#anything from the modern jazz quartet

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

tagged by the amazing @belleandsaintsebastian to share my nine favourite albums of 2023 which was a mess to figure out because i listen to. a lot of albums

anyway,

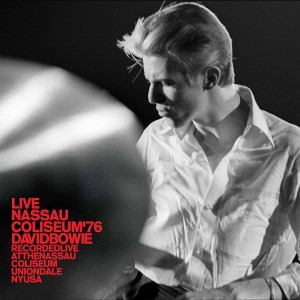

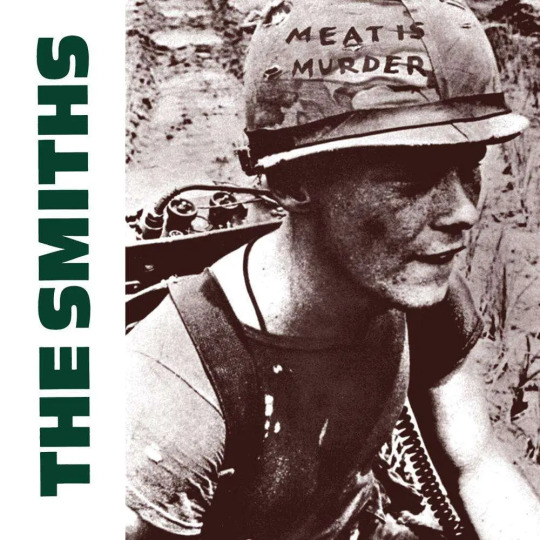

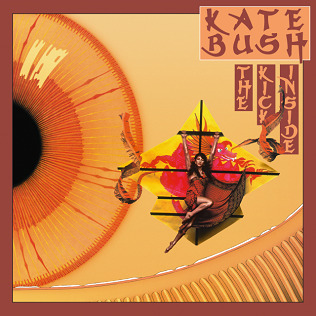

live nassau coliseum '76 - david bowie // fear of music - talking heads // meat is murder - the smiths // rough and rowdy ways - bob dylan // blue train - john coltrane // epic garden music - sad lovers and giants // the kick inside - kate bush // germ free adolescents - x-ray spex // ill communication - beastie boys

tagging @fatemy-friend @potensh @pancakehouse @shipsnsails @fall-dog and whoever else wants to do it !!

#special mention to station to station and low#i listened to a lot of bowie of course but this live album was probably my favourite out of the whole year#there's so much that didn't make the list... seventeen seconds.. humbug.. η ζωη μονο ετσι ειν' ωραια... the white album .. meddle...#live killers by queen... chris isaak... rio...#anything from the modern jazz quartet#ok i'm done. i love music

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, I was wondering if you know what music John was a fan of in the late 70’s? I’m aware of him being excited about the B52’s, and I’m assuming he liked David Bowie and Elton John’s music in part because they were his friends in addition to obviously being talented. And I think I read once that Julian turned him onto Queen but tbh that may be me misremembering a fanfic lol I just wonder if there’s anything out there that describes what John’s music tastes was in those days or whether he preferred to stick with his favorite classics; early rock and roll, girl groups ect. Like what did he think about the punk scene in NY?? Or the close harmonies a la Fleetwood Mac that dominated the charts? Just things I think about haha.

Hi, thanks for the question. I know that I skipped through a book called John Lennon: 1980 playlist by Tim English before, that may be a good source for you. Here's some random info, that I remembered where to look up. I think Julian introducing John to Queen comes from the SPIN magazine interview in '75:

[Julian] likes Barry White and he likes Gilbert O’ Sullivan. He likes Queen, though I haven’t heard them yet. He turns me on to music. I call him and he says, “Have you heard Queen?” and I say “No, what is it?” I’ve heard of them. I’ve seen the guy … the one who looks like Hitler playing a piano … Sparks? I’ve seen Sparks on American TV. So I call him and say, “Have you seen Sparks? Hitler on the piano?” and he says, “No. They are alright. But have you seen Queen?” and I say “What’s Queen?” and then he tells me. His age group is hipper to music … at 11 I was aware of music, but not too much.

But then there is also an anecdote, I think by Tony Barrow, that John didn't want to sign Queen to Apple years earlier? However that may be a lie, or John just didn't remember.

Yoko gifted John a jukebox for his birthday in '78 and apparently John filled it with the old music he liked. Elliott Mintz says there was quite some Bing Crosby. And I remember John also putting some new song by Dolly Parton in there.

"Yoko gave him this old-fashioned jukebox and John stocked it with Bing Crosby records. People kind of expected him to have rock 'n' roll records in there, but it was almost totally Crosby stuff. There were 3 songs which John played over and over. I still remember them. They were Crosby with a jazz quartet from the 50's, I think. He would banter and talk in the songs and John thought that was just the end. The songs were Whispering, I'm Gonna Sit Right Down and Write Myself a Letter and Dream a Little Dream of Me. Yeah, those were the songs, I can still see John listening to them." - Elliott Mintz

“The one modern song I remember him listening to was ‘The Tide Is High’ by Blondie, which he played constantly. When I hear that song, I see my father, unshaven, his hair pulled back into a ponytail, dancing to and fro in a worn-out pair of denim shorts, with me at his feet, trying my best to coordinate tiny limbs.” - Sean Lennon

One night we were playing at Max's (Kansas City) in New York City, and I was waiting for everyone to leave the club so I could go back in and pick up my gear. We were sitting in the van waiting and John Lennon and Ian Hunter from Mott the Hoople came staggering out and looked over. John Lennon saw it was me and stuck his head in the window. He was kind of drunk and stuck his face right against mine and went 'yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah' because he recognized it (Devo's song Uncontrollable Urge) as being an updating of She Loves You. That was one of my most exciting moments ever. - Mark Mothersbaugh on John coming to a DEVO gig in '77

PB: John, what is your opinion of the newer waves? Lennon: I love all this punky stuff. It's pure. I'm not, however, crazy about the people that destroy themselves. Playboy interview, 1980

I like pop records. I like Olivia Newton-John singing "Magic" and Donna Summer whatever the hell she'll be singing. I like ELO singing "All over the World". I can dissect it and criticize it with any critic in the business...But without any thought I enjoy it! That's the kind of music I like to hear. - John

John Lennon raced into Yoko Ono’s home office in the mammoth old Dakota building with a copy of Donna Summer’s new single, “The Wanderer.” “Listen!” he shouted to us as he put the 45 on the record player. “She’s doing Elvis!” I didn’t know what he was talking about at first. The arrangement felt more like rock than the singer’s usual electro-disco approach, but the opening vocal sure sounded like Donna Summer to me. Midway through the song, however, her voice shifted into the playful, hiccuping style Elvis had used on so many of his early recordings. “See! See!” John shouted, pointing at the speakers. The record was John’s way of saying hello again after five years. [...] It was just weeks before his death in December of 1980, and his playing the Summer record was an endearing greeting -- and one that was typical of John. Of the hundreds of musicians I’ve met, John was among the most down-to-earth. Corn Flakes with John Lennon (And Other Tales From a Rock ‘n’ Roll Life) by Robert Hilburn

"I'm aware of ... Madness. "Don't do that. Do this." (As on the spoken word intro to "One Step Beyond".) I think that is the most original thing actually because it's so peculiar. ... Out of all that mob I think that was one of the most original sounds. Very good drumming, very good bass and all of that." Andy Peebles interview

And things I don't have quotes for right now: I remember Bob Gruen had given John some video compilation of punk bands, that John enjoyed watching. In one of the last interviews John said Hungry Heart by Bruce Springsteen was a great song. There are the albums John asked Fred Seaman to buy on his shopping lists. Some are printed in The John Lennon Letters (Though I'm not sure that means he liked them, but at least was interested in.) Lot's of Bob Dylan talk in the diaries and parodies. Many anecdotes about reggae bands. In the Double Fantasy studio recording John references quite some songs and artists, when he tells the musicians what they are aiming for in the songs.

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

In fact the backstory of Tom in the film is that in the offshore world of narco trafficking cartels, they have the budgets to buy the best and they do. Particularly since the end of the Cold War, when that market has become available, people that are ex-KGB, ex-Stasi, as well as Brits and Americans from special forces; Israelis.

Since we’re only in these ten hours, we’re only seeing a fraction of a whole life. And since we’re only ten hours, the challenge is can I design those fractions that they become glimpses… that you kind of sense the person. To do that, one has to invent the history of Vincent, the history of Max, and then to choose those details to put in the ten hours of tonight. [...] The film does not do what a life experience of these ten hours would not do, which is to have exposition or to travel backwards in time via flashbacks or any of those other devices. But instead just to keep it as immediate, into this presence, and yet to have a greater degree of knowingness into their lives.

