#another example of the tragic self (and tragic relationship) ultimately being more important than morals

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

am i rlly going to write a death note literary analysis when i could be doing other things

about the discourse going on in the tag abt "death note is acab and thats why the characters couldnt better the world with the note (/written in somewhat jokey matter)" vs "death note is trying to say we all have potential for evil, especially if you get a chance to insta-hurt ppl without repercussions, and it doesnt matter if youre a cop or not", i personally feel like it ignores the things that i like abt death note, which is "both of these things are true", and simultaneously "both of these things do not matter". the first part of this is dedicated to the first point, the latter to the last.

first point. i think its an important part of the message and themes (unintentional or not, and i lean on the former because... come on, can you really say the author intended you to not think of the cops as good people, at least compared to light and l) that light is a cops son, and that almost everyone who gets the death note is cop adjacent/thinks like a cop and is already corrupt/powerful when they get it (mello raised to think hed be just like l, yotsuba group is self explanatory; you cannot look me in the eyes and tell me teru "churchill" mikami, who was hand selected by light out of a bunch of rabid kira supporters, is a normal citizen). i appreciated the cop post bc its rlly important to not gloss over that aspect.

all of this would be an argument for "only someone like them would do something like this, and i am not like them, so im above them and immune to thinking about what id do with it", but... misa is the MOST important outlier in all of this bc her murders are solely selfish in nature and shes not doing any of this for "the greater good"!!! her nature of being an exception and still a very very bad person is really really important...

or it would be if death note gave a shit about her character at all!!! im not talking about her tragic side, im talking about exploring the ramifications of her killing people the way lights murders are (somewhat) explored. that would strengthen the message greatly! but shes dismissed and that weakens it overall. firstly, she's dismissed by the characters when l only sees her as a way to get to kira and basically shelves her the rest of the time. secondly, shes dismissed by the narrative when her character is gradually ground down to a stump and (not to sound perilously close to the bad takes ppl meme about) she never faces repercussions for her actions. every other character using the death note is treated relatively seriously, but misa just dies bc her love is dead. im not saying this isnt a... fitting punishment or that it isnt in character, but it doesnt fit snugly into the theme other people are talking about of "you reap what you sow" at all.

we do have something of an equivalent to misa's grayscale motives. surprise surprise, its light yagami. first is light's characterization in the musical (i will also note that misa never kills anyone in the musical). light's thinking is coplike, yes — he literally starts his first song by talking about "throw[ing] away the key" — but also, oddly enough, could be read as progressive and therefore sympathetic to tumblr ("let the corporations make the regulations / and hold no one accountable when everything gets wrong / let the rich and famous get away with murder / every time a high-priced mouthpiece starts to talk, his client gets to walk"). compare to the anime and manga, where his bigotry and pride and disgust come from a place of lukewarm dissatisfaction and boredom. the musical has much less time to play around with lights character, so it gives the audience something to immediately hook on. more on how that actually plays out later.

in the animanga, none of this is justified from the start. animanga light could say he was just killing people to make humanity way, way worse, and that wouldnt matter, because at the root of it, it was always his boredom that made him pick up the note. of course he actually believes in justice and believes hes doing the right thing (no, he believes he's doing the wrong thing, for the sake of the world... the right thing, because he is god...), but it was boredom at the start. all animanga light says about justice and righteousness and the law is a front in the end, bc he is exactly like l and misa — amoral. selfish. searching for entertainment. hedonistic. we know this. he kills naomi misora*. he kills lind l. turner. everything hes saying deserves to be dismissed from the beginning.

"but doesnt that mean you agree with the discourse post you wrote this post to argue against?" like i said, i agree with both of them! but i... still think its not right to reduce death note to the message of "the power to kill people is bad". because that is not exactly what the story is saying, even though that's literally its whole plot and therefore reaching that conclusion is self explanatory (lmao). let's look at the concept of mu. nothingness. "there's no heaven or hell". The Real Slay The Princess (Death Note Essay) Starts Here.

in light's final moments in the death note manga, while screaming about not wanting to die, he remembers that the first day they met, ryuk told light that "there's no heaven or hell. no matter what they do in life, all people go to the same place. all humans are equal in death". it is retroactively revealed that light knew this the whole time, operated under this knowledge for all the years we watched him — the knowledge that nothing he does is actually bad, that nothing any human does is actually bad, that shinigami are not "evil", that the universe does not care. that no one cares except humans. this oblivion absolutely terrifies him more than anything anyone could ever do to him. its what he thinks of before anything else as he flails there, screaming, dying. one could say everything he does after that day is him trying to escape that fact, or wrest control over it. but it doesnt work.

here are the lyrics of requiem, the musical's final song, sung over the bodies of l and musical light, a light who was at least somewhat good-intentioned at first: "sleep now, here among your choices / then fade away / hear how the world rejoices / shades of gray / gone who was right or wrong / who was weak or strong / nothing left to learn". this is the final message the death note musical and the manga chose to leave us with. there is no judgement. even after all that acknowledged hurt, after all the damage done, there is no judgement.

in the manga and anime alike, the world is just as fucked when light picks up the death note as when he dies. sure, we as readers can guess otherwise logically (and be optimistic, believing the world was never fucked regardless), but that's not what death note wants you to think. it ends with matsuda and another member of the task force noting how the world is worse again even though they killed kira (matsuda is clearly much worse for wear, but still determined), we see the shitty motorcycle band again, it ends with misa and a whole kira cult on a mountain even though kira died a long time ago...

its extremely important that light is never killed by any human or any aspect of the law. he is always killed by ryuk: a chaotic force completely detached from human sensibilities, one that does not care about good and evil. same with l; in the anime, manga, and musical, he is always killed by rems senseless, morally gray love (and you could argue in the kdrama that hes killed by love there too lol). justice is just a set dressing.

this is not just because death note is a tragedy, because good and evil can still matter in a tragedy. the theme of "nothingness" and "good and evil doesnt matter here" is also shown in a situation relatively unrelated to light winning or losing, or being good or bad. and its in fucking lawlight of all things. we all know ls not a good person. we know lights not a good person. this is tip of the iceberg death note knowledge. but the moment they start to interact, none of that starts to matter. textually, their relationship becomes more important than the people theyve killed and hurt. and the thing is? the thing is? THAT WORKS STORY-WISE. THAT'S ENTERTAINING. AND IT'S NEVER TEXTUALLY CALLED OUT IN A LASTING WAY. l and lights relationship, no matter how much i meme it, is genuinely important to the themes and "mu" because it makes it clear that despite all the pretensions, despite everything, this was never about good and evil. and it still works in the story. this is why death note is simultaneously a comedy — isn't the battle of good and evil supposed to matter more? well, fine, i'll keep watching this anyway. that suspension of disbelief comes crashing down the moment l dies, though, and a relationship built on nothingness (the "mu" sort, meaninglessness, not "character development" nothingness, theres plenty of character development) gives way to just nothingness (again, "mu", not light's post-l depression nothingness), forever.

