#Pennsylvania Appellate Practice Lawyers

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Navigating the legal system can be daunting, and when it comes to appealing a court decision, the stakes are even higher. If you believe there were legal errors or significant oversights in your trial, an appeal may be your best chance at justice. To succeed in this complex process, having an experienced appellate attorney in Pennsylvania on your side is critical.

0 notes

Text

Six Bordas & Bordas Attorneys Named 2024 W.Va. Super Lawyers

Bordas & Bordas is proud to announce that six attorneys have been selected to the 2024 West Virginia Super Lawyers list. Bordas & Bordas attorneys Jamie Bordas, Linda Bordas, Geoffrey Brown, Scott Blass, Jason Causey and Richard Monahan were selected as 2024 West Virginia Super Lawyers. Jamie Bordas, managing partner of Bordas & Bordas since 2005, has been a West Virginia Super Lawyer for over a decade. Bordas spearheads Bordas & Bordas’ operations across multiple states and jurisdictions. An extremely accomplished litigator, Bordas has concentrated on the negotiation and resolution of the firm’s most complex and significant cases, including mass tort settlements of $36,500,000 and $18,500,000 and a single plaintiff settlement of over $18,000,000. In 2019, he served as lead counsel for a plaintiff at trial and presented the Oral Argument before the West Virginia Supreme Court in a case that resulted in a $16,922,000 verdict against Walmart. The verdict is believed to be one of the largest, if not the largest, verdicts in the history of Wood County, West Virginia, on behalf of a single plaintiff. He has also obtained a $10 million verdict in an insurance bad faith case in Belmont County, Ohio. In 2023, Bordas argued a case, Harris v. Hilderbrand, Slip Opinion No. 2023-Ohio-3005, before the Ohio Supreme Court where the Court unanimously ruled that police officers do not have immunity from negligent acts with K9 officers outside of duty. He also served as appellate counsel in Brown v. City of Oil City in which the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania decided in May 2023 that a contractor who has created a dangerous condition through work performed for a possessor of land may be liable to all persons suffering injuries caused by the dangerous condition. Bordas works on cases involving diverse areas of law, including insurance bad faith, toxic torts, personal injury, medical malpractice, oil and gas cases, business litigation and more. He has frequently been invited to speak to groups of attorneys on techniques applicable to trial skills, negotiation, mediation and resolution of cases as a result of his reputation for getting the best possible results for his clients. He has led the firm’s expansion into Pittsburgh and the rest of Western Pennsylvania and the opening of the firm’s Gateway Center offices in Pittsburgh. Linda Bordas, also a partner, founded Bordas & Bordas with her husband Jim Bordas when she joined his practice upon graduating from law school in 1985. She had previously worked as a hospital pharmacist and immediately applied her background to become one of West Virginia’s most successful medical malpractice attorneys. Linda has obtained numerous major verdicts and settlements in almost every area of medicine and handled appeals that have expanded the rights of patients and especially the families of children who were injured or killed as a result of negligence. She obtained a verdict of $2 Million in Davis vs. Wang, which involved the death of an infant due to medical negligence. That case also significantly affected the law in West Virginia for jury selection and juror bias in medical negligence cases and cases in general. She also obtained a $2,500,000 verdict in Klamut vs. Youssef in a case involving the death of woman as a result of medical negligence involving radiation oncology. In Andrews vs. Reynolds, she obtained a $2,760,000 verdict following the death of an infant, and helped establish law regarding loss of future wages for the survivors in a wrongful death action. In Mackey vs. Irisari, Linda obtained a $1.8 Million verdict following the failure of physicians to recognize signs of septic shock following a surgery. In Nickerson vs. Andreini, she obtained a $1 Million verdict on behalf of a young boy who required a hip replacement as a result of negligence by an orthopedic surgeon. She has also obtained multiple multi-million dollar settlements on behalf of other clients in medical malpractice cases involving various areas of medicine. Geoffrey Brown, a partner at Bordas & Bordas, has been a West Virginia Super Lawyer for 12 years. He concentrates his work on the firm’s complex litigation and medical malpractice cases. He has obtained major jury verdicts not only in medical malpractice, but also in cases of stockbroker negligence, workplace injury, and wrongful death. Brown has earned a reputation for comprehensive preparation and attention to detail in theses demanding areas of law. He has obtained multi-million-dollar verdicts in West Virginia and Ohio. Brown has also been involved in Bordas & Bordas’ business litigation department and has handled multi-jurisdictional contract disputes involving Fortune 500 companies and representation of individuals before the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) arbitration panel. Scott Blass has been a West Virginia Super Lawyer for 14 years. Blass has been litigating complex civil cases for over 30 years. He has obtained seven-figure verdicts on behalf of his clients in diverse areas of the law, including verdicts of over $4 million in a product liability case, $8 million in an auto accident case, $1.4 million in an insurance bad faith case, and $5.7 million in a medical malpractice case. Blass has also represented the families of oil and gas workers killed in fires/explosions and obtained settlements of $19 million and $19.5 million. He has been recognized as one of the foremost insurance bad faith and insurance coverage lawyers in West Virginia. Jason Causey has been a West Virginia Super Lawyer for the past seven years. Causey is a leader in consumer law in the State of West Virginia. Through aggressive litigation, he has saved dozens of homes from foreclosure. In 2011, Causey and one of the firm’s founding partners, Jim Bordas, were forced to trial against Quicken Loans in an effort to save the home of two Wheeling, West Virginia, women from foreclosure. In addition to saving the home, they obtained a verdict of nearly $3,000,000 in this predatory lending action. In 2016, Jim Bordas and Causey teamed up again for a $1,700,000 result against a municipality after a broke water-main flooded a local business. In 2017, Causey along with his co-counsel, obtained an $11,000,000 judgment in a consumer class action against Quicken Loans. Richard Monahan has been a West Virginia Super Lawyer since 2020. Monahan has been representing West Virginia citizens and consumers for more than 29 years. Among his successful trials, he has obtained verdicts and judgments of $3.9 million in a wrongful death action arising from a motor vehicle collision and $2.5 million in a retaliatory discharge case. He has also worked in complex litigation, including substantially contributing to class actions involving natural gas rights, product liability claims involving defective drugs, and other consumer claims resulting in verdicts or settlements in the hundreds of millions of dollars. Monahan is also known for his extensive appellate work. In addition to his involvement in numerous appeals before the West Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals, he also fully briefed and argued a case before the United States Supreme Court, resulting in a unanimous decision in favor of West Virginia class action plaintiffs in Smith v. Bayer Corp., 564 U.S.299 (2011). He was selected as Appellate Lawyer of the Week for his argument in that case by The National Law Journal. Super Lawyers, part of Thomson Reuters, is a rating service of outstanding lawyers from more than 70 practice areas who have attained a high degree of peer recognition and professional achievement. The annual selections are made using a patented multiphase process that includes a statewide survey of lawyers, an independent research evaluation of candidates and peer reviews by practice area. The result is a credible, comprehensive and diverse listing of exceptional attorneys. Bordas & Bordas is a plaintiff’s litigation law firm with offices in Pittsburgh, Wheeling, W.Va., St. Clairsville, Ohio, and Moundsville, W.Va. The firm’s attorneys practice throughout the region in diverse areas of law and are licensed in Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio, and Texas. Read the full article

0 notes

Text

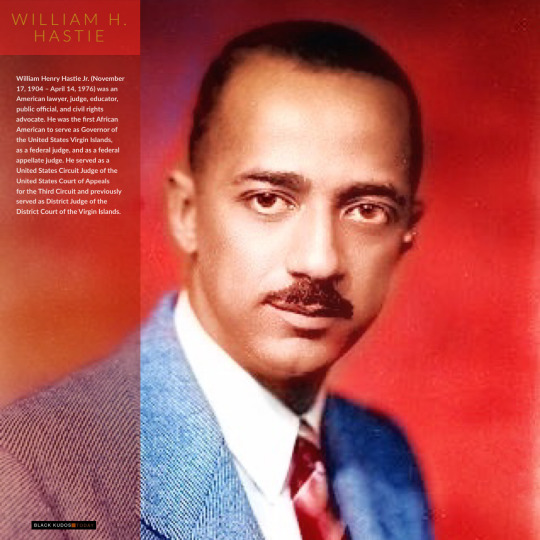

William H. Hastie

William Henry Hastie Jr. (November 17, 1904 – April 14, 1976) was an American lawyer, judge, educator, public official, and civil rights advocate. He was the first African American to serve as Governor of the United States Virgin Islands, as a federal judge, and as a federal appellate judge. He served as a United States Circuit Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit and previously served as District Judge of the District Court of the Virgin Islands.

