#as in a male perspective denies her interiority

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Blanche DuBois is not at all a Good Person but i'll be damned before i let her be percieved entirely through a male perspective

#.txt#ascnd#as in a male perspective denies her interiority#which she HAS in the text of the play!! this isnt a jordan baker revisionist interpretation THIS IS KEY TO THE PLAY#blanche dubois#eng lit#pls ignore this im thinking out loud

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

© Claire Mathon

Translated interview with Director Sciamma

‘We started a culture war‘

Andreas Busche and Nadine Lange, in: Der Tagesspiegel, 29th of October 2019

Additions or clarifications for translating purposes are denoted as [T: …]

Manifest on the female gaze: Céline Sciamma speaks about her period film ‘Portrait of a Lady on Fire’, MeToo in France and queer visibility.

In France, Céline Sciamma, born in 1978, is already revered as the new feminist and notably queer voice of French cinema, in the tradition of Claire Denis and Catherine Breillat. The director (‘Tomboy’, ‘Girlhood’), who writes her own screenplays, is largely unknown in [T: Germany]. This is most likely about to change with her fourth and most beautiful feature film so far. At the Cannes Film Festival, the period love story between the young painter Marianne and her model Héloïse, daughter of French aristocrats, won the Best Screenplay. Between the rugged landscape of the coast of Brittany and the candlelit interiors of an old villa, the film creates a utopia of solidarity and female desire, in which the characters of Marianne, Héloïse and Sophie the maid overcome class barriers.

Interviewers: Ms Sciamma, ‘Portrait of a Lady on Fire’ is your first period film, it takes place a few years before the French Revolution. Why is this era important for your story?

Céline Sciamma: My interest in those years came from art history. At the time, there was an unusual number of female painters, hundreds in France and across Europe. It really moved me to discover the biographies of these women, who had successful careers. They supported each other and were very political. There was for example feminist art criticism at the time.

I: Noémie Merlant plays the painter Marianne, who is commissioned to do a portrait of Héloïse, a daughter of aristocrats. There are two main themes: the representation of female painters in bourgeois society and the female gaze – and how this [T: gaze] is reflected in the art world at the time. How are these themes connected?

CS: When I went into more detail about the work of female painters in the late 18th century, I realised how much the female perspective is missing from art history. For me this is the most painful loss, which results from the elimination of the female gaze: this relates to the artwork themselves, but also to what art brings to our lives, the memory of a kind of intimacy.

I: Marianne is not based on a specific female painter. But is she representative of women at the time?

CS: I collaborated with an art sociologist, who did extensive research on this era. All biographical details for Marianne correspond to the time in which she lived. The dynamics of a biopic – a successful woman who defies societal norms – never really interested me. My film is a manifest on the female gaze. But there’s also melancholy in this process, because we have to restore something that has been ignored for a long time.

I: Why melancholy?

CS: It makes me sad, because this perspective was withheld from me all my life. That is why the scene, where Marianne, Héloïse and Sophie the maid re-enact an abortion, is so important for the film. By painting an abortion, the act becomes art and is therefore represented. Art gives women the opportunity to tell their own stories. But it’s not only about the past. The topic of abortion is still virtually invisible in cinema.

I: How do you deal with this lack of female perspectives as a screenwriter and director?

CS: I was aware about the lack of queer and lesbian representation in cinema early on. But it becomes dangerous, when we don’t realise anymore that something is withheld from us. I noticed this again, when I watched ‘Wonder Woman’ by Patty Jenkins. It is hard to express how you feel when you know you’re not represented, and at the same time are oblivious to the power it can give you to recognise yourself in cinema. That was a new experience for me.

I: You were one of the initiators of the 50/50 by 2020 movement, which is committed to gender parity at festivals and in film. What do you expect from Cannes next year?

CS: I’m glad that this topic is finally taken seriously. We set out our target for Cannes and want more transparency in the selection committee. However, to achieve these, you have to introduce quota. The board will be replaced [T: next] year, let’s see how it works. We started a culture war. One of the most important things for me is the work on inclusion. The 50/50 [T: movement] and the film production/promotion agency CNC created a fund for cultural diversity in [T: film] productions last year. There’s usually less budget for films made by female directors, this inequality will be slightly mitigated. More than 20 films have already benefitted from this fund.

I: There is progress on one hand, but on the other hand some things are deteriorating again. Do you see it in a similar way?

CS: We had no MeToo-debate in France, unlike the one in the US. The [T: debate] was quickly hijacked and reinterpreted as discussion about free speech: that feminist film criticism would lead to a new form of censorship. You could feel the backlash in France. A good example: Sandra Muller, who created the French MeToo movement ‘Balance ton Porc’ [T: ‘Denounce your pig’, see here for the evolution of the term ‘pig’ in this context] just lost a libel lawsuit. Action was filed by the man, whose harassing statements she made public. The level of societal discourse is not where it’s supposed to be.

I: You lead by example: There are mainly women working on your sets.

CS: It creates a different atmosphere, that is for sure. But I’ll tell you something: Women only make up 50% of the crew, my crew is probably one of the most diverse in France. Claire Mathon is my cinematographer, but a lot of men work with her. My cutter is a man though. It’s about the right balance. The film world is very much dominated by men, but I don’t want to exclude anyone.

I: In Cannes, you said something similar about your colleague Abdellatif Kechiche, who was criticised for his voyeuristic gaze on women, for example in the Palm d’Or winner ‘Blue is the Warmest Colour’. Do you want a cinema, in which your and his gaze can exist side by side?

CS: We have to be conscious about our perspective. In France, I’m always asked about my female gaze, but no one is ever asking a [T: male] filmmaker about his male gaze. Which is still considered as gender neutral. Of course, you can love ‘Blue is the Warmest Colour’ as much as you love ‘Portrait of a Lady on Fire’ [T: 😈], otherwise cinema will become a battlefield of ideologies. We just have to learn to read the images correctly. I would like to invite Abdellatif Kechiche to this relatively new discourse. But he should be asked the same questions as me.

I: You call ‘Portrait of a Lady on Fire’ a manifest on the female gaze. What does that mean?

CS: It starts with the screenplay. I wanted to tell a love story on equal terms. There is no gender-specific power imbalance in the film. That was important for me, especially in a time, in which gender inequality was the social norm. There is also no intellectual dominance between Marianne and Héloïse, they both come from the upper class, are sophisticated and self-determined. Between them, they did not have to negotiate a status.

I: What role did your actresses play in this?

CS: I wrote the film for Adèle Haenel. But it only works if she has a partner who is equal to her. Noémie Merlant is about the same age as Adèle, they are even the same height, which cannot be underestimated in cinema. That’s why shorter actors often have to stand on a pedestal. All these considerations are political, but they are also an offer to the audience: for new emotions, for surprises. Equality creates freedom, because social rules are overturned.

I: As Marianne, Héloïse and Sophie keep to themselves, they are not exposed to the male gaze. They can move freely.

CS: That’s why I don’t think of my film as social utopia. Every utopia is based on our experiences and ideas. You cannot easily find this kind of solidarity among women, you have to create this freedom. That’s why I decided to exclude male characters. What I exclude from the shot also defines what is shown in the picture. That’s the power of cinema.

I: Your film is about the visibility of women. They tell each other, how they see one another – and thus create an image of themselves. At the same time, desire arises from their gazes. How do you create this feeling of intimacy?

CS: We offer a philosophy and politics of love. Even the depiction of queer sexuality in cinema is based on heterosexual paradigms. We first had to learn how to deconstruct this gaze on us. Similarly, it’s also about abolishing the outdated ideal of the muse. There is of course a hierarchy on set, but we tried to transfer the working relationships in the film to our shooting.

I: All your films have queer aspects. Do you ever had any problems to fund your films?

CS: No, but that’s because I don’t need so much money. ‘Portrait of a Lady on Fire’ did cost 4 Million Euros. If I had asked for 12 Million Euros, it might have been different. I can’t complain. I live in a country, in which I can make these kinds of films and be radical. 23 percent of French films are made by female directors.

I: It seems like there were more [T: female directors] recently?

