#arandaspis

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Super cambrian (and pre-cambrian) aquarium world...

Featuring the new creatures Arandaspis and Hallucigenia, and the new blocks Wiwaxia and Charnia, as well as a fresh new look for Sacabambaspis 🙏 Also featuring Aquarium Glass from Fintastic (what used to be Yet Another Fish Mod because Curseforge doesn't like when you put the word "mod" in your title)

#myart#digital art#artists on tumblr#creature design#art#minecraft#cambrian#mod development#minecraft modding#minecraft mods#anomalocaris#precambrian#ediacaran#charnia#dickinsonia#sacabambaspis#arandaspis#fish#aquarium#minecraft build#modded minecraft

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Arandaspis in Life on Our Planet (2023)

#life on our planet#arandaspis#marine biology#biology#netflixedit#steven spielberg#paleontology#paleoblr#paleomedia#prehistoric#prehistoric animals#dinosauredit#animalsedit#documentary#documentaryedit#natureedit#tvedit#gif#*

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

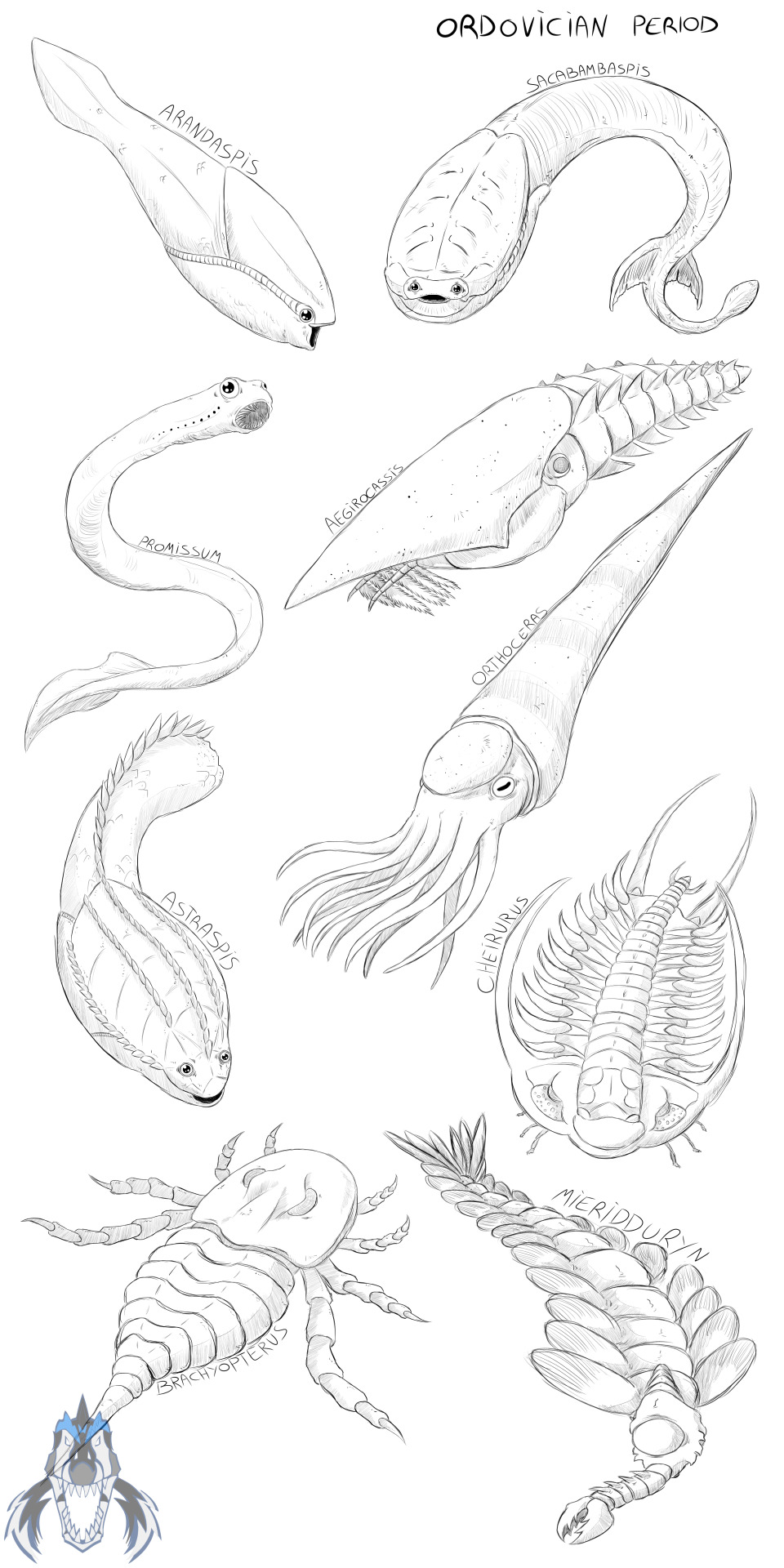

Some ordovician fellas

#ordovician period#paleozoic era#prehistoric animals#arandaspis#sacabambaspis#promissum#aegirocassis#astraspis#orthoceras#cheirurus#brachyopterus#mieridduryn

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wikipedia links in lieu of propaganda. Alkwertatherium, a cenozoic diprotodontid marsupial

Anamolocaris, a cambrian radiodont arthropod

Arandaspis, an ordivician jawless fish

Arcadia, a triassic temnospondyl amphibian

Australosuchus, a cenozoic crocodile

Australotitan, a cretaceous sauropod dinosaur

Australovenator, a cretaceous megaraptoran dinosaur

Austrosaurus, a cretaceous sauropod dinosaur

#please reblog#feel free to advocate for your favourite#palaeoblr#australian fossil alphabet thing#dinosaur#megafauna#alkwertatherium#anamolocaris#arandaspis#arcadia#australosuchus#australotitan#australovenator#austrosaurus

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shout out to the original pog fish, Arandaspis. Just a silly little drawing I wanted to do after watching Life on Our Planet and finding these prehistoric little guys extremely adorable.