Early life

Hastie was born in Knoxville, Tennessee, the son of William Henry Hastie, Sr. and Roberta Childs. His maternal ancestors were African American and Native American, but European American is also a strong possible mix. Family tradition held that one female ancestor was a Malagasy princess. He graduated from Dunbar High School, a top academic school for black students. Hastie attended Amherst College in Massachusetts, where he graduated first in his class, magna cum laude, and Phi Beta Kappa, receiving an Artium Baccalaureus degree. He received a Bachelor of Laws from Harvard Law School in 1930, followed by a Doctor of Juridical Science from the same institution in 1933.

Legal career

Hastie entered the private practice of law in Washington, D.C. from 1930 to 1933. From 1933 to 1937 he served as assistant solicitor for the United States Department of the Interior, advising the agency on racial issues. He had worked with Charles Hamilton Houston, former dean of the Howard University Law School, on setting up a joint law practice.

In 1937, President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Hastie to the District Court of the Virgin Islands, making Hastie the first African-American federal judge. This was a controversial action; Democratic United States Senator William H. King of Utah, the Chairman of the United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary called Hastie's appointment a "blunder."

In 1939, Hastie resigned from the court to become the Dean of the Howard University School of Law, where he had previously taught. During his tenure as a legal professor at Howard University, Hastie had become a member of Omega Psi Phi fraternity. One of his students was Thurgood Marshall, who led the Legal Defense Fund for the NAACP and was appointed as a United States Supreme Court Justice.

Hastie served as a co-lead lawyer with Thurgood Marshall in the voting rights case of Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944), in which the Supreme Court ruled against white primaries. One of Houston's sons became a name partner at their law firm.

World War II

During World War II, Hastie worked as a civilian aide to the United States Secretary of War Henry Stimson from 1940 to 1942. He vigorously advocated the equal treatment of African Americans in the United States Army and their unrestricted use in the war effort.

On January 15, 1943, Hastie resigned his position in protest against racially segregated training facilities in the United States Army Air Forces, inadequate training for African-American pilots, and the unequal distribution of assignments between whites and non-whites. That same year, he received the Spingarn Medal from the NAACP, both for his lifetime achievements and in recognition of this protest action.

In 1946, President Harry S. Truman appointed Hastie as Territorial Governor of the United States Virgin Islands. He was the first African American to hold this position. Hastie served as governor from 1946 to 1949.

Federal judicial service

Hastie received a recess appointment from President Harry S. Truman on October 21, 1949, to the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit, to a new seat authorized by 63 Stat. 493, becoming the first African-American federal appellate judge. He was nominated to the same position by President Truman on January 5, 1950. He was confirmed by the United States Senate on July 19, 1950, and received his commission on July 22, 1950. He served as Chief officer as a member of the Judicial Conference of the United States from 1968 to 1971. He assumed senior status on May 31, 1971. He was a Judge of the Temporary Emergency Court of Appeals from 1972 to 1976. His service terminated on April 14, 1976, due to his death in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, while playing golf.

Supreme Court consideration

As the first African American on the Federal bench, Hastie was considered as a possible candidate to be the first African-American Justice of the Supreme Court. In an interview with Robert Penn Warren for the book Who Speaks for the Negro?, Hastie commented that, as a judge, he had not been able to be "out in the hustings, and to personally sample grassroots reaction," but that, in order for the civil rights movement to succeed, class and race must both be considered.

In 1962, President John F. Kennedy considered appointing Hastie to succeed retiring Justice Charles Whittaker. But due to political calculations he did not. He believed that an African-American appointee would have faced fierce opposition in the United States Senate from Southerners such as James Eastland (D-Mississippi), chairman of the Judiciary Committee. Conversely, on issues other than civil rights, Hastie was considered relatively moderate, and Chief Justice Earl Warren reportedly opined that Hastie would be too conservative as a justice. Kennedy appointed Byron White instead.

Kennedy said that he expected to make several more appointments to the Supreme Court in his presidency and he intended to appoint Hastie to the Court at a later date.

Legacy

The Third Circuit Library in Philadelphia is named in Hastie's honor. In addition, an urban natural area in Knoxville, Tennessee is named in his honor.

In terms of African-American history, Hastie developed from a youthful radical to a scholarly, calm, almost aloof jurist. He said the judge always ought to be in the middle, for his basic responsibility "is to maintain neutrality while giving the best objective judgment of the contest between adversaries." As a scion of an elite black family, he reflected its integrationist viewpoint. He said, "The Negro lawyer has played and continues to play, a very important role in the American Negro's struggle for equality." A temptation to activism lurked just below his calm surface, as when he demonstrated against Jim Crow before it was fashionable to do that. When he resigned as the top aide on racial matters to the War Department in 1943, he said it was caused by "reactionary policies and discriminatory practices in the Army and Air Forces."

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Harmful Are Circuit Splits, Really?

By Lorelei Loraine, Columbia University Class of 2024

March 18, 2021

When the average teenager posts on their Snapchat story, a couple hundred people see it. That is what Brandi Levy expected would happen when she vented on her story about not making the varsity cheerleading squad at her high school in Pennsylvania. Her post, which showed her and a friend holding up middle fingers, had a vulgar caption dismissing her school and the team, though it did not name the school or make any threats. It was the kind of post her friends might tap through, feeling a twinge of pity that Levy would be stuck on junior varsity for a second year. [1]

In April, the United States Supreme Court will hear arguments about Levy’s Snap. After seeing screenshots of Levy’s story, her high school suspended her from the JV team for a year. Levy, through her parents, sued the Mahanoy Area School District for violating her First Amendment right to freedom of speech. [1] They argued that the Snap, which was posted off of school property, did not constitute the disruption of the educational environment that the landmark case Tinker v. Des Moines requires to allow schools to moderate student speech. [2] The federal district court restored Levy to the team, and the Third Circuit Court upheld the decision on an appeal. [2]

Free speech in school is a recurring theme in the Supreme Court: after Tinker, the court revisited the issue in Bethel School District v. Fraser, Morse v. Frederick, Bell v. Itawamba County School Board, and several more. Legal experts have written so prolifically on the question of whether students retain their rights to free speech in school that it is hard to imagine what the Supreme Court could add to the conversation by hearing and ruling on Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L.. The answer lies in the Third Circuit’s decision to uphold the district court’s decision that Levy’s Snap was protected by the First Amendment. In doing so, it disagreed with rulings in other circuit courts around the country, which have previously ruled that schools can punish off-campus speech. [3]

One of the main functions of the Supreme Court is to resolve so-called ‘circuit splits’ in which a circuit court hands down a decision in conflict with similar decisions made in other districts. If a party to the case appeals, the Supreme Court may choose to hear the case and ‘break the tie,’ so to speak. The Court, in its role as the court of last resort, often favors cases that create a circuit split. [4] If the Supreme Court is so eager to remedy such disagreements, circuit splits must be unequivocally bad for the law, right?

