a handful of other options for getting your story across.

You could do what I tend to think of as Dynamic Stills, a la Ninja Gaiden on the NES. At its best, it enables comic book-style storytelling, but that's about as far as it goes.

You can do FMV cutscenes, which at the time basically involved bad actors in cheap costumes filmed against green screens or really low-budget sets. CG was relatively uncommon (and likely prohibitivesly expensive) even in the mid-90s.

You can do mostly text, interspersed throughout your game.

You can just not have much story at all.

Doom opted for option four. John Carmack has been quoted as saying that story in video games is like story in porn. Everybody expects it to be there, but nobody really cares about it.

I disagree with this sentiment pretty vehemently, as it happens. There are some games that aren't well served by a large amount of plot, and Doom is definitely one of them. But to state that this is or should be true for the medium as a whole is frankly ridiculous.

There's something refreshing, almost freeing, about a game that has less a story than a premise. Doom starts off on Phobos, one of the moons of Mars, which has been invaded by demons from hell. They've gained access by virtue of human scientists' experimentation with teleportation technology gone horribly, horribly wrong. The second episode sees you teleported to Deimos, which as been entirely swallowed up by Hell, and which segues from the purely technological/military environments of Doom to more supernatural environs. Episode 3 has you assaulting Hell proper. Doom II's subtitle, Hell on Earth, tells you pretty much everything you need to know about the setting and premise of the game.

That's it. There are no characters to develop or worry about. It's just you as the lone surviving marine, your improbably large arsenal, and all the demons Hell can throw at you. Go nuts.

Bungie, meanwhile, took a different approach. I can't seem to find out which of their founders said it, but they have been on record as basically being diametrically opposed to Id Software in their attitude about story. "The purpose of games is to tell stories." I wish I knew who at Bungie said that.

Marathon is very much a story-oriented game. Of the aforementioned methods of storytelling, they opted for option three: text, and lots of it.

Marathon's story is complex and labyrinthine, especially as it continues through the sequels (Marathon 2: Durandal and Marathon Infinity), and is open to interpretation at various points. Much is left for the player to piece together themselves. Aside from the player character, the story mainly centers on the actions of three AI constructs: Leela (briefly), Durandal, and Tycho. Their actions, in the face of an invasion by a race of alien slavers called the Pfohr, drive the story.

Their words and actions are relayed to the player by way of text at terminals scattered throughout the game's environments. Some of these take the form of orders and objectives given by the AI to the player character, the Security Officer. Some of these are more musings or rants (two out of the three AIs you work for over the course of the Marathon trilogy are not exactly all there), which serve to flesh out events happening beyond the player's observations, and help build the world. Some of these are seemingly random bits of background information, presented as if they were being accessed by someone else (often an enemy) before they were distracted by something – usually you, shooting everything in sight.

Design-wise, there are some interesting differences.

Doom is old-school from a time when that was the only school, with levels that strike a nice balance between video game-y and still giving at least a vague sense that they were built to be something other than deathtrap mazes. But what makes them old-school, at this point, is the fact that they're levels, with discrete starting and ending points, where your goal is to move from the former to the latter and hit the button or throw the lever to end it and begin the next one.

There's no plot to lose the thread of, no series of objectives for you to lose track of if you put the game down for a week, or a month, or longer still. It's extremely pick-up-and-play, equally well suited to killing twenty minutes or a whole afternoon, as you like.

The appeal (aesthetics aside) of Doom is also at least in part its accessibility. It has a decently high skill ceiling (which is to say, the level of skill required to play at an expert level), but a surprisingly low skill floor (the level of skill required to play with basic proficiency), which has lent it a certain evergreen quality. And Id Software has been keen to capitalize on this. Doom is one of a small number of PC games (Diablo II is the only other one I can think of off the top of my head; what is it with games that have you fighting demons from Hell?) that have been commercially viable and available basically from the day they were released. In addition to DOS on PCs, Doom was rejiggered for Windows 95, and also (eventually) saw release for Mac. Also, it's been sold for multiple consoles: the Super NES, the Sega 32X (regrettably), the Atari Jaguar (also regrettably), the PlayStation, the N64, the Xbox 360, the PlayStation 3, and the Xbox One (the 360 version again, via backward compatibility). And source ports have kept the PC version alive and kicking, adding now-standard features like mouse aiming, particle effects, and support for widescreen displays.

