#and play with the inevitable loss of culture

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I'm hardly the first to make this observation, but the problem with many self-proclaimed cozy stories is that they're so scared to take risks, scared to do anything that could make the reader even slightly uncomfortable, because being uncomfortable isn’t very cozy. Characters lack in flaws and messiness; conflict is lackluster or quickly resolved or avoided altogether; a darker moment must always be followed by a peptalk, never lingered on; moral ambiguity is eschewed, because anything else would be problematic and messy. If a main character has flaws it’s always those of the good victim, someone who needs to heal and be validated but not grow and be challenged. Challenge, of character or reader, is anathema.

As I'm playing Stray, I'm struck by the thought that this is quite possibly the coziest piece of media I've ever experienced. You're playing as a little kitty cat. You’re carrying around a tiny robot companion in a backpack. Your enemies are tiny white blobs called zorks. There are game mechanics to meow and scratch up people's walls and furniture and knock paint cans off shelves and take naps. The pacing rarely rushes you, rather actively encourages you to slow down. You can stop and listen to a guy play guitar, or look for flowers to gift someone, or take a nap on a cushion while beautiful scenery full of plants and fairy lights roll by.

But it’s also a game set in the ruins of a near dead world. The cute blobs will eat you alive. The robot you're carrying is an uploaded mind earnestly struggling through an existential crisis and mourning an entire species. Under the plants and the fairy lights is garbage and rust and buildings falling apart. There’s no sunlight. There are creepy eyes watching you in the sewers. There’s classism and oppression and the downfall of man.

And through it all, the robots who inherited the world are working so hard to find pockets of hope and happiness. They paint and play music and play games and dance and grow plants and create cozy little homes for themselves. They resist for the sake of freedom and autonomy, they create an entire language, they dream of a world most think they'll never see.

This dichotomy of dark and light is something I see often in (better) cozy media. Dungeon Meshi is a fun cozy adventure where they make delicious food and talk about self-care. It's also about grief and the inevitability of death and the impacts of social inequalities. The Long Way to a Small Angry Planet is a cozy found family road trip in space; it’s also about the difficulties of understanding each other across cultural barriers and the massive ramifications when we refuse to do so. Legends and Lattes is basically a dnd coffeshop au; it’s also about struggling to find happiness and purpose and self-worth after a life of violence, not knowing if you're able to successfully achieve anything but bloodshed. And All the Stars is full of found family and pastries and characters just hanging out; all of this happens as they're hiding and fleeing from invading aliens who see them as nothing but a resurce to be used. One of my favorite episodes of critical role is the beach episode of c2, where they basically just hang out; this happens soon after they buried their friend who died trying to save them, as they're trying to figure out who they are and what they want after his loss.

And that’s the thing, isn't it? Any story that is uniformly the same thing all the way through ends up as bland. A grimdark story that never offers respite or moments of hope will numb you to the horrors, removing their bite. A cozy story that offers nothing to be struggled against, nothing for which cozy moments and aesthetics is a break, lacks impact. A story needs ups and downs, a rhythm of misery and hope.

#nella talks#stray#i finished the game today! really enjoyed it but missed like half the memories lol#so probably gonna replay it soon-ish with a guide or smth to find them all#anyway this is my guide to a writing a good cozy story:#do not shy away from darkness and conflict and messiness. jusy don’t make it the central focus#zoom in on how characters rest and heal and forgive and reach out to each other. slow down and let readers and characters breathe#show exactly what the coziness is a respite from and how and why it matters

408 notes

·

View notes

Note

Love love LOVE your post about how high level sports culture transfers into the wilderness environment in YJ and i think it can also apply to the survival/staying on the team aspect. I’m not a soccer player but i do a contact sport (competitive cheerleading) and when you get knocked down you can’t be down too long before you get up again. If you’re bleeding, bruised, or sick, tough shit, because you have to prove you can keep going in order to stay on the mat/field/whatever. making too many excuses for yourself even if it’s for “valid reasons” is a sign of weakness because you have to be willing to put yourself through pretty much any physical or mental discomfort in order to beat out the competition. if you’re not 100% dedicated to the game then you can’t win and there’s a certain amount of respect lost, even if you otherwise get along.

Specifically Jackie reminds me of girls i know from cheer who were made captains for personality reasons but had less of the inherent talent and drive to win than some others did. in a wilderness environment there’s no institution to protect her position of power so she loses the team’s loyalty pretty fast once it’s shown she’s not as ruthless as them

Tysm !! Yeah that was definitely the thing with Jackie. Her death became almost inevitable because she wasnt playing for the team anymore. Allie's fate is meant to foreshadow jackies - she wasnt keeping up, couldnt "play under pressure", so she gets literally 'frozen out'.

The thing is I personally dont think its that Jackie didnt have that ruthlessness, so much as she wasnt someone who could find motivation in the threat of loss. some people are like that, and in a competitive sports setting its a superpower rly. she always only let herself see the possible win and that spurred her on, not the threat of losing or the frustration of letting in a goal you shouldnt have. its why she was always the one able to rally the girls. its why she was captain. she could focus all that negative energy they had into a positive team outcome. you go two goals down in a first half you need a captain who can point out the positives and rally you to make a comeback against the odds, not one thats seething in the corner or barking at you for your mistakes. the circumstances of the wilderness and reading shaunas journal took that from jackie. she had nothing left, nothing to spur her on anymore, she was clearly depressed and convinced she was basically as good as dead already. as a striker when jackie lost the ball its wasnt necessarily expected that she'd be the one to win it back, shauna was her defensive mid, always there to pick up the pieces. jackie never learned how recover the ball and go again without her, so she dies.

Jackie put in the hours to be a good enough striker to take them to nationals when we know she canonically perhaps wasnt as naturally talented, fast, or technical as some of her teammates. to me that says something about her drive and ruthlessness on the field. she became captain because of that mindset. a positive, winning-focused mindset, that unfortunately just didnt translate to the wilderness well because 1) shaunas betrayal tore up her plans and hopes for the future, giving her nothing to fight for 2) this is an environment where the grudge/anger/threat-based mindsets thrive

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

EXTERNAL INFLUENCES IN DUNGEON MESHI: INDIAN PHILOSOPHY

(SPOILERS FOR DUNGEON MESHI BELOW)

We know that Ryoko Kui spent considerable time at the beginning of working on Dungeon Meshi doing research and planning the series. Kui constantly references real world culture, history and mythology, but she also occasionally references real-world philosophy.

The story of Dungeon Meshi is full of philosophical questions about the joy and privilege of being alive, the inevitability of death and loss, the importance of taking care of yourself and your loved ones, and the purpose and true nature of desire. Kui explores these issues through the plot, the characters, and even the fundamental building blocks that make up her fictional fantasy world. Though it’s impossible to say without Kui making a statement on the issue, I believe Dungeon Meshi reflects many elements of ancient Indian philosophy and religion.

It’s possible that Kui just finds these ideas interesting to write about, but doesn’t have any personal affiliation with either religion, however I would not be at all surprised if I learned that Kui is a Buddhist, or has personal experience with Buddhism, since it’s one of the major religions in Japan.

I could write many essays trying to explain these extremely complex concepts, and I know that my understanding of them is imperfect, but I’ll do my best to explain them in as simple a way as possible to illustrate how these ideas may have influenced Kui’s work.

HINDUISM

Hinduism is the third-largest religion in the world and originates in India. The term Hinduism is a huge umbrella that encompasses many diverse systems of thought, but they have some shared theological elements, and share many ancient texts and myths.

According to Classical Hindu belief, there are four core goals in human life, and they are the pursuit of dharma, artha, kama, and moksha.

Dharma is the natural order of the universe, and also one’s obligation to carry out their part in it. It is the pursuit and execution of one’s inherent nature and true calling, playing one’s role in the cosmic order.

Artha is the resources needed for an individual’s material well-being. A central premise of Hindu philosophy is that every person should live a joyous, pleasurable and fulfilling life, where every person's needs are acknowledged and fulfilled. A person's needs can only be fulfilled when sufficient means are available.

