#also there is a comment that art is commentary on society and culture but that's not politics

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

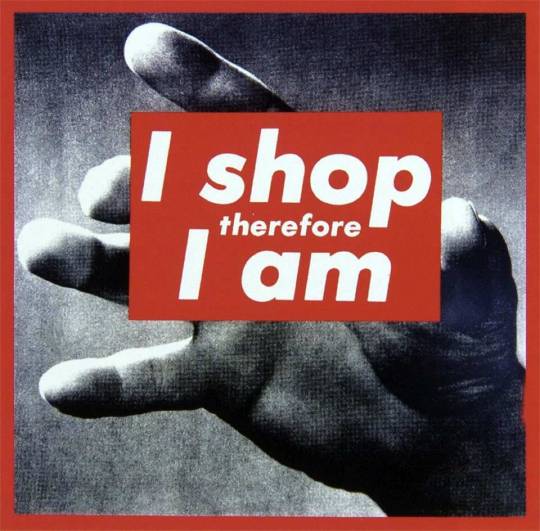

#this is a perspective I’ve only seen from people who truly think broadly and sympathetically about life#like he’s literally right I’m sorry and people who aren’t white or cis or straight learn so so SO early that your existence is political#not inherently but because white cishet men have crafted society in a way it’s impossible for it not to be#and ignoring that isn’t going to make you ascend above it god I’m so tired of having to explain that to people#I’m tired of people’s experiences in both places of privilege and place of oppression being used to scapegoat what we all can see#like look at his example!#‘going out for a dance on a Saturday night’ means something different if you’re poor if you’re gay if you’re a racial minority#’walking into a shop’ who owns it how often do you go is it a big box store or a small owned business is it walkable#there’s pOLitiCs in all of that! in ever aspect of your life!#ESPECIALLY if you take your life experiences and turn them into art of any form (via @twentyfour-mp3)

#hey thanks for these tags#it's why this particular section matters so much to me#also him being Irish is super important here#there's a tendency for colonized nations to be highly aware of the role of art in politics#in no small part because they have experienced first hand how said art was weilded against them#sometimes innocently and sometimes not#with this post exploding past the Hozier fandom#I'm seeing a lot of comments that are borderline vitriolic against this idea#and against my man#all I'll say about it is that our need to continously assert that art is somehow transcendant#and is just for fun is quite transparent#also there is a comment that art is commentary on society and culture but that's not politics#LOL my guy my lady my man my dude#those are topics that are almost entirely political#he literally addresses that here#if it concerns the experience of people then it's political#because we live within a system that enesures that#also an aside; I think this perspective is exactly what makes hozier's love songs have that extra layer to them#that makes them feel different and standout#there's this overlay of awareness of how this functions within a specific set of pre-existing standards for love and its shape#an understanding of power dynamics between genders how they transpire to love#how love is seen from a very cis-het perspective#it's why i always feel uncomfortable separating hozier discography into the political on one side and the yearning love songs on the other#these two are one the same and incredibly linked in my understanding of his work#anyway thanks y'all for engaging with this#but keep the slander to yourself pls#no need ot get nasty to the man or to each other

108K notes

·

View notes

Text

"We're talking about it, aren't we?" — Across the Spider Verse, and its opening statement on canonicity

Canonicity. The accepted norm, the standards of legitimization. There is of course so much to talk about with regards to the comics canon that I am totally unfamiliar with... so I will focus instead on the fun little sequence at the beginning re: the art canon, and ATSV's evocation of art canonicity as an opening statement for its subsequent explorations of canonicity.

Right at the beginning, before Miles's story begins, ATSV destroys the Guggenheim museum.

The Guggenheim museum is not just any gallery, but specifically an art institution strongly associated with the contemporary art (it's also hole shaped but that's not relevant rn). It has the power to legitimize the artworks in it because of its association with the contemporary art canon, which is... ongoing, yet. In general, museums that are respected as art institutions could potentially legitimize non-canon artworks, but only because its adherence to the existing standards of canon has given it that power.

So. The story begins by destroying a legitimizing institution perpetuating an art historical canon of 'high art', through the mediums of 'low art' — animation and comic. The story begins with a Renaissance artist Vulture, from, in Gwen's words, "some Leonardo da Vinci dimension" — his association with an art canon is no coincidence as he also attempts to define what is canon ("You call this art?"), rejects the contemporary art canon by literally destroying it, emphasizing the competing ideas of canon even within those that make it to canon. The story begins, with pop cultural figures of a multiplying canon, spider people of different comics working together to fight the Renaissance artist Vulture that insists on one version of the art canon.

You know what Gwen says in response to Vulture right after he questions the canonicity of contemporary art, and right before they break the Balloon Dog by Jeff Koons?* "We're talking about it, aren't we?" And after they break the Balloon Dog: "Sure it's a meta commentary on what we call art, but it's ... it's also art?". Loops back on itself neatly, really, but what does this mean? That the artwork is canon because it comments on its place in canon? It is canon, because of its relationship to canon? If this sounds like the museum's power inside canon being derived from its relationship with canon, that's because that's how a canon works. The accepted norm is both legitimized by its components and doing the legitimizing of its components, existing to feed itself endlessly — that is what makes them static and resistant to change — the same way Spider Society defines through their commonalities what is canon, become trapped by their own canon, and also perpetuate and enforce that canon.

*Detouring to talk about Balloon Dog by Jeff Koons more, @moonsun2010 for noticing this detail: big balloon dog (spiderverse canon) consisting of small balloon dogs (spider people and the iterations of their individual stories). So! His Balloon Dog(s) are famously identical, reproduced, and mocked to death for that very expensive repetition, and if you've heard, recently one of the smaller ones broke it's like $42k? I don't know if everyone was wondering what's inside one of the bigger ones, but because of the museums preserving its staticity (you are obviously not allowed to touch or destroy artworks inside of a museum), the speculation was meaningless. The act of destruction (in this movie) revealing MORE Balloon Dogs in this artwork both disrupted staticity AND is much more interesting than the pristine, untouched original. Clearly, visitors stuck in ATSV museum think so too: "Oh, that's cool." That's one more point under destroying something that exists for its own self replicating sake to reveal and free an exciting multiplicity!

This art canon parallel refracts beautifully in the SHEER diversity of art styles in this movie, in the commitment to portraying not just different spider-designs, but the mediums their universes are in. To me, that is an extension of the relationship they've established between artistic and narrative canons - there seems to be no limits as to what spiderpeople can look like and how they can be drawn, in clear juxtaposition with the rigidity of their narrative canons. The institution symbolic of an art canon is destroyed at the beginning of this movie. what will be destroyed by the end, from resisting the narrative canon?

To end on a bit of speculation: imo for Gwen "a police captain close to spider person dies to save a child" still works and it didn't really defy canon so much as reinterpret it. A police captain close to spider person dies (quits, death of cop ego, whatever) to save a child (his child, Gwen). so I'm SO interested to see if Miles will find a way to defy canon fr — maybe in the process kicking up another count on the destroying of self perpetuating, static structures?

#atsv#atsv meta#atsv spoilers#spiderverse#across the spider verse#across the spider verse spoilers#across the spiderverse

391 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Revolution X," developed for the Sega Saturn, is a rail shooter game that features the rock band Aerosmith and was set against a dystopian backdrop where music and youth culture are under siege by a tyrannical new order, the "New Order Nation" (NON). The game, released in the mid-1990s, offers a fascinating lens through which to examine the era's social and cultural anxieties, particularly concerning censorship, freedom of expression, and the rebellious spirit of rock music. This analysis explores "Revolution X" through a social commentary perspective, focusing on the historical context of its creation and the broader socio-political themes it reflects.

The early to mid-1990s was a period marked by significant cultural and political shifts. In the United States, the culture wars were intensifying, with debates over the role of art and entertainment in public morality. This was also the era of the PMRC (Parents Music Resource Center), which campaigned against explicit content in music. "Revolution X" tapped into these cultural tensions, framing its narrative around a future where an authoritarian regime has banned all forms of youth culture, particularly music, which it sees as a threat to its control. This setting not only served as a backdrop for the action but also commented on the ongoing debates about censorship and artistic freedom.

"Revolution X" positions players as part of a youth resistance fighting against the NON, which has kidnapped Aerosmith, the symbol of rock rebellion. This premise reflects the 1990s' burgeoning youth movements that often positioned themselves against perceived authoritarian and conservative tendencies in mainstream culture. By choosing Aerosmith, a band known for its rebellious image and often provocative lyrics, the game amplifies its message about the power and importance of cultural resistance. The game becomes a metaphor for the struggle between youthful rebellion and conservative repression, a theme deeply resonant with its target audience of young gamers.

Incorporating the game into the wider discourse on media influence and societal response, "Revolution X" serves as a critique of the era’s fear that media could corrupt youth. This was a time when video games themselves were coming under scrutiny for their violent content and supposed influence on young people. Through its exaggerated depiction of a world where music and video games are literally under attack by the government, "Revolution X" challenges these fears and defends the cultural expression of youth, highlighting the irony and potential dangers of censorship.

