#buffalo bill and the indians

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

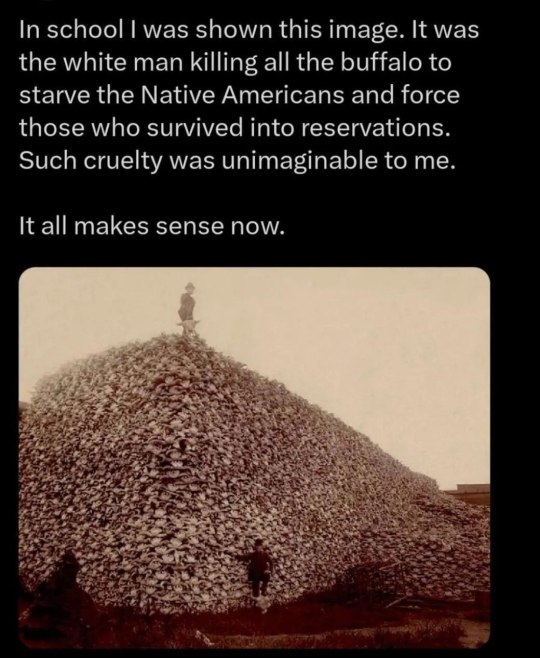

Never forget

#Never forget#buffalo#native american#nativeamericans#usa news#usa politics#usa is a terrorist state#usa#class war#history#american indian#american#america#ausgov#politas#auspol#tasgov#taspol#australia#fuck neoliberals#neoliberal capitalism#anthony albanese#albanese government#buffalo sabres#buffalo 66#buffalo bills#buffalo bisons#buffalo springfield#animalrights#animals

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

crazy thing to say when you look this fine

#63 year old smoke show#take 22#judith crist#quote#buffalo bill and the indians or sitting bull's history lesson#screencaps#1975#1970s#interview

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chief Iron Tail (1842–1916) was an Oglala Lakota Chief and star performer with 'Buffalo Bill's Wild West' show. He was one of the most famous Native American celebrities of the late 19th and early 20th centuries and notable in American history for his distinctive profile on the 'Buffalo nickel' aka 'Indian Head nickel' of 1913-38 (picture of which features on another post here).

#Chief Iron Tail#Ogala Lakota tribe#Native American#Buffalo Bill#buffalo nickel#Indian Head nickel#war bonnet#headdress

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

How many times will MLB threaten a minor league city and then walk back that threat when the deadline passes?

As I wrote about in a previous story, sports owners love to act as if they need everything, and they need it right now. Just look at Philadelphia right now. Their mayor spent months coming to an agreement with the 76ers on a new arena. Yet, while most of the agreement CONTINUES to be secret, local officials who are required to sign off on this agreement, have been given not even 3–4 weeks to…

#Ballpark Digest#Baltimore#Baltimore Orioles#Baltimore Ravens#Buffalo#Buffalo Bills#Everett AquaSox#Field Of Schemes#Global Sports Matter#Hillsboro#Kathy Hochul#Knoxville#Maryland#MiLB#Minor League Baseball#MLB#New York#NFL#Philadelphia#Philadelphia 76ers#Richmond#Richmond Flying Squirrels#Salt Lake City#San Antonio#San Antonio Current#San Antonio Missions#San Diego#San Diego Padres#Spokane#Spokane Indians Baseball Club

0 notes

Text

Marcella Ryan LeBeau is a member of the Two Kettle Band of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe and lives in Eagle Butte, South Dakota. Her Lakota name is Wigmuke Waste Win (Pretty Rainbow Woman) Her great-grandfather, Chief Joseph Four Bear (Mato Topa), signed the Fort Laramie Treaty in 1868. Her grandmother, Louise Bear Face, was related to Rain In The Face who took part in the Battle of the Little Horn.

Marcella served as a nurse in WWII becoming a 1 st Lieutenant in the Army Nurse Corps. The army service took her from the USA to Wales, England, France, and Belgium. Since receiving the French Legion of Honor Award on June 6, 2004, in Paris France, on the occasion of the 60th Anniversary of D-Day, Marcella has been requested to participate at many Veterans’ events, speaking of her military experience in World War II. Marcella served one term as District 5 council representative for the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe. She is also honored to speak to the youth at elementary, high school, and college venues when she is invited.

