#but are substituted by the glottal versions

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Enclosed below is a transcription of the piece of paper found in the seat pocket of seat 23 b of Flight UA 8469, translated from Latverian to English. There may be errors in this translation, due to the handwriting deterioration and the damage on the original document.

If you're reading this, whatever he poisoned me with took effect before I could get off this flight and for that I am sorry. My name is, or more likely was, Dr Micah Morbius. As you can probably guess, I am Latverian. What you almost certainly do not know is the disease currently ravaging my home. Dr Victor Von Doom has been careful to conceal its spread from the outside world. However, given that I was the primary researcher on it, if you're reading this I feel no shame in calling for international aid.

My PhD was accelerated due to the crisis, as my theories regarding the potential cure being found in the adaptations of hematophagous animals were extremely promising. But as a single researcher, I could only move so fast. I tried, I really did. But.

I cannot remember if I became infected myself before or after Dr Victor Von Doom introduced me to those colleagues of his. It does not truly matter. In my desperation, I began testing the cures I workshopped with those doctor’s on my self. One of them, an American man located in New York, was especially interested in my work. I am certain it was him who did this.

[Text begins to fully deteriorate here, there was likely a period of time between this and the rest of the note. Much of the text overlapped.]

He did this. He did this and I let him. We did this. I did this. No. No, I did this and he let me.

It’s so hard to think.

I’m. So hungry. I’m so hungry.

It’s so hard to think.

I’m so hungry. I’m so hungry. I’m so hungry.

It’s so hard to think when you're so hungry. When I’m so hungry. I’m so hungry.

I feel my bones moving.

I’m so hungry. I’m so hungry.

He made my bones move. I made my bones move. My bones are moving. Their always moving. Oh God their always moving. Everything is moving. I can hear it. I can hear it. I can hear it. It’s so hard to think.

It is so hard to think like this. It is so hard to think. It is so hard to think.

I can smell it.

It’s so hard to think. It’s so hard to think.

God I’m so hungry. How can you be this hungry? How can I be this hungry? Why won’t they let me eat? I’m so hungry. Why won’t they let me? Why won’t they let me think?

It’s so hard to think.

I’m. So hungry.

I’m so hungry.

It’s so hard to think.

I’m so hungry. I’m so hungry. I’m so hungry.

Please help me.

#apparently Spider-man the Naimated series never said Morbius was Latverian but I’m running with it#fun headcanon baby me#I did a weird amount of research for this one#even for me#for instance Morbius’ speech patterns#s/soft c’s/z/and even th sounds all sound more like sh sounds#but also labiodental f sounds come out wheezed#Interdental (θ ð) are essentially impossible to pronounce normally#but are substituted by the glottal versions#this unfortunately puts a lot of stress on his throat#so everything is a little gravely#my art#specter spider au#morbius#Micah Morbius

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maria Fuwa AUSPICE+ Review

My life is getting busier, with my birthday, work, and a multi-country vacation coming up! That’s why I’ve been writing these so quickly. I reviewed Maria last year, and was asked to look at her again, with her newest voicebank. You all know how much I love her, so this one might be a little more positive than usual!! Maria’s voice type and tone has mostly stayed the same, it’s the small things that have changed.

This review was requested by HIRA(formerly iosion).

*Art by HIRA

Hear a Sample of Maria Fuwa AUSPICE

Bio

Name: 不破マリア (Fuwa Maria) Age: "20" y.o. Gender: Fluid Height: 5'5" (165 cm)

A pyromancer infamous for her unmatched prowess in robot matches. Maria is an extremely competitive person and prioritizes winning above all else. Surprisingly enough, she's no sore loser (or so she claims). She's rather "humble" in contrast to her aggressively competitive nature, but she would always demand a rematch when the opportunity strikes.

Official Site

Maria has a website here on Tumblr. Here is her voicebank page. Please read the TOS before downloading. The full version of AUSPICE voicebank is 945 MB when unzipped and has fully generated frq files. AUSPICE is multiple appends put together, so for a smaller file there are separate download options.

First Impressions

This Maria is intended to be the penultimate version of her. She comes with a set of normal, Soft, and Power pitches as well as Whisper and Screamo appends named Spirit and Howl. I also like the addition of different designs/icons for each append. It’s very cute.

Configuration

Maria is a VCV with each set(Normal, Soft and Power) recorded at A3, D4, F4, and G4. The G3 pitch from Ifrit is omitted, but her low range doesn’t suffer that much for it. Maria isn’t even meant to sing in tenor and lower ranges, so I have no issue with this. Spirit and Howl are monopitch and at F4 and C3 respectively. There are VC endings, and CV aliases. She’s sort of usable as a CVVC, but few would probably choose to use her that way over VCV. VC endings help for added realism though. She comes with glottal stops and vocal fry for all vowel combos, end breaths/inhales, and standalone breaths. The standalone breaths don’t sound very good in the program.

