#appellate court typically

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Ian Millhiser at Vox:

The Supreme Court handed down a strange set of opinions on Monday evening, which accompanied a decision that largely reinstates Idaho’s ban on gender-affirming care for minors. The ban was previously blocked by a lower court. None of the opinions in Labrador v. Poe spend much time discussing whether such a ban is constitutional — although Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s concurring opinion does contain some language suggesting that he and Justice Amy Coney Barrett will ultimately vote to uphold the ban.

Rather, seven of the nine justices split into three different camps, each of which proposes a different way that the Court should handle cases arising on its “shadow docket,” a mix of emergency motions and other matters that the Court decides on an expedited basis — often without full briefing or oral argument. The Labrador case arose on the Court’s shadow docket. Indeed, Idaho’s lawyers did not even attempt to defend its restrictions on gender-affirming care on the merits. Instead, they argued that the lower court went too far by prohibiting the state from enforcing its ban against any patient or any doctor. A majority of the justices agreed with the state, ruling that the ban cannot be enforced against the actual plaintiffs in this case, two trans children and their parents, but that it can be enforced against anyone who has not yet sought a court order allowing them to receive gender-affirming care.

How the justices divided in this case

While none of the justices discussed at much length whether they think the Constitution permits Idaho to ban transgender health care, every justice but Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Elena Kagan joined one of three opinions laying out how they think the Court should respond to parties asking them to provide relief on the Court’s shadow docket. Ordinarily, the Supreme Court waits until a case has been fully litigated in the lower courts before weighing in on a case in any way. Under its normal process, the Court also typically receives hundreds of pages’ worth of briefing on a case, hears oral argument, and spends months deliberating on how to decide it. Cases on the shadow docket, by contrast, ask the justices to bypass this ordinary process, typically to block a lower court order before the case has been fully resolved by a lower appellate court. The justices used to grant shadow docket relief very rarely — most often in death penalty cases where the inmate would be executed if the Court did not intervene swiftly — but it started granting it very often in the Trump administration after Trump’s Justice Department started routinely requesting shadow docket relief.

The justices divided into three camps in the Labrador case, with each camp joining concurring or dissenting opinions laying out how they think shadow docket cases should be resolved moving forward. Justice Neil Gorsuch, joined by Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito, faulted the lower court for issuing a “universal injunction” that prohibits Idaho from applying its anti-trans law to any party. Gorsuch argued that courts should issue more limited orders when a state or federal law is successfully challenged, which only prevent the state or the federal government from enforcing its law against the specific plaintiffs who brought the successful challenge. Kavanaugh, joined by Barrett, argued that, in shadow docket cases, the Court often “has little choice but to decide the emergency application by assessing likelihood of success on the merits.” That means the Court’s decision to grant shadow docket relief will often turn on whether they think the party seeking such relief should ultimately prevail when the courts reach a final decision in the case.

That’s potentially very bad news for transgender children. Though Kavanaugh's opinion does not discuss whether he thinks Idaho’s law is constitutional, the fact that he voted to reinstate the law (except with respect to the two plaintiff families in this case) suggests that he thinks Idaho has a “likelihood of success on the merits” when the ultimate question of whether trans health care bans are legal reaches the Supreme Court. Finally, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, joined by Justice Sonia Sotomayor, argued that the Court should show more “restraint” when it is asked to grant shadow docket relief. She argues that “our respect for lower court judges — no less committed to fulfilling their constitutional duties than we are and much more familiar with the particulars of the case — normally requires an applicant seeking an emergency stay from this Court after two prior denials to carry ‘an especially heavy burden.’” Although neither Roberts nor Kagan joined any of these opinions, Kagan briefly indicated that she would have denied the request to reinstate Idaho’s law in its entirety.

SCOTUS handed down a shadow docket decision permitting Idaho's law banning gender-affirming care (HB71) to take effect while Labrador v. Poe is still being litigated in lower-level courts. #SCOTUS

#Labrador v. Poe#Idaho HB71#Idaho#Gender Affirming Healthcare#Transgender Health#Transgender#SCOTUS#9th Circuit Court#Shadow Docket

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

Whenever we think of royal families our minds tend to go to the concept of the European noble House. The House of Habsburg, the House of Windsor, the House of Stuart etc. I understand that we should look at the Ancient Greek, Macedonian & Hellenistic royal families in a different way becuase of the different family & power dynamics - could you please help us understand the difference?

Ancient Court Societies vs. Modern

Probably the biggest difference is greater organization of hierarchy. Modern royal houses have had a lot of time to evolve.

Norbert Elias’s The Court Society has become the foundational study on court systems, although it’s western-focused by intent. Nonetheless, it’s a useful introduction to how courts function with inner courts, outer courts, etc.

The biggest things to keep in mind are:

The degree of formality between court members. How “deep” and structured is the hierarchy? (Smaller courts typically have far less formality than larger ones.)

How formalized are matters of succession and marriage ties? Particularly the presence (or absence) of royal polygamy can affect that.

Court societies inevitably progress from less formal and hierarchical to more of both. We can sometimes talk about earlier court societies as chieftain-level societies versus more organized royal, or even imperial societies.

Part of the struggle first Philip, then Alexander faced was transforming a chieftain-level court system into something that would work on a (much, for Alexander) larger scale. Unsurprisingly, there was push-back against, essentially, “bureaucracy.” Nobody likes it, but the larger an area controlled, the more necessary it becomes.

Traditional Macedonian courts were fairly informal, the king being primo inter pares (first among equals). No titles were used when addressing him—he was called by his name—and the only thing expected of the speaker was to take off his hat. “King” (basileus) was used when speaking OF him. We don’t see “King ___” employed in Macedonia (at least in inscriptions) until Kassandros, who needed it to buck up his claim.

None of that means the average person could wander into the palace and start chatting up the king. He was protected by his Bodyguards (Somatophylakes), who also apparently managed access to him. Yet he was expected to sit in judgement as an appellate court, where anybody could appeal a case before him. How often this occurred no doubt depended. Philip was gone a lot, and Alexander was permanently out of Macedonia two years into his reign. Presumably his regent fulfilled the role in his absence. (As I depicted near the beginning of book 2, Rise, when Alexandros is hearing cases.) Anyway, that’s one place the “average person” could get the ear of the king. Also, it seems that he was more approachable by soldiers in battle circumstances. We’re told Alexander got right in with his men to do work during sieges. It was to encourage them, but he was standing next to them so they could see and talk to him, if they wanted to. He seems to have known many of his veterans by name.

Another factor in Macedonia was lack of formal hierarchy among nobility. They had a nobility—the Hetairoi (King’s Companions)—but theoretically all Hetairoi were equal in status. In practice, they absolutely weren’t. The king also had an inner circle referred to as “Friends” (Philoi), who acted as chief advisors. The problem with both terms is their use as common nouns as well as special titles. When is a friend a Friend?

Also, at least some of this was hereditary. Yes, making (or removing) Hetairoi was in the power of the king. But it was much easier to do the former than the latter, and even strong kings didn’t do the former early in their careers, never mind the latter. For many, becoming Hetairos was a rubber-stamp. They were Hetairoi because their fathers had been. We’re also not sure if the title was extended only to the eldest male in a household, or more than one could hold it at once, but for most, it was a birthright.

So, when Alexander took the throne, he was stuck with his father’s Somatophylakes (Bodyguard) and inner circle of advisors. He absolutely could not toss them out on their ear to install his own men. He had to proceed sloooowly. Which is why we don’t see Hephaistion as a Somatophylax even by the Philotas Affair, five years into ATG’s reign. He was clearly an advisor (Philos), but didn’t become Bodyguard until sometime later. Same thing with Ptolemy, who apparently got Demetrios’s slot—the Bodyguard (almost surely one of Philip’s) behind the actual conspiracy of Dimnos, not the made up one of Philotas. When he was executed, Alexander promoted Ptolemy to his slot. Note that Ptolemy was made Somatophylax before Hephaistion. Politics, family status, and probably age trumped personal affection.

