#ancient Greek Panathenaic Games

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A GREEK GOLD OLIVE WREATH LATE CLASSICAL PERIOD TO EARLY HELLENISTIC PERIOD, CIRCA 4TH CENTURY B.C.

Unlike in the modern iteration of the festival, the ancient Olympics only had one winner per competition. Wild olive trees were native to Olympia, the site of the festival, and the arbiters of the games awarded their wreaths (called kotinoi in Greek) to the victor in each event. The association between the olive tree and physical prowess harkens back to a myth of young Herakles, who managed to kill the Cithareon lion using only his fists and a wooden stake from an olive tree. Gold wreaths such as the present example derive from these wearable trophies, but the fragility of the material makes it unlikely that those made from precious metal were meant to be worn in daily life. Rather, they were more likely dedicated in sanctuaries or placed in graves as funerary offerings. Indeed, the melted leaves at the front of this wreath may have been caused by the flames of a funeral pyre.

#A GREEK GOLD OLIVE WREATH#LATE CLASSICAL PERIOD TO EARLY HELLENISTIC PERIOD#CIRCA 4TH CENTURY B.C.#olympics#ancient Greek Panathenaic Games#Ancient Greek Olympics#gold#ancient artifacts#archaeology#archaeologists#history#history news#ancient history#ancient cultures#ancient civilizations#ancient greece#greek history#greek art#ancient art

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

Panathenaic Prize Amphora with Lid, 363–362 B.C.

35 1/4 in.

The Panathenaia, a state religious festival, honored Athena, the patron goddess of Athens. Held in its expanded form every four years, the festival included athletic, musical, and other competitions. Amphorae filled with oil pressed from olives from the sacred trees of Athena were given as prizes in the Panathenaic Games. These amphorae had a special form with narrow neck and foot and a standard fashion of decoration. One side showed Athena, the goddess of war, armed and striding forth between columns, and included the inscription "from the games at Athens." The other side showed the event for which the vase was a prize.

#ancient art#antiquities#greek antiquities#ancient greek#greek gods#greek mythology#olympics#olympic games#athena deity#amphora#athens#greece#ancient greece#ancient greek mythology#getty villa#getty museum#ancient gods#vase#ceramic vase#athena#4th century bc#games#prize#Panathenaic#ancient ceramics#black figure#olive oil

46 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Pasiphae’s Dress

Named after the mythical queen of Minoan Crete. Pasiphae was the wife of King Minos and the mother of the minotaur, Asterion. According to some traditions, she was a goddess of the moon and sorcery.

The dress is based off a ceramic vessel in the shape of a woman’s dress found at the site of Knossos. The skirt depicts crocus flowers near its base.

Prayers for Anna Apostolaki (Άννα Αποστολάκη), who was the first Greek woman to pursue a professional career in archeology. In 1926, she oversaw the reconstruction of ancient Minoan costumes as part of a three day festival held at the Panathenaic Stadium, among which included this beautiful dress.

Long dress category

43 swatches

Base game compatible

Feminine

DRESS DOWNLOAD - Dropbox (no ads)

#my cc#my cas cc#s4cc#ts4cc#crete#cretan#greek#greece#minoan#pasiphae#phaedra#mythology#mythos#history#ancient history#bronze age#mycenaean#mycenae#queen#goddess

266 notes

·

View notes

Note

pls elaborate on athens!

Omg it was so cool!!!!

We went for a sightseeing holiday, because I'm an ancient Greece nerd, so I'm going to just dump about the sights and then move on to other things

I'm going to try and use a cut here for the rest of the post, idk if it's going to work though

So, we went up the acropolis, saw the Parthenon (HUGE, very cool) (I did get confused at the acropolis entrance because it looks like a big temple), the temple of Athena Nike (cool), the Erechtheion (awesome), the place where the first olive tree was (I infodumped a lot this holiday), and we saw the Odeon of Herodes Atticus (thought it was the theatre of Dionysos). We also saw the Theatre of Dionysos from a distance which was cool. On the same day we saw the Temple of Olympian Zeus (bugger than I thought) and Hadrian's Arch, and the Acropolis museum which was really cool (we saw the Caryatids and talked a lot of shit about Lord Elgin). We saw the Roman Agora and Hadrian's Library on the next day, and the day after was the National Archeological Museum and the Benaki Museum. And the next day was the Panathenaic Stadium (stairs to get up to the top were. Scary) and the museum that was there (lots of Olympic torches and posters, plus the mascots from the 2012 games. I was like "hey I know those guys"). And on the last day we saw the Ancient Agora (insanely huge, birthplace of democracy)

Other things that happened: I fell asleep sitting up on the plane there (slept through the worst plane landing of my mum's life somehow). And then standing up on the Metro as well? There are also a lot of stray cats in Greece, but it's less like they're strays and more like they live outside? People feed them and they just wander around, it's really cool.

Also, everything was way closer together than we thought based on the map we had lmao, so on the first day we were like "why is the Parthenon right there, I thought it was ages away"

Iced coffee in Greece? Brilliant, would recommend.

Also I think in Greece they're cool giving teens alcohol if they're with an adult, because a waiter literally told me that on our last day when I asked for a glass of wine, and his eyes bugged out when my mum said I was 20, because he thought I was 16. As I told him, "this happens all the time"

Anyway, Greek food is really good, but I swear I eat less when it's hot, which is very annoying because why can I not eat half a salad and then a whole plate of souvlaki and rice? Why must I be punished in this way?

Also I had an ice cream accident, by which I mean I got two humongous scoops of ice cream and they were okay flavours and then they melted loads and my hands were sticky all the way back to where we were staying.

Also! Hot as FUCK. SO HOT. Flames on the side of my face hot

My recommendation for Athens: do it, but bring SPF 50, white flowy clothes, a hat and sunglasses. Also a hand fan. And don't go places when it's hot in the day, you will regret it. Also plan where your going beforehand and buy your tickets to go places so you have a plan. Also if you are afraid of heights do not go up the Panathenaic Stadium. It is scary.

Also I spent most of the plane back reading Glee fanfiction (specifically "mr schuester belongs in federal prison" because I had the whole work loaded) and then on the drive home from the airport I slept a lot and then woke up to Me Against the Music (GCV) , because I'd put it on the playlist. And then when the next song played I started saying delusional shit because it was like 5am Athens time and I'd had half an hour of sleep

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Flavour of Mechanisation

Olive Oil was Revered and Cherished by the ancients. But its Distinctive Peppery Taste is Really a Modern Invention

— By Massimo Mazzotti | 12 November 2024

Few Foods Can Compete With Olive Oil. Its salubrious properties have turned it into one of the most recognisable symbols of healthy living as well as a sign of tacit resistance to the industrialisation of food and loss of authentic flavours. Its rich history, stretching back to the Greeks, Egyptians and Babylonians, plays an enormous part in its ongoing symbolic associations. Across a range of Mediterranean cultures, olive oil has been an inordinately versatile and useful product, even regarded as a means of connecting with the divine. Today, it sells in pricy green bottles that promise a ‘Mediterranean’ lifestyle. And yet, the distinctive flavour of extra virgin olive oil is a modern invention. The trail of its peppery note leads straight to the core of the Industrial Revolution and the reinvention of olive oil as a global commodity.

Homer calls Odysseus polytropos, a man of many ways, who can transform himself and adapt to any situation. Olive oil is often involved in these transformations, as when, on his return to Ithaca, Odysseus relies on olive oil – and Athena’s intervention – to become younger, stronger and more beautiful. He also carved his wedding bed in an olive tree that had grown deeply into the ground. These references are not incidental: the olive tree and the juice of its fruit are ancient symbols of vitality and rootedness. In Mediterranean cultures they signify adaptation, gnarly endurance and endless transformative possibilities.

Amphora depicting olive-gathering, made in Attica, Greece, 520 BCE. Courtesy the British Museum

First domesticated somewhere in the Fertile Crescent, the tree was cultivated by Babylonians, and by the 18th century BCE the Code of Hammurabi regulated the trade in olive oil. The tree steadily inched west, with its main centres of diffusion in Palestine, Syria and Crete. By the 5th century BCE, Thucydides felt he knew what separated civilisation from barbarism: the ability to graft the olive tree. The mythical foundation of Athens begins with the goddess Athena gifting the olive tree to the Greeks. Planting an olive grove was thus a sacred act. Especially revered were those trees whose oil served as prizes for the winners of the Panathenaic Games. In the 4th century BCE, cutting down or uprooting one of those trees could be punished with exile and confiscation of property. To this day in Italy, spilling oil on the table is viewed as a bad omen.