In 1992 and 1995 Marcella and her son, Richard went to Glasgow, Scotland with interest in the return of the Ghost Dance Shirt that was taken from Wounded Knee in 1890. After negotiations, the ghost shirt was returned by the Kelvin Grove Museum. George Craeger, with the Buffalo Bill Wild West Show, sold some artifacts to the museum and donated a Ghost Shirt. It’s now held at the Heritage Cultural Center at the South Dakota Historical Society in Pierre, South Dakota.

After retiring as the Director of Nursing from the Indian Health Service in Eagle Butte, Marcella, and her granddaughter, Bonnie opened a machine quilting shop located in Eagle Butte. They make a variety of quilts. The main feature of their shop is the star quilt frequently used by the Lakota people for honoring and naming ceremonies, memorial give-aways, etc. which are traditional of this area’s native people.

Marcella having raised a family of eight children is an advocate for the Lakota language and culture, youth, veterans, elderly, upholding treaties, and wellness.

Credit: text & photos from wisdomoftheelders.org

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chief Big Spring and Wolf Eagle (aka Buffalo Chief of the Blackfoot) stand in front of tipis ...

Date : 1930-1940

Big Spring, left, wearing war bonnet and traditional regalia, stands next to Wolf Eagle (aka Buffalo Chief of the Blackfoot) wearing buffalo horn headdress and traditional regalia. Tipis in background.Note by Dyck on verso "Big Spring Blackfoot."

Native Americans

Siksika Indians

McCracken Research Library, Buffalo Bill Center of the West

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beautiful black witch moth

The erebid moth Ascalapha odorata, commonly known as the black witch, is a large bat-shaped, dark-colored nocturnal moth, normally ranging from the southern United States to Brazil. Ascalapha odorata is also migratory into Canada and most states of United States. It is the largest noctuoid in the continental United States. In the folklore of many Central American cultures, it is associated with death or misfortune.

Female moths can attain a wingspan of 24 cm. The dorsal surfaces of their wings are mottled brown with hints of iridescent purple and pink, and, in females, crossed by a white bar. The diagnostic marking is a small spot on each forewing shaped like a number nine or a comma. This spot is often green with orange highlights. Males are somewhat smaller, reaching 12 cm in width, darker in color and lacking the white bar crossing the wings. The larva is a large caterpillar up to 7 cm in length with intricate patterns of black and greenish-brown spots and stripes.

The black witch lives from the southern United States, Mexico and Central America to Brazil, and has apparently been introduced to Hawaii.[citation needed]

The black witch flies north during late spring and summer. One was caught during an owl banding project at the Whitefish Point lighthouse on the shoreline of Lake Superior in July 2020.[citation needed]

The black witch is considered a harbinger of death in Mexican and Caribbean folklore. In many cultures, one of these moths flying into the house is considered bad luck: e.g., in Mexico, when there is sickness in a house and this moth enters, it is believed the sick person will die, though a variation on this theme (in the lower Rio Grande Valley, Texas) is that death only occurs if the moth flies in and visits all four corners of one's house (in Mesoamerica, from the pre-Hispanic era until the present time, moths have been associated with death and the number four). In some parts of Mexico, people joke that if one flies over someone's head, the person will lose his hair.

In Jamaica, under the name duppy bat, the black witch is seen as the embodiment of a lost soul or a soul not at rest. In Jamaican English, the word duppy is associated with malevolent spirits returning to inflict harm upon the living and bat refers to anything other than a bird that flies. The word "duppy" (also: "duppie") is also used in other West Indian countries, generally meaning "ghost".

In Brazil it is called "mariposa-bruxa", "mariposa-negra", "bruxa-negra", and "bruxa", and it is also believed that when a moth of this type enters the house it can bring some "bad omen", signaling the death of a resident. In the Ecuadorian highlands they are called Tandacuchi and in Peru Taparacuy or Taparaco. These countries share the belief that if this moth, a messenger of death, appears in your home, someone will die very soon.

In Hawaii, black witch mythology, though associated with death, has a happier note in that if a loved one has just died, the moth is an embodiment of the person's soul returning to say goodbye. In the Bahamas, where they are locally known as money moths or money bats, the legend is that if they land on you, you will come into money, and similarly, in South Texas, if a black witch lands above your door and stays there for a while, you will supposedly win the lottery.

