#are known to have the possible effect of making one horribly nihilistic. to the point of giving up on life. just saying.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

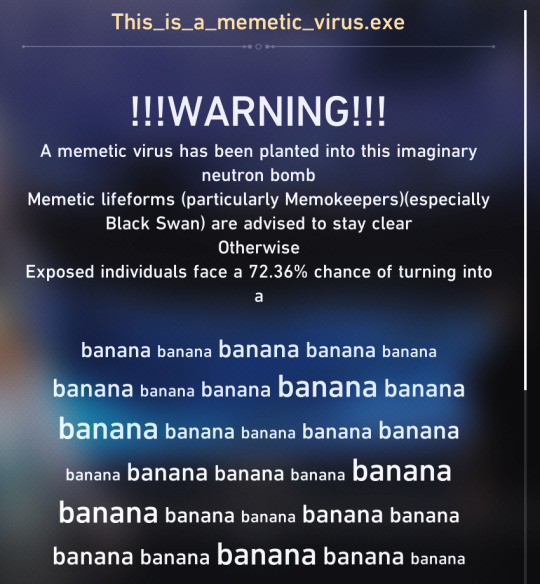

This was all the way back from the end of 2.3.

Hey Sparkle what the fuck.

#So out of left field#she didn't even anything to do with 2.6! she didn't even make an appearance!#I wonder if she had anything to do with it all or if she just knew from Silverwolf's script and is fucking with us#it's hard to tell with her jfkdjsklajd#...by which I mean I wonder if she was like playing both sides the way Reca did#I don't think she'd fully side with Primitive or anything bc people turning into monkeys doesn't seem like it'd serve her.#how are they gonna appreciate her art form like that?!#also Acheron literally just impersonating a Galaxy Ranger was enough to get her a death sentence. Sparkle is wild but she's not stupid.#And aligning with Primitive seems like a fast track to a messy execution. no one wants the Galaxy Rangers on their ass.#fun side note about the current mr. cold feet's pop-up shop event going on:#I think this Sampo really IS our Sampo and not Sparkle in disguise or anything. just that some outside influence might be fucking with him.#he WOULD have been on Penacony right around the time all this happened. and he was closely in cahoots with Sparkle herself.#and memetic viruses- whether from Penacony memoria or say maybe a meme crate unearthed out of the snow-#are known to have the possible effect of making one horribly nihilistic. to the point of giving up on life. just saying.#(don't actually know that it's much of anything but GOSH is it a lovely thing to daydream about uwu)#honkai star rail#hsr#honkai star rail sparkle#hsr sparkle#sparkle#hsr 2.3#hsr 2.6#penacony#hanabi#hsr hanabi#honkai star rail hanabi

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

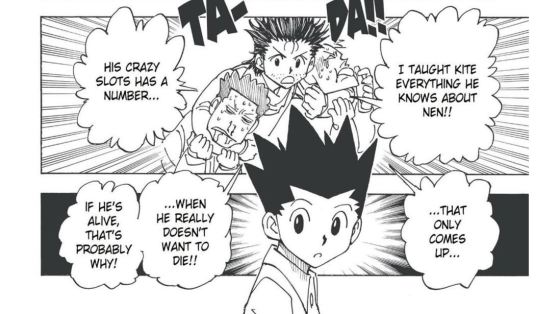

Analysis of Kite's conflicting moralities, relationship with death, and the toll reincarnation may take on one's psyche

So, today I decided to compile all the thoughts I have had about Kite's interesting worldview since the first time I saw him into one post, mostly for my own sake, really. If you're familiar with the few posts I've made, you know it's gonna be a mess, but hopefully a comprehensible mess.

A heads up, this is going to be spoiler-heavy, and very much deal with subjects of death and dying as a whole. Also, some of these conclusions are drawn from my own experiences and close brushes with death, I'm not going to go into much detail but it might get personal and definitely dark. I'm not even sure if I can call this a meta-analysis, and I'm obviously no expert, so mayhaps take all of this with a grain of salt.

Been getting into drawing lately, and during the more simple and mindless part of the painstaking process of dotting every single star in this, I let my thoughts wander through the latest part of the fic I'm writing, and I got a better grasp on what exactly made Kite such an elusive character to me.

I'm not quite sure why I got so attached to Kite. Perhaps it was the air of tragedy surrounding him, how despite his sordid past he remained still open and gentle even if outlined by a healthy dose of cynicism.

But sometimes, I think it's the fact that he is so paradoxical. He's brave, yet fears death to such a degree that creates a whole Nen ability around it, is a pacifist yet will not hesitate to spill blood for his own sake or someone else's. Despite the many ultimatums and warnings of 'I will not protect you', he gave his arm and then his life to save Gon and Killua. He approaches each hunt and battle with a clear plan of action in mind, but his Hatsu takes the form of a roulette that gives him random weapons which are never what he wants, but what he seems to need for that exact situation, which he cannot dispel without using. When he draws a weapon, the decision is locked in and his or his opponent's fate is sealed. That's why each time he dubbs his weapon a bad roll. Every time he has to gamble, he sees himself as having run out of luck. When it comes to having to choose between himself and somebody else...well, there had never been a choice. In fact his aversion to using it may feed into its sheer power that we, unfortunately, saw too little of.

Let's go over his very first appearance when he saves Gon from the mother Foxbear.

It's not hard to see the strain searching for Ging has put on him; he's rash, prone to anger and punching a child for daring to get into trouble. In his mind, he's failing at his most important task, has not yet earned the right to call himself a hunter despite being in possession of his very own hunter license.

After killing the mother Foxbear and raging about having done so, he says this interesting line:

So yes, he finds killing for any reason rather irksome as most would do, yet I think something deeper caused him to absolutely lose it in this scene:

He had not been aware of Gon's identity, and despite being an animal lover and a naturalist, he made a choice to save the human instead of allowing nature to run its course. In fact, he says: 'No beast that harms a human must be allowed to live.'

How does one weight one life against another? How is the worth of it determined? The value of life... an impossible choice he's faced with and a choice which he seems to regret to some degree.

The Foxbear cub.

Here, he's speaking from experience, a tangible loss he has felt himself, and a hard and bitter life he does not want to impose on the cub.

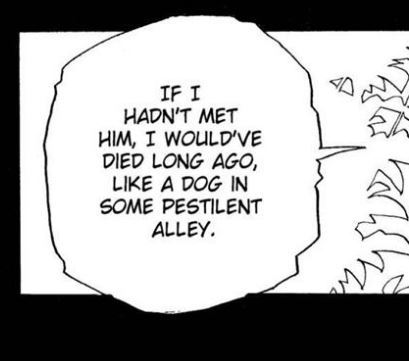

His backstory is exclusive to the 2011 anime adaptation but there are hints alluding to it in the manga, for example, the fact that he does not seem to know his birthplace, or:

The choice of words is chilling.

Reading between the lines, one could draw the conclusion that he is an orphan. Something supporting this hypothesis is how he visibly deflates after Gon tells him his parents have (presumably) died.

So we see he is willing to go against his own moral code of not killing as to not doom another living being to the life he led, a lonely, hopeless existence that could barely be called one. He saw it best to put down the cub rather than leave it to die a painful, slow death.

The reason Kite himself isn't as cynical and cold-hearted as one would be after witnessing cruelty in its rawest form is those small crumbs of human kindness which he may have found in Ging.

It was not only a chance at an honorable life being Ging's apprentice gave him, but it also 'saved' him from being broken and twisted into what he hated and worst of all, death.

