#bc in what way are we supposed to come to terms with the indian state at this point like bffr

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Wild to see the Canadian government directly blaming the Indian government for assassination of Sikh leaders on Canadian soil like woah our community has been gaslit for years for claiming that India is directly involved in destroying the lives of Sikhs abroad and finally we're being proven right

#once again.... punjab needs to be sovereign state like we live in fear there and abroad because the government actively looks to kill us#bc in what way are we supposed to come to terms with the indian state at this point like bffr#armed resistance always

1 note

·

View note

Note

hi again dia! happy first day of december ❤️💚 i wanted to ask you what, in your opinion, are the 5 most underrated dcoms? i remember you saying before that you've watched all of them so i'd love to hear your opinions 😊 - 🎅🎁🎄

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAHHHHHHHH secret santa you are so good! asking me all the best questions 💜

okay so i literally had to make a list of all the dcoms i consider underrated and then narrow down a top 5. theres lots of dcoms that i love, but that i think got the right amount of attention and care (like lemonade mouth and the teen beach movies, for example), so this list just focuses on ones that deserved more hype for their quality level.

5. The Cheetah Girls: One World (2008)

okay so even as i type this i feel like a hypocrite. i have only watched this movie one time. BUT i can acknowledge that its one of the most criminally underrated dcoms ever, tons of people didnt watch it simply because raven wasnt in it. thats why i avoided it as a child, and i didnt get around to watching it until i did my big dcom binge in 2016. and it was so good. theres a really long post floating somewhere around tumblr full of specifics on why its actually the best cheetah girls movie (my favorite is the second one purely out of nostalgia), so to paraphrase some points from that post:

its a solid example of cultural appreciation, rather than appropriation, as the girls go and learn about bollywood and indian culture together

the indian characters arent treated like props or unimportant sides, they get their own agency and storylines that are important

the songs are good!!!

basically this movie was overlooked and slept on even though in terms of role modeling and social value, and just like the first two cheetah girls movies it was important and impactful.

4. Sharpay’s Fabulous Adventure (2011)

okay so as someone whos very neutral and occasionally negative-leaning towards the hsm franchise (mostly bc its overhyped and not really representative of all dcoms), i was pleasantly surprised by sharpays fabulous adventure. this is another one that i know lots of people skipped right over and dont hold with as much esteem as the main hsm franchise, and that doesnt sit right with me.

i do not agree with the “uwu sharpay was the real victim in hsm” arguments bc in their efforts to look galaxy brained the people who say that overlook the fact that she was a rich white woman who used her power and status to exercise control over opportunities that should have been fairly and freely available for all; they were not “making a mockery of her theater” in the first movie, they were literally just kids who wanted to try out a new school activity that everyone was supposed to be allowed to participate in; and despite allegedly learning her lesson and singing we’re all in this together with everyone at the end of the first movie, she literally showed no growth in the second movie as she fostered an openly hostile environment and favored troy so heavily that it literally cost him his friends, all as part of yet another jealous plan to take things away from people who already have less than her. she was NOT the victim in the main franchise, and she did not seem to exhibit any growth or introspection either.

and that!!! is why sharpays fabulous adventure was so important. in focusing on sharpay as the main character, they finally had to make her likeable. they did this by showing actual real growth and putting her outside of her sphere of influence and control. we saw true vulnerability from her, instead of the basic ass “mean girl is sad bc shes actually just super insecure” trope (cough cough radio rebel), and this opened us up to finally learn about and care about her character. throughout the movie we see her learn, from her love interests example, how to care for others and be considerate. she faces actual adversity and works through it, asking herself what she truly wants and what shes capable of. and in the end, when she finally has her big moment, we’re happy for her bc she worked hard to get there. she becomes a star through her own merit and determination, rather than through money and connections. this movie is not perfect by any means, but it is severely underrated for the amount of substance it adds to sharpays character.

3. The Swap (2016)

okay i know im gonna get shit for this but thats why its on this list!!! just like sharpays fabulous adventure, its not perfect and definitely misses the mark sometimes, but it deserves more attention and love for all the things it did get right!

the swap follows two kids who accidentally switch bodies because of their emotional attachment to their dead/absent parents’ phones. and while i normally HATE the tv/movie trope of a dead parent being the only thing that builds quick sympathy for a young character, they definitely expanded well enough to where we could root for these kids even without the tragedy aspect. we see them go through their daily struggles and get a feel for their motivations as characters pretty well. as a body switching movie, we expect it to be all goofy and wacky and lighthearted, but it moves beyond that in unexpected ways.

the reason the swap is on this list is for its surprisingly thoughtful commentary on gender roles. its by no means a feminist masterpiece, and its not going to radicalize kids who watch it, but it conveys a subtle, heartfelt message that deserves more appreciation. the characters struggle with the concept of gender in a very accurate way for their age, making off-base comments and feeling trapped by the weight of expectations they cant quite put their finger on. we watch them feel both at odds with and relieved by the gender roles they are expected and allowed to perform in each others bodies, and one of the most interesting parts of the movie to me is their interactions with the other kids around them. as a result of their feeling out of place in each others environments, the kids inadvertently change each others friendships for the better by introducing new communication styles and brave authenticity.

the value of this movie is the subtle, but genuine way it shows the characters growing through being given the space to act in conflicting ways to their expected norms. ellie realizes that relationships dont have to be complex, confusing, and painful, and that its okay to not live up to appearances and images. jack learns that emotional expression is good, healthy, and especially essential to the grieving process. one of the most powerful scenes in the movie comes at the end where, after ellie confronts jacks dad in his body, jack returns as himself to a very heartfelt apology from his father for being too hard on him; the explicit message (”boys can cry”) is paired with an open expression of love and appreciation for his kids that he didnt feel comfortable displaying until his son set an example through honest communication. this is such an empowering scene and overall an empowering movie for kids who may feel stuck in their expected roles, as it sets a positive example for having the courage to break the restrictive societal mold. for its overall message of the importance of introspection and emotional intelligence, the swap is extremely underrated.

2. Freaky Friday (2018)

this is my favorite dcom, and probably my favorite movie at this point. ive always assigned a lot of personal value to this movie (and i love every freaky friday in general), for the message of selfless familial love and understanding. i know i can get carried away talking about this topic; i got an anon ask MONTHS ago asking me about the freaky friday movies and i wrote a super super long detailed response that i never posted bc i didnt quite finish talking about the 2018 movie. and thats bc on a personal level, i cant adequately convey all the love i have for this movie. so i will try to keep this short.

first lets state the obvious: the reason people dont like this movie is bc its not the lindsay lohan version. and i get that, to an extent, bc i also love the 2003 version and its one of my ultimate comfort movies, and grew up watching it and ive seen it a billion times. i even watched it a couple days ago. but the nostalgia goggles that people have on from the early 2000s severely clouds their judgement of the wonderful 2018 remake.

yes, the 2018 version is dorky, overly simplistic plot wise, a bit stiff at times, and super cheesy like any dcom. the writing isnt 100% all the time. the narrative takes a couple confusing turns. the song biology probably shouldnt have been included. i understand this. but at the heart of it all, this movies value is love. and its edge over all the other freaky friday movies is the songs.

on a personal level, the movie speaks heavily to me. i cried very early into my first viewing of the movie bc i got to see dara renee, a dark-skinned, non-skinny actress, playing the mean popular girl on disney channel. that has never happened before. growing up, i saw the sharpays and all the other super thin white women get to be the “popular” girls on tv, and ultimately they were taken down in the end for being mean, but that doesnt change the fact that they were given power and status in the first place for being conventionally beautiful. so, watching dara renee strut around confidently and sing about being the queen bee at this high school got to me immediately. and in general, the supporting cast members of color really mean a lot to me in this movie. we get to see adam, an asian male love interest for the main character. we have a second interracial relationship in the movie with katherines marriage to mike. ellies best friend karl is hispanic. and we see these characters have depth and plot significance, we see them show love, care, and passion for the things they value. the brown faces in this movie are comforting to me personally. additionally, the loving, blended family dynamic is important to me as someone in a close-knit, affectionate step-family.

