#also both men and women are capable of sexualizing or objectifying female characters

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I find myself growing a bit tired of the take that 'we need female mangakas because they won't oversexualize women/they can write female characters well/etc" firstly, it reduces women's art to the exclusively wholesome, which is just factually incorrect, but more importantly: we need female mangakas because women make great fucking art and shouldn't be pushed out of the industry because of misogyny. It's that easy. We don't need a specific thing that ~only women can do well~ for it to be wrong that the industry is so sexist. If every single male mangaka started writing female characters like they've been studying feminist literature for 20 years we'd still need female mangakas.

#misogyny#manga#manga industry#feminism#also both men and women are capable of sexualizing or objectifying female characters#the fact that this has become the NORM for female characters is because of misogyny.#but that doesn't equal to 'when woman sexy = misogyny'#i am once again asking everyone to stop applying demographic/systemic problems to individual cases. it doesn't work like that#in the same vein as 'bury your gays' being a homophobic trend does not equal every gay tragedy being homophobic#every instance of a female character having sex or being portrayed sexually is not misogyny. you have to ZOOM OUT. and LOOK AT TRENDS.#and FAR MORE IMPORTANT THAN FAKE CHARACTERS IS THAT REAL WOMEN ARE NOT BEING VALUED AND PAID ENOUGH FOR THEIR WORK

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Neil Gaiman thing is not shocking to anyone who has read any of his adult books.

I already knew he was a misogynist. I already knew he was one of those men who identify as “nerds” and see women as a distinct and lesser species of human, a man for whom women are sexual objects rather than thinking, feeling people. He told me in his books.

The way he writes women is uncomfortable to say the least. His female characters (I am thinking here of Neverwhere’s Door and Hunter, and Good Omens’ Anathema) are highly sexualised in a way that makes them objects rather than agents. They are also portrayed as less emotional, or less emotionally vulnerable than Gaiman’s male protagonists, as experiencing sex and abuse in a detached way, and as capable of enduring and compartmentalising violent abuse & sexual abuse in a way that male characters cannot because they do not have the same kind of internal emotional life that male characters do. They feel less and therefore it is less significant when they are hurt. They feel less and therefore when they have sex it is not because they want to but because they perceive that they are wanted by male characters. Anathema’s sexual availability to Newt & Door’s sexual availibility to Richard are unsettling to read because both women feel pity or compassion rather than liking and desire for the male protagonist, and the female characters bestow themselves as objects upon the male characters to reward their character growth. The male protagonist constantly fixates on the ways in which female characters are sexually attractive, constantly, constantly objectifies them. Sometimes an author writes a character who is a pervert, but Gaiman’s everyman seems to be a pervert disinterested in the thoughts and feelings of women.

That all said, it’s awful to discover that he actually perpetrated violence against women, and I am heartbroken for those women and afraid of how they will be treated by Gaiman’s fans, male and female, who will not want their idol tarnished.

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sexuality In Neon Genesis Evangelion: Adolescence & Violence

(I’m literally 20 years late to the party here, but if anyone still cares for NGE metas, this hasn’t left me alone...!)

It takes only a few episodes into NGE to sense there’s some form of unrest beneath its surface. A palpable sense of unease and malcontent shadows the characters, seeping into the bleak cityscapes and following Shinji’s listless drift from one battle to the next - creating the unrelenting sense that this show has no intention to coddle or comfort you. Much will not be explained, or even directly addressed. Most of that unease you’re feeling as a viewer will be left for you yourself to decipher – probably in a manner uncomfortably and bracingly personal. I would call this a mark of artistry, in that the viewing experience becomes something deeply intimate and unique from person to person.

The obvious narrative explanation for all this dark ambiguity is the evocation of Shinji’s troubled psychological state. He mopes in his dark bedroom, rides the train alone with his headphones in and no destination, and accepts the role of Eva pilot only when his refusal would make him feel yet more despised. He is utterly directionless and thus helpless – caught in a paralysis between his pathological need for external affirmation and his crippling fear of being hurt. He craves kindness and care from others, but is both unwilling and unable to forge such positive connections with others because he presupposes doing so will cause pain. Therefore, he makes few self-motivated choices and rebukes all notion of the driven, intentional protagonist.

Shinji’s rejection of the traditional mantle of the hero’s journey, and his repeated regression into unassertive self-hatred also signals an unorthodox approach to storytelling - where the narrative flows around the inhibited, apathetic characters rather than through them. We as the viewers do not become invested in the narrative progression as an extension of Shinji’s own investment. Rather, a central part of the narrative becomes the self-aware exploration of its own impact upon Shinji and the wider cast of characters. Shinji, Rei, Asuka, and to a certain degree Misato and Ritsuko, do not determine the narrative direction through their own choices and thereby set events in motion; they are instead passive, reactionary presences drawn along by the provocations of seemingly inevitable series of events. (Angels attack – characters respond; Gendo or Seele give some unexplained order – characters react; Instrumentality begins – Shinji reacts)

As the curtain is finally drawn back from the human instrumentality project in the show’s final act, we realize Shinji was not simply whiny or poorly-written: His constant struggle between the fear of pain and need for intimacy is in fact the defining tension of the show as a whole. The “Hedgehog’s Dilemma.” This dilemma saturates each character’s personal trauma, fears, and desires, and finally elevates the characters’ internal reckoning in the face of instrumentality to create the show’s climax.

The show’s indirect yet masterful depiction of Shinji’s depression and undefined malaise is, in fact, keenly intentional and central to the story’s purpose. In a show defined by endlessly rich even if agonizing ambiguities and a narrative style that reveals itself only in subtlety, no minor detail is inconsequential. And so, I repeatedly found myself trying to discern the purpose of a recurring element that could be neither accidental nor innocuous. I am referring now to the show’s consistent and blatant preoccupation with the sexualization of its (female) characters and the infusion of sexuality into inter-character relationships.

The sexualizing and/or objectifying gaze is applied far too often to be anything but an intentional layer generating narrative meaning. In a show that elegantly weaves together psychological, religious, ethical, and technological allusions to construct a cutting inspection of the human psyche, this preoccupation is not a mere trope or “fanservice.” The recurrent reference to characters’ sexuality and their depiction as sexual objects cannot be a neutral or peripheral element of narrative meaning. Beyond the impossibility of this element being unintentional or divorced from the show’s narrative purpose, we are also obliged to make ourselves aware of the gendered lens through which this depiction of sexuality is filtered, and the power balance or imbalance this depiction enforces upon the characters involved. Consistent nudity to the point of fetishism and sexual inferences to the point of defining character cease to be superficial and become something pernicious.

Below, I will explore two different frameworks through which to interpret the show’s sexual overtones. The first framework – adolescence and the fear of adulthood – aligns with my initial response to the anime, while the second framework – sexual violence –reflects my more troubled response to the End of Evangelion film.

Framework 1: Shinji’s Adolescent Fears of Adulthood and Intimacy

Lest we forget, Shinji is only the tender age of 14. His internal struggle with self-worth and identity is exacerbated by its intersection with puberty and Shinji’s fraught understanding of his own budding sexuality. Shinji’s characterization of being highly dependent on the guidance and praise of his elders highlights both his adolescence and his own inability to confront his growth to adulthood. His unwillingness to navigate the perils of adulthood (as well as its corresponding sexual relationships) is probably evoked most clearly in his Episode 18 conversation with Kaji. After Kaji opines on men and women’s inability to understand each other – let alone themselves – Shinji merely replies dismissively, “I don’t understand adults at all.”

