#bryan doerries

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

i love the part of sophocles' ajax where odysseus very carefully, very diplomatically debates agamemnon, trying to convince him that ajax deserves a proper burial

some of my favourite lines:

AGAMEMNON: Odysseus, are you for me or are you against me, and for this man? ODYSSEUS: I hated him when it was honourable to hate him.

!!

ODYSSEUS: He was my enemy, but he was also noble. AGAMEMNON: And you have respect for an enemy's corpse? ODYSSEUS: I am moved by admiration for his greatness, rather than by hatred for his smallness. AGAMEMNON: He was a man of many turns. ODYSSEUS: Many of our friends later become enemies. AGAMEMNON: But do you wish to praise these so-called friends? ODYSSEUS: I do not see friends and enemies as mutually exclusive.

and the finishing blow:

AGAMEMNON: I see now that every man works for himself. ODYSSEUS: Who else should a man work for?

#he forms his defence so precisely! and teucer looking on believing until now that odysseus would mock ajax too#(bryan doerries translation which is very modernized i know)#tagamemnon#agamemnon#odysseus#sophocles#telamonian ajax#first impressions tag

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

agamemnon (loudly) and odysseus (louder) still makes me laugh sorry

#they're trying to out-freak eachother... match made in tartarus <3#yes i'm rereading ajax again so what. this is bryan doerries' translation btw#agamemnon#odysseus#odysseus x agamemnon#agaody#sophocles ajax#sophocles#greek mythology#tagamemnon#xndead rambles

259 notes

·

View notes

Text

2025 book bingo tbr

i'm gonna be following the 2025 book bingo created by the magnanimous @batmanisagatewaydrug and i have just completed (to the extent i can today) my tbr! (this has also inspired me into making a list of 25 things i need to do 25 times throughout 2025... so if there's one thing i will be next year, it is occupied). i drew from books that i own/my roommate owns as much as possible.

Literary Fiction: Luster by Raven Leilani (which has been on my libby holds list since mackenzie last recommended it. abt 20 weeks to go).

2. Short Story Collection: Cursed Bunny by Bora Chung, translated by Anton Hur (advanced reader's copy i got for free from my college's book club)

3. A Sequel: A Day of Fallen Night by Samantha Shannon

4. Childhood Favorite: The Sword of Darrow by Alex and Hal Malchow or Heidi by Johanna Spyri or something i find when i am home for the holidays that calls my soul more than these two

5. 20th Century Speculative Fiction: The Silmarillion by J. R. R. Tolkein (because TECHNICALLY it counts)

6. Fantasy: Piranesi by Susanna Clarke (one of the few remaining Book of the Month editions i still own)

7. Published Before 1950: Spoon River Anthology by Edgar Lee Masters, published in 1915

8. Independent Publisher: I Love Information by Courtney Bush, published by Milkweed Editions (will need to either get over my fear of going to the library in person to set up my online account and put a hold on this OR purchase a copy)

9. Graphic Novel/Comic Book/Manga: Fun Home by Allison Bechdel or Saga by writer Brian K. Vaughan and artist Fiona Staples, have not decided (both owned by my roommate)

10. Animal on the Cover: Diminished Capacity by Sherwood Kiraly (he was my playwriting/fiction professor and gave me my copy of the novel)

11. Set in a Country You Have Never Visited: Euphoria by Lily King, set in New Guinea (owned by my roommate)

12. Science Fiction: Dirk Gently's Holistic Detective Agency by Douglas Adams

13. 2025 Debut Author: Julie Chan is Dead by Liann Zhang, expected May 2025 (another physical hold or purchase situation)

14. Memoir: Reading With Patrick by Michelle Kuo (commencement speaker at my graduation!)

15. Read a Zine, Make a Zine: tbd! will probably be more than one!

16. Essay Collection: The Book of Difficult Fruit by Kate Lebo

17. 2024 Award Winner: How to Say Babylon by Safiya Sinclair, NBCC Award for Autobiography (will borrow from libby, audiobook is also available)

18. Nonfiction: Learn Something New: I was paying more attention to the nonfiction part than the learn something new part and i do need to find a new book for this because originally i was gonna go with one of Caitlin Doughty's novels which, while lovely, are not something New To Me. i know i have a biography of Anna Freud somewhere so maybe i will dig that up? otherwise it might be a scroll-through-libby adventure

