#and Hereward was an Anglo-Saxon

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

do all the role swap guys have new personas?? :o is it spoilers to ask what they might be?? i loved the ophelia idea

I can tell you! :D also thank you omg! Ophelia means a lot to me as a character and honestly I was just like WE NEED HER!!!! I AM PUTTING HER IN!!!!

all the personas in the roleswap AU are ones which have an element of either tragedy or strife to them, whether it's in their lore or their personality!

I've listed them below in the format of "[first persona] + [seconds persona unlocked at max friendship] + [third persona unlocked in third sem under certain conditions]" and a "?" just means I have yet to confirm what the persona is. if the person isn't listed it just means I haven't chosen any of their personas yet 😭

Haru can obviously use any persona because she's the wild card/fool but she still has her 3 personas just like Joker does in canon. Akira and Goro also keep their third personas for story purposes.

I'm also not explaining why I chose any of them (though I have linked their SMT wiki page if they have one!) but if you do want to know, send me an ask! :D

Haru: Eurydice + ? + ?

Akechi: Mórrígan + ? + Hereward

Futaba: Slammer (computer virus) + ? + ?

Morgana: ? + ? + Adam (NOT Adam Kadmon)

Makoto: Ophelia + Rapunzel + Vivian

Akira: Dick Turpin + ? + Raoul

Ann: ? / Medusa + ?

#IYR/RTG#anon#ask#if anyone has any ideas for personas you are absolutely 100% more than welcome to tell me!!!#especially if you can find a way to link Akechi's into an evolutionary line lol#I don't want to use Cu Chulainn but they might be the only fit :(#I was trying to find someone from Scottish or Welsh mythology#seeing as Mórrígan is from Irish mythology#and Hereward was an Anglo-Saxon#also Jazzy and I were this close to giving Futaba Among Us#someone suggested Carmen Sandiego for Ann and I don't know enough about CS but if anyone else wants to second their suggestion I'll listen!

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sovngarde is the Battle Anthem Song of King Harold Godwinson's Anglo-Saxon England Epic in 1066! Harold Godwinson is the Dovakhin! Edyth Swannesha is Sovngarde! Harold Godwinson is the Sun! Edyth Swannesha is the Moon! Harold Godwinson's Battle Flag is the Wessex Wyvern! Anglo-Saxon Knecht 🦢 of Orfeo Power and Glory Sidney Empire and Glory 🦢⚜️❄️⛩️🦉💎 Harold Godwinson's Anglo-Saxon Imperial Huscarl Armies Fought like Lions the Epic Battle of Fulford, the Battle of Stamford Bridge, the Battle of Hastings, the Battle of Wales, the Battle of Northumbria and Defended the North from Guillaume le Batard's Cruel Harrowing of the North! Sovngarde is the Magic Battle Song of Queen Edyth Swannesha, the Anglo- Saxon Arch Witch of the Universe, Hexe of Anglo-Saxon England and the North, Gospodarka na Slavata i Svobodata, Lady of Mercia and Sussex and the Realm for the Anglo-Saxon War against the Norman Arch witch in the Norman Camp below Senlac Hill! Queen Edyth Swannesha Had Gothic Astral Drakoness in the Air Like in Van Helsing! Edyth Swannesha is the Dovakhiness! I'm Sent Here by Goddess Freyja! I'm Sent Here by Divine Providence and Lords of Light! Vladitsite na Nebesata! I'm in Samadhi Superconsciousness and Kaivalya Power! Sovngarde is the Anglo-Saxon War Song of Eorl Edwin and Morcar, Eorl Gyrth Godwinson and Eorl Leofwine Godwinson, Lord Siward, Hereward the Wake and Robin of Locksley and Wat Tyler and Thomas Wyatt the Younger's Battles' Wars, Skirmishes and Campaigns even in Uprising were for Liberation of England from the Normans and the Spaniards! Sovngarde is the Battle Anthem of Sir Philip Sidney's Divine Star Society and Order of the Drakon fov the war in Holland against Spain! The Revenge War for the Fate of Queen Jane Grey and King Guildford Dudley of England, Wales, Ireland and France! It's a Samadhi Heaven Song! Sovngarde is the Battle War Song of King Sigismund von Luxembrourg's Crusade of Nicopolis of a Pan-European Crusader Army Mainly French and Hungarian against the Turks of Sultan Bajaseth for Liberation of Bulgaria and the Saving of the Byzantine Empire and Constantinople! All of My Crusaders are Dovakhins and Samurai Knights, the Knights of the Drakon! It's 624 Yearss of Greatness of the Order of the Drakon! Bulgaria is a Free Country for 142 Years! I Live in Sofia, Bulgaria and I am a Free Man! The Dovakhin is an Archangel and a God! Az sam Gospodar na Slavata i Svobodata! Sovngarde is the Battle Song of Emperor Timur the Great's Timurid Army and Horde for the Battle of Angora in Which He Decisively Defeated the Turks of Sultan Bajaseth, Captured the Cruel Sultan and Put Him in a Cage! It was the Revenge of King Sigismund von Luxembourg and Count Jean de Nevers for the Decisive Crusader Battle of Nicopolis, and the Treatment and Fate of My Knights and Army by the Cruel Turks! I Shall Conquer with Angels and with Gins, with Archangels and Knights and Ladies for Everything that Has Happened to Me in Bulgaria! Beowulf el Elyon Shall Love and Defend Me! This is Knight Tervel Kamenov's Epic War Song the Mount Kailash Pan-Gaian Epic, Alone with Mikael the Great, Like Vlad Dracula, Gabriel, that Saved Gaia and the Universe! Beowulf Loves and Defends Mount Kailash! Let the Echoes Become Your Strenght! What You Do Echoes in Eternity! Let Your Actions Echo in Eternity! Hail Goddess Crystine Slagman, final Crystine! Hail Sovngarde Lord and Bard Orpheus, Jeremy Soule! I'm Always on the Side of Divine Providence and Divine Providence is Always on My Side! Promote Only Nobility, People! Fight for Love, Freedom and Nobility! Hail Goddess Crystine Slagman! Reward! Nagrada! I'm the Lord of Fortune Better than Boethius! Rex Tvmundos Majestatis, Qu Salvandos Slava GRatis, Salva Me Fons Pietatis, Salva Me Fons Pietatis! O King of Tremendous Majesty, who Save s wwithout Price Those Destined to Be Saved, Save Me Font of Piety! I'm a Legendary Hero of Hoary Glory, Lord of the Anglo-Saxon Folk and Nation, Kingdom and Anglo-Saxon Empire Worldwide, the British Empire!

