#asuncion down town

Text

Don't Do This In Asuncion | Paraguay

Don’t Do This In Asuncion | Paraguay

BEST HOTEL DEALS IN ASUNCION

Understanding Asuncion

Asuncion is located in South America’s biggest city. It is home to more than half a million residents. During the weekend the city center is deserted. It is the capital of South America’s biggest city. It is located on the eastern bank of the River Paraguay, near the confluence of the Pilcomayo River and the Occidental Region’s Bay. The city…

View On WordPress

#sebastian asuncion paraguay traval viajes#asunción#asuncion 4k video#asunción attractions#asuncion city tour#asuncion down town#asuncion drew binsky#asuncion paraguay#asuncion paraguay 4k#asuncion top sights#asuncion travel#asuncion travel tour#asuncion vlog#consolid travel#drew binsky asuncion#kara travel#paraguay travel#traveel#travel#travel asuncion#travels#visit asuncion paraguay#what to do in asuncion

0 notes

Text

I want to share something really special that happened tonight that I believe is because of me reaching out and calling on my ancestors for awhile now.

✨✨✨

I’m Mexican American & I’ve always been raised to believe my great-grandma Julieta was the first to immigrate here with her husband Timoteo. My great-grandparents were not open about their family history. I don’t know why, but either way, no one in my family knows about our history. We know we came from Mexico at some point. But that’s it.

I’ve always wanted to know more. Asking family always led to a dead end. Searches online were scarce and difficult to look through. Eventually I figured I’d just never know.

Recently though, I’ve been talking to my ancestors through meditation and ritual, asking them for guidance. Then tonight, I got the urge again to just look. See what I could find. Do some realllyyyy deep digging into my family.

And would you believe it... I found so, so much. My great-grandma was NOT the first to immigrate here in the family. Her grandparents were, aka my great, great, great grandparents. Asuncion & Leonarda. This was huge for me. It means my family has been in the States since sometime between 1890-1910.

But then, I found even more. The Catholic Church had the record of Leonarda’s baptism, and through that I found her father Felipe, and his father Procopio. He was the last person I was able to trace down but it was enough.

In a single night, my Mexican family history went from ~1940s, back to 1830s. I know where my family came from. Not just ‘Mexico’ but their state, their small town they grew up in. I can look up the church on google maps and see where my ancestors were baptized. I know my family has been in the States over 100 years now. I know where I can go visit my great great great grandparents graves.

I cried tonight, no lie. It makes me so emotional to think of all these people who I’ve just been reconnected to. I can’t describe what it means to have a named place where my family comes from. I thanked my ancestors for helping me find this because I truly don’t think I would’ve been able to without reaching out to them all this time. I have so much more I want to learn about them but for tonight this is enough.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

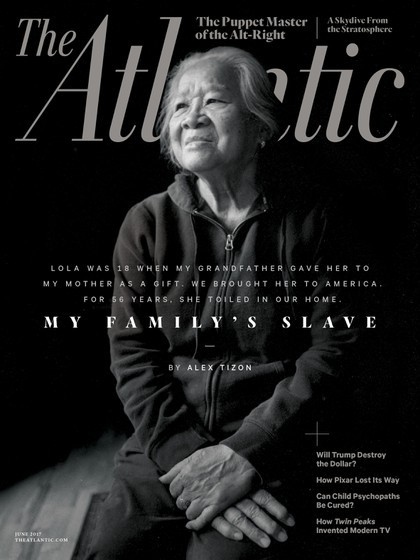

My Family’s Slave

By Alex Tizon

--

The ashes filled a black plastic box about the size of a toaster. It weighed three and a half pounds. I put it in a canvas tote bag and packed it in my suitcase this past July for the transpacific flight to Manila. From there I would travel by car to a rural village. When I arrived, I would hand over all that was left of the woman who had spent 56 years as a slave in my family’s household.

Her name was Eudocia Tomas Pulido. We called her Lola. She was 4 foot 11, with mocha-brown skin and almond eyes that I can still see looking into mine—my first memory. She was 18 years old when my grandfather gave her to my mother as a gift, and when my family moved to the United States, we brought her with us. No other word but slave encompassed the life she lived. Her days began before everyone else woke and ended after we went to bed. She prepared three meals a day, cleaned the house, waited on my parents, and took care of my four siblings and me. My parents never paid her, and they scolded her constantly. She wasn’t kept in leg irons, but she might as well have been. So many nights, on my way to the bathroom, I’d spot her sleeping in a corner, slumped against a mound of laundry, her fingers clutching a garment she was in the middle of folding.

To our American neighbors, we were model immigrants, a poster family. They told us so. My father had a law degree, my mother was on her way to becoming a doctor, and my siblings and I got good grades and always said “please” and “thank you.” We never talked about Lola. Our secret went to the core of who we were and, at least for us kids, who we wanted to be.

After my mother died of leukemia, in 1999, Lola came to live with me in a small town north of Seattle. I had a family, a career, a house in the suburbs—the American dream. And then I had a slave.

At baggage claim in Manila, I unzipped my suitcase to make sure Lola’s ashes were still there. Outside, I inhaled the familiar smell: a thick blend of exhaust and waste, of ocean and sweet fruit and sweat.Early the next morning I found a driver, an affable middle-aged man who went by the nickname “Doods,” and we hit the road in his truck, weaving through traffic. The scene always stunned me. The sheer number of cars and motorcycles and jeepneys. The people weaving between them and moving on the sidewalks in great brown rivers. The street vendors in bare feet trotting alongside cars, hawking cigarettes and cough drops and sacks of boiled peanuts. The child beggars pressing their faces against the windows.

Doods and I were headed to the place where Lola’s story began, up north in the central plains: Tarlac province. Rice country. The home of a cigar-chomping army lieutenant named Tomas Asuncion, my grandfather. The family stories paint Lieutenant Tom as a formidable man given to eccentricity and dark moods, who had lots of land but little money and kept mistresses in separate houses on his property. His wife died giving birth to their only child, my mother. She was raised by a series of utusans, or “people who take commands.”

Slavery has a long history on the islands. Before the Spanish came, islanders enslaved other islanders, usually war captives, criminals, or debtors. Slaves came in different varieties, from warriors who could earn their freedom through valor to household servants who were regarded as property and could be bought and sold or traded. High-status slaves could own low-status slaves, and the low could own the lowliest. Some chose to enter servitude simply to survive: In exchange for their labor, they might be given food, shelter, and protection.

When the Spanish arrived, in the 1500s, they enslaved islanders and later brought African and Indian slaves. The Spanish Crown eventually began phasing out slavery at home and in its colonies, but parts of the Philippines were so far-flung that authorities couldn’t keep a close eye. Traditions persisted under different guises, even after the U.S. took control of the islands in 1898. Today even the poor can have utusans or katulongs (“helpers”) or kasambahays (“domestics”), as long as there are people even poorer. The pool is deep.

Lieutenant Tom had as many as three families of utusans living on his property. In the spring of 1943, with the islands under Japanese occupation, he brought home a girl from a village down the road. She was a cousin from a marginal side of the family, rice farmers. The lieutenant was shrewd—he saw that this girl was penniless, unschooled, and likely to be malleable. Her parents wanted her to marry a pig farmer twice her age, and she was desperately unhappy but had nowhere to go. Tom approached her with an offer: She could have food and shelter if she would commit to taking care of his daughter, who had just turned 12.

Lola agreed, not grasping that the deal was for life.

“She is my gift to you,” Lieutenant Tom told my mother.

“I don’t want her,” my mother said, knowing she had no choice.

Lieutenant Tom went off to fight the Japanese, leaving Mom behind with Lola in his creaky house in the provinces. Lola fed, groomed, and dressed my mother. When they walked to the market, Lola held an umbrella to shield her from the sun. At night, when Lola’s other tasks were done—feeding the dogs, sweeping the floors, folding the laundry that she had washed by hand in the Camiling River—she sat at the edge of my mother’s bed and fanned her to sleep.

One day during the war Lieutenant Tom came home and caught my mother in a lie—something to do with a boy she wasn’t supposed to talk to. Tom, furious, ordered her to “stand at the table.” Mom cowered with Lola in a corner. Then, in a quivering voice, she told her father that Lola would take her punishment. Lola looked at Mom pleadingly, then without a word walked to the dining table and held on to the edge. Tom raised the belt and delivered 12 lashes, punctuating each one with a word. You. Do. Not. Lie. To. Me. You. Do. Not. Lie. To. Me. Lola made no sound.

My mother, in recounting this story late in her life, delighted in the outrageousness of it, her tone seeming to say, Can you believe I did that? When I brought it up with Lola, she asked to hear Mom’s version. She listened intently, eyes lowered, and afterward she looked at me with sadness and said simply, “Yes. It was like that.”