Kama is sensory, emotional, and aesthetic pleasure. Often misinterpreted to only mean “sexual desire”, kama is any kind of enjoyment derived from one or more of the five senses, including things like having sex, eating, listening to music, or admiring a painting. The pursuit of kama is considered an essential part of healthy human life, as long as it is in balance with the pursuit of the three other goals.

Moksha is peace, release, nirvana, and ultimate enlightenment. Moksha is freedom from ignorance through self-knowledge and true understanding of the universe, and the end of the inevitable suffering caused by the struggle of being alive. When one has reached true enlightenment, has nothing more to learn or understand about the universe, and has let go of all earthly desires, they have attained moksha, and they will not be reborn again. In Hinduism’s ancient texts, moksha is seen as achievable through the same techniques used to practice dharma, for example self-reflection and self-control. Moksha is sometimes described as self-discipline that is so perfect that it becomes unconscious behavior.

The core conflict of Hinduism is the eternal struggle between the material and immaterial world. It is often said that all of the material world is “an illusion,” and what this means is that all good and bad things will inevitably end, because the material world is finite. On the one hand, this is sad, because everything good in life will one day cease to exist, but on the other hand, this is reassuring, because all of the bad things will eventually end as well, and if one can accept this, they will be at peace.

The central debate of Hinduism is, which is more important: Satisfying your needs as a living thing, having a good life as a productive member of society, serving yourself, your family, and the world by participating in it the way nature intended? Or is it rejecting desire and attachment, discovering the true nature of existence, realizing the impermanence of material things, and that one can only escape the suffering that comes from the struggle of life by accepting that death and loss are inevitable?

There is no set answer to this question, and most believers of Hinduism tend to strike a balance between the two extremes simply because that’s what happens when a person leads a normal, average life, however there are also those who believe that pursuing extremes will lead to ultimate enlightenment and final release as well.

BUDDHISM

Buddhism is an Indian religion and philosophical tradition that originated in the 5th century BCE, based on teachings attributed to religious teacher the Buddha. It is the world's fourth-largest religion and though it began in India, it has spread throughout all of Asia and has played a major role in Asian culture and spirituality, eventually spreading to the West beginning in the 20th century.

Buddhism is partially derived from the same worldview and philosophical belief system as Hinduism, and the main difference is that the Buddha taught that there is a “middle way” that all people should strive to attain, and that the excesses of asceticism (total self-denial) or hedonism (total self-indulgence) practiced by some Hindus could not lead a person to moksha/enlightenment/release from suffering.

Buddhism teaches that the primary source of suffering in life is caused by misperception or ignorance of two truths; nothing is permanent, and there is no individual self.

Buddhists believe that dukkha (suffering) is an innate characteristic of life, and it is manifested in trying to “have” or “keep” things, due to fear of loss and suffering. Dukkha is caused by desire. Dukkha can be ended by ceasing to feel desire through achieving enlightenment and understanding that everything is a temporary illusion.

There are many, many other differences between Hinduism and Buddhism, but these elements are the ones that I think are most relevant to Kui’s work.

Extreme hedonism involves seeking sensual pleasure without any limits. This could just be indulging in what people would consider “normal” pleasures, like food, sex, drugs and the arts, but it can also involve doing things which are considered socially repugnant, either literally or by taking part in symbolic rituals that represent these acts. Some examples are holding religious meetings in forbidden places, consuming forbidden substances (including human flesh), using human bones as tools, or engaging in sex with partners who are considered socially unacceptable (unclean, wrong gender, too young, too old, related to the practitioner). Again, these acts may be done literally or symbolically.

Extreme ascetic practices involve anything that torments the physical body, and some examples are meditation without breathing, the total suppression of bodily movement, refusing to lay down, tearing out the hair, going naked, wearing rough and painful clothing, laying on a mat of thorns, or starving oneself.

HOW THIS CONNECTS TO DUNGEON MESHI

Kui’s most emphasized message in Dungeon Meshi is that being alive is a fleeting, temporary experience that once lost, cannot truly be regained, and is therefore precious in its rarity. Kui also tells us that to be alive means to desire things, that one cannot exist without the other, that desire is essential for life. This reflects the four core goals of human life in Hinduism and Buddhism, but also could be a criticism of some aspects of these philosophies.

I think Kui’s story shows the logical functionality of the four core goals: only characters who properly take care of themselves, and who accept the risk of suffering are able to thrive and experience joy. I think Kui agrees with the Buddhist stance that neither extreme hedonism nor extreme self-denial can lead to enlightenment and ultimate bliss… But I also think that Kui may be saying that ultimate bliss is an illusion, and that the greatest bliss can only be found while a person is still alive, experiencing both loss and desire as a living being.

Kui tells us living things should strive to remain alive, no matter how difficult living may be sometimes, because taking part in life is inherently valuable. All joy and happiness comes from being alive and sharing that precious, limited life with the people around you, and knowing that happiness is finite and must be savored.

Dungeon Meshi tells us souls exist, but never tells us where they go or what happens after death. I think this is very intentional, because Kui doesn’t want readers to think that the characters can just give up and be happy in their next life, or in an afterlife.

There is resurrection in Dungeon Meshi, but thematically there are really no true “second chances.” Although in-universe society views revival as an unambiguous good and moral imperative, Kui repeatedly reminds us of its unnatural and dangerous nature. Although reviving Falin is a central goal of the story, it is only when Laios and Marcille are able to let go of her that the revival finally works… And after the manga’s ending, Kui tells us Falin leaves Laios and Marcille behind to travel the world alone, which essentially makes her dead to them anyway, since she is absent from their lives.

At the same time, Kui tells us that trying to prevent death, or avoid all suffering and loss is a foolish quest that will never end in happiness, because loss and suffering are inevitable and must someday be endured as part of the cycle of life. Happiness cannot exist without suffering, just like the joy of eating requires the existence of hunger, and even starvation.

Kui equates eating with desire itself, using it as a metaphor to describe anything a living creature might want, Kui also views the literal act of eating as the deepest, most fundamental desire of a living thing, the desire that all other desires are built on top of. If a living thing doesn’t eat, it will not have the energy necessary to engage with any other part of life. Toshiro, Mithrun, and Kabru are all examples of this in the story: They don’t take care of themselves and they actively avoid eating, and as a result they suffer from weakness, and struggle to realize their other desires.

Kui suggests that the key difference between being alive or dead is whether or not someone experiences desire. If you are alive, even if you feel empty and cannot identify your desires like Mithrun, you still have desires because you would be dead without them. The living body desires to breathe, to eat, to sleep, even if a person has become numb, or rejected those desires either to punish themselves, or out of a lack of self-love.

Sometimes, we have to do things which are painful and unpleasant, in order to enjoy the good things that make us happy. I believe Kui is telling us that giving up, falling into despair, and refusing to participate in life is not a viable solution either.

The demon only learns to experience desire by entering into and existing in the material, finite world. This experience intoxicates the demon, and it becomes addicted to feeling both the suffering of desire, and the satisfaction of having it fulfilled. This unnatural situation is what endangers the Dungeon Meshi world, and it’s only by purging the demon of this ability to desire that the world can be saved. The demon is like a corrupted Buddha that must give up its desires in order to return to the peaceful existence it had before it was corrupted.

The demon curses Laios to never achieve his greatest desires at the end of the manga, which manifests in several ways, such as losing his monstrous form, Falin choosing to leave after she’s revived, and being unable to get close to monsters because they are afraid of him. In some ways you could compare Laios to a Bodhisattva, a person who tries to aid others in finding nirvana/moksha, even if it prolongs their own suffering and prevents them from finding personal release. Laios gives the demon peace, but Laios himself will never be able to satisfy his desires, and must eventually come to accept his loss and move on with his life.

(This is an excerpt from Chapter 3 of my Real World Cultural and Linguistic influences in Dungeon Meshi essay.)

#dungeon meshi#delicious in dungeon#the winged lion#dungeon meshi spoilers#laios touden#mithrun of the house of kerensil#analysis#The Essay#After all the conversation about Mithrun I felt it was really important to drop this excerpt today

172 notes

·

View notes

Text

Celtic Customs: Death

by autumn sierra

In honor of my friend who just recently lost a loved one, and my sister who witnessed a tragic death that she was helpless to prevent, I thought it the proper moment to reflect and write on some Celtic death customs and traditions of remembering passed loved ones.

