#because I grew up next to a german river called the ELBE

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

How do you pronounce your username? For some reason, I mistakenly read 'elbdot' with the b and d reversed so it went like 'el-de-bot'.

So maybe it's 'el-be-dot' ? Or the b is almost silent so its like 'elblem-dot' but without the 'lem'? I dunno.

LMAO that seems to happen a lot :'D I've been receiving multiple messages over the years of people misreading the name "elbdot" as "eldbot" and I can see the confusion, it happens xD

If you wanna know the correct pronounciation, it's just "elb-dot"! ELB are my full inicials and dot was added for fun like if I'd shorten my last name / keep it anonymous as in "Eleanor B." <- but the dot is spelled out, you know what I mean? :D

But calling me El is just fine :D

#btw its not EL B dot#I actually for realsies have a second name starting with the letter L#So ELB really are my full inicials#which is pretty funny#because I grew up next to a german river called the ELBE#D E S T I N Y#mod#reply

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

English History (Part 8): The Anglo-Saxons

In 430, Vortigern hired Saxon mercenaries to defend England against the Picts (from Scotland) and marauding bands from Ireland. Vortigern was the leader of the confederacy of small kingdoms that England was divided into, and this was a common strategy (the Romanized English had used it at various times).

The Irish landed on the west coast of England, within easy reach of the Cotswolds. The central part of Vortigern's kingdom was situated in that region, so that may have been the reason he was the leader in this struggle. The Picts, it was reported, had landed in Norfolk. The sailors painted their ships and bodies the colour of the waves, so they couldn't be seen so easily.

According to historical legends, the Saxons arrived in three ships, each holding 100 men at most (there were probably more ships than that). The Saxon mercenaries were well-known for their ferocity and valour. They worshipped Woden (god of war) and Thor (god of thunder), practised human sacrifice, and drank from their enemies' skulls. They shaved the front of their heads, and grew their hair long in the back, so their faces would seem larger in battle. A Roman chronicler of the 400s stated, “The Saxon surpasses all other in brutality. He attacks unforeseen, and when foreseen he slips away. If he pursues, he captures; if he flees, he escapes.”

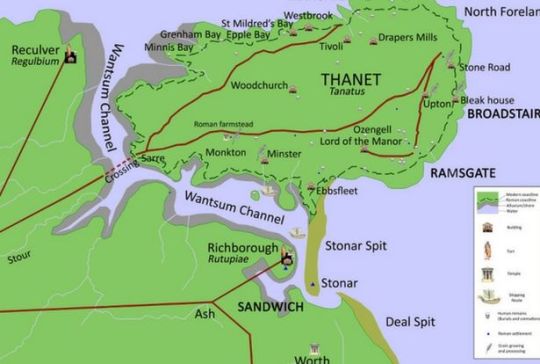

The main part of the Saxon force was stationed in Kent, and they were given the Isle of Thanet in the Thames Estuary. Other groups of soldiers were stationed in Norfolk, and on the Lincolnshire coast; they also guarded the Icknield Way. The remains of the Romanized armies (in the north) were stationed in York, which was strongly fortified.

The Wantsum Channel no longer exists, so the Isle of Thanet is now part of the mainland.

This show of strength seems to have been enough. The Picts gave up their plans for invasion. The Irish were held back by the tribal armies of the west and west midlands; the kingdom of the Cornovii (with their capital at Wroxeter) played an essential part in this.

But Vortigern's allies either would not or could not pay the Saxon mercenaries, and also refused to give them land instead of coin. According to the Kentish chronicles, the English declared that “we cannot feed you and clothe you, because your numbers have grown. Leave us. We no longer need your assistance.”

The Saxons immediately rose up, with the uprising beginning in East Anglia and spreading down to the Thames Valley. They took over many of the towns & countryside regions in which they had been stationed; they appropriated large estates and enslaved many of the native English. Then, the Saxon federates encouraged their compatriots to come and join them. The land was prosperous, and Thanet itself, as a granary, was especially prized.

Four main tribes provided most of the migrants – the Angles (Schleswig), Saxons (regions around the River Elbe), Frisians (north coast of the Netherlands) and Jutes (coast of Denmark). The river system provided already-established routes of settlement, so the settlers advanced along the Thames, Trent and Humber.

The Angles settled in east and north-east England, and by the early 500s, the people of east Yorkshire were wearing Anglian clothes. The Saxons settled in the Upper Thames valley; the Frisians were scattered over the south-east, with an important influence in London. The Jutes settled in Kent, Hampshire and the Isle of Wight (the New Forest was once Jutian land).