The result is a game that, if you don't mind pixelated graphics, is as ferociously playable today as it was twenty-four years ago (as of this writing), and has enjoyed a kind of longevity usually not seen outside the realm of first-party Nintendo classics.

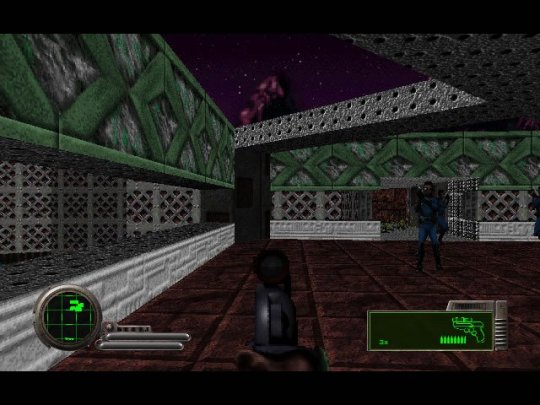

Marathon by contrast is somewhat less inviting.

From a technical standpoint, Marathon is more or less the equal of Doom. The environments throughout the series are rendered at a somewhat higher resolution, but the enemies are less well animated. Marathon also introduced the idea of mouse aiming to the FPS genre, and allowed the player to use that to look (and aim) vertically, which hadn't been done before either. Even Doom, though it also introduced more vertical gameplay, locked the player's movement to the strictly horizontal; vertical aiming was accounted for automatically, although source ports have modernized this. Marathon leans into its verticality a little more as a result, and level layouts are more complex, bordering on the impossiblely convoluted without the aid of your automap.

While I wouldn't go so far as to say that Marathon would classify as a survival horror game, there are some elements of that genre in it. This is almost certainly unintentional, and I'm identifying them as such retroactively (the genre hadn’t really arrived yet). Still, they exist. Ammunition is more scarce than in Doom, forcing the player to lean on the lower end of their arsenal far later into the game than Doom does. Some weapons also feature alternate fire modes, which was a genre first.

Health packs are nonexistent; instead, the player can recharge their health at terminals designed for this purpose, usually placed very sparingly. Saving is also handled at dedicated terminals – a decision better befitting a console game, and somewhat curious here. In addition to health, there is also an air gauge, which depletes gradually whenever the player is in vacuum or underwater, and which can be difficult to find refills for.

Marathon also marks the early appearance of weapon magazines in the first-person shooter genre. Doom held to the old design established by Wolfenstein and older games that the player fires their weapons straight from the ammo reserves. If you have a hundred shotgun rounds, then you can fire a hundred times, no reload necessary. The reloading mechanic as we would most readily recognize it seems to have been added for the genre with Half-Life, for reasons of greater realism and introducing tension to the game.

Marathon's version of this, as you might expect for a pioneering effort, is pretty rough. There is no way to manually reload your weapons when you want. Rather, the game will automatically cycle through the reload animation once you empty the magazine. It does helpfully display how many rounds remain in the magazine at all times so you know how many you have left before a reload, and can plan accordingly. But it still exerts the familiar reload pressure, just in a different way. Rather than asking yourself whether you have the spare seconds for a reload to top off your magazine, now you have to ask yourself whether it's wiser to just fire the last few rounds of the magazine to trigger the reload now, when it's safe, so that you have a full magazine ready to go for the next encounter. Marathon's tendency to leave you feeling a little more ammo-starved than Doom makes this decision an agonizing one at times.

Id's game is pretty sparing with the way it doles out rockets and energy cells for the most high-powered weapons, true. But the real workhorse weapons, the shotgun and the chaingun, have ammo lying around in plenty. Past a certain early point in any given episode of Doom or Doom II, as long as you diligently grab whatever ammo you come across and your aim is even halfway decent, you never have to worry about running out. Marathon, by contrast, sees you relying on your pistol for a good long while. Compared to other weapons you find, it has a good balance of accuracy and availability of ammunition.

The overall pacing and difficulty of both games is also somewhat different.

Both games are hard, but in different ways. Doom has enemies scattered throughout a level in ones and twos, but most of the major encounters feature combinations and larger numbers. But the plentiful ammo drops and health packs mean the danger of these encounters tends to be relatively isolated, and encourages fast maneuvering and some risk-taking. If you can make it through a given encounter, you usually have the opportunity to heal up and re-arm before the next one. Doom is centered around its action. It gives you the shotgun – which you’ll be using for most of the game, thanks to its power – as early as the first level if you’re on the lookout for secrets, and by the second level, you really can’t miss it.