"Revolution X" thus provides a unique social commentary embedded within its gameplay and narrative. By setting its action in a dystopian world where freedom of expression is suppressed, the game comments on the real-world cultural battles of its time, offering a defense of the liberating power of rock music and youth culture against authoritarian control. It invites players not only to enjoy the thrill of the game but also to reflect on the broader implications of the cultural and political debates of the 1990s. As such, "Revolution X" remains a fascinating artifact of its time, capturing the spirit of resistance that defined a generation and reminding us of the ongoing debates about the place of art and entertainment in society.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

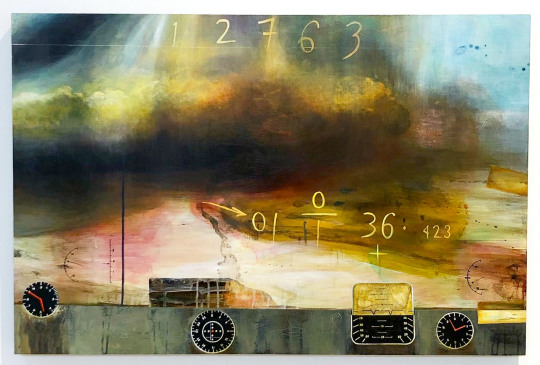

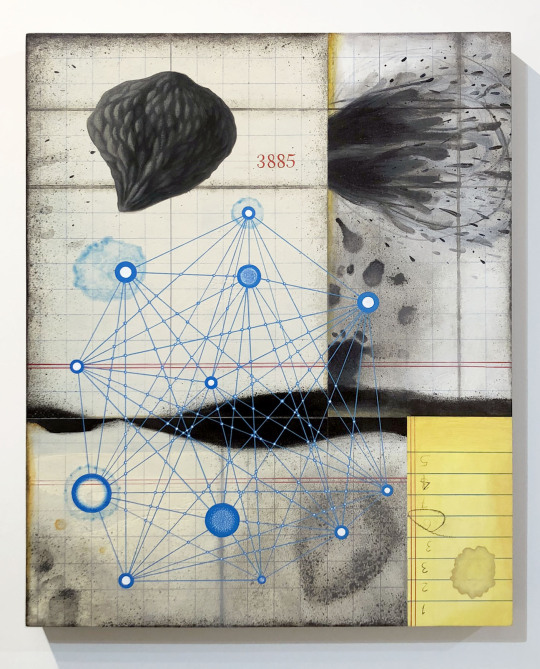

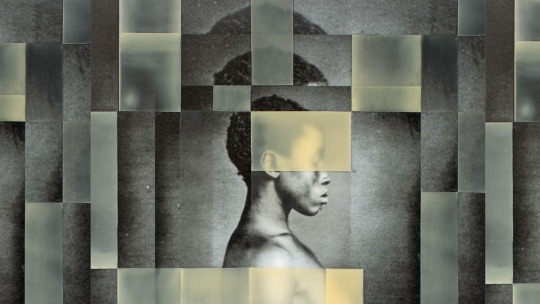

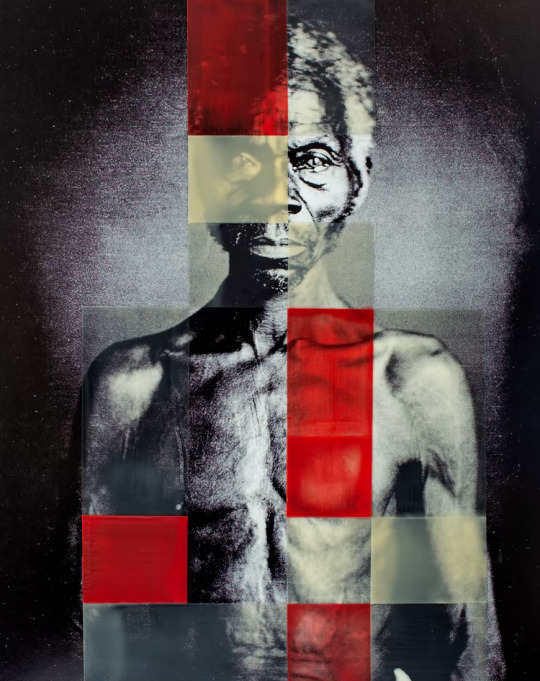

Renée Stout’s exhibition at Marc Straus in NYC, Navigating the Abyss, presents a collection of her recent work in various mediums. From sculpture and painting to photography, her skillful and inventive work draws you in.

From the press release-

Starting out as a photo-realist painter depicting life in everyday urban neighborhoods, Stout soon developed an interest in the mystical and spiritual traditions in African American communities. Fascinated with fortunetelling and the healing power of Hoodoo, Vodou and Santeria still practiced within the African Diaspora in the American Southeast and Caribbean, she delved into ancient spiritual traditions and belief systems. She has drawn inspiration from a wide variety of sources such as current social and political events, Western art history, the culture of African Diaspora, and daily city life. While her artistic practice is rich with references and resonances, her works are eventually unique manifestations of her own imagination, populated by mysterious narratives and imagined characters derived from the artist’s alter ego.

In this exhibition, we encounter a group of portraits depicting Hoodoo Assassins and Agents (#213 and #214) who, in Stout’s imagination, are healers, seers, and empaths from a Parallel Universe in which fairness and balance rules. Erzulie Yeux Rouge (Red Eyes) is a spirit from the Haitian Pantheon of spirits whose empathic nature makes her a fierce guardian or protector of women, children, and betrayed lovers. Ikengas, originating in the Igbo culture of Southeastern Nigeria, are shrine figures that are meant to store the owner’s chi (personal god), his ndichie (ancestors) and his ike (power), and are generally associated with men. Stout’s Ikenga (If You Come for the Queen, You Better Not Miss) is a powerful female figure with her breasts and horns turned into weapons, and she is adorned with jewels and charms to boost her powers. Beyond the playful yet powerful imagination of these female characters are serious undertones of political commentary as Stout ponders the concepts of these deities while witnessing the recent rulings in our society that infringe on women’s rights.

In Escape Plan D (With Hi John Root, Connecting the Dots) Stout maps out her potential escape to the Parallel Universe when the daily news weighs unbearably on her psyche.

Visions of the Fall, in Thumbnails is a series of five small paintings that comments on the current state of our world and its imagined future with the titles as upcoming stages of its evolution.

American Memory Jar is an entirely black sculpture consisting of a glass jar covered with thin-set mortar, plastic and metal toy guns, topped with a doll head and adorned with a bead and rhinestone cross pendant. Memory Jugs are an American folk-art form that memorializes the dead adorned with objects associated with the deceased. Stout’s jar is a bitter but painfully accurate assessment.

While Stout’s work alludes to history, racial stereotyping, societal decay, and a set of alarming tendencies in our socio-political structures and ecosystem, it also reveals possibilities and the promise of healing. Various works reference healing herbs, potions, and dreams. Herb List, Spell Diagram and The Magic I Manifest speak of Stout’s belief in the power of consciousness, in the existence of more solid and fertile grounds, and of individual responsibility.

There is one overarching narrative that clearly emerges from Stout’s work – her personal history and spiritual journey as a woman and as an artist.

This exhibition closes 3/5/23.

#renée stout#marc straus#marc straus gallery nyc#nyc art shows#painting#sculpture#mixed media#art installation#art#art shows#christopher wool

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Funny Girls: Evolving female narratives in 21st century British stand-up comedy.

Now that it's all over, the Funny Girls critical rationale for your viewing pleasure...

Part I. Introduction

Funny Girls is a multimedia project discussing women in comedy, through a print zine, as well as an online platform. Eleanor Tomsett in her thesis states ‘Stand-up comedy as an art form has emerged from, and been developed within, male dominated spaces’. (2019). This project aims to challenge these patriarchal industry structures and platform female comics, who have continuously had to battle with the stereotype that women aren’t funny, perpetuated by attempts to investigate scientific or philosophical reasons for this as in Christopher Hitchens’ ‘Why Women Aren’t Funny,’ (2007). This project was inspired by the limited research on women in British comedy, and it hopes to prove that these women are worthy of further study and promotion as narratives around gender in comedy evolve in the 21st Century. Additionally, it aims to explore the zine as a vessel for both female liberation and fandom, justifying it as the perfect medium for the subject matter.

In this rationale I will discuss the contextual background of women in comedy, how narratives have shifted in light of the #metoo movement, the importance of intersectionality, and social media’s impact on stand-up comedy. I will explore riot grrrl and science fiction fanzines as notable comparisons to my project in zine history. Further, this rationale will cover the research methods, requirements, and practical output for this project. It will also reflect on the timeline originally set out in the project proposal, noting any changes.