In some places, the Anglo-Saxons (who weren't called that yet) were welcomed; in other places they were resisted. In some places, they were accepted by the working population who had no real love for their native masters. Eventually, the Anglo-Saxons made up about 5% of the population we now call English, and it may have been about 10% in the eastern regions. However, there is no evidence for the deliberate genocide and replacement of the native population.

One of the reasons for their migration to England was that they were being pushed westwards by other tribes in the great westward migrations of that time period. Another reason was the rising sea, which was causing the northern European coastline to sink.

The Saxon revolt led to the downfall of Vortigern, who was overthrown by Ambrosius Aurelianus, another Romanized English leader. Aurelianus led a counterattack against the Saxons, and engaged in a series of battles that lasted for 10yrs. In 490, the English won a great victory at Mons Badonicus, which was probably near modern-day Bath.

The leader of the English forces for that battle is unknown. However, the name of Arthur is mentioned as dux bellorum (leader of warfare), and he is said to have taken part in 12 battles against the Saxons. He may have been a military commander with his headquarters within the hill fort of Cadbury. During his supposed lifetime, 7.2 hectares of that hill fort were enclosed.

However, as part of the spoils of war, the Saxons kept control over Norfolk, East Kent and East Sussex. There was a division in the country – Germanic tribes with their warrior leaders to the north, and small English kingdoms to the south. The division may have been marked by the construction of the Wansdyke, designed to keep the Saxons from crossing over into central southern England.

Some of the most Romanized parts of England were now controlled by “barbarians”, and so the town and villa life receded greatly. Gildas (an English chronicler of the early 500s) complained that “the cities of our contry are still not inhabited as they were; even today they are squalid deserted ruins.”

However, some of these towns and cities were still actively used as markets and places of authority. The Saxons set up their own trading area outside the walls of London (the modern-day district of Aldwych), but the old city of London was still a place of royal residences and public ceremonial activities.

In the countryside, things carried on much as usual, and there wouldn't have been any changes in agricultural practice. The Germanic settlers laid out the same field systems, and respected the old boundaries – for example, Germanic structures in Durham were set within a pattern of small fields & drystone walls from prehistoric times.

Furthermore, the Germanic settlers respected the lie of the land, and formed groups that followed the boundaries of the old tribal kingdoms. At a slightly later date, the sacred Saxon sites followed the alignment of Neolithic monuments.

For the next 2-3 generations, the English kept the Germanic settlers within their boundaries. At this time, the average life expectancy was 35 years.

But by the middle of the 500s, the Germanic peoples wanted to advance further west, to exploit the productive lands there. The main reason for this sudden expansion probably was the bubonic (and perhaps pneumonic) plague that spread from Egypt to all over the previously-Romanized world, during the 540s. The native English were struck down by it (and the Germanic peoples weren't), and the population may have dropped from 3-4 million to 1 million. There were fewer people living on the land, and fewer men to defend it. The Angles and the Saxons took advantage and moved westwards.

Ceawlin of Wessex, one of the Saxon leaders, reached as far as Cirencester, Gloucester and Bath by 577. Seven years later, his forces had penetrated the midlands, and the native kings were deposed. This was the pattern throughout England.

Pressure was growing on the Durotriges (Somerset & Dorset), and many native people left for Armorica, on the Atlantic coast of north-western France, where their leaders took control of large areas of land. They may have been welcomed there, as they may have been part of the same tribe. The region of Brittany emerged there, and the Bretons retained their old tribal allegiances, never really thinking of themselves as part of the French state. Some returned to England – the forces of William the Conqueror included a Breton contingent, and they chose to settle in south-western England.

Eventually, the native English would be mixed with the settlers, and terms like Saxon or Angle would no longer have any meaning – everyone would be English. But it was a slow process. 200yrs after the first Saxons arrived, much of western England was still under the rule of native kings. The kingdom of Elmet (now the West Riding of Yorkshire) survived until the early 600s. The “Anglo-Saxon invasion” really only came to an end in 1282 when Edward I captured Gwynedd (leader of a kingdom in north-western Wales). There were still Celtic speakers in Cornwall at the beginning of the 1500s, and the language didn't die fully until the 1700s.

#book: the history of england#history#military history#colonialism#anglo-saxon settlement of england#battle of badon#britain#anglo-saxon britain#england#wales#saxons#angles#frisians#jutes#wessex#durotriges#elmet#vortigern#ambrosius aurelianus#king arthur#ceawlin of wessex

5 notes

·

View notes