Scotland

Before burial, the body of recently passed relatives were kept in the home, dressed and in their own beds. Family and friends would throw a celebration in honor of their lives. The Scots view death as an opportunity to both mourn the loss of a soul, but to laugh and be merry in their memory to find balance in contrary. All the furniture in the departed’s home—especially mirrors—would be covered with white linens and everyone would play music, dance, sing, and share stories around the hearth to keep memories alive.

A traditional custom practiced by the older members of the family and community include a plate of salt and a plate of soil laid on the chest of the deceased person. The soil represents the body as a physical vessel, and the salt represent the purity of the soul. It was thought that without this ritual, the ghost would not be able to rest, and would haunt their family.

Another custom was to stay up at night and watch the body, also known as a lykewake. This is now seen as a sign of respect for the deceased, but in olden times people believed that the devil would steal the body of their loved one unless they kept safe watch over it. The youth of the family were given whiskey at the beginning of the night and some tea or beer with bread at some point in the middle of the night, and would take on this responsibility for the family. The watchers would tell stories, reminisce, and sometimes recite verses from the Bible.

It was also considered bad luck to see the body of the recently deceased without touching it. A week of bad dreams would follow unless this superstition was taken seriously.

Our perception of death in the modern world is one of detachment and taboo. Many people are squeamish about even seeing a dead body, much less watching or touching one in the night. But to the Celtic people, death was not a taboo thing which had to be hidden, as it is a natural, inevitable part of being alive.

The pivotal connecting moments of birth and death link the physical and metaphysical worlds to each other. Similar to the thinning of the veil during Samhain, we each witness a thinning of the veil when we are born, and when we die. In death, the spirit of the deceased moves across the veil and into the Otherworld, the lands of gods, sìth (spirits), and the deceased.

Ireland

The Irish are no strangers to pain and loss, having experienced famine, colonization, and poverty over its long history. There are many customs that have been cultivated over generations to venerate and remember the dead which are unique to their culture, but the Irish Wake is one of the most well known funeral traditions around the world.

Most likely giving root to Scottish customs, the tone of an Irish Wake is a time of mourning and celebration. It’s an opportunity to grieve and and honor life as a treasured miracle. Those attending an Irish Wake will participate and music making, singing, and drinking, especially if the deceased was an elderly member of the community, or ill long term. However, in the instance of a young person’s or child’s death, the wakes are much more solemn and respectful of the tragedy. Family and friends meet in the home of the deceased to recount memories together, grieve, and celebrate the life lost.

The exact origins of the Irish Wake are unknown, but it’s believed that it was heavily influenced by elements of Paganism and may have originated with the Ancient Celts. The Celts believed in life after death and thought that when a person died, they then moved onto a better life in the Otherworld. The Ancient Celts saw death only as a means for a new beginning, which is where the festivities come into play.

The Irish Wake incorporates the tradition of watching over the bodies of the deceased, and some say that the term ‘wake’ originates from the Irish tradition. Lit candles were placed closely around the body and tobacco was smoked by male attendees as they stood guard against the potential of the devil seizing the deceased. It was believed that the smoke would help keep malicious spirits at bay and stop the devil from stealing the soul. Clocks were also often stopped at the time of death and mirrors covered to further protect the body, as mirrors can act as portals to other—maybe not so friendly—worlds.

The Afterlife

In ancient Celtic religion, there was a belief in an afterlife in the Otherworld (as mentioned earlier), which is considered almost like a mirror of life on Earth but without disease, pain, and sorrow. This eliminated the aspect of fear when it came to passing on since the soul continues to live following its leaving the head (where it was believed to reside). Prayers were made to the Celtic gods, and sacrifices—both animal and human—food, weapons, and precious items were ritually offered to them to bless and allow safe passage of the deceased to the Otherworld.

The gods played a fairly significant role in the lives of the Ancient Celts as evidenced by their religious practices and the existence of protective amulets and talismans within their tombs. Alongside these, Celtic tombs and burial sites contained a wide range of objects, from tools to jewellery, which prepared the soul for the journey to the Otherworld (similarly to how the Egyptians prepared their deceased for the journey in the Duat).

Cremations & Burials

The Ancient Celts buried the deceased in tombs, and alternatively cremated their bodies, a practice beginning in the early second century. Excarnation was also not uncommon, during which the body was left exposed to the elements for a period and the bones were then either buried or kept for religious ceremony.

Burials of warriors and rulers were often rife with personal belongings and other treasures including weapons, armour, gold jewellery, and even large objects like chariots and waggons. Other common items included tools, extra clothing, grooming equipment, oil lamps, food, drink, eating utensils, and gaming counters, again, in preparation for their journey through the veil.

How do these customs compare to the ones of your culture, and your family?

What is your perception of death in relation to life, and how does it mentally or emotionally affect you?

Are you afraid of death? Why?

If you could personify who or what death is, what would that look like?

I urge everyone to challenge their instilled views of what death is and what it means not only for the people witnessing it, but also for those who go through its process. Many people fear that unknown reality, but it’s something we all share and experience eventually in life. You’re never truly alone. And isn’t that thought a bit comforting?

#celtic#folk witchcraft#witch community#witchblr#witchcraft#witches#green witch#witch#witch aesthetic#witchcore#folk witch#irish witchcraft#witch blog#traditional witchcraft#witches of tumblr#celtic folklore#ancient celts#irish folk magic#irish history#ireland#scottish folk magic#scottish#scottish folklore#scotland#cunning woman#cunning folk#folk practitioner#folk magic#folklore

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Darren Criss on counting his lucky stars

Thirty-seven-year-old Darren Criss is a star on Broadway, and a regular at piano bars. "Keep the music going, you know?" he said. "I think the expression goes, 'Life is a cabaret!'" When he's in Los Angeles, it's Tramp Stamp Granny's, where he and his wife, Mia, are the owners. "It's kind of a beautiful little Hollywood tale," he said. "She slings the drinks, and I sling the tunes."

One rule in a piano bar? Play the hits. Criss had his first hit at the University of Michigan. He starred as Harry Potter in an unauthorized student show based on the books that became a YouTube sensation in 2009. "This was a very interesting moment in time," he said, of "A Very Potter Musical." "That really did kind of change my life. That would kind of set me on the path to where I am now."

I asked if "A Very Potter Musical" was the first musical to go viral. "I don't know; I guess we'll let the YouTube historians sort of decide the validity of that," Criss said. But Criss took a detour on his way to Broadway, by becoming a TV star. "'Glee' was happening at the time," he said. "And I went out for it, like hundreds of thousands of other people in my situation at that time. And I happened to book it." He played Blaine Anderson, and quickly became a fan favorite. "I owe my tenure on that show to the sub-cultural fan base army that we had gathered from the Potter stuff," he said.

Criss went on to win an Emmy and a Golden Globe for his portrayal of serial killer Andrew Cunanan in "The Assassination of Gianni Versace: American Crime Story." Now he plays an obsolete robot named Oliver in a new musical, "Maybe Happy Ending," one of the most acclaimed shows currently on Broadway. The New York Times calls it "joyful," "heartbreaking," and "supersmart."

Criss said, "This show begins with a song which is the question the show posits: Why love? Why do we do it? If we know that loving something enters you in a contract that has an inexorable back end – which is the loss of something – why do we do that, if we know that that's gonna happen?" According to Criss, this show came along at the perfect time. He and his wife, Mia, have a two-and-a-half year-old daughter, and earlier this year they welcomed a baby son. I asked, "Does this feel like the best year of your life?" "Well, it certainly is a blessed one," Criss laughed. "I've had some extraordinary years of my life, and I think this has been a certainly exciting time." He's had some hard years, too. In 2020, his father, Bill, died at 78 from a heart condition. In 2022, his brother, Chuck, died at 36 by suicide. Criss said, "I don't necessarily think of my own experience with those people specifically in my life that I have lost. But I do think about the feeling of loss, the sadness and emptiness and loneliness that that yields, because we all feel it. But the things that move me, in life and in ["Maybe Happy Ending"], are not the darkness of the loss, but the Herculean grace that it takes to be resilient in the inevitable truth of that." When he thinks about that, Darren Criss can't help but sing. "I count my lucky stars every day," he laughed. "I'm runnin' out of – there's too many! They're still showing up. I'm doing 'CBS Sunday Morning'!"

