#and in any case: to use Richard as an example to generalize assumptions of the power other magnates held during Edward IV's reign

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"Because Richard (III) usurped the throne, his retinue is inevitably seen as inimical to the crown and therefore in an important sense independent of royal authority. In the context of Edward IV's reign, in which the retinue was created, neither assumption is true. The development of the retinue would have been impossible without royal backing and reflected, rather than negated, the king's authority. Within the north itself, Gloucester's connection subsumed that of the crown. Elsewhere, in East Anglia and in Wales, that focus for royal servants was provided by others, but Gloucester was still part of that royal connection, not remote from it. In the rest of England, as constable and admiral, he had contributed to the enforcement of royal authority. When he seized power in 1483 he did not do it from outside the prevailing political structure but from its heart."

-Rosemary Horrox, "Richard III: A Study of Service"

#richard iii#english history#my post#Richard was certainly very powerful in the north but to claim that he 'practically ruled' or was king in all but name is very misleading#his power/success/popularity were not detached from Edward IV's rule but a fundamental part/reflection/extension of Edward IV's rule#even more so that anyone else because he was Edward's own brother#there's also the 1475 clause to consider: Richard & Anne would hold their titles jointly and in descent only as long as George Neville#also had heirs. Otherwise Richard's title would revert to life interest. His power was certainly exceptional but his position wasn't as#absolute or indefinite as is often assumed. It WAS fundamentally tied to his brother's favor just like everyone else#and Richard was evidently aware of that (you could even argue that his actions in 1483 reflected his insecurity in that regard)#once again: when discussing Edward IV's reign & Richard III's subsequent usurpation it's really important to not fall prey to hindsight#for example: A.J Pollard's assumption that Edward IV had no choice but to helplessly give into his overbearing brothers' demands#and had to use all his strength to make Richard to heed to his command which fell apart after he died and Richard was unleashed#(which subsequently forms the basis of Pollard's criticism of Edward IV's reign & character along with his misinterpretation of the actions#of Edward IV's council & its main players after his death who were nowhere near as divided or hostile as Pollard assumes)#is laughably inaccurate. Edward IV was certainly indulgent and was more passive/encouraging where Richard (solely Richard) was concerned#but he was by no means unaware or insert. His backing was necessary to build up Richard's power and he was clearly involved & invested#evidenced by how he systematically depowered George of Clarence (which Clarence explicitly recognized) and empowered Richard#and in any case: to use Richard as an example to generalize assumptions of the power other magnates held during Edward IV's reign#- and to judge Edward's reign with that specific assumption in mind - is extremely misleading and objectively inaccurate#Richard's power was singular and exceptional and undoubtedly tied to the fact that he was Edward's own brother. It wasn't commonplace.#as Horrox says: apart from Richard the power enjoyed by noble associates under Edward IV was fairly analogous to the power enjoyed by#noble associates under Henry VII. and absolutely nobody claims that HE over-powered or was ruled by his nobles or subjects#the idea that Richard's usurpation was 'inevitable' and the direct result of Edward empowering him is laughable#contemporaries unanimously expected Edward V's peaceful succession. Why on earth would anyone - least of all Edward -#expect Richard to usurp his own nephew in a way that went far beyond the political norms of the time?#that was the key reason why the usurpation was possible at all#as David Horspool says: RICHARD was the 'overriding factor' of his own usurpation There's no need to minimize or outright deny his agency#as Charles Ross evidently did

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝑪𝑯𝑨𝑹𝑨𝑪𝑻𝑬𝑹 𝑶𝑼𝑻𝑳𝑰𝑵𝑬.

Richie Arden.

all questions answered with richie in his arc 1 verse (aka before the loss of his team (singh, yves, harris, and elis) and his subsequent assumed KIA status) in mind, and under the assumption that his noteworthy interpersonal relationships are only those of his "canon"

origins + family.

full name: Richard Edmund Arden IV

date of birth: 22 april

age: mid to late 30s is generally where he lands in threads (his post-military arc is more early 40s vibes i think)

social class: upper. old family money. gentry kid on both sides. he's not hiding it, but he's also not flaunting it, either, so many who don't know what they're looking for or looking at will miss it entirely

parents: The Duke of Hereford, and Baron Alvanley, [former] Colonel Richard Pepper Arden III, and Her Grace, the Duchess Katherine Arden

siblings: Margaret, married name Thomas, his younger sister by five years. it may not be immediately apparent, but he loves her dearly, and would kill for her without question. (worth mentioning here that Margaret has two children, Ada and Patrick, who Richie dotes on as though they are his own. he's as protective of them as he is his sister, if not moreso)

physical + appearance.

height: 6'5'' (196 cm)

weight: 105 kg, thereabouts / 16.5 stone / around 230 lbs

distinguishing features: the "glasgow grin" facial scarring on the right side of his mouth/face is probably one of the first things noticed, after his height/stature

hair color: sandy blond

eye color: blue

what do they consider their best feature?: mmmm is it too much of a cop-out to say his body? this is under physical/appearance but technically best feature could also be like, synonymous with best trait? in any case, Richie has worked very hard to maintain his physique, and knows just how appealing he looks to a not insignificant number of people. he cuts quite a figure, and he's proud of it

style of dress/typical outfit(s): most typically found in whatever uniform is appropriate for the day. CPU trousers (example, example) and combat shirts (example) are common staples of his day-to-day

jewelry? tattoos? piercings?: while he does technically own a few rings (like a signet ring or something) he never wears them. no piercings, but he does have a few tattoos. the only tattoo i'm certain of is the black and white compass he has inked on his right forearm, based on his lucky compass... he might be cheesy enough to have Ada's birthdate on him somewhere, but i'm not sure. he might also have the SAS motto (who dares wins / qui audet adipiscitur) on him somewhere (thanks young drunk self -insert eyeroll here-)

do they work out/exercise?: yes, daily and at length. a large part of any day not on deployment for any operator is keeping sharp enough to deploy at a moment's notice, and Richie is no exception

belief + intellect.

level of self esteem: very self-confident. i'd say from the outside, he can still regularly seem cocksure, even if he's not as loud about his self-confidence as he was when he was younger. (he was definitely cocky as a young man, but has mellowed into a more subtle confidence as he's aged)

known languages: (values based on this post / system): English (native), BSL (B2), Russian (B2), French (B1), Burmese (A2), Arabic (A2); He can manage street signs/basic directions in a few other languages based on deployments

gifts/talents: he has a knack for tracking and navigation, which is put to good use in his work

how do they deal with stress?: he typically smokes, runs, or tracks down the nearest punching bag, depending on location and/or time constraints

what do they do when upset?: it depends on the sort of upset. generally, he's prone to bottling it up and shutting down/shutting out others, though there's still evidence of the upset in the way he might grow pricklier and/or colder. i'd say there are two sides to any upset on Richie: there's the a louder, brasher version, and a quieter, more isolating one. there isn't a hard science to determining which version of upset you'll get from him, unfortunately. sometimes his temper is more visible, and other times the hurt flashes briefly before it's smothered by alarming (forced. an act. he's shoved his feelings down and away.) mildness.

do they believe in happy endings?: no

how do they feel about asking for help?: it depends on the kind of help he needs, and who his options are. he is far less willing to seek out personal help, and would rather the impersonal care of medical professionals and the like over colleagues or friends or family getting involved, for instance

optimist or pessimist: pessimist with the occasional optimistic lean, particularly [optimistic] when it comes to putting his trust in his team

extrovert or introvert: introvert. not a naturally social guy. which is actually really ironic because when he was younger he did very much enjoy going out or playing sports with his mates. somewhere along the way he just stopped seeking that out. maybe he stopped needing it? or maybe he'd never needed it and stopped wanting it, or decided somewhere along the way that it wasn't worth the effort anymore

leader or follower: leader (he has all the makings of being a leader of higher calibre than a lieutenant, he just really doesn't want the job)

makes decisions based mostly on emotions, or on logic?: logic. not a big feelings guy in general

spontaneous or planner: planner, though few plans survive contact with the enemy; he knows how to be spontaneous and adaptable

organized or messy: organized. he dislikes mess, though i'm not sure to what depth/extent

worrier or carefree: mmmm somewhere in the middle? can't spend your whole life stressing, but some fear/concern is healthy, he thinks

artistic?: no

mathematical?: quite. a not-insignificant portion of his job involves maths in one way or another, and he's got a knack for it, even if he wouldn't say as much

sex + intimacy.