Part II. Conceptual Framework

It is fairly recently that a larger number of academics have begun to delve into the study of contemporary performed comedy, with the first Comedy Studies journal published in 2010. However, the analysis of the place of humour in society, in such works as Taking Laughter Seriously (Morreall, 1983), has been prevalent. Stand-up comedy can be traced back as far as the Middle Ages, to court jesters and fools. In his 1985 article Standup Comedy as Social and Cultural Mediation, Lawrence Mintz describes the ‘undervalued genre’ of stand-up as ‘the purest public comic communication’ and as a ‘vitally important social and cultural phenomenon’ (1985, p.71) – one which has developed significantly since his time of writing, necessitating updated analyses. Mintz additionally observes that American female comics at the time, such as Joan Rivers or Phyllis Diller, were ‘voicing changing attitudes about gender roles […] as a result of the most recent wave of feminist agitation’ (1985, p.75). Indeed, as feminists have become more agitated over the years, it has become evident that the content performed by female comics is often a helpful social commentary on gender roles, whether direct or indirect. Much of the literature on comedy favours discussions about the American landscape, and Tomsett notes that women ‘have been considerably overlooked in existing literature on UK comedy in favour of male performers.’ (2019, p.11). Therefore, this project aims to bring female comics operating in the UK to the forefront.

In recent years, female comedians have become more prominent in the UK, which could be partially attributed to increased visibility on television and in particular comedy panel shows. Lawson & Lutsky’s linguistic study of Mock the Week season five, which aired in 2007 and of seasons 1-14 featured the most women, showed that the five female guests across the season contributed just 4% of the overall words spoken (2016, p.151). This statistic is indicative of the culture around female comics at the time, and industry veterans Victoria Wood and Sandi Toksvig had both criticised the ‘laddish’ nature of panel shows, with Wood commenting that “A lot of panel programmes are very male dominated, because they rely on men topping each other, or sparring with each other, which is not generally a very female thing,” (Khan, 2009). In 2014, BBC chief Danny Cohen announced that, following recommendations from the BBC Trust, the BBC would no longer produce any panel shows that featured an all-male cast (Cooke, 2014). The ‘UK Panel Show Gender Breakdown’ database, created by Stuart Lowe, monitors every appearance on a panel show and categorises them by gender, collating data from 1967 to present (2024). The data indicates a positive trend in the increasing presence of female guests, with significant improvement since Cohen’s 2014 announcement – In 2014 the ratio of male to female appearances was 71:29 and in 2023 this had increased to 62:38.

Another notable shift in the female comedic narrative has been changing attitudes in a post #metoo era. As the culture of women being silenced has evolved, both male and female comedians since 2020 have become much more vocal about issues in the industry. British comedy in particular has seen its own movement pushed forward with the release of Channel 4 Dispatches investigation on sexual assault allegations against Russell Brand. Comedian Lucy Beaumont explains that comedy is rife with predators, as where ‘in any workforce you would go to HR’ comedy doesn’t have a similar structure due to its freelance nature (Chrisp, 2023). Between Katherine Ryan and Sara Pascoe openly discussing these issues in Backstage with Katherine Ryan (2022), and the dramatization of Richard Gadd’s experience with an abuser in the industry in Baby Reindeer (2024) it is clear that this discussion is becoming less taboo. This is indicative of a changing narrative as in sharing their stories women can take control and ensure predatory behaviour is not normalised.

It is true that there has been significant progress for women in comedy, but arguably this success primarily extends to white women. Lucy Spoilar discusses how UK media has set up the idea of ‘the humourless Muslim woman’, essentially doubling down on the notion that Muslim women are oppressed and inexplicably reaching the conclusion that they would therefore not be able to engage in humour (2022, p.75-77). Jessyka Finley asks, in reference to black women in stand-up comedy, how marginalised communities can create art ‘when their aesthetic and rhetorical choices sometimes perpetuate stereotypes’ (2016, p.781). These are just short examples demonstrating that women of colour have to work twice as hard to succeed in comedy as they work against stereotypes and discrimination. Therefore, this project has taken an intersectional approach, prioritising platforming women from a variety of backgrounds.

One recent development for mobility in comedy has been the virality of social media clips. In my interview with Mary O’Connell, she commented on the impact that the pandemic had in this regard –

“We didn’t know what would happen with live so lots of people turned to online content […]. Stuff that works for live doesn’t always work for online and vice versa but I really admire the creativity of the comics who are able to do both.” (2024)

It’s an evolution that has allowed comics to expand their audiences, and in general has attracted more fans to stand-up comedy as a whole. Additionally, it has birthed a new genre in short form comedy, and comedians such as Mawaan Rizwan, Rosie Holt, and Munya Chawawa have actually started out online and later transitioned to live comedy, circumventing the traditional route of performing at smaller circuit gigs. However, some comedians have noted negative consequences of the viral video. As the popular videos on TikTok and Instagram often feature crowd work, new audience members go to shows with the expectation that they are supposed to interject throughout, leading to an increase in heckling (Stahil, 2023). I observed this during my primary research, when attending a work in progress show in which comedian Danny Scott was barely able to get halfway through his set during the allotted time due to the severity of audience interruptions – I spoke with him in the interval, and he expressed that he had noticed more heckling overall and was finding it difficult to deal with. Another issue with these viral clips is that the jokes can age quickly, audiences could be disappointed to hear a viral joke live a year after it was first circulating online. Social media can do wonders for a comedian’s career, helping shows sell out overnight, and massively boosting interest in a way that just cannot happen organically. However, the onus is on new audiences to make an effort to understand and respect etiquette at live events.

Funny Girls as a zine is intended to be reminiscent of the punk riot grrrl era, coming as ‘a direct response to the dominance of straight white men’ originally in the punk scene but here transposed to the British comedy landscape (Darms, 2013, p.7). In addition to being an homage to punk female liberation zines, it is also essentially a fanzine for stand-up comedy. The first British fanzine was a Novae Terrae released in 1936, a print for science fiction lovers. At first the content of these early science fiction zines was serious, or ‘sercon’, but around the 1950s that developed into ‘fannish’, which had more of a focus on fandom (Hansen, 2022, p.7). The traditions of fandom and feminism within zine culture solidified zines as the most appropriate vessel for Funny Girls as a project. Jeanne Scheper notes that whilst zines are an analogue form, the ‘qualities of self-making, self-publishing, and participatory community-building across time and space’ are reminiscent of digital social media platforms familiar to Gen Z and suggests that this may be the reason for their recent resurgence in popular culture (2023, p.22). Based on this, Funny Girls extends past solely a print endeavour, offering a digital extension in the form of a Tumblr blog.

Part III. Methods

My intention had been to conduct interviews with several female comedians, but after reaching out to the comedians featured in the zine, I did not have much success. Mary O’Connell was the only comedian who was able to engage with the interview questions. This lack of response meant that I needed to reconsider my approach to the articles in the zine. Reflecting on this, I should have cast a wider net and explored further avenues past simply messaging on social media. I was quite rigid in wanting to feature these exact comedians, but I should have just messaged a wider range and been more open to including further features. If I were to do it again, I would also contact agencies, promoters, or other industry specialists. It also might have helped to send an example or overview of the zine to show what the tangible product would be and possibly foster more interest or desire to participate.

Despite the setback in securing personal interviews, I was able to engage with the abundance of high-quality text, video, and audio interviews available online. These provided valuable insights and featured a lot of relevant information, giving me confidence that I would still be able to create solid profiles/features for each comedian.

Watching the documentaries ‘Caroline Aherne: Queen of Comedy’ (2023) and ‘Victoria Wood: The Secret List’ (2020) was very insightful in contextualising the evolution of female comedy and pre-2000s influence on contemporary comedians.

Visiting the Glasgow Zine Library was crucial for the development of this project, seeing a diverse collection of zines that followed no defined path was very inspiring. Exploring different styles and themes helped immensely with both the visual development of the zine and with narrowing down content decisions.

Tomsett’s thesis Reflections on UK Comedy’s Glass Ceiling: Stand-Up Comedy and Contemporary Feminisms, previously mentioned, informed much of my practice as one of the only comprehensive studies of women in the British comedy industry.

Part IV. Practical piece

I am really pleased with the final product as it has a strong identity. It is pink, both in reference to the riot grrrl zine ‘I (Heart) Amy Carter’, and as an unashamed embracing of a typical ‘girl colour’ (Dockertman, 2023). The Funny Girls logo is a deliberate feminisation of the iconic Comedy Store laughing mouth, serving as both a homage and an acknowledgement of the patriarchal nature of classic comedy institutions. Later, when deciding how many copies to print, I realised that it could potentially become a copyright issue if I were to distribute it on a wider scale.

Navigating the printing process was fairly challenging, as I wasn’t sure how to choose page weight and finish. Extensive research into publishing standards was undertaken to determine my desired print quality.

I chose to do a Tumblr blog as the extension of the zine, rather than a website as originally planned, because this felt more in line with the homemade spirit of zines. A website felt too corporate and polished and would be more appropriate for a magazine. Tumblr’s posting format offers the flexibility needed to link to external sites, accommodate long-form entries, and share visuals, making it ideal for the project’s needs over other social media platforms.

The relationship between the zine and its digital extension is what distinguishes Funny Girls from conventional zine projects. Where the print zine would be maybe a quarterly print, the blog would serve as a constantly updating real-time archive of supplementary content. I like the idea that some of the audience would find it online as relevant to their interests (zines or comedy) but that a physical copy could intrigue a potential reader who scans a code to find out more and is presented with a wealth of further information. In the future, I plan to review and reprint the zine with no time sensitive information so that it can be circulated without dating quickly.

