#between these two you can also see the dichotomy of my sketching styles

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

more sketches from the character lineup in progress. validated by the fact that this is the first completed sketch I've done of Oscar (left) in literal years and it was surprisingly easy. my boy ily. oh also karyn is here for comparison

#kat speaks#from the writer's den#my art#between these two you can also see the dichotomy of my sketching styles#Oscar : fuck posing we ball#Karyn : girl help your proportions are stressing me out#you can tell that Karyn's was the first I did also from how messy it is jjjdjdkd#as I do increasing numbers of sketches in a short period my ability to do actually good first passes increases#resetting every time I go more than two days without#side note but I LOVE drawing Oscar's hair :3c his was inspired by one of my friends in high school who was Greek#he had these really tight dirty blonde curls and my brain went ''aight those are the exact curls Oscar has now''#albeit a different color. Oscar's hair is a reddish brown color#triste is the only one allowed to be blonde and even then his barely looks it anymore#void talks

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

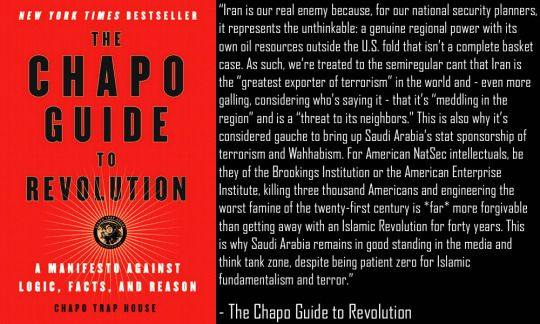

Editor's note: while I've certainly been away from Can't You Read for quite a while, anyone who follows my work at ninaillingworth.com or my Patreon blog already knows that I've been writing (and podcasting) again. You can check out some of my latest essays here, here and here; to listen to the podcast I co-host with Nick Galea (No Fugazi) just click here.

Today however I'm back on my bookworm bullsh*t with another curiously dated review of left wing literature from my extensive library of pinko pontification. In today's review, we're going to be taking a look at “The Chapo Guide to Revolution: a Manifesto Against Logic, Facts and Reason” written by five members of the popular left wing podcast “Chapo Trap House” - specifically, Felix Beiderman, Matt Christman, Brendan James, Will Menaker and Virgil Texas.

Baby Steps up the Ramparts

It is I will theorize, utterly impossible to write a review about the Chapo Trap House book without engaging in the extremely online, three-sided culture war that has sprung up around both “the Chapos” themselves and the enormously popular podcast they host. In light of the fact that seemingly everyone on the internet who detests the show regard the Chapos as slovenly crackpot losers born on third base and podcasting from mom's basement, it really is alarming how much digital ink has been spilled about the various types of “threat” to all that is good and holy this simple irony-infused podcast supposedly represents. While I intend to largely sidestep that discussion by focusing entirely on the book and not the podcast (which I don't listen to regularly, to be honest with you), I accept that virtually nobody reading this is going to be happy unless I do something to address the elephant in the room, so here goes:

Neera Tanden and her winged neoliberal monkeys can eat sh*t, but extremely online leftists have a point that the Chapos themselves occasionally skirt the line between mockingly ironic reactionary thought and just plain old reactionary thought; although this is not particularly alarming to me because they're Americans and America itself is a breeding ground for reactionary ideas – decolonizing your mind is a process and I'm pretty sure it's one I myself am also engaging in still every single day of my life at this point. Importantly, in my opinion this failing does not make them cryptofascists so much as the product of American affluence; I'm having a hard time understanding how teaching Marx and Zinn to Twitter reply guys serves the fascist agenda in any meaningful way. While I obviously can't pretend to know another person's heart, in my opinion the Chapo boys are definitely leftists but they're obviously not labor class and yes it's a little hard to explain away the group's loose affiliation with the (objectively strasserist) Red Scare podcast through co-host Amber A'Lee Frost - but I'm not going to waste a couple thousand words trying to untangle Brooklyn independent media drama from half a country away and besides, Amber didn’t write this book. Despite these critiques however, I think it's important to note that under no circumstances am I prepared to accept the argument that with fascists to the right of me, and lanyards, um also to the right, the real problem here is... Chapo Trap House.