In fact, nearly as many scholars believe circuit splits are essential as believe they are destructive. The Supreme Court itself, as well as many legal experts and high school civics teachers, has argued that it is responsible for ensuring a uniform interpretation of federal law. [5] The doctrine of the rule of law depends on its equal application, regardless of who it is applied to or where they are. In some ways, the very purpose of a court is to formalize the collective interpretation of a law. However, as Professor Amanda Frost points out, many decisions that appellants call ‘splits’ address different circumstances than preceding cases. [6] Levy’s lawyers make this argument; they say that the decision is not only correct, it does not even constitute a split. [1] To allay concerns that nonuniformity undermines legitimacy, Frost points to examples of differing legal interpretations by concurrent presidential administrations—the public is perfectly willing to accept shifts under those circumstances. Further, she observes that people in different states receive different legal treatment all of the time; the United States’ federal system precludes total uniformity. [6]

Geographic specialization is not a hypothetical proposition. Circuit courts acquire de facto specializations in certain kinds of cases because of their locations: the Second Circuit in New York hears most of the country’s securities cases; the Fifth Circuit in Louisiana hears most of its immigration cases; and the Washington, D.C. Court hears most of its administrative cases. [7] Critics of circuit splits fear that claimants might abuse more subtle specializations—if a court gains a reputation for being hard on defendants, plaintiffs might be tempted to shift their case into its jurisdiction. [8] Eric Hansford, borrowing a line from economists, tested in a 2011 study whether partial specialization improved judicial quality by measuring which courts won Supreme Court approval in circuit splits most often. He found that specialization actually produces decisions that the Supreme Court agrees with more often than generalization. [7] Though his findings are limited by a somewhat narrow definition of judicial success, they indicate that geographic specificity may not be as evil as it seems on its face.

Legal scholars have lamented for decades that the Supreme Court is overburdened with petitions. It receives thousands of requests but hears only one hundred or so. [8] Each year, the proportion of cases that the Supreme Court can accept for plenary, or full, review shrinks, limiting its power to guide the judiciary on a wide variety of disputes. In recent years, the Court has turned to its ‘shadow docket’ to address cases it cannot hear in the traditional manner but still wishes to rule on. It instead uses closed door negotiations, emergency stays, and unsigned opinions to decide them. This practice is highly controversial, and Congress considered methods to curb it earlier this year. [9] Circuit splits contribute to this backlog, sometimes moving other important cases off of the Supreme Court’s docket. [8] If they are not as terrible as we assume, this may be a poor priority for the Court. Allowing some splits to stand, even temporarily, might alleviate some of the pressure that the modern Supreme Court is feeling.

Brandi Levy’s Snapchat began as a simple complaint, but it exploded into a national case that has legal scholars questioning the legal doctrine that propelled it to the Supreme Court. It is easy to justify, both practically and ideologically, why the Court would want to resolve circuit splits. However, the evidence may point to a more permissive attitude towards non-uniformity.

______________________________________________________________

[1] B.L. v. Mahanoy Area Sch. Dist., 376 F. Supp. 3d 429 (M.D. Pa. 2019) ("Mahanoy II").

[2] B.L. v. Mahanoy Area Sch. Dist., 964 F.3d 170 (3d Cir. 2020) ("Mahanoy III").

[3] Robinson, K. S. (Jan. 8, 2021). U.S. Supreme Court Takes Up Cheerleader Free Speech Dispute. Bloomberg News.

[4] Stephenson, R. (2013). Federal Circuit Case Selection at the Supreme Court: An Empirical Analysis 102 Geo. L.J. 271, 274.

[5] Wright v. North Carolina, 415 U.S. 936, cert. den. (Douglas, J., dissenting).

[6] Frost, A. (2008). Overvaluing Uniformity, 94 Va. L. Rev. 1567, 1571.

[7] Hansford, E. (2011). Measuring the Effects of Specialization with Circuit Split Resolutions, 63 Stan. L. Rev. 1145, 1150.

[8] Wallace, C. (1983). The Nature and Extent of Intercircuit Conflicts: A Solution Needed for a Mountain or a Molehill?, 71 Cal. L. Rev. 913.

[9] Millhiser, I. (Aug. 11, 2020). The Supreme Court’s enigmatic “shadow docket,” explained. Vox.

0 notes

Text

New Religious Rights Case Reminds Us Of The Complicated Legal History Of Religion And Sports

By Alexander Voorhees, Rutgers University Class of 2021

January 27, 2021

In the United States there are two cultures that have become synonymous with each other as well as have clashed with each other, these cultures are athletic competition and religious adherence. Athletes like the former quarterback Tim Tebow who became known for praying during games and the Olympic fencer Ibtihaj Muhammad who became known as the first American woman to wear a hijab in the Olympics are two examples of how religion became apart of the identity for these athletes. However, in some instances display of faith and religious observation in sports has led to legal controversy. According to the Marquette Sports Law Review, while faith and sports in professional sports has been celebrated, it is often the less publicized interscholastic sports that have put religious rights in sports to the test.[1] The Free Exercise Clause which states that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof”[2] will be an important principle that will define these following cases including one that could end up in the Supreme Court sometime this year.

Kennedy v. Bremerton School District: “Football is entertainment, not education” this is what John Whitehead of the Rutherford Institute said in response to the firing of a high school football coach in the state of Washington after an on-field prayer in 2015.[3] The coach, Joseph Kennedy, of Bremerton High School claims that the prayer he made on the 50-yard line was protected by the free speech clause as it was a private religious act. However, the Bremerton School District claimed that the coach was acting on behalf of the district at a large school event and therefore the 50-yard line was no different from a classroom. The school district also claimed in their appellate brief that “Kennedy and the Bremerton School District mutually understood that the schools coaches had extensive responsibilities, including being a mentor and role model, and being a more important figure in some students’ lives than anyone else at school, including teachers”.[4] Therefore, this would mean that not only was the coach practicing their own religious beliefs but they were pushing them onto their players and therefore it was a violation worthy of termination. Whoever the ninth circuit rules in favor of could establish how teachers and coaches practice their faith on the west coast. In regards to the Supreme Court a statement by Justices Samuel Alito, Clarence Thomas, Brett Kavanaugh, and Neil Gorsuch was made saying they would intervene if the ninth district went too far in restricting religious liberty which could lead to a significant conservative ruling on religious rights in public schools[5]. This is just one way in which religion and athletics have legally clashed.

Akiyama v. US Judo Inc: One way in which religion and athletics have come into conflict is through a participant of said sport being unable to perform a duty central to the sport itself which was perfectly exemplified in Akiyama v. US Judo Inc. In 1997 Leilani Akiyama filed a suit against the US Judo Inc for forcing fighters to bow after fights and to Japanese martial arts legends. Akiyama claimed that this violated her first amendment rights because as a Buddhist she could not worship Shinto rituals which disqualified her from judo competitions. Akiayama’s attorneys claimed that because the competitions were fought in publicly funded facilities that a display of religion such as bowing should not be required[6]. In defense, Judo Organization lawyer Richard Muller claimed that “bowing is a custom like hand-shaking that boxers do”.[7] A Washington court eventually ruled that Akiyama continue to compete in Judo without bowing and that the rule was in violation of Washington discrimination laws however the case never made it any further.[8]

Boyle v. Jerome Country Club: Another notable religious rights case was that of Boyle v. Jerome Country Club which involved religious observation interfering with an athletic event. Oftentimes in American culture there has been a connection between religious observation and athletic competition such as football Sunday in which churchgoers pray for their teams before returning home to watch the game. However, in the instance of Boyle v. Jerome Country Club they conflicted. John Boyle claimed in his suit against the Jerome Country Club that he was discriminated against for being a member of the Church of Latter-Day Saints due to the fact that they refused to make accommodations for a golf tournament when Boyle couldn’t play on Sunday due to his religion.[9] Boyle claimed that this was a violation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and that he was discriminated against. The question of the case and whether it violated the Civil Rights act and Boyle’s rights was not that the club didn't allow Boyle to play because of his religious beliefs but was regarding if they should have had to accommodate his religious observation. Eventually the US District Court of Idaho ruled that the Jerome Country Club was not in violation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 due to the fact that there were other members of the Church of Latter-Day Saints that played in the tournament and the club had legitimate business reasons to deny Boyle’s request.[10] This is a clear example of how in the case of scheduling sporting events while they might conflict with religious observation it is hard to prove it is a civil rights violation.

Menora v. Illinois High School Association: A third type of way in which religious observation and athletics clashed was through the adherence to a certain dress code for a sport. Oftentimes religious appearances deviate from the dress code of certain sports which leads to controversy. In the case of Menora v. Illinois High School Association, Orthodox Jewish men were prohibited from wearing yarmulkes fastened by bobby pins during the Illinois High School Association state basketball tournament.[11] The members of Hebrew Theological College claimed that they were being discriminated against due to their religion. While the Illinois High School Association claimed that the reason that headwear removal was required was for safety reasons this was not a compelling argument to the US District Court for the Northern District of Illinois. They ruled that the association must allow the players to participate in the state basketball tournament without requiring the removal of religious head coverings.

