#black history mexico

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Festival de la Tercera Raíz (Third Root Festival) is a vibrant celebration in Mexico that honors Afro-Mexican heritage, recognizing and elevating the unique cultural, historical, and social contributions of Afro-descendant communities in the country. Primarily celebrated in the coastal regions of Guerrero, Oaxaca, and Veracruz, the festival brings together traditional music, dance, food, art, and spiritual practices in a rich tapestry of Afro-Mexican identity and resilience. It underscores the legacy of African influence in Mexico—often overlooked in mainstream historical narratives—paying homage to the "third root" of Mexican heritage, alongside the Spanish and Indigenous influences.

The name "Tercera Raíz" (Third Root) reflects the recognition of African roots as an essential component of Mexican heritage. While Indigenous and European (Spanish) roots are well-known, the African heritage that arrived with the transatlantic slave trade in the 16th century has often been overlooked. During this era, enslaved Africans were brought to New Spain (now Mexico), predominantly working in the sugarcane plantations, mines, and alongside Indigenous laborers in various regions. Over time, African, Indigenous, and Spanish cultures intermingled, forming a rich and unique cultural synthesis that shaped the identity of Afro-Mexican communities.

The festival was developed as part of a broader movement to increase visibility and acknowledgment of Afro-Mexican culture, which had long been marginalized in Mexican society. Recognition of Afro-Mexican communities gained momentum especially in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, as these communities advocated for the preservation and acknowledgment of their heritage. The festival plays a crucial role in affirming Afro-Mexican identity, celebrating their unique cultural practices, and educating the broader public about the African presence in Mexican history.

Although not confined to a single location, the Third Root Festival is most prominently celebrated in the Costa Chica region, which spans parts of Guerrero and Oaxaca. This area has historically high populations of Afro-Mexican communities, who have preserved African-influenced customs and traditions over generations. Veracruz, another coastal state with a strong Afro-Mexican presence, also hosts the festival and events to honor Afro-Mexican heritage.

The festival generally takes place during special cultural and commemorative dates, often overlapping with Mexico’s national celebrations or other important Afro-diasporic celebrations. In recent years, it has often been held around the International Day of Afro-Latin, Afro-Caribbean, and Diaspora Women (July 25) and Black History Month (February). However, it is celebrated year-round in various forms in different communities, depending on local traditions and scheduling.

The Festival de la Tercera Raíz incorporates a multitude of cultural expressions, reflecting the African, Indigenous, and Spanish influences that define Afro-Mexican heritage. The festivities highlight music, dance, food, art, religious rituals, and oral traditions, showcasing the distinct cultural identity of Afro-Mexican communities.

— Music and Dance: Traditional Afro-Mexican music and dance are central to the festival. One of the most iconic forms is La Danza de los Diablos (The Dance of the Devils), performed in Guerrero and Oaxaca. In this dance, participants wear devil masks adorned with horns and often move to the beat of drums and marimbas, instruments with African origins. This dance, with its intense rhythms and symbolic masks, is thought to represent the struggles and resilience of African slaves who resisted and survived their conditions. It also includes son jarocho in Veracruz, a musical style characterized by the use of string instruments like the jarana, requinto, and marimbol that blend African, Indigenous, and Spanish influences.

— Cuisine: Afro-Mexican culinary traditions are celebrated through dishes that blend African, Indigenous, and Spanish ingredients and techniques. Dishes often feature plantains, yams, coconut, corn, and a variety of seafood, reflecting both African culinary heritage and local resources. Popular dishes include tostadas de camarón (shrimp tostadas) and pescado a la talla (a grilled fish dish) in coastal areas. Food not only serves as nourishment but also as a medium through which Afro-Mexican heritage is passed down, with recipes and cooking techniques often preserved within families for generations.

— Art and Handicrafts: Art forms are another vibrant component of the festival. Artisans showcase crafts such as woven goods, pottery, and sculpture that reflect Afro-Mexican aesthetics and iconography. Many pieces include symbols and imagery from African cosmologies, such as representations of animals or elements believed to carry spiritual significance. The visual arts in the Third Root Festival offer a means for Afro-Mexicans to celebrate their heritage, create connections to ancestral African lands, and express pride in their communities.