CS: No, the figure has been constant for 20 years. We are just forgotten and then ‘rediscovered’. Think about Alice Guy-Blanché, who made films at the time of Méliès [T: around the turn of last century]. She did everything by herself, used the first closeup. She literally co-invented the cinema. But like all the women, who were active at the beginning of film history, they were driven out, when it was suddenly about money.

Still from ‘Be natural: The Untold Story of Alice Guy-Blaché’ (Pamela B. Green, 2018)

#Céline Sciamma#Der Tagesspiegel#2019#Portrait of a Lady on Fire#German interview#Manifest on the FEMALE GAZE#Nope on Blue is the Warmest Colour#Alice Guy-Blaché#Cinema#My translation#long post

129 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Chalk One Up” | Directed by Seith Mann, Cinematography by David Klein

The episode opens with Carrie arriving from a long night out doing… God knows what with God knows who. We love the starkness of this close-up on the exterminated motorcycle light. According to Lesli Linka Glatter, this mode of transport is based on a real life story:

“The scene where she gets out of the embassy was based on the real agent who Carrie is based on. She was based in Iraq at the time and that’s how she got out: by dressing as a man and traveling on a motorcycle. So, we used that for this. Also, you can’t leave in Kabul without an armored vehicle.”

...as the camera slowly pans up to reveal it’s Carrie underneath that (gigantor) motorcycle helmet, the question becomes clear: where the fuck was she?

Sara loved these scenes between Samira and her friend. Homeland has depicted several cities in the Middle East over the years but has rarely given us glimpses into the world outside the walls of a hotel or CIA station, especially without our main characters. The market that Samira and her friend walk through is vibrant and filled with color, as are their outfits. It’s a stark contrast to the interiors of the CIA station. And Samira’s line that the Taliban didn’t go away but were no longer hiding proves remarkably predictive of the rest of the episode’s events.

The real highlight of the scene is the selfie, of course. We love the detail of the man on the far, far left being cut out. Samira’s friend is the master of the one-arm selfie!

This shot of the various players at the Kabul station looking outward at Carrie is striking. It’s almost a reverse fish bowl. Carrie remains on the outside but everyone’s looks are in her direction. Jenna standing at the front of the room further suggests she was never “stuck in the starting gate.” She’s in the same position of power in that room as the Chief of Station and the commanding military officer at right. From afar, the dynamics are almost similar to early season one, Carrie running an ops meeting with Saul by her side. All of which is to say… is Jenna the Carrie to Mike’s Saul?

Dog.

This was such a specific detail that we thought it required pointing out, but 27 is not a significant number on this show (at least that we can remember), so we’re not sure why they bothered to show this.

...unless it’s a reference to the general ominousness of the 27 Club and a hint that Carrie (who, to be fair, is far past the age of 27) is going to die.

This week the show confirmed that Tasneem is the Director of the ISI. Which means that (after President Elizabeth Keane) she’s the second most powerful woman ever depicted on this show. And boy does she dress the part!

Tasneem’s all-white ensemble is attention-grabbing and distinctive (the other women in this frame are dressed in dark clothes). It’s also visually similar--especially with her long, black hair peeking through the sheer fabric of her headscarf--to the dress worn by several other men at the reception.

Homeland has told lots of stories over the years--whether intentional or otherwise--about the challenges women face living in a patriarchal, misogynist society. Whether it’s Martha losing her career because her loser husband couldn’t stand having a wife who was more powerful and smarter than he…. Or Allison dying in the back of a car near the Russian border in an act of scorned lover revenge. Or Carrie, screaming and crying at the end of “The Vest”... but being right the whole time.

Or, as Abigail Nussbaum said more elegantly than we ever could:

“Carrie is, in many ways, a boogeyman; she is what professional women, and particularly ones in male-dominated professions, have been taught never to become - emotional, hysterical, crazy. Emotion is how women who want to be taken seriously are undermined and dismissed. Even if you’re perfectly sane, being emotional - and most especially, being angry - devalues you and your professional contribution. A woman can be called crazy simply for behaving like a normal human being rather than a robot (and of course, if she behaves robotically and unemotionally, she’s a cold bitch). But Carrie isn’t simply emotional (though she is that too, and worst of all, she allows her feelings for a man to cloud her judgment) - she actually is crazy and hysterical, in the proper clinical sense rather than the exaggerated one which attaches to any feminine display of emotion, and profoundly pathetic and unattractive in that state. And she’s completely right, the only person who figures out Brody and Abu Nazir’s plans and motivations, and the person who saves the day by being hysterical, infecting Brody’s daughter with enough of that hysteria that she calls her father and convinces him not to blow himself up.

It’s certainly possible to read this arc as purely tragic, Carrie’s self-destruction being the cost of saving the world (though this is a character arc that is applied to men as often as women, for example in Thomas Harris’s Red Dragon), but to my mind its effect is more complex. It makes a crazy, hysterical woman into a hero without in any way mitigating her craziness or hysteria, and thus defangs the argument that emotion in women is a weakness. It’s the rational, sane men around Carrie, who turn away from her unattractive mania with distaste and embarrassment, who are blind and incompetent, and it’s that same inability to look past surfaces that leads them to put their trust, wrongfully, in Brody - just as Carrie performs hysterical femininity, Brody performs stalwart masculinity. Both are misleading.”

All of which is to say, we’re really fucking pumped to see how Tasneem’s role expands for the rest of the season, and we think the array of women in Tasneem, Carrie, and Jenna and their varying degrees of power is going to be really interesting to see unfold.

Sara is obsessed with this shot. She’s obsessed with the set design of Samira’s apartment. She’s obsessed with this moody lighting. She’s basically just obsessed.

Last week we had a slow pan around Jalal to reveal Tasneem. This week we have a similar slow pan around Carrie to reveal Jenna. This definitely means that Sara’s theory that Jenna will “single white female” Carrie is right on track.

Also, Gail hereby declares Carrie’s delicate silver jewelry her “FULL circle earrings,” because everything is coming full circle this episode, including accessories.

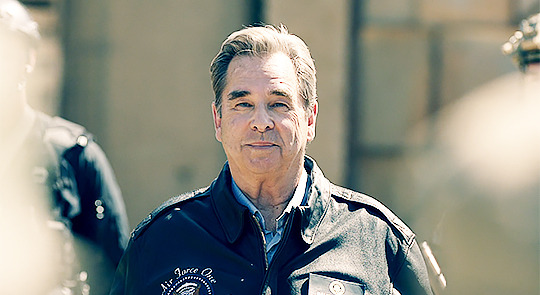

That said, we can’t deny the power of this shot. First, we have to note what’s going on in the background (which is actually in focus). President Beau has just arrived off Air Force One and immediately stops for a photo op with the Afghan president. From the beginning, the show is clear this is an optics-based trip.

But we really love this image of Carrie and Jenna (out of focus, but in the foreground) side by side. Again, they mirror each other, but in opposite ways (“So they’re mirror opposites?” --Sara’s brain). Carrie’s light hair versus Jenna’s dark hair. Jenna’s light jacket versus Carrie’s dark one. It’s eerie.

On the podcast we talked at length about the scene between Beau and Carrie. It’s genuinely moving. The staging of it is unique as well. The camera shoots them both at the same height. They stand close together. Ironically, the power dynamic seems almost equal. He’s one of the few people who’s ever acknowledged the sacrifices she’s made in service of her country.

Their twin smiles here are all the more tragic following the sequence of events that closes the episode. They all sincerely want peace. So many characters smile real, genuine smiles this week. That’s not a normal Homeland occurrence!

And they all legitimately believe in what they’re doing. They believe they’re doing the right thing. Maybe they are. But partly out of necessity, and partly out of more selfish desires (Hayes later says it’s all about getting a second term), they get caught up in the theater of it all. They make poor decisions. They take the wrong risks.

Every so often in this series we have to abandon screenshots in favor of gifs in order to truly capture ~the moment~ and this is one of those times! The way Claire plays Carrie’s reaction here is so specific, so nuanced and strange and wonderful. These “lived in” moments are something we’ll really miss when the show is over.

IJLTP.

We’ve all been there, Carrie.