The incorporation of QR codes modernise the traditional zine format and make it interactive, which I love and think works well – when I visited the Glasgow Zine Library there were many copies that I wished I could’ve engaged with further. I’d hoped to circulate the zines to analyse the data on QR code usage but due to time constraints this was not possible.

A digital version of the zine has also been published via Issuu, a site that allows readers to flick through the pages in the same way as they would if they had the paper copy. This means that double page spreads can be viewed as intended, and any online fans would be able to access the zine content without needing to track down a physical version.

Part V. Project requirements

The zine was created using a combination of Procreate and Canva. Initially, the intention was to preserve the homemade quality typical of zines, but Procreate’s lack of text functionality proved challenging. Handwriting was impractical as it required constant erasing and resizing for edits. Ultimately, I decided that it was worth sacrificing the handmade look and turned to Canva for its familiar interface and useful tools. As my visit to the Glasgow Zine Library exposed me to digitally produced zines with more polished aesthetics, I felt confident that the zine did not necessarily need to look ‘raw’. I created the zine using a magazine template, then ended up having to purchase Canva Pro to resize it down to A5 for printing. This cost could have been avoided if I had more thoroughly researched the printing requirements.

I had also experimented with a free downloadable programme called Electric Zine Maker that offered more artistic options as well as text, which originally felt like a great compromise. The features were excellent, but the programme was only available on laptop or PC, and I found it quite difficult using the art features on a mousepad rather than with a stylus, so did not go for this option in the end.

To complete my primary research, I had to buy a lot of tickets to various comedy shows, ranging from £1 to £20+, along with the associated travel costs. If funds had allowed, I would have liked to attend more shows to better inform my practice. As a lone woman attending often late-night events, I had to also factor in the locations of the gigs in consideration of my safety.

Part VI. Project timeline

The timeline originally set out was delayed a little more than I would have liked. I delayed things in hope that I might get more responses from those I’d reached out to for interviews, as their insights were crucial to the depth of my project. Despite this impact, I feel that I was able to effectively manage the project timeline.

I ended up actually creating the zine in a shorter timeframe than planned, having decided to separate the design process from the content creation. Rather than simultaneously designing and writing, I wrote the content in Word whilst experimenting with designs on the side, then assembled the entire thing at a later stage. This approach streamlined the process and allowed me to focus more deeply on each aspect.

It was actually quite useful that I didn’t design until later, as I ended up using Procreate in another module, the Transmedia Horror strand of Issues in Contemporary Media. This gave me time and space to build on those skills and familiarise myself with the features in the app. When it came to designing the zine, I felt more adept and confident in my abilities, enabling me to complete it quickly.

Throughout the project, I maintained active engagement by consistently updating the Tumblr page and immersing myself in relevant events such as gigs and exhibitions. Additionally, interacting with zine creators online and at the Glasgow Zine Library allowed me to visualise the format before creation. These activities ensured that the project remained at the front of my mind, ready to apply months of primary research when it came to putting the project together.

To keep myself organised and on track, I compiled a checklist covering every single task that needed to be completed, no matter how small. This approach ensured that even when the timeline deviated from the original plan, I could maintain realistic expectations and manage the progression smoothly.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this project has successfully met its aims in creating a multimedia platform for the promotion of female comics operating within the British comedy scene. It has additionally highlighted the possibilities in modernising the zine format in a digital world.

Bibliography

Baby Reindeer (2024). Netflix, 11 April.

Caroline Aherne: Queen of Comedy (2023). BBC Two Television, 25 December.

Chrisp, K. (2023). ‘Lucy Beaumont warned of ’10 male predators’ on comedy circuit weeks before Russell Brand allegations’, Metro, 19 September. Available at https://metro.co.uk/2023/09/19/russell-brand-lucy-beaumont-comedy-predators-19519860/ (Accessed: 1 May 2024)

Cooke, R. (2014). ‘Danny Cohen: ‘TV panel shows without women are unacceptable’, The Guardian, 8 February. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/media/2014/feb/08/danny-cohen-bbc-director-television-tv-panel-shows (Accessed: 29 April 2024).

Darms, L. and Fateman, J. (2013). The Riot Grrrl Collection. New York: The Feminist Press.

Dockertman, E. (2023). ‘Is Pink Still a ‘Girl Color’? An Exploration’, TIME Magazine, 31 August. Available at https://time.com/6309632/is-pink-girl-color-barbie/ (Accessed: 27 April 2024)

Finley, J. (2016) ‘Raunch and Redress: Interrogating Pleasure in Black Women’s Stand-up Comedy’, Journal of popular culture, 49(4), pp. 780-798.

Hansen, R. (2022). Interview by Hamish Ironside. We Peaked at Paper: An Oral History of British Zines, pp. 1-36.

Hitchens, C (2007). ‘Why Women Aren’t Funny’, Vanity Fair, 1 January. Available at (https://www.vanityfair.com/culture/2007/01/hitchens200701) (Accessed: 4 May 2024)

Khan, U. (2009). ‘TV Panel shows are too ‘male dominated’, claims Victoria Wood’, The Telegraph, 9 June. Available at https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/culturenews/5478241/TV-panel-shows-are-too-male-dominated-claims-Victoria-Wood.html (Accessed: 29 April 2024).

Lawson, R. & Lutsky, U. (2016). ‘Not getting a word in edgeways? Language, gender, and identity in a British comedy panel show. Discourse, context & media. 13, pp.143-153.

Mintz, E. (1985). ‘Standup Comedy as Social and Cultural Mediation’, American Quarterly. 37 (1), pp.71-80.

Morreall, J. (1983). Taking Laughter Seriously. Albany: State University of New York.

O’Connell, M. (2024). Interviewed by Olivia Jones. 20 April, via Instagram.

‘Predatory Behaviour’ (2022). Backstage with Katherine Ryan, S01E02, Amazon Prime Video.

Scheper, J. (2023). ‘Zine Pedagogies: Students as Critical Makers’, Radical teacher (Cambridge), 125, pp. 20-32.

Spoilar, L. (2022) ‘Comedy, Inclusion, and the Paradox of Playing with Stereotypes: Representations and Self-Representations of Muslim Women in British TV Sitcoms and Stand-Up Comedy’, Dive In, 2(1), pp. 73-93).

Stahil, M. (2023). ‘Is Social Media Killing Stand-Up Comedy?’, Inside Hook, 12 December. Available athttps://www.insidehook.com/internet/social-media-killing-stand-comedy (Accessed: 5 May 2024)

Tomsett, E. (2019). Reflections on UK Comedy’s Glass Ceiling: Stand-Up Comedy and Contemporary Feminisms. PhD Thesis. Sheffield Hallam University. Available at: https://shura.shu.ac.uk/26442/2/Tomsett_2019_PhD_ReflectionsOnUK_edited.pdf (Accessed: 29 April 2024)

UK Panel Show Gender Breakdown (2024). Strudel. [Database]. Available at https://www.strudel.org.uk/panelshows/index.html (Accessed: 29 April 2024)

Victoria Wood: The Secret List (2020). BBC Two Television, 25/26 December.

0 notes

Text

GELA MIKAVA: Capturing the Emotional Complexities of Contemporary Life

GELA MIKAVA’s artwork presents a powerful visual exploration of the psychological and emotional states defining today’s world. Through his distinct use of color and form, MIKAVA delves into the nuanced inner lives of individuals grappling with the complexities of modern identity, relationships, and self-awareness. His pieces often feature figures that appear ambiguous and fragmented, symbolizing the constantly shifting and uncertain identities people navigate in today’s fast-paced, media-driven culture.

A notable aspect of MIKAVA's style is his use of contrasting colors and intense expressions. These elements evoke feelings of isolation and anxiety that resonate deeply in an era where digital interactions frequently replace human connections. His works raise questions about the authenticity of relationships and self-perception in a world where technology often serves as an intermediary. By doing so, MIKAVA not only addresses the psychological pressures faced by individuals but also sheds light on the socio-emotional tensions characteristic of modern life.

Beyond exploring interpersonal and identity-based themes, MIKAVA's artwork frequently comments on the materialistic and status-driven motivations that can trap individuals in restrictive social frameworks. His figures, depicted with a dreamlike fluidity, seem to struggle against these societal limitations, expressing a longing for genuine freedom and self-discovery. Through his art, MIKAVA provides viewers with a symbolic journey that encourages them to confront their own emotional and psychological landscapes.

In essence, GELA MIKAVA’s work serves as a striking commentary on the human condition within contemporary society. His use of ambiguous forms and vibrant color schemes captures the complexity and depth of modern emotional experience, making his work both thought-provoking and deeply relatable.

0 notes

Text

Ando Hiro: The Neo-Pop Sculptor Bridging Tradition and Modernity

Ando Hiro, a prominent Japanese artist, has garnered international acclaim for his striking neo-pop sculptures, which blend the vibrant energy of modern Japanese culture with a deep reverence for traditional aesthetics. Through his art, Ando challenges viewers to examine contemporary society's relationship with both technology and tradition, exploring themes that resonate across cultural boundaries. Known for his polished works that often depict samurai warriors, animals, and futuristic characters, Ando’s art captivates audiences through its visual intensity and thought-provoking themes.