Sports - The American Religion: The practice of athletic competition and the practice of religion are two sacred aspects of American culture and these cases show just how much they interact with each other. The principles of the first amendment and the protections it has both for religious practice and secular institutions has allowed many unique cases to be brought to federal courts. The recent legal discussions over Kennedy v. Bremerton School District shows that there is still much to be decided in the relationship between sports and religion.

______________________________________________________________

Alexander Voorhees is a senior at Rutgers University majoring in Political Science. He will be attending Seton Hall University School of Law in Fall 2021 and is interested in practicing corporate law in his home state of New Jersey.

______________________________________________________________

[1] Scott C. Idleman, Religious Freedom and the Interscholastic Athlete, 12 Marq. Sports L. Rev. 295 (2001)

https://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1212&context=sportslaw

[2] Freedom of Religion Lincoln University Pennsylvania. 2020.

https://web.archive.org/web/20200524013011/http://www.lincoln.edu/criminaljustice/hr/Religion.htm

[3] Patrick Dorrian and Brian Flood. Praying Coach Case to Test Religious Rights of Public Workers. Bloomberg Law, January 25, 2021.

https://news.bloomberglaw.com/daily-labor-report/praying-coach-case-to-test-religious-rights-of-public-workers

[4] United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. Brief of Appellee. Joseph A. Kennedy v. Bremerton School District. September 21, 2020.

https://www.bloomberglaw.com/public/desktop/document/JosephKennedyvBremertonSchoolDistrictDocketNo20352229thCirMar1120/1?1611711649

[5] Patrick Dorrian and Brian Flood. Praying Coach Case to Test Religious Rights of Public Workers. Bloomberg Law, January 25, 2021.

https://news.bloomberglaw.com/daily-labor-report/praying-coach-case-to-test-religious-rights-of-public-workers

[6] Skolnik, Sam. Judo Champion Refuses To Bend In Lawsuit. Seattle-Post-Intelligence, December 6, 2001.

https://www.seattlepi.com/local/article/Judo-champion-refuses-to-bend-in-lawsuit-1073892.php

[7] Ibid

[8] Ibid

[9] US District Court for the District of Idaho. Boyle v. Jerome Country Club. Justia US Law, May 10, 1995.

https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/883/1422/1766833/

[10] Ibid

[11] US District Court for the Northern District of Illinois. Menora v. Illinois High School Association. Justia US Law, November 17, 1981.

https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/527/637/2368887/

Photo Credit: group10ofrlg233

0 notes

Text

Another Election Goes to Court

By David B. Rivkin Jr. and Andrew M. Grossman

Nov. 6, 2020, in the Wall Street Journal

Whoever first quipped “It’s all over but the counting” forgot about the lawyers. Over the past year, Democrats and their allies marched through state after state in an unprecedented legal campaign to upend longstanding rules of election administration. The result is more uncertainty than ever over the basic rules of voting, and an increased likelihood that races will have to be called by the courts. Although it’s too early to say for certain, that may include the presidential election.

The battle lines are being drawn in states President Trump needs to win. Pennsylvania provides a typical illustration. In 2019 the state overhauled its election code to allow everyone to vote by absentee ballot. What had been a relatively restrictive regime, with early deadlines and limited availability, was transformed into one of the most liberal in the nation, requiring only that ballots be received by the statewide voting deadline, 8 p.m. on Election Day.

Even that wouldn’t hold. After three lawsuits to extend the deadline struck out this summer, the Pennsylvania Democratic Party hit a home run on the fourth at-bat. What changed was that the secretary of state, charged with defending state law, switched sides to support her own political party. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court held that the ballot-receipt deadline, established by state law, violated the state constitution’s “Free and Equal Election Clause” and legislated a three-day extension along with a presumption of timeliness for unpostmarked ballots received by Friday. It dismissed out of hand arguments that the U.S. Constitution’s Elections and Electors clauses vest exclusive authority in state legislatures to set the rules of federal elections that can’t be rewritten by state judges or executive-branch officials.

The U.S. Supreme Court split evenly on requests by the state Republican Party and the GOP-controlled Legislature to block the lower-court ruling—effectively denying them. But both have asked the court to review the case on the merits, and the Trump campaign filed a motion on Wednesday to join that case as a party. If Pennsylvania is close, the Biden campaign will join the other side, creating a 2020 reincarnation of Bush v. Gore.

We’ve come to this pass because of Democratic politicians’ recklessness and the Supreme Court’s timidity. Democrats knew from the beginning that it was risky for state courts to shift the rules of federal elections, because voters might rely on state-court decisions later overturned under federal law. The justices also could have avoided the problem by deciding the issue before Election Day, when voters still had the opportunity to get their ballots in on time according to the rules.

In this case, Chief Justice John Roberts’s inclination to duck politically charged cases may prove self-defeating. If the court has to step in now, after the votes have been cast and counted, a political storm could become a hurricane.

Republicans filed two Election Day lawsuits in Pennsylvania challenging local election officials’ disparate treatment of defective mail-in ballots. While state law doesn’t permit mail-in voters to be notified of defects with their ballots—doing so would interfere with the timing and confidentiality of the counting process—officials in several counties apparently contacted voters to allow them to cure defects. The problem, aside from violating state law, is that this treats voters differently depending on where in the state they live, in contravention of equal-protection principles. It’s little different from the gerrymandered recount the high court rejected in Bush v. Gore.

The backdrop in Arizona is a long-running lawsuit by the Democratic National Committee challenging the state’s requirement (shared by most states) that voters cast their ballots in assigned precincts, along with its prohibition on “ballot harvesting,” the collection of ballots by parties outside the voter’s family or household. The Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of the Democrats and enjoined both policies in 2016, but the Supreme Court blocked the injunction a day later, with no recorded dissents.

The litigation dragged on. After a 10-day trial, a district court held that neither of these policies violates the Voting Rights Act. The Ninth Circuit reversed, but it stayed its own decision, anticipating that the Supreme Court would do so if it didn’t. The Supreme Court agreed last month to hear the state’s appeal, but it has yet to schedule arguments in the case. Meanwhile, Democrats stand ready to challenge the disqualification of wrong-precinct votes if that’s necessary to nudge up the numbers.

The presidential race may require legal decisions resolving such issues, as well as recounts and all the additional questions they implicate, to be decided in as many as half a dozen states. Manual recounts may be requested in several states, adding additional delays to the overall process. The Trump campaign has already filed lawsuits challenging various aspects of ballot handling and counting in Michigan and Georgia; suits in Nevada and Arizona may follow. Every case will have to be decided before Dec. 8, the federal statutory “safe harbor” deadline for states to appoint elector slates, or, at the absolute latest, by Dec. 14, when the Electoral College votes.

The media is already accusing the Trump campaign of attempting to litigate its way to victory, but practically every issue in play arises from the Democrats’ march through the courts in the run-up to Election Day. For all the cries of “disenfranchisement,” both sides agree that every lawful ballot should be counted. But after so many conflicting court decisions over the past year, what’s uncertain now is the law, and there’s no dishonor in asking the courts to say what it is.

Messrs. Rivkin and Grossman practice appellate and constitutional law in Washington. Mr. Rivkin has served in the Justice Department and the White House Counsel’s Office.

Source: https://www.wsj.com/articles/another-election-goes-to-court-11604618993?mod=e2two

0 notes

Text

3 Top Skill Sets of Civil Appeals Attorneys

Cases start in trial courts where both sides present evidence to prove their version of an incident to persuade the jury in a jury trial or the judge in a bench trial. Evidence presented is in the form of witnesses and exhibits. In appellate courts, the lawyers argue legal and policy issues before a judge or a group of judges. There are no witnesses, and no evidence is presented. Appeals deal with a request made to a higher court to review a lower court's decision when a party is unhappy with the decision or even part of a decision, made by the lower court. Given the different nature of trial and appeals cases, the skillsets of civil appeals attorneys often differ from trial attorneys.