If we take that one minute of backstory as canon to his character-which I find myself inclined to do- these quirks of his make much more sense. He lived on the run. He lived on the knife's edge between giving up or pushing forwards. He lived as so a wrong move could be the difference between survival and the end.

Between rock and a hard place creates a mentality of black and white, absolute good or extreme evil, this or that. Except in reality, it's much harder than that. Deciding who to save and who to strike down is a heavy burden to bear.

It's almost easy to see how struggling to keep surviving could lend itself to a crippling fear of death and subsequently developing a Nen ability which once more goes against his own moral code in order to give himself a second chance...yet something about it strikes me as unlikely when I look at it this way.

Living life knowing it could end at any moment has the opposite effect, at least for me it did. One comes to accept that it is fleeting and while not eager to let it go, when death eventually and inevitably does come, there is no fighting it.

Especially when there is no hope that tomorrow will be a better day than this one.

Frequent near-death experiences numb one's fear in a way, even if it drives them to take precautions that render it unlikely to happen again and results in c-PTSD, but still, it does. It sparks a certain nihilistic view of 'if it all can end so easily, then what's the point of it all?'

Unless there are things to live for, a sure promise of a better future, and Ging gave Kite that. When he faced the threat of losing his second chance at life:

Really, what else could lead someone to develop the ability of 'the hell I'm going to die like this'?

I think a separate event, an even more brutal near-death experience that almost cost him his life as the hunter he so strived to be set him off to develop the secret roll of Crazy Slots, what I call Roll No.0, Ars moriendi. Unlike other weapons, it cannot come up in random and is directly summoned by him, or better said, summon by his overwhelming will to keep going and hopelessness of fighting a losing battle. I don't believe roll No.3 was the weapon that allowed him to reincarnate. I've named that one Wand of Fortune, a sort of armor instead of an offensive weapon since I find it hard to believe Kite, a Conjurer, would not focus on defences as well, and I will go into both mechanisms of these weapons hopefully in his backstory.

Despite knowing this battle to be a pointless one and being acutely aware of his soon to be demise, he did not immediately draw Ars moriendi, no, he stayed back and fought for the sake of the boys, kept Neferpitou occupied until they could reach safety. We can see evidence of this in the aftermath of the battle that seemed to have gone on until dawn, a torn apart landscape only signaling a fraction of the devastation that was Kite's power unleashed. It still wasn't enough.

In the anime sub I watched, when Gon apologizes to Ging about Kite's death, Ging said a sentence that infuriated me, because it belittled the utter suffering of the NGL trio.

"He would not die in your place." (No screenshot, sorry)

And I remember practically shouting at the screen, screaming 'how could you possibly say that? Of course he did. He absolutely did die in their place. How could you not know your own apprentice? Why-'

It was only last night that it hit me why Ging would say that.

Once upon a time, maybe Kite would not have given his life for anybody under any circumstances, even if he had a way out of it all. He would still need to die to come back to life.

His Thanatophobia could be attributed to the (possibly untreated) PTSD of the near-death experience in his later life, being so certain of dying that finding himself alive afterwards drove him to never want to go through that again. He quieted his fear by creating a sort of a loophole, that even if he lost the battle he would remain. Ging remembered that, but as evidence shows, something changed. Maybe he healed a bit, perhaps growing up dulled his fear to a certain degree, but eventually when it came down to his life or another's, he didn't choose himself.

Now, I can hear you saying 'but he didn't die, so what are you going on about??' And so I reply: Yes, he is alive, but he did die. He experienced that painful, horrible moment of staring death in the eyes and thinking 'This is it, this is the end', went through the actual process of having his soul removed from his body. And that moment stretches into infinity, ten lifetimes condensed into the mere seconds before oblivion.

Dying isn't so hard if one stays dead.

It's not so easy to open one's eyes and find oneself alive again after that, no matter how much that is the heart's desire. It's difficult, nigh-impossible to reconcile with life and walk amongst the living when everything had been so final, when death had been accepted to its fullest.

So Kite awakens, the twin of Meruem and back from the dead, his mind and identity both intact and fractured. In that he is Kite is no mistaking, yet he is not the same gentle pacifist whose first reaction upon sensing a monster's aura was to shield two kids from it at the cost of his arm.

I don't think many of you are familiar with Zoroastrian ideology, but Togashi is known for loving his religious imagery, and it's not only Christianism he derives inspiration from (evidence of which can be seen all over Kite's character and resurrection).

In Zurvanism-a branch of Zoroastrianism- there is talk of the twin spirits: Ahura Mazda -epitome of all that is good- and Ahriman -epitome of all that is evil-, the parent god Zurvin decides that the firstborn may rule in order to bring "heaven, hell, and everything in between."

Upon becoming aware of this fact, Ahriman forcibly tears through the womb to emerge first. Sounding familiar yet?

Zurvan relents to this turn of events only on one condition: Ahriman is given kingship for 9000 years, and then Ahura Mazda may rule for eternity.

Meruem ruled for 40 days, his death leaving the throne vacant for ant Kite, wearing a dead girl's face and seeming to be brewing some nefarious plan. No more is there any sign of that unrelenting pacifism and the sanctity of life he held so high, losing his own may have only served to show him how meaningless the pain and suffering he went through had been, dying only to be reborn as a member of the species that killed him. It may be that he has no desire to rule over the remaining Chimera ants or create an army of his own-

Yet I dread to think what a broken mind possessing limitless power might do to the world.

And that's it. If you made it this far, thank you for reading! If you found it interesting, stay tuned, as I think a lot and I will make it your problem.

#Cw: talks of death and PTSD#When I say I unknowingly projected onto him#I can't tell if writing this was cathartic or torturous#and I gave myself heart palpitations so this is enough for today#And yes I refer to ant Kite by he/him pronouns because misgendering him on the account of his body being afab is just ignorant#even if I think skrunkly's genderqueer af and actually wouldn't mind she/her#still i wanna push the trans ant kite agenda#So yes this is how I unknowingly picked up Kite as a coping mechanism even if out attitudes towards death are practically opposites#don't mind your grandpa trauma dumping#What I'm saying is get ant Kite therapy before he sinks the world#I love reimagining Kite as a villain and I don't know why#Kite hxh#hxh kite#kite hunter x hunter#kaito hxh#hxh#hunter x hunter#meta analysis#theories#fic rambles#Icarus waffles#Kitkat#gon freccs#Ging freecss

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

worldbuilding (lightly edited) from chat:

<Moriwen> hmmm is anyone interested in hearing me ramble about an idea for dark-au-star-wars-with-the-serial-numbers-filed-off

<Alicorn> yes I vaguely dig the SW aesthetic but it has too many serial numbers tell me how you would rid it of them

<Moriwen> okay so I want to really run with the concept of "the force is cthulhu and wants to eat your brain" probably I will call it something other than "the force" because serial numbers, for now I am just running with "magic" there is an ~underlying magical field~ to the universe. some people are born innately susceptible to it. this is not generally a good thing. it does however mean they can do magic. it's not strictly a magical/non-magical binary, most people just have close-enough-to-zero susceptibility, a few people have just enough to notice, even fewer have more than that, etc

there are three main kinds of magic you can do! #1: straightforward physical effects -- strength, jumping, levitating things, etc #2: obtaining knowledge -- foresight, scrying, premonitions, correctly anticipating what side a coin will land on or what the password to a vault is, etc #3: magic on other people -- this includes both healing stuff and mind control stuff

of course, this being glowfic, each kind of magic comes at a Price #1: using physical effects slowly transforms your body into Eldritch Horror! this does not happen suddenly, you do not levitate something and sprout a tentacle, but when you heal from an injury or when your body's cells replace themselves there is some chance of the result being Eldritch Horror instead of you. and this is proportional to how much physical magic you have ever done, so stopping using magic is not sufficient to stop the transformation, if you have ever used any you will be slowly transforming, just if you're lucky you will not live long enough to transform too much.