If Hetairoi couldn’t be kings themselves (unless they were also Argeads), they were king makers, and kings had to take their influence into account. Especially new kings.

As a chieftain level society, Macedonia operated on “rule by clan” with the king being the senior male Argead. His brothers, sons, nephews, and male cousins might all have important roles, as did the women, although theirs were primarily religious and the running of the royal household. Yet royal women could do limited politicking in the way of donations (eurgetisms) to create goodwill, promote the family, or make alliances—as well as (of course) the alliance created by their marriage itself. Most of these roles were informal and ad hoc, rather than titular, if also expected of them. For instance, the king’s wives were just that: king’s wives. The title queen (basileia) wasn’t used until the Hellenistic courts of the Diadochi.

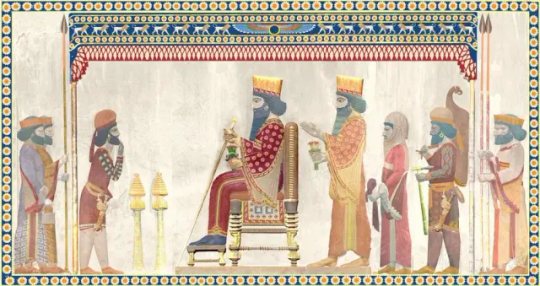

Ancient near eastern courts were more stratified, with more distinct roles. In fact, it seems that Macedon, from Alexander I onward, borrowed offices from the Achaemenid Persian court, including the Bodyguard and the Royal Pages (King’s Boys). So as early as the late Archaic Age, Macedonia looked east for how to formalize a court. Certainly Philip did it well before Alexander. The notion that Alexander’s Persianizing was somehow new is bull malarky.

Anyway, in the ANE, kings tended to fit one of two traditions: shepherd king or heroic king. The Sumerian kings and Hammurabi (Old Babylon) were both examples of the shepherd-king model. Heroic kings began with the Akkadian, Sargon the Great, then the neo-Assyrian kings, especially the Sargonids. Cyrus cast himself as a heroic king, but we see a shift back to shepherd kings with Darius the Great. Another aspect of ANE kingship were three chief expectations: win wars, build big shit, and administer justice.

Due to a much longer tradition of kingship extending from the Early Bronze Age, as you may imagine, these court systems developed much more in the way of formalized structures and offices. If these changed from king to king, at least by Bronze-Age Babylon (Hammurabi), then Neo-Assyria, access to the king was severely curtailed. At least the Persian kings got out and moved around on a sort of “King’s Progress,” but that was to check up on satraps. The average citizen saw them only at a distance. In contrast the Sargonids of neo-Assyria emerged from their palace complexes almost exclusively when going to war.

The Medes and Persians, like the Hittites before them, fit themselves into ANE traditions after they arrived in the area. Less is known about pre-ANE Hittites, but if they kept some unique religious traditions, when it came to How to Run an Empire, they used Akkadian and Egyptian precursors. Similarly, the Medes and Persians who came from the steppes, also adopted ANE patterns while retaining some traditions—again particularly religious (Zoroastrianism). We know a wee bit more about them prior; they (like Macedon) seem to have had chieftain-level monarchy with rule by clan, plus tribal princes, before conquering the whole area.

I hope that helps in understanding ancient eastern Mediterranean and near eastern notions of a court. We know less about the Odrysian Thracian and Illyrian kings to Macedonia’s north, but I suspect they were similar to early Macedon. Just tooling around Thrace, it was very clear to me that we’re looking at a shared regional culture between that area and Macedonia. Similar vibes attended my visit to Aiani (ancient Elimeia) and Dodonna (Epiros). I didn’t get up into Illyria, but what I do know of the archaeology suggests the same. ALL these cultures, despite the ethnic and linguistic differences, influenced each other. Yes, ancient Macedonia was at least “Greek-ish,” but we can’t and shouldn’t dismiss the impact on them from their northern neighbors.

Last, let’s consider the role of royal polygamy. Well back into the Bronze Age, ANE kings might marry several wives and also kept concubines for political purposes. That’s why we call it royal polygamy, not just polygamy. Royal polygamy might exist in a society that otherwise limits the number of wives anyone not the king can have.

Macedonian kings also practiced it, and Thracian and Illyrian, but on a more limited scale. Greeks and Romans, then Christians, depicted any polygamy as a “barbaric Oriental” (= morally corrupt) practice that supported their general view of Asia as soft and indulgent. (Sex itself wasn’t a vice, but too much sex was: uncontrolled desire.)

In later Europe, kings might have mistresses, but it wasn’t “official,” and they certainly didn’t have multiple wives. Christianity frowned on that. Even before, Roman emperors didn’t employ royal polygamy, although they did use serial monogamy—a long-standing practice back into the Roman Republic. Yet that required divorce. When the Christian church made marriage both a sacrament and a vow (not a contract, as it had been pretty much everywhere else), they made divorce impossible without either a wife’s death or religious shell games like annulment. Until Henry VIII, European kings were largely stuck with just one marriage.

Ancient courts didn’t have that problem. And from a political point of view, monogamy is a problem. It reduces the number of political ties available. Having royal polygamy offers more fluidity in possible heirs, and increases, sometimes exponentially, avenues for political alliance.

That said, the downside can be messy inheritance. Two of the more infamous inheritance disputes (other than Alexander’s) involved Esarhaddon, youngest son of Sennacherib, and Cyrus the Younger vs. Artaxerxes II. The latter dispute resulted in civil war (thank you, Xenophon, for telling us about it). As for Esarhaddon, he was so in danger from his older brothers, his mother kept him out of the capital until claimants were dead. There are others, but these two leapt to mind. There are also Egyptian examples, but I’m far less knowledgeable about those dynasties. And, as we see later in Europe, disputed successions can occur without polygamy!

Anyway, when it comes to selection of the heir, two things that matter in polygamous courts: status of the mother, and (for the ANE) whether she was queen. Not all wives were also queens. In the case of Esarhaddon, his mother Naqiʾa was of lower status and not a queen, so when his father named him heir, his older brothers (and their court allies) blew a gasket. Both Assyrians and later Achaemenid Persian kings could marry as many women as they wanted, plus take concubines…but the heir was expected to be from his Chief Wife, or Queen. Of “pure” blood. Cyrus the Younger’s argument against his older brother rested on a similar status technicality: he’d been born after his father became king, while Artaxerxes II was born before. We’d say Cyrus was “born to the purple.” But it was just an excuse; he was the ambitious one, and their mother favored him. If Macedonia didn’t have queens, the status of the mother mattered to being selected as heir there as well.

So these are some of the chief differences between ancient Mediterranean and near eastern courts, compared to later European.

#asks#Alexander the Great#ancient Macedonia#ancient Macedon#ancient Persia#ancient Assyria#ancient Babylon#court societies#ancient court societies#Macedonian court#Philip II#kingship in the ancient near east#kingship in Macedon#Classics#tagamemnon

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

from @rustingbridges: we had mandatory review? when was that? and yeah I would on priors believe FDR's court got up to some shit

tl;dr from 1910, increased in 1937, mostly removed in 1976 but still in place, via three judge district court

from a law review article called Three-Judge District Courts, Direct Appeals, and Reforming the Supreme Court’s Shadow Docket by Michael Solimne, professor at Cincinnati

