#atrabilious

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

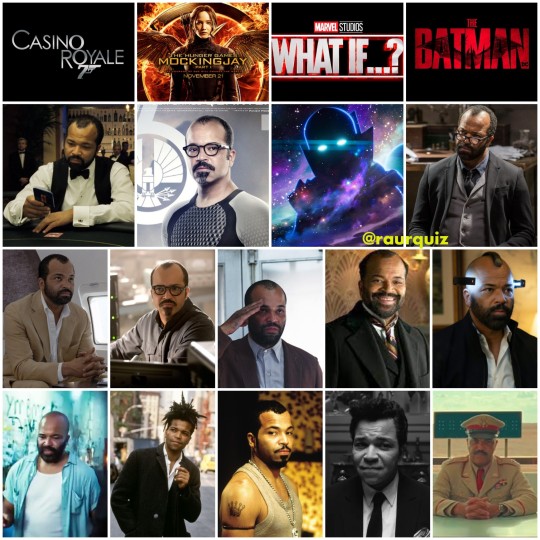

#happybirthday @jfreewright #jeffreywright #actor #Basquiat #Shaft #TheManchurianCandidate #CasinoRoyale #QuantumofSolace #NoTimetoDie #BoardwalkEmpire #WhatIf #iamgroot #TheHungerGames #CatchingFire #Mockingjay #TheLastofUs #AmericanFiction #Rustin #Atrabilious #TheBatman

#happybirthday#jeffrey wright#actor#basquiat#shaft#the manchurian candidate#casino royale#quantumsolace#no time to die#boardwalk empire#what if#i am groot#the hunger games#catching fire#mockingjay#the last of us#american fiction#rustin#atrabilious#the batman

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

a list of "beautiful" words for you

to try to include in your next poem/story

Acrimonious - deeply or violently bitter

Adust - of a gloomy appearance or disposition

Alluvium - clay, silt, sand, gravel, or similar detrital material deposited by running water

Apophenia - the tendency to perceive a connection or meaningful pattern between unrelated or random things (such as objects or ideas)

Asterism - a group of stars that form a pattern in the night sky

Atrabilious - given to or marked by melancholy; gloomy; ill-natured, peevish

Bloodroot - a plant (Sanguinaria canadensis) of the poppy family having a red root and sap and bearing a solitary lobed leaf and white flower in early spring

Camelopard - an archaic word for giraffe

Clairsentience - perception of what it not normally perceptible

Decumbiture - a horoscope calculated at the time of taking to one's sickbed

Fluvial - of, relating to, or living in a stream or river; produced by the action of a stream

Gamboge - also spelled camboge, can be used to describe the vivid yellows of autumn

Grimalkin - a domestic cat—especially an old female one

Hibernaculum - a shelter occupied during the winter by a dormant animal (such as an insect, snake, bat, or marmot)

Monochromatism - complete color blindness in which all colors appear as shades of gray

Mordant - biting and caustic in thought, manner, or style

Offing - the near or foreseeable future

Pareidolia - the tendency to perceive a specific, often meaningful image in a random or ambiguous visual pattern

Riparian - relating to or living or located on the bank of a natural watercourse (such as a river) or sometimes of a lake or a tidewater

Sirocco - a hot desert wind that blows northward from the Sahara toward the Mediterranean coast of Europe; more broadly, it is used for any kind of hot, oppressive wind

Squall - describes a sudden violent wind often accompanied by rain or snow

Stereognosis - ability to perceive or the perception of material qualities (such as shape) of an object by handling or lifting it; tactile recognition

Struthious - of or relating to the ostriches and related birds; and more specifically, ignoring something that needs attention

Susurrous - full of whispering sounds

Synastry - concurrence of starry position or influence upon two persons; similarity of condition or fortune prefigured by astrology

If any of these words make their way into your next poem/story, please tag me, or send me a link. I would love to read them!

More: Lists of Beautiful Words ⚜ More: Word Lists ⚜ Writing Resources PDFs

#beautiful words#writing prompt#word list#writeblr#literature#writers on tumblr#poetry#spilled ink#poets on tumblr#studyblr#langblr#dark academia#light academia#lit#words#writing#linguistics#writing reference#creative writing#writing resources

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

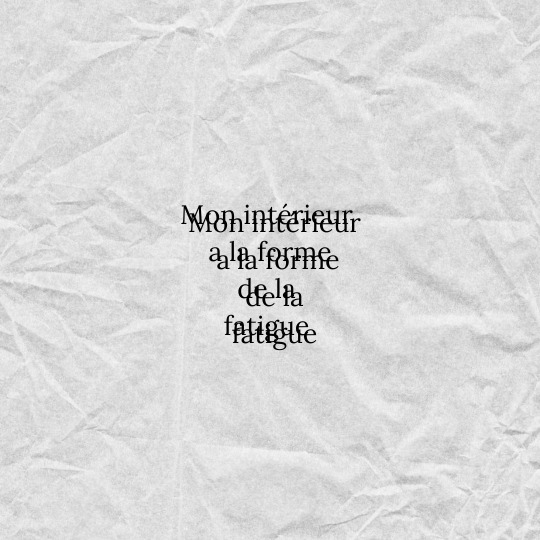

𝐀𝐝𝐮𝐬𝐭

uh-DUSST

1. scorched, seared; burnt up, calcined; dried up with heat, parched. also fig.

