#battle of saint-mihiel

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

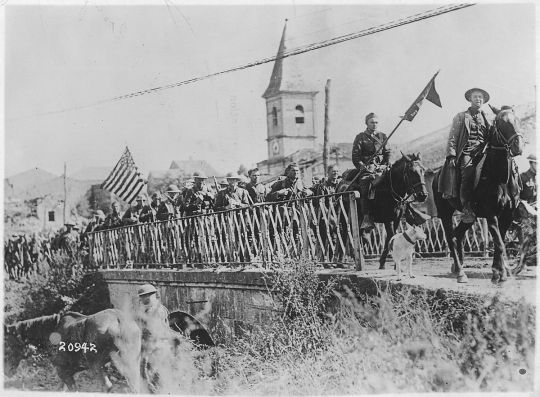

WWI. France. September 1918. US Army troops with a German machine gun captured during the Battle of Saint-Mihiel

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Philosopher's Flight and The Philosopher's War Timeline

Tom Miller clearly planned these two novels stupendously, and I found myself wanting to put everything together in order so I could follow the timeline the way he intended. Hope someone else finds this helpful!

1750: Sigilry comes into widespread use 1831: Cadwallader invents smoke carving 1857: Transporter sigil first comes into use 1861: Wainwright starts Legion of Confederate Smokecarvers April 6, 1865: Petersburg massacre 1865: Birth-control sigils are published 1870: Franco-Prussion war begins 1871: Cadwallader’s Siggilrists break the Korps des Philosoph beseiging Paris 1891: Chilean Civil War - Beau Canderelli is a military philosopher 1892: Maxewell Gannet alludes to his list of 200 sigilrists 1897: Beau Canderelli and Emmaline Weekes meet in Havana January 1899: Robert is born 1901: Second Disturbance - Emmaline Weekes and Beau Canderelli guerrilla fight the trenchers November 1901: Beau Canderelli dies of a gunshot 1902: Hatcher and Jimenez make the first Transatlantic Flight hovering back-to-back 1914: The Great War breaks out February 1916: Gallipoli; Danielle Hardin evacuates most of the Commonwealth army solo 1916: Corruption discovered in 1st Division of R&E by Blandings; Gen. Rhodes creates 5th division for Blandings before Rhodes is fired April 6, 1917: Philosopher’s Flight begins August 1917: Edith Rubinsky (Edie or Ruby) gets her legs ruined January 1918: Robert gets his sigil fixed January 1918: Robert places 3rd in the Long Course of the General’s Cup May? 1918: Danielle becomes aide to Sen. Cadawaller-Fulton July 1918: Robert goes to Europe as part of R&E Early October 1918: Drale dies, Punnet dies in Battle of Saint-Mihiel Late October 1918: Robert breaks 1000 evacuations October 30th, 1918: the mutiny begins; Germans attack Metz and head towards Paris with their plague smoke October 31st, 1918: Robert picks up Bertie Synge and gets trapped under German cloud of smoke November 1st, 2pm, 1918: Edie finds Robert and Bertie November 2nd, 1918: Robert and co. end the war by transporting Berlin January? 1919: Robert ties 1st with Dmitri in the endurance flight February? 1919: General Pershing decimates the Corps, renames it the Army Philosophical Service; Essie stays on and rises through the ranks March 1919: Thomasina Blandings is court-martialed, subsequently gets sentenced to 10 years imprisonment at Ft Leavenworth Christmas 1919: First Zoning law passed January? 1920: Robert ties 1st with Michael Nakamura March? 1920: limits on hoverers license passed; Robert is living in Massachusetts January? 1921: Robert places 1st in Endurance flight 1922: Assuming she held to her timeline, Danielle Hardin runs and wins the Representative seat in Rhode Island 1926: Second Zoning Act - Danielle Hardin campaigns against December 26, 2926: Danielle Hardin writes to Robert 1930: Robert and (presumably) Edie’s daughter is born January 1932: Pilar Desoto orbits earth, Robert powers her 3rd-stage booster 1939: Preface to Flight, Robert is exiled in Mexico and is Field Commander for the Free North American Cavalry (at some point lbefore this, Freddy Unger starts teaching at the Universidad de Tamaulipas, Essie is promoted to Major General of the US Army Philosophical Service, Edie becomes a doctor of Neurology at Matamoros General Hospital) 1941: Danielle Hardin is/was Secretary of Philosophy to Franklin D Roosevelt November 11, 1941: Preface to War, Robert is promoted to Commander and Brig. General of First North American Volunteer Air Cavalry, and is in China due to personal request from Roosevelt (in exchange for amnesty for sigilrists in exile from United Stages)

#the philosopher's flight#the philosopher's war#tom miller#timeline#alternate history#sigilry#books#books you should read#my writing

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spooky Movie Marathon 2024: Week 5

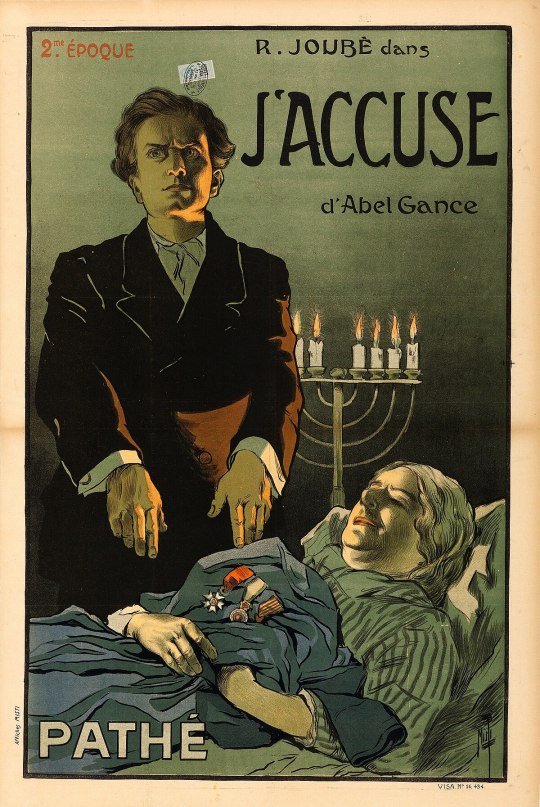

Day 27: J'accuse ! (1919) - French version; unknown restoration info

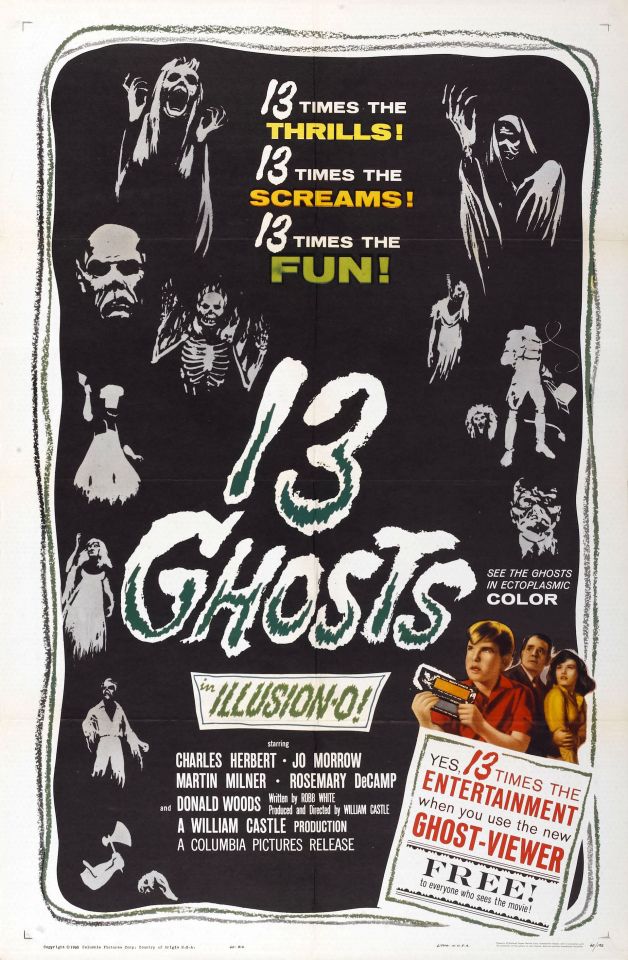

Day 28: 13 Ghosts (1960) - 2D version :(

Day 29: Un monstre à Paris (2011) - English dub; loosely inspired by Le Fantôme de l'Opéra by Gaston Leroux

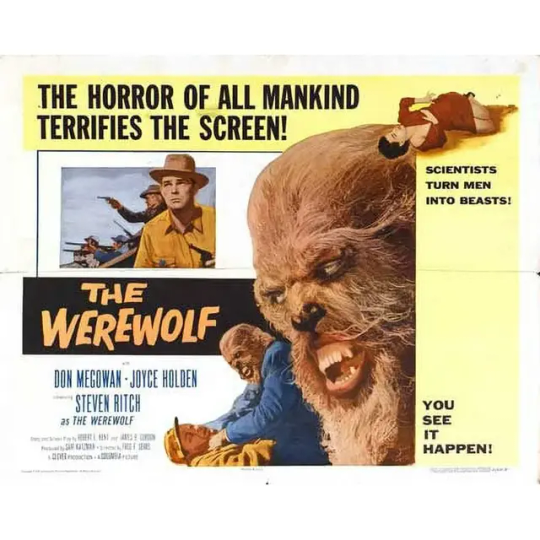

Day 30: The Werewolf (1956)