current marital/relationship/sexual status: single, never been in a relationship more serious than a fuckbuddy, and sleeping around when he can/has the urge

sexual orientation (is it something they question or a secret): bi/pan, though he's not the labeling sort. it's never been something he questioned, and not something he ever put much care into keeping secret, in the sense that he was never trying to hide himself. he just also wasn't keen on the fallout of getting caught. he was aware of the rampant homophobia in many of the spheres in which he existed, and was careful, though still managed to get caught and expelled from two different boarding schools in his teen years for same-sex relations. in the military he flew just under the radar enough to not jeopardize his career, but he was never in denial about his interest in men, and never actively avoided pursuing male interests where they cropped up. it's largely been something he doesn't talk about because he's a private man

views on sex (one night stands, promiscuity, etc): what you're doing on your own time is none of his business, and vice versa. he's decidedly not the monogamous relationship type, or the relationship type at all, and gladly and regularly engages in casual, no-strings sex with whomever strikes his fancy

ever been in love?: no

do they fall in love easily?: no

do they desire marriage and/or children in their future?: absolutely not. he is very unlikely to marry for reasons outside of a relationship, and wholly uninterested in entering into a relationship, and thus wants nothing to do with marriage. he's actually sterile (both a matter of biology and procedure; he has always been sterile, and he had a vasectomy early in adulthood (like 18 or 19), because he didn't know he was sterile), though he's never had any interest in children

thoughts on public displays of affection?: no strong feelings either way

how do they show affection/love to their partner?: most often it would be gift giving and quality time

relationships.

social habits (popular, loner, some close friends, makes friends and then quickly drops them): i think his i-don't-give-a-shit, devil-may-care attitude would've roped him quite a bit of interest growing up, especially in an all-boys boarding school, and even through his early military career. so popular, for a long while too, actually. he was loud and proud and was far more social before he commissioned. he probably wasn't even interested in commissioning until he'd quieted. he was more of a small-group-of-friends kind of guy after that, though he could still be convinced, on occasion, to go out with people outside of that circle. and then his small group of friends (his team) didn't stick by him after he'd been through hell and back, and Richie became a proper loner. he's been much slower to trust and open up since then, though he's attached to his new team, much as he hadn't been expecting it

how do they treat others (politely, rudely, keep at distance, etc)?: kept at a distance. these days, it generally takes time and consistency for him to start warming up to someone. i'd say in general interactions with unknowns, he's succinct. he's not (generally speaking) intentionally brusque, though he may come across that way

confront or avoid conflict?: confront conflict, for better or worse

secrets.

dreams: mmmm ambiguity my beloathed. he doesn't... really have any personal ambitions. he might like to teach his niece and nephew how to drive some day? i think that's about the extent of it. and as for the sleep kind of dreams... mostly work-related. the ones he tends to remember are the nightmares, and those feature death or trauma

greatest fears: trauma triggers (: otherwise... god would he hate to outlive his sister and/or her kids. oh to that extent, maybe conflict making it back to the UK? he needs home to be Safe for them

biggest regret: dslfhsdhfs it might be not talking his sister out of marrying Bill. (he hates Bill; Bill hates him right back) but then he wouldn't have Ada and Patrick running around, so maybe he'll settle for convincing her to divorce the weasel-y little bastard instead

what they most want to change about their current life?: i don't know that there's anything that he does want to change. he's quite content with his life, actually. though he does periodically wish he could be in two places at once, because he'd like to see more of his niece and nephew

likes + dislikes.

hobbies: his lowest effort hobby is tinkering with his motorcycle. he also enjoys rugby, running, hiking, and hunting, the lattermost of which he does with his father on occasion. occasionally he can be coaxed into an evening poker night, and he does enjoy those

indoors or outdoors?: outdoors

favorite color: doesn't have one

favorite smell: on himself? some fresh and woodsy, but not overpowering. if he were to pick a scent for his home or office? honey and lemon tea, or the closest combination of scents to mimic walking through the woods of his family's estate

favorite and least favorite food: favorite, a fatty steak with a side of roasted potatoes and buttered vegetables. least favorite... I said mystery meat the last time this question came up in something, I think that might still hold true

coffee or tea?: tea, naturally

favorite type of weather: warm, with light clouds

favorite form of entertainment: the dumb shit that enlisted soldiers get up to that he has to pretend he hates as he breaks it up. out of like, traditional entertainment formats? televised sporting, maybe?

how do they feel about traveling?: god, given his job, he better at least tolerate it. jokes aside, he doesn't mind it. he enjoys the snatches of downtime he gets in foreign places. he wouldn't mind if traveling came without all that time sitting on his ass in whatever transport, though

what sort of gifts do they like?: i. don't know? i don't think he gets a lot of gifts, in any case, so i'm not sure he fully knows either. expensive alcohol is always a safe bet, but it's not very personal, even if you do happen to know his drink preferences

drugs + alcohol.

thoughts on drugs and alcohol: heavily disapproving of drugs, very much in a "why the fuck are you throwing your life away for a high" kind of way. not a heavy drinker, but a drinker nonetheless. more of a social drinker than anything

do they smoke? If so, do they want to quit?: yes he smokes, no he has no interest in quitting. he considers it to be one of his less dangerous indulgences in life

have they ever tried other drugs (which, what happened, consequences): i have been toying with the idea of making this idea canon, in which case he'd have "tried" a stimulant, and there was likely a rough crash once all was said and done; anyone who knew what he'd done wouldn't say anything about it, though, and anyone who didn't know would just assume he'd crashed from the adrenaline and stress. he's never engaged in, nor would he engage in, recreational drug use

do they have any addictions?: barring the smoking? no

other details.

most important/defining event in life to date: i would say his enlistment? his military service has defined the entirety of his adult life, so it feels apt

typical Saturday night: an actual Saturday? it's probably spent either on base or in the middle of fuckoff nowhere on deployment. but a proper night off? he might go out to a bar — he'll definitely go out if he's seeking sex, which does happen with regularity on his nights off

what is home like (messy, neat, sparse): sparse. this is a man who's spent his entire adult life in the military, ready to pack up and move at a moment's notice. i waffle sometimes on if he even has off-base accommodations at all; if he does, he's not the one furnishing them. most of what he owns is work-related in some fashion or another. he has some pictures and trinkets from deployments, a few civilian outfits, but that's about all by way of personal effects. it all easily fits in a single duffel bag

pets? if not, do they want any?: no and no. he doesn't mind cats or dogs, but he has little interest in taking one on, even if he could — and he most assuredly cannot, given the frequency with which he isn't even in the country

can they hold their breath for a long time?: yes

do they know how to swim?: yes. he learned to swim as a boy, which involved occasional summer trips to lakes and even a short bout on a swim team. he of course was expected to pass certain swimming tests as part of his military qualifications, and is SCUBA certified

can they cook (if so, how well and do they enjoy it)?: not anything more advanced than following whatever preparation instructions come on a can, or a box of pasta, or a frozen package of vegetables. he never learned — never felt the need to

1 note

·

View note

Text

Articles about Early Modern Witch Hunts

“Historians as Demonologists: The Myth of the Midwife-witch” by David Harley

“The Myth of the Persecuted Female Healer” by Jane P. Davidson

“On the Trail of the ‘Witches’: Wise Women, Midwives and the European Witch Hunts” by Ritta Jo Horsley and Richard A. Horsley

“Who Were the Witches? The Social Roles of the Accused in the European Witch Trials” by Richard A. Horsley

All of these articles are about, among other things, the myth that midwives were especially likely to be accused of witchcraft. This myth came about from taking the works of Early Modern demonologists, such as Heinrich Kramer, at face value and assuming that what he believed and that what a lot of clergy believed was identical to what everyone also thought and therefore that since the clergy was suspicious of midwives, lay people were as well.