Given his 14-year-old perception of adulthood as something impenetrably mystical, it follows that his own budding sexuality acts as both a source of anxiety and a central aspect of his journey through adolescence. The often discussed parallels between Shinji’s relationship with Asuka and Misato’s relationship with Kaji further cements sex as something firmly belonging to adulthood; just as Asuka’s eagerness to present herself as sexually mature reflects her desire to appear independent and “grown.”

Coming to terms with one’s sexuality is of course a commonplace metaphor for the development from adolescence to adulthood. However, the characters’ understanding and comfort with their own sexualities also plays a key role in their internal reckonings and decisions which occur within instrumentality.

During his moments of metaphysical introspection, Shinji’s confrontation with his deepest fears repeatedly presents itself in the form of sexual temptation. We see him translate this need for external validation into unconscious sexualization and desire for the women around him. While fused with Unit 1 in Episode 20, Shinji is questioned by imagined specters of Misato, Rei, and Asuka. He reaches his breaking point when, after admitting he only pilots the Eva in hope of earning others’ praise, he cries out for someone to take care of him. After pleading, “someone be kind to me,” all three women appear to him naked, asking repeatedly, “Don’t you want to become one with me? In body and in soul?” In this imagined ordeal of self-examination, Shinji’s deepest, most fundamental need for approval and warmth from others is coded into the prospect of understanding and intimacy associated with sex. At a subconscious level, he perceives the offering of sexual union as the highest form of acceptance. Shinji therefore feels varying degrees of conflicted, guilt-ridden desire for the women around him, in the most primal form of his craving for acceptance.

In this scene, the offering of sexual intercourse is also a direct foreshadowing to the prospect of union with all during instrumentality, and either the acceptance or rejection of that union. In End of Evangelion, Shinji’s crucial choice during instrumentality is again presented in the same terms: Asuka, Rei, and Misato’s voices all asking “Do you want to become one with me, body and soul?” Shinji’s mix of attraction and repellence (for he fears intimacy as intensely as he craves it) when confronting this question indirectly depicts his struggle to decide between a solitary but self-defined existence, and the sacrifice of his autonomous self to total union. Thus, Shinji’s repressed desire for sexual intimacy becomes in and of itself a key facet of both his decision to ultimately reject instrumentality, and his conclusive creation of an independent and capable identity.

In line with my earlier reference to Asuka’s desire to appear sexually mature, the anime consistently uses sexuality as a means of revealing character - often probing at characters’ deepest vulnerabilities. Misato is likely the most direct example. It is through her sexual relationship with Kaji that she confronts her conflicted feelings towards her father and their profound impact on her. During instrumentality, she also admits she enjoys sex as an escape mechanism from pain and a way to prove she’s alive. She seems to perceive sex in the opposite perspective from Shinji – who on some level finds it threatening. This could be attributed firstly to Misato’s maturity in age and correlating comfort with her own sexuality. Secondly, this speaks to the show’s use of sexuality to build character in ways beyond Shinji’s troubled adolescent shame. The show’s focus on its characters’ sexuality can therefore be viewed as a means of prying into the inner conflicts they each seek to hide from the world. Note it is also through the reveal of Ritsuko’s sexual involvement with Gendo that we understand the reasons for her troubled relationship with her mother, her dedication to NERV, and her knowledge of its secrets.

Though sexuality is used as a sometimes literal, sometimes symbolic, but often effective vehicle to portray abstract concepts and internal, non-physical conflicts, this does not fully explain or justify the show’s gratuitous use of the male gaze. Though the depiction of sexuality often serves the purpose of character development, this depiction is exceedingly gendered. Though Shinji is shown naked, his nudity serves comedic effect (when he runs out from the bathroom in Misato’s apartment in Episode 2) or appears highly stylized (embracing Rei’s equally naked form in End of Evangelion). By contrast, Rei and Asuka’s bodies practically serve as set pieces. The pilot suits and contrived “camera” angles incessantly present their bodies as aesthetic objects for consumption.

Furthermore, early appearances by both female characters immediately define them as objects of sexual focus. The first time she appears, Asuka tells off Toji for looking up her skirt; Shinji ends up sprawled on top of Rei when she’s naked while first trying to get to know her in Episode 5. If we apply the interpretive framework of sexuality as a means of navigating adolescence, then it is exclusively Shinji’s journey towards adulthood with which the show shares its perspective and identification. It would therefore follow that Rei and Asuka serve merely as signposts or attractive obstacles along the path of Shinji’s development. Their bodies are exploited as tools through which to challenge and probe at Shinji’s psyche. While Shinji’s sexuality bestows him personhood and agency, Asuka and Rei’s often seem to do the opposite – instead reducing them to only the means towards Shinji’s end. Yet, even the justification that Rei and Asuka’s objectification may serve Shinji’s character development falls short, given that the girls are still depicted in a lewd and hyper-sexualized lens even when there’s nobody but us, the viewers, around to witness.

Using sexuality as a key vehicle to convey the male protagonist’s psychology creates an inherently gendered narrative – one in which a male protagonist acts out his conflict upon female bodies. This uneven and highly exploitative depiction warps what might have been an adolescent journey of self-discovery and growth into something far less constructive and much more unsettling.

Framework 2: Pervasive References to Sexual Violence

As I argued previously, Shinji’s repressed and conflicted sexuality can be viewed as a mirror of his character-defining struggle between the desire for love and the fear of pain. In this case, Shinji’s exploration and acceptance of his own sexuality becomes in and of itself a central element of his character development and, by extension, the show’s narrative resolution as a whole, given that the outcome of instrumentality rests on Shinji’s shoulders alone. It then becomes crucial that Shinji actualize his latent desire for sexual intimacy and ultimately master his own sexuality – as the chief expression of his internal development towards accepting his relationships with others and the co-dependent process of creating his own identity, self-worth, and reality.

In the abstract, this idea seems relatively healthy. However, the “Don’t you want to become one with me?” scenes and essentially all of End of Evangelion left me with a distinctly uncomfortable impression that couldn’t have been more different from that of a guileless adolescent navigating puberty. Seeing the “Don’t you want to become one with me?” question repeated to Shinji in the End of Evangelion context made me circle around one key question: Why is this imagined physical offering by the women in Shinji’s life presented as temptation? Why does the timing of this sequence reappear while Shinji is experiencing instrumentality? Or rather, why is the experience of instrumentality itself presented with the air of sexual temptation or seduction? This all culminates into the depiction of sexual desire for the female body as something needing to be tamed or conquered – given that it is only through Shinji’s repudiation of these offerings that he ultimately also rejects instrumentality. This supposition implies an adversarial relationship between Shinji and the object(s) of his sexual desire. This implicit hostility paints sexuality now as a struggle for control and/or dominance, rather than a source of self-discovery and growth.

I’ll note now that most of the observations and criticisms explored in this section speak almost exclusively to End of Evangelion. In my view, this implied hostility embedded into the exploration of sexuality is much more present in the film, whereas the show largely maintains sexuality as a means of fumbling adolescent growth and complex characterization. To frame what might be seen as an extreme interpretation, I’ll begin my closer reading of End of Evangelion with this Catharine MacKinnon quote:

“Once the veil is lifted, once relations between the sexes are seen as power relations, it becomes impossible to see as simply unintented, well-intentioned, or innocent the actions through which women are told every day what is expected and when they have crossed some line.”

The crucial dynamic supporting this darker interpretive framework – a dynamic much more palpable in End of Evangelion – is power relations. Referring back to my previous point wherein the persistent objectification of Asuka and Rei undermines their personhood to the same degree that it enhances Shinji’s – End of Evangelion takes this imbalance still further. Rei and Asuka’s sexualization not only serves Shinji’s development, but becomes the main stage upon which Shinji’s fight for self-determination plays out. This is to say that Shinji’s actions and key elements of the film’s narrative as a whole are acted out upon women’s bodies as both battleground and symbol. End of Evangelion resorts to a mode of storytelling that is explicitly gendered, portraying its conflict through a starkly male lens. Through the film’s imagery, brutality, and indulgence in the explicit, Shinji’s narrative is acted out through the depiction of women’s bodies as objects either with destructive power or being destroyed themselves; and as threats which much be conquered.

