#biography of erich maria remarque

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

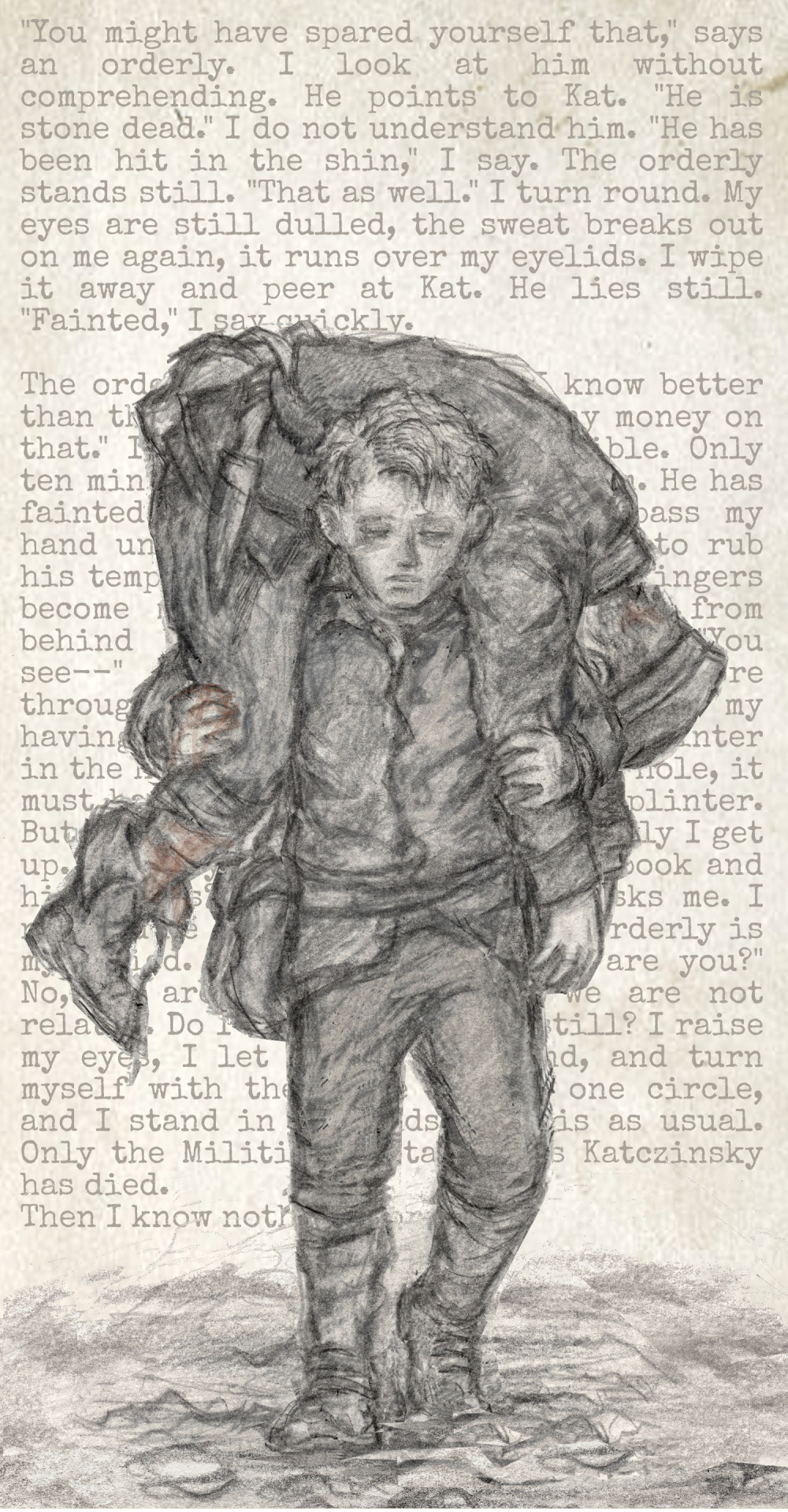

#all quiet on the western front#erich maria remarque#remarque once said that he had to carry a wounded comrade over the shoulders a long way behind the lines to the dressing station#the comrade died days later#this inspired him to write down the last scenes between kat and paul - but kat had to die already on the way unnoticed by paul#because war is arbitrary - with no rules and no happy ends#biography of erich maria remarque#im westen nichts neues#my art#fanart#illustration#AQOTWF#paul bäumer#stanislaus katczinsky#horror of war#kat is such a good character - favourite

239 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tigger has joined his pal Pooh Bear in the land of public domain. The character first appeared in "The House at Pooh Corner," whose copyright expired Monday. Other notable works now in the public domain include J. M. Barrie's "Peter Pan" play, the Hercule Poirot novel "The Mystery of the Blue Train" by Agatha Christie, and the silent film "The Circus" starring and directed by Charlie Chaplin. Also going in is the D.H Lawrence novel "Lady Chatterley's Lover," and the Virginia Woolf novel "Orlando: A Biography." The music and lyrics to Cole Porter's "Let's Do It, Let's Fall in Love" are also now public property. The University of Pennsylvania maintains a digital catalog of U.S. copyright entries to verify if material is available for public use. What major works will lose copyright protection in 2025? Fans of Popeye the Sailor Man will have to wait another year for the opportunity to freely remix the spinach-eating seafarer. Also going public in 2025 are René Magritte's painting "The Treachery of Images," the first Marx Brothers film, and the first English translation of Erich Maria Remarque's "All Quiet on the Western Front."

It's not just Steamboat Willie entering the public domain

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

“This indestructible youth lived another eighty years, outlasting both the Weimar Republic, which he loudly opposed, and the Nazi regime, which he quietly disdained. Germany was split in two, then reunified; Jünger was still there. By the time he died, in 1998, at the age of a hundred and two, he had found a tenuous, solitary place in the German canon. He published more than a dozen volumes of empirically acute but emotionally distant diaries, starting in 1920 with “In Storms of Steel.” He wrote sci-fi-inflected novels, fashioning allegories of the terror state and spinning out prophecies of future technology. And he produced far-right political tracts that have inspired several generations of fascist rhapsodists, antimodern elegists, and élitist libertarians. (Peter Thiel is a fan.) All of this was filtered through a terse, chiselled literary voice—coolly handsome, like the man himself.

The four-year orgy of violence from which Jünger emerged mysteriously intact grants him unimpeachable authority on the subject of war; when he inserts scenes of stomach-churning gore into his fiction, he is not relying on fantasy. Recent reporting on the desperate mind-set of soldiers in Ukraine gives his diaries a haunting currency. At the same time, his mask of insouciance—he was indeed reading “Tristram Shandy” just before a bullet tore through him—makes him an infuriatingly detached witness to the suffering of others. One notorious passage in his journals evokes an Allied air raid on German-occupied Paris, in May, 1944: “I held in my hand a glass of burgundy in which strawberries were floating. The city, with its red towers and domes, was laid out in stupendous beauty, like a calyx overflown by deadly pollination.”

(…) Jünger’s writing gives off an odor of hypermasculine onanism; there are almost no women, and there is almost no sex. Among his more grating qualities is an inability to admit his mistakes: the steely aesthete is also a chameleon, adjusting his positions to the latest political circumstances. But that shiftiness exposes a weaker, more vulnerable figure—and also a more interesting one. His stories generally do not tell of war heroes; rather, they dwell on ambivalent functionaries and complicit observers. We like to think that novelists possess a special ethical strength, yet the morally compromised writer can project a strange kind of honesty—especially when his society is compromised to the same degree.

(…)

The German scholar Helmuth Kiesel, in his 2007 biography of Jünger, observes that the nineteen-year-old soldier exhibited few signs of gung-ho patriotism. His original war diaries, which Kiesel has edited for Klett-Cotta, give a clinical picture of the chaos of battle and the omnipresence of death. When Jünger arrives at the front, at the beginning of 1915, he takes in the destroyed houses, the wasted fields, the rusted harvesting machines, and writes that they add up to a “sad sight.” Later, he asks, “When will this Scheisskrieg”���“shit war”—“have an end?”

Jünger could have gathered these entries into a blistering denunciation of war, preëmpting Erich Maria Remarque’s “All Quiet on the Western Front.” But he had convinced himself that the Scheisskrieg had a higher meaning. As he prepared “In Storms of Steel” for publication, he threw in all manner of sub-Nietzschean soliloquizing and militarist posturing. Senseless brutality was recast as a salutary hardening of the soul. The Scheisskrieg remark was cut, and passages like this set the tone: “In these men there lived an element that underscored the savagery of war while also spiritualizing it: the matter-of-fact joy in danger, the chivalrous urge to fight. Over the course of four years the fire forged an ever purer, ever bolder warriorhood.”