The Romans too loved their olive oil, which they consumed in mindboggling amounts. Monte Testaccio in Rome looks like a natural hill, but it’s an immense pile of broken oil amphoras (tall jars), which were used only once to prevent rancidness. During the imperial age, more than 1 million people lived in Rome, each one consuming an average of two litres of oil per month. How was it even possible? They appreciated oil as food, but they used it mainly for other purposes, such as lighting their houses and anointing their bodies. ‘Wine inside and oil outside,’ sums up Pliny the Elder, who considered olive oil ‘an absolute necessity’ of human life.

It’s not difficult to see why. Due to its antiseptic and calming properties, olive oil was used to clean, treat and beautify the body. In ancient medicine, olive oil was ‘the great healer’, and athletes were given deep friction massages with it to cure and prevent injuries. Warriors, too, smeared themselves with olive oil and used it to prevent their swords from rusting, as it’s an excellent solvent and lubricant. Olive oil also belonged to the world of perfumes. Exotic essences were layered in a clarified olive oil medium to obtain fragrances that were more subtle and persistent than those familiar to us, which are carried by alcohol. Pliny lists a dozen uses for olive oil, including smearing one’s face, hair and teeth with it. ‘The whole Mediterranean,’ wrote Lawrence Durrell, ‘seems to rise in the sour pungent taste of these black olives between the teeth. A taste older than meat, older than wine. A taste as old as cold water.’

The History of Olive Oil is the history of a persistent fascination. An all-pervasive presence across the ancient Mediterranean world, it continued to be seen as the purest and most eloquent way to exhibit close relations with the divine in the monotheist traditions of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Its allure survived the impact of modernity. Since the 1950s, olive oil has enjoyed a renewed global reputation as a ‘healthy fat’. It is the cornerstone of the so-called Mediterranean Diet, a food pattern that incorporates practices from Greece and southern Italy, and that advertises itself as a salubrious way of life correlated to high life expectancy and low rates of diet-related chronic diseases. Rich in oleic acid and natural antioxidants, olive oil was marketed to American and north European consumers as a solution to the chronic ailments brought on by industrial methods and additives. The diet became an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2013. To imbibe olive oil is to enter into what the anthropologist Anne Meneley calls the ‘imaginaries of the Mediterranean’ as a site of real food and of slow and authentic forms of sociability, the combination responsible, it has been argued, for the higher number of centenarians in this region.

Nostalgia for traditionally made food and its authentic flavours is obviously not unique to olive oil. Oil producers are, however, extraordinarily successful at mobilising nostalgic narratives. The images of an archaic, mythical Mediterranean pervade the labels for what is now often acronymised to EVOO (extra virgin olive oil). The labels contain recurring terms that gesture toward traditional production methods: olives are ‘stone-crushed’, and oil is ‘cold pressed’ or ‘unfiltered’. These terms, like other commonly used descriptors, are not telling you much about the bottle’s content and the sensory experience you’re likely to have. Unlike well-designed wine labels, olive oil labels are mostly about evocation. Those weirdly shaped bottles in dark green glass evoke Mediterranean living, and promise to guard our kitchens against the relentless industrialisation and commodification of food.

Olive Oil Is One of A Handful of Foods Whose Quality Is Legally Determined By Its Flavour

But there is always trouble in paradise. As denounced in Tom Mueller’s book Extra Virginity (2012), the sublime world of olive oil has a scandalous underbelly. Due to its high price and limited supplies, it is one of the most adulterated and mislabelled foods in the world. Pick a bottle of EVOO in a supermarket, and there is a good chance that it would not be recognised as extra virgin by a professional tasting panel. It might even be a concoction of heavily processed low-grade oils stripped of sensory qualities and health benefits, or it might contain substances that have nothing to do with olive juice. Mueller lamented the sheer vagueness of the term ‘olive oil’, which can refer to several different products, including refined industrial oils. And he introduced the reader to the ‘extra virgin’ denomination, which is a way of gesturing toward the authenticity and purity of the product, and of imposing order in an unruly oil world. The denomination dates back to a 1960 European law that created oil grades to standardise quality control and regulate trade. But what does it mean exactly?

I did not fully grasp it until I decided to up my olive oil game, following an interest in the history of olive oil technology. I received technical training at the National Organisation of Oil Tasters (ONAOO) in Imperia, Italy, an association that pioneered the modern tasting method for olive oil. Unlike other food-processing technologies, modern olive oil machinery has been constantly tested and modified based on the resulting flavour of the product. To this day, the oil is one of a handful of foods whose quality is legally determined by its flavour. Intriguingly, flavour was key even when olive oil was not produced for use, primarily, as food. I figured that there must have been a connection between machinic modernity and the ideal flavour of olive oil, which meant I had to learn how to taste it.

Training At ONAOO consists of acquiring a set of skills codified in tasting protocols, which are then used to sort and grade olive oil. This method enables oil tasters to have a shared language, much like the extravagant terms used by wine tasters to convey their sensations. I learned to look for perceptible fruitiness, quantify its presence and discern subtle fragrances and flavours, captured by terms like ‘artichoke’, ‘fresh-cut grass’ or ‘green tomato’. I also learned that bitterness and pepperiness are desirable. Most of the training, however, focused on identifying far less pleasant attributes, labelled by terms like ‘fly’, ‘frost’, ‘heated’, ‘greasy’, ‘mould’, ‘rancid’ or ‘sludge’. They sound disgusting, which they are, no matter how many apples you bite between one sip and the next. These attributes reveal that a problem occurred during the production process – the olives were compromised by a parasite; or not properly processed; or the oil was poorly preserved; or adulterated. An extra virgin olive oil should have no detectable defects. The oil taster is, above all, a defects seeker.

The International Olive Council (IOC) states that the main requirements for an oil to be classified as extra virgin are an absence of defects in its flavour, a perceptible fruitiness, and certain chemical properties – like a free acidity lower than 0.8 per cent. Pepperiness can indicate that the olives were harvested at the right time, before they were fully ripe, and that they were processed promptly, so that no fermentation occurred. This, in turn, is an indicator that this oil’s acidity is likely to be low. Oil acidity cannot be ascertained by tasting, but one can taste flavours that function as proxies for low acidity.

Extra Virginity Evokes A Preindustrial World Where Families Use Ancient Stones To Grind Locally Picked Olives

The IOC also states that extra virgin olive oil must be extracted from olives through a sequence of strictly mechanical operations, such as grinding and pressing or, more commonly today, centrifugation. No chemicals should ever be used, and the temperature during the process should not rise above 80.6°F (27°C). A higher temperature facilitates extraction but alters the oil’s organoleptic (or sensory) properties. Hence the significance of ‘cold pressed’. Strictly speaking, most extra virgin olive oil today is not ‘pressed’, as it’s not processed through presses, let alone stones – and thus ‘cold extraction’ is often a more appropriate descriptor. References to presses and stones gesture toward traditional methods as guarantors of quality.

The myth of traditional methods, however, is questionable. Marcello Scoccia, a blender and sensory analyst at leading companies for the past 40 years, ran the course I took at ONAOO. Cutting an elegant figure, he thoughtfully handles the tasting cup, and firmly believes in what he describes as scientific rigour applied to oil tasting. ‘If you are looking for consistent quality,’ he noted with a smirk, ‘then cutting-edge continuous-cycle mills are the safest bet.’ Continuous cycle means that olives are processed through centrifuges and steel machinery, within a few hours of harvesting. Stones and family-run mills are good for marketing, he conceded, but they are more difficult to operate, and many things can go wrong. And yet, the connection with traditional machinery and methods, however imaginary, is the main way to communicate ‘quality’ to consumers. Extra virginity evokes a romanticised preindustrial world where families use ancient stones to grind locally picked olives.