The Shinji we see in End of Evangelion experiences highs and lows far more extreme than his anime counterpart. EoE Shinji is shockingly depraved, powerless, and violent – in that order. His experiences in relation to the navigation of his sexuality take on a tone of violence and aggression. If he cannot act out his sexual impulses – if he cannot subdue the tormenting yet desired female body to the point that satisfies his desires (even if not always sexual in nature) – he resorts to violence to assert his will. During the kitchen scene within instrumentality, it is at the point when Asuka coldly rebuffs his pleading for her help that he first strangles her. Thinking back to the above quote re power relations – is this the “line” beyond accepted behavior where Asuka becomes deserving of male violence?

Violence takes many forms – all of them an embodiment of power relations. Yes, Shinji masturbating over Asuka’s stripped, unconscious form in the first scene is unequivocally an act of violence. No matter how “fucked up” and past sense Shinji may have been in that moment, he is still a man demeaning a woman and taking pleasure from the act – her inability to consent and even her comatose state all fueling male sexual gratification. Aside from the considerable shock value, this scene sets the tone of Shinji’s actions towards women throughout the film as relations of power and dominance. This scene further establishes repressed sexual desire and thwarted sexual frustration as the latent foundation of Shinji’s interactions with Asuka throughout the film; thus creating motivation and tension with the potential to drive him to further forms of violence.

In EoE, Shinji shares some type of sexual experience with all three women to whom he’s closest. First, his repulsive descent into depravity at the film’s very start. In this moment when he’s at his lowest, it is his most base and yet powerful instinct that takes over. He exacts pleasure, comfort, and distraction from Asuka’s body despite its fleetingness and her lack of consent. Second, Misato realizes that physical intimacy is the only thing that will get through to Shinji in his shell-shocked state. With a heated kiss, she delivers on the show’s hints of sexual interest between the two. Demonstrating just how well she understands Shinji, she promises him “We’ll do the rest when you get back,” knowing the promise of this ultimate physical act of approval and care is likely the only thing he will fight for. To put this in blunt terms: Shinji is promised sexual access to a woman whose praise he values, and this prospect of sexual fulfillment is what motivates him to finally enter Unit 1. While he isn’t imposing dominance over Misato here the same way he did to Asuka, this keeps with the film’s overall gendered perspective wherein Shinji’s triumphs or rare moments of purpose are marked by his access to women’s bodies.

Third, Shinji’s interactions with Rei/Rei-Lilith within instrumentality. It first must be noted that Rei is depicted naked for practically the whole movie. Sure, this might be necessary for the initiation of instrumentality, but it also serves to complete her objectification. I can by no means see it as mere coincidence that the advent of instrumentality and potential unleashing of the cataclysmic Third Impact is all represented by a giant, naked female form. What would be the greatest threat from the perspective of the male-gendered narrative? Precisely this – a female body that is overpowering, unconquerable, and unfathomable. By extension, I also don’t believe it’s coincidental that Shinji’s attainment of self-determination in his decision to reject instrumentality happens concurrently to his sexual union with Rei. She explains to him that no, he hasn’t died, “everything has just been joined into one.” This “joining” is depicted utterly literally, without any of the subtlety by which the anime presented sexuality as representative of total union within instrumentality. Thus, the resolution of Shinji’s character arc and the film’s climax as a whole occurs when Shinji finally attains fulfillment of the sexual desire he has harbored since the film’s beginning. The following shot of him and Rei naked with his head in her lap resolves the crisis of instrumentality with an unmistakable post-coital essence.

After these three encounters, we have the much-debated final scene of Shinji reuniting with Asuka after emerging from instrumentality. By this point, Shinji has taken advantage of her comatose body and strangled her, but she still has not shown herself amenable to his sexual desires as Misato and Rei have. She remains beyond his ability to either control or dominate. And so, while Rei’s giant, naked, and broken (read: conquered) body rests in pieces behind them, Shinji asserts his newfound will to attack the woman who has resisted his desire and refused the gratification he sought – both physically and emotionally.

This scene left me possibly even more disturbed than the film’s opening. To me, this ending implies that along with Shinji’s discovery of self-determination comes the male’s unfettered triumph following a struggle defined by sexual violence. In this final scene, we see the resistant woman subject to yet more violence at the hands of the protagonist – until at last, she no longer resists. In my view, this final scene was the occasion of Asuka’s capitulation. She is finally subdued to the point of acceptance and affectionate response even when being subjected to violence. She responds to Shinji’s aggression not with retaliation, but with a loving gesture. Her final words of “how disgusting” reminded me immediately of the hospital scene, and what Shinji had asked of her there: “Wake up, help me, call me an idiot like always.” Now, the man’s desire is at last satiated.

Beyond the narrative reliance on sexuality as a form of power relations, EoE also engages in gratuitous degradation of female bodies. They are either imbued with threatening, destructive power (Rei-Lilith), or experience destruction themselves (Asuka in Unit 2 and Rei-Lilith at the film’s end). Both Rei and Asuka’s bodies are subjected to extreme violence throughout the film, even while still being depicted as sexual objects. While suffering horrific, graphic injuries during her fight in Unit 2, Asuka is depicted writhing in agony in the entry plug with a disturbing sense of the erotic. After her body becomes the apocalyptic vehicle of instrumentality, Rei’s giant naked form is depicted crumbling to earth, stripped not only of her clothes but any sense of the human. Her split-open head rests beside the sea of LCL – a symbol of the male protagonist’s moral and psychological “victory.”

Framework 2: Counter-Arguments

Though I was disturbed by the rampant and dehumanizing sexualization in EoE, there were also plenty elements of the film I admired and remain deeply fascinated by. I don’t wish to seem overly disparaging, so I’ll briefly mention two counter-examples to this more critical framework.

1. Rei denying and rebuking Gendo and asserting her own will, while depicted as naked. It’s hard to overstate the enormity of Rei’s decision here. After existing as a seemingly unfeeling clone created for the purpose of realizing Gendo’s desires, Rei brings his plans to a crashing halt right at the pinnacle moment. The scene metaphorically traveled from 0-100 very quickly. It began with the insinuation of Gendo joining with Rei in a vaguely sexual sense, and his hand sinking into her breast in an unconventional bodily invasion while she showed discomfort. But then she asserts, “I am not your doll.” Her nakedness seems transformed from vulnerability to power. She is no longer the passive instrument of a man’s realization of his desires. Instead, she asserts her personhood and makes the individual decision how to employ the power within her. In so doing, she decides not only her own fate, but practically that of the whole world.

2. Shinji and Kaworu’s dynamic could be seen as refuting a binary reading of gendered power relations. Taking Shinji for bisexual has the potential to revise my interpretation from ‘Shinji subconsciously desires sexual access and control over women’ to ‘Shinji subconsciously desires sex and control’ period, without the emphasis on women as the subjects of his struggle. If this gendered binary is removed, then his growth and self-actualization need not come at the expense of the female characters around him. Extending Shinji’s repressed sexuality to encompass desire for Kaworu also alleviates the connotations of dominance and confrontation embedded within heterosexual sexuality.