but on a more general level, this movie is underrated for its skillful musical storytelling and the way it conveys all kinds of love and appreciation. in true freaky friday fashion, we watch ellie and katherine stumble and misstep in their attempts to act like each other. its goofy and fun. but through it all, the music always captures the characters’ intimate thoughts and feelings. the opening song gives us a meaningful view into ellie and katherines relationship and the fundamental misunderstandings that play a role in straining their connection. ellie sings about how she thinks her mom wants her to be perfect, and her katherine sings about all the wonderful traits she sees in her daughter and how she wants her to be more open and self assured. this is meaningful bc even as theyre mad at each other, the love comes through. the songs continue to bring on the emotional weight of the story, as ellie sings to her little brother about her feelings of hurt and abandonment in her fathers absence. the song “go” and its accompanying hunt scene always make me cry bc of the childlike wonder and sense of adventure that it brings. for the kids, its a coming of age, introspective song. for katherine who gets to participate in ellies body, its a reminder of youth and the rich, full life her daughter has ahead of her. she is overcome with excitement, both from getting to be a teenager again for a day, and from the realization that her daughter has a support network and passions that are all her own. today and ev’ry day, the second to last song, is the culmination of the lessons learned throughout the movie, a mother and daughters tearful commitment to each other to love, protect, and understand one another. the line “if today is every day, i will hold you and protect you, i wont let this thing affect you” gets to me every time. even when things are hard and dont go according to plan, they still agree, in this moment, to be there for each other. and thats what all freaky friday stories are ultimately about.

freaky friday 2018 is a beautiful, inclusive, subversive display of familial love, sacrifice, and selflessness, and it is underrated and overlooked because of its more popular predecessor.

1. Let It Shine (2012)

this is another one of my favorite dcoms and movies in the whole world. unlike the other movies on this list, it is not the viewers themselves that contribute to the underrated-ness of this movie. disney severely under-promoted and under-hyped this movie in comparison to its other big musical franchises, and i will give you five guesses as to why, but youll only need one!

let it shine is the most beautifully, unapologetically black dcom in the whole collection. (i would put jump in! at a notable second in this category, but that one wasnt underrated). this movie was clearly crafted with care and consideration. little black kids got to see an entire dcom cast that represented them. the vernacular used in the script is still tailored mostly to white-favoring audiences, but with some relevant slang thrown in there. in short, the writers got away with the most blackness they were allowed to inject into a disney channel project.

the story centers on rap music and its underground community in atlanta, georgia. it portrays misconceptions surrounding rap, using a church setting as a catalyst for a very real debate surrounding a generational, mutlicultural conflict. this was not a “safe” movie for disney, given its emphasis on religious clashes with contemporary values. it lightly touches on issues of image policing within the black community (cyrus’s father talking about how “our boys” are running around with sagging pants and “our girls” are straying away from god), which is a very real and pressing problem for black kids who feel the pressure (from all sides) of representing their whole race with their actions. its a fun, adorable story about being yourself and staying true to your art, but also a skillful representation of struggles unique to black and brown kids and children from religious backgrounds.

on top of crafting a fun, wholesome, thoughtful narrative and likeable protagonists, let it shine brought us what is in my opinion the BEST dcom soundtrack of all time. every single song is a bop. theyre fast, fun, and lyrically engaging. “me and you” is my favorite disney channel song of all time due to its narrative significance; i will never forget my first time watching the movie and seeing that big reveal unfold onstage, as a conversation and a plot summary all wrapped into a song. the amount of thought and care that went into the music of this movie should have been rewarded with a level of attention on par with that of other musical dcoms.

if disney channel had simply cared about let it shine more, it couldve spanned franchises and sold songs the way that other musical dcoms have drawn in success. i would have loved for a sequel that explored and fleshed out cyrus’s neighborhood a little bit more, and maybe dipped into that underground scene they caught a glimpse of. i wanted a follow up on the changed church community once cyrus’s father started supporting his sons vision. i want so much more for these characters and this world than disney gave them in just one movie.

for its bold, unabashed representation of blackness and religion, subtle, nuanced presentation of race-specific issues, strong, likeable characters, and complex, thoughtful songs, let it shine is the most underrated dcom.

and because i made a full list before i started writing this post, here are some honorable mentions:

going to the mat (2004)

gotta kick it up! (2002)

tru confessions (2002)

dont look under the bed (1999)

invisible sister (2015)

#this took me embarassingly long to write#i cant help myself i literally think about this all the time#youre doing a great job with these questions secret santa!#dcoms#disney channel#answered asks#anons#gcwca secret santa#Anonymous

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

Something that’s been on my mind for a bit that your professional word may be able to help with. Would you happen to know how ethnically diverse the Greek and Roman empires were?

very

next question please

…

…what, you want more? Oh, fine, but for the record this is not the sort of thing people just “happen to know.”

Okay so I’m assuming by “Greek empire” (remember, kids: there was never a politically autonomous and unified state called “Greece” or “Hellas” until 1822) you mean Alexander’s empire (320s BC) and the Hellenistic successor kingdoms (323 BC – 31 BC), and by “Roman empire” you mean Rome starting from the time it becomes a major interregional power (say, following the second Punic War, which ended in 201 BC) rather than just Rome in the time of the Emperors. You could spend like most of a book on each of these just corralling the data that might let us answer this question, but whatevs.

Lesson one: the ancient Greeks and Romans did not think about ethnicity in the same way as we do. In particular, they were not super hung up on the colour of people’s skin – skin colour in ancient art is more often a signifier of gender than race, because women are expected to spend less time outside and therefore have lighter skin (which is another whole thing that we shouldn’t even get into because this is an aristocratic ideal of female beauty and of course lots of Greek and Roman women would have worked outside). Arguably the most important signifier of ethnicity to the Greeks and Romans was actually language, with everyone who didn’t speak Greek or Latin being a “barbarian” (traditionally this word is supposed to come from the Greeks thinking that all foreign languages sounded like “bar bar bar,” although I’ve also heard a convincing argument that it comes from the Old Persian word for taxpayer, barabara, and originally signified all subjects of the Persian king).

In the modern world we have designations of ethnicity that are super broad and grow in large part out of early and long-since-debunked anthropological theory that divided humanity into three biologically distinct races, Caucasoid, Mongoloid and Negroid, and don’t really reflect a lot of important components of ethnicity. The thing is, as the internet will happily tell you ad nauseam, race is a social construct. Like, yes, designations of race describe real physical characteristics that arise from variation within human genetics, but the way we choose to bundle those characteristics is arbitrary, and where we choose to draw the lines is arbitrary (like, for a long time in the US, Greeks and Italians weren’t considered “white,” but today they definitely are, even though nothing changed about their genetics). If we today were brought face to face with a bunch of ancient Greeks and Romans, we would probably be pretty comfortable with assigning a majority of them to the big pan-European tent of modern “whiteness,” but if you had asked them about it, they certainly would not have felt any kinship with the pale-skinned people of northern and western Europe from whom most English-speaking white people today are descended. Those people were every bit as barbarian (and every bit as fair game for enslavement, for that matter) as the darker-skinned folk of the Middle East and North Africa. Ancient Greeks and Italians also had loads of internal ethnic divisions – like, the Latins (the central Italian ethnic group to which the Romans belonged) were a different thing from the Umbrians to their east, the Etruscans to the north and the Oscans to the south. In Greece, you had Dorians in the Peloponnese, Ionians in Attica and Asia Minor, Boeotians and Thessalians in central Greece, Epirotes in western Greece, and DON’T EVEN ASK about the Macedonians, because boyyyyyyyyy HOWDY you are NOT ready for that $#!tstorm. The point is, race and ethnicity can be basically anything that you think makes you different from the people in another community.

So yeah, Alexander’s empire. Alexander the Great conquered Persia, which was already the largest empire the world had ever seen at the time and incorporated dozens of ethnically distinct peoples (including many Greeks of Asia Minor, some of whom willingly fought against Alexander) through a philosophy of loose regional governance and broad religious tolerance. Now, here’s the thing: Alexander had no idea how to run an empire of that scale. No Greek did. No one alive in the world did – except for the Persians. Alexander didn’t have anything to replace the Persian systems of governance or bureaucracy, so… he didn’t. Individual Persian governors were usually given the opportunity to swear loyalty to him and keep their posts; vacant posts were filled with Macedonians, but the hierarchy was basically untouched. Alexander himself married a princess from Bactria (approximately what is now Afghanistan), Roxana, and had a kid with her, and encouraged other Macedonian nobles to take Persian wives as well, to help unify the empire. Unfortunately Alexander, of course, had to go and bloody die less than two years after he’d finished conquering everything, and tradition holds that on his deathbed he told his friends that the empire should go “to the strongest,” which was an incredibly dumb thing to say and caused literally decades of war, which we are not even going to talk about because it is the most Game of Thrones bull$#!t in the history of history. All you need to know is that when the dust settled there were basically three major Greco-Macedonian dynastic powers: the Antigonids in Greece, the Ptolemies in Egypt, and the Seleucids in Persia.

