#bretagne folklore

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

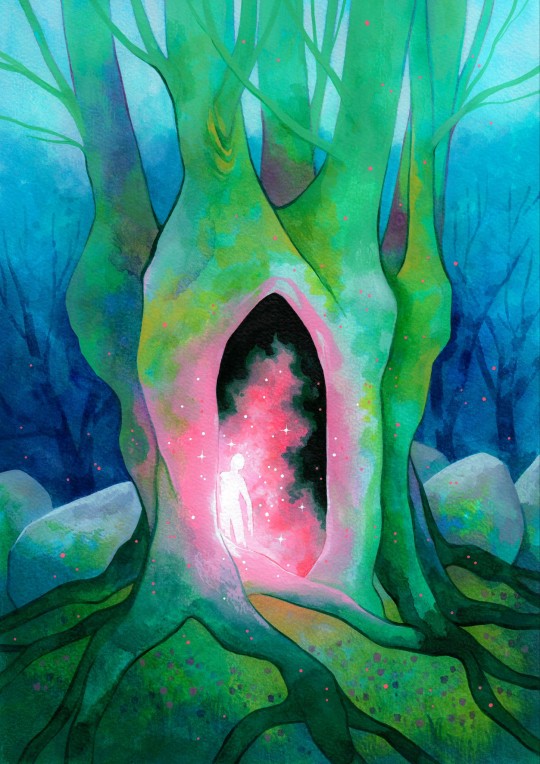

Korrigan.

#art#my art#artwork#my artwork#traditional art#artists on tumblr#illustration#paint#painting#draw#drawing#watercolor#watercolour#gouache#markers#fantasy ambient#fantasy#dark fantasy#folklore#legend#bretagne#december#colorful