Ok, with that out of the way let's dive right in and talk about the question I think most folks who've written about The Chapo Guide to Revolution have largely failed to grasp – namely, what kind of book is it precisely? Combining elements of comedy, playful online trolling, historical analysis, political theory and good old-fashioned cross platform promotional marketing, the book has often lead critics to compare it to catch-all comedic efforts like Joe Stewart's “America” or even humorous men’s lifestyle advice texts like “Max Headroom's Guide to Life.” This is I think an essential misreading of the fundamentally earnest and direct tone the book actually takes in its efforts to reach a fledgling audience growing more receptive to left wing ideas. The Chapo Guide to Revolution is, as the cover says, a manifesto; but rather than serving as the mission statement for a particular formed political ideology, the Chapos have written an extremely effective, entry-level argument for why labor-class millennials should be leftists – and, of course, why they should listen to Chapo Trap House; this is still a cross-promotional work after all.

Naturally as befits a book about a comedy podcast, albeit a very political one, the Chapo Guide to Revolution is an extremely funny book that does a remarkable job translating the type of caustic online humor previously only found in left wing Twitter circles, onto the written page. While its certainly true that this quirky style of comedy can be a little difficult to grasp for the uninitiated, and typically a cross-promotional work of this type will get bogged down in self-referential humor and inside jokes, the book mostly avoids this trap by sticking with the basics and assuming that the reader has literally never heard an episode of Chapo Trap House, which in turn makes the humor fairly universal and extremely accessible – at least for anyone under the age of fifty. This endeavor is greatly aided by the dark and dystopian, yet hilariously eviscerating art of Eli Valley; a man who himself has since become one of the leading left wing critics of establishment power online through his extremely provocative sketches and ink work.

The truth however is that if the Chapo Guide to Revolution was merely just a funny book, I wouldn't be reviewing it here today. No, the reason this book is worth writing about at all lies in the fact that underneath all the jokes, taunts and “half-baked Marxism” lies an objectively brilliant work of historical analysis, cultural critique and left wing political theory – albeit an unfocused theory that borrows heavily from half a dozen functionally incompatible left wing thinkers and literary giants, but a fundamentally serious work of political philosophy nonetheless.

Yes, that's correct; I said brilliant. Where think-tank minions and neoliberal swine in the corporate media see a petulant pinko tantrum, and online leftist academics see privileged dudebros appropriating Marx (poorly), I see a brilliant and yet stealthy synthesis of political theories, historical analysis and organizational ideas originally presented by writers like Howard Zinn, Noam Chomsky and Thomas Frank. Drawing on historical theories from Marx, Gramsci and Rocker, the Chapos have cobbled together a rudimentary political philosophy that represents a crude and yet promising welding of anarchist concepts about labor, Marxist concepts about economics and democratic socialist concepts about politics, collected together under the generic banner of “socialism.”

At this point some of you are undoubtedly snickering, but please bear with me for a moment here because what the Chapos (or their ghostwriter) have done in this book is truly a marvelous thing to behold precisely because you can't see it unless you're paying close attention. By positioning The Chapo Guide to Revolution as both a comedic work and an introductory level text, the authors have created a sort of unique crash course in left wing history, geopolitics, philosophy and political theory for a newly awakened generation of Americans who find themselves increasingly politicized whether they like it or not.

Underneath the acerbic millennial humor, “extremely online” diction and unrelenting waves of sarcasm, The Chapo Guide to Revolution is also a surprisingly accurate “CliffsNotes” style textbook presentation of multiple broad-based social science subjects – here are just a few examples:

In “Chapter One: World” the book presents a rudimentary and yet deliciously insightful history of post-World War II American empire that draws on authors like Howard Zinn and Noam Chomsky, with a touch of contemporary writers like Greg Grandin and Naomi Klein. In particular the attention devoted to condensing the target audience's formative experiences with empire like the War on Terror, the invasion of Iraq and the war in Afghanistan, into a short and coherent narrative that can be easily shared with other novice political observers makes this book an invaluable resource for budding millennial leftists Additionally, while it certainly might have been an accident, the Chapos' choice to wrap this “Pig Empire geopolitics for newbs” lesson in a protracted joke about America as an extremely ruthless corporate startup at least touches on ideas presented by writers like Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, Sheldon Wollin (or Chris Hedges repeating Sheldon Wolin), Joel Bakan, Rosa Luxemburg and others.

In Chapters Two and Three, entitled “Libs” and “Cons” respectively, the authors conduct a remarkably thorough political science lesson on the two major mainstream political “ideologies” in American culture, including both a rough outline of their history and their modern calcification inside the Democratic and Republican parties. Of course both of these sections rely heavily on the personal experiences of the authors growing up in a politicized America, but these discussions also dip into the works of Thomas Frank and Cory Robin to explore and critique the liberal and conservative political mindset respectively; in particular the Chapos summary of Robin's work on the conservative worship of hierarchies is an inspired distillation. More importantly however, the Chapos also expose the way in which these two ideologies represent a false dichotomy within the greater confines of a larger capitalist socioeconomic order; which is of course a (still absolutely correct) idea straight out of the works of Karl Marx.

