#and enterprises of great pitch and moment / with this regard their currents turn awry / and lose the name of action

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

just stood in my living room for ten minutes rereading my paperback copy of hamlet only to decide that i am correct about my original interpretation of the to be or not to be monologue can u tell i am

avoiding writing

#i always forget it but the last few lines of that monologue go so hard#like not go hard as in 'are objectively correct' living is poggers#but like#thus conscience does make cowards of us all / and thus the native hue of resolution / is sicklied o'er with the pale cast of thought#and enterprises of great pitch and moment / with this regard their currents turn awry / and lose the name of action#have we not all been there before. god damn.#is there no experience more universal than wondering how life could possibly be better than death#before being like wait but wtf happens when u die. fuck.#anyways. not to be a freak but i love hamlet

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

To be, or not to be?

That is the question—

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And, by opposing, end them?

To die, to sleep—No more—and by a sleep to say we end

The heartache and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to—’tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wished!

To die, to sleep.

To sleep, perchance to dream—ay, there’s the rub,

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause. There’s the respect

That makes calamity of so long life.

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time,

Th’ oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely,

The pangs of despised love, the law’s delay,

The insolence of office, and the spurns

That patient merit of th’ unworthy takes,

When he himself might his quietus make

With a bare bodkin?

Who would fardels bear,

To grunt and sweat under a weary life,

But that the dread of something after death,

The undiscovered country from whose bourn

No traveler returns, puzzles the will

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others that we know not of?

Thus conscience does make cowards of us all,

And thus the native hue of resolutionIs sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought,

And enterprises of great pitch and moment

With this regard their currents turn awry,

And lose the name of action.

—Soft you now,

The fair Ophelia! —Nymph, in thy orisons

Be all my sins remembered.

wow thank you! i enjoy hamlet!

anyhow

my favourite shakespeare play is a midsummer nights dream :)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"To be, or not to be, that is the question: Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, Or to take arms against a sea of troubles, And by opposing, end them. To die, to sleep— No more, and by a sleep to say we end The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks That flesh is heir to; ’tis a consummation Devoutly to be wish’d. To die, to sleep— To sleep, perchance to dream—ay, there’s the rub, For in that sleep of death what dreams may come, When we have shuffled off this mortal coil, Must give us pause; there’s the respect That makes calamity of so long life: For who would bear the whips and scorns of time, Th’ oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely, The pangs of despis’d love, the law’s delay, The insolence of office, and the spurns That patient merit of th’ unworthy takes, When he himself might his quietus make With a bare bodkin; who would fardels bear, To grunt and sweat under a weary life, But that the dread of something after death, The undiscover’d country, from whose bourn No traveler returns, puzzles the will, And makes us rather bear those ills we have, Than fly to others that we know not of? Thus conscience does make cowards of us all, And thus the native hue of resolution Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought, And enterprises of great pitch and moment With this regard their currents turn awry, And lose the name of action.—Soft you now, The fair Ophelia. Nymph, in thy orisons Be all my sins rememb’red." — Hamlet, 3.1.56

0 notes

Text

“To be, or not to be, that is the question:

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And by opposing, end them. To die, to sleep—

No more, and by a sleep to say we end

The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to; ’tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wish’d. To die, to sleep—

To sleep, perchance to dream—ay, there’s the rub,

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come,

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause; there’s the respect

That makes calamity of so long life:

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time,

Th’ oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely,

The pangs of despis’d love, the law’s delay,

The insolence of office, and the spurns

That patient merit of th’ unworthy takes,

When he himself might his quietus make

With a bare bodkin; who would fardels bear,

To grunt and sweat under a weary life,

But that the dread of something after death,

The undiscover’d country, from whose bourn

No traveller returns, puzzles the will,

And makes us rather bear those ills we have,

Than fly to others that we know not of?

Thus conscience does make cowards of us all,

And thus the native hue of resolution

Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought,

And enterprises of great pitch and moment

With this regard their currents turn awry,

And lose the name of action.”

Hamlet, Act 3 Scene 1

William Shakespeare

0 notes

Note

To be, or not to be?

That is the question—

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And, by opposing, end them?

To die, to sleep—No more—and by a sleep to say we end

The heartache and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to—’tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wished!

To die, to sleep.

To sleep, perchance to dream—ay, there’s the rub,

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause. There’s the respect

That makes calamity of so long life.