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

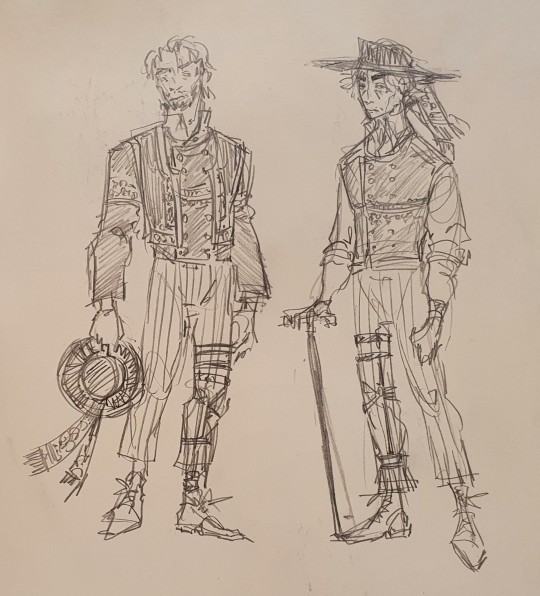

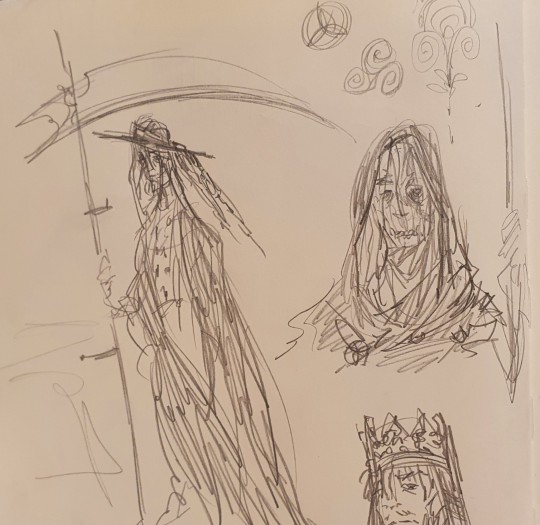

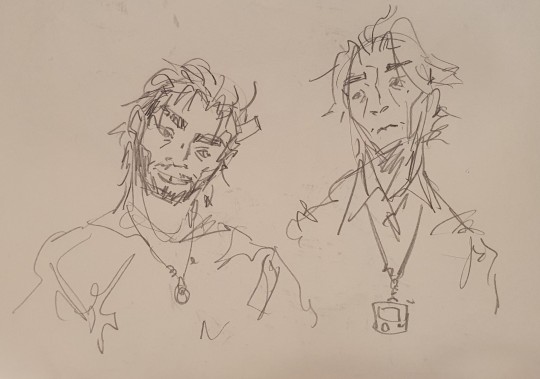

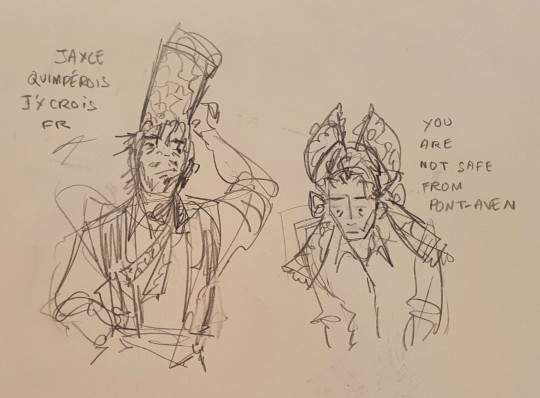

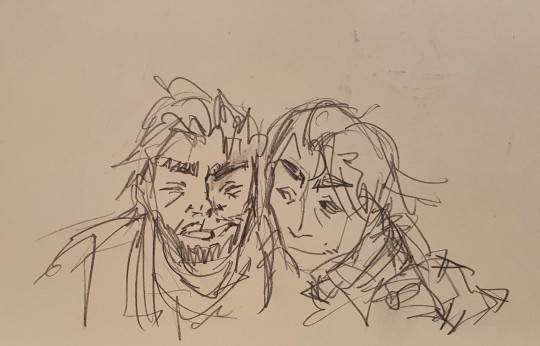

May I present Jayvik but Bretagne because its my culture and I get to do whatever I want

(I lost it)

#my art#arcane#jayvik#traditional art#sketch#sketchbook#jayce talis#jayce arcane#viktor#viktor arcane#bretagne#brittany#celt#celtic#viktor is l'ankou wich is death in our folklore and Jayce is king Gradlon wich is very important to me#jayce to me is a crêpe making machine and can go at it for hours on end during family dinners

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

#evariste-vital luminais#la fuite du roi gradlon#1884#art#painting#painter#bretagne#breton#breizh#brittany#celtic#legend#legandary#ys#finistère#douarnenez#france#french#xix century#folklore#history#culture#europe#european#ocean

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Légendes rustiques by George Sand, completed English translation

Original French at Project Gutenberg

Les Légendes rustiques is a collection of twelve creepy French folk legends gathered up and written down by George Sand and illustrated by her son, Maurice Sand, published in 1858. These stories were collected in the Berry region, but there are connections made to legends from Brittany and Normandy as well.

I came across a mention of the Rustic Legends a few years ago and realized there was no official English translation available, despite that George Sand is a very famous author. It turns out, Sand was such a prolific writer that much of her work has never been translated into English. I ordered a "translation" from Amazon and was disappointed to find that someone had just run the text through translation software without any editing or providing any cultural context. It was unreadable and I threw it in the trash.

I asked some fandom friends if they would be interested in trying to translate all twelve legends into English on our own. It has been a few years and each story has had several revisions and rounds of editing. This was a challenging translation project - there are many words in archaic French or not in French at all. Thanks to everyone who helped - I am really proud of the results here.

The purpose of this project is simply to make these twelve legends accesible to an English-reading audience. They have been available in the original French at Project Gutenberg for a long time. Use this post as a table of contents - each line will take you to a new story published on Tumblr. Sometimes they are creepy, they are often funny, and Sand's rambling style is cozy, making you feel like she is sitting right across a candle from you, telling you a story she once heard from someone else, a long time ago. Enjoy!

Introduction

1. Les Pierres-Sottes

2. Les Demoiselles

3. Les Laveuses de nuit

4. La Grand’Bête

5. Les Trois Hommes de Pierre

6. Le Follet d’Ep-Nell

7. Le Casseu’ de Bois

8. Le Meneu’ de Loups

9. Le Lupeux

10. Le Moine des Étangs-Brisses

11. Les Flambettes

12. Lubins et Lupins

#légendes rustiques#george sand#maurice sand#french literature#in translation#folklore#rustic legends#french folklore#translation project#bretagne#brittany#normandie#normandy#berry

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

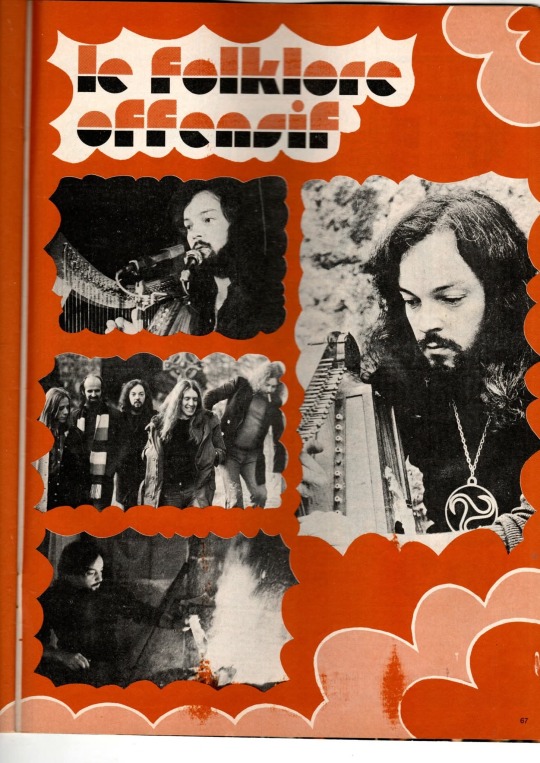

Folklore Offensif - Alan Stivell

#folk#folk music#celtic music#trad music#alan stivell#breizh#bzh#trad#musique bretonne#bretagne#musique folk#musique traditionnelle#musique#celtique#celtic#folklore offensif#70's