(…)

Nevertheless, Jünger stopped short of direct involvement with the Hitler movement. In his eyes, the Nazis were idiot vulgarians, useful mainly as cannon fodder in the wider assault on democracy. Antisemitism surfaces in his writings, yet Nazi race theory held no interest for him. As Kiesel points out, Jünger rejected the stab-in-the-back legend that blamed Germany’s collapse in 1918 on the skullduggery of leftist, Jewish politicians; he readily admitted that his country had lost to superior forces. You could classify him as a cosmopolitan fascist, one who saw war as essential to the development of any national culture. All the bloodshed served no real political purpose; its ultimate virtue lay in making men into supermen. During the First World War, Jünger had enjoyed occasional courtly chats with English officers, whom he considered equals.

In the mid-twenties, intermediaries sought to arrange a meeting between Jünger and Hitler. Autographed books were exchanged, but no personal encounter took place, apparently for scheduling reasons. Jünger proceeded to browse among extremist alternatives, taking particular interest in Ernst Niekisch’s National Bolshevism. In the essay “Total Mobilization” (1930) and in the treatise “The Worker” (1932), Jünger envisions a fully mechanized totalitarian state in which workers serve as soldierly machines. Spurning the bourgeois ideal of individual liberty, he proposes that “freedom and obedience are identical.” The concept aligns with the anti-liberal thought of Carl Schmitt and Martin Heidegger, both of whom were devoted Jünger readers.

Impeccably fascistic as all this was, the Nazis could not accept any hint of Bolshevism. Furthermore, Jünger had begun ridiculing the Party for its hypocritical participation in the democratic process and for its reliance on gutter antisemitism. Goebbels, who had praised “In Storms of Steel” as the “gospel of war,” now labelled Jünger’s writing “literature”—in his mind, a grave insult. When the Nazis came to power, in 1933, Jünger backed away from public life, refused all official invitations, and buried himself in, yes, literature. In the late twenties, he had published a volume of short prose pieces, titled “The Adventurous Heart,” in which bellicosity still prevailed. In 1938, he issued a drastically revised version of that book, now offering a curious mixture of nature sketches, literary meditations, and dream narratives.

Jünger was a lifelong Francophile, and the revised “Adventurous Heart” is drenched in the decadent visions of Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Huysmans, and Mirbeau. (…)

“Violet Endives” is manifestly ironic—but toward what end? It depicts a society that accepts ghastly events without comment, or with only the twitch of an eyebrow. The narrator himself makes no protest, even if he conveys to us his private unease. His closing remark carries a tinge of arch critique, yet the salesman is free to ignore it. We see the emergence of the mature Jüngerian hero: outwardly bemused, inwardly fearful, terminally uninvolved. This macabre little tale captures in miniature the strategies of rationalization and normalization that make up the banality of evil. As it happens, Hannah Arendt read Jünger closely, and credited him with helping to inspire her most celebrated concept.

(…)

When the Second World War began, Jünger did not exactly disavow the company of the “triumphant and servile.” Resuming military service at the rank of captain, he went to Paris and joined the staff of Otto von Stülpnagel, the general in command of Occupied France. One of Jünger’s duties was to censor mail, although he proved ineffectual at the task, quietly disposing of letters that contained negative remarks about the regime. He also monitored local artists and intellectuals. Picasso inquired about the “real landscape” of “On the Marble Cliffs.” Cocteau, who called Jünger a “silver fox,” gave him a book about opium. Louis-Ferdinand Céline wanted to know why Germans weren’t killing more Jews. Jünger spent his off hours visiting museums, browsing bookstalls, and romancing a Jewish pediatrician named Sophie Ravoux. His wife, Gretha, was back in Germany with their two sons.

Jünger’s Second World War journals were published in 1949, under the peculiar title “Strahlungen,” or “Emanations.” (Thomas and Abby Hansen have translated them into English as “A German Officer in Occupied Paris,” for Columbia University Press.) These diaries are the most stupefying documents in a stupefying œuvre. The episode in which Jünger watches a bombing raid while sipping burgundy has been so widely cited that German critics have given it a name: die Burgunderszene. No less dumbfounding is a passage that recounts, in obscene detail, the execution of a Wehrmacht deserter. Jünger was assigned to lead the proceedings, and, he tells us, he thought of calling in sick. He then rationalizes his participation as a way of insuring that the deed is done humanely. Finally, he admits to feeling morbid curiosity: “I have seen many people die, but never at a predetermined moment.”

(…)

“Emanations” is not all heartless stylization. The book records Jünger’s dawning realization that a new kind of evil had permeated Nazi Germany. (He refers to Hitler by the code word Kniébolo—apparently, a play on “Diabolo.”) When he sees a Jew wearing a yellow star, he is “embarrassed to be in uniform.” When he hears of deportations of Jews, he writes, “Never for a moment may I forget that I am surrounded by unfortunate people who endure the greatest suffering.” And, when precise reports of mass killings in the East reach him, he is “overcome by a loathing for the uniforms, the epaulettes, the medals, the weapons, all the glamour I have loved so much.” Even if none of this is remotely adequate to the reality of the Holocaust—stop everything, Ernst Jünger is embarrassed!—it does show traces of remorse. The émigré writer Joseph Breitbach reported that Jünger had warned Jews of imminent deportations.

Jünger’s façade of disinterest eventually collapsed. In early 1944, his older son, Ernstel, was arrested for saying that Hitler should be hanged. Jünger pulled strings to have him released. Later that year, Ernstel turned eighteen and joined the Army. He died in action in November, 1944, in Italy. For years, Jünger was haunted by the thought that the S.S. had punished him by having his son killed. (There is no evidence that this was so, but the idea was not irrational.) The entries that follow Ernstel’s death are wrenching, although anyone waiting for a grand moral epiphany will be disappointed. It takes a certain kind of grieving father to write, “We stand like cliffs in the silent surf of eternity.”

The second half of Jünger’s immense life was calmer than the first. In West Germany, the ultra-militarist reinvented himself as an almost respectable, and avowedly apolitical, figure. From 1950 on, he lived in Wilflingen, in southern Germany, occupying houses that were lent to him by a distant cousin of Claus von Stauffenberg’s. He kept up his entomological pursuits, building a museum-worthy library of specimens. He dabbled in astrology, explored the occult, and took LSD under the tutelage of Albert Hofmann, who discovered the drug. Telos Press recently published Thomas Friese’s translation of “Approaches,” Jünger’s 1970 drug memoir. His stories of getting high are just as tedious as everyone else’s, but they include unexpected touches, such as quotations from “Soul on Ice,” the autobiography of Eldridge Cleaver.

For many critics, this elder-hipster pose made Jünger all the more dangerous. Although he had retreated from his high-fascist phase, he had not renounced it, and his skepticism toward democracy never wavered. When, in 1982, he received the Goethe Prize, one of Germany’s highest literary honors, left-wing politicians staged furious protests. Helmut Kohl, a Jünger admirer, had just become chancellor, and the veneration of a martial icon was seen as a sign of political regression. Indeed, a stealthily resurgent far-right faction hailed Jünger as a forebear—attention that he did not always welcome. Armin Mohler, a founder of the so-called New Right, served for several years as Jünger’s secretary, but when Mohler criticized his mentor for concealing his archconservative roots Jünger broke off contact for many years.

There is no such thing as an apolitical artist, Thomas Mann once said. The postwar Jünger adhered to a philosophy of radical individualism, which ostensibly bars ideological commitments. In his novel “Eumeswil” (1977), he theorizes a figure called the Anarch, who rejects the state yet also takes no action against it. The book’s narrator, a crafty fixer in service to a tyrant, articulates the ethos: “I am in need of authority, even if I am not a believer in authority.” This is a feeble form of opposition, bordering on the nonexistent, and it is pitted against a generalized conception of the state that elides the huge systemic differences between, say, a republic and a dictatorship. Social-democratic programs are equated with totalitarian control. You can understand Jünger’s appeal to the modern right when you read him complaining, in the 1951 treatise “The Forest Passage,” about liberal health policy: “Is there any real gain in the world of insurance, vaccinations, scrupulous hygiene, and a high average age?” Somehow, Jünger’s fiction avoids being trapped by the poverty of his political thinking. So profound is this writer’s detachment that he manages to remain aloof from his own beliefs.

