#and ursula le guin

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

if you have fantasy or historical fiction book recommendations, would you send them to me please? :)

#also i do really like sci fi SOMETIMES#like i liked NK Jemison's broken earth series#and ursula le guin#and parable of the sower#but sci fi is not my favorite genre#also prefer women or queer authors bc idc what cis men have to say to me thx

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

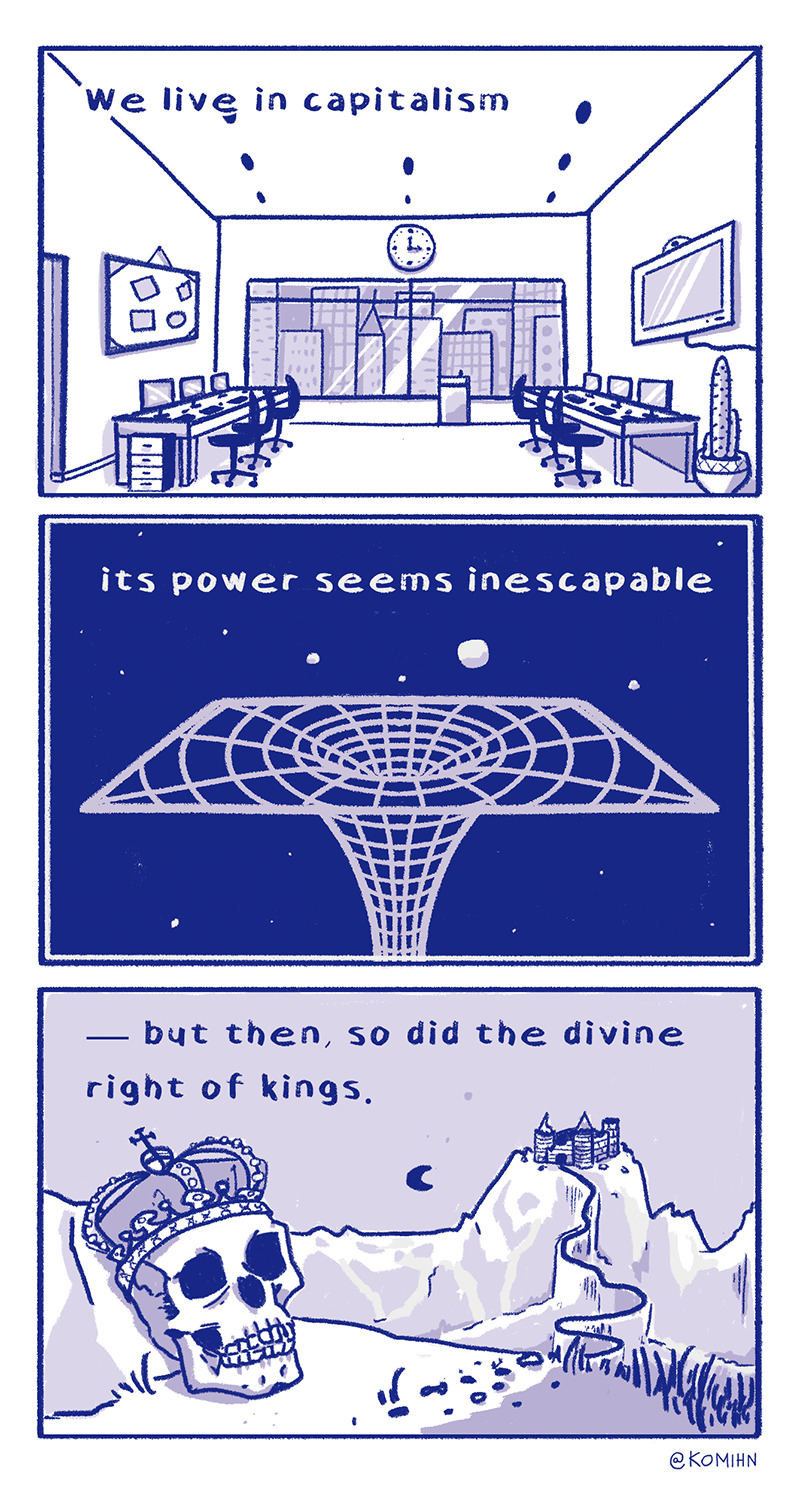

Launching my first art blogs with a small comic based on the amazing words of Ursula K. Le Guin!

