#bambara legends

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Some of the most memorable scenes from the 1987 Malian film Yeelen by Souleymane Cissé.

Yeelen means "brightness/light" in Bambara.

Set in the 13th century, the film tells the legend of Niankoro, the son of the sorceror Soma, and ultimately their fateful confrontation.

Soma, upon seeing a vision in which his son will be the death of him, deigns to slay his son. Niankoro leaves his mother and receives a prophecy from a hyena-man, then embarks on a mystical quest to defeat his father, who is tracking him via Kore magic post through Bambara, Fula and Dogon lands.

After impressing a Fula king with his magic, and helping his men win a war against some rivals, Niankoro receives his wife Attou (after "curing" "her" infertility and the 2 laying together).

The young couple journeys across the arid sun-scorched landscape into the peaceful escarpment where Niankoro's uncle dwells. The junior shaman receives his magic Kore's Wing (wooden sorceror's implement) from his uncle (Soma's benevolent twin), to evade capture, track his father, and ensure the fulfillment of the noble prophecy of he and Attou's descendents.

#sahelcore#mali#malian film#souleyman cisse#souleyman cissé#bambara legends#yeelen#yeelen film#niankoro#kore's wing#komo society#dogon#fula#the sahel#west african legends#african fantasy film#80s movies#sahelian film

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

As I am making my way down the Dictionary of Female Myths, I thought of sharing some articles not about the Greco-Romans for once! And since we are in summer – it means beach, water, sea – so welcome this loose translation/vague recap of an article about the myth of the Mamy Watta, written by Lilyan Kesteloot!

Kesteloot presents the myth of the Mamy Watta as being present across most of the shores and coastal areas of Africa, and as an equivalent to the myth of the mermaid in Europe. Like her, the Mamy Watta is a “lady of the waters” or a “water woman” who lives in the depths of the sea, and has an habit of seducing human men – but any further correspondence between the two legends stops there.

The several Mamy Watta (aka, “mamy water”) find their origins in the religious animism of the continent: they are first and foremost spirits and goddesses that received a worship. For example, the sea goddess Yemandja wo is present among the pantheons of the Yoruba, Ewe and Fon (Nigeria, Togo, Benin). The imagery of the rituals depicts Yemanda with long black hair contrasting with a light-colored skin ; often her half-naked body is surrounded by a long snake. She has her own priestesses, and her faithful followers: her cult and myths were transported, almost without modification, to Haiti and Brazil, due to most of the imported slaves of these countries coming from the South-Western coast of Africa. But the Mamy Watta of Africa is also found all throughout the Antilles (West Indies), under the name of “Manman di l’eau”.

On the shores of Senegal, the myth of the Water Lady is very active and linked to specific rituals. She is one of the “rab”, the genies that haunt the sacred places of the country, and to which one must make sacrifices only when they manifest. The sea-rab appears in men’s dreams and “calls” for them. The one who has been “called” during his sleep must answer this call, or face grave troubles. Usually he mut go see a specialist, a “ndeupkat”, who will reveal to him the name of his rab, how to satisfy it, and what he is forbidden to do. The man will have to regularly offer the rab milk and millet porridge, and it will become his personal protecting spirit. This alliance can however enter in conflict with the man’s human marriage, or the relationship between the man and the rab can deteriorate if there is a form of negligence. Then, the rab becomes not a protector but a tormentor, by disturbing the spirit and twisting the behavior of the “unfaithful” partner. The man will either suffer from a madness in the form of regular mental breakdowns, or from a long and deep depression. This type of rab-caused disorders are well-known among the Wolof, Lébou and Sereer. To heal the victim, one must gather specialists to organize a “Ndeup”, a ceremony which lasts from three days to a week. Its purpose is to reconcile the sick man and his rab, by sacrificing a cow, painting the man with the cow’s blood and making him drink it, then covering him with white veils. The rab is prayed to with lengthy melodies, and finally one must take the sick man take a bath in the sea – supposedly healing him and reconciling him with his “sea-bride”. To put it briefly: one can never get rid of a sea-rab, one must simply learn to live with it. The rab can sometimes appear not as a woman, but as a man – however in these cases, it always calls out to women rather than men.

Another type of Mamy Watta manifestations can be identified at the mouth of rivers. It is considered that these legends were born out of the sighting and presence of manatees/sea cows, large sea-mammals with breasts: they are perceived as the manifestations of the water-spirit in countries such as Cameroun, Gabon and Congo. The encounter with these spirit-women is not codified by religion: rather, when someone is harassed by one, it is considered as a charm or spell that must be dispelled by a healer. However, among the Douala, the “Djengu” is a key part of the initiation rituals of the Ngondo society.

Finally, sometimes the Mamy Watta can live inside the continent, in lakes and rivers. We know, for example, of Faro, the twin sister of the god Pemba, a primordial goddess of the Bambara mythology. She lives within the Niger river and commands fecundity, both human and vegetal. She is linked to the problems women must face, and to the rituals surrounding the birth of children. She has priests dedicated to her: she can appear as a woman, but usually manifests as a fish ; specific fish species, such as the catfish, are considered her companions. Further away in the Niger river, by the area of the Niamey, another water-spirit rules: Harakoy. Legend claims she was a Fulani woman who was seen naked in her bath, and out of shame she threw herself in the river, never to come out of it again. Ever since, she lives in the water: the fishermen worship her, and so do the Sonrhaï, riverside farmer, and she regularly appears by the side of other local deities. There is also Mame Coumba Lamba, who rules over the Senegal river and the city of Saint-Louis: she is said to be responsible for either the abundance or rarity of fishes, as well as the sudden floods of the river. A last example would be Mame Yungume, who haunts the mouth of the Gambie and Saloum rivers.

The presence of those water-goddesses is very prominent across the African continent, not to say almost banal – and those listed above are but a handful of them. It is notably because the myth of the Mamy Watta is still very much alive and active in Africa, unlike the legend of the mermaid in Europe. Be it individual or collective, as a long as a myth finds roots within rituals or a cult, it becomes part of the religion. Most of the legends described here are tied to local religions still in full strength today, while the sirens of Odysseus or the Little Mermaid of Andersen were reduced a long time ago to mere literary figures.