(…)

Underneath the carapace of Jünger’s writing was an obscurely damaged man. Even before he entered into the torture chamber of the First World War, he had undergone a kind of psychic dissociation, perhaps related to bullying he had suffered as a boy. He wrote of his childhood, “I had invented a mode of indifference that connected me, like a spider, to reality only by an invisible thread.” According to the literary scholar Andreas Huyssen, Jünger was always trying to compensate for the fragility of his own body—to “equip it with an impenetrable armor protecting it against the memory of the traumatic experience of the trenches.”

The Second World War inflicted a different wound, one that cut deeper. The leaders of the plot against Hitler were nationalist conservatives, often fanatically so. The author of “In Storms of Steel” was a hero to them. Jünger’s inability to support their cause, and thereby live up to his own legend, troubled him for the remainder of his life. In “Heliopolis,” Lucius leads a commando raid against a murderous medical institute that recalls Josef Mengele’s laboratory at Auschwitz. The scene reads like a fantasy of what Jünger might have done if he had joined Stauffenberg, Trott zu Solz, and company. Lucius presses a button and the facility goes up in flames: “Dr. Mertens’s highbrow flaying-hut had exploded into atoms and dissolved like a bad dream.”

In “The Glass Bees,” that self-serving fantasy is revoked. As a soldier, Captain Richard witnessed Nazi-like abominations, including a human butcher shop—a nod to the gourmet cannibalism of “Violent Endives.” Yet, when Zapparoni lures him back into the zone of horror, he capitulates. Not only does he need authority; he makes himself believe in it. Zapparoni, he claims, “had captivated the children: they dreamed of him. Behind the fireworks of propaganda, the eulogies of paid scribes, something else existed. Even as a charlatan he was great.”

Jünger described Hitler in similar terms, as a “dreamcatcher,” a malign magician. What might have happened if the two men had come face to face? In a 1946 diary entry, Jünger assures himself that a meeting with Hitler “would presumably have had no particular result.” But he has second thoughts: “Surely it would have brought misfortune.” The ending of “The Glass Bees” may be an imagining of that disaster. As such, it would be Jünger’s most honest confession of failure. When the great test of his life arrived, the warrior-aesthete proved gutless.”

“Could he have moved in another direction? He was an elegant dandy, a ladykiller, a man who could display acute sensibility and lucidity (notwithstanding his obtuseness in large areas), a penetrating observer of human conduct, especially his own. As a schoolboy of fifteen he had spent some time in England, where he was swept off his feet by Carlyle’s On Heroes and Hero-Worship. Indeed, he knew English and English literature well: he translated D. H. Lawrence; he was friendly with Aldous Huxley and wrote about his work. Notoriously, he always followed English sartorial taste. Moreover, he had served as an interpreter with the United States Expeditionary Force in 1917. In contrast, he was not well versed in German.

Drieu went on to Moscow from Germany. It did not take him long to see through the bureaucracy, militarism, and uncontrolled despotism of the Soviet police state. He wondered how French liberal intellectuals could ignore Stalin’s “Asiatic dogmatism,” and he called them guilty men. Here they were, face to face with a flesh and blood hangman, and they worried about “the specter of Fascism,” as he called it. Why did he not realize that his own choice was equally ghastly? As the Latin has it: those whom a god wishes to destroy, he first makes mad. Many reasons have been adduced for this kind of blinkered selective judgment, including self-conceit and weakness, rationalism and anti-rationalism, the desire to be modern and hatred of modernism.

One important element in Drieu was an aesthetic and moral current of emotional responses and notions concerning the decay and death of civilization. This current flows broadly from the nineteenth century, from Carlyle and Nietzsche, to name two of the equivocal forebears deeply admired by Drieu. Moreover, the modern mechanistic forms of destruction employed to such terrible effect in the holocaust of the 1914-18 War, in which he was wounded, left an indelible imprint on Drieu’s sensibility. Surprising as it seems today, Drieu—just like Henry de Montherlant, another exponent of wartime heroism and comradeship—came and went at the Front more or less as it suited him.

The destructive power of the new machinery of war only confirmed in Drieu, as in so many others, the sense that a sick civilization had reached its end. Something new, “a new man,” vital, healthy, strong, heroic, had to be created. The new must necessarily be superior to the old, and certainly it would not be found in outworn liberal parliamentary democracy but in some form of totalitarian regime. For totalitarianism was “the new fact” of the twentieth century, as Drieu was to define it. Even when, under the German Occupation, he finally came to grow disillusioned with Hitler, realizing at last that the Führer had no intention of fostering principles of Fascist “renewal” in France, Drieu’s thoughts would tend to Communism rather than to General de Gaulle.

(…)

Drieu’s response to Hitler’s masterly manipulation of politico-theatrical spectacle was thus rooted not only in the adoration of power and virile health and strength but also in a form of joyous aestheticism. His political commitment to Fascism, to the Parti Populaire Français led by the former Communist working-class demagogue Jacques Doriot (with whom Drieu became disillusioned when he discovered that Doriot was being subsidized by Mussolini), and his later collaboration with the Nazis during the Occupation—these were as much aesthetic as ideological in inspiration. Paul Sérant, in his invaluable study Le Romantisme fasciste, pointed to the aesthetic element in commitment to Fascism. It is an aspect that is often overlooked.

Ever since the serious revival of Drieu’s work and literary reputation in the 1960s, a number of French critics have sought to exonerate him or, at the least, to play down his political “errors.” They have concentrated instead upon his artistic merits and upon his value as an essential witness of his era. A kind of Olympian literary or cultural attitude that only the French seem to be able to carry off with aplomb comes into play here. Besides, the fact that Drieu committed suicide in 1945, after several unsuccessful attempts to do so, has endowed him with the legendary aura of the tragically self-destructive, misunderstood artist, an aura that once fascinated Alfred de Vigny in the young poet Chatterton, and that has continued to exert its spell ever since.

(…)

The sad fact remains that Drieu’s “aesthetic vision” cannot really be separated from his political commitment: the two elements were interconnected and became in- extricably fused. Very loosely, there would appear to be at least two periods in Drieu’s political development, although he was always deeply influenced by thinkers on the Right, by “the anti-Modern, from [Joseph] de Maistre to Péguy,” as he once expressed it, by opponents of capitalism and of liberal parliamentary democracy. One period falls before the notorious right-wing riots of February 6, 1934, which almost overthrew the Third Republic; and the other after that watershed, when he announced that he was a Fascist.

(…)

In the important 1942 preface to his novel Gilles, replying to his critics, Drieu declared: “They did not take the trouble to see the unity of views beneath the diversity of means of expression, chiefly between my novels and my political essays.” He went on: “Some artists think that I have been too concerned with politics in my work and my life. But I have been concerned with everything and with that [politics] also. A great deal of that, because there is a great deal of that in the life of men, at all times, and because all the rest is tied to that.” Despite the clumsily chatty tone, what could be clearer? Professor Reck would have us believe that Drieu cared about art, literature, Paris, and politics “in that order.” He himself contradicts her in the preface to Gilles.

Certainly, there was a time when Drieu put literature first, but it did not endure. If it had, his story might possibly be an entirely different one. As with his politics so with his art, there are very roughly two periods in Drieu’s development. From an aesthetic point of view, the division falls around 1925-29, when he broke with Surrealism, the chief avant-garde literary and artistic movement of the interwar years.

What is his real criticism of the Surrealists in the three open letters addressed to them that he published in 1925, 1927, and 1929? It is that they have become salon revolutionaries who think that dreams and violent words are the same thing as revolutionary action. Worse still, they have deceived him personally by their commitment to Communism. “Surrealism was revelation—not revolution,” he insisted. Wrongly, the Surrealists have abandoned art and artistic independence for politics. How ironic it now seems: at that moment Drieu loudly proclaimed that an intellectual should not join a party. Emmanuel Berl, in his Mort de la Pensée Bourgeoise (1929), favoring the revolutionary stance of Malraux, saw Drieu’s solution then as an endorsement of the theory of art for art’s sake.

(…)

According to Professor Reck, the word “decadence” has fostered a great deal of misguided critical commentary on Drieu’s work. There is, however, no avoiding it, for the idea of decadence is central to both his artistic and his political outlook. He was obsessed by decadence, dreaded it, saw it everywhere, both outside and inside himself. As Frédéric Grover, the distinguished authority on Drieu, once pointed out: Drieu denounced the horror of contemporary civilization, finding decadence in every human activity: religion, art, sex, war, and government. For Drieu, all forms of decadence merge in sexual decadence. This was a theme on which he was an expert, through his two unsuccessful marriages to wealthy young women; his various plans to marry heiresses; his numerous mistresses, including the wife of a United States diplomat; and, throughout his life, his unbroken association with prostitutes.