Marathon, by contrast, paces itself (and the player) differently. Ammo gets doled out more sparingly, and health recharge stations are likewise placed few and far between (rarely more than one or two in a stage, at least so far as I’ve played, and small enough that they can be easily overlooked). Save points are likewise not always conveniently placed, and the fact that the game has save points means that you can’t savescum, and dying can result in a fair amount of lost progress. The result is that, unless you’re closer to the skill ceiling, you tend to play more carefully and conservatively. You learn to kite enemies, stringing them along to let you take on as few at a time as possible.

The tactics I developed to play games like Doom and later Quake didn’t always serve me very well when I first started playing Marathon. The main danger in Bungie’s game is the death of a thousand cuts. Where Doom attempts in most cases to destroy you in a single fell swoop, Marathon seeks to wear you down bit by bit until you have nothing left, and you’re jumping at shadows, knowing that the next blow to fall may be your last. It encourages more long-term thinking. Similar to a survival horror game, every clip spent and every hit taken has meaning, and can alter your approach to the scenario you find yoruself in.

In short, if Doom is paced like a series of sprints, Marathon is, well... a marathon.

Another interesting difference is how both games deal with their inherent violence.

As games which feature future military men mowing down whole legions of enemies by the time the credits roll, violence is a matter of course. It becomes casual. But both games confront it in different ways.

Doom was one of the games that helped stir up a moral panic in the U.S. in the early to mid-90s (alongside Mortal Kombat, most notably). While I don't agree with it, it was hardly surprising. Doom gloried in its violence. Every enemy went down covered in blood (some of them came at you that way), some of them straight-up liquefying if caught too near an explosion. This is to say nothing of all the hearts on altars or dead marines littering the landscape to provide the proper ambiance.

The idea was simple: You were surrounded by violent monsters, and the only way to overcome them was to become equally violent. The game's fast pace and adrenaline-rushing gameplay only served to emphasize this. Doom isn't a stupid game by any means – it requires a certain amount of cleverness and a good sense of direction in addition to good reflexes and decent aim to safely navigate its levels -- but the primary direction it makes you think in is how? How do I get through this barrier, how do I best navigate through these dark halls, how do I approach this room full of enemies that haven't seen me yet?

Marathon asks those questions as well, because any decent game is constantly asking you those questions, because they are all variations on the same basic question any game of any kind (video games, board games, whatever) is asking you: How do you overcome the challenges the game throws at you using the tools and abilities the game gives you?

The difference (well, the narrative difference, distinct from all the rest) is that Marathon also talks about the violence seemingly inherent in human nature as one of a variety of things in its narrative.

To be fair, Marathon brings it up pretty briefly in its terminal text. But one of the terminals highlights Durandal's musings on the Security Officer, and humankind in general.

Organic beings are constantly fighting for life. Every breath, every motion brings you one instant closer to your death. With that kind of heritage and destiny, how can you deny yourself? How can you expect yourself to give up violence?

Indeed, it may be seen as not just useful, but a necessary and essential component of humanity. Certainly it's vital to the Security Officer's survival and ultimate victory in the story of the games.

And yet, on the whole, Marathon is a less violent game. Or at least, it glories in its violence less. Enemies still go down in a welter of their own blood, because that happens when you shoot a living creature full of bullet holes. But it's less gory on the whole – bloody like a military movie, bloody as a matter of fact, in contrast to Doom's cartoonishly overwrought slasher-flick excess.

And yet it's Marathon that feels compelled to grapple with its violence, to ask what motivates it, not just in the moment, but wherever it appears in the nature and history of humankind.

On the whole, I think I come down on the side of Marathon, personally. Its themes, its aesthetic, and its characters are more to my liking. True, part of this is simply because Marathon has characters. Doom has the player character and a horde of enemies. Even the final boss of each installment has no narrative impact to speak of. They simply appear in order to be shot down. They're presented as the forces behind the demonic invasion, but aside from being bigger and stronger than all the other demons you face, there's no real sense of presence, narratively. And that's fine. But on the balance, I tend to prefer story in my games, and Marathon delivers, even as it's sometimes a bit janky, even as I get the feeling that Bungie's reach exceeded their grasp with it.