Since Congress established the Courts of Appeals in 1891, and given subsequent statutory developments, most civil and criminal cases in the federal courts have been litigated in the familiar pattern of proceedings before a single district judge; followed by an appeal as of right to a regional Court of Appeals; and followed by a writ of certiorari to the Supreme Court, which has the discretion to grant or deny the petition. A notable exception to this pattern came in the wake of the Supreme Court’s then-controversial decision in 1908 in Ex parte Young, which recognized an exception to state sovereign immunity by permitting plaintiffs to bring constitutional challenges to state statutes in federal court by suing not the state, but the state official charged with enforcing the law. The decision was controversial because it enabled plaintiffs (a railroad in Ex parte Young) to more easily challenge Progressive Era regulatory laws in federal court, and empowered one federal district judge to enjoin the operation of a statewide law. Congress responded to Ex parte Young in 1910 by enacting legislation, which required such suits to be brought before a three-judge district court, with a direct appeal available to the Supreme Court. The statute required that the court consist of one district judge and at least one court of appeals judge, with the third judge being appointed by the Chief Judge of the circuit (typically, though not always, another district judge). Supporters of the statute thought three judges, rather than one, would bring greater thought to the important issue of the constitutionality of a state law, and the result would arouse less public controversy as compared to the decision of a single judge. The direct appeal provision would make it more probable that any appeal would be more rapidly resolved as contrasted to the usual appellate process. Constitutional challenges to federal statutes were added to the ambit of the three-judge district court in 1937. That legislation was a small part of the fabled and failed Court-packing plan proposed by President Franklin Roosevelt in that year. The plan was primarily a reaction to a majority of the Supreme Court holding New Deal legislation unconstitutional, but the President and his supporters in Congress were also concerned with the many suits in the district courts leading to no less than 1600 separate injunctions of legislation. They argued that constitutional challenges to federal statutes should be treated with “equal dignity” to that of state statutes,and largely tracking the rationale for the 1910 Act, the amendment was passed with relatively little fanfare in August of 1937, after the Court-packing plan had been rejected. ...

The impetus for the 1910 and 1937 legislation eventually faded, and Congress severely cut back the jurisdiction of the three-judge district court in 1976. In part, the reforms were a victim of their own success. By the 1960s and 1970s, hundreds of three-judge district courts were being convened each year, and scores of direct appeals were being lodged in the Supreme Court. Most of each were challenges to state statutes, with not coincidentally many related to the burgeoning Civil Rights era and attendant litigation. Influential figures and organizations in the legal community, not least of whom were Justices on the Court itself, came to conclude that the virtual flood of litigation was a burden on both district courts (given the time-consuming logistics of assembling three judges rather than one to decide a case at the trial level) and on the Supreme Court (given that the direct appeals were ostensibly mandatory and had to be decided on the merits). Moreover, many argued that the original perceived need for the three-judge district court process had largely faded, and that even controversial and important litigation could be handled appropriately by a single district judge with the normal appeal process. ... Despite the almost complete abolishment in 1976, the three-judge district court has enjoyed a robust afterlife. Left standing was a separate such court established by the 1965 Voting Rights Act, to decide declaratory judgment actions regarding whether certain States and political subdivisions were, in making changes to election laws, subject to preclearance by the Department of Justice. Since the 1976 repeal, several federal statutes have been passed in the past several decades with judicial review provisions for that particular law, mandating that any constitutional challenges thereto are litigated before a three-judge district court, with a direct appeal to the Supreme Court.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fred P. Graham, The Self-Inflicted Wound (Macmillan, 1970):

The result [of pre-incorporation Due Process doctrine] was also a Federal standard of constitutionality that in light of today’s values seems to have tolerated too much. Volumes 356, 357 and 358 of the United States Reports contain the Supreme Court decisions for 1958—a typical year when the fundamental fairness doctrine was in full flower. They include such rulings as these:

—In Illinois a man was accused of killing his wife and three children. The state tried him for killing the wife, but introduced evidence of all four deaths, and the jury gave him a twenty-year sentence. The state went for the death penalty again, prosecuting him for killing one of the children. This time he got forty-five years. At the third trial, for killing another of the children, the jury finally sentenced him to death. The Supreme Court held that his double jeopardy argument was irrelevant, since the Fifth Amendment did not apply to the states. Otherwise, the procedure did not seem fundamentally unfair, so the death sentence was affirmed. [Ciucci v. Illinois, 356 U.S. 571 (1958)]

—A New York businessman was subpoenaed to testify before a state grand jury investigation into labor racketeering. He was given a grant of immunity from prosecution on state corruption charges, but he still refused to testify, pointing out that he might incriminate himself under similar Federal labor racketeering statutes. The state judge nonetheless gave him a thirty-day jail sentence for contempt of court, and the Supreme Court affirmed on the ground that the Fifth Amendment does not apply to the states. [Knapp v. Schweitzer, 357 U.S. 371 (1958)]

—A New Jersey man was tried for the robbery of three persons in the course of a tavern stick-up. None of the three could identify him, and although a fourth patron did, he was acquitted by the jury. The state then tried the defendant again for the robbery of the patron who said he could identify him, and this time the defendant was convicted. The Supreme Court let the conviction stand on the ground that the double-jeopardy clause does not bind the states. [Hoag v. New Jersey, 356 U.S. 464 (1958)]

—On the advice of his attorney, a New Jersey murder suspect turned himself in to the police. They isolated him in an interrogation room and questioned him for seven hours, refusing to let the lawyer see or advise him until after he confessed. The Supreme Court upheld the confession, finding it voluntary. [Cicenia v. Lagay, 357 U.S. 504 (1958)]

—A Los Angeles man was arrested on charges of having murdered his mistress. During the fourteen hours between his arrest and his confession he asked repeatedly to be allowed to call his lawyer, but was refused until after he confessed. His death sentence was affirmed by the Supreme Court. [Crooker v. California, 357 U.S. 433 (1958)]

* * *

In the three decades between Brown v. Mississippi and Miranda v. Arizona, the Court delivered thirty-six opinions on the voluntariness of state court confessions. They covered a wide variety of circumstances; some confessions were upheld and others were thrown out. The result was that state courts could examine the case-by-case authorities of the Supreme Court and could find authority for affirming or rejecting almost any type of confession.

In 1963 H. Frank Way, Jr., a political scientist at the University of California, studied the 126 state appellate court rulings on allegedly coerced confessions that had been reported in a previous seventeen-month period. He found that the Supreme Court’s subjective test “provides no substantial yardstick for the states,” and that only a handful of the opinions even referred to Supreme Court confessions decisions. As an example, he noted that all six of the confessions reviewed and upheld by the Texas courts during this period included elements of heavy-handed justice. He described one appellant’s case as follows:

"Here then is an accused who made a confession after being twice arrested without a warrant, after being illegally arraigned on a false charge under a fictitious name, and after being illegally held and questioned intermittently during a two-day period, with the final interrogation continuing throughout the night. Of course, he had no legal counsel during this period. Collins was described by medical experts as being of low intelligence, with an abnormally low tolerance for stress—a man who had the character of a three to six year old child. With the use of this confession, Collins was convicted of murder and sentenced to ninety-nine years of imprisonment."

The other five cases included: (a) a defendant who was illegally arrested and, according to undisputed evidence, beaten until he confessed; (b) a Mexican-American who was arrested without a warrant and questioned intermittently for three days before he confessed and was arraigned; (c) a Negro who was sentenced to death on the strength of a confession given after intermittent all-night questioning, including, he claimed, beatings; (d) a robbery suspect who was questioned for fifty minutes and confessed because, he claimed, he was sick and the police refused to take him to a hospital until he talked; (e) a twenty-two-year-old man with a sixth-grade education who was never arraigned, and who was denied counsel during his interrogation and also at his trial, which resulted in a five- to thirty-five-year prison sentence.

* * *

[In Ohio,] the State Supreme Court had given its blessing to warrantless searches, even in situations when search warrants could have been easily obtained. A victim of one such search, a Cleveland woman named Dolree Mapp, appealed her case to the U.S. Supreme Court. The summary of her case in the Supreme Court’s opinion [Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643, 644–45 (1961)] showed how much police abuse some state courts would excuse:

On May 23, 1957, three Cleveland police officers arrived at appellant’s residence in that city pursuant to information that “a person [was] hiding out in the home, who was wanted for questioning in connection with a recent bombing, and that there was a large amount of policy paraphernalia being hidden in the home.” Miss Mapp and her daughter by a former marriage lived on the top floor of the two-family dwelling. Upon their arrival at that house, the officers knocked on the door and demanded entrance but appellant, after telephoning her attorney, refused to admit them without a search warrant. They advised their headquarters of the situation and undertook a surveillance of the house.