This is another interesting shot choice. We’re not sure what its purpose is, other than to add interest to a fairly run-of-the-mill scene. But still, the set design! *heart eyes*

Sara’s note for this shot was “Saul is so extra.” We talked about genuine and sincere smiles above and Saul’s here does qualify… sort of. This is halfway between genuine and self-aggrandizing. AKA “where Saul lives 100% of the time.” He looks like a director about to screen his short film at Sundance. The red curtains parting slowly behind him are Too Much.

Tasneem and G’ulom are the kids in the back of the classroom who are so fucking done with this shit but can’t leave because they’ll get detention. We will continue to stan.

It’s a classic Homeland device to show a significant moment from a variety of perspectives, especially if those perspectives involve screens. The multitude of angles on Beau’s speech here reminded us a lot of Keane’s resignation speech in the Oval Office in “Paean to the People.” Coincidentally, that was her last hurrah as president too.

(P.S. Another Saul over-the-shoulder shot!)

Two selfies in one episode!

We loved the payoff to Max’s subplot. For once this season the weird LA filter actually looks nice! These are beautiful shots and the reflection in Max’s glasses is especially striking.

The skull and crossbones on the barracks is an ominious detail. As is the rock labeled “Boredom Rock.” Death and boredom really have been the two extremes of Max’s stint at the combat outpost.

We’re still divided on the merits of the “Carrie has to save Samira” storyline, but the camerawork here, with Carrie’s armed hands appearing out of nowhere, was pretty cool.

This RPG shot was one of the cooler special effects the show has done in a while. The entire sequence of Chalk One looking for Chalk Two was tense and thrilling and extremely well-executed.

Bringing us back to the ops room, the “LOSS OF SIGNAL” projected now for both helicopters is pretty chilling.

This is now Sara’s favorite shot of the entire series and we’d be remiss if we didn’t mention that it’s another over-the-shoulder Saul shot. This time he observes one of the crowning achievements of his long career literally blowing up in his face.

Visually, this shot anchors the viewer back to the Carrie/Saul relationship, the central one of the show. The black blankness--and the failure it represents--engulfs the frame.

We love the choice to end the episode on Carrie alone. It refocuses the event back to her. The horror in her eyes, welling up with tears, is palpable. How does Carrie feel? Alex Gansa explained that the writers wanted to create a new 9/11 with this maybe-assassination of the president. And it’s a fitting bookend for the show in many ways. In Homeland’s pilot, Carrie says she “missed something that day,” misdirecting blame to herself for not preventing 9/11. Now, in the final season, the show seems poised to tell a story in which Carrie is blamed for the “new 9/11.”

Strap in, folks. It’s gonna be a rough ride.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

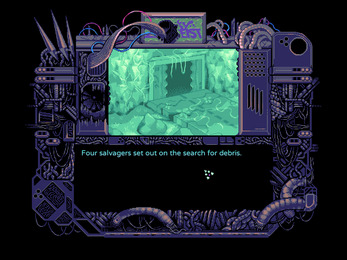

There is No Reason for you to Live. Part two: Excess

This is part of chapter I have written in the last two weeks, which uses the game Sticky Zeitgeist: Episode 2 Aperitif by Porpentine and Rook to draw out processes of art practice. I presented the beginning of the first part of this chapter at Beyond The Console: Gender and Narrative Games in London at the start of 2019. This is still very much a work in process, I’ve not even read this section back before posting it here. But I am very interested in the overlaps between Cixous’s figure of “woman”, “Becoming-Woman / Becoming-Girl” in Deleuze and Guattari, Bataille/Kristeva’s “Abjection” and “Johanna Hedva’s Sick Woman Theory” in regards art practice and trans* identity.

Part two: Excess “Small salvage is $5. Hear that sis, you’re $5. Nooooo” (Heartscape & Rook, 2018).

Excess is a concept which arises in many areas of George Batailles work which spans art, literature, politics, economics, anthropology and mysticism. The concept, or rather an aspect of it, is particularly near the surface and therefore easy for us to grasp here, in Bataille’s essay “The Notion of Expenditure” (Bataille, 1985). Bataille begins by stating that while “there is nothing that permits on to define what is useful to man” (Bataille, 1985). Classical utility can be understood as follows;

“On the one hand, this material utility is limited to acquisition (in practice, to production) and to the conservation of goods; on the other, it is limited to reproduction and to the conservation of human life” (Bataille, 1985).

In contrast to utility Bataille positions “pleasure”, which he argues society judges to be lesser than utility in the eyes of society and is therefore permissible as a “concession” (Bataille, 1985). However Bataille proposes that just as a young man’s desire to waste and destroy demonstrates that there is a need for this kind of pleasure even while this cannot be given a “utilitarian justification”, “human society can have, just as he does, an interest in considerable losses, in catastrophes” (Bataille, 1985). Bataille sets this up as the tension between the ideological authority and the real needs for “nonproductive expenditure” which are at times not even articulable through the language of that authority. As examples of unproductive expenditure Bataille offers the following list;

“Luxury, mourning, war, cults, the construction of sumptuary monuments, games, spectacles, arts, perverse sexual activity (i.e., deflected from genital finality)” (Bataille, 1985).

A handful of these examples are examined further, but Bataille argues that in each “the accent is placed on a loss that must be as great as possible in order for the activity to take on its true meaning” (Bataille, 1985). Just as Lyotard identified affect as the point of excess which marks art apart from other things, and Cixous defines her figure of woman in terms of an unending outpouring, Bataille has identified “the principle of loss” (Bataille, 1985) as essential to a range of activities including but spreading beyond art and literature. The excess in Lyotard as deployed by O’Sullivan is that which is beyond the system of accounting for art, namely affect. In Cixous the excess is the capacity of the artist-figure woman when enacting ecriture feminine, to operate beyond the system prescribed by power to the production of art. As Allan Stoekl notes in his introduction to the edited volume “George Bataille Visions of Excess Selected Writings, 1927 - 1939”, for Bataille “People create in order to expand, and if they retain things they have produced, it is only to allow themselves to continue living, and thus destroying” (Stoekl, 1985). Bataille’s nonproductive expenditure is what is being freed in Cixous’s process of Ecriture Feminine, and I would therefore further argue, is being deployed in Aperitif, an artwork which deals with excesses both offered and implied (and therefore to be created at the point of interface with audience). More than this though, Bataillian excesses appear within the world of the game which the characters, and by extension us as players occupy. I would like to explore how different kinds of excess appear in Aperitif, and how these fit with Bataille’s observations around class struggle and manner in which those in power retain control of non-productive expenditure, including the expenditure of other beings. Finally I will consider these excess as areas which clarify Aperitif as abstracted horror and Ecriture Feminine.

A point where waste is rendered visible in Aperitif, in The Laugh of The Medusa, and in the work of Bataille, in the act of masturbatation. The character Ever, from whose perspective we begin Aperitif is the sole player character in the episode of the “No World Dreamers: Sticky Zeitgeist” which precedes it, “Hyperslime” (Heartscape & Rook, 2017) [KEYWORD Link to Smeared into the Environment]. Ever’s story in Hyperslime begins with a scene of anal drug use and masturbation which is interupted by the call to attend work. In the following episode, Aperitif, we learn that this work is in fact community service after Ever “whacked off in public” (Heartscape & Rook, 2018). This detail of Ever’s life is exposed by Brava but in Ever’s interior monologue we learn that she herself does not fully understand why it occurred. Ever can only speculate on the reason for her doing something she identifies as harmful, and that the experience was like “watching through a window” after which she “blacked out” (Heartscape & Rook, 2018). As an aspect of Ever’s character masturbation points to her isolation and desire, and to her struggle with the unbearable tension of shame which she alludes to when considering that “maybe I just wanted what they thought about me to come true” (Heartscape & Rook, 2018). This enfolding of personal desire, the projection of being seen by another, the need to resolve an uncertainty, and the potential shame which runs through it is precisely how Cixous describes the struggle to produce Ecriture Feminine;

“[Y]ouv’e written a little, but in secret and it wasn’t good because you punished yourself for writing because it didn't go all the way; or because you wrote irresistibly, as when we would masturbate in secret, not to go further but to attenuate the tension a bit, just to take the edge off” (Cixous, 1976).