#edyth swannesha#lady of the rose#bulgaria#art#nature#afina ariosofia#belisarius#lady of the lake#Anglo-Saxon England#yoga#self#isabella bronstrup

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fyrthœr bookes fyr the færestę mayden tew consydre (@lapokinanaz)

1. Troilus & Cressida (Shakespeare; tho’ there’s also a rendition by Chaucer)

2. Hereward the Wake (Anglo-saxon hero legend)

3. Cúailnge (Celtic hero legend)

The above two however may be included in a volume of British/Celtic legends, so be wary in your query.

4. Y Gododdin

5. Bulfinch’s Mythology

6. The Howard Collector

7. A volume of Lewis Carrol (including Jabberwock)

8. The Metamorphosis and other stories (Kafka)

9. The One (Rick Veitch, comic)

A surprising Christian allegory

10. A Dictionary of Angels (Gustav Davidson)

11. a volume of ancient English poetry 🏴

2 notes

·

View notes

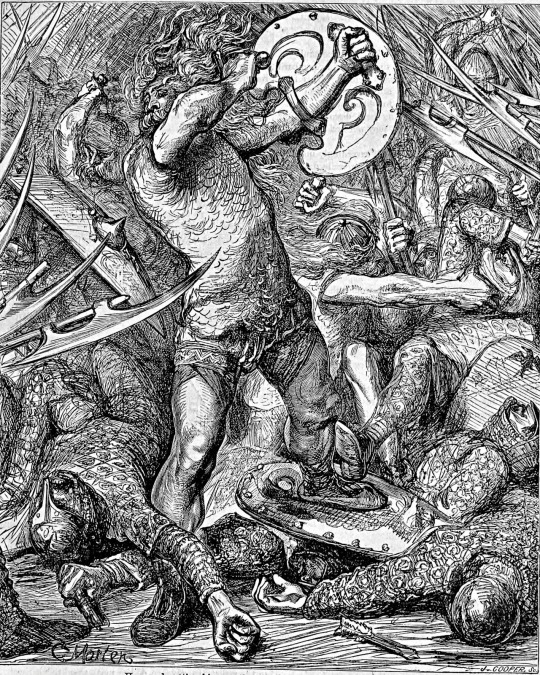

Photo

Guillaume le Conquérant et la rébellion d'Ely

Au début de l'année 1070, Guillaume le Conquérant (r. de 1066 à 1087) avait presque achevé la conquête normande de l'Angleterre. Les régions frontalières avec le Pays de Galles et l'Écosse constituaient toujours une menace, mais le nord de l'Angleterre avait finalement été soumis grâce au harcèlement impitoyable de cette région au cours de l'hiver 1069-1070. Malheureusement pour Guillaume, son autorité se heurta à un autre obstacle de taille. Il s'agissait de l'invasion de l'est de l'Angleterre par une armée dirigée par le roi danois Sweyn II (r. de 1047 à 1076), qui donna aux quelques rebelles anglo-saxons restants, menés par Hereward l'Exilé, une dernière chance de s'opposer au nouvel ordre normand du roi en Angleterre. Le point central de cette dernière rébellion était l'abbaye d'Ely, en Angleterre orientale, mais, comme pour les nombreuses rébellions des cinq années précédentes, Guillaume fut victorieux et, à l'été 1071, la conquête fut enfin achevée.

Lire la suite...

1 note

·

View note

Text

For Option B (which is what the polls are leaning towards), it's not really either. Basically, the way I envision it is set about 100 years after the return of magic, with Britain having split into a bunch of different mini-states; the whole idea is to combine different periods, regions, figures and bodies of folklore into one giant British folklore crossover.

So far, what I've settled on:

During the initial collapse, King Arthur returned from Avalon with a company of knights (mostly Welsh ones that the French authors diminished, such as Gawain, Kay and Culhwch), and has now built a kingdom in the West Country, based around Camelot, rebuilt atop the hillfort of Cadbury Castle, and with a broadly High Medieval feel, technology and structure.

However, there's a breakaway; Mordred and Lancelot both allied with the aim of taking Gwenhwyfar (Guinevere to English and French speakers) - which one of them will actually get her will be decided later - and run a rebel kingdom in Cornwall with an army of spriggans, mermaids, giants, pixies, buccas, Dando's dogs and so on, centred on Tintagel Castle and with the support of Lancelot's foster mother, the Lady of the Lake.