But how did we come to believe that what was codified in the notion of extra virginity captures the essence of what olive oil is and always was? The underlying assumption is that oil production has a timeless quality, and is based on practices and technology that have stayed constant for centuries, if not millennia, only to be corrupted by new industrial methods between the 19th and 20th century. It’s another version of the misleading narrative that portrays traditional practices as static, non-creative and destined to be wiped away by modern technological innovation. In Silicon Valley’s lore, disruption and radical innovation are positive values. In the case of oil, and food more generally, it’s come to be the opposite: innovation corrupts venerable traditions and threatens people’s health and identities. But the model of change underlying both narratives is similar. And it’s wrong.

Olive Oil Technology has changed enormously through time, with innumerable regional variations. There was never a fixed set of ‘traditional’ machines, but rather shifts in local needs and Mediterranean trading patterns. Inevitably, flavour changed too. Current talk of traditional olive oil-making refers to a set of machines and procedures captured by a familiar imagery: a mill with one or two round stones, and a central screw press, which squeezes mesh bags filled with olive paste. Described as a legacy of a remote past, this technology is said to produce authentic olive oil, the ideal model for our contemporary extra virgin approximation. But how old were these machines, really?

Engraving of olive oil production, attributed to Jan Collaert, based on Jan van der Straet, circa 1594-98. Courtesy the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

In fact, they date to the second half of the 18th century, when olive oil production began to be consistently mechanised. At that time, these new standardised machines became popular among southern European oil producers. Described as the ‘new’ oil manufacture, they were perceived as modern and efficient, rooted in analytic reasoning rather than irrational tradition. Stones and presses had long been used, but now they were designed according to new specifications and inserted in an entirely new productive process. To their promoters, the new olive mills were the most visible sign that the spirit of Enlightenment had finally reached the shores of the Mediterranean.

The production of olive oil involved a few basic steps: olives were collected, stored, milled and pressed, then the oil was left to clear in special containers. Enlightened reformers and entrepreneurs modified each stage of this process. Stones for crushing the olives became bigger and were cut to maximise pressure. Mules were replaced with horses, oxen or, wherever possible, vertical waterwheels. Beam presses, an ancient and adaptable technology, were replaced by batteries of central screw presses. These were often mounted into structures that dramatically increased their force.

The Greatest Challenge Was Not Building The Mills, But Convincing Local Labourers To Work In Them

But these modern and powerful mills could function only on one condition: increasing the workload of millers and transforming the nature of their labour. A mechanised plant equipped with two mills and a battery of six reinforced presses could process more than one batch of olives at a time, olive paste moving from one press to the next in an ordered sequence of carefully measured pressings. To operate the mill 24 hours a day demanded a precise choreography. The power source gave continuity to the process, allowing labour to be distributed efficiently, and the steps of the process followed each other so as to keep each machine constantly in use: milling, first pressing, second pressing, third pressing, and the washing of the olive remnants. An optimised Apulian mill of the 1780s could process eight full loads of olives in 48 hours. A local entrepreneur warned that ‘nothing is more damaging to a fully equipped oil mill than being at rest.’

The dawn of the Industrial Revolution in the Mediterranean took the form of modern oil mills. The greatest challenge for entrepreneurs was not building the mills, but convincing local labourers to work in them. Previous oil mills were operated by men and women for a few hours a day during winter, when other demands of farm work slackened. They worked under the guidance of an experienced chief miller, sometimes called a helmsman, who ruled the mill with an authority similar to that of ship captains. Entrepreneurs stripped chief millers of autonomy and implemented the new – mechanised and analytically ordered – productive process. Temporary workers were replaced by brigades of men who worked in shifts around the clock.

Resistance to this new discipline is well documented. Many entrepreneurs hired foreigners, provoking tensions and riots. After many failed experiments, French and Italian entrepreneurs had to give up establishing mechanised mills in certain regions of southern Europe, such as Corsica or Calabria. The trope of the ignorant and recalcitrant Mediterranean peasant-worker was used to explain these failures. In reality, the revolts signalled a crisis in the nascent post-feudal order. By the end of the 18th century, peasant insurrections would target the ‘new men’, the entrepreneurs who supported the philosophical principles of the Enlightenment, the political ideals of the French Revolution, and the analytic management of mechanised production.

Objections To The New Mills went beyond riotous labourers. Some landowners and traders too were sceptical of the new machinery. Why? Weren’t new machines simply better than older ones? Well, it depends. Reformers argued for more powerful machines and for speeding up production. But these goals made sense only to those who were ready to exploit the rising international demand for oil and willing to transform the nature of olive oil to do so.

Most oil mills didn’t need much power because the olives they processed were ripe and already fermented, and thus easy to crush. The oil produced in this way had high acidity, which meant that it could be used for local consumption. It turned rancid fairly quickly, however, and didn’t travel well. By the mid-18th century, it was not suitable for meeting the rising demand for oil from northern Europe and colonial networks. Low acidity oil, by contrast, could preserve its properties when shipped over long distances. Fine low-acidity oils had been manufactured in small quantities since antiquity, mainly for medical and cosmetic purposes. The new trading opportunities turned this kind of oil into a highly profitable business for those Mediterranean elites who could invest in it. But, in order to do so, they needed to change what olive oil was, how it was made – and how it tasted.

To keep acidity low, olives had to be picked directly from the tree, before they were fully ripe. This meant that crushing them was harder: hence more power was needed. Habits and beliefs about storing and fermenting olives had to be swept away, together with entrenched expectations about the colour and flavour of good edible oil. The new oil was sweeter and clearer, with a distinctive peppery note, remarkably different from the pungent and dark oil consumed across the Mediterranean. Not everyone thought it tasted better. The popular classes continued to prefer the ‘common oil’ and, to the apparent surprise of enlightened physicians, they continued to have no trouble digesting it. Southern elites, by contrast, developed a taste for the light and delicate flavour of the new oil. They were, in any case, the only groups who could afford it and, where the new oil became established, everyone else had to consume its cheaper byproducts.

The Delicate And Peppery Flavour of The New Oil Denoted New Forms of Subordination

Admittedly, international demand for olive oil was not yet driven by its value as food. Before 1800, no other known material could outperform olive oil as a fuel for illumination or a lubricant for industrial machinery. But common oil would not do, as it would get rancid too easily. A rancid oil would be smelly and smoky when burned, and it would decompose quickly when used as a lubricant. In the second half of the 18th century, the price of low-acidity oil was published regularly in London, and it could be twice the price of common oil. On a clear day, in the bay of the oil town of Gallipoli in southern Italy, one would count around 70 foreign vessels at anchor, most of them British and Dutch, queuing to be loaded with oil. A British vice-consul resided in town for the sole purpose of fostering the oil trade. It was in this context that the appearance and flavour of low-acidity oil became proxies for its market value as an industrial oil.

Modern oil-making not only brought the Enlightenment to the Mediterranean world, but also new capitalist forms of production. Up to that point, oil making had followed the logic of mixed property and communal rights. Modern oil-making, by contrast, could succeed only where entrepreneurs controlled the entire cycle of production, from harvesting to storage. That is to say, where capitalism reigned uncontested. One key challenge for entrepreneurs was how to discipline the Mediterranean peasant-worker. The delicate and peppery flavour of the new oil didn’t just denote new organoleptic properties but the establishment of new forms of subordination.

Then as now, mechanisation and automation are not neutral. They never are. They do not just speed up older ways of doing things. Historically, they always mark transformations that are social as well as technical. In the case of 18th-century oil technology, what was transformed was not only the machinery but the nature of the product – and of the social world and economic power structures organised around it. New mills and the new oil were not self-evident goals, nor were they determined by an ineluctable technological trajectory. Rather, they were the contested outcomes of a reorganised social life that dictated, among other things, who should benefit from oil production, and how.

Oil Tasting Is A Sombre Task. Tasters handle the tulip-shaped glass as if the oil were brandy, warming it with their palm. They look at the colour of the oil, then smell it to discern its fragrances. Then they take a large sip, and start sucking in air from the corners of their mouth. In this way, they coat their tongue with oil while channelling the aromas up into the nose, so that no flavours will be missed. The loud slurping noise is followed by a quieter sipping and note-taking. Tasting one oil can take up to 15 minutes. What are they looking for?

Behind the colourful descriptors designed to capture each subtle note are the qualities valued by enlightened oil entrepreneurs: flavours that were proxies for low acidity. These indicated that an oil was ready for global trade, and that it would fetch a high price on international markets. They communicated to the connoisseur that the oil was suitable as a long-lasting lubricant or lamp fuel. And also suitable for the refined palates of the affluent Mediterranean bourgeoisie – or, as a Portuguese writer put it – for the ‘delicate tables’. As such, the new flavours mocked the popular taste for common oil, which was now regarded as vulgar and unhealthy. Three centuries after that Mediterranean encounter with industrial capitalism, we are still tasting olive oil to discern whether it’s good for a machine.

