#also apparently geordi holding his hand out towards the camera. i have like three other geordi drawings where hes doing that. shrugs

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

more of these guys ( + one deanna)

#star trek#star trek the next generation#tng#geordi la forge#data soong#data tng#daforge#tangentially. to a degree.#deanna troi#fan#2024#first and 2nd to last page are reffed from screenshots the rest are just whatever#i thnk the very first one where data's smiling might be from a blooper . unsure#I LOVE DRAWING DATA IN PROFILE!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!#also apparently geordi holding his hand out towards the camera. i have like three other geordi drawings where hes doing that. shrugs#queue#WHAT WHY WAS THIS POSTED TODAY ok whatever thats fine. thought i scheduled it for tomorrow but so be it#edit took 2 drawings out bc i didn’t like them actually. he would not look like that (<— said to myself)

210 notes

·

View notes

Text

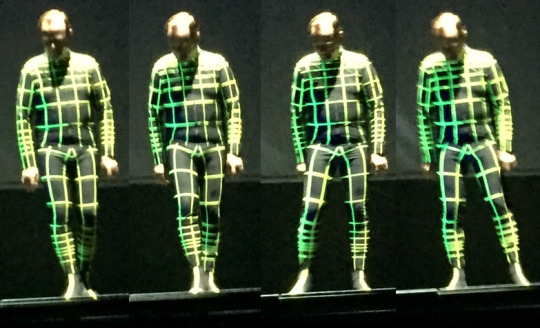

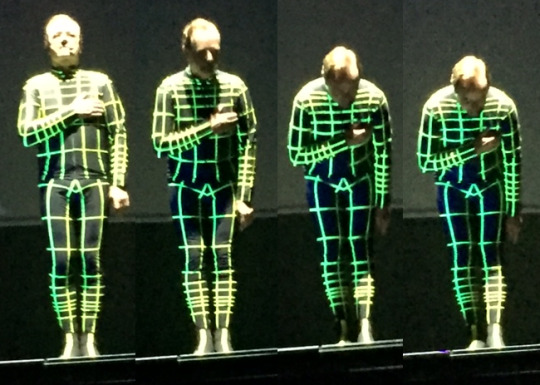

Kraftwerk - Royal Albert Hall 21/06/2017

Kraftwerk are my favourite band. Their performance was spectacular. So why does this long-term fan have such mixed emotions about the whole thing?

It's an impossible gamble, going to see a band you've loved for 25+ years but never seen live. I don't just love Kraftwerk; Kraftwerk are like a way of life to me. With so much weight of love and expectations, how can four aging human beings be anything but a mild anticlimax?

Anticlimax feels like the wrong word for such a triumphant, spectacular show. In every sense, Kraftwerk embody perfection: perfect pop melodies, perfectly shimmering minimal-maximal arrangements, perfect integration of music, lyrical text and graphic imagery for an emotionally overwhelming experience. But that's just it. I was expecting to be overwhelmed. Other friends described crying in their seats. I felt excitement, arousal, sentimentality, amusement, wonder, and on the rare occasion, even faint ennui. But I was not overwhelmed, and I had expected to be.

The Royal Albert Hall is a beautiful venue, built with the very best of high Victorian acoustic sound design. Kraftwerk have a reputation for getting absolutely pristine sound quality in the most unexpected of places, concrete bunkers, glass art galleries, turbine halls, so this should not have been a problem. The sound design itself was astonishingly beautiful, the three-dimensional aspects of their electronic "sound-paintings" as spatial journeys, with fast German cars and express trains and spacelabs that genuinely seemed to whiz about one's ears in physical space, thanks to speakers above, to the sides, and even behind the audience. And yet where I was expecting perfect sound, I instead had a very annoying imperfection. The huge booming sub-bass, the hallmark of Kraftwerk's groundbreaking electronic sound, was distorted and harsh, where it should have been warm and oceanic. With the expectation of “perfect”, merely good feels like a disappointment.

