#andes amazon fund

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#andes amazon fund#andes mountains#amazon rainforest#ecuador#good news#environmentalism#science#environment#nature#animals#conservation#climate change#climate crisis#south america#protected land#protected areas#wetlands

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

From the article:

This past October 18th, 2024 the Bosque Escondido de Ingavi municipal conservation area was established which safeguards 1,132,127 acres (458,155 hectares) of Amazonian forests, representing 84.5% of Ingavi’s municipal territory. Its area encompasses both terra firma forests (tropical forest that does not get seasonally flooded) and flood forests, giving a high ecological value to the area and turning it into a refuge for flora and fauna. In addition, it is considered by communities as a key pillar for the local economy and a source of vital sustenance. The creation of the Bosque Escondido de Ingavi municipal conservation area also contributes to reducing the effects of climate change, preventing fires and conserving rivers and aquatic species. Within its limits flow important rivers such as the Orthon, Manu, Abuná and Río Negro, which play an important role in the water cycle and the ecological balance of the region and guarantee a sustainable future for the communities and the next generations, based on balanced coexistence with nature.

This is over one million acres of Amazonian forest conserved!

#Amazon#conservation#forest conservation#rainforest conservation#ecology#environment#habitat#biodiversity#good news#hope#hopepunk#habitat conservation#rainforest#Amazon rainforest

168 notes

·

View notes

Text

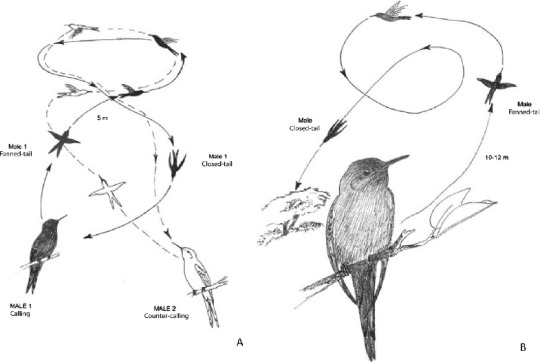

this is the place to post about your knowledge and i’m thinking about my little royal sunangel (from the coquette hummingbird family) google deep-dive and i wanted to show you guys these rare little bastards!

this is a male (left) and female (right) sunangel, they’re sexually dichromatic (different colors indicate different sexes) and so, so teensy! they’re roughly 4.3-4.7 inches/10-12 cm long from their beak to their tail!

they’re as little in number as they are little in size, too. they are exclusively found in the bordering andes area ecuador and peru share, where there are subtropical elven forests (because everything about them deserves a pretty name). there are only 8 known sunangel habitats within this area. when documentation started, around the start of the 2010s, there were 12. the estimated population of this endangered bird is anywhere from 3-7 thousand. the royal sunangel population has been steadily — and scarily — declining since their discovery in 2009, and this is largely attributed to the deforestation due to frequent forest fires and the conversion of their habitats into agricultural fields.

it feels like the royal sunangel JUST got discovered, and the scientific community has only JUST started noting down how unique they are among their hummingbird family and birds at large, and now their delicate little frames and stubborn commitment to their habitat range might lead them to death’s door before i reach middle age and have the credentials or cause to observe them myself. ornithologists love these little guys because they feed in these little circuits so no two (super territorial) males may meet, and when they feed, they either stalk and eventually eat insects or take nectar from shrubs and flowers using the punctured feeding holes of some other animals’ labor. also, you know how hummingbirds famously hover while they feed? these hummingbirds are the only ones who don’t. they perch and relax (as is only sensible)!

If you find them as charming as I do, or if you have a heart, you’re probably asking yourself how we go about conserving these birds in the first place.

well, on the agricultural front (which is more heavily an ecuadorian obstacle for these habitats), the situation feels more complicated. ecuador’s market relies on agricultural exports and i don’t see how tumblr users could make the government prioritize sustainability over profits. There are already conservation groups trying to fight that good fight and buy properties on these fragile biodiverse lands before agricultural companies can (you can punch in neoprimate.org for a good one, my link function isn’t working on here) and if you can donate a little to these initiatives you’d be contributing to the protection of tons of endangered species in the local areas.

another way to prevent habitat loss is by funding efforts to prevent the forest fires that frequently wipe out habitats around this area, especially those in peru (the area with the majority of sunangel habitats). there are legal and activist groups putting energy towards that that’s linked above, but another subtle improvement is to provide local farmers and residents with fire weather forecast devices. this way, everyone will be on the same page, and know that if it’s an arid/risky day to light a fire, they should act conscientiously. these devices are being circulated and groups are educating about and encouraging them to the local communities and could use some help in these links. below, i have a screenshot from an organization that doesn’t have a clear donation link for me, but i heavily encourage supporting, because ultimately i think local, sustainable, community-based and indigenous-prioritizing efforts are the way to go.

thanks so much for listening to my little spiel about these cuties, and i hope this information brightens your day and motivates you to care about the beautiful things we can protect. 💙💜

#conservación#conservation#ornithology#birdblr#birdlovers#birds#birdphotography#hummingbird#royal sunangel#peru#ecuador#conservatism#amazon#rainforest

453 notes

·

View notes

Text

More spoons to go with these spoons. 🪴

“Go.”

“It’s for a month.”

“Yeah, you mentioned that. You should go.”

Before Ronan, Adam wouldn’t have thought twice about agreeing to a conservation trip. As soon as he received an email with an offer, he would have said yes without hesitation and immediately started preparing, making lists of what he needed to pack and scheduling appointments for vaccinations. Because as much as Adam loved his job at the United States Botanic Garden, the opportunity for fieldwork, to see species where they were meant to grow and not in pots in a greenhouse—Adam had caught an itch for it in college and every once in a while it flared up enough he needed to scratch.

But after Ronan—

“That’s a long time,” Adam said from his place sitting on one the workbenches in Ronan’s woodshop. A pellet stove in the corner chugged out heat, but Adam still wore his coat, hat, scarf, and one glove, his other hand bare so he had a better grip on his phone as he read the email about the trip to Ronan: someone from Brooklyn Botanic Garden backed out, someone else recommended Adam, would he like to go to the Andes for a month and collaborate on conservation efforts in the Amazon. “And it’s short notice.”

“When did three weeks become short notice?” Ronan looked up from the pattern he was carving into a drawer front to meet Adam’s eye before he went back to work. “And a month is not a long time.”

Nine months ago, Adam would have agreed. He’d gone to conferences and on business trips with far less lead time than three weeks, and he’d been on research trips longer than a month. But since he’d started things with Ronan, a week of vacation at the Barns passed in the blink of an eye while a Tuesday night in D.C. was languorous if Ronan was there.

Time, Adam found, did funny things when he was spending it with Ronan Lynch.

“So a month’s not a long time, but last weekend you got pissed off when I had to drive down here Saturday morning instead of Friday night,” Adam said. “That was all of, what, twelve hours?”

“You’re making—I know you’ve got a science term for this.”

“False equivalency.”

“Yeah, that. You’re making a false equivalency.” Putting his gouge down, Ronan brushed wood shavings off the drawer front before sitting back on his stool and crossing his arms over his chest as he looked at Adam. His safety glasses—not plain plastic ones like Adam sometimes wore, but a black-framed aviator style—turned Ronan into a 1980s computer nerd, and Adam was a little distracted as Ronan continued. “You staying in D.C. to help Gansey because the Pig shit the bed again is different than you going away for a month when I know about it three weeks in advance. I had plans that night that were—disrupted.”

“Your plans were delayed. I’m pretty sure they happened as soon as I walked through the door.” Setting his phone down next to him, Adam pulled on his other glove and pushed himself off the workbench. “And I’ll argue a month’s worse than a night.”

“So defend your argument, Dr. Parrish,” Ronan said, smirking a little as Adam approached him. He still wore his hat, but he’d lost his gloves and coat as soon as he’d started working, though Adam knew he had thermals on under his t-shirt and hoodie. “Tell me all the reasons you shouldn’t go to Peru.”

Adam had no defense that would hold water, no legitimate reason he shouldn’t go to the Wayqecha Cloud Forest Research Station to document and preserve native local plants threatened by ongoing timberline migration. There was funding for airfare and room and board, so money wasn’t an issue. It would be a good thing to stamp his name on, to associate with the Garden’s conservation efforts.