I can recognize Doom as the game that's more accessible, and probably put together a little better, and of course infinitely more recognizable. Id still sells it, and generally speaking, it's worth the five whole dollars (ten if you want Doom II as well) it'll cost you on PSN, or Xbox Live, or Steam.

Bungie, meanwhile, gave the Marathon trilogy away for free in the early 2000s. It's how I finally managed to play it, despite never owning a Mac. There are source ports that allow it to be played on PCs (or Linux, even). About the only new development in the franchise was an HD remaster of Marathon 2: Durandal for the Xbox 360. In the same vein as the remasters for Halo or Halo 2, this version changes nothing about the original except to update the graphics and adapt the control scheme for a 360 controller.

I'd love to see a remake of Marathon with modern technology, even though I know it's extraordinarily unlikely to happen. Bungie's occupied with Destiny for the foreseeable future. The most we've gotten in ages is a few Easter eggs. 343 Guilty Spark in the original Halo featured Durandal's symbol prominently on his mechanical eye, which fueled speculation for a little while that perhaps Halo took place in the same continuity. There's another Easter egg in Destiny 2 that suggests two of its weapons, the MIDA Multi-tool and the MIDA Mini-tool, fell out of an alternate universe where Marathon's events occurred instead of Destiny's. But that's been it.

The tragedy of Marathon is that it wasn't in a position for its innovations to be felt industry-wide.

Doom had the better overall playability and greater accessibility. If you were to ask where a lot of FPS genre innovations came from, the average gamer would probably not point to Marathon as the progenitor of those things. Quake would probably get credit for adding mouse aiming (even though it wasn't a standard menu option, and had to be enabled with a console command), or else maybe Duke Nukem 3D. Unreal would most likely get credited as the genesis of alternate firing modes, while Half-Life is probably the one most people remember for introducing the notion of reloading weapons. I'm not totally sure which other FPS would get the nod for mainstreaming the greater presence of story in the genre – probably Half-Life again.

But since it's free, I would strongly recommend giving the Marathon trilogy a spin. It's a little rough around the edges even judged by the standards of its time, but still eminently playable, with a strong story told well. And if it seems at times like the FPS That History Forgot, well, that's because History was mostly looking the other way at the time. It's part of the appeal for me, too. It feels at times like a "lost" game.

Let that add to its mystique.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Canvas and Video Games

Have I talked about my Video Game history? Feels like I have, but I also can’t remember doing so. I’m also running low on possible essay topics, and haven’t finished off any media that I can review[1] recently enough to do that instead…

So, hey, you nerds, let’s talk about Video Games!

Because that’s obviously been a massive influence on my life, what with… my entire brand, really. Egads, am I a nerd, sitting here with a New 3DS in a charging cradle in front of me, trying to work out how to do better quality streams and deciding to write an essay about Video Games.

It all started with my brother, old Foxface himself. As the family lore goes, my parents once didn’t want video games in the house, what with… the social stigma, I guess? It was different times, alright?

Point is, my brother’s speech teacher was all ‘Hey, you know what may help with speech? Video Games! Get him video games.’

And so my parents did, despite any reasonable connection or evidence in the above argument.[2]

So they bought him the Sega Genesis, the only non-Nintendo console we’ve ever owned. He played Sonic the Hedgehog! Also… no. It was mostly just Sonic.

Obviously young Canvas was also interested in the wonder of interactive media, and the running rodent, so I’d watch him play, and occasionally step in as Tails or try to play it myself. And I was terrible at it.

Eventually, the Nintendo 64 was released and added to our fleet of hardware, and we never looked back! Ha ha!

That’s the console that we really cut our teeth on, with it’s many beloved games, from Mario 64, Star Fox 64, Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (first Zelda game I was ever aware of), and so on and so forth. We ended up with most of the major releases.[3] Also Mischief Makers for some reason.

It was also the height of Video Rental stores, though I never got to choose games to rent. Vulpin stuck with Space Station Silicon Valley which… might deserve an HD Remake, to be honest. Such a bizarre premise people would eat up, nowadays.

The Game Boy Color arrived, carrying Pokemon and various shovelware, plus a few Zelda Games. Tried my best with them, but for the longest time I never actually completed a video game, or got that far, though I did finish Johto in Gold, which is something.

Gamecube came out, the Dreamcast died, and I began to become aware of the surrounding culture as my capabilities to use the internet matured. We also continued a trend of our person game libraries for the generation growing larger than the last. Lots of GameCube games.