And the 3D visuals themselves, I'm afraid, were not a success for me. I often have this problem with 3D imagery and Virtual Reality (there are studies to show that this is a phenomenon whose experience varies greatly with one's sex) that it makes me feel dizzy and unwell with a sensation like motion sickness. I used the 3D glasses for a couple of performances where it seemed churlish not to: Autobahn, with its racing cars; and Spacelab, where Kraftwerk showed off both their stunning sense of the sublime with satellite views and the romance of interplanetary travel, and also their subtle German humour. The films depicted Kraftwerk as interplanetary visitors, flying their probe over specially programmed local landmarks - the Geordies got the Tyne bridge, we got the Houses of Parliament - before landing at the venue. Kraftwerk’s gestures towards locality have been hugely popular in other cities, but provoked a mixed response at the RAH. Before the gig, chatting with other fans, I asked how far they had travelled. London gigs are by their nature hugely cosmopolitan; it turned out the man on my left had flown in from Zurich, while the man on my right was Italian. When I said I was from Streatham, the two men in front of me turned around and proudly told me that they were, too. When London appeared on the Spacelab’s viewfinder, a huge cheer went up from the Streathamites; our neighbours were understandably nonplussed.

With the glasses, the projections seemed so tangible, I reached out a hand to stop the Spacelab’s antennae poking my eyes out, but it was impossible for me to use them for more than a minute or two at a time without feeling sick. I suppose it was good for me as a listener, as it forced me to concentrate on the musicians, though I know this is the opposite of what the band intend. The point of Kraftwerk has, since the days of The Man Machine, been to erase the individual, to create four identical units behind their workstations. And yet watching the players from so close (I was in the third row) the most enchanting details were the highly personal ones. Even the way they stand is revealing. Falk on the far right stands very erect, his shoulders braced, the posture of a man avoiding backstrain, using a workstation designed for people about four inches shorter than him. Tiny Fritz beside him, stretches to change the settings on his controllers, while Henning and Ralf slouch far more naturally.

It's the moments when the Musikarbeiters reveal themselves as fallible, and therefore most human that are always the most delightful. Ralf flubs the final chord at the end of Airwaves, emits an audible "ach!" then slams his elbows down on the keyboard in a dramatic musical fart. He is naturally very shy, and barely speaks to the audience at all, so the moment at the end of Tour de France, where his excitement overcomes him, and he announces with gleeful boyish enthusiasm, that Le Tour is coming to Düsseldorf, provides an intimate glimpse into a very warm and human Ralf. It's a common criticism that Kraftwerk play "with the showmanship of four old men checking their email onstage" but the moment that a younger, impossibly beautiful and perfectly still Ralf appears in a 70s-era video for Radioactivity projected above the elderly Ralf's head, it's clear that their Kabuki stillness has always been an aesthetic choice.

And close up, the moments of intimate connection with their machines and with each other become far more apparent. Henning is a very physical player, he grasps his filter sweeps and seems to twist them with his whole body, contorting his legs until the splay of his knees matches the funk of his bass. During Chrono, Henning and Fritz demonstrate some impressively choreographed simultaneous leg-bends. Ralf taps an incessant beat with his right knee, and has particularly unquiet hands. He often plays a melody with his right hand, while adjusting a control with his left, but even when his left hand is unoccupied, he gestures like a maestro, beats time like a conductor, and seems to caress the very air that carries his soundwaves with a graceful fluidity and almost a femininity that speaks of the level of care he takes over his music. It is, all, played very live. The rare glitches and flubs and moments where Ralf alters a melodic line by half a beat or mispronounces a word, echoed through layers of vocoder and harmonic duplication only serve to highlight the utter perfection that Kraftwerk normally achieve. With the exception of The Robots, where the machines are left to play by themselves, it is for the most part not heavily sequenced. These are fallible human beings playing with and against and through the grid of the machine.

I arrived over an hour early at the Royal Albert Hall, which, given the stringent ID and bag checks (and the resultant queues, which delayed the start of the performance by nearly 20 minutes) turned out to be a very sensible choice. So I stood in the bowels of the building, while a friendly concierge held open the door to take advantage of the limited air conditioning, listening to the soundcheck, feeling my fangirl excitement rise. The whole thing felt unreal, until that moment, listening to Ralf level-check his vocals, his microphone, his vocoder, the mix level of the plug-in that allows him to manipulate the harmonics of his own voice using his keyboard, even barking at his technicians in his rapid-fire Düsseldorf German. Of course Ralf speaks to his crew in German, what other language would he use? (Well, over the course of the evening, he sings fluently in English, German, French, Spanish and Japanese, so this is not an entirely moot question.) But the detail still delights me.