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Branch of Gorse and two Stonechats

Gorse brightens the Breton winter, so it has became a symbol of the region (where I come from). In Scotland it abounds in the heathland and on the coast where I live, its yellow flowers announce spring.

This is just a little gouache painting to celebrate these small sun-coloured flowers.

#Gorse#ajonc#Gorse flower#Bretagne#brittany#wildlife painting#gouache painting#folklore inspired#winter flowers

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arthurian myth: Morgan the Fey (1)

Loosely translated from the French article "Morgane", written by Philippe Walter, for the Dictionary of Feminine Myths (Le Dictionnaire des Mythes Féminins)

MORGANE

Morgane means in Celtic language “born from the sea” (mori-genos). This character is as such, by her origins, part of the numerous sea-creatures of mythologies. A Britton word of the 9th century, “mormorain”, means “maiden of the sea/ sea-virgin”, et in old texts it is equated with the Latin “siren”. A passage of the life of saint Tugdual of Tréguiers (written in 1060) tells of ow a young man of great beauty named Guengal was taken away under the sea by “women of the sea”. The Celtic beliefs knew many various water-fairies with often deadly embraces – and Morgane was one among the many sirens, mermaids, mary morgand and “morverc’h” (sea girls/daughters of the sea).

Morgane, the fairy of Arthurian tales, is the descendant of the mythical figures of the Mother-Goddesses who, for the Celts, embodied on one side sovereignty, royalty and war, and on the other fecundity and maternity. In the Middle-Ages, they were renamed “fairies” – but through this word it tried to translate a permanent power of metamorphosis and an unbreakable link to the Otherworld, as well as a dreaded ability to influence human fate. The French word “fée” comes from the neutral plural “fata”, itself from the Latin word “fatum”, meaning “fate”.

There is not a figure more ambivalent in Celtic mythology – and especially in the Arthurian legends – than Morgane. She constantly hesitates between the character of a good fairy who offers helpful gifts to those she protects ; and a terrible, bloodthirsty goddess out for revenge, only sowing death and destruction everywhere she goes. Christianity played a key role in the demonization of this figure embodying an inescapable fate, thus contradicting the Christian view of mankind’s free will.

I/ The sovereign goddess of war

It is in the ancient mythological Irish texts that the goddess later known as Morgane appears. The adventures of the warrior Cuchulainn (the “Irish Achilles”) with the war-goddess Morrigan are a major theme of the epic cycle of Ireland. The Morrigan (a name which probably means “great queen”) is also called “Bodb Catha” (the rook of battles). It is under the shape of a rook (among many other metamorphosis) that she appears to Cuchulainn to pronounce the magical words that will cause the hero’s death.

The Irish goddesses of war were in reality three sisters: Bodb, Macha and Morrigan, but it is very likely that these three names all designated the same divinity, a triple goddess rather than three distinct characters. This maleficent goddess was known to cause an epileptic fury among the warriors she wanted to cause the death of. The name of Bodb, which ended up meaning “rook”, originally had the sense of “fury” and “violence”, and it designated a goddess represented by a rook. The Irish texts explain that her sisters, Macha and Morrigan, were also known to cause the doom of entire armies by taking the shape of birds. Every great battle and every great massacre were preceded by their sinister cries, which usually announced the death of a prominent figure.

The Celtic goddesses of war have as such a function similar to the one of the Norse Walkyries, who flew over the battlefield in the shape of swans, or the Greek Keres. The deadly nature of these goddesses resides in the fact that they doom some warriors to madness with their terrifying screams. One of the effects of this goddess-caused madness was a “mad lunacy”, the “geltacht”, which affected as much the body as the mind. During a battle in 1722 it was said that the goddess appeared above king Ferhal in the shape of a sharp-beaked, red-mouth bird, and as she croaked nine men fell prey to madness. The poem of “Cath Finntragha” also tells of the defeat of a king suffering from this illness. The place of his curse later became a place of pilgrimage for all the lunatics in hope of healing.