The image, or rather the very concept of the “women” that comes out of those water-ladies is not clear-cut or one-sided. If in Europe the mermaid is always a beautiful seductress who is dangerous to the sailors, in Africa the appearance and roles of the Mamy Watta are diverse. The rab described above, for example, are not particularly graceful or charming – they can even appear as old people, since they are called “Mame”, which means “grandmother”. Their manifestations are sometimes scary, and they can sport monstrous appearances. As for Faro, the main goddess of the Bambara mythology, she appears to her chosen ones as a mother rather than a wife, when she doesn’t take the shape of a giant fish.

The behavior of the Mamy Watta is ambivalent, and mankind’s alliance with them just as ambiguous. If one honors and worship the Mamy Watta, she will favorize you. But if you offend a Mamy Watta, by either transgressing a rule or neglecting a sacrifice, she will get angry and persecute you. But are they more demanding or capricious than the other spirits and gods of Africa? One cannot really claim such a thing, their role even seems to be quite positive: they do not wish the destruction of their human partners. They are rarely wicked, as long as the terms of their alliance/union are respected ; and this is unlike Mousso Koroni for example, the goddess of disasters of the Bambara cosmogony, who takes the appearance of a witch and always manifests herself with violence and destruction.

Sometimes, the Mamy Watta can be androgynous, sporting masculine traits ; other times they actually have a family of their own: Faro for example was said to have a husband, and Faro-children who stole vegetables from the gardens near the river. The Mamy Watta, whose tales are always told by moonlight, are always ambiguous, as much in their role as in their gender.

#mamy watta#african legends#african myths#mermaid#african goddesses#african religions#yemandja#bambara mythology#faro#mythological archetypes

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cissé made history as the first Black African director to win a feature film award at the Cannes Film Festival, earning the jury prize in 1987 for Yeelen (Brightness), a film inspired by the legends of the Bambara people. In 2023, he was honoured with the Carrosse d'Or, recognizing his bold and influential contributions to cinema, though the award was briefly stolen from his home in 2024 before being recovered.

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

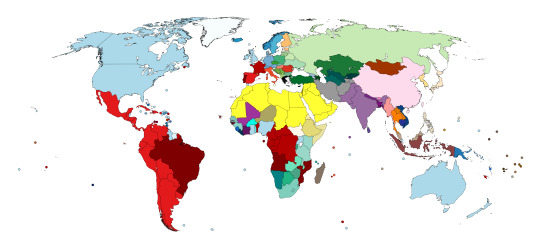

Most commonly spoken language in each country

I had to separate the legend from the map because it would not have been legible otherwise. I am aware that the color distinctions are not always very clear, but there are only so many colors in the palette.

The legend is arranged in alphabetical order and languages are grouped by family (bullet points), with branches represented by numbers and followed by the color palette languages within them are colored in, as follows:

Afroasiatic

Chadic (Hausa) — ocher

Cushitic (Oromo and Somali) — light yellow-green

Semitic (from Arabic to Tigrinya) — yellow

Albanian — olive green

Armenian — mauve

Atlantic-Congo

Benue-Congo (from Chewa to Zulu) — blue-green

Senegambian (Fula and Wolof) — faded blue-green

Volta-Congo (Ewe and Mooré) — bright blue-green

Austroasiatic (Khmer and Vietnamese) — dark blue-purple

Austronesian

Eastern Malayo-Polynesian (from Fijian to Wallisian) — dark brown

Malayo-Polynesian (Palauan) — bright brown

Western Malayo-Polynesian (from Malagasy to Tagalog) — light brown

Eastern Sudanic (Dinka) — foral white

Hellenic (Greek) — black

Indo-European

Germanic (from Danish to Swedish) — light blue (creoles in medium/dark blue)

English-based creoles (from Antiguan and Barbudan to Vincentian Creole)

Indo-Aryan (from Bengali to Sinhala) — purple

Iranian (Persian) — gray

Romance (from Catalan to Spanish) — red (creoles in dark red)

French-based creoles (from Haitian Creole to Seychellois Creole)

Portuguese-based creoles (from Cape Verdean Creole to Papiamento)

Slavic — light green (from Bulgarian to Ukrainian)

Inuit (Greenlandic) — white

Japonic (Japanese) — blanched almond

Kartvelian (Georgian) — faded blue

Koreanic (Korean) — yellow-orange

Kra-Dai (Lao and Thai) — dark orange

Mande (from Bambara to Mandinka) — magenta/violet

Mongolic (Mongolian) — red-brown

Sino-Tibetan (Burmese, Chinese*, and Dzongkha) — pink

Turkic (from Azerbaijani to Uzbek) — dark green

Uralic

Balto-Finnic (Estonian and Finnish) — light orange

Ugric (Hungarian) — salmon

* Chinese refers to Cantonese and Mandarin. Hindi and Urdu are grouped under Hindustani, and Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin, and Serbian are grouped under Serbo-Croatian.

#langblr#lingblr#spanish#english#french#german#catalan#russian#mandarin#hausa#somali#arabic#albanian#armenian#swahili#ewe#moore#wolof#vietnamese#samoan#palauan#malay#dinka#greek#tok pisin#hindustani#persian#haitian creole#papiamento#greenlandic

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Exanding on Alastor's matrilineage

Alastor’s grandfather can trace his roots back to the Bambara, and might also have partial heritage from the Kongo kingdom. He is not of Haitian descent. Conversely, Alastor’s grandmother can trace her matrilineage to Haitian slaves, who arrived in New Orleans after the Haitian Revolution. I have yet to define her patrilineage. Similar to the real-life Marie Laveau, she might also have roots in the Wolof people and conducted ceremonies in a similar fashion to those in Haitian Vodou. In addition to Marie Laveau, there are similarities between her and the real life high priestess Betsy Toledano.

Because she replaces Marie Laveau, Alastor’s grandmother fundamentally altered the development of New Orleans Voodoo. As such, more Haitian (and Dahomean) elements are present.

Major differences include:

The Damballah character fuses elements from the real life Blanc Dani and Grand Zombi. There are parallels between his relationship to Alastor’s grandmother, and the relationship between Grand Zombi and the real life Marie Laveau.

The Baron Samedi and Maman Brigitte characters (really, the Gede) are imported from Haitian Vodou into New Orleans Voodoo. They are different from their real life counterparts, in that they fuse elements from the Haitian Gede and Kongolese spirits of the dead. (Did you know? The word “zombie” is derived from the Kongo term Nzambi. The “Samedi” in “Baron Samedi” might also be derived from this term!)

The Erzulies are imported from Haitian Vodou to New Orleans Voodoo, where Erzulie Dantor outright replaces Mother Mary.