— Spiritual and Religious Practices: Spirituality also plays a significant role in the festival. While many Afro-Mexicans are Catholic, their religious practices often incorporate elements of African spirituality and local Indigenous customs. For instance, some communities maintain African-based spiritual practices such as honoring ancestors, engaging in ceremonial drumming, and participating in rituals connected to nature and spirits. These practices serve as acts of cultural preservation, emphasizing the importance of maintaining connections to African heritage within the framework of Mexican religious practices.

— Oral Traditions and Storytelling: Oral tradition is a key feature of the festival, with elders recounting stories, legends, and songs that have been passed down through generations. These stories often include themes of resilience, freedom, and identity, offering insight into the historical experiences of Afro-Mexicans and their ongoing fight for recognition. Storytelling sessions may involve tales of maroons (enslaved people who escaped and formed independent communities), the significance of particular rituals, and the influence of African deities or heroes in local lore.

— Workshops and Educational Programs: The festival also includes educational components, such as workshops, panels, and seminars, where scholars, activists, and community leaders discuss Afro-Mexican history, identity, and contemporary issues. These events serve as an opportunity to learn about Afro-Mexican contributions to Mexican society, confront issues of racism, and advocate for greater political and social recognition. For young people, the festival offers a space to explore their identity and connect with their heritage through art, music, and dance workshops.

The Festival de la Tercera Raíz plays a crucial role in challenging historical narratives that have minimized or erased Afro-Mexican contributions to Mexican culture. It fosters pride within Afro-Mexican communities and brings awareness to their struggles for cultural, social, and political inclusion. The festival is a moment of collective celebration but also a call to action against systemic discrimination and the invisibility that Afro-Mexican communities have faced for centuries.

In recent years, Mexico has taken strides to recognize Afro-Mexican communities, with the 2020 census marking the first time Afro-Mexicans were included as a distinct ethnic group. The Third Root Festival has contributed to such achievements by spotlighting the lived experiences and cultural wealth of Afro-Mexicans, drawing national and international attention to their contributions and challenges.

Through its vibrant expression of art, spirituality, and communal solidarity, the Festival de la Tercera Raíz reminds all Mexicans and the wider world of the depth and beauty of Afro-Mexican culture. It underscores the ongoing importance of preserving and celebrating Mexico’s African heritage, ensuring that the legacy of the "third root" continues to grow and flourish as an integral part of Mexico’s cultural mosaic.

#festival de la tercera raíz#afro-mexican culture#afro-latinx#mexican heritage#costa chica#afro-mexican identity#afro-latin american history#la danza de los diablos#african diaspora#black history mexico#son jarocho#afro-mexican art#traditional mexican food#mexican folk music#mexican festivals#afro-mexican pride#afro-indigenous#black culture in latin america#mexican history#third root festival

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Allan Grant. Tijuana, Mexico 1962

#allan grant#black and white#photography#vintage#art#history#black and white photography#vintage photography#mexico#1960s

353 notes

·

View notes

Text

Castillo de Chapultepec, México City.

#mexico#cdmx#mexico city#ciudad de méxico#ciudad de mexico#latin america#castle#castillo#castillo de Chapultepec#chapultepec#vitral#floor tiles#tiles#black and white#mural#wall murals#art#artwork#stained glass#cathedral#architecture#interiors#glass art#culture#history

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Imagen de La fuente de Salto del Agua que originalmente estaba ubicada en el cruce de las calles Salto del Agua y Eje Central (entonces llamada la Calzada de San Juan). México D.F.

Ca. de 1850-1900.

La fuente actual no es la estructura original del siglo XVIII. La primera fuente, construida en 1779 por el arquitecto Ignacio Castera, fue diseñada como parte final del Acueducto de Chapultepec, que suministraba agua a la ciudad desde los manantiales de Chapultepec. La fuente servía como el punto de distribución del agua que venía por el acueducto.

#retro vintage#mexico#méxico#retro#cdmx#retrostyle#mexican#vintage#historia#arquitectura#centro histórico#historia de méxico#history#black and white#blanco y negro#urban photography#retro photography#fuente salto del agua#salto

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Humility and modesty are essential elements of Afro-Mexican culture, deeply woven into daily conduct, social norms, and traditions. The Afro-Mexican community, largely concentrated in the Costa Chica regions of Guerrero and Oaxaca, as well as parts of Veracruz, has a rich history shaped by African, Indigenous, and Spanish influences. This unique cultural mix has cultivated values that emphasize humility, respect for community, and a sense of interconnectedness with others and nature.