There tends to be a lot of room between different syllables and long consonants. She does have a westernized accent but not a talking tone like overseas UTAUs tend to have. To fix this, setting the consonant velocity to less than 100 sometimes helps.

With more than 20,000 oto lines, it also take a while to get into voicebank settings/view the oto. That’s more a fault of UTAU itself than Maria, though. The oto uses a usual 1:3 ratio of 80:240 for preutter/overlap. This also goes for the VC endings. The samples feel a bit cut off and it removes some of the uniqueness from the power append, but I can see why this was done.

Her power append is a more natural sort of power and not screaming/shouting like a lot of other UTAUs go for. It does cause the normal and power pitches to sound a little similar, but listening enough reveals a clear difference.

Spirit and Howl are interesting, the screamo append is recorded in a lower register which I’ve never seen before. They both require the use of tn_fnds in order to draw out their intended sound but TIPS is an okay substitute. Spirit is so quiet it’s often tough to integrate with the other pitches, even the soft ones.

My recommended flags: F0B0Y0H20C99P89

My recommended resamplers: wavtool4vcv(wavtool), TIPS, tn_fnds, doppeltler

Final Thoughts

Maria may have changed but she is still peak UTAU. She deserves to be used more, and I don’t say that a lot.

Got any other UTAUs you want me to review? Send an ask!

#maria fuwa#fuwa maria#utau#utauloid#review#requested review#thanks for asking again nicely hira#request

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

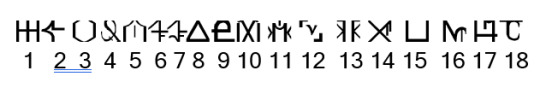

So these are the 18 letters of the secret alphabet, which if you compare you’ll realize are very simplified versions of the calligraphy on Lux’s medallion. Mainly, they represent sound segments of words--basic consonants and vowels. I’m going to go through them by number and talk about the sounds they represent in Ashtivan first, and then how the factory lux use them when writing other languages.

Some notes if you do want to attempt to decipher: messages are projected one syllable or one one-or-two-symbol shorthand phrase at a time. so like the second message begins

THE

RE

DUK

SHUN

written out completely phonetically, which if you say out loud is of course “the reduction.” This keeps the projected space small and discreet, and also “chunks” long words to help readability since most factory units know the alphabet well enough to use a filing system but weren’t formally taught to read.

#1

In Ashtivan: [ɪ] (short i sound)

Used for: In-universe, this sound doesn’t appear much in Altamaian, although in the story they do use it for the English short i. This sign, which is the final sound in the Ashtivan words for “who”, “when”, “why,” and “how”, is also used like a question mark.

#2

In Ashtivan: [bh] (aspirated b) or [v] (depending on where it is in the word)

Used for: Since Ashtivan doesn’t have the f sound, this symbol is subbed in. Standing alone, it’s a shorthand for “right, yes, correct.”

#3

In Ashtivan: [ɨ] (form an “o” with your lips but say “ee”)

Used for: The long-e [i] sound in English and Altamaian.

#4

In Ashtivan: [e] or [ə] (schwa, the “uh” sound in “the”)

Used for: Literally any “uh” sound whether it’s technically a schwa or not.

#5

In Ashtivan: [m] or [n] or [ (the “ng” sound). Ashtivan phonology works in such a way that you tell which sound is meant based on the vowels around it.

Used for: All m’s, n’s, and ng’s!

#6

In Ashtivan: [t] or [d] (Again, vowels determine which it is)

Used for: [t] and [d] sounds, but also used alone as a quasi-noun referring to superiors and “proper” astraeas, usually translatable as “she” or “they” though perhaps most accurately glossed “the powers that be.”

#7

In Ashtivan: [kh] (aspirated k) or [g]

Used for: English and Altamaian [k] and [g]

#8

In Ashtivan: [l] or [ɫ] (sounds kind of like a simultaneous “l” and “s”; it’s a sound that appears in some Welsh words).

Used for: English and Altamaian [l], but also used alone for all variants of the verbs “to do” and “to be.” Letters 8 and 7 side by side is a “word” used interchangeably for you, me, us, lux/lux units, and she/her (when the one referred to is a lux).

#9

In Ashtivan: [ʊ] (long u “oo” sound) or [ɤ] (an “uh” sound but with “oo” lips)

Used for: [ʊ] sounds, but also in a roundabout way as a substitute for the English r sound. If you run into a mess of vowels that don’t seem to make sense it’s probably an attempted r. (Main-character Lux has gotten good at r since living in America with the radio constantly on for several decades, but she still kind of swallows it in fast speech. It’s just not really in Ashtivan at all).

#10

In Ashtivan: [G], [ʔ], and [ɦ] (all uvular or glottal consonants)

Used for: Since besides the basic glottal stop these sounds are barely in standardized English or Altamaian, the symbol is used grammatically, as a way to say “must”/ “have to” or mark a verb phrase as imperative. It’s also used as like, an emoji representing orders/assignments.

