#and his people are meant to represent the early welsh

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Third major character from my capstone project. This is Hedrek. He's a monk from monotheistic religion that was brought to the Island during the rule of the Empire. He's caught in the middle of the conflict between his people, the ancient natives of the island, and the migrating tribes the other characters are from.

#and yes his religion is meant to be a fantasy christianity#and his people are meant to represent the early welsh#one of the reasons i chose early medieval britain is that interesting ethnoreligious conflict between the early welsh and early english#also he is madly in love with mildwin but wont admit it cause homophobia#A note on the background is that the cross is made up of perfectly overlaping lines#they alternate over and under uniformly#but the snake that has burrowed through the shape has disrupted that pattern#the snake represents hedreks inner turmoil#ice child#art#fantasy art#fantasy#character art#original character#fantasy character

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

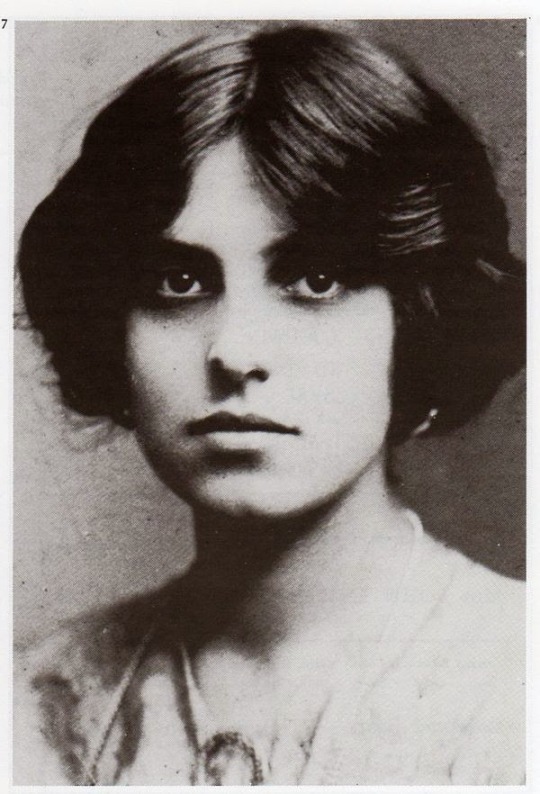

In the earliest Welsh works of the legends, Guinevere was portrayed as a badass warrior queen/spellcaster and I remember Angel saying that she wanted to do more sword-fighting when she became Queen. But I think the whole point of Gwen's character arc is to demonstrate that you don't have to be a powerful sorcerer or a formidable warrior to make a difference in the world.

Wait, I read a fic where Gwen was a druid warrior queen! Was it based on early Arthurian Welsh works? Ah. Gwen as a badass warrior queen or spellcaster... now, how would Arthur have reacted to that?

Yes, Gwen should've done some sword-fighting! She briefly fought Morgana in the Sword in the Stone, so I like the idea of that being the catalyst that made her want to learn self-defense, especially after all she went through in season 4 in particular. If so many people wanted a servant dead, imagine a Queen.

I think we can kind of see the progression of her self-defense skills throughout the show. In The Moment of Truth, she fought alongside Morgana but I don't remember how much she got to wield a sword; in Lancelot and Guinevere, she used a sword to wack at a guy's legs; in The Castle of Fyrien, she used a fire poker to fend off an intruder in her home. Then, in season 4, she thrust her sword into Lamia though she looked comically scared; she ran away from Helios and Morgana; and, in Sword in the Stone, she hit someone in the back of the head with the hilt of her sword, and fought Morgana. I think the fight with Morgana showed her skills had slightly improved, but she still mostly used her sword as a knife and not for dueling haha.

We could've seen Arthur teach Gwen to sword-fight! We were robbed of so much...

I love that Gwen was a servant! The fact that she was supposed to be a white Lady and they cast a black servant has icky implications, but I wouldn't have wanted her to be a Lady at all. I don't like the nobility, and Gwen probably would've been one of those "generous" and "not like other nobles" nobles. I love that she was a commoner, and it was so important to Arthur's character and to the future of Camelot that she was. A Lady Queen, even one from a poorer family, doesn't have the same ring to it as a Servant Queen.

Gwen represented Camelot itself. She represented the people of Camelot. A warrior or sorcerer couldn't have spoken for the people of Camelot, and, honestly, there were enough formidable warriors and sorcerers on the show already. I like that Gwen was normal, because it showed servants could be smart, well-spoken, curious, wise, and had just as much to offer as nobles. At the same time, Gwen wasn't ashamed of being a servant. She wasn't a servant who wished to be a noble, like Lancelot who dreamed of being a Knight. She was proud of being a servant, because she knew her worth and that people like her were the backbone of Camelot.

Both Gwen and Merlin showed that an expensive education and titles couldn't buy intelligence, bravery, kindness, or curiosity; they were both as intelligent and strategic as Arthur - more so actually. Gwen proved to the people of Camelot, particularly after Arthur died and she became the sole ruler, that titles meant nothing and even without magic (Merlin), or good swordsmanship (Lancelot, Elyan) everyone had the potential to, as you said, make a difference.

I also like that there wasn't a real power imbalance between Arthur and Gwen. She was a servant and he the Prince/King, but Arthur was above everyone, so it didn't even matter that he had more power than Gwen. It certainly wasn't a boss and his assistant kind of story; Gwen was never Arthur's personal servant. It also wasn't a Cinderella type of story; Gwen had never dreamed of becoming Queen, or "winning" Arthur's affections, and no one congratulated her for doing so. Arthur and Gwen were just two people who'd fallen in love. From Gwen's side of things, the circumstances of their romance actually made it anti-romantic - as opposed to, for example, how Lancelot had come into her life in the first two seasons.

Anyway, that last bit was off-topic, but something I appreciated the writers for doing, or not doing. Thanks for the ask!

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, I Hear You Liked: 1917

More World War One Films

I was very excited about 1917 when it first came out because it almost perfectly coincided with the 100th anniversary of the First World War, a conflict that I love to read about, write about, and watch movies about. This period is my JAM, and there's such a lot of good content for when you're done with Sam Mendes's film.

Obviously there are a lot of movies and TV shows out there - this is just a selection that I enjoyed, and wish more people knew about.

Note: Everyone enjoys a show or movie for different reasons. These shows are on this list because of the time period they depict, not because of the quality of their writing, the accuracy of their history or the political nature of their content. Where I’m able to, I’ve mentioned if a book is available if you’d like to read more.

I'd like to start the list with a movie that isn't a fiction piece at all - Peter Jackson's They Shall Not Grow Old (2019) is a beautifully produced film that allows the soldiers and archival images themselves, lovingly retimed and tinted into living color, to tell their own story. It is a must watch for anyone interested in the period.

Wings (1927), All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), A Farewell to Arms (1932, 1957), The Dawn Patrol (1938), Sergeant York (1941), and Paths of Glory (1957) are all classics with a couple of Oscars between them, and it's sort of fun to watch how the war gets changed and interpreted as the years pass. (The Dawn Patrol, for instance, might as just as easily be about the RAF in World War 2.)

All Quiet is based on a famous memoir, and A Farewell to Arms on a Hemingway novel; both have several adaptations and they're all a little different. Speaking of iconic novels, Doctor Zhivago (1965) based on the Pasternak novel of the same title, examines life of its protagonist between 1905 and the start of the second World War.

I think one thing historians agree on is that the start of World War One is worth discussing - and that there's a lot of backstory. Fall of Eagles (1974), a 13 part BBC miniseries, details the relationships between the great houses of Europe, starting in the 1860s; it's long but good, and I think might be on YouTube. The Last Czars (2019) takes a dramatized look at the Romanovs and how their reactions to the war lead to their eventual demise.

As far as the war itself, Sarajevo (2014) and 37 Days (2014) both discuss the outbreak of hostilities and the slow roll into actual battle.

The Passing Bells (2014) follows the whole war through the eyes of two soldiers, one German and one British, beginning in peacetime.

Joyeux Noel ( 2005) is a cute story - it takes place early in the war during the Christmas Peace and approaches the event from a multinational perspective.

War Horse (2011) is, of course, a name you'll recognize. Based on the breakout West End play, which is itself based on a YA novel by Michael Morpurgo, the story follows a horse who's requisitioned for cavalry service and the young man who owns him. Private Peaceful (2012) is also based on a Morpurgo novel, but I didn't think it was quite as good as War Horse.