#darren criss#mia swier#bb criss#bl criss#papa criss#chuck criss#avpm#tramp stamp granny's#cbs sunday morning#maybe happy ending#maybe happy ending bway#press#dec 2024

37 notes

·

View notes

Note

How does the story change with Vergil and Dante swapped?

Is Vergil a little more laid-back, or is he still cold and serious? And by contrast, is Dante now cold and serious, or is he still laid-back?

Is Dante now Nero's father, or is it still Vergil? If it's still Vergil, is the Lady In Red more involved in their lives?

How do the events of DMC3 and DMC5 differ?

What does Vergil's dynamic with Trish and Lady look like?

Is Vergil mean to Patty or is he nice to her? (<- The most important question!)

wHOA, thank you for all the questions! I hope you enjoy the answers!

How does the story change with Vergil and Dante swapped?

I didn’t shake up a lot of the plot, at least for major stuff (Temen-Ni-Gru, Mundus, Argosax, Fortuna, etc.), but because of the differences in Vergil’s personality/way of thinking, some things are done differently. An example is his time on Fortuna, the first time; he’s probably not keeping his identity so far under wraps that it would be hard to connect the odd white-haired foreigner who showed up on the island nine months back to the sudden appearance of a white-haired baby on the steps of the orphanage. And given that Vergil Has No Tact when looking for information he feels entitled to, the scene in Deadly Fortune where he breaks into Sparda’s old bedroom while Sanctus is in there still happens, so Sanctus connects the father/son dots far, far earlier.

Is Vergil a little more laid-back, or is he still cold and serious? And by contrast, is Dante now cold and serious, or is he still laid-back?

Vergil’s not too different, aside from the fact that he has a social life now. More likely to show an emotion that’s not cold indifference. He has walls to break down, of course, but that comes with all the loss he's been through. Vergil also is not against killing humans still, he just doesn’t do it much because, 1) what’s the point, and 2) it’s unfortunately illegal. But if needed and deserved, he has no qualms.

Dante’s… well, if you’ve read Visions of V, take the little kid Dante you saw there, crank him up a bit, add trauma-induced mania, and hand him Rebellion. He really, really wants to play with his brother. He gains power, but only because getting stronger makes his inevitable fight with Vergil all the more interesting. If the fight’s not fun, what’s the point? After all, all he wanted was to play with his brother before everything went wrong.

Is Dante now Nero's father, or is it still Vergil? If it's still Vergil, is the Lady In Red more involved in their lives?

As I’m sure you gathered in the first answer, Vergil is still Nero’s father!

His trip to Fortuna was less guided by a need for power, but a need for information on Sparda solely. From what I got in my (still unfinished) reading of Deadly Fortune, Dante, and probably also Vergil, didn’t know a lot about Sparda aside from “he was our father”, so in the years after he was orphaned, Vergil was probably trying to find all the information he could on their father. Vergil was fortunate enough to meet someone who would help him navigate Fortuna’s city and culture; a woman his age named Calla. She and Vergil grew close in the months he stayed in Fortuna, but as Vergil’s search for answers on his father dug deeper, he began to feel that his presence alone would put her in danger, as Sparda’s did Eva. So he departed, with a promise that he would return. He returned nine years later to the unfortunate news that Calla was no longer alive and didn’t stick around for much longer afterwards.

How do the events of DMC3 and DMC5 differ?

DMC3 (or AWS1); goes about the same, aside from smaller details like Vergil doesn’t absolutely wreck his shop fighting demons. Dante raised the Temen-Ni-Gru for the sole purpose of a good fight with Vergil and everything else came secondary. Lady probably doesn’t find Vergil as annoying as she did Dante, but her disdain for demons hasn’t changed; she likely gets the ‘Lady’ name from Vergil sarcastically calling her “Milady/m’lady”, with a bow and everything. Of course, it ends with the brothers fighting on that waterfall in Hell, and Dante diving deeper down (also one must imagine Vergil with a rocket launcher).

DMC5/AWS5; Event beats still mostly happen the same, but of course with changes that come with shifting Vergil and Dante like before.

A fun little fact is that Dante didn’t even realize that Nero may have been Vergil’s kid until he - or his human half, Tony, more accurately - saw photos of Nero in the Devil May Cry office, so he has a fun “oh fuck” moment. Tony also has Phantom in place of Nightmare, because I thought it’d be an interesting change-up. (One must imagine Tony riding on the back of a lava spider)

You have never seen Vergil pissed until you’ve seen him post-Nero Loses His Arm. He almost blows off Tony entirely to look for Nero’s attacker (Dante) and Yamato until Tony name-drops Dante, in which Vergil gets more pissed off because Of Course, Who Else Would Steal Yamato And The Devil Bringer. He has Rebellion, so when he meets Dante’s demon half, who I still have not named, he’s semi-goaded into trading swords back, “just like old times”. Of course, he gets thrashed and put into a month-long coma (One must imagine Vergil with long hair. And a cool bike.)

Nero, while still gunning for revenge against Dante’s demon, is more on the “I need to get my dad back alive” route. Vergil naturally does not call his son a dead weight, but Tony does (“We have to go, you’ll just be dead weight to him, kid!”) and yes, he still holds that to heart, because Tony dragged him there in the first place and is now calling him basically worthless. Nero’s arc is mostly the same, overcoming the insecurities that came with failing to protect those he cared about, but with the added twist of lessening Vergil’s burden. They’re family after all; Vergil is Sparda’s legacy, and Nero is Vergil’s.

On an aside, I think it’d be fun if Nico and Vergil met before the events of 5.

What does Vergil's dynamic with Trish and Lady look like?

Lady is the only person Vergil has debt to. He learned the hard way, through her, that the Sparda Family Gambling Luck is hereditary (and later advises Nero to never gamble against her, lest he loses his soul). They’re good friends, thanks to the horrible bonding experience that was the Temen-Ni-Gru, and he didn’t even need Morrison to call her up about the Qliphoth, he did that all himself. Lady is on Vergil’s short list of people he’d trust Yamato to in the event of something happening to him until he gave it to Nero.

Like Dante in canon, Vergil was brought to Mallet Island by Trish. They have about the same relationship as devil-hunting partners, and Trish is also on the aforementioned Yamato Inheritance List. Vergil likes to be prepared.

With the two of them, though they do buy clothes on his dime like they do Dante, Vergil doesn’t really mind, even if he is miffed at first - “You can just ask instead of robbing me” - because his money also goes towards more indulgent things like books and old records when he can afford it, and he usually can.

Is Vergil mean to Patty or is he nice to her? (<- The most important question!)

Vergil is nice to Patty in his own Vergil way. I don’t see him acting too differently than Dante does in the series, but as mentioned above, Vergil doesn’t mind spending a little extra cash on Lady and Trish, so he won’t mind doing it for Patty. He might just pull the “Later I’m busy” excuse so he can read instead.

On an angst note, Vergil did wonder what it would have been like to have a family with Calla, and since he was unaware of Nero’s existence, he finds himself trying to raise Patty as he would have his own child. Patty’s legal residence is still the orphanage, but Vergil allows her to stay as long as she wants at the Devil May Cry and she even has her own room (still does by the events of 5). Patty also doesn’t have to worry about cleaning up the shop since Vergil keeps it clean himself. They really only butt heads over Patty not knowing how Vergil likes his books organized, her borrowing a book and forgetting it somewhere, or her moving Vergil’s current read and not telling him first. The man’s protective of his books.