2. of colour: brown, as if scorched by fire, or by the sun; sunburnt

3. applied to a supposed state of the body and its humours, much spoken of in the earlier days of medicine, its alleged symptoms being dryness of the body, heat, thirst, black or burnt colour of the blood, and deficiency of serum in it, atrabilious or ‘melancholic’ complexion, etc. Obs. exc. in the general sense, atrabilious, sallow, gloomy in features or temperament (A favorite term of the medieval medical writers in the middle ages)

#dark academia#light academia#litblr#langblr#english language#oxford english dictionary#words#spilled ink#spilled words#beautiful words#writers and poets#writing#creative writing#writeblr#writer#writers on tumblr#writerscommunity#resources for writers#writebrl#writing inspiration#writing advice#writing prompt#writing ideas#writing community#definition#vocabulary#vocab#language

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

CAUCHEMARS -

Atrabilis - 2024

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rare Word Aesthetics

Atrabilious [a-trah-bill-ee-us] (adjective): Chronically gloomy or irritable

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

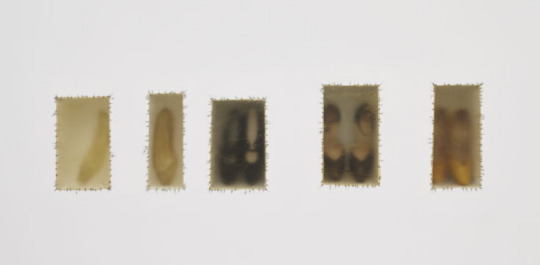

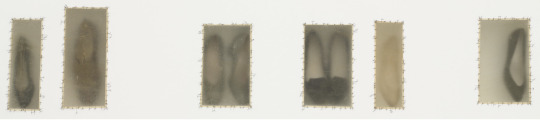

Doris Salcedo

Doris Salcedo, Atrabilious, 1996, Drywall, shoes, cow bladder, and surgical thread, 47 x 83 1/16 inches (119.4 x 211 cm).

Within the cow bladder-like membrane material, worn women’s shoes faintly emerge, inviting viewers to step closer and examine them. Yet the blurred visual effect prevents any clear capture of detail—much like a sealed-off traumatic memory that resists full recollection. The artist uses stitching techniques to preserve the shoes like specimens. While appearing protected, their interiors are slowly decaying—perhaps revealing society’s tendency to conceal the wounds of women harmed by violence.

In Atrabiliarios, the artist pulls viewers directly into the scene of violence through visceral imagery. These old shoes evoke imagined traces of their former wearers—such as the curve of a high heel or the size of a child’s shoe. Where did they walk? Why were the shoes removed? The more ordinary the object, the more it provokes empathy and introspection.

Salcedo, Doris. 1996. “Atrabiliarios.” Institute of Contemporary Art. 1996. https://www.icaboston.org/art/doris-salcedo/atrabiliarios/.

1 note

·

View note

Text

a list of "beautiful" words for march

to try to include in your next poem/story

Atrabilious - given to or marked by melancholy

Berceuse - lullaby

Camaïeu - monochrome

Duvetyn - a smooth lustrous velvety fabric

Epizeuxis - the immediate repetition of a word or phrase for rhetorical or poetic effect

Frescade - a cool walk; shady place

Hypotyposis - vivid picturesque description

Immortelle - everlasting

Jejune - devoid of significance or interest

Kirsch - a dry colorless brandy distilled from the fermented juice of the black morello cherry

Lamiaceous - of or relating to the mint family; minty

Melichrous - of the color honey yellow

Nervure – vein

Obsequies - a funeral or burial rite

Pluviose - marked by or regularly receiving heavy rainfall

Quietism - a state of calmness or passivity

Sempervirent - evergreen

Underbreath - whisper, undertone

Vulnerary - used for or useful in healing wounds

Zythum - beer of ancient times

More: Lists of Beautiful Words ⚜ Word Lists ⚜ Writing Resources PDFs

#march#beautiful words#writeblr#dark academia#writing prompts#spilled ink#linguistics#langblr#studyblr#writers on tumblr#writing prompt#poetry#poets on tumblr#literature#lit#word list#creative writing#fiction#writing reference#light academia#writing resources

474 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝑺 𝑼 𝑩 𝑷 𝑳 𝑶 𝑻 𝑷 𝑹 𝑬 𝑽 𝑰 𝑬 𝑾