Humility in Afro-Mexican culture often revolves around the principle of “collectivism” over “individualism,” which means prioritizing the needs of the community or family over self-centered pursuits. In Afro-Mexican communities, this value is reflected in how people interact with one another, placing collective welfare above individual gain. This focus on the community manifests in social events, daily interactions, and the division of resources. Afro-Mexicans are known for sharing what little they may have, as generosity and care for one’s neighbor are considered part of being humble and grounded.

Additionally, Afro-Mexican humility is deeply rooted in the ancestral African customs passed down through generations, such as the practice of acknowledging one’s limitations and showing respect toward those who have more experience or wisdom, often elders. There’s a widespread understanding that one should approach life without pride or arrogance, instead valuing one’s contributions as part of a greater whole. This worldview influences not only individual conduct but also the approach to work, social hierarchy, and even personal achievements.

Modesty is another deeply embedded value within Afro-Mexican culture, affecting both personal presentation and interpersonal relationships. Afro-Mexicans often demonstrate modesty in various aspects of life, including dress, speech, and behavior. Traditional attire in Afro-Mexican communities is modest and functional, with clothing that reflects respect for one’s culture and avoids drawing unnecessary attention. While brightly colored garments are sometimes worn for special occasions, they are also connected to celebrations of cultural identity and are viewed as expressions of cultural pride rather than personal display.

Modesty is also evident in language and communication style. Afro-Mexicans are often cautious about boasting or claiming superior knowledge in social settings, instead fostering an environment of humility and openness. A cultural expectation exists that individuals should not elevate themselves above others, as this can be seen as disrespectful. Even in the case of personal achievements, Afro-Mexicans may avoid publicly emphasizing their successes to prevent appearing arrogant. For example, if someone excels in a skill or talent, they might acknowledge it with gratitude rather than boasting about their abilities, in line with the community’s preference for modest conduct.

Afro-Mexican festivals and celebrations, such as the annual Dance of the Devils (Danza de los Diablos), reveal the integration of humility and modesty into communal expressions of culture. This traditional dance, which honors African ancestors, shows how individual and collective roles blend in Afro-Mexican celebrations. Performers in the Dance of the Devils wear costumes and masks that obscure their personal identities, emphasizing the collective over the individual. This anonymity allows the participants to express their cultural heritage without seeking personal recognition, underscoring a shared legacy rather than an individual performance.

In this context, humility is not only a personal virtue but also a collective ethos. Participants show reverence to their ancestors, celebrating them with a sense of devotion and respect rather than using the event as a platform for personal gain. The humility in these ceremonies is further demonstrated through gratitude and respect toward both the ancestors and the community, with participants recognizing their place in a long continuum of cultural heritage and values.

Respecting and honoring elders is a central aspect of Afro-Mexican humility and modesty. Afro-Mexican culture places high importance on listening to elders and valuing their wisdom, as they are viewed as the keepers of cultural traditions, folklore, and family history. Younger generations are taught to show humility in the presence of elders by listening attentively, addressing them with respect, and considering their counsel as invaluable. This modesty in deferring to elders reflects a deep respect for experience, which is rooted in the African traditions carried through generations in Afro-Mexican communities.

In many Afro-Mexican households, it is common to observe rituals of respect when interacting with older family members, such as avoiding direct eye contact as a sign of humility and speaking in gentle tones. There is also a shared expectation that elders should receive preferential treatment in social settings, such as during meals or community events, where they are often served first. These behaviors demonstrate both humility and modesty, as younger individuals are encouraged to take a step back and allow their elders to have a prominent place in the family and community.

Religious beliefs in Afro-Mexican communities are also tied to humility and modesty, especially in regions where Catholicism, African spirituality, and Indigenous beliefs converge. Many Afro-Mexicans are devout Catholics, and their approach to faith often includes practices that emphasize humility, such as attending mass regularly, participating in communal prayers, and observing traditional saints’ days without the extravagance that might be seen in other settings. Religious observance is usually approached with reverence, modesty, and a focus on honoring God or spiritual beings rather than oneself.