Unfortunately, trial records don’t bear this myth out. There were some midwives accused, such as Walpurga Hausmannin and La Voisin, but both of these women seem to have been the exception rather than the rule and their cases were not typical of most witch trials; their relatively high-rank suggests that there were many factors behind their cases. We don’t know who first accused Hausmannin, but the accusations against La Voisin were driven by high-profile poisoning cases among the aristocratic elite of 17th century France and La Voisin was initially arrested on charges of poisoning. Linking poisoning with witchcraft was not uncommon, but it suffices to say that there was more afoot in the Voisin case than being a straightforward example of a midwife-witch. In total, Harley’s analysis of trial records finds only 14 midwife-witches, not all of whom were executed and sometimes their midwifery was rather incidental to the accusations of witchcraft.

What’s more, it turns that the assumption that Early Modern clergy (both Catholic and Protestant) and lay people had the same beliefs about witchcraft and magic seems entirely wrong. To make a long story short: the clergy were most interested in associating witches with cannibalism, pacts with Satan, Witches’ Sabbaths, and sex with demons. The peasantry, on the other hand, was most interested in magic that caused direct harm, such as causing a sudden storm or a child or animal to sicken seemingly without any explanation. This point on this divide was also made in this recent article, “The invention of satanic witchcraft by medieval authorities was initially met with skepticism” by Michael D. Bailey.

In a lot of cases, what lay people thought seems to have been rather more important to understanding the witch-craze, because the vast majority of Witch Trials were caused by accusations from people who were not members of the clergy and were generally of roughly the same social status as those they were accusing. (As in, most of the trials were the result of peasants accusing other peasants). Another point made in the Horsley articles is that while the line between beneficent and malevolent magic was sometimes blurry in the minds of lay people there does, nevertheless, seem to have been a line. By which I mean that the belief that all magic is inherently evil seems to most often been the viewpoint of the clergy. Harley, meanwhile, suggests that the clergy’s writings on midwives might have originated in the fact that midwives often did use quasi-magical techniques to promote easier childbirth and also possibly that midwives provided a rather neat and tidy explanation for where the supposed witches engaged in baby-killing rituals were getting the babies from without attracting a lot of attention. This aside, however, midwives, in fact, seem to have been highly-respected and valued members of their communities. Indeed, they were trusted enough to testify as expert witnesses for legal cases involving rape, illegitimacy, and/or infanticide.

The recent article by Bailey and both of the articles by Horsley also emphasize that witch hunts most often coincided with times of economic instability and thus, it is interesting to note that, aside from being mostly middle-aged or elderly women, a lot of accused witches were also beggars.

These works also discuss the Malleus Maleficarum and its often overstated influence on Early Modern witch trials. Thing thing about the Malleus is that it was originally written by a man named Heinrich Kramer as a way to vindicate himself as an Inquisitor and witch hunter after the cred-stripping debacle that had happened to him in Innsbruck in 1485. Namely, while running a trial against an accused witch named Helena Scheuberin and six other women, Kramer apparently spent most of his time asking Scheuberin endless questions about her sexual behavior. Georg Golser, the Bishop of Brixen, was not amused and had the trial shut down, the accused all freed, and Kramer expelled from Innsbruck.

Despite Kramer’s intentions, the Malleus was not initially an influential work; it was published during a lull in European witch-hunting and the peak of the Witch Hunt panic actually occurred around 140 years later. The lack of immediate popularity was probably due to, among other things, that the book was initially condemned by the faculty of Cologne due to objections over its demonology and recommended legal procedures. That Kramer was German and the heart of the Witch-Craze was in the German-speaking parts of the Holy Roman Empire is interesting, but it’s not enough to draw a one-to-one cause and effect, because there were other social, cultural, and political reasons for the German parts of the HRE produced so many witch trials.

962 notes

·

View notes

Text

“…The complex design of the Victorian house signified the changing ratio between the cultural and physical work situated there. With its twin parlors, one for formal, the other for intimate exchange, and its separate stairs and entrances for servants, the Victorian house embodied cultural preoccupations with specialized functions, particularly distinguishing between public and private worlds.

American Victorians maintained an expectation of sexualized and intimate romanticism in private at the same time that they sustained increasingly ‘‘proper’’ expectations for conduct in public. The design of the house helped to facilitate the expression of both tendencies, with a formal front parlor designed to stage proper interactions with appropriate callers, and the nooks, crannies, and substantial private bedrooms designed for more intimate exchange or for private rumination itself.

Just as different areas of the house allowed for different gradations of intimacy, so did the house offer rooms designed for different users. The ideal home offered a lady’s boudoir, a gentleman’s library, and of course a children’s nursery. This ideal was realized in the home of Elizabeth E. Dana, daughter of Richard Henry Dana, who described her family members situated throughout the house in customary and specialized space in one winter’s late afternoon in 1865. Several of her siblings were in the nursery watching a sunset, ‘‘Father is in his study as usual, mother is taking her nap, and Charlotte is lying down and Sally reading in her room.’’ In theory, conduct in the bowels of the house was more spontaneous than conduct in the parlor.

This was partly by design, in the case of adults, but by nature in the case of children. If adults were encouraged to discover a true, natural self within the inner chambers of the house, children—and especially girls—were encouraged to learn how to shape their unruly natural selves there so that they would be presentable in company. The nursery for small children acknowledged that childish behavior was not well-suited for ‘‘society’’ and served as a school for appropriate conduct, especially in Britain, where children were taught by governesses in the nursery, and often ate there as well. In the United States children usually went to school and dined with their parents. As the age of marriage increased, the length of domestic residence for some girls extended to twenty years and more.

The lessons of the nursery became more indirect as children grew up. Privacy for children was not designed simply to segregate them from adults but was also a staging arena for their own calisthenics of self-discipline. A room of one’s own was the perfect arena for such exercises in responsibility. As the historian Steven Mintz observes, such midcentury advisers as Harriet Martineau and Orson Fowler ‘‘viewed the provision of children with privacy as an instrument for instilling self-discipline. Fowler, for example, regarded private bedrooms for children as an extension of the principle of specialization of space that had been discovered by merchants. If two or three children occupied the same room, none felt any responsibility to keep it in order.’’

…The argument for the girl’s room of her own rested on the perfect opportunity it provided for practicing for a role as a mistress of household. As such, it came naturally with early adolescence. The author Mary Virginia Terhune’s advice to daughters and their mothers presupposed a room of one’s own on which to practice the housewife’s art. Of her teenage protagonist Mamie, Terhune announced: ‘‘Mamie must be encouraged to make her room first clean, then pretty, as a natural following of plan and improvement. . . . Make over the domain to her, to have and to hold, as completely as the rest of the house belongs to you. So long as it is clean and orderly, neither housemaid nor elder sister should interfere with her sovereignty.’’ Writing in 1882, Mary Virginia Terhune favored the gradual granting of autonomy to girls as a natural part of their training for later responsibilities.

…Victorian parents convinced their daughters that the secret to a successful life was strict and conscientious self-rule. The central administrative principle was carried forth from childhood: the responsibility to ‘‘be good.’’ The phrase conveyed the prosecution of moralist projects and routines, and perhaps equally significant, the avoidance or suppression of temper and temptation. Being good extended beyond behavior and into the realm of feeling itself. Being good meant what it said—actually transfiguring negative feelings, including desire and anger, so that they ceased to become a part of experience.

Historians of emotion have argued that culture can shape temperament and experience; the historian Peter Stearns, for one, argues that ‘‘culture often influences reality’’ and that ‘‘historians have already established some connections between Victorian culture and nineteenth-century emotional reality.’’ More recently, the essays in Joel Pfister and Nancy Schnog’s Inventing the Psychological share the assumption that the emotions are ‘‘historically contingent, socially specific, and politically situated.’’ The Victorians themselves also believed in the power of context to transform feeling.