Early Life and Influences

Born in Tokyo, Japan, Ando Hiro Art artistic journey began with a fascination for both manga and traditional Japanese art. Growing up in a post-industrial Japan, Ando witnessed the rapid technological advancements and the emergence of a globalized, pop culture-driven society. His early exposure to manga, anime, and the burgeoning art of video games instilled in him a love for bright colors, bold forms, and fantastical elements that would later define his work. But beyond these modern influences, Ando was equally inspired by Japan’s rich history, particularly the samurai and their values of honor, courage, and discipline.

While many contemporary artists emphasize minimalism or abstraction, Ando took a different path, focusing on creating art that is bold, vibrant, and accessible. He studied various mediums and techniques but found his unique voice in sculpture. He developed a neo-pop style that combines high-gloss finishes and cartoonish exaggerations with themes of Japanese mythology and contemporary issues, making his works stand out both in Japan and internationally.

Artistic Style and Mediums

Ando Hiro is best known for his highly polished sculptures that blend cartoon-like figures with sophisticated forms. His medium of choice is often resin or bronze, materials that allow him to create the smooth, glossy surfaces for which he is famous. Many of his sculptures are iconic in their simplicity yet packed with complex symbolism. For example, his samurai sculptures are typically sleek, polished figures with exaggerated, playful forms that bring out both the heroism and vulnerability of these historical warriors.

One of Ando’s signature pieces is his series of "Cat Samurai" sculptures. These works showcase a fusion of traditional samurai armor with a cat's face, playfully merging past and present while giving the fierce figure a soft, endearing twist. These statues are often brightly colored in reds, blues, and yellows, drawing influence from pop art and further contributing to their contemporary appeal. Through these cats, Ando connects with a Japanese cultural symbol often associated with good fortune, while reinterpreting it through a modern lens.

Neo-Pop and Social Commentary

A defining feature of Ando Hiro's work is his commentary on the interplay between tradition and modernity. Neo-pop, a style that gained popularity in the late 20th century, focuses on commercial culture, celebrity, and consumerism. Ando's sculptures take these themes and embed them within Japan’s dual cultural identity—where ancient customs coexist with high-tech advancements. His works often explore the way technology impacts human values, particularly through the lens of Japanese society, which uniquely balances rapid technological growth with a respect for heritage and tradition.

For instance, Ando’s frequent portrayal of samurai figures in ultra-modern, glossy finishes can be seen as a comment on how ancient ideals of honor and respect remain relevant even in a digital, fast-paced world. His bright, candy-like color palettes highlight the tension between the appeal of instant gratification and the timeless value of traditional ideals.

Global Influence and Legacy

Art Hiro Ando work has not only been showcased in Japan but has also gained international acclaim, particularly in galleries across Europe and North America. His art resonates globally because it addresses universal themes of identity, consumerism, and cultural nostalgia. The sculptures invite viewers to reflect on the contradictions of a world where tradition and modernity often clash but also coexist harmoniously.

Through his art, Ando Hiro has positioned himself as a modern-day storyteller, bridging generations and cultures. His unique ability to create pieces that are both visually appealing and thematically rich has made him one of the defining voices in contemporary Japanese art. As he continues to produce new work, Ando’s sculptures serve as reminders of the importance of preserving tradition in a world where change is the only constant.

In a time when cultural identities are rapidly evolving, Ando Hiro’s art offers a creative commentary on what it means to embrace both history and the future—a delicate balancing act that resonates universally.

0 notes

Text

The Kingdom of Kongo and Palo Mayombe: Reflections on an African-American Religion

Abstract

Historical scholarship on Afro-Cuban religions has long recognized that one of its salient characteristics is the union of African (Yoruba) gods with Catholic Saints. But in so doing, it has usually considered the Cuban Catholic church as the source of the saints and the syncretism to be the result of the worshippers hiding worship of the gods behind the saints. This article argues that the source of the saints was more likely to be from Catholics from the Kingdom of Kongo which had been Catholic for 300 years and had made its own form of Christianity in the interim.

Acknowledgements

Research funding for this project was supplied by Boston University Faculty Research Fund and the Hutchins Center of Harvard University. Earlier versions were presented at the Hutchins Center, and the keynote address at ‘Kongo Across the Waters’ in Gainesville, FL. Thanks to Linda Heywood, Matthew Childs, Manuel Barcia, Jane Landers, Carmen Barcia, Jorge Felipe Gonzalez, Thiago Sapede, Marial Iglesias Utset, Aisha Fisher, Dell Hamilton, Grete Viddal and Kyrah Daniels for readings, comments, questions and source material.

[1] Robert Farris Thompson, Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy (New York: Random House, 1983), pp. 17–8; see also Face of the Gods: Art and Altars of Africa and African America (New York: Prestel, 1993). For Cuba in particular, see David H. Brown, Santería Enthroned: Art, Ritual and Innovation in an Afro-Cuban Religion (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2003), p. 34 (with ample references to earlier visions).

[2] Georges Balandier, Daily Life in the Kingdom of the Kongo (New York: Allen and Unwin, 1968 [French Version, Paris, 1965]) and James Sweet, Recreating Africa: Culture, Kinship and Religion in the African-Portuguese World, 1441–1770 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003).

[3] Ann Hilton, The Kingdom of Kongo (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984), for the role of the Capuchins in discovering problems with Kongo's Christianity. John Thornton, ‘The Kingdom of Kongo and the Counter-Reformation’, Social Sciences and Missions 26 (2013): 40–58 contextualizes their role and their problems with Kongo's Christianity.

[4] Adrian Hastings, The Church in Africa, 1450–1950 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994); this position is often implicit in the many histories written by clerical historians such as Jean Cuvelier, Louis Jadin, François Bontinck, Teobaldo Filesi, Carlo Toso and Graziano Saccardo, whose work has presented modern editions of the classical work of the Capuchin missionaries, commentaries and at times regional histories, such as Saccardo, Congo e Angola con la storia del missionari Capuccini, Vol. 3 (Venice: Curia Provinciale dei Cappuccini, 1982–1983). For both a position of dependence on missionaries and a recognition of local education, Louis Jadin, ‘Les survivances chrétiennes au Congo au XIXe siècle’, Études d'histoire africaine 1 (1970): 137–85.

[5] It is not mentioned at all in his seminal work, Thompson, Flash of the Spirit in the nearly 100-page section dealing with Kongo and its influence in Vodou, nor in Face of the Gods.

[6] Erwan Dianteill, ‘Kongo à Cuba: Transformations d'une religion africaine', Archives de Sciences Sociales de Religion 117 (2002): 59–80.

[7] Todd Ochoa, Society of the Dead: Quita Manaquita and Palo Praise in Cuba (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010), pp. 8–10. Wyatt MacGaffey's work, especially Religion and Society in Central Africa: The BaKongo of Lower Zaire (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1986) is a favorite.

[8] Thiago Sapede, Muana Congo, Muana Nzambi a Mpungu: Poder e Catolicismo no reino do Congo pós-restauração (1769–1795) (São Paulo: Alameda, 2014) is the first book length study of Christianity in the later period of Kongo's history.

[9] John Thornton, ‘Afro-Christian Syncretism in the Kingdom of Kongo', Journal of African History 54 (2013): 53–77.

[10] Thornton, ‘Afro-Christian Syncretism'.

[11] Sapede, Muana Congo, pp. 248–57.

[12] Thornton, ‘Afro-Christian Syncretism', for the details of the struggle, but a perspective that sees the Capuchin mission as central to Kongo Christianity, see Saccardo, Congo e Angola.

[13] John Thornton, The Kongolese Saint Anthony: D Beatriz Kimpa Vita and the Antonian Movement, 1684–1706 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

[14] Rafael Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem ao Congo’, Academia das Cienças de Lisboa, MS Vermelho 396, pp. 32–4, 183–5 (transcription by Arlindo Carreira, 2007 at http://www.arlindo-correia.com/161007.html) which marks the pagination of the original MS.

[15] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem ao Congo', pp. 110–4.

[16] Raimondo da Dicomano, ‘Informazione' (1798), pp. 1–2. The text exists in both the Italian original and a Portuguese translation made at the same time. For an edition of both, see the transcription of Arlindo Carreira, 2010 (http://www.arlindo-correia.com/121208.html).

[17] ‘Il Stato in cui si trova il Regno di Congo', September 22, 1820, in Teobaldo Filesi, ‘L'epilogo della ‘Missio Antiqua’ dei cappuccini nel regno de Congo (1800–1835)’, Euntes Docete 23 (1970), pp. 433–4.

[18] Among the first was Domingos Pereira da Silva Sardinha in 1854, who, according to King Henrique II of Kongo, had performed his duties of administering the sacraments with ‘all the necessary prudence', Henrique II to Vicar General of Angola, December 14, 1855, Boletim Oficial de Angola, 540 (1856).

[19] Biblioteca d'Ajuda, Lisbon, Códice 54/XIII/32 n° 9, Francisco de Salles Gusmão to the King, October 27, 1856.