Additionally, in some communities, African-inspired spiritual practices still hold significance, such as the belief in ancestral spirits. These practices emphasize humility by encouraging individuals to maintain a respectful and modest relationship with the spiritual world. Offerings to ancestors, for example, are made in a spirit of gratitude rather than for personal gain, and humility is seen as essential in connecting with these spirits. This reverence extends to how people approach nature, often seen as sacred or as an extension of the ancestral world, further instilling a sense of humility in daily actions.

While Afro-Mexican communities face challenges such as economic hardship, migration, and social marginalization, humility and modesty remain crucial to cultural preservation. Afro-Mexicans often view these values as protective measures, enabling the community to stay resilient and unified. Many Afro-Mexican organizations today advocate for cultural pride while emphasizing humility, as they believe that these values are central to community cohesion and identity.

Younger Afro-Mexicans who migrate to urban areas, where individualism may be more pronounced, often struggle with maintaining these values in environments that prioritize personal success and recognition. Nonetheless, Afro-Mexican communities actively work to pass down these traditions through family education, festivals, and community gatherings, reinforcing the importance of humility and modesty as intrinsic cultural values.

Humility and modesty are not just personal virtues in Afro-Mexican culture; they are foundational pillars that support social harmony, cultural preservation, and spiritual connection. These values manifest in a variety of ways, from daily conduct to community celebrations and intergenerational relationships, reinforcing a shared sense of responsibility and respect. Despite external challenges, Afro-Mexicans continue to uphold these values as core aspects of their identity, seeing them as essential to their cultural legacy and collective well-being.

#afro mexican#afro mexican culture#afro latino#mexican culture#black history mexico#cultural heritage#humility#modesty#dance of the devils#afro latina pride#afro descendants#latino culture#indigenous and afro mexican#afro mexican history#community values#respect for elders#afro indigenous#costa chica#oaxaca#afro diaspora

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hidden History: The Southbound Path to Freedom

When we think of the history of slavery in Texas, Juneteenth in Galveston often comes to mind. However, historians Samuel Collins Ill and Dr. Juan Govea reveal a deeper story that predates Juneteenth by decades. Long before the Emancipation Proclamation, Hispanic abolitionists played a crucial role in helping enslaved people escape to Mexico.

In Texas, the Underground Railroad didn't just lead north; it also ran south. Mexico, having outlawed slavery, welcomed fugitive slaves, offering them freedom and citizenship.

This lesser-known chapter of history shows that enslaved people were not just waiting to be rescued. Many saved for years to pay for their escape to Mexico, demonstrating immense resilience and determination.

Marriages between Mexican men and enslaved African women further illustrate the deep bonds and solidarity in this fight for freedom.

Some who found freedom in Mexico went on to build successful lives. For example, a former slave of Sam Houston became a barber in Matamoros, while another rose to the rank of officer in the Mexican army.

These stories challenge us to broaden our understanding of the Underground Railroad and recognize the diverse efforts that contributed to the fight against slavery. Let's honor the courage and solidarity of those who took the southbound path to freedom, and those who assisted them.

•••

Historias Escondidas: El camino hacia la libertad en dirección al sur

Cuando pensamos en la historia de la esclavitud en Texas, Juneteenth o el Día de la Liberación es lo primero que cruza nuestras mentes. Sin embargo, los historiadores Samuel Collins Ill y Dr. Juan Govea, revelan una historia que sucedió muchas décadas antes del Día de la Liberación. Mucho antes de la Proclamación de Emancipación, los abolicionistas hispanos jugaron un papel crucial en ayudar a las personas esclavizadas a escapar hacia México.

En Texas, el Ferrocarril Subterráneo no solo se dirigía al norte, también se dirigía al sur. México, al ilegalizar la esclavitud, le daba la bienvenida a fugitivos esclavizados, ofreciéndoles libertad y ciudadanía.

Este capítulo de la historia de cual no muchos saben, demuestra que las personas esclavizadas no solo estaban esperando a ser rescatadas. Muchos ahorraron por años para pagar por su escape hacia México, demostrando que tenían inmensa determinación y resiliencia.

Los matrimonios entre hombres mexicanos y mujeres africanas esclavizadas, demuestran aún más los lazos profundos y la solidaridad en esta lucha por la libertad.