(an aside: there is no one to root for in death note, and the only things to root for are either interesting character relationships, convoluted plots, or complete and total destruction: for everything to end so no more damage is done.)

not to say that death note does not encourage its readers to consider what damage they might do with the death note (obviously.), or that its characters never do. look at matsuda, a much easier heroic figure to latch on to than soichiro because of his unique place in the cast dynamic and because he's willing to consider both sides of the situation and kill light instantly for all he's done. its just that the story's own stance on the subject is... complicated by the existence of shinigami worldviews and by its own insistence that the world cannot change for the better.

also, this is not to say that this is executed well by the death note manga at all. it is a very strong tool, artistically, to establish and then violently remove any emotional connections between characters and make your story only about the exceedingly convoluted lengths characters go to to survive and catch each other so the reader can realize how ultimately pointless all of this is, but like... is that a good story choice if that's all you do? i would say not really. add in a good dollop of misogyny that destroys the second-to-last character who might actually be an interesting contrast to the rest of the cast's dull one-track focus on winning and justice, and youve got yourself a shitty story that... honestly still achieves what it went out to do, just not in a way id ever want to replicate.

anyway, back to the parts death note's actually trying to say. no matter what any human does in their life, no matter how they try to hurt or help the world, they all die in the end. hey, light, they all die in the end. once dead, they can never come back to life. and the seasons turn. and the world rejoices. and you say "goodbye"...

that's all.

no analysis of death notes overarching theme would be complete without nears final monologue, the definitive roast of light, the "you're just a murderer" speech: "what is right from wrong? what is good from evil? nobody can truly distinguish between them. even if there is a god." if we take this as talking about the actual god in the room (ryuk) as well as light, then near admits that humans will never be able to withstand these overwhelming forces and that, using justice and happiness and selfishness, they are just scrabbling to find meaning in things they ultimately have no control over.

but of course, near does not stop there. "[...] even then i'd stop and think for myself. i'd decide for myself whether his teachings are right and wrong." nears alright with not having control over everything, because near can still control nears own actions. these forces can and do exist, but they have no sway over nears own humanity — unlike light, who caved.

one of the creators of death note said they believe its message is "life is short, so everyone should do their best". the first time i learned this, i was like, thats... nice and optimistic, but an awful reading of the story! "life is short, so everyone should be desperate and striving like light yagami", who literally cut off other ppls lives for his own life? what character in death note are we supposed to strive towards when we "do our best"? they all do awful things with their lives! honestly, maybe they shouldnt have tried their best, if this is what their best is!

but with the view of "mu"... it makes a bit more sense. just a little. maybe.

there is no good and evil. there is only what humans think, and no matter what we do, we all die in the end. it is easy to be crushed and terrified by this in the same way light is, but what is more important than justice and righteousness and finding meaning is... doing your best. not being a person that hurts others too much. not letting yourself get swallowed up by an ideal. not going too far. and simultaneously, trusting yourself.

it leaves a few questions, though... was the currently dead l even a little bit right about his blatantly amoral approach, then? was there a point to this pain, and me slogging through this dumbass manga, and all the people that have lost their lives to a selfish teenage cop's son and the whims of everyone chasing after him? was there a point to any of this...?

the manga** never answers this. it stays clinically impartial until the very end. the musical is anything but clinically impartial (and i love it so much for that), and its ryuk that has the last word.

"there's no point at all."

of course theres no point. none of this was ever supposed to happen. that is what matters more than all the hurt and the crimes and the pain.

and that's... actually okay, because it's over now.

yes, death note has many really important themes present in its story, but its viewpoint is nihilism first and foremost. thats why its so fun and easy to play around with all the other messages, because no matter what fun or torment or awful things or righteous justice or absolute nothingness or sentimentality happens in between, there is always an end.

there is always the end.

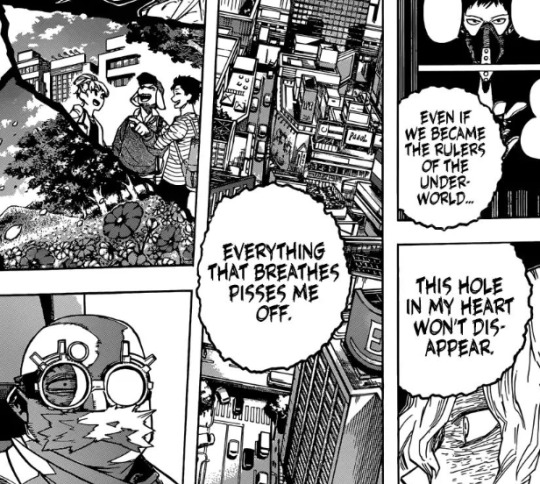

#*naomi was killed off bc the author thought shed solve the case too quickly. ironic. i dont think it was meant to forward a theme other than#'light evil! oh no!!!' bc it had minimal buildup and absolutely no repercussions. it is just kind of smth that happens#everything in death note is just smth that happens bc. at some point i just have to admit its NOT RLLY WELL WRITTEN#but it says something. it says many things. and i like balancing the two in my head#death note#personal#**>reduces anime ending to a footnote /j#anime ending: light regrets COMING THIS FAR- not his crimes. he sees l as another regret and dies.#another example of the tragic self (and tragic relationship) ultimately being more important than morals#l would be proud of the torment he inflicted on light if he were not fucking dead#i would also bring up the argument that the way every death note character uses the note is so extreme that its hard to compare them#to real people but lets assume that the author was trying to replicate how actual human beings work as much as possible*#you made it deep enough into the tags would you like to hear about near and mello being nonbinary—#'there is an end so why not enjoy the middle? chain yourself to a hot boy eat strawberry shortcake be bisexual and lie'#*either that or they were just explicitly trying to have fun like they said they was doing#light yagami#sure ill tag my boy#'you cant say the curtains are just blue!' well can i say the curtains were shittily made#norrie if you look at this post ever again ill death note you myself

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

kenlee: a 4 part analysis

Analyzing one of my favorite ships that I have very suddenly grown very hyperfixated on. Lee and Kenny are partners in crime, frenemies, a variety of things to each other based on what the player decides. Season 1 is notorious for none of your choices impacting anything because there’s only 1 ending no matter what. Yet, genuinely one of the only examples of your choices actually mattering is through Lee's relationship with Kenny. Their dynamic is given more attention and effort and detail than anything else in the game, even more than Lee and Clementines (as far as how it can differ based on how you play). There are also countless tender moments, looks, and words shared between the two that I’ve grown to interpret as more than friendly the more I’ve replayed the game. However, this analysis will break down more tangible moments throughout the game.

Part 1: What Lee and Kenny’s Dynamic is

Lee and Kenny are the classic but tragic “never got to tell them how I felt” trope. Due to many factors, their feelings for each other were something that they only had themselves to rely on and carry the burden of. This even resulted in tension in resentment towards one another. From the overwhelming apocalyptic state of the world, to Kenny having a wife and kid, to the both of them most likely not being comfortable exploring their sexuality– so many odds were stacked against them. Ultimately, they were in a predicament where they could’ve confronted their feelings for each other if they were given more time. But, the two men only knew each other for a handful of months before their separation.

While most of the obstacles that got in the two’s way were external, Lee and Kenny, Kenny in particular, also got in their own way very often. One of the main ongoing plot points within season 1 is that Kenny and Lilly both have a different way of leading and Lee is stuck in the middle. Along with this, Lee is generally put in a lot of difficult situations with Kenny, as Kenny sees him as his right hand man and takes it very personally whenever Lee disagrees with him on something. Now, what I’m about to say next is my own opinion and anyone reading is allowed to disagree but, I personally think that the version of Lee and Kenny’s relationship that’s the least accurate is the one where Lee agrees with every single one of Kenny’s actions and has Kenny as an immovable pillar of support. This is because I’ve always interpreted the most canon version of Lee to be the one who tries his best to take the moral high ground, which Kenny arguably doesn’t always do. So, as off-balanced and unhealthy as their relationship turns out when Lee sticks to these morals, I do think it’s important to what Kenny and Lee’s true and honest dynamic is— after all, they’re foils to one another.