[20] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem ao Congo’, pp. 110–4.

[21] da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', pp. 1–7 (of manuscript).

[22] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 39, 69, 276.

[23] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagen', p. 217 (thanks to Thiago Sapede for this reference).

[24] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem’, pp. 32–4, 1835.

[25] For a thorough study of these religious artefacts and their meaning, see Cécile Fromont, The Art of Conversion: Christian Visual Culture in the Kingdom of Kongo (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014).

[26] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', p. 78.

[27] APF Congo 5, fols. 298–298v (Rosario dal Parco) ‘Informazione 1760' A French translation is found in Louis Jadin, ‘Aperçu de la situation du Congo, et rite d’élection des rois en 1775, d'après le P. Cherubino da Savona, missionaire de 1759 à 1774', Bulletin de l'Institut Historique Belge de Rome 35 (1963): 347–419 (marking foliation of original MS).

[28] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 180–4.

[29] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', p. 53.

[30] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 63–4; see also 87 for another noble as Captain of Church; 136 crowds at Mapinda.

[31] da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', pp. 1–7.

[32] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', p. 196.

[33] Bernard Clist et alia, ‘The Elusive Archeology of Kongo Urbanism, the Case of Kindoki, Mbanza Nsundi (Lower Congo, DRC)’, African Archaeological Review 32 (2014) 369–412 and Charlotte Verhaeghe, ‘Funeraire rituelen en het Kongo Konigrijk: De betekenis van de schelp- en glaskralen en de begraafplaats van Kindoki, Mbanza Nsundi, Neder-Kongo' (MA thesis, University of Ghent, 2014), pp. 44–50.

[34] ‘Il Stato in cui si trova il Regno di Congo', September 22, 1820, in Filesi, ‘Epilogo’, pp. 433–4.

[35] ‘O Congo em 1845: Roteiro da viagem ao Reino de Congo por Major A. J. Castro … ’, Boletim de Sociedade de Geographia de Lisboa II series, 2 (1880), pp. 53–67. The orthographic irregularity reflects the actual pronunciation of these terms in the São Salvador region (the Sansala dialect).

[36] Alfredo de Sarmento, Os sertões d'Africa (Apontamentos do viagem) (Lisbon: Artur da Silva, 1880), p. 49 and Adolf Bastian, Ein Besuch in San Salvador: Der Hauptstadt des Königreichs Congo (Bremen: Heinrich Strack, 1859), pp. 61–2.

[37] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 102–3 and da Firenze, ‘Relazione', pp. 420–1.

[38] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', p. 137.

[39] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 180–4.

[40] da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', pp. 1–7.

[41] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 32–4; da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', pp. 1–7; Zanobio Maria da Firenze, ‘Relazione della Stato in cui si trovassi autalmente il Regno di Congo … 1814’, July 10, 1816, in Filesi, ‘Epilogo’, pp. 420–1.

[42] Archivio ‘De Propaganda Fide' (Rome) Acta 1758, ff 213–9, no. 16, Relazione di Rosario dal Parco, July 31, 1758. These large numbers were not simply priests catching up on people who had not been baptized for a long time, as personnel staffing and statistics are found from 1752 onward; but the priests did not cover the whole country every year, so many priests would baptize babies all under age two or three.

[43] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 63–4; see also 87 for another noble as Captain of Church; 136 crowds at Mapinda.

[44] da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', pp. 1–7.

[45] da Firenze, ‘Relazione', pp. 420–1.

[46] ‘Il Stato in cui si trova il Regno di Congo', September 22, 1820, in Filesi, ‘Epilogo’, pp. 433–4.

[47] Francisco das Necessidades, Report, March 15, 1845, in Arquivo do Archibispado de Angola, Correspondência de Congo, 1845–1892, cited in François Bontinck, ‘Notes complimentaire sur Dom Nicolau Agua Rosada e Sardonia’, African Historical Studies 2 (1969): 105, n. 6. Unfortunately, no researchers have been allowed to work in this section of the archive for many years and so the actual text is not available.

[48] Report of November 13, 1856 in António Brásio, ‘Monumenta Missionalia Africana’, Portugal em Africa 50 (1952), pp. 114–7.

[49] Biblioteca d'Ajuda, Lisbon 54/XIII/32 n° 9, Francisco de Salles Gusmão to the King, de Outubro de 27, 1856.

[50] Da Cruz, entry of October 8 and 25 on the problems of baptizing people.

[51] da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', is the first to describe this process; for more detail see Bastian, Besuch.

[52] David Eltis, An Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

[53] For a recent discussion of names and nomenclature, see Jésus Guanche, Africanía y etnicidad en Cuba (los componentes étnicos africanos y sus múltiples demoninaciones (Havana: Editoria de Ciencias Sociales, 2008). As we shall see, a number of other subdivisions also derived from the kingdom like the Musolongos, Batas and others.

[54] John Thornton, Africa and Africans in the Formation of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), for Cuba in particular, Matt Childs, ‘Recreating African Identities in Cuba', in The Black Urban Atlantic in the Era of the Slave Trade, eds. Jorge Cañizares-Esquerra, Matt Childs, and James Sidbury (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), pp. 85–100.

[55] Robert Jameson, Letters from Havana in the Year 1820 … (London: John Miller, 1821), pp. 20–2 (from letter II).

[56] Fernando Ortiz, Hampa Afro-Cubana. Los Negros Brujos (Havana: Liberia de F. Fé, 1906), pp. 81–5; and further developed in ‘Los Cabildos Afrocubanos', in Ensayos Etnograficos, eds. Miguel Barnet and Angel Fernández (Havana: Editoriales Sociales, 1984 [originally published 1921]), pp. 12–34; for a more recent statement based on more research, Matt Childs, The 1812 Aponte Rebellion and the Struggle Against Atlantic Slavery (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), pp. 209–45 and María del Carmen Barcia Zequeira, Andrés Rodríguez Reyes, and Milagros Niebla Delgado, Del cabildo de “nación” a la casa de santo (Havana: Fundación Fernando Ortiz, 2012).

[57] For example, the now famous community of Pindar del Rio, see Natalia Bolívar Arostegui, Ta Makuende Yaya y las Reglas de Palo Monte: Mayombe, brillumba, kimbisa, shamalongo (Havana: Ediciones UNION, 1998).

[58] Childs, Aponte Rebellion, pp. 209–12; Jane Landers, ‘Catholic Conspirators: Religious Rebels in Nineteenth Century Cuba', Slavery and Abolition 36 (2015): 495–520.

[59] Brown, Santería Enthroned, pp. 62–112; María del Carmen Barcia, Los ilustres apellidos: Negros en la Habana colonial (Havana: Oficina del Historiador de la Ciudad, 2008), pp. 45–151; Barcia, Rodríguez Reyes, and Niebla Delgado, Del Cabildo which carefully demolishes the earlier theses of Fernando Ortiz and others that the cabildos grew out of the brotherhoods.

[60] This group must have split or been replaced by another, for a property dispute in the Congos Loangos relates to their foundation in 1776, Archivo Nacional de Cuba (ANC) Escribanía Valerio-Ramirez (VR) legajo 698, no. 10.205.

[61] Barcia, Iustres Apellidos, pp. 45–151.

[62] Barcia, Ilustres Apellidos.

[63] del Carmen Barcia Zequeira, Rodríguez Reyes, and Niebla Delgado, Del cabildo, pp. 12–9.

[64] Fernando Ortiz, ‘Los Cabildos Afrocubanos', in Ensayos Etnograficos, eds. Miguel Barnet and Angel Fernández (Havana: Ediciones Ciencas Sociales, 1984 [originally published 1921]), p. 13, citing documents in El Curioso Americano, 1899, p. 73.

[65] Proclama que en un cabildo de negros congos de la ciudad de La Habana, prononció por su Presidente Rey Siliman Mofundi Siliman … (Havana: np, 1808); for the claim of superiority, drawn from an ambiguous statement that he was ‘more black that you others’, see Brown, Santería Enthroned, pp. 25–7 and 311, footnotes 4 and 6. For political context, see Ada Ferrer, Freedom's Mirror: Cuba and Haiti in the Age of Revolution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), pp. 247–9.

[66] Fredrika Bremer, Hemmen i den Nya Världen, 2nd ed., Vol. 3 (Stockholm: Tidens forläg, 1854), p. 142 (English translation as The Homes of the New World: Impressions of America, Vol. 2 (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1853), p. 322) Her host's name is given in the original and obscured in the translation as ‘C—'.

[67] Bremer, Hemmen, Vol. 3, pp. 146–8 (Homes Vol. 2, pp. 325–8).

[68] Henri Dumont, Antropologia y patologia comparadas de los Negros escalvos, 1876, trans. Israel Castellanos (Havana: Molina, 1922), p. 38.

[69] Bremer, Hemmen, Vol. 3, pp. 172–4 (Homes Vol. 2, pp. 348–9).

[70] Bremer, Hemmen, Vol. 3, p. 213 (Homes Vol. 2, p. 383).

