#blackhistory2021

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Video

vimeo

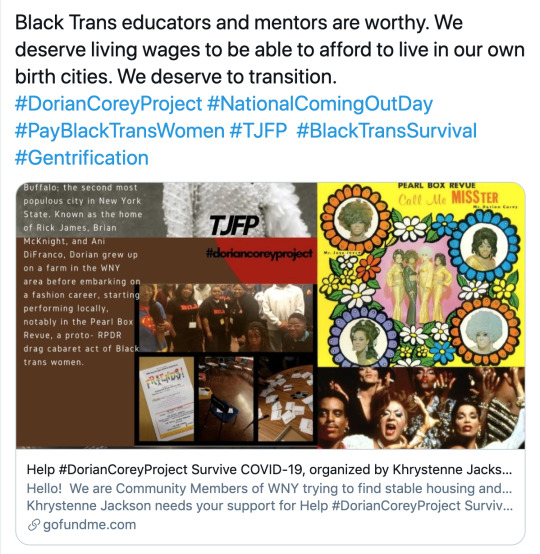

Our first livestream for #DorianCoreyProject #BlackHistoryMonth #WomensHistoryMonth

https://gofund.me/62170914

#doriancoreyproject#blackhistory2021#womenshistorymonth#february 2021#black trans lives matter#blacktranscrowdfund#blacktranseverything#tjfp#livestream#black trans liberation#black trans women#buffalo ny

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Vaguely) On Afro-Scifi & Afrofuturism or My Dilemmas in a Story I'm Writing - A Potential Great Gatsby Rewrite

(Vaguely) On Afro-Scifi & Afrofuturism or My Dilemmas in a Story I’m Writing – A Potential Great Gatsby Rewrite

note for potential readers: this year I’m challenging myself to create and release work consistently with all its imperfections. i’m sure i’ve made some misspellings despite my best efforts and missed some points i meant to touch but nonetheless i am adding my voice to a conversation and I hope you’ll join me with grace. As I dredge through cups of coffee, job applications, and Pinterest boards…

View On WordPress

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

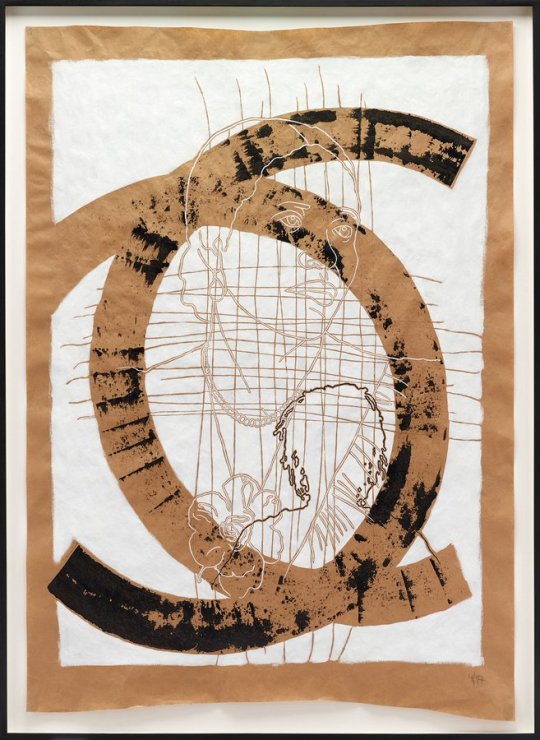

Anna Cooper and Charles H. Lawrence. Acrylic on Paper, 1997. Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. I.D. Flores III, Mr. and Mrs. Oscar McNary, and Mr. and Mrs. Edwin J. Ducayet, Jr. © Annette Lawrence

#exhibition#contemporaryart#memory#grandparents#acrylic#gibbsmediagroup#lifethroughart#contemporary#dallas#annettelawrence#museum#paperart#brown paper#blackartmatters#africanamericanart#americanart#family#blackhistory2021#artists on tumblr#women artists#heritage

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prince Of Florida 🤴🏿🪶

1 note

·

View note

Text

Stamp it out.