Wales is split three ways; the north is Cymru and is a medieval kingdom run by Owain Glyndŵr, the southeast is Wales, the remnant of 21st century Wales and the southwest is Annwn, a kingdom of tylwyth teg run by Gwyn ap Nudd.

I don't know what's going down in the Midlands yet, but Robin Hood and his Merry Men will definitely be there, and at least part of the West Midlands will be the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Mercia, with Wild Edric and Lady Godiva.

The Southeast is the home of the remnant of Britain's old government; however, they realised that World War Two was effectively part of British folklore, and so they could gain magical power to compete with the others by tapping into it. Hence London has been rebuilt to consist mostly of gun platforms, air raid shelters and London Underground stations, everyone is on rationing and the government is lead by Winston Churchill.

East Anglia has reverted to fenland and is hence largely underwater and full of will-o'-the-wisps, shug monkeys, Black Shuck and whatnot, with (literal) islands of civilisation in the marsh, with the only notable cities being Cambridge and Norwich. The southeast, which still calls itself the United Kingdom, is trying to conquer and/or drain here, but is being thwarted by both the monsters, the hostility of the region and parties of guerrillas led by Tom Hickathrift and Hereward the Wake.

Northern England has the Republic of York, where Yorkshire has dominated most of it; I'm not sure what that'll be like, but I'm pretty confident it will have a 19th century vibe and that Mother Shipton will be there.

The Isle of Man has Manannán back, and he's looking after the island with his mists; the locals use this to become a major centre for piracy, lead by Francis Drake.

On the Scottish Borders, the Border Reivers are back, and Dumfriesshire and Galloway are now home to Elphame, a faerie kingdom with Thomas the Rhymer as its emissary.

The Central Belt of Scotland is a Late Medieval kingdom run by William Wallace, although he has to deal with Sawney Bean's clan expanding over southern Ayrshire, plus he's made Michael Scot (click on the link, it's not the one from The Office) king of his own personal fiefdom in Selkirkshire in exchange for fighting against ...

The Cailleach, who has taken over the Scottish Highlands and filled it with forests, magic and monsters and is attempting to expand.

Northeast Scotland is now the Republic of Aberdeen, which is trying to preserve modernity.

Clan MacLeod has made use of the Fairy Flag to make an alliance with the faeries; the two frequently intermarry and now govern the islands of Lewis and Skye.

The Shetlands and Orkneys are now Nordøjar, the neo-pagan Norn-speaking Viking islands.

In general:

Historic forests - the New Forest, Sherwood Forest, Forest of Dean and Wistman's Wood - have all greatly grown.

Welsh, Cornish, Manx, Scots, Scots Gaelic and Norn have all experienced revivals.

Modern technology, especially guns and computers, has stopped working; I'll need to figure out why later.