[71] Esteban Pichardo, Diccionario provincial de voces Cubanas (Matanzas: Imprenta de la Real Marina, 1836), p. 72. Musundi may refer to Kongo's northern province of Nsundi, though the match is not exact since the nasal ‘n' is not incorporated into it, musundi might also mean ‘excellent', as the Virgin Mary was called ‘Musundi Madia' in the Kongo catechism meaning exactly this.

[72] It is possible that Bremer attended the dance of another Cabildo of Congos Reales, who were in the process of declaring their insolvency in 1851, ANC Escrabanía Joaquin Trujillo (JT) leg 84, no. 12, 1851; for a 1867 dispute, see the property case involving them in ANC VR leg. 393, no. 5875; other mentions of cabildos of this name including the group from 1865–1871 in Carmen Barcia, Ilustres apellidos, p. 408. For the 1880s mentions, see Archivio Historico de la Provincia de Matanzas (henceforward AHPM), Religiones Africanas, leg 1, no. 30, July 7, 1882; no. 65, January 9, 1898 and no. 31, July 31, 1886.

[73] Fondo Fernando Ortiz, Institute de Linguistica y Literatura, Havana, 5.

[74] ANC Escibanía d'Daumas (ED) leg 917, no. 6. (foliation uncertain, very deteriorated document).

[75] António de Oliveira de Cadornega, História das guerras angolanas (1680–81 ), eds. Matias de Delgado and da Cunha, Vol. 3 (Lisbon: Agência Geral do Ultramar, 1940–1942, reprinted 1972), p. 3, 193. In July 2011, I drove through all three dialect zones, confirmed some of the differences by hearing them spoken and by speaking with people about these differences. My thanks to Father Gabriele Bortolami, OFMCap for driving, interacting with people, impromptu language updates and occasional lessons in the etiquette of dialect use in northern Angola.

[76] Cherubino da Savona, ‘Breve ragguaglio del Congo … ’, fols. 41v–44v, published with original foliation marked in Carlo Toso, ed., ‘Relazioni inedite di P. Cherubino Cassinis da Savona sul ‘Regno del Congo e sue Missioni’, L'Italia Francescana 45 (1974): 135–214. The foliation of the original is also marked in the French translation, found in Jadin, ‘Aperçu de la situation au Congo … '

[77] ANC ED, leg 494, no. 1, fols 96–97. This text was included in papers dealing with another dispute in 1827–1828 and in 1832–1836.

[78] ANC ED, leg 548, no. 11, fol. 9–9v; José Pacheco, January 21, 1806; ANC ED, leg. 660, no. 8, fols. 1–4; Pedro José Santa Cruz (a request for its own capataz) 1806; for the later dispute ANC ED leg 494, no. 1.

[79] ANC ED, leg 660, no. 8, fol. 4.

[80] ANC JT, leg. 84, no. 13 passim, 1851.

[81] AHPM, Religiones Africanas, leg 1, no. 30, July 7, 1882.

[82] AHPM, Religiones Africanas, leg 1, no. 65, January 9, 1898.

[83] AHPM, Religiones Africanas, leg 1, no. 31, July 31, 1886.

[84] Brown, Santería Enthroned, pp. 55–61 and Barcia Zequeira, Rodríguez Reyes, and Delgado, Cabildo de nación.

[85] Childs, Aponte Rebellion, p. 112 and ‘Identity', p. 91.

[86] Consider the temporal range of inquisition cases cited in Tania Chappi, Demonios en La Habana: Episodios de la Inquisición en Cuba (Havana: Oficinia del Hisoriador de la Ciudad, 2001). For an example of the sort of persecution the Inquisition could do, and the sort of information that can be obtained from their records, see James Sweet's study of slave religious life in Brazil, Recreating Africa.

[87] Jameson, Letters, pp. 20–2.

[88] See the transcript of his interview published in Henry Lovejoy, ‘Old Oyo Influences on the Transformation of Lucumí Identity in Colonial Cuba' (PhD diss., UCLA, 2012), pp. 230–46.

[89] Aisha Finch, Rethinking Slave Rebellion in Cuba: La Escalera and the Insurgencies of 1841–44 (Chapel Hill: North Carolina Press, 2015), pp. 199–220. Finch attributes most of the activities in these cases to the non-Christian part of Kongo religion, or an early form of Palo Mayombe; see also Miguel Sabater, ‘La conspiración de La Escalera: Otra vuelta de la tuerca', Boletín del Archivo Nacional 12 (2000): 23–33 (with quotations from trial records).

[90] Bremer, Hemmen, Vol. 3, p. 213 (Homes Vol. 2, p. 383).

[91] Bremer, Hemmen, Vol. 3, pp. 211–3 (Homes Vol. 2, pp. 379–83).

[92] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 26, citing late eighteenth- and nineteenth-century sources.

[93] Abiel Abbott, Letters Written in the Interior of Cuba … (Boston, MA: Bowles and Dearborn, 1829), pp. 15–7.

[94] Cabrera did not employ any orthography of contemporary Kikongo in her day, but it is not at all difficult to recognize her ear for that language, which she did not speak, and most quotations she provided are readily intelligible.

[95] Institute de Linguistica y Literatura, Havana, Fondo Fernando Ortiz, 5. This list, written in a different hand than Ortiz’, one that was shakier with large letters, on fragile aged paper (perhaps school paper) was, I believe, compiled by a literate person who was a native speaker of the language, based on his use of Kikongo grammatical forms (use of verb conjugations and class concords in particular).

[96] Armin Schwegler, ‘On the (Sensational) Survival of Kikongo in Twentieth Century Cuba', Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages 15 (2000): 159–65; Jesús Fuentes Guerra, La Regla de Palo Monte: Un acercamiento a la Bantuidad Cubana (Havana: Iberoamericana Vervuert, 2012) (neither Schwegler nor Fuentes Guerra had access to Puyo's vocabulary in Ortiz’ documentation, the contention of its identity with Kikongo is my own). It seems likely that both Cabrera's and Ortiz’ vocabularies were collected probably from old native speakers, who entered Cuba at the end of the slave trade.

[97] For example, the class marker ki in the southern dialect is –ci in the north; use of ‘l' versus ‘d' would be another difference. The northern dialect is well attested in dictionaries of the French mission to Loango and Kakongo in the 1770s, compared with seventeenth- and nineteenth-century dictionaries of the southern dialects. I have also heard these differences myself in Angola.

[98] Fernando Ortiz, Hampa Afro-Cubana. Los Negros Esclavos (Havana: Bimestre Habana, 1916), pp. 25, 32 (clearly, testimony from the same informant).

[99] Ortiz, Negros Esclavos, p. 34. The term ‘Totila', clearly derived from the Kikongo ntotela meaning ‘king'. The word is first attested in the Kikongo dictionary of 1648, as meaning ‘King'. In 1901, King Pedro VI of Kongo, writing in Kikongo, styled himself ‘Ntinu Ntotela NeKongo' Archives of the Baptist Missionary Society (Regents’ Park College, Oxford) A 124 (both ntinu and ntotela can be glossed as ‘king').

[100] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 15.

[101] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 109. Cabrera, for her part, then told him of Nzinga a Nkuwu's baptism in 1491, presumably from one of the historical accounts she had read.

[102] On the assertions of Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita, see Thornton, Kongolese Saint Anthony; on the representation of Christ as an Kongolese, Fromont, Art of Conversion.

[103] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 93.

[104] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 58.

[105] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 59.

[106] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 14.

[107] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 19.

[108] The problem was apparent to Lydia Cabrera in her study of Palo, El Regla de Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe (Miami: Ediciones Universal, 1979), pp. 120–30, as one can see from the defensive tone of her informants, probably speaking with her post-1960 experience (this is not seen as a problem in her earlier publication, El Monte (Havana, 1954)).

[109] Cabrera, Vocabulario, p. 123.

[110] Cabrera, Monte, pp. 119–23 passim (here, often used in the context of witchcraft); Reglas de Congo, pp. 24–5. In W. Holman Bentley, Dictionary and Grammar of the Kongo Language (London: Kegan Paul, 1887), p. 361, which relates to the Kinsansala dialect (the most likely associated with Christianity) in the 1880s, mvumbi meant simply the corpse of a dead person; in the 1648 dictionary ‘spirits' was rendered as ‘mioio mia mvumbi' (or souls of corpses).

[111] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 24. In Kikongo, mvumbi means a corpse, the lifeless remains of a dead person, and the name of an ancestor would usually have been nkulu, though this usage would still make sense in Kikongo.

[112] See John Thornton, ‘Central African Names and African American Naming Patterns', William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd Series, 50 (1993): 727–42.

[113] The denunciation of the first tooth ceremony is only attested in the general complaints of the Capuchins in the 1650s, written by Serafino da Cortona.

[114] ‘Kisi malongo' appears to be ‘nkisi malongo'. A more likely way to say ‘the teaching of nkisi' would be ‘malongo ma nkisi', so the word order puzzles me. However, word order in Kikongo is flexible and should the speaker wish to emphasize the teaching spiritual part, it might be feasible to use this order.