In Paraguay and Argentina, this insect is mostly known as "ura", and there is a popular belief that this moth urinates and leaves worms on the skin of people and animals. However, the insect that lays eggs in the skin and whose larvae become embedded in the flesh is the colmoyote or screwworm (Dermatobia hominis).

In Spanish, the black witch is known as "mariposa de la muerte". Other names for the moth include the papillion-devil, la sorcière noire, the mourning moth or the sorrow moth.[citation needed]

Black witch moth pupae were placed in the mouths of victims of serial killer 'Buffalo Bill' in the novel The Silence of the Lambs. In the movie adaptation, they were replaced by death's-head hawkmoth pupae.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

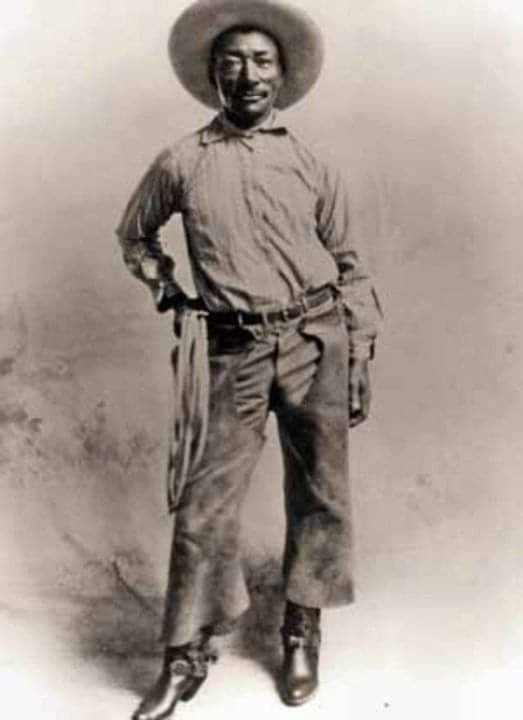

Today we venerate Ancestor Nat Love aka Red River Dick aka Deadwood Dick on the day that we recognize his169th birthday 🎉

A permanent fixture of the American West, Nat Love led the life of legends & became a hero to the peoples of the TX, AZ, TN, & Dakotas territories.

Nat Love was born enslaved with his family in Davidson County Tennessee in 1856. He was raised in a log cabin during the turbulent years of the Civil War & its transition into the Reconstruction Era; where his father taught him how to read & write - a rarity of the time. After the Civil War, Nat & his father worked on the plantation farm as sharecroppers until his death shortly thereafter.

Nat Love's superior talent of breaking horses swept him off to the American West. He worked as a cattle/horse-driver throughout the Texas Panhandle, Kansas, Arizona Territory & the Dakota Territory. Here, his exploits began - with him fighting off cattle thieves who trained as marksmen. His journey led him to cross paths with local western legends in Arizona where he earned the title of "Deadwood Dick" after competing as a rodeo contestant in Deadwood, South Dakota & winning countless competitions in throwing, roping, tying, bridling, saddling, & bronco riding.

Nat Love later released his autobiography entitled, "The Life and Adventures of Nat Love Better Known in the Cattle Country as “Deadwood Dick.”, in which he shared his exploits as a legendary cowboy & star rodeo performer. How he had once endured extensive bullet wounds in a fight & was captured by Pima Indians, nursed back to health, then welcomed by Chief Yellow Dog into tribe & later betrothed to Chief's daughter until he escaped on a stolen pony & road back out into West Texas. He recounted how he earned the nickname, “Deadwood Dick” along with the love/respect of the good citizens of Deadwood, Dakota Territory. And how he met legendary cowboys like, “Buffalo Bill” Cody. Since there are no records of the cattlemen that claimed to have worked with/for, no one will ever know how fact or fictional the wildly outrageous accounts of Nat Love truly were. Yet and still, he'll always remain a undying fixture of the American West post-Maafa.

"Mounted on my favorite horse, my… lariat near my hand, and my trusty guns in my belt… I felt I could defy the world. — from "The Life and Adventures of Nat Love"

We pour libations & give him💐 today as we celebrate him for his unbridled courage & asserting our rightful place among the true cowboys/gals of the wild wild west.