As people who've been following this blog for a while will know, I love British folklore. You may also know that I love writing and worldbuilding. The two come together in that I'd want to make a fantasy world based on British folklore. My conflict is I'm not sure which one.

Option One: A total fantasy world untethered from real history, politics, geography, and so on, utilising equivalents of people, places, cultures, etc.

Option Two: A kind of post-apocalyptic Britain where the magic comes back and the world gets restructured in the chaos, using specific real-world places, cultures, folklore characters, etc.

The advantage of option one is that I get to be more creative (I've already started working on the calendar and liturgy of this setting's version of Christianity) but I also have to do more heavy lifting for the reasons mentioned above and have to invent counterparts to folklore figures like Robin Hood, the Cailleach, Owain Glyndwr, etc., as well as to particular places, which just don't have the same impact as the real figures. Invert those for the advantages and disadvantages of option two.

Tagging @narulanth and @kaleb-is-definitely-sane because it feels like you'd have opinions on this.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hereward the Wake

Also known as Hereward the Outlaw or Hereward the Exile was an Anglo-Saxon nobleman and leader of local resistance to the Norman Conquest of England. According to legend he roamed the Fens, which now covers the parts of the modern counties of Cambridgeshire, Lincolnshire and Norfolk, leading popular opposition to William the Conqueror.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

the bocs and the preosts the bells the laws of the crist it is not lic they sae

to the cros road i walc to the wilde cros road by the wilde grene holt where there is no hus of man and at the cros road a man hangs from a pal for crimes agan his folc by law of the wapentac after ordeal and beneath this pal is an other man and this man he lifs

this man capd he is in grene and he wers upon his heafod a wid hat and until i is near i can not see his nebb. and then he teorns to me he locs at me with his one eage one beornan eage

upon the pal then there is a raefen

from the holt then a wulf calls to an other

this man then he specs to me

i is the eald one

dweller in the beorgs

i walcs the high lands

i macs the hwit hors and the hwit man

i is forger of wyrd and waepen

cweller of cyngs

i walcs through deop water to cum to thu

name me

The Wake, by Paul Kingsworth

A post-apocalyptic novel of 1066 written in a “shadow tongue” version of Old English updated so as to be comprehensible to the modern reader.

#paul kingsworth#1066#norman conquest#anglo saxon#sorta#old english#anglish#history#post apocalyptic#the wake#hereward the wake#germanic#germanic mythology#historical linguistics#philology#my stuff#medieval#middle ages#medieval europe

34 notes

·

View notes

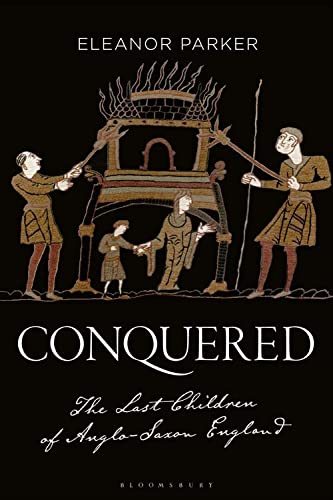

Photo

Conquered: The Last Children of Anglo-Saxon England

There are many books, both scholarly and popular, that discuss one of the most seminal events in English history: the Norman Conquest of 1066. Perspectives of the Anglo-Saxons, the French, the Normans, and the various populations living in Wales and Scotland are all available for perusal. Recent historical studies of this time period have provided opinions and viewpoints that were once ignored. As history has often shown, it is the viewpoint of the victorious side in a war that usually dominates recordings, and that of the defeated side is lost or purposefully suppressed. Eleanor Parker's book provides a platform for a subtopic under the Norman Conquest that has rarely been explored: what happened to the children of critical Anglo-Saxon families and royalties who were uprooted, disinherited, imprisoned, and hunted down after the Conquest.

Eleanor Parker's book provides a platform for a subtopic under the Norman Conquest that has rarely been explored...

The book's Introduction provides important background information on how Anglo-Norman elites were careful when integrating aspects of Anglo-Saxon society and life into their reign as well as suppressing other cultural and religious observances of the conquered people. Eleanor Parker indicates that intermarriage with aristocratic Anglo-Saxon women, for instance, was key for Anglo-Norman elites to legitimize their claims over English territories. The subsequent five chapters of the book focus on the specific stories of Anglo-Saxon individuals and families and their reactions to their reduced or eliminated status in the new Anglo-Norman society after 1066. Chapter One tells the story of England’s most illustrious rebel and hero Hereward the Wake, who led a guerrilla campaign against the Normans in the Fens in Eastern England. Chapter Two focuses on Margaret of Scotland. She was the sister of Edgar Aetheling, the last surviving direct heir to the English throne. After fleeing to Scotland, Margaret married Malcolm III and became an influential queen. Chapter Three contains a fascinating story. It talks about how the lives of the nine grandchildren of Godwine, the late Earl of Wessex and husband to Gytha Thorkelsdóttir, were virtually wiped out overnight due to the events in 1066. Their stories of exile, rebellion, and marriage are documented by Parker's engaging writing style for readers interested in following the fortunes of Harold Godwineson and his extended family.