Seven years later, in 1950, Mom married my father and moved to Manila, bringing Lola along. Lieutenant Tom had long been haunted by demons, and in 1951 he silenced them with a .32‑caliber slug to his temple. Mom almost never talked about it. She had his temperament—moody, imperial, secretly fragile—and she took his lessons to heart, among them the proper way to be a provincial matrona: You must embrace your role as the giver of commands. You must keep those beneath you in their place at all times, for their own good and the good of the household. They might cry and complain, but their souls will thank you. They will love you for helping them be what God intended.

My brother Arthur was born in 1951. I came next, followed by three more siblings in rapid succession. My parents expected Lola to be as devoted to us kids as she was to them. While she looked after us, my parents went to school and earned advanced degrees, joining the ranks of so many others with fancy diplomas but no jobs. Then the big break: Dad was offered a job in Foreign Affairs as a commercial analyst. The salary would be meager, but the position was in America—a place he and Mom had grown up dreaming of, where everything they hoped for could come true.

Dad was allowed to bring his family and one domestic. Figuring they would both have to work, my parents needed Lola to care for the kids and the house. My mother informed Lola, and to her great irritation, Lola didn’t immediately acquiesce. Years later Lola told me she was terrified. “It was too far,” she said. “Maybe your Mom and Dad won’t let me go home.”

In the end what convinced Lola was my father’s promise that things would be different in America. He told her that as soon as he and Mom got on their feet, they’d give her an “allowance.” Lola could send money to her parents, to all her relations in the village. Her parents lived in a hut with a dirt floor. Lola could build them a concrete house, could change their lives forever. Imagine.

We landed in Los Angeles on May 12, 1964, all our belongings in cardboard boxes tied with rope. Lola had been with my mother for 21 years by then. In many ways she was more of a parent to me than either my mother or my father. Hers was the first face I saw in the morning and the last one I saw at night. As a baby, I uttered Lola’s name (which I first pronounced “Oh-ah”) long before I learned to say “Mom” or “Dad.” As a toddler, I refused to go to sleep unless Lola was holding me, or at least nearby.

I was 4 years old when we arrived in the U.S.—too young to question Lola’s place in our family. But as my siblings and I grew up on this other shore, we came to see the world differently. The leap across the ocean brought about a leap in consciousness that Mom and Dad couldn’t, or wouldn’t, make.

Lola never got that allowance. She asked my parents about it in a roundabout way a couple of years into our life in America. Her mother had fallen ill (with what I would later learn was dysentery), and her family couldn’t afford the medicine she needed. “Pwede ba?” she said to my parents. Is it possible? Mom let out a sigh. “How could you even ask?,” Dad responded in Tagalog. “You see how hard up we are. Don’t you have any shame?”

My parents had borrowed money for the move to the U.S., and then borrowed more in order to stay. My father was transferred from the consulate general in L.A. to the Philippine consulate in Seattle. He was paid $5,600 a year. He took a second job cleaning trailers, and a third as a debt collector. Mom got work as a technician in a couple of medical labs. We barely saw them, and when we did they were often exhausted and snappish.

Mom would come home and upbraid Lola for not cleaning the house well enough or for forgetting to bring in the mail. “Didn’t I tell you I want the letters here when I come home?” she would say in Tagalog, her voice venomous. “It’s not hard naman! An idiot could remember.” Then my father would arrive and take his turn. When Dad raised his voice, everyone in the house shrank. Sometimes my parents would team up until Lola broke down crying, almost as though that was their goal.

It confused me: My parents were good to my siblings and me, and we loved them. But they’d be affectionate to us kids one moment and vile to Lola the next. I was 11 or 12 when I began to see Lola’s situation clearly. By then Arthur, eight years my senior, had been seething for a long time. He was the one who introduced the word slave into my understanding of what Lola was. Before he said it I’d thought of her as just an unfortunate member of the household. I hated when my parents yelled at her, but it hadn’t occurred to me that they—and the whole arrangement—could be immoral.

“Do you know anybody treated the way she’s treated?,” Arthur said. “Who lives the way she lives?” He summed up Lola’s reality: Wasn’t paid. Toiled every day. Was tongue-lashed for sitting too long or falling asleep too early. Was struck for talking back. Wore hand-me-downs. Ate scraps and leftovers by herself in the kitchen. Rarely left the house. Had no friends or hobbies outside the family. Had no private quarters. (Her designated place to sleep in each house we lived in was always whatever was left—a couch or storage area or corner in my sisters’ bedroom. She often slept among piles of laundry.)

We couldn’t identify a parallel anywhere except in slave characters on TV and in the movies. I remember watching a Western called The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. John Wayne plays Tom Doniphon, a gunslinging rancher who barks orders at his servant, Pompey, whom he calls his “boy.” Pick him up, Pompey. Pompey, go find the doctor. Get on back to work, Pompey! Docile and obedient, Pompey calls his master “Mistah Tom.” They have a complex relationship. Tom forbids Pompey from attending school but opens the way for Pompey to drink in a whites-only saloon. Near the end, Pompey saves his master from a fire. It’s clear Pompey both fears and loves Tom, and he mourns when Tom dies. All of this is peripheral to the main story of Tom’s showdown with bad guy Liberty Valance, but I couldn’t take my eyes off Pompey. I remember thinking: Lola is Pompey, Pompey is Lola.

One night when Dad found out that my sister Ling, who was then 9, had missed dinner, he barked at Lola for being lazy. “I tried to feed her,” Lola said, as Dad stood over her and glared. Her feeble defense only made him angrier, and he punched her just below the shoulder. Lola ran out of the room and I could hear her wailing, an animal cry.

“Ling said she wasn’t hungry,” I said.

My parents turned to look at me. They seemed startled. I felt the twitching in my face that usually preceded tears, but I wouldn’t cry this time. In Mom’s eyes was a shadow of something I hadn’t seen before. Jealousy?

“Are you defending your Lola?,” Dad said. “Is that what you’re doing?”

“Ling said she wasn’t hungry,” I said again, almost in a whisper.

I was 13. It was my first attempt to stick up for the woman who spent her days watching over me. The woman who used to hum Tagalog melodies as she rocked me to sleep, and when I got older would dress and feed me and walk me to school in the mornings and pick me up in the afternoons. Once, when I was sick for a long time and too weak to eat, she chewed my food for me and put the small pieces in my mouth to swallow. One summer when I had plaster casts on both legs (I had problem joints), she bathed me with a washcloth, brought medicine in the middle of the night, and helped me through months of rehabilitation. I was cranky through it all. She didn’t complain or lose patience, ever.

To now hear her wailing made me crazy.

In the old country, my parents felt no need to hide their treatment of Lola. In America, they treated her worse but took pains to conceal it. When guests came over, my parents would either ignore her or, if questioned, lie and quickly change the subject. For five years in North Seattle, we lived across the street from the Misslers, a rambunctious family of eight who introduced us to things like mustard, salmon fishing, and mowing the lawn. Football on TV. Yelling during football. Lola would come out to serve food and drinks during games, and my parents would smile and thank her before she quickly disappeared. “Who’s that little lady you keep in the kitchen?,” Big Jim, the Missler patriarch, once asked. A relative from back home, Dad said. Very shy.

Billy Missler, my best friend, didn’t buy it. He spent enough time at our house, whole weekends sometimes, to catch glimpses of my family’s secret. He once overheard my mother yelling in the kitchen, and when he barged in to investigate found Mom red-faced and glaring at Lola, who was quaking in a corner. I came in a few seconds later. The look on Billy’s face was a mix of embarrassment and perplexity. What was that? I waved it off and told him to forget it.

I think Billy felt sorry for Lola. He’d rave about her cooking, and make her laugh like I’d never seen. During sleepovers, she’d make his favorite Filipino dish, beef tapa over white rice. Cooking was Lola’s only eloquence. I could tell by what she served whether she was merely feeding us or saying she loved us.

When I once referred to Lola as a distant aunt, Billy reminded me that when we’d first met I’d said she was my grandmother.

“Well, she’s kind of both,” I said mysteriously.

“Why is she always working?”

“She likes to work,” I said.

“Your dad and mom—why do they yell at her?”

“Her hearing isn’t so good …”

Admitting the truth would have meant exposing us all. We spent our first decade in the country learning the ways of the new land and trying to fit in. Having a slave did not fit. Having a slave gave me grave doubts about what kind of people we were, what kind of place we came from. Whether we deserved to be accepted. I was ashamed of it all, including my complicity. Didn’t I eat the food she cooked, and wear the clothes she washed and ironed and hung in the closet? But losing her would have been devastating.