Next time you dip a piece of bread into a good olive oil, savour it for a moment, and seek that peppery flavour on the back of your tongue. It’s a flavour that conveys the presence of healthy polyphenols, and that pepperiness is a celebrated protagonist of the Mediterranean lifestyle. Today, it signifies authenticity and a connection to ancient traditions. But that very pepperiness tastes much like the advent of industrial capitalism and the creation of modern power relations in the Mediterranean world. It tastes like the growing network of global shipping routes, and the increasing rotational speed of well-lubricated industrial machinery. It’s a flavour that announced the dawn of a new world, the flavour of mechanisation.

#AEON.Co#Food 🍱 | Drink 🍺#History of Technology#Process and Modernity#Olive 🫒 Oil#Flavour | Mechanisation#Revered#Cherished#Distinctive Peppery#Taste#Modern Invention#Massimo Mazzotti

0 notes

Text

The Most Scenic Marathons in the World

Running a marathon is a feat of endurance, discipline, and determination. While the physical and mental challenges are immense, the backdrop against which these races are set can transform the grueling experience into an unforgettable journey. Here, we explore some of the most scenic marathons around the world that offer breathtaking views and unique cultural experiences, making the long miles a bit more enjoyable.

1. Big Sur International Marathon, USA

Located along the stunning California coastline, the Big Sur International Marathon is often hailed as one of the most beautiful Most Scenic Marathons in the World. Runners start in Big Sur and make their way north to Carmel, with the Pacific Ocean as their constant companion. The route takes participants across the iconic Bixby Creek Bridge and through redwood forests, offering panoramic views of the rugged coastline and verdant landscapes. The combination of the cool ocean breeze and the natural beauty makes this marathon a bucket-list event for many runners.

2. Great Wall Marathon, China

For those seeking a marathon experience that blends history with scenic beauty, the Great Wall Marathon in China is unparalleled. The race takes place on the Huangyaguan section of the Great Wall, offering runners the chance to traverse one of the world's most famous landmarks. The course is challenging, with steep ascents, descents, and thousands of stone steps, but the sweeping views of the surrounding mountains and valleys make every effort worthwhile. Participants are rewarded with a profound sense of accomplishment and a deep connection to China's rich cultural heritage.

3. Athens Marathon, Greece

Known as the Authentic Marathon, the Athens Marathon traces the original route run by the messenger Pheidippides from the town of Marathon to Athens. This race is not only historically significant but also incredibly scenic. Runners pass through the Greek countryside, dotted with olive groves and ancient ruins, before finishing in the Panathenaic Stadium, the site of the first modern Olympic Games. The combination of historical landmarks and natural beauty provides a unique and inspiring marathon experience.

4. New York City Marathon, USA

While urban, the New York City Marathon offers its own unique scenic appeal. The race winds through all five boroughs of the city, providing runners with a diverse array of sights and sounds. From the verdant expanses of Central Park to the iconic skyline views from the Queensboro Bridge, the marathon encapsulates the vibrant spirit of New York. The enthusiastic crowds and the chance to run through some of the city's most famous landmarks make this marathon an exhilarating experience.

5. Two Oceans Marathon, South Africa

Dubbed the "world's most beautiful marathon," the Two Oceans Marathon in Cape Town, South Africa, lives up to its name. The 56-kilometer ultramarathon route (there is also a half-marathon option) takes runners along both the Indian and Atlantic Oceans, offering spectacular coastal views. The course includes a run through the scenic Chapman’s Peak Drive, known for its dramatic cliffs and ocean vistas, as well as the lush Constantia wine region. The breathtaking scenery, coupled with the challenge of the ultramarathon, makes this a must-run event.

6. Queenstown Marathon, New Zealand

Set against the backdrop of New Zealand’s stunning South Island, the Queenstown Marathon offers some of the most picturesque landscapes imaginable. The course winds through alpine vistas, alongside pristine lakes, and through vibrant autumnal forests. Runners are treated to views of Lake Wakatipu, the Remarkables mountain range, and the serene beauty of the Gibbston Valley. This marathon combines the thrill of running with the opportunity to experience New Zealand's renowned natural beauty.

7. Polar Circle Marathon, Greenland

For the adventurous runner, the Polar Circle Marathon offers a unique and extreme scenic experience. Held in Kangerlussuaq, Greenland, this marathon takes place on the edge of the Arctic Circle. Participants run on icy, snow-covered terrain, with the surreal, otherworldly landscapes of the polar ice cap and arctic tundra as their backdrop. The stark beauty of the frozen wilderness and the challenge of running in such a harsh environment make this marathon a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

0 notes

Text

May 21st

We began our fifth day in Greece by packing up the bus and starting our journey to our next destination. One stop was made before we left Athens at a monumental, unique site: the Panathenaic Stadium. Greek and Olympic flags waved in the wind, greeting us to the stadium. A self-guided audio tour taught us about the rich history of the stadium. It was impressive being in the only stadium in the world to be entirely composed of marble. Some fascinating facts about the Panathenaic Stadium were that it hosted the first modern Olympic Games in 1896, it has two marble thrones in the stands, it can fit around 70,000 spectators, and the decline of the use of the stadium began with the rise in Christianity. Not only is the stadium an impressive view in itself, but from the upper section of the stands, views of the city of Athens and the Acropolis can be seen. Halfway through the tour of the stadium, a tunnel leading underneath the stands led to a room with Olympics memorabilia of posters and torches. Our tour of the Panathenaic stadium was the perfect way to end our time in Athens before spending the rest of our day in Ancient Nemea and then Nafplion.

- Madeline C.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Panathenaic Stadium Passage in Athens, Greece Hidden beneath the Panathenaic Stadium, the world's only stadium built entirely out of marble, is a secret, ancient passage used by ancient gladiators and modern athletes. The passageway, known as the diodos, is a long, vaulted gallery that dates back to antiquity. The Panathenaic Stadium has gone through many iterations through the centuries. Greek statesman Lykourgos first built a simple, limestone racecourse on the site in 330 BC for the first Panathenaic Games, a festival featuring athletic competitions, rituals, and religious ceremonies held in ancient Athens. The Games were held every four years in honor of the Greek goddess Athena. Several centuries later, around 140, Athenian Roman senator Herodes Atticus had the racecourse rebuilt in marble and expanded it to fit 50,000 spectators. Soon after that, by the fall of the Roman Empire in 476, the stadium fell into disuse until the 19th century. Beginning in the 1830s, following Greek independence, archaeological excavations began on the stadium. German-born architect Ernst Ziller carried out later excavations around 1870. The stadium was refurbished and used in the Zappas Olympics in 1870 and 1875, an early attempt to revive the Olympic Games. Then, in 1896, the stadium hosted the first modern Olympics. The subterranean passageway is located on the east side of the ancient stadium. Even before Lykourgos built the first limestone racecourse, ancient masons constructed this passageway leading to the ravine where the stadium would later be built. Known as the "Hole of Fate," ancient oracles used the passage. Spiritual leaders also walked through the passage before holding ritual animal sacrifices in the ravine. In Roman times, gladiators passed through the tunnel before fighting in the marble-clad stadium. After the stadium fell into disuse, European travelers wrote about young Athenian maidens performing magical rites in the derelict passage. Today the tunnel leads to a museum featuring torches and posters from all the modern Olympic Games. Every two years, for the winter and summer Olympic Games, the Olympic torch is lit in Olympia, Greece before making its way to the Panathenaic Stadium for the official handover ceremony where the torch is passed to the official hosting city. Besides the passage, the impressive oval stadium has several interesting details, including curved seating and carved thrones. Here visitors can walk the stands and run the track where the first modern Olympics occurred. https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/panathenaic-stadium-passage

0 notes

Text

“The marathon's ancient origins

By Judith Swaddling, Senior Curator, Greece and Rome

Publication date: 11 September 2017

Senior Curator Judith Swaddling uncovers the ancient Greek origins of the long-distance endurance race, revealing the original 'marathon runner'.