An appeals case is more difficult to handle than a trial case. Let us take a closer look at the skill sets of civil appeals attorneys.

Argument

A civil appeals attorney should have the ability to spot the strongest points to argue instead of raising every possible issue and trying to make every possible argument in connection with the issues. The latter will dilute the appeal, and the lawyer needs to be able to focus on the specific points that he may be able to get a judge to agree on.

Writing

An appeal largely rests on written briefs by a civil appeals attorney. It should be clear and compelling. Within the first few minutes of reading a brief, the judge should get a feel for what the case is about. Therefore, one of the most important skillsets that a civil appeals attorney must possess is the ability to write effectively and efficiently, establishing the strongest point in the argument. Good writing involves not only the proper choice of words and syntax but also organization skills so that the argument’s entire structure and logic is plain.

Research

Without thorough and in-depth research, an appellate case brief can never be compelling enough to win the appeal in favor of the client. Hence, an appellate lawyer takes the often large amounts of time needed to research complicated legal matters in depth. Some pathways may have dead-ends and a civil appeals attorney should have the patience to start all over again and continue till he/she gets satisfactory and sufficient information to create a compelling brief.

Vetrano | Vetrano & Feinman LLC, primarily focused on all aspects of family law, has a respected and highly-experienced civil appeals attorney who can give a fresh perspective to the case and assess the merits of the same. Civil appeals attorney Tony Vetrano has handled appeals concerning employee benefits, contracts, estates law, family law, fraud, and real estate. To schedule a consultation for a civil appeal, or a family law matter such as divorce, child support, custody agreements or prenuptial agreements, please contact the firm.

About Vetrano | Vetrano and Feinman LLC

Vetrano|Vetrano & Feinman LLC is a top-rated law firm with outstanding divorce lawyers practicing family law in King of Prussia and serving clients in Montgomery, Chester, Delaware, Philadelphia and all surrounding counties.

Vetrano | Vetrano & Feinman LLC are dedicated divorce lawyers who practice in the courthouses of West Chester, Media, Norristown, Doylestown, Reading, Allentown, and Easton. Contact Vetrano the Pennsylvania divorce lawyers at 610-265-4441.

0 notes

Photo

Three Injunctions Entered Against New Public Charge Rule

On October 11, 2019, Judge George B. Daniels of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York issued a nationwide universal injunction against the implementation of the new public charge rule, which was slated to go into effect on October 15, 2019 [PDF version]. The suit was brought by the states of New York, Connecticut, and Vermont. The injunction will remain in effect until the district court resolves the case on the merits, or until the injunction is otherwise vacated or narrowed by an appellate court. As a result of the ruling, the preexisting public charge rules will remain in effect for the time being [see article].

The SDNY injunction is one of three injunctions against the public charge rule issued on the same day. Judge Phyllis J. Hamilton of the United States District Court for the District of Northern California issued a preliminary injunction against the implementation of the public charge rule [PDF version]. This injunction, however, only applies to implementing the rule in California, Oregon, Washington D.C., Maine, Pennsylvania, or any member of the household that includes a person from one of these states. Judge Rosanna Malouf Peterson of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Washington entered a universal preliminary injunction against the rule applying nationwide [PDF version].

The Trump Administration will likely ask appellate courts to vacate all three injunctions and any subsequent injunctions that may be entered by other Federal district courts. At this time, it is uncertain when and whether the public charge rule will take effect. We will update the website with more information on the public charge final rule litigation as it becomes available.

We published a blog about the final rule on site [see blog].

Please visit the nyc immigration lawyers website for further information. The Law Offices of Grinberg & Segal, PLLC focuses vast segment of its practice on immigration law. This steadfast dedication has resulted in thousands of immigrants throughout the United States.

Lawyer website: http://myattorneyusa.com

0 notes

Text

Pennsylvania Appellate Practice Lawyers: Your Key to a Successful Appeal

Navigating the legal system can be daunting, and when it comes to appealing a court decision, the stakes are even higher. If you believe there were legal errors or significant oversights in your trial, an appeal may be your best chance at justice. To succeed in this complex process, having an experienced appellate attorney in Pennsylvania on your side is critical.

In this blog, we’ll explore how the best appeal lawyers in Pennsylvania can be your key to a successful appeal and what you should know when selecting a top appellate attorney.

Why You Need a Pennsylvania Appellate Attorney

Appeals are not the same as trials. They don’t focus on presenting new evidence but on reviewing the legal proceedings of the original trial to identify errors or misapplications of the law. The process requires a lawyer with a deep understanding of appellate law, strong legal writing skills, and the ability to argue persuasively in front of appellate judges.

An experienced appellate attorney in Pennsylvania knows how to scrutinize trial records, identify legal mistakes, and draft compelling arguments to persuade appellate courts. With the right strategy, your attorney can help overturn wrongful convictions, reduce sentences, or achieve other favorable outcomes in civil or criminal cases.

What to Look for in the Best Appeal Lawyers in Pennsylvania

When selecting an appellate attorney, it's important to choose someone with a proven track record of success in appellate courts. Below are key qualities to look for:

1. Extensive Appellate Experience: The best appellate lawyers have a wealth of experience in appeals and are familiar with Pennsylvania's appellate courts, including the Superior Court, Commonwealth Court, and the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. Their experience gives them insight into how different judges may interpret the law.

2. Strong Analytical Skills: Appeals require careful analysis of the trial court's proceedings. A great appellate attorney must be able to identify legal errors and develop a strategy for challenging them effectively.

3. Superior Legal Writing: Appellate cases largely depend on written briefs submitted to the court. These briefs must be clear, concise, and legally sound. A skilled appellate attorney in Pennsylvania knows how to craft persuasive arguments that make a compelling case for their client.

4. Oral Argument Expertise: Oral arguments in appellate courts can significantly impact the outcome of the appeal. The best appellate attorneys are confident, articulate, and able to respond to judges' questions in a way that reinforces the written brief.

The Appellate Process in Pennsylvania

The appeals process in Pennsylvania involves several steps. It is crucial to understand the timeline and procedural requirements when working with an appellate attorney:

1. Notice of Appeal: The first step is filing a notice of appeal within a strict time frame after the trial court’s decision (typically 30 days). Missing this deadline can forfeit your right to appeal.

2. Preparation of the Record: Your attorney will obtain and review the entire trial court record, including transcripts, motions, and rulings, to determine if legal errors occurred.

3. Brief Submission: The attorney will then draft and submit a written brief outlining the legal errors that justify overturning or modifying the trial court’s decision.

4. Oral Arguments: Depending on the case, oral arguments may be scheduled where the appellate attorney will present their case before a panel of judges.

5. Court Decision: After reviewing the briefs and hearing arguments, the appellate court will issue a decision, which can affirm, reverse, or modify the trial court’s judgment.

Why Hire a Top Appellate Attorney in PA

Hiring a top appellate attorney in PA can significantly enhance your chances of success on appeal. These attorneys have honed their skills in navigating the complexities of appellate law, and their deep understanding of procedural requirements and legal precedent can make all the difference in the outcome of your case.

Many appeals fail because of technical errors in the brief or oral argument, or because the appellant’s lawyer wasn’t able to make a persuasive case. A top appellate attorney knows how to avoid these pitfalls, ensuring that your appeal is given the best possible chance of success.

Conclusion

If you or someone you love is considering an appeal in Pennsylvania, don’t leave your future to chance. The best appeal lawyers in Pennsylvania possess the knowledge, skills, and experience to help you challenge a court's ruling. Their expertise in identifying legal errors and crafting persuasive arguments can be the key to turning your case around. Contact a top appellate attorney in PA today to discuss your case and begin the appeals process with confidence.