#11

In Ashtivan: [ɛ] (short-e ”ehh” sound)

Used for: Same sound.

#12

In Ashtivan: [ʃ]/[ʃj] ( “sh” sound and “sh” sound with a consonant y attached), [ʂ]/[ʂj] and sometimes [s]/[sj]

Used for: [ʃ], combined with #6 for “ch”. Combined with #17 to mean “beginning, start, origin, initiation”; #17 + #12 + #14 = “first,” “beforehand.”

#13

In Ashtivan: [j] (the y sound)

Used for: Same sound

#14

In Ashtivan: [ç] (hard s-like sound produced with the tongue further back in the mouth)

Used for: Most “s” and “z” sounds, especially at ends of words. The symbol is also a “time marker”--at the beginning of a phrase, it signifies past tense; at the end it signifies future tense; and inserted before the verb phrase it means “already” or “currently.”

#15

In Ashtivan: [ɔ] (like “o” with a more open mouth)

Used for: Occasionally the English o sound, but most often--because it looks like an empty vessel--for negative descriptors like “non-”, “off”, “disused.” Combined with the verb-making symbol (below) it creates a phrase meaning “to decommission” which is better translated as “to nullify” or even “to off.”

#16

In Ashtivan: [æ] (long-a ayyyyyy sound)

Used for: Same sound, but also as an ability marker “be able to.” Combined with #15 to mean “can’t.”

#17

In Ashtivan: [ɑ] (short-a ahhhh sound)

Used for: Same sound and as a verb-making morpheme similar to English “ing.”

#18

In Ashtivan: [w]

Used for: Same sound.

#conlangs#languages - ashtivan#secret lux alphabet#short stories#letters from tropovoxia#sweet chariot#lux class stuff

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

This Egyptian Grain Bowl Is the Pantry Wonder-Dish We Need Right Now

Anny Gaul

Koshari is filling, flavorful, easy to make, and basically perfect

Last September, the Egyptian fast-casual chain Zooba opened a branch in Lower Manhattan. Among Egyptian classics like taameya and hawawshi, one of the most popular dishes on the menu from the start has been koshari — a centuries-old grain bowl that’s suddenly found itself an unlikely global “it” food. Manhattan’s Zooba is just the latest in a series of hot spots in cities like Cairo, Berlin, London, and New York that are serving the ancient staple to an entirely new and very eager customer base.

The appeal of koshari is easy to understand. It’s both filling and delicious — a mess of complex carbs and protein muddled with a range of acidic notes. A base of rice, lentils, chickpeas, and macaroni is shot through with sauces that meld tomato, hot pepper, vinegar, and garlic, and the whole thing is topped with crispy fried onions. But while it’s a fast-casual trend around the world, in Egypt, koshari is better known as a historic national dish, one that gracefully straddles the divide between street food and home cooking.

It’s also the perfect food for pantry cooking in an age of stay-at-home orders and two-hour supermarket queues. With a long history as a hardy, adaptable, filling meal of choice among traders and travelers, it’s designed to provide maximum nutrition and flavor from cheap, accessible ingredients and local trimmings. If you have an assortment of starches, pulses, and alliums on hand, plus some vinegar and tomato sauce or tomato paste, then koshari’s delights are within your reach.

“Egyptians have a long history of hodgepodge cooking, stuffing carbs with even more carbs — and we aren’t the only ones.” — Egyptian novelist Nael El Toukhy

Koshari’s history has always been something of a mystery. One thing most Egyptians agree on is the dish’s connection to khichidi (sometimes spelled kitchari), an Indian dish that is also built on the winning combination of grains and pulses — a catchall term for the edible seeds of legumes like beans and lentils. But how did it get to Egypt?

Most popular accounts cite Britain’s occupation of Egypt, which began in 1882 and was accomplished with the help of Indian troops. While it’s perfectly plausible, even likely, that Indian soldiers brought khichidi with them to Egypt, they probably weren’t the first or the only such link in koshari’s history: Centuries of earlier, sometimes indirect, connections between Egypt and India likely also form part of the dish’s evolution. As the powerhouse rice-and-lentils combo traveled along the pilgrimage and trade routes that have connected South Asia to Arabia to Egypt via the Red Sea for centuries, it absorbed new ingredients and flavors along the way.

Today, traces of rice-and-lentil dishes dot the ports and coastal regions that long tied Egypt and India together. The crews of dhows — short-range sailing vessels of the Red Sea and Indian Ocean — once ate a dish made with rice, lentils, ghee, and hot peppers, according to one traveler’s account from the 1930s. Food scholar Sami Zubaida recalls a weekly meal of rice, lentils, tomato paste, and garlic during his childhood in Baghdad, adding that the dish was also well-known in Iraq’s port city of Basra. It was Zubaida who pointed me in the direction of several 19th-century British accounts that placed koshari — or something very like it — along the east coast of the Arabian peninsula as well as in Suez, an Egyptian port at the northernmost end of the Red Sea. An East India Company official stationed there in the 1840s described the locals eating a mixture of lentils and rice cooked with ghee and flavored with “pickled lime or stewed onions.”