In terms of ethnic makeup the Antigonid kingdom is in principle the most straightforward because they’re basically still running the same Greece that Alexander’s father had conquered. Even then, you should bear in mind that a) most Greek cities had legal provisions for allowing foreigners to live there under certain conditions (“foreigners” often meant Greeks from other cities, but in principle could be anyone), and b) the Greeks had a lot of slaves (many of whom were, again, Greeks from other cities, because that’s fine in ancient Greek morality, but a lot of them would have come from all over the place), and even though the Greeks didn’t count slaves as “people” or consider them a real part of a city’s ethnic composition, WE SHOULD. The Ptolemaic kingdom in Egypt seems to have had a relatively small Greco-Macedonian upper class ruling over a native Egyptian, Libyan and Nubian peasant majority. Members of that ruling class seem to have been kind of snobbish about any mixing between the two – only the very last Ptolemaic ruler, Cleopatra VII (yes, that Cleopatra), even bothered to learn the Egyptian language. However, the Ptolemaic rulers did make some important cultural gestures of goodwill towards the Egyptians. They took the native title of Pharaoh, which previous foreign rulers of Egypt hadn’t, and adopted a lot of traditional Pharaonic iconography like the double crown. They also worshipped some of the most important Egyptian gods, most notably Isis, and may have kind of… deliberately created a new Greco-Egyptian god, Serapis, by blending together Osiris and Dionysus (Serapis actually becomes super important in the Roman period and is widely worshipped even outside Egypt). And then there’s the Seleucids, an empire that did nothing but slowly collapse from the moment it was established. They have a rough time of it because they have the largest land area to cover and dozens of distinct ethnic groups to bring together, and it doesn’t help that they kinda keep doing the Game of Thrones thing for about two hundred fµ¢&ing years. They often get a bad rap in history and have a reputation for oppressing the non-Greek populations of their empire, but that’s probably at least partly because some of our most important sources for the Seleucids are Jewish, and the Seleucid kings’ relationship with the Jews broke down in a fairly spectacular fashion during the reign of Antiochus IV Epiphanes (r. 175-164 BC). It’s not clear whether that’s representative of the Seleucids’ normal relationship with their subject peoples, or a worst case scenario. Also, the Seleucids tend to get painted as villains in the historical record by both the other Greek powers and the Romans, and never really get much of a chance to defend themselves because we don’t have Seleucid histories. What is clear is that they inherited all the ethnic and religious diversity of the Persian Empire, and most of their rulers were half-Persian because they followed Alexander’s example by marrying into the Persian nobility. After an initial period of conflict they also seem to have maintained cordial relations with the Mauryan Empire of India, their neighbour to the east, for several decades, and contemporary Indian sources talk about sending Buddhist missionaries into Seleucid lands, so… like, there might have been a bunch of Greek Buddhists running around the empire; that’s a thing.

Whew. Okay, so that is a criminally brief answer to-

OH CHRIST YOU ASKED ABOUT THE ROMANS AS WELL

WHAT DO YOU PEOPLE WANT FROM ME

Right. Romans. One of the major schools of thought on how the Romans were able to create such an enormous and long-lasting empire in the first place is that their openness to accepting foreigners into their community gave them an enormous manpower advantage over every other ancient Mediterranean state. Greek politics generally operates on the level of cities; even in the age of Alexander, individual cities have quite a lot of legislative autonomy. Citizenship is also something that works on the level of cities: you aren’t a citizen of, say, the Seleucid Empire; you’re a citizen of Antioch, or Tyre, or Babylon, or whatever. But then the Romans happen. The Romans are weird, because they will sometimes just declare that all the people of an allied city are now also citizens of Rome. In the early period of Rome’s expansion in the central Mediterranean, this meant (or so the theory goes) that they could draw upon larger citizen armies and sustain more casualties than their rivals. This is how they beat Pyrrhus, the Greek king of Epirus (r. 297-272 BC), when he invaded Italy in response to disputes between Rome and the Greek colony of Tarentum; this is how they beat Hannibal, the legendary Carthaginian general, even after he annihilated the largest army the Romans had ever fielded at Cannae during the second Punic War (218-201 BC). Now, at this point they are basically still just bringing in Italians, which we might consider ethnically homogenous even if they didn’t, but there’s more.

Once they really start to get going, the Romans enfranchise entire provinces at a time, like when the emperor Claudius (r. AD 41-54) decided to make everyone in Gaul (modern France, more or less) a Roman citizen. The really interesting thing about this particular decision is that we actually have a copy of the speech he made to the Senate in Rome at the time, so we can examine his rationale. Claudius’ argument is basically that being inclusive has always been what has made Rome stronger than its rivals, going right back to their mythological past, when Romulus populated his city with disenfranchised criminals from other communities (and, uh… women that they kidnapped from the next town over). The Romans believed that everything great about their civilisation had originally been learned or borrowed from someone else – metalworking and irrigation from the Etruscans, infantry combat from the Greeks, shipbuilding from the Carthaginians, etc – so it wasn’t a huge stretch for them to believe that all these people should eventually become part of Rome as citizens (well… the ones who weren’t killed or enslaved in the conquest, anyway – no one ever said the Romans were saints).

The reason Claudius feels he needs to justify all this to the Senate is that citizenship (rather than any of the forms of semi-citizen rights that Romans would sometimes grant to their allies) will make rich Gauls eligible to become Senators themselves, and occupy other high-level posts like provincial governorships. The decision affects the ethnic composition of the Senate, so even though he doesn’t actually need their permission to do it, he asks as a courtesy (the emperors’ relationship with the Senate is a weird and complicated thing). Even without being a citizen, you could actually do a great deal in the Roman government in Claudius’ time. Many of the most important jobs in the empire were ones that had existed during the age of the Republic, when Rome was theoretically a democracy, and all of those were restricted to citizens even after they stopped being elected positions – but there was also an imperial bureaucracy that answered directly to the emperor and his aides, and he was free to choose literally anyone to fill those positions. As a result, a lot of emperors deliberately picked slaves and former slaves for loads of senior positions, specifically because their lack of citizen rights meant that they could never be political rivals, and because they were a useful counterbalance to the power of the blue-blooded Roman aristocracy. And, again, slaves can be from basically anywhere. A lot of these administrative slaves were Greeks, because Greek education provided useful skills for running the imperial bureaucracy that the Romans themselves often didn’t have, but emperors could and did commission literally anyone for these positions.

Eventually the emperor Caracalla (r. AD 211-217) just decided it wasn’t worth keeping track anymore and declared that every freeborn person in the entire empire, which by that point stretched from northern England to Morocco to Romania to Jordan, was now a Roman citizen. All of these people are now “Romans,” regardless of their language or culture or religion; the only criterion is that they not be slaves or former slaves (and even if they’re former slaves, their children will be Roman citizens). And these people can move, in ways that were never possible before the Empire existed, because Rome is the first – and so far the last – political entity ever to unite the entire Mediterranean region, which allows them to wipe out piracy almost completely and jump-start trade and travel in ways that would never happen again for over a thousand years. My own research on Roman glass has led me to encounter glassblowers with Syrian or Jewish names working in northern Italy – people who were probably integral to spreading the technology of glassblowing to western Europe. The Roman army also moves people around – like, a lot. You might enlist in your home town in Syria, then serve on Hadrian’s wall and retire in northern England – in fact, we know that this happened because we’ve found stuff like inscriptions in the Aramaic language in Roman Britain.