Continue reading...

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Septimus Heap is set in my home town and if we ignore the authors intentions I can prove it

Some brief disclaimers, I know that technically the books are set in the far future, and with water levels rising could not possibly be set in my area, but death of the author and all that, there’s enough evidence that I have thought of Septimus Heap as local to me since I was maybe 13. Also its been years since I read these books so I may have forgotten some pieces of evidence or have some plot details wrong, but this has been on my mind for years at this point. What else, ah yes, not doing this on my main account because I don’t fancy giving out specific information on where I live, because yikes. Finally, while it may not be my home town specifically, I do certainly feel it is my local area ie the Fens in East Anglia (UK)

Septimus Heap is set in Ely in the 12th century. I have two main pieces of evidence for this, the geography and history of the area (shocking I know). I’ll try not to go into unnecessary levels of detail, but no promises.

I grew up (and currently live) in Littleport, a small town/large village just outside Ely in Cambridgeshire. The main geographical feature of the Ely area are the fens. I dont know how common a term fen is so you’ll forgive me if I explain, a fen is a great big wetland, or marsh, if you will. Now the fens were drained sometime in the 1600s, and before that most of the area was underwater. This is why, even though we’re around an hours drive from the sea, all the place names sound like they’re from a waterfront, LittlePORT, ISLE of Ely, WATERBEACH, and also why I don’t think its set in Ely specifically, but instead, close by, but I’ve got to have a catchy title you know. Growing up I always pictured the Marram Marshes as one of the surviving fens, namely Wicken Fen or the Welney Wetland Centre (neither of which can I find good pictures of right now, why are people taking pictures of the walkable paths and not the views of the fens themselves) which we used to visit often when I was younger. Now I’ll admit that this isnt very strong evidence on its own, swamps aren’t an uncommon thing, and even the surviving fens are nowhere near as flooded as they used to be , so its easy to dismiss that they could be the marram marshes, and if it wasn’t for some of the local history I’d be inclined to agree with you that this is a bit of a reach.

Before jumping into the history I do just briefly want to say that the rest of the local geography also lines up, but where in the UK wouldn’t it. Lots of nearby farmland, and if you travel a little bit plenty of forests (there aren’t really any here specifically because as a consequence of being a fen we have very high quality soil for farming, so it is mostly fields until you get out of the fens specifically, but I don’t think that’s a big deal for my theory.

Now, Angie Sage doesn’t seem to pull from the areas history in general, but there are two characters who’s names either are, or are very close to, prominent figures in Ely’s early history, and its not like they’re common names either. Additionally the lifetimes of these two historical figures seem to line up with their book counterparts well enough for me to give the specific time period of the 12th century. I’ll go through and give a couple of details on each of them in the order in which they appear in the books (which is also reverse historical order, and if I remember correctly, the reverse of how significant they are as characters).

Up first we have everybody’s favourite ghost, Sir Hereward, and his real life counterpart, Hereward the Wake who died around 1072 according to Wikipedia, so important is Hereward to Ely that they even have a pub named after him (but don’t go thinking we’re cool, there is also a small museum dedicated to Oliver Cromwell). For those who didn’t take the Anglo-Saxon/Norman invasion unit of GCSE history, Hereward the Wake was an Anglo-Saxon who led a rebellion against William the Conqueror, the most successful one of them all in fact. The rebels took shelter in a monastery in Ely, or more accurately on Ely which was, at that point an island that only locals could navigate the fens to get to. Many a Norman died trying to cross the waters, until the monks eventually led them across safely. This rebellion is also where every web-toed fen dwellers favourite story comes from, that of William the Conqueror getting a witch to cast a spell on the rebels, which involved her sticking her butt in the air, but I digress.

And then there’s Etheldredda, counterpart to Saint Æthelthryth or as I always heard her called, Etheldreda. I have no idea what she did in her life, but she was a resident of Ely and gained sainthood because she kept her vow of virginity even through marriage. She’s important enough to the history of Ely that my secondary school, Ely College, named a house after her, it may have been the shittest house house, but it was a house none the less. Anyway, she died around the year 679, again, according to Wikipedia, and 500 years later its the 12th century, and my understanding is Queen Etheldredda was born around 500 years before the book she appears in.