(…)

What Drieu hated, besides the decadence he acknowledged in himself, was the decadence of others: the supposed materialistic outlook of Americans; the mediocre aspirations of the inferior bourgeoisie; democracy (which favored the mindless herd and, especially, the Jews); the utilitarianism of modern industrial society founded on money instead of on religious faith and on the human relationships that had supposedly prevailed in the agricultural society of the Middle Ages. Drieu was always harping on the virtues of the Middle Ages, boring Victoria Ocampo on this theme, virtues extolled by Carlyle and others. It is curious that admirers of the relations between nobleman and serf always seem to have imagined themselves as aristocrats rather than in the place of those whose existence was nasty, brutish, and short. In fine, Drieu was haunted by decadence as an aesthetic, moral, and political “fact” after the manner of his master, Nietzsche, who confessed to being more concerned with this problem than with any other.

It would be difficult to overstate the theme of decadence in the ethos of writers up to 1945: Drieu was simply an extreme example of its deleterious effects. What nobody seems to have asked—presumably because they were blinded by the metaphor of decadence and by the myth of social health and heroism—was “Who profits from this notion?” Today, it seems only too clear that ideologists of the extreme Left and Right used it and gained immensely from it, by ceaselessly repeating the refrain of the decay of Western civilization and pillorying its values. For Drieu, nothing remained for the individual but to try to create something new “in order not to die.” Having rejected various forms of “renewal” on offer, including the royalism of Charles Maurras and Soviet Communism (because he said he could never be a materialist), he threw himself into Fascism. Why did the solution have to be one of this extreme nature? It was because, in the face of nothingness and decay, totalitarianism appeared to him to be “the new fact” of the twentieth century.

The pressure of left- and right-wing propaganda about bourgeois decadence and the decay of corrupt democratic regimes (hardly contradicted in France by the scandals of the 1930s) impelled Drieu toward political commitment, despite his early advocacy of artistic independence. In his third letter to the Surrealists, he said that he had been accused of “not liking to commit myself.” The more uncertain he was, the more he felt the need for political commitment. Toward the end of his life he said that he settled for an answer in order to stop vacillating. “To live is first of all to commit oneself,” thinks Gilles, who wants to dirty his hands along with the rest of humanity. Drieu even spoke of “the fall into a political destiny” in Socialisme Fasciste. In October 1937, he explained to Victoria Ocampo how “From the moment that I am not a ‘Communist,’ that I am an anti-Communist, I am a Fascist. From the moment I bring grist to the mill of Fascism, I might just as well do it unreservedly.” Not long before he took his own life, he wrote of his regrets: “But I was set on committing myself, more than anything I was afraid of being an intellectual in his ivory tower.” Doubtless, he was far from alone in dreading such a fate. It is not difficult to see how much Sartre learned from Drieu, despite his deep loathing of the man and his actions.

(…)

Drieu wrote out of what was negative in himself. He recognized what he called in Franglais his penchant for “self-dénigrement,” and his masochism. In a remarkable discussion about Drieu with Frédéric Grover in 1959 (published in La Revue des Lettres Modernes in 1972), André Malraux spoke of this tendency in his friend. According to Malraux, Drieu was far from being the negative personage he projected in his writings. On the contrary, claimed Malraux, he dominated any gathering of leading intellectuals by his “astonishing presence” and charisma. It would seem to be essential to any discussion of Drieu’s work and attitudes to try to embrace his psychological make-up and its effect on his precarious balancing act between dreams, art, and action.

(…)

Drieu’s argument in that essay is not peculiar to his concept of pictorial art: it is, in essence, quite familiar from other writings of his about general modern decay, including his articles on circus, music hall, and theater, explored by Professor Reck. Up to 1750, Drieu asserts, man is still a solid being, as depicted by Watteau. Indeed, Drieu even finds assurance in Watteau, one of the most mysterious and enigmatic of eighteenth-century painters. What vigor, health, certainty, equilibrium, are to be found in Watteau’s Gilles! exclaims Drieu, who invites us to compare this figure with the man of 1830, completely ravaged by the rationalism of the Enlightenment and all its attendant ills. The mysticism of the Middle Ages (Drieu’s King Charles’s head or, as the French say, Ingres’s violin) has not entirely departed from Watteau’s Gilles, who still shows signs of a virility that was soon to depart. In short, Drieu’s account of Watteau’s painting cannot be separated from his views on universal modern decadence, views which lie at the core of his political stance also.

(…)

If there is a connection to be made between literary and painterly techniques—and so far I am not convinced that there is—it would have to be examined with the most scrupulous tact, with strict reference to the available evidence (and no straying beyond it), evidence considered in relation to the writer’s imagination and mental outlook as a whole. Drieu stressed the unity of his work, and there is no reason to doubt his own word in this regard. Whatever one may think of him as a human being or as a talent, he is so candid a representative of the negative and nihilistic aspects of his age that he merits no less than critical rigor tempered with justice.”

#junger#jünger#ernst jünger#drieu la rochelle#pierre drieu la rochelle#fascism#fascist#germany#vichy#france#wwi#world war one#wwii#world war 2#literature#art

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yes yes yes, everyone read unknown soldier! There is an english translation and also one of the extended book in German (Kriegsroman). Such amazing characters, and I love väinö linnas dark humor (:

I'll also add my favorite author, Erich Maria Remarque, his most famous and most influential book is im Westen nichts neues/ all quiet on the western front, amazing first world war book! He also has some very good ones about emmigration/ refugees during the Nazi regime and my favorite book of his, der Funke Leben about a concentration camp. Remarques books are heavy but always great and thought provoking reads!

And to go very classic: ancient Roman authors can be surprisingly fun, suetons biographies of Roman emperors are hilariously weird 😂 if even half of that is true they had some really horrible leaders 😂

Also boccaccios decameron, people telling raunchy stories to pass time during quarantine was unfortunately very relatable not too long ago 🙈😂

Please, please add your own to this! Especially non-English books because my knowledge is very European-centric.

465 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm glad to know you're well, you deserve the best 😌😌😌; I'm not so well but it will pass by <3

Oh my! Oscar Wilde and Haruki Murakami are my top favourite as well 💜 I've read whatever I could find by them but "Norwegian Wood" and "Sputnik Sweetheart" remain my favourite works by Murakami. As for Wilde, I really can't choose. I love all his works and he holds a special place in my heart because he wrote about some very bad things that happened in my country. The same goes for Victor Hugo as well, another favourite author of mine. Erich Maria Remarque, Stefan Zweig (I highly recommend you his works), Mikhail Bulgakov, Jane Austen, Edgar Allan Poe, Arthur Conan Doyle, Isaac Asimov; Yordan Yovkov, Peyo Yavorov, Nikola Vaptsarov, Aleko Konstantinov (they are from my country) are also my favourites. I have a lot of favourite books and writers tbh 😂 but I should mention the book that shattered me (literally) and helped me survive high school: "The Perks of Being A Wallflower". As for genres, I love reading different things, apart from horror, overly romantic books and (auto) biographies, wow 😂 but still, there are exceptions.

I will definitely read this book 😌. Thank you for the recommendation and for sharing your thoughts 💜

Oh, baby, I hope you can feel better soon 🥺 Please, be safe and healthy because you deserve the best too ❤️

Girl, I love your taste hehe. I think I might all (or, at least, most) of Murakami's books and Sputnik sweetheart is so precious to me as well 💕 And it's really hard to choose a favorite book from Wilde, some of them simply touch our heart ❤️

I'll surely take note of all those authors and read something from them, because, you know, literature is life 🥰 And I'm also very eclectic (including horror stories haha), but romances always have a special spot in my heart that I can't ignore 💞

Thank you for sharing these beautiful recommendations, baby. I'll put them on my endless list ❤️😘

1 note

·

View note

Note

hi! it is i, your substitute secret santa :D

how have you been lately, fellow hooman? i hope you’re doing well! today, i would like to ask you about a subject i feel like you’re quite familiar with - history. tell me all about it. what’s your favourite era? who are your favourite historical figures? what history-related person/thing do you absolutely despise? rant if you’d like :D

i’m wishing you a great weekend in advance!

~ secret santa

hello fellow anonymous hoomannn! at first i want to thank you so much for being my subsitute secret santa! i was so happy to participate in this event and then really sad when my secret santa chose not to interact with me :( i hope theyre ok tho!

im quite ok thanks :) i have a buch of christmas cards here that i need to send off later ! hru?