The transformation of feeling was the end product of being good. Early lessons were easier. Part of being good was simply doing chores and other tasks regularly, as Alcott’s writings suggest. One day in 1872 Alice Blackwell practiced the piano ‘‘and was good,’’ and another day she went for a long walk ‘‘for exercise,’’ made two beds, set the table, ‘‘and felt virtuous.’’ Josephine Brown’s New Year’s resolutions suggested such a regimen of virtue—sanctioned both by the inherent benefits of the plan and by its regularity.

As part of her plan to ‘‘make this a better year,’’ she resolved to read three chapters of the Bible every day (and five on Sunday) and to ‘‘study hard and understandingly in school as I never have.’’ At the same time, Brown realized that doing a virtuous act was never simply a question of mustering the positive energy to accomplish a job. It also required mastering the disinclination to drudge. She therefore also resolved, ‘‘If I do feel disinclined, I will make up my mind and do it.’’

The emphasis on forming steady habits brought together themes in religion and industrial culture. The historian Richard Rabinowitz has explained how nineteenth-century evangelicalism encouraged a moralism which rejected the introspective soul-searching of Calvinism, instead ‘‘turning toward usefulness in Christian service as a personal goal.’’ This pragmatic spirituality valued ‘‘habits and routines rather than events,’’ including such habits as daily diary writing and other regular demonstrations of Christian conduct. Such moralism blended seamlessly with the needs of industrial capitalism—as Max Weber and others have persuasively argued.

Even the domestic world, in some ways justified by its distance from the marketplace, valued the order and serenity of steady habits. Such was the message communicated by early promoters of sewing machines, for instance, one of whom offered the use of the sewing machine as ‘‘excellent training . . . because it so insists on having every-thing perfectly adjusted, your mind calm, and your foot and hand steady and quiet and regular in their motions.’’ The relation between the market place and the home was symbiotic. Just as the home helped to produce the habits of living valued by prudent employers, so, as the historian Jeanne Boydston explains, the regularity of machinery ‘‘was the perfect regimen for developing the placid and demure qualities required by the domestic female ideal.’’

Despite its positive formulation, ‘‘being good’’ often took a negative form —focusing on first suppressing or mastering ‘‘temper’’ or anger. The major target was ‘‘willfulness.’’ An adviser participating in Chats with Girls proposed the cultivation of ‘‘a perfectly disciplined will,’’ which would never ‘‘yield to wrong’’ but instantly yield to right. Such a will, too, could teach a girl to curb her unruly feelings. The Ladies’ Home Journal columnist Ruth Ashmore (a pseudonym for Isabel Mallon) more crudely warned readers ‘‘that the woman who allows her temper to control her will not retain one single physical charm.’’ As a young teacher, Louisa May Alcott wrestled with this most common vice.

Of her struggles for self-control, she recognized that ‘‘this is the teaching I need; for as a school-marm I must behave myself and guard my tongue and temper carefully, and set an example of sweet manners.’’ Alcott, of course, made a successful career out of her efforts to master her maverick temper. The autobiographical heroine of her most successful novel, Little Women, who has spoken to successive generations of readers as they endured female socialization, was modeled on her own struggles to bring her spirited temperament in accord with feminine ideals.

So in practice being good first meant not being bad. Indeed, it was some- times better not to ‘‘be’’ much at all. Girls sometimes worked to suppress liveliness of all kinds. Agnes Hamilton resolved at the beginning of 1884 that she would ‘‘study very hard this year and not have any spare time,’’ and also that she would try to stop talking, a weakness she had identified as her principle fault.

When Lizzie Morrissey got angry she didn’t speak for the rest of the evening, certainly preferable to impassioned speech. Charlotte Perkins Gilman, who later critiqued many aspects of Victorian repression, at the advanced age of twenty-one at New Year’s made her second resolution: ‘‘Correct and necessary speech only.’’

Mary Boit, too, measured her goodness in terms of actions uncommitted. ‘‘I was good and did not do much of anything,’’ she recorded ambiguously at the age of ten. It is perhaps this reservation that provoked the reflection of southerner Lucy Breckinridge, who anticipated with excitement the return of her sister from a long trip. ‘‘Eliza will be here tomorrow. She has been away so long that I do not know what I shall do to repress my joy when she comes. I don’t like to be so glad when anybody comes.’’ Breckinridge clearly interpreted being good as in practice an exercise in suppression. This was just the lesson of self-censoring that Alice James had starkly described as ‘‘‘killing myself,’ as some one calls it.’’

This emphasis on repressing emotion became especially problematic for girls in light of another and contradictory principle connected with being good. A ‘‘good’’ girl was happy, and this positive emotion she should express in moderation. Explaining the duties of a girl of sixteen, an adviser writing in the Ladies’ Home Journal noted that she should learn ‘‘that her part is to make the sunshine of the home, to bring cheer and joyousness into it.’’ At the same time that a girl must suppress selfishness and temper, she must also project contentment and love. Advisers simply suggested that a girl employ a steely resolve to substitute one for the other. ‘‘Every one of my girls can be a sunshiny girl if she will,’’ an adviser remonstrated. ‘‘Let every failure act as an incentive to greater success.’’

This message could be concentrated into an incitement not to glory and ethereal virtue but simply to a kind of obliging ‘‘niceness.’’ This was the moral of a tale published in The Youth’s Companion in 1880. A traveler in Norway arrives in a village which is closed up at midday in mourning for a recent death. The traveler imagines that the deceased must have been a magnate or a personage of wealth and power. He inquires, only to be told, ‘‘It is only a young maiden who is dead. She was not beautiful nor rich. But oh, such a pleasant girl.’’ ‘‘Pleasantness’’ was the blandest possible expression of the combined mandate to repress and ultimately destroy anger and to project and ultimately feel love and concern.

Yet it was a logical blending of the religious messages of the day as well. Richard Rabinowitz’s work on the history of spirituality notes a new later-century current which blended with the earlier emphasis on virtuous routines. The earlier moralist discipline urged the establishment of regular habits and the steady attention to duty. Later in the century, religion gained a more experiential and private dimension, expressed in devotionalism. Both of these demands—for regular virtue and the experience and expression of religious joy—could provide a loftier argument for the more mundane ‘‘pleasant.’’

…The challenges of this project were particularly bracing given the acute sensitivity of the age to hypocrisy. One must not only appear happy to meet social expectations: one must feel the happiness. The origins of this insistence came not only from a demanding evangelical culture but also from a fluid social world in which con artists lurked in parlors as well as on riverboats. A young woman must be completely sincere both in her happiness and in her manners if she was not to be guilty of the corruptions of the age. One adviser noted the dilemma: ‘‘‘Mamma says I must be sincere,’ said a fine young girl, ‘and when I ask her whether I shall say to certain people, ‘‘Good morning, I am not very glad to see you,’’ she says, ‘‘My dear, you must be glad to see them, and then there will be no trouble.’’’’’

…No wonder that girls filled their journals with mantras of reassurance as they attempted to square the circle of Victorian emotional expectation. Anna Stevens included a separate list stuck between the pages of her diary. ‘‘Everything is for the best, and all things work together for good. . . . Be good and you will be happy. . . . Think twice before you speak.’’

We look upon these aphorisms as throwaways—platitudes which scarcely deserve to be preserved along with more ‘‘authentic’’ manuscript material. Yet these mottoes, preserved and written in most careful handwriting in copy books and journals, represent the straws available to girls attempting to grasp the complex and ultimately unreconcilable projects of Victorian emotional etiquette and expectation.”

- Jane H. Hunter, “Houses, Families, Rooms of One Own.” in How Young Ladies Became Girls: The Victorian Origins of American Girlhood

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The totality of things… is an exchange for fire, and fire an exchange for all things, in the way goods (are an exchange) for gold, and gold for goods.