Zooba [Official]

Two versions of the Koshari served at New York’s Zooba pre COVID-19, now available for takeout and delivery

In 1941, Egypt’s most famous cookbook, known as Kitab Abla Nazira, included two koshari recipes, one with yellow lentils and one with brown lentils. But before its canonization in a cookbook written for middle-class housewives, koshari was likely best known as a local street food. British public health authorities granted a license to a street vendor peddling “rice and macaroni” in 1936. It’s a vague archival detail, but I like to think it may have referred to Cairo’s first recorded koshari cart.

The addition of pasta and tomato sauce to koshari was a testament to the considerable influence of the Italian communities in Cairo and Alexandria at the time, which infused everything from the local diet to its dialect. (Modern Egyptian Arabic is peppered with Italian loanwords for everything from a Primus stove — “wabur,” from “vapore” — to the check at a restaurant, “fattura.”) Pasta and tomato sauce offered cheap ways to stretch koshari’s portions even further.

Contemporary koshari is commonly served with as many as three different dressings: a tomato sauce, a local hot sauce called shatta, and a garlicky, vinegar-based dressing called da’ah (pronounced with a glottal stop in the middle, like “uh-oh”).

Even today, koshari is never just one thing. Within Egypt, variations abound: Yellow lentils are associated with Alexandrian koshari, while Cairene koshari typically features brown lentils. Many home cooks told me how they’d tweak their mother’s or grandmother’s recipes, swapping in whichever pulses or pasta shapes they prefer or adding more spice. Sometimes elements of the dressings are combined, like hot pepper added to the tomato sauce, for example. There are variants topped with an egg or a smattering of chicken livers. Cairo Kitchen, another fast-casual Egyptian restaurant specializing in homestyle meals, introduced brown rice and gluten-free variations of koshari. And further afield, Koshary Lux in Berlin serves up koshari with jasmine rice, beluga lentils, and caramelized rather than fried onions.

For now, the signature neon lights of Zooba���s Nolita dining room are switched off, just like the lights on the Nile party boats in Egypt they’re meant to resemble. Until they light up again (it recently opened for takeout and delivery!), the world’s original flexitarian grain bowl is easy enough to make yourself.

Anny Gaul

Koshari is less about one ingredient than the right mix of textures and tastes.

Build-Your-Own

The robust grain-and-pulse genre provides a handy template for building a grain bowl from whatever’s on hand. For some good jumping-off points, try Meera Sodha’s twist on kitchari; Maureen Abood’s take on koshari’s Levantine country cousin, mujadara; or novelist Ahdaf Soueif’s koshari recipe. But koshari doesn’t so much require a hard-and-fast recipe as it does a list of stuff to put in a bowl, and a mixture of contrasting textures and tastes is more important than any one ingredient. Here, then, is a basic guide to building your own koshari-inspired pantry grain bowl.

Step 1: Form a base

The foundation of the dish should include at least one grain (rice, pasta, or in a pinch, bulgar, freekeh, or even couscous) and one pulse (lentils, chickpeas). Today’s koshari typically includes at least two of each (chickpeas, lentils, rice, and pasta), but you can always keep it simple, like many earlier versions of the dish, with just rice and lentils.

Aim for short pastas, such as elbow macaroni; for longer pastas like vermicelli and spaghetti, break into pieces before cooking. Most koshari recipes call for a grain-to-pulse ratio of at least 2 to 1. Increase the ratio to stretch the recipe into more servings; decrease it for a lighter meal.

The culinary teams at Zooba and Cairo Kitchen suggested that preparing multiple ingredients in the same pot is the secret to rich, homestyle flavors (also fewer dishes!), so feel free to cook your lentils and rice together.

Step 2: Sauce it

Sauces and dressings can make or break a grain bowl. If you have a jarred marinara-style tomato sauce — ideally something with tomatoes, onion, and garlic — on hand, warm it up and stir it right into your koshari or mix in a bit of your favorite hot sauce first. If you only have tomato paste, improvise a substitute by stirring in some hot sauce and olive oil.

Then you need something with a little more garlic and acid. Whip up a quick dressing with some crushed fresh garlic and cumin steeped in white vinegar (traditional) or lime juice (nouveau). You can also start with a basic citrus vinaigrette and experiment with layering other dressings on top, like a drizzle of pomegranate molasses or a balsamic glaze. A squeeze of fresh citrus never hurts.

Classic koshari is topped with crispy fried onions, which you can replicate with whatever alliums you have on hand, some oil, and a microwave, one of my favorite hacks. Reserve the oil and toss it with the pulses and grains, and add a dollop of butter or ghee for even more richness. For a crunch that doesn’t involve frying things in hot oil but still feels Egyptian, try dukkah, an Egyptian seed and spice mix.