In Chapter Six, appropriately entitled “work” the authors engaged in a disarmingly earnest discussion about wage slavery, the false promises of the protestant work ethic and the history of terrible jobs available to the labor class under various iterations of the capitalist project. This is followed by a humorous, but dystopian review of what future jobs might look like if the neoliberal socioeconomic order continues on as it has so far, and an extremely brief but sincerely argued pitch for completely transforming the role of work in society through some from of technologically assisted anarcho-communism. This last idea is admittedly a little half-baked but you have to admire their balls when the Chapo boys flatly call for a three hour workday; a position that will undoubtedly be popular with the labor class who're currently engaged in all those sh*tty jobs the book describes earlier in the chapter. Once again this synthesis of left wing ideas about work does represent a new and unique formulation, but despite the humorous and original content you can also clearly see the influence of anarchist writers like Kropotkin, Rocker and Goldman in this chapter, as well as contemporary authors like David Graeber and Mark Blyth.

Unfortunately, if there is a downside to writing a brilliantly subversive comedy book that functions as a “my little lefty politics primer” for politically awakening millennials, it's that you simply don't have the space for an intellectually rigorous examination of all the ideas you're sharing – there is after all a big difference between reading the Cliff Notes version of Zinn, Chomsky or Marx, and reading the original theories in their full form. Furthermore, the individual life experiences, idiosyncrasies and humor styles of the authors do at times bleed into the text in a way that I personally suspect was detrimental to the overall analysis. Here's a short list of “sour notes” I found in this otherwise remarkable book:

From what I have listened to of the Chapo Trap House podcast, it has always been my impression that the Chapos were particularly effective critics of American corporate media, so I was a little disappointed that the chapter on media in The Chapo Guide to Revolution was a fairly tepid and narrow discussion about (admittedly vapid) bloggers turned celebrated pundits. Don't get me wrong, I'm sure power dunking on the likes of Matty Yglesias, Meagan McArdell and Andrew Sullivan was viscerally satisfying for the book's target audience, but there's really not much of a broader critique of the media's ideological role in American capitalism and culture here like one would find in Herman & Chomsky's “Manufacturing Consent”, Matt Taibbi's “Hate Inc” or Michael Parenti's “Inventing Reality.” This absence I fear has the tragic side effect of reinforcing the idea the American corporate media sucks because egg-shaped moron bougie pundits are bad at their job and not because of the inherent failings of the for-profit media model and the institution's true role as an ideological shepherd keeping the masses aligned with the goals of elite capital and the ruling classes – almost exclusively against the bests interests of the labor class.

The introduction is written in what I can only assume is a sarcastic imitation of right-leaning self improvement books with a touch of Tyler Durden's Fight Club ethos thrown in; this might have been a better choice in a completely different book but it's largely out of place with the rest of this book. At this point I should also say that the best part about the Kidzone intermission is that it was only two pages long. Needless to say, neither one of these sections did anything for me whatsoever.

While it's entirely possible that at forty-three years of age, I'm simply too old to really get the “millenialness” of the chapter on Culture, the simple truth is that I found most of it to be a fairly useless examination of pop culture influences the Chapos hold in reasonably high esteem. As someone who isn't particularly engaged in watching lengthy television series or regularly playing video games, I really couldn't dig into most of the material presented and the less said about the art jokes and the bizarre absurdist discussion of elevator brands, the better. There is however one rather notable exception here in the brief essay on The Sorkin Mindset, which is an objectively brilliant evisceration of the liberal obsession with the West Wing and the tragic effect that obsession has had on Democratic Party politics – this really could have gone in the chapter on “Libs” because it's that valuable of a tool for understanding and critiquing the modern liberal lanyard worldview. Finally I guess I should note that while the Chapo boys' insightful critique of the vapid “prestige TV” phenomenon is both interesting and correct, it really only “matters” if you're a consumer of these types of series – and I'm not.

While I certainly understand the authors' decision to use their notes section to preemptively debunk bullsh*t complaints about the more outrageous accusations they level against the American establishment, I would have liked to see a “recommended reading” section. It is very clear that the Chapos have a reasonably strong background in imperial history, political science and labor theory and I feel like pointing readers towards writers who expand on the theories they summarize in The Chapo Guide to Revolution might have been a better use of space than printing links to old internet articles bad faith actors will never type into a search engine anyway.