<Alicorn> do you have any chance of controlling your eldritchness to get cool or useful horrorbits?

<Moriwen> hmm... I think you can, yes -- but this is a Bad Idea, because that requires aligning yourself further with the magic in order to influence how it's affecting you, which then gives it more influence over you

<Alicorn> if you just don't care about your body plan you could go all in on physical magic

<Moriwen> you do lose some control of the eldritch body parts, I think like, not 100% or anything, but there is some risk of tentacles doing things you didn't intend while you're not paying attention but yes it is definitely the mildest of the effects

<Sonata (Etelenda)★> but accidental tentacle things don't include "use magic"?

<Moriwen> yeah, no, accidental tentacle things are limited to straightforwardly physical actions

#2: using knowledge effects slowly swaps out your emotions for Whatever The Magic Wants You To Feel! any time you would feel an emotion, you have a chance of instead feeling What The Magic Wants You To Feel, and the chance is proportional to how much knowledge magic you have used. and just as the Eldritch Horror body parts, if damaged, will heal back to Eldritch Horror, not to human, the magically influenced emotions don't go away -- you will slowly accumulate a roiling undercurrent of possibly conflicting emotions that probably include lots of things like "rage" and "destructive fury" and "loathing for all that is good"

#3: using magic-on-other-people (healing/mind control) slowly erodes your personality and replaces it with, yep, the magic's personality! which of course has lots of fun traits like "loathing order and beauty" and "craving to absorb humanity and all its works into your slimy power"

<Tekeler★> --which of these is 'healing yourself' under?

<Moriwen> hmm ... I think "healing yourself" falls under "super bad idea you are aligning yourself directly to the magic and giving it influence over you"

<Alicorn> so it seems like the optimal use of this magic if you aren't, like, a nihilist who super wants tentacles, or something, is to conspicuously have it and then be conspicuously willing to self-sacrifice to get shit if you have to, very Schelling and then not use it unless you actually have to

<Moriwen> [nod] unfortunately: there is no convenient "you start being able to use the magic at adolescence" thing so small children who are magic-aligned can use it and will inevitably do so at least a little before they are old enough to understand "do not use that magic" and even if they only use a little this is already bad news because stopping cold turkey once they're old enough to understand isn't good enough -- with the first two types of magic you'll continue gradually getting corrupted, and with the third you've got potential for the magic directly influencing you to use more

<Alicorn> hm this also disincentivized prolonged magic fights. if you are going to be in a magic fight you aim for lethality immediately, you don't want to be in several magic-or-die situations over the course of an entire interesting fight scene. there's no hard cap, so it's probably difficult to impossible to arrange "do lots of useful magic, then die", because the magic will change your mind if you agree to that and defend you if someone tries to enforce it once you are at the point of no longer trying to ration, you are basically A Dangerous Monster are they cooperative dangerous monsters? are they dangerous monsters with foresight, do they kidnap magic babies and encourage them to be tentaclebabies

<Moriwen> they are loosely cooperative with each other -- like, you can't sic'em on each other, they won't fight -- but they are underwater with conflicting emotions and under the influence of something Distinctly Not A Person, so they don't do a lot of sophisticated teamwork and you're not going to have any luck negotiating with them you occasionally get dangerous monsters with foresight, especially if someone's used a lot of type-3 and not much type-2 magic, but for the most part they do not plan that elaborately

so there are I think in this civilization four main outcomes for magic people:

(A) if you are not very magical, and did not use much magic as a child, you can get away with joining a basically-monastery and meditating a lot and trying to avoid intense emotions that you could get stuck with corrupted versions of and not going near any weapons and having a nonmagic supervisor keep a close eye on you to make sure you're not going eldritch

(B) if that sounds unlivably awful, or you are very magical, or you've used too much magic already, the (*cough*Jedi*cough*) order of monks will at your request euthanize you (and can probably do it painlessly unless you're already sufficiently corrupted that they have to prioritize "effectively" instead)

(C) if (A) sounds unlivably awful or you are very magical or you've used too much magic and you don't want to die, or if you're feeling particularly heroic, you can volunteer to be a (*cough*Jediknight*cough*) magic user! This is a horrible idea and you should not do it. You will have a short life in which you are very closely watched for corruption and taught the best known management techniques for it and directed by your non-magical mentor how to use the absolute minimal amounts of magic possible to get good effects. And then once you are sufficiently corrupted that it's too dangerous to have you use more and risk your getting too corrupted to easily defeat, they will euthanize you.

(D) if you are unwilling to comply with (A), (B), or (C), or if you get too corrupted too fast for the monks to find and recruit you first, or if you attempt to hide you are magic and so proceed to become slowly corrupted without an excellent support-and-supervisory system, you will end up as an Eldritch Horror! These are why (C) needs so badly to exist in the first place. They are more or less totally under the sway of the magic and go around being eldritch and horrible and wreaking havoc, and are basically impossible for non-magic-users to take out, because they can use magic freely within their basic capabilities!

There are kind of a lot of (D)! Most of them have been driven out of the populated regions by the coordinated efforts of the not!Jedi monks, but, like, magic has been around forever, the monks have not, the eldritch horrors had a head start. And of course new ones crop up in the populated regions every so often, even aside from the ones that are always trying to invade from the dark gibbering outer reaches.

so we have, essentially, (A) the Jedi agricorps, (B) death :P, (C) Jedi Knights, and (D) the Sith. Except all of them are horrible options.

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

3

TOWARDS AN ECOLOGY OF LOVE

(June-July, 2020)

“Let’s face it. We’re undone by each other. And if we’re not, we’re missing something.” -Judith Butler

Fire and Mourning I’m shaking. The sun is heavy on my neck and the crowd seems to shiver in flexed anticipation. The anger running through the protestors is hot like a spider bite. The chants have all the usual words but today they sound like a new language, pulsating with a rhythm as unmistakable as it is unknown. Tears and sweat and names. My mask is damp and stale, dank breath and odor-eliminating chemicals wash back down my throat with every syllable. Then, the sun goes white and the police, without warning, jump us. Screaming. Protestors and cops collapse into blue knots, plastics are tangled up. Fists, legs, batons. Water bottles fly. I find my partner and pull her away from the cowering cop at her feet. A horrified girl in a faded tye dye top pushes her way forward, shrieking pleas for de-escalation. But we have slipped into a dark beyond, out of reach of such luxuries as deliberation, planning, and respectability...

The scuffle ends with several on our side arrested and many more beaten bloody. Whoever has the megaphone manages to march us across the city for several hours, but the veil of control has been torn. Paint goes up on every wall in the city to elated hollers. Squad cars are destroyed, at least one burns. The police are now eerily absent. We march back towards the towering art deco skyscrapers at the city’s center, monuments to abundance we’ve never known. There, a wall of riot cops awaits us. Gold light catches the edges of a gilded cupola and stains the cream colored marble like marmalade. The city would be so beautiful, if it were ours. Cracks, screams, gas. The next few hours are a blur. Running, terror, bravery, fire, hope, inspiration, ingenuity. The police deploy dispersal technology more than once but to no avail. The remaining mass of people have become something else. At times, to the police’s genuine horror and visible surprise, we push them back with a barrage of water bottles, debris, banana peels. When necessary, we melt back into the city only to reappear again moments later, one block over. At some point, word gets around that all but two of the bridges had been raised and we were trapped...