The reasons for Adam’s reluctance were personal, something he’d never let impact his work before, and it was a strange feeling. But going away for a month affected Ronan too, and even though Ronan told him he should go, Adam knew sometimes Ronan put Adam first without fully acknowledging his own wants and needs. Adam wouldn’t ignore that. He loved Ronan too much.

Sliding between Ronan’s stool and the table he was working at, Adam mirrored Ronan’s posture, crossing his arms over his chest as he made his first argument. “Not seeing you for one night is more tolerable than not seeing you for—” he paused and did a quick calculation of the length of the trip “—twenty-nine days.”

“I’ve gone more than twenty-nine days without seeing you.”

“Before you met me, yeah,” Adam said. “Since, I think the longest we’ve gone without seeing each other is four days.”

Ronan tipped his head a little from side to side, as if he agreed with this part of Adam’s argument. “Alright, so it’s a long time. What else?”

“Cell service is probably non-existent.”

“There are these things called satellite phones.”

“Funding only covers dormitory housing.”

“Better than camping.”

The next wasn’t a defense Adam was proud of, but he gave it nonetheless. “I’ll miss Valentine’s Day.”

Ronan’s reaction was precisely what Adam anticipated. He stared at Adam for a long moment before he asked, voice derisively flat, “Do you really give a shit about Valentine’s Day?”

“I don’t have enough data to make an informed opinion,” Adam replied.

Laughing loudly, Ronan shook his head as he uncrossed his arms and pushed Adam’s out of the way so he could unzip Adam’s coat. Tucking his hands inside it, he held onto Adam’s ribs, burying his fingers in Adam’s sweater as he looked up at him and said, “You’re a goddamn nerd. You know that, right? What else?”

And though he was doing everything he could to not say it, Adam only had one more defense. One that was short and truthful but increasingly important, something he didn’t recall ever saying to anyone before. Even the thought of it left him a little raw and bruised, the kind of thing he couldn’t stop himself from prodding, and Adam pushed firmly against it until he finally said, “I’ll miss you.”

“Do you think I won’t miss you?” Ronan’s face softened as he climbed off his stool and stood in front of Adam. “I will, asshole. You know I will. It’s going to be fucking awful.” Taking one hand out of Adam’s coat, Ronan took off his safety glasses, and, looking at Adam unobstructed, he said, “But you would have gone before you met me.”

It was true, Adam would have, but part of him still wanted Ronan to ask him—to tell him—to stay, to not fly three thousand miles away to a remote research station in Peru’s cloud forest where they may only have the chance to talk a few times over the course of a month. Living where they did, they couldn’t see each other constantly, but they spoke everyday, made arrangements to see one another on weekends and a time or two during the week. They were well acquainted with being together, apart. It wasn’t perfect, but it worked, and if either of them had a desperate need, they were only two hours away, not three thousand miles, a thirteen-hour flight.

But Ronan would never ask Adam not to go. The trip could be a month, two, six, and his response would be exactly the same. He’d never want to be the thing that stood in Adam’s way and stopped him from going after the things he wanted.

Just like Adam never wanted to stand in Ronan’s way either.

As much as their roots had tangled, as often as their trunks were parallel, there would be branches they’d have to travel alone. This would just be the first of many for Adam, and though he’d traveled through life perfectly fine before meeting Ronan, now that they were inextricably linked, those solo journeys felt like a real pain in the ass.

Particularly being apart for a month.

“I would have” Adam said after a moment, wrapping his arms around Ronan and pulling him close so they were chest to chest. “I would have said yes as soon as the message hit my inbox.”

“So go, Adam,” Ronan replied gently, putting his glasses down on the table behind Adam and pushing his arms under Adam’s coat again. Swaying them from side to side, Ronan leaned in and kissed Adam, murmuring against his lips, “I’ll be right here when you get back.”

After Ronan finished working, they walked back to the farmhouse through the few additional inches of snow that accumulated while they’d been in Ronan’s workshop, and sitting in front of the fire, Adam agreed to the trip.

Then he put his laptop away and showed Ronan a little appreciation.

In the lead up to his departure, Adam took a few days off and went to the Barns, where most of his time was spent in bed having frequent, feverish sex with Ronan, like they were far younger than they were, like they were stocking up for the time they'd spend apart. Then the day of Adam's flight, Ronan drove him to the airport and stayed with Adam as long as he could, until they had no choice but to part at the entrance for security.

Standing in front of Ronan, Adam held onto the lapels of his jacket, fingers clinging to the butter-soft leather. He wouldn’t rehash things they’d talked about repeatedly the past few weeks—emailing was the best way to stay in touch, Ronan would work with Gansey and Blue to keep Adam’s plants alive, Adam would call whenever he could, he would not bring Ronan an alpaca as a souvenir—so all Adam said as he stood toe-to-toe with Ronan in Dulles was, “I’ll see you when I get back.”

He could have said he’d miss Ronan, but he didn’t want to say it more than he had to, like it would lose its weight, its meaning, if he said it too much. And Ronan already knew; Adam didn't need to remind either of them it'd almost be Spring before they saw one another again.

"Twenty-nine days," Ronan replied, and a fizzy warmth spread through Adam, knowing Ronan was already keeping a countdown. Folding Adam in his arms, Ronan put his lips to Adam's cheek and murmured, "You'll be so busy doing all your plant nerd shit you won't have time to think about me."

That was untrue. Adam couldn't remember the last time he'd passed a waking hour without thinking about Ronan, because there was always something to remind Adam of Ronan, even if it was only leftovers from dinner the night before. It also made Adam think of the converse, that Ronan wouldn’t be busy with plant nerd shit and would therefore have plenty of time to think about Adam, and Adam didn't like that thought.

They kissed and hugged harder, and as the zero hour approached, when Adam was at risk of missing his flight if he didn't get in the line for the TSA, they said goodbye. Ronan lingered until Adam had to put his backpack on a conveyor and take his shoes off, and after he passed through scanners and retrieved his bag and shoes, Adam looked back to the check-in area and Ronan wasn't there.

He'd thought it was impossible to already miss someone he'd just seen so much, but he was wrong.

A layover in Lima, a night in Cusco, and a four-hour drive later, Adam arrived at the research station. He settled into his shared room, took Tylenol for an altitude sickness headache, and in his first spare moment, he connected his laptop to the patchy WiFi in the dining room.

He had an email from Ronan waiting for him in his inbox, just a single line.

28.

Adam replied, An eternity.

And though it might have seemed like an eternity, it passed quickly. There were plenty of plant nerd things to keep Adam occupied: cataloging current species to compare against the last census, observing more protected Phragmipedium in the wild than he’d ever seen in person before, collecting specimens in the hopes he’d discover something undocumented and get to name an orchid.

But the remoteness, the quiet, the lack of connectivity to the outside world, gave Adam ample time to miss Ronan. He tried filling his free hours with books he’d loaded onto his ereader and playing cards with the other researchers on the trip, but he wasn’t immune to sending the occasional brooding email. It’s so green it reminds me of the Barns last summer, and If we met ten years ago I could have missed you then instead of now.

To the second, a single-line reply came within a minutes: The elevation is doing something weird to your brain. Another email quickly followed: I miss you too. A third: Stop being maudlin. Youre turning into Gansey. And a fourth: 9.

8.

5.

2.

Finally, it came to an end, and while Adam was glad for the time and opportunity at Wayqecha, he was also glad to leave.

To go home.

To see Ronan.

Which were really one in the same.

The day before he flew back to Washington, Adam started the reverse trip, and in Cusco, he walked around the city, picked up souvenirs, found a barber. There was another layover in Lima and the flight to Dulles felt interminable, but then the plane pulled up to the gate, Adam proceeded through customs, and there was Ronan, waiting for him in the baggage claim.

The sight of Ronan, smiling sharply, blue eyes brilliant, waiting for him—waiting for Adam to pick him up, to take him home—snagged around Adam’s spine and carried him forward, and it took more than a little self restraint not to run. A month, he thought as he walked toward Ronan, wasn’t so bad if this was what awaited him at the other end.