The Wipers Times (2013) is one of my all-time favorites; it's about a short lived trench paper written and produced by soldiers near Ypres, often called Wipers by the average foot soldier. The miniseries, like the paper, is laugh out loud funny in a dark humor way.

My Boy Jack (2007) is another miniseries based on a play, this one about Rudyard Kipling and his son, Jack, who served in the Irish Guards and died at Loos. Kipling later wrote a poem about the death of his son, and helped select the phrase that appears on all commonwealth gravestones of the First World War.

Gallipoli (1981) is stunning in a way only a Peter Weir movie can be; this is a classic and a must-see.

Gallipoli is a big story that's been told and retold a lot. I still haven't seen Deadline Gallipoli (2015) an Australian miniseries about the men who wrote about the battle for the folks back home and were subject to censorship about how bad things really were. For a slightly different perspective, the Turkish director Yesim Sezgin made Çanakkale 1915 in 2012, detailing the Turkish side of the battle. Although most of The Water Diviner (2014) takes place after the war is over, it also covers parts of Gallipoli and while it didn't get great reviews, I enjoy it enough to own it on DVD.

I don't know why all of my favorite WWI films tend to be Australian; Beneath Hill 60 (2010) is another one of my favorites, talking about the 1st Australian Tunneling Company at the Ypres Salient. The War Below (2021) promises to tell a similar story about the Pioneer companies at Messines, responsible for building the huge network of mines there.

Passchendaele (2008) is a Canadian production about the battle of the same name. I'd forgotten I've seen this film, which might not say very much for the story.

Journey's End (2017) is an adaptation of an RC Sheriff play that takes place towards the end of the war in a dugout amongst British officers.

No look at the Great War is complete without a nod to developing military technologies, and this is the war that pioneers the aviation battle for us. I really wish Flyboys (2006) was better than it is, but The Red Baron (2008) makes up for it from the German perspective.

One of the reasons I like reading about the First World War is that everyone is having a revolution. Technology is growing by leaps and bounds, women are fighting for the right to vote, and a lot of colonial possessions are coming into their own, including (but not limited to) Ireland. Rebellion (2016) was a multi-season miniseries that went into the Easter Rising, as well as the role the war played there. Michael Collins (1996) spends more time with the Anglo-Irish war in the 1920s but is still worth watching (or wincing through Julia Roberts' bad accent, you decide.) The Wind that Shakes the Barley covers the same conflict and is excellent.

The centennial of the war meant that in addition to talking about the war, people were also interested in talking about the Armenian Genocide. The Promise (2016) and The Ottoman Lieutenant (2017) came out around the same time and two different looks at the situation in Armenia.

This is a war of poets and writers, of whom we have already mentioned a few. Hedd Wynn ( 1992) which is almost entirely in Welsh, and tells the story of Ellis Evans, a Welsh language poet who was killed on the first day of the Battle of Passchendaele. I think Ioan Gruffudd has read some of his poetry online somewhere, it's very pretty. A Bear Named Winnie (2004) follows the life of the bear who'd become the inspiration for Winnie the Pooh. Tolkien (2019) expands a little on the author's early life and his service during the war. Benediction (2021) will tell the story of Siegfried Sassoon and his time at Craiglockhart Hospital. Craiglockhart is also represented in Regeneration (1997) based on a novel by Pat Barker.

Anzac Girls (2014) is probably my favorite mini-series in the history of EVER; it follows the lives of a group of Australian and New Zealand nurses from hospital duty in Egypt to the lines of the Western Front. I love this series not only because it portrays women (ALWAYS a plus) but gives a sense of the scope of the many theatres of the war that most movies don't. It's based on a book by Peter Rees, which is similarly excellent.

On a similar note, The Crimson Field (2014) explores the lives of members of a Voluntary Aid Detachment, or VADs, lady volunteers without formal nursing training who were sent to help with menial work in hospitals. It only ran for a season but had a lot of potential. Testament of Youth (2014) is based on the celebrated memoirs of Vera Brittain, who served as a VAD for part of the war and lead her to become a dedicated pacifist.

Also, while we're on the subject of women, though these aren't war movies specifically, I feel like the additional color to the early 20th century female experience offered by Suffragette (2015) and Iron-Jawed Angels (2004) is worth the time.

As a general rule, Americans don't talk about World War One, and we sure don't make movies about it, either. The Lost Battalion (2001) tells the story of Major Charles Whittlesey and the 9 companies of the 77th Infantry division who were trapped behind enemy lines during the battle of the Meuse Argonne.

I should add that this list is curtailed a little bit by what's available for broadcast or stream on American television, so it's missing a lot of dramas in other languages. The Road to Calvary (2017) was a Russian drama based on the novels of Alexei Tolstoy. Kurt Seyit ve Şura (2014) is based on a novel and follows a love story between a Crimean officer (a Muslim) and the Russian woman he loves. The show is primarily in Turkish, and Kıvanç Tatlıtuğ, who plays the lead, is *very* attractive.

Finally, although it might seem silly to mention them, Upstairs Downstairs (1971-1975 ) Downton Abbey (2010-2015) and Peaky Blinders (2013-present) are worth a mention and a watch. All of them are large ensemble TV shows that take place over a much longer period than just the Great War, but the characters in each are shaped tremendously by the war.

#so i hear you liked#preaching the period drama gospel i am#world war one#period drama#period drama trash#1917

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Celtic Gods part 2

The gods and goddesses of the pre-Christian Celtic peoples are known from a variety of sources, including ancient places of worship, statues, engravings, cult objects and place or personal names. The ancient Celts appear to have had a pantheon of deities comparable to others in Indo-European religion, each linked to aspects of life and the natural world. By a process of syncretism, after the Roman conquest of Celtic areas, these became associated with their Roman equivalents, and their worship continued until Christianization. Pre-Roman Celtic art produced few images of deities, and these are hard to identify, lacking inscriptions, but in the post-conquest period many more images were made, some with inscriptions naming the deity. Most of the specific information we have therefore comes from Latin writers and the archaeology of the post-conquest period. More tentatively, links can be made between ancient Celtic deities and figures in early medieval Irish and Welsh literature, although all these works were produced well after Christianization.

Epona, the Celtic goddess of horses and riding, lacked a direct Roman equivalent, and is therefore one of the most persistent distinctly Celtic deities. This image comes from Germany, about 200 AD.

Replica of the incomplete Pillar of the Boatmen, from Paris, with four gods, including the only depiction of Cernunnos to name him (left, 2nd from top).

The locus classicus for the Celtic gods of Gaul is the passage in Julius Caesar's Commentarii de Bello Gallico (The Gallic War, 52–51 BC) in which he names six of them, together with their functions. He says that Mercury was the most honoured of all the gods and many images of him were to be found. Mercury was regarded as the inventor of all the arts, the patron of travellers and of merchants, and the most powerful god in matters of commerce and gain. After him, the Gauls honoured Apollo, who drove away diseases, Mars, who controlled war, Jupiter, who ruled the heavens, and Minerva, who promoted handicrafts. He adds that the Gauls regarded Dis Pater as their ancestor.[1]

In characteristic Roman fashion, Caesar does not refer to these figures by their native names but by the names of the Roman gods with which he equated them, a procedure that complicates the task of identifying his Gaulish deities with their counterparts in the insular Celtic literatures. He also presents a neat schematic equation of god and function that is quite foreign to the vernacular literary testimony. Yet, given its limitations, his brief catalog is a valuable witness.