Ever, who the artists attribute the title/archetype/role “The Loser”, seems perpetually to be trying to manage the tension of her desires, with the only temporary resolution occurring in some kind of overwhelming loss of self. The struggle for a creative process which Cixous describes is not something I can identify in Aperitif because it is very much embedded in the experience of the process of making, which I do not have access to. However, I would argue that Aperitif is open to being played in a manner which is analogous if not in a similar affective register to the tension and collapse cycles of Ever. We begin both Aperitif and its prequel controlling Ever, but prior to the narrative beginning and still within the context of the title menu the game instructs us that we can “hold escape until you black out” (Heartscape & Rook, 2018). On one hand this instruction is informing player-audience of the keypress which will allow them to exit the game. On the other hand, the use of the term “black out” echo’s Ever’s use of the same. When playing the game-artwork, I feel that the means of exiting has been embedded with an emotional resonance. Playing the game-artwork now has a resonance with Ever’s narrative, even outside of the points of play where I am controlling her character. The emotional content of the game is foregrounded, and the promise of the opportunity to in a manner, ‘lose consciousness’ as an escape from it invites/dares the audience-player to engage more with that content. We have permission to be a loser, to fail.

The concept of failure here is made complex when it is brought into the parameters of the game itself. It becomes an action. Ever berates herself for failure, but the artwork-game does not pass this judgement, and in aligning us with her and with failure, it invites us to not pass judgement either. Returning to Cixous, the other resonance of the allegory of masturbation to Ecriture Feminine is that the writer is given permission to write for themselves and for the act of writing to be self gratifying rather than requiring it before another. In “The “Onanism of Poetry”: walt whitman, rob halpern and the deconstruction of masturbation” the poet and lecturer Sam Ladkin notes the contradiction in the considered works “between masturbation as the failure of fecundity, spent energy without the returns of an investment” and something which has value in sowing “male seed across the typically female gendered earth” (Ladkin, 2015). In Ladkin’s work, the discourse around Onan, the poets being discussed, and the particular queer theory used tends toward the image and language of male homosexual desire but the author emphasises that beneith this the structure of “failed or suspended address” is not specific to a particualr “gendered identification fo desire” (Ladkin, 2015). In Cixous this contradiction between value and waste is articulated as fight to develop one’s own value system. To engage based upon the subjects desire, rather than exchange within an external economy which ascribes or denies a degree of value based on adherence to preexisting parameters. Ladkin explores the potential to “recuperate the wasteful excess of masturbation via the general economy of Bataille” yet in the author’s focus on the ejaculatory “economy of finitude” and the monetary economy of pornography, this avenue is effectively discounted and not further pursued (Ladkin, 2015). However I think there is a different dialectic at play in the systems of Bataille, and which are played out in the world of Aperitif as the struggle between the individual release of excess of the player characters, and the destructive forms of excess employed by power and authority, which render both landscape and those same player characters, as waste.

Bataille lays out his position that “Man is an effect of the surplus of energy: The extreme richness of his elevated activities must be principally defined as the dazzling liberation of an excess. The energy liberated in man flourishes and makes useless splendor endlessly visible” (Bataille, 2013). In Aperitif, this dazzling liberation of an excess is attempted by characters such as Brava, but it is always curtailed by the tyranny of an outer authority, the call to attend community service, the police. The motif of masturbation in Aperitif points to repeated denial of excess in the following of individual desire. As previously noted, character’s remain in a limbo of struggling survival, to “never perfectly live or die” (Heartscape & Rook, 2018). In this state the following of individual desire into the expression of excess is denied to everyone except those who can afford it, as Brava recalls;

“When the internet 3 was invented the economy of really extra fucked, most stores were automated. Except the usual dollhouse experiments ran by rich people who fantasized about running a restaurant or cupcake shack of some shit” (Heartscape & Rook, 2018). Bataille argues that “As the class that possesses the wealth -- having received with wealth the obligation of functional expenditure -- the modern bourgeoisie is characterized by the refusal in principle of that obligation” (Bataille, 1985). Bataille maps how earlier structures of social and material power would have led to the possessors of such power and wealth to express this through expenditure such as feasts, sacrifices and the construction of elaborate religious and cultural objects. In contrast to this, the logic of accumulation unders Capitalism leads to a “hatred of expenditure” (Bataille, 1985). In Aperitif this is demonstrated in the quote above from Brava showing that even with full automation, the bourgeois can only either imagine, or allow itself, a useless expenditure which takes the surface form of work by running a “cupcake shack” (Heartscape & Rook, 2018).

There is a second manner in which excess plays out through the agency of the authority in Aperitif and this is concerned with the rendering of subjects as objects, and then waste. Cultural theorist Sylvere Lotringer attempted to reexamine the concept of ‘Abjection’ in the work of Bataille, identifying a different trajectory from that subsequently developed by Kristeva in “Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection” (Kristeva, 1984). Lotringer’s short essay “Les Miserables” (Lotringer, 1999) positions Bataille’s fragmentary addresses of abjection written in the early 1930s as specifically in response to the “only truly original political formation to have emerged since the end of WWI [...] fascism” (Lotringer, 1999). Lotringer notes that in “The Notion of Expenditure” Batialle deplores the manner in which the bourgeoisie attenuate the damage done and “ameliorate the lot of the workers” (Bataille, 1985) as “abysmal hypocrisy” (Lotringer, 1999); “The ultimate goal; of industrial masters, he asserted, wasn’t profit or accumulation, but the will to turn workers into pure refuse. Instead of extracting surplus value from the wretched population working in [the] factory, they enjoyed a surplus value of cruetly” (Lotringer, 1999).

The world of Aperitif presents a world in which authority has still not passed through its hypocrisy, but nevertheless continues to render the workers as waste. The company that employers Ever and the others to scavenge is represented by a character called “The Therapist”, which at least suggests a role of care, yet the job remains one of collecting scrap from a toxic environment which degrades and destroys their bodies (Heartscape & Rook, 2018). Lotringer’s published his essay Les Miserables in the edited book “More & Less” along with Bataille’s essay “Abjection and Miserable Forms” and interview with Kristeva titled “Fetishizing the Abject” (Bataille, 1999; Lotringer, 1999; Lotringer & Kristeva, 1999). Both Lotringer’s essay, and the line of questioning in the interview are in part concerned with a bifurcation within Bataille’s concept of abjection, which has not been given as much attention in its rearticulation and development by Kristeva in Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection and that works continued influence. Lotringer draws from Bataille a distinction between “The union of miserables reserved for subversion” and “wretched men rejected into negative abjection” (Lotringer, 1999).

The difference between the positive abjection which leads to action, solidarity, and perhaps martyrdom, and the negative abjection which leads simply to inertial, apathy, and alienation. The tension between these two forms of Abjection is something which appears throughout Aperitif, as its protagonists navigate a world of trash, see themselves to degrees become or be made trash, and navigate the threshold between agency and alienation. In his summary, makes the following statement about Abjection without differentiating between the positive or negative form;

“Abjection doesn't result from a dialectical operation- feeling abject when “abjectified” in someone else’s eyes, or reclaiming abjection as an identity feature- but precisely when dialectics breaks down. When it ceases to be experienced as an act of exclusion to become an autonomous condition, it is then, and only then, that abjection sets in” (Lotringer, 1999).

It is unclear in this text whether Lotringer is arguing that what he elsewhere describes as people “becoming things to themselves” (Lotringer, 1999) defines Abjection in both positive and negative forms, or whether he is arguing for the primacy of the negative form. It is possible to read this as Lotringer trying to shift the definition of Abject to the negative, and the interview with Kristeva that will be addressed shortly in some ways supports this view.

Returning to Goard’s text on the trans* body and the cyborg it is worth nothing the importance of the process by which either are rendered Abject is addressed, though with different terminology;

“The dream of a world without surplus, illegitimate bodies is not feasible without a society that relies on surplus” (Goard, 2017).