“What is this?” Ronan asked without greeting once Adam reached him, putting his hands on Adam’s face, Adam’s beard. A little wide-eyed and a little slack-jawed, he scratched his finger through the coarse blond hair on Adam’s cheeks and jaw, and beneath Ronan’s hands, Adam grinned so hard he thought his face would get stuck like that.

“When a man doesn’t shave the hair on his—”

“Jesus, shut up.” Ronan pulled Adam to him and kissed him hard for a long, long moment, so long Adam thought he was back in the Andes from how breathless it left him. When eventually he broke the kiss, Ronan left his lips against Adam’s and shook his head a little as he muttered, “I don’t like it. ”

“Come on.” Adam kept his face close to Ronan’s and moved back just enough to grab Ronan’s chin, Ronan’s own stubble rough against his fingers. It was exactly how Adam liked it, darkening Ronan’s jaw in a way that made him look a little rough and rugged, like Ronan wanted to be Adam’s favorite version of him when Adam got back. “You haven’t even given it a shot.”

Ronan shook his head again and swatted Adam’s hand so Adam dropped it from his chin, and despite his apparent dislike of Adam’s beard, he put his hands on Adam’s cheeks again. “I don’t care. It covers up your pretty face. Get rid of it.”

All at once, it felt like they hadn’t spent any time apart at all, like Adam hadn’t been gone for a month, because they’d fallen right back into the comfortable casualness they’d had since the very beginning. Adam had missed that almost as much as he’d missed Ronan, the easy touches, the mild teasing, the small, intangible things that came with loving Ronan Lynch.

“Okay. Point taken,” Adam replied. “If you still hate it in the morning, I’ll shave.” He had grown the beard more for ease of getting ready than aesthetic, and while Adam didn’t mind it after the initial itchiness of growing it out, he didn’t want to impede Ronan looking at his pretty face.

“That,” Ronan said as the buzzer for the baggage carousel delivering the luggage from Adam’s flight echoed through the baggage claim, “assumes we’re getting out of bed tomorrow.”

Laughing, Adam wrapped his arms around Ronan and kissed him again as the carousel came to life and started spitting out bags.

He was so, so glad to be home.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quantitative Ecologist Andes Amazon Fund Join the team studying how Amazonian biodiversity is responding to climate change See the full job description on jobRxiv: https://jobrxiv.org/job/andes-amazon-fund-27778-quantitative-ecologist/?feed_id=84052 #biodiversity #Climate_Change #statistics #ScienceJobs #hiring #research

0 notes

Text

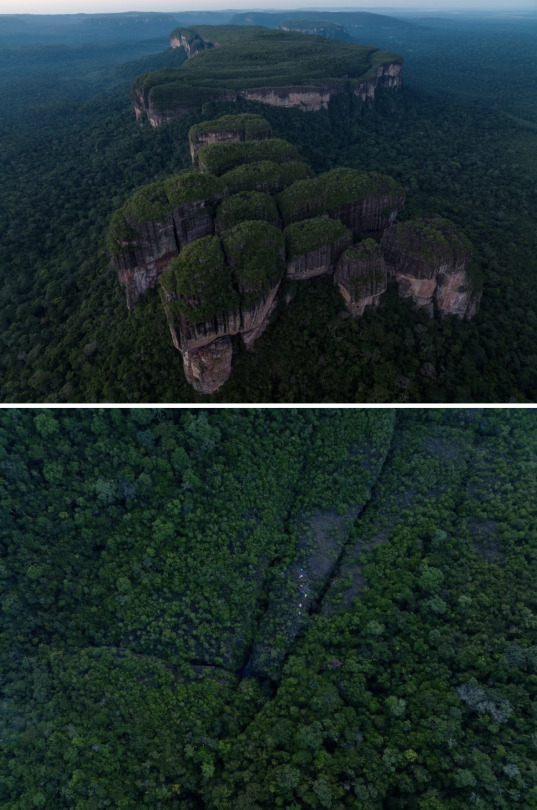

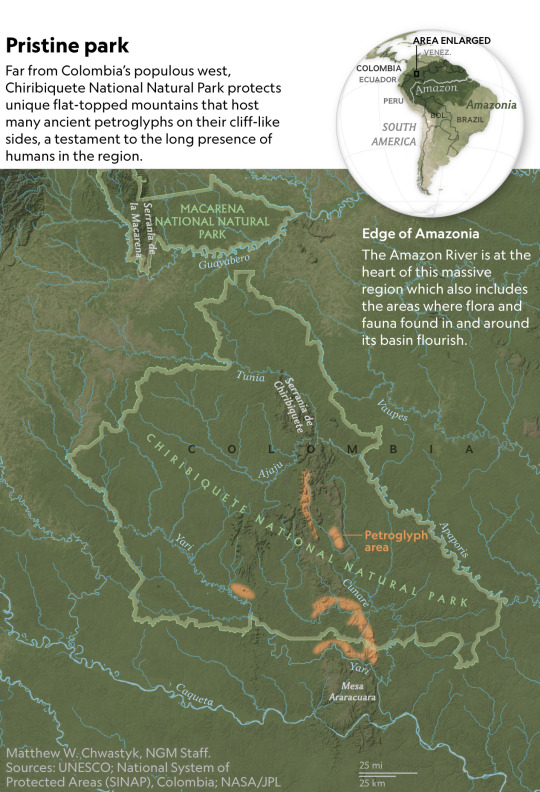

Chiribiquete National Park, the largest protected area in Colombia, is distinguished by its tepuis, tabletop peaks that rise abruptly from the rainforest. The area, with waterways that feed into the Amazon, is one of the world’s most biodiverse and is home to many unusual endemic species.

Rarely Seen Cliff Art Reveals The Majesty Of The Amazon’s Aquatic Realm

In a two-year expedition, a National Geographic photographer is documenting the mighty river and the greater ecosystem from the Andes to the Atlantic.

— Story and Photographs By Thomas Peschak | March 22, 2023

Two jaguars leap into the river, lunging at pacas. These oversize rodents, with blotched and striped coats, are agile swimmers. Piranhas, attracted by the commotion, hover nearby.

I’m photographing this riveting scene, but I’m not underwater as I usually am when I’m on assignment. Instead of diving to see this aquatic life, I’ve climbed to a rocky ledge far above a rainforest. The jaguars, pacas, and piranhas are not flesh and blood; they are prehistoric artworks painted with hematite, a blood-red iron oxide, in exquisite detail. I am in awe, as if seeing the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel for the first time.

These pictographs in Colombia’s Chiribiquete National Park, tens of thousands of years old, are evidence of humankind’s long relationship with the world’s greatest freshwater ecosystem. I’m part of the National Geographic and Rolex Perpetual Planet Amazon Expedition, working closely with other National Geographic Explorers doing critical research in the hope of securing the future of this watery realm, which has been neglected by science and the media.

The rainforests, an essential and endangered counterweight to climate change, have overshadowed the mighty river. From the Andes to the Atlantic, the Amazon flows for 4,150 miles, the main artery of a web with more than a thousand tributaries and tens of thousands of streams in an area the size of Australia. For two years, I will photograph the river, from high in the mountains to far out into the ocean. Unlike most storytellers who have ventured here, I will dive below the surface to reveal a rarely glimpsed aquatic underworld.

The National Geographic Society, committed to illuminating and protecting the wonder of our world, has funded Explorer Thomas Peschak's storytelling about the natural world since 2019. Illustration By Joe McKendry

In the cosmology of the Tikuna, one of the largest Indigenous groups in the Amazon, pink dolphins are mischievous spirits and guardians of the watery realm. Elders Nuria Pinto and Pastora Guerrero join dancers wearing dolphin costumes made from the inner bark of the sapucaia tree. (Top)

Jaguars leap at pacas while piranhas swim on a panel known as “Hojarasca” (“Fallen Leaves”). More than 75,000 paintings have been discovered in Chiribiquete. Some are 20,000 years old, making them the most ancient rock art in the Americas. The pictographs show fauna and flora, people, and geometric patterns. Large jaguars and aquatic life are common motifs. (Bottom)

A few months ago, I photographed at my geographical starting point, the peak of Nevado Mismi in southwestern Peru, the farthest point from the Amazon’s mouth, where the waters flow uninterrupted all year. I’m in Chiribiquete to explore a different type of beginning and origin.