The gods named by Caesar are well-attested in the later epigraphic record of Gaul and Britain. Not infrequently, their names are coupled with native Celtic theonyms and epithets, such as Mercury Visucius, Lenus Mars, Jupiter Poeninus, or Sulis Minerva. Unsyncretised theonyms are also widespread, particularly among goddesses such as Sulevia, Sirona, Rosmerta, and Epona. In all, several hundred names containing a Celtic element are attested in Gaul. The majority occur only once, which has led some scholars to conclude that the Celtic gods and their cults were local and tribal rather than national. Supporters of this view cite Lucan's mention of a god called Teutates, which they interpret as "god of the tribe" (it is thought that teuta- meant "tribe" in Celtic).[2] The multiplicity of deity names may also be explained otherwise – many, for example, may be simply epithets applied to major deities by widely extended cults.[citation needed]

General characteristics Edit

Evidence from the Roman period presents a wide array of gods and goddesses who are represented by images or inscribed dedications.[3] Certain deities were venerated widely across the Celtic world, while others were limited only to a single region or even to a specific locality.[3] Certain local or regional deities might have greater popularity within their spheres than supra-regional deities. For example, in east-central Gaul, the local healing goddess Sequana of present-day Burgundy, was probably more influential in the minds of her local devotees than the Matres, who were worshipped all over Britain, Gaul and the Rhineland.[4]

Supra-regional cults Edit

Among the divinities transcending tribal boundaries were the Matres, Cernunnos, the sky-god Taranis, and Epona. Epona, the horse-goddess, was invoked by devotees living as far apart as Britain, Rome and Bulgaria. A distinctive feature of the mother-goddesses was their frequent depiction as a triad in many parts of Britain, in Gaul and on the Rhine, although it is possible to identify strong regional differences within this group.[5]

The Celtic sky-god too had variations in the way he was perceived and his cult expressed. Yet the link between the Celtic Jupiter and the solar wheel is maintained over a wide area, from Hadrian's Wall to Cologne and Nîmes.[6]

Local cults Edit

It is sometimes possible to identify regional, tribal, or sub-tribal divinities. Specific to the Remi of northwest Gaul is a distinctive group of stone carvings depicting a triple-faced god with shared facial features and luxuriant beards. In the Iron Age, this same tribe issued coins with three faces, a motif found elsewhere in Gaul.[6] Another tribal god was Lenus, venerated by the Treveri. He was worshipped at a number of Treveran sanctuaries, the most splendid of which was at the tribal capital of Trier itself. Yet he was also exported to other areas: Lenus has altars set up to him in Chedworth in Gloucestershire and Caerwent in Wales.[6]

Many Celtic divinities were extremely localised, sometimes occurring in just one shrine, perhaps because the spirit concerned was a genius loci, the governing spirit of a particular place.[6] In Gaul, over four hundred different Celtic god-names are recorded, of which at least 300 occur just once. Sequana was confined to her spring shrine near Dijon, Sulis belonged to Bath. The divine couple Ucuetis and Bergusia were worshipped solely at Alesia in Burgundy. The British god Nodens is associated above all with the great sanctuary at Lydney (though he also appears at Cockersand Moss in Cumbria). Two other British deities, Cocidius and Belatucadrus, were both Martial gods and were each worshipped in clearly defined territories in the area of Hadrian's Wall.[6] There are many other gods whose names may betray origins as topographical spirits. Vosegus presided over the mountains of the Vosges, Luxovius over the spa-settlement of Luxeuil and Vasio over the town of Vaison in the Lower Rhône Valley.

Divine couples Edit

One notable feature of Gaulish and Romano-Celtic sculpture is the frequent appearance of male and female deities in pairs, such as Rosmerta and ‘Mercury’, Nantosuelta and Sucellos, Sirona and Apollo Grannus, Borvo and Damona, or Mars Loucetius and Nemetona.[7]

Notable deity types Edit

Antlered gods Edit

Detail of the antlered figure holding a torc and a ram-headed snake depicted on the 1st or 2nd century BC Gundestrup cauldron discovered in Jutland, Denmark.

Main article: Cernunnos

A recurrent figure in Gaulish iconography is a deity sitting cross-legged with antlers, sometimes surrounded by animals, often wearing or holding a torc. The name usually applied to him, Cernunnos, is attested only a few times: on the Pillar of the Boatmen, a relief in Paris (currently reading ERNUNNOS, but an early sketch shows it as having read CERNUNNOS in the 18th century); on an inscription from Montagnac (αλλετ[ει]νος καρνονου αλ[ι]σο[ντ]εας, "Alletinos [dedicated this] to Carnonos of Alisontea"[8]); and on a pair of identical inscriptions from Seinsel-Rëlent ("Deo Ceruninco"[9]). Figured representations of this sort of deity, however, are widespread; the earliest known was found at Val Camonica in northern Italy,[citation needed] while the most famous is plate A of the Gundestrup Cauldron, a 1st-century BC vessel found in Denmark. On the Gundestrup Cauldron and sometimes elsewhere, Cernunnos, or a similar figure, is accompanied by a ram-headed serpent. At Reims, the figure is depicted with a cornucopia overflowing with grains or coins.[2]

Healing deities Edit

Main articles: Airmed, Belenus, Borvo, Brighid, and Grannus

Healing deities are known from many parts of the Celtic world; they frequently have associations with thermal springs, healing wells, herbalism and light.

Brighid, the triple goddess of healing, poetry and smithcraft is perhaps the most well-known of the Insular Celtic deities of healing. She is associated with many healing springs and wells. A lesser-known Irish healing goddess is Airmed, also associated with a healing well and with the healing art of herbalism.

In Romano-Celtic tradition Belenus (traditionally derived from a Celtic root *belen- ‘bright’,[10] though other etymologies have been convincingly proposed[11]) is found chiefly in southern France and northern Italy. Apollo Grannus, though concentrated in central and eastern Gaul, also “occurs associated with medicinal waters in Brittany [...] and far away in the Danube Basin”.[12] Grannus's companion is frequently the goddess Sirona. Another important Celtic deity of healing is Bormo/Borvo, particularly associated with thermal springs such as Bourbonne-les-Bains and Bourbon-Lancy. Such hot springs were (and often still are) believed to have therapeutic value. Green interprets the name Borvo to mean “seething, bubbling or boiling spring water”.[12]

Solar deities Edit

Though traditionally gods like Lugh and Belenos have been considered to be male sun gods, this assessment is derived from their identification with the Roman Apollo, and as such this assessment is controversial.[citation needed] The sun in Celtic culture is nowadays assumed to have been feminine,[13][14] and several goddesses have been proposed as possibly solar in character.

In Irish, the name of the sun, Grian, is feminine. The figure known as Áine is generally assumed to have been either synonymous with her, or her sister, assuming the role of Summer Sun while Grian was the Winter Sun.[15] Similarly, Étaín has at times been considered to be another theonym associated with the sun; if this is the case, then the pan-Celtic Epona might also have been originally solar in nature,[15] though Roman syncretism pushed her towards a lunar role.[citation needed]

The British Sulis has a name cognate with that of other Indo-European solar deities such as the Greek Helios and Indic Surya,[16][17] and bears some solar traits like the association with the eye as well as epithets associated with light. The theonym Sulevia, which is more widespread and probably unrelated to Sulis,[18] is sometimes taken to have suggested a pan-Celtic role as a solar goddess.[13] She indeed might have been the de facto solar deity of the Celts.[citation needed]

The Welsh Olwen has at times been considered a vestige of the local sun goddess, in part due to the possible etymological association[19] with the wheel and the colours gold, white and red.[13]

Brighid has at times been argued as having had a solar nature, fitting her role as a goddess of fire and light.[13]

Deities of sacred waters Edit

Main articles: Sulis, Damona, and Sequana

Goddesses Edit

In Ireland, there are numerous holy wells dedicated to the goddess Brighid. There are dedications to ‘Minerva’ in Britain and throughout the Celtic areas of the Continent. At Bath Minerva was identified with the goddess Sulis, whose cult there centred on the thermal springs.

Other goddesses were also associated with sacred springs, such as Icovellauna among the Treveri and Coventina at Carrawburgh. Damona and Bormana also serve this function in companionship with the spring-god Borvo (see above).

A number of goddesses were deified rivers, notably Boann (of the River Boyne), Sinann (the River Shannon), Sequana (the deified Seine), Matrona (the Marne), Souconna (the deified Saône) and perhaps Belisama (the Ribble).

Gods Edit

While the most well-known deity of the sea is the god Manannán, and his father Lir mostly considered as god of the ocean. Nodens is associated with healing, the sea, hunting and dogs.

In Lusitanian and Celtic polytheism, Borvo (also Bormo, Bormanus, Bormanicus, Borbanus, Boruoboendua, Vabusoa, Labbonus or Borus) was a healing deity associated with bubbling spring water.[20]Condatis associated with the confluences of rivers in Britain and Gaul, Luxovius was the god of the waters of Luxeuil, worshipped in Gaul. Dian Cécht was the god of healing to the Irish people. He healed with the fountain of healing, and he was indirectly the cause of the name of the River Barrow.[21]Grannus was a deity associated with spas, healing thermal and mineral springs, and the sun.