Writing all this out was largely my personal means of resolving the million jumbled thoughts in my head after finally diving into this stunning masterpiece of a show. I’ll say again - what makes this show such a timeless work of brilliance is its highly personal resonance in the minds of its viewers. In the end, it isn’t a story about robots, aliens, or even sex at all – it’s a self-reflective act forcing you to wake up and confront your own role in creating the very reality in which you live. What kind of world have you made for yourself? Have you trapped yourself in confinement of your own making, or have you imagined every possible version of your world and liberated all the possibilities hidden in your creation of self? Evangelion can mean something different to every one, and no single interpretation is more correct than any others. So that said – a hearty thank you to anyone who actually read all the way here, and I’m always eager for discussion! :)

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

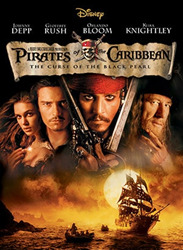

Pirates of the Caribbean essay – representation, genre

For this essay I will be analysing the Disney franchise Pirates of the Caribbean with how the representation of women is portrayed in a modern/ more openminded world and how the genre of pirates re-in surged due to these films. The Pirates of the Caribbean first originated as a ride of the same name in Disneyland in 1967 with inspirations from the 1952 film The Crimson Pirate. This ride later became inspiration for a film that becomes a box office success Pirates of the Caribbean the Curse of the Black Pearl (2003) which has spanned 4 more very successful films and a multitude of games. Representation is the depiction of a thing, person or idea and can be from any source like written, spoken or performed. This can be used to create a realistic depiction or can be adapted to create more of an abstract or perverse depiction. Genre is a style or category of art, music or literature that involves a particular set of characteristics.

(Pirates of the Caribbean Poster, Disney)

The representation of women within the world of Pirates of the Caribbean is complicated as the films are aimed to appeal to everyone and carry on the progressive ways but to also reinforce the integrity and social contexts of the era and world of pirates. The ride although loved by many has had lots of adjustments made to it by toning it down and reducing the extreme inappropriateness/ sexualization towards women. The era of piracy was a very misogynistic time where women were not valued much at all with many being represented in media and films of pirates as working in brothels along with other representations of women such as them bringing bad luck on a ship and accusations of witchcraft. In the first 3 films most, women were either servants or harlots, so the focus and representation for women is one of the main characters, Elizabeth Swann the governor’s daughter a very strong and emotional women. These films also include the character Tia Dalma (Calypso) the goddess of the sea who is also represented as a strong and emotional character with both being very much in love.

The small number of female characters in the films has them be regularly objectified and made out to be inferior to the men but all the films have both sides of it with the men being sexist and misogynistic to the women being flirty and manipulative to get what they want.

Elizabeth Swann is very much a strong independent woman who goes against her ‘duty’ of being a high-class lady and lives a dangerous fun life which she has wanted by being very interested and knowledgeable of pirates. Although she is very independent and capable her character is also very much infatuated with Will Turner and is a big part of her motivations and journey. In Pirates of the Caribbean At Worlds End (2007) Elizabeth ends up becoming the king of the brethren, which is the highest title for all the pirates, and this really represents the character of Elizabeth as she has a very strong leadership role and handles pressure with ease but the journey on getting to that point was very much a male dominated one.

(Keira Knightley, At Worlds End)

Calypso is a very mysterious character in the films who is very strong and independent living alone, but her characters story is very much another way of making man seem superior as she was the almighty goddess of the sea when she fell in love and was betrayed by the one, she loves, and man captured her and bound her with little to no power.

The film Pirates of the Caribbean On Stranger Tides (2011) which is heavily inspired by a novel of the same name by Tim Powers in 1987 has a leading role of Angelica the daughter of Blackbeard who is a very skilled pirate with great sword fighting skills and a master of disguise and deception. As every female role in Pirates of the Caribbean she is fuelled by love and it is a big part of her as a character, she is sown as being tough but also caring she not only had a previously had a relationship with Captain Jack Sparrow but is hellbent on finding the fountain of use and is trying to save/redeem her father’s soul.

Lastly, the newest Pirates of the Caribbean Dead Men Tell No Tales (2017) has a leading female role which is different from all the other films and instead of being a fearsome fighter/pirate it is Carina Smyth the abandoned daughter of Captain Barbossa and is very smart being an astronomer and horologist. This leading female role is the one who is sexualized the most out of all the films and is directly objectified and made to seem inferior to men, this is done by making lots of remarks laughing at her and not taking her seriously because she is a woman. There is lots of crude jokes and sexism throughout the film and this approach really made the audience dislike the film with lots of negative reviews and most of them about the sexism in the film.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hgeu5rhoxxY

(Dead Men Tell No Tales trailer, YouTube)

The Pirates of the Caribbean reignited the pirate genre as the last pirate film that was released was not successful called Cutthroat Island (1995). The pirate genre before was very much made to appeal towards men but Pirates of the Caribbean appeals to all genders with a one of the main characters being a female as well. The Curse of The Black Pearl was a very good combination of different genres to make the masterpiece that it is with the action, romance, adventure, comedy, and fantasy it could be argued that it can also be supernatural ass it deals with curses and the undead whilst making scenes scary but with all that they mix it forms the perfect concoction for an amazing movie. Another genre which Pirates of The Caribbean fits perfectly into is Swashbuckler. A Swashbuckler film is a subgenre of action which primarily includes sword fighting and adventurous heroic characters, the main characteristic of a Swashbuckler is to be well trained with a sword and to have a very straight code of honour. This element is not entirely applicable to Pirates of The Caribbean or Captain Jack Sparrow as they go by the “pirate code” which the characters go against all the time and sometimes only care about themselves.

(Johnny Depp, At Worlds End)

The reason I chose to have the case study be Pirates of the Caribbean was because I loved the films when I was growing up due to the amazing characters, the adventures, the spectacular battle/ action scenes and the lore with the mythical creatures. I had lots of figures, toys and games which I would play with constantly and even the outfit of Captain Jack Sparrow as he seemed cool when I was young because he did whatever he wanted without a care, everything always worked out and he was a very witty comical guy. As I grew up and watched the movies again, I could appreciate the complex emotional side of the storytelling and the action scenes still look spectacular. Though Analysing Pirates of the Caribbean and the representation of women within it I was shocked to discover how bad it was with the ride and the films but what shocked me the most was how it seemed to go in a step backwards with Dead Men Tell No Tales with lots of sexism directly pushed out for ‘comedy’. This has made me really think about how far women have come and the change in way they are perceived and represented in tv and film but there are still films being made which are not socially acceptable now how they were and that it is not right.

In conclusion The Pirates of The Caribbean (excluding Dead Men Tell No Tales) has done a good job on maintaining the integrity of the pirate genre and era whilst also representing the main women as strong independent women for the modernisation of the older genre to appeal to current audiences. This being said there is still a large amount of sexism in the films but the representation of the women are that of positives not showing any generic old stereotypes of what women should do.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Question: does Quark ever actually really articulate hatred for women or belief in their inferiority or does that impression just arise from the combination of him constantly hitting on the women around him and objectifying the women who work for him, plus him expressing the belief that Ferengi women should adhere to certain very strict laws and social norms because that’s Just The Ferengi Way?

Because I don’t think it’s necessarily the same thing. Like, if he actually hates women, but is into getting kicked around by women, then that’s just a fetish and it is in no way redeeming. (Plenty of men like that in real life.)

But in his love-interest-of-the-week episodes, Quark actually seems interested in these women as people? He risks his life to help Grilka gain political and financial freedom and then asks for a divorce. I think he doesn’t see that as a violation of his Ferengi values because she’s not Ferengi. It seems that Ferengi have no clear-cut taboos about interacting romantically/sexually with other species (maybe it’s all too new), so he feels freer there. He can be best friend with Jadzia Dax and invite her to play Tongo with him. (And while other Ferengi are shown sometimes griping about losing to a female, I’m pretty sure we never actually hear him say anything like that about it.)