Day 31: The Tingler (1959)

BONUS! KIND OF! Day 32: Coraline (2009)

closing thoughts:

J'accuse ! (1919) - it is... so long... and because it's a silent epic i can't even work on something else while i watch because i need to pay attention to the intertitles so i know what the heck's happening. aghGHGh. but okay. it is an interesting film! there's early use of a moving camera, quick cuts, and montage editing, which is all really neat in a film history way. there was also a lot of location shooting, including in real ww1 battlefields and of the battle of saint-mihiel, which is both extremely impressive and extremely unsettling in a "how much of this is an unintentional snuff film" kind of way. and in terms of its unsettling aspect, it's far more of a romantic war drama than a horror film, but there's certainly horrific elements. i'd classify it in the vein of social horror akin to freaks (1932), where it's primarily a human interest social drama but when the characters are not permitted to pursue their own needs and desires due to larger societal issues, horror elements are drawn on toward the end to leave a final lasting terror in the audience for their own complicity in those issues. (let's call this "horrific social drama.") in freaks the larger issues are ableism and the eugenics movement, in j'accuse it's the devastating impact of ww1. this is scattered throughout in the film's hilarious repeated shot of the grim reaper and his dancing skeleton minions, then culminates in a proto-modern!zombie "return of the dead" sequence at the end. idk, i don't love it as entertainment since it's not really my thing, but it's interesting. also, random note, but i like how they handled françois's character... he was a scumbag abusive husband but got decent character development and felt like a fully-dimensional person. still a scumbag, but a well-realized one.

13 Ghosts (1960) - oh shit, new fave movie dropped. this movie is so fun!!!!! genuinely creepy but also with a goofy 3D gimmick that combined doesn't always work, but is presented with such classic william castle ballyhoo that i can't help but be charmed. i should be irked by the completely ridiculous ending where the (blissfully not annoying) kid watches a man who was about to kill him gets freaking MURDERED and is clearly traumatized by it and then the next day is just like "wow :) this house is great! i hope we never leave!!! :D," but i am too busy adding "watch this in the original illusion-o vision" to my cinematic bucket list.

Un monstre à Paris (2011) - felt kind of lousy and decided to go for something light. got exactly what i needed <3 this movie is really cute! the human characters are all either kind of boring or not very original, but francœur the monster has all of my heart, which combined is pretty standard for monster movies so i am okay with this. the music was also really good, and as poto-related media goes, i really love that the voice they picked for francœur is a very high, soft voice. not only does it make me feel great about MY voice, but if i remember the book correctly that's the voice erik has (or at least how i interpreted it) instead of the deeper "sexy" voice he tends to get given in adaptations. i've only ever seen/heard one erik with that kind of higher and gentler voice before, peter straker in the ken hill musical, so this was really exciting for me and i loved it a lot. that said, this movie SHOULD have been a 2D animated film oh my god. the concept art and storyboards they had in the end credits were SO gorgeous and i think would have really made the film pop much more than the pretty standard and unappealing 3D animation we got.

The Werewolf (1956): puts my grubby gay fingers all over the celluloid. this movie is a metaphor for being gay in the 1950s! you've got this average family man doomed by an encounter with two mad scientists who work and live together in a tooooootallllllyyyyy heterosexual way who then infect him with evil gay werewolf disease (that is related to nuclear stuff because it's the 50s and everything needs to be about nuclear stuff). he forgets his hetero identity and the wife and son he has waiting for him at home, promptly goes into a bar where a man asks him to buy him a drink and then attempts to rob him, leading to them lying on top of each other in an alley while a little old lady gawks and screams at the horrible sight of their entangled man legs. then mr. average family man kills the evil propositioning man and goes and kills more men, turning into an evil gay werewolf by his emotional reactions to them. he doesn't want his wife and son to see the monster he has become and avoids them, seeking solitude so he won't shame them and be tempted to murder by the sexy murderificness of men. and then of course in the end he dies by mob violence, forever doomed to never return to the non-lycanthropic heteronormative life he once knew. A+++++

The Tingler (1959) - my favorite vincent price and william castle movie ever... an underrated masterpiece of meta horror. i've seen this movie before, and ugh! everything about it is perfect to me. if ever anyone wants to understand me better they should watch this because it's got everything: vincent price, a goofy concept played completely straight, meta filmmaking, a really amazing partialized colorized sequence... this is a movie i need to see in a theater SO BAD, but only so long as the percepto gimmick is in place for peak experience.

Coraline (2009) - this was unplanned but we needed to endurance test a room over an extended period of time at work, and the best way to do that is by watching a movie, and this is what got picked! i had to step out to run and errand in the middle of it, so i didn't technically see all of it, but that's okay, i've seen it before. definitely need to see this one in theaters someday when i get the chance--just watching it on a large projector screen with all the lights off and blinds closed was great, the colors and stop motion really really really POP and are so gorgeous and UGH. i love it. this movie shows in theaters every year in the area where i live, but never at good times so i constantly miss it and then am all >:( because everyone i know keeps getting the chance to see it instead of me. someday, though! someday...

okay. phew. this was fun. i don't normally put this much thought and attention into all the things i watch, or watch movies back to back like this, and for good reason because it. is. exhausting. fun, but EXHAUSTING.

no more! i return now to my vegetative tv viewer state... at least until i do my pride movie marathon in june. but that's another story <3

concluding rankings, ratings, and lists (bonus extra sorting into needless categories for my personal amusement):

top tier masterpieces, faves or new faves

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) (duh)

Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962)

The Tingler (1959)

Planet Terror (2007) was good! will definitely watch again

The VelociPastor (2018)

The House on Haunted Hill (1959)

13 Ghosts (1960)

The House on Haunted Hill (1999)

Coraline (2009)

The Black Cat (1934)

The Skeleton Key (2005)

The Curse of King Tut's Tomb (1980)*

Son of Dracula (1943)* glad i saw it, might not watch it again (at least for a while)

Un monstre à Paris (2011)

Witchcraft (1964)

The Werewolf (1956)

Der Golem, wie er in die Welt kam (1920)

The Comedy of Terrors (1963)

Willy's Wonderland (2021)*

Lyle (2015)*

Return to House on Haunted Hill (2007)*

J'accuse ! (1919)* could have been better except for one thing...

I Know What You Did Last Summer (1997)

White Settlers (2014)

The Mummy (1959)

Bijo to Ekitai-ningen (1958)

Prometheus (2012) eugh

The Creature with the Atom Brain (1955)

XX (2017)

Mary Reilly (1996)

Death Proof (2007)

Encounter with the Unknown (1972)

#screaming into the void#spooky movie marathon 2024#my reviews#anyway now to go watch literally anything other than a horror movie. bye!

1 note

·

View note

Quote

No tank is to be surrendered or abandoned to the enemy. If you are left alone in the midst of the enemy keep shooting. If your gun is disabled use your pistols and squash the enemy with your tracks… If your motor is stalled and your gun broken still the infantry cannot hurt you. You hang on [and] help will come. In any case remember you are the first American tanks. You must establish the fact that American tanks do not surrender! As long as one tank is able to move it must go forward. Its presence will save the lives of hundreds of infantry and kill many Germans. Finally, this is our big chance. Make it worthwhile.

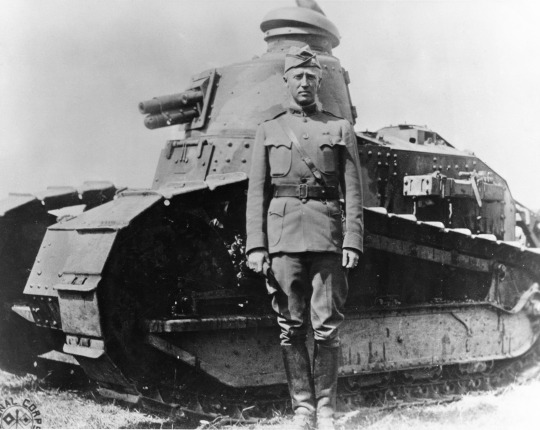

Lt. Colonel George Patton, commanding officer of the American Expeditionary Force’s 1st Tank Brigade, addressing his men before the Battle of Saint-Mihiel.

Lt. Col. Patton in front of one of his battalion’s French Renault FT light tanks, c. summer 1918 (source)

Saint-Mihiel marked the first time the AEF’s Tank Corps had seen action and while many tanks were bogged down in recently rain sodden French soil they proved themselves a valuable fighting force that went on to see further success during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive several weeks later.

Patton gained a reputation for leading from the front, often walking to the frontline and directing his tanks personally. This leadership style would see him wounded in the thigh during the last weeks of the war. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and the Distinguished Service Medal.

Source:

Quoted in Patton: A Biography, A. Axelrod, (2009)

If you enjoy the content please consider supporting Historical Firearms through Patreon!