𝙵𝙴𝙴𝙳 𝚃𝙷𝙴 𝚁𝙸𝚅𝙴𝚁 trigger warning — illegal substances

Growing in excess along the remote mountains of Aberdeen, P. atrabilious is a hallucinogenic fungus with its earliest known usage on campus dating back to the sixties. The magic mushrooms — colloquially known as ‘psi’ — experienced a short period of circulation at Galloway before it was prohibited under the administration of then Vice Chancellor, Alfred Bray. Now, decades later, ‘psi’ has since been reintroduced to the student body and carefully curated to only affect those with Volition at their disposal While the long-term effects of ‘psi’ remain largely unknown, what toxicology has been documented lists the following adverse effects:

abdominal cramping

cluster headaches

hyperhidrosis

insomnia

nausea and vomiting

paranoia

tremors

𝑪𝑨𝑺𝑻

◍ — —, ## | dealer ◍ — —, ## | dealer ◍ — —, ## | dealer ◍ — —, ## | dealer ◍ — —, ## | dealer ◍ — —, ## | dealer

High above a labyrinth of pointed arches and stained glass windows, a January sun glows bright — a half-formed eye peering through a collage of passing clouds. The sky is painted in shades of eggshell and stone, and the wind blowing in from across Otter Creek is cold and unrepentant, forcing the scholars scattered across Galloway’s acres to turn up the collars on their coats. They move as one — a herd of polyester, faux leather, and cashmere, their hands and faces chapped from the elements, their shoulders ladened with knapsacks and the weight of expectation. The cobbled walkways leading from one stone structure to the next is an endless tide of stiff limbs and rime-slick shoes, and Gregory Reynolds is buoyed along, freckled hands red with cold

His head is bent low against the wind as he schlepps along, desperate to escape the bite of winter. He moves as fast as his legs can carry him, elbows flared outward for added momentum. The Lyceum looms in the distance, its ancient face framed by glittering icicles and tufts of snow. Breaking away from the herd of chattering teeth, Gregory picks his way through puddles that have frozen over and a sizeable mound of snow; he can almost feel the warmth of the foyer against his face and the hard plastic of his assigned seat beneath him, but the mental image is dashed when he comes to a sudden stop

The cold of the salted ground draws an anguished sound from deep within him as he shoves against the weight on top of him. “Oh, shit — my bad.” He leans back onto his elbows and grits his teeth as the student sprawled over his thighs scrambles to their feet and then extends a gloved hand. Gregory hoists himself upward with their help and sweeps the mangled surface of his palms against his damp jeans, another apology fast on his tongue. His words are dismissed with the wave of the student’s hand and then a hastily made peace sign before they shoulder by and disappear into the surging wall of students

Gregory — head bent once more, his cheeks high with the colour of embarrassment — shakes off the collision before something catches his eye; he watches as a shimmering square of plastic is almost crushed underfoot before darting forward to retrieve it. His brows pinch together and then his mouth opens. His studies, he decides, can wait

In the warmth of his dormitory, Gregory breaks the seal on the tiny gold bag; he rolls what appears to be a stem between his thumb and forefinger before consuming it. The minutes tick by with little fanfare and Gregory exhales an exasperated breath. “This shit is garbage,” he mumbles, moving to his feet and reaching for his coat. But then his hand stills and his eyes widen — his fingers multiply in length and number, and a pale light blooms between his knuckles

The room turns onto its side as he steps forward and the door is thrown open into the wall. A jagged line runs through the picture frame mounted on his bedside table. His four-poster levitates

The floor beneath his feet shudders, rising and falling as if a giant breath is being taken. He can hear chatter from all across the campus — a moment of hesitation before a question is asked in a far off classroom, the hushed concern of his housemate in the room over. Gregory is on his knees, nails digging into the floorboards, his head thrown back onto his shoulders

𝑳𝑰𝑴𝑬𝑹𝑬𝑵𝑪𝑬 is an upcoming semi-private dark academia roleplay set in the fictional town of Aberdeen, Vermont. Our tale of 𝐚𝐜𝐚𝐝𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐜 𝐞𝐱𝐜𝐞𝐥𝐥𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞, 𝐜𝐨𝐯𝐞𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐢𝐚𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐬, and 𝐦𝐞𝐭𝐚𝐩𝐡𝐲𝐬𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐫𝐢𝐠𝐮𝐞 takes place on the sprawling grounds of Galloway Academy, but beyond the dignified veneer of gilded bibliotheques and spacious lecture halls, something within the university persists, gorging itself on 𝐏𝐎𝐖𝐄𝐑 and 𝐏𝐑𝐄𝐒𝐓𝐈𝐆𝐄 — on the rot of 𝐇𝐔𝐁𝐑𝐈𝐒

Follow for updates or track the tag “#limerencerp”

#jcink#jcink premium#jcink rp#jcink roleplay#semi-private rp#semi-private roleplay#dark academia rp#dark academia roleplay#mature rp#mature roleplay#limerencerp

0 notes

Text

Doris Salcedo Atrabilious 1992-93

Medium Wall installation with plywood, shoes, cow bladder and surgical thread, six niches Dimensions Overall 30 x 70 1/4 x 5 1/8" (76.2 x 178.4 x 13 cm)

0 notes

Text

0 notes