There was another reason for secrecy: Lola’s travel papers had expired in 1969, five years after we arrived in the U.S. She’d come on a special passport linked to my father’s job. After a series of fallings-out with his superiors, Dad quit the consulate and declared his intent to stay in the United States. He arranged for permanent-resident status for his family, but Lola wasn’t eligible. He was supposed to send her back.

Lola’s mother, Fermina, died in 1973; her father, Hilario, in 1979. Both times she wanted desperately to go home. Both times my parents said “Sorry.” No money, no time. The kids needed her. My parents also feared for themselves, they admitted to me later. If the authorities had found out about Lola, as they surely would have if she’d tried to leave, my parents could have gotten into trouble, possibly even been deported. They couldn’t risk it. Lola’s legal status became what Filipinos call tago nang tago, or TNT—“on the run.” She stayed TNT for almost 20 years.

After each of her parents died, Lola was sullen and silent for months. She barely responded when my parents badgered her. But the badgering never let up. Lola kept her head down and did her work.

My father’s resignation started a turbulent period. Money got tighter, and my parents turned on each other. They uprooted the family again and again—Seattle to Honolulu back to Seattle to the southeast Bronx and finally to the truck-stop town of Umatilla, Oregon, population 750. During all this moving around, Mom often worked 24-hour shifts, first as a medical intern and then as a resident, and Dad would disappear for days, working odd jobs but also (we’d later learn) womanizing and who knows what else. Once, he came home and told us that he’d lost our new station wagon playing blackjack.

For days in a row Lola would be the only adult in the house. She got to know the details of our lives in a way that my parents never had the mental space for. We brought friends home, and she’d listen to us talk about school and girls and boys and whatever else was on our minds. Just from conversations she overheard, she could list the first name of every girl I had a crush on from sixth grade through high school.

When I was 15, Dad left the family for good. I didn’t want to believe it at the time, but the fact was that he deserted us kids and abandoned Mom after 25 years of marriage. She wouldn’t become a licensed physician for another year, and her specialty—internal medicine—wasn’t especially lucrative. Dad didn’t pay child support, so money was always a struggle.

My mom kept herself together enough to go to work, but at night she’d crumble in self-pity and despair. Her main source of comfort during this time: Lola. As Mom snapped at her over small things, Lola attended to her even more—cooking Mom’s favorite meals, cleaning her bedroom with extra care. I’d find the two of them late at night at the kitchen counter, griping and telling stories about Dad, sometimes laughing wickedly, other times working themselves into a fury over his transgressions. They barely noticed us kids flitting in and out.

One night I heard Mom weeping and ran into the living room to find her slumped in Lola’s arms. Lola was talking softly to her, the way she used to with my siblings and me when we were young. I lingered, then went back to my room, scared for my mom and awed by Lola.

Doods was humming. I’d dozed for what felt like a minute and awoke to his happy melody. “Two hours more,” he said. I checked the plastic box in the tote bag by my side—still there—and looked up to see open road. The MacArthur Highway. I glanced at the time. “Hey, you said ‘two hours’ two hours ago,” I said. Doods just hummed.

His not knowing anything about the purpose of my journey was a relief. I had enough interior dialogue going on. I was no better than my parents. I could have done more to free Lola. To make her life better. Why didn’t I? I could have turned in my parents, I suppose. It would have blown up my family in an instant. Instead, my siblings and I kept everything to ourselves, and rather than blowing up in an instant, my family broke apart slowly.

Doods and I passed through beautiful country. Not travel-brochure beautiful but real and alive and, compared with the city, elegantly spare. Mountains ran parallel to the highway on each side, the Zambales Mountains to the west, the Sierra Madre Range to the east. From ridge to ridge, west to east, I could see every shade of green all the way to almost black.

Doods pointed to a shadowy outline in the distance. Mount Pinatubo. I’d come here in 1991 to report on the aftermath of its eruption, the second-largest of the 20th century. Volcanic mudflows called lahars continued for more than a decade, burying ancient villages, filling in rivers and valleys, and wiping out entire ecosystems. The lahars reached deep into the foothills of Tarlac province, where Lola’s parents had spent their entire lives, and where she and my mother had once lived together. So much of our family record had been lost in wars and floods, and now parts were buried under 20 feet of mud.

Life here is routinely visited by cataclysm. Killer typhoons that strike several times a year. Bandit insurgencies that never end. Somnolent mountains that one day decide to wake up. The Philippines isn’t like China or Brazil, whose mass might absorb the trauma. This is a nation of scattered rocks in the sea. When disaster hits, the place goes under for a while. Then it resurfaces and life proceeds, and you can behold a scene like the one Doods and I were driving through, and the simple fact that it’s still there makes it beautiful.

A couple of years after my parents split, my mother remarried and demanded Lola’s fealty to her new husband, a Croatian immigrant named Ivan, whom she had met through a friend. Ivan had never finished high school. He’d been married four times and was an inveterate gambler who enjoyed being supported by my mother and attended to by Lola.

Ivan brought out a side of Lola I’d never seen. His marriage to my mother was volatile from the start, and money—especially his use of her money—was the main issue. Once, during an argument in which Mom was crying and Ivan was yelling, Lola walked over and stood between them. She turned to Ivan and firmly said his name. He looked at Lola, blinked, and sat down.

My sister Inday and I were floored. Ivan was about 250 pounds, and his baritone could shake the walls. Lola put him in his place with a single word. I saw this happen a few other times, but for the most part Lola served Ivan unquestioningly, just as Mom wanted her to. I had a hard time watching Lola vassalize herself to another person, especially someone like Ivan. But what set the stage for my blowup with Mom was something more mundane.

She used to get angry whenever Lola felt ill. She didn’t want to deal with the disruption and the expense, and would accuse Lola of faking or failing to take care of herself. Mom chose the second tack when, in the late 1970s, Lola’s teeth started falling out. She’d been saying for months that her mouth hurt.

“That’s what happens when you don’t brush properly,” Mom told her.

I said that Lola needed to see a dentist. She was in her 50s and had never been to one. I was attending college an hour away, and I brought it up again and again on my frequent trips home. A year went by, then two. Lola took aspirin every day for the pain, and her teeth looked like a crumbling Stonehenge. One night, after watching her chew bread on the side of her mouth that still had a few good molars, I lost it.

Mom and I argued into the night, each of us sobbing at different points. She said she was tired of working her fingers to the bone supporting everybody, and sick of her children always taking Lola’s side, and why didn’t we just take our goddamn Lola, she’d never wanted her in the first place, and she wished to God she hadn’t given birth to an arrogant, sanctimonious phony like me.

I let her words sink in. Then I came back at her, saying she would know all about being a phony, her whole life was a masquerade, and if she stopped feeling sorry for herself for one minute she’d see that Lola could barely eat because her goddamn teeth were rotting out of her goddamn head, and couldn’t she think of her just this once as a real person instead of a slave kept alive to serve her?

“A slave,” Mom said, weighing the word. “A slave?”

The night ended when she declared that I would never understand her relationship with Lola. Never. Her voice was so guttural and pained that thinking of it even now, so many years later, feels like a punch to the stomach. It’s a terrible thing to hate your own mother, and that night I did. The look in her eyes made clear that she felt the same way about me.

The fight only fed Mom’s fear that Lola had stolen the kids from her, and she made Lola pay for it. Mom drove her harder. Tormented her by saying, “I hope you’re happy now that your kids hate me.” When we helped Lola with housework, Mom would fume. “You’d better go to sleep now, Lola,” she’d say sarcastically. “You’ve been working too hard. Your kids are worried about you.” Later she’d take Lola into a bedroom for a talk, and Lola would walk out with puffy eyes.

Lola finally begged us to stop trying to help her.

Why do you stay? we asked.

“Who will cook?” she said, which I took to mean, Who would do everything? Who would take care of us? Of Mom? Another time she said, “Where will I go?” This struck me as closer to a real answer. Coming to America had been a mad dash, and before we caught a breath a decade had gone by. We turned around, and a second decade was closing out. Lola’s hair had turned gray. She’d heard that relatives back home who hadn’t received the promised support were wondering what had happened to her. She was ashamed to return.

She had no contacts in America, and no facility for getting around. Phones puzzled her. Mechanical things—ATMs, intercoms, vending machines, anything with a keyboard—made her panic. Fast-talking people left her speechless, and her own broken English did the same to them. She couldn’t make an appointment, arrange a trip, fill out a form, or order a meal without help.

I got Lola an ATM card linked to my bank account and taught her how to use it. She succeeded once, but the second time she got flustered, and she never tried again. She kept the card because she considered it a gift from me.