Source:

0 notes

Text

🚨🚨CALL TO ACTION PA🚨🚨

DEMOCRATIC GOVERNOR CONSIDERING SIGNING MAJOR GOP VOTER SUPPRESSION LEGISLATION IN PENNSYLVANIA

Akela Lacy | PDEMOCRATIC GOVERNOR CONSIDERING SIGNING MAJOR GOP VOTER SUPPRESSION LEGISLATION IN PENNSYLVANIA

Akela Lacy |Published July 2 2019, 4:00 a.m. | The Intercept | Posted July 3, 2019 |

THE STATE OF Pennsylvania is on the cusp of approving a major piece of voter suppression legislation ahead of the 2020 election, despite a Democrat serving as governor.

The bill, passed largely along party lines with nearly universal opposition from Democrats in the state legislature, is on the governor’s desk. If signed into law, it would ban what’s known as “straight-ticket” voting, which allows a voter to cast a ballot for all Democrats, or all Republicans, at once. Because precincts in Democratic areas of the state, particularly in Philadelphia, are heavily under-resourced relative to the size of the voting population, banning straight-ticket voting would mean much longer lines at the polls, as each voter needs more time behind the curtain. Studies have shown the longer lines depress Democrat turnout significantly.

The ban is a longtime goal of Republican National Committee Chair Ronna McDaniel. In late 2015, Republicans succeeded in banning straight-ticket voting in Michigan, spurring litigation that lasted for a couple of years.

“I deposed Ronna Romney McDaniel,” Mary Ellen Gurewitz, a lawyer who represented Democrats in a suit to stop the ban, told the Detroit Metro Times. “She said that, when she was running for [chair] for the Michigan Republican Party in 2015, that it was her passion to eliminate straight-party voting, and that one of the reasons was that she thought it would help Republicans win.”

Donald Trump carried Michigan by 10,700 votes and Pennsylvania by 44,000 in 2016, meaning a swing of just a percentage point could be the difference between Trump’s reelection and his defeat.

The ban is included in SB 48, which passed both Pennsylvania’s state houses Thursday. The bill approves funding to update the state’s current voting machines but would remove the straight-ticket button. It would also delay Democratic Gov. Tom Wolf’s plan to decertify existing machines — part of his strategy to get counties to purchase new machines in order to boost election security ahead of 2020.

If he does nothing by late July, it will become law.

Wolf is currently reviewing the bill and has not commented publicly on it since its passage. He will decide whether or not to sign it at some point this week, spokesperson J.J. Abbott said in a statement to The Intercept. Wolf “has some concerns about components of the bills but also supports others,” Abbott said. As a second-term governor of a state critical to Democratic chances in 2020, Wolf will likely wind up on vice presidential short lists, giving his decision that much more weight. With the state legislature out of session, he has 30 days to decide whether or not to veto the bill. If he does nothing by late July, it will become law.

The governor originally supported the election reform bill because it approved a much-needed $90 million in funding for new voting machines, said state Rep. Kevin Boyle, the Democratic chair of the State Government Committee, where the bill originated. “Now the Governor has indicated he may veto it. We aren’t 100% sure though.”

“Initially he was supportive of it, and then there was enough blowback from rank-and-file Democrats and progressive organizations that were opposed to it that he seemed like he might be not inclined to support it. But now, today, we heard that he’s really — he could go either way on it,” said Boyle on Monday, in part because the measure is tied to funding for the new voting machines. While improving voting technology is a “core function of government,” Boyle said, it shouldn’t be used as leverage to ram voter suppression legislation through. “We shouldn’t be sacrificing counting all votes, particularly from traditional Democratic groups like African Americans in inner city Philadelphia and Pittsburgh.”

Wolf’s office did not respond to follow-up questions about the governor’s position on the bill.

DEMOCRATS IN THE state legislature conducted an internal analysis that they say shows eliminating the straight-ticket option would have an overall negative impact. “It’s very bad,” said Boyle. In both Michigan and Pennsylvania, groups that traditionally vote for Democrats are the ones that are most likely to vote straight ticket, Boyle said. “Not just African American communities in inner-city Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, but also new voters, younger voters, tend to disproportionately hit the straight party button. And in this decade, there’s actually been an increased use of the straight-party button, particularly in the Democratic-trending Philadelphia suburbs.” Eliminating that option, Boyle said, means that voters “might be less inclined to vote for every political contest on the ballot.”

“There’s actually been an increased use of the straight-party button, particularly in the Democratic-trending Philadelphia suburbs.”

Only nine states currently allow straight-ticket voting. Texas recently eliminated the practice, but that change won’t go into effect until 2020. Proponents of eliminating the option say it would push voters to think more critically about who they’re voting for. Michigan passed a similar law in 2015, which was upheld last year after years of litigation; critics said it would result in longer wait times in more densely populated areas, disproportionately impacting African American voters.

Eastern Michigan U.S. District Court Judge Gershwin Drain agreed with that assessment, writing last August that the bill “intentionally discriminated against African-Americans.” Citing data that showed higher rates of straight-ticket voting in black areas, and the majority of those votes going to the Democratic party, Drain wrote that the law “unduly burdens the right to vote, reflects racial discriminatory intent harbored by the Michigan Legislature, and disparately impacts African-Americans’ opportunity to vote in concert with social and historical conditions of discrimination.”

Still, a federal appellate court ordered the ban to take effect in the November election, and the U.S. Supreme Court denied a request to keep the option on the ballot.

#politics#politics and government#president donald trump#democrats#democratic party#democracy#u.s. presidential elections#2020 Presidential Election#2020 Presidential Candidates

0 notes

Text

Divorce and Family Lawyers in Philadelphia

Family lawyers in Philadelphia are those that practice family law, an area of law that deals with domestic and family matters, an area that addresses family relationships. Family lawyers, hence, deal with emotional matters, personal aspects of their clients lives.

Family law, primarily deals with,

Divorce and division of marital assets

Child custody and visitation, child protective proceedings

Adoption

Surrogacy

Paternity and guardianship

Family lawyers in Philadelphia work in courts, offices and educational settings. They offer advice to their clients, file legal documents and participate in mediation sessions. A family lawyer is

an efficient orator with strong communication skills, expert in debating, persuading and negotiating

observant, able to interact with others in highly emotional and stressful situations

great with managing time and possesses good organization skills in order to handle multiple cases/aspects of a case at the same time

Vetrano|Vetrano & Feinman LLC is a top-rated law firm with outstanding divorce lawyers practicing family law in King of Prussia and serving clients in Montgomery, Chester, Delaware, Philadelphia and all surrounding counties. Their family lawyers are attentive and sensitive to the psychological, emotional and financial problems of their clients through the course of the case. Other than the regular cases that fall under family law, the family lawyers at Vetrano Law also deal with the following:

Collaborative Law - As a collaborative law pioneer in Pennsylvania, Vetrano Law attorneys work with their clients outside of the court system to achieve an amicable divorce agreement in the best interests of the whole family.

Arbitration - When divorcing spouses cannot resolve their disputes over certain issues through mediation, skilled arbitration is provided as a powerful alternative.

Premarital agreements - Also called ante nuptial or prenuptial agreements, these give individuals control over their assets if a marriage doesn’t work or if a spouse dies

Alimony - spousal support - While a divorce is pending, attorneys often seek spousal support or alimony to make sure the income stream is shared by the divorcing couple.

Post-divorce enforcements or modifications - Vetrano Law attorneys guide their clients through modifications after divorce.

Civil appeals - Attorney Anthony J. Vetrano combines his appellate experience with the fresh perspective to appeal a case successfully that was lost at trial.

Retirement benefits in divorce - Vetrano Law identifies and values retirement benefits, prepares the court orders necessary to transfer benefits from one person to another without tax consequences.

If you are looking for family lawyers in Philadelphia, contact Vetrano|Vetrano & Feinman LLC.

About Vetrano | Vetrano and Feinman LLC

Vetrano|Vetrano & Feinman LLC is a top-rated law firm with outstanding divorce lawyers practicing family law in King of Prussia and serving clients in Montgomery, Chester, Delaware, Philadelphia and all surrounding counties.

Vetrano | Vetrano & Feinman LLC are dedicated divorce lawyers who practice in the courthouses of West Chester, Media, Norristown, Doylestown, Reading, Allentown, and Easton. Contact Vetrano the Pennsylvania divorce lawyers at 610-265-4441.