Vincent is somebody who’s decisive… who’s embraced force as a way of controlling his environment, as a way of — and I don’t think Vincent is actually actively aware of this — but it’s a way of controlling an environment so that bad things don’t happen to him. He, consequently, can be someone who’s improvisational, he’s highly trained, he takes action, he has opinions. Max is exactly the opposite.

The other aspect about Vincent’s appearance is again, and building the character, how to make these two characters be oppositional, what Vincent’s chosen to wear, it tells us things — I believe that audiences are much brighter than they are aware of, there’s a lot of information they take in on a feeling level. There’s a cut to his suit that says perhaps it was custom tailored, but not in Milan or London or New York, in my mind it was Kowloon. The thing about his hair, scars on his hand, scars on his face.

In effect he’s a rough trade in a good suit. Prematurely gray, kind of a steely aspect to him. Those are design issues that are there to tell us, tell the audience, tell YOU things about who he is on a feeling level, not anything that is didactic or spoken to you. It was tricky to arrive at some of these looks and some of these issues because — and this is also the challenge of the film that made it very exciting to me, to do it and want to do it — which is that when you compress the time frame, of a narrative and it’s under two hours, and you’re just in one locale, you’re one night, it also means there’s going to be one suit and one wardrobe change and everything’s going to become inordinately important. Driving a race car, a very small input in steering has a radical effect. So the slightest change, because it’s cumulative, becomes a big deal.

But the deep work that goes into this kind of thing is in fact how did Vincent become Vincent. And Tom and I did a lot of work in trying to understand where this guy came from. If he was in a foster home for part of his time, if he had an institutionalized childhood. And if he was back in the public school system by age 11, that would have been sometime in the 1970s. He would have been dressed very awkwardly. He probably would have been ostracized, because he would have looked odd and you know… the brutality of preteens and early adolescents.

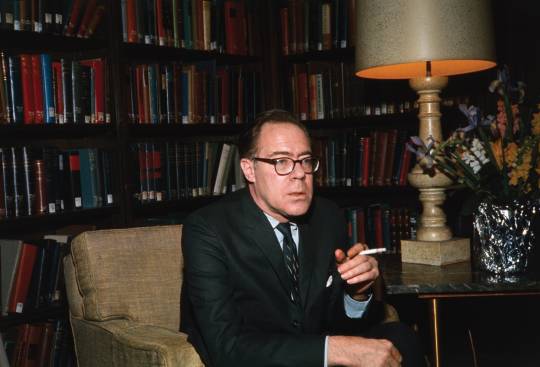

We postulated an alcoholic, abusive father who was culturally very progressive. He was probably part of Ed Solowski’s steelworkers local in Gary. He was a Vietnam veteran. He had friends who were African American, the South Side of Chicago, the Checkerboard Lounge is 30 minutes away in a cab, Calumet Skyway. So the father in his sixties and early seventies was probably an aficionado of jazz, there was a great jazz scene on the South Side of Chicago, modern jazz quartet… it’s almost as if the father blamed the son I.E. Vincent for what happened to the mother, and the father drank and Gary was being reduced to — I mean it looked like Dresden at the end of the war. The father never tutored the boy in jazz. But the boy extolled the virtue of knowing about jazz because he heard his father talk about jazz, not to him, but to other people. And that’s why he knew about jazz, and that’s why he learned about jazz.

Now his father, Vincent’s father, never tutored Vincent about jazz because he had rejected his son. And ignored him. It was something that got constructed as backstory and the work I did with Tom during pre-production and understanding every aspect of the character of who Vincent was, much more than it appears in the text of the film so that the fractions of Vincent-ness that we have IN the text of the film, within these ten hours, could resonate with the totality of a life the same as they would with anybody you met. We all bring a whole history with us into the moment of the present.

#excerpted collateral director's commentary as transcribed by yours truly :)#collateral 2004#collateral (2004)#tom cruise#jamie foxx#michael mann

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

SILY's Top Albums of 2024

Much like 2016, last year felt like a turning point in American history, world history, and human history. The rich and powerful got more rich and powerful than ever, right-wing politics and media triumphed, and the climate crisis raged on. Increasingly, the albums that resonated with us turned out to reflect the ills of the world back at it, or, just as important, show that art and creativity can thrive in spite of them. Here are 10 of our favorites.

A. Savage - The Loft Sessions (Rough Trade)

While visiting Chicago on tour in 2023, A. Savage recorded four tracks at Wilco's recording studio, The Loft, three covers and a new rendition of his “Wild, Wild, Wild Horses”. The opening track, “I Can’t Shake the Stranger Out of You” is a cover of a Lavender Country song from his 1973 self-titled debut, a record famously regarded as the first ever queer country album. Savage’s version became my most played song of the year on Spotify, and somewhere in my year-end playlist is the original version. The Loft Sessions is a stellar EP, and something I proudly listen to seeing that I saw A. Savage play at the Empty Bottle only a few hours after he had recorded it. “I Can’t Shake the Stranger Out of You” focuses on odd relationships that can’t seem to progress towards anything truly substantial, whereas the closing track “Wild Horses” contains depth, history, and emotional vulnerability. The four songs on The Loft Sessions are digestible, relatable, and easy to listen to while you prepare your coffee in the morning, an activity that can cover the EP's 13 minutes, depending on your hardware. - Keith Miller

Geordie Greep - The New Sound (Rough Trade)

For his debut solo album after the dissolution of a beloved band, Black Midi frontman Geordie Greep dove headfirst into the id of society's most prurient men. The New Sound is inspired by Greep's experiences out on the town, meeting drunken strangers who revealed to him their gross escapades, and it's got the coked-out, Steely Dan-esque, Latin jazz-rock fusion aesthetic to match. But Greep's also an astute observer of the toxically masculine online culture that pervades the world, finding humor, pathos, and absurdity in it alongside the necessary disgust. The narrators of his songs are far more pathetic and narcissistic than the earnest losers of MJ Lenderman's Manning Fireworks: It's not just that they're using women, but they're obsessed with their own perspective of the world, their own suffering. "You talk about yourself in the past tense," Greep smirks on album opener "Blues", giving a voice to the poet laureate of self-importance. Ever the writer himself, though, Greep's most brilliant moments are when he twists the knife, revealing that the Casanova of "Holy, Holy" is asking the sex worker he hired to make him feel taller, that the unfaithful man in a loveless marriage on "The Magician" is hiding from both his wife and his mistress. The New Sound's final track is a cover of a song made famous by Frank Sinatra, "If You Are But a Dream"; when Greep sings, "If you're a fantasy / Then I'm content to be / In love with lovely you / And pray my dreams come true," he conveys the desperate yearning that's always been a part of men in modern Western society. Greep's self-described new sound is anything but new, even if his version has more bodily fluids. - Jordan Mainzer

Jlin - Akoma (Planet Mu)

The producer from Gary, Indiana doesn't exist on the fringes of just footwork, but of genre as a whole. On Akoma, Jlin proudly wears her influences beyond collaborating with legends like Björk and Philip Glass. Her trademark skittering, journeying percussion gives way to more propulsive beats and layers. On "Summon", Jlin's strings form a gestalt beat that never actually drops, as minimalist as Steve Reich. "Challenge (To Be Continued II)"'s hand drums blanket booming hip hop bass and rolls inspired by HBCU marching bands. Kronos Quartet offer their chopped strings on "Sodalite"; when Jlin speeds them up, it almost sounds like a fiddle tune. Akoma exemplifies her uncanny ability to tell a story with varying textures of abstract music, each song its own symphony. - JM

King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard - Flight b741 (p(doom))

Across its ten tracks and roughly 40-minute runtime, King Gizzard delivers an enticing album that’ll pair well with cookouts, yard work, parties at a lake house, and all around busy and sweaty times outdoors. From its harmonic vocals and borderline goofy lyrics down to the various instrumentation of clanging pianos, bumping bass beats, and uplifting guitars, my biggest complaint about Flight b741 is that it didn’t come out sooner. Grab your sunglasses and put on a pair of jorts–anyone who’s claimed to like “Dad Rock,” this album is for you.

Read the rest of our review of Flight b741 here.