Horse deities Edit

Goddesses Edit

Epona, 3rd century CE, from Freyming (Moselle), France (Musée Lorrain, Nancy)

Main articles: Epona and Macha

The horse, an instrument of Indo-European expansion, plays a part in all the mythologies of the various Celtic cultures. The cult of the Gaulish horse goddess Epona was widespread. Adopted by the Roman cavalry, it spread throughout much of Europe, even to Rome itself. She seems to be the embodiment of "horse power" or horsemanship, which was likely perceived as a power vital for the success and protection of the tribe. She has insular analogues in the Welsh Rhiannon and in the Irish Édaín Echraidhe (echraidhe, "horse riding") and Macha, who outran the fastest steeds.

A number of pre-conquest Celtic coins show a female rider who may be Epona.

The Irish horse goddess Macha, perhaps a threefold goddess herself, is associated with battle and sovereignty. Though a goddess in her own right, she is also considered to be part of the triple goddess of battle and slaughter, the Morrígan. Other goddesses in their own right associated with the Morrígan were Badhbh Catha and Nemain.

God Edit

Atepomarus in Celtic Gaul was a healing god, and inscriptions were found in Mauvières (Indre). The epithet is sometimes translated as "Great Horseman" or "possessing a great horse".

Mother goddesses Edit

Main article: Matronae

Terracotta relief of the Matres, from Bibracte, city of the Aedui in Gaul

Mother goddesses are a recurrent feature in Celtic religions. The epigraphic record reveals many dedications to the Matres or Matronae, which are particularly prolific around Cologne in the Rhineland.[7] Iconographically, Celtic mothers may appear singly or, quite often, triply; they usually hold fruit or cornucopiae or paterae;[2] they may also be full-breasted (or many-breasted) figures nursing infants.

Welsh and Irish tradition preserve a number of mother figures such as the Welsh Dôn, Rhiannon (‘great queen’) and Modron (from Matrona, ‘great mother’), and the Irish Danu, Boand, Macha and Ernmas. However, all of these fulfill many roles in the mythology and symbolism of the Celts, and cannot be limited only to motherhood. In many of their tales, their having children is only mentioned in passing, and is not a central facet of their identity. "Mother" Goddesses may also be Goddesses of warfare and slaughter, or of healing and smithcraft.

Mother goddesses were at times symbols of sovereignty, creativity, birth, fertility, sexual union and nurturing. At other times they could be seen as punishers and destroyers: their offspring may be helpful or dangerous to the community, and the circumstances of their birth may lead to curses, geasa or hardship, such as in the case of Macha's curse of the Ulstermen or Rhiannon's possible devouring of her child and subsequent punishment.

Lugh Edit

Main articles: Lugus, Lugh, and Lleu

Image of a tricephalic god identified as Lugus, discovered in Paris

According to Caesar the god most honoured by the Gauls was ‘Mercury’, and this is confirmed by numerous images and inscriptions. Mercury's name is often coupled with Celtic epithets, particularly in eastern and central Gaul; the commonest such names include Visucius, Cissonius, and Gebrinius.[7] Another name, Lugus, is inferred from the recurrent place-name Lugdunon ('the fort of Lugus') from which the modern Lyon, Laon, and Loudun in France, Leiden in the Netherlands, and Lugo in Galicia derive their names; a similar element can be found in Carlisle (formerly Castra Luguvallium), Legnica in Poland and the county Louth in Ireland, derived from the Irish "Lú", itself coming from "Lugh". The Irish and Welsh cognates of Lugus are Lugh and Lleu, respectively, and certain traditions concerning these figures mesh neatly with those of the Gaulish god. Caesar's description of the latter as "the inventor of all the arts" might almost have been a paraphrase of Lugh's conventional epithet samildánach ("possessed of many talents"), while Lleu is addressed as "master of the twenty crafts" in the Mabinogi.[22] An episode in the Irish tale of the Battle of Magh Tuireadh is a dramatic exposition of Lugh's claim to be master of all the arts and crafts.[23] Inscriptions in Spain and Switzerland, one of them from a guild of shoemakers, are dedicated to Lugoves, widely interpreted as a plural of Lugus perhaps referring to the god conceived in triple form.[citation needed] The Lugoves are also interpreted as a couple of gods corresponding to the Celtic Dioscures being in this case Lugh and Cernunnos[24]

The Gaulish Mercury often seems to function as a god of sovereignty. Gaulish depictions of Mercury sometimes show him bearded and/or with wings or horns emerging directly from his head, rather than from a winged hat. Both these characteristics are unusual for the classical god. More conventionally, the Gaulish Mercury is usually shown accompanied by a ram and/or a rooster, and carrying a caduceus; his depiction at times is very classical.[2]

Lugh is said to have instituted the festival of Lughnasadh, celebrated on 1 August, in commemoration of his foster-mother Tailtiu.[25]

In Gaulish monuments and inscriptions, Mercury is very often accompanied by Rosmerta, whom Miranda Green interprets to be a goddess of fertility and prosperity. Green also notices that the Celtic Mercury frequently accompanies the Deae Matres (see below).[12]

Taranis Edit

Gallo-Roman Taranis Jupiter with wheel and thunderbolt, carrying torcs. Haute Marne

Main article: Taranis

The Gaulish Jupiter is often depicted with a thunderbolt in one hand and a distinctive solar wheel in the other. Scholars frequently identify this wheel/sky god with Taranis, who is mentioned by Lucan. The name Taranis may be cognate with those of Taran, a minor figure in Welsh mythology, and Turenn, the father of the 'three gods of Dana' in Irish mythology.

Wheel amulets are found in Celtic areas from before the conquest.

Toutatis Edit

Teutates, also spelled Toutatis (Celtic: "Him of the tribe"), was one of three Celtic gods mentioned by the Roman poet Lucan in the 1st century,[26] the other two being Esus ("lord") and Taranis ("thunderer"). According to later commentators, victims sacrificed to Teutates were killed by being plunged headfirst into a vat filled with an unspecified liquid. Present-day scholars frequently speak of ‘the toutates’ as plural, referring respectively to the patrons of the several tribes.[2] Of two later commentators on Lucan's text, one identifies Teutates with Mercury, the other with Mars. He is also known from dedications in Britain, where his name was written Toutatis.

Paul-Marie Duval, who considers the Gaulish Mars a syncretism with the Celtic toutates, notes that:

Les représentations de Mars, beaucoup plus rares [que celles de Mercure] (une trentaine de bas-reliefs), plus monotones dans leur académisme classique, et ses surnoms plus de deux fois plus nombreux (une cinquantaine) s'équilibrent pour mettre son importance à peu près sur le même plan que celle de Mercure mais sa domination n'est pas de même nature. Duval (1993)[2]: 73

Mars' representations, much rarer [than Mercury's] (thirty-odd bas reliefs) and more monotone in their studied classicism, and his epithets which are more than twice as numerous (about fifty), balance each other to place his importance roughly on the same level as Mercury, but his domination is not of the same kind.

Esus Edit

Main article: Esus

Esus appears in two continental monuments, including the Pillar of the Boatmen, as an axeman cutting branches from trees.

Gods with hammers Edit

Main article: Sucellus

Sucellos, the 'good striker' is usually portrayed as a middle-aged bearded man, with a long-handled hammer, or perhaps a beer barrel suspended from a pole. His companion, Nantosuelta, is sometimes depicted alongside him. When together, they are accompanied by symbols associated with prosperity and domesticity. This figure is often identified with Silvanus, worshipped in southern Gaul under similar attributes; Dis Pater, from whom, according to Caesar, all the Gauls believed themselves to be descended; and the Irish Dagda, the 'good god', who possessed a cauldron that was never empty and a huge club.

Gods of strength and eloquence Edit

Main article: Ogmios

A club-wielding god identified as Ogmios is readily observed in Gaulish iconography. In Gaul, he was identified with the Roman Hercules. He was portrayed as an old man with swarthy skin and armed with a bow and club. He was also a god of eloquence, and in that aspect he was represented as drawing along a company of men whose ears were chained to his tongue.

Ogmios' Irish equivalent was Ogma. Ogham script, an Irish writing system dating from the 4th century AD, was said to have been invented by him.[27]

The divine bull Edit

Main article: Tarvos Trigaranus

The relief of Tarvos Trigaranus on the Pillar of the Boatmen.