A firework rips through the police line to cheers. The cops swear and slip. Strontium carbonate burns bright red streaks across my eyes and whispers out. The police fracture into a million tiny pieces. An ATV donuts wildly and peels off straight at the jagged, trembling row of officers. Dumpsters are moved to prevent ambush, coordination flows like a river, without words. Motorcycles go up on one wheel. Eventually, we realize a curfew has been set, effective in twenty or so minutes. Someone has mounted a horse. There’s nowhere to go and it begins to feel as though the police are trapped down here with us, as opposed to us with them. Windows are smashed as darkness falls. The man on horseback charges forward, into the black and orange of the night...

The police would go on to make over 400 arrests by the end of the night, with over 80 officers reporting injuries in what turned out to be one of many, simultaneous riots taking place across the country. What I saw that night had previously been unthinkable to me. The city had flexed its anarchic muscle after decades of slumber and found it was still strong, and the police, shockingly weak. I remain struck, too, by the frantic way the police attacked. No one could be surprised at the lack of provocation nor the lack of shame, but what I did not foresee was the palpable panic emanating from behind their shields. And I am beginning to understand why we scared them so–we had come to mourn. Not to “resist” or to march or to curse DJT, but to mourn. We were there to grieve the ungrievable, to say the unsayable: that we will no longer accept no-life, we will no longer accept bare-life, that we are indeed connected, that we are hurt by this loss and every other, that we will give them a fight, that we will defend ourselves and each other, that this order is no order, and, that we deserve so much better. Our mourning was a radical negation of a system that tries to maintain an unnatural space between us, that seeks to limit experience to individual (or consumer) experience, that attempts to constrain feelings to personal feelings. Our mourning was dangerous. The cops were right. And their panic was not just at our finding strength in each other, but that they found themselves with none...

Judith Butler describes mourning as a process of transformation as well as one of revelation, in which we are exposed as being bound up in each other, our “selves” products of our relationships to each other, socially constructed, interdependent. When we lose, we change, because what we were was dependent on what we lost. This state or process of mourning makes possible the apprehension of our interlocked-ness, our interwoven-ness, in which “something about who we are is revealed, something that delineates the ties we have to others, that shows us that these ties constitute what we are, ties or bonds that compose us… perhaps what I have lost ‘in’ you, that for which I have no ready vocabulary, is a relationality that is composed neither exclusively of myself nor you, but is to be conceived as the tie by which those terms are differentiated and related.” There is no you and there is no me, rather there is a you-me and there is a me-you.

Can mourning be the only site of such apprehension? Mourning is an extreme condition, contingent on loss and suffering, a painful process, where these links that compose us are stretched and then snapped. This severance is gradually accommodated in a transformation. However, these links to one another just as much exist before this point of breakage, before the moment of loss, and there is then no reason they cannot be pulled at, plucked and strummed, like the strings of a guitar, until that which irrevocably binds us to each other achieves a resonance or vibration that no power can obscure. This resonance, this song, this elevation of our bonds to the level of naked visibility, could usher in a moment of universal recognition of our interdependence, our interconstitution, our intervitality, that, if properly politicized, could hold the key to our liberation from the prison of capitalist relations.

The stubborn fact remains that these links, these ties, are currently obscured, mystified, hidden, or outright suppressed and attacked. We cannot politicize our ties if we cannot see them and we cannot see these ties because we are told at the level of ideology that they are either not important or, more maddeningly, that they are not there. The integrity of these links is further corrupted and degraded by the rising power of debt. Perhaps most troublingly, we humans are being transformed by supposedly liberatory technology into unfeeling components of a networked machine, incapable of empathy or solidarity. It is this final development that, when complete, could represent a point of no return, a total obliteration of the ties that both constitute us as individuals and define our humanity. If this subsumption of the human by the technofinancial machine is allowed to continue, there will soon be nothing left to mourn.

Capitalist Realism and Neoliberal Ideology Ideology is the first obstacle we encounter when tracing the gap between us and a resurgent solidarity. Neoliberalism is the dominant ideology in our time because of the hegemonic power the neoliberal bloc has accrued over the last five decades, infiltrating every level of government, media, academia, and economics. Hegemony allows the ruling class’ ideas about society to appear as if they are bubbling up from within each of us, as opposed to being imposed on us from above. As Nancy Fraser succinctly puts it, summarizing Gramsci, “hegemony is [the] term for the process by which a ruling class makes its domination appear natural.” Today, neoliberal hegemony makes the dominant ideas of the ruling class inescapable and nearly ubiquitous and yet, uniquely difficult to distinguish. A pervasive atmosphere of social-darwinism, savage competition, short sightedness, and nihilistic indulgence has become our ambient common sense. Hopelessness becomes a sort of wisdom, trust in each other and in the future becomes naivety. As Mark Fisher states in his book, Capitalist Realism, “The prevailing ideology is that of cynicism.” Nothing is possible, and it’s foolish to believe otherwise. It could be said that the apprehension of our ties to one another is the apprehension of the political, but the political under neoliberalism has been effectively neutralized. Neoliberal ideology attempts to situate us in an eternally post-political moment. The future is no longer contested space, it was sold to the highest bidder long ago.

Reinforcing this ideology is a material precarity that has come to make up the texture of life for the service underclass of neoliberal society, as well as more broadly characterizing the spirit of work for all in the new economy. Solidarity gives way to brutal competition, coworkers become competitors, friends become networks. No one job is enough; we are constantly seeking the next opportunity for advancement, overlapping work schedules clash, disaster looms, familial relations fray, neural stimulation overloads and feeds back into wave after wave of crippling anxiety, at best. At worst, violence. This precarity and its accompanying anxiety, while horribly traumatizing to the overwhelming majority of people, has very advantageous qualities from the perspective of capital. In an interview with Jeremy Gilbert, Mark Fisher points out that, “anxiety is something that is in itself highly desirable from the perspective of the neoliberal project. The erosion of confidence, the sense of being alone, in competition with others: this weakens the worker’s resolve, undermines their capacity for solidarity, and forestalls militancy.” At multiple levels of our waking (and dreaming) lives, the idea that you are not only alone but in eternal competition with every other person is reinforced, and the effects of such a social arrangement can be seen in the rapidly spiking suicide tally, spectacular violence, pharmacological dependence and abuse, and the numbers of people reporting depression, burn out, and especially loneliness.

We see this “lone-wolf” mindset very clearly when we consider the popular cultural output of Western capitalist society. In the same interview, Fisher points to the rise of hyper-competitive game shows as a manifestation of the social darwinism at the center of neoliberal thought. These aptly named reality shows, like Apprentice and Big Brother, revolve around “individuals competing with one another, and an exploitation of the affective and supposedly ‘inner’ aspects of the participants’ lives.” He continues by pointing out the way in which reality television feeds back into and constructs the reality of its audience: “It’s no accident that ‘reality’ became the dominant mode of entertainment in the last decade or so. The ‘reality’ usually amounts to individuals struggling against one another, in conditions where competition is artificially imposed, and collaboration is actively repressed.” One could endlessly list the names of these types of programs that have proliferated in the last decade or two in America, many with great commercial success.