Also Rome had, like… a whole dynasty of African emperors one time. Septimius Severus (r. AD 193-211) and his successors were part Italian, part Punic (of Carthaginian descent – ultimately Middle Eastern, since the Carthaginians were originally a Phoenician colony) and part Berber (native North African), and Severus grew up in what is now Tunisia. And that wasn’t really a big deal for the Romans, 1) because Severus’ Italian ancestry made him a Roman citizen, which trumps all other signifiers of ethnicity, and 2) Rome had already had a couple of emperors of Iberian (= Spanish) descent by this point who were considered some of the best ever, and the Iberians are just as “barbarian” as the Berbers as far as Rome is concerned. Other Roman emperors of varied ethnicities include Philip (Arabian), Diocletian (Illyrian), the three Gordians (probably Cappadocian), and Elagabalus (Syrian, and incidentally the gayest Roman of all time; like, normally I would warn you to be super cautious about using modern labels like “straight” and “gay” for Romans because they just didn’t think about sexual orientation in those terms, but I make an exception here because Elagabalus was super gay).

Oh, and just because someone will definitely bring it up if I don’t, there was a big fuss in the news a few years back because someone discovered the skeletons of what they claimed were Chinese people living in, of all places, Roman Britain. And to me, one Chinese family in Britain in the first century AD is not particularly a dramatic stretch of plausibility (a handful of people could easily slip through the historical record and just never be mentioned), but the evidence in this particular case falls some way short of “proof.” There’s chemical data that suggests these individuals grew up somewhere far away from Britain, which is well and good, but the thing that points specifically to China is not the isotopic analysis but a study of bone morphology, and trying to determine someone’s ethnicity on the basis of what their bones look like, on the universal scale of things that are sketchy, ranks “sketchy as all fµ¢&.” Again, I’m happy to believe that they exist, because China (Seres in Latin) and Rome (Dà-Qín in Chinese) definitely knew about each other, and we occasionally find Roman artefacts and coins in eastern Asia, or Chinese artefacts in the eastern Roman Empire, but the specific evidence for these individuals isn’t there, in my opinion.

…that was a brief answer. Let it stand as a warning to others.

932 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝕬 𝖕𝖗𝖎𝖒𝖎𝖙𝖎𝖛𝖊 𝖜𝖔𝖗𝖑𝖉

Definition/Understanding → Research → Comparison/Reflection → Narrative & Character

A question that has kept occurring in my head whenever “primitive” has been mentioned is, what exactly is it? What is a primitive world? What makes it primitive- and what does it look like?

When I think of a ‘primitive world’, I immediately start thinking of the early stages of civilisation; primitive civilisation.

Source: ScienceDirect.com - International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, reference work

In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (Second Edition), 2001, written by Alexander F. Robertson, he describes “Primitive” as following;

“‘Primitive’ is a term from the evolutionary vocabulary of the nineteenth century that in popular understanding still identifies the interests of the modern discipline of anthropology. Anthropologists have sought to come to respectful terms with their ‘Primitive’ subject matter by redefining it in terms of a distinctive social structure, culture, spatial distribution, and type of livelihood. But despite efforts to set aside disparaging contrasts between primitive society and modern civilisation, evolutionary assumptions about human progress remain embedded in both scientific and humanistic approaches to society.”

When reading this, I was intrigued by the idea of how we as a society choose to interpret and understand the word; [primitive]. The way that it’s a modern way of understanding something ancient, as if we are looking back at something through a veil, based on the fact that we are so far and ahead from our ancestors, in an evolutionary sense, that we define them by what tools they used. (ex. stone age)

Further, Alexander F. Robertson also describes “Primitive Society” as such;

“In popular usage, ‘primitive society’ distinguishes ourselves from other people who have made little progress toward what we understand as civilization. There are very few such people left today: they live in scattered communities in deserts or rainforests, and they interest us mainly because we think of them as the living relics of our own distant ancestors. The comparison is usually unflattering. Until the beginning of the nineteenth century ‘primitive’ simply meant ‘first’ or ‘earliest,’ but as the word was applied to the original inhabitants of territories colonised by European and American states, it acquired the connotations of inferior, backward, rude.”

As for when I reflected upon his first quote, this sort of applies to this second quote. I find it incredibly interesting to think about the way in which not only us as the more modern society, but also how the societies prior to ours have interpreted this. The idea of something being the “first” and the “earliest” appearance of mankind; How that later was used against the people, using their way of living as an insult of them being “lesser”.

Early civilisations research:

Identify the variety of early civilisations → Choose two → Time, where, what defined their way of living – remember to add visuals!

With a clearer understanding of what exactly a ’primitive world’ is based upon, I can’t help but want to look into the word “civilisation”. What ancient civilisations exist and what traces of their existence have their left behind?

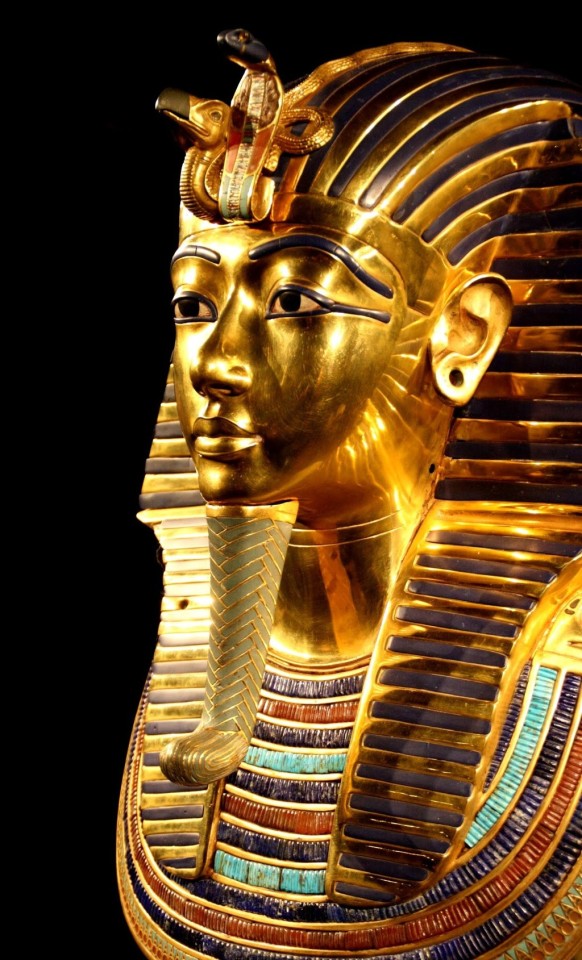

One of the obvious ones that immediately comes to mind are the Egyptians. They were an ancient civilisation, located in Egypt by the banks of the Nile. Their time of rule being 3150 BC – 30 BC (according to the conventional Egyptian chronology). They are said to have had a political understanding of their society, referred to as “Upper” and “Lower Egypt” under the first pharaoh. Though this was only possible because there were already settlers around the Nile banks and valley around 3500 BC. Their civilisation was rich, well known for their prodigious culture and their architecture, especially the pyramids and Sphinx.

They had a wide variety of things that defined their culture and way of living; this can be seen in the way that they made mummies which preserved ancient pharaohs and other important figures of the time to this very day. Hieroglyphs not only tells stories of their age and time, but also shows how their language was developed and used.

Tutankhamun’s Mask:

Narmer Palette:

Another ancient civilisation that came to my mind was the Maya Indians. I have researched them in the past for a written school project, so I already know a good amount about their culture.

The ancient Maya civilisation planted their roots in Central America at around 2600 BC – 900 AD. Once they had established themselves in present-day Yucatan, Mexico, they proceeded to prosper and become a sophisticated folk. By 700 BC, they Mayans had developed their own system of writing which they then used to create calendars of the solar system, all carved into stone.

According to the Mayans, the world was created on August 11, 3114 BC (the date of which their calendar begins), and the supposed end date was December 21, 2012.

This ancient civilisation was incredibly rich compared to many other civilisations of the time. They built pyramids, much like the Egyptians, but some of their buildings were even much larger than the pyramids.

It is still a complete mystery what happened to the Maya Indians. Their population suddenly began to rapidly decline. Why did the Mayans, a highly sophisticated and developed civilisation made up of more than 19 million people, suddenly collapse and disappear during the eighth or ninth century? What happened to them?. Despite this, there are still descendants of the Mayans that live in the central parts of America to this day.

From the last brief, we looked at a lot of narrative based things such as mythologies and folklores. One of the things I stumbled upon was the origin of the myth and folklore about the creature; wendigo. I didn’t further look into this, but this reminded me of it.