Something that’s important to address is how much Kenny cares what Lee thinks— more specifically, what Lee thinks of Kenny. This is something that Kenny has shown time and time again to agonize over. As far as the first season goes, generally anyone could disagree with Kenny and he would feel more inclined to brush it off and carry on because he knew that, to him, he was right— except for when it comes to Lee. Whenever Lee expresses disagreement or disapproval in something that Kenny is doing, Kenny is beside himself. He rages at Lee, tries to convince him to see things his way, holds a grudge towards him, and overall gives the other man a very emotionally heated response. My belief is that Lee is someone Kenny admires and looks up to to a degree. Because of this, whenever him and Lee differ on something, it forces Kenny to self-reflect and reevaluate his own actions and values, which Kenny isn’t comfortable with doing. Furthermore, he’s also convinced himself that Lee thinks less of him as a person everytime the two don’t see eye to eye on something, which Kenny could not bear. To cope with all of this, he tries to bring himself to hate Lee instead.

So, how do Lee and his feelings play into this? The way I see it, Lee is the only person who sees the hurt behind Kenny’s actions, the good intention behind Kenny’s actions, and can understand the man even when he doesn’t agree with him— the only one besides Katjaa, of course, which isn’t for nothing. As someone who was on his way to jail for murder a day before meeting Kenny, he understands expressing anger through aggression, feeling betrayed by someone you love, making mistakes that can’t be undone, etc. better than anyone. And while he’s not proud of those things, he came out of the situation feeling as though he has no right to judge anybody, so he doesn’t dare judge Kenny. That being said, he hopes and tries to assist Kenny in working past his demons the way that Lee was able to. He sees the great traits within Kenny— his ability to lead, his passion for what he believes in, his diehard efforts to protect his family— and believes that those things are capable of defining him instead of the bad. (long story short he thinks he can fix him y’all sorry)

Part 2: How Their Interactions Mirror one of Two People in a Relationship

This next section is going to be dedicated to a variety of examples that showcase my point that Kenny and Lee’s relationship was written a lot more intimately and a lot less “bro” like than there’s any excuse for. These are all instances that fail to add up completely unless you switch the perspective from platonic to romantic.

What I believe to be the strongest example of this is when Lee finally faces the stranger in the season 1 finale. The stranger asks Lee, “Have you ever hurt somebody that you care about?” and it prompts three options for the player to choose from. The first option is his wife, and the second option is Clementine who is essentially a daughter to Lee. These options make complete sense, especially since this question is followed by the stranger sharing how he hurt and lost his children and wife. The third option, however, is Kenny. This option sticks out like a sore thumb to me because it just doesn’t really fit quite right as the placeholder “friend” option. If Kenny was Lee’s childhood friend, or even college friend, or any context where they had a long standing history with each other that started before the apocalypse, I don’t think I would’ve bat an eye to it. It’s like how if (I don’t watch the show so if this ends up making no sense forgive me) Rick gave Shane as an answer, I wouldn’t have questioned it. Lee and Kenny only knew each other for around 5 months, though. Additionally, the only things Lee did to “hurt” Kenny was by personally hurting his feelings whenever he had a differing opinion as him. The way that Lee speaks about the entire situation in hindsight just feels a lot deeper and much more nuanced than a friendship.

Additionally, when the crew are all stuck in the attic together, Lee is having a conversation with Christa and Omid where he reveals who he’d like to take care of Clementine if he didn’t make it. The options are either Christa and Omid themselves, Kenny, or to find a different family to take care of Clementine. Kenny’s always been my favorite character, so the first couple of times I played this game I chose him based solely on bias. As I got older, though, the option of Kenny once again felt out of place for me. Lee is capable of choosing between a healthy stable young adult couple with good heads on their shoulders who want to raise a kid anyway… or Kenny. It’s not an even comparison at all– unless Kenny was Lee’s partner, then asking Kenny to look after Clementine in his absence would make perfect sense.

This one has been pointed out various times by shippers, but I’m going to mention it anyway because I think The Walking Dead Game’s writers are brilliant and that very little of their dialogue can be brushed off as an ‘accident’ or ‘coincidence.’ Throughout the game, only three people refer to Kenny with the nickname ‘Ken’: Katjaa, Sarita, and Lee. Do I think TWDG writers added this with the purpose of hinting at Lee and Kenny having a romantic relationship? No. However, I do think this was done intentionally to emphasize the level of closeness between the two, and I find it interesting that they went about it by giving Lee a habit that only Kenny’s wife and Kenny’s girlfriend could share with him. In other words, it feels like these two characters were coded without the game even realizing what they were doing– not like I’m complaining.

Part 3: How They’re More to Each Other Than They Are to Their Canon Love Interests

I’ve given examples of when the story has treated Lee as though he’s equal to Katjaa and Sarita in Kenny’s eyes. However, there is also evidence of Lee being held closer to Kenny than Katjaa or Sarita– same goes for Lee, as there’s an argument to be made that he held Kenny in a deeper regard than he did Carley. I want to preface this by saying, I am not here to pit Kenny and Katjaa against each other and don’t think it’s necessary to advocate for this ship. I myself love Katjaa as a character, and I also know and believe that Kenny loved Katjaa deeply. Sarita is a different story, and I could go on my whole tangent about how she was only put in the story as a plot device to drive a wedge between Kenny and Clementine, but I won’t. I’m also a fan of Lee and Carley as a ship, and a big multishipper in general, so please do not misunderstand this as me invalidating any other pairing.

When Carley (who canonically was Lee’s hinted at or potential love interest) was shot in the face right in front of Lee, he was considerably okay. All of his energy was put into disciplining Lily, but as far as Carley’s death itself, he didn’t really give much of a reaction. He had watched so much death at the point that it seemed like he was starting to get somewhat desensitized to it. When Kenny “died”, however– because remember, he never actually saw it, but just the mere thought of Kenny dying had Lee torn up in a way we hadn’t seen throughout the entire game. He took a beat to kneel over, exclaimed and cursed to himself, and was incredibly somber from that point on. There are even dialogue options for him to get snappy at Omid and Christa about the matter right after, making it abundantly clear how sore he’s left from it.

Kenny, on the other hand, mentioned, reminisced about, or blatantly said that he missed Lee on multiple occasions. He had only really mentioned Katjaa once in season 2 (from what I can recall), and one could argue that it was out of respect for Sarita, which is fair. This brings me back to what I touched on earlier about Sarita, which is that I feel she’s a placeholder– for both the story and for Kenny. He seemed excited to be with someone again, to have someone to hold at night, and to have the void of loneliness filled more than he seemed connected to Sarita as a person (hence him saying “I won’t be left alone again” as Sarita was dying–felt like the reminder of his past trauma was what was hurting him in the moment if anything). He, in my opinion, genuinely had the most connection or a dynamic that feels the most like a relationship on paper with Lee than any other character in the game.