Offering suggestions: cowboy caviar, libations of whiskey, & read/share his autobiography

#the hoodoo calendar#hudu#hoodoo#ancestor veneration#nat love#red river dick#deadwood dick#wildwildwest#cowboys#black cowboys#wild west

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

Early Non-Native Accounts of Bigfoot in North America

There are many accounts of Native American encounters with Bigfoot recorded in history. However, European settlers and their descendants also had Bigfoot experiences. Here are some that occurred before the Bigfoot craze in the 1950s popularized the idea.

A white woman named Rachel Plummer, who was taken captive by a Comanche raiding band in Texas in the year 1836, is credited with making one of the earliest and most prominent references to Bigfoot by a non-Native American. After the Comanche set Plummer free in 1838, she wrote and published a narrative detailing her traumatic experience as a captive. She went into enormous detail about the creatures that lived in the prairies, in addition to providing specifics about their everyday lives and the roles that men, women, and children had in their lives. Among these animals were wolf packs, bears, elk, and even what her captors referred to as "man-tigers."

According to what she reported, "The Indians claim that they have discovered several of them in the mountains." They say, "They describe them as having the characteristics and proportions of a man." People report that they walk upright and stand between eight and nine feet tall. It was not until nearly a century later that five gold prospectors in Oregon documented the existence of a beast that was very similar to the one described. The men, venturing into the wilderness in 1924, claimed that an "ape man" had accosted one of their party members, Fred Beck, earlier that day, and had shot the creature, inflicting injuries as he fled. Later that night, a larger group of these animals battered the prospectors' hut with rocks and boulders. The men were certain that they were exacting their vengeance for the previous shooting that had taken place. The animals attempted to smash down the door of the cabin, but fortunately, the guys were able to delay their progress.

As soon as the sun began to rise, the apemen fled, and the five terrified prospectors made their way to the closest settlement. It was believed to such an extent that the United States Forest Service initiated an investigation and dispatched two rangers back into the forest with Beck to see if they could find any evidence of the beasts or even the beasts themselves. Despite the lack of evidence, the story quickly spread throughout the Western region, leading to the continued use of Ape Canyon as the name of the alleged attack site. Buffalo Bill and Daniel Boone, two of the most famous frontier folk heroes in the United States, have legends about Bigfoot in their backs. The Pawnee Indians of the Plains presented Buffalo Bill with a gigantic thigh bone as a gift, as described in his book, The Life of Honorable William F. Cody. Buffalo Bill also mentions this experience. According to their assertions, the bone belonged to "a race of man... whose size was approximately three times that of an ordinary man."

Daniel Boone's account went one step further when he told a story about how he shot and killed a "hairy giant" that was ten feet tall in Kentucky. He referred to the beast as a "Yahoo," which is a reference to the brutes that resembled humans that appeared in Jonathan Swift's classic novel Gulliver's Travels. As a result of the 1950s discovery of footprints in Bluff Creek, California, the search for Bigfoot experienced a surge in popularity. These tracks were believed to be the creature's. In the hopes of discovering some evidence that Bigfoot does in fact exist, a large number of people, including cryptozoologists, scientists, adventurers, and other Bigfoot fans, traveled to various regions in the state of Washington and Northern California. Despite the lack of conclusive evidence, people maintained their belief in the existence of a hominid that had been absent from human history for a significant period.

#buffalo bill#teddy roosevelt#comanche#daniel boone#bigfoot#sasquatch#north american cryptid#cryptids#cryptozoology#bigfoot art

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

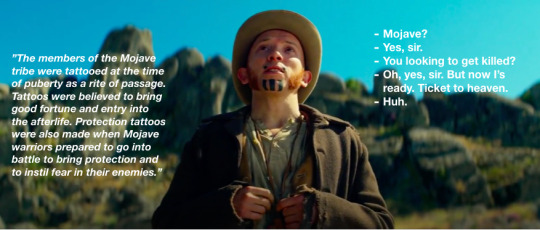

I've noticed this about you – Trying to pick up and understand things referenced in The English, pt. 1/2

So, I just watched Amazon's new miniseries The English at the beginning of this year, and while enjoying the it immensely I couldn't help but to notice that, besides historical facts and details, there were undercurrents in it that I just wasn't getting. I decided to do some research and came across pretty interesting things. Lots of thought has went into the making of this series. I've divided my findings in two parts. This first part is about general stuff.