I also tried to teach her to drive. She dismissed the idea with a wave of her hand, but I picked her up and carried her to the car and planted her in the driver’s seat, both of us laughing. I spent 20 minutes going over the controls and gauges. Her eyes went from mirthful to terrified. When I turned on the ignition and the dashboard lit up, she was out of the car and in the house before I could say another word. I tried a couple more times.

I thought driving could change her life. She could go places. And if things ever got unbearable with Mom, she could drive away forever.

Four lanes became two, pavement turned to gravel. Tricycle drivers wove between cars and water buffalo pulling loads of bamboo. An occasional dog or goat sprinted across the road in front of our truck, almost grazing the bumper. Doods never eased up. Whatever didn’t make it across would be stew today instead of tomorrow—the rule of the road in the provinces.

I took out a map and traced the route to the village of Mayantoc, our destination. Out the window, in the distance, tiny figures folded at the waist like so many bent nails. People harvesting rice, the same way they had for thousands of years. We were getting close.

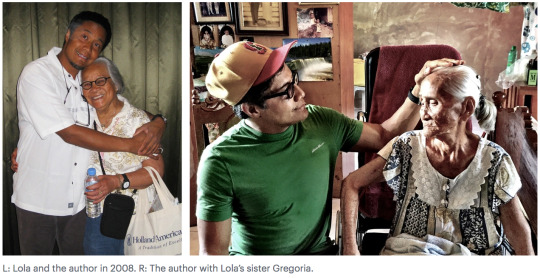

I tapped the cheap plastic box and regretted not buying a real urn, made of porcelain or rosewood. What would Lola’s people think? Not that many were left. Only one sibling remained in the area, Gregoria, 98 years old, and I was told her memory was failing. Relatives said that whenever she heard Lola’s name, she’d burst out crying and then quickly forget why.

I’d been in touch with one of Lola’s nieces. She had the day planned: When I arrived, a low-key memorial, then a prayer, followed by the lowering of the ashes into a plot at the Mayantoc Eternal Bliss Memorial Park. It had been five years since Lola died, but I hadn’t yet said the final goodbye that I knew was about to happen. All day I had been feeling intense grief and resisting the urge to let it out, not wanting to wail in front of Doods. More than the shame I felt for the way my family had treated Lola, more than my anxiety about how her relatives in Mayantoc would treat me, I felt the terrible heaviness of losing her, as if she had died only the day before.

Doods veered northwest on the Romulo Highway, then took a sharp left at Camiling, the town Mom and Lieutenant Tom came from. Two lanes became one, then gravel turned to dirt. The path ran along the Camiling River, clusters of bamboo houses off to the side, green hills ahead. The homestretch.

I gave the eulogy at Mom’s funeral, and everything I said was true. That she was brave and spirited. That she’d drawn some short straws, but had done the best she could. That she was radiant when she was happy. That she adored her children, and gave us a real home—in Salem, Oregon—that through the ’80s and ’90s became the permanent base we’d never had before. That I wished we could thank her one more time. That we all loved her.

I didn’t talk about Lola. Just as I had selectively blocked Lola out of my mind when I was with Mom during her last years. Loving my mother required that kind of mental surgery. It was the only way we could be mother and son—which I wanted, especially after her health started to decline, in the mid‑’90s. Diabetes. Breast cancer. Acute myelogenous leukemia, a fast-growing cancer of the blood and bone marrow. She went from robust to frail seemingly overnight.

After the big fight, I mostly avoided going home, and at age 23 I moved to Seattle. When I did visit I saw a change. Mom was still Mom, but not as relentlessly. She got Lola a fine set of dentures and let her have her own bedroom. She cooperated when my siblings and I set out to change Lola’s TNT status. Ronald Reagan’s landmark immigration bill of 1986 made millions of illegal immigrants eligible for amnesty. It was a long process, but Lola became a citizen in October 1998, four months after my mother was diagnosed with leukemia. Mom lived another year.

During that time, she and Ivan took trips to Lincoln City, on the Oregon coast, and sometimes brought Lola along. Lola loved the ocean. On the other side were the islands she dreamed of returning to. And Lola was never happier than when Mom relaxed around her. An afternoon at the coast or just 15 minutes in the kitchen reminiscing about the old days in the province, and Lola would seem to forget years of torment.

I couldn’t forget so easily. But I did come to see Mom in a different light. Before she died, she gave me her journals, two steamer trunks’ full. Leafing through them as she slept a few feet away, I glimpsed slices of her life that I’d refused to see for years. She’d gone to medical school when not many women did. She’d come to America and fought for respect as both a woman and an immigrant physician. She’d worked for two decades at Fairview Training Center, in Salem, a state institution for the developmentally disabled. The irony: She tended to underdogs most of her professional life. They worshipped her. Female colleagues became close friends. They did silly, girly things together—shoe shopping, throwing dress-up parties at one another’s homes, exchanging gag gifts like penis-shaped soaps and calendars of half-naked men, all while laughing hysterically. Looking through their party pictures reminded me that Mom had a life and an identity apart from the family and Lola. Of course.

Mom wrote in great detail about each of her kids, and how she felt about us on a given day—proud or loving or resentful. And she devoted volumes to her husbands, trying to grasp them as complex characters in her story. We were all persons of consequence. Lola was incidental. When she was mentioned at all, she was a bit character in someone else’s story. “Lola walked my beloved Alex to his new school this morning. I hope he makes new friends quickly so he doesn’t feel so sad about moving again …” There might be two more pages about me, and no other mention of Lola.

The day before Mom died, a Catholic priest came to the house to perform last rites. Lola sat next to my mother’s bed, holding a cup with a straw, poised to raise it to Mom’s mouth. She had become extra attentive to my mother, and extra kind. She could have taken advantage of Mom in her feebleness, even exacted revenge, but she did the opposite.

The priest asked Mom whether there was anything she wanted to forgive or be forgiven for. She scanned the room with heavy-lidded eyes, said nothing. Then, without looking at Lola, she reached over and placed an open hand on her head. She didn’t say a word.

Lola was 75 when she came to stay with me. I was married with two young daughters, living in a cozy house on a wooded lot. From the second story, we could see Puget Sound. We gave Lola a bedroom and license to do whatever she wanted: sleep in, watch soaps, do nothing all day. She could relax���and be free—for the first time in her life. I should have known it wouldn’t be that simple.

I’d forgotten about all the things Lola did that drove me a little crazy. She was always telling me to put on a sweater so I wouldn’t catch a cold (I was in my 40s). She groused incessantly about Dad and Ivan: My father was lazy, Ivan was a leech. I learned to tune her out. Harder to ignore was her fanatical thriftiness. She threw nothing out. And she used to go through the trash to make sure that the rest of us hadn’t thrown out anything useful. She washed and reused paper towels again and again until they disintegrated in her hands. (No one else would go near them.) The kitchen became glutted with grocery bags, yogurt containers, and pickle jars, and parts of our house turned into storage for—there’s no other word for it—garbage.

She cooked breakfast even though none of us ate more than a banana or a granola bar in the morning, usually while we were running out the door. She made our beds and did our laundry. She cleaned the house. I found myself saying to her, nicely at first, “Lola, you don’t have to do that.” “Lola, we’ll do it ourselves.” “Lola, that’s the girls’ job.” Okay, she’d say, but keep right on doing it.

It irritated me to catch her eating meals standing in the kitchen, or see her tense up and start cleaning when I walked into the room. One day, after several months, I sat her down.

“I’m not Dad. You’re not a slave here,” I said, and went through a long list of slavelike things she’d been doing. When I realized she was startled, I took a deep breath and cupped her face, that elfin face now looking at me searchingly. I kissed her forehead. “This is your house now,” I said. “You’re not here to serve us. You can relax, okay?”

“Okay,” she said. And went back to cleaning.

She didn’t know any other way to be. I realized I had to take my own advice and relax. If she wanted to make dinner, let her. Thank her and do the dishes. I had to remind myself constantly: Let her be.

One night I came home to find her sitting on the couch doing a word puzzle, her feet up, the TV on. Next to her, a cup of tea. She glanced at me, smiled sheepishly with those perfect white dentures, and went back to the puzzle. Progress, I thought.

She planted a garden in the backyard—roses and tulips and every kind of orchid—and spent whole afternoons tending it. She took walks around the neighborhood. At about 80, her arthritis got bad and she began walking with a cane. In the kitchen she went from being a fry cook to a kind of artisanal chef who created only when the spirit moved her. She made lavish meals and grinned with pleasure as we devoured them.

Passing the door of Lola’s bedroom, I’d often hear her listening to a cassette of Filipino folk songs. The same tape over and over. I knew she’d been sending almost all her money—my wife and I gave her $200 a week—to relatives back home. One afternoon, I found her sitting on the back deck gazing at a snapshot someone had sent of her village.