#History#Military History#Quote#Quote of the Day#History Quotes#George Patton#Patton#George S Patton#WWI#WWI100#World War One#Tanks#Armoured Warfare#american expeditionary force#US Tank Corps#General George S Patton#Meuse-Argonne Offensive#Battle of Saint-Mihiel#Renault FT#Tank#QOTD#Quotes

350 notes

·

View notes

Text

World War I (Part 73): The End of the War

It was obvious that Germany was going to lose the war in the west, but Ludendorff was incapable of seeing sense. He still believed that Germany could end the war in possession of part of Belgium, and France's Longwy-Briey Basin. On August 28th, Foch said, “The man could escape even now if he would make up his mind to leave behind his baggage.”

Britain was preparing for an offensive out of Arras. Foch was demanding that America contribute divisions to it, but Pershing refused – he wanted to concentrate his troops on his own sector of front, to achieve his own objectives. Foch was indignant at this.

Pétain worked out a solution, providing French support for the offensive that Pershing was preparing at St. Mihiel. This offensive had three goals – 1) drive the Germans out of the salient; 2) cut the railway line that ran laterally behind the salient; 3) threaten Longwy-Briey. It was to begin in five days' time – the Allies were in a rush, thinking for the first time that they might be able to finish the war before winter.

The Arras offensive (with Canadians in the lead) was successful, breaking through everywhere they attacked. Ludendorff was forced to order a pullback to the Hindenburg Line, giving up all they'd gained in 1918. But it was too late for an orderly retreat – during the fortnight-long withdrawal, the Germans lost 115,000 men, 470 guns, and stores that they had no way of replacing. And that was just on the British part of the front.

After four years of fighting, the Anzac & Canadian corps were so potent that Haig repeatedly used them as a battering ram to smash the German line with, and it was the case here as well. It was likely that they were the best divisions in the whole war (on either side). John Monash and Lieutenant-General Sir Arthur Currie, his Canadian counterpart, were much of the reason for this.

Like Monash, Currie's background set him apart from almost all the other BEF generals. He'd grown up on a farm in British Columbia; he wanted to be a lawyer, but after his father's death he became a teacher. After that he went into insurance, and then into real-estate speculation.

At 21yrs old, he joined the Canadian Garrison Artillery (a “weekened-warrior operation” [?]) as a gunner. He was competent and amiable, and was commissioned at 25yrs old, promoted to Captain the next year, and at 33yrs old he became a Lieutenant-Colonel, commanding a regiment.

Medical problems kept him out of the Boer War, to his disappointment, and he was eager to fight when WW1 broke out. He was as well-qualified as a Canadian soldier could be at that time, and was put in command of one of the country's four brigades.

But he was struggling financially. Early in 1914 a real estate bubble had burst, leaving him in major debt. He borrowed regimental funds to avoid bankruptcy, and if it wasn't for the intervention of friends he might have been charged with embezzlement.

However, by the end of the war he had become one of the BEF's most respected commanders. In April 1915, during the Second Battle of Ypres, his brigade held off a German attack on the village of St. Julien, preventing the battle from turning into a disaster for the British. In 1916, his Canadian First Division showed its brilliance in capturing Vimy Ridge; this led General Henry Horne to declare it “the pride and wonder of the British army.”

In June 1917, the British selected Currie to become the first Canadian commander of the Canadian Corps. But back at home, people weren't happy – politicians complained that they'd hadn't been consulted, and proposed other candidates; they also urged Currie's creditors to demand payment in full. So Currie's promotion was changed to “temporary”, and seemed likely to be revoked. Even compared to Monash he was a fish out of water among the other generals – his son would later recall, “He had a tremendous command of profanity. He didn't swear without a cause. But boy, when he cut loose he could go for about a minute without repetition.”

Two of Currie's officers advanced him $6,000, and the great respect the Canadian troops had for him made it clear that removing him would spark protests. He was also knighted. At the end of August 1918, his troops had a record of never once failing to capture an objective, never being driven out of a position that they'd had the opportunity to consolidate, and never losing a gun.

At the beginning of September, the biggest problem for the Germans was the huge mass of American troops assembling near Verdun. Ludendorff knew they were going to attack, so he ordered the entire salient (518 square km, 21km deep) to be abandoned.

Pershing had originally planned for the offensive to begin on September 7th, but he was held up by difficulties in getting French artillery into position. He wanted to destroy the defenders as well as capture the salient, and he certainly had the resources to do so – a million American troops, 110,000 French troops, 3,000 artillery pieces, complete air superiority, and essentially unlimited ammunition.

The Battle of Saint-Mihiel began on September 12th with a 4hr-long barrage. When the infantry advanced, though, they found only a rear guard shielding the escape of eight German divisions. The Americans took the salient within a day, taking 15,000 prisoners and 450 guns.

Pershing and his staff immediately began preparing for another attack, this one in an area that was bordered by the Meuse's heights and the Argonne Forest, where the Germans were waiting with a 19km-deep defensive system nearly as formidable as the Hindenburg Line. But Pershing had 820,000 troops (600,000 of them being Americans), 4,000 guns, and enough shells for the guns to fire at their maximum rate until the barrels burned out. The staff had two weeks to get everything ready.

Everywhere else, things were falling apart for the Central Powers. Franchet d'Esperey's Army of the Orient were weakened by malaria and influenza, and when they attacked the strong Bulgarian & German entrenchments outside Salonika, the defenders held their ground for several days, making it seem that this attempt to break out of Salonika would end in failure as usual. But the Bulgarians were struggling with ammo & supply shortages, and their morale was low; they attempted a limited retreat that was intended to draw the Entente forces into an ambush.

It didn't work. D'Esperey's aircraft began to attack almost as soon as the Bulgarians were out of their defences, and the retreat turned into a rout. The Bulgarian troops were exhausted, and tired of a war that had accomplished nothing; they were unhappy with their king, who had made the decision to join the Central Powers. Now they abandoned the fight, leaving the way the Hungary's interior open to the Entente advance units.

German troops were sent to salvage the situation, but it wasn't possible. Later, Ludendorff would say of the situation, “We could not answer every single cry for help. We had to insist that Bulgaria must do something for herself, for otherwise we, too, were lost.”

Bulgaria asked for an armistice on September 25th, and it was granted five days later. The Turks had been defeated in Palestine by an Allied force commanded by the British General Edmund Allenby; they were in retreat towards Damascus (Syria), and couldn't do anything about Bulgaria unless they left Constantinople unprotected. The war in the Balkans was over.

Ludendorf & Hindenburg met in their headquarters on September 28th. They abandoned their illusions, and admitted that the Balkans were lost, and so was the war in general. A few days later, Hindenburg would write that they were forced to do so largely “as a result of the collapse of our Macedonian front,” and their consequent exposure to attack from the east.

Ludendorff had no options left, and he sent his army group commanders a message, stating that there would be no more withdrawals in the west. He was still determined that every position be held, and told his staff that “pneumonic plague” had broken out in the French army – he'd heard a rumour about it, and “clung to that news like a drowning man to a straw,” as he later put it. The rumour was nonsense.

At the Hindenburg Line, Britain & France were attacking, capturing thousands of Germans and hundreds of guns. In the Meuse-Argonne, the French were attacking on a 64km-wide front. Even the Entente armies were taking huge casualties – from August 28th to September 26th the British had 108,000 casualties; the Americans had 26,000 killed and 95,000 wounded in about the same period. But this was more bearable than earlier in the war, because the Allies had the hope that an end was in sight, and the Germans couldn't possibly stand up to all of this without eventually collapsing.

A British sergeant wrote home, “I have seen prisoners coming from the Battle of the Somme, Mons and Messines and along the road to Menin. Then they had an expression of hard defiance on their faces; their eyes were saying: 'You've had the better of me; but there are many others like me still to carry on the fight, and in the end we shall crush you.' Now their soldiers are no more than a pitiful crowd. Exhaustion of the spirit which always accompanies exhaustion of the body. They are marked with the sign of the defeated.'

The best of the remaining German units, continued to resist with intense determination – but it was quite obviously a lost cause. The Allies had 6 million troops in the west, but they didn't actually need to use all of them, thanks to their artillery & tank advantage, and the fact that Monash's tactics were now widely adopted. Nearly 40% of the French army (over a million men) were assigned to artillery. While they'd had only 300 medium & heavy guns in 1914, they now had nearly 6,000.

On September 28th & 29th, the Canadians finally broke through the Hindenburg Line. This was thanks in part to their firing of nearly 944,000 artillery rounds during those two days. In early October, 12,000 tonnes of munitions were being fired every 24hrs. France's 75mm light field guns were firing 280,000 rounds a day. The Germans on & near the front were living under a constant barrage.

The Allies were regularly breaking through the German line, and with increasing regularity – on October 5th, each of Haig's four armies did so at one or more points. But none of these successes turned into a rout. The hard core of the German army was low on food & ammo, and never able to get a day's rest, but they gave up ground reluctantly and continued to take a heavy toll on the enemy; they even managed to counterattack at critical junctures. In some places, the German line was manned only by officers with machine-guns. And still the line didn't dissolve. The number of Allied troops killed in combat was higher than the Germans.

An American Marine battalion that eventually succeeded in driving the Germans off a hill in Champagne lost almost 90% of its men (killed/wounded). This region had been reduced to “blackened, branchless stumps, upthrust through the churned earth...naked, leprous chalk...a wilderness of craters, large and small, wherein no yard of earth lay untouched.”