The decision to replace Marie Laveau with a Black woman of Haitian descent is not to confuse Haitian Vodou with New Orleans Voodoo; rather, it is to introduce Erzulie Dantor as a replacement for Mother Mary. I am operating under the assumption that there is no Jesus Christ, therefore no Mother Mary in the Hellaverse. But because Catholicism is so important to the formation of New Orleans Voodoo, it is necessary for some sort of deity to fill the void left by Mother Mary. Out of all possible options, I would argue that Erzulie Dantor is the single best choice.

* * *

The description of Alastor’s grandmother was inspired by Carolyn Morrow Long’s book A New Orleans Voudou Priestess. She was not just inspired by Marie Laveau, but other Voodoo priestesses, especially the Black high priestess Betsy Toledano.

During the time of Marie Laveau, the Black free woman Betsy Toledano was treated as a scapegoat. She was harassed several times by white authorities, targeted by the police and newspapers. When she was arrested for “unlawful assembly of free people and slaves”, she “defended her right to practice the religion of “the mother-land” learned from her African grandmother”: https://books.google.com/books?id=_XzSEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT230&lpg=PT230

FULL CITATION: Long, Carolyn Morrow. A New Orleans voudou priestess: The legend and reality of Marie Laveau. University Press of Florida, 2007.

#commentary#hazbin hotel fanfiction#follow for the single craziest piece of fanfiction in the entire Hazbin Hotel fandom!#alastor's maternal grandmother#alastor's maternal grandfather#hazbin hotel ocs#i had the balls to make alastor's parents AND grandparents my DeviantArt OCs...jesus christ!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Chiwara

A Chiwara is a ritual object representing an antelope, created and used by the Bambara ethnic group in Mali. According to Bambara legend, Chiwara used his antlers and pointed stick to dig into the earth, making it possible for humans to cultivate the land.

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

2024 (66)

nausea (jean-paul sartre) - 6/10 the weans (robert nathan) - 10/10 legends of vancouver (e. pauline johnson) - 8/10 woman running in the mountains (yuko tsushima) - 9/10 every man for himself and god against all (werner herzog) - 9/10 i don't want this poem to end (mahmoud darwish, mohammed shaheen ed.) - 7/10 the temple of the golden pavilion (yukio mishima) - 9/10 miss julie (august strindberg) - 8/10 the father (august strindberg) - 8/10 interpreter of maladies (jhumpa lahiri) - 10/10 on earth and in hell: early poems (thomas bernhard) - 6/10 the slave girl (buchi emecheta) - 10/10 the homecoming (harold pinter) - 9/10 the boy who followed ripley (patricia highsmith) - 9/10 beartown (fredrik backman) - 9/10 hymns to the night (novalis) - 8/10 in a german pension (katherine mansfield) - 7/10 the tunnel (ernesto sabato) - 8/10 between two worlds (miriam tlali) - 9/10 tales of hulan river (xiao hong) - 10/10 family ties (clarice lispector) - 10/10 butterfly burning (yvonne vera) - 9/10 i saw ramallah (mourid barghouti) - 10/10 fences (august wilson) - 10/10 almond blossoms and beyond (mahmoud darwish) - 8/10 «selected stories of xiao hong» (xiao hong, howard goldblatt ed.) - 10/10 the stream of life (clarice lispector) - 9/10 the perfect nine: the epic of gikuyu and mumbi (ngugi wa thiong'o) - 8/10 over all the mountain tops (thomas bernhard) - 7/10 why did you leave the horse alone? (mahmoud darwish) - 8/10 brocade river poems (xue tao) - 9/10 human mourning (jose revueltas) - 8/10 return of the spirit (tawfik al-hakim) - 9/10 the visit (friedrich durrenmatt) - 10/10 down and back: on alcohol, family, and a life in hockey (justin bourne) - 10/10 juha (juhani aho) - 10/10 only in the meantime & office poems (mario benedetti) - 9/10 springtime in a broken mirror (mario benedetti) - 10/10 the sonnets (stephane mallarme) - 7/10 bestiary: or the parade of orpheus (guillaume apollinaire) - 8/10 maze of justice: diary of a country prosecutor (tawfik al-hakim) - 9/10 tales and stories for black folks (toni cade bambara et al) - 10/10 the black woman (toni cade bambara et al) - 10/10 fictions (jorge luis borges) - 10/10 a raisin in the sun (lorraine hansberry) - 9/10 memory for forgetfullness (mahmoud darwish) - 10/10 black friend: essays (ziwe) - 10/10 are prisons obsolete? (angela y. davis) - 10/10 waiting for godot (samuel beckett) - 10/10 the garden party (vaclav havel) - 9/10 dust tracks on a road (zora neale hurston) - 9/10 wild thorns (sahar khalifeh) - 10/10 everything good will come (sefi atta) - 10/10 men in the sun and other palestinian stories (ghassan kanafani) - 10/10 minutes of glory and other stories (ngugi wa thiong'o) - 10/10 midaq alley (naguib mahfouz) - 9/10 a man of letters (taha hussein) - 7/10 the beggar's opera (vaclav havel) - 8/10 soul gone home (langston hughes) - 8/10 mulatto (langston hughes) - 10/10 the weary blues (langston hughes) - 9/10 the quarter (naguib mahfouz) - 10/10 pedagogy of the oppressed (paulo freire) - 10/10 after midnight (irmgard keun) - 9/10 a gentleman in moscow (amor towles) - 7/10 peace and its discontents (edward said) - 10/10

0 notes

Video

BALLAKE SISSOKO - Une histoire de Kora - 52' - Master bilingue - VOSTANG - R128 from Lucy Duran on Vimeo.