Hope dies last

At least it should

Instead it’s that twat

Sat in the pub.

Up he gets

When you head to the bar

Back from London?

Not for me taa.

Down there once

A few year back

Full of them Pakis

And n*****s, no, blacks.

Losing your temper

You swallow your beer

Ask the ignorant twat

How he got here?

Tonight pal? I drove

I'm leaving the car

I'll walk back I think

Christ it's not far.

You look at him blankly

Toning it down

The twat is now puzzled

Here comes the frown.

No, you your family

Where are you from?

I'm Irish and Welsh

There aint no pure pom.

He rolls up his sleeve

Revealing his ink

St George, his mum

A dragon...you think.

Lovely you say

The colours the lot

Amazing the skill

When they're out of the cot.

His heart rate racing

He's been here before

The penny now sailing

Towards the floor.

I'm English you cunt

I served for our queen

She's yours you can have her

Outside if you're keen?

You stamp and you stamp

And nothing is said

Enjoy the silence.

The racist is dead.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

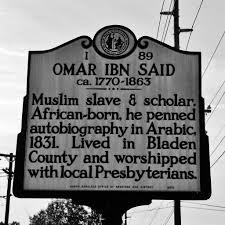

BHM: the life of omar ibn said

In today’s racially charged climate, the call to learn from and reckon America’s violently colorful history with people of color has reached a fever pitch. In order to move forward, we must first study our past. This Black History Month should be more than just a time elementary school teachers rattle off facts about Madam C.J. Walker and George Washington Carver. Rather, we as a people must use this opportunity to allow ourselves to feel the long suppressed pain of our black brothers and sisters so that we may begin to heal together. Surely, much of the racial injustice that is prevalent today stems from the conscious decision to enslave masses of people against their will whilst forcing them to desert their culture, land, and families.

One such story is that of West African slave and author Omar ibn Said. In early 2019, the Library of Congress acquired the Omar Ibn Saeed collection, including his original Arabic autobiography written in the early 1800s, along with its English translation The Life of Omar Ibn Said from the 1860s. Now that these documents have been made public, we have access to firsthand accounts of slavery in America which are unedited by ibn Saeed’s owners, unlike other slave’s autobiographies that were written in English. In fact, many of the accounts of slavery and the treatment of enslaved people we read today are derived from white abolitionist writers, rather than black enslaved people. This is often because slaves did not have the time, the ability, or the resources to record their conditions, and even if an enslaved person did dare to write an autobiography, he or she risked being caught by an “owner” and being severely punished. Still, there are written accounts of some enslaved people’s experiences, but these accounts are tainted by the possibility of being dictated or altered by an “owner”. What makes ibn Said’s work exceptional is that he chose to record his life in Arabic, a medium his “owner” was unlikely to have been able to read, let alone contour to his whims. Due to his foresight, today we have access to a work that facilitates an enhanced understanding of the complications of slavery in America and what it meant to be Muslim in the 19th century.

Ibn Said begins his autobiography with Al-Mulk, the sixty-seventh chapter from the Quran. After praising Allah ﷻ and sending salutations of peace and blessings upon Muhammad ﷺ, he begins quoting the Quranic passage,

“Blessed be He in whose hand is the kingdom and who is Almighty; who created death and life that He may make you the best of his works” {67:1}.

It is no accident that ibn Said chose, out of 114 chapters, consisting of a total 6,236 verses, to begin with Al-Mulk, which means “The Sovereignty.” The very first ayah (verse) he pens establishes that Allah ﷻ is the owner of all and that he controls both life and death, which leaves no room for the ownership of man over any form of life. “It is a fundamental criticism of the institution of slavery,” says Mary-Jane Deeb, chief of the African and Middle Eastern Division at the Library of Congress.

Personally, what I find astounding is the stark contrast between his manner of writing and the way in which other writers of the time incorporate religion into their work. For instance, we can observe a less nuanced tone in American author Ralph Waldo Emersons’ "Nature," published in 1836, in which he declares,

“I become a transparent eye-ball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God.”