The link between the war-goddess and the “lunacy-madness” are found back within folklore, in which fairies, in the shape of birds, regularly attack children and inflict them nervous illnesses. These fairies could also appear as “sickness-demons”. Their appearance was sometimes tied to key dates within the Celtic calendar, such as Halloween, which corresponded to the Irish and pre-Christian celebration of Samain. Folktales also keep this particularly by placing the ritualistic appearances of witches and of fate-fairies during the Twelve Days, between Christmas and the Epiphany – another period similar to the Celtic Halloween. Morgane seems to belong to this category of “seasonal visitors”.

II) The Queen of Avalon

In Arthurian literature, Morgane rules over the island of Avalon, a name which means the Island of Apples (the apple is called “aval” in Briton, “afal” in Welsh and “Apfel” in German). Just like the golden apples of the Garden of the Hesperids, in Celtic beliefs this fruit symbolizes immortality and belongs to the Otherworld, a land of eternal youth. It is also associated with revelations, magic and science – all the attributes that Morgane has. Her kingdom of Avalon is one of the possible localizations of the Celtic paradise – it is the place that the Irish called “sid”, the “sedos” (seat) of the gods, their dwelling, but at the same time a place of peace beyond the sea. Avalon is also called the Fortunate Isle (L’Île Fortunée) because of the miraculous prosperity of its soil where everything grows at an abnormal rate. As such, agriculture does not exist there since nature produces by itself everything, without the intervention of mankind.

It is within this island that the fairy leads those she protects, especially her half-brother Arthur after the twilight of the Arthurian world. Morgane acts as such as the mediator between the world of the living and the fabulous Celtic Otherworld. Like all the fairies, she never stops going back and forth between the two worlds. Morgane is the ideal ferrywoman. The same way the Morrigan fed on corpses or the Valkyries favored warriors dead in battle, Morgane also welcomes the soul of the dead that she keeps by her side for all of eternity. Some texts gave her a home called “Montgibel”, which is confused with the Italian Etna. The Otherworld over which she rules doesn’t seem, as such, to be fully maritime.

The ”Life of Merlin” of the Welsh clerk Geoffroy of Monmouth teaches us that Morgan has eight sisters: Moronoe, Mazoe, Gliten, Glitonea, Gliton, Thiten, Tytonoe, and Thiton. Nine sisters in total which can be divided in three groups of three, connected by one shared first letter (M, G, T). In Adam de la Halle’s “Jeu de la feuillée”, she appears with two female companions (Arsile and Maglore), forming a female trinity. As such, she rebuilds the primitive triad of the sovereign-goddesses, these mother-goddesses that the inscriptions of Antiquity called the “Matres” or “Matronae”. In this triad, Morgane is the most prominent member. She is the effective ruler of Avalon, since it was said that she taught the art of divination to her sisters, an art she herself learned from Merlin of which she was the pupil. She knows the secret of medicinal herbs, and the art of healing, she knows how to shape-shift and how to fly in the air. Her healing abilities give her in some Arthurian works a benevolent function, for example within the various romans of Chrétien de Troyes. She usually appears right on time to heal a wounded knight: she is the one that gave a balm to Yvain, the Knight of the Lion, to heal his madness. In these works, Morgane does not embody a force of destruction, but on the contrary she protects the happy endings and good fortunes of the Round Table. She is the providential fée that saves the souls born in high society and raised in the “courtois” worship of the lady. However, her powers of healing can reverse into a nefarious power when the fée has her ego wounded.

III/ The fatal temptress

In the prose Arthurian romans of the 13th century, Morgane can be summarized by one place. After being neglected by her lover Guyomar, she creates “le Val sans retour”, the Vale of No-Return, a place which will define her as a “femme fatale”. This place transports without the “littérature courtoise” the idea of the Celtic Otherworld. Also called “Le Val des faux amants” (The Vale of False Lovers), “le Val sans retour” is a cursed place where the fée traps all those that were unfaithful to her, by using various illusions and spells. As such, she manifests both her insatiable cruelty and her extreme jealousy. Lancelot will become the prime victim of Morgane because, due to his love for Queen Guinevere, he will refuse her seduction. The feelings of Morgane towards Lancelot rely on the ambivalence of love and hate: since she cannot obtain the love of the knight by natural means, she will use all of her enchantments and magical brews to submit Lancelot’s will. In vain. Lancelot will escape from the influence of this wicked witch. In “La Mort le roi Artu”, still for revenge, Morgan will participate in her own way to the decline to the Arthurian world: she will reveal to her brother, king Arthur, the adulterous love of Guinevre and Lancelot. She will bring to him the irrefutable proof of this affair by showing her what Lancelot painted when he had been imprisoned by her. The terrible war that marks the end of the Arthurian world will be concluded by the battle between Arthur and Mordred, the incestuous son of Arthur and Morgan. As such, Morgan appears as the instigator of the disaster that will ruin the Arthurian world. She manipulates the various actors of the tragedy and pushes them towards a deadly end. It should be noted that any sexual or romantic relationship between Arthur and Morgane are absent from the French romans – they are especially present within the British compilation of Malory, La Mort d’Arthur.