MGMT - Loss Of Life (Mom + Pop)

MGMT’s fifth studio album (6th album if you count 2022’s 11•11•11) is a fantastic addition to the psychedelic duo’s sound. Each song brings something new to the table, ranging from 90’s nostalgia in “Bubblegum Dog” to Meddle-style slow burn on “People In The Streets.” Band members Andrew VanWyngarden and Ben Goldwasser began writing each song on an acoustic guitar, which gives the album a slight singer-songwriter feel that isn’t as present on their past albums, especially not on their previous record, 2018’s Little Dark Age. MGMT have proven once again that they are a band with staying power. - KM

Neil Young & Crazy Horse - Fu##in' Up (Warner/Reprise)

One of the most ass-ripping recordings of last year came from when a classic rocker with a likely net worth of hundreds of millions of dollars played at a birthday party for one of the richest men in Canada. A cynic could call this a prescient glimpse into a future ruled by technocrats, but I choose to marvel at how Neil Young & Crazy Horse can just up and transform some of their most beloved material into something even grungier and more distorted, and not care what billionaire Dani Reiss or his friends think. Fu##in' Up is, essentially, a live version of their classic 1990 record Ragged Glory, each track newly titled from a lyric from its respective track, save for the cover of Don and Dewey's "Farmer John". ("Mother Earth (Natural Anthem)", Ragged Glory's final track, is also absent.) Young presents it warts and all, his shaky voice and the ramshackle band stumbling through "City Life" as if they gave their instruments to the members of Pavement. Nonetheless, Nils Lofgren's guitars shriek with impunity, and Young's riffs clang throughout "Broken Circle". The band adds some new features to the Ragged Glory originals, namely Micah Nelson banging away on piano on "Feels Like a Railroad (River of Pride)" and "Walkin' in my Place (Road of Tears)". Above it all, though, Young remains in control, leading the band through a 50% longer "A Chance on Love" and a particularly patient "Valley of Hearts", Ralph Molina's crisp snares thwacking with might, sounding like the only thing dragging the rest of the players through a river of molasses. Without much crowd noise or stage banter on the record, you can easily listen to Fu##in' Up and picture the band jamming in the practice room. - JM

Pa Salieu - Afrikan Alien (Warner UK)

"I been gone for a while, but I still make it back to you," British rapper Pa Salieu sings on "Belly", the first single he released after serving 21 months in prison. He's talking to music listeners, fans, even the world, but most importantly, he's talking to his family, paying tribute to the loving act of helping provide. The song's Afropop grooves are subdued, but confident, subtleties that remarkably pervade Afrikan Alien, his second mixtape. Whether it's the cool shuffle of "Soda", cooing vocals, scraping guitars, and dexterous hand drums of "Round & Round", or the string, horn, and chorus-laden "YGF"--standing for "young, great, and free"--the highlights of Afrikan Alien forego bombast in favor of quiet boldness. "Afrikan di alien, moving like he's nomadic," Salieu raps on the title track, referring to the past two years of his life when he was moving from jail to jail. It contextualizes the release, and what he now appreciates: that home is precious and irreplaceable. - JM

Porridge Radio - Clouds In The Sky They Will Always Be There For Me (Secretly Canadian)

Dana Margolin has come out the other side of exhausting touring, a breakup, and a debilitating sense of “What now?” with Porridge Radio’s best record yet. For the Brighton quartet’s fourth studio album Clouds In The Sky They Will Always Be There For Me, Margolin returned to her roots as a writer and performer to alleviate burnout, embracing poetry and workshopping the songs solo like she used to do at open mic nights. She dove headfirst into not-yet fully formed material via the rawness of her emotions. It allowed her, the band (keyboardist/backing vocalist Georgie Stott, drummer/keyboardist Sam Yardley, bassist Dan Hutchins) and indie rock producer du jour Dom Monks to foster a live recording environment that allowed for intimacy and intense vulnerability.

Read the rest of our review of Clouds In The Sky They Will Always Be There For Me here.

Waxahatchee - Tigers Blood (Anti-)

More than ever, Waxahatchee’s songs are easy to sing along to; despite complex turns of phrase, Katie Crutchfield keeps her words metaphorical enough to stand out, abstract enough to be relatable, direct enough to be iconic. The qualities, in conjunction with her and her backing band’s performance, lead to some breathtaking moments. “You drive like you’re wanted in four states / In a busted truck in Opelika,” she sings over Spencer Tweedy’s drum roll on the rolling “3 Sisters”, right before the song’s forbearing beat drops. On “Bored”, she belts the song’s chorus–“I can get along / My spine’s a rotted two by four / Barely hanging on / My benevolence just hits the floor / I get bored”–alongside MJ Lenderman’s sharp riffs, Tweedy’s pummeling drums, and Nick Bockrath’s wincing pedal steel. In context of the song’s inspiration–a friendship that ended badly–Crutchfield’s admissions hit harder.

Read the rest of our review of Tigers Blood here.

Vampire Weekend - Only God Was Above Us (Columbia)

When I was in high school, I became a die hard Titus Andronicus fan. I still am, in fact: That's a band I can’t shut up about. I remember in the summer of 2014, Titus frontperson Patrick Stickles held a live stream press conference in which he announced his 7x7 series where he released seven 7-inch records each 7 weeks apart from one another. (I never got the second installment in the mail and had to buy it at a concert--thanks, Pat.) During this press conference Stickles showed us his collection of 7-inch records, one of which was a B-side of “Diane Young”, a single from Vampire Weekend’s third record, Modern Vampires of the City. Stickles, after briefly mentioning “Diane Young”, apologized slightly, as if he didn’t want people to know that he had it. Ever since then, I’ve wondered what the dynamic of Vampire Weekend's music is among music nerds. For the record, I love it, but I always forget about them a few months after they release a new album. Not Only God Was Above Us. It's incredible; it might be their best record in their discography. It feels like a more tight knit version of Modern Vampires of the City. I started writing out all of the standout songs, but the list was getting too long. - KM

#album review#a. savage#geordie greep#jlin#planet mu#paul wiancko#king gizzard & the lizard wizard#mgmt#mom + pop#pa salieu#porridge radio#secretly canadian#neil young & crazy horse#waxahatchee#spencer tweedy#vampire weekend#the loft sessions#rough trade#wilco#the loft#lavender country#empty bottle#the new sound#black midi#steely dan#mj lenderman#manning fireworks#frank sinatra#akoma#björk

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A SERENE JAZZ MASTERPIECE TURNS 65

The best-selling and arguably the best-loved jazz album ever, Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue still has the power to awe.

MARCH 06, 2024

At a moment when jazz still loomed large in American culture, 1959 was an unusually monumental year. Those 12 months saw the release of four great and genre-altering albums: Charles Mingus’s Mingus Ah Um, Dave Brubeck’s Time Out (with its megahit “Take Five”), Ornette Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz to Come, and Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue. Sixty-five years on, the genre, though still filled with brilliant talent, has receded to niche status from the culture at large. What remains of that earthshaking year in jazz? “Take Five” has stayed a standard, a tune you might hear on TV or on the radio, a signifier of smooth and nostalgic cool. Mingus, the genius troublemaker, and Coleman, the free-jazz pioneer, remain revered by Those Who Know; their names are still familiar, but most of the music they made has been forgotten by the broader public. Yet Kind of Blue, arguably the best-selling and best-loved jazz album ever, endures—a record that still has the power to awe, that seems to exist outside of time. In a world of ceaseless tumult, its matchless serenity is more powerful than ever.

On the afternoon of Monday, March 2, 1959, seven musicians walked into Columbia Records’ 30th Street Studio, a cavernous former church just off Third Avenue, to begin recording an album. The LP, not yet named, was initially known as Columbia Project B 43079. The session’s leader—its artistic director, the man whose name would appear on the album cover—was Miles Davis. The other players were the members of Davis’s sextet: the saxophonists John Coltrane and Julian “Cannonball” Adderley, the bassist Paul Chambers, the drummer Jimmy Cobb, and the pianist Wynton Kelly. To the confusion and dismay of Kelly, who had taken a cab all the way from Brooklyn because he hated the subway, another piano player was also there: the band’s recently departed keyboardist, Bill Evans.

Every man in the studio had recorded many times before; nobody was expecting this time to be anything special. “Professionals,” Evans once said, “have to go in at 10 o’clock on a Wednesday and make a record and hope to catch a really good day.” On the face of it, there was nothing remarkable about Project B 43079. For the first track laid down that afternoon, a straight-ahead blues-based number that would later be named “Freddie Freeloader,” Kelly was at the keyboard. He was a joyous, selfless, highly adaptable player, and Davis, a canny leader, figured a blues piece would be a good way for the band to limber up for the more demanding material ahead—material that Evans, despite having quit the previous November due to burnout and a sick father, had a large part in shaping.