“You want to go home, Lola?”

She turned the photograph over and traced her finger across the inscription, then flipped it back and seemed to study a single detail.

“Yes,” she said.

Just after her 83rd birthday, I paid her airfare to go home. I’d follow a month later to bring her back to the U.S.—if she wanted to return. The unspoken purpose of her trip was to see whether the place she had spent so many years longing for could still feel like home.

She found her answer.

“Everything was not the same,” she told me as we walked around Mayantoc. The old farms were gone. Her house was gone. Her parents and most of her siblings were gone. Childhood friends, the ones still alive, were like strangers. It was nice to see them, but … everything was not the same. She’d still like to spend her last years here, she said, but she wasn’t ready yet.

“You’re ready to go back to your garden,” I said.

“Yes. Let’s go home.”

Lola was as devoted to my daughters as she’d been to my siblings and me when we were young. After school, she’d listen to their stories and make them something to eat. And unlike my wife and me (especially me), Lola enjoyed every minute of every school event and performance. She couldn’t get enough of them. She sat up front, kept the programs as mementos.

It was so easy to make Lola happy. We took her on family vacations, but she was as excited to go to the farmer’s market down the hill. She became a wide-eyed kid on a field trip: “Look at those zucchinis!” The first thing she did every morning was open all the blinds in the house, and at each window she’d pause to look outside.

And she taught herself to read. It was remarkable. Over the years, she’d somehow learned to sound out letters. She did those puzzles where you find and circle words within a block of letters. Her room had stacks of word-puzzle booklets, thousands of words circled in pencil. Every day she watched the news and listened for words she recognized. She triangulated them with words in the newspaper, and figured out the meanings. She came to read the paper every day, front to back. Dad used to say she was simple. I wondered what she could have been if, instead of working the rice fields at age 8, she had learned to read and write.

During the 12 years she lived in our house, I asked her questions about herself, trying to piece together her life story, a habit she found curious. To my inquiries she would often respond first with “Why?” Why did I want to know about her childhood? About how she met Lieutenant Tom?

I tried to get my sister Ling to ask Lola about her love life, thinking Lola would be more comfortable with her. Ling cackled, which was her way of saying I was on my own. One day, while Lola and I were putting away groceries, I just blurted it out: “Lola, have you ever been romantic with anyone?” She smiled, and then she told me the story of the only time she’d come close. She was about 15, and there was a handsome boy named Pedro from a nearby farm. For several months they harvested rice together side by side. One time, she dropped her bolo—a cutting implement—and he quickly picked it up and handed it back to her. “I liked him,” she said.

Silence.

“And?”

“Then he moved away,” she said.

“And?”

“That’s all.”

“Lola, have you ever had sex?,” I heard myself saying.

“No,” she said.

She wasn’t accustomed to being asked personal questions. “Katulong lang ako,” she’d say. I’m only a servant. She often gave one- or two-word answers, and teasing out even the simplest story was a game of 20 questions that could last days or weeks.

Some of what I learned: She was mad at Mom for being so cruel all those years, but she nevertheless missed her. Sometimes, when Lola was young, she’d felt so lonely that all she could do was cry. I knew there were years when she’d dreamed of being with a man. I saw it in the way she wrapped herself around one large pillow at night. But what she told me in her old age was that living with Mom’s husbands made her think being alone wasn’t so bad. She didn’t miss those two at all. Maybe her life would have been better if she’d stayed in Mayantoc, gotten married, and had a family like her siblings. But maybe it would have been worse. Two younger sisters, Francisca and Zepriana, got sick and died. A brother, Claudio, was killed. What’s the point of wondering about it now? she asked. Bahala na was her guiding principle. Come what may. What came her way was another kind of family. In that family, she had eight children: Mom, my four siblings and me, and now my two daughters. The eight of us, she said, made her life worth living.

None of us was prepared for her to die so suddenly.

Her heart attack started in the kitchen while she was making dinner and I was running an errand. When I returned she was in the middle of it. A couple of hours later at the hospital, before I could grasp what was happening, she was gone—10:56 p.m. All the kids and grandkids noted, but were unsure how to take, that she died on November 7, the same day as Mom. Twelve years apart.

Lola made it to 86. I can still see her on the gurney. I remember looking at the medics standing above this brown woman no bigger than a child and thinking that they had no idea of the life she had lived. She’d had none of the self-serving ambition that drives most of us, and her willingness to give up everything for the people around her won her our love and utter loyalty. She’s become a hallowed figure in my extended family.

Going through her boxes in the attic took me months. I found recipes she had cut out of magazines in the 1970s for when she would someday learn to read. Photo albums with pictures of my mom. Awards my siblings and I had won from grade school on, most of which we had thrown away and she had “saved.” I almost lost it one night when at the bottom of a box I found a stack of yellowed newspaper articles I’d written and long ago forgotten about. She couldn’t read back then, but she’d kept them anyway.

Doods’s truck pulled up to a small concrete house in the middle of a cluster of homes mostly made of bamboo and plank wood. Surrounding the pod of houses: rice fields, green and seemingly endless. Before I even got out of the truck, people started coming outside.

Doods reclined his seat to take a nap. I hung my tote bag on my shoulder, took a breath, and opened the door.

“This way,” a soft voice said, and I was led up a short walkway to the concrete house. Following close behind was a line of about 20 people, young and old, but mostly old. Once we were all inside, they sat down on chairs and benches arranged along the walls, leaving the middle of the room empty except for me. I remained standing, waiting to meet my host. It was a small room, and dark. People glanced at me expectantly.“

Where is Lola?” A voice from another room. The next moment, a middle-aged woman in a housedress sauntered in with a smile. Ebia, Lola’s niece. This was her house. She gave me a hug and said again, “Where is Lola?”

I slid the tote bag from my shoulder and handed it to her. She looked into my face, still smiling, gently grasped the bag, and walked over to a wooden bench and sat down. She reached inside and pulled out the box and looked at every side. “Where is Lola?” she said softly. People in these parts don’t often get their loved ones cremated. I don’t think she knew what to expect. She set the box on her lap and bent over so her forehead rested on top of it, and at first I thought she was laughing (out of joy) but I quickly realized she was crying. Her shoulders began to heave, and then she was wailing—a deep, mournful, animal howl, like I once heard coming from Lola.

I hadn’t come sooner to deliver Lola’s ashes in part because I wasn’t sure anyone here cared that much about her. I hadn’t expected this kind of grief. Before I could comfort Ebia, a woman walked in from the kitchen and wrapped her arms around her, and then she began wailing. The next thing I knew, the room erupted with sound. The old people—one of them blind, several with no teeth—were all crying and not holding anything back. It lasted about 10 minutes. I was so fascinated that I barely noticed the tears running down my own face. The sobs died down, and then it was quiet again.

Ebia sniffled and said it was time to eat. Everybody started filing into the kitchen, puffy-eyed but suddenly lighter and ready to tell stories. I glanced at the empty tote bag on the bench, and knew it was right to bring Lola back to the place where she’d been born.

----------

Alex Tizon was a Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist and the author of Big Little Man: In Search of My Asian Self. This article originally appeared in the June 2017 issue of The Atlantic and needless to say it was difficult to hold back the tears while reading this incredibly moving piece.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Interesting Facts About Paraguay

Interesting Facts About Paraguay

The water, trees, clouds, and ocean are just some of the natural treasures we have on this planet. Paraguay is a landlocked mass of land and country between Brazil, Bolivia, and Argentina. Much of the land is swampland and tropical forest. You probably can find a jaguar or two in there along with hummingbirds, toucans, and other creatures TBH. The capital is Asuncion and it is on the Paraguay River. As of 2018 the population was just under 7 Million.

The climate in Paraguay is one of the most intriguing countries in South America. It is also one of the most important because of its mineral wealth. It also provides fertile land and an easy migration route to neighboring Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay. Because of the climate and the topography, natural disasters like floods, drought and earthquakes affect the Paraguayan population especially during the rainy season.

Due to its diverse population, language and geography, Paraguay has the most diverse native language in the world. English is the most common native language of Paraguay, while Spanish, Tagalog, Lao, Creole, Lingala, Brazilian Portuguese and Haitivian are the indigenous languages. Most schools teach these languages in primary, middle and high school as part of the curriculum. This is in addition to the Latin American, English and other European languages which are commonly used in everyday life. While not many people in Paraguay speak English, there are a large number of foreigners living in the country.