Heraclitus

After the first coins were minted around 6oo BC in the kingdom of Lydia, the practice quickly spread to Ionia, the Greek cities of the adjacent coast. The greatest of these was the great walled metropolis of Miletus, which also appears to have been the first Greek city to strike its own coins. It was Ionia, too, that provided the bulk of the Greek mercenaries active in the Mediterranean at the time, with Miletus their effective headquarters. Miletus was also the commercial center of the region, and, perhaps, the first city in the world where everyday market transactions came to be carried out primarily in coins instead of credit. Greek philosophy, in turn, begins with three men: Thales, of Miletus (c. 624 BC-c. 546 BC) , Anaximander, of Miletus (c. 610 BC-c. 546 BC) , and Anaximenes, of Miletus (c. 585 BC-C. 525 BC)--in other words, men who were living in that city at exactly the time that coinage was first introduced. All three are remembered chiefly for their speculations on the nature of the physical substance from which the world ultimately sprang. Thales proposed water, Anaximenes, air. Anaximander made up a new term, apeiron, "the unlimited," a kind of pure abstract substance that could not itself be perceived but was the material basis of everything that could be. In each case, the assumption was that this primal substance, by being heated, cooled, combined, divided, compressed, extended, or set in motion, gave rise to the endless particular stuffs and substances that humans actually encounter in the world, from which physical objects are composed--and was also that into which all those forms would eventually dissolve.

It was something that could turn into everything. As [Richard] Seaford emphasizes, so was money. Gold, shaped into coins, is a material substance that is also an abstraction. It is both a lump of metal and something more than a lump of metal--it's a drachma or an obol, a unit of currency which (at least if collected in sufficient quantity, taken to the right place at the right time, turned over to the right person) could be exchanged for absolutely any other object whatsoever.

…

… Greek thinkers were suddenly confronted with a profoundly new type of object, one of extraordinary importance--as evidenced by the fact that so many men were willing to risk their lives to get their hands on it--but whose nature was a profound enigma.

David Graeber, Debt: The First 5000 Years

[Aristotle] … sees that the value-relation which provides the framework for this expression of value itself requires that the house should be qualitatively equated with the bed, and that these things, being distinct to the senses, could not be compared with each other as commensurable magnitudes if they lacked this essential identity. 'There can be no exchange,' he says, 'without equality, and no equality without commensurability' … Here, however, he falters, and abandons the further analysis of the form of value. 'It is, however, in reality, impossible … that such unlike things can be commensurable,' i.e. qualitatively equal. This form of equation can only be something foreign to the true nature of the things, it is therefore only 'a makeshift for practical purposes'.

…

However, Aristotle himself was unable to extract this fact, that, in the form of commodity-values, all labour is expressed as equal human labour and therefore as labour of equal quality, by inspection from the form of value, because Greek society was founded on the labour of slaves, hence had as its natural basis the inequality of men and of their labour-powers. The secret of the expression of value, namely the equality and equivalence of all kinds of labour because and in so far as they are human labour in general, could not be deciphered until the concept of human equality had already acquired the permanence of a fixed popular opinion. This however becomes possible only in a society where the commodity-form is the universal form of the product of labour, hence the dominant social relation is the relation between men as possessors of commodities. …

Karl Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, Chapter 1

The generalization of commodity production is only possible when production itself is transformed into capitalist production, when the multiplication and augmentation of abstract wealth becomes the direct goal of production and all other social relationships are subsumed to this goal. The “destructive power of money” which was the object of much criticism in many pre-capitalist modes of production (by many authors in ancient Greece, for example) is rooted precisely in this process of the capitalization of society as a result of the generalization of the money relationship.

Michael Heinrich, “A Thing with Transcendental Qualities: Money as a Social Relationship in Capitalism”

Aristotle contrasts economics with 'chrematistics '. He starts with economics. So far as it is the art of acquisition, it is limited to procuring the articles necessary to existence and useful either to a household or the state. … With the discovery of money, barter of necessity developed … into trading in commodities, and this again, in contradiction with its original tendency, grew into chrematistics, the art of making money. Now chrematistics can be distinguished from economics in that 'for chrematistics, circulation is the source of riches … And it appears to revolve around money, for money is the beginning and the end of this kind of exchange … Therefore also riches, such as chrematistics strives for, are unlimited. Just as every art which is not a means to an end, but an end in itself, has no limit to its aims, because it seeks constantly to approach nearer and nearer to that end, while those arts which pursue means to an end are not boundless, since the goal itself imposes a limit on them, so with chrematistics there are no bounds to its aims, these aims being absolute wealth. Economics, unlike chrematistics, has a limit ... for the object of the former is something different from money, of the latter the augmentation of money … By confusing these two forms, which overlap each other, some people have been led to look upon the preservation and increase of money ad infinitum as the final goal of economics' (Aristotle, De Republica, ed. Bekker, lib. I, c. 8, 9, passim).

Karl Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, Chapter 4

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

About Effective Dog Training and Obedience

Illustrated beneath are the basic strategies that should be followed when preparing you canine, regardless of which preparing technique you pick. Utilizing these strategies will help the preparation cycle hugely and guarantee that you get the most out your relationship with your canine.

Holding.

Likely the main piece of building a fruitful relationship with your canine is the affinity you can make with him, Rapport may be made on the off chance that you invest quality energy with your canine and become his dearest companion conversing with him-taking him out for long strolls, playing with him. This is the way in to a sound connection with your canine,

Consistency

Conveying steady clear messages to your canine will assist him with considering his to be as highly contrasting as opposed to different shades of dim. By reliable messages we mean the orders you use to prepare recognition and censure your canine ought to consistently be something very similar. It is significant that all individuals from your family are utilizing similar orders as you. At the point when first preparing your canine it will help if only one individual does the preparation. This is significant on the grounds that albeit the order might be a similar the non-verbal communication or the manner of speaking might be totally unique.

Timing

By timing we mean the measure of time permitted to elapse before your canine reacts (or not) to your orders and your recognition (or censure). This time ought to be no longer than 2 to 3 seconds. In the event that any more extended the odds are your canine won't connect your words with his activities. Recall that you canine's psychological capacity is equivalent to a baby.

By a similar taken it is significant that any actual revision to your canines reaction to you preparing order happens inside similar 2 to 3 seconds. On the off chance that for instance you have provided the order sit and the canine doesn't sit then you could push his back quarter down while providing the sit order

Repition.

Canines are animals of propensity and learn by repition. It might take a few repitions of a similar order before the reaction becomes embedded in the canines cerebrum and the activity you are attempting to show him becomes programmed. Your canine will likewise require boost meetings so the order or activity doesn't become lost during his life. You ought to consistently commend him when he accomplishes something right.

Meeting length

Keep all instructional meetings short and pleasant with the goal that you canine's fixation is kept up with all through. Quality not amount is the key, you ought to likewise consistently attempt to complete the instructional course on a positive note I you can.

Demeanor

Continuously be sensible in your assumptions for what your canine can accomplish. It requires some investment to get results. On the off chance that your canine experiences issues in getting a specific order attempt and take a gander at why he is experiencing issues. Return to it one more day.

Recognition.

Continuously use acclaim at whatever point you canine has effectively finished an activity. This ought to likewise be done when your canine has done the ideal demonstration (recall the segment on planning) When conveying the applause gaze straight at him with the goal that he comprehend the association between the voice or contact and his activity. Convey the acclaim either verbally or with the hand by either tapping or stroking him.

Eye to eye connection.

Utilizing eye to eye connection can be more viable than utilizing the verbally expressed word particularly in case there is a nearby connection between the canine and proprietor. On the off chance that a canine wishes to speak with you he will gaze straight at you attempting to peruse your expectation.

Hand signals

Utilizing explicit hand signals while simultaneously addressing your canine can be a successful method of preparing you canine. It will be valuable in getting youthful canine to react at significant distances and you can ultimately stop the verbal orders with the goal that he reacts to the hand signal as it were. Give hand signal before or more the canine's head as this is in their line of vision.

Voice signals

Canines are known for their insight however they are simply ready to comprehend a couple of words, even those are a greater amount of a relationship between the sound you make and the activity the canine has figured out how to react to the sound with.

Utilize one order for one activity and articulate the order with a similar manner of speaking. You should acquire your canines consideration by saying his name prior to beginning an order.

Understand that you canine won't see all that you say and may misconstrue the importance of what you say. For instance on the off chance that you have prepared you canine with the "down" order he might well in case he is perched on the furniture not react to the order "get down" as he has just perceived the word down.

Discipline and remedy

It is significant that the canine considers you to be the pack chief. In the wild if a canine misbehaves the"alpha"dog will rebuff or chide it right away.