Algunos de los que encontraron libertad en México, construyeron vidas exitosas. Por ejemplo: uno de los antiguos esclavos de Sam Houston se convirtió en barbero estando en Matamoros, mientras que otro ascendió al rango de oficial en el ejército mexicano.

Estas historias nos desafían a ampliar nuestra comprensión sobre el Ferrocarril Subterráneo y a reconocer los diversos esfuerzos que contribuyeron a la lucha contra la esclavitud. Honremos la valentía y la solidaridad de quienes tomaron el camino del sur hacia la libertad y de quienes los ayudaron.

#black history is everybody's history#historyfacts#black history is world history#black history is american history#black history month#blackhistoryeveryday#blackhistoryyear#blackhistory#blackhistory365#blackhistoryfacts#blackhistorymonth#black history#blackheroesmatter#blacklivesmatter#history#mexico#mexican#spanish#english#español#blackpeoplematter#historia#lasvidasnegrasimportan#knowyourhistory#culture#black history matters#blacklivesalwaysmatter#enslaved#blackbloggers#blackownedandoperated

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

The first conflict to be captured by photography (or, to be precise, daguerreotype) was the Mexican-American War, in 1847. We don’t know who took these first pictures of war, or why.

The images are faded and scratched, but they still give a feel for the war. Here’s American General John Wool’s force in the streets of Saltillo:

And here the photographer captured a sizeable American force resting against a building:

{WHF} {Ko-Fi} {Medium}

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

San Marcos, Guerrero, Mexico, 1962 - by Virgilio Viéitez

#1960s#mexico#Vintage Photo#old photo#sealed in time#historical photo#history photo#photos#history#photography#black and white photography#vintage photography#black and white#black and white photo#history lovers#history in pictures#antique photo#timeless photo

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Frida Kahlo attending a Picasso exhibit in Mexico City, 1944

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

"the US education system didn't teach me about other countries so i didn't realize mexico had modern cities until i was 21" (real reply someone made on a post) is so telling about the general issue with the whole deal about blaming the US education system for everything. like that is just racism. pure, unanalyzed racism and lack of curiosity about the world around you. when people say "unlearn racism and prejudices" this is what they mean--the assumption that mexico hasn't hit the industrial revolution comes from somewhere, and that somewhere is the uncritical acceptance of racist ideas that permeate white america, whether you consider yourself racist or not.

you're right, the US education system does not have required classes that say where major urban centers are, but so what? it betrays an embarrassing lack of curiosity and passivity in your own experience and conception of the world to so freely admit that not only did you never speak to anyone from mexico or think about it hard enough to realize the irrationality of that thought, you passively took in racist ideas about our neighbors and accepted them with ease. did you think all mexicans were involved with drug cartels, too? would you have needed a class in high school to teach you that wasn't true?

so many of the worst example of people saying "but the US education system--" are people using the stilted, slanted historiography the education system perpetuates as an excuse for their own racism. whether that is about mexicans or any other group of nonwhite people that a certain kind of white american believes they could never have conceptualized as full humans without a required high school course on it, a belief they are shockingly willing to admit publicly

#cricket chirps#bit of a rant sorry#YES the us public education system is propagandistic and fundamentally supports the state as an imperial force and argues that the US#is at worst benign and more often a benevolent presence#but like. that by and large comes through in how history classes present the genocide of indigenous peoples or the black panther party#not basic facts about the world like whether mexico city exists. come on

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Xoloitzcuintle is one of the oldest dog breeds on Earth, which the ancient Aztecs considered a guide to the world of the dead.

#l o v e#pet#pets#dog#dogs#mexico#12/2023#google#cute af#my best friend is an animal#aesthetic#x-heesy#xoloitzcuintle#history#disney#naked dogs#Hund#Hunde#style#black#black aesthetic

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

On June 21, 1940, Black Friday debuted in Mexico.

#black friday#black friday 1940#bela lugosi#arthur lubin#horror movies#horror#sci fi#sci fi horror#horror scifi#movie art#art#drawing#movie history#mexico

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pre-Olmec terracotta heads with scarification tattooing…

About 3500 years old…

Located in Xalapa, Mexico

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Imagen del Santuario de Nuestra Señora de los Remedios en la cima de la Gran pirámide de Cholula, en San Pedro Cholula, Puebla, Mexico.

Ca. 1860-1900.