92K notes

·

View notes

Text

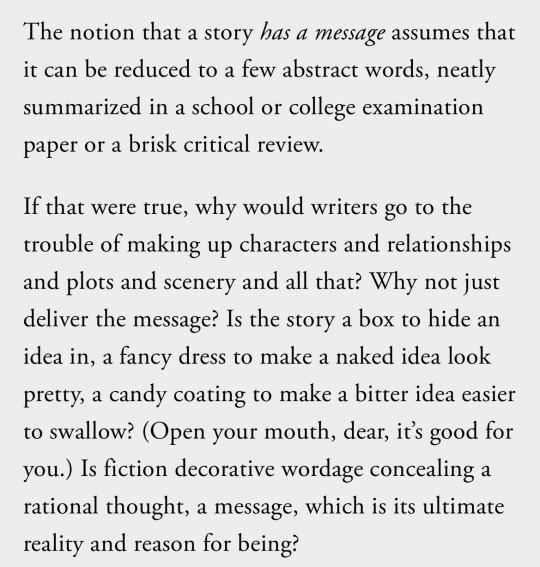

— Ursula K. Le Guin, from “A Rant About ‘Technology’”

58K notes

·

View notes

Text

I think about this every hour of every day of every month by the way

#lgbt#queer#queerness#gay#lesbian#bisexual#transgender#transsexual#transvestism#lgbtq#ursula k. le guin