#angels will scream ( swap au )#📃 || txt#📩 || asks#📂 || au info#dmc#devil may cry#dmc swap au#vergil dmc#vergil sparda#dante dmc#dante sparda#nero sparda#nero dmc#lady dmc#trish dmc#patty lowell#dmc 3#dmc 5

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

OK. I watched the first chapter of Ever Crisis First Soldier episode 2 and of course I have thoughts.

Cut for spoilers and length.

Sephiroth has officially become a sympathetic character. I mean, he always was, but there's no doubt about it being official now.

The way he's acting toward people, pushing them away? He's not being arrogant or sullen or a dick. He's a sad, traumatized kid with crappy self-esteem. He's in pain and grieving the loss of Glenn, Matt and Lucia's friendship. He's trying to convince himself that he's a soulless machine because machines don't have to feel what he's feeling. He's pushing everyone away because he doesn't want to make the choice he had to make between saving Rosen and saving himself and his friends. If you're cold, calculating and ruthless, such choices are a lot easier.

Except he's not any of those things or he wouldn't be acting the way he is. He wouldn't care, but he obviously does here. If you push everyone away and keep them at arms length, it doesn't hurt so much when they inevitably leave.

Except Angeal ain't havin' none of that. He's gonna make Sephiroth his bro if it kills both of them. The dynamic between these two so far is

And you know it works, too, and at least they get ten good years as friends after that.

So yes, the Sephiroth from Episode 1 is still there, but he's depressed and traumatized. If he returned to Midgar between episodes, he probably got a good dressing down from the top brass at Shinra and suffered who knows what at Hojo's hands. He's hurting and I think on some level Angeal knows that, which is why he's trying so hard to break through.

Now let's talk about Sephiroth's dream. I hope that was just a regular dream and not Jenova fucking with him because that would be a real kick in the nuts. I'm going to say it was an actual dream triggered by seeing Alissa "Definitely Not Jenova" Goldie and her uncanny resemblance to Lucrecia. And he was handed an empty bowl and told it was pumpkin soup because he doesn't know what pumpkin soup looks like. He just knows it would be good and that his mama would make him some if she could.

And speaking of Definitely Not Jenova. Nope, definitely not Jenova or Hojo mindfucking him. Not at all.

But since I'm a glass half full kinda gal when it comes to these things, I'm considering another angle. Yeah, purple and purplish pink are colors associated with Jenova, but those lights swirling around Alissa remind me of will o' the wisps or spook lights. Depending on which culture's folklore you're looking at, these can represent elemental spirits, the fae or demons (demons as in "spirit that never walked the earth in physical form" and not the Biblical nasties).

What if a forest spirit or similar entity took an interest in Sephiroth and wanted to get a closer look to see what makes him tick? Such an entity wouldn't really understand humans, so throwing Hojo in his face wouldn't strike it as being cruel or malicious. It was just curious to see how he would react.

Yeah, it's probably Jenova. "Those you hate, those you fear, those you love" after all. The other idea is worth considering, though.

Some odds and ends:

*i'm glad that the existence of female SOLDIER operatives has been confirmed. Not sure how I feel about them having to wear coochie cutters while the guys get real pants, though.

*I wonder how Sephiroth will get Masamune from its namesake. I'm going to be optimistic and say Mr. Epic Eyebrows will deem him worthy of receiving it, because that's how that seems to be shaping up at first glance. My prediction is that Masamune will pop up at times throughout the story to observe Sephiroth and test his mettle. He already knows Sephiroth is worthy, and these interactions will serve to verify that.

*Bachman's kind of a pain in the ass, isn't he? Sephiroth isn't your show pony, dude. He didn't even know you'd be tagging along.

*EC is really playing up how innocent and good these kids were back in the day. Angeal certainly had it helped along by his upbringing, but it took work for Sephiroth to maintain his goodness. He's the way he is despite his childhood, not because of it.

*I know I sound like a broken record but bog standard villains just don't get that kind of development. We're not supposed to see them sympathetically. At least not the ones for whom a redemption arc isn't in the works. We're supposed to cheer when they get what they have coming in a movie or on a show. We're supposed to feel accomplished when we beat them as the final boss in the game. We're not supposed to see their inevitable defeat as the heartbreaking last act of a tragic life.

*EC took pains to make the connection between the purehearted pre-Nibelheim Sephiroth and the Sephiroth at the Edge of Creation. It's looking more and more to me like EoC Sephiroth and the Sephiroth menacing the party are two different people. Or, more accurately, two versions of the same person from two different universes/timelines and one of them isn't answering to Jenova anymore (if he ever did in the first place).

*I mean come on. The symbolism. The white feathers (which pop up all over Rebirth, too). This:

*That's not there by accident or because it looks cool. It's a single white wing to contrast with Jenovaroth's single black wing and highlight the differences between the two. The battle theme that plays during the behemoth fight is called White Winged Angel, fercryin' out loud! I will die on this hill.

That's all for now. Thanks for sticking around to the end of this if you did.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Michael Sheen says 'I'm not getting paid for this' as he launches most ambitious project yet

Fair play to Michael Sheen, he doesn't half set himself some challenges. After a decades-long career in Hollywood and British films and TV the 56-year-old Port Talbot raised star has embarked on his latest project - resurrecting Wales' national theatre company .

The RADA alumni clearly gets a huge buzz from creating, collaborating and acting with likeminded people. And his launch of the Welsh National Theatre this week is his most recent chapter in a series of projects intended to uplift and assist both the Welsh culture and people.

Since becoming a 'not for profit' actor on the back of selling his house in the US and the UK to bankroll the 2019 Homeless World Cup, held in Cardiff, he's fronted a Channel 4 documentary in which he used £100,000 of his own money to write off £1m worth of debts for a group of people in south Wales. This follows his 2017 move of setting up the End High Cost Credit Alliance to help people find more affordable ways of borrowing money. This year he's also launching book A Home For Spark The Dragon which he co-wrote and will help to raise funds for homelessness charity, Shelter, when it is released on June 5.

Now he, and a group of creative talent from across Wales have focused the spotlight on theatre in Wales after the Arts Council of Wales pulled all the funding for National Theatre Wales, which officially came to an end in December of last year.

Describing the launch of the Welsh National Theatre as a "new dawn for theatre in Wales" he, as its artistic director, also reflects on what a "huge loss" it would be to never have a national theatre in Wales again, or at least for a long time. It came to a head and the inspiration train was boarded at the rehearsals for Nye - the critically accclaimed original play about Aneurin Bevan and the creation of the NHS Sheen lead for the National Theatre (UK-wide) and Wales Millennium Centre last year.

Sheen told WalesOnline: "I was in a rehearsal room with a bunch of Welsh actors talking inevitably about how it looked like we had lost our National Theatre in Wales. There was a lot of talk of why that might have happened, the rights and wrongs of it and what went wrong - and all that kind of stuff.

"But ultimately, we were faced with the possibility of not having a National Theatre in Wales. It was such a tortuous process for us to get to that point that we started with in the first place. There was a real fear that maybe that would be it. That we would never have one again or it would take a very long time for that to happen."

He adds that it would be a huge loss to Wales if the country, famous for its performative heritage of the Mabinogion, Hedd Wyn, RS Thomas, Richard Burton and everything we have poured into 100s of years of culture, lost its country-wide outlet for theatre, acting, writing and directing - but he never had a plan to dive in - until he did.

"Even though it was not in any way something that I was planning to do, at a certain point in talking about it, I realised - 'well, if I don’t step up, how do I expect anyone else to?' he added, going onto speak about the challenges and how he's not getting any salary gain from the project. "The circumstances were so challenging I think - that it needed someone who had their own resources, brought certain qualities to the role that would allow it to happen. I’m not getting paid, I am able to collaborate and partner up with various organisations because of my work as an actor and my profile, I can get certain doors to open, I can get people on board - it felt like that’s what it sort of what people needed, otherwise it was going to be impossible.

"I think there was a window of time before the opportunity would dry up. That’s the why now. What made me take it on is ultimately, I heard myself arguing for what it should be and I was talking about something that only really me could do at this moment of time."