#arandaspis#pog#fish#i have no idea how accurate this drawing is tbh cause i was just referencing the cg models in the show#but i hope this isn't another graham norton situation lol

0 notes

Text

I call him Aaron. I love him. He’s like a tiny vacuum

I’m watching life on our planet with my brother and I’m in love with arandaspis, the first vertebrae and sort of like a jawless fish “graced with a look of perpetual surprise”

He go :0

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trivia Tuesday Answer

Can you name an Ordovician animal? Here's a few you could have said:

Endoceras

Isotelus

Pentecopterus

Arandaspis

and of course, the corals we saw on Friday: tabulate and rugose!

Did you get any? See you tomorrow!

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forget, dinosaurs! 🦕 Meet the true OGs of the seas – the bizarre and beautiful creatures of the Ordovician era. Intrigued? 🤔 Join us this month to uncover fascinating stories, ancient wonders, and captivating mysteries from this extraordinary period! 🌊🔍

Image sources:

Paleozoic timeline - Smithsonian Institution

Aegirocassis - Marianne Collins, ArtofFact

Arandaspis - rareresource

Orthoceras -vertebresfossiles

Didymograptus - Nobu Tamura/Spinops

#paleo#paleontology#ordovician#zoology#ancient animals#prehistoric#marine animals#geology#animals#paleoblr#animal#wildlife#fauna#pokemon cards#pokemon#pokémon#orthoceras#science#science facts#education#discover#study blog#biology student#studyblr#scicomm#explore#earth#paleozoic#cool science#simps for science

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Life in the Ordovician

(top left: Endoceras; top middle: Promissum; top right: Pentecopterus; middle left: Aegirocassis; middle right: Bumastus; bottom left: first land plants; bottom middle: Sacabambaspis; bottom right: Arandaspis)

Art by:

Bumastus - Obsidian Soul

Promissum, Aegirocassis, Sacabambaspis - Nobu Tamura

Endoceras - AStepIntoOblivion

Pentecopterus - Patrick J. Lynch

Arandaspis - Christian Darkin

First land plants - Tahoenathan

After the Cambrian Explosion we reach the “Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event“ or GOBE (which, admittedly, sounds a lot less catchy than Cambrian Explosion).