Although never part of the ancient Olympic Games, the marathon does have ancient Greek origins. According to the Greek historian Herodotus(Opens in new window), when the Athenians learned that the Persians had landed at Marathon on the way to attack Athens in 490 BC, a messenger named Pheidippides ran to Sparta with a request for help. This original ‘marathon runner’ covered 260 kilometres of rugged terrain in less than two days! The Persians were subsequently defeated at the Battle of Marathon. The word marathon is the Greek word for fennel, which seems to have grown in the area and gave the battlefield its name.

A dagger found at Marathon. Greece, 5th century BC

Running was a key part of the ancient Olympics, although long distance races were not initially included. The stadion (or 'stade') race, a short sprint, was the most ancient – and indeed the only – event at the first 13 Olympiads. This is where we get the modern word 'stadium' and its winner had the Olympiad named after him. The track was not circular but straight, and measured approximately 192 metres.

The vigorous action of a sprinter. Amphora made in ancient Greece, c. 550–525 BC.

Gradually other footraces were added to the programme at Olympia. The diaulos, named after the musical double pipes, consisted of two lengths of the stadium, while the dolichos was a long-distance race, consisting of 20 or 24 lengths. The greatest Olympic runner of all was Leonidas of Rhodes, who won all three events at each of the four Olympiads between 164 and 152 BC. For a runner to maintain such a peak of fitness (all the running events were held on the same day) for 12 years was a remarkable feat and such was the pride of his countrymen that he became worshipped as a local deity.

The steady rhythm of three long-distance runners. Panathenaic amphora made in 333 BC.

The marathon as we know it today was not an event until the modern Olympic Games in 1896, and even then it varied in length. The first modern Olympic marathons were around 40km (25 miles), which is approximately the distance between Marathon and Athens. The marathon is the final athletic race in the Olympics, usually finishing in the stadium. The now standard length of 26 miles and 385 yards was originally run in the 1908 Games in London.

Bronze figure of a running girl. 520–500 BC

Women were excluded from competing in the Olympic Games, but they did have a festival of their own at Olympia. This was the Heraia, or games held in honour of Hera. These were also celebrated every four years, but there was only one type of event – the foot-race. It was divided into three separate contests for girls of different age groups. The winners were given crowns of olive like the Olympic victors, and they also received a portion of a heifer sacrificed to Hera. Just as the Olympic prize-winners were allowed to dedicate statues of themselves, so the girl victors were granted the privilege of setting up their images in the temple of Hera, but these were paintings and not statues. At Sparta, girls seem always to have undertaken the same athletic exercises as boys, because tough, strong mothers were believed to produce good Spartan soldiers. The bronze statuette of a girl runner above is probably from Sparta, where women were also expected to take part in athletics. Her appearance corresponds well with the ancient Greek geographer and writer Pausanias' description of the girls who raced in the Heraia: 'Their hair hangs down, a tunic reaches to a little above the knee, and they bare the right shoulder as far as the breast.' (Description of Greece V 16.4).

Find out more about the ancient Olympic Games with Judith's book The Ancient Olympic Games(Opens in new window), available in the Museum's shop.

https://www.britishmuseum.org/blog/marathons-ancient-origins

1 note

·

View note

Text

In Greek mythology, King Erichthonius (/ərɪkˈθoʊniəs/; Ancient Greek: Ἐριχθόνιος, romanized: Erikhthónios) was a legendary early ruler of ancient Athens. According to some myths, he was autochthonous (born of the soil, or Earth) and adopted or raised by the goddess Athena. Early Greek texts do not distinguish between him and Erechtheus,[1] his grandson, but by the fourth century BC, during Classical times, they are distinct figures.

Birth of Erichthonius: Athena receives the baby Erichthonius from the hands of the earth mother Gaia, Attic red-figure stamnos, 470–460 BC, Staatliche Antikensammlungen (Inv. 2413)

Etymology

Erichthonius of uncertain etymology is possibly related to a pre-Greek form *Erektyeu-. The connection of Ἐριχθόνιος with ἐρέχθω, "shake" is a late folk-etymology; other folk-etymologies include ἔριον, erion, "wool" or eris, "strife"+ χθών chthôn or chthonos, "earth".[a][3]

MythologyEdit

BirthEdit

Athena Scorning the Advances of Hephaestus, Paris Bordone, between c. 1555~1560

According to the Bibliotheca, Athena visited the smith-god Hephaestus to request some weapons, but Hephaestus was so overcome by desire that he tried to seduce her in his workshop. Determined to maintain her virginity, Athena fled, pursued by Hephaestus. He caught Athena and tried to rape her, but she fought him off. During the struggle, his semen fell on her thigh, and Athena, in disgust, wiped it away with a scrap of wool (ἔριον, erion) and flung it to the earth (χθών, chthôn). As she fled, Erichthonius was born from the semen that fell to the earth. Athena, wishing to raise the child in secret, placed him in a small box and then made sure no one would ever find out by giving him away.[4]

Athena gave the box to the three daughters (Herse, Aglaurus and Pandrosus) of Cecrops, the king of Athens, and warned them never to look inside. Pandrosus obeyed, but Herse and Aglaurus were overcome with curiosity and opened the box, which contained the infant and future-king, Erichthonius ("troubles born from the earth," following another etymology). (Sources are unclear regarding how many sisters participated.) The sisters were terrified by what they saw in the box: Either a snake coiled around an infant, or an infant that was half-human and half-serpent. They went insane and threw themselves off the Acropolis. Other accounts state that they were killed by the snake.

An alternative version of the story is that Athena left the box with the daughters of Cecrops while she went to fetch a limestone mountain from the Pallene peninsula to use in the Acropolis. While she was away, Aglaurus and Herse opened the box. A crow saw them open the box, and flew away to tell Athena, who fell into a rage and dropped the mountain she was carrying (now Mt. Lykabettos). As in the first version, Herse and Aglaurus went insane and threw themselves to their deaths off a cliff.

ReignEdit

When he grew up, Erichthonius drove out Amphictyon, who had usurped the throne from Cranaus twelve years earlier, and became king of Athens. He married Praxithea, a naiad, with whom he had a son, Pandion I. During this time, Athena frequently protected him. He founded the Panathenaic Festival in the honor of Athena, and set up a wooden statue of her on the Acropolis. According to the Parian Chronicle, he taught his people to yoke horses and use them to pull chariots, to smelt silver, and to till the earth with a plough.

It was said that Erichthonius was lame of his feet and that he consequently invented the quadriga, or four-horse chariot, to get around more easily. He is said to have competed often as a chariot driver in games. Zeus was said to have been so impressed with his skill that he raised him to the heavens to become the constellation of the Charioteer (Auriga) after his death.

The snake is his symbol, and he is represented in the statue of Athena in the Parthenon as the snake hidden behind her shield. The most sacred building on the Acropolis of Athens, the Erechtheum, is dedicated to Erichthonius.

Erichthonius was succeeded by his son Pandion I.

Regnal titles

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Panathenaic Prize Amphora: A Pot With Olive Oil Awarded at The Ancient Greek Olympics

Instead of a gold medal, victors at the ancient Greek Panathenaic Games received terra-cotta pots filled with Athenian olive oil from sacred trees.

Name: Panathenaic prize amphora.

What it is: A Greek terra-cotta pot known as an amphora.

Where it is from: Vulci, Italy.

When it was made: Circa 530 B.C., during Greece's Archaic period.

Unlike in today's Olympics — in which competitors receive gold, silver and bronze medals — each ancient winner received dozens of terra-cotta vases emblazoned with their specific sport and filled with Athenian olive oil, a highly "valuable prize," according to Harvard Art Museums.

The olive oil award given to Olympic champions came from the sacred groves of Athena, the patroness of Athens, according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. In general, ancient Greeks considered olive trees "sacred," and they symbolized Zeus, the god of the sky and, later, the god of the Olympics, according to the Journal of Olympic History.

his particular amphora features a lineup of five runners during a footrace, a competition considered the "earliest known event in the Panathenaic Games," according to the Met. Athletes competed fully naked, since they thought their physiques might intimidate their competition, according to Southern Utah University.

The pot, which stands 24.5 inches (62 centimeters) tall, is attributed to "Euphiletos Painter." This anonymous artist was known for an art style called black-figure pottery, in which subjects were drawn in silhouette, according to the British Museum. This is just one of the many vases awarded to the victors at the Games, with other pots featuring charioteers, archers and boxers.