Although it might seem like there was more about the book I didn't like, than I did, this is a little misleading – the first three chapters of The Chapo Guide to Revolution are pure fire and comprise over half of the volume. If you throw in the brilliant chapter about work and labor theory, the overall package is far more substance than style, despite the fact that it remains humorous and a little bit edgy throughout the book. While it's certainly fair to say that an introductory primer on why you should be a leftist for newly-politicized millennials isn't a must-read for everyone, the simple truth is that the vast majority of online leftists I know could learn a thing or two from this rudimentary synthesis of various left wing ideas into the seeds of a working, modern political ideology compatible with a uniquely Americanized, millennial left.

While no three hundred page comedy book written by five podcasters from Brooklyn is going to teach you everything there is to know about socialism and left wing ideology, there's something to be said for offering an accessible, entry-level alternative tailor-made for a target demographic already being heavily recruited by the fascists. As a starting point for exploring left wing political thought, you could do a lot worse than The Chapo Guide to Revolution and for a generation of kids who've mostly been encouraged to be passive accomplices to their own subjugation while blaming their misery on anyone even more powerless than they are, there is perhaps nothing more valuable than a condensed narrative that explores how to even think about another way to live.

Remarkably, this book finds a way to deliver on that monumental task while simultaneously failing to grasp one single relevant thing about the cherished American novel Moby Dick. Despite this infuriating literary myopia and insolence, this still might literally be the best book ever written for young American leftists who simply aren't going to spend ten years reading academic literature written by dead white guys from Germany and Russia. - nina illingworth Independent writer, critic and analyst with a left focus. Please help me fight corporate censorship by sharing my articles with your friends online! You can find my work at ninaillingworth.com, Can’t You Read, Media Madness and my Patreon Blog Updates available on Twitter, Mastodon and Facebook. Podcast at “No Fugazi” on Soundcloud. Chat with fellow readers online at Anarcho Nina Writes on Discord!

#chapo trap house#book review#The Chapo Guide to Revolution#left wing politics#geopolitics#humor#leftism#introduction to leftism#Noam Chomsky#Howard Zinn#Thomas Frank#Cory Robin#culture war#politics#news#media#bloggers#savage burns

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arthur & The Myth of Sisyphus

(Arthur/staircase juxtaposed to Sisyphus/rock)

As disclaimer, this may be a generalised statement/inductive analysis, not unique to his diegesis. Will probably be too verbose for some to read, but writing is organic as breathing for me and if I don’t discuss my beautiful clown husband at length, I might very well be caught with a bruised and desiccated lung lol (as you can probably tell, academia is hæmorrhaging into my casual diction)

I’m typing this, more or less, to illustrate my (possibly exhausted) perspective on how significant the staircase is to Arthur’s narrative. Specifically focusing on how it relates to Sisyphus and his eternal struggle to push a cumbersome stone uphill. (Says this all the while knowing I’ll lose said focus by the end of this, oops) That being said, this also just might be some cathartic release in the form of diluted research.

All things considered, with an economy that appears to teeter just so on the verge of instability, most, if not all, may resonate with the impending sense of futility that accompanies society’s defective concept and subsequent flawed execution of ‘adulthood’, including, but not limited to: excessive demands imposed by draconian academia, 9-5 corporate mandates exercised to excess; in addition to parenthood (if applicable). All for the sake of feeding continued survival in a universe where life is erroneously scrutinised under myopic scope of legality. Summarily, we can all embrace solidarity in our respective sharing of adversity, attended by a seemingly endless, merciless journey towards acceptance.

Arthur is my most current muse within the fictional realm (irreplaceable, to boot) so this character study might be more gratuitous than enlightening, but, in essence, I often like to conceive him as a resounding echo that’s effectively sound in giving voice to the voiceless; whispered and indistinct though it may be. However, it could be said that the power of his presence resides, not in the delicate, understated nuance of his vocal tone, but rather the elegant and passionate language of dance pronounced by his feet. Namely, the Sisyphean task of climbing that emblematic staircase.

Whether suffering a daily, if not arduous, ascent one derelict step at a time, or dancing a rhythmic descent to liberation, Arthur’s soles bespeak of a soul that’s been tormented relentlessly throughout the near 40 year span of his existence. Heels throbbing with Weltschmerz, the resulting ache of his travails would often appear as little more than a numbing nuisance to be rubbed away upon a less whimsical return as the prodigal son. In this way, the audience might compare Penny’s impact in Arthur’s life to that of the onerous stone that plagues Sisyphus. Despite being an absent force to her son’s oppressive intimacy with these formidable steps, there is something to be said for the manner in which concern is essentially a wisp in the void when her child’s health utters a silent plea, a murmured urgency, for attention.