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time,

Th’ oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely,

The pangs of despised love, the law’s delay,

The insolence of office, and the spurn.

That patient merit of th’ unworthy takes,

When he himself might his quietus make

With a bare bodkin? Who would fardels bear,

To grunt and sweat under a weary life,

But that the dread of something after death,

The undiscovered country from whose bourn

No traveler returns, puzzles the will

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others that we know not of?

Thus conscience does make cowards of us all,

And thus the native hue of resolutionIs sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought,

And enterprises of great pitch and moment

With this regard their currents turn awry,

And lose the name of action.

—Soft you now,The fair Ophelia!

—Nymph, in thy orisons

Be all my sins remembered.

🫶

1 note

·

View note

Note

To be, or not to be?

That is the question—

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And, by opposing, end them?

To die, to sleep—No more—and by a sleep to say we end

The heartache and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to—’tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wished!

To die, to sleep.

To sleep, perchance to dream—ay, there’s the rub,

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause. There’s the respect

That makes calamity of so long life.

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time,

Th’ oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely,

The pangs of despised love, the law’s delay,

The insolence of office, and the spurns

That patient merit of th’ unworthy takes,

When he himself might his quietus make

With a bare bodkin? Who would fardels bear,

To grunt and sweat under a weary life,

But that the dread of something after death,

The undiscovered country from whose bourn

No traveler returns, puzzles the will

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others that we know not of?

Thus conscience does make cowards of us all,

And thus the native hue of resolutionIs sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought,

And enterprises of great pitch and moment

With this regard their currents turn awry,

And lose the name of action.

—Soft you now,

The fair Ophelia! —Nymph, in thy orisons

Be all my sins remembered.

why

0 notes

Text

Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, Or to take Arms against a Sea of troubles, And by opposing end them: to die, to sleep No more; and by a sleep, to say we end The heart-ache, and the thousand natural shocks That Flesh is heir to? 'Tis a consummation Devoutly to be wished. To die, to sleep, To sleep, perchance to Dream; aye, there's the rub, For in that sleep of death, what dreams may come, When we have shuffled off this mortal coil, Must give us pause. There's the respect That makes Calamity of so long life: For who would bear the Whips and Scorns of time, The Oppressor's wrong, the proud man's Contumely, The pangs of dispised Love, the Law’s delay, The insolence of Office, and the spurns That patient merit of th'unworthy takes, When he himself might his Quietus make With a bare Bodkin? Who would Fardels bear, To grunt and sweat under a weary life, But that the dread of something after death, The undiscovered country, from whose bourn No traveller returns, puzzles the will, And makes us rather bear those ills we have, Than fly to others that we know not of? Thus conscience does make cowards of us all, And thus the native hue of Resolution Is sicklied o'er, with the pale cast of Thought, And enterprises of great pitch and moment, With this regard their Currents turn awry, And lose the name of Action

202 notes

·

View notes

Text

To be or not to be- William Shakespeare

original text:

To be, or not to be? That is the question—

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And, by opposing, end them? To die, to sleep—

No more—and by a sleep to say we end

The heartache and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to—’tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wished! To die, to sleep.

To sleep, perchance to dream—ay, there’s the rub,

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause. There’s the respect

That makes calamity of so long life.

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time,

Th’ oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely,

The pangs of despised love, the law’s delay,

The insolence of office, and the spurns

That patient merit of th’ unworthy takes,

When he himself might his quietus make

With a bare bodkin? Who would fardels bear,

To grunt and sweat under a weary life,

But that the dread of something after death,

The undiscovered country from whose bourn

No traveler returns, puzzles the will

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others that we know not of?

Thus conscience does make cowards of us all,

And thus the native hue of resolution

Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought,

And enterprises of great pitch and moment

With this regard their currents turn awry,

And lose the name of action. —Soft you now,

The fair Ophelia! —Nymph, in thy orisons

Be all my sins remembered.

modern English translation:

To live, or to die? That is the question.

Is it nobler to suffer through all the terrible things

fate throws at you, or to fight off your troubles,

and, in doing so, end them completely?

To die, to sleep—because that’s all dying is—

and by a sleep I mean an end to all the heartache

and the thousand injuries that we are vulnerable to—

that’s an end to be wished for!