19. Social Justice & Activism: The Theater of War by Bryan Doerries (read a few chapters first year of undergrad but never the whole thing so technically it counts as a new book for me)

20. Romance Novel: Once Upon a Broken Heart by Stephanie Garber

21. Read and Make a Recipe: Jane Austen's Table by Robert Tuesley Anderson, specific recipe to be determined upon reading

22. Horror: Flowers in the Attic by V. C. Andrews (owned and recommended by my roommate as a good option for me, because i do not do well with horror. respect the genre so much!! but my anxiety disorder)

23. Published in the Aughts: Throne of Jade by Naomi Novik (just got my thrift books copy a couple weeks ago. i am making myself SAVOR this series)

24. Historical Fiction: Water for Elephants by Sara Gruen

25. Bookseller or Librarian Recommendation: tbd upon getting over my fears and actually visiting my library in person! it's a five minute walk from my apartment i do not know what my problem is

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sing Sing | Official Trailer HD | A24

youtube

this movie was as great as I expected. Better.

Rehabilitation Through Art - takes us through the process that Adam and Bryan Doerries (and the ancient Greeks before them) have been supporting for years.

Art is human. Rehumanize them.

0 notes

Text

DISABILITY AND DEATH

Books of Interest Website: chetyarbrough.blog “The Theater of War” What Ancient Greek Tragedies Can Teach Us Today By: Bryan Doerries Narrated By: Adam Driver Bryan Doerries (Author, Artistic Director of Theater of War Productions, an evangelist for classical literature and its relevance to today’s lives.) The title and book cover of “The Theater of War” is as puzzling as Bryan Doerries’…

0 notes

Photo

David Strathairn Appreciation:

The Headstrong Project 'Words Of War' Benefit at Tribeca 360

#david strathairn#special events#david strathairn appreciation#lili taylor#bryan doerries#anthony edwards

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

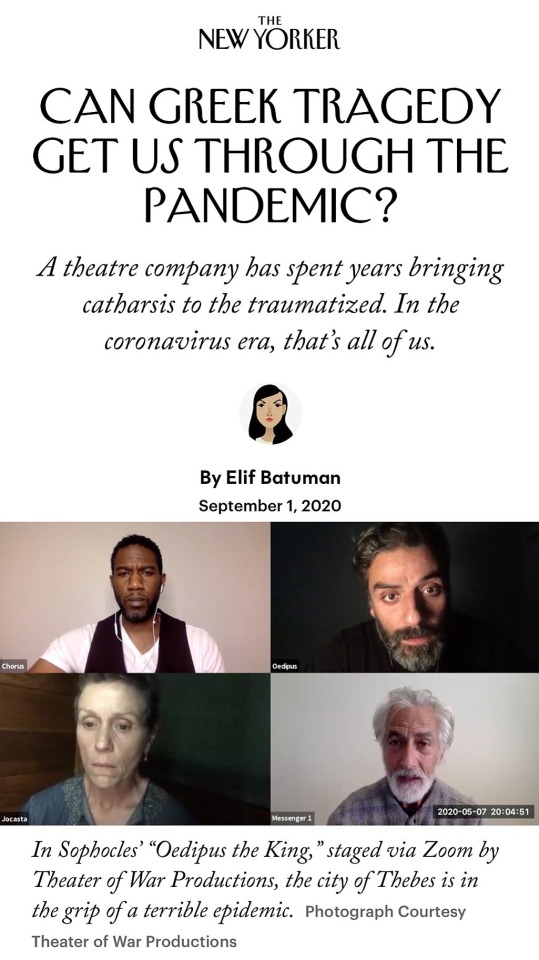

Fantastic (but long) article about Theater of War’s recent productions, including Oedipus the King and Antigone in Ferguson, featuring Oscar Isaac. The following are excerpts. The full article is viewable via the source link below:

Excerpt:

“Children of Thebes, why are you here?” Oscar Isaac asked. His face filled the monitor on my dining table. (It was my partner’s turn to use the desk.) We were a couple of months into lockdown, just past seven in the evening, and a few straggling cheers for essential workers came in through the window. Isaac was looking smoldery with a quarantine beard, a gold chain, an Airpod, and a black T-shirt. His display name was set to “Oedipus.”