A highly trained classical pianist, the New Jersey–born Evans fell in love with jazz as a teenager and, after majoring in music at Southeastern Louisiana University, moved to New York in 1955 with the aim of making it or going home. Like many an apprentice, he booked a lot of dances and weddings, but one night, at the Village Vanguard, where he’d been hired to play between the sets of the world-famous Modern Jazz Quartet, he looked down at the end of the grand piano and saw Davis’s penetrating gaze fixed on him. A few months later, having forgotten all about the encounter, Evans was astonished to receive a phone call from the trumpeter: Could he make a gig in Philadelphia?

He made the gig and, just like that, became the only white musician in what was then the top small jazz band in America. It was a controversial hire. Evans, who was really white—bespectacled, professorial—incurred instant and widespread resentment among Black musicians and Black audiences. But Davis, though he could never quite stop hazing the pianist (“We don’t want no white opinions!” was one of his favorite zingers), made it clear that when it came to musicians, he was color-blind. And what he wanted from Evans was something very particular.

One piece that Davis became almost obsessed with was Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli’s 1957 recording of Maurice Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G. The work, inspired by Ravel’s triumphant 1928 tour of the U.S., was clearly influenced by the fast pace and openness of America: It shimmers with sprightly piccolo and bold trumpet sounds, and dances with unexpected notes and chord changes.

Davis wanted to put wide-open space into his music the way Ravel did. He wanted to move away from the familiar chord structures of jazz and use different scales the way Aram Khachaturian, with his love for Asian music, did. And Evans, unlike any other pianist working in jazz, could put these things onto the keyboard. His harmonic intelligence was profound; his touch on the keys was exquisitely sensitive. “I planned that album around the piano playing of Bill Evans,” Davis said.

But Davis wanted even more. Ever restless, he had wearied of playing songs—American Songbook standards and jazz originals alike—that were full of chords, and sought to simplify. He’d recently been bowled over by a Les Ballets Africains performance—by the look and rhythms of the dances, and by the music that accompanied them, especially the kalimba (or “finger piano”). He wanted to get those sounds into his new album, and he also wanted to incorporate a memory from his boyhood: the ghostly voices of Black gospel singers he’d heard in the distance on a nighttime walk back from church to his grandparents’ Arkansas farm.

In the end, Davis felt that he’d failed to get all he’d wanted into Kind of Blue. Over the next three decades, his perpetual artistic antsiness propelled him through evolving styles, into the blend of jazz and rock called fusion, and beyond. What’s more, Coltrane, Adderley, and Evans were bursting to move on and out and lead their own bands. Just 12 days after Kind of Blue’s final session, Coltrane would record his groundbreaking album Giant Steps, a hurdle toward the cosmic distances he would probe in the eight short years remaining to him. Cannonball, as soulful as Trane was boundary-bursting, would bring a new warmth to jazz with hits such as “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy.” And for the rest of his career, one sadly truncated by his drug use, Evans would pursue the trio format with subtle lyrical passion.

Yet for all the bottled-up dynamism in the studio during Kind of Blue’s two recording sessions, a profound, Zenlike quiet prevailed throughout. The essence of it can be heard in Evans and Chambers’s hushed, enigmatic opening notes on the album’s opening track, “So What,” a tune built on just two chords and containing, in Davis’s towering solo, one of the greatest melodies in all of music.

The majestic tranquility of Kind of Blue marks a kind of fermata in jazz. America’s great indigenous art had evolved from the exuberant transgressions of the 1920s to the danceable rhythms of the swing era to the prickly cubism of bebop. The cool (and warmth) that followed would then accelerate into the ’60s ever freer of melody and harmony before being smacked head-on by rock and roll—a collision it wouldn’t quite survive.

That charmed moment in the spring of 1959 was brief: Of the seven musicians present on that long-ago afternoon, only Miles Davis and Jimmy Cobb would live past their early 50s. Yet 65 years on, the music they all made, as eager as Davis was to put it behind him, stays with us. The album’s powerful and abiding mystique has made it widely beloved among musicians and music lovers of every category: jazz, rock, classical, rap. For those who don’t know it, it awaits you patiently; for those who do, it welcomes you back, again and again.

James Kaplan, a 2012 Guggenheim fellow, is a novelist, journalist, and biographer. His next book will be an examination of the world-changing creative partnership and tangled friendship of John Lennon and Paul McCartney.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

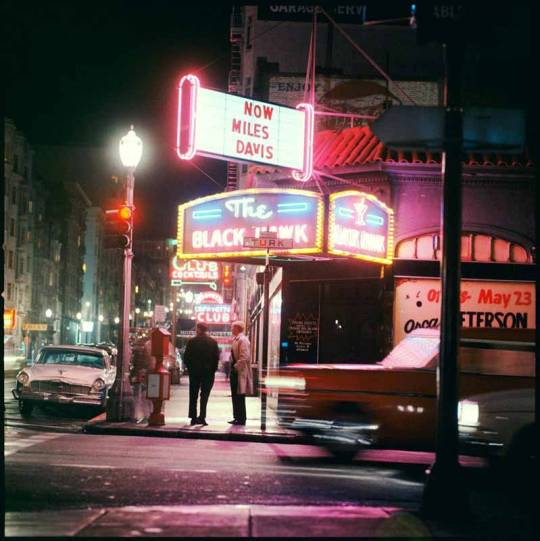

THE WEEKEND I SAW MILES PLAY THE BLACKHAWK

SHORT FICTION

It was April of 1961. I’d read in The Chronicle that Miles Davis had an engagement at The Blackhawk scheduled for the 21st and 22nd – a Friday and Saturday night. I’d been dating a girl named Marla from the secretarial pool at work for the past couple of months, and I called her as soon as I found out about the show and invited her to go. She agreed, although she wasn’t really a jazz lover.

Thursday afternoon, Marla came into my office and told me she couldn’t go after all. When I pressed her for a reason, she said something vague about friends visiting from out of town. This was the third time in the past month she’d cancelled on me. So I decided to go alone.

I left work a little early Friday, and dropped by the barbershop for a haircut. Then I headed home, made myself a quick dinner, put on a jacket and slacks, and my favorite tie – the one with the musical notes on it – and called a cab. The cabbie was a bit late in arriving, but I hopped in, and when he asked, “Where to?” I told him, “The Blackhawk.”

Traffic was heavy with people in the city for a Friday night. The skies were overcast and threatening rain, and I’d left my umbrella at the office. The cabbie chattered the whole way about whether or not The Giants had a shot at the pennant that year. I didn’t think so, but he insisted that since they had the best centerfielder in baseball, they couldn’t miss.

When we pulled up to the club, the line wound all the way down the block. I jumped out, paid the driver and rushed to the back of the line – hopeful that the show wouldn’t be sold out by the time I got to the door. A few minutes later, another cab arrived and three men in hats, and raincoats - two of them clutching notebooks, and pencils, and the other a camera - got in line behind me. I found out from their conversation that one of them was a reporter and another, a photographer from Time magazine. The third worked at The Chronicle. I guess they were there to interview Miles after the show. They didn’t seem to know much about jazz, and even less about the club. Apparently they’d called for reservations, and were told The Blackhawk didn’t take reservations. Guido, the owner, had very strict rules about that. You took your chances. Which is why, when I was old enough my dad use to invite me to go with him instead of taking my mom. She hated waiting in line for anything. Come to think of it, she didn’t much like jazz either. (Women are funny that way.) The first jazz show I saw at The Blackhawk with my dad was The Modern Jazz Quartet. The acoustics were so good at The Blackhawk that they didn’t even use microphones that night. But you could hear every note. I couldn’t get over that.

Anyway, I got inside just minutes before the first set began, and only a few minutes after the skies opened up and the rain came pouring down. I was given what looked to be the last available table in the far corner left of the stage. Millie, a waitress who’d been at the club for years (my dad always flirted with her, and left her the biggest tips) took my drink order, and I settled in to hear the first set.

From my vantage point, I could see pianist Wynton Kelly’s back. I couldn’t see Jimmy Cobb behind his drum kit at all. But I had an unobstructed view of both Miles, and his sax player Hank Mobley. I could only see bassist Paul Chambers when Mobley wasn’t out front soloing. Miles was wearing a beautiful blue, pinstriped suit. I made a mental note to go shopping that weekend for one just like it.

Miles played his standard show that night. He used the mute quite a bit, and the rhythm section was in the pocket all night. They sounded good, although some of the spark that was there when I saw the group with John Coltrane was missing. Mobley could play, but Coltrane’s were big shoes to fill.

At any rate, Millie kept the drinks coming, and at one point I noticed the roof was leaking next to my table. Millie brought a tin pan and set it on the floor to catch the water. Sometimes the water dripped in rhythm to the music.