OMG I LOVE YOU ALREADY yeah history is one of my passions, let it be music history, literature history, political history , earth history IM INTO IT ALL (and i guess its pretty obvious)

favourite era: i have always loved the late victorian era and edwardian era although if i had to pick i´d chose the edwardian era + the last few years before ww1:) (1900-1914), but i also like the late 50s and early 60s (1955-1966) because that was the beatnik mod subculture jazzy underground youth culture movement counterculture era (wow what a word) :D

in general im interested in modern history more than in ancient ( i love the ancient romans and greeks tho, since i had latin in school) so what gets me passionate is basically 1800s until today

fav historical figures: ok ill give you my top 5 plus a short description HIHI

cecil henry meares (1878-1936): traveller, adventurer, linguist, polar explorer

victoria mary of teck (1867-1952), later queen mary: queen consort of george v (i also like her husband king george v alot btw)

martin luther king jr (1929-1968): pacifist and civil rights movement leader

erich maria remarque (1898-1970): author and pacifist

rosa luxemburg (1871-1919) :anti nationalist politician in post ww1 germany

i havent done perfect research on all of them yet BUT these are the persons that interest me the most currently! ive done a presentation on MLK for my italian class and am currently reading a book about remarque´s political opinions connected to his literary work and am looking for a biography of queen mary :) so yeah! (OH i also made a long post about cecil meares here)

historical things i despise is of course anything history related form of discrimation like racism, homophobia, transphobia, sexism and so on, BUT i do think its important to learn about it so we can avoid it in the future! and hmmm i have a few historical persons i dislike but i dont really have one i completely despise?? anyone who is mean to my faves is of course on the “not nice at all”-list.

like georges v sisters who bullied mary bc she had not 100% royal blood and they said she had ugly hands and was dull (although she was probably the most intellegent woman the british royal family ever had in their circles)

and otherwise yeah the usual people: hitler, donald trump, napoelon, and y know who i mean... all the terrible people this earth sadly had as its inhabitants:/

wow this is long! how about you??? :) do you like history? and what do you like the most about it? <3<3<3<3<3<3

thank you so much again im crying ;;

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

I am sure you have responded to this question before, but could you list your favorite WWI poems and favorite WWI novels. Memoirs, too, please. Thank you for this beautiful blog!

Hi, I’m happy to hear that you enjoy this blog ;)

Here are some of my favourite WWI poems:

“The Last Meeting” by Siegfried Sassoon

“Banishment” by Siegfried Sassoon

“Prelude: The Troops” by Siegfried Sassoon

“Before the Battle” by Siegfried Sassoon

“At Daybreak” by Siegfried Sassoon

“The Death Bed” by Siegfried Sassoon

“Suicide in the Trenches” by Siegfried Sassoon

“The Dug-Out” by Siegfried Sassoon

“Before Day” by Siegfried Sassoon

“When I’m among a Blaze of Lights“ by Siegfried Sassoon

“Strange Meeting” by Wilfred Owen

“Wild with All Regrets” by Wilfred Owen

“Dulce et Decorum Est” by Wilfred Owen

“Anthem for Doomed Youth” by Wilfred Owen

“The Unreturning” by Wilfred Owen

“Futility” by Wilfred Owen

“To Germany” by Charles Hamilton Sorley

“When You See Millions of the Mouthless Dead” by Charles Hamilton Sorley

“Such, Such is Death” by Charles Hamilton Sorley

“Two Fusiliers” by Robert Graves

“Sorley’s Weather” by Robert Graves

“The Shadow of Death” by Robert Graves

“Letter to S. S. from Mametz Wood“ by Robert Graves

“The Next War” by Robert Graves

Some novels / memoirs / plays / diaries / letters that I recommend:

Barker, Pat. The Regeneration trilogy

Brittain, Vera. Testament of Youth

Brodrick, William. A Whispered Name

Chevallier, Gabriel. Fear: A Novel of World War I

Faulks, Sebastian. Birdsong

Graves, Robert. Goodbye to All That

Hill, Susan. Strange Meeting

Johnston, Jennifer. How Many Miles to Babylon?

MacDonald, Stephen. Not About Heroes

Montgomery, L. M.. Rilla of Ingleside

O’Neill, Jamie. At Swim, Two Boys

Owen, Wilfred. Selected Letters

Remarque, Erich Maria. All Quiet on the Western Front

Sassoon, Siegfried. Diaries, 1915-1918.

Sassoon, Siegfried. Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man

Sassoon, Siegfried. Memoirs of an Infantry Officer

Sassoon, Siegfried. Sherston’s Progress

Sassoon, Siegfried. Siegfried’s Journey, 1916-20

Sorley, Charles Hamilton. The Letters of Charles Sorley, with a Chapter of Biography

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

My ‘To read’ book list

Everyone seemed to like my ‘to watch’ list of movies so I decided to share my list of books I want to read!

📚 Fantasy

Harry Potter and the Cursed Child J. K. Rowling 5/10

Eon: Dragoneye Reborn Alison Goodman

Eona: The Last Dragoneye Alison Goodman

The Unbound Victoria Schwab 8/10

The Diabolic S. J. Kincaid 9/10

Kaziměsti Martin Bečan 10/10

Hvězdopravec Martin Bečan

Ink Alice Broadway 7/10

Spark Alice Broadway

Strange the Dreamer Laini Taylor 7/10

The Ruins of Gorlan John Flanagan 8/10

The Burning Bridge John Flanagan 8/10

The Icebound Land John Flanagan 6/10

Oakleaf Bearers John Flanagan

Game of Thrones George R. R. Martin 9/10

A Clash of Kings George R. R. Martin

The Hobbit J. R. R. Tolkien 8/10

Lord of the Rings: Fellowship of the Ring J. R. R. Tolkien

The Last Wish Andrzej Sapkowski

Animal Farm George Orwell 9/10

The Colour of Magic Terry Pratchett

Good Omens Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman 7/10

Neverwhere Neil Gaiman 9/10

American Gods Neil Gaiman

Metamorphosis Franz Kafka 6/10

The Pied Piper Victor Dyk 8/10

Nikola the Outlaw Ivan Olbracht 5/10

Shadow and Bone Leigh Bardugo

The Fork, the Witch, and the Worm Christopher Paolini

To Sleep in a Sea of Stars Christopher Paolini

Rozhněvané Malé Děti Zašek

Percy Jackson & the Olympians: The Lightning Thief Rick Riordan

The Priory of the Orange Tree Samantha Shannon 9/10

The Song of Achilles Madelaine Miller

The Midnight Library Matt Haig

Iron Widow Xiran Jay Zhao

A Court of Thorns and Roses Sarah J. Maas

Throne of Glass Sarah J. Maas

Piranesi Susanna Clark

📚 Sci-Fi

Annihilation Jeff VanderMeer 8/10

Rebels of Eternity Gerd Ruebenstrunk 6/10

Genius: The Game Leopoldo Gout 5/10

The Power Naomi Alderman 9/10

Metro 2033 Dmitry Glukhovsky 10/10

Metro 2034 Dmitry Glukhovsky

Fahrenheit 451 Ray Bradbury 7/10

Authority Jeff VanderMeer

Acceptance Jeff VanderMeer

The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes Suzanne Collins

1984 George Orwell 9/10

R.U.R Karel Čapek 6/10

An Absolutely Remarkable Thing Hang Green

Scythe Neal Shusterman

The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy Douglas Adams

📚 Biography

The Wisdom of Wolves Elli H. Radinger 7/10

Talking as Fast as I can Lauren Graham 6/10

📚 Thriller/horror

The Girl on the Train Paula Hawkins 8/10

Pet Semetary Stephen King 7/10

Doctor Sleep Stephen King 8/10

Angels and Demons Dan Brown

The Bat Jo Nesbø

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo Stieg Larsson

You'll Be the Death of Me Karen McManus

📚 Humor

If the Impressionists Had Been Dentists Woody Allen 8/10

Saturnin Zdeněk Jirotka 8/10

📚 Realistic fiction and classic novels

Turtles All the Way Down John Green 8/10

Paper Towns John Green

Norwegian Wood Haruki Murakami

Sherlock Holmes: Classic Stories Arthur Conan Doyle

Anne of Green Gables Lucy Maud Montgomery

The Secret Garden Hodgson Burnett

A Good Girl's Guide to Murder Holly Jackson

The Blackbird Girls Anne Blankman

They Both Die at the End Adam Silvera

📚 Classic Novels

The Mother Karel Čapek

Great Gatsby Francis Scott Fitzgerald 6/10

The Call of the Wild Jack London 9/10

Bâtard Jack London

To Kill a Mockingbird Harper Lee 6/10

Pride and Prejudice Jane Austen

Robinson Crusoe Daniel Dafoe

Moby Dick Christopher Chabouté, Herman Melville 5/10

Three Comrades Erich Maria Remarque 8/10

The White Disease Karel Čapek 6/10

📚 Personal Growth and Education

You are a Badass Jen Sincero 7/10

The Subtle Art of Not Giving a Fuck Mark Manson 2/10

The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Marie Kondo 7/10

The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy Living Meik Wiking 5/10