Perhaps, we could all agree that a fraction of Artie’s extroverted anger towards Thomas was only partially misdirected. As a means to demonstrate the implied difficulty Arthur expresses for emotional release, especially so for repressed anger, it would have been interesting to witness a scenario in which he doesn’t heed Penny’s request whilst hiding behind a closed door. Given the egocentric brush that paints a broad stroke to her demeanour, would he be vindicated in raising his voice a few decibels ? If for no other reason than to dispel frustration by virtue of necessity. Of course, this isn’t to undermine the fact that Arthur displays potential signs of regressive behaviour (not exclusive to his circumstance but nevertheless germane). A hapless symptom of afflicted childhood incited by an inflamed basis of Nature v. Nurture.

With nearly all sense of identity drifting aimlessly as unanswered queries, there could be reason yet as to why Arthur adopts his Carnival and Joker personas. Beyond factors of aspiration and affinity alone. As someone (myself) who could be classified with mild alexithymia, all the while being fairly averse to labels, the concept of employing alter egos solely to assist in self-expression may not be uncommon, if not muted in translation. In a way that isn’t explicitly stated, we could infer that Arthur enforcing a purpose to evoke genuine smiles and laughter is a means to compensate for those of which he was deprived during his formative years. Speaking as an armchair psychologist, there could be evidenced an intimation of placebo effect for the presence of Pseudobulbar Affect. While this syndrome affects the nervous system and is hence more physiological than psychological, the nature of its infliction could be considered as a bridge between the two.

Certain conditions, of which remain unknown, from his childhood may have contributed to the development of this condition, emphasising a noted relation to thinking patterns. My theory is that any measure of neurosis is directly proportional to the degree of physical complications that may manifest. Arthur is a fairly sensitive man. A rough sketch of this attribute can be observed even whilst Arthur is gallivanting as Joker. In fact, one could even venture to say that his identity is actualised in this form. Cliché ? Yes. But, no less pertinent. Furthermore, a deduction might be made in which Carnival alludes to being a medium that balances the dichotomy between Arthur/Joker.

Yes, these may be points that have been proposed ad nauseam 😶 You also may be wondering: Exactly what role does Sisyphus play in this ?

Ultimately, I’ve come to the conclusion (hagiography) that Arthur, while emotionally sensitive, hardly translates that sensitivity to his visceral being. Revisiting the first bathroom scene, maybe one could see the gloomy reflections of Atlas and Sisyphus reflected in one burdened man, lost in soulful dance. Summarily, he could never strike me as one to admit defeat. To succumb to the siren’s lure of quietus. As illustrated by every Joker rendition before him, Arthur Fleck is no different in how his philosophy materialises. Blending the colours of absurdism and nihilism. While the assertion seems contradictory, considering Arthur’s initial intent to commit suicide on live television, I do believe his animus was strictly encouraged by his comedic inspiration, opposed to an active desire.

Fundamentally, this leads me to my final point (although, admittedly, this isn’t the end, I could literally talk to death about this man, and I will). The contrast of comic styles between Arthur and Murray. This might be the understated controversy of discourse, and my perspective on the matter may be unpopular, if even acknowledged, but just to clear the air, the following assumption isn’t meant to excuse him or his actions. Rather, to offer perspective. If you observe carefully, you might notice that there’s no distinct disparity between Murray and Arthur’s sense of humour. Given the era and its dogged appeals to censorship, Murray’s delivery could be regarded as nothing short of condensed and disguised. As our dear Artie reiterates, comedy is indeed subjective, but, as a matter of course, the brand that either presents isn’t particularly risible given context.

As an audience, we only know Murray on a superficial level. We know he’s a comedian. By the end of the film’s duration, we might have dismissed him as the stock bully. His humour was cruel, callow and sadistic when dispensed towards a man who deemed him a pillar of admiration. However, similar could be said for Arthur’s execution. Consistently morbid and sardonic, these elements of comedy that provoke laughter for Arthur comprise a vague semblance to Murray’s comedic anatomy, despite how patently trite and puerile the latter’s jesting was, when delivered to our undeserving victim.