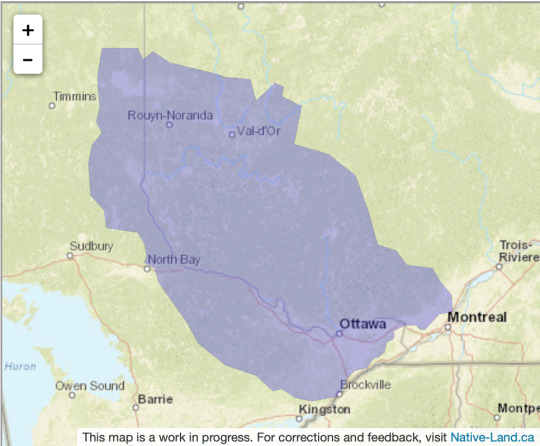

The folklore originates from the Native Americans, more specifically the tribe that goes by the name of “Algonquin”. The Algonquin people are natives from Canada and this folk lived and still to this day, live around parts of western Quebec and Ontario, centering themselves around the Ottawa River. Like the Mayans, there are still people identified as having Algonquin ancestry. (from 2016, 40,880 people).

- The Algonquin people have been known by various Europeans since 1603, first encountered by Samuel de Champlain.

Moose Hunt, artwork by Lewis Parker

Algonquin Canoe, artwork by Lewis Parker

Algonquin traditional territory

The Algonquin hunted, traded and lived in large areas of territories in the Eastern Woodlands Subarctic regions, being independent of one another. Like some of their relatives, the Algonquin used to live in disassembled birch bark dwellings, known better as wigwams.

They lives in communities where clans were represented by totems based on different animals such as crane, wolf, bear, loon etc. The clans had incorporated leadership provided by elders which were highly respected within each clan. Intermarriage within a clan was not permitted, even if the people were from different communities all-together.

Their language was known as Omàmiwininìmowin, which is part of the Algonquian language family. The root of this word is Omàmiwininì, which is often used by the community to describe Algonquin people overall.

Within the Algonquin language family are a wide variety of different languages such as Atikamekw, Blackfoot, Cree, Wolastoqiyik, Mi’kmaq, Innu, Naskapi, Ojibwe and Oji-Cree. Within all of these mentioned, the Algonquian language group was the language mostly spoken in Canada, with around 175,825 speakers. The majority of these speakers reside in;

Manitoba (21.7%)

the rest live in;

Quebec (21.2%)

Ontario (17.2%)

Alberta (16.7%)

Saskatchewan (16.0%)

Despite the language being quiet widespread amongst the clans/tribes, it is considered endangered today. Only 1,575 people identify the language as their mother tongue. Algonquin communities work hard to promote and preserve their language and culture through various different programs, such as language courses.

The Algonquin language is often linked to different names of places in Canada, with the reason being that many early French explorer mapped and thereby named features with Algonquin words. Ex. Quebec comes from the Algonquin word kébec, which actually means “place where the river narrows”.

𝖂𝖊𝖓𝖉𝖎𝖌𝖔

The original tale of the wendigo talks about a lost hunter that, during a cold winter, reached intense hunger which drove him to cannibalism to survive. After he had been feasting upon another humans’ flesh, he transformed, his body changing and becoming a humanlike-beast of the wilderness on the hunt for more human flesh to feast upon.

As mentioned earlier, this story originates from the Algonquin people. The details vary rapidly depending on who you ask, as most folklore and tales do. Some people that claim they have encountered this creature say it’s related to Bigfoot, but on the other end of the spectrum, some compare it too werewolves.

An animatronic depiction of a wendigo in a cage on display in “Wendigo Woods” in Busch Gardens Williamsburg, a theme park located in New France.

The mythological create that is the Wendigo is said to be a creature thriving in cold environments, supporting the fact that most of the many sightings of them have been reported in Canada and also the colder states to the North such as Minnesota. Around the turn of the 20th century, tribes people form the Algonquian tribe claimed that the disappearances of people is down the wendigos’ attacking them.

The wendigo is said to be around 15 feet tall (4.57 m.), the body often described as being skeletal or emaciated. A theory on this says that the creature is never satisfied with its cannibalistic urges and kills, obsessively hunting for new human victims and stuck being forever hungry.

Picture of Basil H. Johnston.

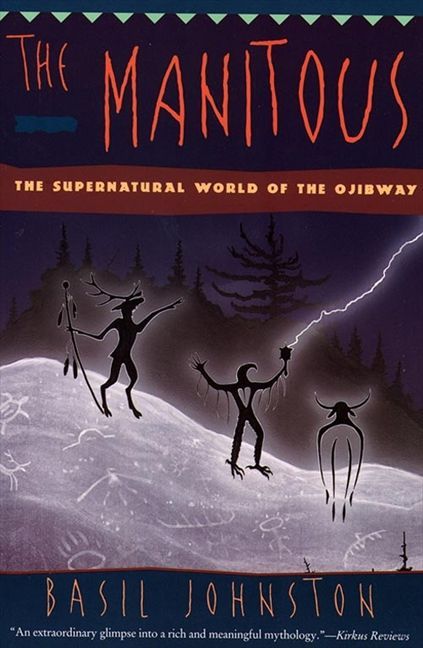

A Native author and ethnographer named Basil H. Johnston has described the Wendigo in his book The Manitous as:

“The Wendigo was gaunt to the point of emaciation, its desiccated skin pulled tightly over its bones. With its bones pushing out over its skin, its complexion the ash gray of death, and its eyes pushed back deep into the sockets, the Wendigo looked like a gaunt skeleton recently disinterred from the grave. What lips it had were tattered and bloody… Unclean and suffering from suppurations of the flesh, the Wendigo gave off a strange and eerie odor of decay and decomposition, of death and corruption.”

The front cover of Basil H. Johnstons’ book The Manitous, published 1995.

According to Nathan Carlson, an ethno-historian, it has also been said that the deadly cannibalistic creature has large, razor sharp claws and massive eyes, much like and owl. But some people prefer to describe it (the wendigo) as a skeleton-like with skin in the colour of ash. But no matter which version of the wendigo’s appearance seems the most accurate and possible, it is most obviously not a creature you’d want to run into anywhere in the wild.

Another thing that I found quite interesting about the Native Americans in general was the way that their belief reached a spiritual level (spirit animals, animal totems etc.). I did some digging when looking into Animal Totems and sacred Spirit Animals in Native American belief;

According to this website (Legends Of America, Exploring history, destinations, people, & legends of this great country since 2003.), there is a huge list of different animals involved with the Native belief. A totem (a spirit being) is considered a sacred object or a symbol for a clan, tribe, family or even just an individual. Some tribes and their traditions proves that each person is somehow connected with nine different animals, also known as spirit guides or power animals, that will accompany the person through their life. Each animal represents something different, meaning that they move in and out of ones life, depending on what path or direction you take in life and the journey.

The same tribes also believe that totem animals is one that i always with you in your life, physically and spiritually. In other words, the totem animal that you are given acts as the main guardian of all your spirits. With this animal, a connection is shared and created, either through an interest in the said animal, the characteristics, dreams or other interactions (ie. with the animal in the physical world).

Because the list is quite long, the entirety of it can be found here.

Restored Piasa Bird carving, located along the Mississippi River, near llinois River.

Sources:

thecanadianencyclopedia.ca “The Canadian Encyclopedia, Algonquin”

allthatsinteresting.com “The Native American Legend Of The Wendigo — The Frostbitten Monster Of Your Nightmares By; All That's Interesting”

legendsofamerica.com “Exploring history, destinations, people, & legends of this great country since 2003.”

From studying these different early periods of civilisation, I have decided to choose just two of them to inspire my diorama; Mayans (the fact and idea that this blossoming civilisation suddenly disappeared without a trace as to tell why) and Native Americans (most specifically the Algonquin tribe and their folklore).

0 notes

Text

On the Rez Transcript

CARRIE: Hi, and welcome to The Vocal Fries Podcast, the podcast about linguistic discrimination.

MEGAN: I'm Megan Figueroa.

CARRIE: And I'm Carrie Gillon. Today we have our second guest: Dr. Peter Jacobs.

MEGAN: Hi Peter!

