#and will ever come for the ankles of anyone who slanders my baby boys

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

How I imagine a standoff between FengLian and HuaLian shippers would look like:

#i appreciate that there is none though#to my knowledge at least#besides that one fic#i appreciate this fandom being peaceful#(mostly)#and will ever come for the ankles of anyone who slanders my baby boys#but anyone is free to ship whoever they want#tgcf#hualian#fenglian#hua cheng#feng xin#tian guan ci fu#tgcf thoughts#tgcf donghua#tgcf season 2#heaven officials blessing#天官赐福#tgcf s2#tgcf fandom

171 notes

·

View notes

Text

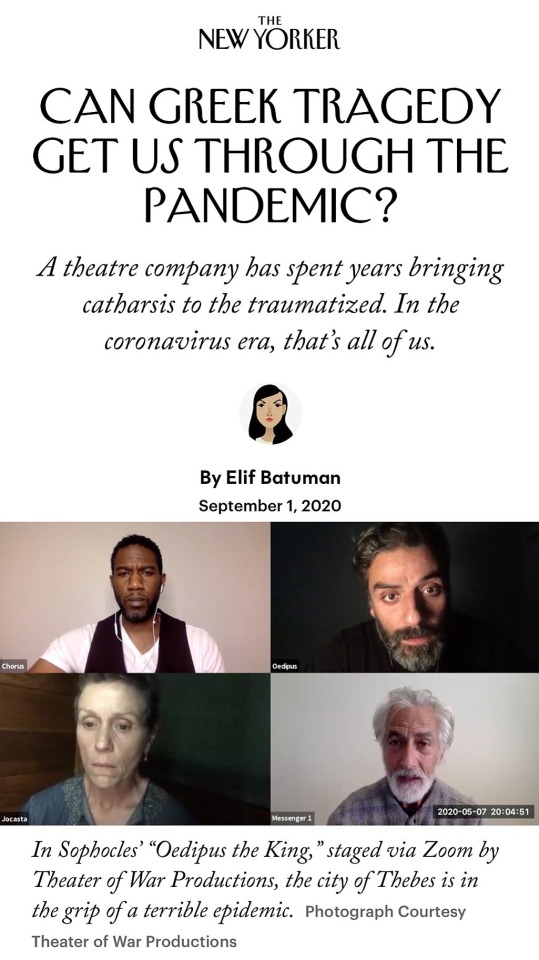

Fantastic (but long) article about Theater of War’s recent productions, including Oedipus the King and Antigone in Ferguson, featuring Oscar Isaac. The following are excerpts. The full article is viewable via the source link below:

Excerpt:

“Children of Thebes, why are you here?” Oscar Isaac asked. His face filled the monitor on my dining table. (It was my partner’s turn to use the desk.) We were a couple of months into lockdown, just past seven in the evening, and a few straggling cheers for essential workers came in through the window. Isaac was looking smoldery with a quarantine beard, a gold chain, an Airpod, and a black T-shirt. His display name was set to “Oedipus.”

Isaac was one of several famous actors performing Sophocles’ “Oedipus the King” from their homes, in the first virtual performance by Theater of War Productions: a group that got its start in 2008, staging Sophocles’ “Ajax” and “Philoctetes” for U.S. military audiences and, beginning in 2009, on military installations around the world, including in Kuwait, Qatar, and Guantánamo Bay, with a focus on combat trauma. After each dramatic reading, a panel made up of people in active service, veterans, military spouses, and/or psychiatrists would describe how the play resonated with their experiences of war, before opening up the discussion to the audience. Since its founding, Theater of War Productions has addressed different kinds of trauma. It has produced Euripides’ “The Bacchae” in rural communities affected by the opioid crisis, “The Madness of Heracles” in neighborhoods afflicted by gun violence and gang wars, and Aeschylus’ “Prometheus Bound” in prisons. “Antigone in Ferguson,” which focusses on crises between communities and law enforcement, was motivated by an analogy between Oedipus’ son’s unburied body and that of Michael Brown, left on the street for roughly four hours after Brown was killed by police; it was originally performed at Michael Brown’s high school.