Writers Gary Owen, Russell T Davies and Time Price, directors Francesca Goodridge and CEO Sharon Gilburd, are already involved and the WNT will be building a network of talent scouts, too, who will be keeping an eye on youth, amateur and professional theatre productions. Dubbed "The Welsh Net" it's a play on the term "Welsh Not" which stifled Welsh expression and language - but the Welsh Net will champion new talent, voices and creativity.

"Part of the success of any organisation, I think, is collaboration and allowing people to take on responsibility and to grow and thrive in those situations as well as having a very strong vision at the heart of it. I hope I’m establishing certain kinds of values and beliefs and a way of looking at things and aspirations, but the team - it’s only going to work if the team is able to thrive in that," said the star who's known globally for his roles in Twilight, Frost/Nixon and Good Omens.

One other desire for the new national theatre company is that it will give space for actors, writers and directors to remain in Wales and still take on ambitious projects of scale. "One of the difficulties I think is bringing directors through, and being able to give directors, up and coming directors, the chance not to just work in studio spaces but on main stages and get them working on that kind of scale and level," he said, adding that Wales produces a strong stream of actors but many of them, including himself, leave to pursue their careers elsewhere.. He continued: "I think with writers, again, we’ve always had fantastic writers but having an incentive to write bold, ambitious plays about our country, that you know is going to get a chance of a production rather than writing a play that you know has no chance of being produced as it’s going to be too expensive."

Talking about bold productions, one of Welsh National Theatre's first productions will be an original play from Gary Owen, Owain & Henry, which promises to be an "epic" new play that focuses on the 15th century rebellion against the English crown by the outlawed prince, Owain Glyndŵr.

"There’s not many people who can put that on - and if the Welsh National Theatre is not going to put that on then no one is," Sheen, who will play Owain, mused. When asked where Owain Glyndŵr would rank in the list of iconic roles he has played, he said: "It’s not just the opportunity to play that role - but to have started a company that puts that production on and tell that story on the sort of scale that we’re looking at here, at the Millennium Centre, and to know that there’s an audience out there who might be finding out about this story for the first time... that’s going to start a conversation, so I’m really excited."

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

tuesday again 9/3/2024

having a lot of fun with toddler enrichment activities in this household, until we bit through the bag and the foil and the water and hated that experience

listening

fun citypop version of Good Luck Babe! by Amandumb and Sakura Wine, “ganbatte” scans to “good luck babe” SCARY well. this is both off a tiktok my best friend sent me and the spotify recommended weekly

youtube

-

reading

quite frankly this makes me nervous and i am backing up my blogs as we speak. i sort of believe them when they say that we won't see a difference on the front end, but this is a HUGE migration. SOMETHING is going to go not perfectly.

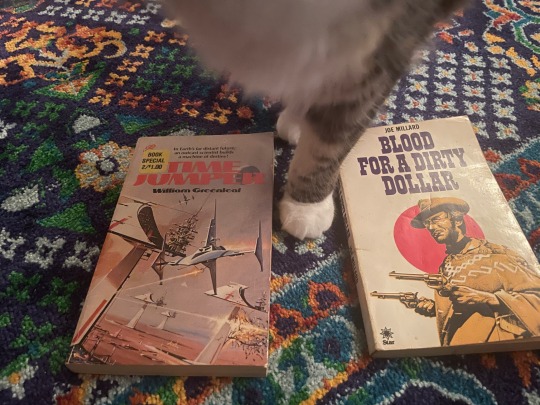

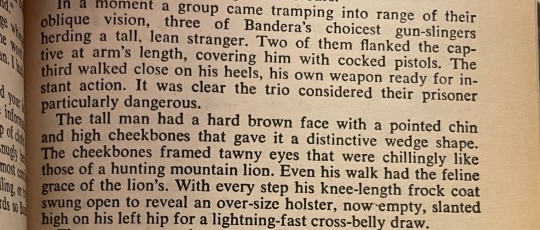

William Greenleaf's TIME JUMPER (1980, 224p) and Joe Millard (my beloathed)'s Blood For A Dirty Dollar (1980 European reprint of a 1973 American book, 156p). thank you philip. time jumper is from a thrift store somewhere (possibly from the free book shelf at the umass engineering library) and the cowboy book is from ebay. they lied about the condition and the heavy smoke smell so i ended up getting it for free :) in no world is that a Very Good condition book!!!

time jumper! i do not think the back cover blurb (below) is very accurate.

COMBINED DESTINIES! One Earth of the far future, city dwellers live in a technologically advanced environment, while bands of nomads barbarically hunt and farm the plains. Hidden within the city is Erin, a crazed scientist, who is constructing a timejumper. On the plains is a nomad boy who quests after the city's secrets. Unknown to both, an evil force works to keep them apart, for it knows that if they ever meet, a new Earth destiny would be inevitable!

i looooove a bubble city. i love long lingering shots of technology and city-scapes and city politics. i would not call the nomads barbarians, bc they are a trading society who set up crop irrigation in their seasonal fields and have a giant traveling library with card catalogue. i would also not call Erin crazed or hidden, bc he is the richest man in the city. reclusive, yes. single-minded, yes. pretty sane though. he is a little person and i think the book handled this fairly deftly for 1980? most of his obstacles are physical and not societal. finally, the evil force is not working to keep them apart bc it doesn't even know about the outside kid. they mostly just want to stop anyone from leaving.

now that we know the back blurb is lies, what's the deal with this book? mostly wrestling with how automation leads to a loss of purpose and flattening of culture, breaking cycles, cyclical natures of histories thereof, and repeating old sins. however, one of the more frustrating endings ive ever read with the very last paragraph containing the suicide of a minor character. we simply didn't fucking need that last paragraph.

i found the dialogue a little bland but book overall quite evocative. it felt like a sixties scifi show constructed from castoff theater sets. it felt like this screenshot from rollerball. a lot of shapes. a lot of giant gardens. a lot of flattened textures.

i also liveblogged the cowboy book here. we've previosuly looked at the one with the balloon and the jailbreak but this is the one with the mad englishman and the imported castle and the missing scientists. i love a description of Legally Not Lee van Cleef Because We Don't Have A Royalty Agreement

-

watching

X-Men: First Class (2011, dir. Vaughn) was way more fun than i was expecting??? it's fun to watch these with my bestie's husband who is a fairly intense x-men fan and Will pause the movie for several minutes to explain why a specific character's death was fucking bullshit or answer one of my stupid costuming questions

-

playing

the new mesoamerican fire-aligned nation of Natlan is out in genshin impact! VERY beautiful region even though i think it is a crime, to me personally, to show me a village of observation balloons and then tell me i can't actually go there for six weeks until the next patch.

this is a little bit more of a frustrating experience bc my tolerance for the least little thing going wrong is at record lows. once you hit 100% on a map region it feels more like a true 100% ing the area, which is a little scary bc this usually means you have anywhere from 10-20% more Stuff to do and find and collect. one quest is straight up bugged for me (very unusual) and i cannot get a specific mechanic (the yunkasaur, the little green pokemon lookin motherfucker above, flame spitting) to fire with any sort of accuracy. why have a sight and a center pip if you CANNOT aim it.

some parts of the map look a little more seussical than others.

to whoever made sure this observation balloon lined up with the window when you entered this waypoint building, i see you. thank you.

-

making

fallow week.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

jo march blossomed into a world where the end all for women is romantic love. a world where romance is prized and valued over friendships, sometimes even familial bonds, leaving those who do not dwell on such subjects to feel isolated. loneliness for jo is not the lack of a romantic partner. it is the cold tones of an empty attic that is haunted by the memory of one filled with the golden light of laughter from best friends and sisters. Not much has changed from past to now with the idea that love is all a woman is fit for.

it's seen as taboo for a strong coded female character to admit to wanting to be loved. years of cultural messaging made many women associate independence or female autonomy with being stoic, being emotionless, the weapon-wielding, frequently assumed heterosexual heroine should be alone or else she is risking exhibiting subordination or dependence. as if her coexistence with a man automatically diminishes her to a secondary character. the emotional burden of romance, in most mainstream media, is often carried by the female character. even in the arc of the male hero, his love interest is written solely to fulfill a function as a stepping stone to self-actualization or a precursor is his "man pain."

jo march is terrified of change. she finds no comfort in the future. jo would prefer to stay young and play in the attic till the children’s last breaths because what was can feel better than what is. however, change is forever linked to the wheel of time. suddenly, all this change came in rapidly in her life, as it does for all people when nearing the endings of childhood. everything is happening so quickly, and it can not be undone.

jo has a desperate desire- need to be alone, however not to be lonely. she is a woman fueled by passion, a passion that has consumed her entire being into a state of delusion. delusion in the sense that she lives in hopes that her and loved ones will stay youthful to play with her. jo's passion is bound by the inevitable, time. the little world that she had created with her sisters had shattered from the "curse" of aging. therefore, she actively tries to keep that same spark in her writing. her fantasy is better than the burden of reality. jo march is grieving the loss of innocence and childhood. as everyone else is going along with their individual lives, jo has either consciously or subconsciously chosen to never emotionally grow up.