Heavy autumn rains, the difficulty of the terrain, and the strength of the remaining German infrastructure (especially along the eastern sector, where the Americans were) slowed the Allied advance. The size of the Allied force, while an advantage in attacking, was a disadvantage in other ways – it was extremely difficult to keep it supplied and in motion, and to deploy the guns & men. In fact, Pershing was forced to suspend his offensive in the Argonne for a week in order to get things sorted out.

Admiral Paul von Hintze had been appointed Foreign Minister on July 6th, after Kühlmann's forced resignation. In the aftermath of Salonika, he met with Ludendorff, who outlined the realities of the situation, as he'd done with Hindenburg. He told him that they needed an armistice immediately. This was sensible, but he also said that he thought a ceasefire could be secured within a few days; and he wanted an agreement that would allow their armies to pull back to the German border, rest the troops and build their defences, and later resume the fight if they chose to do so! Hintze was shocked at this, and the conversation became so heated that at one point, Ludendorff collapsed to the floor in one of his rages.

They did agree, however, to approach Woodrow Wilson about an armistice based on his Fourteen Points. Hintze's goal was to save Germany and the Hohenzollern dynasty, and he suggested that they carry out a “revolution from above”: to transform Germany's political system in a way that would demonstrate that Germany was now under progressive (even democratic) leadership, and that this change had been accomplished by the kaiser (rather than in spite of him).

The “revolution” wasn't really that, though – the most radical change was giving Reichstag representatives a place in the cabinet. Because it wasn't much of a change, it was possible for Ludendorff and the kaiser to agree to it – but the conservatives considered it a shocking violation of Prussian & Hohenzollern tradition. Chancellor Hertling, who wasn't even a Prussian, resigned the chancellorship rather than agree to it.

On September 27th, the kaiser signed a proclamation of parliamentary government, in an attempt to salvage something of his inheritance. One officer noted that he was a “broken and suddenly aged man.” Wilhelm knew that all of his ancestors (except for his father) would be horrified at his actions, but the German leaders knew that the situation was desperate.

(This change, in the end, led to the liberals & socialists in the Reichstag having to take part of the blame for the disaster that was unfolding.)

Hintze insisted that he also had to resign, to demonstrate that the kaiser's proclamation wasn't just empty words; the kaiser & Ludendorff failed to dissuade him.

On September 30th, Ludendorff sent a member of his staff (only a Major) to Berlin, with orders to inform the Reichstag of what was happening on the Western Front. But the truth contradicted so much of what the public & the Reichstag deputies had been led to believe, causing great damage to the government & military's credibility.

On October 3rd, Prince Max of Baden became the new Chancellor, and was given the job or arranging a peace. Max was “the one prominent royalist liberal in the empire,” and was capable, but in poor health. He was well-known within the German establishment for reformist sympathies, so his appointment would hopefully show the Allies that there was a new kind of government in Berlin; one that the democracies could come to terms with.

But things looked quite different to the Allies – Max was a relative of the kaiser, and a member of the Baden royal house. He seemed simply more of the same.

On the 3rd, Max signed a note that Hintze had drafted, addressed to Woodrow Wilson. It asked for an immediate armistice, and accepted the peace terms that Wilson's government had been issuing during that year.

Wilson replied promptly, and in almost friendly terms. He asked the Germans to confirm their acceptance of the Fourteen Points, and their willingness to withdraw from all occupied territory. The prince's government signalled their agreement.

It was by now the second week of October, and the Allied armies were briefly stymied on the Western Front. The Americans were finally clearing the Argonne (with Brigadier General Douglas MacArthur constantly exposing himself to enemy fire), but they had taken high casualties, and were facing even stronger defences further east.

Ludendorff, moving away from the sensible attitude he'd been showing, began to talk of line-shortening measures that could enable them to hold out through the coming winter, and wear the Allies down through attrition, in order to get better peace terms.

But this was not likely to happen – even the peace terms that they were hoping to get already weren't going to happen. Wilson was under pressure: after a year and a half of propaganda, the public had become almost hysterically anti-German. Congress members responded in ways that would increase their own popularity. The president had been severely criticized for not responding strictly enough to Germany's request. The midterm elections were scheduled for November 5th, and his party had only a thin majority over the Republicans in both Congress houses. The French and British, too, were pushing him to take a harder line.

On October 10th, the steamer RMS Leinster was sailing between Ireland and England's west coast, as usual. Not long before 10am, a U-boat fired two torpedoes into her hull, and she went down with nearly 450 people killed, including 135 women & children. One of those killed was Josephine Carr, a 19yr-old shorthand typist from Cork, the first member of the WRENS (Women's Royal Naval Service) to be killed on active service.

The result of this sinking was that all the Allies toughened their peace terms, including Wilson, who sent a new note to Berlin, in an entirely new tone. He demanded an end to the submarine warfare, and referred to the “arbitrary” power of Germany's military elite and the threat it posed to the world – and any armistice terms must be settled with the Allied commanders in the field, rather than with him or even the Allied governments acting together. This got him off the hook.

Hungary had declared itself an autonomous nation, separating itself from the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Emperor Karl, desperate to try and save something from the wreckage, issued a manifesto that transformed the remains of the empire into a federation in which all members would have their own national councils (even nationalities as obscure as the Ruthenians).

But no-one paid any attention to this – all the pieces of the empire were going their own ways, and the remnants of his army were breaking up as well, with various non-Austrian units marching home. Now, the road to Central Europe lay open to the Army of the Orient. This included Romania, which Germany relied upon for oil.

On October 17th, the German Council of War gathered – the kaiser, Ludendorff, Hindenburg, and all the new government's leading officials. Ludendorff was completely irrational, insisting that they would hold out through the winter (actually, that very night he would find out that the British had made a new breakthrough and were advancing again).

He also threatened to resign if the other generals were even allowed to express their opinions, and demanded that the submarine campaign continue. The kaiser agreed, and only Prince Max disagreed. He threatened to resign himself if they didn't accept Wilson's terms to the last detail. It was impossible to let this happen, as they'd attached so much importance to the creation of a “liberal” government. So Ludendorff's power was now broken.

Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria was still commanding the northern German army group. He sent a warning to Prince Max that if they didn't soon get an armistice, they wouldn't be able to prevent their country from being invaded.

General Wilhelm Gröner had begun the war as head of the German railway system, and had held other important positions since then (and had been at odds with Ludendorff along the way). Now, he reported that at least 200,000 troops were missing, many of them having deserted. In fact, it could be as many as 1.5 million, as it was no longer possible to keep track.

During October, 133,000 French troops were killed, wounded or missing. But the Allies were still attacking, and the Germans were struggling more and more. They had no replacements and hardly any reserves; meanwhile, the Allies had so many troops that they were able to pull the Anzac Corps out of the line – they were near breaking point, and Monash couldn't keep his left hand from trembling, so he tended to keep it in his pocket.

On October 22nd, Admiral Franz von Hipper (new chief of the German High Seas Fleet) tried to execute Operation 19, in which his ships were to put to sea and fight the British & Americans in a final suicidal campaign. Three dreadnought crews at Kiel heard of this plan and mutinied, running red banners of revolution up their masts; the Kiel army garrison joined in, and the revolt quickly spread. Now the German fleet wasn't even a potential fighting force.

On October 23rd, Germany received a third note from Wilson: “If the Government of the United States must deal with the military masters and monarchical autocrats of Germany...it must demand not peace negotiations but surrender.”

Provoked by this, Ludendorff wrote a harsh message to the troops, and both he and Hindenburg signed it: “Our enemies merely pay lip service to the idea of a just peace in order to deceive us and break our resistance. For us soldiers Wilson's reply can therefore only constitute a challenge to continue resisting to the limit of our strength.”

Ludendorff then travelled from his headquarters to Berlin, with the intention of ending Prince Max's dialogue with Washington. But he arrived to find that his message had created a furor – the public (who were hungry for peace), a large part of the Reichstag, Prince Max himself, and even the military were indignant. The note had to be withdrawn, because so many of the field commanders had protested. This was yet another humiliation for Ludendorff, and some Reichstag members were demanding he be removed. Some were even saying that if peace was impossible with the kaiser on the throne, then the kaiser must go too.

News of new disasters was arriving every day, almost every hour. In Italy, an Allied force of 56 divisions (including 3 British & 2 French) were attacking northwards – the Italians were trying to seize as much territory as possible before the fighting ended. The Austrians revolted instead of resisting, with 500,000 of them surrendering. Their generals sent a delegation to Trieste to beg for an armistice. (This was the Battle of Vittorio Veneto.)

Now Ludendorff began talking about something he called “soldier's honour”, in which the entire German nation would be mustered for a final fight to the death. The deputy chancellor listened to Ludendorff's rant, and replied, “I am a plain ordinary citizen. All I can see is people who are starving.”

On October 26th, Ludendorff & Hindenburg met privately with the kaiser. Ludendorff coldly offered his resignation, aware that his position was untenable. Wilhelm offered to transfer him to a field command, but Ludendorff refused & asked to be relieved. Hindenburg also asked to be relived, but the kaiser told him curtly, “You will stay,” and Hindenburg bowed in acquiescence. Ludendorff would see Hindenburg's obedience as an unforgivable betrayal for the rest of his life.

When Ludendorff's decision was announced in Berlin's movie houses, audiences cheered. Ludendorff slipped away to Sweden, as it was too dangerous for him to stay in Germany.