Between the first and second sets, Miles wandered onto the floor and was chatting amiably with several people I took to be regulars. But I noticed he would sign the occasional autograph. So the next time Millie came to the table, I asked to borrow her pen and I grabbed one of the club’s matchbooks off the table, and wandered over to where Miles was standing. He finally glanced my way, and I couldn’t speak. I just pushed the matchbook and pen in his direction, and he quickly scribbled his name on it, handed it back to me and went on with his conversation. I pocketed the matchbook and slipped back to my table.

The second set began with “All of You”, and the whole band seemed more relaxed and in the groove than they were during the first set. I stayed for the third set as well, and when it was finally over I went to the bar to settle my bill. Susan, the bartender’s wife, rang me up. I heard her tell another guy they were expecting an even bigger turnout the next night.

I was there Saturday night as well. The band played four sets, and included “Two Bass Hit”, and “Someday My Prince Will Come”. And they were even better than they were the night before. As I was leaving Saturday night I noticed some recording equipment being dismantled and packed, and when I asked Guido about it, he told me that Miles’ record label Columbia had recorded both nights for an album that would come out in the fall.

I still have the original album I bought at the record shop around the corner from my building. I’ve nearly worn it out in the years since.

I moved east to Chicago in 1965. There were a lot of great clubs there as well, but none with the ambience of The Blackhawk. There was just something about that place. Marla has no idea what she missed that weekend of April 1961 when Miles Davis came to town. She broke it off with me a week later, and I heard she was seeing some guy named Jim from Finance. But I still have my matchbook with Miles’ name on it, and I can listen to the music anytime I want. Sometimes I even think I can hear water dripping in that pan on the floor next to my table.

© 2023

1 note

·

View note

Text

had a dream i was trying to tell someone about nu jazz. it was like yeah, this is a polish group called Skalpel, they’ve got some really huge grooves and understated jazz instrumentation. lots of interesting breaks and samples. really cool and imo a good and simple intro. and this is Tortoise, they came up as one of the groups pioneering "post-rock" music, with post-rock used here in the most literal sense, before the genre became synonymous (and saturated) with lengthy, cinematic pieces with huge crescendos and emotional climaxes and more ambient interludes—and stagnating under its own weight rather quickly. the "post-" prefix comes from the way that they used traditional rock instruments like drums, bass (tortoise actually had two drummers, two bassists, and a percussionist, which is an insane lineup), guitars to create music that is very much not rock, and in large part a response to it, alongside, in particular, bands like Slint and Don Cab[allero]—although how "political" or "academic" or formal their intentions were in that regard is beside the point, and i'd guess not that contrived either. btw, it's always really annoying to me when people get snooty and try to dunk on genres like post-punk and such, saying stuff like "how can it be post-punk when a lot of it was coming out at the same time as regular punk music," and "post-punk is such a meaningless term because so many of the bands don't even sound anything like each other. like Joy Division and The B-52's and Devo don't sound anything alike, so why are they all post-punk? back in my day we just called it 'new wave' anyways!" "post-" doesn't just signify that it comes after chronologically; that's not it's use in relation to art: it connotes a different approach using the conventions of a genre, to provide as surface level a description as possible. for ex: postmodern literature takes the ideas of modernist art and stretches them to their absolute limit; post-punk keeps the punk energy and ethos and applies that energy in a different, more creative direction; hell, even Borp's combo video Postmodern Smash (which has sadly been privated on youtube) showcases his unique playstyle that emphasizes fundamentals and rejects Melee players' obsession with tech skill—obviously not "chronologically following" modern smash, as he was playing alongside people who honed their tech skill and ultimately greatly surpassed him—it was just his novel approach. anyways yeah, Tortoise grew steadily jazzier over the years and helped shape nu jazz in a huge way. "Glass Museum" off Millions Now Living... is a personal favorite for that, the vibraphone and spacious chords and bass vi solo a clear precursor to the moods and structure that bands would draw from heavily in the future. and especially on TNT, with the addition of Jeff Parker on guitar, they let their jazz chops shine through. Jaga Jazzist is probably my favorite band that falls under this umbrella. they're a norwegian septet or octet or nonet or something wild like that, and they make super proggy and intricate jazz that's an absolute blast to sift through. The Cinematic Orchestra is another really cool one. their album Man with a Movie Camera is meant to be a soundtrack for the 1929 soviet silent film of the same name, and it works remarkably well for that. super cool piece of work. the bass clarinet solo on "Drunken Tune" (along with the bass clarinet part from Jaga Jazzist's "Airborne" off A Living Room Hush and Beefheart's noisy noodlings on Trout Mask) really made me want to pick up the instrument. Portico Quartet are another really cool example, especially with how minimal and textural they are. Mammal Hands are closer to the pure jazz group side of things, but i'd say they still count. maybe you could throw the Esbjörn Svensson Trio in for how minimal and spacey they are, too. honestly, just check out Ninja Tune and sift through some of the bands on their roster. probably the best list of artists representative of the genre.

#i mean yeah obviously i don't talk like this#and some conscious thought went into this when i was writing it#but it was the general vibe of the dream for sure

0 notes

Photo

Today’s compilation:

The Soul of Klezmer: Fantasy and Passion 1998 Klezmer / Folk / World Music

Never in my life have I ever deliberately gone out of my way to listen to klezmer music before, but all of that changed yesterday when I decided to give this 1998 double-disc from German world music label Network Medien a spin. Plus, it's Passover! So, a hearty chag Pesach kasher vesame'ach! / A koshern un freilichen Pesach to those who partake!

Now, this might sound a bit silly since klezmer is a traditional type of central and eastern European Jewish-rooted folk music, but I guess that, because most of the songs on this album appear to have been originally released in the 90s, I thought that they would've sounded more modern? I mean, like I said, I've never endeavored into listening to this music before, and have only been vaguely aware of what it sounds like, but along with the songs on here that were made in the 90s are also songs that are much older, dating all the way back to the 1920s. And beside the obvious difference in overall sound quality, there's not much of a discrepancy between how those much older songs and these more contemporary ones sound. The only band on here that appears to have incorporated a stroke of modernity are The Klezmatics.

So, just like how I have lots of respect and appreciation for old-time, pre-war jazz tunes, but don't enjoy listening to much of them, I feel the same way about these klezmer songs. But that's really not to knock the music at all. There is clearly a level of skill and dexterity needed to make klezmer well. "Purim," by The Andy Statman Quartet, has some really impressive folk guitar work on it, and Kroke's "Rumenisher Tants" contains some dazzling fiddle-playing, for example.

But I think I was also kind of deceived by this album cover too, which seems to depict a celebratory Jewish wedding. I guess I was expecting a bunch of foot-stomping and hand-clapping big band vibes, but a lot of these songs don't seem to be very upbeat or made by large ensembles either 🤷♂️. So, it looks like some of my preconceived notions about klezmer have been shattered here, which is good!

I'm also aware that there are some klezmer fusion genres out there too, like klezmer-punk and klezmer-jazz, and I thought that maybe, with a band name like New Orleans Klezmer All Stars, that might be a group that melds klezmer and a brass band sound together, but unfortunately, they don't 😔. But maybe there's a band out there that actually does that? Definitely still intrigued to hear some of that fusion stuff, or just klezmer that sounds more modern, in general. If you know of anything, feel free to holler.

No highlights.

#klezmer#folk#folk music#traditonal#traditional music#world music#jewish#jewish music#yiddish#yiddish music#music#90s#90s music#90's#90's music

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blocked to comment this on Anthony Fantano’s video (so I posted it here).

youtube

youtube

I couldn’t comment a response to this video on YouTube due to censorship so I decided to do it here:

The problem with Paul Joseph Watson is mostly the rational that is used to justify the 'breakdown' of morality through art and culture. The viewpoint that popular culture, within the twenty-first century,' is more "vulgar," "vapid," "self absorbed," "hedonistic," and "dehumanizing" "than any other time in living memory" is a view that is extremely one sided and biased. Any generation of the past could have made this argument about the popular cultural of their day and how it is "farther apart" from the traditional, fundamental values that define a culture or society.

If Watson is going to use the example of Miley Cyrus twerking in front of Robin Thicke as a reason this is no different than the view that parents, or most adults, had during the sixties about rock n' roll. For example, when the Beatles broke up my grandparents (on my fathers side) disparaged the groups period as a band commenting that 'The Mills Brothers' (a barbershop quartet that had a career run of fifty-four years and scored hits with 'You Always Hurt the One You Love,' Paper Doll,' 'Glow Worm,' and 'Up a Lazy River' in the forties and fifties that branded them "The Beatles of the 1940's") had a longer run and that the music, aside from Earl Hines, Marva Josie, and Dinah Washington etc. (musicians who need no introduction), had more 'quality' than the entirety of rock n' roll due to the immoral substance that my grandparents (on my fathers side) believed existed. Although this is not meant to disparage this generational period, as they were not always wrong on what popular culture contained whether it was moral or immoral, it highlights the gap between an older and younger group of people who, in some cases, failed to keep an open mind on what was new and presently modern.