Behind the possessive woman described by the Arthurian texts, hides a more complex figure, a leftover of the ancient Celtic goddess of destinies. Cruel and manipulative, Morgan is fuses with the fear-inducing figure of the witch. Despite being an enemy of men, she keeps seeking their love. All of her personal tragedy comes from the fact that she fails to be loved. Always heart-sick, she takes revenge for her romantic failure with an incredible savagery. Her brutality manifest itself through the ugliness that some text will end up giving her – the ultimate rejection by this Christian world of this “devilish and lustful temptress”. “La Suite du Roman de Merlin” will try to give its own explanation for this transformation of Morgane, from good to wicked fairy: “She was a beautiful maiden until the time she learned charms and enchantments ; but because the devil took part in these charms and because she was tormented by both lust and the devil, she completely lost her beauty and became so ugly that no one accepted to ever call her beautiful, unless they had been bewitched”. In this new roman, she is responsible for a series of murders and suicides – and as the rival of Guinevere, she tries to cause King Arthur’s doom by favorizing her own lover, Accalon. Another fée, Viviane, will oppose herself to her schemes.

The demonization of the goddess is however not complete. Morgan appears in several “chansons de gestes” of the beginning of the 13th century, and even within the Orlando Furioso of the Arisote, in the sixth canto, in which she is the sister of the sorceress Alcina. She is presented as the disciple of Merlin. Seer and wizardess, she owns (within Avalon or the land of Faerie) a land of pleasure, a little paradise in which mankind can escape its condition. At the same time the Arthurian texts discredit her, she joins a strange historico-pagan syncretism, by being presented as the wife of Julius Caesar, and as the mother of Aubéron, the little king of Féerie.

After the Middle-Ages, the fée Morgane only mostly appears within the Breton folklore (the French-Britton folklore, of the French region of Bretagne). There, old mythical themes which inspired medieval literature are maintained alive, and keep existing well after the Middles-Ages. Morgane is given several lairs, on earth or under the sea. In the Côtes-d’Armor, there is a Terte de la fée Morgan, while a hill near Ploujean is called “Tertre Morgan”. There is an entire branch of popular literature in Bretagne (such as Charles Le Bras’ 1850 “Morgân”) where the fée represents the last survivor of a legendary land and the reminder of a forgotten past. She expresses the nostalgia of a lost dream, of a fallen Golden Age. True Romantic allegory of the lands and seas of Bretagne, she most notably embodies the feeling of a Bretagne land that was in search of its own soul.

However, it is her role of “cursed lover” that stays the most dominant within the Breton folklore. The vicomte de La Villemarqué, great collector of folktales and popular legends, noted in his “Barzaz Breiz” (1839) that the “morgan”, a type of water spirits, took at the bottom of the sea or of ponds, in palaces of gold and crystal, young people that played too close to their “haunted waters”. The goal of these fairies was to kidnap them to regenerate their cursed species. This ties the link between these “morganes” (also called “mary morgand”) and the Antique “fairy of fate”. Similar names, a same love of water, and the presence of the “land below the waves”, of a malevolent seduction – these are the permanent traits of Morgane, who keeps confusing and uniting the romantic instinct for love, and the desire for death. More modern adaptations of the legend (such as Marion Zimmer Bradley’s novels) weave an entire feminist fantasy around the figure of this fairy, supposed to embody the Celtic matriarchy.

#arthuriana#arthurian myth#arthurian legend#morgane#morgan#morgan le fey#fée#french folklore#folklore of bretagne#celtic mythology#irish mythology

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Breton fairy: The Groac'h of the Isle of Lok

La Groac'h, 2024. Illustration made with watercolor and gold glitter paint.

Groac'h (plural: groagez) is the Breton word for fairy or witch, that eventually evolved to mean an old creature of deceptive beauty (source: Wikipedia).

I found inspiration for this depiction in the most famous tale about a Groac'h: Émile Souvestre's The Groac'h of the Isle of Lok (La Groac'h de l'île du Lok, in Le Foyer Breton, 1844). There, she's depicted as a beautiful yet maleficent fairy, living in an underwater palace. Here in Andrew Lang's translation (The Lilac Fairy Book, 1910):

"Now, unless you have been under the sea and beheld all the wonders that lie there, you can never have an idea what the Groac'h's palace was like. It was all made of shells, blue and green and pink and lilac and white, shading into each other till you could not tell where one colour ended and the other began. The staircases were of crystal, and every separate stair sang like a woodland bird as you put your foot on it. Round the palace were great gardens full of all the plants that grow in the sea, with diamonds for flowers. In a large hall the Groac'h was lying on a couch of gold. The pink and white of her face reminded you of the shells of her palace, while her long black hair was intertwined with strings of coral, and her dress of green silk seemed formed out of the sea. At the sight of her Houarn stopped, dazzled by her beauty. 'Come in,' said the Groac'h, rising to her feet. 'Strangers and handsome youths are always welcome here. Do not be shy, but tell me how you found your way, and what you want.'"