Eli's a member of the Skiri/Skidi-Federation, one of the four bands (or groups) of the Pawnee people. Also known as the Wolf Pawnee or Loups, the Skiri used to live along the Loup and Platte river areas in Nebraska. The Skiri use a different dialect of Pawnee than the three southern bands (South band and Skiri differ mainly in pronunciation and vocabulary), but Pawnee speakers don't have trouble understanding each other. Eli's Pawnee name Ckirirahpiks is pronounced [tskirira:hpiks]. Ckirir means 'wolf' and rahpiks 'scarred.'

Recruitment of Indian scouts was first authorized in 1866 by an act of Congress. Between 1864 and 1877, 170 Pawnee men served in the "Pawnee Battalion" under Frank North (1840–1885) who had learned the Pawnee language after moving to Nebraska at the age of 16. (Interestingly, in 1882 North joined Buffalo Bill's Wild West as a manager of the American Indians.) Indian Scouts were officially deactivated in 1947 when their last member retired.

I found pictures of Pawnee scouts from 1870s in this blog post. These three pictures, taken by William Henry Jackson, were particularly interesting because you can clearly see that details of their appearance have been used as an inspiration when creating Eli's looks.

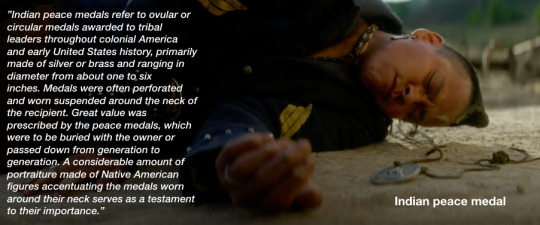

When rewatching the show I noticed that Eli was wearing an Indian peace medal. According to Trooper Charlie White, Eli was known for his heroic exploits while in the army, but - given Eli's brush off - I wonder if Eli's medal had been something he had inherited. Had his father been a chief? Still, among William Jackson's pictures there were Pawnee scouts with peace medals hanging around their necks. A Pawnee scout called Co-Rux-Te-Chod-Ish was the first Native American to receive the Medal of Honor.

Raise your hand if you really thought that Richard Watts had managed to get his hands on freshwater oysters. Perhaps this was yet another case of him "spitting in the soup."

I was super confused when Simon the squeezebox player reappeared in the last episode since I had completely forgotten about him, but I loved the colours in this scene.

"I've noticed this about you. You keep saying these negative things and you end up always doing the opposite." "Hmm, well... Maybe I should start listening to myself."

So apparently even women who have never given birth can breastfeed babies. To induce lactation you need to stimulate breasts 10–15 minutes several times a day and milk will start after a month or so. Also, of course a 'breast' would be an English word Eli couldn't have picked up naturally.

Although hunting was also an integral part of the subsistence pattern, horticulture - particularly corn - occupied a preeminent position in Pawnee life. It not only provided their sustenance but also figured prominently in their religious life.

At the beginning of the 19th century the Pawnee lived earth lodges which were large, dome-shaped structures of wood covered with packed sod and earth and had a long, narrow, covered entryway. The sizes of lodges varied in diameter from 8 to 15 metres and generally contained several families. Historical sources give varying numbers of Skiri villages, ranging from 13 to 18. Each village had its own separate identity through religious functions, but by the mid-19th century the importance of village identity began to fade as the Skiri population rapidly diminished. (Murie, J. R. and Parks, D. R. (1981) Ceremonies of the Pawnee.)

As the 19th century progressed, the Pawnee bands were forced together onto a reservation on the north side of the Platte and were treated as a single tribal entity by the United States government. Missionaries and the government worked steadily at "making white men"of the Pawnee. By 1873 because of disease, crop failure, warfare, and government rations policy, the Pawnee population had decreased to approximately 2,400. In 1875 the Pawnee were persuaded to give up their reservation in Nebraska and move to new one in the Indian Territory. By the 1876 the entire tribe had removed there, where efforts to acculturate them continued. By 1890 most of the Skiri Pawnee lived on individual farms, dressed like contemporary whites, and spoke English. (Murie, & Parks, 1981)

Bundles were an integral part of Pawnee religion and served as shrines. Among the Skiri, there were two general types of bundles. Sacred bundles, cuharîpîru, were village and band bundles and naturally more important. The oldest sacred bundle was the Evening Star bundle. The other type was referred as karûsu, a bag/sack, and was any lesser bundle – that of a warrior, a doctor, or any other individual.