Part 4: What Made Their Parting so Tragic/Their ‘Confession’

Seeing the scene for yourselves is a lot easier and much more effective than me trying to explain how it went, so refresh your memory with the video linked below:

youtube

If I had to pinpoint a part of the game that felt like an admission of feelings between the two, I’d say it was the moment during their separation, which is painful enough in itself. The few words that were exchanged by them in that moment, as well as the context of Kenny sacrificing himself and Lee fighting to convince him not to, felt like they were conveying everything they were feeling but couldn’t bring themselves to say directly. Along with this, Kenny let go of his complex towards Lee in that moment. He finally stopped feeling threatened and belittled by Lee’s unwavering goodness and, in Carley’s words, took a page from his book. That’s the silver lining of this moment– Kenny finally made a decision that he wouldn’t live in regret about.

Lee, on the other hand, died thinking that Kenny was dead. My best friend pointed out how, in Lee’s final moments, he probably thought about how he’d get to see Kenny again, not knowing that Kenny was perfectly fine. That just about broke my heart. What’s even more heartbreaking, though, is what would’ve been going through Kenny’s mind if Lee had cut his arm off. He disappears with the possibility of Lee still being alive hanging over him, agonizing over not being able to find him again– especially by the time he met up with Walter, Matthew and Sarita, as he probably encountered or heard stories about people who survived bites by cutting off their limbs by then. Once he reunited with Clementine and saw that Lee wasn’t with her, he was then forced to face his death.

In conclusion, I interpret Lee and Kenny to without a doubt have feelings for each other, but I believe they never got an opportunity to act on them. Their love story ends with Lee dead, and Kenny left agonizing over what could’ve been. It’s not a happy story at all, but that’s what makes it so good… and if there are any modern AU fics of them out there please send them my way because I am in misery. Again, this is all simply my opinion and I do not care enough to argue about it, though I’d love to hear everyone’s thoughts! Even differing ones given that you’re being respectful :)

#kenlee#twdg kenny#twdg lee#kenny x lee#lee x kenny#twdg#twdg s1#twdg s2#the walking dead game#i did not proofread this sorry if parts make no sense#the hyperfixation hasn't been this intense in a minute#Spotify#Youtube

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

Max Goodwin and Randall Pearson: The Well-Meaning, Incredibly Self-Centered Leading Men We’ve Grown to Love.

Hey fam! Like I said, I’ve been writing a ton of meta lately and this is another one that’s just been sitting in my drafts. It’s basically a This Is Us and a New Amsterdam meta which is something I haven’t done before but something I want do more of. In my Game of Thrones days I used to write a lot of meta about shows and characters that had similarities so this is fun for me. I hope y’all enjoy this. ALSO THIS HAS SPOILERS FOR BOTH SHOWS!!!!!!!

Without a doubt the two most popular shows on NBC is This is Us and New Amsterdam. And what’s not to love? They’re both emotionally driven, heartfelt, shows that focus on incredibly deep and complex topics. Though one show focuses on family dynamics and the other focuses on the healthcare system, these shows are very similar in more ways than one. Case in point, Max Goodwin and Randall Pearson. The more I watch these two shows, the more I realize how these two characters are so alike!!! These two men are kind-hearted, well intentioned, individuals who genuinely want to make some sort of positive difference. They are incredibly ambitious and always have “bright ideas” and “goals” they want to accomplish and somehow they’re able to meet those goals without ever having to sacrifice their wants and needs. By every definition these men are the “main characters” or the ultimate “protagonists.” These are the folks that we are supposed to root for. At the same time, though these men have many traits to be admired, when you truly look at it both of them can be incredibly self centered and selfish especially when it pertains to their romantic partners and love interests. No matter how appealing you make these characters out to be these men clearly fall under the Behind Every Great Man trope.

The Behind Every Great Man trope has been used countless of times throughout Cinema and TV History that I’m sure that I don’t even have to explain it to you but for the sake of this meta this is how it’s defined.

“Behind Every Great Man...stands an even greater woman! Or in about a hundred variations is a Stock Phrase referring to how people rarely achieve greatness without support structures that go generally unappreciated, and said support structure is a traditionally female role via being the wife, mother, or sometimes another relation. This trope is specifically about a man who is credited with something important, but owes much of his success to the woman in his life.”

This trope usually has a negative connotation (and rightfully so) because the man who often benefits from this is an asshole and unworthy of this type of support!

For example:

Oliva and Fitz

Cristina Yang and Burke

Cookie and Lucious

Ghost and Tasha

There are countless others but these are a few of the couples that come to mind for me. Randall and Max aren’t comparable to any of these men that are listed above but they are still operating under the same trope. It just looks nicer because Max and Randall are inherently good and inspirational. They are the heroes of the story. I would even argue and say that both men fall under the Chronic Hero Syndrome trope which is defined as

“Chronic Hero Syndrome is an "affliction" of cleaner heroes where for them, every wrong within earshot must be righted, and everyone in need must be helped, preferably by Our Hero themself. While certainly admirable, this may have a few negative side-effects on the hero and those around them. Such heroes could wear themselves out in their attempts to help everyone or become distraught and blame themselves for the one time that they're unable to save the day. Spending so much time and effort saving everyone else can also put a strain on the hero's personal or dating life.”

Just because Max and Randall have these incredibly inspiring aspirations, is it fair that their wives and love interests are always expected to rise to the occasion and support them. Is it ok for their partners to continuously sacrifice their wants and needs because they love these men?

Let’s dive into it.

Truth be told, Beth Pearson, Helen Sharpe and Georgia Goodwin had to endure a GREAT DEAL to emotionally support the dreams and aspirations of these men while sacrificing so much of themselves in the process. In media we often see women sacrificing so much of their wants and needs out of love for these male leads and rarely do men do the same thing for their romantic partners and love interests. All three of these women clearly fall under the Act of True Love trope defined as

“The Act of True Love proves beyond doubt that you are ready to put your loved one's interests before your own, that you are truly loyal and devoted to them. Usually this involves a sacrifice on your part, at the very least a considerable effort and/or a great risk. The action must be motivated, not by morals or principle or expectation of future reward, but by sheer personal affection.When your beloved is in dire need of your help, or in great danger, and you do something, at great expense to yourself, for the sake of their safety, their welfare, or their happiness, thus proving beyond any doubt that you put their interest ahead of yours.”

Over the past few seasons we have seen all three of these women truly live up to this trope without any true consequences or accountability from the men they’re making all these sacrifices for. For example, in Beth and Randall’s marriage, how many times did Randall spring an idea on Beth without truly talking to her or considering her wants first? Everyone thinks these two are an ideal couple but she has endured A LOT for Randall.

Randall has spontaneously quit his job, moved his dying biological dad into their home, bought his biological dad’s old apartment building, fostered and adopted a child and also ran for city councilman outside of his district. In all of these decisions, Randall “consulted” Beth about it but at the same time didn’t really consult her. In a way there has always been this expectation of Beth to just go along for the ride with what Randall wants. Is anyone else exhausted from reading that list?! That’s a lot for partner to endure and lovingly support. But Beth has endured and has been Randall’s rock through it all!!! What worries me is that the one time Beth spoke out about her wants and needs of pursuing dance again, he couldn’t match the same energy she was giving him and eventually it led to world war three between them. Though things are looking up in their relationship and he’s starting to support her more, has Randall nearly given to Beth as much as she’s given to him? Absolutely not!