Goard makes steps toward a politics whereby “bodies-made-surplus” (or trans* people and others) are not redefined, rearticulated and included, but simply allowed to exist (Goard, 2017). The politics not of “defining but defending” (Goard, 2017). Goard’s position seems to cut across Lotringer, proposing the act of oneself making and being made a thing as still containing revolutionary agency. In Lotringer’s reading of Bataille’s Abjection, at least in its negative form, is a place without hope of agency, a kind of living death. However Goard does seem to offer a position which is neither that living death, nor the simple dialectical struggle of being labeled abject and owning this label. Goard’s proposal becomes about a surplus yes, but an undefinable surplus which crosses categories of gender, class, race, ability, and attempts to tactically use such categories whilst aiming to ultimately destroy them. Goard articulates this party with the statement that “we should be deeply skeptical of placing value on the acquisition of formal rights when they are used in the legitimation of a violent border regime” (Goard, 2017). At the same time, Goard refuses the dialectic of power vs resistance by pointing out that the tactic entering into established modes of identity such as the gender binary are important at times for safety and so should not exclude a person from solidarity toward a common project of gender abolition for example.

[Footnote: The acquisition of rights for one group used as a means to justify is articulated by post-colonial theorist Jasbir Puar as “Homonationalism” in the 2007 book “Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer times” and developed further in the text “" I Would Rather Be a Cyborg Than a Goddess": Becoming-Intersectional in Assemblage Theory” (Puar, 2007, 2012). In the latter text Puar focuses on expanding upon the form’s negotiation between Kimberlé Crenshaw’s concept of “intersectionality”, “analyses that foreground the mutually co-constitutive forces of race, class, sex, gender, and nation” and an assembalge model which identifies “ the “retrospective ordering” of identities such as “gender, race, and sexual orientation” which “back-form their reality” (Puar, 2012). Puar sees these too positions not as “oppositional but rather,[...] frictional (Puar, 2012).]

As has been indicated throughout this chapter, Aperitif frequently plays establishing categories, names, structures, or identities, and having things which are surplus to these, which disrupt with either a counter-order, or the refusal of any order. Characters in some places self-define their identity on an axis of the gender binary, whereas the the game leaves other identity markers not only unknown but unacknowledged. The game frames and withholds information through its limited graphics showing animal ears, and text which trails off to convey emotion through lack of definition. An implication through explicit and implied information is that all characters in Aperitif are “girls”. However this category is broken open so wide as to be more in line with Cixous use of woman as catagory abstracted from sex, gender, or identity. “Girl” can be a category if it is deployed in that way, or it can something less stable.

Something about the four protagonists in Aperitif that remains consistent, and is presented unambiguously, is that the society they inhabit does not value their existence. Throughout the narrative, each protagonist struggles with whether or not they themselves value their own own existence. Society is ordered in a way that each of the four girls needs to undertake a job which is extremely damaging to their physical and mental health. A common thread throughout their conversations and many interior monologues is the consideration of whether than can, or should, survive this. In the interview with Lotringer titled “Fetishizing The Abject”, Kristeva describes her development of the concept through researching “borderline” clinical states in psychoanalysis;

“Without going as far as psychotic persecution, without going as far as autistic withdrawal, [the patent] creates a sort of territory between the two, which he often inhabits with a feeling of unworthiness, of even deterioration, a sort of physical abjection if you like” (Lotringer & Kristeva, 1999).

It would be out of the remit of this research to follow further into these pathologies. However; the oscillation of internal states, struggle, exploded categories, the question of self worth and being made thing invites another text to placed alongside Aperitif and Abjection. “Sick Woman Theory” by writer and artist Johanna Hedva (Hedva, 2016) is an examination of the politics which intersect in the bodies of disabled people, and offers a figure of protest in the form of the Sick Woman. As Hedva states, “Sick Woman Theory is an insistence that most modes of political protest are internalized, lived, embodied, suffering, and no doubt invisible” (Hedva, 2016). Applying Sick Woman Theory to hypothetical borderline case described by Kristeva repositions them as a political agent;

“The Sick Woman is all of the “dysfunctional,” “dangerous” and “in danger,” “badly behaved,” “crazy,” “incurable,” “traumatized,” “disordered,” “diseased,” “chronic,” “uninsurable,” “wretched,” “undesirable” and altogether “dysfunctional” bodies belonging to women, people of color, poor, ill, neuro-atypical, differently abled, queer, trans, and genderfluid people, who have been historically pathologized, hospitalized, institutionalized, brutalized, rendered “unmanageable,” and therefore made culturally illegitimate and politically invisible” (Hedva, 2016).

As the quotation marks around medical terms indicate, Hedva’s Sick Woman Theory is a kind of tactical categorization in order to refute a larger number of categories. Sick Woman Theory reads Abjection not from the position of analyst, but “the person with autism whom the world is trying to “cure”” as well as a multitude of other positions whose comonolity is that they are disenfranchised, suffering, and abused (Hedva, 2016). From the former position, categories become the norm, and things which transgress them a deviation or disruption. From the latter position of the multitude, the transgression across categories is the norm. It is possible to read the category of “girl” in Aperitif as Sick Woman, just as both, like Cixous’s woman’s writing, serve to encapsulate a sea of difference with an act of refusal against categories.

As mentioned previously in this chapter, a focus of Lotringer’s interview with Kristeva is questioning whether Abjection can form an oppositional function to power. Lotringer is particularly concerned with what he sees a broad tendency or movement within art and culture which attempts to reclaim the process of being made Abject and instil it with emancipatory potential. When asked at one point on this Kristeva responds “I feel very ambiguous in relation to this movement [...] I don’t adhere to it, and at the same time I realize that, as a kind of strategy, it is opposed to some kind of intolerable conservatism, so it's hard to adhere to that” (Lotringer & Kristeva, 1999). Kristeva’s concession is based in dialectic of Abjection against what must be imagined as a kind of totalitarian homogenous cultural sterility. Sick Woman Theory, is presented as “an identity and body” not against but in place of one of intolerable conservatism (Hedva, 2016). Hedva at point identifies this conservatism as the privileged existence, or “cruelly optimistic promise” (Hedva, 2016) of this existence, embodied by the;

“white, straight, healthy, neurotypical, upper and middle-class, cis- and able-bodied man who makes his home in a wealthy country, has never not had health insurance, and whose importance to society is everywhere recognized and made explicit by that society; whose importance and care dominates that society, at the expense of everyone else” (Hedva, 2016).

However, Kristeva seems to be describing an oppositional practice in line with what Lotringer describes as “reclaiming abjection as an identifying feature” (Lotringer, 1999). This Abjection is oppositional, it uses the definition given to it by what it opposes, and defines itself through that opposition. Sick Woman Theory instead repositions itself as the exclusion of what it can be seen to be opposing. Hedva argues that capitalism sets up binary between a default position of “wellness” and deviation from this in the form of “sickness”. To simply embody this deviant category of “sick” would be exactly the oppositional process of Abjection described by Lotringer and Kristeva. However, Hedva also argues that under capitalism “wellness” is positioned as a temporal norm, whilst “sickness” and therefore “care” is positioned as temporary. Hedva’s position can be seen as arguing that a broad encapsulation of vulnerabilities, oppressions, and suffering should be considered the norm. Crucially, care for oneself and for others, could and should follow as another norm. It can then be proposed that Sick Woman Theory, is not a struggle with another, but a reconfiguration of the context underneath both which shifts perspective. This reconfiguration is analogous to an operation I have elsewhere discussed as occurring within horror narratives, using the example of the film “Ringu” (Nakata, 2000). [LINK TO “FROLIC IN BRINE” performance SCREENPLAY]

Hedva’s call for the centering of their broad category of sickness, which includes not just sufferers of illness, but also victims of the violent enforcement of acceptable categories of gender, sexuality, class, etc. does find a direct parallel in Kristeva’s thought;

“These states, far from being simply pathological or exceptional, are perhaps endemic. And it is perhaps against this sort of structural uncertainty that inhabits us that religions are set in motion, at once to recognise them and to defend ourselves against them” (Lotringer & Kristeva, 1999).

I am wary of pursuing an argument regarding the subjectivities included within Hedva’s Sick Woman predating, and perhaps causing the social structures which their existence transgresses. Such an enquiry would move beyond the scope of this project, which is concerned with the practice of art.