#illustration#watercolour#artists on tumblr#fairy art#fairycore#brittany#bretagne#underwater art#sea creature#sea fairy#mermaid art#mermay 2024#folklore art#folktales#fairytales

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marseille. Au MuCEM, une très intéressante expo : "Fashion-Folklore".Le titre parle de lui-même.

corsages bigoudens - Pont-L'Abbé, Bretagne, 1920 et 1930

Jean-Paul Gautier pour "Paris-Brest" 2015

Maria Grazia Chiuri pour Dior "Croisière" 2023

corsage bigouden - Pont-L'Abbé, Bretagne, 1930

#marseille#MuCEM#expo#fashion folklore#folklore#fashion#mode#bretagne#bretonne#bigouden#pont-l'abbé#jean-paul gautier#maria grazia chiuri#dior#christian dior

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

-Wikipedia page of the Drennec commune in Bretagne

English translation for non-french speakers:

The stele near the porch has a notch which, according to legend, was cut by the chain with which an otherwise unknown saint, Saint Ursin, also known as Saint Thouzan (the chapel is dedicated to this saint and the name Landouzen derives from him), tied up the dragon that was terrorizing the region. The saint then drowned the monster in a nearby marsh.

So yeah Neuvillette's first name is Drennec now thanks for coming to my ted talk. (/lh)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Flight of King Gradlon, oil on canvas made around 1884 by Evariste-Vital Luminais

King Gradlon and the Legend of Ys:

"King Gradlon (Gralon in Breton) ruled in Ys, a city built on land reclaimed from the sea, sometimes described as rich in commerce and the arts. He lived in a wealth palace of marble, cedar and gold. In some versions, Gradlon built the city upon the request of his daughter Dahut, who loved the sea. To protect Ys from inundation, a dike was built with a gate that was opened for ships during low tide. The one key that opened the gate was held by the king.

Some versions, especially early ones, blame Gradlon's sins for the destruction of the city. However, most tellings present Gradlon as a pious man, and his daughter Dahut as a sorceress or a wayward woman who steals the keys from Gradlon and opens the gates of the dikes, causing a flood which destroys the whole city. A Saint (either St. Gwénnolé or St. Corentin) wakes the sleeping Gradlon and urges him to flee. The king mounts his horse and takes his daughter with him, but the rising water is about to overtake them. Dahut either falls from the horse, or Gradlon obeys a command from St. Gwénnolé and throws Dahut off. As soon as Dahut falls into the sea, Gradlon safely escapes. He takes refuge in Quimper and reestablishes his rule there." - Gradlon wikipedia article

#Evariste-Vital Luminais#art#The Flight of King Gradlon#bretagne#legend of ys#breton#breton folklore#brittany mythos

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Korrigans

Note: I'm an English learner and I wrote this text to practise my written English. If you want to give me feedback about my English, please go ahead!

Korrigans are creatures from the folklore of Brittany (North-West of France) that look like little black and hideous people. They are described as hairy, thickset and they have frizzy hair. They keep with them a purse which is said to be full of gold. But if someone stole it, they would find inside only dirty horsehair and a pair of scissors. These pranksters like playing tricks on Christians who don’t respect their duty. They are sometimes accused of stealing animals or objects, or making a mess in houses.

See more :

They usually live in megalithic monuments, which are sometimes called “ville des korrigans,” “city of the korrigans”. They keep inside of these constructions their treasure, which they take out at night to spread it out on the ground. Sometimes they do it in the summer sunshine. Still at night, in some stories at full moon, they dance around blocks of stone, singing often the days of the week till Friday. If one tries to complete the song adding the two last days, the korrigans might dislike it and shower them with blows. If one runs into them, they could get swept up in the korrigans’ dance. They are forced to dance to the point of exhaustion.

Korrigans seem to be related to fairies. For instance, when a fairy steals a human baby, sometimes, it substitutes it with a korrigan.

In Chants populaires de la Bretagne, Théodore Hersart de La Villemarqué explains his theory about the origins of korrigans. The ancient bards venerated a goddess called Korid-Gwen. She was associated with another character who was similar to dwarves and who was called Gwion. He was nicknamed “le Nain” (the Dwarf) or “le Nain à la bourse” (the Dwarf with the purse), because he was sometimes represented with a purse in his hand. He was in charge of guarding a mystical vase containing the water of genius, divination and science. Three drops fell on his hand, and he took them to his mouth. Thus, he discovered the future and science. In addition to carrying a purse with them, Armorican dwarves are related with magic, occult, alchemy, metallurgy and divination, which reminds of the legend of Gwion. This link can also be found in a medicinal plant that dwarves are said to like. It is sometimes called the herb of kov, but the Welsh also call it the herb of Gwion, while the Gaulish used the word korig.