#méxico#retro vintage#mexico#retrostyle#mexican#retro#historia#arquitectura#vintage#historia de méxico#history#mexiko#mexicana#mexicano#mexique#blanco y negro#black and white#film photography#photography#photooftheday#photoshoot#pachuca#puebla#pirámides#piramide#templo

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

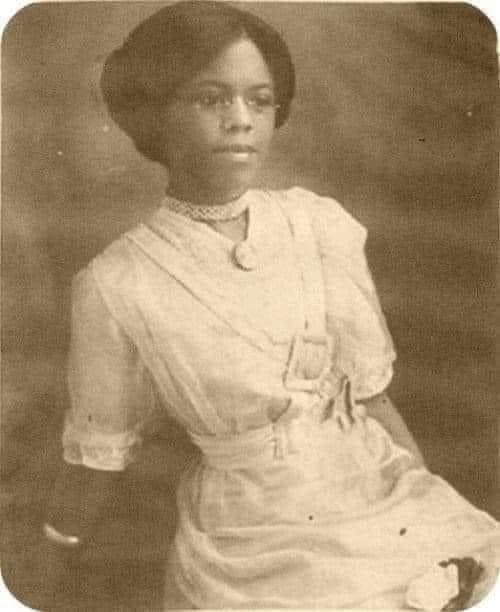

Meet Clara Belle Drisdale Williams [1885-1993], the first African-American graduate of New Mexico State University. Many of her professors would not allow her inside the classroom, she had to take notes from the hallway; she was also not allowed to walk with her class to get her diploma. She married Jasper Williams in 1917; their three sons became physicians. She became a great teacher of black students by day, and by night she taught their parents, former slaves, home economics. In 1961, New Mexico State University named a street on its campus after Williams; in 2005 the building of the English department was renamed Clara Belle Williams Hall. In 1980 Williams was awarded an honorary doctorate of laws degree by NMSU, which also apologized for the treatment she was subjected to as a student. She died at 108 years old.

#Clara Bell Drisdale Williams#black history month#black history#new mexico#New Mexico State University