Isaac was one of several famous actors performing Sophocles’ “Oedipus the King” from their homes, in the first virtual performance by Theater of War Productions: a group that got its start in 2008, staging Sophocles’ “Ajax” and “Philoctetes” for U.S. military audiences and, beginning in 2009, on military installations around the world, including in Kuwait, Qatar, and Guantánamo Bay, with a focus on combat trauma. After each dramatic reading, a panel made up of people in active service, veterans, military spouses, and/or psychiatrists would describe how the play resonated with their experiences of war, before opening up the discussion to the audience. Since its founding, Theater of War Productions has addressed different kinds of trauma. It has produced Euripides’ “The Bacchae” in rural communities affected by the opioid crisis, “The Madness of Heracles” in neighborhoods afflicted by gun violence and gang wars, and Aeschylus’ “Prometheus Bound” in prisons. “Antigone in Ferguson,” which focusses on crises between communities and law enforcement, was motivated by an analogy between Oedipus’ son’s unburied body and that of Michael Brown, left on the street for roughly four hours after Brown was killed by police; it was originally performed at Michael Brown’s high school.

Now, with trauma roving the globe more contagiously than ever, Theater of War Productions had traded its site-specific approach for Zoom. The app was configured in a way I hadn’t seen before. There were no buttons to change between gallery and speaker view, which alternated seemingly by themselves. You were in a “meeting,” but one you were powerless to control, proceeding by itself, with the inexorability of fate. There was no way to view the other audience members, and not even the group’s founder and director, Bryan Doerries, knew how numerous they were. Later, Zoom told him that it had been fifteen thousand. This is roughly the seating capacity of the theatre of Dionysus, where “Oedipus the King” is believed to have premièred, around 429 B.C. Those viewers, like us, were in the middle of a pandemic: in their case, the Plague of Athens.

The original audience would have known Oedipus’ story from Greek mythology: how an oracle had predicted that Laius, the king of Thebes, would be killed by his own son, who would then sleep with his mother; how the queen, Jocasta, gave birth to a boy, and Laius pierced and bound the child’s ankles, and ordered a shepherd to leave him on a mountainside. The shepherd took pity on the maimed baby, Oedipus (“swollen foot”), and gave him to a Corinthian servant, who handed him off to the king and queen of Corinth, who raised him as their son. Years later, Oedipus killed Laius at a crossroads, without knowing who he was. Then he saved Thebes from a Sphinx, became the king of Thebes, had four children with Jocasta, and lived happily for many years.

That’s where Sophocles picks up the story. Everyone would have known where things were headed—the truth would come out, and Oedipus would blind himself—but not how they would get there. How Sophocles got there was by drawing on contemporary events, on something that was in everyone’s mind, though it doesn’t appear in the original myth: a plague.

In the opening scene, Thebes is in the grip of a terrible epidemic. Oedipus’ subjects come to the palace, imploring him to save the city, describing the scene of pestilence and panic, the screaming and the corpses in the street. Something about the way Isaac voiced Oedipus’ response—“Children. I am sorry. I know”—made me feel a kind of longing. It was a degree of compassion conspicuous by its absence in the current Administration. I never think of myself as someone who wants or needs “leadership,” yet I found myself thinking, We would be better off with Oedipus. “I would be a weak leader if I did not follow the gods’ orders,” Isaac continued, subverting the masculine norm of never asking for advice. He had already sent for the best information out there, from the Delphic Oracle.

Soon, Oedipus’ brother-in-law, Creon—John Turturro, in a book-lined study—was doing his best to soft-pedal some weird news from Delphi. Apparently, the oracle said that the plague wouldn’t end until the people of Thebes expelled Laius’ killer: a person who was somehow still in the city, even though Laius had died many years earlier on an out-of-town trip. Oedipus called in the blind prophet, Tiresias, played by Jeffrey Wright, whose eyes were invisible behind a circular glare in his eyeglasses.

Reading “Oedipus” in the past, I had always been exasperated by Tiresias, by his cryptic lamentations—“I will never reveal the riddles within me, or the evil in you”—and the way he seemed incapable of transmitting useful information. Spoken by a Black actor in America in 2020, the line made a sickening kind of sense. How do you tell the voice of power that the problem is in him, really baked in there, going back generations? “Feel free to spew all of your vitriol and rage in my direction,” Tiresias said, like someone who knew he was in for a tweetstorm.