The Ordovician starts directly after the Cambrian about 485 million years ago. Life really started to diversify during this period and came up with a lot of new and more modern forms (as far as you can call something that‘s 485 million years old “modern“). Groups like gastropods (slugs and snails), bivalves (shelled marine invertebrate) and brachiopods (shelled molluscs like clams, oysters, etc.) started to gain prominence. It really is a shame that, as a vertebrate myself, I am biased to things that also have bones and therefore won‘t talk a lot about those critters (maybe at some point i have to dig deeper into them). I can however tell you that those groups became very important to marine ecosystems and that the brachiopods especially are characteristic for the “paleozoic fauna“ in contrast to the “cambrian fauna“. Also, the fact that paleontologist distinguish between those two should give you a hint as to how impactful the GOBE really was.

Trilobites like Bumastus, which first originated in the Cambrian, were doing very well and diversified further. Most of them were bottom dwelling and relatively small, but the biggest ones, which lived during the late Ordovician could reach up to 70 cm. Just like the gastropods, bivalves and brachiopods, they were mayor players of their time, and just like them, they get concerningly little attention in relation to how big of a group they were and how important they were to our Earth‘s history. Although, I suppose I am part of the problem here, because I could go into deep detail about them right now. I‘m just not going to. Maybe some day…

While the trilobites were running around on the ocean floors some of the earliest chordates slowly turned into fish. They were of course a very basic type of fish. We call this group Agnatha, which translates to “no-jaw“, because, well, they didn‘t have jaws yet (they did have teeth though). Some jawless fish are still alive today, the lampreys and hagfish. They are truely disgusting, slimy, blood-sucking, eel-like creatures. The extinct jawless fish include the conodonts like Promissum. For the longest time scientists had no idea what kind of animal conodonts were, because the only parts of them that fossilized were their cone-shaped teeth (that‘s also where they got their name). Those teeth however were found everywhere and they are very important fossils, because by looking at them geologist can determine from which geologic age a fossil site is. Relatively recently we then started to find better preserved fossils, that revealed that conodonts where also eel-shaped and had big eyes. The other type of extinct jawless fish were the Ostracoderms like Sacabambaspis or Arandaspis. They are usually better preserved because their heads were covered in boney armor which fossilizes much better than the wiggly soft bodies of the conodonts.

One of the biggest names of the Ordovician was Endoceras, a shelled cephalopod (related to squids and octopus). And by big I mean that this weird ice cream cone was more than 3 m long. Another famous group that got their start during this time are the eurypterids, the sea scorpions, like Pentecopterus. Neither were they real scorpions (they were arachnids though, so close enough), nor lived they exclusively in the sea as there were a lot of fresh water species. There are some suggestions that they might have been able to at least briefly walk on land and breath in the air. They were also some of the biggest arthropods that ever live. Pentecopterus for example was about 1.7 m long and it wasn‘t even the biggest eurypterid (we‘ll get to that one later). They weren‘t all massive, but sizes of 1 m and more were not rare and to be honest, that‘s already way to big for any bug of my liking.

While all those new linages arose they slowly outcompeted many of the Cambrian weirdos I talked about last week. Some held on longer than others though. The Radiodonts (Anomalocaris and friends) declined during the Ordovician, but it was also the time during which we see the biggest one of them: 2 m long Aegirocassis. It was a filter feeder, so basically a giant whale of its time.

As all of that was happening in the oceans, another revolution happened quietly on the shores of our early planet: We see the very first land plants. Those early plants would have been non-vascular plants (vascular tissue is basically the plant equivalent to blood vessels; and it had not developed yet). They would have looked similar to mosses.