Another trend emerging in the superstructure, more or less concurrently, is a sort of melancholic self-awareness of the brutal and total competition our lives have been reduced to. We can most easily locate this trend in music. It can take the form of a depressive acceptance of the shallowness of our relationships or perhaps a declaration of exhaustion, a celebration of outright antisocial behavior, or submission and defeated withdrawal. Oftentimes, these songs make heavy reference to a handful of favored barbiturates, opiates, or dissociatives. We can most readily see this in the relatively recent rise in popularity of “xanax rap,” as well as in some drill and trap music (21 Savage or Chief Keef come to mind). On the other end of the musical spectrum, we could look to the resurgent popularity of emo music, especially the hyper-personal, heroin addled, lo-fi bedroom varietals (artists like Teen Suicide or Dandelion Hands have amassed millions of streams and a cult following without the backing of a major label).

But even the ostensible “winners of the game” are not insulated from the melancholic deterioration of the social fabric. One song in particular off of Kanye West’s manic 2016 album, The Life of Pablo, stands out for the stark clarity with which it addresses the crisis of relations brought on by the neoliberal economy. On “Real Friends,” West laments the way his friendships have been transformed. But one gets the sense upon listening that this isn’t just the story of a star narcissistically complaining about the way people from his past attempt to use his name or piggy back on his success; that’s simply the context. The song is, at its core, about how the insatiable hunger that neoliberalism forcibly inscribes in each of us, the end result of a decades long process of privatization of risk, erodes friendship, sabotages love, and destroys family. “Couldn't tell you much about the fam though/ I just showed up for the yams though/ Maybe 15 minutes, took some pictures with your sister/ Merry Christmas, then I'm finished, then it's back to business.” There’s no time for family gatherings. Time is money, there’s not enough of it and there never will be. Your friends are simply biding their time, lying in wait for a chance to use you for their own advancement. There’s a paranoia here, but as a fellow participant in the same savage game, you understand this paranoia to be justified. “Real Friends”, while rightly lauded for its “truth” and relatability, unfortunately functions as another whirring cog in the propaganda apparatus, normalizing the growing space between each of us and presenting cynical, opportunistic relations as “just a fact of life.” West seems to echo Fisher’s bleak assessment that “the values that family life depends upon – obligation, trustworthiness, commitment – are precisely those which are held to be obsolete in the new capitalism,” but without the critical edge. Our ties to one another, if they are acknowledged at all, are deemed simply useless and perhaps even a little bit risky, much like an appendix: an archaic, forgotten form that serves no useful purpose for today’s human, but can sometimes lead to infection. Bourgeois art, even art able to successfully express the darker qualities of the capitalist system, only reaffirms the status quo and further entrenches the ruling classes ideas about our relations to one another as the de facto common sense.

Debt and Bad Faith We next see these same social ties corrupted and corroded at the level of economics. The rise of credit, debt, and finance has transformed interpersonal relations under capitalism so as to be dominated by bad faith and suspicion. It’s quite common today for people to be heard bemoaning the transactional nature of relationships. But what exactly does this mean, and from where does our compulsion to calculate the incalculable emerge? Cartographer of the debt state, Marizzio Lazzarato, at first seems to echo some of Fisher’s observations in his 2012 book, The Making of The Indebted Man, pointing out that, “under conditions of ubiquitous distrust created by neoliberal policies, hypocrisy and cynicism now form the content of social relations.” Lazzarato describes many of the same symptoms of capitalist realism, but forgoes any discussion of ideology in favor of a somewhat more concrete causal chain: the creditor/debtor relationship.

In America today, debt is nearly ubiquitous and ownership has become an optical illusion, a disappearing act. Everything can be paid for later. Consequences can be deferred indefinitely with a solid line of credit. In this way, debt is sold to us as freedom, or perhaps more specifically, as opportunity. But of course, as is true of most things under neoliberalism, what is claimed and what actually is are two very different things. Lazzarato explains that debt can be understood as an obligation over time, both a promise and a memory. As a result of decades of neoliberal policies, personal debt has exploded in the United States and around the world. Personal debt acts as a form of social control, ensuring economic integration and encouraging one to prioritize “solvency.” This “solvency” usually manifests most visibly as an aversion to risk, a self-policed austerity, and general conformity so as to make good on one’s future obligations (to pay the debt).

The compulsion towards solvency appears in our personal lives in a wide variety of ways, unique to our station and interests. In some ways, even a grade schoolers fixation on popularity could be called a manifestation of debt society’s preoccupation with solvency. Obsession with outward appearances and “who is hanging out with who” is perhaps a primitive understanding of debt as a social relation. Even before taking on personal debt, children are shown that one must appear to be a person who will make good on their debts and thus be worthy of lending or more generalized opportunity. Parents often encourage their children’s involvement in a wide variety of extracurricular activities, not because their child is passionate, but largely for involvement’s sake. In debt society, being a well-rounded, “whole” person makes you deserving of investment. What was once your private activity or leisure time is now folded back into the economic as debt society implores you to constantly work on yourself and, with the development of social media, to publicly exhibit these favorable tendencies in yourself, proving over and over again that you are indeed viable, solvent, and a safe and potentially lucrative investment opportunity. In my own professional life as an artist, I am expected to broadcast or signal my practice’s (and thus my own) solvency at all times. Instagram has become artists’ preferred medium for the transmission of these displays and through “stories” and posts, we carefully curate an image of productivity, attendance, viability, and social integration and ascendence. We outwardly project the idea that we’re working hard in our studios, that we’re networking properly through studio visits and the obligatory cruising of exhibition circuits, that we’re reading the right books and thinking not just critically but, correctly, and that our work is already being collected and invested in, all in order to facilitate personal access to future opportunity.

In other spheres of life, this process plays out in much the same way, albeit with some largely aesthetic quirks or differences. For the cognitive worker, already a member of the upper-middle class, perhaps one shares their numerous camping excursions to impart a sense of their connection to the earth and adventurous spirit. For the service class, perhaps it appears as a public chronicling of their work ethic and commitment to upward advancement, even at the expense of pleasure or non-material enrichment. The public deferral of pleasure can be used as an expression of one’s solvency, especially and tragically among the lower classes of debt society. We begin to see here that these performances or projections may have a class character to their manifestations. For the lower classes, one is expected to showcase dedication to advancement by highlighting a self imposed austerity. For the higher classes, one is expected to prove they’re not only deserving of their opportunities but are using them properly, to further improve themselves and become a more complete person. All of this theater is directed at an audience of one: capital. Much of what constituted life has been degraded to the level of rote performance, of literal Virtue signaling. When our desire for autonomous self fulfillment and development returns back to us, now as a directive of capital and as a measure of solvency, this is alienation completed. This is the total commodification of the human and of social life.

Over time, solvency comes to stand in for morality, a good person becomes a person who will “make good” on their promise to pay. We grow suspicious, slow to trust, and it’s generally considered “smart” to remain somewhat distanced from your fellow worker, ready to cast them aside at a moments notice, either because a new, more lucrative opportunity for exploitable relations has arisen or there is a sense that somehow your current relationship could hinder or damage your accumulation of social capital or even your access to real capital in the future. People become containers of undifferentiated “risk.” While this reduction of friendship to an economic calculus is reinforced and normalized by ideology, it can be traced directly back to the rise of credit and finance. Lazzarato explains that,

“the trust that credit exploits has nothing to do with the belief in new possibilities in life and, thus, in some noble sentiment toward oneself, others, and the world. It is limited to a trust in solvency and makes solvency the content and measure of the ethical relationship. The “moral” concepts of good and bad, of trust and distrust, here translate into solvency and insolvency… In capitalism, then, solvency serves as the measure of the ‘morality” of man.”