7 Habits of Highly Effective People Stephen Covey 0/10

The science of staying well Dr Jenna Macciochi 8/10

Atomic Habits James Clear

The Four Agreements Miguel Ángel Ruiz

A Brief History of Time Stephen Hawking

The Anthropocene reviewed John Green

#the-diary-of-a-failure#studyblr#lifestyle blog#books#reading#literature#to read list#inspiration#recommendation#personal

119 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey man, I just wanted to say two things. First, don't let the angry anon asks get you down. I can't say for certain, but I think the majority of the community is in your corner about Hi-Evo. I'm severely disappointed with what we've gotten and we deserve better. Secondly, I think you're a great author and I hope you get published one day. I'd definitely read your work if I could. Incidentally, what were some of your literary influences while writing the Historical series?

It’s great to hear you say that. :) I knew there were others who thought the same as me, but it’s always reassuring to get asks and messages telling me I’m not alone in the matter. And yes, we deserved so much better. Bones just missed a prime opportunity with Hi-Evolution, and thinking about it just makes me beyond sad.

Thank you very much! Publishing efforts are on hold right now until I’m more settled into my new job, but rest assured that I’m not giving up. One way or another, all of these stories will be published, and you all will be the first to hear about it. :)

As for literary influences of the Historicals, there were quite a few. A lot of what I wrote was based on soldiers’ memoirs and journals during World War II, both from the Axis and Allied sides. The accounts of the Russian war correspondent Vassily Grossman were particularly insightful, as was his novel Life and Fate. It’s a great book set during the Battle of Stalingrad, and one I highly recommend reading.

There were some other fictional sources I used to help my writing as well. All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque was rather seminal in crafting the story, and especially in how he pushed his anti-war, pacifistic message. I admire Remarque’s work because he showed the horror of war by just describing what soldiers saw and felt rather than just tell us “war is bad” straight up. It’s a subtle form of storytelling I wish more books (and anime) employed.

David McCullough’s writings have also been a big influence, since he looks at history as the experiences of people rather than massive events. If you want an example of how to write engaging nonfiction, definitely check out his biographies. I touched on this in a blog I wrote on wordpress, but McCullough understands how history is about people. That’s key to making history relatable.

I could easily write more about my influences, but I’d be here all night. XD

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

recs for world war one lit?

Sure thing! I studied WWI lit at uni and nowadays I read a fair bit of historical fiction set in that period, so here’s a mixed list (including ones I’ve yet to read):

Biographies:

Goodbye To All That (1929) by Robert Graves

Undertones of War (1928) by Edmund Blunden

Testament of Youth (1933) by Vera Brittain

Wilfred Owen (2015) by Guy Cuthbertson

First World War Poets (2014) by Alan Judd & David Crane

Siegfried Sassoon: Soldier, Poet, Lover, Friend (2013) by Jean Moorcroft Wilson

Novels written soon after WWI (20s-30s):

All Quiet On The Western Front (1929) by Erich Maria Remarque

The Road Back (1931) by Erich Maria Remarque

Fear (1930) by Gabriel Chevallier

Not So Quiet: Stepdaughters of War (1930) by Evadne Price (as Helen Zenna Smith)

Memoirs of an Infantry Officer (1930) by Siegfried Sassoon

Novels written later (late 20th century-now):

The Regeneration Trilogy (1991-1995) by Pat Barker (Regeneration, The Eye in the Door, The Ghost Road)

How Many Miles to Babylon? (1974) by Jennifer Johnston

A Month In The Country (1980) by J.L. Carr (set in the aftermath of WWI)

The Absolutist (2011) by John Boyne

Strange Meeting (1971) by Susan Hill

The Lie (2014) by Helen Dunmore

Things A Bright Girl Can Do (2017) by Sally Nicholls (more about the Suffrage movement but WWI features in it)

Plays:

Journey’s End (1928) by R.C. Sherriff

Not About Heroes (1982) by Stephen MacDonald

‘The Man on the Platform’ monologue from Queers (2017) by Mark Gatiss

Poets:

Wilfred Owen

Siegfried Sassoon

David Jones

Edmund Blunden

Robert Graves

Rupert Brooke

Ivor Gurney

Isaac Rosenberg

39 notes

·

View notes

Link

Erich Maria Remarque Biography in Hindi 16 साल की उम्र में, रिमार्के ने लेखन में अपना पहला प्रयास किया था; इसमें निबंध, कविताएँ और एक उपन्यास की शुरुआत शामिल थी जिसे बाद में समाप्त किया गया और 1920 में द ड्रीम रूम (डाई ट्रम्ब) के रूप में प्रकाशित किया गया। जब उन्होंने पश्चिमी मोर्चे पर ऑल क्वाइ�� प्रकाशित किया, तो रेमारक ने अपनी मां की याद में अपना मध्य नाम बदल दिया और अपने उपन्यास डाई ट्रंबुडे से खुद को अलग करने के लिए परिवार के नाम की पहले की वर्तनी पर वापस लौट आए। मूल परिवार का नाम, रेमारक, 19 वीं शताब्दी में अपने दादा द्वारा रीमार्क में बदल दिया गया था। 1927 में, रिमार्के ने क्षितिज (स्टेशन एम हॉरिज़ॉन्टल) में उपन्यास स्टेशन के साथ एक दूसरी साहित्यिक शुरुआत की, जिसे स्पोर्ट्स जर्नल स्पोर्ट आईएम बिल्ड में सीरियल किया गया था जिसके लिए रेमारक काम कर रहे थे। यह केवल 1998 form में पुस्तक के रूप में प्रकाशित हुआ था। सभी शांत पश्चिमी मोर्चे (Im Westen nichts Neues) पर 1927 में लिखा गया था, लेकिन रेमारक तुरंत एक प्रकाशक को खोजने में सक्षम नहीं थे। 1929 में प्रकाशित उपन्यास में प्रथम विश्व युद्ध के दौरान जर्मन सैनिकों के अनुभवों का वर्णन किया गया था। सरल, भावनात्मक भाषा में उन्होंने युद्धकाल और युद्ध के बाद के वर्षों का वर्णन किया है।(Erich Maria Remarque Biography in Hindi) एरिक मारिया रिमार्के, उपन्यासकार हैं, जिन्हें मुख्य रूप से इम वेस्टन निचेस न्यूज़ (1929) के लेखक के रूप में याद किया जाता है। पश्चिमी मोर्चे पर सभी शांत), जो शायद प्रथम विश्व युद्ध से निपटने वाला सबसे प्रसिद्ध और सबसे प्रतिनिधि उपन्यास बन गया।18 साल की उम्र में रिमार्क को जर्मन सेना में शामिल किया गया था और कई बार घायल हो गया था। युद्ध के बाद उन्होंने पश्चिमी मोर्चे पर ऑल क्वाइट पर काम करते हुए एक रेसिंग-कार चालक के रूप में और एक खिलाड़ी के रूप में काम किया। उपन्यास की घटनाएँ उन सैनिकों की दैनिक दिनचर्या में शामिल हैं जिनके बारे में लगता है कि खाइयों में उनके जीवन के अलावा कोई अतीत या भविष्य नहीं है। इसका शीर्षक, रूटीन कम्यूनिकेस की भाषा, इसकी शांत, सुरीली शैली की खासियत है, जो युद्ध के दैनिक भयावहता को लेकेनिक समझ में दर्ज करती है। इसकी आकस्मिक अमरता देशभक्ति की बयानबाजी के विपरीत थी। पुस्तक एक तत्काल अंतर्राष्ट्रीय सफलता थी, जैसा कि 1930 में अमेरिकी फिल्म ने बनाया था। इसके बाद एक अगली कड़ी, डेर वेग ज्यूरक (1931; द रोड बैक), 1918 में जर्मनी के पतन के साथ काम कर रही थी। रेमर्क ने एक दूसरे को लिखा था। उपन्यास, उनमें से अधिकांश विश्व युद्धों I और II के दौरान यूरोप की राजनीतिक उथल-पुथल के शिकार लोगों से निपटते हैं। कुछ को लोकप्रिय सफलता मिली और उन्हें फिल्माया गया (जैसे, आर्क डी ट्रायम्फ, 1946), लेकिन किसी ने भी उनकी पहली पुस्तक की महत्वपूर्ण प्रतिष्ठा हासिल नहीं की। 1929 में प्रकाशित, पश्चिमी मोर्चे पर ऑल क्विट रिमार्क का सबसे प्रसिद्ध काम था। दिलचस्प बात यह है कि इसे प्रकाशित करने के लिए कंपनी खोजने में उसे लगभग दो साल लग गए। यह उपन्यास प्रथम विश्व युद्ध के दौरान जर्मन सैनिकों की चुनौतियों का सामना करता है और जब वे घर लौटते हैं। इनमें से कई चुनौतियां आज भी हमारे सैनिकों का सामना कर रही हैं। पॉल बाउमर एक युवा व्यक्ति है जो जर्मन सेना में शामिल होने का फैसला करता है और जल्द ही पश्चिमी मोर्चे पर डाल दिया जाता है, जो खाई युद्ध था। खाई युद्ध की स्थिति भयानक थी। पॉल एक सैनिक के रूप में अपने समय के दौरान भय, चिंता और अवसाद से जूझता है। अनिवार्य रूप से, यह कहानी उन सैनिकों के बारे में है जिन्होंने युद्ध में अपने भयावह अनुभवों के आधार पर अपना 'जीवन' खो दिया। घर आने पर वे कभी भी एक समान नहीं होते हैं। सभी मोर्चे पर शांत, 1930 में लिखित द रोड बैक नामक एक सीक्वल है। Erich Maria Remarque Biography Erich Maria Remarque Erich Maria Remarque history Erich Maria Remarque book Erich Maria Remarque movie Erich Maria Remarque hindi about Erich Maria Remarque