Animal Crossing was a Christmas gift early in the cycle, and it was the first video game all of the kids in the family played, to various extents. Elder Sister was her usual perfectionist self, paid off her house, then pretty much stopped playing video games forever afterwards. Little Sister still plays the occasional game (mostly Paper Mario), but largely it’s just Foxface and I who are deep into the gaming scene.

But, like so many things, tracking each and every experience would be a rather sisyphean task, so I should try and refocus here.

Video Games have always been a presence in my life, and thus had its effects on my creative self, from imaginary friends to the little stories I’d crafted pacing the backyard. They were my chief insight into narratives and various genres, design (whether costume or set or mechanical). Nintendo Power helped educate me on the concept of news and industry, as well as the community that could grow from a hobby.

In fact, Pokemon was the main driving force behind the event I joke is the time I’ve ever made friends myself,[4] being approached while reading a book related to the franchise during second grade. It was nice.

Learning about the internet and GameFAQs hinted towards the wider world and culture, and eventually I came upon 8-Bit Theater, which fired up my love of comics in a big way. Comics and stories made from and about elements of video games? That’s so cool!

Then Nintendo Acres happened.

The diminishing use of quality sprite work in video games makes me sad, by the way. There’s just something about the GBA/DS era graphics that invokes joy in my heart, by now even Pokemon has left sprite work behind for models, and even kitschy independent games tend for the super minimalistic version of 8-bit and… whatever one would refer to Atari graphics. Had I artistic talent, I would slather my media in 16-bit evocative of Friends of Mineral Town or The World Ends with You.

In fact, I think that’s one of my main hurdles getting invested in Stardew Valley[5] and Undertale. They just look ugly, even by the standards of kitschy 8-bit style. Frisk is malformed, and all the Stardew characters are in the wrong perspective for the rest of the world. Sprite work can be so beautiful, and yet no one puts in the effort anymore.

Look, sprites aren’t the only aesthetic I love, just so we’re clear. If there’s one thing I’ve learned, I just prefer bright, cheery worlds. Tale of Symphonia is one of my favorite games, if not my absolute number one.[6] There’s just something very nice about a fantasy world that looks lush and vibrant, where you’d be happy to live just for the scenery. The Tales series and Rune Factory also made me very positive about oddly intricate characters in fantasy. I’ve never liked the dirt covered fantasy of… let’s say Skyrim. Fantasy should be about escapism, grand adventure in grand landscapes, not the crushing reality of medieval times.

More Ghibli, less brown is what I want in general.

I may be an oddball for the elements I look for in video games. I like RPGs (obviously) but there’s very few members of the genre I actually enjoy. I flat-out can’t stand western Video Game RPGs.

What I usually look for in games is both a compelling narrative and interesting mechanics, with allowance for the ‘Classics’ and trendsetters.[7] This is something I find lacking in Western-Style RPGs, with their focus on customizing and granular stat advancement. Sure, I understand someone’s desire to try and put a popular character in an Elder Scrolls, or place some curious limitation on themselves while crawling around Fallout’s wastelands.

But because the game needs to allow the player to make whoever they want, it severely cripples the writer’s ability to write the “main” character into the plot, lest they step on the agency of the player. So, from my perspective, we end up in one of two situations: the PC is a non-entity in the plot, with the narrative happening around and to them instead of with them. Or, we get a Mass Effect situation, where they treat it like Choose Your Own Adventure, and you end up shooting a dude when you thought you were just going to arrest him.[8] That’s why I much prefer being handed a protagonist with a history and personality.

Now, those familiar with my tabletop philosophies, and namely my disdain for randomized Character Gen because it takes away player agency might be tilting their head at this inconsistency.

Well, it’s a scale thing. I realize Video Games have a limitation, and thus it’s unreasonable to expect it to cater to you completely. Tabletop, however, allows endless narrative possibilities, because it’s being created in the moment. So, with Video Games, I’m more willing to just let the story take me along as an observer, like a TV Show.

Which is to say, I don’t really project on the Player Character, and am I happy with that. It’s a division between game and story that may seem odd, but it’s what I look for: every piece having a narrative purpose, especially the loser who’s carrying us on our back.

So, narratively, I prefer the style of JRPGs (also, I like Anime and it’s tropes, so…). Yet, I have never really gotten engrossed in any Final Fantasy Game, because list combat is very dull. I mean, grindy, set the auto-attack against opponent style of Western RPGs[10] aren’t much better, but at least it’s got a hint of visual interest.