Arthur was thoroughly justified in his feelings of despondency and disenchantment. Yet, objectively speaking, depending on either side of contention, one’s perception may be determined by whether or not his sensitivity was merely exaggerated when juxtaposed to a comedian who was, more or less, just doing his job; albeit questionably. Unprofessionally. We couldn’t know exactly what Murray was thinking or precisely why he invited Arthur on his show. Surely, public humiliation wasn’t his prime agenda. Curiously enough, I seemed to detect an air of indifference expressed by him when Arthur confessed (*insert delusional gif*). As if it was to be expected.

Ipso facto, with how the sequence pans out, there may have been the possibility of Murray personally investigating the subway murders and considering Arthur a suspect, consequently aiming to extract his confession (a reach, I know ! ) but, maybe not...

Not when the theory of Arthur contriving delusions, having been situated in Arkham the entire time, chimes as possible reasoning.

That, in itself, is a paradox...

...Will we ever ?

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alice Mere · Costumier, The Australian Ballet

Alice Mere · Costumier, The Australian Ballet

Dream Job

by Elle Murrell

Things I learned going BTS at The Australian Ballet: #1: Tutu’s are stored upside down. #2 they’re surprisingly weighty. Photo – Caitlin Mills for The Design Files.

Alice Mere (right) works her dream job as Costumier at The Australian Ballet. She’s pictured here with her colleagues Cutters Ruth (left) working on a tutu for the forthcoming The Sleeping Beauty, and Etai (centre) crafting belts for Spartacus. Photo – Caitlin Mills for The Design Files.

The 32-year-old studied an Advanced Diploma of Fashion Design and Technology at TAFE in Adelaide before graduating from Fine Arts -Production (Design Realisation) from Victorian College of the Arts in 2016. Photo – Caitlin Mills for The Design Files.

Since she was a young girl, Alice has loved to make costumes, in particular, period and historical designs. Photo – Caitlin Mills for The Design Files.

The Australian Ballet Production Department’s fabric dyeing supplies, with testing ballet slippers alongside a headpiece from a past performance. Photo – Caitlin Mills for The Design Files.

History-buff Alice also did ballet when she was a young, but gave it up just before graduating to her pointe shoes! Photo – Caitlin Mills for The Design Files.

Alice and her colleagues have just started on costumes for Spartacus, which is a new show opening in September. Photo – Caitlin Mills for The Design Files.

Around half of Alice’s making is done by hand, the rest by sewing machine. Photo – Caitlin Mills for The Design Files.

Racks of tutus. ‘I’ve worked on them but I haven’t made one from scratch yet… it is something I definitely want to learn how to do because it is ‘the ultimate costume’ – very special, not something you wear anywhere else,’ tells Alice. Photo – Caitlin Mills for The Design Files.

Working on part of a leotard for Spartacus. Photo – Caitlin Mills for The Design Files.

When you walk into the Production Department of The Australian Ballet on Melbourne’s Southbank, clouds of upturned tutus and bejewelled bodices grab your attention. But then, you notice how quiet it is. Every wall of the open-plan floor is lined with racks of ornate costumes or rolls of materials, and these encircle row upon row of cutting and sewing tables. Yet, within this brightly lit, bustling workplace, there is a pervading sense of calm productivity.

This dichotomy begins to make sense when I meet softly-spoken ‘Costumier’ Alice Mere, and a number of the ‘Cutter’ colleagues with whom she works closely. Sewing awe-inspiring garments for our national ballet, they all verify, is one of the most pleasant and rewarding ways to spend your day.

The 32-year-old has been doing this for the past eight months. Twenty-seven years prior, you would have found her making tutus for her teddy bears, period costumes for Barbie dolls, or fashioning a particularly memorable mermaid’s tail from a pair of old leggings!

In-between all of that, Alice completed an Advanced Diploma Fashion Design and Technology, took time out to explore the world (including a two-year stint living in London), graduated from VCA with a degree in Fine Arts – Production, and even ran away with Circus Oz (…well, kinda).

The dedicated costumier interrupted some Spartacus leotard sewing to chart the inspiring pathway that’s lead her to The Ballet.

The most important verb in the get-your-dream-job lexicon is…

You have to work hard. You also need to have enthusiasm and just put yourself out there and see what happens.

I landed this job by…

I lived in a small South Australian town called Port Lincoln until I was 14 and then we moved to Adelaide. My mum was very crafty – she sewed our clothes, knitted, and all of those kinds of things. So, from as early as I can remember, I was always sewing scraps of her offcuts together.

In my early 20s, I studied Fashion Design and Technology at TAFE in Adelaide (2005-2008), which was a practical, three-year-long Advanced Diploma. In our final year, I took work experience at the State Theatre Company, and for the first time, I realised I wanted to work with costumes rather than in fashion. In my fashion-focused course, we started with the price-point and worked backward, often using the same patterns and tweaking them. Costume-making felt more creative to me, and you would never know what you were going to get to do next.