Oléo Films & Mad Minute Music, with support from the Aga Khan Music Programme & SACEM, TV5Monde, & Mezzo, present: BALLAKÉ SISSOKO, KORA TALES BALLAKÉ SISSOKO, UNE HISTOIRE DE KORA 53” documentary film Written and directed by Lucy Durán and Laurent Benhamou, 2023 World-renowned, award-winning Malian musician Ballaké Sissoko takes us on an unprecedented journey to follow the trail of his instrument, the kora, a West African 21-string harp whose origins are surrounded by legend. Shot on location, the journey begins at Ballaké’s home in Bamako, capital of Mali where he was born and raised. We hear his talented group of young kora students play sublime music on his rooftop, songs he has taught them from the traditional repertoire of his father, who was from Gambia but settled in Mali in the 1960s, early years of its independence. Ballaké’s cousin demonstrates the complex craft of making a kora, and takes Ballaké for the first time to visit the majestic rocky hills where the great Mali empire began. Travelling further westwards to Senegal and Gambia, to his ancestral homeland, Ballaké traverses by canoe the beautiful Casamance river to drop in on a family of kora players who keep alive the old traditional style of the instrument. Inspired, Ballaké plays the kora late into the night, to the sounds of crickets and night birds, on his way to visit a sacred location where according to myth, the kora was first invented by invisible spirits, the djinns. Narrated by celebrated Malian rapper Oxmo Puccino, this film takes us for the first time to the heart of the kora tradition, and to the mystique and legend around it. Language: Bambara, Mandinka, French. With English and French subtitles

0 notes

Text

This book. Is. Absolutely. Brilliant.

“The Salt Eaters” is one of those books that took me years to read. For some reason, I always seemed to begin to read it and after the first few pages I had to put it down. Part because I couldn’t grasp the concept of what was going on and because I had too much going on in my life. See, this book demands you be abandoned when you read it. After finally reading the book, I realized it was difficult to read because it was personal. It felt like a conversation I would have with my girlfriends. It was “an older book” that was still relevant. It gave me the feel of a Zora Neale Hurston book or Toni Morrison. It is time bending and revolutionary.

I was introduced to Bambara around the time I began to consume myself with literature from black women. The summer going in to my sophomore year of undergraduate school when I sat on the library floor and found Sanchez, Shange, Giovanni, Walker, Brooks, Jordan, Clifton to name a few. I was a theatre student, who also loved poetry, scouring for material to perform and interpret for auditions and competitions. Bambara was one of the names that kept coming up so I kept her on my list of authors that “changed the game”.

Those who know me know that I am a thrift store book shopper. I never buy used books for over $3.00 and one day (years ago) I came across this book:

Of course what attracted me was the cover, but inside were essays by all the women I had been self educating myself about. This book was Bambara’s first book, The Black Woman: An Anthology, in which African American women of different ages and classes voiced issues not addressed by the civil rights and women’s movements. I realized I needed to pick up a Bambara book and get to know her creatively. When I asked around what book to read first, everyone said “The Salt Eaters”. I remember trying to start this book for like two weeks until I justified with myself that this book was like “Meridian” by Alice Walker and “Song of Soloman” by Toni Morrison… I just didn’t get it. I put Bambara down and would come back to her a few times after that and could not get in to it. But when I did, it was a “game changer” for me!

Her novel “The Salt Eaters” centers on a healing event that coincides with a community festival in a fictional city of Claybourne, Georgia. In the novel, minor characters use a blend of modern medical techniques alongside traditional folk medicines and remedies to help the central character, Velma, heal after a suicide attempt. Through the struggle of Velma and the other characters surrounding her, Bambara chronicles the deep psychological toll that African-American political and community organizers can suffer, especially women. This material and subject matter was simply not being published. A brilliant and wise story!

Fast forward years later to 2018 and I sit in one of my grad school classes and on the book list is Bambara’s “The Black Woman”. All in time… all in time things will make sense and connect themselves. I am sitting in a setting where Bambara is being discussed as a scholar, black feminist and a creative. The most important thing, neither one was considered more important than the other. In my studies of Africana Womens Studies, interrupting the duality of women’s scholarship is a language encouraged for others to perceive and understand that black women scholars are shift makers and are both.

Today I honor Toni Cade Bambara on her birthday! Do yourself a favor, make sure you have these titles in your personal library:

Toni Cade Bambara, the scholar This book. Is. Absolutely. Brilliant. "The Salt Eaters" is one of those books that took me years to read.

#revolutionary#africana womens studies#black arts movement#black feminism#black feminist#black scholars#black woman#black women scholars#gender studies#literary icon#literary legends#the salt eaters#toni cade bambara#womanist#womens history month#womens studies

1 note

·

View note

Text

Yeelen

Yeelen directed by Souleymane Cissé is distinctively African that uses one of the most western cultural forms, film, to speak and present its non-western mind. Yeelen has guaranteed a place for the medium of film in the folklife of Africa. The film allows the audience to make new interpretations of African cinema and question or challenge their expectations and preconceptions regarding African cinema.

Yeelen is about a young man, Nianankoro, who sets on a journey across Mali to fulfill his destiny and challenge his tyrannical father Soma who fears his offspring’s magical powers. Niankoro flees with his mother and attempts to stay ahead while his father tries to track him down. Setting off on a journey to ask his uncle for advice his power matures with the help of the Peul and Dogon peoples, and after acquiring the sacred Wing of Kore, he engages in an epic battle with his father for the fate of the entire country. The film can be interpreted as the appropriation of the history and myth of Mali. Although the film is set in an unspecified time, it is widely believed that the film is based on the legend of Sundiata Keita, the thirteenth-century founder of the Malian empire who used magic to defeat an oppressive ruler.

The film walks a fine line between cultural specificity and universal appeal and can be regarded as an anthropological film. Yeelen immerses the viewer in a worldview that can only be fully comprehended through extensive study. The mere complexity of the rituals of sorcery, which include spitting, powerful wooden boards and amulets, symbolic human and animal figures, and distinctive patterns of speech and mimicry, invites audiences to linger over the foreignness and inherent beauty of Bambara culture. Every film reflects a distinctive cultural orientation that may make it difficult for many spectators to access or understand as subtle politics and experimental indigeneity cannot be grasped without also grappling with the politics of mainstream Africa. The film has a very deliberate and distinctive pace which is achieved through long takes, minimal editing, and shots that highlight the mise en scène and natural elements.

Furthermore, the film also contains thematic repetition of imagery that allows the visuals to operate symbolically. An example of this is when Attou takes her turn bathing in the purifying springs of the Dogon territory, we may recall the visual effect of a prior scene of ritual purification, as Nianankoro’s mother prays for her son’s protection. Another cinematic effect that could be considered is the blinding light. It plays an important role in the film, particularly in the climactic confrontation between Nianankoro and Soma. Cissé considers this endless cycle of the consolidation, destruction, and recreation of knowledge by each generation Yeelen’s most ‘universal aspect.