If I was going to provide an example that related to the "classical traditionalism" that is 'mostly' found within Watson's channel, I would counteract this with examples of artists (composers, painters, sculptors, etc.), such as Frédéric Chopin, Alexander Scriabin, Arnold Schoenberg, Alban Berg, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Steve Reich, Philip Glass, Vincent Van Gogh, Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, Andy Warhol, Franz Kline, Barnett Newman, Francis Bacon, Damien Hirst, or Samuel Beckett. Although these names would invoke a more increased sense of realism to counteract against Watson's belief it would STILL, no matter how logical or understanding, would not be enough to disprove the argument that most, or all, of modern culture is immoral and responsible for the breakdown of "beauty" and "truth" (although these terms are subjective to how they are used within the given context to what people believe is beautiful and true).

Although there are a fair number of examples that have proved how modern society has provided the shift for the decrease of morality, this is still not comprable enough to assert the belief that modern society is the reduction of "everything that is 'moral' or 'positive' " (given the context of a certain subject or topic). If Watson had existed in the different eras of the artists listed above, he would have most likely disparaged what was not explicitly beautiful (hence, if he had existed in the era of Chopin, or Scriabin, he would have denigrated the use of dissonance found within a fair amount of their oeuvre as composers) believing that although these more modern artists are not entirely negative they STILL take away from the reality of "what beauty is."

Although I am four years late (regrettably), and I do not happen to agree with everything Fantano is expressing, he includes some important and relevant points, saying that although the classic, artistic styles of portraits are still relevant, it is essential to have variety and new ideas so these artistic, subject areas do not become static (3:00 - 3:08). With new ideas this allows for newer perspectives on how these traditional concepts can be considered, or 'digested,' from a newer perspective. Fantano also reminds us of the point that not everything in the modern era, especially television, is awash of programs that are unproductive, crude or narcissistic. For anything that can be defined, or misconstrued, as negative, or unproductive, it can be followed up with television programs, art, music, literature, or online articles that are supported with the intent of positively informing or entertaining their readers, listeners, or audience members.

Due to this, it disproves the view that modernism has produced the "diminishment of beauty" to such a high degree that it is a rare, almost nonexistent characteristic within our society. Although I believe that beauty has been subject to various levels of diminishment throughout the different eras of modern history, it STILL is an aspect of life that many people are fighting, protecting, and exemplifying through their work with some examples that include modern artists who are still living or working within the twenty-first century (with videos to prove my point):

Anthony Braxton (American "free jazz" saxophonist, composer, bandleader, and improvisor)

youtube

Barry Harris (jazz pianist, composer, bandleader, and teacher)

youtube

(although he is more of traditional modernist, espousing those who came after bebop such as Bill Evans)

youtube

Cormac McCarthy (author, novelist, poet, and playwright)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_s-egB5SzFY

David Dubal (classical pianist, writer, and disc jockey)

youtube

David Hockney (painter)

Frederick Buechner (writer, novelist, poet, autobiographer, essayist, preacher, and theologian) (this will only maintain relevance if you are religious)

youtube

George Winston (pianist, organist, guitarist, composer, and improvisor)

youtube

Keith Jarrett (jazz and classical pianist, composer, bandleader, improvisor, and multi-instrumentalist)

youtube

(with five other video examples as well that will be posted in the reblog of this response)

Even if these examples provide a strong, moderate, or weak validation for my argument they prove my point (I hope) that beauty is STILL a valued characteristic of daily life and defined as essential for the overall growth, of not only those who are subject to the work, but of the society and environment in which they live. Although the examples above are mostly based around music (due to this being a music channel), I have tried to include other aspects of the arts as well to prove that the modern world, whether it is centered around the second half of the twentieth century or the majority of the twenty first century, is capable of deriving beauty from non-traditionalism and that traditionalism is the foundation that supports the ideas that are acted upon in a modern context. Understanding this, it is safe to assume that not everything has to be 'traditional' or 'conservative' to be considered legitimate. Instead, it is more proficient to believe that as long as the various mediums within the arts, or other aspects of our societal culture, exude a pronounced sense of positivity, this will create a more likely heightened sense of awareness for what is considered 'valuable,' or 'essential' for a given society.

In summary, if Miley Cyrus and Marilyn Manson have profited off an existence that is viewed by a majority as being immoral this does not define the entirety of the modern world. Overt sexualization, the diminishment of beauty, and the "pretentious works of art" found at TATE Modern (using Marcel Duchamp's readymade sculpture, 'Fountain' (1917) as an example) is not the "top defining example" of modernism. Instead, they represent examples of variance that Fantano views as "shit posting before shit posting," even though I disagree with this viewing it as the development of a new artistic style and philosophy (what was known during Duchamp's life as 'DADA'). These newer styles separate art from aspects that are "static," "boring," or "plain" (depending on how these works are viewed) with Fantano using Lou Reed's 'Metal Music' as a relevant example for musical, modern ideas.

The "take down" (depending on how you define this in the context of how it is used) of traditional, conservative values do not define the majority of what is observed throughout the lens of modernism. Instead, it is artists, writers, composers, etc. taking risks on how they can combine traditional aspect of their medium, or style, and subject them to new ideas that are experimental, or improvisational, in their nature. even if an artist’s ideas had no connection to any aspect of traditionalism would this make it bad? In my opinion, not really.

Even if Watson makes a fair number of points that, hypothetically, could be agreed upon (with most that I do not agree with) this does not account for how flawed this view is. It is not healthy, or viable, for someone to look at the modern world with blinders on and continue to move forward. This does not assert change. This does not introduce newer ideas. This does not move traditional aspect of art, or culture, past their classical, conservative stages of infancy. If you want to move forward in the truest sense of a philosophy (give or take what that may consist of) you have to be open to incorporating newer ideas, even if it exists outside of your own personal worldview. You do not have to agree with it but to close yourself off entirely from a new experience that could benefit you personally is wrong.

The logic of "I disagree with certain characteristics of this so I am going to reject it entirely" is WRONG and should NOT be exemplified by anyone at any time. If you happen to disagree entirely with something that is your prerogative and should be respected (as long as it logically based off of facts that can be proven and sourced). Regardless of how right or wrong Watson is (although it may be apparent which view people have taken), it does not set aside the hatred that is transparent when choosing to believe in this philosophy. There are certain facts that define life and although it may be obvious that general "players" within the current culture are immoral and act in contrary ways, (opposed to the moral and values that once, in greater ways, defined our culture), this does not mean that those aspects of modernism that you personally disagree with, aside from what can be factually proven, are wrong, nor are they "the problem" (as Watson would say).

Yes, society has become more contradictory.

Yes, society has become more immoral.

Yes, society has become less centered around a factual or moral truth.

That is just the reality. But is it appropriate to hate what does not measure up with "moral" examples of the past? No.

Of course Mark Rothko is going to be different from Michael Angelo or Jackson Pollock from Claude Monet. That is just the way it is.

But to throw away what you cannot see personal value with may be realistic, and understandable, but in the end is ignorant.

So overall, anything that can be viewed as negative in the modern era can ALWAYS be paired alongside that which is positive. This has been true for the sixteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries, while still remaining currently true.

If Watson has to be given examples of positive aspects of modernism within the arts and culture, I suggest that he do more research. But then again, he is probably incapable of finding real, hard data, or credible sources, when he only exists on a surface level (and I know this from personal experience, I used to be a subscriber)

P.S.

And NO, I would not say that this is a realistic portrayal of conservatism because what exists on the surface is usually not a summary for the entirety of people who exist within a political or social group/philosophy. Regardless, Fantano makes a great logical point while still remaining relevant while providing examples are spot on in making his point. Overall, this is a good video that deflates most of what Watson is saying as flawed and illogical while disproving him in a factual way.

Rating: B+

NOTE:

I may edit this comment so expect changes. If I do not than it is here to stay. I hope that you have enjoyed what I have written and find it to be a good contribution to Fantano's response.

#essay#commentary#youtube#paul joseph watson#anthony fantano#video#writing#modernism#culture#society#politics#barry harris#jazz#modern jazz#anthony braxton#composer#composing#nea jazz#improvisor#pianist#piano#keith jarrett#david dubal#classical music#george winston#instrumental music#theneedledrop

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Things We Like”: Jack Bruce’s Seldom-Acknowledged Classic?