Another prominent zoomorphic deity type is the divine bull. Tarvos Trigaranus ("bull with three cranes") is pictured on reliefs from the cathedral at Trier, Germany, and at Notre-Dame de Paris.

In Irish literature, the Donn Cuailnge ("Brown Bull of Cooley") plays a central role in the epic Táin Bó Cuailnge ("The Cattle-Raid of Cooley").

The ram-headed snake Edit

A distinctive ram-headed snake accompanies Gaulish gods in a number of representations, including the antlered god from the Gundestrup cauldron, Mercury, and Mars.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lore Episode 32: Tampered (Transcript) - 18th April, 2016

tw: none

Disclaimer: This transcript is entirely non-profit and fan-made. All credit for this content goes to Aaron Mahnke, creator of Lore podcast. It is by a fan, for fans, and meant to make the content of the podcast more accessible to all. Also, there may be mistakes, despite rigorous re-reading on my part. Feel free to point them out, but please be nice!

I grew up watching a television show called MacGyver. If you’ve never had that chance to watch this icon of the 80s, do yourself a favour and give it a try. Sure, the clothes are outdated and the hair… oh my gosh, the hair. But aside from all the bits that didn’t age well, MacMullet and his trusty pocket knife managed to capture my imagination forever. Part of it was the adventure, part of it was the character of the man himself – I mean, the guy was essentially a spy who hated guns, played hockey and lived on a houseboat. But hovering above all those elements was the true core of the show. This man could make anything if his life depended on it. As humans, we have this innate drive inside ourselves to make things. This is how we managed to create things like the wheel, or stone tools and weapons. Our tendency towards technology pulled our ancient ancestors out of the Stone Age and into a more civilised world. Maybe for some of us, MacGyver represented what we wanted to achieve: complete mastery of our own world. But life is rarely that simple, and however hard we try to get our minds and hands around this world we want to rule, some things just slip through the cracks. Accidents happen. Ideas and concepts still allude our limited minds. We’re human, after all, not gods. So, when things go wrong, when our plans fall apart or our expectations fail to be met, we have this sense of pride that often refuses to admit defeat. So, we blame others, and when that doesn’t work, we look elsewhere for answers, and no realm holds more explanation for the unexplainable than folklore. 400 years ago, when women refused to follow the rules of society, they were labelled a witch. When Irish children failed to thrive it was because, of course, because they were a changeling. We’re good at excuses. So, when our ancestors found something broken or out of place, there was a very simple explanation – someone, or something, had tampered with it. I’m Aaron Mahnke, and this is Lore.

The idea of meddlesome creatures isn’t new to us. All around the world, we can find centuries-old folklore that speaks of creatures with a habit of getting in the way and making life difficult for humans. It’s an idea that seems to transcend borders and background, language and time. Some would say that it’s far too coincidental for all these stories of mischief-causing creatures to emerge in places separated by thousands of miles and vast oceans. The púca of Ireland and the ebu gogo of Indonesia are great examples of this – legends that seem to have no reason for their eerie similarities. Both legends speak of small, humanoid creatures that steal food and children, both recommend not making them angry, and both describe their creatures as intrusive pranksters. To many, the evidence is just too indisputable to ignore. Others would say it’s not coincidence at all, merely a product of human nature. We want to believe there’s something out there causing the problems we experience every day. So, of course, nearly every culture in the world has invented a scapegoat. This scapegoat would have to be small to avoid discovery, and they need respect because we’re afraid of what they can do. To a cultural anthropologist, it’s nothing more than logical evolution. Many European folktales include this universal archetype in the form of nature spirits, and much of it can be traced back to the idea of the daemon.

It’s an old word and concept, coming to us from the Greeks. In essence, a daemon is an otherworldly spirit that causes trouble. The root word, daomai, literally means to cut or divide. In many ways, it’s an ancient version of an excuse. If your horse was spooked while you were out for a ride, you’d probably blame it on a daemon. Ancient Minoans believed in them, and in the day of the Greek poet Homer, people would blame their illnesses on them. The daemon, in many ways, was fate. If it happened to you, there was a reason, and it was probably one of these little things that caused it. But over time, the daemon took on more and more names. Arab folklore has the djinn, Romans spoke of a personal companion known as the genius, in Japan, they tell tales of the kami, and Germanic cultures mention fylgja. The stories and names might be unique to each culture, but the core of them all is the same. There’s something interfering with humanity, and we don’t like it.

For the majority of the English-speaking world, the most common creature of this type in folklore, hands down, is the goblin. It’s not an ancient word, most likely originating from the middle ages, but it’s the one that’s front and centre in most of our minds, and from the start it’s been a creature associated with bad behaviour. A legend from the 10th century tells of how the first Catholic bishop of Évreux in France faced a daemon known to the locals there as Gobelinus. Why that name, though, is hard to trace. The best theory goes something like this: there’s a Greek myth about a creature named kobalos, who loved to trick and frighten people. That story influenced other cultures across Europe prior to Christianity’s spread, creating the notion of the kobold in ancient Germany. That word was most likely to root of the word goblin. Kobold, gobold, gobolin – you can practically hear it evolve. The root word of kobold is kobe, which literally means “beneath the earth”, or “cavity in a rock”. We get the English word “cove” from the same root, and so naturally kobolds and their English counterparts, the goblins, are said to live in caves underground, and if that reminds you of dwarves from fantasy literature, you’re closer than you think. The physical appearance of goblins in folklore vary greatly, but the common description is that they are dwarf-like creatures. They cause trouble, are known to steal, and they have tendency to break things and make life difficult. Because of this, people in Europe would put carvings of goblins in their homes to ward off the real thing. In fact, here’s something really crazy. Medieval door-knockers were often carved to resemble the faces of daemons or goblins, and it’s most likely purely coincidental, but in Welsh folklore, goblins are called coblyn, or more commonly, knockers. My point is this: for thousands of years, people have suspected that all of their misfortune could be blamed on small, meddlesome creatures. They feared them, told stories about them, and tried their best to protect their homes from them. But for all that time, they seemed like nothing more than story. In the early 20th century, though, people started to report actual sightings, and not just anyone. These sightings were documented by trained, respected military heroes. Pilots.

When the Wright brothers took their first controlled flight in December of 1903, it seemed like a revelation. It’s hard to imagine it today, but there was a time when flight wasn’t assumed as a method of travel. So, when Wilbur spent three full seconds in the air that day, he and his brother, Orville, did something else: they changed the way we think about our world. And however long it took humans to create and perfect the art of controllable, mechanical flight, once the cat was out of the bag, it bolted into the future without ever looking back. Within just nine years, someone had managed to mount a machine gun onto one of these primitive aeroplanes. Because of that, when the First World War broke out just two years later, military combat had a new element. Of course, guns weren’t the only weapon a plane could utilise, though. The very first aeroplane brought down in combat was an Austrian plane, which was literally rammed by a Russian pilot. Both pilots died after the wreckage plummeted to the ground below. It wasn’t the most efficient method of air combat, but it was a start. Clearly, we’ve spent the many decades since getting very, very good at it. Unfortunately, though, there have been more reasons for combat disasters than machine gun bullets and suicidal pilots, and one of the most unique and mysterious of those causes first appeared in British newspapers. In an article from the early 1900s, it was said that, and I quote, “the newly constituted royal air force in 1918 appears to have detected the existence of a hoard of mysterious and malicious sprites, whose sole purpose in life was to bring about as many as possible of the inexplicable mishaps which, in those days as now, trouble an airman’s life.” The description didn’t feature a name, but that was soon to follow. Some experts think that we can find roots of it in the old English word gremian, which means “to vex” or “to annoy”. It fits the behaviour of the creatures to the letter, and because of that they have been known from the beginning as gremlins.

Now, before we move forward, it might be helpful to take care of your memories of the 1984 classic film by the same name. I grew up in the 80s, and Gremlins was a fantastic bit of eye candy for my young, horror-loving mind, but the truth of the legend has little resemblance to the version that you and I witnessed on the big screen. The gremlins of folklore, at least the stories that came out of the early 20th century that is, describe the ancient stereotypical daemon, but with a twist. Yes, they were said to be small, ranging anywhere from six inches to three feet in height, and yes, they could appear and disappear at will, causing mischief and trouble wherever they went. But in addition, these modern versions of the legendary goblin seem to possess a supernatural grasp of human technology. In 1923, a British pilot was flying over open water when his engine stalled. He miraculously survived the crash into the sea and was rescued shortly after that. When he was safely aboard the rescue vessel, the pilot was quick to explain what had happened. Tiny creatures, he claimed, had appeared on the plane. Whether they appeared out of nowhere or smuggled themselves aboard prior to take-off, the pilot wasn’t sure. However they got there, he said that they proceeded to tamper with the plane’s engine and flight controls, and without power or control, he was left to drop helplessly into the sea.