To die, to sleep. To sleep, perhaps to dream—yes,

but there’s there’s the catch. Because the kinds of

dreams that might come in that sleep of death—

after you have left behind your mortal body—

are something to make you anxious.

That’s the consideration that makes us suffer

the calamities of life for so long.

Because who would bear all the trials and tribulations of time—

the oppression of the powerful, the insults from arrogant men,

the pangs of unrequited love, the slowness of justice,

the disrespect of people in office,

and the general abuse of good people by bad—

when you could just settle all your debts

using nothing more than an unsheathed dagger?

Who would bear his burdens, and grunt

and sweat through a tiring life, if they weren’t frightened

of what might happen after death—

that undiscovered country from which no visitor returns,

which we wonder about and which makes us

prefer the troubles we know rather than fly off

to face the ones we don’t? Thus, the fear of

death makes us all cowards, and our natural

willingness to act is made weak by too much thinking.

Actions of great urgency and importance

get thrown off course because of this sort of thinking,

and they cease to be actions at all.

But wait, here is the beautiful Ophelia!

[To OPHELIA] Beauty, may you forgive all my sins in your prayers

the meaning in a nutshell:

The “To be or not to be” soliloquy appears in the third act of Hamlet. In this scene, Hamlet thinks about life, death and suicide, more specifically, he wonders whether it might be preferable to commit suicide to end one's suffering and to leave behind the pain and agony associated with living.

In the first line, he wonders whether “to be, or not to be”, but in reality he is wondering whether to live or die. Hamlet poses this as a question for all of humanity rather than for only himself. He begins by asking whether it is better to passively put up with life’s pains or commit suicide.

Hamlet initially argues that death would indeed be preferable: he compares the act of dying to a peaceful sleep. In fact, from his point of view, if death is but a sleep, and dying is just like falling asleep, then perhaps we will dream after death.

He thinks it is better to die because a man has to bear many miseries an injustices, such as the passage of time, abuse, discrimination, the outrage of the proud man, the pain of unreturned love, the inefficiency of the legal system, the arrogance of people in power and the mistreatment of evil people.

Hamlet views death and the afterlife as a peaceful liberation from the never-ending agony of our life, but, deep down, Hamlet does not believe in a true “afterlife”. After seeing the sins of man, he has a hard time believing that we deserve such a fate and seems to almost hope that all that awaits is peaceful nothingness.

However, he quickly changes his mind when he considers that nobody knows for sure what happens after death, or whether there is an afterlife and whether this afterlife might be even worse than life. This realization is the reason why Hamlet delays things.

In the end, the whole meaning is that humans are so fearful of what comes after death and the possibility that it might be more miserable than our life. If life means suffering, it is better to die, but it is not easy because conscience makes us cowards.

The function of the soliloquy is for the audience to develop a further understanding of a character’s thoughts and reflect about life and death. Hamlet appears darkfull, tormented and wants to analyze the complexity of life and death.

the 4 temperaments/humours:

The play can be read as a study of “melancholia”, a term used in the Renaissance to say a form of depression. This term was based on the theory of the 4 temperaments or humours.

For centuries, starting in ancient Greece, doctors believed that the body contained 4 fluids or “humours” and that good health and temperament depended on their balance. An imbalance of “black bile” was believed to cause sadness, in fact the term “melancholia” comes from “melaina kole”, which means black bile. There is also a long tradition of studies devoted to understanding the value of sadness: in The Anatomy of Melancholic, from 1621, Robert Burton analysed the causes and manifestations of sadness. He saw sadness, not only as an inevitable part of life, but an essential part of being human and he also believed that wise people feel more sorrow and that melancholy is necessary to achieve wisdom.

Hamlet:

Hamlet has to avenge the murder of his father, but he fails to keep his promises to him until the final act, but he does impulsively because of his anger.

Most critics have drawn the conclusion that is caused by Hamlet’s habit of delaying things. He says he is afflicted by a form of depression, which was called “melancholy” in Shakespeare’s day and is caused by a series of shocking events (such as his father’s death and his mother’s remarriage). His constant doubt about his role as avenger also expresses his rejection of a barbaric way of life because after all he finds injustice, corruption and inhumanity intolerable.