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

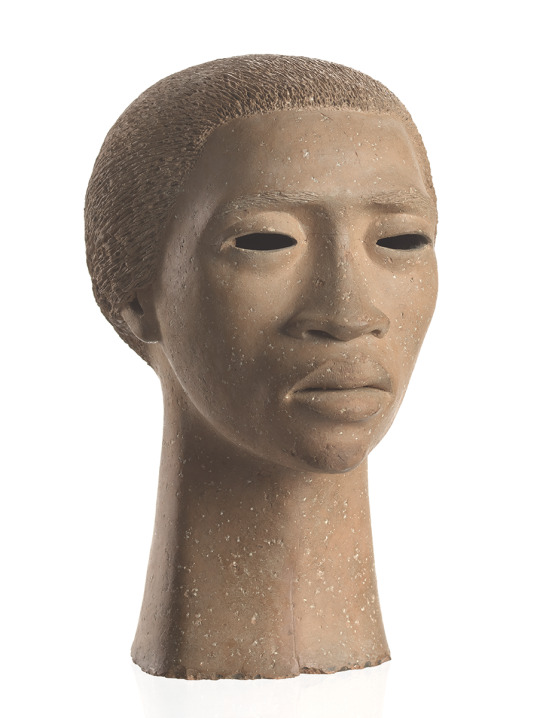

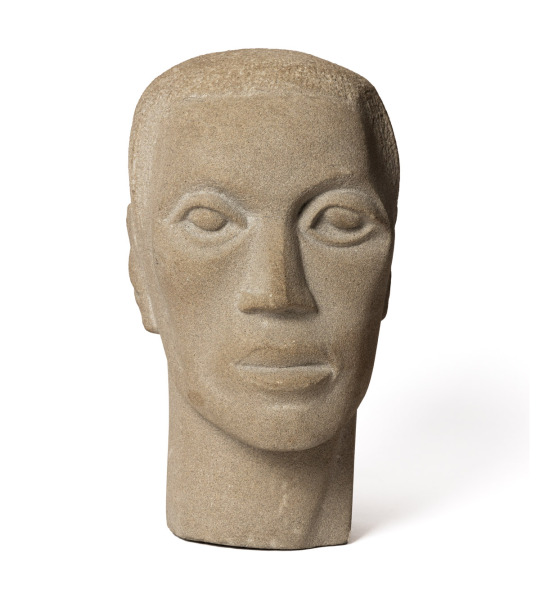

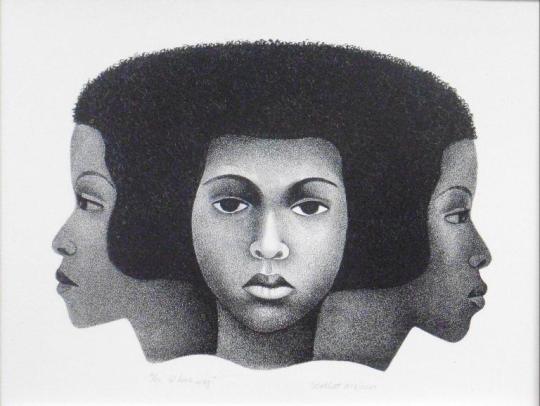

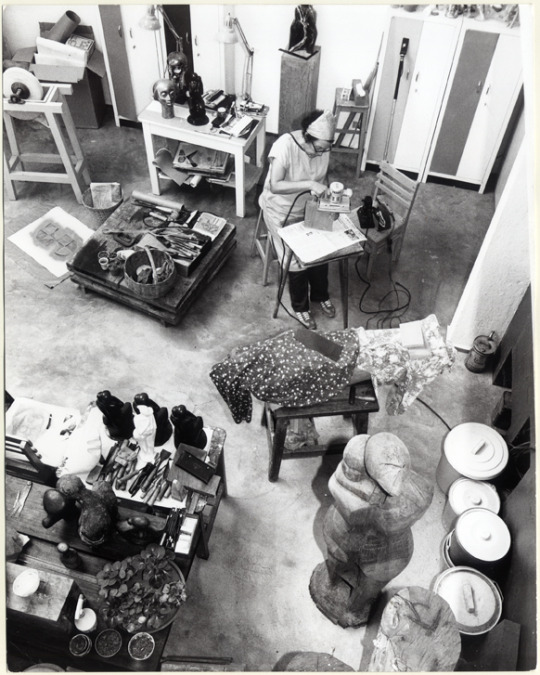

THE ARTIST & HER WORK: ELIZABETH CATLETT

Elizabeth Catlett (1915-2012) lived a storied life. From a young age, she knew she wanted to be an artist, and pursued her dreams by receiving a BA in Art from Howard University in 1935.

She married Charles White (another legacy artist), and together they moved to NYC, where their circle of friends included the likes of Loïs Mailou Jones, Charles Alston, Aaron Douglas, Jacob Lawrence, and Langston Hughes.

In 1946, the pair moved to Mexico, where Catlett was a guest artist at the printmaking collective Taller de Gráfica Popular (TGP). This was a formative time in her practice, as her work became increasingly sociopolitical. She began spending time with Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, and David Siqueiros and was committed to representing strength and struggle in her work. During the Red Scare of the 1950s, her activism and work with TGP came under investigation by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and the U.S. embassy in Mexico. She was declared an "Undesirable Alien" and was prevented from returning to the States. By 2002, her citizenship was reinstated, and she became a celebrated artist around the world. Images:

Charles White. Elizabeth Catlett in her studio. c. 1942. Black-and-white photograph, 3 5/8 × 3 9/16" (9.2 × 9 cm). Private collection. © The Charles White Archives

Elizabeth Catlett (1915–2012), Head of a Negro Woman, 1946 Gift of Robert L. Johnson, © 2020 Catlett Mora Family Trust/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

Elizabeth Catlett, Head. Carved limestone, 1943. Approximately 13 1/2x9 1/2x7 1/4 inches. (sold for $ 485,000 in 2021)

Elizabeth Catlett, "Which Way?," 1973–2003, lithograph, 11 x 14 ½ in. (27.5 x 37 cm), edition 4 of 25. Courtesy of the Elizabeth Catlett Family Trust.

Image of Elizabeth Catlett at work in her studio, circa 1983

#elizabeth catlett#women in art#female artists#20th century art#sculpture#printmaking#photography#charles white#frida khalo#diego rivera#nyc artist#mexico art#art history#black and white#artist studios#artist profile

22 notes

·

View notes