What am I left with? For a while, Tales of Symphonia, but now I’ve got Rune Factory, with it’s rather simple combat, but still mostly fun (helped along by other elements), and especially Fire Emblem, which what I wish battlemat D&D combat could be: quick, clever, strategic.

Though I’ve only played the 3DS installments thus far, due to lack of accessibility to the early games, which I couldn’t be bothered to try when they were released. Did try the first GBA game to be ported over, but that ended up having the worst, most micromanaging tutorial I’ve ever seen, and thus I am incapable of completing the first level.

I know how to play video games, Fire Emblem. I am aware of the base concept of pressing A. Yeesh. You’re worse than modern Harvest Moon games!

I’ve also never gotten invested in military FPSs, as a mixture of finding the gameplay boring, difficulty mastering it, and mockery whenever I was roped into playing one with friends.[11] In general, I don’t like being in first person view, as I find it limiting to controls, and responding to things that get behind me is annoying, because I flail trying to find the source of damage, then die.

Though, with time, my avoidance has decreased. Portal has a first person camera, but in a mixture of a more puzzle focused game and excellent integration of tutorial into gameplay,[12] it takes an agitating limited camera and makes it very workable, while also teaching the player how to interact with a game in first person.

I also played a little Team Fortress 2, and now Overwatch. The difference with those two over, say, Modern Duty or whatever, is the tone. The two games are competitive, yes, but also light hearted and goofy. Death is cheap and non punishing, the addition of powers make character choice widely different and fun, and, when I do get a little frustrated, it’s very easy for me to take a breath say ‘It’s only a game’ and let it go. Which is important when playing video games, sometimes.

Because that’s what games should always be: entertainment. It’s why I don’t try and force myself through games I’m not enjoying or lose interest in (though obviously I do try and come back and finish the plot) and why I very rarely strive for 100% completion. Because I want to enjoy myself, not engage in tedious work.

It’s also why I don’t care about ESports. Because I don’t care about sports. People doing something very well doesn’t really appeal to me. High-level chess players aren’t interesting to watch or study, seeing two teams of muscled people charge one another isn’t fun, and fight scenes with the usual punching and kicking is dull.

Because, what I look for in most cases is novelty.

Seeing a master craftsman make a thing once can be interesting, just to see the process. See a master craftsman make the same thing a 100 times is uninteresting, because nothing new is happening. When it comes to sports and games, it’s more interesting to see novices play, because they mess up in interesting ways, spot and solve problems, and you get to sit back and go ‘Now, I would’ve done this.’

So, yeah, not a big fan of Counterstrike and League of Legends news, even besides the toxic communities.

Public perception of video games turned rather quick in my lifetime. It used to be such a niche hobby, enjoyed by nerds and children and so such. Yet… well times change, don’t they? Obviously children grew up and brought games along with them, but the hobby has expanded to become mainstream, a console being as necessary as a television, where those without are viewed as bizarre, despite it not being a physical need.[13] We all remember the children who noted their family doesn’t have a TV (or keep it in the closet), and I wonder if XBoxes have gained the same traction.[14]

If only tabletop games could get the same treatment.

Though I still wouldn’t be able to find a group, but still…

Now that I’m an employed adult, I have even more control over the games I play. Which means a Wii U and a custom built PC.

That I built myself, because I also enjoyed Lego as a child.

Between the two, I tend to have a wide enough net to catch the games that interest me. Sure, there’s still some PlayStation exclusives I’d love to try (Journey, Team ICO’s works, plenty of Tales games…)[15] but some of those games are slowly drifting over to Steam, and I already have a backlog, so I can wait it out.

That’s my stumbled musings about video games… Oh! I stream them! Over here! Watch me! I love to entertain and amuse!

Also maybe consider supporting me through patreon? Then I can put more resources into being amusing!

And share any thoughts you have. I’ll listen. Until then…

Kataal kataal.