Step 3: Customize

From there, you can pepper in some caramelized onions or add your favorite pickles, fresh herbs, greens, or a soft-boiled egg. Follow the lead of dhow sailors with some hot chiles or pickled citrus.

Step 4: Eat for days

Koshari’s reliance on so many shelf-stable ingredients makes it great for cooking from the pantry, but it can also make the process of preparing it daunting. Pace yourself and split the preparation over a couple of days, remembering that most grain bowl ingredients can be building blocks for multiple meals. If you’re planning a pasta dinner with a green salad on the side, make some extra tomato sauce and a garlicky vinaigrette to dress your koshari the next day. And as you well know, crispy onions make anything better.

So the next time you look to your own pantry for dinner inspiration, borrow a page from koshari’s long, global tradition of piling together sturdy nonperishables with the zingiest trimmings on hand — for a combination that has been satiating sailors, traders, street vendors, and home cooks for centuries.

Anny Gaul is a food historian, blogger, and translator. She’s currently a fellow at the Center for the Humanities at Tufts University.

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/2SZaQbK https://ift.tt/3buf55u

Anny Gaul

Koshari is filling, flavorful, easy to make, and basically perfect

Last September, the Egyptian fast-casual chain Zooba opened a branch in Lower Manhattan. Among Egyptian classics like taameya and hawawshi, one of the most popular dishes on the menu from the start has been koshari — a centuries-old grain bowl that’s suddenly found itself an unlikely global “it” food. Manhattan’s Zooba is just the latest in a series of hot spots in cities like Cairo, Berlin, London, and New York that are serving the ancient staple to an entirely new and very eager customer base.

The appeal of koshari is easy to understand. It’s both filling and delicious — a mess of complex carbs and protein muddled with a range of acidic notes. A base of rice, lentils, chickpeas, and macaroni is shot through with sauces that meld tomato, hot pepper, vinegar, and garlic, and the whole thing is topped with crispy fried onions. But while it’s a fast-casual trend around the world, in Egypt, koshari is better known as a historic national dish, one that gracefully straddles the divide between street food and home cooking.

It’s also the perfect food for pantry cooking in an age of stay-at-home orders and two-hour supermarket queues. With a long history as a hardy, adaptable, filling meal of choice among traders and travelers, it’s designed to provide maximum nutrition and flavor from cheap, accessible ingredients and local trimmings. If you have an assortment of starches, pulses, and alliums on hand, plus some vinegar and tomato sauce or tomato paste, then koshari’s delights are within your reach.

“Egyptians have a long history of hodgepodge cooking, stuffing carbs with even more carbs — and we aren’t the only ones.” — Egyptian novelist Nael El Toukhy

Koshari’s history has always been something of a mystery. One thing most Egyptians agree on is the dish’s connection to khichidi (sometimes spelled kitchari), an Indian dish that is also built on the winning combination of grains and pulses — a catchall term for the edible seeds of legumes like beans and lentils. But how did it get to Egypt?

Most popular accounts cite Britain’s occupation of Egypt, which began in 1882 and was accomplished with the help of Indian troops. While it’s perfectly plausible, even likely, that Indian soldiers brought khichidi with them to Egypt, they probably weren’t the first or the only such link in koshari’s history: Centuries of earlier, sometimes indirect, connections between Egypt and India likely also form part of the dish’s evolution. As the powerhouse rice-and-lentils combo traveled along the pilgrimage and trade routes that have connected South Asia to Arabia to Egypt via the Red Sea for centuries, it absorbed new ingredients and flavors along the way.

Today, traces of rice-and-lentil dishes dot the ports and coastal regions that long tied Egypt and India together. The crews of dhows — short-range sailing vessels of the Red Sea and Indian Ocean — once ate a dish made with rice, lentils, ghee, and hot peppers, according to one traveler’s account from the 1930s. Food scholar Sami Zubaida recalls a weekly meal of rice, lentils, tomato paste, and garlic during his childhood in Baghdad, adding that the dish was also well-known in Iraq’s port city of Basra. It was Zubaida who pointed me in the direction of several 19th-century British accounts that placed koshari — or something very like it — along the east coast of the Arabian peninsula as well as in Suez, an Egyptian port at the northernmost end of the Red Sea. An East India Company official stationed there in the 1840s described the locals eating a mixture of lentils and rice cooked with ghee and flavored with “pickled lime or stewed onions.”

Zooba [Official]

Two versions of the Koshari served at New York’s Zooba pre COVID-19, now available for takeout and delivery

In 1941, Egypt’s most famous cookbook, known as Kitab Abla Nazira, included two koshari recipes, one with yellow lentils and one with brown lentils. But before its canonization in a cookbook written for middle-class housewives, koshari was likely best known as a local street food. British public health authorities granted a license to a street vendor peddling “rice and macaroni” in 1936. It’s a vague archival detail, but I like to think it may have referred to Cairo’s first recorded koshari cart.