For general defiance utilize the "Caution No Command" strategy. This strategy has three stages that you take when your canine doesn't react as you wish.

Use something to alert your canine, for example, a spurt from a water gun or shaking a stone filled can. Ensure that you do this while he is in the demonstration of acting up.

Simultaneously say so anyone might hear No or Bad .Use a harsh voice so your canine perceives the distinction in tone from your ordinary voice .It is significant that your voice amendment is true and that the conveyance is predictable so the canine partners the brutal words or words with halting the conduct.

Then, at that point divert your canine with an order. Sit and stay is an awesome decision.

A check collar offers a simpler yet more actual approaches to give an adjustment.

A third alternative is banish your canine from the pack. In the wild the alpha canine would snarl and pursue the culpable canine away from the pack. The alienated canine would not be permitted once again into he pack until the alpha canine lets him. You could do this by snarling at your canine and pursuing him away from the family region say outside to the nursery.

Hello my name is Richard. I live in the UK with my significant other and girl and our pet canine "Ollie". I have been a canine sweetheart for various years. I have contemplated canine conduct essentially to upgrade our relationship with our pet yet additionally in light of the fact that I feel that most conduct issues are handily kept away from if the right preparing strategies are taken on in any case.

Check out https://bit.ly/2YfiqEZ for your other successful training tips.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 1 - Impressions of Anandamayi

“This incident, which I have reconstructed from the diary account of Didi Gurupriya Devi, Anandamayi's lifelong chief assistant, typifies the paradoxical status of a figure such as Anandamayi in modern Indian society. She is so unusual that there is no woman, not even an example known to us from the past, with whom she can be compared except in the vaguest of terms. We are baffled, as were the inhabitants of Bhawanipur, by her unplaceability. A strange event was visited upon the good peasants of that nondescript village—an eruption of the sacred which they would puzzle over for many years. In her speech, mode of dress and features, the lady with the airs of a holy person seemed to belong nowhere or everywhere.

Nowadays, we indiscriminately call such a charismatic figure a Guru, without being any too clear what that term means other than, perhaps, somebody with pretentious claims to spiritual wisdom. We relegate all Gurus to a dubious category of exotic, perhaps dangerous, cults. Gurus have been seriously discredited by recent scandal and tend to be treated with a degree of caustic suspicion. We recall Bhagavan Rajneesh—he of the 87 Rolls Royces—or various cult leaders whose followers committed mass suicide. We look on them as sinister and mendacious personalities who take backhanders from politicians or seduce the daughters of our friends.

Traditionalists point out that people like Sri Aurobindo, Krishnamurti, Swami Ramdas and Swami Shivananda, Mother Meera, Sai Baba, and Meher Baba are not Gurus at all but a hybrid phenomenon catering to foreigners.

Certainly, the glamorized deluxe ashrams which have sprung up in recent decades are a far cry from the modest pattern of the age-old guru-shishya relationship of master-disciple tutelage; yet this ancient system survives, for example, in the teaching of classical music and dance.

Throughout Indian history, this pattern of instruction ensured the transmission of knowledge from one generation to the next. In the case of Anandamayi who did not herself have a Guru, but was self-initiated, the traditional model of the teacher and the taught has, in certain respects, taken on new life, but in other equally important respects, she radically departed from tradition.

Her role as a revered Brahmin divine was by no means orthodox since this was a departure from the traditional status parameters of the married woman; further, for some 50 years as a widow and thus a member of the lowliest rank of Indian society, she was at the same time one of the most sought after of all spiritual teachers.

Yet again, she revived the old custom of the gurukul, an ancient style of schooling for both girls and boys at her ashrams. Until almost the very end of her life she could not be classed as a Guru in a technical sense; for a Guru is one who gives Diksha to disciples or initiation by mantra.

Nevertheless, in the more general and metaphorical sense of spiritual teacher, she was certainly a Guru, one of the greatest and the most respected of her time. In addition, she was indeed the Guru to many advanced sadhakas spiritual practitioners.

For them, she was everything that the Guru traditionally should be a perfect vehicle of Divine Grace. There is a section in the excerpts from the discourses of Anandamayi included here where she comments at length on the spiritual meaning of the Guru. The true Guru is never to be regarded by the disciple as merely human but as a divine being to whom he or she surrenders in total obedience.

The disciple places himself in the hands of the Guru and the Guru can do no wrong.

Moreover, from the point of view of the Guru's disciples, the Guru is the object of worship. Obviously so serious a commitment is hedged about with all manner of safeguards, for the Indian is as aware of the perils inherent in such a position of absolute authority as is any skeptical outsider—rather more so, in fact, for much experience about the dynamics of the guru-shishya bond has been amassed over the millennia of its existence.

How could such adulation, such assumption of control over another's destiny, fail to turn the heads of all upon whom this mantle of omniscience falls? Everything depends on the closely observed fact that there are a few rare individuals at any one point in time who are so devoid of ego that no such temptation could possibly be felt. Egolessness is the sine qua non of the Guru.

For an Indian, submission to tutelage by a Guru is but one among many possible routes to salvation or Self-Realisation. In the case of Anandamayi, it has become obvious, indeed widely known, that we are dealing with a level of spiritual genius of very great rant, Her manifestation is extraordinarily rich and diverse.

She lived for 86 years, had an enormous following, founded 30 ashrams, and traveled incessantly the length and breadth of the land. People of all classes, castes, creeds, and nationalities flocked to her; the great and the good sought her counsel; the doctrine which she expounded came as near to being completely universal as is attainable by a single individual.

Though she lived for the good of all, she had no motive of self-sacrifice in the Christian sense: "there are no others," she would say, "there is only the One". She came of extremely humble rural origins, though from a family respected over generations for its spiritual attainments.

In the course of time, she would converse with the highest in the land, but draw no distinction between the status of rich and poor, or the caste and sectarian affiliations of all who visited her. She personified the warmth and the wide toleration of the Indian spiritual sensibility at its freshest and most accessible.

The fact that she was a woman certainly accentuates the distinctive features of her manifestation. Female sages as distinct from saints capable of holding sustained discourse with the learned are almost unheard of in India. Her femininity certainly imparts to the heritage of Indian and global spirituality certain qualities of flexibility and common sense, lyricism and humor not often associated with its loftiest heights.

Her quicksilver temperament and abundant Lila sacred play are in stark contrast with the serenity of that peerless exemplar of Advaita Vedanta, Sri Ramana Maharshi of Tiruvannamalai, the quintessence of austere stillness. That a woman of such distinction and wide-ranging activity should emerge in India in the 20th century, the century of world-wide feminism and reappraisal of feminine phenomenology hardly seems a coincidence. The Guru, by definition, reflects the profoundest and most urgent needs of all followers. While the Guru incarnates the wish-fulfilments of a myriad devotees, he or she also extends, expands and elevates to new and unfamiliar sensitivity those who take heed.”