0 notes

Text

Here’s the Potential Short List for Trump’s Supreme Court Pick

Photo: Joe Ravi (cc by-sa 3.0)

President-elect Donald Trump has narrowed his potential Supreme Court picks to only the federal appeals court judges on his broad list of potential nominees, according to CNN.

CNN reported that Vice President-elect Mike Pence said the team is “winnowing” the list that “is made up of mostly federal appellate court judges.” That doesn’t automatically mean all the others are off the list yet, according to Pence.

Appeals court judges on the list of 21 are Steven Colloton, Neil Gorsuch, Thomas Hardiman, Raymond Kethledge, William Pryor, and Diane Sykes. However, the story also mentions Michigan Supreme Court Justice Joan Larsen.

Pence met with senators Wednesday about the potential pick, including Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.V.

President-elect Donald Trump has narrowed his potential Supreme Court picks to only the federal appeals court judges on his broad list of potential nominees, according to CNN.

CNN reported that Vice President-elect Mike Pence said the team is “winnowing” the list that “is made up of mostly federal appellate court judges.” That doesn’t automatically mean all the others are off the list yet, according to Pence.

Appeals court judges on the list of 21 are Steven Colloton, Neil Gorsuch, Thomas Hardiman, Raymond Kethledge, William Pryor, and Diane Sykes. However, the story also mentions Michigan Supreme Court Justice Joan Larsen.

Pence met with senators Wednesday about the potential pick, including Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.V.

“There’s been some of the people on that list who have already gone through the process here as far as approving,” Manchin told CNN. “I guess they would look at someone who has gone through, somebody who’s made it through here before would have a chance.”

Trump said during his Wednesday press conference he would be making a decision on a Supreme Court justice choice within two weeks of his Jan. 20 inauguration.

The Trump transition team did not immediately respond to an inquiry from The Daily Signal as to whether the CNN report on the short list was accurate.

Here’s a look at all of the seven appeals court judges on the list, in alphabetical order.

Michigan Supreme Court Justice Joan Larsen was named to the state’s high court by Gov. Rick Snyder, a Republican. Larsen, 48, in 2002 became an assistant attorney general in the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel. Larsen, who also taught law at the University of Michigan, received her law degree from Northwestern and clerked for the late Justice Antonin Scalia.

Judge William H. Pryor Jr., a President George W. Bush appointee, has served since 2004 on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit in Alabama, and there was a fight to get him on the court. Interestingly, Pryor’s comment about “nine octogenarian lawyers who happen to sit on the Supreme Court” deciding on the death penalty became an issue during his appeals court confirmation fight. Pryor’s confirmation came only after the May 2005 “Gang of 14” bipartisan Senate compromise, to break a Democratic filibuster of several Bush judicial nominations and also prevent the Republican leadership from invoking the so-called “nuclear option,” of curbing the filibuster. In a 53-45 vote, the Senate confirmed Pryor the following month. Pryor, 54, has a political background. He became Alabama’s attorney general in 1997 after his predecessor, Jeff Sessions, was elected to the U.S. Senate as a Republican. Trump designated Sessions to be his next attorney general. Pryor was elected in his own right in 1998 as state attorney general and was re-elected in 2002. In 2013, he was confirmed to a term on the United States Sentencing Commission. Pryor received his law degree from Tulane University.

Judge Thomas Hardiman was appointed by Bush in 2007 to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit in Pennsylvania. The Senate confirmed him 95-0 in March 2007. Hardiman, 51, previously was a federal district judge for the Western District of Pennsylvania, a position confirmed by a voice vote in October 2003. A Notre Dame graduate, Hardiman practiced law in Washington and Pittsburgh.

Judge Steven Colloton of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 8th Circuit in Iowa was appointed in 2003 by Bush. The Senate confirmed him in September 2003 by a vote of 94-1. Colloton previously served as a U.S. attorney for the Southern District of Iowa. The 53-year-old graduate of Yale Law School clerked for the late Supreme Court Chief Justice William Rehnquist.

Judge Neil Gorsuch, 49, of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit in Colorado, was appointed in 2006 by Bush. The Senate confirmed him by a voice vote in July 2006. Before that, Gorsuch was a deputy assistant attorney general at the Justice Department. The Harvard Law School graduate clerked for both current Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy and former Justice Byron White.

Judge Diane Sykes of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit in Wisconsin was named by Bush. The Senate confirmed her by a vote of 70-27 in March 2004. Sykes, 58, had been a justice on the Wisconsin Supreme Court since 1999. Before that, she was a trial court judge in both civil and criminal matters. She received her law degree from Marquette University.

One federal appeals court judge on the list of 21 who wasn’t mentioned in the CNN story is Judge Raymond Gruender, 53. He was named by Bush to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 8th Circuit in Missouri. The Senate voted 97-1 to confirm him in May 2004. He previously was a prosecutor and served as the U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Missouri. He received his law degree from Washington University in St. Louis.

With a few exceptions, such as Justice Elena Kagan and retired Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, most justices in modern times have been federal appeals court judges. The list Trump considered was intriguing because it included many state supreme court justices, as well as Sen. Mike Lee, R-Utah.

Generally, there is a reason most justices are drawn from federal appeals courts, said John Malcolm, director of the Edwin Meese III Center for Legal and Judicial Studies at The Heritage Foundation.

“Federal appeals court judges have written more legal opinions about matters that are likely to go before the Supreme Court, while state supreme court justices have ruled mostly on state law and not federal law,” Malcolm, a former deputy assistant attorney general, told The Daily Signal.

But there is also merit to having state supreme court judges, said J. Christian Adams, a former Justice Department lawyer and president of the Public Interest Legal Foundation.

“I’m big fan of state Supreme Courts just because I think they might have a better understanding of overreach by the federal government, but the list I saw, they are all good names and any one would be fantastic,” Adams told The Daily Signal.

Commentary by Fred Lucas, the Daily Signal

1 note

·

View note

Text

Navigating the legal system can be daunting, and when it comes to appealing a court decision, the stakes are even higher. If you believe there were legal errors or significant oversights in your trial, an appeal may be your best chance at justice. To succeed in this complex process, having an experienced appellate attorney in Pennsylvania on your side is critical.

0 notes

Text

Divorce Lawyer Bluffdale Utah

If you are seeking to end your marriage, contact an experienced Bluffdale Utah divorce lawyer. Under Utah law, you can seek a divorce from your spouse on various grounds. The lawyer can advise you on the grounds you can seek a divorce.

There are, basically, two legal ways to end a marriage: divorce and annulment. Of course, there are also informal ways of ending a marriage. A man (less often a woman) can simply walk out into the night and never come back. This happens often enough; and it has a real impact on families. A couple that does not want to keep on living together can also decide, for whatever reason, to ask a court for a legal separation. In older sources, separation was often called “divorce from bed and board” (a mensa et thoro); and absolute divorce was called divorce “from the bonds of marriage” (a vinculis matrimonii). “Separation” is a better and less confusing term. A legally separated couple will live apart, still officially married, but often with the same kinds of arrangements a divorced couple might have, about custody, property division, and support for the dependent spouse.

youtube

Some couples separate, as a kind of prelude to divorce. They execute a separation agreement, to be incorporated into later divorce proceedings. How many couples enter into these contracts, without the looming shadow of divorce, is hard to say—probably not very many. Legal separations likely were never very common. Legal separation and annulment are substitutes for divorce— one quite feeble, the other quite powerful. Legal separations keep a thin version of a marriage alive. Annulments are hard to get (in theory). But if a marriage is annulled, both parties can remarry; indeed, this is usually the point of an annulment. Both annulments and legal separations appeal mostly to people with religious scruples against divorce—devout Catholics, very notably.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, every state in the union, with one exception (South Carolina), had some provision for absolute divorce. South Carolina had no divorce law in the nineteenth century, and, indeed, the South Carolina Constitution of 1895 provided that “Divorces from the bonds of matrimony shall not be allowed in this State” (Art XVII, section 3). Divorce did not arrive there until 1948.