The officers again sought entrance some three hours later when four or more additional officers arrived on the scene. When Miss Mapp did not come to the door immediately, at least one of the several doors to the house was forcibly opened and the policemen gained admittance. Meanwhile Miss Mapp’s attorney arrived, but the officers, having secured their own entry, and continuing in their defiance of the law, would permit him neither to see Miss Mapp nor to enter the house. It appears that Miss Mapp was halfway down the stairs from the upper floor to the front door when the officers, in this high-handed manner, broke into the hall. She demanded to see the search warrant. A paper, claimed to be a warrant, was held up by one of the officers. She grabbed the “warrant” and placed it in her bosom. A struggle ensued in which the officers recovered the piece of paper and as a result of which they handcuffed appellant because she had been “belligerent” in resisting their official rescue of the “warrant” from her person. Running roughshod over appellant, a policeman “grabbed” her, “twisted [her] hand,” and she “yelled [and] pleaded with him” because “it was hurting.” Appellant, in handcuffs, was then forcibly taken upstairs to her bedroom where the officers searched a dresser, a chest of drawers, a closet and some suitcases. They also looked into a photo album and through personal papers belonging to the appellant. The search spread to the rest of the second floor including the child’s bedroom, the living room, the kitchen and a dinette. The basement of the building and a trunk found therein were also searched. The obscene materials for possession of which she was ultimately convicted were discovered in the course of that widespread search.

At the trial no search warrant was produced by the prosecution, nor was the failure to produce one explained or accounted for. At best, “There is, in the record, considerable doubt as to whether there ever was any warrant for the search of defendant’s home.” The Ohio Supreme Court believed a “reasonable argument” could be made that the conviction should be reversed “because the ‘methods’ employed to obtain the [evidence] . . . were such as to ‘offend “a sense of justice,” ’ ” but the court found determinative the fact that the evidence had not been taken “from defendant’s person by the use of brutal or offensive physical force against defendant.”

seems bad

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

BASICS.

NAME: Elminster "El" Aumar ALIAS(ES): Elmara; Eladar; Wanlorn; Gochall; Minstrel; El'Minster; Terminsel; Elgorn; Farwalker TITLE(S): Herald of Mystra; Sword of Mystra; Chosen; Master Harper; Elf-friend; Last Prince of Athalantar; The Mighty; The Wise; The Crafty; Armathor of Myth Drannor; Court Mage of Galadorna; The One Who Walks; Old Spellhurler; The Old Mage; The Old Sage; The Sage of Shadowdale; The Great Oversorcerer; Doombringer of Mystra; Weavemaster; The Harper APPELLATION(S): The Terrible; The Doomed; The Meddler of Mystra; Accursed One; Cursed One; The Great Foe MISCELLANEOUS: Old Weirdbeard; Uncle Weirdbeird; Beard Man RACE: Human CLASS(ES): Archmage; Wizard; Rogue; Cleric; Fighter PATRON DEITY: Mystra BIRTHDAY: Mirtul 30, 212 DR BIRTHPLACE: Heldon, Athalantar GENDER: Genderfluid (uses all pronouns) ORIENTATION: Panromantic pansexual

FAMILY.

GRANDPARENTS: Uthgrael Aumar, the Stag King (grandfather); Syndrel Hornweather, Queen of the Hunt (grandmother) PARENTS: Elthryn Aumar (father); Amrythale Goldsheaf (mother) UNCLE(S): Belaur; Elthaun; Cauln; Othglas; Felodar; Nrymm CHILD(REN): Susprina Arkenneld (adopted daughter); Storm Silverhand (adopted daughter); Dove Falconhand (adopted daughter); Laeral Silverhand (adopted daughter); Haedrak Rhindaun III aka Lhaeo (adopted son); Narnra Shalace (daughter); Laspeera Inthré (daughter); many others DESCENDANT(S): Filfaeril Obarskyr (great-great-great-great-great-granddaughter); Amarune Whitewave (great-great-granddaughter); at least one unnamed great-great-grandson; Simon Aumar (great-great-great-grandson); many others

PERSONALITY.

ALIGNMENT: Chaotic Good MBTI: ENFJ (Protagonist) ENNEAGRAM: 5w6 (Problem-Solver) TEMPERAMENT: Phlegmatic FLAME: Cloud

APPEARANCE.

FACE: Rectangular with a distinctive hawk nose and crooked grin HAIR: Once a rich black, now white as stars; typically worn in long locs, often with a long beard to match EYES: Gray blue, at once both piercing and gentle SKIN: Warm, dark umber that's known much adventure SCAR(S): Detailed here HEIGHT: 6' BUILD: Wiry in their youth, now erring on scrawny; much stronger than they appear FACECLAIM(S): Steve Toussaint; Viola Davis

BIOGRAPHY.

El has lived an absurdly long life with an unbelievable amount of adventures, and they're still kicking. It's more than I care to condense into a bio, frankly. Thus I'll be giving an overview of their earliest years. Further details can be found in the timeline.

ELMINSTER WAS BORN IN THE small country village of Heldon, Athalantar. Their early days were spent peacefully, tending sheep and learning at their parents' feet. Then it was lost in a blaze of dragonfire. They were twelve years old when the Warring Princes of Athalantar sought out their hidden brother, El's father, to lay low him and all his issue. From then on, El was forced to make their way as an outlaw and a thief — or else be slaughtered by their uncle and the mages puppeteering him.

Seven years past before they could hide no longer. They entered Mystra's temple intending to burn it down, but left under Her divine guidance. There was nothing El hated more than mages and their goddess, but he couldn't thwart them by learning spells more powerful. First they were a cleric. Then they were a wizard. Then they were the face of a revolution. They rallied their allies and drove the tyrant and his mages from the land. However, El chose not to take the throne in the end. They wisely abdicated to Helm Stoneblade. Then they left, never to return, lest his reign be destabilized by their presence.

This was not an end for Elminster, merely a greater beginning. They'd hardly made it out of the capital of Hastarl before Mystra offered them a divine blessing — and divine burden. If El willed it, they would become Mystra's Chosen to serve Her will and further the Art across Toril. They accepted. They have thus outlived their natural lifespan by over a millennium, and have suffered grief and torments beyond any other. Still, they persist. Their greatest comfort lays in helping others; so long as they can be a force for good, they are satisfied.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Daredevil Timeline Thoughts

Assuming that Matt and Foggy weren't exaggerating all that much when they told Karen they had been lawyers for a couple of hours, I submit the following two timelines for how this might have happened.

POSSIBLE TIMELINE 1

Late December 2013 – Early January 2014*: Apply to take Multistate Professional Responsibility Examination (MPRE).

Late March 2014: Takes the MPRE.

April 1, 2014 – April 30, 2014: Apply to take the New York Bar Exam (NYBE).

Late April 2014 or Early May 2014**: Get results from MPRE.

May 5, 2014 – May 16, 2014: Take end of year exams.

May 22, 2014: Attend graduation ceremony from Columbia Law School.

May 22, 2014 – July 28, 2014: Study for NYBE.

July 29, 2014 – July 30, 2014: Take NYBE***

October 28, 2014: Get results from NYBE.

October 31, 2014: Receive Notice of Certification from the Appellate Division, submits application for admission to New York Bar.

November 2014: Has fitness and character interview, mandatory orientation program, and admission ceremony where the oath of office is administrated in open court.

November 2014 – July 2015: Try to convince a bank to give two baby attorneys with no trial experience a business loan to start their own law firm while doing some kind of work in order to pay for things like rent and food.

July 2015****: Events of Daredevil Season 1 begin.

*I could not find exact dates for MPRE except for this year (2023) so I'm guessing based on those dates.

**MPRE typically gives the results about six weeks after taking the exam.

***Consisting of the Multistate Bar Exam (MBE), Multistate Performance Test (MPT), and New York law oriented exam consisting of 5 essays questions and 50 multiple choice questions. New York doesn't start using the Universal Bar Exam (UBE) in combination with the NYLC (New York Law Course) and NYLE (New York Law Exam) until 2016.