(all based of the 2019 version)

#jo march#little women#little woman 2019#little woman movie#amy march#amy x laurie#laurie laurence#beth march#strong women#women#aromantic#strong female#strong female characters#character analysis

111 notes

·

View notes

Note

tarot face cards for Boyd’s,?

Steve Murphy: The Tower. Steve goes through the *wringer* in Narcos. Him and Connie uproot themselves from Miami for a country where they don’t know the language or culture. Connie’s cat is immediately cat-napped and cat-murdered. Steve gets kidnapped. His partner is soft-betraying him. Connie leaves him and takes their daughter. People he likes die!! He has to make a lot of unpleasant choices that often don’t turn out great for him! Upheaval, tragedy, violence, and pain is sort of the name of the game for him here!

Donald Pierce: The Moon. Pierce is very insecure! Holbrook says as much in several interviews; Pierce desperately wants to project an image of strength and confidence, and as the film continues that pretense is gradually stripped away. He’s deeply anxious – Rice kind of has to kick him into gear later on, and he’s also pretty damn intuitive – he *did* easily track Logan down, he puts together the nurses’ plan, and he figures out quick that Caliban is stalling them.

Cap Hatfield: The Hierophant. Although Cap might not seem like the classic choice for this, I absolutely think he fits! He’s got an unwavering dedication to his family (and the sort of patriarchal structure therein), and he absolutely shares in a lot of the traditional values of the era… and his family specifically. He’s sweet, but he’s their little foot soldier!

Clement Mansell: The Lovers. Clement is always searching for a connection, whether that’s with Sandy, or Sweetie, or Raylan, or Carolyn. (And he will absolutely make huge, impulsive decisions for the people he likes too.) Clement is *always* attempting to reach out - emotionally, sexually, physically. He’s not very successful, but not for a lack of trying!!

The Corinthian: The Devil. Beyond the obvious, that Corinthian in the waking world indulges his appetites to excess (and he’s absolutely very materialistic), there’s also the fact that his entire character arc is permeated by an extreme sense of hopelessness. He’s trying to claw his way to freedom the entire season, and not ever really gaining much ground. He’s dependent on other people helping him (John, Ethel, Rose), and he’s bound by the knowledge of what will happen when Dream inevitably regains his power and comes after him.

Eli Klaber: The Fool. Despite Klaber being… what he is, there is also an undeniable innocence to him. He’s very trusting, very naive, and very hopeful! He wants to go on a big adventure with his boss! And his trigger-happy nature absolutely plays into this too. He’s ~spontaneous~! I even think he can fit with this card representing a lack of commitments despite his extreme loyalty to Voller - he’s someone that seems adrift in every other aspect of his life, and (accordingly to Holbrook) joined up primarily because he didn’t have anything or anyone else.

Ty Shaw: Death. Ty has to deal with a very sudden loss, and he actually does handle it really adeptly. He vows to get revenge, but he states pretty clearly that he’s not gonna stop trying to enjoy himself and live life. He isn’t in denial about what’s happened - he does let go in a lot of ways, embracing Ben into the family, designating Abby’s room the new guest bedroom. And there’s something in that his story in the movie begins and ends with two different deaths.

Quinn McKenna: Justice. I get the sense that justice as a concept is something that’s very important to Quinn. He tends to be sort of rigid in his sense of right and wrong, and this results in him sticking to his guns even when it screws him over. He doesn’t like lying, he doesn’t like when people lie to him, and there’s something interesting that despite the way the Government involuntarily commits him, he *still* joins back up later. At the end of the day he believes in the rule of law… but it’s also never gonna let that stop him from doing what he thinks is just.

#the sun and the emperor were my other contenders for Ty!#curious what everyone else would choose!#boyd holbrook#donald pierce#the corinthian#steve murphy#ty shaw#quinn mckenna#cap hatfield#clement mansell#eli klaber

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ok, ok, ok, first, I need to preface. I love both Suvi and Amé as characters, and I love how Aabria and Erica are playing them. It’s meaty, it’s complex, it’s complicated, and they are crafting imperfect and really authentic characters, and clearly have so much trust between them as friends and scene partners to play in uncomfortable spaces, and it can’t be understated.

That said, OH MY GOD I JUST WANT THEM TO YELL AT EACH OTHER!!!! Both of them! Not just Suvi, who is most likely to let out her frustrations and her ire, but also Amé who is *least* likely to. They both just push so hard on each other’s wounds in a way that would be so much less painful were they not so deeply tied and if they didn’t care so deeply about each other.

Suvi’s need to externalize judgement, her need for control, and her need to confer blame (mainly on others) clearly are deep-seated symptoms of the trauma she endured as a child, losing her parents, and growing up in an environment and culture that is grounded in control, action, and externalizing judgement on others (e.g., guid mage vs citadel wizards, witches as lesser, spirits as resources, other nations’ magic as bad/wrong and other nation’s choices as justification for war and violent action - not saying in some cases unwarranted but just laying out the logic). The loss of her parents outside the citadel makes the world feel unsafe, and as a way to counteract that fear, she leans so hard into that control, blame, and judgement, and it pushes into Amé’s own wounds of shame, guilt, and people-pleasing, and lack of boundaries/inability to state her boundaries.

Amé grew up internalizing blame, other people’s emotions, and taking accountability and responsibility for others, in many cases, over her own needs and wants. Amé’s family gave her up because she was a witch. She blamed herself and holds still an incredible amount of shame simply for being who she *is*. The village treated her as an outsider, and her abandonment issues are clear triggers for her people-pleasing, her lack of/inability to state her boundaries, and why sometimes after relenting and following others’ course, it seems like she just snaps and has to do her own thing, the thing she’s been hinting at, quietly requesting, or wheedling for.

It was inevitable that in finding each other as young adults, our witch and wizard would be grinding and grating against each other’s rough edges. Suvi’s immediate stress response is fight, and Amé’s stress response is freeze and fawn. Those are hard to reconcile!

Without Amé clearly stating her needs, wants, and boundaries, Suvi has no real ability to map her control within the relationship, which would naturally lead to insecurity in it for her - the woman who needs to understand everything, black and white, no grey to muddy the waters. Without Amé to push back against Suvi’s judgements and blaming, Suvi further loses her openness to the world outside the citadel, instead, retreating into the comfort and safety the mentality of the citadel breeds.

Meanwhile, with Suvi’s judgements and ultimatums, it pushes Amé (who is so used to internalizing shame and reading others to navigate social dynamics in both her role as a witch and as a people pleaser) to shrink and apologize for her needs and wants, and to further take responsibility for the actions and behaviour of others (e.g., Ursulon’s safety after they were separated, after Suvi essentially sicc’ed the guard on them). At some point, the resentment will build so strongly it will become destructive, either to her or to someone else, but, and this is the thing that kills me, likely not Suvi, because she is the one that Amé is seeking approval from right now! She’s so deep in it, I worry that she won’t start asking if Suvi is the person she needs approval from, and why it matters so much for her. I worry that she will be able to intellectualize boundaries and psychological concepts, help others find their way to them, and yet never internalize them for herself.