Even though those early plants wouldn‘t have looked very exciting, they would have put a lot of work into terraforming the world. It is believed that their photosynthesis lowered carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere and that this might have caused temperatures to drop, turning the late Ordovician into an ice age. We know for certain that this drop in CO2 levels and temperature happened. If it was actually caused by the photosynthesis is another questions, though. Another suggestion, that also makes plants the culprits, is that their roots increased the erosion of rocks and this erosion involved the reaction between the rocks and CO2 from the atmosphere. Another reason for increased erosion could have been vulcanism creating a lot more “new“ rocks to erode. An (to my ears) absolutely wild theory is that the earth actually didn‘t cool because of lower CO2, but instead got hit by a gamma-ray burst, which sounds like something out of a scifi-movie. Apparently a gamma-ray burst is an intense energy beam, that is caused by a supernova (I really know nothing about space…), and it could have stripped our planet very quickly of our ozone layer. As ozone is a greenhouse gas, just like CO2, that would have also caused a cool down.

Whatever it was, at the end of the Ordovician the earth froze over. Drastic changes in temperature usually lead to extinction and that was the case here as well. The Late Ordovician Mass Extinction killed around 85 % of marine species, which is a pretty big deal when you consider, that almost all species at the time were marine species. It is often seen as the second-worst of the mayor “big 5“ mass extinctions (we’ll get to all the other ones in the future, don‘t worry about it). But, unlike many other mass extinctions, it didn‘t have a mayor impact on the fauna and most groups of life recovered and re-diversified after the extinction. But that‘s a story for another time.

Again, all the info from wikipedia. I got some stuff about jawless fish here.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Astraspis

(temporal range: 467-443 mio. years ago)

[text from the Wikipedia article, see also link above]

Astraspis ('star shield') is an extinct genus of primitive jawless fish from the Ordovician of Central North America including the Harding Sandstone of Colorado and Bighorn Mountains of Wyoming. It is also known from Bolivia.[2] It is related to other Ordovician fishes, such as the South American Sacabambaspis, and the Australian Arandaspis.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

if nobody got me i know 'Arandaspis Prionotolepis' by Austin Wintory got me, can i get an amen-

0 notes

Note

wait what are your other top 5 prehistoric fish then

Bcjwhfhf I didn’t expect anyone to read my tags, here you go though!

1. Arandaspis was a lightly armored fish with plates instead of teeth that evolved in the early Ordovician period which is my FAVORITE geological period. A huge extinction event took place in this period, the first of the big five mass extinction events on earth that wiped out 70% of species.

2. Protosphyraena is a type of swordfish that evolved in the Cretaceous, and I like anything that can stab

3. Plesiosaurs aren’t technically a fish, it’s a “marine reptile”, but I love them a lot. A TA in one of my paleo classes gave a 45 minute lecture on them and it was great. Listen. Everything is a fish.

4. Haikouichthys, the earliest known fish and my beloved. It evolved during the Cambrian Explosion, and is characterized by having one long fin running down its back. Your honor I love him.

5. Of course, Dunkleosteus, the mentioned 5th favorite

Honorable mention: EURYTPERIDS are my absolute favorite prehistoric animal!! They were 2-3 meter long sea scorpions that were cousins of the more well known trilobite. I have a recreation of a eurypterid fossil on my wallet and it’s one of my prized possessions

Thank you for the ask! This was fun to write :D

0 notes

Text

Netflix and Spielberg combine for nature doc 'Life on Our Planet'

LOS ANGELES

"Life on Our Planet," the new natural history series from Netflix and Steven Spielberg, sets out to tell the entire, dramatic story of life on Earth in a serialized, "binge watch" format.

Streaming globally from Wednesday, the show's eight episodes transport viewers through Earth's five previous mass extinction events, each recreated with computer-generated visual effects.

As Morgan Freeman's narration reminds us, life has always found a way to endure every catastrophic event thrown at it over four billion years, from brutal ice ages to meteorites.