By Jennifer Nalewicki.

#Panathenaic Prize Amphora: A Pot With Olive Oil Awarded at The Ancient Greek Olympics#olympics#ancient greek olympics#amphora#terra-cotta#terra-cotta pot#athenian olive oil#sacred olive oil#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient greece#greek history#greek art#ancient art

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Panathenaic Stadium in Athens: home to the first modern Olympic Games in 1896 and the only stadium in the world built entirely out of marble.

Here are ten facts about the stadium you probably don't know:

1. The stadium is built in what was originally a natural ravine between two hills.

2. The word 'stadium' comes from the Ancient Greek measure of length. A 'station' is approximately 185 metres, the equivalent of a track's length. However, the track at the Panathenaic Stadium is not the usual shape. It has a 204m straight with very sharp turns.

3. Until the 1950s, the Ilissos River (which is now covered by and flowing underneath) ran in front of the stadium's entrance.

4. Records dated 329 BC show that Eudemus of Plataea gave 1000 yoke of oxen towards constructing the first stadium made of wood.

5. Construction of the new stadium began around 139 AD and finished in 144 AD. It is made entirely of Pentelic marble: the same as the Parthenon is built from.

6. It could hold 50,000 spectators.

7. In the late 4th century, the stadium was abandoned and fell into ruin. Gradually, its significance was forgotten, and a field of wheat covered the site.

8. Then, in 1836 following Greece's independence, archaeological excavation uncovered traces of the stadium.

9. The Zappas Olympics, an early attempt to revive the ancient Olympic Games, were held at the stadium in 1870 and 1875.

10. On the 6th of April 1896, it was the location for the very first modern Olympic Games.

#goexploregreece#greece#travel#mustsee#mustvisit#greek#europe#beautiful views#athens#stadium#arena#athens city#traveling#beautiful photos#travel photography

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 10 not-to-miss Archaeological Sites in Greece

In the aftermath of the fire that passed right through the archaeological site of Mycenae (fortunately the site wasn’t irreparably destroyed, it was mostly smoked) here are 10 of the most important / standard archaeological sites to see in Greece. These aren’t even a tenth of the sites Greece has to offer, neither are recently discovered important sites that have yet to open to the public included in this list, but this is the list of the places to get started from, either because they are very informative or because they typically attract the majority of tourists.

1. Acropolis, Athens

The standard first stop of every tourist arriving in Greece and yet, Greeks frequently fall into two categories; those who see it every day and those who have yet to visit it. On the Acropolis (which means Edge of the City) one can see the Propylaea (the monumental gateway), the Temple of Nike, the Erechtheion with the Caryatids, which is a temple dedicated to both Athena and Poseidon and, lastly, the Parthenon which is the most important landmark of Greece. Parthenon was the temple dedicated to Athena, the patron Goddess of Athens. A walk to the Acropolis should be ideally combined with a visit to the New Acropolis Museum nearby.

2. Delphi, Phocis

The archaeological site of Delphi is located at Phocis, nestled in Mount Parnassus. It is a shrine dedicated mostly to Apollo and this was also where the most famous oracle of antiquity functioned. Nowadays, the visitor can see the ruins of Apollo’s Temple, treasuries from various cities, the most important one being that of Athens, the ancient theater, the ancient gymnasium, the Castalian spring and the Tholos of Athena Pronaia. The exploration is not complete without a visit to the Museum of Delphi.

3. Ancient Olympia, Elis

This is where the Olympic Games were founded and took place. Nowadays, it is still the location where the Olympic Flame is lit every four years. Afterwards, the Olympic Flame travels from Olympia around Greece, then it arrives to the Panathenaic Stadium in Athens and from there it travels to the previous and then the next host city of the Olympic Games. Visitors there can see the ruins of the temple of Zeus, the temple of Hera, the Stadium, the Palaestra (the wrestling school) and much more. The beautiful statues have been removed from the site and are exhibited in the Museum of Olympia. There you can also see the famous Nike of Paionios and Hermes of Praxiteles.

4. Knossos, Heraklion

Knossos was the capital of the Minoan civilization (3000 - 1400 BC) in Crete. The palace of Knossos is associated with numerous Greek myths, such as those of Theseus and the Minotaur and Daedalus and Icarus. The site is notable for its exquisite frescoes that are both beautiful and very informative about the era. The throne hall and the storage rooms are impressive, especially if you consider that this is the first throne room of Europe.

5. Mycenae, Argolis

Let’s go to the smoked impressive sweetie.The Mycenean civilization flourished right after the Minoan and its base was Mycenae, in mainland Greece. Its most notable king was Agamemnon, who made his way into the Homeric epics and the Greek mythology. At Mycenae visitors can see the Lion Gate, the impressive royal tholos tombs, the king’s halls and much more.

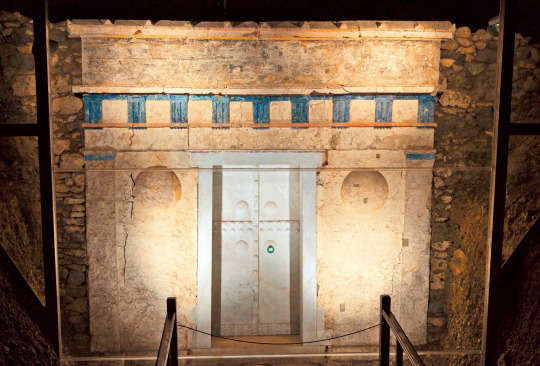

6. Vergina, Imathia

While Alexander the Great’s tomb remains a world mystery, his father’s King Philip fortunately is not (99% at least). In Vergina visitors can see the unplundered royal tombs and the palace as well as the artifacts of great importance found in them.

7. Temple of Poseidon, Cape Sounion

The temple of Poseidon attracts many thousands of visitors annually. Built on the edge of the cliff above the sea, it creates idyllic conditions for photographs, especially at night with full moon.

8. Messini, Messenia

Messini in Peloponnese is one of the best preserved ancient cities in Greece. One can clearly see the gymnasium, the theater, the stadium, one of the two city gates, the fountain of Arsinoe and many more structures / buildings. Just next to the site is the archaeological museum with all the findings that complete the visitor’s impression of the place.

9. Lindos, Rhodes island

On a hill next to the sea in the south of Rhodes you can visit the Acropolis of Ancient Lindos and the temple of Lindia Athena. Much later in time, a medieval fortress was built around the ancient acropolis, making the site even prettier.

10. Epidaurus, Argolis

The most famous theater of antiquity and one of the best preserved. It’s worth a visit not just for the archaeological site itself, but also for its wondrous acoustics. Besides, the theater still operates and certain theatrical plays take place there, where you can attend and feel like you belong to an ancient audience.

#greece#europe#ancient greece#athens#acropolis#sounion#attica#delphi#central greece#epidaurus#messini#ancient olympia#mycenae#peloponnese#crete#knossos#lindos#dodecanese#macedonia#greek culture

293 notes

·

View notes

Text

Plato-nic Love (Part I)

I sadly didn’t finish the whole story in time but this is part one of Seren and Plato’s epic love story for the ages XD

Illustrations were done by the wonderful @sigeel 😍😍😍

So this submission is by the two of us!

Plato-nic Love

Seren poured a libation of wine and started working on the grapevine that had been growing in the family garden for a while. At first, her mother had tried to get rid of it but it had proven the essence of indestructable life and so they had accepted its presence much like Seren had come to accept the presence of its patron god. She was about to cut off a branch to use for making a crown later on when she heard a familiar voice. "How is my favourite bacchae?" She sighed. It had been about a year since she had agreed to become his faithful follower and needless to say she was still the only one. "Do you know what day it is?" Seren started frantically going through all the calendars she had studied, from the reconstructed Attic calendar to the Roman calendar before and after the Julian reform -what moon phase were they in again? "You always think we don't care about these things but I have a sursprise for you." Dionysos flashed her a bright smile. "What?" she said flatly. A surprise from a god couldn't possibly mean anything good.