[1] Did finish rereading Yotsuba&! but there’s nothing to say about besides “Read it!” [2] Certainly didn’t help me. [3] Though not Harvest Moon 64. One day, I will slay that whale. One day… [4] The rest are inherited after old friends leave. [5] Someone on Reddit commented its port to the Switch may help scratch the itch left by Rune Factory. They are, of course, dreadfully wrong. [6] I still dislike do rankings. [7] IE, I’m not a big fan of hallway-bound FPS games, but have played through the Half-Life series. Mostly for the connection to Portal. [8] I know it was in the ‘Renegade’ position, but I thought it’d be played as ‘I’ll risk losing the Shadow Broker to book this small fish’ sort of thing. I’m not very clever, okay?[9] [9] I actually never progressed much further than that. Perhaps it’ll be on CanvasPlays someday. [10] I don’t care if you have a list of subversions of this style, by the way. I really don’t. [11] I once annoyed a former friend for not knowing there’s an aim button. I didn’t know this, because I don’t play FPSs. [12] There’s a very nice Extra Credits about this somewhere. [13] Though as a cultural need… [14] Nintendo Consoles, of course and unfortunately, being considered the off-brand. [15] the PS3 port of Tides of Destiny. Yes, it’s a disgrace of a Rune Factory game, and it was also on the wii but… well, sometimes I’m an insane collector![16] [16] I don’t even need a PS3. I can get it used for, like, five bucks from GameStop…

0 notes

Text

Hey, so, I’ve been taking a games and society class for like the past ten weeks, and our final is to post a review somewhere online. Sooooo, this is where it’s going. It’s about NieR: Automata so severe spoiler alert for that game and minor spoilers for NeiR. Read it if you want, but I won’t be mad if you don’t because it’s super long. But even if you don’t, go play both games because they’re really good (even if NieR’s mechanics were a bit funky).

NieR: Automata is a game developed by Platinum Games and published on February 23, 2017. It is the sequel to NieR, which was developed by Square Enix, the publisher of NieR: Automata. The platforms available for this title are the PlayStation 4 and PC. NieR: Automata has been praised for its well-developed and interesting combat, making it a perfect fit as an action game. NieR: Automata provides the player with encounters constantly, as the player must fend off robots at every turn. Much like many other action games, NieR: Automata’s combat has a range of weapons, from light to heavy to ranged. The game also provides a wide array of enemies, as many other action games do, including boss battles, where the player encounters a notable and unique enemy that typically requires the player to fight through many other smaller enemies before the player encounters the boss. However, unlike most action games, NieR: Automata provides the player with an almost countless number of combinations for their weapons, allowing the player the freedom of customization. The game provides the player with two slots, or places, for their weapons and two sets as well. Each weapon has a faster “light” attack and a slower, more powerful “heavy” attack. Then the player is given a pod that allows them a ranged attack as well, in the form of energy bullets. Having forty weapons and numerous different attachments to the pod allows the player to develop a much more unique style of fighting a lot more than some other simple “shoot and slash” action games. NieR: Automata also varies the playable character, which allows for variation of the combat style to include hacking and a berserk mode, in which the character’s attacks are stronger and faster, at the cost of their health.

As mentioned, NieR: Automata is the sequel to NieR, which itself is the sequel to one of the possible endings to Drakengard 2, and the sequel that Yoko Taro believes to be the true sequel (Sato). NieR was developed by Cavia, which disbanded in July 2010 with NieR being its last game produced, and published by Square Enix. NieR: Automata expanded on NieR’s open world, with the new generation of platforms allowing for a larger world and an update on graphics. NieR: Automata kept what worked with the original NieR, a rich storyline with interesting characters, diverse gameplay mechanics, and thrilling music to match the mood set by the story. NieR: Automata had a much more modern feeling to it, however. In NieR, one of the bigger twists is that it takes place in modern times. This is not the case for NieR: Automata and so it does not need to be hidden. NieR: Automata also fixed some of the fighting mechanics, making bosses and enemies more variable and more fun to fight. These changes allowed the sales of NieR: Automata to skyrocket. The original NieR sold around 500,000 copies while NieR: Automata has sold over 2.5 million (Minotti).

One of the feelings that NieR: Automata wants to evoke from its player is the sense of vastness of the world around them. It does this by shifting the perspective to an isometric third-person perspective that is further away from the player. While at times the perspective changes to a side scroller, this third person is the main perspective of the game. By having the world take up a larger portion of the screen, and by allowing more of the horizon to be seen, the game makes the character seem smaller in comparison. The soundtrack also helps to give this impression. Full orchestral pieces with choral singing fills every building, forest, and desert. Having larger music, rather than a simplistic bit tune, gives NieR: Automata a sense of grandeur. The sounds also play a role in perpetuating the sci-fi theme. Menu selections and item pick-ups are accompanied by beeps. Damage taken and deaths result in a sound similar to static on a TV. HUDs (Heads-up display, where important stats, such as health and experience are shown), maps, and character design create a world of technology. However, the player explores a world covered in forests with towering trees, vast oceans, and wild animals.