Similar to Randall, Max also had a wife who was a dancer. in fact, she was a prima ballerina. Unlike Randall and Beth, Max relationship with Georgia was rocky from the start. When we were first introduced to them Max and Georgia were separated and rightfully so. Georgia was never Max’s first priority. The hospital always came first in their relationship. He couldn’t even dedicate a full night to her for their proposal. In order to “save” their marriage they decide to have a baby and they both committed to taking a step back in their careers in order to do so. The problem was Max didn’t keep his side of their commitment and took a job to become the medical director at the biggest public hospital in the U.S. She gave up her career to start a family and he totally and completely betrayed her trust. So throughout season one we see them trying to rebuild their marriage but even in the midst of trying to rebuild a marriage based on trust and mutual respect Max still keeps things from Georgia. For several episodes he didn’t tell her that he had advance stages of throat cancer. He only told her when Georgia asked him to move back home. That’s fucked up! Then throughout their pregnancy he was never fully there for Georgia because he was either to preoccupied with the hospital or himself. At the end of it all, Georgia died tragically at the beginning of season two and really had nothing to show for it in her relationship with Max other than her daughter Luna.

Now let’s bring Helen Sharpe into the fold. While all of this stuff was going on with Max and his wife in season one, Max was developing a deep friendship, borderline emotional affair with Helen. Their relationship started out with Helen being his oncologist. As the new Medical Director of New Amsterdam, he swore Helen to secrecy about his diagnosis so that he could still run the hospital. Through that secrecy they eventually formed a deep bond but as his cancer got worse his secret was let out of the bag. He realistically needed someone to step up and run the hospital when he was going through chemo and though Helen already had commitments she stepped up and became his deputy medical director. Somewhere along the lines Max and Helen started developing feelings for each other. As Helen becomes aware of those feelings, she made a choice and decides to remove herself as Max’s doctor. He BITCHES about it but eventually accepts the boundary she’s clearly trying to set. Mind you, as this is unfolding, like Max, Helen is also in a new relationship with her boyfriend Panthaki. As Max’s cancer seems to be getting worse with his new doctor, she goes back on her boundary and decides to be his doctor again. This pisses her boyfriend off because he could already peep the vibe between them and he breaks up with her. When we get into season two, Max’s wife died and Helen set him up in a clinical trail (with a doctor she previously fired) that’s helping his cancer. Unbeknownst to Max, this doctor ends up holding his life saving treatment plan over Helen’s head and in order for his treatment to continue she gives this doctor half of her department!

Helen has sacrificed a lot for Max and now in season three she’s finally prioritizing her current wants and needs first! Like Randall, Max is starting to turn a page and is starting to support Helen and truly listen to the wants and needs that she has. All of this is good but my question is did any of these women have to sacrifice so much for the men in their lives to get a clue?

Why is it that this is a trope we see in media time and time and time again? Even if these men are good, why don’t we still keep these male characters accountable when they put their significant others in these situations that are clearly not fair? I’ve watched countless tv shows and I’ve seen a lot of tv couples but I think I have only come across one couple where the male counterpart has selflessly loved his significant other and has always put her needs above his own.

That character my friend is none other than PACEY WITTER

I might be mistaken but I think Joey and Pacey are the most popular ship in tv history and honestly, rightfully so! This is only example I can think of where the male in the relationship so willingly puts the wants and needs of his partner first. It is a completely selfless and sacrificial love. He never wants to hold her back and he never asks her to compromise her wants or needs for him. That’s why I think so many women love Pacey because in a sea of TV relationships, Pacey Witter is a fucking unicorn.

So to wrap this up does this mean that I hate Randall Pearson or Max Goodwin? No! I adore them. I love both of their characters so much. I just think that when we see the media continuously play out the sacrificial wife/love interest for the sake of their male counterparts, it should be called out. I’m all about sacrificial and selfless love but it should come from both sides.❤️❤️❤️

Anyway I hope y’all enjoy this! As always my DMs are opening here or on Twitter @oyindaodewale

#new amsterdam#sharpwin#This Is US#max goodwin#helen sharpe#randall pearson#beth pearson#georgia goodwin#pacey witter#joey x pacey#new amsterdam meta

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

NieR Replicant (Part 2: Themes of Violence and Sacrifice)

In part 1, I examined the doubled narrative form of NieR and suggested that it makes sense to consider the significance of this form as a negotiation of a contemporary desire for stories that exist between myth (timeless, cyclical, and essential) and history (chronological, linear, and causal). In part 2, I wish to deal more directly with some of the themes that began to emerge in my overview of the game’s story in part 1. In my opinion, NieR is notable in the context of contemporary AAA games (big budget games published by one of the industries major publishers) because of it’s concern with the meanings of human behavior. In particular, NieR explores forms of behavior that are commonplace in gaming, but are not often interrogated or placed at the center of gaming narratives. Chief among it’s concerns are the boundaries between the self and other, notably in terms of questions of the distinction between selfish and selfless behaviors. Furthermore, violence and violent impulses are held up and acknowledged as a central aspect of the human character, something that is complex and meaningful and deserving of more careful consideration than what it usually receives in video games, especially given its predominance as a mode of interaction across a wide range of genres.

Starting with the latter, violence in video games is typically treated in one of two ways. Typically it is adopted and embraced as the primary mode of interaction in many games due to it’s exhilarating and demanding forms. In these games, little attention is typically given to the reasons behind engaging in violent behavior or the consequences of such actions. External discourses often celebrate these games as an appropriate release for violent and aggressive impulses that allow the related urges to be sublimated in daily life. Alternatively, critics argue that frequent exposure to violence in these games, especially among children, can lead to an increase in the prevalence of aggressive impulses and a narrowing comprehension of the range of possibilities through which people can interact with others and resolve our conflicts with them.

Violence in video games is typically not scrutinized by the games themselves. It is a means to an end, a way to achieving an engaging interactive experience that emphasizes skill, strategy, and dexterity. However, the alternative trend has been to engage with the critique of violence in video games outlined above in order to tell stories about characters whose violent impulses detract from their ability to function as empathetic, rational, well rounded human beings as well as to present the possibility of desirable alternatives. Two good examples of this sort of game that are roughly contemporary with NieR are the critical darlings Spec Ops: The Line and Undertale.

NieR takes a slightly different tact. Although it too features characters who succumb to violent impulses and are limited and even potentially damaged by the effect of engaging in such behavior, rather than condemn the behavior and the characters who perform it or suggest and provide the opportunity for alternatives, NieR considers violence as a necessary and even essential aspect of a cyclical pattern of behavior that in some ways defines for the game what it means to be human. In other words, the game neither celebrates nor criticizes violence, but instead provides a compelling framework for understanding it that allows us to consider the significance of violence in human nature and contemporary history, as well as in our own behaviors as players of violent video games.

The role that violence plays in NieR is initially one connected to a collectivities prospects for survival. The first creature that the player kills in the game are sheep who wander the plains just north of the protagonist’s village. Killing for food quickly becomes killing for protection as the player is informed of an attack by Shades on a group of human workers attempting to rebuild a bridge that connects several human settlements to the player’s village. From there, killing gradually shifts from something protective and retaliatory to something proactive, capable of fostering greater powers for the protagonist. Once the player has teamed up with Grimoire Weiss and the idea that Shades contain within them “sealed verses”, capable of augmenting the players magical powers and brining an end to the disease that plagues his people, the Shades shift in significance from a menace to resource that must be culled in order to be harvested. The old excuse about needing to protect and/or avenge people still presents itself at different moments of the game, but the player hardly needs a reason to kill. Their violence becomes indiscriminately targeted towards an entire population of creatures, even those that seem to serve no immediate threat and whose elimination fosters the completion of no immediate goal. This process of gradual abstraction where killing becomes detached from more immediate causes and broadly justified by a totalizing mission is a pattern that can be found throughout history, but can immediately and obviously connected with the war on terrorism that Western countries have been waging for the last quarter century.