PETER: Ha7lh skwayel.

CARRIE: Hi. Peter Jacobs is a professor at Simon Fraser University and he works on language revitalization. He's a speaker of Squamish and also Kwakw’ala, right?

PETER: Right.

CARRIE: Very excited to have you on the show. Also I have known Peter for 20 years. That's when I first started working on Squamish, as a very young, 21-year-old undergrad.

MEGAN: Peter, you're also a member of the Squamish Nation, right?

PETER: Yes.

CARRIE: Yes, that's also important. So today we're gonna talk about a bunch of different things: a little bit about Rez English, a little bit about Indigenous languages spoken in Canada and the United States, language revitalization - just whatever comes up. But those are our main topics. Let's just start with Rez English. So why did we want to talk about Rez English or Indigenous languages? Well first, because we barely talk about it in the wider culture. In fact we kind of ignore Indigenous peoples, especially in the United States, completely. It's almost like they're gone. So, to talk about people that still exist, damnit, and still speak different varieties of English, but also different languages. So what features does Rez English even have? Because, if you think about it, it's people from all over North America, excluding Mexico, that originally, and still do in some cases, speak a different language. So what are the shared features in common?

PETER: Just like anything I think, there's regional Rez Englishes.

CARRIE: Yes.

PETER: Because I come from two different language groups in BC, I know the Rez English of these two different areas. My first story is: I was down in Arizona a number of years ago with my cousins from Squamish, and we met a relative of mine who is from my mom's side of my family. She lives in the Phoenix area. We hadn't seen each other for a while. We start talking. After we're done, we left. My Squamish cousin said, “Wow, did your English ever change when you and your cousin from North Vancouver Island started talking!” I was never aware of how different they were. I’m not exactly sure what all those things are.

CARRIE: Right.

MEGAN: So you say that you can speak two different Rez Englishes?

PETER: Yes.

MEGAN: Do you find yourself code-switching then? So you know when you're doing it? Do you speak them at certain times? Are you conscious of it at all?

PETER: I've become more conscious of it as I've gotten older. I think that was one instance where I really became aware that people noticed my Rez Englishes. But my nephew now, who's a young adult, we were up on the North Vancouver Island, on my mom’s side of the family, and he was commenting, because he actually has another Rez English from even further up Northern BC. He was doing this really insightful analysis of how people talked in all of these different situations. I thought it was really quite brilliant, as a young person. But he was at the advantage of having three, not just two, plus standard English.

MEGAN: I like what you're saying about your nephew, because it reminds me that everyone's a linguist in a way. We can call ourselves linguists, but it's, I think, a term that can be applied to anyone that uses language. We all notice these things, because we all speak it, or sign. We all have language. I thought that was very cool.

PETER: I think one of the defining things is probably some type of intonational patterns that people use. I don't know enough about intonation to say what they are, but if someone really exaggerates it - and we do, sometimes really exaggerate it - I think that's what it's really picking up on, it's certain styles of intonation. I don't know if that's interplay between our parents’ or grandparents’ first language, or what. I have never ever gone that far to find out.

CARRIE: Yeah, the very little research that there is seems to suggest that, at least in the United States, it has to do with people coming from different languages and learning English together. So they all have the same intonation pattern. They call it a contour pitch accent, and since I also don't know that much about prosody and intonation, I can't replicate it at all.

MEGAN: And it was them coming together to learn English in horrible conditions being boarding schools, correct?

CARRIE: Boarding schools, here in the United States, and residential schools in Canada. And yeah, they are horrific.

MEGAN: Right. So this forcing of English on speakers of other languages, trying to eradicate indigenous languages.

CARRIE: Right, trying to beat the Indian out of them, for example.

PETER: Yes, literally and figuratively.

MEGAN: Right. Peter, did your parents go to in boarding schools? That's a thing in Canada, as well.

PETER: Yes.

CARRIE: Yeah, they're called residential schools.

PETER: Yes, I think most of my aunts and uncles and my parents and some of my grandparents went to residential school. My mum's first language is Kwakw’ala, and I don't think she learned English until she went to school. My grandfather - one of my grandfathers - went to residential school. He ironically also learned Nlaka'pamux, which is the local language of where the residential school was, which is an Interior Salish language, and he was a speaker of Squamish. And he also learned English. He used to say though that they beat Jesus into us one day of the week and then they beat him out the other six.

CARRIE: Wow. Oh god that’s horrible.

MEGAN: Oh no.

PETER: The Lord works in mysterious ways.

MEGAN: That’s what that quote means; I get it now.

PETER: An interesting thing, I was just thinking about lexical items, people - like the Squamish, like the southern part of BC, and also in Washington, and I found out in Oregon, we all use “innit”. We all say it similarly: “innit?!” I think what's-his-name from Spokane, he has it in his books. It was in Smoke Signals.

MEGAN: Sheman Alexie.

PETER: Sherman Alexie. When I went to see Smoke Signals, and the characters were using “innit”, and they were using it perfectly right, I just broke out - I actually was hysterically laughing in the theater, because I'd never seen anybody speak Rez English on the screen, eh. It was always this kind of - people always did this kind of stilted English that was supposed to be Native American English, or something like that. But this is people really speaking like how we do today, and it just cracked me up.

ADAM BEACH: Don't you even know how to be a real Indian?

EVAN ADAMS: I guess not.

ADAM BEACH: Well shit, no wonder, geez. I guess I'll have to teach you then, innit.

MEGAN: That movie actually had good representation of Rez English?

PETER: Yes.

MEGAN: It did? Ok, well.

PETER: Yeah well, because Evan Adams is really from here in BC.

CARRIE: Yeah. He’s a local boy.

MEGAN: What is an example of “innit” in a sentence?

PETER: People say that it comes from “isn't it?”, and I guess it probably does at some level.

MEGAN: Ohhhh.

PETER: But you know someone says something, someone did something kind of stupid, and you're all kind of laughing at it, and I go, “innit?” Obviously I don't know how to translate it. “Innit?”

CARRIE: Yeah, it’s difficult to translate.

PETER: I went to University of Oregon for three years, and I was part of the Native American Student Union, and there was a Navajo student there who had gone to boarding school in Oregon. And we were just sitting around in our little office there, our little space, and just getting to know each other, and then she just said it. She just said “innit”, and it was sort of context for me. I'd never heard anybody - because my mom's side of my family up in Northern BC, they don't use it, and they don't recognize it. It really is certainly a marker of being part of a community. It made me laugh, quite hard.

CARRIE: One of the other things that I noticed, or read about, is that at least in some communities, the intonation used for yes/no questions - so yes/no questions are questions where the answer would be “yes” or “no”, like, “are you hungry?” - in many Rez Englishes, it would sound more flat. “Are you hungry.” Whereas most other speakers of English are going to say “are you hungry?” I think that's related to the fact that, at least in some Indigenous languages, like Squamish, the intonation is flatter for a yes/no question.

PETER: Yeah. It would take me time to do some introspection to think of - because you have to imagine yourself talking to someone that shares the same English, and then how would you talk to each other, like that, if you were trying to be on the inside.

MEGAN: How old were you when you learned Squamish?

PETER: Well, I knew a lot of words, individual words, but I didn't become conversant until my late twenties, when I was working on the dictionary. That took a long time, because I was just doing elicitation of words and sentences, and it wasn't really a communicative context. And then students, like Carrie and others, came in and they were also doing elicitation. So in a way - I was just saying to something the other day - I became a speaker of Squamish through elicitation.

MEGAN: Wow.

PETER: Which is a fairly privileged position, because I had the opportunity to do that, which most people don't. And it takes a long, long time to do it that way, because the input is kind of one-sided, eh.

CARRIE: Are there any Kwakw’ala-specific features - the “innit” thing is sort of more Salish-y, I'm guessing. Are there any Kwakw’ala-specific features that you have in your Rez English?

PETER: There's things that seem to travel around, these generational things, like people used to - not just Kwakw’ala - but a lot of different Rez Englishes had ‘nih’. Have you heard ‘nih’?

CARRIE: Uh-uh.

PETER: Yeah, I don't use it, but I would recognize what people are trying to say when they say “nih”. It's kind of the generation below me, but it seemed to travel around, eh. So maybe some Rez English things started to travel more as people were having more contact with people regularly, and sports, and intermarriage and everything.