On October 27th, Germany sent a fourth note to Wilson, giving in. It stated that Germany “looked forward to proposals for an armistice that would usher in a peace of justice as outlined by the President.” They were now accepting that Wilson would decide the peace terms, but assumed that they would correspond to the Fourteen Points. This would not be the case.

While Germany waited, Americans captured the French city of Sedan, and severed Germany's last north-south railway line in France. Turkey & Austria surrendered, and Bavaria began to explore a separate peace. Revolution broke out in nearly every provincial capital. A republic was declared in Munich, and on November 7th Ludwig III of Bavaria (the last King of Bavaria) & his family fled from the Residenz Palace in Munich, to the Schloss Anif (near Salzburg in Austria). And Crown Prince Rupprecht now no longer had a home to return to.

The commanders-in-chief of the Allied armies met on October 28th to decide on the armistice terms, and there was a lot of disagreement. Haig suggested that Germany should withdraw from Belgium & France, and surrender Alsace-Lorraine. Pétain went further, demanding that German withdraw east of the Rhine (even north of Alsace-Lorraine), and hand over large parts of Germany itself. Pershing's preferred terms were the strictest of all.

Britain & France were now wanting to end the war as soon as possible, before the Americans became so dominant that they were able to dictate the peace terms. These weren't irrational fears – they'd started when Wilson had begun communicating with Germany without even consulting the other Entente nations.

There were major issues dividing the Allies. Lloyd George & Wilson had very different ideas on how things such as post-war trade, freedom of the seas, and the German colonies should be decided. When Wilson's Fourteen Points were introduced into the discussion, the generals had to send out for a copy, because none of them really knew what they covered.

The kaiser was asked to abdicate on November 1st. He refused, and talked about leading the armies back to Germany to put down the revolt, which was spreading. General Gröner had replaced Ludendorff as quartermaster general; he asked the most senior generals on the Western Front if their troops would obey the kaiser & take part in suppressing the population. Gröner was a capable man, and after the war he would save Germany's fledgling democracy twice (and become an enemy of Hitler for doing so); he knew what the answer was likely to be, and he was right. One said yes, 23 said no, and 14 said possibly. Wilhelm was informed of this, and Hindenburg told him that his safety could no longer be assured. The kaiser abdicated, crossing the border into the Netherlands. where Queen Wilhelmina had agreed to accept him.

On November 8th, a German delegation arrived at Allied headquarters in Compiègne. It was headed by Matthias Erzberger, head of the Catholic Centre Party. Germany was facing civil war and was afraid of a Communist takeover, and the government had ordered Erzberger to accept whatever terms were offered.

Foch made it clear that there was to be no discussion of the terms, and then presented the conditions under which the Allies would agree to a 30-day armistice. The terms included Germany's withdrawal to east of the Rhine within a fortnight; their withdrawal to the eastern borders of August 1st, 1914; the repudiation of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk; the surrender of all Germany's colonial possessions in Africa; and the handover of 5,000 artillery piece, 3,000 mortars, 30,000 machine guns, and 2,000 aircraft. Furthermore, the Allied naval blockade would continue. The delegation was given three days to decide whether or not to accept.

Eventually, however, a few minor adjustments were made, as the Allies were also worried about a Communist revolution in Germany. The number of machine guns to be surrendered was reduced, so that the German authorities could better restore order. Erzberger led his fellow delegates in signing the agreement; he would later be assassinated for his “betrayal” of the Fatherland.

The armistice went into effect at 11am on November 11th. Mangin disagreed strongly with the decisions: “We must go right into the heart of Germany. The armistice should be signed there. The Germans will not admit that they are beaten. You do not finish wars like this...It is a fatal error and France will pay for it!”

#book: a world undone#history#military history#ww1#second battle of the somme#battle of saint-mihiel#meuse-argonne offensive#kiel mutiny#battle of vittorio veneto#ww1 armistice

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

An American gun crew fire a French 75mm gun at German positions during the Battle of St Mihiel, France - September 1918

The Battle of Saint-Mihiel was a major WW1 battle involving the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) and 110,000 French troops under the command of General John J Pershing of the US against German positions.

American gunners had to use French artillery as there were no guns of American manufacture in France at that time. It was also the first time the terms H-Hour and D-Day were coined by the American soldiers.

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bulgarian Collapse Begins

Tsar Ferdinand of Bulgaria (1861-1948, r. 1887-1918). He agreed to ask for an armistice on September 25, likely in full knowledge that his days as Tsar were numbered.

September 25 1918, Gradsko--The German and Bulgarian plan for a limited retreat, followed by an attack on both sides to cut off the expanding Allied salient, quickly fell apart in practice. On September 25, the Allies took Gradsko, at the confluence of the Crna and Vardar, splitting the defenders’ armies in two and capturing a major supply dump (though the Germans burned much of it before leaving). The Bulgarians continued to put up a stiff resistance before Veles, further up the Vardar, with a fresh division, but any additional retreat would push them further and further away from Bulgaria proper, which the British entered on the same day (near Kosturino, now in Macedonia). The fall of Gradsko severely alarmed the Austrians and Germans, who finally began to send reinforcements to the area, but they would come far too late.

Meanwhile, as Franchet d’Esperey had ordered, the cavalry was unleashed. On September 25, they reached the Babuna Pass from Prilep (which they had captured without opposition two days earlier, just four days after a major German-Bulgarian military conference there). Its commander, Jouinot-Gambetta, then decided to strike through unforgiving but undefended country straight north towards Skopje, rather than proceeding immediately into the Vardar river valley to assist with the capture of Veles. The rough terrain meant the cavalry had to dismount, but they still advanced 11 miles on the first day.

The Bulgarian Army was falling apart. The country had been at war, on and off, since 1912, and had little appetite to continue the fight. Following the Russian example, Soviets were set up in several locations across the country. Troops began to desert en masse, some commandeering trains to return home, while others marched on Kyustendil, the location of the Bulgarian GHQ, in an attempt to end the war more directly. That night, hoping to avert a revolution, Tsar Ferdinand, under pressure from moderate political leaders, released the agrarian leader Stamboliski (a move he would almost instantly regret) and agreed to let his chief of staff ask for an armistice; his representatives would be received by the British the next morning.

Today in 1917: Lloyd George Visits France Today in 1916: Battle of Morval Today in 1915: Allies Begin General Offensive in Artois and Champagne Today in 1914: Germans Advance Near Saint-Mihiel

Sources include: Alan Palmer, The Gardeners of Salonika.

#wwi#ww1#ww1 history#ww1 centenary#world war 1#world war i#world war one#the first world war#the great war#bulgaria#serbian front#macedonia#cavalry#franchet d'esperey#desperate frankie#september 1918

71 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“We are living like paleozoic monsters, in a world of muck and slime”

“September 11 1918 -- Our headquarters are at Hamonville, not far from Seicheprey where the 26th Division had played a savage game of give and take with the Germans last Spring.The men are encamped in a forest of low trees, a most miserable spot. It has been showering and wet all the week and we are living like paleozoic monsters, in a world of muck and slime. The forest roads are all plowed by the wagon wheels, and the whole place was really a swamp. I made my rounds during the afternoon and got the men together for what I call a silent prayer meeting. I told them how easy it was to set themselves right with God, suggesting an extra prayer for a serene mind and a stout heart in time of danger; and then they stood around me in a rough semicircle, caps in hand and heads bowed, each man saying his prayers in his own way. I find this simple ceremony much more effective than formal preaching.”

Father Duffy, chaplain attached to the Rainbow division, comforting his men before the Battle of Saint Mihiel.

Father Duffy Father Duffy's Story: A Tale of Humor and Heroism, of Life and Death With the Fighting Sixty-Ninth – Photo: 1918, France, Rainbow Division’s trucks in the mud. Missouri Over There

See National Archives Video “THE ST. MIHIEL OFFENSIVE, SEPT. 10-25, 1918”

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

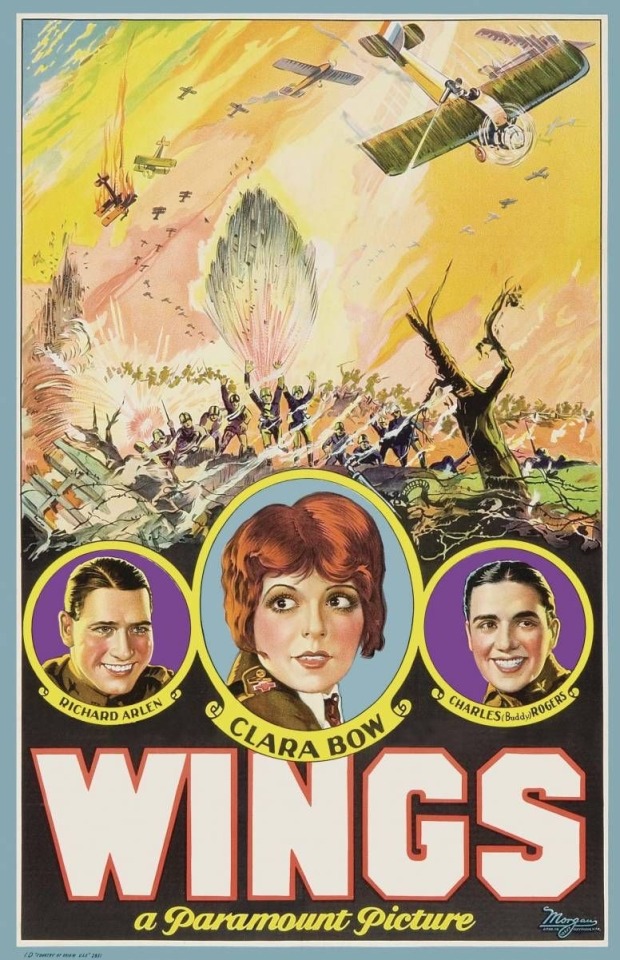

See that vintage film gifs post I just reblogged from @daylelight? One of the gifs, of the two men in uniform kissing, is taken from the 1927 film Wings, and it’s often described as the first gay kiss in cinema. There’s a lot of debate about the intention of the kiss, as you might expect, but it certainly looks pretty intense to me. There’s a good Wikipedia article about the film, which includes this summary of the climactic moment.