Oedipus accused Tiresias of treachery, calling out his disability. He cast suspicion on foreigners, and touted his own “wealth, power, unsurpassed skill.” He decried fake news: “It’s all a scam—you know nothing about interpreting birds.” He elaborated a deep-state scenario: Creon had “hatched a secret plan to expel me from office,” eliciting slanderous prophecies from supposedly disinterested agencies. It was, in short, a coup, designed to subvert the democratic will of the people of Thebes.

Frances McDormand appeared next, in the role of Jocasta. Wearing no visible makeup, speaking from what looked like a cabin somewhere with wood-panelled walls, she resembled the ghost of some frontierswoman. I realized, when I saw her, that I had never tried to picture Jocasta: not her appearance, or her attitude. What was her deal? How had she felt about Laius maiming their baby? How had she felt about being offered as a bride to whomever defeated the Sphinx? What did she think of Oedipus when she met him? Did it never seem weird to her that he was her son’s age, and had horrible scars on his ankles? How did they get along, those two?

When you’re reading the play, you don’t have to answer such questions. You can entertain multiple possibilities without settling on one. But actors have to make decisions and stick to them. One decision that had been made in this case: Oedipus really liked her. “Since I have more respect for you, my dear, than anyone else in the world,” Isaac said, with such warmth in “my dear.” I was reminded of the fact that Euripides wrote a version of “Oedipus”—lost to posterity, like the majority of Greek tragedies—that some scholars suggest foregrounds the loving relationshipbetween Oedipus and Jocasta.

Jocasta’s immediate task was to defuse the potentially murderous argument between her husband and her brother. She took one of the few rhetorical angles available to a woman: why, such grown men ought to be ashamed of themselves, carrying on so when there was a plague going on. And yet, listening to the lines that McDormand chose to emphasize, it was clear that, in the guise of adult rationality and spreading peace, what she was actually doing was silencing and trivializing. “Come inside,” she said, “and we’ll settle this thing in private. And both of you quit making something out of nothing.” It was the voice of denial, and, through the play, you could hear it spread from character to character.

By this point in the performance, I found myself spinning into a kind of cognitive overdrive, toggling between the text and the performance, between the historical context, the current context, and the “universal” themes. No matter how many times you see it pulled off, the magic trick is always a surprise: how a text that is hundreds or thousands of years old turns out to be about the thing that’s happening to you, however modern and unprecedented you thought it was.

Excerpt:

The riddle of the Sphinx plays out in the plot of “Oedipus,” particularly in a scene near the end where the truth finally comes out. Two key figures from Oedipus’ infancy are brought in for questioning: the Theban shepherd, who was supposed to kill baby Oedipus but didn’t; and the Corinthian messenger to whom he handed off the maimed child. The Theban shepherd is walking proof that the Sphinx’s riddle is hard, because that man can’t recognize anyone: not the Corinthian, whom he last saw as a young man, and certainly not Oedipus, a baby with whom he’d had a passing acquaintance decades earlier. “It all took place so long ago,” he grumbles. “Why on earth would you ask me?”

“Because,” the Corinthian (David Strathairn) explained genially on Zoom, “this man whom you are now looking at was once that child.”

This, for me, was the scene with the catharsis in it. At a certain point, the shepherd (Frankie Faison) clearly understood everything, but would not or could not admit it. Oedipus, now determined to learn the truth at all costs, resorted to enhanced interrogation. “Bend back his arms until they snap,” Isaac said icily; in another window, Faison screamed in highly realistic agony. Faison was a personification of psychological resistance: the mechanism a mind develops to protect itself from an unbearable truth. Those invisible guardsmen had to nearly kill him before he would admit who had given him the baby: “It was Laius’s child, or so people said. Your wife could tell you more.”

Tears glinted in Isaac’s eyes as he delivered the next line, which I suddenly understood to be the most devastating in the whole play: “Did . . . she . . . give it to you?” How had I never fully realized, never felt, how painful it would have been for Oedipus to realize that his parents hadn’t loved him?