I was curious about the skull in Eli's bag and using skullsite.com and Royal BC Museum's bird bone identification guide I was able to identify it. Given that Pawnee villages used to be located along rivers, it not surprising that that the skull Eli treasured would belong to an osprey aka fish hawk.

Ospreys differ from most hawks by having short prefrontals.

Round and almost circular nasal (nostril).

Has perforation in sheet of bone between eyes.

Particularly curved bill.

Frontal’s width stays even.

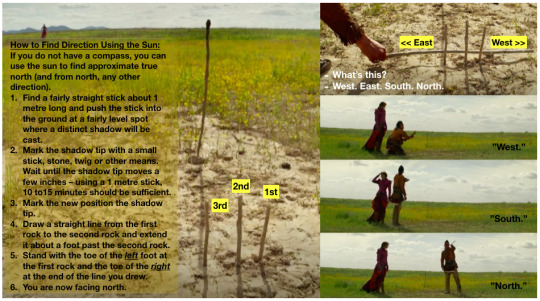

I always like it when a show makes me curious and inspires me to learn something new, in this case to determine cardinal directions using the sun. I used the instructions in this post to make the collage of Eli determining the compass points.

#the english 2022#the english#pawnee scouts#indian peace medal#cornelia used 'please.' it's super effective.#the bird skull in eli's bundle#compass points#eli whipp

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

Top Fossil Fuel Ad Ban Critic Runs Group That Got $450K from Oil Company

"Buffalo, a member of the Samson Cree Nation, called Bill C-372 the 'most egregious attack on civil liberties in recent Canadian history' and 'a direct assault on Indigenous peoples.' He compared it to the Indian Act of 1876".

"His column ricocheted across the internet, where it was shared or referenced by industry groups, conservative columnists and rightwing politicians, including federal Conservative Party leader Pierre Poilievre".

"But Buffalo is not a disinterested player in this debate. He is president and CEO of the Indian Resource Council, an Alberta-based group that in recent years has quietly received $450,000 in contributions from Canadian Natural Resources Ltd. (CNRL), one of the country’s top oil and gas producers".

"'I definitely respect his right as an Indigenous person to have his own perspective,' Tara Marsden, sustainability director for the Wilp, or house clans, of the Gitanyow Hereditary Chiefs, said of Buffalo. 'But he’s just one perspective'".

The bill in question can be read here: https://www.parl.ca/DocumentViewer/en/44-1/bill/C-372/first-reading. Information about it's progression through the House of Commons is available here: https://www.parl.ca/LegisInfo/en/bill/44-1/C-372.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the past two years Glasgow has become the first UK museum to repatriate objects to India. Newcastle and the Horniman in south London followed an example set by Aberdeen and Cambridge by returning looted Benin bronzes to Nigeria. Exeter handed sacred regalia to the Siksika Nation in Canada. Oxford returned the remains of 18 indigenous people to Australia.

Earlier this month Manchester completed a landmark return of 174 objects to the to the Anindilyakwa community, who live on an archipelago in the Gulf of Carpentaria, off the northern coast of Australia.

The scale of repatriation – or rematriation as it was proudly labelled by a Scottish national museum returning a totem pole to Canada – is unprecedented but missing from all this, campaigners say, are the nation’s London-based national museums who look increasingly isolated.

“Regional museums are so far ahead of national institutions,” said Lewis McNaught, who runs the not-for-profit Returning Heritage project.

“It has been led by Glasgow and it really just remains for national collections to wake up to the trend which is, actually, now global. The UK is really falling behind quite dramatically.”

Dan Hicks, a professor of contemporary archaeology at Oxford University as well as curator at the city’s Pitt Rivers Museum, said repatriation has become part of the “fake culture wars” with some on the right seeing it as “wokery”.

“What that means, sadly, for our national institutions is that they are being forced into a position of inertia and making themselves increasingly irrelevant with every week that goes by and every restitution that we see from the regions and elsewhere around the world.

“Everyone else is getting on with it.”

The big reasons for the two different narratives is that the London-based national museums are hamstrung by legislation.

The British Museum Act 1963 specifically forbids the museum from disposing of its holdings. The National Heritage Act of 1983 prevents trustees of institutions, including the V&A, Science Museum and others, from deaccessioning objects unless they are duplicates or beyond repair.

Regional museums, whether they are run by local authorities, universities or are regimental museums or private, don’t have the same issue.