This imposition of the debtor-creditor relationship and its associated thought processes onto our social relations has had a disastrous effect on our capacity for solidarity and friendship. This reduction of trust to an arithmetic evaluation of solvency amounts to an outright attack on our bonds, our interdependence, our intervitality, well beyond the aforementioned psychological denial and ideological mystification. Debt corrodes and transforms our bonds, attempting to rob them of their revolutionary potential and leverage them towards our own management or government; our ties morph from the seeds of our liberation to become a critical node of control. This reduction, the mathematization of social life, made possible and prefigured the transformations yet to occur at the hands of computer technology. This conversion of the unquantifiable into the numeric perhaps primed us for a world governed by ones and zeros, binary options and no choices; a world of mathematically infinite opportunity but evaporated possibility, a world engulfed by digital mirage, where government has been exported and grafted into the minds of the governed, implanted by credit and sutured by tech. Credit does not simply reduce friendship to a transaction, but (especially in an environment of technologically networked acceleration), facilitates the dissolving of trust, morality, and love into accounting, of real and perceived solvency, of calculation, and of preformatted corporate connectivity. Debt catalyses our transformation from living, affective, creative, unquantifiable singularities into cold, accountable, predictable, math. Interchangeable parts. Fiber optic cable, mildly inconvenienced by our flesh’s relative lack of conductivity. Its need to piss, shit, and fuck.

Finance, Transformation, Meaning It could be argued that a paradox emerges when this drive towards a total accounting arises at the same time as the fateful decision to free the United States dollar from the gold standard is made. At once, ideology and the rise of debt reduces relations to calculations, everyday life to math while the total detachment of the sign (money) from the referent (gold) unchained valorization from the real world, opening up fictitious space for fictitious valorization. The paradox lies in the fact that any truth once found in accounting was obliterated by Nixon’s decision while workers are now compelled by debt to recognize and submit to the quantifiable, the countable, as the only truth, the last truth. Where does this false truth get its power? What resolves this contradiction? Franco “Bifo” Berardi answers: “ Strength, force, violence.” Truth is an illusion and we are forced to adhere to finance’s directives not because there lies real meaning for us in the numbers or that we will one day crawl out from under our mountains of debt, but because we are coerced with violence: the violent expropriation of the means of our own reproduction, and the violence of everyday life, with its terrorist police and torturer bankers, predatory usurers and rapist landlords. With finance unleashed from the realm of the corporeal and the corporeal lashed firmly to the mast of the sinking ship of the mathematic (by debt), the real world becomes a prison without walls to the worker at the same time that the real world (and all of its inhabitants) becomes a trivial nuisance to capital. This sets the apocalypse in motion. As Berardi puts it in his 2011 book, The Uprising,

“When the referent is cancelled, when profit is made possible by the mere circulation of money, the production of cars, books, and bread becomes superfluous. The accumulation of abstract value is made possible through the subjection of human beings to debt, and through predation on existing resources. The destruction of the real world starts from this emancipation of valorization from the production of useful things, and from the self-replication of value in the financial field. The emancipation of value from the referent leads to the destruction of the existing world.”

As the world becomes simultaneously not enough (for capital) and too much (for the indebted people), the digital emerges, like a messiah, here to save humanity from reality and capital from its limitations. The digital promised humanity new horizons of democracy and liberty, and promised capital boundless capacity for speed and integration. It made good on one of these promises. Flows picked up speed and globalized and continue to do so to this day. Humanity, instead of being liberated by the emergence of digital technologies, has been forced to undergo a painful transformation to accommodate their proliferation in the workplace. Temporality veers wildly towards the unnatural and communication favors the simplistic as, “in the field of digital acceleration, more information means less meaning. In the sphere of the digital economy, the faster information circulates, the faster value is accumulated. But meaning slows down this process, as meaning needs time to be produced and to be elaborated and understood. So the acceleration of the info-flow implies an elimination of meaning.” Berardi describes this transformation as a paradigmatic shift at the level of social relations (and perhaps even at the level of biology), away from earthly conjunction and towards a synthetic connectivity, asserting that, “the leading factor of this change is the insertion of the electronic in the organic.” He elaborates:

“The spreading of the connective modality in social life (the network) creates the condition of an anthropological shift that we cannot yet fully understand. This shift involves a mutation of the conscious organism: in order to make the conscious organism compatible with the connective machine, its cognitive system has to be reformatted. Conscious and sensitive organisms are thus being subjected to a process of mutation that involves the faculties of attention, processing, decision, and expression. Info-flows have to be accelerated, and connective capacity has to be empowered, in order to comply with the recombinant technology of the global net… connection entails a simple effect of machinic functionality… In order for connection to be possible, segments must be linguistically compatible. Connection requires a prior process whereby elements that need to connect are made compatible.”

This change in us happened gradually, perhaps before a personal computer ever entered a private residence. In fact, corporate strategists came to favor a “networked” management structure long before the literal network ever came online. As I have suggested above, the submission of the world’s populations to the violence of debt helped inaugurate and later enforce this transformation in us. This technobiological evolution, this digital mutilation we are undergoing, represents the most serious threat to the ties that constitute us. Whereas ideology functions merely as a denial and a mystification of our ties and debt serves to corrode and corrupt our ties, the rise of digital technology amounts to a direct attack on the bodies sustaining our ties. Computing technology threatens to completely obliterate our capacity for empathy and solidarity, disintegrates our ability to conjoin, and dissolves our awareness of the sensuous: the lifeblood of our interconstitution, the source of our humanity. Berardi explains that, “In order to efficiently interact with the connective environment, the conscious and sensitive organism starts to suppress to a certain degree what we call sensibility… i.e. the ability to interpret and understand what cannot be expressed in verbal or digital signs.” Our language narrows, our horizons darken, social order breaks down and meaning gives way to chaos. Sensuous conjunction becomes networked connection, singularity becomes compatibility, and poetry becomes a glitch.

This inability to conjunct, this physical denial of our mutual ties, this loss of the sensuous and the natural, affects us on the level of meaning. It manifests itself as a ghostly trauma. We are haunted by the deep pain of the spectral loss of that which we were never able to clearly distinguish, its form only evident in a wavelength of light just beyond our eye’s ability to perceive. We feel the vague weight of our ties to one another only as an atmospheric depression, a potentiality foreclosed upon, now only existing as a lost reality, a sad fantasy of a life with others. This great lack is one potential starting point from which we can begin to retrace our lost ties and construct some semblance of meaning in this global superstorm of swirling info-chaos. Franco Berardi says as much in his 2017 book entitled Futurability, articulating that,

“pain forces us to look for an order to the world that we cannot find, because it does not exist. But this craving for order does exist: it is the incentive to build a bridge across the abyss of entropy, a bridge between different singular minds. From this conjunction, the meaning of the world is evoked and enacted: shared semiosis, breathing in consonance. The condition of the groundless construction of meaning is friendship. The only coherence of the world resides in sharing the act of projecting meaning: cooperation between agents of enunciation. When friendship dissolves, when solidarity is banned and individuals stay alone and face the darkness of matter in isolation, then reality turns back into chaos and the coherence of the social environment is reduced to the enforcement of the obsessional act of identification.”