The climax of the story comes with the epic Battle of Saint-Mihiel. David is shot down and presumed dead. However, he survives the crash landing, steals a German biplane, and heads for the Allied lines. By a tragic stroke of bad luck, Jack spots the enemy aircraft and, bent on avenging his friend, begins an attack. He is successful in downing the aircraft and lands to retrieve a souvenir of his victory. The owner of the land where David's aircraft crashed urges Jack to come to the dying man's side. He agrees and becomes distraught when he realizes what he has done. David consoles him and before he dies, forgives his comrade.

And here’s the scene in question. Anyone who even whispers the words “Eruri AU” is banned.

youtube

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A group of wounded German Army prisoners receiving medical attention at first aid station of U.S. 103rd and 104th Ambulance Companies. The Battle of Saint Mihiel, 12 September 1918. [900 x 620] Check this blog!

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Renault FT moves out during the September 1918 battle of Saint-Mihiel. This was the first major offensive by the American Expeditionary Force and caught the Germans mid-retreat, with unexpected success as a result.

0 notes

Text

Wings (1927)

Jack Powell and David Armstrong are rivals in the same small American town, both vying for the attentions of pretty Sylvia Lewis. Jack fails to realize that "the girl next door", Mary Preston, is desperately in love with him. The two young men both enlist to become combat pilots in the Air Service. When they leave for training camp, Jack mistakenly believes Sylvia prefers him. She actually prefers David and lets him know about her feelings, but is too kindhearted to turn down Jack's affection.

Jack and David are billeted together. Their tent mate is Cadet White, but their acquaintance is all too brief; White is killed in an air crash the same day. Undaunted, the two men endure a rigorous training period, where they go from being enemies to best friends. Upon graduating, they are shipped off to France to fight the Germans.

Mary joins the war effort by becoming an ambulance driver. She later learns of Jack's reputation as the ace known as "The Shooting Star" and encounters him while on leave in Paris. She finds him, but he is too drunk to recognize her. She puts him to bed, but when two military police barge in while she is innocently changing from a borrowed dress back into her uniform in the same room, she is forced to resign and return to the United States.

The climax of the story comes with the epic Battle of Saint-Mihiel. David is shot down and presumed dead. However, he survives the crash landing, steals a German biplane, and heads for the Allied lines. By a tragic stroke of bad luck, Jack spots the enemy aircraft and, bent on avenging his friend, begins an attack. He is successful in downing the aircraft and lands to retrieve a souvenir of his victory. The owner of the land where David's aircraft crashed urges Jack to come to the dying man's side. He agrees and becomes distraught when he realizes what he has done. David consoles him and before he dies, forgives his comrade.

At the war's end, Jack returns home to a hero's welcome. He visits David's grieving parents to return his friend's effects. During the visit he begs their forgiveness for causing David's death. Mrs. Armstrong says it is not Jack who is responsible for her son's death, but the war. Then, Jack is reunited with Mary and realizes he loves her.

#clara bow#silent stars#silent hollywood#silent era#silent cinema#silent movies#golden age of hollywood#classic hollywood#classic movies

0 notes

Photo

In 1918 my Grandpa Isaac, a native New Mexican who had never left his idyllic corner of northern New Mexico prior to being drafted, found himself fighting in the Battle of Saint-Mihiel as part of the US Expeditionary forces. Spanish was his first language, but he could speak English too, something unique for NM back then. He saw his childhood friend literally get cut in two by a German machine gun. He was gassed during the battle and spent the rest of the war convalescing in a hospital.

Inside command post at a German rest camp inside the Saint-Mihiel salient

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

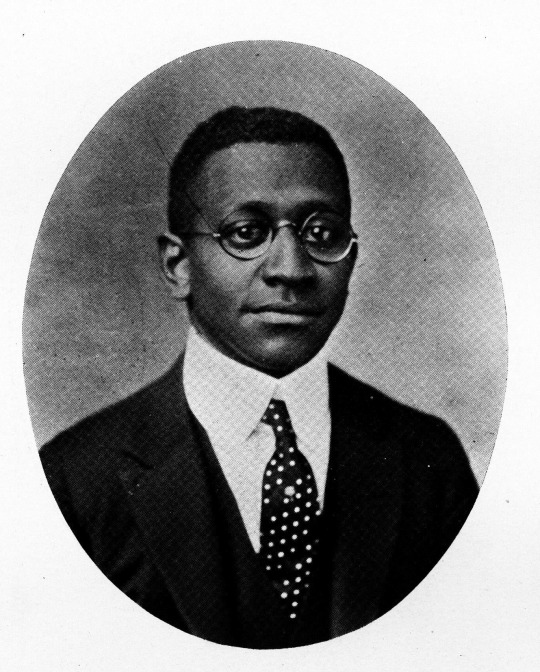

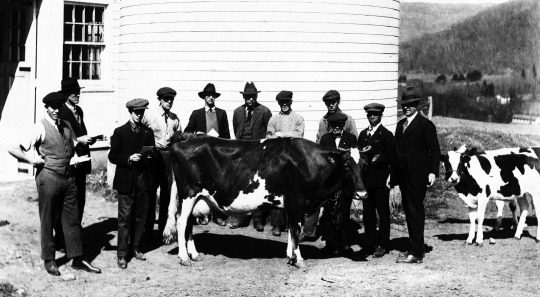

SUNY Delhi’s First African American Graduate

This month, SUNY Delhi dedicates its Multicultural Lounge in memory of its first African American graduate, Thomas Russell Brown. Read what the college’s archivist, Jennifer Collins, learned about this exceptional alum.

Thomas Russell Brown was born in Manhattan, NY, December 7, 1897. His parents, Thomas Senior and Christiana, were freed slaves, both born on plantations in South Carolina. Neither Thomas nor Christiana could read or write, but both worked diligently at odd jobs until they gathered funds to move themselves and Christiana’s family north to New York City. This was during the Southern Diaspora, a time when many recently freed African Americans moved to cities like Philadelphia, Boston and New York City to find better lives and opportunities. The Browns settled in Harlem in a brownstone built by a self-taught African American Architect and started building a life.

Thomas grew up in this now historic section of Harlem surrounded by the budding intellectual and artistic thinkers who would start the Harlem Renaissance. Although we do not know much about Thomas growing up, the information that we can glean from census data and school files is that he was both studious and athletic. By all accounts his parents had the same hopes and drives all parents have when their children are growing up. They wanted their child to receive a full education and to prosper beyond what they were able to achieve. Unlike the vast majority of African American children at the time, Thomas completed high school. This was a rarity, especially in urban areas, where work superseded education for most families.

Defying expectations Thomas completed high school in 1916 and in February of 1917 he went to Long Island to enlist with the U.S. Army to fight in World War I. For most African American men service during the war meant doing laundry, cleaning American bases, and collecting bodies from the battlefield. Military records available from the Pentagon Library indicate that Thomas was placed in Company A of the 310th Division, a Quartermasters Unit that supported the 155th and 78th Infantry.

We need to put that discovery in perspective. The 310th was responsible for delivering critical supplies like petroleum and ammunition into active war zones on the French Front. The 78th is one of the most decorated units in the history of WWI. It was the 78th, supported by Thomas’ unit, that pushed the Germans out of France and won the crucial victory of the Battle of Saint Mihiel (pictured above). Membership in the 310th required exceptional reading and writing skills, analytical thinking and cartography skills. We can conclude that Thomas had these exceptional skills to participate in his unit.

At some point between 1918 and 1919 Thomas suffered a severe injury. We cannot say for sure, but it is likely that Thomas was injured during a supply run. The combination of unsecured live ammunition, large amounts of petroleum, and the nature of trench warfare made for a number of horrific injuries to members of the 310th.

After his injury Thomas was discharged with a disability—one serious enough that he was able to quality for lifetime military disability status. It would have been easy for Thomas to return home and have left it at that. A military veteran with a distinguished career (but one ineligible for any major military aware due to his race). Instead, he did something only 1.7% of African American men at the time were able to do, he enrolled in college.

Using the same tenacity and intelligence that served him in his military service, Thomas applied for the brand new (and sadly short lived) Federal Student Board Program to cover the cost of his education at Delhi. (Thomas is pictured above back row, fourth from left.) The program was established in 1918 to provide vocational education and training to veterans who had been deemed to have a significant physical disability. The selection process for this benefit was rigorous and highly selective. Thomas was one of very few people of color to receive this hard-earned benefit. He choose to come to Delhi, to study poultry, chickens specifically.