The only (canonical) Ferengi love interest he has is Pel, who he seems to disagree with on like, political-bordering-on-religious grounds, because he’s a traditionalist. But he still acknowledges that she is as smart and capable as him. And in the end, he takes a financial loss to protect her from legal repercussions even though he doesn’t want to pursue a relationship with her. He can’t pursue a relationship because it is taboo. Not because he actually hates women. And it’s taboo in a way that goes deeper than just social stigma. (”No one would have to know,” says Pel. “I’d know,” says Quark.) He’s afraid of crossing a hard line that will mean he’s abandoned traditional Ferengi values. (Don’t get me wrong; those particular values are Fucked and he needs to grow a backbone and resolve the cognitive dissonance he’s ignoring to see that. But I think people can become invested in holding onto value systems that don’t actually resonate with them or even contradict their selves.)

That he never stops flirting is another issue. But if you compare some of his scenes with some of Julian’s (particularly seasons 1 and 2 with, any women really, but you can specifically compare with Dax), they’re actually... not that different in that regard. Both characters can be read as just shameless flirts who do that by default; it’s just how their misguided way of trying to connect with people because they’re always dtf. But they’re also both always back off easily with a, “Yeah, I know, it’s really just a reflex and a joke at this point” kind of attitude.

I can’t believe I said this many words about this, but uhhh... I did.

Quark whenever he’s not the main focus of an episode: I hate women so much it’s unreal

Quark whenever he has a love interest of the week:

#quark#long post#hoo boy i'm sorry lol#i'm too invested in liking this character#like. i DO know he's terrible but uhhhh i like to think he's complicatedly terrible

759 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blade Runner 2049 or Do Androids Dream of Gender Equality?

Just a heads up, this is a long one, turns out I have opinions-a-plenty about this one. Blade Runner 2049 did a slightly better job of representing women than its predecessor, although in the original none of the female characters are human women and the only way that any of them make it out alive is in the arms of Harrison Ford. There are twice as many named female characters in this film as compared to the original, but that’s going by the credits, I’m pretty sure one is only called “Madam” on screen and I don’t know if we ever hear the replicant prostitute’s name aloud. Also, all the women have basically a terrible time, so there’s that.

*Blade Runner 2049 spoilers follow*

Let’s start with the sole female survivor from the first film, Rachel (Sean Young in flashbacks to the original, Loren Peta as a stand in). In her first appearance she is absent from any portrayal of herself as a character - she is an anonymous skeleton, dug up in a box and examined as evidence. Later, she appears as a ghost, another replicant designed to trick Deckard (Harrison Ford) into thinking Rachel has returned. However, the imposter is a pale imitation, easily seen through and she is discarded. Rachel does not inhabit this film, she haunts it, and all of her spectres are filed or thrown away. Perhaps as the sole female replicant to possess reproductive capabilities, she was too powerful to be allowed to live. The whole purpose of having synthetic women as sexual partners is that they are disposable and guilt-free, but the possibility of conception leads to consequences. Furthermore, the ability to create life is a uniquely female power that has been stolen and commercialised by men in this universe. If Rachel can create life herself, she renders her own creator useless. Therefore she must not simply be killed but destroyed, she is erased from this story altogether.

Another woman denied control of her own story is Joi (Ana de Armas). Joi is the holographic girlfriend of K (Ryan Gosling), a replicant. She is an artificial man’s projection of what he imagines a woman to be like, without any kind of tangible body to call her own. The extent to which she even exists as any kind of character is therefore debatable. It would be different if she was an artificial intelligence, a truly sentient and unique personality, however it is strongly suggested that she’s simply a program. Adverts for Joi litter the cityscape, proclaiming that she can be, “whatever you want”. What K seems to want is a 1950s housewife to bring him burgers, as this is how we are introduced to Joi. Every action she takes is to serve K; from insisting to go on the lam with him even though she could cease to exist, just to the police can’t extract any data from her, to hiring a prostitute to overlay herself onto so that K can pretend to have sex with her. I had so many problems with this. Firstly, this implies that women are so homogenous that you can pick any two and layer them on top of each other, it’ll be fine because apparently they’re all the exact same size and shape. It’s as though there’s just one paper doll template for all women in this world - which as these two have actually been manufactured, there might be, but there’s a huge variation in the physiology of the male replicants that we see. Additionally, Joi dismisses the prostitute, Mariette (Mackenzie Davis), by saying, “I’m done with you”, seemingly trying to emphasise that Joi is using Mariette. A woman taking advantage of a woman isn’t any better than a man doing so - is it possible for women just not to be exploited at all?

In addition to Mariette, whose name I’m not sure we even hear during the film, there are two other named female replicants; Freysa (Hiam Abbass) and Luv (Sylvia Hocks). Luv has vastly more screen time and is portrayed as capable in a variety of ways - she hosts a business meeting, flies an aircraft, pries open enormous metal doors with her bare hands and fights excellently in hand-to-hand combat. However, personality-wise, she is lacking. She seems to act as as proxy to her creator Wallace (Jared Leto). She parrots his beliefs, or one half of them anyway, as Wallace switches regularly between referring to replicants as “slaves” and “angels”, his motivations are hard to follow. She believes in replicant superiority, but other than that, she comes across as a process - a means to an end, action without any personal drive or thought behind it. The canonical excuse that replicants have been programmed to obey, and so she cannot deviate from her course to explore her character, doesn’t hold up, as K is allowed plenty of room to soul search and follow his own agenda. Furthermore, if she is made to blindly follow Wallace, why does she always look so uncomfortable when being scrutinised by him? We see her visibly flinch from his sensor bots. She is allowed only enough independence from her rail-road destiny to remind us that she is a subjugated female.

Freysa is the other prominent replicant female. She is the leader of the replicant resistance, she looks middle-aged, appears to have a spider-web network of connections and agents and therefore presumably plenty of power. Freysa seems amazing, but we see her for all of five minutes so I can’t really make much more of a judgement than that.

One final, unnamed replicant female exists in Blade Runner 2049, and she has possibly the worst deal out of everyone. We witness her birth, a private and vulnerable moment, followed by the rest of her very short life. She is squeezed, undignified and naked, from a plastic packet onto the floor, where she lies shivering and struggling for breath. There she is touched up by Wallace, who proceeds to literally wash his hands of her whilst studying her from every angle using a multitude of drones. Next, he caresses her belly, describing her womb absolutely disgustingly as, “that barren pasture, empty and salted”, before slicing her open and then, like the rotten cherry on the worst cake of all time, kissing her. I think we all get that he built an empire on literally objectifying women and subjecting them to slavery, did we need this violent reminder?

Blade Runner 2049 breaks away from the original by introducing a human woman, Lieutenant Joshi (Robin Wright), however I’m fairly certain that she’s only referred to as “Madam” in the film. Despite being human, she - like K - is robbed of a name for no real reason. She cannot simply exist as a police chief, we have to be constantly reminded, through language, that she’s a woman, despite the visual fact of her being a woman doing a pretty good job of that anyway. Is this in search of a pat on the back for having two middle-aged female characters? Whilst that is a positive, I would also like female characters to have a name and the military rank they have presumably worked hard to earn. On top of this, her death felt completely pointless. “Do what you’ve got to do” have to be the most passive last words ever. Given the little we know about Joshi - that she has a military career and huge power within the police - it makes no sense for her not to put up a fight.

So, we’ve had holograms, replicants and humans, but there is a third category of women in this film. Dr. Ana Stelline (Carla Juri) is the daughter of a replicant mother and human father, so we are unsure of her exact biological make up. What we do know, however, is that she’s basically the replicant messiah, so it’s laudable to see a woman occupy that position. However, you guessed it, everything else in her life is pretty terrible. She has a broken immune system and so lives alone in a sparse, hermetically sealed bubble, where she makes the happy memories for replicants that she never had herself. Carla seems to be a good person - she wants to give replicants a better life, even if only in their minds.