In Fetishizing The Abject much of Lotringer’s direction of the interview focuses on ways in which further discourses, including art, have misincorporated Abjection following Kristeva’s popularisation of the term. While a number of art tendencies and specific exhibitions are critiqued, it is the speculation on what Abjection could do in art that is most relevant here. Both Lotringer and Kristeva agree that when something is placed in a gallery, it “becomes a new identity” and thus “fetishised” it joins other “[i]institutional objects” (Lotringer & Kristeva, 1999). Regarding potential to move beyond this, Kristeva proposes that “verbal art, insofar as it eludes fetishization, and constantly raises doubt and questioning [...] lends itself better perhaps to exploring those states that I call states of abjection” (Lotringer & Kristeva, 1999). I am skeptical about the claim that any art form including verbal art might elude fetishization, but the operation of constantly raising doubt and questioning resonates with other observations in this chapter, as well as this PhD project overall. Elsewhere I discussed a concept from my research which I call Incomplete Provocations [LINK TO TEXTS]. Also, the use of unreliable narrators occurs in the majority of what might be called the fiction elements of this project. Something which is important to note regarding at least my use of unreliable narrators is that there is a rarely deliberate deception on the part of the narrator. Deception would necessitate that the narrator knows more than the audience who learns only from that the narrator reveals, at least initially. The application I am more interested in, is the unreliable narrator as point of which by either being cognitively compromised or simply different, has another perspective on events. The ideological position implied through this is that there is no one narrative which could encapsulate the entire event and therefore resolve it. There is always doubt and questions, each of which solicit speculation from the audience. In Deleuze and Guattari’s “A Thousand Plateaus” (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987) the line that illustrates this non-deceptive unreliable narrator occurs at the start of the chapter “1730: Becoming-Intense, Becoming-Animal, Becoming-Imperceptible…”. While beginning an account of a film, the authors offer the disclaimer, “My memory of it is not necessarily accurate” (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987). The author’s uncertainty in their memory would fall within my description of the cognitively compromised unreliable narrator, and before even getting to the recounted film, doubts and questions are ready to be raised. These doubts and questions do not all have to be positioned in the gap between recollection and what was witnessed, though in this case we could look for differences between Deleuze and Guattari’s account, and the film itself. The other doubts and questions that I am interested in project not backwards in time to the witnessing but forwards. What is interesting to me is not what is lacking from the film in the recounting, but how the recounting is a process of addition which grows from the film even while it might leave out parts of that source material. In this way, the unreliable narrator offers a provocation not for a return to the stillness of certainty, but for the movement of more emerging possibilities. Kristeva proposes something similar in her proposal for future Abject art, which involves processes of “anamnesis on the one hand, and gaming on the other” (Lotringer & Kristeva, 1999). In terms of amnesia Kristeva expands this as “a sort of eternal return, repetition, perlaboration, elaboration” (Lotringer & Kristeva, 1999). Within Aperitif the process of amnesia enacted as the player returns to walking a path through the same environment with different characters, as well as through the game form which allows itself to be replayed.

[FOOTNOTE: For a radically different analysis of a comparable creative terrain to Kristeva’s Anamnesis see Mark Fisher’s “Ghosts of my life: writings on depression, hauntology and lost futures”. “This dyschronia, this temporal disjuncture, ought to feel uncanny, yet the predominance of what Reynolds calls ‘retro-mania’ means that it has lost any unheimlich charge: anachronism is now taken for granted” (Fisher, 2014).]

Kristeva follows Anamnesis with Gaming which involves “compositions, decompositions, recompositions” and is presented as a continuation of the “trajectory” as Anamnesis (Lotringer & Kristeva, 1999). Examples provided for this process involve the process of chance through rolling dice, and the “glossolalia in Artaud, or like Finegan’s Wake” (Lotringer & Kristeva, 1999). This resonates with Aperitif on multiple levels. At the game level Aperitif, despite being fairly linear in form, composes, decomposes,and recomposes itself continually. From the position of the player audience, this is perhaps most clear as the game shifts its genre and method of play at points. At points the player controls characters which walk around an environment and interact with one another in the manner of a role playing game. At other points the game switches to the form of a medical simulator where the player but diagnose and repair a robotic character with a completely different mode of interaction from the role playing game sections. This medical simulation then decomposes further as the performing of a specific repair sakes the form of side scrolling “shoot ‘em up” as a game within a game within a game. What would however be more in keeping with what Kristeva is describing would be evidence that at some level the making of this artwork included a shift to a less consciously direct mode. The reference to dice alongside glossolalia leads me to conclude that Kristeva’s Gaming is about the movement between conscious decision making, and something else which destabilized it, before potentially returning to conscious decision making. This destabilisation could be through the cold probability of a dice roll, the path for the works creation decided by the resulting number. The inclusion of Finegan’s Wake and Artaud’s glossolalia suggests that the destabilisation does not have to be the surrender to chance. Destabilisation could include the shift to using or creating words based on their sound rather than meaning for example. Cultural theorist Michel De Certeau described glossolalia as “vocal vegetation” not an exceptional thing constrained to the devout and artists, but the “bodily noises, quotations of delinquent sounds, and fragments of others' voices [which] punctuate the order of sentences with breaks and surprise” (De Certeau, 1996). The language in Aperitif, particularly where it comes to building its world through this language feels full of moments of shifts to a destabilised mode. Swamp-Dot-Com is populated with things like “bombo cabbage bludbud”, “lichen mommy board” and “whackback” (Heartscape & Rook, 2018).

[FOOTNOTE: A methodological decision has been made not to include research drawn from Heartscape and Rook’s other work, in order to focus on how this can inform methods of art practice, rather than drawing out the tendencies of these specific artists. However, it is worth noting that the processes of Kristeva’s Gaming are evident throughout Heartscape’s individual art practice. Heartscape curated the 2018 exhibition at Apexart in New York, entitled “Dire Jank” (Apexart, 2019). Dire Jank included artist Tabitha Nikolai’s video game “Ineffable Glossolalia” (Nikolai, 2018) and “Divination Jam” which invited the audience to “use divination, randomization, etc to make your game. when you get stuck, instead of feeling like shit, let some arcane system decide for you! rolling a die, i ching, tarot, anything that invokes fate! many ancient systems have been digitized, or you can look for randomness in the world around you…” (Heartscape, 2018). Furthermore, Heartscape’s 2016 novel “Psycho Nymph Exile” both contains the same collapsing worldbuilding language as Aperitif, and features such processes within its plot. “The crystal gives them an allergic reaction to language. Each girl has a unique combination of trigger words. They sit on the floor in rows, mumbling under their breath, reading from dictionaries until they find their combination” (Heartscape, 2016).]

This play in language is subtle, but I believe it a shift away from the direct conveyance of meaning to sounds and the joy of what words written down can do.

An area the gap between Kristeva and Lotringer’s Abject Art, Hedva’s Sick Woman Theory, and Aperitif widens is with the issue of the abject and identity. Lotringer sees Abjection’s relation to Fascism which he stresses is its origin in Batialle’s text “displaced” (Lotringer & Kristeva, 1999). He broadens this further with the claim that “politics has become the politics of the notion of identity” (Lotringer & Kristeva, 1999). This broad position is agreed by Kristeva who replies “everything has been taken up by the “politically correct” which are in fact identity related claims” (Lotringer & Kristeva, 1999). It is this identity that Kristeva and Lotringer see in what they consider the problematic Oppositional Practice already outlined. I would like to argue though that their perceived problem with Abject identity would not apply to the way identity figures in Sick Woman Theory. Hedva sets out their position with clarity;

“The sick woman is an identity and body that can belong to anyone denied the privileged existence, or the cruelly optimistic promise of such an existence- of the white, straight, healthy, neurotypical, upper and middle class, cis and able-bodied man” (Hedva, 2016).