Along with this evolving rationale for enacting it, violence in NieR also can be connected with a general ignorance and obliviousness to the world one lives in. Throughout the game, strange and unique situations that range from the seemingly evolving intelligence of the shades to the existence of strange and difficult to explain locales and phenomena are hand-waved away by the protagonist in favor of maintaining focus on the more immediately demanding and gratifying violent spectacles in which they are engaged. Even towards the game’s conclusion when information about the circumstances of their world and the consequences of their actions are being directly and forcefully explained to them, the protagonists ignore and block out this information by focusing on the violent acts at hand. There is here a debate about means and ends that can be had such that it could be argued that a focus on the violent means by the characters really reflects their total commitment to their end goals. which are noble. However, it is equally arguable, and in my opinion more convincing given the ways the protagonist’s commitment to their violent actions are demonstrated to be beyond reflection such that even if new information arose that challenged their thinking in terms of how best to reach their goals, they would continue to pursue their violent course because it is the means and not the ends to which they are more committed.

This idea of violence as something so directly engaging that in precludes the accumulation and processing of new knowledge is an interesting one and something that relates back to part one’s discussion of the relationship between myth and history. Violence in NieR seems to have the effect of perpetuating the mythical cycle of extinction and rebirth precisely because it precludes the protagonists becoming aware of the historical context in which they are acting. The protagonist refuses to grasp their role in wiping out a previous form of humanity and it is because they never gain this knowledge about the historical significance of their actions that they are able to carry them out. Violence is, as has often been stated in other contexts, something of a cyclical phenomenon, with patterns of action and retribution that continue in perpetuity across history. However, instead of suggesting that violent atrocities have stood in the way of history, or set society back, it might be more effective to say that violent actions keep people involved at a mythical level of understanding and involvement with the world around them and prevent them from entering into a historical one. Emerging from this, the question that NieR seems to beg is whether or not this mythical level of acting is immoral or not.

The events of NieR are certainly tragic. They concern the extinction of a form of humanity, carried out but another form of humanity that lacks the knowledge of the full significance of their actions. However, the game also seems to suggest that there is little room for alternatives as it relates to this matter. There is no possibility for coexistence between Gestalts and Replicants. Either the Gestalts themselves share this violent predisposition and pose an immediate and unavoidable threat to the Replicants, or else they are as committed to their own survival the the replicants are and rely parasitically on the Replicants to achieve it. This is, of course, most pronounced in the case of the Shadow Lord, who, like the protagonist, will do whatever it takes to save his sister, even if it means committing atrocities against another intelligent form of humanity. Since the parasitism of the Gestalts ultimately leads to madness and the destruction of the intelligence of both Gestalt and Replicant, the elimination of the Gestalt threat is a necessity for intelligent life’s continued survival. While one can empathize with the Gestalt, there is no denying within the system that the game has established, they are, so to speak, on the wrong side of history, which is to say that their existence must come to end for humanity itself to continue. However, their fundamental sameness to the Replicants in terms of their right to be considered human is undeniable. It is this sameness, this inability to distinguish between the moral and human rights of either side that causes a major problem for humanity’s continued existence.

This is where the mythically oriented violent disposition of the protagonist becomes important. The violent outlook is capable of creating dichotomies where none exist, of disrupting markers of commonality and sewing division and discord. While these aspects of violence are rarely celebrated (or worth celebrating) they are capable of allowing life to orient itself by the cyclical form as opposed to the stable form of history. They preclude the definition of the human based on intelligence and consciousness and and preclude rational and emotional connections with others which might break the cycle and establish the alternative trajectories of history. The cycle is a sort of trap or prison, but it is also something that inevitably continues and this may hit closer to the essence of what life actually is than the many ways that historical consciousness allows us to envision life as something that evolves and makes progress, or, alternatively, collapses and comes to an end.

It is in this sense that the game does not render a traditional moral judgment on the actions of its protagonists, what it offers, or at least tries to offer, is an alternative orientation (that of cycle and myth) to view these actions from so as to make sense of them. Moral judgment does not exist in the same way within myth since the cycle is fixed and eternal and thus morality has no weight as a means to determine the direction in which human life should proceed or the means by which it may be judged. However, as stated in part one, the game does not wholly commit itself to myth, nor is the mythical outlook able to supersede the historical. Even if the protagonists fail to grasp the historical weight of their actions, the player has the opportunity to come much closer to doing so. They are torn between two poles, the desire to play the game and the desire to make sense of the story and these poles are roughly aligned with the mythical and the historical respectively.

Playing the game, participating in the thrill of combat, becomes something that supersedes the story world in many games, including NieR. Because combat in games is essentially mechanical, which is to say that it is defined and governed by the rules of an abstract system, it is endlessly repeatable and detachable from its context. It is always possible for the player to detach themselves from the world in which the action takes place and to focus on the combat. NieR itself explores and encourages this relation by encouraging multiple playthroughs in which the details of the story, since they have already become familiar, recede into the background, while the more abstract stimulation of the mechanically challenging combat becomes the focus. However, what is intriguing here is the way that NieR, in a seemingly contradictory manner, ties this mythical and cyclical engagement to gameplay systems into a continued desire for historical understanding. Many games now offer what is commonly known as New Game +, which is basically a mode in which the player can replay the game that they have already completed with the narrative remaining entirely unchaged but allowing them to keep their character/abilities/items/etc. and be faced with more difficult gameplay challenges. New Game + modes obviously place almost exclusive focus on the player’s desire to continue to “play the game”, pushing the story to the background as something that has already been completed and fully experience. However, NieR promises the player small and subtle, yet revealing and significant differences to the narrative upon subsequent playthroughs. As such, in the instances where systems would appear to be the major driver of the experience, NieR doubles down on the desire for story in order to challenge the straightforwardness of this progression towards gameplay focused abstraction.

NieR continues to hold out the prospect of more of the narrative to the players, even after the characters involved and their fates have largely been settled. It conveys the protagonists own imprisonment in the mythical cycle but also delivers to the player the promise of narrative progression. What seems to be the case is that ultimately the pull that NieR makes on the player is undecidable. Instead of narrative receding in the face gameplay as the primary motivating desire upon subsequent playthroughs, it becomes difficult to say at which level the player’s desire is more firmly rooted. NieR offers the possibilty to see its events cyclically by replaying it at the same time that it promises the ability to break that cycle by revealing new aspects of the story. Ultimately, NieR doesn’t restrict its player to either commitment, it asks them to move between the two, to experience the game and its events in both ways, not to judge which is the more proper way to view the game, but rather to suggest that the game is a novel form that allows for the experience and awareness of both.

This seems to me to be one of NieR’s major contentions about video games: that they offer something like an evolution in terms of the way we understand the world as well as tell and experience stories because they lend themselves to this simultaneous mythical and historical engagement with the world in a way that other forms do not. They allow these two forms of desire to coexist without extinguishing one or the other. The player, in the end, does not fully have the means to render a historical-moral judgment on the protagonist because despite their efforts they do not have the full picture. The mythical cycle of the game is incomplete and yet compelling in its form so as to justify itself and its continued existence (similar to the way human life is able to justify its continued existence despite the moral obstacles placed in its way by the narrative predicament NieR poses). However, neither does the protagonist have the ability to fully embrace the myth. There is too much historical and moral weight to knowledge they have accumulated while playing the game to feel that the protagonist and their role in the cycle of extinction and survival can be identified with and accepted. The player finds themselves feeling both inside and outside of this cycle, both related to and estranged from the characters they control. This is a unique position in relation to a story such as this and one that is not entirely satisfying. It presents the player with gaps and contradictions in their own experience as well as in the desires upon which said experience is structured.