—Anandamayi, Her Life and Wisdom by Richard Lannoy Chapter 1, Pages 6-7

#Anandamayi Ma#Sri Anandamayi Ma#Ananadamyi Her Life and Wisdom#Richard Lannoy#book quotes#quotes#spiritual quotes#Anandamayi quotes#self realization#enlightenment#spirituality#guru#devotees#umi ananda

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

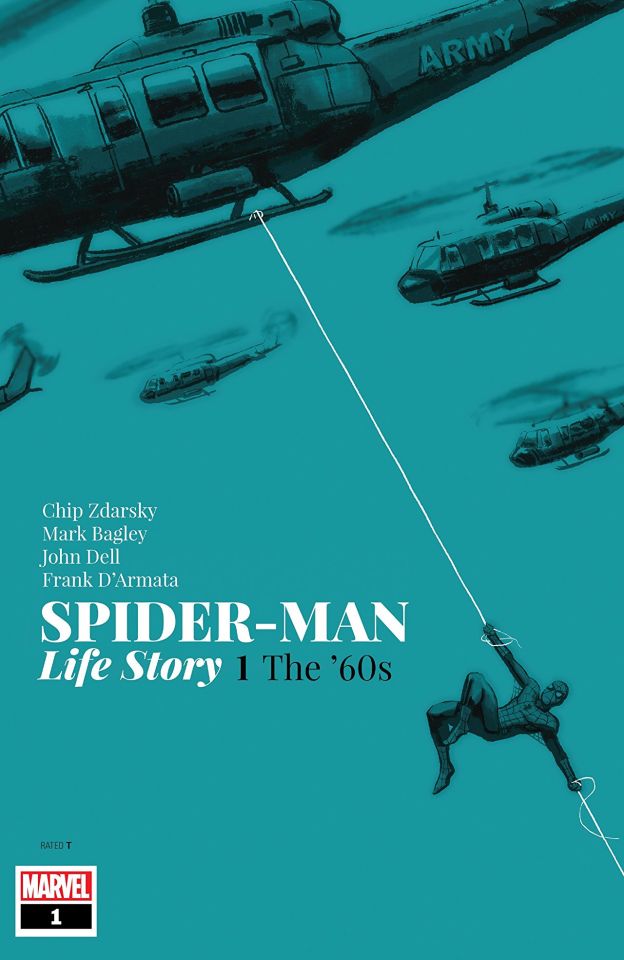

Spider-Man Life Story #1 Thoughts

Well...this was odd.

I have profoundly mixed feelings about this story.

That is owed to this comic being a collision of so many different things.

It is a period piece. But period piece that only half uses the period.

And I mean that on two levels.

It’s a period piece in the more general sense because it is set in the 1960s. But it is also a Spider-Man period piece because it uses 1960s Spider-Man continuity.

And it only half uses both in both cases.

Basically this issue was Chip Zdarsky’s Spider-Man AU fanfic that is a giant what if deviating from the Romita era...that is also set in the 1960s.

That is honestly the only way I could sum up this story. And by the looks of it things are going to get MORE complicated next issue because we move into the 1970s which implies each issue will be set in a different decade and this is confusing because if Spider-Man’s history played out in real time starting in 1962 then modern stories would only maybe be in the early 1980s.

Basically I guess this is more a general What If series that each issue will be talking up topical issues from each decade.

Which is seriously NOT how this mini was advertised to readers so that sucks hard.

But okay AS what it actually is trying to be...is it any good.

The answer is...kind of.

There is more good than bad.

Now you all know I do not like Zdarsky’s work on Spider-Man, so when I say there is more good than bad I’m not damning with faint praise.

On a general sense, the pacing is REALLY good. A lot of story happens in one issue. Granted it’s extra length so maybe that is why. The dialogue is perfectly fine, nothing rings untrue to the characters’ voices (except Gwen but we’ll get there). There is a respectable amount of introspection and exploration on Peter’s part and this is THE best Mark Bagley art in a very long time.

IIRC Mark Bagley once said that when he did the Ultimate Clone Saga and got to draw Richard Parker, he modelled him upon Gil Kane’s take on Peter Parker from the 1970s, and felt he got closer to that than he was trying to do in his 1990s work. You can very much feel that here now that he’s drawing Peter in literally the same setting that Kane drew him in.

Okay lets talk about other things that worked.

· Flash’s characterization and Peter’s relationship with him. It felt very realistic in spite of not being how things played out in the original comics

· Norman Osborn was very much in character in being devious and frightening

What didn’t work.

· Peter’s quick assumption of Norman’s amnesia. He kind of just presumes Norman has lost his memory on the basis of little evidence. Now granted his spider sense later corroborates this, but it’s still...kind of lame. Especially compared to the original story in ASM #40 wherein Peter figured Norman lost his memories because he was referencing an event from his past that he’d just finished relaying to Peter.

· The blurb at the start of the issue says Peter was 15 when he got his powers in 1962. And then we cut to 1966 where Peter says that this happened 4 years ago. On the very next page he claims he has a year left of collage. Er...what? Maybe I’m out of the loop on the American college system (in the 1960s) but if Peter was 15 in 1962 and it’s 4 years later then he’d be 19. Collage lasts four years meaning Peter wouldn’t be graduating for another 2-3 years (depending upon how close he is to turning 20). He should be in his FIRST year of college, 1965-1966, and would be graduating in 1969, the school year beginning in 1968. WTF?

· Gwen. Zdarsky has constructed a conundrum for himself here. This is the Romita era Gwen but with shades of Ditko Gwen but also shades of more modern revisionist versions of her and Emma Stone and also he’s now taking her in a MASSIVE deviation from the established Spider-Man history. It’s all a mess, and speaks to where Zdarsky’s shipper flag is planted btw.

· Peter’s attitude to Flash at his leaving party. In the original story, ASM #47 Peter in a wonderful moment of maturity held no grudge against Flash and wished him well sincerely. There was no ‘triggering’ on his part.

· The focus upon other superheroes like

· Frankly the fact that this is not clearly either a What If deviation from established history or a true blue period piece using the established lore.

And really that is THE big dilemma with this story. It’s not really committing to being one of those things or the other and is as a result kind of compromising both things.

It’d be one thing if Spider-Man’s history was going in starkly different directions as a RESULT of Zdarsky using the historical setting, like if Peter was drafted for example.

But that isn’t what happens. Gwen finding out Peter is Spider-Man and Peter turning in Norman Osborn are things that could have happened in any contemporary What If issues (if What If was around back then).

And it’s not that these are uninteresting deviations to explore, but they feel undercooked because the book is also examining Peter’s introspection about joining up to fight in Vietnam. And THAT stuff is really interesting too, the discussion with Flash and Captain America serving as opposing arguments for Peter’s decision is REALLY good.

But again it feels undercooked because we’ve got this plot about Norman Osborn knowing Peter is Spider-Man brewing.

And the thing is I can’t decide if it’s a case of the story itself being at fault or the advertising for it being flawed.

Let’s put aside discussions about whether the story being Spider-Man’s history just presented in real time would’ve been better than this or not.

The fact is it WAS sold to readers that way so when you view it through that lens all the What If deviations seem weird and out of place, like distractions.

But hypothetically if this was just advertised as a What If mini ‘What if Peter turned in Norman Osborn and Gwen found out he was Spider-Man before she died’ then the focus upon Vietnam would’ve felt much the same.

But I don’t know if the series advertising EXACTLY what this mini seems to be would’ve mitigated this sensation from the reader. Or if the story itself is just really just two types of stories glued together.

I suspect it actually is the latter though for two big reasons.

The Vietnam plotline places a lot of focus upon Captain America and Iron Man. Their conflict is in fact the shocking cliffhanger of the entire issue. So you know...something that isn’t about Spider-Man himself. That felt more like Zdarsky trying to do Watchmen but in the Marvel universe. Which gets complicated because that opens up a whole can of worms for the relative realism of the MU, not least of which being how could the heroes ever allow things in the war to get to the point that it did.

The other reason is that the deviations from established history aren’t done the way of a traditional What If, wherein the in-universe history is identical up to a certain point then a single change sets off a new direction.

Here Zdarsky is just remixing various different elements from Romita Spider-Man to create an impression of that era and then deviating from the ‘general knowledge’ of that era.

Norman dropping Harry off at school cribs from ASM #39, Norman’s amnesia cribs from ASM #40, Flash’s party cribs from ASM #47, the Scorpion and Spider Slayer stuff treats ASM #20 and #25 as big parts of the past but the threat of Jameson’s exposure cribs from Stern’s 1980s run. Norman wanting Peter as his heir cribs from Revenge of the Green Goblin in the 2000s.

But these elements, much like Spider-Man: Blue, are not remixed in a way that chronologically line up with how things happened. They’re all jumbled together so now Norman found out who Peter was (somehow?) but kept that in his back pocket to bring it up at Flash’s party and then announced he wanted Peter as his heir.

It’s all so...weird.

Look it isn’t an uninteresting what if but it’s also like...just a fanfic basically.

Not badly written fanfiction but it’s also like...what point is there to this really besides BEING Zdarsky’s fanfiction?

Another problem is that this story, along with not fully committing to the period piece aspect, simultaneously plays things with an intrusive degree of hindsight and imposes revisionism.