Anyway, thats my evidence, like I said, there might be more but its been a while since I read these books. I know the character’s histories and the histories of the real life people don’t really line up, but does anything else? Feel free to let me know what you think, am I insane or is there merit to this belief I’ve held since since I was 13?

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

if i had a anglo saxon or any other medieval name my life would be sooo much better

like come on, ælfric, eastmund, hereward, achard, arthfael, gwenhael, ranulf, rémann, treasach, wymond, wilfrith, wilheard

too many good options

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi, i remember there being a post somewhere about the origins of some of the mechs' more obscure songs- like hereward, or drop dead, actaea and lyssa- but i can't seem to remember where i found it. would you happen to know / have a link to is?

i don’t have a link to it, but- and please note i am going off of my personal knowledge of the sources here, not clarification by the mechanisms- hereward is based on a historical anglo-saxon nobleman and, if i recall correctly, the sci-fi series the expanse, drop dead is based off of the video game crypt of the necrodancer, and actaea and lyssa is based off of the (unrelated) greek myths of actaeon and lycaon, reframed to be in the world of ulysses dies at dawn. (edit: this was reblogged with a link, as well as the theory that it was just the myth of actaeon, which makes more sense, here).

a large portion of the songs in tales to be told volume ii were commissioned by people as kickstarter perks, so that’s why they can be so odd in their subject material.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alright brace yourselves because I feel a fittingly hot take for High Noon Over Camelot coming on

The destruction of Fort Galfridian was not the end, and the legacy of Arthur and his knights lives on. This is a canonically supported reading.

On Tales to be Told Volume 2, there’s a little track called Hereward the Wake. It tells of a man who lives among the asteroid belts, leading a heroic resistance against the planet-dwelling invaders that are trying to conquer the space colonies. Nice little ditty, and the stinger is funny. Okay.

The real Hereward, both the real person Hereward and the real mythical Hereward, was a Saxon.

History time: The Angles and the Saxons conquered Britain after its abandonment by the waning Roman Empire (though the possibly fictional Artorius held them at bay for the duration of his reign), only to be conquered by the Normans in turn. Hereward was a major figure in the resistance after the Saxon king was slain at the Battle of Hastings, fighting for many years, escaping Norman hunts and in many versions, living to a ripe old age.

Fort Galfridian was made in the ancient’s home system: “Long ago, a star-faring civilisation decided to build a space station of unparalleled size and power, in close orbit to their star, Avalon.” So there’s presumably an inhabited planet kicking about in the system somewhere.

“On the commlink there’s just static, every colony the same.” So there’s other habitats out there, too. And just because they can’t respond to Galfridian’s calls or reach the station doesn’t mean they can’t hear them. It is, after all, unparalleled in size and power.

So there might well be other survivors in the system Fort Galfridian resides in. And the Saxons live on the outer levels of the station, nearest space: “The cruel Sheriff and her kin were dead, their bodies tossed to Annwn, the lightless levels of the outer station, where the ghouls lurked and feasted on corpse meat.” So if anyone is going to be in a position to try and leave, if anyone is going to be desperate enough to do so, it’ll be them. Potentially, some of the ghouls could have gotten away using whatever scavenged tech they could strap together in the old shuttle bays, and mingled with the survivors of the asteroid belt colonies (the Angles).

Headcanon: When Mordred brought everything down, when he sang out the dirge at the end of Once and Future King and rode his rotten world into the sun, he also broadcast everything that had happened out into the aether using the systems and senses provided by the GRAIL, where it was picked up by the asteroid belters, who have had better luck recovering.

So the Anglo-Saxons knew that there had been brave warriors upon Fort Galfridian who fought for its salvation, who for a time were a source of peace and stability, and who went on a desperate quest to repair the station which could have rebuilt civilization in the Avalon system. That they nearly won, that there had been hope for a brand new dawn and that if people had been able to understand each other and work together, there could have been, could yet be a happy ending.

And just as the original Arthur was a Welsh tale appropriated by the Saxons and Normans and everyone else even up to the modern day, the asteroid belter Anglo-Saxons took up the tale, telling stories of those who had been enemies to their ancestors...but who, if things had gone better, could have been friends.

And you could have people like Hereward, a far-flung cousin of Mordred’s adopted people, being inspired by his people’s tales of Mordred’s father. Not the alliance and union Mordred hoped for, of course, but...

It’s something.