"I SAID: I have a SURPRISE for you!" Confetti and flower petals started raining down on them and from above sounded a rustic melody played on pan pipes. Seren looked up to see Hermes sitting on a treebranch, grinning as he played the instrument his son invented. "Ha ha, very funny, Hermes." Dionysos took Seren by the shoulders. "He was supposed to play the Time Warp. Because it's exactly ONE YEAR TODAY that you became my bacchae and do I have a surprise for you!" "Yeah, you said so. But maybe it would be better if-" "Nonsense! As your patron god I am exceedingly generous. You see, I have noticed your infatuation with Plato." "You don't say." "Yes. Anyway, Hermes was so nice to pay grandfather Kronos a visit and relieve him of a little artef- well, details, it doesn't matter! What is important is that you will get to meet Plato!" "Really?!" There was a nagging voice in Seren's head that told her to be careful but Dionysos had just told her she'd get to meet Plato! "Really. All you have to do is take my hand. But I have another gift for you. Hermes, come down here!" The messenger god swung himself lazily from the tree and floated down until his winged sandals touched the ground. "My brother pointed out that you might have difficulties speaking ancient Greek fluently so he will grant you the ability to speak it like a native for as long as you give up your native English." Seren gaped. "That... is surprisingly thoughtful of you." "Hermes, do it! And no nonsense like giving her a lisp or a foreign accent!" "Of course not. Why would I do that?" Hermes grinned at Seren. "I'd not even be there to see it." "What? Now? Wait!" Seren cried out as divine magic rearranged the synapses in her speech centre. "I did not agree-" "She'll speak fluently once you arrive in Greece," Hermes said, "Once you return, the magic wears off." Dionysos gave his brother a suspicious look. Then he beamed. "Perfect!" Dionysos clapped enthusiastically. "Hold on tight!" He pulled her into his embrace and Seren instinctively hugged him. The world around them began to blur and the heavens seemed to turn back as they sped through time and space. There was a sudden jolt and the world was clear once again. Only, it looked strange. But not strange enough for Seren not to recognise her patron god had spoken the truth. This was ancient Athens! She felt a nasty queasiness but she was much too excited to care about that just now. She had known about polychromy but the sheer explosion of colours in the city made her heart sing. The reconstructions were mere shadows of the vibrant paint on the statues, buildings, and clothes. And the Akropolis! It looked majestic even now but the ruins were nothing compared to the magnificence of colour and architecture. Seren stood in awe, even though they were miles away down in a sidestreet. Potters had laid out their painted vases and other works as they created new ones. Seren couldn't decide what to see first, jumping this way and that until the unsavoury sound of regurgitation briefly diverted her attention. Dionysos leaned against the mudbrick wall of a house and puked his guts out. "How can you be so chipper?" Dionysos groaned, wiping his mouth. "You're mortal!" We travelled both time AND space. You should be barfing like a youth at his first symposion." But Seren just ignored him in her euphoria. "It's Athens!" she cried. "ANCIENT Athens!" "That fleet-foorted son of a-" "What? What is it?!" "Nothing, nothing. Everything is fine. I just..." Dionysos leaned against the mudbrick house. "Hermes could have said something about the inconvenience of travelling." Seren shrugged. Who cared, they were already there. "I want to see EVERYTHING!!! The sculptures! The pottery! The architecture! The clothes..." "Speaking of which..." Dionysos grinned. "We should get you something less 2020. If you want to meet Plato, we need a certain disguise. And you want to look your best for him, right?" Seren screwed up her face. "Plato isn't about looks. He's about the beauty of the soul." "Well, if you want to go dressed in that tasteless pink sweater and leggings combination. But let me tell you, nothing looks better on a woman than a finely woven chiton." "Yeah, you're not at all biased." "It's one of the few things even Apollo and I agree on, so it must be true." Seren would have been happy just roaming the streets of ancient Athens for a couple of days. Or for however long this time thingy would allow. The prospect of meeting Plato both exhilarated and terrified her.

Dionysos bought her an elegant chiton in the extremely crowded agora. Seren hardly suppressed a squeal when he paid with real ancient drachmae. Only they didn't look ancient at all. "Why is nobody staring?" she asked, as another group of people walked past them without paying them any mind. "Did you put glamour over my modern clothes?" Dionysos laughed. "No need, honeybee. This is Athens. At a time like this they get tourists from all over the world. One strange, foreign costume is not going to turn any heads." He pulled her away from the merchants and splendour of the agora into the entrance of a seemingly abandoned house. "Put it on," he said, handing her the chiton. "Don't peek!" she reminded him before she changed into her new garment. It felt cool and pleasant on her skin and the quality of the linen was indeed fantastic. Despite the loose fit the fabric was so delicate it hugged her figure in an almost revealing way, making her feel exposed. "Is this really acceptable dress?" she asked. "Only with this worn over it." Dionysos came up behind her, closing another layer of cloth over her shoulders with simple dress pins. "You look great, honeybee," he said sincerely. "Plato can consider himself lucky. You got the brains, you got the looks, and even that austere, joyless personality to match." "I get the impression you don't like Plato much." Dionysos slung the belt around her waist and fastened it. "What gave it away? My graffiti, my groaning everytime you bring him up, or the charming way I speak about him?" "The graffiti was a pretty obvious hint." "I hope you appreciate my gift all the more, honeybee." "I do." She smiled. "But I don't think I could appreciate it any more than I already do. This is a dream come true. The most exciting day of my life. More exciting even than Delphi." "Be careful not to tell Apollo," Dionysos warned but he looked pleased. "Sure. If I ever run into him I'll remember it." As they stepped outside, the streets were empty. "Where is everybody?" "Oh, it must be time to crown the victors." "Victors? Of what? It's too cold to be July, isn't it?" "Not the Panathenaic Games." Dionysos smiled broadly. "It's not an athletic contest. Today..." He made a dramatic pause. "Is the last day of the Great Dionysia!" "Oh." Seren was disappointed. "So we can't go and watch any of the plays?" "I'm afraid it is too late for that. But I can show you my theatre and the temple with my cult image if you want."

Seren politely admired the simple wooden log that was supposed to be a representation of Dionysos and genuinely marvelled at the masks that had been dedicated below it. She patiently listened to Dionysos as he recounted the story of the very first Dionysia in Athens and how he used to mingle among the crowd every year to watch what the people of Athens had put on the stage in his honour. Once they arrived at the theatre it was already empty but it was a stunning sight all the same. Seeing everything intact and in its full glory filled Seren with unknown joy. The decorations, both permanent and temporary, were as colourful and flamboyant as the god they honoured. When they made it back to the streets of Athens, there were already groups of shouty drunk people roaming about. "Victory parties," Dionysos explained when he saw Seren's face. "In fact, we are about to attend one too. But first..." A purple mist shrouded the god's body and when it dispelled, his simple chiton had given way to a slutty ankle-length skirt that hung low enough to expose part of his bum cheeks, his arms, wrists, and ankles adorned with golden jewellery. "I know you practiced with the aulos. You're gonna be a flute girl." Seren startled. "What? No! I'm not nearly good enough!" Dionysos shrugged, making his golden bracelets clink. "I don't think I need to tell you that other kinds of women are not allowed at symposia. Unless you want to play the role of a hetaira..." "F-Flute girl is fine."

They arrived at a house that obviously belonged to someone well-to-do. "A group of revellers is about to show up here any minute. We'll join them to enter the symposion. Trust me, they're too drunk to realise we don't belong." Seren nodded nervously. "Now would be the time to ditch that respectable dress." Reluctantly, Seren freed herself of the protective extra layer of clothing and received the aulos flutes Dionysos handed her. The revellers did indeed show up. Loud and obnoxious, it was impossible not to notice them. A man in his late 20s or early 30s led the group. Half-naked and well into his cups, crowned with a wreath of ivy and violets, he was all but carried by two sturdy lads who looked like they were half-naked professionally. "Come!" Dionysos tugged on her arm and they danced along, she awkwardly, he with a grace and confidence she envied. The leader of the group pounded against the door and yelled for "Agathon". Seren's heart skipped a beat. "Is that... Alkibiades?!" she whispered to Dionysos. "The very same." "We are at THAT Symposium?!!" "We most certainly are." Seren gaped at the man who would eventually be the ruin of Athens by defecting to Sparta and then to Persia. He rattled the door, shouting "Agathon!" and dropped his single piece of clothing in the process, quickly picked up by his lads. Seren shrieked when the man suddenly leaned heavily on her, his arms reeling for support. Dionysos was quick to jump to his other side, taking most of the load off his bacchae. "AGATHON!" Alkibiades yelled once more, in the manner drunks yelled on their way home from the pub after closing hours. He kept demanding to see Agathon with a heavy tongue until a servant boy finally opened up and led them to the andron. Alkibiades managed to stand on his own, stumbling towards the host of the party while announcing how completely and utterly wasted he was. "Let's bring the bacchic spirit to this lame party!" Dionysos cheered. Seren gazed around with stars in her eyes. The room was bright with torches and the klinai were populated by men both young and old but all shirtless and all with crowns of ivy on their heads. She looked more closely at the guests while Alkibiades spoke to Agathon, probably congratulating him for his victory. But none of the symposiasts looked like any of the artworks she had seen of Plato. They were most likely created after his death anyway. "Soooo..." She leaned on Dionysos' shoulder. "Where is Plato?" Dionysos gestured at the kline at the very end of the room, occupied by two young men. "The dark-haired one."