#hamlet#shakespeare#william shakespeare#to be or not to be#soliloquy#England's golden age#england#english literature#literature#4 temperaments#4 humours#ancient greek#dark academia#light academia#academia#life and death#renaissance#english renaissance

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

To be, or not to be, that is the question: Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, Or to take arms against a sea of troubles And by opposing end them. To die—to sleep, No more; and by a sleep to say we end The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks That flesh is heir to: 'tis a consummation Devoutly to be wish'd. To die, to sleep; To sleep, perchance to dream—ay, there's the rub: For in that sleep of death what dreams may come, When we have shuffled off this mortal coil, Must give us pause—there's the respect That makes calamity of so long life. For who would bear the whips and scorns of time, Th'oppressor's wrong, the proud man's contumely, The pangs of dispriz'd love, the law's delay, The insolence of office, and the spurns That patient merit of th'unworthy takes, When he himself might his quietus make With a bare bodkin? Who would fardels bear, To grunt and sweat under a weary life, But that the dread of something after death, The undiscovere'd country, from whose bourn No traveller returns, puzzles the will, And makes us rather bear those ills we have Than fly to others that we know not of? Thus conscience does make cowards of us all, And thus the native hue of resolution Is sicklied o'er with the pale cast of thought, And enterprises of great pitch and moment With this regard their currents turn awry And lose the name of action.

185 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alright. I'm by no means in practice with writing anymore, but these are two of my favorite hyperfixations and I can't resist.

There are so many overlaps between Aziraphale and our boy Hamlet. It's a pretty easy argument to say that Hamlet's biggest problem is that, when faced with divine (occult?) decree, he just can't quite choose action over inaction.

Let me start with my favorite line from this speech:

Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer / The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, / Or to take arms against a sea of troubles / And by opposing end to them.

Translation: Is it better to subject myself to unending pain and sorrow, or to stand against it all and, as must happen, die as a consequence?

Thus conscience makes cowards of us all. / And thus the native hue of resolution / Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought, / And enterprises of great pitch and moment / With this regard their currents turn awry / And lose the name of action.

Put simply, the thing that stops us from taking action is conscience and thought. After all, "who would bear the whips and scorns of time, th’ oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s [insults], the pangs of despised love, the law’s delay [injustice in this life]...? Who would...grunt and sweat under a weary life," unless fear of the unknown, of the consequences, of something worse coming after?

And consider that Hamlet has heaven or hell to look forward to after death. "To die, to sleep, perchance to dream." Aziriphale and Crowley face total and utter annihilation.

Aziraphale has chosen to subject himself to the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune. He has chosen a sea of sorrow, because the alternative is the loss of Crowley. How could he possibly choose anything else?

In conclusion: Aziraphale has spent his entire existence on Earth suffering because he is afraid, as he has every right to be. Let us not forget that Hell is so violent that torture has to be animated. It's so mind-bendingly, reality-defyingly horrific that it leaves reality all together. The cramped hallways and office space is reserved for the upper echelons. No. Far better for Aziraphale to suffer quietly and with nobility.

Buck up, Hamlet!

***Trigger warning: Death and taking your own life in the context of Shakespeare***

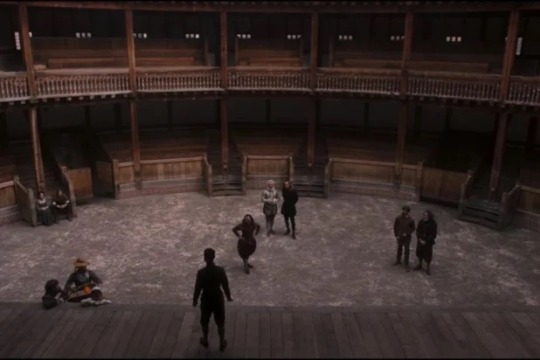

Aziraphale likes Hamlet. Likes the play so much, that he bats his eyelashes at Crowley until the demon performs a miracle to make the mopey Prince of Denmark more popular. Well, good job, the both of you, because four hundred and some odd years later, you still can't get through repertory auditions without some bugger hoisting a skull and starting that monologue. Not that I don't appreciate Hamlet from a structural and analytical perspective. And the Prince of Denmark is a character most actors would sacrifice several toes to play. But it's dark. It's not a fun one.

So why does Aziraphale like it so much? Why's this fluffy little angel so Hell-bent on one of Shakespeare's tragedies? Join me, friendly Good Omens scholars, and let's suss some shit out.