Excerpt:

If we borrow the terms of Greek drama, 2020 might be viewed as the year of anagnorisis: tragic recognition. On August 9th, the sixth anniversary of the shooting of Michael Brown, I watched the Theater of War Productions put on a Zoom production of “Antigone in Ferguson”: an adaptation of Sophocles’ “Oedipus” narrative sequel, with the chorus represented by a demographically and ideologically diverse gospel choir. Oscar Isaac was back, this time as Creon, Oedipus’ successor as king. He started out as a bullying inquisitor (“I will have your extremities removed one by one until you reveal the criminal’s name”), ordering Antigone (Tracie Thoms) to be buried alive, insulting everyone who criticized him, and accusing Tiresias of corruption. But then Tiresias, with the help of the chorus, persuaded Creon to reconsider. In a sustained gospel number, the Thebans, armed with picks and shovels, led by their king, rushed to free Antigone.

“Antigone” being a tragedy, they got there too late, resulting in multiple deaths, and in Isaac’s once again totally losing his shit. It was almost the same performance he gave in “Oedipus,” and yet, where Oedipus begins the play written into a corner, between walls that keep closing in, Creon seems to have just a little more room to maneuver. His misfortune—like that of Antigone and her brother—feels less irreversible. I first saw “Antigone in Ferguson” live, last year, and, in the discussion afterward, the subject of fate—inevitably—came up. I remember how Doerries gently led the audience to view “Antigone” as an illustration of how easily everything might happen differently, and how people’s minds can change. I remember the energy that spread through the room that night, in talk about prison reform and the urgency of collective change.

###

Again, the full article is accessible via the source link below:

#oscar isaac#theater of war#oedipus the king#antigone in ferguson#creon#frances mcdormand#john turturro#jeffrey wright#david strathairn#frankie faison#bryan doerries#sophocles#zoom#the oedipus project

117 notes

·

View notes

Video

tumblr

So I’ve downloaded the audiobook of The Theater of War by Bryan Doerries, read by our dear and amazing Adam Driver. I suggest to everyone to listen to it because not only is informative and interesting, but... ADAM “PERFORMANCES” 🥵 🥵 ... Listen to this WITH EARPHONES BECAUSE EHM EHM (could sound NSFW if you are in public! I warned you) lol, enjoy.

You can find this part at chapter 7, the book is downloadable from Audible.com

49 notes

·

View notes

Note

So George Lucas says the saga was meant to begin and end with Anakin? So where WERE you Grandpa when Our Boy Ben was in the pit? Giving a PEP talk to Palpatine's granddaughter that's where. Seriously - I would have been OK with them killing him off if all this made any kind of SENSE.

Hi Anon,

I know, right? If their plan was always to kill Ben Solo, they should have done a better job of it. My interest in Adam Driver and his work with AITAF led me to a lot of unexpected reading over the past few years (for deep nerd pleasure, pick up the audio book of Bryan Doerries, "Theatre of War: What Ancient Greek Tragedies Can Teach Us Today." Adam is the reader!). I've never been a fan of tragedy, but Driver made me really take a look at it, and I think I understand its purpose in storytelling.

Part of what makes TROS feel so awful is that it fails as a story. It fails as a tragedy, in that it doesn't deliver catharsis; only pain. It fails in very practical, this-is-the-least-you-must-do aspects of character development, plot, and arc. To be clear, I'm not a writer (my training is in fine arts and I'm most the shepherd and woodstove-operator these days), but the errors made in the TROS script are so blatant, it's difficult to understand how it got to the screen.

If we're to believe the rumors, there may be footage of Hayden Christiansen/Anakin Skywalker that was shot for TROS. Given what we've seen in the film that was released, I honestly have no idea if these scenes would have helped the story or made it worse. I know I would have loved it if Anakin had shown up to help Ben defeat Palpatine (again 🙄). Can you imagine how cool it would have been to see those two actors in a scene together? And the story really needed it to happen.

21 notes

·

View notes

Video

tumblr

Adam Driver reading Bryan Doerries 'Rum & Vodka' for Theater For War.