Thomas was fully involved in life at Delhi (pictured above second from right with faculty and classmates). He joined the newly formed American Legion and advocated for expanded rights and protections for fellow military veterans. He was a fan of music; his favorite song was a tune called “Please Lend Your Lips to Mine”. We are unable to find a recording of it, but according to student newspapers it wasn’t an uncommon occurrence to hear Thomas singing it across the campus. He was a member of the Glee Club. A student, an advocate, disabled, a performer, Thomas was admired and liked by his fellow students and by professors. He embodied qualities that we see in Delhi students today.

During his last semester at Delhi he was named “Mr. Congeniality” by his fellow students who predicted he would live happily with his wife Camille (who he courted and then married in 1921) on a chicken farm somewhere. Their predictions proved to be mostly accurate.

Thomas didn’t go on to raise chickens. Instead Thomas began working at the historic Poughkeepsie Hotel and was soon promoted to manager of their largest commuter cafeteria. Professor Evenden, of Tower fame, was a frequent visitor and wrote updates on Thomas’ life in the student yearbook for several years after Thomas graduated. Evenden continued to write updates about Thomas longer than any other student. Thomas kept this job until he and his wife welcomed their daughter and only child, Hope Brown. After her birth they moved back to Harlem, near Thomas’ parents. By then the Harlem Renaissance was in full swing—jazz, poetry, and literature were all around the young family. Thomas worked for the rest of his life in numerous hotel industry positions. He held a job through the depression; his family never went hungry or lived on the streets. He even sent Hope to college continuing the legacy that was started by his own father.

Thomas died April 16, 1944. His wife fought to have him interred with full honors in the Long Island National Cemetery, with the other members of his unit. Thomas’ legacy is extraordinary at every stage of his life. He was the first member of his family to learn to read and write, the first member of his family born a free man, first to graduate from high school, to go to war for a cause that he believed in, to go to college, and possibly the first to study the habits and rearing of the chicken, a pursuit he was indeed very passionate about. So much of his achievements mirror the struggles and triumphs of students every day at SUNY Delhi.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The U.S. joined the ‘Great War’ 100 years ago. America and warfare were never the same.

By Michael E. Ruane, Washington Post, April 3, 2017

At night when things were quiet in the “jaw ward,” the wounded doughboys would take out their small trench mirrors and survey the damage to their faces.

Noses had been shot off in the fighting at Saint-Mihiel. Chins were destroyed in the Meuse-Argonne offensive. Mouths had been torn apart in the battle of Belleau Wood.

It was 1918, and Clara Lewandoske, a 25-year-old Army nurse from Wisconsin, was caring for these cases in a Red Cross hospital in Paris. “They were wonderful boys,” she recalled, and rarely complained.

But at night, if she saw one with a mirror, she would go to his bedside and start chatting. “Get them off of the subject,” she said. “Invariably, you’d get them to sleep.”

In time, they got used to their injuries. “We all did,” she said. “It was just one of those things.”

Lewandoske and her “boys” were among the millions of Americans who served in World War I--soldiers, sailors, nurses; white, black and Latino--who were caught up in the cataclysm, which the United States entered 100 years ago on April 6.

Among them was an Army sergeant from Iowa named Arnold Hoke, who would one day become Clara’s husband.

Tens of thousands from their generation would perish on the battlefield--25,000 in one six-week period alone--and many thousands more would die of disease.

Others came home physically or emotionally broken.

This month, the Library of Congress, the National Archives, the Smithsonian Institution, and the National World War I Museum and Memorial, in Kansas City, are marking the anniversary with exhibits, lectures and commemorations.

World War I started in Europe in the summer of 1914, and ended on Nov. 11, 1918. The United States entered the conflict after France, Russia and Britain had battled Germany and its allies for almost three years.

And American might was brought to bear against Germany only in the closing months of the conflict, but just in time to help reverse the enemy’s huge, last-gasp offensive and end the war.

The United States, although badly divided, had been provoked to join the war by the sinking of neutral American ships by German submarines, and by a secret German deal to offer Mexico the states of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona if it joined the German cause.

The offer, outlined in the “Zimmerman telegram,” was sent in code by German Foreign Secretary Arthur Zimmerman to the German ambassador in Mexico.

It was intercepted, hit the newspapers March 1, 1917, and created a national uproar.

Five weeks later, in a one-paragraph congressional resolution, the United States declared war.

In those days, it was called the “Great War,” or simply “the world war,” because no other like it was imaginable.

Along with staggering death tolls, it generated memorable literature, geopolitical upheaval, hope, disillusion, Hitler, the Russian Revolution, and the seeds of World War II.

For Americans, it provided, among other things, trench food called “corn willy,” the Selective Service System, the double-edged safety razor, and George M. Cohan’s anthem, “Over there.”

Send the word, send the word over there That the Yanks are coming, the Yanks are coming The drums rum-tumming everywhere.

But over there, the Yanks would find nightmare landscapes scarred by trenches and shell holes, and “mud that swallowed men, machines and horses without a trace,” wrote historian David M. Kennedy.

There were horrific weapons like the flamethrower, the machine gun, and phosgene gas, and the bullet-swept region between the lines known as no man’s land.

It was “industrialized death,” as the late art critic Robert Hughes put it.

When the U.S. entered the struggle in 1917, the conflict already had claimed 5 million lives.

But the Yanks were game.

So prepare, Cohan’s lyrics went, say a prayer, Send the word, send the word to beware We’ll be over, we’re coming over And we won’t come back till it’s over, over there.

Sgt. Arnold S. Hoke and his men had just hauled a supply of rations and ammunition overnight to their comrades at the front, and by the time they arrived the food was cold and congealed in grease.

In the dark and the rain, he and his detail had gotten lost, and they had not found his company until after dawn.

But the famished soldiers gathered in a patch of woods in the Argonne Forest, in northeastern France, to devour the food anyhow.

“The men lined up, and they started to dish out this food to them,” Hoke remembered. “The captain told me to--he knew I’d been up all night--and he told me to go over there in the basement of this farmhouse and get a little sleep.”

Hoke, 25, was a veteran who had served on the Mexican border in 1916.

He had been honorably discharged and had reenlisted after the United States entered the war.

A native of Spaulding, Iowa, he was assigned to recruit local Iowa men for what became Company M of the Army’s 168th Infantry Regiment.

By mid-1918, he and his men already had been through a lot, he recalled in a tape recording he made on April 12, 1971, that is now part of the Veterans History Project at the Library of Congress.

Often, the soldiers would talk about what they would do when they got home, “all kinds of silly things,” Hoke said. He planned to go to the local drugstore and have a thick pineapple malt as soon as he got back.

One doughboy, a man he had recruited from Atlantic, Iowa, said he figured he would be wounded, lose a leg, and meet his comrades at the train station. “I’ll get back home before you guys,” he told his buddies.

He’d have a hollow artificial leg, fill it with whiskey, and pass it around so all the boys could have a drink.

As Hoke rested in the farmhouse that day, German artillery had zeroed in on the trees where his comrades were eating.

“They threw a salvo of shells into this woods,” he said. “And they caught our men all lined up waiting for their chow.”

Fifteen to 20 men were killed, and about 30 were wounded, he remembered, including the man from Atlantic.

One of his legs had been practically blown off, Hoke recalled, and was just hanging by a few ligaments. He was conscious as he lay on the ground, and didn’t seem to be in a lot of pain.

“You guys thought I was kidding,” Hoke remembered him saying. “I’ll meet you at the depot with that wooden leg full of bourbon.”

Hoke said the soldier was taken to a battlefield dressing station, where the damaged leg was amputated. But the man died in an ambulance en route to the rear.

“I apologize for a rather unpleasant war story,” Hoke said on the recording. “Let me assure you there’s nothing pleasant about war, in any shape or manner, and I just hope that nobody will ever see another one.”

The day after he got home from France, he went to the drugstore and got his pineapple malt.

Nurse Clara Lewandoske recalled only one night when she fell apart during the war.

It was in Paris’s Lycée Pasteur, a high school that had been made into a 2,400-bed hospital, during a period of heavy fighting, when the wounded and sick soldiers would come pouring in from the front.

Some of the cases were horrific.

She once found a soldier who had wandered from his bed.

“It was a gorgeous moonlit night,” she recalled. “I came out in the hall. Here was this patient sitting in the doorway. He had taken his bandage off, and it looked like half of his head was gone. It was a horrible sight. It shook me more than anything else in the whole war.”

“We got him back to bed, and he died before morning,” she said.

Lewandoske had 36 patients in four wards to care for. At night, she and other nurses walked the corridors with lanterns shrouded with denim, to guard against air raids, she recalled.

They often worked on patients by candlelight.

One night it got to be too much.

“I was a pretty calm individual,” she said. She had been orphaned at 9 and raised by the family of a local minister. Back home, she had once assisted at a surgery done on a dining room table.

But during an awful night in the hospital, with soldiers crying out from all over, “I did cave in,” she said. “I got hysterical.… We just couldn’t get around to everything. We had hemorrhages … [and] a lot of sick boys.”

It was heartbreaking. “We were mother and sister and home to them,” she said.

On Nov. 11, 1918, the war ended with an armistice. She happened to be in downtown Paris when word came.