****MCU and MCU-related stuff are presumed to take place in the same year they aired unless specifically stated otherwise so Daredevil Season 1 took place sometime during 2015. Judging by the weather we see in the first season, I using the month they began filming in New York City which was July.

POSSIBLE TIMELINE 2

April 2014: Apply to participate in the Pro-Bono Scholars Program*

Late July 2014 – Mid-September 2014: Apply to take Multistate Professional Responsibility Examination (MPRE).

October – November 2014: Accepted into the Program.

November 1, 2014 – November 30, 2014: Applies for New York Bar Exam (NYBE).

Early November 2014: Takes the MPRE.

Mid-December 2014: Gets results from MPRE.

January 2015 – February 23, 2015: Study for bar exam

February 24, 2015 – February 25, 2015: Takes NYBE.

March 1, 2015: Begin Program of combination of pro-bono legal work under supervision of attorney + classwork under supervising Columbia faculty member.

April 27, 2015: Gets results from NYBE.

ca. May 22, 2015**: Complete Program.

June 2015: Receive J.D from Columbia.

June 2015: Receive Notice of Certification from the Appellate Division, submits application for admission to New York Bar.

June 2015: Has fitness and character interview, mandatory orientation program, and admission ceremony where the oath of office is administrated in open court.

July 2015: Get their business loan for Nelson & Murdock.

July 2015: Events of Daredevil Season I begin.

*New program announced in February 2014 by then Chief Justice of New York Jonathan Lippman.

**Program is 12 weeks long, estimate is based on current year estimated dates on Columbia's website.

ADDITIONAL NOTES

Matt would be encouraged to apply for his exams as soon as possible since he has to apply for disability accommodations and that requires some additional forms and documentation.

Doing the Pro-Bono Scholar Programs satisfies the requirement for 50 hours of pro-bono work for admission to the New York Bar that came into effect in January 2015.

SOURCES

Columbia Law School (https://www.law.columbia.edu/)

New York State Board of Law Examiners (https://www.nybarexam.org/)

National Conference of Bar Examiners (https://www.ncbex.org/exams/mpre/)

New York Unified Court System (https://www.nycourts.gov/)

FURTHER THOUGHTS

Alternately, Matt and Foggy passed the bar a couple years prior to series and worked for a couple of years at a law firm or as a judge's clerk while they built up a fund / prepared a business plan to convince a bank to give them a business loan*. AND actually learn how to be trial attorneys since law school doesn't teach you that.

*Given that they reference being in debt and how expensive Columbia is, any money Jack left Matt was long gone so they would need a loan to cover their start-up costs.

IN CONCLUSION

Any thoughts?

Probably to be continued since this isn't the only timeline related thing that snares the part of my brain prone to overthinking.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Texas' execution of Stephen Barbee on Wednesday evening was prolonged while prison officials searched for a vein in the disabled man's body, according to a prison spokesperson.

Barbee, convicted in the 2005 murders of his pregnant ex-girlfriend and her child, had severe joint deterioration, which prohibited him from straightening his arms or laying them flat, according to court records. His attorney had recently tried to halt his execution because he feared the process with Barbee's disability would result in "torture."

But courts rejected the appeals, noting that prison officials had vowed to make special adjustments to the death chamber's gurney to accommodate Barbee.

RELATEDTexas executes Tracy Beatty for strangling mother to death

Still, it took much more time to carry out the execution than is typical in Texas. Reporters walked into the prison around 6 p.m. CST, signaling the execution was about to begin. But for an hour and 40 minutes, no one came back out, causing anti-death-penalty protesters outside to grow worried that something had gone wrong. It is uncommon for executions to last more than an hour.

"Due to his inability to extend his arms, it took longer to ensure he had functional IV lines," prison spokeswoman Amanda Hernandez said in an email Wednesday night.

Barbee was pronounced dead at 7:35 p.m., nearly an hour and a half after he was strapped into the death chamber's gurney, according to the prison's execution record.

RELATEDTexas man sentenced to death for killing Harris County's first Sikh deputy

Within minutes of being strapped on the gurney, an IV was inserted into his right hand, at 6:14 p.m., but it took another 35 minutes for an additional line to begin flowing in the left side of his neck. All the while, his friends watched through a glass pane adjacent to the chamber, according to a prison witness list. So did the friends of the murder victims -- Lisa Underwood and her 7-year-old son Jayden -- as well as Underwood's mother.

About 15 minutes after the IV was inserted into his neck, he gave his final statement, thanking God, his minister and his loved ones.

"I just want everyone to have peace in their heart, make eternity with Jesus, give him the glory in everything you do. I'm ready," he said, just before a lethal dose of pentobarbital was injected at 7:09 p.m., 26 minutes before he was pronounced deceased.

Hours before the prisoner's scheduled death, Barbee's execution was paused as courts battled once again over the state's handling of the prisoner's religious rights in the death chamber.

Federal courts this month went back and forth over Texas' execution policy and the findings of multiple U.S. Supreme Court rulings largely requiring the state to allow prisoners' religious advisers to audibly pray and touch them in their final moments.

On Tuesday, a district judge essentially halted Barbee's pending execution, stating Texas' prison system can only kill the death row prisoner after creating and adopting a new execution policy that clearly lays out his final religious rights. But after the federal appellate court and the U.S. Supreme Court both ruled in favor of the state early Wednesday afternoon, Barbee's execution was put back on track.

Barbee, 55, was convicted of the 2005 murders in Tarrant County. Under police interrogation, Barbee confessed to the killings, saying he feared Underwood would tell his ex-wife he was likely the father of her unborn child and he would have to pay child support. Soon after, he recanted the confession, which his lawyer argued was "the product of fear and coercion," and he had since maintained his innocence.

Instead, Barbee said his co-worker Ron Dodd, also a defendant in the murders, committed the murders alone, and he helped Dodd hide the bodies. After Barbee was sentenced to death, Dodd pleaded guilty to tampering with physical evidence and got 10 years in prison, acknowledging he helped Barbee dispose of the victims' bodies.

Barbee's first execution date, set for 2019, was stopped by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals to further investigate whether it was a violation of Barbee's Sixth Amendment right to counsel when his trial attorney told the jury he was guilty against his wishes. In a Louisiana case, the U.S. Supreme Court had recently ruled that defendants have a right to insist their lawyers don't admit guilt even if the attorneys believe such a concession is the best shot at avoiding the death penalty.

Early last year, the Texas court finally handed down a highly technical ruling concluding Barbee wasn't eligible for a new trial because he didn't tell his attorneys clearly enough that he wanted to maintain his innocence. The judges said that although Barbee repeatedly told his lawyers that he was innocent and would not plead guilty, and although he was shocked at the concession of guilt at his trial, he didn't tell them his defensive strategy included an innocence claim, so he wasn't wronged under court precedent.

After the ruling, Tarrant County officials moved for a new execution date, set for October 2021. That time, it was canceled by U.S. District Judge Kenneth Hoyt of Houston while the U.S. Supreme Court weighed another Texas man's case in a series of rulings over the Texas prison system's handling of prisoners' religious rights in the execution chamber. Barbee had requested that his spiritual adviser pray over him and lay his hand on him as he died, a practice which had recently been barred by prison officials.

This March, the high court ruled that Texas' execution policy likely violated a prisoner's religious rights, and prison officials said it would make adjustments to execute people in line with the court's intent.

Before Wednesday's execution, his lawyers still argued there was an unacceptable lack of clarity in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice's execution policy regarding religious practices. Though the prison officials conceded to following the orders of the nation's high court, the practice wasn't put into the state's execution policy.

Hoyt agreed, saying earlier this month that Texas could carry out Barbee's execution only if it updated its execution policy in a clear and consistent manner with U.S. Supreme Court rulings.

"TDCJ is now operating under an unwritten policy where prison officials may unilaterally decide whether to allow an inmate's requested accommodation ... the accommodation may be withdrawn at the will or caprice of any prison official at the last moment," Hoyt wrote in his ruling.