Now, with trauma roving the globe more contagiously than ever, Theater of War Productions had traded its site-specific approach for Zoom. The app was configured in a way I hadn’t seen before. There were no buttons to change between gallery and speaker view, which alternated seemingly by themselves. You were in a “meeting,” but one you were powerless to control, proceeding by itself, with the inexorability of fate. There was no way to view the other audience members, and not even the group’s founder and director, Bryan Doerries, knew how numerous they were. Later, Zoom told him that it had been fifteen thousand. This is roughly the seating capacity of the theatre of Dionysus, where “Oedipus the King” is believed to have premièred, around 429 B.C. Those viewers, like us, were in the middle of a pandemic: in their case, the Plague of Athens.

The original audience would have known Oedipus’ story from Greek mythology: how an oracle had predicted that Laius, the king of Thebes, would be killed by his own son, who would then sleep with his mother; how the queen, Jocasta, gave birth to a boy, and Laius pierced and bound the child’s ankles, and ordered a shepherd to leave him on a mountainside. The shepherd took pity on the maimed baby, Oedipus (“swollen foot”), and gave him to a Corinthian servant, who handed him off to the king and queen of Corinth, who raised him as their son. Years later, Oedipus killed Laius at a crossroads, without knowing who he was. Then he saved Thebes from a Sphinx, became the king of Thebes, had four children with Jocasta, and lived happily for many years.

That’s where Sophocles picks up the story. Everyone would have known where things were headed—the truth would come out, and Oedipus would blind himself—but not how they would get there. How Sophocles got there was by drawing on contemporary events, on something that was in everyone’s mind, though it doesn’t appear in the original myth: a plague.

In the opening scene, Thebes is in the grip of a terrible epidemic. Oedipus’ subjects come to the palace, imploring him to save the city, describing the scene of pestilence and panic, the screaming and the corpses in the street. Something about the way Isaac voiced Oedipus’ response—“Children. I am sorry. I know”—made me feel a kind of longing. It was a degree of compassion conspicuous by its absence in the current Administration. I never think of myself as someone who wants or needs “leadership,” yet I found myself thinking, We would be better off with Oedipus. “I would be a weak leader if I did not follow the gods’ orders,” Isaac continued, subverting the masculine norm of never asking for advice. He had already sent for the best information out there, from the Delphic Oracle.

Soon, Oedipus’ brother-in-law, Creon—John Turturro, in a book-lined study—was doing his best to soft-pedal some weird news from Delphi. Apparently, the oracle said that the plague wouldn’t end until the people of Thebes expelled Laius’ killer: a person who was somehow still in the city, even though Laius had died many years earlier on an out-of-town trip. Oedipus called in the blind prophet, Tiresias, played by Jeffrey Wright, whose eyes were invisible behind a circular glare in his eyeglasses.

Reading “Oedipus” in the past, I had always been exasperated by Tiresias, by his cryptic lamentations—“I will never reveal the riddles within me, or the evil in you”—and the way he seemed incapable of transmitting useful information. Spoken by a Black actor in America in 2020, the line made a sickening kind of sense. How do you tell the voice of power that the problem is in him, really baked in there, going back generations? “Feel free to spew all of your vitriol and rage in my direction,” Tiresias said, like someone who knew he was in for a tweetstorm.

Oedipus accused Tiresias of treachery, calling out his disability. He cast suspicion on foreigners, and touted his own “wealth, power, unsurpassed skill.” He decried fake news: “It’s all a scam—you know nothing about interpreting birds.” He elaborated a deep-state scenario: Creon had “hatched a secret plan to expel me from office,” eliciting slanderous prophecies from supposedly disinterested agencies. It was, in short, a coup, designed to subvert the democratic will of the people of Thebes.

Frances McDormand appeared next, in the role of Jocasta. Wearing no visible makeup, speaking from what looked like a cabin somewhere with wood-panelled walls, she resembled the ghost of some frontierswoman. I realized, when I saw her, that I had never tried to picture Jocasta: not her appearance, or her attitude. What was her deal? How had she felt about Laius maiming their baby? How had she felt about being offered as a bride to whomever defeated the Sphinx? What did she think of Oedipus when she met him? Did it never seem weird to her that he was her son’s age, and had horrible scars on his ankles? How did they get along, those two?