Here, the Amazon’s first storytellers painted the most ancient visual stories ever found in the Americas. More than 75,000 paintings have been discovered in more than 70 murals, cementing the park as the Louvre of rock art in the Americas. The pictographs include fauna and flora, people, and geometric patterns. Jaguars, sometimes life-size, are one of the most common motifs—each with a unique pattern of rosettes or lines.

The ancient shaman artists chose the most spectacular locations to create their pictographs. The “Hojarasca” (“Fallen Leaves”) panel—the jaguars hunting pacas among piranhas—is located on the pillar at the far left, behind the one in the foreground. This expedition was only the ninth to be granted permission to explore the vast Chiribiquete National Park. (Top)

The expedition base camp was set up on a small patch of uneven rock that turns into a furnace during the day, with the solar-heated rock baking the air in the tents to more than 100 degrees Fahrenheit. The lack of shade and overwhelming number of sweat bees made the location nowhere near as idyllic as it first appeared. (Bottom)

I am with a small team, which includes aquatic biologist and National Geographic Explorer Fernando Trujillo and archaeologist Carlos Castaño-Uribe. A group of Colombian climbers and jungle specialists is with us so we don’t get lost in the trackless wilderness. We are only the ninth expedition to be granted permission to explore Colombia’s largest park, which protects a spectacular landscape of dense rainforest and soaring tabletop mountains called tepuis.

For 25 years I have documented our planet’s wildest seas, first as a marine biologist and later as a photojournalist. I am well versed in how not to get bitten by a shark or crushed by a feeding whale, but I am a neophyte in the jungle. In my defense, Chiribiquete is an incredibly difficult place to explore, and the ancient artists chose some of the most inaccessible locations.

A Challenging Landscape

The helicopter takes off from the small airport of San José del Guaviare in south-central Colombia; the landscape below is a patchwork of cattle pastures and grasslands. Finally an unbroken carpet of pristine rainforest rolls out to the horizon. When the first mountains appear, the pilot descends, and we navigate through canyons so narrow that I can almost reach out and touch the cliffs. We land on a scrap of uneven rock. The helicopter barely fits.

The location appears idyllic, but it feels as if we’ve set up camp on a furnace. As the sun heats the rock, it bakes the air in our tents to more than 100 degrees Fahrenheit. I try to fall asleep, desperate for a breeze. My sweat forms wetlands on my mattress.

A helicopter is key to getting to and around Chiribiquete, as the terrain is extremely rugged and difficult to traverse on foot. To reach rock art painted in some of the most inaccessible places means rappelling down cliffs, bushwhacking through thick rainforest, and battling unrelenting bees. (Top)

National Geographic Explorer and scientist Fernando Trujillo (far left) and his team examine a boto, or pink dolphin, a keystone species in Amazonian rivers. Their assessments, which follow established safety protocols, provide critical information about the health of not only dolphin populations but also the rivers. (Bottom)

We wake to the sound of tens of thousands of tiny helicopters. The sweat bees are here. Soon the entire camp—camera cases, boots, clothing, plates, cutlery, anything left outside—is draped in bees. I make the mistake of leaving my tent zipper slightly cracked and before long end up with dozens of roommates. I let the bees quench their thirst from the sweat lake in my belly button. Resistance is futile. The bees overwhelm us. They crawl into our noses and ears; one even slips beneath my eyelid. A head net becomes mandatory.

The lowlands adjacent to rivers that flow through the park have hardly any sweat bees, but we were advised not to stay there. Remnants of FARC rebel forces are said to use these rivers when the water is high enough. I prefer bees to AK-47s.

Once, on an expedition in 2017, Trujillo woke in the early hours of the morning to the sound of footsteps. Thinking it was another researcher, he went back to sleep. The next morning, the scientists discovered smaller footprints, barefoot, in step with their boot prints. Indigenous Karijona, Murio, or Urumi people—uncontacted or living in isolation since violent encounters with rubber tappers in the 1800s—inhabit the headwaters of the park’s most important rivers. More than 50 miles of difficult terrain separate them from our campsite, but before falling asleep, I listen intently for the rustle of leaves or the crack of a twig.

Streams and rivers that flow from rocky plateaus run clear and are habitat for unique plants and animals. In the Serranía de la Macarena, a mountain range northwest of Chiribiquete, endemic Macarenia clavigera turns red in sunlight but remains green in shaded waterways. (Top)

A wolffish (Hoplias malabaricus) rests beneath a waterfall in the Caños Cristales River in the Serranía de la Macarena, obscured by a curtain of aerated water and camouflaged against a rocky ledge. This ambush predator waits for small schooling fish to swim within reach before lunging explosively and swallowing prey whole. (Bottom)

In the 1940s, Harvard ethnobotanist Richard Evans Schultes was the first scientist to note what he called Indian paintings on Chiribiquete’s cliffs. But he didn’t realize he was surrounded by one of the most extensive rock art repositories. This became apparent only in the 1980s when a storm pushed Castaño-Uribe’s Cessna off course and he spotted a mountain range that wasn’t on any of his maps. He returned to explore, saw the pictographs, and decided to devote his life to Chiribiquete. Not only did he publish the first detailed descriptions of the paintings and connect them to Indigenous cosmology, but he was also instrumental in the park’s establishment in 1989, expansions in 2013 and 2018, and selection as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2018.

The oldest paintings here have been radiocarbon-dated to 20,000 years ago, but the youngest are from the 1970s, and compelling evidence shows that some are even more recent. On another expedition, Castaño-Uribe found a small hearth with animal bones and pigments beneath some paintings, indicating the art continues to be meaningful in Indigenous cosmology and ceremonial activities.

Hacking, Hiking, Rappelling

Before our expedition began, Castaño-Uribe consulted a shaman in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, a mountain range near the Caribbean coast. To ensure a safe return and appease the spirits of the sites, the shaman advised him that we should make an offering of tobacco—sacred to many Amazonian Indigenous groups—before approaching the paintings. At the base of a sandstone tower, Castaño-Uribe passes around fat cigars that would not look out of place during a poker game. We puff vigorously, bathe ourselves in smoke, place our palms on the rock, and earnestly state our intentions. For extra measure, Castaño-Uribe exhales smoke over each of our heads.

Only then do we begin to explore.

Sweat bees swarm videographer Otto Whitehead. Within minutes hundreds landed on him to lap up the nutrients and proteins in his perspiration. At least 11 species of the stingless bees abound on Chiribiquete’s tepuis. For this expedition a head net was essential gear. (Top)

The Caño Cristales carves these pits, known as giant’s kettles. They’re sculpted when hard pebbles fall into small cavities and are tumbled around by the current, over time scouring the cavity to form round pocks in the quartzite riverbed. (Bottom)

After hours of hacking through dense foliage, a dark canyon spits us out onto a narrow ledge next to a vertical cliff. We are at a site named “Los Gemelos” (“The Twins”). The rock art depicting stingrays, otters, and turtles is magnificent—and fiercely protected by bees. This time not the annoying stingless sweat bees but more virulent honeybees.

In less than half an hour the team collectively endures more than a hundred stings. We retreat, but the bees follow, and a rock wall that requires a fixed rope to climb becomes a bottleneck. Castaño-Uribe and I are waiting when he decides he has had enough of being stung. He bypasses the rope and, in a crouched run, scales the near-vertical 30-foot cliff, leaping from tree root to tree root, from branch to branch, Tarzan style. Not wanting to be left to the mercy of the belligerent bees, I follow, and despite being 15 years younger, I struggle to keep up.

Every morning we set out by helicopter and then on foot, climbing steep and densely forested slopes, rappelling down cliffs, and hauling ladders to navigate dark and damp canyons. Less than a half hour into one ascent I am close to collapsing because of my armored fashion choices. I’m layered up with thick combat pants, two shirts, gloves, a head net, and a pair of snakebite gaiters. I will do whatever it takes to protect myself from enemies, both real and imagined.