NieR: Automata is a game that is heavily based in its narrative and the player will not get the full experience if they do not pay attention to the story. The plot revolves around androids that are designed to end the robot invasion that has taken over Earth that caused the humans to leave for the Moon. The main characters, 2B and 9S, are tasked with helping the resistance androids on the surfaces as well as preforming reconnaissance missions for YorHa, the android military. As the player moves around the story, they discover more and more about the robots. Some have disconnected from the network and are trying to live peacefully or they become murderous individuals or they land somewhere in between. The aliens that created the machines have long since died and the robots now run themselves. Many are trying to learn about humans and become more human-like. They create families, follow governments, and explore passions. The characters themselves are a bit muted. 2B is loyal to a fault and a duty-bound soldier. She does not question her orders, just enacts them to the best of her abilities. 9S follows the rules a little less closely, ignoring protocol, rules, and orders when he believes that another plan would be more beneficial. Outside of these characters, there are numerous other reoccurring characters that participate in the main storyline or deal out side quests. Every character placed in the world has a purpose, there is not a character that you can’t interact with, only cast and player characters. As the story continues, some cast characters become player characters.

NieR: Automata’s rich storyline provides numerous opportunities to discuss serious topics. Many of these come in the form of side quests, including exploring the ideas of what purpose an individual has on Earth and philosophy, but others are explored throughout the main storyline. During one mission, robots that had formed a religion witness their leader die and respond with a mass suicide. The robots also attempted to kill those who did follow in their footsteps. This is a commentary on extremism in religion and even goes as far as to include a new enemy that is a suicide bomber. Another mission involves deciding if a character begging for death should be killed, have his memories erased, or left alone. An overarching theme is what it means to be alive and to think. This is explored again and again as machines perform human functions and androids claim that they are nothing more than short-circuiting programs. The distinction between androids and robots is hazy, with every difference being torn away as the game progresses. Another topic explored is autonomy. At a few points in the game, the main characters raise objections to the tasks given to them, but complete them anyway because that is their duty as soldiers.

NieR: Automata is a very well-developed game with unique storytelling, music, gameplay, and enemies. Because of all this it has created a very dedicated fandom, building on the one created from the original NieR. This is most strongly evidenced in the fanart, which follow in the creator’s footsteps of sexualizing the main characters. Fanart, art made of entertainment by fans rather than creators or sanctioned artists, allow the main character to be dressed in much more scanty dressings and also her skirt to be raised up. One of these images is featured on a mousepad or a Yu-gi-oh mat, allowing fans to proudly display their interest in both NieR and the main character. This particular item currently has an average of eighteen views per day (Ebay). Another piece demonstrates the process involved in creating his piece of art (ArtStation). It is unfortunate that this amazing title has been overshadowed by the release of other games such as Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild and Horizon Zero Dawn. This game has much to offer the player in terms of not only entertainment, but also thought-provoking ideas.

Bibliography

2B - Nier:automata, Kinohara Kossuta. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.artstation.com/artwork/vB9Jx

Egenfeldt-Nielsen, S., Smith, J. H., & Tosca, S. P. (2016). Understanding Video Games: The Essential Introduction. New York: Routledge.

F1366 Free Mat Bag NieR Automata Custom Playmat Yugioh MTG Vanguard Mouse Pad | eBay. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.ebay.com/itm/F1366-Free-Mat-Bag-NieR-Automata-Custom-Playmat-Yugioh-MTG-Vanguard-Mouse-Pad-/332147888526

Minotti, M. (2018, April 07). Nier: Automata's Yoko Taro and Takahisa Taura on sentencing characters and turning 2B into a bug. Retrieved from https://venturebeat.com/2018/04/01/nier-automatas-yoko-taro-and-takahisa-taura-on-sentencing-characters-and-turning-2b-into-a-bug/

Sato. (2013, April 05). Drakengard 3 Producer And Creative Director Explain How It Came To Be. Retrieved from http://www.siliconera.com/2013/04/05/drakengard-3-producer-and-creative-director-explain-how-the-game-came-to-be/

0 notes