When you’re reading the play, you don’t have to answer such questions. You can entertain multiple possibilities without settling on one. But actors have to make decisions and stick to them. One decision that had been made in this case: Oedipus really liked her. “Since I have more respect for you, my dear, than anyone else in the world,” Isaac said, with such warmth in “my dear.” I was reminded of the fact that Euripides wrote a version of “Oedipus”—lost to posterity, like the majority of Greek tragedies—that some scholars suggest foregrounds the loving relationshipbetween Oedipus and Jocasta.

Jocasta’s immediate task was to defuse the potentially murderous argument between her husband and her brother. She took one of the few rhetorical angles available to a woman: why, such grown men ought to be ashamed of themselves, carrying on so when there was a plague going on. And yet, listening to the lines that McDormand chose to emphasize, it was clear that, in the guise of adult rationality and spreading peace, what she was actually doing was silencing and trivializing. “Come inside,” she said, “and we’ll settle this thing in private. And both of you quit making something out of nothing.” It was the voice of denial, and, through the play, you could hear it spread from character to character.

By this point in the performance, I found myself spinning into a kind of cognitive overdrive, toggling between the text and the performance, between the historical context, the current context, and the “universal” themes. No matter how many times you see it pulled off, the magic trick is always a surprise: how a text that is hundreds or thousands of years old turns out to be about the thing that’s happening to you, however modern and unprecedented you thought it was.

Excerpt:

The riddle of the Sphinx plays out in the plot of “Oedipus,” particularly in a scene near the end where the truth finally comes out. Two key figures from Oedipus’ infancy are brought in for questioning: the Theban shepherd, who was supposed to kill baby Oedipus but didn’t; and the Corinthian messenger to whom he handed off the maimed child. The Theban shepherd is walking proof that the Sphinx’s riddle is hard, because that man can’t recognize anyone: not the Corinthian, whom he last saw as a young man, and certainly not Oedipus, a baby with whom he’d had a passing acquaintance decades earlier. “It all took place so long ago,” he grumbles. “Why on earth would you ask me?”

“Because,” the Corinthian (David Strathairn) explained genially on Zoom, “this man whom you are now looking at was once that child.”

This, for me, was the scene with the catharsis in it. At a certain point, the shepherd (Frankie Faison) clearly understood everything, but would not or could not admit it. Oedipus, now determined to learn the truth at all costs, resorted to enhanced interrogation. “Bend back his arms until they snap,” Isaac said icily; in another window, Faison screamed in highly realistic agony. Faison was a personification of psychological resistance: the mechanism a mind develops to protect itself from an unbearable truth. Those invisible guardsmen had to nearly kill him before he would admit who had given him the baby: “It was Laius’s child, or so people said. Your wife could tell you more.”

Tears glinted in Isaac’s eyes as he delivered the next line, which I suddenly understood to be the most devastating in the whole play: “Did . . . she . . . give it to you?” How had I never fully realized, never felt, how painful it would have been for Oedipus to realize that his parents hadn’t loved him?

Excerpt:

If we borrow the terms of Greek drama, 2020 might be viewed as the year of anagnorisis: tragic recognition. On August 9th, the sixth anniversary of the shooting of Michael Brown, I watched the Theater of War Productions put on a Zoom production of “Antigone in Ferguson”: an adaptation of Sophocles’ “Oedipus” narrative sequel, with the chorus represented by a demographically and ideologically diverse gospel choir. Oscar Isaac was back, this time as Creon, Oedipus’ successor as king. He started out as a bullying inquisitor (“I will have your extremities removed one by one until you reveal the criminal’s name”), ordering Antigone (Tracie Thoms) to be buried alive, insulting everyone who criticized him, and accusing Tiresias of corruption. But then Tiresias, with the help of the chorus, persuaded Creon to reconsider. In a sustained gospel number, the Thebans, armed with picks and shovels, led by their king, rushed to free Antigone.

“Antigone” being a tragedy, they got there too late, resulting in multiple deaths, and in Isaac’s once again totally losing his shit. It was almost the same performance he gave in “Oedipus,” and yet, where Oedipus begins the play written into a corner, between walls that keep closing in, Creon seems to have just a little more room to maneuver. His misfortune—like that of Antigone and her brother—feels less irreversible. I first saw “Antigone in Ferguson” live, last year, and, in the discussion afterward, the subject of fate—inevitably—came up. I remember how Doerries gently led the audience to view “Antigone” as an illustration of how easily everything might happen differently, and how people’s minds can change. I remember the energy that spread through the room that night, in talk about prison reform and the urgency of collective change.