49K notes

·

View notes

Text

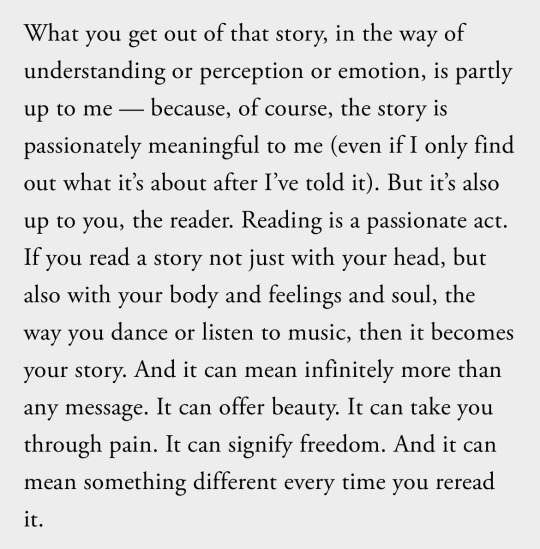

Ursula K. Le Guin

32K notes

·

View notes

Text

the other wind

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

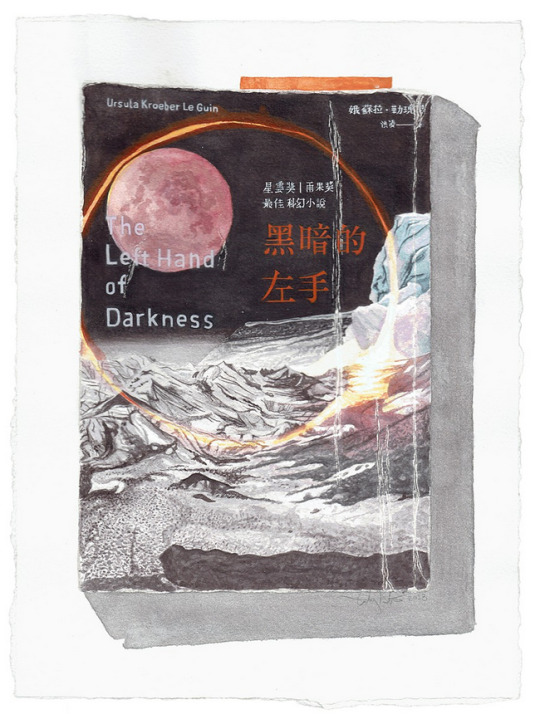

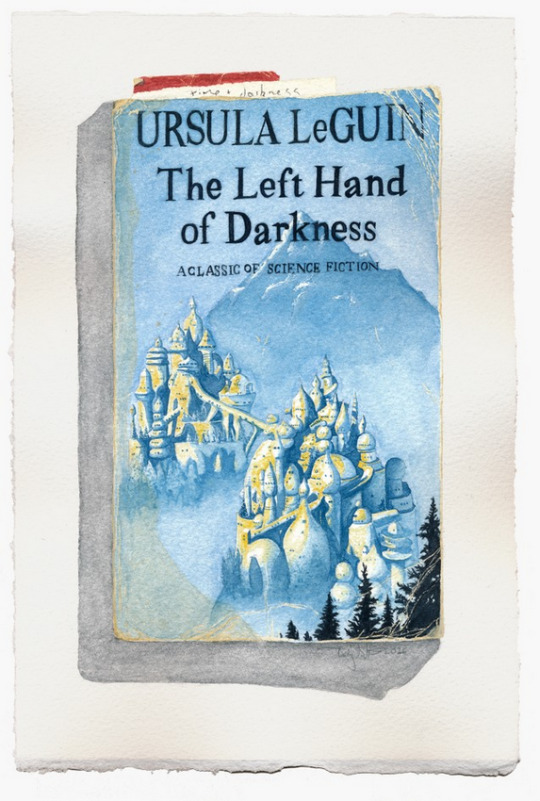

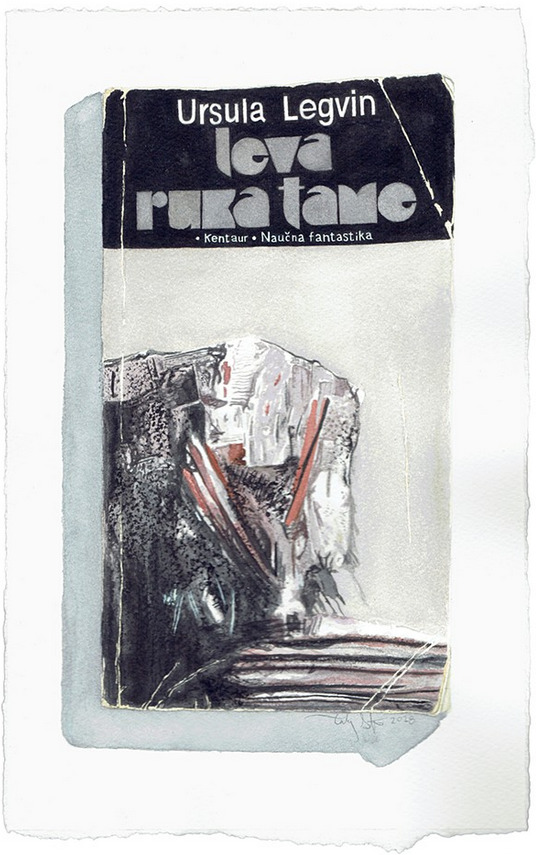

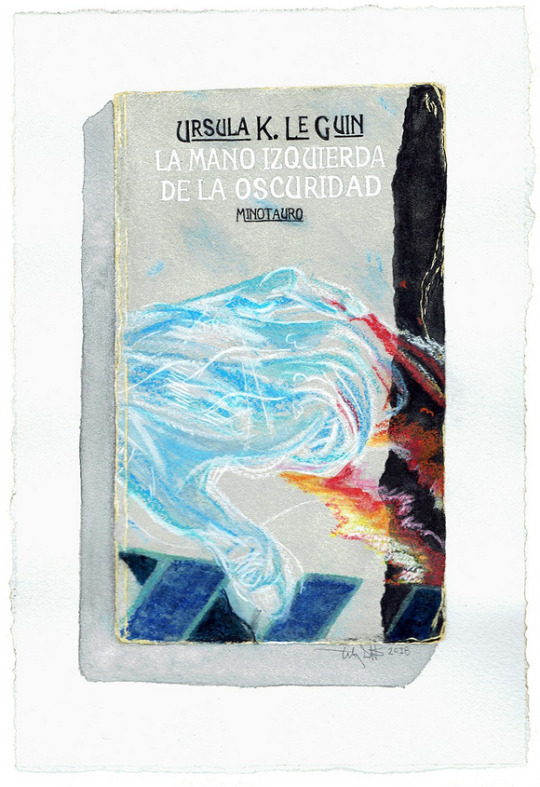

watercolors by trans artist tuesday smilie

16K notes

·

View notes

Text

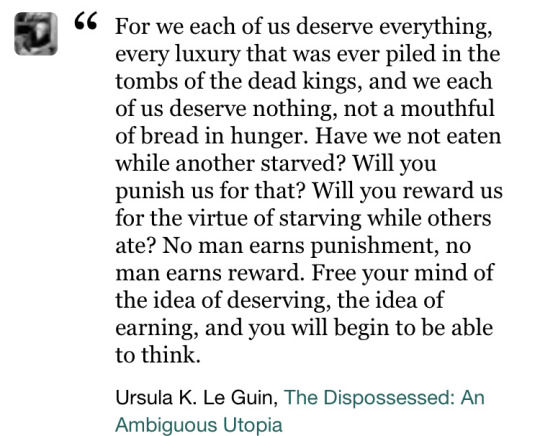

It’s an Ursula k le Guin free your mind from the idea of deserving kind of day

34K notes

·

View notes

Text

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Genly Ai

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

"For we each of us deserve everything, every luxury that was ever piled in the tombs of the dead kings, and we each of us deserve nothing, not a mouthful of bread in hunger. Have we not eaten while another starved? Will you punish us for that? Will you reward us for the virtue of starving while others ate? No man earns punishment, no man earns reward. Free your mind of the idea of deserving, the idea of earning, and you will begin to be able to think."