Crowley adamantly dislikes Shakespeare's tragedies. "This isn't one of Shakespeare's gloomy ones, is it? Arghhhh. No wonder no one is here," he complains, wilting like a floppy noodle. Of course, it doesn't take much for Aziraphale to weasel the demon into miracling more people into the audience. But Crowley makes a point to say that he "still prefer(s) the funny ones" as he's leaving The Globe.

Crowley, I would argue, goes to the theatre to escape his real-life situation. He's a bloody demon who, when he's not stationed on Earth, literally goes to Hell. And it's not a nice place. Crowley's everyday life (particularly when he's not around Aziraphale) revolves around pain and suffering--whether its his or someone else's is insignificant. What matters is that regularly sees and experiences tangible, visceral representations of tragedy in his actual existence. Of course he prefers Shakespeare's funny ones! They're a reminder that the world and the human race that he's accidentally become so attached to is full of more than torment and affliction. Crowley doesn't appreciate Shakespeare's tragedies because they're an extension of his own suffering, with which he's already intimately familiar. For Crowley, attending a Shakespearean tragedy is like picking a scab. You already know you've been injured and fussing with the damned thing only makes it worse.

This is not the case for Azirapahle. As an angel, he's not allowed to have any scabs, much less pick at them. Like Crowley, he sees suffering in the world. He knows that humanity is constantly facing difficult odds, and even the most wonderful of human lives eventually ends in death. But unlike Crowley, Aziraphale works within a system in which there is no gray space--and therefore, no room for an angel, an agent of the side of righteousness, to experience doubt in the Ineffable Plan. The Heavenly model is to deal with problems by pretending they don't exist. Heaven has an image to maintain, after all. Like, the sheer amount of repression we see amongst the Heavenly Host is honestly terrifying. I'm thinking about the way in which The Metatron frames the Fall and damnation of a third of the angels. "For one Prince of Heaven to be cast into the outer darkness makes a good story. For it to happen twice, makes it look like there is some kind of institutional problem." It's so cold and removed because to process something so traumatic would not fit the image of Heaven. So it's neatly boxed up and packed away into a soundbite that better fits Heaven's corporate brand.

Aziraphale's suffering is certainly no less than Crowley's. The angel's trauma is repressed. It's cloaked in shining bright hallways of pure angelic light. It's hidden behind false words and tight smiles. It's communicated passive-aggressively by abusers who still have the angel caught in their web of control and manipulation. At least Crowley's trauma is visible. When he fell, the demon took on a new appearance that physically demonstrates his suffering. He has access to feelings of anger and frustration and he's allowed to express these things because he's a demon. He doesn't have to be good.

Since Aziraphale is not permitted to own his emotions and his trauma, he outsources them. He enjoys Shakespeare's tragedies because they give him the opportunity to achieve second-hand catharsis. He may not be able to admit that he's suffering, but he can experience Hamlet's pain vicariously.

***Reminding you of that trigger warning, folks!***

And this is where we get to the question, "To be, or not to be?" This is the moment in S1 E3 when Aziraphale interacts with Richard Burbage, and shouts out, "To be! Not to be! Come on, Hamlet, buck up!" He says this with this coy little smile, obviously trying to get a laugh out of Crowley. But it's indicative of a more serious dilemma that the angel, himself, must parse out. In Shakespeare's play, Hamlet's query is expressed as he wrestles with the choice between life and death. Essentially, it's a contemplation of suicide--a dark part of humanity that Heaven manages by eternally condemning those who would risk it. However there's another way to read this question, not as life and death, but as agency and the lack thereof. We think of "to be" as the choice for life and "not to be" as the option for suicide. But the only way in which Hamlet can express his agency is by taking control of the one thing that truly belongs to him: his own life. So when asking this question of an eternal being, what exactly does it mean, "To be?" What does it mean for Aziraphale to express agency in his immortal existence?

In Western thought, we tend to divide things into binaries: right and wrong, black and white, good and evil...to be or not to be. Back in the Garden if Eden, Crowley first introduced Adam and Eve to the idea that they had a choice. The serpent presented two options, obey or disobey God's authority. Though I think a better way of looking at it would be to say, passively accept your role or have agency in your fate. This is Crowley's method. He never pushes temptations upon you. He just wants to make sure you know all your options.