Yeelen has taken the art of film and reshaped it according to what they know. Its voice is not distant not objective it is simply telling a story that is true to their world.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE RHYTHMS OF DIASPORA : Godwin Louis SPEAKS | JAZZ SPEAKS - http://www.jazzspeaks.org/the-rhythms-of-diaspora-godwin-louis-speaks/

"On the process of doing research for his upcoming album Global

" I’ve spent the last seven years exploring that and studying and understanding the connection that was brought to #Haiti from West #Africa. I’ve gone to Africa five times in the last four years. The music on my upcoming album, Global, is based on the music transported out of Africa, to the rest of the world via the transatlantic slave trade.

This process of exploration began thanks to a grant that The Jazz Gallery gave me to pursue my compositional voice. During that period of 2013-2014, I was noticing a lot of connections between Haiti and New Orleans. I was fortunate enough to live in both places, and I couldn’t help but notice the similarities in terms of culture, architecture, even in terms of cuisine, musically, of course. And then historically, I found major connections rooted in the Haitian revolution. In 1790 and 1804, you had a lot of affranchis, free people of color, that fled Haiti to what was then known as #French #Louisiana. And, of course, they brought their culture and their rhythm. So I was intrigued in that and I began exploring that music, and I presented some of that at the Jazz Gallery in June 2014.

And because of that, I was able to continue to dig even deeper. I went back “across the pond” to Africa to see some of the things that were brought in and how much they’ve changed, and I’ve extended those studies to South America as well.

I began to understand that whenever I see triple meter, that’s something that’s coming from West Africa. So that’s an area that spans from Senegal to Western Nigeria, and back then we would consider that as either Upper or Lower Guinea. In places like Haiti, you hear terms like that, where they’ll say “nég Guinea” meaning, a fella from Guinea. And then also, the other term that you would hear is “nég Kongo” meaning a person from Kongo, meaning a fella from Kongo, which is modern day Cameroon all the way down to Angola. And that’s sort of like “duple meter.” So in West Africa, you have a big triple meter connection, and whenever you see technical things that are in 6/8 or 3/4 , that kind of “Afro” sound that they call it in jazz: “Afro-Cuban”, “Afro-Jazz”….that triple sound is coming from West Africa: Yoruban rhythms, Dahomey, Benin, Togo, Ghana. But whenever we’re dealing with duple meter, which is some of the sounds found in Haiti and New Orleans—you know, Congo Square.

One of the hubs for a lot of the cultures that were transported is Haiti because, in Haiti, there were tribal religions that were preserved. You have rhythms for instance, called Nago, and I found that the Nago rhythm that I always heard in Haiti is actually coming from a tribe in Benin. Nago is pretty a much the Yoruba people in Benin. So if you’re in Nigeria, you’re Yoruban, but if you’re from Benin, you’re Nago. In Haiti, there is a rhythm called #Nago, and that’s very similar to what we know today as the swing rhythm. Sort of like when you’re listening to Elvin Jones, that feels to me like a Nago rhythm.

So, the Haitians were able to conserve and preserve some of those rhythms. And also we have #Kongo, which is also a rhythm that happens to be a duple meter rhythm, and those roots are coming from Kikongo culture from Central Africa. And then we have rhythms like #Yanvalou. All of these rhythms are associated with places in Africa, the names of kings, and so on. So I think because of what the Haitians achieved in gaining independence from slavery, they were able to keep a lot of those rhythms and a lot of those tribal names. Lots of people doing research on the African influence in the United States tend to bypass Haiti, but I really found it to be the hub. The three hubs are #Cuba, Haiti, and Brazil in terms of finding that pure connection to Africa. But again, researchers and #ethnomusicologists usually go to Cuba and #Brazil but don’t know anything about Haiti. So it was interesting for me to connect it all. 💡

On the compositional process and how it related to his research:

I spent a lot of time visiting certain regions and certain tribes and listening to the different sounds and the use of language in the music. I was in Mali listening and learning, and I was sitting in a rehearsal. It was fascinating to me the way that Bambara, which is the local dialect that they were singing in…it was interesting to me how the time signature was always based on the text. So a lot of the time, you would have an over-the-bar-line idea because of the text. And I would sit trying to figure it out, and I asked them: “why is it like that? This isn’t really 6/8…I heard a bar of 5 here, a bar of 6”. And then I was told, “oh no, this is all based on the text. So I have to finish the phrase, whether it falls on a bar of 4 or bar of 5. You Americans look at it like this, but for us, it’s all based on the text.” So for me it’s about exploring the rhythm in the language. I try to have the melodies match the feeling and rhythm of the language. And oftentimes, that means writing melodies that go over the bar line. I call that a “textual approach to melody”, which is the way they would do it in Mali or with the Dahomeys or in Benin.

Now, I think the next thing will be exploring East Africa. Going to Ethiopia, to Egypt, Kenya. Because I’ve found some interesting connections, historically and musically between East Africa and West Africa, but that’s for the next excursion.

I used to play in an Ethiopian jazz band called the Either/Or Ensemble, and that was really my introduction to African music in general. I got to play with the great Mulatu Astatke, and I’m actually featured on one of his albums. The band got to travel to Ethiopia and it was an amazing experience, and that was my first time playing that music. And I found that influence in Togo. Vodoo music in Togo uses that same scale called the Anchihoye. So I’m kind of intrigued. How did that mode get from Ethiopia to Togo?

On Haitian saxophonists that inspired Godwin:

I grew up listening to a lot of this Haitian saxophonist named Webert Sicot. He was known as the Siwel saxophonist. It’s sort of like the Caribbean or Haitian version of a Trad-Jazz or Dixieland style of playing. Sort of like Louis Armstrong in the way that Louis Armstrong emotes on the trumpet: all those beautiful melodic ideas. That’s called a Siwel. And I grew up listening to that kind of sound and that super-melodic way of soloing, and Webert Sicot was one of the kings of that sound. So I was learning a lot of this language through Webert Sicot without even knowing what it was. Webert Sicot was the king of a genre called Cadence Rampa that was influenced by the French Antilles, Martinique, Guadeloupe, Dominica. He was actually Nemours Jean-Baptiste’s [ the popular Haitian tenor saxophonist and bandleader] rival. Nemours Jean-Baptiste carved out the Compas genre as his own, so Webert Sicot decided to start his own style called Cadence Rampa. And they both are amazing musicians of course, but in terms of marketing, they decided to go their separate ways. Cadence Rampa was more French Antillean. But Compa became the music of the people because of the lyrics and accessible sound. "