-Ursula K. Le Guin's The Dispossesed

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

"The idea of reforming Omelas is a pleasant idea, to be sure, but it is one that Le Guin herself specifically tells us is not an option. No reform of Omelas is possible — at least, not without destroying Omelas itself:

If the child were brought up into the sunlight out of that vile place, if it were cleaned and fed and comforted, that would be a good thing, indeed; but if it were done, in that day and hour all the prosperity and beauty and delight of Omelas would wither and be destroyed. Those are the terms.

'Those are the terms', indeed. Le Guin’s original story is careful to cast the underlying evil of Omelas as un-addressable — not, as some have suggested, to 'cheat' or create a false dilemma, but as an intentionally insurmountable challenge to the reader. The premise of Omelas feels unfair because it is meant to be unfair. Instead of racing to find a clever solution ('Free the child! Replace it with a robot! Have everyone suffer a little bit instead of one person all at once!'), the reader is forced to consider how they might cope with moral injustice that is so foundational to their very way of life that it cannot be undone. Confronted with the choice to give up your entire way of life or allow someone else to suffer, what do you do? Do you stay and enjoy the fruits of their pain? Or do you reject this devil’s compromise at your own expense, even knowing that it may not even help? And through implication, we are then forced to consider whether we are — at this very moment! — already in exactly this situation. At what cost does our happiness come? And, even more significantly, at whose expense? And what, in fact, can be done? Can anything?

This is the essential and agonizing question that Le Guin poses, and we avoid it at our peril. It’s easy, but thoroughly besides the point, to say — as the narrator of 'The Ones Who Don’t Walk Away' does — that you would simply keep the nice things about Omelas, and work to address the bad. You might as well say that you would solve the trolley problem by putting rockets on the trolley and having it jump over the people tied to the tracks. Le Guin’s challenge is one that can only be resolved by introspection, because the challenge is one levied against the discomforting awareness of our own complicity; to 'reject the premise' is to reject this (all too real) discomfort in favor of empty wish fulfillment. A happy fairytale about the nobility of our imagined efforts against a hypothetical evil profits no one but ourselves (and I would argue that in the long run it robs us as well).

But in addition to being morally evasive, treating Omelas as a puzzle to be solved (or as a piece of straightforward didactic moralism) also flattens the depth of the original story. We are not really meant to understand Le Guin’s 'walking away' as a literal abandonment of a problem, nor as a self-satisfied 'Sounds bad, but I’m outta here', the way Vivier’s response piece or others of its ilk do; rather, it is framed as a rejection of complacency. This is why those who leave are shown not as triumphant heroes, but as harried and desperate fools; hopeless, troubled souls setting forth on a journey that may well be doomed from the start — because isn’t that the fate of most people who set out to fight the injustices they see, and that they cannot help but see once they have been made aware of it? The story is a metaphor, not a math problem, and 'walking away' might just as easily encompass any form of sincere and fully committed struggle against injustice: a lonely, often thankless journey, yet one which is no less essential for its difficulty."

- Kurt Schiller, from "Omelas, Je T'aime." Blood Knife, 8 July 2022.

#kurt schiller#ursula k. le guin#quote#quotations#the ones who walk away from omelas#trolley problem#activism#introspection#discomfort#reform#revolution#suffering#ethics#morality

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

I think to topple the devine rights of kings billionaires, we need to dispel the myth that they have that money because they are smart and worked hard and make good decisions

I think the zip ties on the submarine and the limited views on the advertising platform might begin to show them for what they are

They are not smarter than you. They are not better than you. And if you suddenly magically got all that money people would stop saying 'no' to you too. and that is not a good thing

#oceangate#Twitter#Billionaires#Ursula le guin was right#Ah lads#I googled her for the quote#And just realised she died#Aaah now im sad

13K notes

·

View notes

Text

3K notes

·

View notes