In an article from Bulletin de la Société polymathique du Morbihan, Alfred Fouquet tells a legend about a very poor farmer. One night, the farmer saw little black men around a tumulus. Some were dancing on it, others came in and out. The farmer let out a scream in surprise. The little men, who were korrigans, ran away when they heard him. A few days later, the man wanted to go back there at night. It took him the whole night to clear the entrance of the tumulus, but he eventually managed to go inside. He saw the goblins gathered around a pot. They noticed him and started to run all over the place. One of them even went to the neighbouring wood to hang itself, giving to the place the name of “bois du Pendu” (wood of the Hanged one). The man, who was, as we said, very poor, took their pot filled with their treasure, and brought it home. He became rich, and bought the farm where he worked. Years passed, and his children grew up used to a wealthy life. The farmer died, and shortly afterwards, his children reached the bottom of the pot. Finally, his grandson was buried in debt. He had to sell the farm. As he wasn’t able to pay the land rent anymore, he was evicted.

Emile Souvestre, in Foyer Breton, tells another story about these tiny beings. Lao was a Breton bagpipes player. One night, he went down the mountains with a group of people to play during the pardon of the Armor. They reached a crossroads. The women wanted to go down the path that leads to the ocean. But Lao wanted to take the one that goes through the heath. The women explained that there was a city of korrigans and only those who never committed any sin could go through there without trouble. He didn’t believe in these stories and said he would play for them since they liked dancing. He took the path to the heath and began playing. The women went down the way to the sea. He saw the menhir and the korrigans’ home. He heard a murmur which, little by little, became a rumble. Tussocks shook and became hideous dwarves. Surprised and intimidated, Lao stepped back against the menhir. The korrigans surrounded him and forced him to play. The musician was unable to stop, and he played and danced until dawn. Eventually, he collapsed from exhaustion.

Sources

Marie-Charlotte DELMAS. “Korrigan”. In: Dictionnaire de la France Merveilleuse. Paris, France: Omnibus, 2017, p. 418-420.

Alfred FOUQUET. “Un kilomètre en Crach”. Bulletin de la Société polymathique du Morbihan, 1863, p. 1-7.

URL (Gallica)

Théodore Hersart de La Villemarqué. Chants populaires de la Bretagne, First Volume, Fourth edition, p. 46-53. Paris : Leipzig, 1846.

Désiré Monnier, Aimé Vingtrinier. “Les Fées Chrétiennes”. In : Croyances et traditions populaires recueillies dans la Franche-Comté le Lyonnais la Bresse et le Bugey. Lyon : Henri Georg, 1874, p. 393-397.

Prisma Media. “Korrigan : qui est cette créature légendaire bretonne ?” Geo [online]. Gennevilliers. 05/11/2021. [Visited between 01/06/23 and 02/06/23]

URL

Louis Pierre François Adolphe Chesnel de la Charbouclais (marquis de). “Gauriks ou Gores”, p. 216, “Korandons”, p. 262, “Korigans ou Korigs”, p. 262, “Korils ou Kourils”, p. 264, “Kornikaneds”, p. 267, “Poulpicans, Poulpiquets, ou Korils”, p. 466, “Teus”, p. 594. In: Dictionnaire des superstitions, erreurs, préjugés et traditions populaires, vol. 20 of Troisième et dernière encyclopédie théologique. J.-P. Migne, 1856

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Costumes de Bretagne

Bruno Hélias

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Breton Feast of All Souls in the Late 19th Century

“The day of the dead or of All Souls, as we call it, is commonly the second of November. Thus in Lower Brittany [in France] the souls of the departed come to visit the living on the eve of that day. After vespers are over, the priests and choir walk in procession, ‘the procession of the charnel-house,’ chanting a weird dirge in the Breton tongue. Then the people go home, gather round the fire, and talk of the departed. The housewife covers the kitchen table with a white cloth, sets out cider, curds, and hot pancakes on it, and retires with the family to rest. The fire on the hearth is kept up by a huge log known as ‘the log of the dead’ (kef ann Anaon). Soon doleful voices outside in the darkness break the stillness of night. It is the ‘singers of death’ who go about the streets waking the sleepers by a wild and melancholy song, in which they remind the living in their comfortable beds to pray for the poor souls in pain. All that night the dead warm themselves at the hearth and feast on the viands prepared for them. Sometimes the awe-struck listeners hear the stools creaking in the kitchen, or the dead leaves outside rustling under the ghostly footsteps.”

—J. G. Frazer, Adonis, Attis, Osiris, part 2 (The Golden Bough, vol. VI, 1914, p. 69)

The dead seem to have a pervasive presence in Breton folklore. Here, a procession of dead Breton washerwomen harass a night-traveler to "chain them to their own damnation" (they had to wash the linen of the dead for all eternity).