0 notes

Text

Get to Know the Bookworm Tag

Tagged by @anassarhenisch. Thank you a lot!

Rules!

1. Answer Everything

2. Tag at least 5 people

3. Use the tag #cherrysbookwormtag

4. I don’t want to bother anyone, if you don’t wanna do it, don’t do it!

Here we go!!

1. What’s your name? Auguste

2. How old are you? turned 15 four days ago.

3. Your eye color? Green.

4. Your natural hair color? dirty blonde/ brown.

5. Your current hair color? Undyed.

6. Where do you live? Lithuania, Europe.

7. Do you have pets? I have a dog.

8. Favorite song at the time? Heartbreak by Childish Gambino.

Let’s Get Bookish

1. Favorite book of all time? Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy.

2. Favorite book series? Robert Langdon book series.

3. Explain why you love books in 3 words. Distraction, learning, calming.

4. Favorite fictional character (Female)? Scarlett O’Hara.

5. Favorite fictional character (Male)? Robert Langdon (duh).

6. Favorite fictional character (anything else)? Billy Piligrim.

7. A book that broke your heart? Three Comrades by Erich Maria Remarque

8. A book everyone loves but you don’t? The Diary Of a Young Girl by Anne Frank

9. Favorite genre? sci-fi, romance, biography, adventure.

10. Favorite author? Dan Brown

11. Currently reading? 1984 by George Orwell

12. How long is your TBR list? VERY LONG

Pick!

1. Chocolate or Chips? chocolate.

2. The book or the movie? book.

3. Reading a book or hearing an audiobook? reading.

4. TV or YouTube? youtube, but I love TV too.

5. Smartphone or Laptop? smatphone

6. Hardcover or Paperback? hardcover.

Tagging 3 random bookish follows: @bookclubaddict @bookishgr @bookloverpullover

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Timeless Love: THREE COMRADES (’38) by R. Emmet Sweeney

THREE COMRADES brought together an improbable confluence of talent, all trying to find a way to work around the implacable censoriousness of the Hollywood system. Based on an Erich Maria Remarque novel, adapted into a screenplay by F. Scott Fitzgerald and directed by Frank Borzage, it tells the story of a trio of traumatized WWI vets and how a transcendent, tragic romance brings hope and happiness back into their lives. It had the inopportune fate to be a German story when MGM was still courting that market despite the ascendancy of the Nazi party. All political elements had to be scrubbed and the film okayed by German diplomats. And yet Borzage found a way to work around these constraints to build a film of trembling beauty, positing love as a force not bound by time or space.

The idea to adapt Remarque’s 1936 novel of the same name came from Charles Boyer. In his Frank Borzage biography Hervé Dumont relates that between takes on HISTORY IS MADE AT NIGHT (’37) Boyer urged the director to read Remarque’s latest book. Ominously, the most recent adaptation of Remarque’s novels, James Whale’s THE ROAD BACK (’37) was re-edited and partially re-shot to address complaints of the German consul Georg Gyssling. Three Comrades was optioned for a feature before it was even published, as the glow of ALL QUIET ON THE WESTERN FRONT (’30), also adapted from Remarque’s work, still shone in executives’ eyes.

F. Scott Fitzgerald was brought in to write a script after rejected attempts by British playwright R.C. Sherriff. Executive producer Joseph Mankiewicz hired Fitzgerald because “Scott was one of my idols. I hired him personally for this film, and had to fight, while everyone in the studio said he was finished; why take a risk with him?” Fitzgerald’s alcoholism had torpedoed his Hollywood reputation, and Mankiewicz was unable to insulate him for executive meddling. According to Dumont, Louie B. Mayer’s fixer Eddie Mannix “forced Mankiewicz to go back on his word by imposing Edward E. Paramore as co-scriptwriter.” Others would secretly do polishes, including Lawrence Hazard and poet David Hertz. Fitzgerald would write to his producer, “Can’t producers ever be wrong? Oh Joe! I’m a good writer, honest!” Dumont estimates that “only a third” of Fitzgerald’s script appears in the completed film.

Borzage was a natural choice considering his familiarity with the novel. The two main stars were initially set to be Spencer Tracy and Luise Rainer, who had just acted in Borzage’s BIG CITY (’37), but they dropped out, replaced by Robert Taylor and Margaret Sullavan. Taylor plays Erich Lohkamp, a WWI vet who starts up an auto repair shop in Germany with his war buddies Otto (Franchot Tone) and Gottfried (Robert Young). All are reluctant to fully re-enter civilian life, but soon Erich is entranced by Patricia (Sullavan), a once-rich socialite now nearly destitute after the death of her parents. Bewitched by her carefree nature, Erich allows himself to enter back into society. What Patricia doesn’t reveal, however, is her terminal disease. Not wanting to ruin the dream of their love, Patricia keeps Erich in the dark until her sickness makes it impossible. With the help of Otto and Gottfried, who form a makeshift family and support system, they try to nurse Patricia back to health.

But some wounds cannot heal, and Patricia tries to prepare Erich for the possibility of her death. “We love each other beyond time and place now,” she tells him. Their bond extends beyond what is visible, into the unknown. What is effaced are the anonymous irruptions of violence in the city, meted out by violent gangs that are never identified, though they are very obviously stand-ins for the Nazis. Gottfried is the political one of the group, and he helps a street preacher out from imminent mob violence, only to be gunned down by a callow looking blond youth. Fitzgerald wanted to end the film with Erich and Otto returning to Berlin to “enter the struggle against the evil force that is now engulfing their fatherland.” This gave MGM the vapors, since Gyssling (who had initiated the gutting of THE ROAD BACK) had been complaining to Joseph Breen of the Production Code Administration about the project, indicating it would incite protests from German-Americans and would “definitely be banned in Germany and Italy.” Breen would suggest to MGM that they indicate that the gang violence was initiated by Communists, to salve the hurt Nazi ego. They didn’t take this drastic action (which Mankiewicz strongly objected to), but they were forced to move the timeline of the film from 1928 back to 1920, placing it before the rise of Nazism.

It is remarkable that THREE COMRADES remains as coherent as it is considering the amount of upheaval that occurred during pre-production. And production wasn’t smooth sailing either, what with legendary DP Karl Freund (DRACULA [’31]) getting fired after two weeks, replaced by Joseph Ruttenberg (GIGI [’58], MRS. MINIVER [’42], GASLIGHT [’44]). Borzage had to shoot Germany as non-Germany, with no identifying marks, so it comes off as a series of generic Hollywood backlots, not that the casting would have added much of a Germanic flair, what with all-American Robert Taylor and Margaret Sullavan as the central figures, their aw-shucks demeanor more suited to Boise than Berlin.