If the mythical cycle is a prison that allows life to continue but locks it into an inevitably limited, cyclical awareness of its relation to the world and the historical offers lines of flight that may lead towards shared progress, but are just as likely to lead towards total ruin, NieR puts forward the need for an alternative. This alternative is the perspective of the player, at once within the world and out of it, at once able to know and judge as well as too limited in scope to make such knowledge and judgments definitive. In short, this is a means of experiencing and understanding the world that puts a premium on more immediate involvement in an experience as opposed to more detached contemplation of it, but also wants to include means of contextualizing that experience that are emotionally challenging and thought provoking without being overly moralizing or didactic. As such, what this alternative perspective seems opposed to is the rigidity of uncompromising moral and historical lenses while simultaneously rejecting the atomization and detachment of the cyclical over-investment in direct action (figured predominantly through the figure of violence). It imagines the game as a system for negotiating these two poles and thus for knowing the world differently.

NieR might, in this sense, be seen as functioning dialectically, producing a new means for understanding the world out of a clash between opposed alternatives. In my view, it provides an elegant view of stakes against with humanity threatens to exhaust itself. It offers something fluid yet thought provoking and it leaves us with a sense of these characters and their world that demands more of us in terms of our ability to make sense of it. If neither the mythical outlook nor the historical one can give us a satisfying account of the meaning of NieR, we are spurred to look instead at how we experience the push and pull between these two perspectives in our own experience. This reflexive knowledge that games can create through juxtaposing their systems and narratives with the player’s desires and experiences is, in my view, crucial to getting people to reflect on meaning differently. Whether or not it represents that transcendence necessary for life to mean something more than an a cycle or a linear progression remains unanswered. However, the way it involves the individual and their own negotiation of experience and what can be known about it is important to me, because it involves a fundamentally questioning of how we make sense of things. I hope that it engages people in a way that can’t be resolved by resource to rote ideologies or abstracted patterns of involvement, but instead makes these two domains relative to each other, leaving the player with need to sort through their own sense of how to make these domains most compellingly work together. For myself, as it relates to NieR, this means acknowledging something in my own desire for knowledge of causality that keeps me involved in the mythical cycles of violence that the game depicts. There is something in my experience therefore that cannot be reduced to either one or the other.

------

We can establish a contrast between the way violent impulses and violent behavior function for the protagonists of NieR and the way they function for players of the game. Of course, there are many who do play games with the mentality displayed by the protagonists. They play games for the action, they skip cutscenes, they tune out dialogue, they are bored by anything resembling downtime. For people with this approach, NieR is a game whose story recedes into the background. Important dialogue is often conveyed during fights and thus is easy to ignore. Important portions of the dialogue can even be missed entirely if the player completes segments of fights too quickly, something that in my experience occurred fairly often unless I actively held back. In the second playthrough there are totally new segments of dialogue spoken by the boss-shades that the player fights, but they are not spoken in english (or whatever language the player is playing the game in) and must be read via subtitles, something that is difficult and requires conscious effort during a frenetic fight scene. For the player who is keen to focus on the action NieR makes it easy, but for the player who has an interest in the story, these devices create the kind of dissonance that symbolize the conflict between these two desires through setting the players experience of both at odds with each other.

As such, for the player with some sort of desire to understand the narrative, violent action in NieR becomes something like an impediment to receiving the story. An intense focus on the gameplay, something most action games demand, is actively at odds with the player’s experience of the story. Even player’s like myself who do care about the story and desire to understand it may find themselves slipping habitually into preoccupation with the action and only once it is too late realized that they have missed something that they wanted to see or hear regarding the story. This is highly characteristic of a common vein of difference in video games between the habitual nature of gameplay, particularly fast-pace visceral action oriented gameplay, and the unexpected interruptions of story that seek to command the player’s attention with their difference from the usual experience of the game. It also symbolically stands in for the way certain actions, notably those violent in nature, can stand in the way of our ability to understand the wider context of our actions, as I have already discussed above.

However, in NieR, as in most action games with prominent narrative components, violence is not only an distraction from the story, it is also the only means to access it. In a meaningful contradiction, the player forced to perform the violent actions of the gameplay in order to reveal further aspects of the story. Violence is thus depicted as not only as consuming and narrowing the player’s focus, but also as opening up and revealing more and more about the world. Players do not just commit violent acts in games because they enjoy them, although they may, violence is a means to progression in the overall narrative structure of many games, including NieR. It takes the characters to new places, it introduces them to new people and creatures, and it leads to many other moments of revelation, even as it also actively threatens to obscure and destroy what it potentially reveals. The player is perhaps more aware of this double-edged nature of violence than the game’s protagonists are, especially if they have a desire to understand the world of the game, which the characters who live in that world do not. This struggle between knowing what violent actions are capable of revealing and also understanding how they threaten to destroy or deform those revelations is a major characteristic of the experience of playing NieR. It is an uneasy knowledge that the player may sometimes actively suppress in order to feed their desire for kinetic stimulation while at other times it will erupt and confront them with the limitations of their means of interacting with this world.

Ultimately, if one way to read the gaps and ellipses in NieR’s narrative is to see it as a negotiation between different knowledge systems and are conflicting desires to understand the world, another way to read them is as a critique of our limited means of access to understanding that our means of interacting with that world provide. If we had some other means of interacting with this world we might be able to come to a more satisfying means of understanding it. However, for whatever reason, whether it is because of the limitations of our protagonists or because of the limitations of the commercial video game marketplace that allows this game to exist in the first place, we are left with a story filled with gaps and ellipses because the violent action takes precedence and determines the form of the former. This is a more critical and moralizing interpretation of the role of video game violence, but it is certainly a valid one.

Another similar and yet different interpretation of these same points would claim violence as necessary and integral, not just to this game and these characters worldviews, but to human life in general. It would claim violence as something properly human, something essential to our will to survive and protect our sense of self. As such, the game would be less about the limitations of the protagonist’s or the gamer’s perspective on the game world, and more about the limitations of humanity’s perspective on the world in general. Returning to the points above we could see these limitation as an impediment to a more complete form of historical knowledge that we desire, or we might also see them as the reason we become locked into a cyclical form of knowledge that is always relative to our position in a repeated cycle. Or, as I have more affirmatively suggested above, we may take these limitations as affordances and see them as the tools that we are capable of working with, and from them attempt to devise more satisfying and productive means of understanding the world that do not depend on an outright rejection of the violent means by which we as human beings often propel ourselves forward.

In either case, this is a much more complex and ambivalent take on violence than what we are often granted by other video games, one that forces us to reckon with the integral place of violence in our lives and its role in enacting our desires, even as we recognize how it warps and limits us and the world around us.