“All hell broke loose,” she recalled. “It was a terrific thing. You didn’t know whether you’d survive to or not.… It was just the wildest time.”

American nurses were hugged and serenaded, she said. “We saw our chief nurse … she was quite old, and they had her on a cannon, pulling her down through the main streets of Paris.”

Clara and Arnold came home from the war in 1919.

In September 1921, she was a delegate to the American Legion convention in Kansas City. Also in attendance was Arnold. They met and fell in love. They were married Nov. 22, 1922, lived through the Depression, and raised two children.

Arnold died July 30, 1971, four months after they recorded their memories. He was 78. Clara died June 27, 1984, at the age of 91. According to granddaughter Patricia Munson-Siter, they are buried side by side in the military section of Greenwood Memorial Park, in San Diego.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Some years ago I received a photo from Greenfielder, James F. Cannon. It was of a John R. Cannon, taken in France during his service in World War One. Along with the photo he also sent me a document regarding African American soldiers who served in the trenches of World War One. As part of my contribution to Black History Month, I’d like to reprise the information Mr. Cannon sent me. This was originally published on my blog in 2008.

John R. Cannon – France WWI

Judge James F. Cannon

African-Americans and World War One The dichotomy of American involvement in World War One was, of course, that America was in the war fighting to make the world safe for democracy, but many African Americans in the United States did not enjoy that very premise.

While the American military leaders had little faith in African American ability in combat, they acknowledged that everyone would be needed in the war effort nonetheless. With the severance of diplomatic relations with Germany in March 1917, a month before the U.S. declared war, the First Separate Battalion (Colored) of the Washington D.C. National Guard was mustered into federal service to guard the White House, Capitol and other federal buildings.

From most accounts, African American leaders backed America’s entry into the war. In one instance, the secretary of the NAACP said that patriotism was fanned into a flame in Harlem.

While there were regular Army units of African Americans in service at the start of the war, the 24th and 25th Infantry and the 9th and 10th Cavalry, the Army command decided to use only National Guard and drafted units in Europe. The Regular army units would provide cadres of non-commissioned officers and specialists for the overseas units.

The total number of African-American men called under the Selective Service Draft Regulations during 1917-1918: 367,710

Mistreatment of soldiers of the 24th Infantry stationed in Houston led to disturbances between the soldiers and civilians in August 1917 which resulted in some civilian deaths and the executions of 13 soldiers of the 24th Infantry.

While the soldiers expected the uniform of the United States to be accorded proper respect, the reality of many situations, especially in the south, did not support this belief.

Some National Guard organizations fared better. The 8th Illinois National Guard, which became the 370th Infantry Regiment was the only guard organization with a full complement of African American officers, which was a source of pride. It had seen combat service on the Mexican Border in the years just prior to 1917

On the whole training facilities and quality of training for African American troops was substandard

With a few exceptions like the officer training camp at Camp Hancock, Georgia where the commander insisted on good training and proper respect and the instructors were French and British Officers.

Social support systems for soldiers were in place, with The Knights of Columbus, Salvation Army and the Red Cross doing a fair job of helping the troops with integrated services.

In most African American communities there was overwhelming support of the Liberty Bond drives in 1917.

On the homefront, the contributions to the war effort were varied and successful, including: The Women’s Auxiliary of the 15th regiment; individual efforts by Eva D. Bowles, Secretary of the Colored Women’s War Work in Cities. Alice Dunbar Nelson, the recognized leader of mobilization of African American women for the Council of National defense. Louise J. Ross, the chairperson of the New Orleans Chapter American Red Cross.

African Americans worked with the U.S. Department of Labor, the national Bureau of War Risk Insurance, the Women’s Motor Corps, nationwide war fund drives, the War Camp Community Service, war-time National Food Administration Young Women’s Christian Association and Young Men’s Christian Association, the American Red Cross Nurses and Canteen Workers. One reference described that when the African American 805th Pioneer Infantry passed through Kansas City, Kansas heading for Europe, they were served by a canteen committee and supplied with candy, chewing gum, smokes and matches.

African Americans were employed in a number of war industries, including munitions production. There were the Organized Women Knitters and the Circle of Negro War Relief.

Mr. Emmett J. Scott, of the Tuskegee Institute, was Special Assistant to the Secretary of War, Newton Baker. Mr. Scott became a noted historian of the African American efforts in the war.

The first African Americans in military service to be in combat zones were in the U.S. Navy and were among the service personnel landing the first troops of the American Expeditionary Forces in France.

While it is estimated that 1/3 of all labor troops in Europe were African Americans, it is not true that all were assigned to labor units.

The earliest combat units to reach France were assigned to French divisions and this included the former 15th New York, which became the 369th Fighting Rattlesnakes, part of the 93rd Division (provisional). Lieutenant James Reese Europe led the famous 369th Regimental Band.

Sergeant Henry Johnson, 369th Infantry was the first AMERICAN recipient of the French Croix de Guerre for bravery. Private Needham Roberts, 369th Infantry, was the second recipient. On May 14, 1918, a German raiding party wounded both men and when they attempted to take Roberts prisoner, Johnson fought with his rifle butt and bolo knife to free him. They killed four Germans and wounded several others. A posthumous Distinguished Service Cross was awarded to Henry Johnson in 2003.

The 369th Infantry Regiment took part in the July 15-18 Champagne-Marne Offensive, then occupied the lines in the Calvaire and Beausejour sectors, and by mid August, the 369th had been in the line for 130 days and by the end of the war had been on the FRONT line for a total of 191 days.

With the 371st and 372nd Regiments, the 369th fought in the Meuse-Argonne offensive between September 26 and October 8th.

Horace Pippin, a member of the 369th kept and illustrated a journal of his experiences and these events would later play a large part in his work as a noted artist. Here he wrote with a sketch that the “guns were strong and all we could do were to wait.”

The 370th participated in the Oise-Aisne operation between September 15 and October 13th, and October 28 to November 11th, 1918.

Corporal Freddie Stowers of the 371st Infantry lead a squad against a strong German position on September 28, 1918 and although mortally wounded, Stowers, a 21 year old from North Carolina, urged his men on to defeat the Germans. His commanding officer recommended Corporal Stowers for the Medal of Honor. It was presented posthumously in 1991.

Lieutenant Colonel Otis B. Duncan of the 370th Infantry, was the highest-ranking African American in the American Expeditionary Forces.

The 92nd (Buffalo) Division participated in the occupation of the Saint Die Sector from August 23 to September 20, 1918

Second Lieutenant Aaron R. Fisher, 366th Infantry, in the middle of the photo, was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross “for extraordinary heroism in action, near Lesseux, France, September 3, 1918. He showed exceptional bravery in action when a superior force of the enemy raided his position by directing his men and refusing to leave his position, although he was severely wounded. He and his men continued to fight the enemy until the latter was beaten off by a counterattack.” He was from Lyles, IN.

The 92nd took part in the Meuse-Argonne battle from September 26 to October 3rd.

First Lieutenant Robert L. Campbell, 368th Infantry was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross “for extraordinary heroism in action near Binarville, France, September 27, 1918. During the afternoon of September 27, Lieut. Campbell saw a runner fall wounded in the middle of a field swept by heavy machine gun fire. At imminent peril to his own life, and in full view of the enemy, he crossed the field and carried the wounded soldier to shelter.” Lieutenant Campbell was from Greensboro, NC.

The 92nd Occupied the Marbache Sector, October 9 – November 11 and participated in the attack of the 2nd Army November 10-11.

The 92nd had 1570 battle casualties and the 93rd, 3927.

Kansas Citian, Private Grant McClellan wrote home to his wife a number of letters describing his experiences

In one he related, “You asked me what Division I was in when we came over. We were the last part of the 92nd Division but when we got to the front they were resting and we went over the top with the 28th Division.”

The artist, Edward Tanner, who had ties to Kansas City, was too old at 58 in 1917 to serve in the military, so he joined the American Red Cross in France. He developed a plan to grow produce and raise livestock around military hospitals to provide better food and boost morale for the convalescent soldiers. By the summer of 1918, his program was a great success.

In September 1918, he received permission to sketch in the Military Advance Zone and he produced two lasting images: a charcoal drawing, “American Red Cross Canteen, World War One,” where he specifically included an African American soldier and again in the painting “American Red Cross Canteen at the Front.”

Tanner mustered out of Red Cross service in June 1919 and his painting “The Arch” was of the solemn festival of 13 July 1919 in honor of the dead.

Pioneer Infantry regiments were organized in the summer of 1918 and given standard infantry training so that if necessary they could be used in combat

Pioneer infantry regiments worked behind the front lines in the Argonne Forest and at St. Mihiel where they built narrow and wide gauge railroads and macadam roads for the movement of light and heavy artillery and supplies.

the 805th was rushed in to repair a road near Varenne, which had been so damaged by German shellfire that ammunition could not be moved forward. The Pioneers worked through the night with shells falling around them. Some also worked in burial details, often under shellfire. 7 of the 17 African American Pioneer Infantry Regiments were entitled to wear battle clasps on the Victory medals whereas of the other 20 Pioneer Infantry regiments, only 8 were.

The 809th Pioneer Infantry had a notable baseball team. It won the championship of the St. Nazaire league and finished third overall in the AEF.