But the picture is more complicated, said Hicks, and repatriation is also not a new issue or debate.

“There is a deep and long history to restitution in this country. Edinburgh university was returning human remains two generations ago, never mind one generation … there are scores if not hundreds of stories over the past 40 to 50 years.

“It should be part of what museums do. It’s a part of the job.”

Glasgow is seen as a leader in the repatriation conversation since an agreement in 1998 to return a Sioux warrior shirt acquired at the end of the 19th century from Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show.

The return of the Lakota Sacred Ghost Dance Shirt to the Wounded Knee Survivors’ Association established criteria that have been widely adopted in the museum sector.

Duncan Dornan, the head of museums and collections at Glasgow Life, said repatriation should be seen as a two way process and recalled the joy at the signing ceremony last year for the repatriation of artefacts to India.

“It was a very emotional event and Glaswegians of Indian heritage were very emotional. Their response was that they were very proud of their city.

“We see repatriation as establishing a relationship of equals and emphasising Glasgow as an outward-looking modern city.

“This is about a 21st-century relationship rather than a historic relationship.”

The recent Manchester Museum return of objects was seen as important because they were not giving back things that had been looted. They were everyday objects, including dolls made from shells, baskets and boomerangs.

“We believe this is the future of museums,” said Esme Ward, the director of Manchester Museum. “This is how we should be.”

Unesco hopes that Manchester will be a model for other museums to follow. Krista Pikkat, Unesco’s director for culture and emergencies, said: “It is a truly historic and moving moment. This is a case we have shared with our member states because we felt it was exemplary in many ways.”

The UK government has no plans to change the law that could then lead to movement in some of the most high-profile repatriation debates such as the Parthenon marbles and the Benin bronzes.

Campaigners say the UK is looking increasingly isolated and there is a growing movement for a change in the law.

Lord Vaizey, a former long-serving Conservative arts minister, has said the 1983 act “makes it almost impossible for UK museums to establish themselves as outward-looking, modern institutions fit for purpose in the 21st century”.

There are ways of getting around it. The V&A announced last year that it was returning the Head of Eros, a life-sized marble carving dating back to the 3rd century AD, to Turkey to be reattached to the famous Sidamara sarcophagus.

It made good a promise made by the British government in 1934 but the return is essentially a long-term loan, not an unconditional return.

Across the world, from the US to France to Germany and the Vatican, countries are repatriating objects. “Almost everywhere you look, items are being returned,” said McNaught.

In July, for example, the Netherlands repatriated nearly 500 looted objects to Sri Lanka and Indonesia.

The objects going to Sri Lanka include the famous and fabulous ruby-inlaid Cannon of Kandy dating from 1745, one of six objects from the Rijkmuseum that represented the very first return of colonial items from the museum’s collection.

The Vatican has also voiced willingness to return indigenous artefacts. “The seventh commandment comes to mind: If you steal something you have to give it back,” Pope Francis said in April.

The London-based national museums are undoubtedly hamstrung by law but that does not stop the regular calls for the return of objects.

Some cases are indisputable, say campaigners.

McNaught pointed to Ethiopian tabots that have been in the British Museum’s stores for more than 150 years.

The wood and stone tabots are altar tablets, considered by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church as the dwelling place of God on Earth and the representation of the Ark of the Covenant.

“They have never been exhibited and they never will,” said McNaught. “They have never been studied. They have never been photographed. The only people who can release these items are trustees and they can’t see them either.

“So if you are a trustee and you say, ‘Let me see what all the fuss is about,’ then you can’t.”

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Burt Lancaster in Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull's History Lesson, Copyright 1976, United Artists.

#i love a UA copyright on a BL photo 🫵 he MADE you#buffalo bill and the indians or sitting bull's history lesson#1976#1970s#stills

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portrait of Shar-I-Tar-Ish

Artist: Henry Inman (American, 1801–1846)

Date: 1832

Medium: Oil on Canvas

Collection: Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming

Information

Between 1821 and 1828, Thomas L. McKenney, the Superintendent of Indian Affairs, commissioned portraits of hundreds of American Indian leaders on diplomatic missions to Washington, D.C. Painted first by Charles Bird King and later duplicated by Henry Inman, these portraits were intended to serve as a “National Indian Gallery.” Over 120 were reproduced in McKenney’s three-volume portfolio, History of the Indian Tribes of North America.