But somehow all this de-localizing allows Borzage the room to emphasize his theme of a transcendent love. It doesn’t matter the specific time or place – for these characters this is a love that will outlive all of them. They cling to it like sailors on a sinking ship. With no hope in their country their business or themselves, they throw all their belief into the bond between Erich and Patricia. Through radiant close-ups Borzage abstracts them from their city and inscribes them into a plane of pure emotion. In any other filmmaker’s hands such material would become laughable, but with Borzage’s completely unselfconscious treatment, it becomes sublime. In the ecstatic final sequence, Sullavan stares up with religious intensity, her tone calm and firm: “It’s right for me to die, darling. It isn’t hard. And I’m so full of love.” For the three comrades and Patricia, death is not the end, just an extension of their bond into the unknown.

#FilmStruck#Frank Borzage#F. Scott Fitzgerald#Three Comrades#Robert Taylor#Franchot Tone#Margaret Sullavan#Robert Young#StreamLine Blog#R. Emmet Sweeney

26 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Photo

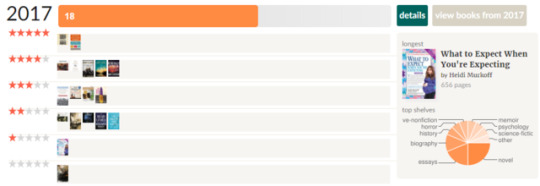

I read 18 books in 2017. These were my favorite 10.

1. True Grit by Charles Portis (1968)

Portis captures something intangible about Mattie Ross that neither movie seems to be able to, or maybe they don’t even try. The movies place the bulk of the weight of the title on Rooster Cogburn’s character, the book places an equal amount of “true grit” within Mattie. She plays a supporting role in the movies, but she stars in the book. The story is efficiently told with impeccable dialogue and it maintains a perfect balance between suspense and action.

2. The Infinite by Nicholas Mainieri (2016)

Teenage love often runs the risk of melodrama, but The Infinite places the love between Luz and Jonah into a perspective that extends far beyond the scope of its teenage characters. Mainieri juxtaposes the authentic beauty of a post-Katrina New Orleans and the complicated dynamic of different populations within the city with a vast and dusty swath of Mexico ruled by drug lords—each a landscape of self-destruction that yearns for forgiveness and hope.

Like most teenagers, Luz and Jonah are eager to come to terms with the events of their lives they had no control over while also attempting to navigate the dodgy waters of young adulthood. The Infinite captures that time for its characters in a way that is somehow both believable and astounding in its suspense, but above all, in a way that is sincere.

3. How to Be Alone: Essays by Jonathan Franzen (2002)

These essays are undoubtedly dated, but they're also surprisingly still relevant. The collection is a sort of homage to literature in the face of new technology, and there will always be new technology.

4. What the Dog Saw and Other Adventures by Malcolm Gladwell (2009)

This collection was my introduction to Gladwell, though I’ve known for a while I would appreciate his work simply because of the caliber of my friends who reference him on a regular basis. In these essays he writes with a psychological depth that goes well beyond what would ordinarily be expected from a writer, and to me, that is the payoff. Some of the essays didn’t necessarily leave me feeling as if I had an exhaustive understanding of the topic so much as they left me feeling like I was not alone in feeling inadequately equipped to understand what might never be understood. And that’s at once terrifying, and reassuring.

5. In the Valley of the Sun by Andy Davidson (2017)

The horror genre is something I generally steer clear of, but left to my own interpretation, I don’t think my instinct would’ve placed Andy Davidson’s writing in the genre to begin with. To me, it belongs right next to Cormac McCarthy’s work in the Southern Gothic category.

In the Valley’s conclusion feels like horror, but the book’s plotline was never the driving force of enjoyment for me. Rather, I found the payoff to be in the characters and the landscape, both of which revealed just enough about themselves to maintain constant intrigue. I’m eagerly looking forward to Davidson’s next book.

6. Carry the Rock: Race, Football, and the Soul of an American City by Jay Jennings (2010)

This book is a reminder that we are not far removed from the 1957 Central High Crisis, and that we are still grappling with factors that contributed to that event. And also that that recognizable and celebrated occasion is just one event in a spectrum that forces our society to look into the mirror at who we actually are. It parallels well with Coach Bernie Cox, who forces his 2007 football team to take a look at themselves and see how lacking teamwork will inevitably lead to a loss—in football, and in a segregated society.

7. Shakespeare: The World as Stage by Bill Bryson (2008)

I appreciate Bryson's ability to keep things in perspective. Most biographies tend to present opinions as fact, while Bryson is more likely to say "Here's what scholars think and the reason they think it." The problem with that brand of presentation is that you sacrifice a continuous narrative in lieu of one that starts and stops, rewinds, then starts again. Good for scholarship, but not as entertaining from a storytelling perspective.

8. War Porn by Roy Scranton (2016)

If nothing else, this book lives up to its title. It gives a glimpse into the strange and terrible and pornographic effects of war on the people who voluntarily and involuntarily participate in it. The American soldiers in the book are vile when described both in country and while stateside. While I understand those soldiers exist, as an Army veteran, I have a hard time accepting that generalized portrayal. Crude and disrespectful, yes, but not vile. I wanted a character I could relate to and the closest thing this book gave me was the Iraqi mathematician. That part of the novel I found to be the most impressive. My least favorite sections were the ones intentionally made up of clipped scenes and nonsense, which had no payoff for me.

9. Dead Lands by Benjamin Percy (2015)

Intriguing story, but I think the overt acknowledgment of Lewis & Clark kept jeopardizing my suspension of disbelief. It was a constant reminder that this was something a writer thought up. However, I did enjoy the mystery of the world, and Percy’s ability to craft powerful sentences. I look forward to picking up another of his books.

10. All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque (1929)

I appreciated how much ground--time, geography, philosophy of war/conflict, camaraderie, history--this novel covers, but the cost of that seems to be a lack of character development.

Biggest Disappointment: 15. Thunderstruck by Erik Larson (2006)

I had a hard time getting into either of the two stories here. I kept waiting for the characters involved in the murder to get interesting, but it never happened, so I kept thinking we would get some gruesome details when we got to the actual murder, but that didn’t happen either. The advancement of technology is interesting in theory, but when all the details were laid out, it was simply a parade of egos. I think I would’ve rather read this as a 5,000-word short story.

Previous Book Lists: 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A unique, fashionable, lined notebook with modern and amazing Paulette Goddard cover. It's your notebook and you can write here your goals, tasks and big ideas. On the special first white page is information - This notebook belongs to: (and a little motivation and inspiration about you! :) ).This great quality product make amazing gift perfect for any special occasion or for a bit of luxury for everyday use. Blank Notebooks Are Perfect for every occasion: Stocking Stuffers & Gift Baskets Graduation & End of School Year Gifts Teacher Gifts Art Classes School Projects Diaries Gifts For Writers Summer Travel & much much more… (proud, focus, fun, achievement, trust, pleasure, investments, profit, money) ✳️✴️✳️✴️✳️✴️✳️✴️✳️ Paulette Goddard (born Marion Levy; June 3, 1910 – April 23, 1990) was an American actress, a child fashion model and a performer in several Broadway productions as a Ziegfeld Girl; she became a major star of Paramount Pictures in the 1940s. Her most notable films were her first major role, as Charlie Chaplin's leading lady in Modern Times, and Chaplin's subsequent film The Great Dictator. She was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for her performance in So Proudly We Hail! (1943).Her husbands included Chaplin, Burgess Meredith, and Erich Maria Remarque. See the other products in this exciting series and discover hidden talents within yourself now! ⬇️⚜️⬇️⚜️⬇️⚜️⬇️⚜️⬇️ https://www.amazon.com/Paulette-Goddard-notebook-achieve-Notebooks/dp/1703716612/ref=mp_s_a_1_1?keywords=lucanus+goddard&qid=1575440505&sr=8-1 ⬆️⚜️⬆️⚜️⬆️⚜️⬆️⚜️⬆️ #paulettegoddard #goddard #lucanus #notebook #independent #publisher #kdp #amazon #kindledirectpublishing #book #note #journal #inspiration #writing #gift #giftideas #amazing #biography #quotes #motivationalquotes #famous #people #business #entrepreneurship #entrepreneur #marketing #motivation https://www.instagram.com/p/B5o-5fgAVsB/?igshid=13tebwm9x7iw4

#paulettegoddard#goddard#lucanus#notebook#independent#publisher#kdp#amazon#kindledirectpublishing#book#note#journal#inspiration#writing#gift#giftideas#amazing#biography#quotes#motivationalquotes#famous#people#business#entrepreneurship#entrepreneur#marketing#motivation

0 notes