The thing is, these two *need* each other! Suvi’s boundaries are so strong and reinforced, and she defends her personal sovereignty with tooth and claw - and my GOD does Amé need to learn how to do that, even if it will result in some inevitably tense and uncomfortable conversations for the both of them. Amé is a font of curiosity and non-judgement, of honest wonder, and what a joy that would be for Suvi to adopt - to be able to engage with the world not through a lens of fear or insecurity, because the world she has known has been dangerous, but instead through a lens of curiosity, because the world is surprising and joyful, and sometimes not having the answer means the journey of wonder gets to continue!

Can you imagine how beautiful it’ll be when they learn to balance each other? Amé, a confident witch who is not afraid to state her needs and make choices without guilt! Suvi, a wizard operating from curiosity, not fear, who lives not for the period at the end of a sentence, but the marginalia embroidering it!

Ah god, I’m not even through this episode and I had to take an hour to write my thoughts about it down. Gosh dang it Worlds Beyond Number, ya done got me by the throat on this one, y’all.

#worlds beyond number#the wizard sky#suvi kedberiket#aabria iyengar#quiddie#ame the witch#erica ishii#the wizard the witch and the wild one

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

During the '80s, mannequins set the beauty trends—and real women were expected to follow. The dummies were "coming to life," while the ladies were breathing anesthesia and going under the knife. The beauty industry promoted a "return to femininity" as if it were a revival of natural womanhood—a flowering of all those innate female qualities supposedly suppressed in the feminist '70s. Yet the "feminine" traits the industry celebrated most were grossly unnatural—and achieved with increasingly harsh, unhealthy, and punitive measures.

The beauty industry, of course, has never been an advocate of feminist aspirations. This is not to say that its promoters have a conscious political program against women's rights, just a commercial mandate to improve on the bottom line. And the formula the industry has counted on for many years—aggravating women's low self-esteem and high anxiety about a "feminine" appearance—has always served them well. (American women, according to surveys by the Kinsey Institute, have more negative feelings about their bodies than women in any other culture studied.) The beauty makers' motives aren't particularly thought out or deep. Their overwrought and incessant instructions to women are more mindless than programmatic; their frenetic noise generators create more static than substance. But even so, in the '80s the beauty industry belonged to the cultural loop that produced backlash feedback. Inevitably, publicists for the beauty companies would pick up on the warning signals circulating about the toll of women's equality, too—and amplify them for their own purposes.

"Is your face paying the price of success?" worried a 1988 Nivea skin cream ad, in which a business-suited woman with a briefcase rushes a child to day care and catches a glimpse of her career-pitted skin in a store window. If only she were less successful, her visage would be more radiant. "The impact of work stress . . . can play havoc with your complexion," Mademoiselle warned; it can cause "a bad case of dandruff," "an eventual loss of hair" and, worst of all, weight gain. Most at risk, the magazine claimed, are "high-achieving women," whose comely appearance can be ravaged by "executive stress." In ad after ad, the beauty industry hammered home its version of the backlash thesis: women's professional progress had downgraded their looks; equality had created worry lines and cellulite. This message was barely updated from a century earlier, when the late Victorian beauty press had warned women that their quest for higher education and employment was causing "a general lapse of attractiveness" and "spoiling complexions."

The beauty merchants incited fear about the cost of women's occupational success largely because they feared, rightly, that that success had cost them—in profits. Since the rise of the women's movement in the '70s, cosmetics and fragrance companies had suffered a decade of flat-to-declining sales, hair-product merchandisers had fallen into a prolonged slump, and hairdressers had watched helplessly as masses of female customers who were opting for simple low-cost cuts defected to discount unisex salons. In 1981, Revlon's earnings fell for the first time since 1968; by the following year, the company's profits had plunged a record 40 percent. The industry aimed to restore its own economic health by persuading women that they were the ailing patients—and professionalism their ailment. Beauty became medicalized as its lab-coated army of promoters, and real doctors, prescribed physician-endorsed potions, injections for the skin, chemical "treatments" for the hair, plastic surgery for virtually every inch of the torso. (One doctor even promised to reduce women's height by sawing their leg bones.) Physicians and hospital administrators, struggling with their own financial difficulties, joined the industry in this campaign. Dermatologists faced with a shrinking teen market switched from treating adolescent pimples to "curing" adult female wrinkles. Gynecologists and obstetricians frustrated with a sluggish birthrate and skyrocketing malpractice premiums traded their forceps for liposuction scrapers. Hospitals facing revenue shortfalls opened cosmetic-surgery divisions and sponsored extreme and costly liquid-protein diet programs.

The beauty industry may seem the most superficial of the cultural institutions participating in the backlash, but its impact on women was, in many respects, the most intimately destructive—to both female bodies and minds. Following the orders of the '80s beauty doctors made many women literally ill. Antiwrinkle treatments exposed them to carcinogens. Acid face peels burned their skin. Silicone injections left painful deformities. "Cosmetic" liposuction caused severe complications, infections, and even death. Internalized, the decade's beauty dictates played a role in exacerbating an epidemic of eating disorders. And the beauty industry helped to deepen the psychic isolation that so many women felt in the '80s, by reinforcing the representation of women's problems as purely personal ills, unrelated to social pressures and curable only to the degree that the individual woman succeeded in fitting the universal standard—by physically changing herself.

-Susan Faludi, Backlash: the Undeclared War Against American Women

#Susan faludi#female beauty#amerika#consumerism#performative femininity#cosmetic procedures#plastic surgery

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trope chats: immortality

The concept of immortality has fascinated humankind for millennia, often appearing in myths, folklore, religious texts, and modern literature. It evokes existential questions about the nature of life, death, and time, while exploring what it means to be human. As a literary device, immortality serves as a lens through which authors explore morality, purpose, and human frailty. However, it also comes with narrative risks, including the potential for repetitiveness or a lack of emotional stakes. Beyond literature, the immortality trope also plays a significant role in shaping societal beliefs, fears, and aspirations. This essay delves into the uses, pitfalls, and broader societal impact of the immortality trope, highlighting its continued relevance and complexity in storytelling.

The origins of the immortality trope can be traced back to ancient myths and religious stories. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, one of the oldest recorded works of literature, the hero seeks immortality after confronting the inevitability of death following the loss of his friend, Enkidu. His journey highlights the futility of escaping death, yet simultaneously reflects the enduring human desire to transcend it.

Similarly, in Greek mythology, figures like Tithonus and the gods themselves embody different aspects of immortality. Tithonus, granted immortality without eternal youth, serves as a cautionary tale about the consequences of living forever but decaying in body. The gods’ immortality, on the other hand, emphasizes their divine nature and separateness from the human condition. Immortality in these tales often reflects not just a desire for eternal life but a deeper exploration of what it means to live and die well, and how immortality complicates those values.

In many religious traditions, immortality is also connected to the afterlife. Christianity, Islam, and Buddhism each promise a form of life beyond death, whether it is eternal paradise, reincarnation, or enlightenment. The religious portrayal of immortality often carries moral undertones, where eternal life is a reward for virtuous living. Here, immortality is not inherently desirable but conditional, serving as both an incentive for moral behavior and a reflection of divine justice.

As literature evolved, the immortality trope took on new dimensions. In modern fiction, immortality is often examined through the lens of individual psychology, ethics, and social dynamics. The vampire genre, popularized by Bram Stoker's Dracula and modernized by works like Anne Rice's The Vampire Chronicles, explores the existential burden of living forever. Vampires, often cursed with immortality, grapple with isolation, moral decay, and ennui. In these stories, immortality becomes a prison rather than a gift, highlighting the human need for connection, change, and mortality.

More recently, works like Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go and The Age of Adaline reframe the immortality theme within the context of scientific advancement and human experimentation. These narratives question the ethical boundaries of life extension and the implications of such technological progress. For instance, in Never Let Me Go, the cloned characters are treated as vessels for immortality by others, emphasizing the dehumanizing consequences of pursuing eternal life through unethical means.

In speculative fiction, Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles and Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series engage with the idea of immortal civilizations or entities. These works extend the immortality theme beyond individuals, questioning whether societies and cultures themselves can achieve a kind of immortality through knowledge, science, or colonization of new worlds.