"THAT is Plato?! I thought he'd be at least in his 30s!" Dionysos grinned a smug grin. "He wrote the Symposion in his late 30s. But this, honeybee, is the year the titular symposion actually took place. The first year of the 91st Olympiad. Or, as you would say, 416 BCE." Seren gaped at the young man seated on a couch with a blond youth. He had long, curly hair crowned with a wreath of ivy like all the symposiasts, young and old. A strong, Greek nose gave his face a distinct personality. Who would have thought the man Seren knew only from his words and artwork showing him as an old man could be so... hot. The blonde guy leaned over, whispering something to him. Maybe they were flirting. It wasn't anything unusual back in the day, Seren knew that. But they seemed to be about the same age. Shouldn't- "Play, flute girl," Dionysos nudged her with his elbow, "I'll clear the kline for you."

Seren watched him shimmy over to the pair and tried to remember how to play the aulos. She had practiced so much but right now it felt as if she knew nothing at all. Her idol, Plato, might be listening! Her cheeks burned as she blew into the wooden instrument, the tune an embarrassing version of "Twinkle Twinkle Little Star". Despite playing the role of a dancer, Dionysos sat down with the two no doubt aristocratic young men in his usual impudent manner. The blond youth's face turned sour. "What is the meaning of this?" "I came for the entertainment." "We are very well entertained by each other's company, thank you." Dionysos gave the blonde guy a cheeky grin. "Does your company agree?" He crawled on the kline until he basically sat on Plato's lap, prompting the young philosopher to blush. How cute! "Some people can be such a dull affair, talking about nothing but themselves all the time." The angry blond yanked Dionysos off Plato. "This was a philosophical symposion before you arrived!" "Yes. And to shame! You are celebrating a victory at the Dionysia. Where is the revelry?" "There are countless symposia all over Athens. Why did you have to come and ruin this one?" "You know exactly that I didn't ruin anything. But please, if you have any grievances take it up with my master. Alkibiades." "You know what? I will!" The blond aristocrat got up from the kline and grabbed Dionysos by the wrist, effectively pulling him off the kline. He dragged the god behind him as he made for the door, leaving Plato all alone on his bed of colourful cushions. Dionysos winked at her as they passed and it was at that moment that Seren noticed that his "friend" was the only one wearing laurel instead of ivy. Did they just... cock-block Apollon? But not all is lost, she reasoned, if Plato likes Apollon, he likes blondes, right? Right?

Shyly, Seren sat down next to the man whose teachings she still hadn't figured out. And maybe neither did he. He was so young and handsome. She was close enough to smell his heavy perfume and either oil or sweat or both made his chest gleam in the firelight. It really was quite hot in here. He didn't fit the stereotype of the philosopher at all, being so young and handsome and quite brawny. But no matter how hot he was, his physical appearance was dwarfed by the beauty of his brain and thoughts. His intelligence was that much hotter. That being said, Seren liked to think she would be less flustered if the man were old enough to be her father. But he was not. He must be about her own age. "We got rid of the other flute girl." "Wa-What?" "You must know there were already celebrations with heavy drinking last night. Surely you played at Alkibiades' place or some other house?" Seren nodded timidly. "So Pausanias suggested we refrain from drinking tonight and we ended up sending away the flute girl as well. A shame, because before you came in, it was all boring speeches of the old men assembled here. I enjoy the delightful harmony of music much, much more." "You don't like philosophy?" "Of course I do, but not at a drinking party celebrating the Dionysia. You're not from here, are you?" "Ahm, no?" "I don't think I've met a Spartan flute girl. Most of them come from Peiraieús." Seren laughed nervously. What the fuck, Hermes?! "I hope it's not a problem?" she mumbled. "No, no. I'm just surprised. Do you have a name, dear?" "I... I am Seren." "Seiren? What a fitting nickname! My name is-" "I know who you are!" Seren gushed, "I-I-I admire you greatly, Plato!" "Oh?" To Seren's great relief he smiled. "So you have seen me compete?" "Uh, yes, of course!" Seren would be thrilled to see him at any competition, really. "It's just a silly name my wrestling coach gave me. To intimidate my rivals, he says." "I like it!" "You like my broad shoulders, Seiren?" Seren blushed. "No, that's not what I, uh..." "It's all right. Lots of women admire them." "Ahahaha." Was he flirting with her? Or just bragging? "You may be an outstanding athlete," she said, "But I admire your words even more." "My poetry?" Now it was his time to blush. "Did you play it?" "Not yet." Seren decided to be bold, "People want to hear the same songs, Sappho, Pindar and the like. But... But maybe you can teach me how to play yours?" "No I... I burned them all." "Why would you do that?" "I wanted to focus better on my studies. Maybe I made the wrong call. Mousaios, the guy who just left? He said music is like medicine and can create harmony between opposites, that a musical education is helpful in the study of philosophy. Ah, I don't know. I don't want to bore you, flute girl." "You're not boring me, Plato. Please, tell me your thoughts!" And then, all of a sudden, a large drunken group walked into the room and joined the party, Dionysos among them. There was noise everywhere, and Plato leaned in very close and asked: "What do you say, Seiren. Shall we make our excuses and leave?"

to be continued...

#Quarantined Bacchae#The Last Bacchae#fanfiction#The Last Bacchae fanfiction#Linda Sejic#fanart#The Last Bacchae fanart#Seren Calvert#Dionysos#Hermes#Platon#Plato#Apollon#Apollo#Seren x Plato epic love story for the ages?#Plato x Apollo missed romance#I hope you have a good laugh#written with love

455 notes

·

View notes

Text

According to tradition, the most important athletic competitions were inaugurated in 776 B.C. at Olympia in the Peloponnesos. By the sixth century B.C., other Panhellenic (pan=all, hellenikos=Greek) games involving Greek-speaking city-states were being held at Delphi, Nemea, and Isthmia. Many local games, such as the Panathenaic games at Athens, were modeled on these four periodoi, or circuit games. The Pythian games at Delphi honored Apollo and included singing and drama contests; at Nemea, games were held in honor of Zeus; at Isthmia, they were celebrated for Poseidon; and at Olympia, they were dedicated to Zeus, although separate games in which young, unmarried women competed were celebrated for Hera. The victors at all these games brought honor to themselves, their families, and their hometowns. Public honors were bestowed on them, statues were dedicated to them, and victory poems were written to commemorate their feats. Numerous vases are decorated with scenes of competitions, and the odes of Pindar celebrate a number of athletic victories.

- Athletics in Ancient Greece, by Colette Hemingway; Met Museum

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ashmolean Advent: Day 13

#AshmoleanAdvent Calendar Day 13 Nike

This image of a winged-Nike flying towards a tripod is found on an Attic red figure pottery jug from 450–430 BC. In ancient Greece, both of these were symbols of victory: Nike translates to 'victory' in Greek, and tripods were regularly given as prizes at games or were erected to commemorate victories in battle. This tripod appears to represent the latter, and the vase itself may also have been made to commemorate a successful battle. The type of vase, an oinochoe, was traditionally used to hold wine.

The garment worn here by Nike bears a striking resemblance to those worn by participants in the Panathenaic procession depicted on the Parthenon frieze carved between c.443–437 BC.

#Ashmolean#Ashmolean Museum#Museum#Oxford#Oxford University#Archaeology#Oinochoe#Wine#Pottery#Ceramics#Attica#Attic Red Pottery#Nike#Art#Art History#Advent Calendar#Advent#Christmas

86 notes

·

View notes