These reports were infrequent in the 1920s, but as the world moved into the Second World War and the number of planes in the sky began to grow exponentially, more and more stories seemed to follow – small, troublesome creatures who had an almost supernatural ability to hold on to moving aircraft, and while they were there, to do damage and to cause accidents. In some cases, they were even cited inside planes, among the crew and cargo. Stories, as we’ve seen so many times before, have a tendency to spread like disease. Oftentimes, that’s because of fear, but sometimes it’s because of truth, and the trouble is in figuring out where to draw that line, and that line kept moving as the sightings were reported outside the British ranks. Pilots on the German side also reported seeing creatures during flights, as did some in India, Malta and the Middle East. Some might chalk these stories up to hallucinations, or a bit of pre-flight drinking. There are certainly a lot of stories of World War Two pilots climbing into the cockpit after a night of romancing the bottle – and who can blame them? In many cases, these pilots were going to their death, with a 20% chance of never coming back from a mission alive. But there are far too many reports to blame it all on drunkenness or delirium. Something unusual was happening to planes all throughout the Second World War, and with folklore as a lens, some of the reports are downright eerie. In 2014, a 92-year-old World War Two veteran from Jonesborough, Arkansas came forward to tell a story he had kept to himself for seven decades. He’d been a B-17 pilot during the war, one of the legendary flying fortresses that helped allied air forces carry out successful missions over Nazi territory, and it was on one of those missions that this man experienced something that, until recently, he had kept to himself. The pilot, who chose to identify himself with the initials L.W., spoke of how he was a 22-year-old flight commander on the B-17, when something very unusual happened on a combat mission in 1944. He described how, as he brought the aircraft to a higher altitude, the plane began to make strange noises. That wasn’t completely unusual, as the B-17 is an absolutely enormous plane and sometimes turbulence can rattle the structure, but he checked his instrument panel out of habit. According to his story, the instruments seemed broken and confused.

Looking for an answer to the mystery, he glanced out the right-side window, and then froze. There, outside the glass of the cockpit window, was the face of a small creature. The pilot described it as about three feet tall with red eyes and sharp teeth. The ears, he said, were almost owl-like, and its skin was grey and hairless. He looked back toward the front and noticed a second creature, this one moving along the nose of the aircraft. He said it was dancing and hammering away at the metal body of the plane. He immediately assumed he was hallucinating. I can picture him rubbing his eyes and blinking repeatedly like some old Loony Toons film. But according to him, he was as sharp and alert as ever. Whatever it was that he witnessed outside the body of the plane, he said that he managed to shake them off with a bit of “fancy flying”, and that’s his term, not mine. But while the creatures themselves might have vanished, the memory of them would haunt him for the rest of his life. He told only one person afterwards, a gunner on another B-17, but rather than laugh at him his friend acknowledged that he, too, had seen similar creatures on a flight just the day before.

Years prior, in the summer of 1939, an earlier encounter was reported, this time in the Pacific. According to the account, a transport plane took off from the airbase in San Diego in the middle of the afternoon and headed toward Hawaii. Onboard were 13 marines, some of whom were crew of the plane and others were passengers – it was a transport, after all. About halfway through the flight, whilst still over the vast expanse of the blue Pacific, the transport issued a distress signal. After that, the signal stopped, as did all other forms of communication. It was as if the plane had simply gone silent and then vanished, which made it all the more surprising when it reappeared later, outside the San Diego airfield and prepared for landing. But the landing didn’t seem right. The plane came in too fast, it bounced on the runway in rough, haphazard ways, and then finally came to a dramatic emergency stop. Crew on the runway immediately understood why, too – the exterior of the aircraft was extensively damaged, some said it looked like bombs had ripped apart the metal skin of the transport. It was a miracle, they said, that the thing even landed at all. When no one exited the plane to greet them, they opened it up themselves and stepped inside, only to be met with a scene of horror and chaos.

Inside, they discovered the bodies of 12 of the 13 passengers and crew. Each seemed to have died from the same types of wounds, large, vicious cuts and injuries that almost seemed to have originated from a wild animal. Added to that, the interior of the transport smelled horribly of sulphur and the acrid odour of blood. To complicate matters, empty shell casings were found scattered about the interior of the cockpit. The pistols responsible, belonging to the pilot and co-pilot, were found on the floor near their feet, completely spent. 12 men were found, but there was a thirteenth. The co-pilot had managed to stay conscious despite his extensive injuries, just long enough to land the transport at the base. He was alive but unresponsive when they found him, and quickly removed him for emergency medical care. Sadly, the man died a short while later. He never had the chance to report what happened.

Stories of the gremlins have stuck around in the decades since, but they live mostly in the past. Today they are mentioned more like a personified Murphy’s Law, muttered as a humorous superstition by modern pilots. I get the feeling that the persistence of the folklore is due more to its place as a cultural habit than anything else. We can ponder why, I suppose. Why would sightings stop after World War II? Some think it’s because of advancements in aeroplane technology: stronger structures, faster flight speeds, and higher altitudes. The assumption is that, sure, gremlins could hold on to our planes, but maybe we’ve gotten so fast that even that’s become impossible for them. The other answer could just be that the world has left those childhood tales of little creatures behind. We’ve moved beyond belief now. We’ve outgrown it. We know a lot more than we used to, after all, and to our thoroughly modern minds these stories of gremlins sound like just so much fantasy. Whatever reason you subscribe to, it’s important to remember that many people have believed with all their being that gremlins are real, factual creatures, people we would respect and believe.

In 1927, a pilot was over the Atlantic in a plane that, by today’s standards, would be considered primitive. He was alone, and he had been in the air for a very long time but was startled to discover that there were creatures in the cockpit with him. He described them as small, vaporous beings with a strange, otherworldly appearance. The pilot claimed that these creatures spoke to him and kept him alert in a moment when he was overly tired and passed the edge of exhaustion. They helped with the navigation for his journey and even adjusted some of his equipment. This was a rare account of gremlins who were benevolent rather than meddlesome or hostile. Even still, this pilot was so worried about what the public might think of his experience that he kept the details to himself for over 25 years. In 1953, this pilot included the experience in a memoir of his flight. It was a historic journey, after all, and recording it properly required honesty and transparency. The book, you see, was called The Spirit of St. Louis, and the man was more than just a pilot. He was a military officer, an explore, an inventor, and on top of all of that he was also a national hero because of his successful flight from New York to Paris – the first man to do so, in fact. This man, of course, was Charles Lindbergh.

[Closing Statements]

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The dialect spoken by Appalachian people has been given a variety of names, the majority of them somewhat less than complimentary. Educated people who look with disfavor on this particular form of speech are perfectly honest in their belief that something called The English Language, which they conceive of as a completed work - unchanging and fixed for all time - has been taken and, through ignorance, shamefully distorted by the mountain folk.

The fact is that this is completely untrue. The folk speech of Appalachia instead of being called corrupt ought to be classified as archaic. Many of the expressions heard throughout the region today can be found in the centuries-old works of some of the greatest English authors: Alfred, Chaucer, Shakespeare, and the men who contributed to the King James version of the Bible, to cite but a few.

Most editors who work with older materials have long assumed the role of officious busy bodies: never so happy, apparently, as when engaged in tidying up spelling, modernizing grammar, and generally rendering whatever was written by various Britons in ages past into a colorless conformity with today's Standard English.

To this single characteristic of the editorial mind must be ascribed the almost total lack of knowledge on the part of most Americans that the language they speak was ever any different than it is right now. How many people know, for example, that when the poet Gray composed his famous "Elegy" his title for it was "An Elegy Wrote in a Country Churchyard?"