(Source: Jean-Édouard Dargent, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

#brittany#bretagne#france#feast of all souls#all souls day#breton#the dead#jg frazer#the golden bough#the golden bough vol vi#adonis attis osiris#spirits#offerings#folklore#19th century

0 notes

Text

instagram

0 notes

Text

Witches and the Genius Loci: Folkloric Methods of Contact and Communion

The witches of old knew how to speak with the land. They didn’t just live in the wild, they wove themselves into its fabric, calling on the hidden ones in the earth, water, and wind. How did they do it? The answers would be as varied as the forests and fields they walked. But there are patterns we can see in all of them. Here are some of the ways I have discovered witches (in European folklore) reached out to the spirits of the land.

𖤐 Offerings at Spirit Dwellings

A witch rarely arrived empty-handed. Milk poured at the base of an ancient tree, ale left at the mouth of a cave, a bit of bread crumbled into a stream, these were ways to invite the unseen to draw near. Scottish folklore describes the gruagach, a guardian spirit, receiving libations of milk at stones and riverbanks (Campbell, Superstitions of the Highlands and Islands of Scotland, 1900). In Belgium and the Netherlands, witches were accused of offering beer and bread to the duivel, a local spirit often conflated with the Devil in later Christianized accounts (De Blécourt, Het Duivelspact, 1993).

𖤐 By Bone and Blood

In Scandinavian folklore, the practice of bjarmic magic involved burying bones to anchor spirits to the land, while Livonian witches were said to whisper their desires into a skull before placing it in the earth (Rääbis, Eesti Rahvapärimus ja Nõiakunst, 1926). In the 17th-century Scottish witch trials, accused witches described sealing pacts with land spirits by pricking their fingers and pressing the blood into soil or stone (Pitcairn, Ancient Criminal Trials in Scotland, 1833).

𖤐 Spirit-Flight and Dreamwalking

Witches didn’t always wait for spirits to come to them. Many traveled in spectral form, slipping into trance states with the help of charms or salves to reach spirits. The Trollenfrauen of German folklore and the Heks of Scandinavian folklore were said to enter deep sleep while holding a stone, allowing them to fly in spirit to the places where land spirits dwelled (Müller, Sagen aus Westfalen, 1857). In 17th-century witch trials from Flanders, accused witches claimed to lie still in darkness, feeling themselves lifted away to converse with spirits at crossroads and hollow hills (Proces tegen Tanneken Sconincx, 1606).

𖤐 Bone Charms & Rattles

A witch’s tools were often made from the dead. Flemish folklore mentions witches carrying duivelsfluitjes—small bone whistles said to call spirits when blown at twilight (De Meyer, Volksverhalen uit Vlaanderen, 1970). The bohnenzauber of Germanic folklore involved threading small bones together to create a rattling charm that stirred spirits of the wild (Grimm, Deutsche Mythologie, 1835).

𖤐 Turning Up the Soil

Some witches were accused of whispering into the ground, digging their fingers into the soil as they spoke. In Swedish folk belief, jordfastan involved burying a charm/offering (usually a piece of cloth or a coin) under a tree to call on spirits of the land (Hylten-Cavallius, Wärend och Wirdarne, 1863). Scottish trial records mention witches placing coal or burned bones in the earth as a form of spirit-binding magic (Pitcairn, Ancient Criminal Trials in Scotland, 1833).

𖤐 Skin-Turning and Familiars

In Breton folklore, witches who wished to meet the hidden spirits of the woods were said to transform into black dogs or other beasts before travelling into the deep forest (Sébillot, Le Folklore de la Bretagne, 1904). In Scotland, it was believed that witches who took the form of hares or crows could cross into the spirit world more easily (Popular Tales of the West Highlands, Campbell, 1860).

𖤐 Betwixt Earth and Water

The land’s voice is loudest in the places where two worlds meet. Marshes, riverbanks, and tidal flats; these places belonged to neither land nor water, making them perfect for spirit-calling (my favourite method). In English and Welsh folklore, witches were said to stand barefoot in water at night, calling on spirits with secret words (Henderson, Folklore of the Northern Counties of England, 1866). In Estonia, it was believed that standing in a bog at sunset allowed one to hear the voices of spirits whispering in the wind (Loorits, Eesti Rahvausund, 1949).

Seeking out the spirits of the land is integral to building a foundational practice in witchcraft and connecting to your landscape. It is these spirits that grant you access to the powers of the land that you require to make your works work.

#folk witchcraft#traditional witchcraft#witchcraft#traditional witches#folk witch#folk witches#witch#trad witch#folklore#spells#spirit work#genius loci#witching spirits#spirits#spirits of the land#witch tips#beginner witch tips

204 notes

·

View notes