But after the long wait, watching the band while they performed felt oddly unsatisfying. Rather than a concert or a rave, it felt like watching an extremely well-shot film of a Kraftwerk performance projected with perfect verisimilitude. I felt very detached from the show, a spectator at a spectacle, rather than a participant in a sea of bodies and minds melding to a hypnotic beat. Maybe it was the cramped seats. It is very, very hard to dance while seated (I gave it my best) and any attempts at dancing in the aisles were shut down quite quickly by enormous and terrifying bouncers. Many of the songs have been updated specifically for dancing – Spacelab has always been a banger, but Airwaves in particular has been remade with such a throbbing disco bassline that I quipped it had become “I Feel Space” (though it’s important to remember that both Moroder and Lindstrom are inheritors of a lineage of which Kraftwerk were the progenitors). Yet as I cast my eye over the front rows, all of us filming and photographing in flagrant disregard of the posted regulations (it’s odd that we were specifically told not to film, but smartphones were not policed in the way that dancing bodies were) I realise that it is not Kraftwerk who are trapped at computer terminals, checking their emails, unable to dance, but us.

I hate to admit it, but I was bored during The Model, though the audience certainly greeted it most triumphantly, the one moment where defiant dancers outnumbered the heavies. But that one line – “For every camera she gives the best she can” – lampshaded what former Kraftwerker Karl Bartos would later make explicit in his solo work. Photography, like scientific observation in the uncertainty model, changes not just The Model, but the Photographer, too. I was not just watching and listening to Ralf Hütter, but I was aware, constantly, of my Taschen-Computer in der Hand, wanting to capture every adorably satisfied smile, every hand gesture, every crinkle of that imperiously pointed nose demarking the beats of the song. I don’t hold the data-memory; the data-memory holds me. And it changes everything. I noticed, as I was focusing, for dozens of photos, that Ralf kept looking over, turning directly into the gaze of my camera.

At first, I thought this was due to the huge gender imbalance of the front rows. It’s odd. I know from online fandom that Kraftwerk have many, many female fans. Yet that concert, overwhelmingly, at least 2 to 1, was, as another lone woman behind me put it, “a sausage party”. (This, I believe is not about lack of female interest in Kraftwerk, but about age and demographics. I saw a number of older men attending with adult children. I saw no younger children at all. And unfortunately, removing children from an audience, in this culture, almost always means removing an entire generational block of women. However, this did make for a refreshing lack of bathroom queues.) There were perhaps only 3 or 4 women in the front section, all gathered just in the spot where Ralf coincidentally kept throwing his gaze. It’s a shock, the moment that one, as an audience member, realises that the musicians can see their audience. I recognise this may have been entirely my imagination, but there was a sequence (during Autobahn, IIRC) when Ralf was soloing particularly intensely, his legs far apart, his lyrca-clad crotch angled just so, in a stereotypically Rock Star, and particularly uncharacteristic-for-Ralf pose. But as I raised my camera a little higher to try to capture it, Ralf glanced up, appeared to lock eyes with me, clocked the camera, and immediately snapped to, standing up straight and closing his untowardly splayed legs. Ralf’s modesty was preserved; I did not get my photo of this particular area of interest.

It was not until much later, after the concert, going through my photos on the train home that I worked out what was really happening. In most of my close-ups, Ralf’s eyes were downcast, focusing very intently on something on the top left corner of his workstation. Fan photos of their equipment reveal that to the top left of Ralf’s keyboard are where the filter sweeps, pitch-bend wheel and other sound modification and control devices are located. Every interaction was almost certainly entirely my imagination. Ralf’s attention was not drawn by our presence, but by his own tech.