SOURCE :

💡 READ MORE :

http://www.jazzspeaks.org/the-rhythms-of-diaspora-godwin-louis-speaks/

-------------------------------

💡Rock Paper Scissors - Godwin Louis - Godwin Louis Explores the Worldwide Impact of Afro-Caribbean Sounds and Concepts on Music and Takes them Global

https://godwin.rockpaperscissors.biz/dispatch/pu/25474

----------------------

GLOBAL by GODWIN LOUIS on Amazon Music -

https://www.amazon.com/Global-Godwin-Louis/dp/B07NDJ93NS

GLOBAL by GODWIN LOUIS on iTunes

https://itunes.apple.com/us/album/global/1451576702

GODWIN LOUIS | Global | CD Baby Music Store

https://store.cdbaby.com/cd/godwinlouis

----------------------------------

🎥 Watch "GODWIN LOUIS -

"I CAN'T BREATHE"

https://youtu.be/uHa_jaG9BRo

From his upcoming album:

G L 🌍 B A L

to be released on February 22, 2019

Music video featuring: Maleek Washington Directed by: Hans Johnson Blue Room Music

-----------------------------------

Godwin Louis | About💡

http://godwinlouis.com/

-----------------------

HAITI⭐LEGENDS

#GodwinLouis #Global

#Haitiansaxophonist

#NewCD #Feb22 #Jazz

#MaleekWashington #HansJohnson #NewMusicMonday #BlueRoomMusic

#jazzspeaks #musicresearch #rhythmsofdiaspora

#WebertSicot

#CadenceRampa

#NemoursJeanBaptiste

#AfroCaribbean

#Compas #CompasDirect

#BerkleeCollegeofMusic

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Vanished heroes

Meeting the partly human, partly superhuman, who embody the highest values of a society is truly an experience to remember.

It’s no wonder they carry with them the African culture’s history, values, and traditions. It was a pleasant encounter indeed.

- The Dausi from the Soninke

- Monzon and the King of Kore from the Bambara of western Africa

- The epic of Askia the Great, medieval ruler of the Shonghai empire in western Africa

- The epic of the Zulu Empire of southern Africa

- Sundiata from type Mandingo people of West Africa is the best-preserved and the best-known African epic which is a blend of fact and legend.

0 notes

Text

African Culture Gets the Spotlight in "African Heroes"

By design, video games are an entertainment medium versatile enough to serve a dual purpose. You may boot them up to leave the real world behind, but it's not unfathomable to think that you can learn something through these fantastical stories. We have to believe that was what Serge Abraham Thaddee felt when he conceptualized the idea behind African Heroes, a digital adventure intended at teaching African culture.

We can look at a number of games and find ourselves trekking across Africa. So few of them, though, actually focus on the rich, diverse, and vibrant culture that emanates from the world's second-largest continent. African Heroes strives to rectify that with an adventure that integrates real pieces of history while also doing what video games are meant to do - entertain. Across an exotic land that truly captures Africa's visual appeal, players will explore different facets of African culture, from the warriors and gods spoken about in the oldest legends to ritualistic dances of different African ethnic groups.

Thaddee's premier title puts players in control of M'Balia, a young girl from Guinea forced into an epic journey. When it's prophesied that the villainous Barthe Bely seeks to secure the N'Dmba, a mask for fertility and greatness, the elders of M'Balia's village appoint her as the only one that can stop him. Should she fail, the vile genius would have the power and numbers needed to invade all of Africa and claim the region as his own.

To stop Bely, M'Balia needs all the help she can get, and she'll find it in the warriors she meets along the way. Many of the characters the young girl encounters were inspired by or directly pulled from African history and lore. Soumaoro Kante, the 13th-century emperor of the Soussou empire, will ally himself with M'Balia and offer her necessary wisdom. Yobo Fissa (Mamiwata) emerges from ancient tales of a mermaid woman that symbolizes beauty and an abundance of fish. Fishermen often prayed to her for a bountiful catch, but Yobo Fissa plays a different role for M'Balia. Even the concept behind Barthe Bely is pulled from African folklore, which characterizes the ruthless geniuses (or gods) who seek to rule over humanity.

African culture will be spread throughout African Heroes, which will highlight aspects like the ritualistic dances of the Zulu warriors and the energetic doudoumba. M'Balia will also collect masks along the way that imbue her with powers related to their perceived symbolism. For example, the Ciwara mask of the Bambara people will grant the wearer incredible speed, a reference to the antelope figure it depicts. The more masks M'Balia collects, the better prepared she will be for her battle against Bely. For players, each new mask provides insight into their purpose in African culture.

While there is little gameplay to go off of, African Heroes appears to be a third-person action-adventure. The Kickstarter intro video provided a brief glimpse at the 3D environments that encapsulate Africa's beauty, from empty plains to lush jungles. We even get a glimpse at some of the wildlife M'Balia will encounter on her adventure, and it's clear that the development team did its research to perfect their movement.

Throughout her quest to stop Bely, M'Balia will be gifted powers by the masks she collects and the geniuses she encounters. A few of these were teased, though how they will ultimately work in-game is still one of the many mysteries locked up tight by the developers. Players that appreciate realism and striking graphics will love the game's handling of its human characters. Their lifelike depiction borderlines the uncanny and will help bring the game to life.

There may be plenty left to see of African Heroes, but from this brief tease, it's evident that Thaddee, along with the game's screenwriter and designer Mahmoud Toure and the artistic and operational director Kadiatou Conde, have sunk their passion for African culture and storytelling into the overall experience. Ultimately, the finished product is shaping up to be an exciting and informational adventure into an intricate and fascinating culture.

Thaddee and his small talented team are currently seeking backing for African Heroes on Kickstarter. With the help of generous backers, African history can take the spotlight in a video game that's equal parts fun and educational. As of July 23, 2020, the project earned $1,086 from 15 backers. Pledging to African Heroes can earn rewards like a copy of the finished game, a digital version of the soundtrack, and a video of the protagonist offering a personalized thank you.

African Heroes is expected to release on PS4 and PC, though a release date has yet to be set.

At SJR Research, we specialize in creating compelling narratives and provide research to give your game the kind of details that engage your players and create a resonant world they want to spend time in. If you are interested in learning more about our gaming research services, you can browse SJR Research’s service on our site at SJR Research.