The park’s mountains soar from the rainforest floor, creating complex microclimates. Rising water vapor feeds the clouds, accelerating the formation of rain. More than half the precipitation in the Amazon stems from its own evaporation and transpiration. A fifth of the world’s fresh water is in the Amazon Basin. (Top)

Archaeologist Carlos Castaño-Uribe is dwarfed by a rock art panel named “Los Gemelos” (“The Twins”). These pictographs of jaguars, otters, stingrays, and turtles are stunning—and fiercely protected by honeybees. After enduring more than a hundred stings, the expedition team abandoned this site in a hurry. (Bottom)

The ferocious sting of bullet ants, a whopping 4 on the Schmidt pain index, is described as akin to walking across hot coals with a three-inch nail embedded in your heel. The potentially lethal fer-de-lance is responsible for most of the snakebites in the Amazon region. The bite of a female phlebotomine sand fly could infect me with disfiguring leishmaniasis. With every labored step in the stifling heat, I ask myself again and again what I’m doing in the Amazon.

I remind myself that this is just one chapter in my journey. Soon I will be back in my element, underwater, photographing species that are so outlandish that they could have been extras at the Star Wars cantina. Pink dolphins use sonar to navigate flooded woodlands. The arapaima, an armored fish that weighs as much as a silverback gorilla, leaps from the water like a marlin. Electric eels, like swimming batteries, deliver 600-volt shocks powerful enough to kill a human. Black freshwater stingrays with bright yellow spots rest in the leaf litter of drowned forest floors.

My National Geographic Explorer collaborators include some of the Amazon’s most accomplished scientists: Fernando Trujillo, João Campos-Silva, Ruthmery Pillco Huarcaya, Angelo Bernardino, Thiago Silva, Baker Perry, and Hinsby Cadillo-Quiroz. They’re doing groundbreaking work on pink dolphins, arapaimas, spectacled bears, mangroves, flooded forests, climate change, and mercury pollution. Next year, National Geographic will devote an entire issue of the magazine to the Amazon, featuring my photographs and their studies.

Finding Inspiration From the Earliest Amazon Artists

Famed 19th-century naturalists like Henry Walter Bates, Alfred Russel Wallace, and Alexander von Humboldt produced beautiful illustrations of what they had seen on their explorations in the Amazon River Basin. But I came to Chiribiquete to see the work of the first people in the Amazon to depict fauna and flora, specifically the aquatic animals I hope to photograph. On sheer rock walls, they painted fish, turtles, caimans, and other life-forms.

Over our five days in Chiribiquete, we saw hundreds of pictographs. The “Hojarasca” (“Fallen Leaves”) panel, with jaguars hunting pacas among piranhas, spoke to me the most. The way they’re painted on an overhang evoked the sense that I was underwater looking up as the scene played out above.

Lowland tapirs eat aquatic plants and walk underwater as hippos do. Juveniles have stripes and spots that help camouflage them. This one is a rescued orphan that will be rewilded. In between feedings, it’s free to explore forests and scrublands on a cattle ranch in the Serranía de la Macarena.

Castaño-Uribe thinks these paintings were likely made by shamans and played a role in religious rituals. Through the ingestion of sacred plants, Baniwa shamans believe they can transform into jaguars and talk with spirits. To the Tikuna, pink dolphins are sacred, feature in their dances, and are said to dwell in malocas, or longhouses, at the bottom of the river. Anacondas are often considered the creators of the universe, and a Desano legend tells of a giant snake that ascended the Amazon carrying the ancestors of all mankind on its back.

The shamans likely painted to communicate with supernatural beings to ensure balance between humans and the rest of nature. I tell stories because our relationship with Earth’s biodiversity urgently needs recalibration. The Amazon’s aquatic world is threatened by dams, mining, overfishing, pollution, and climate change. Gazing at these vivid, timeless pictures, I feel deeply connected to these artists and their paintings. I realize we are telling similar stories, and I hope my images stand the test of time even a fraction as well as theirs.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Okay so I’m a disabled bisexual mixed Indigenous woman and I am in a position where I thankfully don’t need help, but many Indigenous people do. Remember what actually happened today. Remember whose land you live on.

Thousand Currents (Asociación para la Naturaleza y el Desarrollo Sostenible (ANDES) / Association for Nature and Sustainable Development)

Indian Residential Schools Survivors Society

True North Aid

Warrior Women Project

Māori Indigenous Education Fund

Quileute Move to Higher Ground Project

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami

POR LA SALUD DE LOS PUEBLOS INDÍGENAS AMAZÓNICOS/For the health of indigenous amazon villages

Navajo Nation Department of Health

Ojibwe Cultural Foundation

716 notes

·

View notes

Text

L’ECUADOR RESTITUISCE LE TERRE AI POPOLI INDIGENI

L’Ecuador ha riconosciuto una nuova riserva nella foresta pluviale amazzonica, restituendola alle tribù indigene che la hanno storicamente abitata e che erano minacciate dall’attività di estrazione mineraria e dall’allevamento di bestiame.

La Riserva Tarímiat Pujutaí Nuṉka diventa una delle più grandi della regione, coprendo 1.237.395 ettari di terre andine e amazzoniche nella provincia di Morona Santiago dell’Ecuador orientale, dove numerose comunità tribali hanno per anni resistito con difficoltà alla deforestazione. “Questa è un’iniziativa che non solo ci consentirà di preservare, ma anche di godere delle nostre foreste e del clima, per offrire al mondo un ambiente sano”, ha affermato il governatore di Morona Santiago, Rafael Antuni.

L’area ospita foreste pluviali, altipiani di arenaria, pianure e foreste alluvionali con migliaia di specie di uccelli oltre a grandi mammiferi come giaguari, tapiri e orsi. La provincia conta quasi 200.000 abitanti, la maggior parte dei quali membri delle comunità indigene Shuar e Achuar.

Il processo di pianificazione e creazione della riserva è stato realizzato in modo unico per l’Ecuador. Una lunga fase di preparazione e di consultazione pre-legislativa ha visto lo svolgimento di centinaia di incontri e di confronti con i quattro gruppi indigeni, inclusa la partecipazione di quasi 900 residenti, con il fine di includere le loro diverse visioni della riserva e rendere il processo più partecipativo possibile. Le comunità che custodiscono queste foreste da migliaia di anni potranno in questo modo continuare a conservare la biodiversità e arrestare la deforestazione.

___________________

Fonte: Andes Amazon Fund; immagine Jeff Stapleton

VERIFICATO ALLA FONTE | Guarda il protocollo di Fact checking delle notizie di Mezzopieno

BUONE NOTIZIE CAMBIANO IL MONDO | Firma la petizione per avere più informazione positiva in giornali e telegiornali

Se trovi utile il nostro lavoro e credi nel principio del giornalismo costruttivo non-profit | sostieni Mezzopieno

6 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Timpana - Gwandena - lush folktronica, with the folk being from the Andean and Amazonian regions of South America

TIMPANA creates her own sound based on native vocal techniques from Bolivia and the world.

Since 2009 with her debut album Alma Perdida she has come with a world music influence that now with Gwandena she experiments even more with electronic elements and sounds, indigenous instruments, native songs in Spanish, Quechua and Guarani, with a strong Afro Andean Amazonian influence.

On Gwandena, the Bolivian artist TIMPANA maps out a metaphysical journey across her home country, and through various states of being. Indigenous and African instrumentation meet electronic drums and synths on an album that veers between moments of slowly-revealing transcendence and urgent, rhythmic cries as the world appears different to how we ever imagined it. TIMPANA began as a duo, but has been the solo project of artist, performer and musician Alejandra Lanza for over 10 years. Gwandena is the first solo album in this iteration, and sees Lanza working with fellow Bolivian producer Chuntu, as well as fellow masters of Afro-Andean wind and percussion instruments. Together they have created a work that is complex in both its musical construction – being that it references and merges rhythms and cadences from the Andes, Amazon and Afro-Latin traditions – and in its narrative. Gwandena tells the story of Talina, a young girl on a journey of self-knowledge. She is guided by a hummingbird called Jovi and must come face-to-face with herself, but not in a way she ever planned.