Prison officials swore in court affidavits that Barbee would be allowed to have his adviser touch him and pray as he dies. Federal appellate judges said Friday that Hoyt's ruling was too broad, extending beyond Barbee's needs alone, and sent it back to Hoyt to be revised. On Tuesday, Hoyt issued a new ruling mirroring his previous one but applying it to Barbee only.

"Texas [TDCJ] may proceed with the execution of Stephen Barbee only after it publishes a clear policy that has been approved by its governing policy body that (1) protects Stephen Barbee's religious rights in the execution chamber ... and, (2) sets out any exceptions to that policy, further describing with precision what those exceptions are or may be," Hoyt said in his injunction.

On Wednesday afternoon, the U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals tossed the injunction, saying Hoyt can't order the state to devise a new execution policy. Instead, two judges said a proper order would have been to require the prison to follow its word and allow Barbee to have his spiritual adviser present, audibly praying and laying hands on him as he died.

Barbee's lawyers had also moved to stop his current execution because they said his disabilities would result in extreme pain if he is strapped to a gurney as prisoners typically are in Texas executions.

For 15 years, Barbee had increasingly lost his range of motion in numerous joints, resulting in him being unable to straighten his arms. His disability had long been documented in his prison medical records, resulting in him using a wheelchair and needing a tool to clean himself after using the bathroom, according to court filings. The prison used handcuff extensions on him because he couldn't put his hands behind his back.

"If someone wants my arms to straighten out in any way, I guess one would have to break my arms, because even forcing them, they won't straighten," Barbee said in a written affidavit last year. "It's been like this for years and it's getting worse."

Last week, the prison warden said in an affidavit that Barbee would not be required to straighten his arms on the gurney. Hoyt dismissed the case Tuesday afternoon, saying the prison had told Barbee months ago he would be accommodated.

"The leather straps that secure his arms to the arm rests are adjustable ... which allows for his arms to remain bent," Kelly Strong, the warden of the Huntsville Unit, said in her affidavit.

"Moreover, while the crook of the elbow is the preferred location for the IV insertion during an execution, the IV lines have been inserted in other locations when a suitable vein could not be utilized," she said.

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

If Barbie was trying to go for a "both extremes are bad" angle, they did a poor job. Even if ST!Barbie apologized to ST!Ken for taking him for granted, that doesn’t change their society as a whole. The Kens still have no say in anything, and that’s treated as just fine. Hell, they asked for ONE supreme court justice and got turned down. I can see why people are annoyed when the real world is shown as a sexist nightmare, but the inverted version is portrayed as fine even though in some ways /1

it’s worse. The real world HAS female supreme court justices. Like, being a Ken SUCKS, and it doesn't get acknowledged or get better at the end of the movie. They’re just told to "find out who they are without Barbie", which really doesn't work when Ken was literally created to be Barbie's boyfriend. We can have an ongoing scene talking about how awful it is to be a woman, but actually addressing that the Kens are essentially second-class citizens? Nah. We’re just gonna joke about how they don’t matter. Multiple times. I expected some kind of equality in Barbieland at the end of the movie, now that they’d seen how bad the other extreme was, but no. “Everything back to normal except now maybe the Kens will bother us less”, and that’s the good ending. It was disappointing. (And before anyone asks, I'm a girl) /3

Okay, but if you watched my video, I pretty much say:

"Barbieland is seen as a net-positive... for the Barbies."

You'll notice how often posts about 'the protagonist of a story is not always the hero of a story'. Us as the audience can see that Barbieland is a magical dystopia ruled by toxic-femininity, that the Big Barbie Barage isn't a group of heroes going up against an evil foe, but the equivalent of toddlers screaming 'My turn!!'/'No, MY turn!!' over a playhouse set.

The new status-quo at the end isn't an ideal, it's a bandaid.

Actually, this response ran a bit long, so...

The whole Supreme Court thing... While, yes, it is still kind of 'come on, now' that President Barbie says no, 1. you can kind of understand why she doesn't want to give the time of day after everything that just happened, and 2. she grants them an Appellate Court. So there is at least a step in the right direction there.

Yes, Ken (as a concept) was originally created to be Barbie's boyfriend/husband/support, in subsequent decades even Mattel has tried to stem away from that. Hell, they actually broke up in the 90s! I'm surprised that a lot of people forget that. And, as a mirror...

Hold on, I have to reconcile with myself that I'm going to make this comparison. ...Okay.

In Judeo-Christian faiths, Eve is literally created to be a support and mate for Adam (being created from the rib, or established foundation, of Adam). Yet, women have eventually had to come and realize that they are more than that and that they can find their own identities and purpose.

Could the movie have presented a comparison like this a bit better? Yes. However, that's what that part was supposed to mirror.

But the whole thing shows a series of checks and balances. The real world does have fields that are typically male-only. Sometimes people who have talents for certain jobs aren't allowed to have them. Like America Ferrera's character clearly shows a love and talent for fashion and doll-design... But they have her as a secretary.

And, yes, we do have women on the Supreme Court. The... same Supreme Court that has also been fumbling the bag in recent news. So they aren't perfect for having some pussy on board either.

I mean, it's pretty clear that Barbieland wasn't a utopia at the beginning of the film or at the end of the film when Stereotypical Barbie essentially embraces death and chooses to live as a human in the real world at the end.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

You’ve mentioned before that typically the lawyers for a criminal defense case are responsible for trial costs (I think that’s what you called them. I’m referring to things like psychological tests.) What about on the other side of things? How does the process work for the prosecution to get permission for and fund the same?

Also, semi-related, who is the ‘prosecution’ for an appeal (the people arguing that the convicted person should not get a reduced sentence)? And how are they bankrolled?

These are great questions!

So if the prosecution requests tests and evaluations and things like that, it's generally done at the expense of the government agent that the prosecution represents. So if you're a city prosecutor, it's the city; if you're a county prosecutor, it's the county. And so on. However, sometimes the prosecutor will ask, as part of sentencing, that the defendant reimburse the government for the price of the evaluation.

Alternatively, the defendant can request specifically that the evaluation be done at the government's expense.

Ultimately, it's up to the judge to decide who they think should pay for it. A good judge will account for the defendant's employment status (and will especially account for the possibility that the defendant will be imprisoned and not able to make money).

To your second question, there are (at least???) two ways a defendant can try to get a better outcome even after a conviction. One is an appeal, and one is a request for post-conviction relief (PCR). The two overlap in some ways but not others and it's really complicated and kinda confusing tbh. But basically, an appeal is saying, "The judge ruled incorrectly." Whereas PCR is saying, "My rights were violated in some way [most often by ineffective assistance of counsel or prosecutorial misconduct]."

Appeals are heard by an appellate court. The person who files the appeal (usually the defendant) is now called the "petitioner." The person responding to the appeal (usually someone from the government) is called the "respondent." Depending on how big and fancy the prosecutor's office is, they might have a whole appellate division with people who only do appellate work. For smaller offices, whichever prosecutor handled the initial case will be unlucky enough to also be the respondent if there's an appeal.

With PCRs, as far as I know, the same prosecutor who handled the case will basically always handle the PCR. Also, PCRs are determined by the same judge who handled the underlying case.

During my time as a law clerk, I worked for a district judge. District judges function as appellate courts for magistrate judge, and so I got to review two appeals of a magistrate judge's decision. I also got to review several PCRs. It was all pretty fascinating to see how the legal process can continue even after a sentence.

Thank you so much for the ask. 💚

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

in terrorem clause

Terrorized by a clause

The Texas no-contest clause should lead to caution

Who should be afraid of an in terrorem clause?

You, that's who.

An in terrorem clause is a no-contest, or forfeiture, clause often found in wills.

Although the text may vary, the typical wording provides that a beneficiary who challenges or disputes the validity of the will is disinherited.

A quick example:

Mom signs a will that leaves you her house and car, and your brother the remainder of her estate.

The will contains an in terrorem clause.

You think your brother is going to end up getting more than you, so you challenge Mom's capacity to execute the will.

You lose your challenge.