Adam is speaking in Irish

659 notes

·

View notes

Text

i started reading sophocles' ajax (bryan doerries translation) last night and ohhh my god, it is relentless and horrific and so so good

most of all i'm struck at how realistically it portrays a ptsd-related mental break. but then i've read that sophocles saw his fair share of battle so it seems he might have had some first-hand observations

TECMESSA: You sailors who serve Ajax, those of us who care for the house of Telamon will soon wail, for our fierce hero sits shell-shocked in his tent, glazed over, gazing into oblivion.

tecmessa is ajax' concubine, the mother of his child, and the one who has to, quote, "care for the incurable ajax"

TECMESSA: In his madness he took pleasure in the evil that possessed him, all the while afflicting those of us nearby, but now that the fever has broken all of his pleasure has turned to pain, and we are still afflicted, just as before.

and everyone knows, everyone can see the great ajax breaking!

ODYSSEUS: I feel sorry for him, though he hates me. A savage infection confuses his mind. It could easily have been me.

#and the stuff ajax does during his mental break is SO much more horrific than merely 'slaughtering the cattle' like the summaries say#that opening scene feels like getting all your teeth knocked out in one punch#doerries' translation is extremely modern (see 'shellshocked') but i think it effectively gets the points across#telamonian ajax#sophocles#ajax#tecmessa#odysseus#first impressions tag

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

agamemnon folding for odysseus is a fork found in kitchen

#me when a bad bitch tells me to do something:#ok it was for a good cause this time but. yknow. agamemnon you are not a serious man#translator is bryan doerries#odysseus#agamemnon#odysseus x agamemnon#agaody#sophocles#sophocles ajax#greek mythology#tagamemnon#xndead rambles

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

His project "The Theater of War" evolved from that first event, and with funding from the U.S. Department of Defense, this 2,500-year-old play has since been performed more than two hundred times here and abroad to give voice to the plight of combat veterans and foster dialogue and understanding in their families and friends.

"The Body Keeps the Score: Mind, brain and body in the transformation of trauma" - Bessel van der Kolk

#book quote#the body keeps the score#bessel van der kolk#nonfiction#bryan doerries#the theater of war#us department of defense#ajax#combat veteran#understand#family and friends#theater#therapy

0 notes

Photo

The Odyssey of Sergeant Jack Brennan by Bryan Doerries "Tragic, poignant, and at times funny and hopeful, The Odyssey of Sergeant Jack Brennan brilliantly conveys the profound challenges that many of today’s veterans face upon returning to civilian life, even as it tells “the oldest war story of all time.”"

#The Odyssey of Sergeant Jack Brennan#comics#graphic novel#semper fi#USMC#Bryan Doerries#currently reading

0 notes

Text

Here’s a new online performance featuring Oscar Isaac to look forward to! It will stream on Zoom on Saturday, July 16, from 1-3pm Eastern. You can RSVP for free here.

More details from the source link below:

The Suppliants Project: Ukraine presents live, dramatic readings of Aeschylus’ play The Suppliants on Zoom—featuring professional actors and a chorus of Ukrainian citizens—to help frame global discussions about the War in Ukraine and the unique challenges now faced by the people of Ukraine and those who support them. Using a 2,500-year-old text as catalyst for a powerful, international discussion, The Suppliants Project: Ukraine will amplify and humanize the voices and perspectives of Ukrainian citizens, refugees, soldiers, immigrants, politicians, activists, and artists who will participate in the performance and discussion on their personal devices on Zoom from locations within Ukraine and in neighboring countries.

The Suppliants is an ancient Greek play about a group of refugees who seek asylum in the city of Argos from forced marriage and violence. The play not only depicts the struggle of these refugees to cross a border into safety, but also the internal struggle within the country that ultimately receives them, as its citizens wrestle with how best to address the crisis at their border and whether to go to war on behalf of the refugees seeking their protection.

Featuring performances by Oscar Isaac, Willem Dafoe, David Strathairn, and company members of the ProEnglish Theatre, Kyiv, Ukraine: Alina Zievakova, Anabell Ramirez, Daniil Prymachov, Kira Meschcherska, and Stanislav Galiant.

Co-presented by Theater of War and ProEnglish Theatre in Kyiv. Translated and directed by Bryan Doerries. This event will be captioned in English and Ukrainian.

#oscar isaac#willem dafoe#david strathairn#theater of war#the suppliants project#ukraine#proenglish theatre#online performance#streaming

81 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Adam reciting "After Thousands Of Years, A Play Torn From The Headlines" by Bryan Doerries at Warrior Resilience Conference in 2008. He was only a third year kid in Juilliard by the time.

66 notes

·

View notes