MEGAN: To clarify for listeners: you do not have to speak an Indigenous language to speak Rez English, correct?

PETER: No, not at all.

MEGAN: And in fact - unfortunately, the way that things are - they are probably more Rez English speakers than there are bilingual English and Indigenous.

PETER: Sure. For most of us, Rez English is our first language. And then we learn standard Canadian English, or whatever. French and stuff.

MEGAN: And then at some point you may learn your tribal language, but a lot of times that comes later in life for people, is that right?

PETER: Yeah, things are changing, and there's a lot more going on than there was even like 20 years ago when Carrie started working with Squamish.

CARRIE: Yeah now there's an immersion school, so kids are getting more at least. Also “tribal” is not a word we use in Canada.

MEGAN: Oh what do you use?

CARRIE: Nation, I guess.

MEGAN: So, national language? If you're doing adjectival?

PETER: That’s a good question.

MEGAN: First Nation language.

CARRIE: First Nations language, I think you would say. Or if it's not First Nations, because again, if it's Inuit, they're not First Nations, they’re Inuit. They're separate. So: it's complicated. That's why I keep using Indigenous, because it's a sort of a catch-all for a much larger group.

PETER: You know until we all fall in line, we're just gonna have to wrestle with all of that, eh.

MEGAN: Oh I see you’re Canadian English coming out.

PETER: Yes. There's a question about Rez English, and I was having this conversation with Strang Burton. He said it could very well be that Rez English is a representation of how English was spoken many generations previously, right. So it's kind of fossilized or being maintained or something in in the community, because “eh” is very strongly used and on the rise.

CARRIE: Yeah, and less so in urban areas in Canada. I use “eh” sometimes but I don't have the full range of “eh” that Peter does.

PETER: I tried to teach her, but she just couldn't get it, yeah.

CARRIE: It’s true!

MEGAN: Is “eh” more of a rural thing then?

CARRIE: Yeah.

PETER: Yeah.

RICK MORANIS: Good day, welcome to the Great White North. I'm Bob McKenzie. This is my brother Doug.

DAVE THOMAS: How's it going, eh?

RICK MORANIS: Ok, our topic today is the great white north, cuz we gots like lots of mail, eh, like about it, eh. Ok, so.

DAVE THOMAS: By the way, this topic was my idea, eh.

PETER: People consciously try to get rid of it to sound less rural, because it's stigmatized.

MEGAN: What?

CARRIE: Yeah.

MEGAN: Of course.

PETER: So what happened for me that changed me, I might have gone that same route. When I was living in Oregon, people were constantly picking out whenever I used it, and then it made me use it even more, so now I have it. I was a young adult then, and it stuck with me.

CARRIE: That’s good. You should be proud of the “eh”.

MEGAN: Yeah!

PETER: I am.

CARRIE: I kind of wish I had it.

PETER: There's one other thing I wanted to say about Rez English. I don't remember particularly who it was, but someone did a master's project looking at Squamish English, and they looked at the pronunciation of the consonants and vowels and particular lexical uses of words, and stuff like that. What they found was - because Squamish people first learned English in the residential school system or through the church, from French nuns and priests, so there's an influence of French English onto the first people learning Squamish, like my grandparents’ generation. And then later, they were all Irish. So then there's an influence of Irish English on Squamish peoples. So it's a very Squamish-specific thing, because of the interaction of the Catholic Church and different generations of how they sent out missionaries to our Rezes.

CARRIE: If you can send me that master's thesis, because I think people might be interested in it. We could put something about it on our Tumblr.

MEGAN: Before we move on from Rez English - Smoke Signals, I listened to a clip of it. Would you say that the tone, the way that he speaks is the kind of tone that you're talking about? Or the intonation?

PETER: Yes. Oh yeah. Evan Adams, in particular. He worked pretty hard. He doesn't talk like that all the time. He's a doctor now.

CARRIE: Right, yeah, in Vancouver!

PETER: He's a medical doctor, and he has a big position looking at Aboriginal health in the province and that.

MEGAN: So we have a really good example to put in a podcast so people can listen to the kind of international patterns. Okay, yeah, I was listening to it; it's definitely noticeable.

EVAN ADAMS: You're in the 60s. Arnold Joseph was the perfect hippie, because all the hippies were trying to be Indians anyway. But because of that, he was always wondering how anybody would know when an Indian was trying to make a social statement.

CARRIE: To me, it sounds kinda normal, cuz you know, I've heard these accents my whole life. But yeah, I think it's really, really different if you're from here. Nobody really talks like that down here.

MEGAN: They did have some examples of Navajo speakers kind of having that international pattern as well. So maybe in Northern Arizona, instead of Southern we'd maybe hear it more.

CARRIE: Yes, you would. Speaking of Navajo - or Diné Bizaad, as it's known in its own language - I had a PhD student - I was on his committee - and he was working on speech pathology on the Navajo Reservation, because he's Diné himself. And he wanted to show, ok, what's normal for Navajo kids, and what's abnormal, so that speech pathologists would actually be able to distinguish between normal Navajo English versus a kid with some sort of disordered speech. This is really important and gets kind of lost because people want children to have only standard English. One of the things that he pointed out to me is that “class”, the word “class”, like “I'm going to class” is pronounced “tlass” [t��æs] by many Navajo English speakers. So it's a “tl” [tɬ] sound, which, hard to describe, but it's a very different sound from the “k”, “l” sounds. So anyway, I just thought that was interesting.

PETER: It sounds better. “tlass” [tɬæs]

CARRIE: It's one of my favorite sounds “tlass” [tɬæs], and you don't get to use it in English.

MEGAN: And it's really important that he's pointing those things out, because, if someone was ignorant to what Navajo English looks like, then they might see that as a symptom of disorder, if they put all these things together incorrectly. It tells a different story.

CARRIE: Exactly. That's exactly what he was trying to say.

MEGAN: That's really important work.

PETER: In generations previous to me who were learning English, there was certainly much more influence, because they were first language speakers of different languages. Their English inventory would be different. So people in a lot of northern communities didn't make a distinction between /s/ and /ʃ/ (“sh”). So, “shoes” would be pronounced “zoos”. That's changed now, because most people have English as their first language.

CARRIE: Yeah, that changes over time. Ok, so let's maybe switch to talking a little bit more about Squamish, Kwakw’ala, other Indigenous languages that we want to talk about. We already talked about Squamish, but what was it like learning Kwakw’ala?

PETER: Well, my dad's not a first language speaker of Squamish and so I didn't grow up learning the language from him. We just had some common words that we all knew, like “push” [poʃ] for “cat” and “skwemáy’” [sqwəmájʔ] for “dog” and “séxwa7” [sə́χwaʔ], because as a kid you could say “sexwa7”, which means “to pee”. So you could say it in public without embarrassing your parents. And “méchen” [mə́ʧən] for “head lice”. This small group of words that we all know - there's some plants that we knew, because we used to go and pick them, and so we knew the Squamish words for that. But in Kwakw’ala, though my mom is a first language speaker and everybody and all of our siblings and my grandparents - and so we went to visit them, people didn't speak English unless they were talking to us. And so I was surrounded by the language in a much, much different way than Squamish. I've done some immersion learning now in Kwakw’ala. Some of it is just feeling like things got are getting unlocked, like “oh yeah, that's what that word is” or “that's how you say that”. I'm not around it enough to have that all the time, but I think I'm somewhere farther along on Kwakw’ala in terms of exposure for my youth than Squamish, by far. However, like I said in that generation, everybody was Kwakw’ala speakers. Now, when we're doing counts out of like 8,000 people, there's probably maybe 150 who are first language speakers. So that's changed drastically in the last 20 years, eh.

CARRIE: Yeah that shows just how quick these transitions can be, these language shifts, as they're called.

PETER: Because when I was a kid there's probably like a couple thousand, eh.

CARRIE: So that leads us right into language revitalization, which is trying to stop that and turn the tide in the other direction, get people to speak the Indigenous language again. I know that you're involved with that. Do you want to talk about anything in particular: your research or a project that you're involved with.