Paraguay Food

When you consider what to eat in Paraguay, it can be tricky to narrow it down. With a variety of cuisines from Brazilian, Spanish, Peruvian, Cuban, and North American favorites, it can seem almost impossible to find one meal that satisfies all your cravings for variety. Fortunately, we are here to help. After researching the top meals and foods in Paraguay, we have put together a list of our favorite dishes from the country. In this article, we will examine the top 5 meals and foods in Paraguay. These foods are how the people get their protein, potassium, salt, magnesium, turmeric, cinnamon, and more for the day to day diet and living.

While we were conducting our research, we saw that many of the culinary tours to the country would end up visiting one of the old trade markets in the capital of Asuncion. This is one of the must-see attractions in the country, and there is a reason why. The Market offers a great deal of local Paraguayan food, with a wide variety of Paraguayan fare and a few that has made it over to Brazil. Its food is hearty and is typically prepared on flat-top charcoal. On the way out of the market, we stopped for a coffee at a little cafe that sells world-famous coffee beans. Their coffee was so good that we ordered another one as soon as we returned to the hotel.

Some of the top meals and foods in Paraguay include ethanol, which is a spicy soup made with beef and peppers. It is served cold and has a distinctive chile sauce. There is also a dish called mejiche, which is a bread pudding of pig's feet, served in a clay container. Lastly, churrasco, which means stew or broth, is also a popular South American dish. Its distinctive aroma, sweet and rich flavor, and high nutritional value make it very popular in the country. The last dish on our list is guinea pig with fried plantains and rice. These are our top five Paraguayan meals and foods.

Because the infrastructure is very poor, most of the communications in Paraguay is through the mail system. It is possible to send letters or postcards across the country by using the postal service, with small offices called barramundis situated outside major cities. The majority of the population in Paraguay also has cell phones. Citizens do have some technology and internet, but the rate of penetration is not like that in the U.S. or South Korea or even Peru. Folks can access things like Youtube and Facebook, but it is not commonplace yet.

Almost all families have two or three phones. It is important to keep in mind that communication in Paraguay is done mostly through the mail. This means that almost everyone uses the mail to receive and send packages, newspapers, magazines and other printed material. People use this method of communication primarily for social reasons, because people tend to keep their personal items in the house.

It is amazing that this tiny South American country has emerged as one of the best tourist destinations in the world. As the capital city, it is considered as the "New Capital of South America" by the local authorities. The University of Chicago published research on the history of monetary and fiscal policy in Paraguay.

As for the size of geography, Paraguay is a tiny territory that is divided into two regions - north and south. A peculiarity of the North and South districts is that they are not connected with each other. The people who live in both the districts are basically scattered throughout the country.

Due to its small size, there are not so many tourists visiting Paraguay and hence the huge cities like Santa Cruz are very crowded. There are huge number of flights that connect Brazil and Paraguay. The majority of the flights are coming from Brazil, which is also the main destination of Paraguay's tourism.

Another important fact about Paraguay is that the people here are very polite and courteous. Travelers from Europe and the United States come here to explore the beauty of the country. These tourists have experienced the culture of the country through the colorful festivals and the indigenous dances. The people here are very fond of visiting ancient cities such as Manizales and other intriguing places.

A third important fact about Paraguay is that it is considered as one of the richest and most vibrant countries in South America. There is money and some residents even dabble with Bitcoin and Tezos. There are many well-known and prosperous cities that are home to some of the most progressive entrepreneurs and industries. You can get information about the major industries in the country through the local websites and news channels. Some of the key industry sectors include mining, textiles, food processing, electronics, machinery, automobile manufacturing, plastics, chemicals, forestry, construction, engineering, etc. All these industries are home to many big companies, which are supplying products to many countries all over the world.

Among the interesting facts about Paraguay, you will come across that this country was founded by Spanish adventurers in 1531. The Englishman Roger Williams was among the pioneers of the colony.

One of the most interesting facts about Paraguay is that this is one of the last three remaining indigenous nations that were formerly recognized by the United Nations. This has made Paraguay a member of the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR). The country is also one of the few Latin American countries that did not secede from the United Nations after the American War of Independence.

Another interesting fact about Paraguay is that the unique event that happened in this country was known as the San Borja disaster. This was a very major disaster that took place in the city of San Borja, the capital of Paraguay. The flood of the river Guarengu resulted in the death of thousands of people.

Apart from its cities, Paraguay also has several mountains that are dotted with some of the finest resorts and urban development centers. Among the amazing features of the country, you will also find the Fazenda del Paraguay that is situated near the city of the same name. There are also some picturesque towns like Villa Todos Santos, Manizales, and Manizales.

The tourism industry in Paraguay has blossomed, but it is the hospitality sector that has led the way. Many famous companies are based in the country, including Amharic Airlines, Domino Sugar, Abitibi-Monsieur de l'Ouest, Tierra y Mercado, REA Foods, and Tim Hortons.

One of the most popular things about Paraguay is the absence of the prevalence of guns. Instead, the population has become much more aware of firearms due to the continuous existence of some of the deadliest forest fires in the world.

As a result of this aspect, Paraguay has also emerged as a destination for vacationers. In case you are planning your next trip to Paraguay, read more about the most important fact about Paraguay!

https://youtu.be/8wbNEJjBa0k

https://youtu.be/0OCmMPVAc8o

Read the full article

0 notes

Link

https://getpocket.com/explore/item/my-family-s-slave?utm_source=pocket-newtab

This article was originally published on May 16, 2017, by The Atlantic, and is republished at https://getpocket.com/explore/item/my-family-s-slave?utm_source=pocket-newtab with permission. That is where this blogger viewed it on September 14, 2019 and shared it on Tumblr.com.

Pocket Worthy·

Stories to fuel your mind.

My Family’s Slave

She lived with us for 56 years. She raised me and my siblings without pay. I was 11, a typical American kid, before I realized who she was.

The Atlantic | Alex Tizon

All photos courtesy of Alex Tizon and his family.

The ashes filled a black plastic box about the size of a toaster. It weighed three and a half pounds. I put it in a canvas tote bag and packed it in my suitcase this past July for the transpacific flight to Manila. From there I would travel by car to a rural village. When I arrived, I would hand over all that was left of the woman who had spent 56 years as a slave in my family’s household.

Her name was Eudocia Tomas Pulido. We called her Lola. She was 4 foot 11, with mocha-brown skin and almond eyes that I can still see looking into mine—my first memory. She was 18 years old when my grandfather gave her to my mother as a gift, and when my family moved to the United States, we brought her with us. No other word but slave encompassed the life she lived. Her days began before everyone else woke and ended after we went to bed. She prepared three meals a day, cleaned the house, waited on my parents, and took care of my four siblings and me. My parents never paid her, and they scolded her constantly. She wasn’t kept in leg irons, but she might as well have been. So many nights, on my way to the bathroom, I’d spot her sleeping in a corner, slumped against a mound of laundry, her fingers clutching a garment she was in the middle of folding.

To our American neighbors, we were model immigrants, a poster family. They told us so. My father had a law degree, my mother was on her way to becoming a doctor, and my siblings and I got good grades and always said “please” and “thank you.” We never talked about Lola. Our secret went to the core of who we were and, at least for us kids, who we wanted to be.

After my mother died of leukemia, in 1999, Lola came to live with me in a small town north of Seattle. I had a family, a career, a house in the suburbs—the American dream. And then I had a slave.

***

At baggage claim in Manila, I unzipped my suitcase to make sure Lola’s ashes were still there. Outside, I inhaled the familiar smell: a thick blend of exhaust and waste, of ocean and sweet fruit and sweat.

Early the next morning I found a driver, an affable middle-aged man who went by the nickname “Doods,” and we hit the road in his truck, weaving through traffic. The scene always stunned me. The sheer number of cars and motorcycles and jeepneys. The people weaving between them and moving on the sidewalks in great brown rivers. The street vendors in bare feet trotting alongside cars, hawking cigarettes and cough drops and sacks of boiled peanuts. The child beggars pressing their faces against the windows.

Doods and I were headed to the place where Lola’s story began, up north in the central plains: Tarlac province. Rice country. The home of a cigar-chomping army lieutenant named Tomas Asuncion, my grandfather. The family stories paint Lieutenant Tom as a formidable man given to eccentricity and dark moods, who had lots of land but little money and kept mistresses in separate houses on his property. His wife died giving birth to their only child, my mother. She was raised by a series of utusans, or “people who take commands.”

Slavery has a long history on the islands. Before the Spanish came, islanders enslaved other islanders, usually war captives, criminals, or debtors. Slaves came in different varieties, from warriors who could earn their freedom through valor to household servants who were regarded as property and could be bought and sold or traded. High-status slaves could own low-status slaves, and the low could own the lowliest. Some chose to enter servitude simply to survive: In exchange for their labor, they might be given food, shelter, and protection.