Sick Woman Theory is not a politics of sexual identity, but a broad identity which encapsulates sexual identity along with bodily, cognitive, and class differences. This is not the sidestepping of class struggle and opposition to fascism Lotringer in particular is concerned with in his observations about previous attempts at an Abject turn in art. Hedva creates an amorphous, fluid grouping, brings to the centre difference and care under the banner of the Sick Woman. Returning to The Laugh of The Medusa, Hedva’s project has strong resonances with Cixous’s; “If there is a “property of woman,” it is paradoxically her capacity to depreciate unselfishly: body without end, without appendage, without principal “parts.” If she is a whole, it’s a whole composed of parts that are wholes, not simple partial objects but a moving, limitlessly changing ensemble, a cosmos tirelessly traversed by Eros, an immense astral space not organised around any one sun thats any more of a star than the others” (Cixous, 1976).

Cixous frames this “property of woman” within a text which is concerned with the practice of making art, but this practice is part of process which includes woman putting herself “into the world and into history” (Cixous, 1976). Writing, is embedded in a politics of living. For Cixous’s woman to write only in the dominant mode of man’s writing, is to be restricted not only from writing herself (as Cixous would put it) but to enter into the world as a subject, as an agent. If we read Cixous’s woman not in terms of an essentialist category which might be attached to some biological marker, but as a class category, she readily aligns with Hedva’s Sick Woman. Cixoux’s contemporaries Deleuze and Guattari describe the process of “becoming-woman” which can be considered like the former’s woman but now not a class but a process (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987). MacCormack gives a succinct explanation of Becoming-Woman, “Woman as minoritarian is defined by lack and failure so an element of woman - gesture, fluid libidinality - taken in or as part of the self will necessarily alter the self” (MacCormack, 2008). In Hedva’s text, the woman is named for the “subject position [that] represents the uncared for, the secondary, [...] the non-, the un-, the less-than” (Hedva, 2016).

Even when addressing cisgendered women, the call Cixous is making entails Becoming, which MacCormack describes as selecting “certain specificities and intensities of a thing and [dissipating] those intensities within our own molecularities to redistribute our selves” (MacCormack, 2008). Cixous calls us to redistribute into ourselves the intensity of fluid libinality which she calls the “unflagging, intoxicating, unappeasable search for love” (Cixous, 1976). This pull of desire and connectivity reads like an antithesis of Valerie Solanas’s description of “the male” as an “unresponsive lump, incapable of giving or receiving pleasure or happiness” (Solanas, 1971).

[FOOTNOTE: For a trans* reading of gender in Solanas as creative process see writer Andrea Long Chu’s proposal that “Here, transition, like revolution, was recast in aesthetic terms, as if transsexual women decided to transition, not to “confirm” some kind of innate gender identity, but because being a man is stupid and boring.” (Long Chu, 2018).]

The Woman in Sick Woman Theory is similarly a source of creative desire, which Hedva explains through a description of some of their own symptoms;

“Because of these “disorders,” I have access to incredibly vivid emotions, flights of thought, and dreamscapes, to the feeling that my mind has been obliterated into stars, to the sensation that I have become nothingness, as well as to intense ecstasies, raptures, sorrows, and nightmarish hallucinations” (Hedva, 2016).

These descriptions form part of Hedva’s consideration of political agency of those, who for bodily, social, or other reasons cannot engage in the direct politics of public action. However the language, as with Solanas’s, is as concerned with emotion, affect, aesthetics, and creativity. Solanas’s Male is “incapable of empathizing” (Solanas, 1971) while “Sick Woman Theory asks you to stretch your empathy” (Hedva, 2016). Solanas’s manifesto is explicitly a response to the boredom society provocokes as it is dominated by the “psychically passive” figure of the Male (Solanas, 1971). Without exoticising and objectictifying illness, mental or otherwise, the subject of Sick Woman Theory is undoubtedly a creative force.

I hope that I have demonstrated that the world, characters, and player-audience experience of Aperitif have a resonance with theories of Abjection, and creative difference connected to a broad category of Woman. Aperitif is on one level, a video game about a group of runaway broken robots, and hybrid animal kids trying to improvise through wasteland failures, emergent tactics of living through giving and receiving care.

Throughout Aperitif, many things are left undefined, or only implied. Dialogues are full of the pointed absence of speech in ellipses. Delivery of information gives way to Gaming. Character’s themselves are unsure of what has happened, cannot remember, are too traumatised, or simply offer a conflicting view of events to one another. Finally the game itself, with its limited interface and graphics which hark back to games long before the turn of the millenium, makes clear that details are being withheld. With this in mind, the group of protagonists being self identified as, or implied to be “girls” rather than Women, can be understood through another Becoming proposed by Deleuze and Guattari, and explored further by MacCormack. Within the context of Becoming-Woman Deleuze and Guattari ask “What is a girl? What is a group of girls?” (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987). They consider Marcel Proust’s protagonist’s search for “fugitive beings” (Proust, 2010) and conclude that the Girl whether singular or in a pack, is “pure haecceity” (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987).

[Mark Fisher defines Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of Haecceity as “non-subjective individuation. [...] the entity as event (and the event as entity)” (Fisher, 2018).]

MacCormack states that the Girl is the “larval woman”, but “It is not the girl who becomes a woman; it is becoming-woman that produces the universal girl [...] the girl is the becoming-woman of each sex, just as the child is the becoming-young of every age” (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987). For Deleuze and Guattari, Girl is the individuation of Becoming-Woman, not attached to any substance or function, or “age group, sex, order, or kingdom” (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987). Girls in Aperitif are undefined, only self identified in one instance and they move “between orders, acts, ages, sexes; they produce n molecular sexes on the line of flight in relation to the dualism machines they cross right through” (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987). They speak in irony, silence, thoughts of sex and unspeakable past trauma and modify their bodies with drugs and used parts. They are elusive, arising moment to moment from encounters. MacCormack notes that the “less defined a term is within majoritarian culture the more larval the becoming and thus the move open to unique and unpredictable folding and unfolding the becoming” (MacCormack, 2008). Girls are capable of Abject art practices in the manner argued by Lotringer and Kristeva, slipping between dualisms, rather than in reactive opposition. As Deleuze and Guattari write, Girls “draw their strength neither from the molar status that subdues them nor from the organism and subjectivity they receive; they draw their strength from the becoming-molecular they cause to pass between sexes and ages” (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987). So it is no wonder that the Girls in Aperitif improvise in the wasteland of Swamp-Dot-Com. They are ungraspable in their identities, and forever on the way to something. They tell as much, even though for them the process might be traumatic, to “never perfectly live or die” (Heartscape & Rook, 2018).

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thought about how Finn and Poe are depicted in TLJ:

I don’t think Johnson was deeply racially biased in the way people think, though I think he might have a racial bias that’s not malicious, but also worth pointing out, since I always butt heads with that bias as a white writer.

I think Johnson wanted to give Finn and Poe solid character arcs to fit with the theme of overcoming failure, and I don’t think he wrote them as if they were Other, because I do feel somewhat familiar with what it feels like when characters are Other. I’m very alert to women being framed as Other, and in SW most droids and aliens are framed like that. also, old mentor figures can be Other, definitely maternal figures, most villains, expendable side characters, NPC-type folks in the plot who help the story along.

Stories have to be full of Others of one sort or another, and you can be Other in a sympathetic light or a negative light. You can be revered or reviled or ignored. You can be reduced to a stereotype or an archetype. And some stereotypes are more harmful than others because of their connection to real world structural oppression.

The only characters in a story who aren’t Other are characters who get POV time -- that’s just how it works, if the movie makes you see through a character’s eyes, they want you to project onto that character for those scenes. Finn and Poe are POV characters, so they’re not fully othered. Something else is probably going on.

I think Finn and Poe are written in ways that white men would comfortably project onto, if the characters were white men. Take Finn and his running away. It’s not as if male characters who have to learn to care about the cause are deeply disliked. Han Solo is a scoundrel with a heart of gold who spends a lot of time in ANH being reluctant to help the heroes, and then he finally shows his true goodness and saves the day. Finn being a bit jittery and focused on saving a girl he likes might seem less flattering, but think about all the awkward, foolish white male protagonists who get dunked on a bit for their flaws, but ultimately win girls’ hearts and save the day. I’m thinking Emmett from the Lego Movie as a key archetype. That’s... clearly something that white guys find relatable and enjoyable to project onto. Self-deprecating, but ultimately a power fantasy. Part of the power fantasy is watching someone who’s a bit of a loser become a hero through adversity, it makes you feel like you too could take adversity and turn it into positive change as well. And Finn isn’t even such an overstated example, but he does have a lovable-loser thing going on in TFA and TLJ. And then of course he gets to be fantastically heroic and good and brave, because we (lovable losers in the audience) would like to be that way as well.