Friendship is a prerequisite of meaning and thus a necessary precondition for the revolutionary sloughing off of the mummified husk of capitalist production. But friendship is impossible in an environment of distrust, cynicism, and bad faith. It follows that our immediate goal must be the careful fostering of those preconditions of friendship, the nurturing of an environment of trust and good faith, the development of an ecology of love. Our high level of cognitive connectivity could present an opportunity, but only as long as that connectivity is then able to be elaborated into actual bodily solidarity. Anything short of that is counterrevolutionary. The question we now turn to is one of action: how can we overcome the logic of finance and debt to reactivate our dormant sensibility and the inherent power in friendship? Is there a way of circumnavigating or outright obliterating the ideological, economic, and technological barriers to our coming together, our joyous re-union? And can sustained cultivation of the aforementioned preconditions of friendship result in a lasting apprehension of our ties to one another and the ensuing resurgence of the political and the possible?

Loving Giving So far, we have seen how the development of neoliberal capitalism and its associated technologies has functioned to rob us of our humanity, our interconstitution and intervitality; how it denies and openly attacks our ties to one another, and how, unchecked, it may transform us physiologically beyond any ability to return, where there is no longer a me-you and a you-me, but a you and a me that does not meet and mix; solitary confinement perfected. By reading Fisher, Lazzarato, and Berardi, we have identified three dominant fields of battle upon which our submission to the imperatives of capital is violently coerced and our capacity for struggle dismantled: ideology, debt, and technology. This multi-front assault upon the human and all of life is absolutely cause for despair, but is strangely also a reason for hope and a source of conviction in our practice. The immense amount of violence required to enforce the barbaric competition they call “order” is not evidence of its strength; it’s evidence of its weakness. As long as this war rages, our ties remain and another world is still possible. The day our compliance no longer requires immense ideological and psychological operations, a boundless debt prison, violent repression, and a painful, pharmacological and physiological transformation and integration into the digitized flows of capital is the day all is lost. But their war of all against all rages on and we remain human against all odds. “Life finds a way” – for now.

Technofinancial power cannot seem to stamp out the humanistic drive towards radical acts of insolvency, trust, and selflessness, even though sadly much of this drive is channeled towards frantic crisis response, trying to mitigate the damage of our system’s greatest excesses (feeding the unfed, housing and caring for the unhoused, legal support for the persecuted, etc). Even capital has, up until this point, been forced to cloak its domination in philanthropy. This is why all of the world’s arms manufacturers and pharmaceutical barons are such virulent “supporters of the arts.” But the masks are falling off and the hour grows late for our planet. Gramsci said, “The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born, in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.” A popular, and ultimately useful, mistranslation of the quote concludes ominously: “Now is the time of monsters.” And if the last decade has proven anything, it’s that the only hero we can count on is each other. Every one of us has the capacity and the duty to be both doula of the new world and vanquisher of the old one, and our salvation depends on the generalization of a hero’s bravery...

What happens to us when we share or give? Why can’t we seem to shake the old habit of altruism despite it’s utter irrationality under a system whose basic incentive structure rewards the opposite? We remain social animals despite our being governed by an antisocial ideology and we still desire love and communion despite being forcibly transformed into unfeeling, unsleeping computer parts in the automated circulation of symbols.

Giving is the main idea I want to bring forward for discussion here. It must first be said that not all giving is equal, neither in its material impact for the receiver nor in its ability to call forth our bonds from the shadows and into the warm light of apprehension. Certain acts of giving may provide immense material support for the receiver, but do little to reaffirm our ties to one another, our interconstitution, thereby unintentionally softening the brutality of capitalist production while leaving our political obligations to one another unelucidated. Whereas other acts of giving may do the opposite: forcefully affirm our ties but offer little in the way of material support, likely a key component of any act of giving that seeks to create the necessary space in the receiver’s life for proper politicization. A balance must clearly be struck, and can likely only be found through rapid and widespread experimentation, buttressed by solid theoretical and historical analysis and reflection. There also exists another type of giving, a giving that is not giving. You know this type of giving, as it is everywhere: the type of giving that asks for something in return; the type that reduces giving to an exchange; the type that requires a promise on the part of the receiver; conditional giving. This is not giving, but debt in disguise, and it must be opposed without reservation.

Already, we can begin to see the faint outline of the type of action that has potential utility in our pursuit of another world. Firstly and most importantly, giving that asks nothing in return. Giving freely and unconditionally. We can call this type of giving, loving giving. Loving giving, as opposed to conditional giving, is an act of faith and of prefiguration (of course, with varied degrees of effectiveness and vibrational intensity). It is a negation of competitive ideology, a refutation of debts logic of solvency and personal responsibility, and a rejection of the inorganic and the virtual in favor of the organic and the natural (“a century ago, scarcity had to be endured; today, it has to be enforced”). Beyond that, loving giving can be said to act as a positive affirmation of our precarity, of our shared condition and interests, and our interdependence on each other for the propagation of human life. Judith Butler makes clear that,

“...each of us is constituted politically in part by virtue of the social vulnerability of our bodies- as a site of desire and physical vulnerability, as the site of a publicity at once assertive and exposed. Loss and vulnerability seem to follow from our being socially constituted bodies, attached to others, at risk of losing those attachments, exposed to others, at risk of violence by virtue of that exposure.”

We are political creatures because of our exposure and vulnerability to each other. We are threatened by each other constantly, yet made by each other perpetually. In this way, an act of loving giving is always underwritten by the threat of violence, our looming death, perhaps at the hands of another. Death is the third party to any act of giving; violence is the notary of all love.

When we give lovingly, recklessly, irresponsibly, insolvently, and in good faith (without condition, without narcissistic recognition), the act is defined and given its shape by the other choice, the path not taken: the choice to take as much as you can get, to harm, to ask for something in return. Under neoliberalism, even ostensible inaction amounts to the de facto submission to capitalist logics. We’ve already seen how debt paralyzes us with its myopic obsession with solvency. Austerity, in some ways, can be understood as an act of inaction. There is no neutral, not anymore. There likely never was. You can act with love and bravery or you can (in)act with fear and violence. When we act in love, we create an us, and every us is predicated by an exterior, often hostile: nature, scarcity, industrialists, colonial forces, American imperialism, those who would rather we not give, that we instead sell and buy, that we exploit each other to get what we need to survive. The act of giving, then, is also an act of revelation. Giving makes sense of the world for the involved parties. It illuminates our status as both victims of a great theft and makes clear our reciprocal responsibility for maintaining the conditions where life can flourish, that we are equally culpable co-authors of our own existence. This re-establishing of our apprehension of our being bound up in one another is a precondition for any movement against the present state of things and towards anything close to communism. Acts of good faith, of loving giving, artfully designed to undercut forces of control and alienation, to debunk competitive ideology, to dismantle logics of debt, and to negate our subsumption to the digital, carve out the revolutionary us by establishing a hostile exterior and simultaneously create an atmosphere in which trust and friendship can flourish, where a return to the sensuous and to each other is possible: an ecology of solidarity and of love.

Without a doubt, it will absolutely take much more than acts of loving giving to overthrow capitalism. The importance of a diversity of tactics has been theorized for far longer than I have lived. In that spirit, I feel I must make special emphasis of the fact that during the aforementioned George Floyd riots in late May, all of the bad faith, mistrust, selfishness, and suspicion of one another was instantaneously, albeit fleetingly, abolished. Solidarity was revealed among total strangers, power erupted between and within us. Our ties to one another, despite our obvious differences (race, neighborhood, class), emerged with astounding clarity and the role of the state in enforcing capitalist relations could not have been made more plain to everyone downtown that day. Challenging police power, refusing to disperse, asserting our right to mourn as well as our willingness to get beat up, gassed, arrested, or worse (to give all?) in order to do so, risking social insolvency or financial devastation for a chance at communion, these are forceful enunciations of our intervitality, acts of love and of life and of faith that bring our bonds into focus, as well as sharply delineating the hostile forces opposing an emergent us.