If everyone in Blade Runner 2049 is having an awful time, not just the women, then at least we can say it’s a fairly egalitarian experience. However, K has a good job and his dream girlfriend, yes he loses both of those but Joi and his boss actually die so I think it’s safe to say they have the worse end of that. People have to actually shout abuse at K, which I believe only happens twice, to remind us that he’s a second class citizen, otherwise he seems to be living a fairly normal life. Before we meet Deckard, his ex-colleague Gaff (Edward James Olmos) makes it clear that his main aim in life is to be left alone, which he achieves for most of the film, living seemingly comfortably in an abandoned but nevertheless somewhat luxurious Las Vegas casino. he does endure undeniable physical and emotional hardships after being captured, he’s taunted with the spectre of his dead love and almost drowns, but the film ends with him being reunited with his daughter and the prospect of rebuilding a family.

Overall, Blade Runner 2049 is better than the original as far as the representation of women goes, if only because there are more of them and they don’t all die. However, they are still having pretty much the worst time and are undeniably subject to the whims of men - they are girlfriends, prostitutes, slaves. Those who exist independently from men, such as Joshi, don’t make it out alive. Freysa is the exception to this, but we see so little of her and know hardly anything about her; she possesses power but is not allowed the screen time to display it. Ana is the real tragedy of this film, as she is the embodiment of hope for an emancipating revolution, but is doomed to live the rest of her life trapped and isolated. No woman is allowed to truly be free.

And now for some asides:

Rachel has the most amazing and recognisable silhouette, it’s a brilliant piece of design that I didn’t fully appreciate in the original.

The costume detail was amazing - K had salt lines on his trousers after he came out of the sea. Touches like that are what made this film so gorgeous to look at.

Booze is not for doggos, harrison Ford.

#blade runner#blade runner 2049#spoilers#blade runner 2049 spoilers#movie review#film review#feminism#cw: sex#tw: violence#tw: murder#sci-fi#science fiction#mothermaidenclone#ryan gosling#harrison ford#jared leto#ana de armas#carla juri#sylvia hocks#robin wright#hiam abbass

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

But part of why Wonder Woman is good is because they're female. While they didn't choose to be female, it's not something you can erase from their existences either. They're great artists, but they also have grown up with female experiences and that saturates their world views, their perspectives, and all the work that they do. Who better to show the story of a woman than another woman when so, so many women's stories are told by men with a male perspective? That's why them being women matters

The fact of the matter is, seeing promo posters where Gal isn’t a tiny-waisted photoshopped woman? Seeing the movie with no shots that prioritize beautifying her body over the plot that’s being told and the realism of how a body movies? Seeing a plot where a woman is both strong AND feminine? That’s something that comes from a female perspective. If not, then it wouldn’t be the norm to have the opposite in male directed and managed movies. You may not notice those little things consciously

I do notice those things actually. I didn’t used to, but since I’ve gotten more involved in writing and directing through being a theatre major, I’ve been trained to notice the implications of details because those details are almost always added consciously. And those things that you mentioned are awesome and really important! Yes, they’re seen more often when coming from a female perspective, but male directors are fully capable of including them too. Male directors don’t have to to sexualize, objectify, and misrepresent their female characters, they choose to. We shouldn’t be holding male directors to a lower standard.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reflection Essay

Since the advent of the feminist movement in the early 1960s, women have made significant progress in workforce participation, and tremendous growth has been achieved in the demystification of some of society’s most pervasive stereotypes. Despite these gains, they remain woefully underrepresented in some traditionally male-dominated occupations. For instance, top levels of the U.S. corporate sector management comprise a diminutive number of female chief executive officers (CEOs), Chief Financial Officers (CFOs), or senior board management members. A similar situation exists in the European continent and most countries around the world. Regrettably, the dearth of women at the upper echelons of organizational management persists despite increasing evidence revealing that women have the prerequisite skills, experience, and educational qualifications for upward mobility in the proverbial corporate ladder. One of the central impediments to women’s workforce career advancement is the high prevalence of gender biases that are deeply entrenched in gender stereotypes. Even more concerning is that the stereotypical perceptions traverse the workforce setting and manifest in how society understands and treats women in other aspects of life. Oftentimes, stereotypical generalizations apply to individual group members for the simple reason that they belong to a particular group, and the stereotypes about women comprise generalized attributes and perspectives that impact them negatively. The overarching objective in this paper is to reflect on both descriptive and prescriptive stereotypes about women in life and the workforce.

Throughout human history, society has developed prescriptive stereotypes about women that designate how women are and how they should behave, dress, maintain their bodies, or relate with other people. These stereotypes function as injunctive norms that dictate the attributes and behaviors considered appropriate or inappropriate for women. In most cases, women who deviate from stereotypical gender prescriptions experience backlash from society. Given that these typecasts are perceived to function as norms, violative them can attract consequences, such as negativity and social disapproval. Some of the most common examples of penalties imposed on the women who fail to exhibit stereotypically prescribed attributes in the workplace include lower pay, fewer recommendations for rewards or promotions, and hostile treatment. At the same time, society considers the women who break from these established stereotypes as cold-hearted, interpersonally hostile, or less feminist. For example, Muslim women who do not conform with traditions, such as wearing the hijab, are cast as rebellious by their societies. On the other hand, those who conform to this religious tradition are misconstrued by society based on different stereotypes. For instance, Dalia Mogahed highlights some of the pigeon-holes ascribed to Muslim women dressed in a hijab. In her TEDTalk, she challenges some of these typecasts by posing rhetorical questions about some of the most prevalent perceptions that people associate with Muslim women. The speaker asks the audience: “what do you think when you look at me? A woman of faith? An expert? Brainwashed, a terrorist or just an airport security line delay?” (Mogahed). These potent questions reflect the underlying theme of stereotyping highlighted in the commonplace book of the first part of this assignment.

Stereotypes represent negative connotations attributed to specific groups of people in society. Some of them can have adverse implications on the targeted individuals and imperil the prospects of having peaceful coexistence. In retrospect to Mogahed’s powerful talk, stereotypes can be polarizing. She identifies the media as one of the principal perpetrators pushing the misguided perceptions about Muslims and women. The speaker backs her argument by stating that “80 percent of news coverage about Islam and Muslims is negative” (Mogahed). Given the widespread influence of the media in public opinion, there is a high likelihood that the mainstream media has played a significant role in the marginalization of women from different cultural and religious groups.

Each day, millions of women worldwide are subjected to different forms of judgment or microaggression because of their clothing. For example, Muslim women dressed in the veil or the burqa are conceived in different ways by society due to some of the stereotypes associated with their garment design. However, these misconceptions arise from various historical and cross-cultural intersectionality. Abu-Lughod (599) argues that Afghan women were subjected to a mandatory obligation to wear the burqa by the Taliban and other extremist groups in the Middle East. This historical aspect has changed the global perception of Muslim women dressed in the hijab and long overflowing dresses as oppressed people. However, it is surprising that long after the liberation of Afghanistan from the Taliban, the women continue to uphold their tradition of wearing burqas. Contrary to popular stereotypes, the Taliban are not the inventors of the burqa; instead, it is part of a long-standing traditional heritage among the Pashtun women and other ethnic groups in Southwest Asia. The burqa symbolizes modesty and respectability. However, the prevalence of terrorist groups in the Middle East region and the anti-Muslim rhetoric perpetrated by the media have completely transformed people’s perception of this dress.