0 notes

Text

Weeping Icon Interview

Weeping Icon

Weeping Icon is an experimental noise punk band based in Brooklyn, NY. All four members are long-time vets to the DIY Brooklyn music scene (former & current bands ADVAETA, Lutkie, Mantismass, Warcries, Water Temples), and they are breaking new ground with their explosive take on the traditional rock configuration. Their live show is immense and energetic; their addictive combination of searing riffs & rhythms, fearless vocals and thrillingly unexpected sounds – delivered through heaps of hair and controlled feedback – is expertly crafted into an enveloping landscape that doesn’t let up from start to finish. Their debut EP ‘Eyeball Under’ exhibits a gifted band with innovative and striking arrangements, showcasing each member excelling with beguiling aptitude… We talk to the band about primal energy, Russell Westbrook and Jane Goodall…

TSH: How would you describe the band camaraderie and level of concentration when new music is coming together?

Weeping Icon: We completely trust each other to develop parts, but if we’re stuck, we take long walks through the hallways. Our practice space is in an old pharmaceutical building that has been repurposed for just about everything imaginable, and it is completely twisted. Somehow we spend a lot of time in the bathroom talking, playing with construction materials, and generally making trouble.

TSH: For your EP entitled ‘Eyeball Under,’ what sort of lyrical expressions and perspectives do you feel primarily came into play?

Weeping Icon: This EP has a lot to do with primal energy. We are channelling a lot of the confusion and anger from current politics and we feed off each other’s intensity. There are a lot of raw expressions of anger, anxiety, and retaliation.

TSH: ‘Jail Billz’ is a stunning track. Talk us through how the band went about layering and structuring such a concise song…

Weeping Icon: Thanks. It was the first song we wrote, and it kind of set the scene for what we were going to make. Guitar and drums were the first parts written before the full band had formed, and the idea was just to make something loud, fast and physical. The other parts came together naturally from just trying to sustain the intensity and enhance it.

TSH: Moreover, what does a track like ‘Warts’ signify overall?

Weeping Icon: It’s about the impetus to lie and be secretive in protection of one’s own self-image/self-interest, and the private reassuring conversations we have with ourselves that tend to place more value on alleviating anxiety than being considerate of potentially impacted parties.

TSH: At what point in the process do you realise what you’re going to do vocally with the sounds that are being formulated?

Weeping Icon: Usually we improvise shouts, screams and nonsensical words to feel out the song. When the structures are a little bit more refined one of us feels possessed to write lyrics, haha! We all like to sing and write.

TSH: Can it at times be beneficial to not search for a specific statement and simply just embrace what comes out of you?

Weeping Icon: Yeah, I think that has been the process for writing this EP. We didn’t have a specific message, but we had a lot to say, haha. I think right now we are just trying to make something as raw and honest as possible, and usually that means figuring it out as it happens.

TSH: What sort factors do you feel are important to manifest with the band’s live offerings?

Weeping Icon: We try to channel unadulterated puppies. That is only partly a joke. We don’t stop between songs because we want to sustain the energy and for the set to be immersive. The transitions are always improvised so we are concentrating on each other and sensitive to the atmosphere the sound is building. We want people to feel very present.

TSH: In what ways does being immersed within your craft allow you to liberate yourself from stress and anxiety hurdles?

Weeping Icon: The importance of having something that belongs to you - that may be shared with other people, but isn’t made for other people - can’t be underestimated. Everyone should have a section of their lives dedicated to unadulterated self-expression: your tastes, your emotions, whatever gets your blood pumping. It’s the only real freedom you get in a world in which your success is contingent on how well you smile and stand up straight through the shit shower.

TSH: What gets played most on your YouTube binges?

Weeping Icon: Barry White, Bambara, Moon Duo, Kevin Drumm, Eleh, Young Thug. Also, the video for ‘Thunder Thighs’ by Miss Eaves - look it up now!

TSH: What brings about most laughter within the band?

Weeping Icon: Oh, we’re cheeky. We can’t tell you most of them but here are a few: the taxi driver who takes us to shows all the time and falls asleep at every red light. Sometimes we yell at him “hey! ya sleepin?!” and he laughs and keeps driving. Also, the guy who was walking around our practice space in socks that were pulled out several inches beyond his toes organizing piles of papers, and his strange Ikea scarf rack that had cables attached to it with twist ties that ended up in our practice room for several months. We hated it. Who uses twist ties for instrument cables?? Arrrgghhhh! Oh, and playing garbage hockey, with pipes and garbage.

TSH: Are certain members of the band passionate about Russell Westbrook?

Weeping Icon: Russell Westbrook is such a pure basketball player. It’s wildly inspiring to see him put everything out there, and for Oklahoma City of all places. He is absolutely one of my favourite players of all time. This question speaks to me, but the other 3 members were very confused. Haha! (SL).

TSH: Also, how much of a legend is Jane Goodall to you?

Weeping Icon: ALL THE LEGEND! She is the personal hero of two members of this band, one of whom is actually a cousin of hers and the other studied anthro and read all her books. SHE IS A MESSIAH!

TSH: Is The Sopranos one of Sarah’s all-time favourite shows? And what do the others like to watch?

Weeping Icon: Is it surprising that the Sarah who is the die-hard Sopranos fan is the Sarah from New Jersey? Just a tad bit shy of being obsessed with the show - have watched the whole series over a dozen times, cried when James Gandolfini died, hated the ending (mostly because it was ending)... Also, can’t tell if you are psychic or making very good guesses about us with these questions - or maybe you stalked our Facebooks??… I don’t knooooow… Other TV shows we also like are (collectively and separately, depending): Game of Thrones, The Handmaid’s Tale, SpongeBob, Rugrats, Rick & Morty, Sherlock, Ru Paul’s Drag Race, Twilight Zone, Curb Your Enthusiasm and John Oliver.

TSH: How do you like to stay positive amidst all the beldam in the world?

Weeping Icon: Band, art, shows, comedy, and maybe the only thing you don’t know already, weed. Hehe. (Sunglasses emoji).

TSH: What’s the Weeping Icon ethos as you venture ahead?

Weeping Icon: WE ARE 4 BLONDE BOYS TRYING TO HAVE A GOOD TIME. PLEASE NO UNSOLICITED DICK PICS, THX. HAVE A GOOD NIGHT. BYE.

Eyeball Under

1 note

·

View note

Text

From @idealai: I wanted to ask @gehayi , just for fun, what is one of your favorite Brows Held High (personally, the Devils - simply for the ending bit with Diamanda Hagan) and what is your favorite Shakespeare play?