After TAFE, I just wasn’t sure how to get into it costume design, so I kind of forgot about it for a while. I have a seven-year-gap between my studies, where I travelled and supported myself with different hospitality jobs.

When I came back and moved to Melbourne a friend recommended that I look at courses at the Victorian College of the Arts and, AMAZINGLY, I got in! For Fine Arts -Production (Design Realisation) the application was a folio application, two interviews and a group interview, so that was full on! For the folio, you could choose between three plays and then you had to design costumes or set or props and do a presentation. I chose Cloud 9, and I designed all of the costumes for the entire play. Afterward, I realised that they only really expected you to do one!

The course was, again, mostly practical, and we learned how to design and make costume/sets/props, predominantly for theatre and dance. I did an internship with Circus Oz, almost full-time for five weeks. It was really interesting and the functionality was very different to what I had done before. For example, the trapeze had to have part of the neck covered, other costumes needed a little pocket with some protective foam over the spine, and you couldn’t have anything that may catch with a lot of people twisting around one another!

After graduating from the VCA in 2016, I was freelancing as a Costume Maker for about six months, taking work with the Melbourne Theatre Company, Circus Oz, and a few days at the Victorian Opera – mostly gained through word-of-mouth recommendations. I sort of assumed I’d be freelance for a long time, as there aren’t that many full-time jobs around for makers. But I sent out my CV to the companies I really wanted to work for on a permanent basis –The Australian Ballet, The Melbourne Theatre Company, and ABC – anyway. I tried not think about doing this too much; my email wasn’t very formal or long-winded, more like: “This is my CV. If you need a hand please give me a call.”. I just got it out there.

Months went by and then out of the blue I got an email asking if I was available to work on The Australian Ballet’s Alice in Wonderland for a few months. I was surprised and so excited. It was pretty hectic. There was quite a bit of overtime and I just tried to work hard and be as efficient as possible. At the end of that job, it just so happened that one of The Ballet’s full-time staff was leaving and I was offered a longer contract. I’ve been here ever since!

A typical day for me involves…

I’m definitely more of a morning person, so I like to get up early and (most of the time) ride my bike to work from my home in Brunswick, so I’m really awake and can start by around 7:30 or 8am. It’s really amazing that we have this flexibility to start when we want to (within reason) and it means I can get home early, walk my greyhound Louie, and have those extra hours to potter around, run errands, cook a nice dinner etc. I always try to meditate in the evening as well. It just helps me to relax, stress less in general, and is a really nice way to just reset at the end of the day.

Work each day is really varied, and it depends what show we’re working on. As a Costumier, I work under the Cutters. They interpret the Designer’s sketches and do all the patternmaking and cut the fabric, then delegate the construction of the garments to the Costumiers. So I spend a typical workday sewing, either on a machine or by hand; it depends on what needs doing.

For example, we just finished working on Merry Widow (see costumes in the film below), which has pre-existing costumes that need to be fitted and altered to new dancers, as well as lots of repairs. There are lots of big ball gowns, and feathers in the hair, fans and gloves… it’s very decadent! Now we’ve started on Spartacus, which is a new show opening in September. For this show, all the costumes have to be made from scratch. There is a lot of Grecian style draping, flowing fabrics; it’s going to look beautiful!

The most rewarding part of my job is…

This might sound too obvious, but after working on a show for weeks or even months, when you finally see all that hard work up on stage in a performance it’s so rewarding.

I always take a different friend with me each time and point out the little bits I contributed to. It makes you so proud to have been a part of the spectacle.

On the other hand, the most challenging aspect is…

There are constant challenges, but that’s not a bad thing at all. There are so many different ways of doing things, and so many techniques and processes to learn; I don’t think you could ever know everything, which is really lovely and humbling.

The culture of my workplace is…

… supportive, friendly and easy-going. Everyone seems happy to be there and just gets on with their work. Usually, everyone is working on something different, and we all sit at our machines and listen to podcasts throughout the day (I like My Favourite Murder, The Dollop, a lot of audiobooks and lecture series… anything historical I find fascinating).

It feels pretty relaxed most of the time, but when we’re getting closer to a show opening, everyone pulls together and works hard to get everything done.

On Job Day at school, I dressed up as…

I’m not sure we had one, but I was always playing dress-ups or making costumes for my toys. So, I should have figured out that being a Costume Maker was an actual job way earlier than I did!