Southern mountain dialect (as the folk speech of Appalachia is called by linguists) is certainly archaic, but the general historical period it represents can be narrowed down to the days of the first Queen Elizabeth, and can be further particularized by saying that what is heard today is actually a sort of Scottish-flavored Elizabethan English. This is not to say that Chaucerian forms will not be heard in everyday use, and even an occasional Anglo-Saxon one as well. When we remember that the first white settlers in what is today Appalachia were the so-called Scotch-Irish along with some Palatine Germans, there is small wonder that the language has a Scottish tinge; the remarkable thing is that the Germans seem to have influenced it so little. About the only locally used dialect word that can be ascribed to them is briggity. The Scots appear to have had it all their own way.

When I first came to Lincoln County as a bride it used to seem to me that everything that did not pooch out, hooved up.

Pooch is a Scottish variant of the word pouch and was in use in the 1600's. Numerous objects can pooch out including pregnant women and gentlemen with "bay windows." Hoove is a very old past participle of the verb to heave and was apparently in use on both sides of the border by 1601. The top of an old-fashioned trunk may be said to hoove up. Another word heard occasionally in the back country is ingerns. Ingems are onions. In Scottish dialect the word is inguns; however, if our people are permitted the intrusive r in potaters, tomaters, tobaccer, and so on, there seems to be no reason why they should not use it in ingems as well.

It is possible to compile a very long list of these Scots words and phrases. I will give only a few more illustrations, and will wait to mention some points on Scottish pronunciation and grammar a little further on.

Fornenst is a word that has many variants. It can mean either "next to" or "opposite from." "Look at that big rattler quiled up fornenst the fence post!" (Quiled is an Elizabethan pronunciation of coiled.) "When I woke up this morning there was a little skift of snow on the ground." "I was getting better, but now I've took a backset with this flu." "He dropped the dish and busted it all to flinders." "Law, I hope how soon we get some rain!" (How soon is supposed to be obsolete, but it enjoys excellent health in Lincoln County.) "That trifling old fixin ain't worth a haet!" Haet means the smallest thing that can be conceived of, and comes from Deil hae't (Devil have it.) Fixin is the Old English or Anglo-Saxon word for she-fox as used in the northern dialect. In the south of England you would have heard vixen, the word used today in Standard English. It is interesting to note that it has been primarily the linguistic historians who have pointed out the predominately Scottish heritage of the Southern mountain people. Perhaps I may be allowed to digress for a moment to trace these people back to their beginnings.

Early in his English reign, James I decided to try to control the Irish by putting a Protestant population into Ireland. To do this he confiscated the lands of the earls of Ulster and bestowed them upon Scottish and English lords on the condition that they settle the territory with tenants from Scotland and England. This was known as the "Great Settlement" or the "King's Plantation," and was begun in 1610.

Most of the Scots who moved into Ulster came from the lowlands1 and thus they would have spoken the Scots variety of the Northumbrian or Northern English dialect. (Most highland Scots at that time still spoke Gaelic.) This particular dialect would have been kept intact if the Scots had had no dealings with the Irish, and this, according to records, was the case.

While in Ulster the Scots multiplied, but after roughly 100 years they became dissatisfied with the trade and religious restrictions imposed by England, and numbers of them began emigrating to the English colonies in America. Many of these Scots who now called themselves the "Scotch-Irish" came into Pennsylvania where, finding the better lands already settled by the English, they began to move south and west. "Their enterprise and pioneering spirit made them the most important element in the vigorous frontiersmen who opened up this part of the South and later other territories farther west into which they pushed."2

Besides the Scots who arrived from Ireland, more came directly from Scotland to America, particularly after "the '45", the final Jacobite uprising in support of "Bonnie Prince Charlie," the Young Pretender, which ended disastrously for the Scottish clans that supported him. By the time of the American Revolution there were about 50,000 Scots in this country.

But to get back to the dialect, let me quote two more linguistic authorities to prove my point about the Scottish influence on the local speech. Raven I. McDavid notes, "The speech of the hill people is quite different from both dialects of the Southern lowlands for it is basically derived from the Scotch-Irish of Western Pennsylvania."3 H. L. Mencken said of Appalachian folk speech, "The persons who speak it undiluted are often called by the Southern publicists, 'the purest Anglo-Saxons in the United States,' but less romantic ethnologists describe them as predominately Celtic in blood; though there has been a large infiltration of English and even German strains."4The reason our people still speak as they do is that when these early Scots and English and Germans (and some Irish and Welsh too) came into the Appalachian area and settled, they virtually isolated themselves from the mainstream of American life for generations to come because of the hills and mountains, and so they kept the old speech forms that have long since fallen out of fashion elsewhere. Things in our area are not always what they seem, linguistically speaking. Someone may tell you that "Cindy ain't got sense enough to come in outen the rain, but she sure is clever." Clever, you see, back in the 1600's meant "neighborly or accommodating." Also if you ask someone how he is, and he replies that he is "very well", you are not necessarily to rejoice with him on the state of his health. Our people are accustomed to use a speech so vividly colorful and virile that his "very well" only means that he is feeling "so-so." If you are informed that "several" people came to a meeting, your informant does not mean what you do by several - he is using it in its older sense of anywhere from about 20 to 100 people. If you hear a person or an animal referred to as ill, that person or animal is not sick but bad-tempered, and this adjective has been so used since the 1300's. (Incidentally, good English used sick to refer to bad health long, long before our forebearers ever started saying ill for the same connotation.)

Many of our people refer to sour milk as blinked milk. This usage goes back at least to the early 1600's when people still believed in witches and the power of the evil eye. One of the meanings of the word blink back in those days was "to glance at;" if you glanced at something, you blinked at it, and thus sour milk came to be called blinked due to the evil machinations of the witch. There is another phrase that occurs from time to time, "Man, did he ever feather into him!" This used to carry a fairly murderous connotation, having gotten its start back in the days when the English long bow was the ultimate word in destructive power. Back then if you drew your bow with sufficient strength to cause your arrow to penetrate your enemy up to the feathers on its shaft, you had feathered into him. Nowadays, the expression has weakened in meaning until it merely indicates a bit of fisticuffs.

One of the most baffling expressions our people use (baffling to "furriners," at least) is "I don't care to. . . ." To outlanders this seems to mean a definite "no," whereas in truth it actually means, "thank you so much, I'd love to." One is forevermore hearing a tale of mutual bewilderment in which a gentleman driving an out-of-state car sees a young fellow standing alongside the road, thumbing. When the gentleman stops and asks if he wants a lift, the boy very properly replies, "I don't keer to," using care in the Elizabethan sense of the word. On hearing this, the man drives off considerably puzzled leaving an equally baffled young man behind. (Even the word foreigner itself is used here in its Elizabethan sense of someone who is the same nationality as the speaker, but not from the speaker's immediate home area.

Reverend is generally used to address preachers, but it is a pretty versatile word, and full-strength whisky, or even the full-strength scent of skunk, are also called reverend. In these latter instances, its meaning has nothing to do with reverence, but with the fact that their strength is as the strength of ten because they are undiluted.

In the dialect, the word allow more often means "think, say, or suppose" than "permit." "He 'lowed he'd git it done tomorrow."A neighbor may take you into her confidence and announce that she has heard that the preacher's daughter should have been running after the mailman. These are deep waters to the uninitiated. What she really means is that she has heard a juicy bit of gossip: the preacher's daughter is chasing the local mail carrier. However, she takes the precaution of using the phrase should have been to show that this statement is not vouched for by the speaker. The same phrase is used in the same way in the Paston Letters in the 1400's.

Almost all the so-called "bad English" used by natives of Appalachia was once employed by the highest ranking nobles of the realms of England and Scotland. Few humans are really passionately interested in grammar so I'll skim as lightly over this section as possible, but let's consider the following bit of dialogue briefly: "I've been a-studying about how to say this, till I've nigh wearried myself to death. I reckon hit don't never do nobody no good to beat about the bush, so I'll just tell ye. Your man's hippoed. There's nothing ails him, but he spends more time using around the doctor's office than he does a-working."The only criticism that even a linguistic purist might offer here is that, in the eighteenth century, hippoed was considered by some, Jonathan Swift among others, to be slangy even though it was used by the English society of the day. (To say someone is hippoed is to say he is a hypochondriac.)