Anthropological studies reveal that people dress according to the conventions in their social communities’ socially accepted standards, moral ideals, and religious beliefs unless there are other extenuating circumstances, such as inability to afford proper cover or a deliberate intention to make a point. For example, women in Western culture have been acculturated to a world of choice regarding the type of clothing they wear. However, it is imperative to acknowledge that other traditions uphold a different perspective on fashion. These differences should be appreciated as part of diversity rather than a symbol of oppression, terrorism, or lack of expression. Incidents, such as the 9/11 attacks on the United States, dramatically changed people’s perceptions about Islam. As a result, a female dressed in a hijab can be automatically perceived as an extremist as showcased in the commonplace book. While this misperception is utterly wrong, there are numerous examples where women who choose to dress based on their choices and freedom are taken less seriously by society. In some cases, women with less coverage on their bodies can be objectified by men. This trend creates a vicious cycle whereby every type of clothing elicits different kinds of meaning. Stereotypes also misguide people to overlook the core aspects of an individual’s character and personality. These prejudices can have negative implications on the way people address or relate with each other.

The existence of the sexual division of labor is also one of the core antecedents of stereotyping in society. Frequently, this phenomenon is perceived as proof of the oppression of women in the workplace setting. However, this stereotypical misconception arises from the confusion between the descriptive and prescriptive explanations of the concept of the sexual division of labor (Mohanty 76). The author explicates this misperception by using one of the most common contemporary changes in the family structure within the United States and Latin America. The rise of female-headed households in middle-class U.S. households has been misconstrued to indicate women’s progress and independence in society. Additionally, there are increasing family settings with lesbian parents who have been successful in raising their children without men's intervention. Contrastingly, single-parent families in Latin America where women have historically had more decision-making power been only predominant among those members living in the most impoverished strata of society. In this regard, the decision for single-parenthood is not attributable to independence; rather it is a result of the life choices that people who have been most constrained economically have to make. The rise of female-headed families among the Black and Chicana women can also be explained by a similar argument. With that said, the rise of female-headed households in the United States and Latin America cannot be misconstrued to mean women’s independence. Therefore, there must be a socio-historical context in place before making conclusive judgment for the rise of female-headed families. Simultaneously, the universal subjugation of women in the workplace setting cannot be explained through the concept of the sexual division of labor. Using this line of argument to explain the subpar treatment of women in the workplace setting can only serve a useful purpose if applied through an in-depth contextual analysis. Making generalized assumptions that sexual division of labor is responsible for the stereotypes against women in the workplace can create a false sense of the ubiquity of oppressions and struggles that women experience globally.

The prevalence of stereotype-based performance expectations can also affect the type of information that is focused upon when evaluating women’s performance in their professional duties. Notably, expectations can act as a perpetual filter that directs attention away from the disconfirming information toward information that is consistent with stereotyped expectations. Besides, when evaluators discover information that challenges their expectations about women’s performance capabilities at the workplace, they might fail to integrate such information into the final impression that is formed. This trend can jeopardize the chances of giving women a fair consideration when it comes to critical aspects of career advancement, such as promotion into senior managerial positions. Besides, when expectation-inconsistent results are either disregarded or attributed to something outside the person under performance evaluation, then the original expectations can go without being challenged. As a result, the stereotypes can be maintained despite evidence that proves the contrary. Most women have been victims of stereotype-based performance expectations in the workplace setting. These practices put them at an exacerbated risk of stagnation in low-paying job positions despite having relevant competence as their male counterparts. It is imperative to acknowledge that women are not the only losers due to stereotyping; organizations also forego a chance to effectively utilize their human resources due to their tendency to perceive women with prejudice.

Overall, different types of stereotypes can elicit negative behavior and unacceptable practices in the way women are treated by society. Given that these typecasts traverse different sectors in life and in the workforce, women have been subjected to unjust treatment based on dressing, body shape, and biased expectations in workplace performance. The status of women in the professional and other aspects of life continues to be fraught with gender stereotypes. Nonetheless, there is a sign for cautious optimism given the increasing awareness about the negative ramifications of typecasts and some of the countermeasures to minimize them.

Works Cited

Abu-Lughod, Lila. “Do Muslim Women Really Need Saving?” In Women, War and Peace. 2002.

Mogahed, Dalia. “What it's like to be Muslim in America.” TED. 2016, www.ted.com/talks/dalia_mogahed_what_it_s_like_to_be_muslim_in_america?utm_campaign=tedspread&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=tedcomshare. Accessed 28 Jul. 2020.

Mohanty, Chandra. “Under the Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses.” Feminist Review, vol. 1, no. 30, 1988, pp. 60-82.

0 notes

Text

Tynnea Lynch

620091513

- Gender representation: the way in which the male and female bodies are presented, idealized and commoditized by society, specifically by Mainstream media in films, television, advertising and so on.

- Gender stereotyping: the roles and duties that have been projected onto males and females, as well as, the limitations of these roles and duties that go in accordance with a person’s gender.

- Gender roles: behaviors and attitudes society deems acceptable based upon a person’s sex or sexuality, whether it is actual or perceived.

If you choose to look at this through the perspective of animation, you will find both gender representation and stereotyping to be rampant in cartoons and animated films. In terms of gender representation, females tend to be depicted as objects of desire in animation or as a supporting/background characters; always in need of saving, showing zero skills in anything outside of cooking and cleaning, looks held in high regard, bodies sometimes given unrealistic proportions, mannerisms bordering on the submissive or overly submissive and clothing bordering on scantily clad, just to name a few.

One only has to look back at some of the classic Disney princess movies seen on FreeForm (previously known as abc family) and Disney channel to see how women were placed on a sort of pedestal as trophies for men or how little they provided to a story, besides being used as a political means, needing rescuing and looking pretty. These female characters are then merchandised and used to buy female children into the idea of what it means to be female and feminine. They grow up thinking that being like these Disney princesses is all that defines them and what is expected of their lives; stay home, cook and clean, look pretty, stay silent, do as they are told, let the men do everything. The males in these animated films are always depicted as strong, good looking, possessing a skill or more than one, rescuing a damsel and taking her as his prize/trophy. Males grow up learning that all that matters is that they are physically attractive, that girls should be pretty and that they can achieve anything by just being strong or manly. It is with characters like these that we start to give gender roles and start to stereotype males and females based off of whatever representation that mainstream media has given us.

It is also prevalent in Japanese animation (Anime), both past and present, where females take on supporting and submissive roles due to the expectation of their gender and the patriarchal stance of their society. There are anime that have a female protagonist, who is anything but a protagonist, being overwhelmed by male characters and pushed to the side as nothing but a pretty toy waiting to be objectified. One such anime is called Diabolik Lovers; a vampire romance based off of the game version of it.

The characters are stereotyped to the point that it is cliché. The female is depicted as fragile, pretty, naïve and submissive. The males are so domineering that it borders on abusive, despite all their pretty looks, and pervasive. There is also the fact that they happily claim ownership over her without a care for her feelings and thoughts, yet the female stays despite all of this (I do believe they call this Stockholm Syndrome). This is not a show meant for children, obviously, but that doesn’t stop them from seeing it or something similar and taking after the characters in terms of behavior and attitude.