When the Spanish arrived, in the 1500s, they enslaved islanders and later brought African and Indian slaves. The Spanish Crown eventually began phasing out slavery at home and in its colonies, but parts of the Philippines were so far-flung that authorities couldn’t keep a close eye. Traditions persisted under different guises, even after the U.S. took control of the islands in 1898. Today even the poor can have utusans or katulongs (“helpers”) or kasambahays (“domestics”), as long as there are people even poorer. The pool is deep.

Lieutenant Tom had as many as three families of utusans living on his property. In the spring of 1943, with the islands under Japanese occupation, he brought home a girl from a village down the road. She was a cousin from a marginal side of the family, rice farmers. The lieutenant was shrewd—he saw that this girl was penniless, unschooled, and likely to be malleable. Her parents wanted her to marry a pig farmer twice her age, and she was desperately unhappy but had nowhere to go. Tom approached her with an offer: She could have food and shelter if she would commit to taking care of his daughter, who had just turned 12.

Lola agreed, not grasping that the deal was for life.

“She is my gift to you,” Lieutenant Tom told my mother.

“I don’t want her,” my mother said, knowing she had no choice.

Lieutenant Tom went off to fight the Japanese, leaving Mom behind with Lola in his creaky house in the provinces. Lola fed, groomed, and dressed my mother. When they walked to the market, Lola held an umbrella to shield her from the sun. At night, when Lola’s other tasks were done—feeding the dogs, sweeping the floors, folding the laundry that she had washed by hand in the Camiling River—she sat at the edge of my mother’s bed and fanned her to sleep.

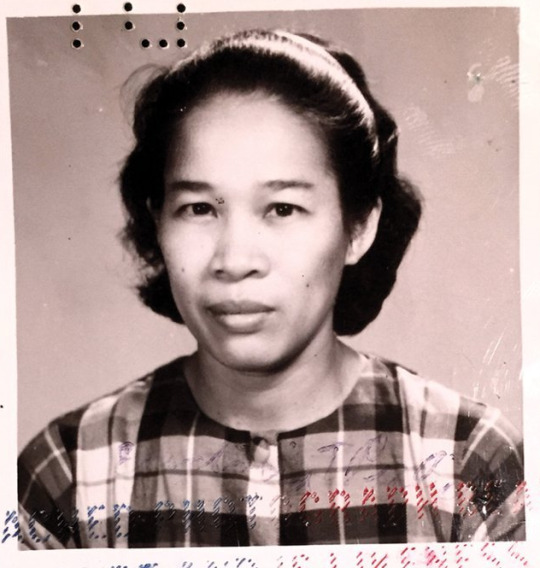

Lola Pulido (shown on the left at age 18) came from a poor family in a rural part of the Philippines. The author’s grandfather “gave” her to his daughter as a gift.

One day during the war Lieutenant Tom came home and caught my mother in a lie—something to do with a boy she wasn’t supposed to talk to. Tom, furious, ordered her to “stand at the table.” Mom cowered with Lola in a corner. Then, in a quivering voice, she told her father that Lola would take her punishment. Lola looked at Mom pleadingly, then without a word walked to the dining table and held on to the edge. Tom raised the belt and delivered 12 lashes, punctuating each one with a word. You. Do. Not. Lie. To. Me. You. Do. Not. Lie. To. Me. Lola made no sound.

My mother, in recounting this story late in her life, delighted in the outrageousness of it, her tone seeming to say, Can you believe I did that? When I brought it up with Lola, she asked to hear Mom’s version. She listened intently, eyes lowered, and afterward, she looked at me with sadness and said simply, “Yes. It was like that.”

Seven years later, in 1950, Mom married my father and moved to Manila, bringing Lola along. Lieutenant Tom had long been haunted by demons, and in 1951 he silenced them with a .32‑caliber slug to his temple. Mom almost never talked about it. She had his temperament—moody, imperial, secretly fragile—and she took his lessons to heart, among them the proper way to be a provincial matrona: You must embrace your role as the giver of commands. You must keep those beneath you in their place at all times, for their own good and the good of the household. They might cry and complain, but their souls will thank you. They will love you for helping them be what God intended.

Lola at age 27 with Arthur, the author’s older brother, before coming to the U.S.

My brother Arthur was born in 1951. I came next, followed by three more siblings in rapid succession. My parents expected Lola to be as devoted to us kids as she was to them. While she looked after us, my parents went to school and earned advanced degrees, joining the ranks of so many others with fancy diplomas but no jobs. Then the big break: Dad was offered a job in Foreign Affairs as a commercial analyst. The salary would be meager, but the position was in America—a place he and Mom had grown up dreaming of, where everything they hoped for could come true.

Dad was allowed to bring his family and one domestic. Figuring they would both have to work, my parents needed Lola to care for the kids and the house. My mother informed Lola, and to her great irritation, Lola didn’t immediately acquiesce. Years later Lola told me she was terrified. “It was too far,” she said. “Maybe your Mom and Dad won’t let me go home.”

In the end what convinced Lola was my father’s promise that things would be different in America. He told her that as soon as he and Mom got on their feet, they’d give her an “allowance.” Lola could send money to her parents, to all her relations in the village. Her parents lived in a hut with a dirt floor. Lola could build them a concrete house, could change their lives forever. Imagine.

We landed in Los Angeles on May 12, 1964, all our belongings in cardboard boxes tied with rope. Lola had been with my mother for 21 years by then. In many ways she was more of a parent to me than either my mother or my father. Hers was the first face I saw in the morning and the last one I saw at night. As a baby, I uttered Lola’s name (which I first pronounced “Oh-ah”) long before I learned to say “Mom” or “Dad.” As a toddler, I refused to go to sleep unless Lola was holding me, or at least nearby.

I was 4 years old when we arrived in the U.S.—too young to question Lola’s place in our family. But as my siblings and I grew up on this other shore, we came to see the world differently. The leap across the ocean brought about a leap in consciousness that Mom and Dad couldn’t, or wouldn’t, make.

***

Lola never got that allowance. She asked my parents about it in a roundabout way a couple of years into our life in America. Her mother had fallen ill (with what I would later learn was dysentery), and her family couldn’t afford the medicine she needed. “Pwede ba?” she said to my parents. Is it possible? Mom let out a sigh. “How could you even ask?,” Dad responded in Tagalog. “You see how hard up we are. Don’t you have any shame?”

My parents had borrowed money for the move to the U.S. and then borrowed more in order to stay. My father was transferred from the consulate general in L.A. to the Philippine consulate in Seattle. He was paid $5,600 a year. He took a second job cleaning trailers, and a third as a debt collector. Mom got work as a technician in a couple of medical labs. We barely saw them, and when we did they were often exhausted and snappish.

Mom would come home and upbraid Lola for not cleaning the house well enough or for forgetting to bring in the mail. “Didn’t I tell you I want the letters here when I come home?” she would say in Tagalog, her voice venomous. “It’s not hard naman! An idiot could remember.” Then my father would arrive and take his turn. When Dad raised his voice, everyone in the house shrank. Sometimes my parents would team up until Lola broke down crying, almost as though that was their goal.

It confused me: My parents were good to my siblings and me, and we loved them. But they’d be affectionate to us kids one moment and vile to Lola the next. I was 11 or 12 when I began to see Lola’s situation clearly. By then Arthur, eight years my senior, had been seething for a long time. He was the one who introduced the word slave into my understanding of what Lola was. Before he said it I’d thought of her as just an unfortunate member of the household. I hated when my parents yelled at her, but it hadn’t occurred to me that they—and the whole arrangement—could be immoral.

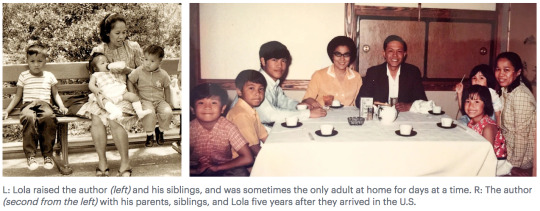

L: Lola raised the author (left) and his siblings and was sometimes the only adult at home for days at a time. R: The author (second from the left) with his parents, siblings, and Lola five years after they arrived in the U.S.

“Do you know anybody treated the way she’s treated?” Arthur said. “Who lives the way she lives?” He summed up Lola’s reality: Wasn’t paid. Toiled every day. Was tongue-lashed for sitting too long or falling asleep too early. Was struck for talking back. Wore hand-me-downs. Ate scraps and leftovers by herself in the kitchen. Rarely left the house. Had no friends or hobbies outside the family. Had no private quarters. (Her designated place to sleep in each house we lived in was always whatever was left—a couch or storage area or corner in my sisters’ bedroom. She often slept among piles of laundry.)