#The mechanisms#high noon over camelot#arthurian legend#Arthurian myth#Hereward the wake#folklore#ranting about sci-fi concept albums#what even am I at this point#seriously though I'm right#(also he fought a bear!)#spoilers

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Since @theaurorastrikes asked when I posted my HNOC family tree, here’s an overview of my UDAD/HNOC connection (now with TBI as well), based on the history of their source material:

Contrary to what Ulysses believed, there was actually a single survivor of Ilium, the illegitimate child of the Olympian Aphrodite, Aeneas. His mother helped him escape the wrath of the City, and he hid in the lower levels for a few decades. Then, when the Mechanisms left the City, and destroyed the Acheron when they left, it was Aeneas who helped provide a new society in the ruins of the old. It took a few generations, but eventually Rome controlled the City, and brought back the old stability.

The Acheron was never recreated, and in Rome, there were very few technologies based around AI and neurology- a Siege Seat was the closest they ever got. Likewise, the Olympian's method of immortality was also lost, although many Emperors and other powerful people would often get their hands on elements of it, lengthening their lives and increasing their durability. But very few Emperors even got the chance to get close to dying of old age. The story of Rome is sourced not from Roman mythology, but from Roman history.

Rome began to stretch across the stars, establishing one or two planetary colonies, but mostly building space stations, such as Fort Galfridian.

But then, the Disaster happened. The system containing Rome’s Empire (Occidental, perhaps?) was far enough away from Yddgrasil that Yog-Sothoth didn’t consume them, but they still felt the metaphysical fallout from it. All of their FTL communication and transport systems were damaged, cutting off the settlements from eachother.

Shortly after the Disaster, some refugees arrived in Fort Galfridian. They were the only survivors of Yddgrasil (except Lyfrassir), miners lucky enough to already be at the colonies when Yog-Sothoth emerged. Since things hadn’t gone bad yet, Captain Mathea welcomed them, despite the objections of the General. But they were not eagerly welcomed by the Britons, and these refugees would become the Saxons (the historical Saxons were Germanic peoples), explaining the cultural divide between the two. There home located by the weak radiation shielding is a result of their ancestor’s hastily made slums/refugee camps in the gaps of the stations.

Hereward The Wake also takes place in this system. Based on a post I saw a while ago, Hereward was an Anglo-Saxon folk hero who resisted Norman conquest. He came from one of the mining colonies in the asteroid belt that fared better than Fort Galfridian without Rome. By his time, FTL travel/communication has been rediscovered. Rome (planetside) is trying to reclaim control of their old colonies, but the asteroid belt colonies aren’t having any of it.

I haven’t put OUATIS in here, because following the historical stuff, it would be the last album in the chronology. Which, barring a lot more blatant time-travel, wouldn’t work with the Toy Soldier’s origin. Or Jonny’s (based on my headcanon that New Texas is in the same society as New Constantinople). Also, Narcissus as a copy of a book version of OUATIS.

#the mechanisms#the mechs#udad#Ulysses dies at dawn#hnoc#high noon over camelot#the bifrost incident#tbi

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Regarding Robin Hood and his opposition to the king and aristocracy, is it known whether there was an ethnic (for lack of a better term) component to his program (basically a latter-day Hereward the Wake)? In other words, did he oppose the king and nobles because they were foreigners, or would he have just as happily robbed a hypothetical Godwinson king and Anglo-Saxon lords?

Great question!

Kind of impossible to know for sure, given that Robin Hood’s legend as far as we can tell started well after the Norman Conquest.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guest Post: Will the Last of King Harold’s Housecarles Please Form an Orderly Queue

Will the Last of King Harold’s Housecarles Please Form an Orderly Queue

By

Richard Toogood

It doesn’t require a particularly robust grasp of the past to recognise and understand the significance of the year 1066. It is one of the most famous dates in history. The year of the three kings and the three battles. It bore witness to the Norman Conquest of England and by so doing laid the foundations of Great Britain. Equally significantly, by reorienting the political compass of England away from Scandinavia towards the continental mainland it is no exaggeration to say that it had profound ramifications for the entire course of European history, ramifications which extend right up to the present day.

The story of 1066 then is one of monumental events directed by personages of mythic proportions. It defies understanding that Hollywood has never cottoned onto it: Game of Thrones has got nothing on this epic.

But if the film and TV establishments have been negligent in their appreciation of the story’s dramatic appeal then the publishing world has scarcely registered anything better. The number of novels that have drawn creditably upon the story is minimal. Particularly when compared with the tsunami of Arthurian fiction that has washed across the publishing landscape over the years.