----

The other aspect of NieR worth examining is the question of selfishness and sacrifice. Many video games over the years have purported to have moral choice systems. These often boil down to a rudimentary binary where the player is either able to act selfishly or selflessly and see some sort of impact based on their choices in the events of the story and in changes to the world around them. This trend reached its zenith with the 360/PS3 console generation and was typified by the likes of Mass Effect, Bioshock, and Infamous. Although many classic CRPG’s such as the Fallout series featured a wider range of more nuanced moral choices, the distillation of this concept in these more commercially prominent series has served in large part to define how we think about moral choice, for better or for worse, in contemporary video games. Since many of these games (as well as a plurality of games in general) grant players great and substantial powers in the context of their worlds, games are often dealing with fundamental questions about heroism and its possibility. They often treat on the old theme from Spiderman: “With great power comes great responsibility”, and spur the players to think more about the impact that their desire can have on the world around them.

NieR is an interesting game because it bucks many of the presiding trends in video games related to exploring what effects a powerful, potentially heroic character can have on their world. Generally, It doesn’t give the player choices about their actions. The positive or negative effects that the protagonist’s actions have on those around them, such as the decimation of the Aerie or the eventual destruction of Project Gestalt itself are ultimately outside of the players control, part of an escalating cycle of power-accumulation and violence spurred on by the looming threat of extinction for Gestalts and Replicants alike. The player is swept up in a current of events occurring in the world of NieR, acting before they fully understand the implications of their situation, forced to serve as the catalyst in terrible cycle of death and rebirth, an integral part of an enormous machine whose function is beyond their control. In this way, the protagonist’s involvement in the story of NieR is something like an allegory for the nature of the player’s involvement across the medium of video games. Although player’s of video games often do have a great degree of control as it relates to their interaction with gameplay systems, the same cannot be said about the stories and worlds within which such systems are contextualized. Typically moral choice systems in games work to combat or obscure the sense in which the player’s role in determining the story of a video game is pre-determined and their agency circumscribed. NieR takes the opposite track, reveling in making the player aware of the way that the fate of the world of NieR is almost entirely outside their control, regardless of their intentions for it.

While the mandatory missions at the center of NieR’s story always play out the same way, where the player is given more agency to shape the events of the game’s story is in relation to the game’s side quests. Unlike the main objectives that must be fulfilled for the story to progress, side quests in NieR are entirely optional. (The only exception is that if the player wishes to reach endings D and E there are certain side quests that they must complete in order to collect all the in-game weapons. Endings D and E represent the biggest part of the game’s story where the player does have some degree of agency. I will discuss them in more detail later in this piece.) The greatest sense in which the player has agency has to do with whether or not they are interested in taking part in these side quests to begin with. Since they all tend to revolve around the player taking on errands and requests from people who would be at greater risk from the dangers of the outside world than the protagonist would be, these side quests are an important area where the themes of selflessness/selfishness and heroism are explored.

In RPGs, side quests will range in terms of their significance to the larger themes and stories of the games. Often they can be acknowledged as forms of mindless busywork, intended to allow the player a structured means to gain power and resources, or else a way to pad out the game’s content and serve as an interlude between the more eventful mandatory missions. Other games use side-quests to tell relatively robust stand alone stories that contribute to the player’s overall sense of the world and develop the game’s various themes. NieR falls somewhere between these two poles. In NieR, side quests vary in terms of their subject matter, but are generally relatively mundane in terms of the tasks involved. They often revolve around revisiting previously explored areas to kill a dangerous shade or to track down some missing or needed item for a given NPC. However, they are typically much more interesting in terms of how they contribute to the player’s sense of the game’s world and its central themes. While the tasks themselves are typically quotidian, their meaning often deepens and evolves upon reflection. All contain at least a few extended conversations with the quest giver and usually also include some dialogue between the protagonist and Grimoire Weiss. It is in these instances of dialogue in which the characters are able to reflect on and consider the significance of their actions before and after the fact that surprising and unforeseen aspects of them typically become apparent.

There is something like a general pattern that the side quests in NieR follow that I would summarize as the following: The protagonist receives a fairly innocuous request, Grimoire Weiss comments on the protagonists tendency to involve themselves in the problems of others, despite them having their own more pressing concerns, the task is completed, but something begins to feel off about the whole thing, and, finally, the player returns to the quest giver where they are forced to confront the reality that some other purpose was being served by the protagonist’s actions then the one they thought they would be fulfilling. The general tone of these quests can range from the silly to the serious. In one, for instance, the player helps a family to track down their missing son, only in the end for it to be revealed that said family was a family of criminals and that the son who you tracked down and forced to return home was attempting to flee a life of crime. This ends up feeling strange and slightly comical, a sort of “whoops, perhaps we should have been more careful about what we were getting ourselves involved in,” moment. In another, things become much more serious, when upon delivering letters to an old woman who lives in a lighthouse at edge of the village of Seafront it is revealed that the letters that arrive from the woman’s lover living overseas are an elaborate multi-generational ruse devised by the villagers to protect the woman from learning that her lover is dead and to ensure that she continues to wait in Seafront and continue to operate the lighthouse to the benefit of the entire community. At the conclusion of the quest, the player is given the opportunity to tell the old woman the truth about these letters and the fate of her lover or to continue to perpetuate the lie.

Apart from the choice about whether or not to engage with these side quests in the first place, these sorts of unexpectedly harrowing decisions about whether or not to tell someone the truth about the sinister, deceptive, and/or tragic circumstances of their life are the other major form of agency that the player has in the side quests that they do not have in the main quest. Their decisions ultimately do not substantially change the events of the game or the world around them. Sometimes they lead to the player receiving one reward or another, but more often than not, their only impact is in terms of how the NPCs involved understand the significance of their lives, as well as how the player views the protagonists responsibility to these characters. The player may choose to lie and keep the truth of a situation from an unwitting NPC or they may choose to tell them the truth. However, even in the latter context, the NPCs always reach an acceptance of this revelation that allows them to keep living their lives be at peace with the tragic or unexpected circumstances that have affected them. While the player may have feeling that they express through their choices in these moments about whether these NPCs are better off knowing the truth or remaining blissfully ignorant, ultimately their choices do nothing to alter the fates of the characters involved, nor their own. Telling the NPCs the truth doesn’t do anything to make the player more able to face the truth of their own situation. Neither does choosing to keep the truth from them cause the player to look away from the reality of the circumstances they are in.

Ultimately, the characters in NieR are compelled to live their lives, to fulfill their roles in their societies, whether or not they are given the opportunity by the player to come to terms with the truth. The player may agonize, feeling the weight of the choices that are put in front of them and their responsibility to these NPCs, but ultimately the player and their choices don’t have the ability to change the lives of these characters, for better or for worse. The player may have the desire to act selflessly, to behave heroically, or else they may make choices out of self-interest that best serve themselves. However, despite having the power to be in this position where the player has the ability to imagine themselves as a hero, in truth, if heroism and selflessness are about having the power to make sacrifices that improve the lives of others, then the player is ultimately unable to live up this standard. In this sense, we can see NieR as being about how a powerful and potentially heroic figure remains relatively powerless in the face of larger and more mysterious forces that they fail understand, let alone control, or, alternatively, only understand too late when the opportunity to make a decision that might positively or negatively affect the lives of those around them has already passed.

This “too little” or “too late” sense of heroism is ever-present in NieR and goes a long way towards contributing to the general aesthetic of the game. It is a markedly different experience of having power and aspiring towards heroism than the ones that are typically offered by other video games. It conveys a sense in which having power is not the same as having agency, but instead contributes to a more acute sense of ones limitations. NieR is a game about being trapped in a cycle, about the inevitability of tragic events, and about a desperate desire to resist those things that must remain largely thwarted. What it means to try to act heroically in this context serves as a powerful and enlightening corrective to the sense of heroism put forward by other games and media.