Poe’s behavior in TLJ gives me very... uncooked Captain Kirk dough vibes. I love me some Kirk, and he’s such a passionate guy who breaks rules and defies authority whenever he thinks it’s right. And sometimes he gets it wrong, and misjudges the situation, but the narrative usually doesn’t punish him too much. And the reason for this is because Kirk has Spock and McCoy and the rest of his crew with him and he deeply trusts their advice and expertise. Spock will almost always tell Kirk to cool his tits, so Kirk feels safe getting hot-titted when he thinks it’s called for. He knows he has a limiter. That’s what makes him a good leader, he knows his shortcomings and surrounds himself with close friends who can balance those shortcomings out. He’s also a seasoned captain, wiser from having dealt with a lot of messy situations. But (forget the reboot movies lol cause I do) if you imagine a younger Kirk, you can imagine him getting all riled up about injustice and hatching one of his daring million-to-one gambits to save everyone -- and it turns out to be a bad move. It turns out he was wrong. And he gets a lesson about that, and this helps him grow into the good Kirkboy we love and respect.

The fact that Poe wants to rush out and save the day, but needs to learn patience, is something white men can find relatable and sympathetic.

But the thing is, I can understand people seeing Finn and Poe being written in this way, and understandably perceiving it as race-blind. Johnson put all these bits of character into them, but because he’s a white male writer who does in fact want to write Finn and Poe as likable and dynamic and engaging, he seems to have written things for them that are endearing when a white male does them.

People see the expressed interiority of Finn and Poe in The Last Jedi and get White Male vibes from it, not because they were written to be disposable or Other, but because they were given White Male interiority.

Now, arguably, Star Wars seems not to discern human races, and since so much of White Male interiority involves seeing yourself as the default and not ever questioning that status, while existing in an industrialized Westernized capitalist society, the idea that Finn and Poe would at least reflect some of that attitude kind of isn’t... entirely unrealistic?

I say this as a woman who had a lot of weirdly externalized misogyny and mistrust of feminism as a kid because I grew up in a bubble where I was free to express my gender however I liked, and adult women made all the decisions, and had status and value, and men were kind of just there also. I didn’t actually understand the feeling of not being default, of being Other, of being secondary, and when I was first exposed to feminism I was angry because I didn’t like to be told that I was oppressed. I didn’t want to be oppressed, so don’t you dare imply it could happen! I grew up without a lot of the social pressures women get, and now I actually recognize male-privileged attitudes ingrained in myself. I feel like aspects of masculinity (but certainly not all of them!) are just the gendered appropriation of Human Default, which women would default to if they weren’t pressed out of it (and aspects of femininity are extremely Human Default too and denying them to men is very damaging to them). So Finn and Poe being written by a white man trying to make them Human Default (or at least Male Default since gender disparities do exist in SW), could come across as infused with whiteness. Also humans in SW have heavy privilege over aliens and droids so they probably would act like privileged people when you think about it......

Still, I don’t and can’t begrudge anyone (particular a person of color) who doesn’t like that, because it’s probably not relatable and it’s missing a lot of nuance and perspicacity that a writer of color would infuse the situation with, in portraying a fictional fantasy world that’s relatively blind to race to an audience in a racialized society. You have to balance both fiction and reality.

White writers sort of have to learn that. A writer wants to engage with their audience authentically, and writers can’t get that if they pretend their audience won’t be hyperalert to racial dynamics. “But I didn’t know people would have that reaction” yes you did, or you should. “But I want to live in a world where people don’t have to have that reaction since it’s coming from so much suffering and injustice” me too buddy, but one movie can’t change everything overnight. Obviously if you care about marginalized people, what you want to do is make them feel appreciated and comfortable for the space of time your movie is playing. But I understand you do also want to write in your style. All the characters you write will be coming out of your own heart, that’s inevitable.

It feels like the “why didn’t Johnson listen to the actors” anger is because people kind of wanted to see the actors’ takes on the characters, so they didn’t have to see Rian Johnson interiority throughout all of them. Except... the thing is. If Lucasfilm really begged Johnson to write and direct their movie, he’s allowed to put Rian Johnson interiority into it. Even the characters of marginalized identities -- ultimately, wanting to project onto and empathize with characters of color is not at all bad. Johnson feels like Rose is his self insert. She’s a woman of color, and he specifically wanted KMT for the role. He felt like he could deeply relate to this character. It’s not that he identifies as an Asian-American woman, it’s that he did actually think that distinction wasn’t a barrier to relatability. (On top of that, I think Rose is written to have some backstory elements that strongly parallel her actress’s Vietnamese heritage, and I think it’s a pretty big deal and I wish more people cared about that but we’ve been brainwashed to forget the Vietnam War I guess.)

White writers do need to take care not to project too much of their own interiority onto characters of color, to the point where audiences feel like they’ve been pushed out, like they’re seeing someone who looks like them but clearly is not like them on the inside (an uncanny, unnerving effect). But at the same time, I can’t imagine writing that doesn’t come from the writer. And white writers absolutely need to project onto and relate to characters of color. It’s always going to be a mess and there’s a lot of work to do to get it right but the alternative where you’re convinced you could never relate is not at all better.

TL;DR: Rian Johnson did indeed fall into a white male writer pitfall, but I think it’s not malicious and it’s also both problematic and potentially a good thing. Also JJ Abrams basically did the same thing it’s just that he didn’t have to write “overcome my fatal flaw” arcs for Finn and Poe.

Johnson also definitely put a lot of work into prioritizing female perspectives and female fantasies and female wish fulfillment and female POV, and I think (as a Female... or. something approximating female lol) the film is a lot better about it than any other Star Wars movie to date. Or that may be because he sat down with Carrie Fisher for hours and hours brainstorming ideas and took her suggestions seriously enough to have notebooks full of them. I imagine he should have done the same with non-white script doctor but when it came to script doctoring and a deep connection to SW, Carrie was kind of without equal.

#my post#the last jedi#actually critical as well but not tagging that lol#probably incomplete understanding of race in media due to my privilege#but like I suppose as a white gender-weird person I do have the advantage of like#detecting when something is meant to be relatable to a certain kind of white man?#the thing is I was relating super hard to poe in the holdo arc#and relating to finn and rose in equal measures in the canto bight arc#not like as if they were truly me but I was having the requisite sympathetic projection that I'd expect for a likable POV char

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 2

[Previous] [Contents] [Next]

Sumiko and I left the office as soon as our shift had ended.

I kept blabbering and asking questions about this group meeting event and why she chose to let this be the final resort of her dating life as a joke. I don’t think she wasn’t really happy with my joke – but in all seriousness, I was never really expecting her to be the type of woman that goes for this sort of clique, that’s why I was quite surprised earlier.

She got irritated at me, then aimlessly answered my queries, explaining how it was something to experience at least once and drop it if it’s not her thing.

And after what she told me, I started to think about the whole thing from a different perspective too…

I also have never done this before either, so what’s my real reason to not like it? I can’t not like something if I haven’t experienced it, right?… I can’t be too quick to hate on things that I have no prior knowledge over – that should be the basic logic. Subsequently I thought that maybe, I was being a bit too judgemental over this stuff and should just ease down a bit.

Thus I decided that if I gave this a chance, something good might happen as an outcome without me expecting – and that was the type of encouragement I gave to excite myself!

So via public transport, we were dropped off at the bus stop and walked to the chosen restaurant.

Once we arrived, I eyed the place up and down to process whatever was in front of me. Then words trailed out when reading the banner hanging outside, “Ohh… Uh – Onigiri Miya…?”

Never heard of it. But was actually quite close to my apartment by a couple of minutes.

“Huh… What’s with that face? Ever been here or are you just nervous?” Sumiko asks.