The addition of pasta and tomato sauce to koshari was a testament to the considerable influence of the Italian communities in Cairo and Alexandria at the time, which infused everything from the local diet to its dialect. (Modern Egyptian Arabic is peppered with Italian loanwords for everything from a Primus stove — “wabur,” from “vapore” — to the check at a restaurant, “fattura.”) Pasta and tomato sauce offered cheap ways to stretch koshari’s portions even further.

Contemporary koshari is commonly served with as many as three different dressings: a tomato sauce, a local hot sauce called shatta, and a garlicky, vinegar-based dressing called da’ah (pronounced with a glottal stop in the middle, like “uh-oh”).

Even today, koshari is never just one thing. Within Egypt, variations abound: Yellow lentils are associated with Alexandrian koshari, while Cairene koshari typically features brown lentils. Many home cooks told me how they’d tweak their mother’s or grandmother’s recipes, swapping in whichever pulses or pasta shapes they prefer or adding more spice. Sometimes elements of the dressings are combined, like hot pepper added to the tomato sauce, for example. There are variants topped with an egg or a smattering of chicken livers. Cairo Kitchen, another fast-casual Egyptian restaurant specializing in homestyle meals, introduced brown rice and gluten-free variations of koshari. And further afield, Koshary Lux in Berlin serves up koshari with jasmine rice, beluga lentils, and caramelized rather than fried onions.

For now, the signature neon lights of Zooba’s Nolita dining room are switched off, just like the lights on the Nile party boats in Egypt they’re meant to resemble. Until they light up again (it recently opened for takeout and delivery!), the world’s original flexitarian grain bowl is easy enough to make yourself.

Anny Gaul

Koshari is less about one ingredient than the right mix of textures and tastes.

Build-Your-Own

The robust grain-and-pulse genre provides a handy template for building a grain bowl from whatever’s on hand. For some good jumping-off points, try Meera Sodha’s twist on kitchari; Maureen Abood’s take on koshari’s Levantine country cousin, mujadara; or novelist Ahdaf Soueif’s koshari recipe. But koshari doesn’t so much require a hard-and-fast recipe as it does a list of stuff to put in a bowl, and a mixture of contrasting textures and tastes is more important than any one ingredient. Here, then, is a basic guide to building your own koshari-inspired pantry grain bowl.

Step 1: Form a base

The foundation of the dish should include at least one grain (rice, pasta, or in a pinch, bulgar, freekeh, or even couscous) and one pulse (lentils, chickpeas). Today’s koshari typically includes at least two of each (chickpeas, lentils, rice, and pasta), but you can always keep it simple, like many earlier versions of the dish, with just rice and lentils.

Aim for short pastas, such as elbow macaroni; for longer pastas like vermicelli and spaghetti, break into pieces before cooking. Most koshari recipes call for a grain-to-pulse ratio of at least 2 to 1. Increase the ratio to stretch the recipe into more servings; decrease it for a lighter meal.

The culinary teams at Zooba and Cairo Kitchen suggested that preparing multiple ingredients in the same pot is the secret to rich, homestyle flavors (also fewer dishes!), so feel free to cook your lentils and rice together.

Step 2: Sauce it

Sauces and dressings can make or break a grain bowl. If you have a jarred marinara-style tomato sauce — ideally something with tomatoes, onion, and garlic — on hand, warm it up and stir it right into your koshari or mix in a bit of your favorite hot sauce first. If you only have tomato paste, improvise a substitute by stirring in some hot sauce and olive oil.

Then you need something with a little more garlic and acid. Whip up a quick dressing with some crushed fresh garlic and cumin steeped in white vinegar (traditional) or lime juice (nouveau). You can also start with a basic citrus vinaigrette and experiment with layering other dressings on top, like a drizzle of pomegranate molasses or a balsamic glaze. A squeeze of fresh citrus never hurts.

Classic koshari is topped with crispy fried onions, which you can replicate with whatever alliums you have on hand, some oil, and a microwave, one of my favorite hacks. Reserve the oil and toss it with the pulses and grains, and add a dollop of butter or ghee for even more richness. For a crunch that doesn’t involve frying things in hot oil but still feels Egyptian, try dukkah, an Egyptian seed and spice mix.

Step 3: Customize

From there, you can pepper in some caramelized onions or add your favorite pickles, fresh herbs, greens, or a soft-boiled egg. Follow the lead of dhow sailors with some hot chiles or pickled citrus.

Step 4: Eat for days

Koshari’s reliance on so many shelf-stable ingredients makes it great for cooking from the pantry, but it can also make the process of preparing it daunting. Pace yourself and split the preparation over a couple of days, remembering that most grain bowl ingredients can be building blocks for multiple meals. If you’re planning a pasta dinner with a green salad on the side, make some extra tomato sauce and a garlicky vinaigrette to dress your koshari the next day. And as you well know, crispy onions make anything better.