During the century, the divorce laws of the various states differed considerably. There were “easy” states and “hard” states. The general shape of divorce law, at least officially, was much the same everywhere. To get a divorce, a person had to file a lawsuit in court. A good spouse filed suit against an (alleged) bad spouse. The plaintiff would claim that the defendant, the bad spouse, had done something wrong—something which gave plaintiff, the good spouse, valid “grounds” for divorce. In the tough states, the statutory list of “grounds” was short. In the easy states, the list was longer. The defendant was supposed to file an answer to the petition. At the trial, both sides could present evidence. In the end, the judge would decide whether or not the plaintiff had made her case. Or his case; though, in fact, most of the plaintiffs were women.

youtube

As of the 1930s, every state that recognized divorce at all listed adultery as one of the available grounds. Almost all of them added desertion and cruelty; and imprisonment or conviction of a crime; and some forty jurisdictions added drunkenness. Nonsupport was grounds in some fifteen states, drug addiction in six. Other grounds were more idiosyncratic; in Florida, “habitual indulgence by defendant in violent and ungovernable temper”; in Louisiana, public defamation of a spouse; in Illinois, infecting a wife with venereal disease; in New Hampshire, refusal to cohabit for three years. In Alabama, one grounds for divorce was “commission of the crime against nature, whether with mankind or beast, either before or after marriage.” In Tennessee in the 1930s, it was grounds for divorce, quite reasonably, if “either party has attempted the life of the other, by poison or any other means showing malice.” In New Hampshire, a divorce was available when either spouse “has joined any religious sect or society which professes to find the relation of husband and wife unlawful, and has refused to cohabit with the other for six months together.” This statute, which went back to the early nineteenth century, was aimed at the Shakers, an (obviously) small religious group, which did not believe in sexual intercourse.

Divorce laws and practices of course also bore the imprint of conventional gender roles. Wives were supposed to be chaste, loyal homemakers. Men were breadwinners, with stronger sexual appetites. In Kansas, and a number of other states, as of 1935, a husband was entitled to a divorce “when the wife at the time of marriage was pregnant by another than her husband.” Nothing was said about a woman’s right to divorce, if her groom had made some other woman pregnant. Under the Maryland Code, the husband was entitled to a divorce if, unknown to him, the woman, before the marriage, had committed “illicit carnal intercourse with another man.” There was no comparable stricture about men. Many statutes gave the wife, on the other hand, the right to a divorce if the husband, for no good reason, refused to support her; in New Mexico, for example, “Neglect on the part of the husband to support the wife, according to his means, station in life and ability” was grounds for divorce. Women, on the other hand, were not required to support their husbands.

youtube

Traditional morality peeps out of the pages of the statute books. In Texas, if a man seduced a woman, and then married her to escape prosecution for seduction or fornication, he had to stay married for three years before he could sue for divorce. An old Pennsylvania law, which lasted into the twentieth century, provided that an adulterer (male or female) could not marry “the person with whom the crime was committed during the life of the former wife or husband.”16 Everywhere, to get a divorce, the plaintiff herself had to be innocent, blameless, pure. This doctrine, called “recrimination,” meant that a woman who committed adultery could not divorce an adulterous husband if she had committed adultery herself, or vice versa. Under the doctrine called “condonation,” a plaintiff also lost her case if she forgave her husband, and slept with him after he confessed his adultery. Moreover, she had no case if he had colluded with her, agreed to “give” her a divorce, and agreed not to contest; in short, if the divorce case was a fraud. As we will see, none of this reflected the real, working law of divorce.

Cruelty was the grounds of choice in many states. In Ohio, in 1930, between July 1 and December 30, almost all of some 6,500 petitions for divorce alleged gross neglect of duty, or cruelty, or both. In San Mateo County, California, in the 1950s, an astonishing 95.1 percent of all petitions alleged “extreme cruelty.” The statutes defined cruelty in various ways. For example, the Oregon Code of 1930 spoke of “cruel and inhuman treatment, or personal indignities rendering life burdensome.” In California, cruelty was defined as “the wrongful infliction of grievous bodily injury or grievous mental suffering.” Over time, regardless of statutory language, courts expanded the definition to include mental or emotional cruelty. In many states, adultery was distinctly unpopular as a ground for divorce. Of course, this tells us nothing about the incidence of adultery in real life. So much for the theory—the official law of divorce. What was the actual practice? The vast majority of divorces—perhaps 90 percent or more—were collusive and fraudulent, based on a kind of semi-legitimate perjury. In the typical case, the wife filed for divorce. The husband simply failed to respond; or in any case failed to contest. The formal official law, the law in the treatises, the law mouthed by high court judges, had absolutely no relationship to what was happening on the ground. At the level of trial courts, divorce was a matter of routine—courts simply acted as rubber stamps; couples by the thousands got their divorces; a messy system of lies and collusion was in effect; and judges, for the most part, buried their heads in the sand. In the rare contested cases, the formal law had some bite. The reported cases are all, of course, solely appellate cases. No one was likely to appeal from a consensual divorce, a collusive divorce, a divorce both parties wanted, or were at least willing to have.

youtube

Changing ideology, changing culture, and changing gender roles increased the demand for divorce. The divorce rate kept increasing in the United States—faster, indeed, than population. In 1929, there were 201,468 divorces, or, as one writer put it, about one every two minutes. From 1867 to that date, the population increased 300 percent, but the divorce rate rose by 2,000 percent. The divorce rate kept increasing in the twentieth century; there were, to be sure, ups and downs, but mostly ups. There was a bulge in divorces right after the Second World War; and a rapid rise again from the 1960s to the 1980s. In that decade, there were more than 5 divorces per 1,000 total population. After 1986, the divorce rate declined; in 2007, the rate was 3.6 per 1,000 total population. The marriage rate has also declined; and this decline, of course, has an impact on the rate of divorce. Couples who cohabit can end their relationship by packing a suitcase; no need to go to court.

Historically, many people—especially people in authority— tended to deplore divorce, and easy divorce in particular. But in the twentieth century, attitudes began to change. There were voices speaking out against the system. William N. Gemmill, a Municipal Court Judge in Chicago, in 1914 compared the “repeated assaults against divorce” to Don Quixote tilting against windmills. Some feminists, sociologists, and free thinkers agreed. It was useless to try to stem the flow of divorce suits. But the law on the books blocked the way to genuine reform. The law was stalemated. Catholic dogma refused to countenance divorce; Catholics were a powerful minority, and, in some states, close to a majority. Protestant churches accepted divorce, but only as a last resort and a necessary evil. An irresistible force (the demand for divorce) ran up against an immoveable object. The living law, however, made nonsense of the official law. Divorce law, in practice, was a fraud, a charade, a lie. Official doctrines had no impact (or very little) on living law. Consider, for example, the doctrine of “recrimination,” which we mentioned before—the rule that when the pot calls the kettle black, the court should not grant a divorce. A wife who commits adultery cannot divorce an adulterous husband.

In 1915, Tennessee created the office of “divorce proctor,” with power to “investigate the charges” in divorce cases, for a fee of $5 per case. In Oregon, the District Attorney was supposed to see that there was no fraud or collusion in divorce cases, whether or not the defendant contested. In West Virginia, the duty of the “divorce commissioner”—a person of standing in his profession and of “good moral character”—was to investigate divorce suits, and take steps necessary to prevent “fraud and collusion in divorce cases.” One proctor, W. W. Wright, in Kansas City, supposedly reduced the divorce rate in that city by 40 percent. But this, if true, must have been very exceptional. For the most part, these officials accomplished nothing. Collusive, consensual cases continued to be the norm. The courts endlessly repeated the mantra that collusion was an evil, and that courts should not grant divorces if the case even smelled like collusion. But this was, basically, nothing but talk. In Illinois, for example, in a study published in the 1950s, Maxine Virtue (wonderful name) concluded that almost all divorce cases were collusive. In the typical case, the plaintiff, a woman, accused her husband of cruelty; he beat her, slapped her, abused her. Virtue noted the “remarkable” fact that “cruel spouses” in Chicago usually struck their wives “in the face exactly twice.” The wife’s mother, sister, or brother typically backed up this story. In Indiana, until the 1950s, judges were supposed to refer to prosecutors all cases where the defendant did not show up or defend himself.

youtube