Your reward?

You end up forfeiting both the house and car.

Your brother takes all.

In terrorem clauses, in the words of the Amarillo Court of Appeals, "allow the intent of the testatrix to be given full effect and seek to avoid vexatious litigation among family members."

Your mom clearly did not want the family members fighting each other over their inheritance.

Including the clause in her will was her way of discouraging family discord.

She was essentially urging you to take what you get gracefully.

That's your mom, still parenting from the grave.

You should have listened.

While courts narrowly construe in terrorem clauses to avoid forfeiture, that doesn't mean they ignore them.

A lawsuit challenging testamentary capacity of the testatrix is one type of contest that results in forfeiture.

So is challenging your mom's choice of executor.

Suppose she named your brother as her executor.

You want more control, so you challenge your brother to serve as as executor.

You lose your challenge.

Cue the in terrorem clause.

Your attempt to set aside the part of her will naming an executor was a contest of her will.

You just forfeited the house and car, again.

In terrorem clauses are enforceable unless the contestant shows that just cause existed for bringing the action, and the action was brought and maintained in good faith.

That provision can be found in a statute in the Texas Estates Code.

Nothing is simple, however.

The terms "just cause" and "good faith" are not defined in the statute.

So we turn to case law, which is found in the opinions of the appellate courts.

Returning to the Amarillo Court of Appeals, we find that in a 2023 opinion the Amarillo court defined "good faith" as an action prompted by honesty of intention or a reasonable belief that the action was probably correct.

The court defined "just cause" as bringing actions that are based on reasonable grounds, with a fair and honest reason for the contestant's actions.

The trial court decides on a case-by-case basis whether a contest was brought in good faith and with just cause.

That is a fact question.

If the trial court does not decide that question, then the appellate courts have no jurisdiction to do so.

Here is how it works mechanically:

You file your contest of your mom's will alleging she had no capacity when she executed the will, and further stating that you had just cause to bring the contest and did so in good faith.

Your brother files an answer denying your contest, and further alleging that you violated the in terrorem clause.

The court rules against you, and then you must prove the good faith and just cause elements just to avoid forfeiture.

The in-terrorem clause is meant to terrify you into reasonableness. It does a pretty good job.

0 notes

Text

Josh Kovensky at TPM:

U.S. District Judge Aileen Cannon for the Southern District of Florida dismissed the Mar-a-Lago records case against Donald Trump on Monday. Per the order, Cannon dismissed the case after finding that Special Counsel Jack Smith’s appointment violated the Constitution. Cannon’s determination that Smith was unlawfully appointed effectively endorses a legal theory tested multiple times in previous cases and dismissed, rooted in the idea that the Attorney General cannot appoint and fund a special counsel absent authorization from Congress. That was seen as an absurd notion, and one contravened by decades of special counsel investigations under the current statute.

But it received a boost both after Cannon held a multi-day hearing on the question and after Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas supported the idea in a concurrence in the Trump immunity ruling. Cannon cited that concurrence throughout her order. The immediate effect of the dismissal will be to end what was seen as the simplest and most threatening of the criminal cases against Trump. Trump’s decision to retain classified records after the government repeatedly asked for them to be returned took place nearly entirely after he left office, and purportedly imperiled some of the most sensitive national security information the government possesses.

The outright dismissal will allow Smith to appeal Cannon’s ruling to the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals. Until Monday, Cannon had mostly ruled in ways that deprived the parties of the ability to appeal, effectively delaying any potential trial until after the November election.

The ruling caps more than a year of stunning decisions from Cannon, beginning in the investigation’s pre-indictment phase. Then, Cannon broke with fundamental principles of criminal law to order a halt to the investigation after Trump filed a civil suit seeking the same. [...] In this case, Cannon’s decision to dismiss the case by finding that Smith was unlawfully appointed reads more like an appellate – or Supreme Court – ruling than that of a district court judge, typically charged with applying existing precedent. Cannon’s ruling both nakedly benefits Trump and contravenes rulings issued by other conservative judges. Hunter Biden, for example, moved to dismiss the gun charges against him by arguing that Special Counsel David Weiss was improperly appointed. The judge in that case, a Trump appointee, rejected the motion. It’s one of many examples in which other judges – even of the same ideological stripe – rejected the legal theory that Cannon endorsed on Monday.

Right-wing Trump-appointed judicial activist Aileen Cannon issued a ruling today in United States v. Trump dismissing the Jack Smith Special Counsel investigation regarding the classified document theft and Espionage Act violations. It is repulsive that Trump is allowed to get away with committing blatant document theft at Mar-A-Lago.

Smith is expected to appeal the ruling to the 11th Circuit Court.

See Also:

HuffPost: Judge Dismisses Trump’s Classified Documents Indictment

#Aileen Cannon#Donald Trump#Classified Documents#Jack Smith#Jack Smith Special Counsel Investigation#Trump Indictment II#Judicial Activism#11th Circuit Court#United States v. Trump#Document Theft#Espionage Act

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bail Hearing Appeal in Criminal Procedure

In criminal law, bail is a mechanism that allows an accused person to be temporarily released from custody, typically pending trial or the final resolution of a case, in exchange for specific conditions or monetary guarantees to ensure their return to court. Bail serves as a balancing tool in criminal justice systems worldwide, promoting the principle that individuals should not be held in pretrial detention without a legitimate reason. Bail hearings, which determine whether an individual should be granted or denied bail, are critical steps in this process. If bail is denied, the accused may seek to appeal that decision through a bail hearing appeal.

This essay examines the process of a bail hearing appeal in criminal procedure, exploring its purpose, legal framework, procedural requirements, and the considerations courts take into account.

Purpose of Bail Hearings

Bail hearings serve the dual purpose of balancing the rights of the accused with the need to protect public safety and ensure the integrity of the judicial process. The principle of "innocent until proven guilty" underpins the argument for bail, ensuring that individuals are not punished before their guilt is established. Bail allows defendants to continue their lives—whether it be work, education, or family responsibilities—while awaiting trial, preventing the unnecessary detention of individuals who are presumed innocent.

However, in some cases, releasing an individual on bail may pose risks. For instance, there could be concerns that the accused will flee, fail to attend court proceedings, or pose a threat to public safety or witnesses. In such cases, courts can deny bail.

When bail is denied or set at conditions deemed unreasonable by the accused, the option to appeal the decision becomes crucial. The bail hearing appeal criminal procedure serves as a secondary review process that allows higher courts to reconsider the initial decision, ensuring that it was both lawful and reasonable.

Legal Framework Governing Bail and Bail Appeals

The legal framework governing bail and its appeal is typically derived from statutory provisions, constitutional guarantees, and case law, though it may differ from one jurisdiction to another.

In common law countries like the United States, the UK, Canada, and Australia, bail rights are often governed by both legislation (such as the Bail Act or Criminal Procedure Code) and constitutional provisions that ensure due process and personal liberty. For example, in the U.S., the Eighth Amendment protects individuals from excessive bail, ensuring that bail conditions should not be more onerous than necessary. Similarly, international conventions, such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), emphasize the right to liberty and protection against arbitrary detention.

Bail hearing appeals typically occur within a specific legal framework:

Initial Bail Decision: The trial court makes an initial decision on bail based on factors like the seriousness of the offense, flight risk, risk to public safety, and ties to the community.

Right to Appeal: If the defendant or prosecution disagrees with the decision, the next step is to file an appeal in a higher court. The right to appeal the bail decision is usually provided for in criminal procedure laws, and the appeal must be filed within specific timeframes.

Review Standard: The appellate court reviews the bail decision to ensure it was made correctly, based on the law and evidence. Courts may apply different standards of review, such as a "de novo" review (where the appellate court re-examines the facts and law as if it were the original decision-maker) or an "abuse of discretion" review (where the appellate court only overturns the decision if it was unreasonable or based on an error of law).