I’ve already spoken about this with Gwen but it’s also true with Harry and Norman’s relationship being cribbed from the Raimi movies the incredibly obvious ‘Norman will kill Gwen!!!!!!’ foreshadowing along with the ‘Professor Warren is a bad guy’ stuff; to say nothing of how Warren’s character design is inaccurate to the period.

That stuff imposes a present day hindsight of the Romita era whilst also overlays that with truisms brought about by adaptations being in the zeitgeist.

This applies to the Vietnam war stuff too. The book frames the war in a way that we look back upon it as opposed to framing it the way people in 1966 America probably actually viewed it. The final page is the biggest example of this.

Finally...didn’t we JUST see this from Zdarsky with his time travel arc in Spec?

Like wasn’t this a very similar idea. Spider-Man’s history but deviated because Norman Osborn’s identity is exposed differently and Peter and Gwen wind up as endgame?

Over all I can’t say that I disliked this. But nor can I say I was that thrilled with it. It’s not what we were promised and honestly...what we were promised sounded a lot more compelling. Moreover there are much better examples of period piece superhero stories out there.

· Spider-Man Blue frames the early Romita issues the way they might’ve happened in the 1960s as they existed rather than Marvel universe 1960s

· ASM Annual 1996 is DeFalco, Frenz and Romita Senior presenting an untold tale so good it could be downright mistaken as being MADE in the 1960s

· Busieck’s seminal Untold Tales of Spider-Man series as a whole

· The last 2 issues of Webspinners by DeFalco and Frenz which serve as a lost arc from their 1980s era

· X-Men: Grand Design

I think this is something you just gotta pick up and taste for yourself, but again...just be aware this isn’t what it was advertised as.

#Chip Zdarsky#Spider-Man#Mark Bagley#Gwen Stacy#Peter Parker#Captain America#Iron Man#Steve Rogers#Norman Osborn#Green Goblin#John Romita Senior#John Romita Sr.#John Romita Sr

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jeffrey Epstein and When to Take Conspiracies Seriously https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/13/opinion/jeffrey-epstein-suicide.html

When you have the #POTUS pushing conspiracy theories about the former president we are in DANGEROUS territory. The #ClintonBodyCount is being pushed by Russia and bots. We can't jump to conclusions until we have the facts. BEWARE

Jeffrey Epstein and When to Take Conspiracies Seriously

Sometimes conspiracy theories point toward something worth investigating. A few point toward the truth.

By Ross Douthat | Published August 13, 2019 | New York Times | Posted August 13, 2019 |

The challenge in thinking about a case like the suspicious suicide of Jeffrey Epstein, the supposed “billionaire” who spent his life acquiring sex slaves and serving as a procurer to the ruling class, can be summed up in two sentences. Most conspiracy theories are false. But often some of the things they’re trying to explain are real.

Conspiracy theories are usually false because the people who come up with them are outsiders to power, trying to impose narrative order on a world they don’t fully understand — which leads them to imagine implausible scenarios and impossible plots, to settle on ideologically convenient villains and assume the absolute worst about their motives, and to imagine an omnicompetence among the corrupt and conniving that doesn’t actually exist.

Or they are false because the people who come up with them are insiders trying to deflect blame for their own failings, by blaming a malign enemy within or an evil-genius rival for problems that their own blunders helped create.

Or they are false because the people pushing them are cynical manipulators and attention-seekers trying to build a following who don’t care a whit about the truth.

For all these reasons serious truth-seekers are predisposed to disbelieve conspiracy theories on principle, and journalists especially are predisposed to quote Richard Hofstadter on the “paranoid style” whenever they encounter one — an instinct only sharpened by the rise of Donald Trump, the cynical conspiracist par excellence.

But this dismissiveness can itself become an intellectual mistake, a way to sneer at speculation while ignoring an underlying reality that deserves attention or investigation. Sometimes that reality is a conspiracy in full, a secret effort to pursue a shared objective or conceal something important from the public. Sometimes it’s a kind of unconscious connivance, in which institutions and actors behave in seemingly concerted ways because of shared assumptions and self-interest. But in either case, an admirable desire to reject bad or wicked theories can lead to a blindness about something important that these theories are trying to explain.

Here are some diverse examples. Start with U.F.O. theories, a reliable hotbed of the first kind of conspiracizing — implausible popular stories about hidden elite machinations.

It is simple wisdom to assume that any conspiratorial Fox Mulder-level master narrative about little gray men or lizard people is rubbish. Yet at the same time it is a simple fact that the U.F.O. era began, in Roswell, N.M., with a government lie intended to conceal secret military experiments; it is also a simple fact, lately reported in this very newspaper, that the military has been conducting secret studies of unidentified-flying-object incidents that continue to defy obvious explanations.

So the correct attitude toward U.F.O.s cannot be a simple Hofstadterian dismissiveness about the paranoia of the cranks. Instead, you have to be able to reject outlandish theories and acknowledge a pattern of government lies and secrecy around a weird, persistent, unexplained feature of human experience — which we know about in part because the U.F.O. conspiracy theorists keep banging on about their subject. The wild theories are false; even so, the secrets and mysteries are real.

Another example: The current elite anxiety about Russia’s hand in the West’s populist disturbances, which reached a particularly hysterical pitch with the pre-Mueller report collusion coverage, is a classic example of how conspiracy theories find a purchase in the supposedly sensible center — in this case, because their narrative conveniently explains a cascade of elite failures by blaming populism on Russian hackers, moneymen and bots.

And yet: Every conservative who rolls her or his eyes at the “Russia hoax” is in danger of dismissing the reality that there is a Russian plot against the West — an organized effort to use hacks, bots and rubles to sow discord in the United States and Western Europe. This effort is far weaker and less consequential than the paranoid center believes, it doesn’t involve fanciful “Trump has been a Russian asset since the ’80s” machinations … but it also isn’t something that Rachel Maddow just made up. The hysteria is overdrawn and paranoid; even so, the Russian conspiracy is real.

A third example: Marianne Williamson’s long-shot candidacy for the Democratic nomination has elevated the holistic-crunchy critique of modern medicine, which often shades into a conspiratorial view that a dark corporate alliance is actively conspiring against American health, that the medical establishment is consciously lying to patients about what might make them well or sick. Because this narrative has given anti-vaccine fervor a huge boost, there’s understandable desire among anti-conspiracists to hold the line against anything that seems like a crankish or quackish criticism of the medical consensus.

But if you aren’t somewhat paranoid about how often corporations cover up the dangers of their products, and somewhat paranoid about how drug companies in particular influence the medical consensus and encourage overprescription — well, then I have an opioid crisis you might be interested in reading about. You don’t need the centralized conspiracy to get a big medical wrong turn; all it takes is the right convergence of financial incentives with institutional groupthink. Which makes it important to keep an open mind about medical issues that are genuinely unsettled, even if the people raising questions seem prone to conspiracy-think. The medical consensus is generally a better guide than crankishness; even so, the tendency of cranks to predict medical scandals before they’re recognized is real.

Finally, a fourth example, circling back to Epstein: the conspiracy theories about networks of powerful pedophiles, which have proliferated with the internet and peaked, for now, with the QAnon fantasy among Trump supporters.

I say fantasy because the details of the QAnon narrative are plainly false: Donald Trump is not personally supervising an operation against “deep state” child sex traffickers any more than my 3-year-old is captaining a pirate ship.

But the premise of the QAnon fantasia, that certain elite networks of influence, complicity and blackmail have enabled sexual predators to exploit victims on an extraordinary scale — well, that isn’t a conspiracy theory, is it? That seems to just be true.

And not only true of Epstein and his pals. As I’ve written before, when I was starting my career as a journalist I sometimes brushed up against people peddling a story about a network of predators in the Catholic hierarchy — not just pedophile priests, but a self-protecting cabal above them — that seemed like a classic case of the paranoid style, a wild overstatement of the scandal’s scope. I dismissed them then as conspiracy theorists, and indeed they had many of conspiracism’s vices — above all, a desire to believe that the scandal they were describing could be laid entirely at the door of their theological enemies, liberal or traditional.

But on many important points and important names, they were simply right.