[115] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 24. My translation of the phrase ‘nganga la musi' assumes that the speaker has only partial command of Kikongo grammar and would be ‘nganga a mu nsi' The same informant used the term kisi malongo, and perhaps as a Cuban-born person was not secure in the language.

[116] Cabrera, Regla de Congo, p. 23.

[117] Institute de Linguistica y Literatura, Havana, Fondo Fernando Ortiz, 5.

#The Kingdom of Kongo and Palo Mayombe: Reflections on an African-American Religion#Palo Mayombe#ATR#African Traditional Religions#Kongo#Reglas De congo#Nkisi#Kikongo

1 note

·

View note

Text

Whimsical Metaphors: Hans Hollein's Architectural Collages

The Vienna-based architectural magazine Bau: Magazine for Architecture and Urban Planning, during its transformative period between 1965 and 1970, represented a radical departure from conventional architectural discourse. Under the editorial leadership of influential figures like Hans Hollein, Walter Pichler, Günther Feuerstein, and Oswald Oberhuber, Bau became a platform for avant-garde ideas that transcended the boundaries of traditional architecture, delving into the realms of art and politics.

In the groundbreaking 1968 issue of Bau, Hans Hollein provocatively declared "Everything is Architecture," challenging the rigid confines of pre-war modernist architecture. This bold assertion sparked a paradigm shift, urging architects to reconsider their role in society and embrace a more holistic approach to design.

The magazine itself was a departure from the norm, resembling a glossy fashion publication rather than a conventional architectural journal. Its creative use of advertising and vibrant imagery, drawn from a diverse range of sources including art, urbanism, and popular culture, set it apart from its contemporaries.

One of Hollein's most iconic collages, depicting a traditional city juxtaposed with a towering high-rise made of Swiss cheese, epitomized this innovative spirit. In a contemporary reinterpretation, the Swiss cheese high-rise transforms into a square bar of Ritter Sport chocolate, with its corner playfully deconstructed and scattered throughout the city at a smaller scale.

The metaphorical link between modern architecture and Swiss holey cheese, and its whimsical replacement with chocolate, serves as a humorous commentary on our cultural predicament. It highlights the absurdity of rigid architectural conventions and celebrates the potential for creativity and playfulness in the built environment.

Today, as we navigate a world dominated by technological giants like Uber and Amazon, Hollein's assertion that "Everything is Architecture" takes on new meaning. Contemporary art and architecture have the power to comment on and critique our evolving cultural landscape, challenging us to rethink our assumptions and embrace innovation and diversity in all its forms.

In this light, the playful reinterpretation of architectural symbols becomes not only a source of amusement but also a catalyst for critical reflection. By subverting traditional notions of space and form, contemporary artists and architects invite us to question the status quo and imagine new possibilities for the future of our cities and society at large.

#WhimsicalMetaphors#HansHollein#ArchitecturalCollages#BauMagazine#ViennaArchitecture#EverythingIsArchitecture#ContemporaryArt#CulturalCommentary#HumorousAnalysis#architecture#berlin#area#london#acme#chicago#puzzle#edwin lutyens#massimoscolari#oma

0 notes

Text

Week 3: How does Tumblr function as a digital community?

Tumblr is not quite familiar when it comes to a popular social media platform to use with an average of over 200 million visits worldwide in the last six months of 2023 (Statista, 2024). However, it is still regarded as a great one to connect and form a community. This premiere post of mine will examine the whole progress of Tumblr ever since it's inception. 1. What is Tumblr? Tumblr, a popular microblogging network, has captivated millions with its distinct blend of creativity, self-expression, and community. In this essay, we'll look at the substance of Tumblr, including its features, purpose, and impact on digital culture. It was launched in 2007 as a social media platform that mixes blogging and social networking. It enables users to create and modify their own blogs, sharing a wide range of information including text articles, photographs, videos, and more. Tumblr, which focuses on short-form content and multimedia, invites people to express themselves visually appealingly. Tumblr flourishes as a creative hub, allowing people to share their unique perspectives and artistic achievements. Its user-friendly layout and adjustable themes allow users to curate their blogs, resulting in a more personalized digital presence. Academic research has emphasized Tumblr's importance in promoting self-expression and the exploration of various identities and subcultures. At its core, Tumblr is a flourishing online community. Users can use tags to find content that is relevant to their interests and interact with others who share those interests. The platform's reblogging function promotes community involvement by allowing users to share and highlight information from others while also providing their own commentary. This encourages the establishment of niche communities focused on fandoms, activism, and other interests. 2. Definition of a Digital Community: Digital communities have become a vital part of our online life, allowing people to connect, discuss, and engage with others who share their interests. In this essay, we will look at the essence of a digital community, including its definition and significance in our increasingly linked society. They are virtual environments where people can join and engage in activities related to their common interests or aspirations. These communities exist on a variety of online channels, including social media, forums, and specialist websites. They allow people to connect across geographical borders, instilling a sense of belonging and support. These communities shape our online experiences and identities. They promote teamwork, knowledge sharing, and emotional support. Research has highlighted the importance of digital communities in fields such as education, health, and activism, where individuals can collaborate to address common concerns and influence good change (Preece, 2001, pp. 347–356).

3. Why Tumblr is a Digital Community? Tumblr, the popular microblogging network, is thriving as a digital community. In this piece, we'll look at the features that distinguish Tumblr as an engaging digital community that promotes connectivity, self-expression, and creative inquiry. Tumblr's essence is in its capacity to bring people together and foster a feeling of community. Users can interact with each other's material by following, reblogging, and commenting, creating conversations and forming connections. Tumblr's participatory aspect distinguishes it from other blogging platforms, transforming it into a vibrant digital community. Tumblr provides a rich tapestry of self-expression, allowing users to share their ideas, emotions, and creative works in a variety of ways. Users can curate their blogs to reflect their distinct identities and interests, including visual art and written writing. This self-expression creates a thriving ecosystem of varied voices and ideas. Academic study has identified Tumblr as a digital community that empowers people and fosters a sense of belonging. According to research, Tumblr has an important role in promoting self-expression, assisting minority communities, and offering a forum for activism and social justice discourse. Finally, Tumblr is frequently linked to eccentric youth societies. It also provides a particularly comfortable environment for trans and gender varied self-representation when contrasted to mainstream platforms such as Facebook and Instagram… Although Facebook is a source of support for transgender people, its design promotes a single user identity, which can be unpleasant for many trans or gender nonconforming individuals. Facebook's "default publicness" has also been recognized as harmful to many LGBT youths of color (Byron et.al, 2019). References: Statista. (2024). Worldwide Visits to Tumblr.com from July to December 2023 [Review of Worldwide Visits to Tumblr.com from July to December 2023]. Preece, J. (2001). Sociability and usability in online communities: determining and measuring success (pp. 347–356) [Review of Sociability and usability in online communities: determining and measuring success]. Byron, P., Brady Robards, B. Hanckel, S. Vivienne, B. Churchill (2019). ' “Hey, I’m Having These Experiences”: Tumblr Use and Young People’s Queer (Dis)connections', International Journal of Communication 13 (2019), pp. 2239-2259.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Metal Children Signs: A Reflection of Childhood and Art

In the realm of artistic expression, metal children signs stand as a unique intersection of nostalgia, creativity, and social commentary. These signs, often found in urban and suburban settings, depict children in various activities, captured in the durable medium of metal. This article explores the significance of metal children signs in art and society, delving into their history, artistic value, and the messages they convey.

The Origin and Evolution of Metal Children Signs

Metal children signs originated as a practical response to the need for caution in areas where children play. Typically seen near schools, parks, and residential areas, these signs serve a dual purpose: ensuring the safety of children and alerting drivers to their presence. Over time, however, artists and communities began to see these signs not just as functional objects but as canvases for artistic expression.

In many cases, the original 'Children at Play' signs were transformed into works of art, embellished with vibrant colors, intricate designs, or whimsical elements that reflect the playfulness of childhood. This transformation marked a shift in perception, turning a mundane object into a medium for creativity and a focal point for community identity.

Artistic Value and Styles

The artistic value of metal children signs lies in their ability to capture the essence of childhood in a static yet dynamic form. Artists who work with these signs often incorporate elements of street art, pop art, or folk art, creating pieces that are both visually striking and emotionally resonant.

Some artists choose to maintain the simplicity of the original signs, emphasizing the silhouette of a child in motion. Others add detailed features, such as facial expressions, clothing, or accessories, to bring the figures to life. The use of bright colors and bold lines is common, creating a contrast with the typically grey or black metal background.

Themes and Messages

Metal children signs often carry deeper meanings and messages beyond their visual appeal. One prevalent theme is the innocence and freedom of childhood, symbolized by the carefree play depicted on the signs. This theme resonates with viewers, evoking nostalgia and a longing for simpler times.

Another common message is the importance of community and the role of children within it. By placing these signs in public spaces, artists and community members make a statement about the value they place on children's safety and well-being.

Furthermore, some artists use metal children signs to comment on social issues, such as the impact of urbanization on childhood, the loss of play spaces, or the challenges faced by children in different parts of the world. These signs become a powerful tool for raising awareness and sparking conversations about important topics.

Impact and Reception