While Emerson sees God through the world around him, ibn Said understands the world around him through God. Perhaps this difference arises as a result of each writer’s position in life. Emerson already had access to material possessions, which led him on a journey to “find” God amongst a world he had already defined materialistically. On the other hand, ibn Said had very little to nothing to his name, thus his world view was shaped by the beliefs he brought with him in the long boat ride over from Futa Toro. This fundamental difference illustrates the disparity of conditions faced by free and enslaved Americans.

Interestingly, when recalling his life within America, ibn Said’s description of his experiences do not mirror the general perception of enslaved life most carry. Although he does mention the abuse he endured at the hands of Johnson, the man who he was sold to in Charleston, his dislike for Johnson isn’t solely due to him being a “wicked man,” rather he repeatedly mentions that he “had no fear of God at all.” Contrary to the notion that enslaved people fled the persecution and excruciating labor of the fields as some form of refugees, ibn Said mentions in his manuscript that he made the choice not to stay with Johnson, as he, “was afraid to remain with a man so depraved and who committed so many crimes.” Yet, when speaking of North Carolina’s governor John Owen and his brother Jim Owen, who ibn Said “remained in the place of” after being caught, he describes them as “good men” and praises them for reading the gospel and “having so much love to God.” In fact, when asked if he “were willing to go to Charleston City,” ibn Said responds, “No, no, no, no, no, no, no, I not willing to go to Charleston. I stay in the house of Jim Owen.” Despite being able to depict the Owens in a negative light, given that they wouldn’t understand his criticism since it was written in Arabic, he talks highly of each member of the family and even refers to Jim Owen as sied, or master, postulating that enslaved people might have had a relationship of respect and fondness towards their “masters.”

Intriguingly, ibn Said never refers to himself as a slave, and speaks about his circumstances with a refreshing air of self- reliance. To him, he didn’t flee slavery in Charleston; rather, he left a “wicked man” who ibn Said made the choice not to stay with. Perhaps the aspect of ibn Said’s life that vastly sets him apart from the mainstream understanding of a slave’s life is his advanced education. While most enslaved people are regarded as being illiterate, ibn Said wrote letters and personal writings in beautiful calligraphy and had many passages of the Qur’an committed to memory. Along with his manuscript being evidence enough of just how highly educated he was, ibn Said writes, “I continued my studies twenty-five years,” which means he was only six when he first “sought knowledge under the instruction of a Sheikh called Mohammed Seid.” Similarly, the elegance with which he writes is truly a testament to his intelligence. Aside from his cross examination of Christianity and Islam, and his interwoven subtle critisms of the institution of slavery, ibn Said masterfully uses language that illustrates both his wisdom and humility as he looks back on his life. In fact, he even includes an effective introduction and conclusion to his work. From ibn Said’s outlook on life, which allows him to describe his “master” fondly, to his blaring sense of self-determination, he redefines what it means to be an enslaved person in America.

Ibn Said, within his autobiography, attempts to analyze the interwoven tale of his experiences in regards to both Islam and Christianity. He mentions his past rituals of walking to the mosque for prayer in the daytime and at night, and the zeal with which he read the Quran, all before he came to America. Yet, he repeatedly praises the Owen’s for reading the gospel, mentioning that they would read it to him, and implies that he may have converted to Christianity. Due to the many Quranic verses and prayers scattered in his writing, it is difficult to tell whether ibn Said truly brought faith in the Christian religion or only accepted it as an outwardly gesture to ensure his safety in the South. Either way, he was able to examine each religion objectively. At one point, ibn Said even contrasts the manner in which he prayed as a Muslim in opposition to how he prays as a Christian by providing the entire chapter of Al-Fatiha from the Quran, while adding that now he prays, “Our Father.” Interestingly, he never criticizes, gives his opinion on, nor shows a preference towards either religion. This neutrality drives home not only ibn Said’s intellect, but the fact that he was simply searching for the true path, without blindly following whatever he was told.