I originally bought this album around 1973, (and stupidly sold it some years later, for some long - forgotten reason), when I was exploring anything that featured John McLaughlin, then in his pomp with The Mahavishnu Orchestra. Things We Like was an early McLaughlin-related classic, recorded about the same time as his very first solo album Extrapolation, and shortly before Miles Davis paid for him to cross the Atlantic (the ocean, not the record label) to record on In a Silent Way, Bitches Brew and Live/Evil. He also found time to make Devotion, Where Fortune Smiles and My Goals Beyond, as well as co-forming Lifetime (who were never recorded satisfactorily, either in the studio or in the live arena).. The 1968-72 period was thus characterised by this impressive release schedule and the development of his mature guitar style.

Things We Like was actually Jack Bruce’s first solo album, recorded in August 1968, although the song-based Songs for a Tailor was released first. All instrumental, it was clearly a jazz album, and a very good one at that, with Bruce returning to his pre-Cream roots, and it deserves to be included in any list of late-sixties UK modern jazz/rock must-have recordings, alongside the likes of Nucleus and The Keith Tippett Group, and, by extension, the likes of Soft Machine Three and early King Crimson (the first four). He was accompanied by some old muckers from the 60′s British jazz scene: drummer Jon Hiseman was a recent member of Howard Riley’s influential trio, who had recorded their debut, Discussions, in December 1967, which set a high bar for such configurations on these shores. (Hiseman went on in 1968 to form Colosseum, with Dick Heckstall-Smith, the final member of this quartet, both having played with Graham Bond in his Organisation, and as members of John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers on the Bare Wires album.)

Things We Like fits in perfectly with its contemporaries, giving early notice of McLaughlin’s talents (especially on ‘Sam Enchanted Dick’and ‘HCKHH Blues’), before Mahavishnu rather muddied the creative waters; confirmation of those of Heckstall-Smith and Hiseman; and a re-affirmation of Bruce’s jazz chops on the double bass, with six tricksy-yet-emotive originals, communicated through a dry, no-frills sound. Unfortunately it tanked commercially - the album only surfaced in 1970, and former Cream fans were perhaps somewhat baffled, and jazz fans possibly doubted the ‘authenticity’ of a recent rock star’s attempts to ‘go solo’ (although Songs For a Tailor proved both a commercial and critical success). Listened to over 50 years later, it slips loose of all these contemporary contexts, and stands out as yet another great British jazz album from what is now generally viewed as somewhat of a ‘golden age’ for the music. There are many, many more albums from the approximate period of 1968 -72 that could bear re-examination, re-discovery (or just mere discovery?) and subsequent re-release. John Surman and the late Kenny Wheeler, to name just two examples among so many others, may be in danger of being forgotten and/or marginalised. A thorough reappraisal of this period, both discographical and bibliographical, is long overdue, although John Wickes’ long out of print ‘Innovations in Jazz’ is well worth seeking out.

1 note

·

View note

Text

In conversation with Keith Emerson ...

Keith Emerson (02.11.44 – 11.03.16)

The Father of progressive rock; the man responsible for the introduction of the Moog synthesiser to the ears of the unsuspecting music lover in the 1960’s; and without a doubt one of the 20th and 21st Centuries (to date) most prolific and talented composers of modern classical music. In a career spanning 6 decades, which has earned him notability as a pianist and keyboard player, a composer, performer, and conductor of his own music alongside the World’s finest orchestras; as well as achieving super success with “Emerson, Lake, and Palmer” - 2014 has been no less eventful for Keith Emerson! With his 70th Birthday approaching, Helen Robinson caught up with him for a very ‘up-beat’ chat about (amongst other things) the re-releases of his solo records, a brand new album with Greg Lake “Live at Manticore Hall”, his favourite solo works, and his memories of the times spent writing and recording with ‘The Nice’, and ‘ELP’.

HR : This has been a busy year for you so far Keith! KE : Yes! I’ve been up to allsorts! [laughs]

Music wise – what can I tell you? Cherry Red , Esoteric, have re-mastered and re-released 3 of my solo albums – “Changing States”, another which I recorded in the Bahamas called “Honky”, and a compilation of my film scores which consisted of "Nighthawks”, “Best Revenge”, "Inferno”, “La Chiesa (The Church)”, "Murderock”, "Harmagedon” and "Godzilla Final Wars”.

HR : That must have been a difficult selection to make based on the number of scores you’ve written! Do you have a particular favourite genre of film to write a score for?

KE : Favourite genre? Boy, well, I just love film score composition, you know? When I first started I had been touring with ELP for some years, and we’d toured with a full 80 piece orchestra but it was just too expensive – we had to drop the orchestra and continue as a trio, which was very upsetting for me. I was entranced by what an orchestra could actually do, and found that with doing film music I could work under a commission and have the orchestra paid for by the film company!

It’s always a challenge. I think a lot of composers like to write dramatic music. I like writing romantic music as well – I’ve also written for science fiction where you can let your musical imagination go pretty much where you want, but generally you have to cater specifically to the film. First of all I like to get a good idea of who the producer and director is, and who is likely to be cast as playing the lead roles. I like to read the script – which helps prior to meeting up with the director and producer. When I wrote the music to Night Hawks I was sent, by Universal films, news of a new film to be made by Sylvester Stallone, a new guy at the time called Rutger Hauer, and Billy Dee Williams, also Lindsay Wagner. It was basically a terrorist film – not the terrorism that we shockingly see today – but back then it was the beginning of terrorism and was quite mild by today’s standards, however it was still sort of ground breaking as far as writing the score was concerned.

It’s about vision with film score work.

Although really it’s all about vision with anything you’re writing, and I suppose many of the disagreements that ELP had during their time – of course a lot of it came to wonderful fruition – were not seeing eye to eye because we had such different tastes in music. Ubiquitous I would say – we bounded from one thing to another. Just when you thought it was getting serious we’d want to have some fun and do something light hearted but I’ve always maintained that variation is essential.

I think that’s what helped ELP quite a lot – especially live - in any particular set you had the heavy stuff like “Tarkus” and “Pictures At an Exhibition”, for the guys in the audience, and for the females who attended reluctantly - dragged along by their boyfriend or husbands and just sit there - I mean, I didn’t sit, I was standing and leaping around [laughs] but you couldn’t help notice the glum looking females in the audience wondering when all this was going to be over.

I think when ELP were together as a unit, we managed to meet everybody’s needs. Greg came up with some really great ballads which sort of got home to the feminine heart, like “From The Beginning” – the feminine heart goes “aaah aint that nice” [laughs] and then suddenly you get the bombardment of something like “Karn Evil 9” and it’s like “Oh GOD”!!

HR : I’d like to talk more about ELP, of course, however there’s so much more outside of that unit , which you have been involved with, that has had quite an influence on modern music. You’ve got an extraordinary and fairly extensive discography, which we can pick whatever you’d like to talk about, but I’d like to start with ‘The Nice’ - “Ars Longa Vita Brevis” ...

KE : Ah Yes ‘’Art is long, life is short” - Lee Jackson came up with that title - he’d studied a bit of Latin ... [laughs]

Going back to the 1960’s then – I suppose it was ‘66 when ‘The Nice’ formed – originally as a quartet. Drums, bass, Hammond organ or keyboards, and guitar player. After the first album we decided to move on as a trio, although I did try to find another guitar player. I actually auditioned a guy called Steve Howe, who was considering getting together with Jon Anderson, and Chris Squire and forming a band called “Yes”. Steve was much more interested in getting with the “Yes” guys, so meanwhile ‘The Nice’ continued as a trio with Lee Jackson on bass, Brian Davison on Drums, and myself on Hammond and keys. It was during this time that I was introduced to a new invention designed by Dr Robert Moog, which became the moog synthesiser, so I was the first to introduce that into live performance.

With ‘The Nice’ we had come out of an era called the underground / Psychedelia.

I was very friendly with Frank Zappa and the mothers of invention, and they were really far ahead of their time.

Frank approached me one day, because I was composing and playing with the London orchestras even then, and said ‘’Keith - how do you deal with English orchestras? They’re hopeless!”

And I said ‘’Well, they’re very conservative Frank. If you really want to make it with the London Symphony, or the London Philharmonic - if you really want my advice, I think you should try and change some of the lyrics of your songs. If you’re going to get in front of the London Philharmonic and sing stuff like ‘’Why does it hurt when I pee?’’ obviously these guys are not going to take very kindly to it!” [laughs]

I’d actually done Bachs Brandenburg concerto #3 with a chamber orchestra and had a degree of success in the English charts- around about the same time , Jon Lord [Deep Purple, Whitesnake] was writing his concerto for orchestra too. I’d already written the “5 bridges suite” which I had recorded with ‘The Nice’ at Fairfield hall in London. So basically Jon Lord and I were kind of both struggling with Orchestras and moving along into what came next musically for the both of us – Jon was a very good friend.