Like Hamlet, Aziraphale is presented with the choice of, "To be or not to be?" He can sign on the dotted line and follow Heaven's authority or he can be an angel with agency, an angel that goes along with Heaven as far as he can. And though Aziraphale still struggles with how exactly free will pertains to angels, Crowley shows him time and time again that he has options--he can make his own choices. From the very first interaction between the angel and the demon on the wall of Eden, Crowley (ever the optimist) knows there is hope for some meaningful connection with Aziraphale, because the angel makes a choice for himself: he gives away his sword. And from that moment, Crowley realizes that this angel might be just enough of a bastard to be worth knowing.

It's no wonder Aziraphale gets attached to the tragedy of Hamlet. It allows him to observe and process the darker and more difficult emotions that he, as an angel, struggles to manage. And perhaps more importantly, the Prince of Denmark's famous soliloquy mirrors of Crowley's method of temptation, wherein the demon simply reminds him that he has a choice and that, even as an angel, he can find ways to express his agency.

306 notes

·

View notes

Text

GRRM sneaking in some Breakspear. Err, Shakespeare.

And when the bleak dawn broke over an empty horizon, Dany knew that he was truly lost to her. “When the sun rises in the west and sets in the east,” she said sadly. “When the seas go dry and mountains blow in the wind like leaves. When my womb quickens again, and I bear a living child. Then you will return, my sun-and-stars, and not before.”

Never, the darkness cried, never never never.

Inside the tent Dany found a cushion, soft silk stuffed with feathers. She clutched it to her breasts as she walked back out to Drogo, to her sun-and-stars. If I look back I am lost. It hurt even to walk, and she wanted to sleep, to sleep and not to dream. She knelt, kissed Drogo on the lips, and pressed the cushion down across his face. (AGOT, Daenerys IX)

Wait a second….

To be, or not to be, that is the question: Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, Or to take Arms against a Sea of troubles, And by opposing end them: to die, to sleep; No more; and by a sleep, to say we end The heart-ache, and the thousand natural shocks That Flesh is heir to? 'Tis a consummation Devoutly to be wished. To die, to sleep, To sleep, perchance to Dream; aye, there's the rub, For in that sleep of death, what dreams may come, When we have shuffled off this mortal coil, Must give us pause. There's the respect That makes Calamity of so long life: For who would bear the Whips and Scorns of time, The Oppressor's wrong, the proud man's Contumely, The pangs of dispised Love, the Law’s delay, The insolence of Office, and the spurns That patient merit of the unworthy takes, When he himself might his Quietus make With a bare Bodkin? Who would Fardels bear, To grunt and sweat under a weary life, But that the dread of something after death, The undiscovered country, from whose bourn No traveller returns, puzzles the will, And makes us rather bear those ills we have, Than fly to others that we know not of. Thus conscience does make cowards of us all, And thus the native hue of Resolution Is sicklied o'er, with the pale cast of Thought, And enterprises of great pitch and moment, With this regard their Currents turn awry, And lose the name of Action. Soft you now, The fair Ophelia? Nymph, in thy Orisons Be all my sins remember'd.

(Hamlet)

I wouldn’t have made a post on this if I didn’t think this tied into the whole theme of escaping rage and bearing the pains of life along with the joys. That this is the center of the conflict that created the imbalance of the seasons. Someone pulled a Dany and dabbled in the darkest of magic because they couldn’t bear one of life’s heart-rending injustices. There is a reason that in moments of extreme wrath, faces start looking like heart trees with the red tears. (Catelyn at the Red Wedding is the prime example but far from the only.) This is the first time I’ve tried to make a literary connection, but it really works, doesn’t it? Who would bear all that if they didn’t have to? (There’s a whole other meta here that I can’t seem to finish.)

But the counter image to the face of sorrow, pain, horror and wrath in most Heart Trees is the image of the Laughing Tree, as born by the mystery Knight Lyanna Stark:

Much as he wished to have his vengeance, he feared he would only make a fool of himself and shame his people. The quiet wolf had offered the little crannogman a place in his tent that night, but before he slept he knelt on the lakeshore, looking across the water to where the Isle of Faces would be, and said a prayer to the old gods of north and Neck …” (……)

“No one knew,” said Meera, “but the mystery knight was short of stature, and clad in ill-fitting armor made up of bits and pieces. The device upon his shield was a heart tree of the old gods, a white weirwood with a laughing red face.” (…)

When his fallen foes sought to ransom horse and armor, the Knight of the Laughing Tree spoke in a booming voice through his helm, saying, ‘Teach your squires honor, that shall be ransom enough.’ Once the defeated knights chastised their squires sharply, their horses and armor were returned. And so the little crannogman’s prayer was answered … by the green men, or the old gods, or the children of the forest, who can say?” (ASOS, Bran II)

The answer is not vengeance, no. It is not eye for an eye, son for a son. It is not fire and blood. (Looking at you, Doran Martell.) That’s the path to chaos and dragons.