Each time, species that survive the destruction do battle for the next era's dominance in a "Game of Thrones"-style fight -- only between vertebrates and invertebrates, or reptiles and mammals, instead of Starks and Lannisters.

"What we wanted to do, our intention at the very beginning, was to serialize the story of life. Make it a kind of binge watch. Because the story is so dramatic," said showrunner Dan Tapster. "I think, and I hope, that is something that we've achieved, which is possibly a world-first in the natural history space."

Aside from a series of cliffhanger finales, "Life on Our Planet" finds dramatic tension with a series of ordinary, loveable underdogs who "win" evolution against the odds -- at least for a few hundred million years.

The influence of executive producer Spielberg's company, Amblin Television, encouraged a series with "a lot more emotion" and "pathos" than other natural history programs, said Tapster.

The show picks out key species, such as the first fish with a backbone, or the first vertebrate to migrate from ocean to land.

With 99 percent of all the species that ever lived now extinct, filmmakers had no shortage to choose between.

"There's about at least a billion species that are no longer with us, and we had to narrow that down to 65," said Tapster.

But those selected are often unlikely heroes -- plucky survivors, such as the odd-looking Arandaspis fish, which take their chance to shine as larger ocean beasts falter, and reshape the future of life.

Arandaspis "is a bit rubbish, it's weird... But it's in (the show), because it has a really crucial role" in evolution, said visual effects supervisor Jonathan Privett.

"One of the things I really love about that scene also is that Arandaspis has just got a hint of 'ET' about him," added Tapster.

The series employs visual effects from Industrial Light & Magic, the company established by "Star Wars" creator George Lucas, which pioneered the groundbreaking 3D dinosaurs for Spielberg's "Jurassic Park" three decades ago.

Monsters of the ancient past, from dinosaurs to the far earlier, sea-dwelling Cameroceras with their giant 25-foot (8-meter) shells, are rendered over the top of real backgrounds shot by the filmmakers.

To do this, producers had to scour the planet for contemporary landscapes that most closely resemble the habitats of creatures up to 450 million years ago.

"The animals really sit in a real world. I think it's seamless, and I think it's a very authentic way of taking us back into that time," said producer Keith Scholey.

Filmmakers also had to use visual effects tools to painstakingly remove pesky modern newcomer species, like fish, mammals -- and even grass.

"Grass was the bane of our lives," recalls Tapster. Grass "only really took over the world about 30 million years ago... that, for us, meant we had to do a lot of gardening."

The show enters a crowded marketplace, going up against David Attenborough's latest BBC series "Planet Earth III," which also launched this week.

It follows Apple TV+'s "Prehistoric Planet," also narrated by Attenborough, which uses computer-generated effects to recreate the age of dinosaurs.

But "Life on Our Planet" also aims to stand out from the competition due to the timely message embedded within its narrative.

Despite the show's interest in cliffhangers and plot twists, it is not much of a spoiler to say that it ends with life surviving, and humans on top.

Yet with a sixth mass extinction event already under way due to humankind's impact on Earth, there is a deeply sobering warning too.

"The five events we've had so far, there has been one common denominator -- and that is, the dominant species as you go into that extinction never came out," says series producer Alastair Fothergill.

"We are creating the sixth one, and I think you probably think we are the dominant species at the moment ..."

Tapster added: "In a strange way, there is a message of hope within that. Because not only is this the first extinction event that is being caused by a species, but we also have the ability to stop it."

0 notes

Note

you're the sacabambaspis.

Sacabambaspis is an extinct genus of jawless fish that lived in the Ordovician period. Sacabambaspis lived in shallow waters on the continental margins of Gondwana.[1] It is the best known arandaspid with many specimens. It is related to Arandaspis.