With this, at last, we return to our original question with something approaching an answer: can we bring our constitutive ties up to the level of naked visibility without relying on the reactive transformational process of mourning? We would say, “yes.*” We’ve now seen how acts of loving giving can be used to assert our latent bonds to one another and reawaken a dormant solidarity and power. It can also be said that loving giving undercuts the entire chain of valorization and contains a vestigial communal logic, on top of prefiguring a world of abundance and cooperation. My utopian heart yearns to proclaim this to be one of the many possible modes of proactively attacking capitalist relations laid out before us, but as is usually the case in this type of thinking, it is more complicated than that. It must be noted that loving giving only contains such potential usefulness for our cause because it is predicated on the great historical and ongoing theft occurring all around us. The theft of our spirit, our ideas and inventiveness, our bodily energy and our human potential, our mortal life and the content of our dreams, and of our ability to reproduce ourselves in harmony with each other and with nature. In this way, it too is a reaction to a great loss. Loving giving only rings out with such piercing resonance in a world of theft and isolation. It follows that our righteous attack on capitalist relations in the form of loving giving is in fact an expression of mourning; it is our grieving the world that could be.

Good Faith and Song Maybe it is impossible to avoid mourning in our search of a politics that can bring us towards another, better world. Perhaps it is best not to run from our loss, for we have lost a lot and lose more every day. In a world literally founded upon mass theft and slaughter, maybe it is indeed the most materialist site upon which to build something new. Our collective loss is perhaps one of the few remaining things we truly share in a world devoted to the accumulation of difference and distinction. Though, in these parting words, I want to also suggest that these differences and distinctions between us need not be a source of division and that the way forward may not necessarily entail the submission of the singular to the collective. One month has passed since the George Floyd riots of May-June and a process of division, repression, and recuperation has largely played itself out. Save for a select few city centers (and bravo to them), the fires have been doused and the barricades have been removed. The rowdy, “problematic” elements comprising the protests leading edge have largely been held back or outright turned over to the authorities and despite the rather astonishingly measured criticisms of criminal property destruction, the practice has broadly been replaced by more “respectable” forms of protest. The role bad faith has played in the apparent quelling of righteous rebellion cannot be understated. With the exception, apparently, of Portland, Oregon, the capitalist state did not require its superior military technology nor a COINTELPRO level conspiracy (although I’m sure we will learn much in the decades to come about how government agencies managed the flows of information on social media) to bring this uprising to its knees. The bad faith of debt society acts to ensure our governability. Control is smuggled into our minds by the trojan horse of opportunity which is then invaded and colonized by the forces of debt. One of the first tasks for us then must be the supplanting of the system’s bad faith with our forceful good faith. Many have already begun work on this urgent adjustment. Evidence of this can be found in the internationally adopted protest slogan “no good cops, no bad protestors.” And as long as the fighting continues somewhere, presently in Portland and perhaps Atlanta, the spark of uprising still dances in the winds of this world’s chaos and all remains possible.

With these final lines, I hope to clarify how exactly we can characterize this good faith and trace what it could look like in practice. As I have hinted at above, the good faith this moment requires is not that which requires some type of submission to a preformatted gestalt. It is not the good faith of brotherhood or family, nor is it the good faith of a party or an army. What is needed is a unique form of good faith that embraces difference, that leverages our irreducible singularity towards a collective end. If we are indeed to strum and pluck at our ties to one another, revealing and (re)politicizing our interconstitution and forging a new rhythm by which we ascribe our lives new meaning, we will need the type of trust found only among a group of musicians, the good faith of a band. A band’s members develop a sense of faith in one another that does not necessarily depend upon adherence to a set program or a uniform skillset. When one member improvises, they are trusting the others to keep rhythm. This good faith must flow in both directions. At the same time, the other band members must be able to trust that the improvisation of the first musician will not ultimately lead the group beyond an unsalvageable point of no return or to a place that jeopardizes the entire performance. We have seen a very similar dialectic play out in the last few months of protest. Peaceful marches go nowhere without the militant, sometimes violent, radical edge to push things forwards, applying pressure and teasing out the contradictions of our system. Likewise, the most radical elements of a protest are easily isolated, villainized, and violently squashed without the cover and legitimacy of the less radical masses. This is a delicate balance, and it will not be struck every time. Someone hits a bad note, someone reaches for a spectacular flourish but doesn’t cleanly play it; this happens with the most seasoned and well rehearsed performers and it undoubtedly will happen in our novice first attempts at creating music together. Mistakes are relatively unimportant. What is important is what happens after. Do we stand by one another, trusting that our partners are doing what they believe right as best they can? Or do we point fingers, stop playing, and allow our efforts to disintegrate so as to avoid being lumped in with a “bad musician?” We only need to look at the last few months of unrest in this country to see that the latter spells disaster and unstoppable fascism.

A comrade asked me while looking over my shoulder as I write these parting words, “what is the nature of the song we are writing? How does it sound and what is it about?” I’ve been thinking about how best to respond to this, especially as I sit somewhat aghast at the anarchy in the above paragraphs, written by an ostensible communist. Here I must solely rely on my much deeper personal experience as an actual musician literally playing music with friends than on my limited theoretical capacity and relatively amateurish abilities as a writer and worse still, thinker. In this light, the answer emerges immediately: at this beginning stage, when we are just now learning how to play our respective instruments, albeit in a condition of extreme urgency, it does not yet matter. What is important is that we play, and play together, often, and with a spirit of openness and experimentation; building trust and solidarity and good faith and friendship while honing our respective skills, finding our specialized roles in a revolutionary assemblage. It is only in this playing together that a common taste and interest can emerge. Deciding on a rhythm or a theme for a project before ever getting into a room together to play would unquestionably be putting the cart before the horse and in the same way, thinking up a program or adopting a party line would be premature if it is not done in the context of an already ongoing collaborative struggle. We cannot yet know what new rhythms of living and sources of meaning await our discovery and pretending as if we do could actually preclude us from ever arriving at a song truly worthy of us and our respective dreams and desires. Until that time, we must begin to do the mystical, patient work of fostering the conditions for a blooming solidarity, incubating trust and friendship, meticulously cultivating an ecology of love. For love is the energy with which the ties between us vibrate. With practice, this vibration can be bent into a tone, in time and as our power multiplies, a tone becomes a chord and then, a phrase, and one day, a song will erupt forth from the space between us and all that’s within us, unmistakable and unending, and with that song will come a new rhythm to move through the world to. With practice, good faith, and determination the day will come when our music has filled the air and all that remains on earth for us to do is dance together and fall into love. Inshallah.

“Music is a peculiar mode of chaosmosis: the osmotic process of transforming chaos into harmony. Music’s process of signification is based on directly shaping the listener’s body-mind: music is psychedelic (meaning, etymologically, “mind-manifesting”). Music deploys in time, yet the reverse is also true: making music is the act of projecting time, of interknitting perceptions of time. Rhythm is the mental elaboration of time, the common code that links time perception and time projection.” -Franco Bifo Berardi

“Some thoughts have a certain sound, that being the equivalent to a form. Through sound and motion, you will be able to paralyze nerves, shatter bones, set fires, suffocate an enemy or burst his organs.” -Paul Mu’adib in David Lynch’s Dune (1984)

0 notes