TIMPANA and Gwandena’s producer, Chuntu, were both featured in Bandcamp’s spotlight on Bolivian music earlier this year as artists pivotal in contributing to and promoting “Bolivia’s rich artistic universe”, and Gwandena is their finest statement of intent yet, an album that draws from Bolivia’s myriad traditions and belief systems, with a vocal performance that is sure to earn Lanza plaudits as one of Latin America’s finest singers and interpreters. It’s also an album that can hold its own against the best folktronica and other contemporary iterations of pan-Latin identity being made right now. Ale Lanza: vocals, percussion and samplers Chuntu: keyboards, synths and samplers Luciel Izumi: ronroco on “Jovi”; charango on “Gwandena” and “Pájaro”. Cucó Pachá Kutí: toyos, quenas, quenachos and other wind instruments, and percussion, on “Jovi”, “Gwandena”, “Pájaro” and “Espejo”. Miguel Crespo: wankara and caja on “Jovi”; bombo on “Espejo”. Amado Espinoza: djembé and seed shaker on “Estrella Brillosa”, “Gwandena” and “Amayu”. TIMPANA is a founding member of Primavera Anónima, a social impact-driven creative collective founded digitally in Shanghai. Current projects raise funds for digital health projects in El Alto, Bolivia.

#Timpana#bolivia#folktronica#folk#electronic#female vocal#ale lanza#2022#sounds and colours#andean music

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

Excerpt from this story from the New York Times:

Jeff Bezos, the Amazon founder and one of the world’s richest men, announced plans on Monday for $1 billion in conservation spending in places like the Congo Basin, the Andes and tropical parts of the Pacific Ocean.

The announcement was the latest step in his largest philanthropic effort, the Bezos Earth Fund, to which he pledged $10 billion last year. “By coming together with the right focus and ingenuity, we can have both the benefits of our modern lives and a thriving natural world,” Mr. Bezos said on Monday at an event in New York.

The money will be used “to create, expand, manage and monitor protected and conserved areas,” according to a news release from the fund, which also introduced a website on Monday.

The initiative is intended to support an international push to safeguard at least 30 percent of Earth’s lands and waters by 2030, known as 30x30. The plan, led by Britain, Costa Rica and France, is intended to help tackle a global biodiversity crisis that puts a million species of plants and animals at risk of extinction. While climate change is part of the problem, activities like farming and fishing have been even bigger drivers of biodiversity loss. The 30x30 plan would try to slow that by protecting intact natural areas like old-growth forests and wetlands, which not only nurture biodiversity but also store carbon and filter water.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

From the article:

Andes Amazon Fund celebrates the creation of the Arroyo Guarichona Municipal Protected Area in the department of Beni, Bolivia. Home to floodplains, tributaries, expansive grasslands, vast forests, and evidence of pre-Columbian societies, Arroyo Guarichona safeguards both the cultural and ecological heritage of Northern Bolivia. The new area covers 492,815 acres (199,435 ha), and is home to Indigenous peoples, farmers, and local communities that pushed for the creation of the conservation area.

#conservation#indigenous conservation#endangered species#environment#hope#hopepunk#good news#biodiversity#ecology#ecological grief#ecoanxiety#grassland conservation#wildlife#land conservation#Amazon conservation#Bolivia

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

Where are the Seven Gates of Hell Located?

Many over the past few centuries tell that the Seven Gates of Hell or each located on one of each of the continents. The seven traditional continents are (from largest in size to smallest): Asia, Africa, North America, South America, Antarctica, Europe, and Australia. That Means That there is one Gate of Hell for each Continent respectively.

But over the years many strange tales have arisen concerning their specific location and what happens to you if you dare to find them. Truth or fiction the tales often grow with each telling. Many forums, blogs and message boards are filled with the evil's and misconceptions of what a doorway to hell is really like and where it might be found.

The Gate to Hell in Africa many say is located in Egypt. The exact locations said by many would be gate searchers is thought to be located directly under the left paw of the great Sphinx. This Horrific Gate is known to be Called the Gate to The Underworld or After Life, the great hall of records. To this date no one has entered it or found it.

It is situated near the small town of Darvaz. The story of this place lasts already for 35 years. Once the geologists were drilling for gas. Then suddenly during the drilling they have found an underground cavern, it was so big that all the drilling site with all the equipment and camps got deep deep under the ground. None dared to go down there because the cavern was filled with gas. So they ignited it so that no poisonous gas could come out of the hole, and since then, it's burning, already for 35 years without any pause. Nobody knows how many tons of excellent gas has been burned for all those years but it just seems to be infinite there.

The Gate of hell in Asia is located in Aokigahara, also known as the Sea of Trees, is a forest that lies at the base of Mount Fuji in Japan. The caverns found in this forest are rocky and ice-covered annually. It has been claimed by local residents and visitors that the woods are host to a great amount of paranormal phenomena. It is an old ancient forest reportedly haunted by many urban historical legends of strange beasts, monsters, ghosts, and goblins, which add to its serious and sinister reputation.

Some in the world will tell you it is one of the actual seven gates to hell! The location is said to haunted by demons as well as ghosts. These demons or those that make you take your life. I found these forest to be very disturbing and in my mind what a hideous place of beauty for a infernal hole to hell to be in.

Near or under the Great Temple Mount In Israel. One if the possible gates to hell is called Satan's Front Door. Some scholars will argue that this door was once in Rome and Moved to the Holy land when Israel Became a State 14 May 1948. It is Believed it took 2 thousand legions of demons and Devil's to move the great gate because it is the most powerful and strongest doors that Satan has for gaining souls. When it Was Rome their were two gates of hell on the continent and it is believe that the great Caesar's had it originally moved there when they found it in The Holy Land originally.

In 1867, a team from the Royal Engineers, led by Lieutenant Charles Warren (later the London police commissioner of Jack the Ripper fame) and financed by the Palestine Exploration Fund (P.E.F.), discovered a series of tunnels beneath Jerusalem and the Temple Mount, some of which were directly underneath the headquarters of the Knights Templar.

Various small artifacts were found which indicated that Templar's had used some of the tunnels, though it is unclear who exactly first dug them. Some of the ruins which Warren discovered came from centuries earlier, and other tunnels which his team discovered had evidently been used for a water system, as they led to a series of cisterns.

The Gate to Hell is by many thought to be located in Europe. And it is hidden in Pere Lachaise Paris Cemetery Paris. It is said to be a great grand gate with very notable significance. this gate is said to be the one that all great heads of state must enter through when they die. And through this gate World Leaders must be judged by the Devil first and not God. Many tales tell of vampire-like entities guarding the entrance. Some believe that the Underground catacombs of Paris are the true gates but many beg to differ.

Some searchers believe that the actual Hellfire Caves Buckinghamshire, England is a indirect gate to Hell. Some call it a side door to the dark underworld of Satan.

West Wycombe Caves, also known as Hellfire Caves, located in the Chiltern Hills, Buckinghamshire, England, are most well known as a meeting place for members of The Hellfire Club. The caves were extended by Sir Francis Dashwood (later Lord le Despencer) between 1748–1752. They provided work for unemployed farm workers following a succession of harvest failures, and lie close to Dashwood's country house, West Wycombe Park (now owned by the National Trust). The chalk mines that were extended to form the caves had existed near High Wycombe for a considerable time. The mines are said to have a prehistoric origin, and were presumably created to extract the flint found in the chalk to make hand tools. Locally, flint is used as a building material.

The entrance to the caves is built from flint, and St Lawrence's church, above the Inner Temple, is also built using flint. Due to the extensive alterations made by Dashwood, all evidence of the caves' earlier history seem to have been destroyed. The underground "rooms" are named, from the Entrance Hall, through the Circle, Franklin's Cave (named after Benjamin Franklin, a friend of Dashwood who stayed with him at West Wycombe), the Banqueting Hall, the Triangle, to the Miner's Cave; finally, across a subterranean river named the Styx, lies the final cave, the Inner Temple. An alternative viewpoint was advanced by Daniel P Mannix in his book about The Hellfire Club. This theory suggests that the caves had been deliberately created by Dashwood according to a sexual design.The design begins at the 'womb' of the Banqueting Hall, leading to rebirth through the female triangle, followed by baptism in the River Styx and the pleasures thereafter of the Inner Temple.