Shar-I-Tar-Ish, a Pawnee chief, visited Washington, D.C. in 1821.

#portrait#american indian leader#american culture#american native#henry inman#american art#19th century painting#american painter#american history

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

In summer 1876, the US was preparing elaborate centennial celebrations to display its industrial might, continental reach, and hard-won national unity. But a few days before the July 4th grand finale, disquieting news arrived from the northern Great Plains: the Lakota and their Cheyenne and Arapaho allies had anhilated Custer's Seventh Cavalry, more than two hundred soldiers, in the Little Bighorn Valley in Montana. From then on, American attention was absorbed by the campaign against the Lakotas, which did not end until 1890 at the horror of Wounded Knee. By that point, Lakotas were fixed in the national consciousness as the 'noble and doomed savages' of Buffalo Bill's hugely successful Wild West Show. They become multipurpose icons, immensely useful and marketable as the sounding board of America's shifting feelings of awe, terror, and remorse toward Native American's and their fate. Fictionalized beyond recognition, Sitting Bull's ever-malleable stage lakotas came to symbolize all Indians of the Great Plains, then of the West, then of all of North America, while the other Indian nations were pushed to the margins of collective memory.

-The Comanche Empire, by Pekka Hamalainen

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bill Pickett (ca 1870-1932), African American Cowboy inventor of "bulldogging," a rodeo technique to wrestle a steer to the ground.

From 1905 to 1931, the Miller brothers' 101 Ranch Wild West Show was one of the great shows in the tradition begun by William F. "Buffalo Bill" Cody in 1883. The 101 Ranch Show introduced bulldogging (steer wrestling), an exciting rodeo event invented by Bill Pickett, one of the show's stars.

Riding his horse, Spradley, Pickett came alongside a Longhorn steer, dropped to the steer's head, twisted its head toward the sky, and bit its upper lip to get full control. Cowdogs of the Bulldog breed were known to bite the lips of cattle to subdue them. That's how Pickett's technique got the name "bulldogging." As the event became more popular among rodeo cowboys, the lip biting became increasingly less popular until it disappeared from steer wrestling altogether. Bill Pickett, however, became an immortal rodeo cowboy, and his fame has grown since his death.

He died in 1932 as a result of injuries received from working horses at the 101 Ranch. His grave is on what is left of the 101 Ranch property near Ponca City, Oklahoma. Pickett was inducted into the National Rodeo Hall of Fame in 1972 for his contribution to the sport.

Bill Pickett was the second of thirteen children born to Thomas Jefferson and Mary Virginia Elizabeth (Gilbert) Pickett, both of whom were former slaves. He began his career as a cowboy after completing the fifth grade. Bill soon began giving exhibitions of his roping, riding and bulldogging skills, passing a hat for donations.

By 1888, his family had moved to Taylor, Texas, and Bill performed in the town's first fair that year. He and his brothers started a horse-breaking business in Taylor, and Bill was a member of the national guard and a deacon of the Baptist church. In December 1890, Bill married Maggie Turner.

Known by the nicknames "The Dusky Demon" and "The Bull-Dogger," Pickett gave exhibitions in Texas and throughout the West. His performance in 1904 at the Cheyenne Frontier Days (America's best-known rodeo) was considered extraordinary and spectacular. He signed on with the 101 Ranch show in 1905, becoming a full-time ranch employee in 1907. The next year, he moved his wife and children to Oklahoma.

He later performed in the U.S., Canada, Mexico, South America, and England, and became the first black cowboy movie star. Had he not been banned from competing with white rodeo contestants, Pickett might have become one of the greatest record-setters in his sport. He was often identified as an Indian, or some other ethnic background other than black, to be allowed to compete.

Bill Pickett died April 2, 1932, after being kicked in the head by a horse. Famed humorist Will Rogers announced the funeral of his friend on his radio show. In 1989, years after being honored by the National Rodeo Hall of Fame, Pickett was inducted into the Prorodeo Hall of Fame and Museum of the American Cowboy at Colorado Springs, Colorado. A 1994 U.S. postage stamp meant to honor Pickett accidentally showed one of his brothers.

#Bill Pickett#african american#cowboy#inventor#of#bulldogging#rodeo#technique#very talented#read about him#reading is fundamental#black history#knowledge is power

25 notes

·

View notes