Sacabambaspis was approximately 25 centimetres (9.8 in) in length. The body shape of Sacabambaspis vaguely resembled that of a tadpole with an oversized head, flat body, wriggling tail, and lack of fins. It had characteristic, frontally positioned eyes, like car head lamps.[2]. Sacabambaspis had a head shield made from a large upper (dorsal) plate that rose to a slight ridge in the midline, and a deep curved lower (ventral) plate, this headshield is ornamented with characteristic oak-leaf shaped or tear-drop shaped tubercles.[3][4] Also it had narrow branchial plates which link these two along the sides, and cover the gill area.[3] The eyes were far forward and between them are possibly two small nostrils and they, which are surrounded by what is thought to be endoskeletal bone, and putative nostrils, are found at the extreme anterior of the head, one of the diagnostic features of the arandaspids.[3][4] The rest of the body was covered by long, strap-like scales behind the head shield.[3]. The tail consists of relatively large dorsal and ventral webs and an elongated notochordal lobe, the posterior end of which is bordered by a small fin web. This tail structure clearly differs from that of heterostracans, which are currently grouped with arandaspids and astraspids in the clade Pteraspidomorphi (Gagnier 1993, 1995; Donoghue & Smith 2001; Sansom et al. 2005), in which the caudal fin looks diphycercal (i.e. symmetrical) and strengthened by a few large radials (Janvier 1996).[5]Sacabambaspis is named after the village of Sacabamba, Cochabamba Department, Bolivia, where the first fossils of the genus were found.[6] S. janvieri (Gagnier, Blieck & Rodrico, 1986), the type species of the genus, is known from the Anzaldo Formation of Bolivia.[6] There are 30 known specimens of this Bolivian species, all crammed into a very confined area, believed to be the result of a fish kill, probably due a sudden inflow of freshwater from a large storm. They were found associated with a large number of lingulid brachiopods, also killed at the same time.[7]

Indeterminate specimens (described as "Sacabambaspis sp.") have been found in many countries corresponding to the margin of Gondwana. Young, 1997 described fossils of the genus from the Stokes Siltstone and Carmichael Sandstone of Central Australia.[8] Isolated scales found in the Horn Creek Siltstone from Central Australia have a very similar ornamentation to the Bolivian scales.[7] Specimens have also been reported from Argentina.[1] Sansom et al., 2009 described specimens from the Amdeh Formation of Oman on the Arabian Peninsula. The Oman discoveries showed that the fish were present all around the periphery of the ancient continent of Gondwana and not just in the southern regions as had previously been shown by the findings from South America and Australia.[1][9]

Although it had no jaws, the mouth of Sacabambaspis janvieri was lined with nearly 60 rows of small bony oral plates which were probably movable in order to provide more efficient suction-action through expansion and contraction of the oral cavity and pharynx.[7]

The fossils of Sacabambaspis show clear evidence of a sensory structure (lateral line system). This is a line of pores within each of which are open nerve endings that can detect slight movements in the water, produced for example by predators. The arrangement of these organs in regular lines allows the fish to detect the direction and distance from which a disturbance in the water is coming.[4]

that’s me

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

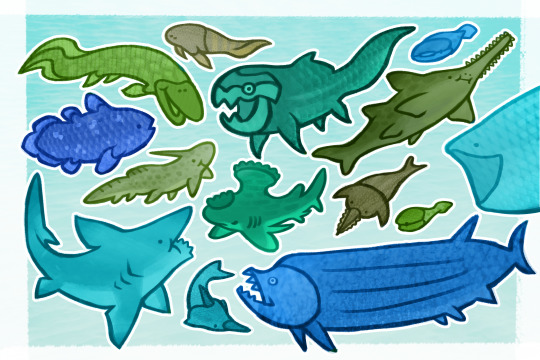

🐟 fossil fish gang 🐟

Here’s something a little late for fossil fish week B)

#my art#fish#shark#paleoart#fossil fish week#dunkleosteus#tiktalik#coelacanth#helicoprion#xenocanthus#stenthacanthus#Xiphactinus#Leedsichthys#Onchopristis#Doryaspis#Pteraspis#Arandaspis#bothriolepis#placoderms#leedsichthys is so huge large it is just his funny face over there#not that any of these are to scale anyways lmao

453 notes

·

View notes