So the next time you look to your own pantry for dinner inspiration, borrow a page from koshari’s long, global tradition of piling together sturdy nonperishables with the zingiest trimmings on hand — for a combination that has been satiating sailors, traders, street vendors, and home cooks for centuries.

Anny Gaul is a food historian, blogger, and translator. She’s currently a fellow at the Center for the Humanities at Tufts University.

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/2SZaQbK via Blogger https://ift.tt/2WQJTIt

1 note

·

View note

Quote

Anny Gaul Koshari is filling, flavorful, easy to make, and basically perfect Last September, the Egyptian fast-casual chain Zooba opened a branch in Lower Manhattan. Among Egyptian classics like taameya and hawawshi, one of the most popular dishes on the menu from the start has been koshari — a centuries-old grain bowl that’s suddenly found itself an unlikely global “it” food. Manhattan’s Zooba is just the latest in a series of hot spots in cities like Cairo, Berlin, London, and New York that are serving the ancient staple to an entirely new and very eager customer base. The appeal of koshari is easy to understand. It’s both filling and delicious — a mess of complex carbs and protein muddled with a range of acidic notes. A base of rice, lentils, chickpeas, and macaroni is shot through with sauces that meld tomato, hot pepper, vinegar, and garlic, and the whole thing is topped with crispy fried onions. But while it’s a fast-casual trend around the world, in Egypt, koshari is better known as a historic national dish, one that gracefully straddles the divide between street food and home cooking. It’s also the perfect food for pantry cooking in an age of stay-at-home orders and two-hour supermarket queues. With a long history as a hardy, adaptable, filling meal of choice among traders and travelers, it’s designed to provide maximum nutrition and flavor from cheap, accessible ingredients and local trimmings. If you have an assortment of starches, pulses, and alliums on hand, plus some vinegar and tomato sauce or tomato paste, then koshari’s delights are within your reach. “Egyptians have a long history of hodgepodge cooking, stuffing carbs with even more carbs — and we aren’t the only ones.” — Egyptian novelist Nael El Toukhy Koshari’s history has always been something of a mystery. One thing most Egyptians agree on is the dish’s connection to khichidi (sometimes spelled kitchari), an Indian dish that is also built on the winning combination of grains and pulses — a catchall term for the edible seeds of legumes like beans and lentils. But how did it get to Egypt? Most popular accounts cite Britain’s occupation of Egypt, which began in 1882 and was accomplished with the help of Indian troops. While it’s perfectly plausible, even likely, that Indian soldiers brought khichidi with them to Egypt, they probably weren’t the first or the only such link in koshari’s history: Centuries of earlier, sometimes indirect, connections between Egypt and India likely also form part of the dish’s evolution. As the powerhouse rice-and-lentils combo traveled along the pilgrimage and trade routes that have connected South Asia to Arabia to Egypt via the Red Sea for centuries, it absorbed new ingredients and flavors along the way. Today, traces of rice-and-lentil dishes dot the ports and coastal regions that long tied Egypt and India together. The crews of dhows — short-range sailing vessels of the Red Sea and Indian Ocean — once ate a dish made with rice, lentils, ghee, and hot peppers, according to one traveler’s account from the 1930s. Food scholar Sami Zubaida recalls a weekly meal of rice, lentils, tomato paste, and garlic during his childhood in Baghdad, adding that the dish was also well-known in Iraq’s port city of Basra. It was Zubaida who pointed me in the direction of several 19th-century British accounts that placed koshari — or something very like it — along the east coast of the Arabian peninsula as well as in Suez, an Egyptian port at the northernmost end of the Red Sea. An East India Company official stationed there in the 1840s described the locals eating a mixture of lentils and rice cooked with ghee and flavored with “pickled lime or stewed onions.” Zooba [Official] Two versions of the Koshari served at New York’s Zooba pre COVID-19, now available for takeout and delivery In 1941, Egypt’s most famous cookbook, known as Kitab Abla Nazira, included two koshari recipes, one with yellow lentils and one with brown lentils. But before its canonization in a cookbook written for middle-class housewives, koshari was likely best known as a local street food. British public health authorities granted a license to a street vendor peddling “rice and macaroni” in 1936. It’s a vague archival detail, but I like to think it may have referred to Cairo’s first recorded koshari cart. The addition of pasta and tomato sauce to koshari was a testament to the considerable influence of the Italian communities in Cairo and Alexandria at the time, which infused everything from the local diet to its dialect. (Modern Egyptian Arabic is peppered with Italian loanwords for everything from a Primus stove — “wabur,” from “vapore” — to the check at a restaurant, “fattura.”) Pasta and tomato sauce offered cheap ways to stretch koshari’s portions even further. Contemporary koshari is commonly served with as