###

Again, the full article is accessible via the source link below:

#oscar isaac#theater of war#oedipus the king#antigone in ferguson#creon#frances mcdormand#john turturro#jeffrey wright#david strathairn#frankie faison#bryan doerries#sophocles#zoom#the oedipus project

117 notes

·

View notes

Note

Sita, The High Priestess Card

(Prompt asking)

(Part of this AU)

“And you’re just going to slink away in the night as he wishes?” Urmila’s words are loud enough to make Sita wince. She had gone to such pains to discover what Rama has in store for her, and if her sister should ruin it all --

“I will not allow it!” Urmila snaps, softer but still bitter. “You are his wife, a princess of Mithila, who withstood the forest, Lanka, and fire itself for his sake, and you carry his heirs. He cannot exile you on the whim of a dhobi who probably doesn’t even wash his rear end, and you cannot simply let him do this to you!”

“Shanti, Urmila,” Sita says. They have met in the temple shortly after chandrodaya, ostensibly to pray for the birth of the twins, and actually to discuss Sita’s upcoming banishment. Even in the glum light of the crescent moon, she can tell that Urmila’s cheeks are stained red with indignation. Urmila is as fiery as her husband Lakshmana, as faithful to her elder sibling and as prepared to storm the world given provocation.

Who can bridle our younger siblings? Rama had onced asked her ruefully. No one, that’s who. I suppose we should simply thank the gods for sending us such devotion.

Sita closes her eyes briefly at the memory.

“Do you think me meek?” she asks, opening her eyes once more. “Or foolish? Do you think I do not want to rend him limb from limb, and slice every tongue that slanders my unborn children?”

“Then why don’t you?” Urmila presses. “Do it. Take Ayodhya by storm, and punish everyone and anyone who ever doubted you. I’ll help you, I’ll wield a blade if necessary--”

“Because I am four months gone,” Sita says, indicating the crest of her belly. “With not one but two babies. Babies that have given me no end of trouble, and you remember what Sumitra Ma told us about carrying twins. This pregnancy will only worsen as the birth nears. I am in no condition to be staging a revolt.”

“You’re in no condition to be abandoned in the forest either,” Urmila says. Her voice is more understanding now, no doubt remembering her sister’s frequent vomiting, backaches, and swollen ankles, but still unsure.

“I do not intend to simply waste away among the trees,” Sita says, turning her gaze away from Urmila and to the open temple roof, where she can see the crescent moon, curved like a grin. She imagines Lord Chandra is smiling upon them. She hopes he is. “But first I must see the babies safely born and weaned.”

She prays that at least one of them is a boy. Sita herself would be content with only daughters, but she knows that Ayodhya prizes their males. If she has a son, it will make what she plans next easier.

“Will you come with me?” The night wind gusts through the mandir, casting back their veils and billowing their hair. Urmila says nothing, but merely clasps Sita’s hand in her own.

~

Taglist: @the-rambling-maiden @jeyaam @soniaoutloud @1nsaankahanhai-bkr @supermeh-krishnah @powerfaliure @puffdaddy-666 @bigheadedgirlwithbigdreams @scentedbasketballlandroad @starsailororastronaut @amandaanubis @pkanamika2002 @simp-for-gol-gappes @oreofrappiewithblueberry @hermioneaubreymiachase @callonpeevesie @yeswestsidernorthsider @deliciousdetectivestranger @chaitastrophicpeepalert @yass-rani @abrighterlightformoths @avani008 @ambidextrousarcher @iamnotthat @muralofmyths @alwaysthesideofwonder @psychrun @kumbhakarni @dreams-with-thoughts @thetrailofyourbloodinthesnow @rang-lo @chaanv @rosebriarr @animucomedy

Send me an ask if you want to be added (or removed) to the taglist. Also please do reblog/comment on my fics if you enjoyed them!

#ramayana#ramayan#hindu mythology#sita#urmila#queen regnant sita au#pkanamika2002#answered#myfics#the high priestess = lunar & temple & inner voice

27 notes

·

View notes