PETER: Yeah you know a lot of a lot of our communities started with language activities in the 70s, and it was very much mirrored with what was going on for French at the time, which was like three times a week for 20 or 30 minutes. Then a lot of our communities got agreements from the school boards that we could teach our languages instead of French in elementary school. But of course, like anybody who's taken French that way does not become a French speaker, anybody who takes their Indigenous language that way, also does not become a speaker of their language. It becomes a language appreciation type of activity. You become aware of it, and gain some appreciation for the differences between languages, but you do not become a speaker. Since that time, a number of some communities, not a lot in BC, but a few have moved towards having their own immersion schools modeled somewhat after the French immersion schools here in Canada. And then branching out with other emerging communities around the world who are doing similar things, like the Maoris in New Zealand and the Hawaiians in Hawaii have led the way in promoting immersion now. A lot of us are moving to immersion style teaching in many different ways, whether it's in the elementary school or high school. A big movement that is happening right now is two-year immersion programs for adults, and it's full-on immersion for like 1800 hours over two years. I don't know if it was the American army, or whoever, was recommending how many hours it would take to become a good conversational speaker of a language. So people have been creating programs like this now. A young guy in our Squamish community did that. Last year was the first year, and the students came out with the ability to have spontaneous conversations in the language about things that they'd never talked about before.

MEGAN: That’s awesome.

CARRIE: That’s awesome.

PETER: So that's happening in many places, and of course you want people to get even further. But the fact that we can get that far in a year says it's not hopeless or impossible, it just requires a dedication and the space and the money to do it. So there's a second cohort going through this year, and I just saw them the other week. I saw them at the very beginning, and they were all a little bit scared, and then see them few weeks later are able to have some little conversations about stuff in Squamish. They're not doing reading and writing, so it's not a literacy-based approach, mostly. So that's the kind of overview. Now we're actually finding that the adults are really the important people right now in our communities, because they're the ones that are doing all the programming, they’re the ones that are teaching, the ones developing resources - and including and putting myself in this group, we are all additional language learners of our own Indigenous language. For me, Squamish is like my fourth language that I've spent time learning. It's not even my second one. So we feel very positive about the possibilities now. We struggled so long trying to do things in the school system, and there's still a good place for that, but we have to be realistic about how much language our youth are going to get out of an in-school program like that.

CARRIE: Right. And also once there are lots of adults speaking, it makes it easier for children to speak it too, because there are more people for them to talk to. It's awesome.

MEGAN: Are there people that are teaching their kids, as the kids are babies and growing up? Is that happening at all?

PETER: There's not a lot of it yet. I was in a program called Mentor-Apprentice, where I was the mentor of the speaker, and then there was a younger adult, and he was the apprentice. So we spent a lot of time, like hundreds of hours just speaking Squamish, and doing different activities, kind of unstructured. But his son would join us often, especially at the very beginning. He would just sit - he was not even 2 yet. So he's talking with his son and when his son sees me, he'll make sure to say something in Squamish. The research though on bilingual families is kids need to have one other family where the parents and kids are using the language in order for the kids to spontaneously use it without being prompted, eh. So that's the next step - got to find another family to do that with. The kids will naturally just speak. One of our students when I was out teaching at UVic, him and his wife - I don't know they hired or they worked with another young adult - and they became conversational speakers of Mohawk. And then they had kids and they made an agreement to only speak Mohawk to their kids, and so their kids only speak Mohawk at home. They're the first first-language speakers of Mohawk in that particular community, who lost all their speakers in the last 20 years or so. So that's pretty exciting. And the kids, they're very strict, eh. They catch the parents slipping into English and they'll say this in Mohawk, “that language doesn't belong in this home! Speak Mohawk!”

MEGAN: Oh I love it!

CARRIE: That’s so great.

MEGAN: That makes me happy.

PETER: We wonder what they're thinking, but they're thinking that it's theirs, right, which it is.

MEGAN: That’s great.

CARRIE: Yes, it is.

PETER: Their language. That's their identity.

CARRIE: Yeah. When I did some fieldwork in Labrador, there was a girl who - I'm sure she did speak English but she didn't speak English in front of me, she only spoke Innu-aimun in front of me, which was just awesome. I loved it. It gave me hope.

PETER: There's a real hunger in our communities for - I often get asked by people who don't know anything about what's going on, “how do you get your youth involved?” I don't think the question is how do we get them involved, because they're really hungry to know more about themselves, their history, and their language. It's fine being able to create opportunities for them where they can do that. There's no way to do 1800 hours of language learning, unless someone's paying for that, for them to go through and have that experience, with the hopes that will contribute to whatever else is coming in the future. A lot of us are working with institutions, like universities and colleges, to create these type of programs that we can do double purpose. They'll get credits for it, but they also get the experience of becoming conversational speakers.

CARRIE: Hey, Trudeau: hint.

PETER: Yes.

MEGAN: Exactly. Would you say that there's a really supportive environment surrounding learning the Indigenous language as an adult?

PETER: In Canada, or in my community?

MEGAN: I guess in your community. Do you see it being very supportive.

PETER: I was talking about all of this schooling, this three times a week for 20 or 30 minutes, and how it didn't create speakers. But something we really know it did do, is it changed the language attitudes of the community to be a very positive language attitude, because there was a lot of reluctance by the community 40 years ago, because they were worried that the kids would be discriminated against, like they were in residential school. So people were ambivalent about it. People are not ambivalent now. It's really hard to find an ambivalent person in the community about “should we revive our language?” or “we should do it now”. Our problem is we are doing as much as we can, but we're just a little group of people still. We're starting to blossom a bit more and have a lot more different avenues for language learning and jobs, even, for people in the community.

MEGAN: It's great. Do you think outsiders and community members have different perspectives on revitalization? I’m thinking outsiders like linguists that come in, or anyone else that would come in to help with these efforts?

PETER: Keep the outsiders out!

MEGAN: Using the word “outsiders”, making it kind of biased.

PETER: Obviously. I mean I have known Carrie for 20 years, and we call upon her regularly for things that we can, and so we greatly value the support we've got for many people in different institutions. That's one part. Also we have done different types of projects with museums in the city, as a way of promoting knowledge about who we are, but it also is a way to develop language curriculum. You'd be surprised by how many people in Vancouver have no idea - until recently - that there was First Nations that lived in the Vancouver area, and where we lived. Which just seems astounding to me that you could go to a country and not know who the Indigenous people are of that area. It’s not like that [anymore]; the Olympics really changed that. A lot of people know now there's the Tsleil-Waututh and the Xwməθkwəy’əm and the Skwxwú7mesh, the three First Nations in this area. But it didn't used to be like that.

CARRIE: That's true. I think the question was more like outsiders like me have particular ideas about what needs to be done - although I've always been more careful about pushing anything on people, because I think that's bad. I think the perception is that outsiders often have an idea about how to revitalize language and Indigenous peoples have different ideas, which I think it's true.

PETER: Sure. And of course anybody that's not part of a community doesn't know how the community works. And that goes for any community, any small community, and so forth. No one understands how people do things, and you don't know who all the people are, and how the dynamics of the community work. We could never know that. Even when we're in the community, it doesn't mean we really know all those things all the time either. Like how to make decisions, how to convince people to do stuff. You have to really rely on the community to get that done. Say we're gonna do a new project. When we did the dictionary - this is an example of - we did a print dictionary and we published it through the University of Washington Press. We worked with a number of people in our community and outside on that project. But in the community we made sure to include as many different families and people as we could in the making of the dictionary. So when it came out, and we had a community celebration, people are like, “that's my grandmother's dictionary” or “that's my uncle's dictionary”. It wasn't mine and it certainly wasn't Carrie’s. All of us who are doing all the background work, it didn't come out as ours. We knew that as a community how to do that. I think it would be really hard as a person outside the community, and even another Indigenous person, to know how it runs in Squamish. You just have to rely upon the people inside. One of my colleagues Lorna Williams, she's really good at talking about this. She's Lil’wat, which is a neighboring language to Squamish. When she talks to the Canadian public in general, she said this is this is the heritage of all Canadians. These languages are the heritage of everybody, and it'll make Canada a stronger and greater place to be, if these languages are respected and promoted and they thrive. There will be benefits to everybody. She says it much better, but anyway, she's a real big advocate of drawing in everybody that's willing to help.

CARRIE: Yeah, I think that's really important. What was the other thing you want to talk about? Oh: prejudice.

MEGAN: Yes, please.

CARRIE: This is a really difficult - where do you even start.