Whether one sees the Norman Conquest as the triumph of progress over stagnation or a cultural apocalypse is a matter of personal choice. It is fair to say that both views have retained their power to incite a violent reaction over many centuries. The disenfranchised and the downtrodden have traditionally apportioned the blame for their grievances to the Norman yoke. The disgruntled Levellers, for example, made great play over the point in the aftermath of the English Civil War. For the elite, those privileged descendants of William the Bastard’s triumphant colonels who profited most from the spoils of the Conquest, it was only Norman energy, innovation and ambition that took a bucolic backwater of a country out of the Dark Ages. The Norman Conquest has been the subject of diametrically opposed spins from the moment the first thread was stitched into the Bayeux Tapestry.

It was the Victorians who rediscovered a source of pride in their Anglo-Saxon roots. They it was who erected statues of Alfred the Great, all but venerating him as the architect of British liberties. But the Victorians could not fail to be conflicted in their feelings about the consequences of the Conquest. It is difficult to lament the lost freedoms of an imaginary Anglo-Saxon utopia when one is engaged in the process of an imperialist project of global extent. The compromise they came to was to attribute the success enjoyed in their own times to the amalgam of stoical Anglo-Saxon fortitude with ruthless Norman gusto. In effect what they were saying was that the ruins of Anglo-Saxon England were the necessary foundation only upon which could a greater Britain be built.

This is one of the key inferences which one may draw from Sir Walter Scott’s influential IVANHOE (1820) with its Saxon hero happily committed to service in the retinue of a Norman king. Scott was of course equally committed to the cause of Scottish/English unionism and so was subtly drawing parallels to advance that agenda. Scott’s view was endorsed by later writers such as Charles Kingsley in HEREWARD THE WAKE (1866) and George Henty in WULF THE SAXON (1895), which likewise championed the Anglo-Saxon cause whilst wedded to the idea of the greater Norman good.

One of the more interesting conceits that found favour in Conquest fiction of the 20th century was the idea that Harold Godwinson didn’t actually perish on the field of Hastings but instead survived to pursue a variety of fictional afterlives. This is an idea which actually goes all the way back to a medieval manuscript called the Vita Haroldi. Rudyard Kipling was among the first to utilise this idea, painting a very sympathetic and poignant portrait of the tragic Harold in “The Tree of Justice”, one of his enchanting Puck stories collected in REWARDS AND FAIRIES (1910). Robert E Howard, not a writer exactly renowned for harbouring Saxon sympathies, was equally impressed enough by Harold’s fighting spirit to likewise whisk him away from the carnage of Hastings and repatriate him to Outremer fighting Saracens in the rip roaring “The Road of Azrael”.

Interest in the subject appeared to drain away as the century progressed. It may be supposed that with Britain twice facing the serious possibility of invasion during the first half of the 20th century there wasn’t much of an appetite for being reminded of the last time such an enterprise had actually succeeded. Later years however saw the publication of books as diverse as Noel Gerson’s THE CONQUEROR’S WIFE (1957), Brenda Honeyman’s HAROLD OF THE ENGLISH (1979), John Wingate’s WILLIAM THE CONQUEROR (1983) and Helen Hollick’s HAROLD THE KING (2000).

Quite possibly the most successful conceit to have arisen out of Conquest fiction is the employment of a character claiming to be King Harold’s last surviving housecarle. Housecarles were professional warriors bound by solemn oaths not to outlive their lord on the field of battle. To do so was a mark of the deepest shame and therefore not something anyone in that position was ever likely to own up to. Nevertheless this is one of the premises of Laurence Brown’s HOUSECARL (2001). Another “last” housecarle called Bovi pops up in George Shipway’s brilliant KNIGHT IN ANARCHY (1969). A similar contention underpins Ken Bulmer’s six volume WOLFSHEAD series (1973-1975). Undoubtedly the most commercially successful of these survivors is Walt, hero of Julian Rathbone’s gimmicky yet nonetheless spellbinding THE LAST ENGLISH KING (1997).

As the years begin to count down towards the 1000th anniversary of the Battle of Hastings it is probably fair to say that the Saxon cause seems to be coming into the ascendancy. So much so that James Aitcheson’s recent pro Norman Tancred trilogy seems painfully naive and old fashioned. The ludicrous portrayal of the Saxon hero Edric the Wild found in THE SPLINTERED KINGDOM (2012) little removed from a churlish caricature.

The Battle of Hastings was a close run thing. Had it been fought even a week later, and darkness fallen that much sooner, the probability is that the result would have been completely different. The irony of that is, had that been the case, then the chances are it is a battle that would not now be remembered at all.

Guest Post: Will the Last of King Harold’s Housecarles Please Form an Orderly Queue published first on http://ift.tt/2zdiasi

0 notes