Thankfully, things started to change. Now we have animated films with strong female characters who are capable of taking care of themselves, speaking up for themselves, taking charge and learning to be who they want to be and not who they are expected to be; Disney’s Mulan was a very good example of the clash that happens between being who you want to be versus being who you are expected to be. We now have male characters that can step back and give their female counterparts a chance to shine. Mainstream media now needs female characters that can stand alone (like Merida from Pixar’s Brave) and male characters (like Hiccup from Dreamworks’ How To Train Your Dragon) to show that males do not need to be defined by what society considers masculine to prove his masculinity or himself.

https://fourthreefilm.com/2015/09/looking-from-the-outside-in-gender-representation-in-animation/

http://mediasmarts.ca/gender-representation/men-and-masculinity/how-media-define-masculinity

https://moniquewaldman.atavist.com/feminine-gender-roles-in-anime

WMW-Jamaica (2010) Whose perspective: Gender Analysis of Media Content, Kingston, Jamaica

0 notes

Text

Women in Videogames

I’ll admit that Lara Croft was one of my favorite female action figures while I was growing up. Though I wasn’t aware that Angelina Jolie’s character in the movie Tombraider was actually based on the video game, I was completely taken by her. She was sexy but also really capable and cool. She was inarguably beautiful, but she was also smart, clever, and had the ability to fight all the bad guys by herself. She was someone I wanted to be and the first female action heroine that I could really think of back then. But as I’ve grown to be a little more aware and educated, I can see that there is controversy over the way Lara is portrayed. For instance, does it really make sense for someone running through a jungle to be wearing a skin-tight tank top and short-shorts? Why does her character need to have such giant and breasts?

Maja Mikula in her piece about gender and video games discusses the complexities of Lara Croft and whether or not she is viewed as a positive or negative role model for women who are constantly being excluded from the gaming world. According to Mikula, “Lara is everything that is bad about representations of women in culture, and I everything good” (80). While she is often considered to be a “badass”, it is not question that the design of her character has catered to the minds and desires of men. Her character throughout the years has gone through a series of changes but consistently she is portrayed with large breasts, a slim waist, and overall thin figure. But nonetheless, unlike many other video games, she is the female protagonist of the video game that drives the plot of the story. But can both men and women relate to her? According to Mikula, “...research suggests that the very idea of “identifying” with a character is a gendered one...the process of identification is more important for female gamers, who tend to become “irritated” when they cannot identify with their female character” (81). It also seems as though men who play this video game don’t view Lara as someone to identify with, but as someone who is an object under their control. Rather than viewing her as an extension of themselves navigating the story, they view her as someone to protect through the dangers in the game. But still, I think that there is something to be said that there is still an appeal for men to play this game because it is not common for female characters to be the driving aspect of a video game (even if much of the appeal is her attractiveness or the level of violence in the game).

While Lara’s character might fight traditional ideas of sexism through her independence and competence, she is still objectified and sexualized; her character is complex. Like Mikula says, “She is indeed a sex object; she is indeed a positive image and a role model; and many things in between” (85). I personally don’t know if any female video game character will ever completely appease both genders but I hope to see one that does some day in my lifetime!

0 notes

Text

Gender

There is not really a debate when it comes to gender roles in the media. As Rosalind Gill points out in “Postfeminist Media Culture,” “[women’s] femininity is defined as a bodily property rather than a social, structural, or psychological one.” Females are portrayed normally with their appearance and sexuality at the forefront and anything else they have to offer being portrayed as secondary. As I am following the accounts of three Game of Thrones fan pages, and Game of Thrones being in the film/television realm, I think it is important to mention The Bechdel Test. The fact that a test like this even exists is a testament to how women are portrayed in media and film. It works like this: in order for a film or television show to pass The Bechdel Test, two female characters who are important enough to the story to have a name and a purpose have to have a conversation about something other than a man or men. It is truly shocking how many films don’t pass the test. Media and film really are male-centered.

Game of Thrones is an interesting show to observe accounts on when discussing gender. I have heard several people who have not seen the show or have seen a few episodes brand the show as “misogynistic” or as “objectifying women,” with little else to offer besides sex, boobs and blood. I find this ironic. Game of Thrones definitely has its fair share of sex and nudity, however, it also offers a plethora of strong women. Not just sidekicks, either. Daenarys Targaryen and Cersei Lannister are two of the most important characters in the series, equal to the two male leads in their importance—Jon Snow and Tyrion Lannister. And although both have had sex on the show and shown their bodies (although, Cersei for non-sexual purposes), it doesn’t define either of their characters. These are just the two female leads. Olenna Tyrell is, in my opinion, more fierce and independent as any man, and Yara (Asha in the books) Greyjoy is a great example of postfeminist culture being represented in media, however not exactly how Gill points out, not that she’s wrong. Yara is the epitome of a woman feeling empowered to explore her sexuality, but not in a way that say Carrie Bradshaw from Sex and the City does—it is not central to her character. Yara is a powerful, intelligent woman, who in many ways is more important than and influential to the men around her. Her sexual nature comes secondary to her. When discussing self-surveillance and self-monitoring, we are essentially talking about women working within constraints and censoring themselves and their personalities for the sake of what is expected of them, usually by other men. Well, when something is natural, like sex, we should also not shy away from it, or censor it for the sake of character development. Game of Thrones is honest. And Yara is a sexual person. It is in no way the postfeminist trick that is being played elsewhere, where we are being led to believe it’s empowering, but it is really disguised objectification. One of the pages I am following, “winter-is-coming.net,” posted an article that mentions sex and The Bechdel test. Apparently only 18 of the 67 episodes pass the test. However, the article’s author, as well as I, disagree with this. The Bechdel Test’s standards are vague, and as I said before, Game of Thrones is an honest show. To censor men out of conversations for the sake of doing so is offensive. Instead, the test should measure in what context women are talking about men. In season six, Cersei and Olenna have a conversation that is difficult to forget. A famous line from it is Olenna’s when she tells Cersei, “I wonder if you’re the worst person I’ve ever met. At a certain age, it’s difficult to tell.” But because The High Sparrow and King Tommen are mentioned, this episode does not pass the test, even though it features two women in stronger positions and with more pivotal and complex roles than The High Sparrow or Tommen.

Many of these pages are guilty of taking Game of Thrones and creating beauty contests out of the female characters in memes—asking viewers to rate which one is the hottest. A perfect example of femininity as a bodily property. However, the three I chose to follow don’t seem to post things like this. My three accounts reflect the integrity of the show. Women are strong, and it’s not ever questioned or brought to attention that these female roles might not be normal. The way George RR Martin wrote his women must be indicative to how he views them—as human beings, capable of as much as any man. I would like to see more of this in the media. There is no effort to objectify women. If it’s there, it is because it is organic or necessary to the character (for example, one of Littlefinger’s prostitutes). That does not mean, however, that commenters can’t resort to these lows. Oddly enough, this has happened most recently with a male character, although, Gill does mention men face something similar with masculinity. We, as viewers, just met Rhaegar Targaryen for the first time. As Daenarys’ brother and Jon Snow’s father, he is an important, albeit dead, character and many people had an idea of what they wanted Rhaegar to look like. He ended up looking like Viserys, only less scrawny. To book readers, this made sense. Viserys envied his older brother and wanted to look just like him, but viewers who had not read the books commented frequently about how disappointed they were in Rhaegar. They wanted a gorgeous, brooding man with long blonde hair and sexy armor. There are even several memes about it. Before this assignment was even brought to my attention, I had compared the way people speak about Rhaegar to the way women are treated everyday in all forms of media, and let’s face it, real life.

In "Virtual Feminisms," Keller speaks about girls taking a stand, getting involved in political and feminist discussions. It is interesting to me that it's something that needs encouraging. This should be normal. In Game of Thrones, women are in the thick of politics. As bloody as GoT is, it truly empowers women in an honest way. It's too bad we can't show it to our children just yet. We have a difficult line to decide which side to be on. On the one hand, bring this postfeminist culture to light and discuss it till our tongues bleed, or on the other hand, just let be what is natural and normal be and stop subscribing to magazines, shows, films, etc, that perpetuate this gender-gapped culture. If only that were as easy as it sounds.

0 notes

Text

Hana O’Neill Dr. Rothenbeck English 2270 May 1, 2017 Mental Illness Related to Gender Roles in The Bell Jar and “The Yellow Wallpaper”