many as three different dressings: a tomato sauce, a local hot sauce called shatta, and a garlicky, vinegar-based dressing called da’ah (pronounced with a glottal stop in the middle, like “uh-oh”). Even today, koshari is never just one thing. Within Egypt, variations abound: Yellow lentils are associated with Alexandrian koshari, while Cairene koshari typically features brown lentils. Many home cooks told me how they’d tweak their mother’s or grandmother’s recipes, swapping in whichever pulses or pasta shapes they prefer or adding more spice. Sometimes elements of the dressings are combined, like hot pepper added to the tomato sauce, for example. There are variants topped with an egg or a smattering of chicken livers. Cairo Kitchen, another fast-casual Egyptian restaurant specializing in homestyle meals, introduced brown rice and gluten-free variations of koshari. And further afield, Koshary Lux in Berlin serves up koshari with jasmine rice, beluga lentils, and caramelized rather than fried onions. For now, the signature neon lights of Zooba’s Nolita dining room are switched off, just like the lights on the Nile party boats in Egypt they’re meant to resemble. Until they light up again (it recently opened for takeout and delivery!), the world’s original flexitarian grain bowl is easy enough to make yourself. Anny Gaul Koshari is less about one ingredient than the right mix of textures and tastes. Build-Your-Own The robust grain-and-pulse genre provides a handy template for building a grain bowl from whatever’s on hand. For some good jumping-off points, try Meera Sodha’s twist on kitchari; Maureen Abood’s take on koshari’s Levantine country cousin, mujadara; or novelist Ahdaf Soueif’s koshari recipe. But koshari doesn’t so much require a hard-and-fast recipe as it does a list of stuff to put in a bowl, and a mixture of contrasting textures and tastes is more important than any one ingredient. Here, then, is a basic guide to building your own koshari-inspired pantry grain bowl. Step 1: Form a base The foundation of the dish should include at least one grain (rice, pasta, or in a pinch, bulgar, freekeh, or even couscous) and one pulse (lentils, chickpeas). Today’s koshari typically includes at least two of each (chickpeas, lentils, rice, and pasta), but you can always keep it simple, like many earlier versions of the dish, with just rice and lentils. Aim for short pastas, such as elbow macaroni; for longer pastas like vermicelli and spaghetti, break into pieces before cooking. Most koshari recipes call for a grain-to-pulse ratio of at least 2 to 1. Increase the ratio to stretch the recipe into more servings; decrease it for a lighter meal. The culinary teams at Zooba and Cairo Kitchen suggested that preparing multiple ingredients in the same pot is the secret to rich, homestyle flavors (also fewer dishes!), so feel free to cook your lentils and rice together. Step 2: Sauce it Sauces and dressings can make or break a grain bowl. If you have a jarred marinara-style tomato sauce — ideally something with tomatoes, onion, and garlic — on hand, warm it up and stir it right into your koshari or mix in a bit of your favorite hot sauce first. If you only have tomato paste, improvise a substitute by stirring in some hot sauce and olive oil. Then you need something with a little more garlic and acid. Whip up a quick dressing with some crushed fresh garlic and cumin steeped in white vinegar (traditional) or lime juice (nouveau). You can also start with a basic citrus vinaigrette and experiment with layering other dressings on top, like a drizzle of pomegranate molasses or a balsamic glaze. A squeeze of fresh citrus never hurts. Classic koshari is topped with crispy fried onions, which you can replicate with whatever alliums you have on hand, some oil, and a microwave, one of my favorite hacks. Reserve the oil and toss it with the pulses and grains, and add a dollop of butter or ghee for even more richness. For a crunch that doesn’t involve frying things in hot oil but still feels Egyptian, try dukkah, an Egyptian seed and spice mix. Step 3: Customize From there, you can pepper in some caramelized onions or add your favorite pickles, fresh herbs, greens, or a soft-boiled egg. Follow the lead of dhow sailors with some hot chiles or pickled citrus. Step 4: Eat for days Koshari’s reliance on so many shelf-stable ingredients makes it great for cooking from the pantry, but it can also make the process of preparing it daunting. Pace yourself and split the preparation over a couple of days, remembering that most grain bowl ingredients can be building blocks for multiple meals. If you’re planning a pasta dinner with a green salad on the side, make some extra tomato sauce and a garlicky vinaigrette to dress your koshari the next day. And as you well know, crispy onions make anything better. So the next time you look to your own pantry for dinner inspiration, borrow a page from koshari’s long, global tradition of piling together sturdy nonperishables with the zingiest trimmings on hand — for a combination that has been satiating sailors, traders, street vendors, and home cooks for centuries. Anny Gaul is a food historian, blogger, and translator. She’s currently a fellow at the Center for the Humanities at Tufts University. from Eater - All https://ift.tt/2SZaQbK

http://easyfoodnetwork.blogspot.com/2020/05/this-egyptian-grain-bowl-is-pantry.html

0 notes