But my hunger for this moment of connection, so strong as to conjure it from brief glances, seems to highlight precise lack that prevents me from fully enjoying the show. When I listen to live Kraftwerk recordings alone, on headphones, the sense of connection is so complete, so total, that it can reduce me to tears. But at the venue, I cannot seem to exist in the moment, and not try to mediate the experience through a screen. But Kraftwerk’s very theme, through most of the work they play, from Airwaves and Neon Lights to Computer Love and Electric Café, and right through to the various Étapes of the Tour de France Soundtracks, is the mediation of communication through technology. “Transmission, television / Reportage sur moto / Camera, video et photo.”

Through the medium of technology, the group have preserved their own departed former members. To watch Kraftwerk live is to listen to ghosts, preserved flickering in their machines. The bombastic middle section of Trans Europe Express – Metall auf Metall – is a triumph of technology finally catching up with Kraftwerk’s ideas. For years, their percussionists struggled to recreate the industrial Klang of sheet metal using primitive, complicated drum-pads made from spare parts and triggered with electrically conductive knitting needles and rickety volume pedals. Now, each element of the cacophonous symphony is triggered by a fingertip’s touch on a sample pad. Kraftwerk have launched decades-long lawsuits detailing who, precisely has the right to use those samples. And yet, it seems odd how much of their sound-paintings (and 3D film-paintings) are dependent on the precise digital recreation of sounds (and images) of people who are no longer present.

Ralf’s long-term collaborator, the co-founder of the band, Florian Schneider, though his madcap, slightly sinister presence is long-gone from stage right, is, even in his absence, a constant, palpable presence to the observant fan. It is Florian’s heavily vocodered voice, rather than Ralf’s, that echoes through Radioactivity, enumerating the contaminated sites – Tschernobyl, Harrisburgh, Sellafield – whose accidents stand as warnings to us all. In the animations that accompany Autobahn, based on Emil Schult’s playful album cover painting, a VW Beetle and a Mercedes 600 Limousine chase one another about an imagined German countryside. The grey Beetle with Krefeld plates (I always thought the KR of those plates referred to Kraftwerk, until I visited Krefeld, and was surrounded by KR plates) was Ralf’s car, which Kraftwerk toured in through much of the early 70s. The presidential blue Mercedes, on the other hand, was Florian’s notoriously temperamental trophy ride, detailed in numerous Kraftwerk biographies. Knowing this detail, it’s hard to watch this film and not imagine the two Boy Racers still chasing one another down the Autobahn.

During the last encore’s medley, from Techno Pop into Music Non Stop, the projections showed Rebecca Allen’s groundbreaking wire-frame computer animations of the band in the 80s, looking both very cool and hip in a retro way, but still amazingly futuristic. Again, it is slightly disconcerting to watch a youthful Ralf’s digitised head rotating above his more elderly body. But as the animations lovingly detail the computerised creation of the wire-frame head from digital points, then lines, to angled surfaces and a recognisably human shape, it soon becomes clear that the face slowly materialising on the screen is in fact Florian, with his very distinctive prow of a nose, and bright, mad scientist eyes. Part of me wants to dismiss this as a simple mistake, choosing the wrong file; but another part of me wants to believe that Kraftwerk do not make mistakes, despite the plentiful evidence of the charming human fallibility of this tour. It feels deliberate, that Florian’s digital ghost still hangs heavy over this museum-quality archive of Kraftwerk’s performance.

In their traditional final sequence, each musician takes a final solo, showing off their Technik, before moving to the side of the stage for a final bow and a wave – or kiss – goodnight. At the end, Ralf is left alone, improvising steadily lower on a ghostly vocodered chorus of sampled “oh”s, until the pitch becomes too low for humans to hear. I’ve watched his livestreamed goodbyes from a dozen YouTubed performances, and yet he never fails to look surprised and a little overwhelmed by the intensity of the audience’s love for him. I am concentrating too hard on filming to see until later, his nervous ticks, his shy little jig of pleasure, his repeated bows, hand on heart – I could have sworn he blew us a kiss, but I may have forced that, too, into being with the strength of my own desire.

#kraftwerk#Ralf Hütter#henning schmitz#Fritz Hilpert#falk grieffenhagen#every time I type his name the notes suggest Falk Griffindor#long post

22 notes

·

View notes