Words like a-studying and a-working are verbal nouns and go back to Anglo-Saxon times; and from the 1300's on, people who studied about something, deliberated or reflected on it. Nigh is the old word for near, and weary was the pronunciation of worry in the 1300's and 1400's. The Scots also used this pronunciation. Reckon was current in Tudor England in the sense of consider or suppose. Hit is the Old English third person singular neuter pronoun for it and has come ringing down through the centuries for over a thousand years. All those multiple negatives were perfectly proper until some English mathematician in the eighteenth century decided that two negatives make a positive instead of simply intensifying the negative quality of some statement. Shakespeare loved to use them. Ye was once used accusatively, and man has been employed since early times to mean husband. And finally, to use means to frequent or loiter. Certain grammatical forms occurring in the dialect have caused it to be regarded with pious horror by school marms. Prominent among the offenders, they would be almost sure to list these: "Bring them books over here." In the 1500's this was good English. "I found three bird's nestes on the way to school." This disyllabic ending for the plural goes back to the Middle Ages. "That pencil's not mine, it her'n." Possessive forms like his'n, our'n, your'n evolved in the Middle Ages on the model of mine and thine. In the revision of the Wycliffe Bible, which appeared shortly after 1380, we find phrases such as ". . .restore to hir alle things that ben hern," and "some of ourn went in to the grave." "He don't scare me none." In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries do was used with he, she, and it. Don't is simply do not, of course. "You wasn't scared, was you?" During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries many people were careful to distinguish between singular you was and plural you were. It became unfashionable in the early nineteenth century although Noah Webster stoutly defended it. "My brother come in from the army last night." This usage goes back to late Anglo-Saxon times. You find it in the Paston Letters and in Scottish poetry. "I done finished my lessons," also has many echoes in the Pastons' correspondence and the Scots poets. From the late Middle Ages on up the Northern dialect of English used formations like this: "guiltless persons is condemned," and so do our people. And finally, in times past, participial forms like these abounded: has beat, has bore with it, has chose. Preterite forms were as varied: blowed, growed, catched, and for climbed you can find clum, clome, clim! all of which are locally used.

Pronunciation of many words has changed considerably, too. Deef for deaf, heered for heard, afeared for afraid, cowcumber for cucumber, bammy for balmy, holp for helped, are a very few. Several distinct characteristics of the language of Elizabeth's day are still preserved. Words that had oi in them were given a long i pronunciation: pizen, jine, bile, pint, and so on. Words with er were frequently pronounced as if the letters were ar: sarvice, sartin, narvous. It is from this time that we get our pronunciation of sergeant and the word varsity which is a clipping of the word university given the ar sound. Another Elizabethan characteristic was the substitution of an i sound for an e sound. You hear this tendency today when people say miny kittle, Chist, git, and so on. It has caused such confusion with the words pen and pin (which our people pronounce alike as pin) that they are regularly accompanied by a qualifying word - stick pin for the pin and pin and ink pin for the pen.You can hear many characteristic Scottish pronunciations. Whar, thar, dar (where, there, and dare) are typical. So also are poosh, boosh, eetch, deesh, (push, bush, itch, dish and fish.)

In some ways this vintage English reflects the outlook and spirit of the people who speak it; and, we find that not only is the language Elizabethan, but that some of the ways these people look at things are Elizabethan too. Many other superstitions still exist here. In some homes, when a death occurs all the mirrors and pictures are turned to the wall. Now I don't know if today the people still know why they do this, or if they just go through the actions because it's the thing to do, but this belief goes far back in history. It was once thought that the mirror reflected the soul of the person looking into it and if the soul of the dead person saw the soul of one of his beloved relatives reflected in the mirror, he might take it with him, so his relatives were taking no chances.

The belief that if a bird accidentally flies into a house, a member of the household will die, is also very old, and is still current in the region. Cedar trees are in a good deal of disfavor in Lincoln County, and the reason seems to stem from the conviction held by a number of people that if someone plants a cedar he will die when it grows large enough to shade his coffin.

Aside from its antiquity, the most outstanding feature of the dialect is its masculine flavor - robust and virile. This is a language spoken by a red-blooded people who have colorful phraseology born in their bones. They tend to call a spade a spade in no uncertain terms. "No, the baby didn't come early, the weddin' came late," remarked one proud grandpa. Such people have small patience with the pallid descriptive limitations of standard English. They are not about to be put off with the rather insipid remark, "My, it's hot!" or, "isn't it cold out today?" They want to know just how hot or cold: "It's hotter 'n the hinges of hell" or "Hit's blue cold out thar!" Other common descriptive phrases for cold are (freely) translated) "It's colder 'n a witch's bosom" or it's colder 'n a well-digger's backside."

Speakers of Southern mountain dialect are past masters of the art of coining vivid descriptions. Their everyday conversation is liberally sprinkled with such gems as: "That man is so contrary, if you throwed him in a river he'd float upstream!" "She walks so slow they have to set stakes to see if she's a-movin!" "Thet pore boy's an awkward size - too big for a man and not big enough for a horse." "Zeke, he come bustin' outta thar and hit it for the road quick as double-geared lightenin!"

Nudity is frowned upon in Appalachia, but for some reason there are numerous "nekkid as. ." phrases. Any casual sampling would probably contain these three: "Nekkid as a jaybird," "bare-nekkid as a hound dog's rump," and "start nekkid." Start-nekkid comes directly from the Anglo-Saxons, so it's been around for more than a thousand years. Originally "Start" was steort which meant "tail." Hence, if you were "start-nekkid," you were "nekkid to the tail." A similar phrase, "stark-naked" is a Johnny-come-lately, not even appearing in print until around 1530. If a lady tends to be gossipy, her friends may say that "her tongue's a mile long," or else that it "wags at both ends." Such ladies are a great trial to young dating couples. Incidentally, there is a formal terminology to indicate exactly how serious the intentions of these couples are, ranging from sparking which is simply dating, to courting which is dating with a more serious intent, on up to talking, which means the couple is seriously contemplating matrimony. Shakespeare uses talking in this sense in King Lear.

If a man has imbibed too much of who-shot-John, his neighbor may describe him as "so drunk he couldn't hit the ground with his hat," or, on the morning-after, the sufferer may admit that "I was so dang dizzy I had to hold on to the grass afore I could lean ag'in the ground."

One farmer was having a lot of trouble with a weasel killing his chickens. "He jest grabs 'em before they can git word to God," he complained.

Someone who has a disheveled or bedraggled appearance may be described in any one of several ways: "You look like you've been chewed up and spit out," or "you look like you've been a-sortin wildcats," or "you look like the hindquarters of hard luck," or, simply, "you look like somethin the cat drug in that the dog wouldn't eat!"

"My belly thinks my throat is cut" means "I'm hungry," and seems to have a venerable history of several hundred years. I found a citation for it dated in the early 1500's.A man may be "bad to drink" or "wicked to swear", but these descriptive adjectives are never reversed.

You ought not to be shocked if you hear a saintly looking grandmother admit she likes to hear a coarse-talking man; she means a man with a deep bass voice, (this can also refer to a singing voice, and in this case, if grandma prefers a tenor, she'd talk about someone who sings "Shallow.") Nor ought you to leap to the conclusion that a "Hard girl" is one who lacks the finer feminine sensibilities. "Hard" is the dialectal pronunciation of hired and seems to stem from the same source as do "far" engines that run on rubber "tars."

This language is vivid and virile, but so was Elizabethan English. However, some of the things you say may be shocking the folk as much as their combined lexicons may be shocking you. For instance, in the stratum of society in which I was raised, it was considered acceptable for a lady to say either "damn" or "hell" if strongly moved. Most Appalachian ladies would rather be caught dead than uttering either of these words, but they are pretty free with their use of a four letter word for manure which I don't use. I have heard it described as everything from bug _____ to bull ______. Some families employ another of these four letter words for manure as a pet name for the children, and seem to have no idea that it is considered indelicate in other areas of the country.Along with a propensity for calling a spade a spade, the dialect has a strange mid-victorian streak in it too. Until recently, it was considered brash to use either the word bull or stallion. If it was necessary to refer to a bull, he was known variously as a "father cow" or a "gentleman cow" or an "ox" or a "mas-cu-line," while a stallion was either a "stable horse" or else rather ominously, "The animal." Only waspers fly around Lincoln County, I don't think I've ever heard of a wasp there, and I've never been able to trace the reason for that usage, but I do know why cockleburrs are called cuckleburrs. The first part of the word cockleburr carries an objectionable connotation to the folk. However, if they are going to balk at that, it seems rather hilarious to me that they find nothing objectionable about cuckle.