Perhaps what sets ibn Said apart from other enslaved people in regards to religious aspirations is his twenty-five years spent in seeking out knowledge in Foto Turo. This disciplined early education instilled in him a zeal which followed him across the Atlantic, allowing him to become a lifelong learner. In fact, he was eager to listen to the gospel whenever someone would read it to him. Although he doesn’t specifically mention that he is Christian, ibn Said places a substantially large emphasis on the relationship between God and human beings, as well as the need to read and understand scripture. Even if he remained Muslim, ibn Said never makes clear his opposition to Chrisitan ideology. Rather he reiterates the necessity of faith in one’s life by praising the Owens for being a religious family while cursing at his first “owner” Johnson for his lack of attachment to God.

Aside from The Life of Omar Ibn Said’s literary brilliance and historical significance when analyzing slavery in America, the work resonates with me on a personal level. When I first heard that the Library of Congress had published this work as a collection, along with other hand written pieces such as personal letters, my interest was sufficiently piqued. What I didn’t anticipate, however, is just how much I would relate to the story of a West African slave living in the 19th century. Before reading the English manuscript of The Life of Omar Ibn Said, I first made my way through the Arabic documents. Written in mesmerizing handwriting which, due to my severe lack of knowledge, I can only describe as 19th century African calligraphy, ibn Said begins with the basmallah. As Muslims, we recognize this prayer as one to recite before embarking on any task or journey, even as small as lifting the lid off of a pot. Then he goes on to send salutations upon the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ in a manner so customary that I caught myself doing so involuntarily. When I realized he was quoting surah Al- Mulk, one that my mother helped me commit to memory and would read with me every night before going to bed as a child, I was touched. Despite being stripped of his culture, isolated from his people, and forced onto a new land, ibn Said did not forget the essentials of his religion. It was at that moment that I resolved to start reciting Al- Mulk at night again. When he mentions the Shuyukh, or scholars, under whom he gained his education, I felt the respect emanating from his words. In that moment, the oft- quoted words came to mind, “I am a slave to the one who teaches me even a single letter.”

Perhaps the most striking part of ibn Said’s journey is the fact that while on the run for nearly a month, he risked capture to stop at a church and pray. Although he knew the inherent dangers that would stem from being apprehended, ibn Said’s imaan (faith) proved stronger than his fear, as he was eventually caught and sold back into slavery. In this defiant act of his, I find reasons to feel both ashamed and hopeful. Ibn Said actually faced the possibility of being killed, yet he still chose to preserve his religious traditions. Meanwhile, when prayer time rolls in while I am still on campus, I feel the need to squeeze into the tiniest corner I can find to quickly pray just the bare minimum so that I don't inconvenience anyone else around me. Yet, the fact that ibn Said was caught and sold to a man about whom he mentions, “During the last 20 years, I have known no want in the hand of Jim Owen,” is cause enough for me to be hopeful that the slight stress I endure while praying in public will surely bring about, through Allah’s ﷻ unlimited Grace, great fortune in my own life. Although we are separated by a span of almost two centuries, ibn Said’s struggle is inspiring in ways I couldn’t have anticipated.

In the ever-divisive times in which we now find ourselves living, The Life of Omar Ibn Said is a welcome triumph of human spirit and optimism. Not only are ibn Said’s life and work subjects of intrigue, but the implications of his writing reaffirm a story that many of us have long since forgotten: American slavery does not take one shape, size, or form. Although the institution itself was horrific, we must contend that some enslaved people did find a greater purpose in their lives. Ibn Said was one of them. He rose above the hatred surrounding him, and speaks of the men who held him in captivity with astonishing reverence. How ibn Said was able to look back at the progression of events in his life and not be angered that a scholar as learned as he could be enslaved is a lesson for us all. Truly, ibn Said’s knowledge provided him with humility and wisdom. Perhaps, if he had succumbed to human nature and only displayed outrage at his conditions, which would have been completely justified, we would not have the masterpiece that is the Omar Ibn Said collection today. As we continue to engage literature and history as a way of understanding the world, Omar ibn Said stands as a reminder to value the narrative of every individual, because, rather than a large-scale standpoint in viewing the world, personal experiences speak to the very core of what it means to be human. We all deserve the chance to live prosperously and this cannot be the case until we rectify the mistakes of our past and work towards ensuring the sanctity of every life.