The answer is justice. It is a pay-it-forward: teach them to be better. Forgiveness. Mercy.

Ellaria’s cheeks were wet with tears, her dark eyes shining. Even weeping, she has a strength in her, the captain thought. “Oberyn wanted vengeance for Elia. Now the three of you want vengeance for him. I have four daughters, I remind you. Your sisters. My Elia is fourteen, almost a woman. Obella is twelve, on the brink of maidenhood. They worship you, as Dorea and Loreza worship them. If you should die, must El and Obella seek vengeance for you, then Dorea and Loree for them? Is that how it goes, round and round forever? I ask again, where does it end?” Ellaria Sand laid her hand on the Mountain’s head. “I saw your father die. Here is his killer. Can I take a skull to bed with me, to give me comfort in the night? Will it make me laugh, write me songs, care for me when I am old and sick?”

(…)

The prince gave her a curious look. “She understood more than you ever will, Nymeria. And she made your father happy. In the end a gentle heart may be worth more than pride or valor. Be that as it may, there are things Ellaria does not know and should not know. This war has already begun.” (ADWD, The Watcher)

Ellaria Sand, lady of my heart. You tried. You tried so hard. Some pains you simply have to bear. Some wrongs you simply have to let go. Not all, not to the point of further injustice. But there has to be an end to the wrath. Sometimes you just have to wade through the pain in order to emerge on the other side and be able to see the brightness, the future, the joys.

Lyanna made it happen for a moment. I think the Starklings will make it happen again.

I am willing to bet the value of a sizable cake that the heart trees on the Isle of Faces are smiling.

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

●• To be, or not to be, that is the question:

Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles

And by opposing end them. To die—to sleep,

No more; and by a sleep to say we end

The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to: 'tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wish'd. To die, to sleep;

To sleep, perchance to dream—ay, there's the rub:

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come,

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause—there's the respect

That makes calamity of so long life.

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time,

Th'oppressor's wrong, the proud man's contumely,

The pangs of dispriz'd love, the law's delay,

The insolence of office, and the spurns

That patient merit of th'unworthy takes,

When he himself might his quietus make

With a bare bodkin? Who would fardels bear,

To grunt and sweat under a weary life,

But that the dread of something after death,

The undiscovere'd country, from whose bourn

No traveller returns, puzzles the will,

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others that we know not of?

Thus conscience does make cowards of us all,

And thus the native hue of resolution

Is sicklied o'er with the pale cast of thought,

And enterprises of great pitch and moment

With this regard their currents turn awry

And lose the name of action.●•

#photography#selfie#self luv#love#s#shakespeare#william shakespeare#self#self portrait#myself#photo#art#photographs

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

toubee or tubbo? that is the question

Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune 1, Or to take arms against a sea of tubbos And by opposing end them. To die—to sleep, No more; and by a sleep to say we end The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks That flesh is heir to: 'tis a consummation Devoutly to be wish'd. To die, to sleep; To sleep, perchance to Dream—ay, there's the rub: For in that sleep of death what Dream may come, When we have shuffled off this mortal coil, Must give us pause—there's the respect That makes calamity of so long life. For who would bear the wilburs and schlatts of time, Th' oppressor's wrong, the proud man's contumely, The pangs of disprized love, the law's delay, The insolence of office, and the spurns That patient merit of the unworthy takes, When he himself might his quietus make With a bare bodkin? Who would fardels bear, To grunt and sweat under a weary life, But that the dread of something after death, The undiscovere'd country, from whose bourn No traveller returns, puzzles the will, And makes us rather bear those ills we have Than fly to others that we know not of? Thus conscience does make cowards of us all, And thus the native hue of resolution Is sicklied o'er with the pale cast of thought, And enterprises of great pitch and moment With this regard their currents turn awry And lose the name of action.