This theory is not mentioned in National Trust literature and is allegedly refuted by the Dashwood family.The flint mining theory is also questionable because the Chiltern Hills flint bed overlays the chalk escarpment and does not have to be mined except by means of small open flint dells of which there are many on the area.The caves were refurbished and made suitable for visitors during the 1950s by the late Sir Francis Dashwood, 11th Baronet.

They are now open as a tourist attraction, with life-sized waxwork figures in period costume illustrating the life of the caves in the 18th century. The caves have attracted over 2 million visitors since 1951.

The Gate to Hell in South America is located in Rio de Janeiro. Harbour of Rio de Janeiro is one of the 7 natural wonders of the world. The actual open gate yo hell is said to be near where the world famous "Christ the Redeemer" Statue stands. Some say the entrance is in an underwater cave or hidden near the top of Corcovado Peak. Locals believe that during the festival of Carnival the gate swings open to trap those that or unaware of it's location who deserve to be taken to hell alive.

The gate has also been thought to be located at Machu Picchu, Iguazu Falls, Angel Falls, the Nazca lines are thought by some to point the way, Galapagos, along the Amazon which is thought to originate or flow into the river Styx, Patagonia, Andes .

The North American Gate is said to be located at or very near the Tomb Of the great Voodoo - Hoodoo Queen, Marie Laveau. Many say it is the doorway to the home of the eternally tortured and living dead. Many old tales tell of strange monsters issuing from the infernal gates. Vampires zombies and a host of Ghede and strange half dead beings.

#Where are the Seven Gates of Hell Located?#haunted locations#paranormal#ghost and hauntings#ghost and spirits#haunted salem#myhauntedsalem

41 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gold Pectoral with Zoomorphic Face, Chavín, -600, Art Institute of Chicago: Arts of the Americas

The archaeological site of Chavín de Huántar, high in a valley in the northern Andes of Peru, was a seat of economic, political, and religious power, giving rise to art and symbolic imagery that deeply affected the Andean world between 900 and 200 B.c.1 The rulers of Chavín brought about a cultural synthesis, adapting architectural and sculptural forms that had been associated with ruler-ship by the urban coastal societies of Peru for at least a thousand years. Artists created a new imagery, deriving forms from both the human figure and dominant predators—caymans, harpy eagles, jaguars, and pumas, some of them native to the Amazon forests east of the Andes mountains. These animal and anthropomorphic icons were often combined in a fearsome visual vocabulary. Expressed in imposing architectural reliefs, monumental three-dimensional sculptures, textile designs, and splendid ritual attire and portable objects, this symbolic imagery was emblematic of Chavín priestly rulers and the warrior aristocracy, affirming their spiritual connections with the domain of animal powers and the deified forces and phenomena of nature. Chavín art was a distinctly Andean expression of the cosmological and religious worldview that once held sway throughout the Americas.This pectoral is a rare example of the attire worn by a Chavín leader on ceremonial occasions. Metallurgy was well developed in the Andes; to make this object, an artisan would first have cut a hammered sheet of gold and copper alloy into a rectangular shape, with four "arms" extending at the corners in a cruciform pattern; then he used a sharp instrument to engrave the design of the mask and the ornamental curls and linear appendages; the sculptural low relief was achieved by hammering the metal over a carved wooden mold. The menacing face with its zigzag eyebrows, bulbous nose, and fanged, grinning mouth is an iconic type found on gold work, stone monuments, textiles, and ceramic vessels. Many objects of Chavín gold work are found in broken condition: the deliberate damage done to this piece was undoubtedly inflicted when it was ritually "killed" for burial and sent to accompany its wearer on his journey to the world of the ancestor spirits. Joanne M. and Clarence E. Spanjer and Curator’s Discretionary funds Size: 27.9 × 25.4 cm (11 × 10 in.) Medium: Gold

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/184361/

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Declining biodiversity in wild Amazon fisheries threatens human diet

https://sciencespies.com/nature/declining-biodiversity-in-wild-amazon-fisheries-threatens-human-diet/

Declining biodiversity in wild Amazon fisheries threatens human diet

A new study of dozens of wild fish species commonly consumed in the Peruvian Amazon says that people there could suffer major nutritional shortages if ongoing losses in fish biodiversity continue. Furthermore, the increasing use of aquaculture and other substitutes may not compensate. The research has implications far beyond the Amazon, since the diversity and abundance of wild-harvested foods is declining in rivers and lakes globally, as well as on land. Some 2 billion people globally depend on non-cultivated foods; inland fisheries alone employ some 60 million people, and provide the primary source of protein for some 200 million. The study appears this week in the journal Science Advances.

The authors studied the vast, rural Loreto department of the Peruvian Amazon, where most of the 800,000 inhabitants eat fish at least once a day, or an average of about 52 kilograms (115 pounds) per year. This is their primary source not only of protein, but fatty acids and essential trace minerals including iron, zinc and calcium. Unfortunately, it is not enough; a quarter of all children are malnourished or stunted, and more than a fifth of women of child-bearing age are iron deficient.

Threats to Amazon fisheries, long a mainstay for both indigenous people and modern development, are legion: new hydropower dams that pen in big migratory fish (some travel thousands of miles from Andes headwaters to the Atlantic estuary and back); soil erosion into rivers from deforestation; toxic runoff from gold mines; and over-exploitation by fishermen themselves, who are struggling to feed fast-growing populations. In Loreto, catch tonnages are stagnating; some large migratory species are already on the decline, and others may be on the way. It is the same elsewhere; globally, a third of freshwater fish species are threatened with extinction, and 80 are already known to be extinct, according to the World Wildlife Fund.

Different species of animals and plants contain different ratios of nutrients, so biodiversity is key to adequate human nutrition, say the researchers. “If fish decline, the quality of the diet will decline,” said the study’s senior coauthor, Shahid Naeem, director of Columbia University’s Earth Institute Center for Environmental Sustainability. “Things are definitely declining now, and they could be on the path to crashing eventually.”

To study the region’s fish, the study’s lead author, then-Columbia PhD. student Sebastian Heilpern, made numerous shopping trips to the bustling Belén retail market in the provincial capital of Iquitos. He also visited the city’s Amazon River docks, where wholesale commerce begins at 3:30 in the morning. He and another student bought multiple specimens of as many different species as they could find, and ended up with 56 of the region’s 60-some main food species. These included modest-size scale fish known locally as ractacara and yulilla; saucer-shaped palometa (related to piranha); and giant catfish extending six feet or more. (The researchers settled for chunks of the biggest ones.)

The fish were flown on ice to a government lab in Lima, where each species was analyzed for protein, fatty acids and trace minerals. The researchers then plotted the nutritional value of each species against its probability of surviving various kinds of ongoing environmental degradation. From this, they drew up multiple scenarios of how people’s future diet would be affected as various species dropped out of the mix.

advertisement

Overall, the biomass of fish caught has remained stable in recent years. However, large migratory species, the most vulnerable to human activities, comprise a shrinking portion, and as they disappear, they are being replaced by smaller local species. Most fish contain about the same amount of protein, so this has not affected the protein supply. And, the researchers found, many smaller fish in fact contain higher levels of omega-3 fatty acids, so their takeover may actually increase those supplies. On the other hand, as species compositions lean more to smaller fish, supplies of iron, zinc are already going down, and will continue to decline, they say.

“Like any other complex system, you see a tradeoff,” said Heilpern. “Some things are going up while other things are going down. But that only lasts up to a point.” Exactly which species will fill the gaps left when others decline is difficult to predict — but the researchers project that the overall nutritional value of the catch will nosedive around the point where 40 of the 60 food species become scarce or extinct. “You have a tipping point, where the species that remain can be really lousy,” said Heilpern.

One potential solution: in many places around the world where wild foods including fish and bush meat (such as monkeys and lizards) are declining, people are turning increasingly to farm-raised chicken and aquaculture — a trend encouraged by the World Bank and other powerful organizations. This is increasingly the case in Loreto. But in a separate study published in March, Heilpern, Naeem and their colleagues show that this, too, is undermining human nutrition.