I think round about the turn of 1970, I had noticed what Steve Howe was doing and it was very harmonic, whereas ‘The Nice’ - well we were a bit more bizarre, and I listen back to it now and I suppose I have a slight bit of embarrassment about how ‘The Nice’ were presenting themselves.

And back then I’d started looking at bands like ‘Yes’, and there were a lot of other bands too, who were really concentrating on the tunes and the vocal element, so that’s when and why I formed ‘Emerson Lake and Palmer’ - in 1970 - and endorsed the whole sound with the moog synthesiser. It sort of took off, and became known as what we know today as “Prog Rock”. We didn’t have a name for it at that time, we just thought it was contemporary rock. I mean it wasn’t the blues, it wasn’t jazz, but it was a mixture of all of these things, and that’s when we went through.

The first album of ELP, [Emerson, Lake, & Palmer] recorded in 1970; we were still learning how to write together as a unit, so consequently when you listen to it, you’ll hear a lot of instrumentals; mainly because there were no lyrics and there was a pressure on the band to get an album out. For some reason there was an extreme interest in the band - We were to be considered as the next super group after ‘Crosby Stills & Nash’, which we certainly didn’t like the idea of. That album went very well. Unfortunately the record company decided to release “Lucky Man” - which was a last minute thought – as a single, and it took off. My concern was the fact that, OK yeah the ending has the big moog sweeps and everything like that going on – but how on earth do we do all the vocals live? Thousands of vocal overdubs over the top and neither Carl nor I sang. You know - I sing so bad that a lot of people refuse to even read my lips! And as far as Carl Palmer was concerned he had “Athletes Voice” and people just ran away when he sang! It was a hopeless task of actually being able to recreate “Lucky Man” on stage, so eventually Greg just did it as an acoustic guitar solo. It was that one sort of Oasis, in a storm of very macho guy stuff, where the women just went [in a girly voice] “Oh I like that, that’s nice”. [laughs]

So, inspired by that we got more grandiose and put out ‘’Pictures At An Exhibition” – another bombastic piece based upon Mussorgsky’s epic work. For some reason Greg wanted it released at a reduced price because he said it wasn’t the right direction for ELP to go. So we released it for about £1 and it went straight to number 1! Then the record company called up and said ‘’what are you doing? This is a hit record and you’re just selling it for £1??!!’’, so I said ‘’well yeah it’s a bit stupid isn’t it?” – so when it was released in America it was at its full price and ended up nominated for a Grammy award! ELP had a lot to do to create the piece you know? We disagreed on lots of issues but in order to keep the ball rolling we just moved on with the next one, which was in fact “Trilogy”.

I thought it was about this time in ELPs life that we had learned how to tolerate each other, how to write together, and how to be very constructive. “Trilogy” is a complete mish-mash, you go from one thing to another; there’s a Bolero, and then ‘Sherriff’ – which is kind of western bar jangly piano playing on it. I don’t think you could find such a complete diversity buying a record like that these days. We were very much inspired by our audience accepting that.

Actually Sony Records are going to re release it in 5.1 – they’re doing a wonderful package with out-takes and everything – I’ve just competed doing the liner notes.

We moved on again then, and started the makings of “Brain Salad Surgery” which was a step further.

After that I worked on my piano concerto played by the London Philharmonic Orchestra, and actually it’s still being performed all over the world - Australia, Poland, and in October I’m going to East Coast America to do some conducting – Jeffrey Beagle, who’s a great classical pianist, is going to perform it then, and I’m going to perform some other new works of mine.

HR : Are you likely to release a recording of it?

KE : Yes I guess it might be ... I’ll let you know. It’s a dauntless compelling challenge. I have conducted and played with orchestras before and I’m very thankful to have classical guys around me who are able to point me in the right direction. I was never classically trained. I started off playing by ear and then having private piano lessons, and then basically teaching myself how to orchestrate. I’m still taking lessons in conducting and I don’t think I’ll ever get to the standard of the greats like Dudamel or Bernstein – I don’t think I’ll ever be able to conduct Wagner, but so long as I’ve written the piece of music I think I’ve got an idea of roughly how it goes! [laughs] Thankfully I’ve worked with Orchestras who are very kind to me.

HR : Do you enjoy the performance as much as the writing?

KE : Actually I enjoy the writing more than the performance. I know I wrote an Autobiography called ‘’Pictures Of An Exhibitionist” but that’s the last thing that I am really. I’m pretty much a recluse. I’ve got my Norton 850 and I’m happy ...

HR : I was going to ask you about the Theatrics on stage – Why Knives and swords? Was there something which influenced the decision to include that as a part of your performance, or was it purely born out of frustration from working with Carl and Greg?

KE : [laughs] Well you see in the 60s, I toured with bands like The Who, and I watched Pete Townshend; I toured with Jimi Hendrix too, and I thought that if the piano is going to take off then the best thing to do is like really learn to become a great piano or and keyboard player, but I also thought “that aint gonna last with a Rock audience in a Rock situation”, mainly because the piano or Hammond organ - well from the audience you look up on stage and it’s just a piece of furniture! Whereas the guitar player can come on stage and he’s got this thing strapped around his neck, he can wander up and down the sage, check out the chicks, and he’s the guy that has all the fun. The organ player meanwhile is just seated there at a piece of furniture like he’s sat at a table. So a lot of what I did was for the excitement of it, and I suppose to exemplify the fact that I could play it back to front. A lot of my comic heroes like Victor Borg, Dudley Moore – they all came into the whole issue too.

I’ll tell you this ok? I once went to see a band at the Marquee club when it was in Wardour Street in London, and I can’t remember this guys name now, but he played Hammond organ - he was a very narky looking fellow, and went on stage wearing a schoolboys outfit which caused a lot of the girls in the audience to chuckle. I stood at the back of the Marquee club and watched his performance - a lot of the stops and things were falling off his organ, so he had a screwdriver to keep holding certain keys down, and then suddenly the back of his Hammond fell off – and I don’t think it was intentional, because he looked really quite distraught, but he caused so much laughter from the audience. I went away thinking “there is something there, I’m going to use that” ... I actually thought it would be a great idea to stick a knife into the organ, rather than a screw driver -the reason for this was to hold down a 4th and a 5th , or maybe any 5th, or say a ‘C’ and an ‘F’ or a ‘G’, whatever, and then be able to go off stage, take the power off the Hammond, so that it would just die away - it would go ‘’whoooaaaaaaaoooooh’’; and then I’d plug it back in and it would power back up and create like the noise of an air-raid siren, and of course the drummer and bass player would react to that. It got really interesting. We actually had a road manager at the time by the name of ‘’Lemmy’’ who went on to be with Motorhead. He gave me 2 Hitler Youth Daggers and said [best Lemmy impression] “here! If you’re going to use a knife, use a real one!”

So that was the start of all that, and people loved it, and actually Hendrix loved it too – somewhere in his archive collection there must be some footage of me almost throwing a knife at him [laughs] .

The phase for it was my objection to the 3 assassinations they had in the USA - JFK, Robert Kennedy, Martin Luther King - I’d been to America once and seen how quick the Police were to pull out their guns to a woman parking her car illegally – so bizarre. The 2nd amendment will not go away, as much as they want it to. I’ll reserve further comments on that but that was really the whole objective. I was banned from the Albert Hall for burning a painting of the Stars and Stripes, which took some time to get over, but everything worked and they allowed me live in California now. [laughs]

HR : What about the Manticore Hall show, also released this year, presumably you kept burning paintings off the agenda there? Was it good to work with Greg again? and then the complete ELP line up with Carl at High Voltage?

KE : No! [laughs], and Yes ... Actually that was recorded in 2010 and was an idea set up by a manager associate of mine, and an agent in California. I met up with them and they asked how I felt about doing a Duo tour to lead up to the High Voltage Festival in London. They convinced me that it was a big festival ... and the idea was to have ELP on the Sunday night there. So the lead up was a duo tour with myself and Greg because Carl was off with Asia at the time. It had its ups and downs, but it did eventually work very well and it was a very good warm up to doing that Festival date as the 3 of us. I don’t think there was any intention of us going any further with it. I think the resulting “ELP at High Voltage” was good and also I think the album ‘’Live At Manticore Hall’’ - although it wasn’t released until this year, because Greg initially didn’t want it to be released at all - is good stuff too. These things happen with bands, it takes a while for us to appreciate how good what we do is, sometimes.