God, I have so many favorite Brows Held High episodes. I’ve already mentioned the deconstruction of Roland Emmerich’s Anonymous. Here are some others.

The Fall (2007) (available below in a Russian sub), one of Kyle Kallgren’s earlier reviews, in which he rhapsodizes about the sheer mind-blowing visual beauty of a movie. This is also the first one of his reviews that got me to watch the movie he was talking about.

youtube

Yeelen (1987), a review of a Malian film that is based on a legend of the Bambara people. Kyle talks about it respectfully, starting off by pointing out similarities to films that his audience would likely know and then seamlessly seguing into an explanation of the parts that would seem strange or WTF to Western eyes while putting the film in the context of Malian history. And it’s fascinating. Oh, did I mention that it’s about the heroic quest of a young man with magical powers?

youtube

Angels in America, another early video, and one that I cannot watch without crying. Kyle’s words at the end (the closing words of Angels in America) get me every time, as does the sheer disaster that America made of AIDS.

youtube

His entire Summer of Shakespeare series, which I adore. Personal favorites: Omkara and the Indian Shakespeare, about an Indian Othello, Throne of Blood, about a Japanese Macbeth, and 10 Things I Hate About You (a modern retelling of The Taming of the Shrew, which apparently people have been trying to fix since it was written).

To anyone who hasn’t seen his stuff, please check him out. There is so much passion and fascination and attention to detail in Kyle’s work, and I wish he were better known.

As for favorite Shakespeare plays...Macbeth has been my favorite the longest, but @shredsandpatches converted me to love for Richard II. However, I love Shakespeare in general, so it’s hard for me to choose. I feel like, in one respect or another, everything Shakespeare wrote is my favorite.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Toni Morrison Reshaped the Landscape of Literature

Since Toni Morrison, who passed on Monday at 88 years old, was the main dark lady to do some significant things—become a proofreader at Random House and win the Nobel Prize for Literature among them—her work has frequently been seen exclusively through the perspective of personality. That is not off-base, surely; "It's imperative to me that my work be African American," Morrison told the Paris Review in 1993. At Random House, she distributed an astonishing cluster of dark artistic ability, from Gayl Jones and Henry Dumas to Toni Cade Bambara and Angela Davis—who kept in touch with her personal history at Morrison's asking—just as the milestone 1974 compilation of pictures and messages The Black Book. As model and motivation, Morrison prepared for and empowered endless scholars who may somehow or another have felt there was the wrong spot for individuals like them in the pantheon of American writing.

In any case, Toni Morrison was additionally an extraordinary author in manners that will in general get lost when she's being praised for the accomplishments depicted above and, in all honesty, regarded more as a good example than a craftsman. Her art was extensive and smart and progressive. During the 1980s, before her royal celebration as the grande lady of American letters, her books energized perusers. They were a piece of a cornucopia of new work distributed by dark American ladies that drove the skyline of abstract fiction past the overfamiliar and overworshipped domain of Roth, Bellow, Updike, and Mailer. (Perusing Morrison, Jones, Gloria Naylor, and Paule Marshall during the '80s some of the time had a craving for being discharged from a scholarly correctional facility.) Morrison specifically, however, tore open a method of American exposition that had turned out to be dormant and vacillating.

Industry warehouse

This style—how about we call it "Faulknerian," after its other Nobel-winning expert—is exciting and condition thick. Since quite a while ago connected with the South, Faulkner's extraordinary topic, it whirlpools and circles, with a frequently infuriating indirection. The Faulknerian style's weakest imitators just view it as a permit to slather descriptive words and illustrations everywhere throughout the page. Morrison, who abhorred seeing her fiction depicted as "expressive" or "lovely," had a more profound comprehension of Faulkner's stratagems. In her Paris Review meet (an absolute necessity for any appreciator of Morrison's virtuoso), she conveys a splendid analyzation of Absalom, Absalom, a novel that intrigued her: Faulkner, she says, "spends the whole book following race and you can't discover it. Nobody can see it, even the character who is dark can't see it. … Do you realize that it is so difficult to retain that sort of data however implying, pointing constantly? … So the structure is the contention." The curved idea of Faulkner's style encapsulates the deadened state of Southern culture: Everything in it motions toward the one thing it can't force itself to discuss. This Catch 22 gives Faulkner's fiction its capacity, yet for any author looking to emulate his example, it prompts an impasse.

FACTORY SHED

Morrison's three biggest books—Sula, Song of Solomon, and Beloved, all accounts of inception, getaway, and return—exploded that impasse. In her Midwestern hands, the Faulknerian style was renewed, never again gagging without anyone else truth, race and the heritage of subjection never again pushed underneath the surface. What is just suggested, the apparitions witnessed out of the side of the peruser's eye, are the individuals her characters may have been without those curses. Morrison was consistently a wizard at confusion and disclosure, a superior plot-producer than she was ever given kudos for. I read some place, years prior, that she wanted to peruse murder riddles, and that appeared well and good; every Toni Morrison tale is a puzzle of sorts.

What's more, the structure was the contention. Tune of Solomon is a scriptural story running in reverse, moving from the state of a people to the creation legend of a solitary man. Inversions like this are one of Morrison's most brave and powerful story systems. Adored is, obviously, an apparition story, yet one that takes its focal character, the filicidal Sethe, from bound disengagement to network. Furthermore, 1974's Sula—the most loved of numerous long-term Morrison fans and a close flawless novel—fools you into believing it's about the sentimental existences of two youth sweethearts, one "good" and one not, just for the sole overcomer of the pair to acknowledge toward the end that her companion implied more to her than any man. Aircraft Hangars

Those three books specifically reshaped the artistic scene of the 1980s, and not just on the grounds that they delineated what papers like to call "the dark experience" with a phenomenal trustworthiness and closeness. They were stunning combinations of structure and substance. They made moves that no other author of the time, dark or white, endeavored. They joined brazen acting with careful perceptions of quotidian life. They got you alcoholic on their language and gutted you with their savagery. They liberated a specific kind of American voice that had steered into the rocks. They made new conceivable outcomes all of a sudden and magnificently obvious. Toni Morrison got a kick out of the chance to overlook things from her fiction, to give her perusers a chance to make sense of it for themselves. Yet, the absolute last thing that ought to go implicit is the genuine expansiveness of what she has abandoned. Steel Girder

0 notes