The researchers observed that chicken production in the region grew by about three quarters from 2010 to 2016, and aquaculture nearly doubled. But in analyzing the farmed animals’ nutritional values, they found that they typically offer poorer nutrition than a diverse mix of wild fish. In particular, the move to chicken and aquaculture will probably exacerbate the region’s already serious iron deficiencies, and limit supplies of essential fatty acids, they say. “Because no single species can offer all key nutrients, a diversity of species is needed to sustain nutritionally adequate diets,” they write.

Besides this, chicken farming and aquaculture exert far more pressure on the environment than fishing. In addition to encouraging clearing of forests to produce feed for the animals, animal farming produces more more greenhouse gases, and introduces fertilizers and other pollutants into nearby waters, says Heilpern.

“Inland fish are fundamental for nutrition in many low-income and food-deficit countries, and of course landlocked countries,” said John Valbo Jørgensen, a Rome-based expert on inland fisheries with the UN Food and Agriculture Organization. “Many significant inland fisheries, including those of Peru, take place in remote areas with poor infrastructure and limited inputs. It will not be feasible to replace those fisheries with farmed animals including fish.”

Heilpern is now working with the Wildlife Conservation Society to produce an illustrated guide to the region’s fish, including their nutritional values, in hopes of promoting a better understanding of their value among both fishermen and consumers.

The other authors of the new study are Ruth deFries and Maria Uriarte of the Earth Institute; and Kathryn Fiorella, Alexander Flecker and Suresh Sethi of Cornell University.

#Nature

1 note

·

View note

Text

Quantitative Ecologist Andes Amazon Fund Join the team studying how Amazonian biodiversity is responding to climate change See the full job description on jobRxiv: https://jobrxiv.org/job/andes-amazon-fund-27778-quantitative-ecologist/?feed_id=83981 #biodiversity #Climate_Change #statistics #ScienceJobs #hiring #research

0 notes

Text

Climate change: six positive news stories from 2019

by Heather Alberro, Dénes Csala, Hannah Cloke, Marc Hudson, Mark Maslin, and Richard Hodgkins

Hydroelectric power has helped Costa Rica ditch fossil fuels. John E Anderson / shutterstock

The climate breakdown continues. Over the past year, The Conversation has covered fires in the Amazon, melting glaciers in the Andes and Greenland, record CO₂ emissions, and temperatures so hot they’re pushing the human body to its thermal limits. Even the big UN climate talks were largely disappointing.

But climate researchers have not given up hope. We asked a few Conversation authors to highlight some more positive stories from 2019.

Costa Rica offers us a viable climate future

Heather Alberro, associate lecturer in political ecology, Nottingham Trent University

After decades of climate talks, including the recent COP25 in Madrid, emissions have only continued to rise. Indeed, a recent UN report noted that a fivefold increase in current national climate change mitigation efforts would be needed to meet the 1.5℃ limit on warming by 2030. With the radical transformations needed in our global transport, housing, agricultural and energy systems in order to help mitigate looming climate and ecological breakdown, it can be easy to lose hope.

However, countries like Costa Rica offer us promising examples of the “possible”. The Central American nation has implemented a refreshingly ambitious plan to completely decarbonise its economy by 2050. In the lead-up to this, last year with its economy still growing at 3%, Costa Rica was able to derive 98% of its electricity from renewable sources. Such an example demonstrates that with sufficient political will, it is possible to meet the daunting challenges ahead.

Financial investors are cooling on fossil fuels

Richard Hodgkins, senior lecturer in physical geography, Loughborough University

Movements such as 350.org have long argued for fossil fuel divestment, but they have recently been joined by institutional investors such as Climate Action 100+, which is using the influence of its US$35 trillion of managed funds, arguing that minimising climate breakdown risks and maximising renewables’ growth opportunities are a fiduciary duty.

Moody’s credit-rating agency recently flagged ExxonMobil for falling revenues despite rising expenditure, noting: “The negative outlook also reflects the emerging threat to oil and gas companies’ profitability […] from growing efforts by many nations to mitigate the impacts of climate change through tax and regulatory policies.”

An oil pipeline in northern Alaska. saraporn / shutterstock

A more adverse financial environment for fossil fuel companies reduces the likelihood of new development in business frontier regions such as the Arctic, and indeed, major investment bank Goldman Sachs has declared that it “will decline any financing transaction that directly supports new upstream Arctic oil exploration or development”.

We are getting much better at forecasting disaster

Hannah Cloke, professor of hydrology, University of Reading

In March and April 2019, two enormous tropical cyclones hit the south-east coast of Africa, killing more than 600 people and leaving nearly 2 million people in desperate need of emergency aid.

There isn’t much that is positive about that, and there’s nothing new about cyclones. But this time scientists were able to provide the first early warning of the impending flood disaster by linking together accurate medium-range forecasts of the cyclone with the best ever simulations of flood risk. This meant that the UK government, for example, set about working with aid agencies in the region to start delivering emergency supplies to the area that would flood, all before Cyclone Kenneth had even gathered pace in the Indian Ocean.

We know that the risk of dangerous floods is increasing as the climate continues to change. Even with ambitious action to reduce greenhouse gases, we must deal with the impact of a warmer more chaotic world. We will have to continue using the best available science to prepare ourselves for whatever is likely to come over the horizon.

Local authorities across the world are declaring a ‘climate emergency’

Marc Hudson, researcher in sustainable consumption, University of Manchester

More than 1,200 local authorities around the world declared a “climate emergency” in 2019. I think there are two obvious dangers: first, it invites authoritarian responses (stop breeding! Stop criticising our plans for geoengineering!). And second, an “emergency” declaration may simply be a greenwash followed by business-as-usual.

In Manchester, where I live and research, the City Council is greenwashing. A nice declaration in July was followed by more flights for staff (to places just a few hours away by train), and further car parks and roads. The deadline for a “bring zero-carbon date forward?” report has been ignored.

But these civic declarations have also kicked off a wave of civic activism, as campaigners have found city councils easier to hold to account than national governments. I’m part of an activist group called “Climate Emergency Manchester” – we inform citizens and lobby councillors. We’ve assessed progress so far, based on Freedom of Information Act requests, and produced a “what could be done?” report. As the council falls further behind on its promises, we will be stepping up our activity, trying to pressure it to do the right thing.

Radical climate policy goes mainstream

Dénes Csala, lecturer in energy system dynamics, Lancaster University

Before the 2019 UK general election, I compared the Conservative and Labour election manifestos, from a climate and energy perspective. Although the party with the clearly weaker plan won eventually, I am still stubborn enough to be hopeful with regard to the future of political action on climate change.

For the first time, in a major economy, a leading party’s manifesto had at its core climate action, transport electrification and full energy system decarbonisation, all on a timescale compatible with IPCC directives to avoid catastrophic climate change. This means the discussion that has been cooking at the highest levels since the 2015 Paris Agreement has started to boil down into tangible policies.

Young people are on the march!

Mark Maslin, professor of earth system science, UCL

In 2019, public awareness of climate change rose sharply, driven by the schools strikes, Extinction Rebellion, high impact IPCC reports, improved media coverage, a BBC One climate change documentary and the UK and other governments declaring a climate emergency. Two recent polls suggest that over 75% of Americans accept humans have caused climate change.

Empowerment of the first truly globalised generation has catalysed this new urgency. Young people can access knowledge at the click of a button. They know climate change science is real and see through the deniers’ lies because this generation does not access traditional media – in fact, they bypass it.

The awareness and concern regarding climate change will continue to grow. Next year will be an even bigger year as the UK will chair the UN climate change negotiations in Glasgow – and expectation are running high.

About The Authors:

Heather Alberro is an Associate Lecturer/PhD Candidate in Political Ecology at Nottingham Trent University; Dénes Csala is a Lecturer in Energy Storage Systems Dynamics at Lancaster University; Hannah Cloke is Professor of Hydrology at the University of Reading; Marc Hudson is a Researcher in Sustainable Consumption at the University of Manchester; Mark Maslin is Professor of Earth System Science at UCL, and Richard Hodgkins is Senior Lecturer in Physical Geography at Loughborough University

This article is republished from our content partners over at The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

18 notes

·

View notes