We couldn’t identify a parallel anywhere except in slave characters on TV and in the movies. I remember watching a Western called The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. John Wayne plays Tom Doniphon, a gunslinging rancher who barks orders at his servant, Pompey, whom he calls his “boy.” Pick him up, Pompey. Pompey, go find the doctor. Get on back to work, Pompey! Docile and obedient, Pompey calls his master “Mistah Tom.” They have a complex relationship. Tom forbids Pompey from attending school but opens the way for Pompey to drink in a whites-only saloon. Near the end, Pompey saves his master from a fire. It’s clear Pompey both fears and loves Tom, and he mourns when Tom dies. All of this is peripheral to the main story of Tom’s showdown with bad guy Liberty Valance, but I couldn’t take my eyes off Pompey. I remember thinking: Lola is Pompey, Pompey is Lola.

One night when Dad found out that my sister Ling, who was then 9, had missed dinner, he barked at Lola for being lazy. “I tried to feed her,” Lola said, as Dad stood over her and glared. Her feeble defense only made him angrier, and he punched her just below the shoulder. Lola ran out of the room and I could hear her wailing, an animal cry.

“Ling said she wasn’t hungry,” I said.

My parents turned to look at me. They seemed startled. I felt the twitching in my face that usually preceded tears, but I wouldn’t cry this time. In Mom’s eyes was a shadow of something I hadn’t seen before. Jealousy?

“Are you defending your Lola?,” Dad said. “Is that what you’re doing?”

“Ling said she wasn’t hungry,” I said again, almost in a whisper.

I was 13. It was my first attempt to stick up for the woman who spent her days watching over me. The woman who used to hum Tagalog melodies as she rocked me to sleep, and when I got older would dress and feed me and walk me to school in the mornings and pick me up in the afternoons. Once, when I was sick for a long time and too weak to eat, she chewed my food for me and put the small pieces in my mouth to swallow. One summer when I had plaster casts on both legs (I had problem joints), she bathed me with a washcloth, brought medicine in the middle of the night, and helped me through months of rehabilitation. I was cranky through it all. She didn’t complain or lose patience, ever.

To now hear her wailing made me crazy.

***

In the old country, my parents felt no need to hide their treatment of Lola. In America, they treated her worse but took pains to conceal it. When guests came over, my parents would either ignore her or, if questioned, lie and quickly change the subject. For five years in North Seattle, we lived across the street from the Missler's, a rambunctious family of eight who introduced us to things like mustard, salmon fishing, and mowing the lawn. Football on TV. Yelling during football. Lola would come out to serve food and drinks during games, and my parents would smile and thank her before she quickly disappeared. “Who’s that little lady you keep in the kitchen?,” Big Jim, the Missler patriarch, once asked. A relative from back home, Dad said. Very shy.

Billy Missler, my best friend, didn’t buy it. He spent enough time at our house, whole weekends sometimes, to catch glimpses of my family’s secret. He once overheard my mother yelling in the kitchen, and when he barged in to investigate found Mom red-faced and glaring at Lola, who was quaking in a corner. I came in a few seconds later. The look on Billy’s face was a mix of embarrassment and perplexity. What was that? I waved it off and told him to forget it.

I think Billy felt sorry for Lola. He’d rave about her cooking, and make her laugh like I’d never seen. During sleepovers, she’d make his favorite Filipino dish, beef tapa over white rice. Cooking was Lola’s only eloquence. I could tell by what she served whether she was merely feeding us or saying she loved us.

When I once referred to Lola as a distant aunt, Billy reminded me that when we’d first met I’d said she was my grandmother.

“Well, she’s kind of both,” I said mysteriously.

“Why is she always working?”

“She likes to work,” I said.

“Your dad and mom—why do they yell at her?”

“Her hearing isn’t so good …”

Admitting the truth would have meant exposing us all. We spent our first decade in the country learning the ways of the new land and trying to fit in. Having a slave did not fit. Having a slave gave me grave doubts about what kind of people we were, what kind of place we came from. Whether we deserved to be accepted. I was ashamed of it all, including my complicity. Didn’t I eat the food she cooked, and wear the clothes she washed and ironed and hung in the closet? But losing her would have been devastating.

There was another reason for secrecy: Lola’s travel papers had expired in 1969, five years after we arrived in the U.S. She’d come on a special passport linked to my father’s job. After a series of fallings-out with his superiors, Dad quit the consulate and declared his intent to stay in the United States. He arranged for permanent-resident status for his family, but Lola wasn’t eligible. He was supposed to send her back.

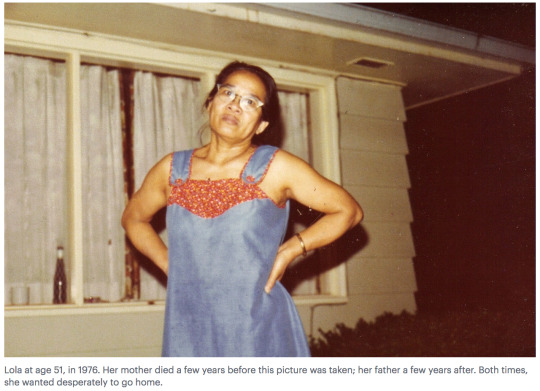

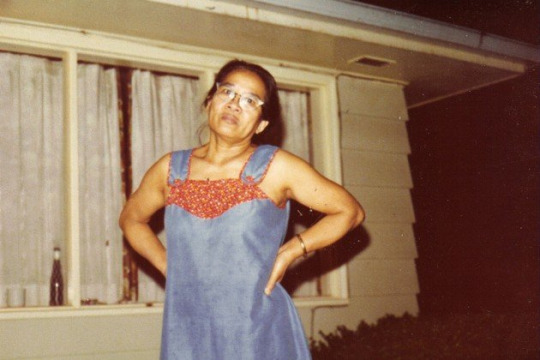

Lola at age 51, in 1976. Her mother died a few years before this picture was taken; her father a few years after. Both times, she wanted desperately to go home.

Lola’s mother, Fermina, died in 1973; her father, Hilario, in 1979. Both times she wanted desperately to go home. Both times my parents said “Sorry.” No money, no time. The kids needed her. My parents also feared for themselves, they admitted to me later. If the authorities had found out about Lola, as they surely would have if she’d tried to leave, my parents could have gotten into trouble, possibly even been deported. They couldn’t risk it. Lola’s legal status became what Filipinos call tago nang tago, or TNT—“on the run.” She stayed TNT for almost 20 years.

After each of her parents died, Lola was sullen and silent for months. She barely responded when my parents badgered her. But the badgering never let up. Lola kept her head down and did her work.

***

My father’s resignation started a turbulent period. Money got tighter, and my parents turned on each other. They uprooted the family again and again—Seattle to Honolulu back to Seattle to the southeast Bronx and finally to the truck-stop town of Umatilla, Oregon, population 750. During all this moving around, Mom often worked 24-hour shifts, first as a medical intern and then as a resident, and Dad would disappear for days, working odd jobs but also (we’d later learn) womanizing and who knows what else. Once, he came home and told us that he’d lost our new station wagon playing blackjack.

For days in a row, Lola would be the only adult in the house. She got to know the details of our lives in a way that my parents never had the mental space for. We brought friends home, and she’d listen to us talk about school and girls and boys and whatever else was on our minds. Just from conversations she overheard, she could list the first name of every girl I had a crush on from sixth grade through high school.

When I was 15, Dad left the family for good. I didn’t want to believe it at the time, but the fact was that he deserted us kids and abandoned Mom after 25 years of marriage. She wouldn’t become a licensed physician for another year, and her specialty—internal medicine—wasn’t especially lucrative. Dad didn’t pay child support, so money was always a struggle.

My mom kept herself together enough to go to work, but at night she’d crumble in self-pity and despair. Her main source of comfort during this time: Lola. As Mom snapped at her over small things, Lola attended to her even more—cooking Mom’s favorite meals, cleaning her bedroom with extra care. I’d find the two of them late at night at the kitchen counter, griping and telling stories about Dad, sometimes laughing wickedly, other times working themselves into a fury over his transgressions. They barely noticed us kids flitting in and out.

One night I heard Mom weeping and ran into the living room to find her slumped in Lola’s arms. Lola was talking softly to her, the way she used to with my siblings and me when we were young. I lingered, then went back to my room, scared for my mom and awed by Lola.

***

Doods was humming. I’d dozed for what felt like a minute and awoke to his happy melody. “Two hours more,” he said. I checked the plastic box in the tote bag by my side—still there—and looked up to see open road. The MacArthur Highway. I glanced at the time. “Hey, you said ‘two hours’ two hours ago,” I said. Doods just hummed.