Procedural Requirements in Bail Appeals

The procedure for filing a bail appeal is typically straightforward but requires strict adherence to statutory rules. The following are common steps in the appeal process:

Notice of Appeal: The first step is for the defense or prosecution to file a notice of appeal. This document must be submitted within a prescribed time limit after the initial bail ruling and should indicate the grounds for the appeal.

Bail Application/Submission: Along with the notice, an application or legal submission outlining the arguments for why bail should be granted or modified is required. This application should include supporting evidence, such as character references, evidence of stable employment, or proof of residence, to demonstrate that the accused is not a flight risk or danger to the community.

Court Review: Once the notice and application are submitted, a higher court (such as a district court, appellate court, or supreme court) reviews the bail decision. This review could be based solely on the written submissions or involve an oral hearing where the defense and prosecution present their arguments.

Factors Considered in Appeals: The appellate court will examine various factors when deciding on the appeal. These include:

Flight Risk: Is the defendant likely to flee the jurisdiction and not return for trial?

Public Safety: Does the accused pose a threat to individuals, witnesses, or the public?

Severity of the Charges: More severe offenses, particularly those involving violence or large-scale fraud, may justify higher bail amounts or the denial of bail.

Prior Criminal History: A history of prior offenses, especially for the same or similar charges, can influence the court's decision.

Strength of the Evidence: If the evidence against the accused is overwhelming, this may lead to a decision to deny bail to ensure that justice is served.

Appeal Outcome: After reviewing the submissions and arguments, the appellate court can:

Affirm the lower court’s bail decision, leaving it unchanged.

Modify the bail conditions (for example, reducing the monetary amount or adjusting the restrictions imposed on the accused).

Considerations in Bail Appeals

When considering a bail appeal, courts strike a delicate balance between competing interests. On one hand, there is a need to protect the public and ensure that accused persons return to court for trial. On the other hand, personal liberty and the right to a fair trial are also significant constitutional rights that must be protected. Courts are cautious not to overstep constitutional protections, especially the presumption of innocence.

Judges typically rely on a set of guiding principles when deciding bail appeals:

Presumption of Innocence: The accused remains innocent until proven guilty, and detention without trial contradicts this fundamental principle. Therefore, bail is usually granted unless the prosecution can show compelling reasons why detention is necessary.

Proportionality: Bail conditions, including the monetary amount or restrictions, must be proportionate to the offense and the risks posed. Excessive or unreasonable bail conditions may amount to pretrial punishment, which is against constitutional guarantees.

Risk Management: Courts also consider whether the risks associated with releasing the accused can be managed through other means, such as electronic monitoring, house arrest, or travel restrictions.

Conclusion

Bail hearing appeals are critical in the criminal justice system because they provide a mechanism for reviewing decisions that may affect a defendant's fundamental right to liberty. By allowing higher courts to scrutinize bail decisions, appeals ensure that the rights of the accused are protected while balancing public safety concerns

0 notes

Text

Pennsylvania Appellate Practice Lawyers: Your Key to a Successful Appeal

Navigating the legal system can be daunting, and when it comes to appealing a court decision, the stakes are even higher. If you believe there were legal errors or significant oversights in your trial, an appeal may be your best chance at justice. To succeed in this complex process, having an experienced appellate attorney in Pennsylvania on your side is critical.

In this blog, we’ll explore how the best appeal lawyers in Pennsylvania can be your key to a successful appeal and what you should know when selecting a top appellate attorney.

Why You Need a Pennsylvania Appellate Attorney

Appeals are not the same as trials. They don’t focus on presenting new evidence but on reviewing the legal proceedings of the original trial to identify errors or misapplications of the law. The process requires a lawyer with a deep understanding of appellate law, strong legal writing skills, and the ability to argue persuasively in front of appellate judges.

An experienced appellate attorney in Pennsylvania knows how to scrutinize trial records, identify legal mistakes, and draft compelling arguments to persuade appellate courts. With the right strategy, your attorney can help overturn wrongful convictions, reduce sentences, or achieve other favorable outcomes in civil or criminal cases.

What to Look for in the Best Appeal Lawyers in Pennsylvania

When selecting an appellate attorney, it's important to choose someone with a proven track record of success in appellate courts. Below are key qualities to look for:

1. Extensive Appellate Experience: The best appellate lawyers have a wealth of experience in appeals and are familiar with Pennsylvania's appellate courts, including the Superior Court, Commonwealth Court, and the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. Their experience gives them insight into how different judges may interpret the law.

2. Strong Analytical Skills: Appeals require careful analysis of the trial court's proceedings. A great appellate attorney must be able to identify legal errors and develop a strategy for challenging them effectively.

3. Superior Legal Writing: Appellate cases largely depend on written briefs submitted to the court. These briefs must be clear, concise, and legally sound. A skilled appellate attorney in Pennsylvania knows how to craft persuasive arguments that make a compelling case for their client.

4. Oral Argument Expertise: Oral arguments in appellate courts can significantly impact the outcome of the appeal. The best appellate attorneys are confident, articulate, and able to respond to judges' questions in a way that reinforces the written brief.

The Appellate Process in Pennsylvania

The appeals process in Pennsylvania involves several steps. It is crucial to understand the timeline and procedural requirements when working with an appellate attorney:

1. Notice of Appeal: The first step is filing a notice of appeal within a strict time frame after the trial court’s decision (typically 30 days). Missing this deadline can forfeit your right to appeal.

2. Preparation of the Record: Your attorney will obtain and review the entire trial court record, including transcripts, motions, and rulings, to determine if legal errors occurred.

3. Brief Submission: The attorney will then draft and submit a written brief outlining the legal errors that justify overturning or modifying the trial court’s decision.

4. Oral Arguments: Depending on the case, oral arguments may be scheduled where the appellate attorney will present their case before a panel of judges.

5. Court Decision: After reviewing the briefs and hearing arguments, the appellate court will issue a decision, which can affirm, reverse, or modify the trial court’s judgment.

Why Hire a Top Appellate Attorney in PA

Hiring a top appellate attorney in PA can significantly enhance your chances of success on appeal. These attorneys have honed their skills in navigating the complexities of appellate law, and their deep understanding of procedural requirements and legal precedent can make all the difference in the outcome of your case.

Many appeals fail because of technical errors in the brief or oral argument, or because the appellant’s lawyer wasn’t able to make a persuasive case. A top appellate attorney knows how to avoid these pitfalls, ensuring that your appeal is given the best possible chance of success.

Conclusion

If you or someone you love is considering an appeal in Pennsylvania, don’t leave your future to chance. The best appeal lawyers in Pennsylvania possess the knowledge, skills, and experience to help you challenge a court's ruling. Their expertise in identifying legal errors and crafting persuasive arguments can be the key to turning your case around. Contact a top appellate attorney in PA today to discuss your case and begin the appeals process with confidence.

Source:

0 notes

Text

Intellectual Property Disputes: Why Mediation is the Better Choice

In lawsuits or binding arbitration, the resolution of a case hinges on the determination of facts by a judge or jury and the application of those facts to the law. This process is fraught with potential pitfalls: fact finders can reach incorrect conclusions, courts can misinterpret the law, and appellate courts can alter legal precedents after significant time and financial investments have been made. These inherent uncertainties make litigation a less appealing option for many.

Business Interests Over Factual Disputes

Mediation offers a stark contrast to litigation by focusing on the business interests of the parties involved. In mediation, the parties are not bound by rigid legal frameworks but are instead guided by their future goals and business relationships. This approach allows for more flexible and forward-thinking resolutions, which are particularly valuable in the fast-paced world of intellectual property. By prioritizing mutual business interests, mediation can lead to outcomes that are beneficial for both parties, fostering collaboration rather than conflict.

Preserving Relationships Through Mediation

One of the most compelling reasons to choose intellectual property mediation in disputes is the opportunity to preserve or even enhance relationships between the parties. Unlike litigation, which is inherently adversarial, mediation encourages cooperation and mutual respect. This is especially important in the realm of intellectual property, where ongoing relationships between developers, inventors, and artists can be crucial. Mediation provides a platform for parties to address their differences constructively, paving the way for future collaborations.

Creative Solutions for Complex Problems