The best piece of advice I’ve received is…

… ask questions, lots of them! Never be afraid to ask because you feel that you should already know how to do something. There are so many ways to do things and you’re never too old or experienced to learn a new skill.

In the next five years, I’d like to…

… keep working as a Costumier, gaining skills and experience, and eventually, I’d like to try working as a Cutter. I love pattern-making, I find it oddly soothing – there is definitely a satisfaction when you have something flat as paper and then you turn it into 3D. I’ve got much more to learn before then!

The Australian Ballet’s ‘The Merry Widow‘ is currently showing in Sydney until May 19th, followed by Canberra from May 25th to 30th, and Melbourne from June 7th to 16th. Visit Australianballet.com.au for more information on upcoming performances.

0 notes

Text

“Fashion Police”

Concept Statement:

The creative limitations placed on any creative practitioner has been more skewed especially during the heightened, socially-aware era of the 2010s – especially since social media and the internet has become a place where people can criticise more freely about the damaging effects of any creative endeavour. In saying this, the effect of the freedom to criticise is more abundant in the fashion industry – an industry that has been sustainable for decades, however facing a lot of heat in its direction on its designs – specifically designs orientating on ethnic cultural pieces. Due to this, a lot of people have unofficially become ‘fashion polices’, criticising and discussing the difference between cultural appropriation and appreciation.

While there is a fine line between cultural appropriation and cultural appreciation, the dangerous ramifications ultimately led to a decrease of value in the culture. It also doesn’t help as famous artworks – an example being ‘The Great Wave of Kanagawa’, has become strongly associated with fast fashion imagery and social media pop-culture, ultimately erasing the value behind a historical artwork. Furthermore, the appropriated usage of kimonos, especially since it has been defined historically that the usage was worn during special events – only the be commercialised and mass-produced in fast-fashion brands like Topshop or Cotton On really piqued my interest on the whole subject, and made me want to divulge on the aspect of value of cultural significance.

Another primary evidence that has surfaced recently that provoked me into discussing this idea is the rise in popularisation in Japanese writing on fast-fashion apparel. While it appears to have, a positive effect raising some multiculturalism and what not, the addition of any Chinese/Japanese/Korean writing adds a sort of ~unique and different~ edge to the article of clothing. This ‘edge’ is primarily focuses on the different, and while some argue that these clothing brands are being multicultural – the fact the motivation focuses on the different reaffirms the argument of how it’s just a new style of commercialised fashion to trek into – but does that make it okay?

The inspiration behind was influenced by my ethnic upbringing, and witnessing these fashion dichotomies in the media and the internet. Throughout my entire concept for my major work I divulged into these areas specifically to East-Asian traditionally clothing originating in Japan, South Korea, and China. I bridged the contrast by showing the dichotomy between fast-fashion clothing, and traditional clothing – further bridging it with clothing material/textiles generally used in these fast fashion clothing and reverse it with the usage of traditional artworks from the respective countries.

In saying so, I also bridged the similarities by drawing/re-drawing the traditional garment next to its ‘fast-fashion’ counterpart. By doing so, the comparison with the style and materials enable the audience to understand the whole idea of the value behind these traditional garments. I decided to put these drawings side by side, to also show a subtle ~who wore it better~ type of scenario, with the audience being somewhat interactive and question themselves on which one they believe is more aesthetically pleasing, and why. This is interesting because it provokes a discussion as we are seeing two of the same dresses in different periods, which enables us to talk about it. Furthermore, having a similar idea (the dresses) with its slight differences (the fabric and style) makes us see what is the ‘trend’ since most trends we are unable to recognise, considering we are living through it – so by having a benchmark, people can realise more visually about the discrepancy.

The aim of my major work hopefully brings understanding on this topic of value in ethnic-culturally pieces, and how fast-fashion industries commercialising it ultimately becomes to reason it is perceived today. The medium for my major work was decided on which was best to showcase and exemplify my argument – so in saying so, I chose to edit the following dresses with the materials to give the effect. Furthermore, displaying the major work as a poster allows the audience to immerse themselves as if they are watching a fashion pictorial. The essence of my major work is not to remove itself completely from the conditions of what designers go through i.e. spending time meticulously drawing and sketching, but rather embody it to give it a realistic touch.

Overall, my main purpose in my major work was to showcase the dichotomy between traditional and fast-fashion portrayals of ethnic-cultural pieces. I showed this through the variant use of texture, colour, and drawing a side by side profile of each clothing for people to compare the aesthetics of it. I also furthered my idea – using art you will see on fast-fashion, and actual East-Asian art to bridge this idea.

0 notes