Carey, Jonathan. “The Extraordinary Autobiography of an Enslaved Muslim Man Is Now Online.” Atlas Obscura, Atlas Obscura, 26 Jan. 2019, https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/omar-ibn-said-autobiography-digitized.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. “Nature.” EMERSON - NATURE--Web Text, https://archive.vcu.edu/english/engweb/transcendentalism/authors/emerson/nature.html.

ibn Said, Omar. “About This Collection : Omar Ibn Said Collection : Digital Collections : Library of Congress.” The Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/collections/omar-ibn-said-collection/about-this-collection/

#omaribnsaid#blackhistory#black history matters#blackhistoryisamericanhistory#blackhistoryisworldhistory#blackhistory365#blackhistoryeveryday#blackhistoryeverymonth#blackhistory2021#black history year#blackhistoryfacts#blackhistorymonth#african american#africanamericanhistory#african#africanhistory365#blacklivesmatter#blackamericans#support blm#blm2021#blm movement#black lives have value#black lives are human lives#black lives are needed#black lives still matter#black lives have always mattered#blacklivesalwaysmatter#black lives are important#black lives are worthy

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

If you don't know who these ladies are please do your research.

#blackhistory2021#staywoke#no justice no peace#black excellence#black girls matter#blackpower#most wanted#happy international women's day

1 note

·

View note

Photo

In celebration of Black History Month #shespire #BlackHistory2021 #GladysWest #DrGladysWest https://www.instagram.com/p/CoSYjgFuBiJ/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Photo

In 1970, Aretha Franklin offered to post bail for Angela Davis, who was jailed on trumped-up charges. Aretha Franklin told Jet magazine in 1970, “My daddy says I don’t know what I’m doing. Well, I respect him, of course, but I’m going to stick by my beliefs. Angela Davis must go free. Black people will be free. I’ve been locked up (for disturbing the peace in Detroit) and I know you got to disturb the peace when you can’t get no peace. Jail is hell to be in. I’m going to see her free if there is any justice in our courts, not because I believe in communism, but because she’s a Black woman and she wants freedom for Black people. I have the money; I got it from Black people—they’ve made me financially able to have it—and I want to use it in ways that will help our people.” #blackhistory2021 #arethafranklin #angeladavis #blackwomen #womensmonth #womenshistorymonth #freedom #blackentertainment #artist (at Los Angeles, California) https://www.instagram.com/p/CMhe4uRp-yj/?igshid=3pbycsjmaabv

#blackhistory2021#arethafranklin#angeladavis#blackwomen#womensmonth#womenshistorymonth#freedom#blackentertainment#artist

0 notes

Audio

0 notes

Link

In the 11th. century A.D. a woman named NugayMath commanded a troop of 300 black Moorish female warriors who laid siege to a Spanish castle in Europe.

#blackhistoryisamericanhistory#blackhistory2021#blackhistoryfacts#blackhistoryliveitlearnitmakeit365daysayearshirt#blackhistory365

0 notes

Text

The Original Indigenous People On A American Tobacco Farm. The creators of Tobacco. 🌱🌿🌳💨

1 note

·

View note

Text

#fashion#style#designer#fashionblogger#styledbywindy#fashionstylist#African American Designer#blackhistory2021

0 notes

Text

"He was killed for man's freedom."

JIMMIE LEE JACKSON'S TOMBSTONE

#black lives matter#black stories#blackhistorymonth#blacklivesmatter#black lives are worthy#blackhistoryfacts#blackhistoryinthemaking#blackhistory2021#blackhistoryisamericanhistory#black history matters

0 notes

Photo

As Black History Month begins to wind down, I want take a moment to say that it's been a highlight for me this year so far to share posts dedicated to this amazing month that it is (and should be) every month. Continue to learn and spread the knowledge. #blackhistory #blackhistoryisnow #blackhistory2021 #blackhistoryisamericanhistory (at Huntsville, Alabama) https://www.instagram.com/p/CLtw9zhFVWo/?igshid=16841i6byc1h4

0 notes