2 notes

·

View notes

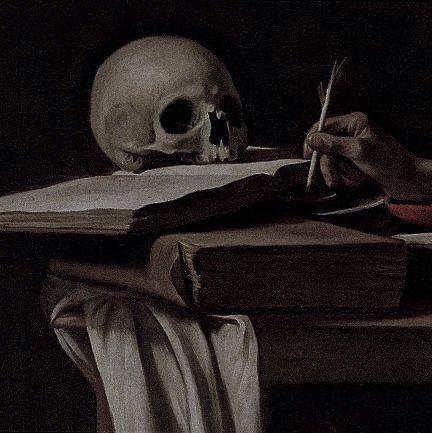

Photo

To be, or not to be, that is the question

“To be, or not to be, that is the question: Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, Or to take arms against a sea of troubles And by opposing end them. To die—to sleep, No more; and by a sleep to say we end The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks That flesh is heir to: 'tis a consummation Devoutly to be wish'd. To die, to sleep; To sleep, perchance to dream—ay, there's the rub: For in that sleep of death what dreams may come, When we have shuffled off this mortal coil, Must give us pause—there's the respect That makes calamity of so long life. For who would bear the whips and scorns of time, Th'oppressor's wrong, the proud man's contumely, The pangs of dispriz'd love, the law's delay, The insolence of office, and the spurns That patient merit of th'unworthy takes, When he himself might his quietus make With a bare bodkin? Who would fardels bear, To grunt and sweat under a weary life, But that the dread of something after death, The undiscovere'd country, from whose bourn No traveller returns, puzzles the will, And makes us rather bear those ills we have Than fly to others that we know not of? Thus conscience does make cowards of us all, And thus the native hue of resolution Is sicklied o'er with the pale cast of thought, And enterprises of great pitch and moment With this regard their currents turn awry And lose the name of action. “

-from Hamlet, by William Shakespeare

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

To be, or not to be? That is the question—

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And, by opposing, end them? To die, to sleep—

No more—and by a sleep to say we end

The heartache and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to—’tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wished!

To die, to sleep.

To sleep, perchance to dream—ay, there’s the rub,

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause. There’s the respect

That makes calamity of so long life.

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time,

Th’ oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely,

The pangs of despised love, the law’s delay,

The insolence of office, and the spurns

That patient merit of th’ unworthy takes,

When he himself might his quietus make

With a bare bodkin?

Who would fardels bear,

To grunt and sweat under a weary life,

But that the dread of something after death,

The undiscovered country from whose bourn

No traveler returns, puzzles the will

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others that we know not of?

Thus conscience does make cowards of us all,

And thus the native hue of resolutionIs sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought,

And enterprises of great pitch and moment

With this regard their currents turn awry,

And lose the name of action.

—Soft you now,

The fair Ophelia!

—Nymph, in thy orisons

Be all my sins remembered.

why would you type out the to be or not to be soliloquy from act 3 scene 1 of hamlet just to send it to me

0 notes

Quote

Hamlet To be, or not to be, that is the question. Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune Or to take arms against a sea of troubles, And, by opposing, end them. To die, to sleep, No more, and by a sleep to say we end The heartache, and the thousand natural shocks That flesh is heir to ; 'tis a consummation Devoutly to be wish'd. To die, to sleep, To sleep, perchance to dream, ay, there's the rub. For in that sleep of death what dreams may come, When we have shuffled off this mortal coil, Must give us pause. There's the respect That makes calamity of so long life. For who would bear the whips and scorns of time, Th' oppressor's wrong, the proud man's contumely, The pangs of despis'd love, the law's delay, The insolence of office, and the spurns That patient merit of th' unworthy takes, When he himself might his quietus make With a bare bodkin ? Who would fardels bear, To grunt and sweat under a weary life, But that the dread of something after death, The undiscover'd country, from whose bourn No traveller returns, puzzles the will, And makes us rather bear those ills we have Than fly to others that we know not of ? Thus conscience does make cowards of us all, And thus the native hue of resolution Is sicklied o'er with the pale cast of thought, And enterprises of great pitch and moment With this regard their currents turn awry And lose the name of action. Soft you now, The fair Ophelia ! Nymph, in thy orisons Be all my sins rememb'red.

Shakespeare

4 notes

·

View notes