#alan schmierer

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Brant goose standing in tidelands.

Photo by Alan Schmierer.

Brant geese: a favorite among bird watchers, hunters in Western Washington

Brant and other waterfowl feeding at the Three Crabs property in the WDFW-managed Dungeness Wildlife Area Unit.

Brant in defensive position.

Photo by Tim Bowman/USFWS.

#alan schmierer#photographer#brant goose#goose#bird#animal#dungeness wildlife area unit#washington#landscape#nature

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A new variant has been added!

La Sagra's Flycatcher (Myiarchus sagrae) © ALAN SCHMIERER

It hatches from crested, dull, great, inconspicuous, lean, quick, similar, slender, sweet, woodland, and yellow eggs.

squawkoverflow - the ultimate bird collecting game 🥚 hatch ❤️ collect 🤝 connect

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scaled Quail (Callipepla squamata), family Odontophoridae, Santa Cruz County, Arizona, USA

photograph by ALAN SCHMIERER

736 notes

·

View notes

Text

BOTD: Five-striped Sparrow

Photo: Alan Schmierer

"This elegant Mexican sparrow was never found in our area until the late 1950s. It is now known to be a rare and local nesting bird in several canyons in southern Arizona, but no one knows if it was simply overlooked in the past or if it is actually a recent arrival north of the border. The Five-striped Sparrow favors steep brushy hillsides, where the male often sings his metallic song while perched on the spindly stems of ocotillo."

- Audubon Field Guide

#birds#five striped sparrow#birds of north america#north american birds#sparrows#passerines#birds of the us#birds of mexico#birding#bird watching#birdblr#birblr#bird of the day#Amphispiza quinquestriata

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

A very long Scissor-Tailed Flycatcher. Photo by Alan Schmierer [CC0 1.0].

I'm going on a stakeout tomorrow morning to find the one that's been hanging around the park these past few days.

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Author:

Melonie Schmierer-Lee and Alan Elbaum

Wed 22 Jun 2022

Alan, which fragment are you looking at today?

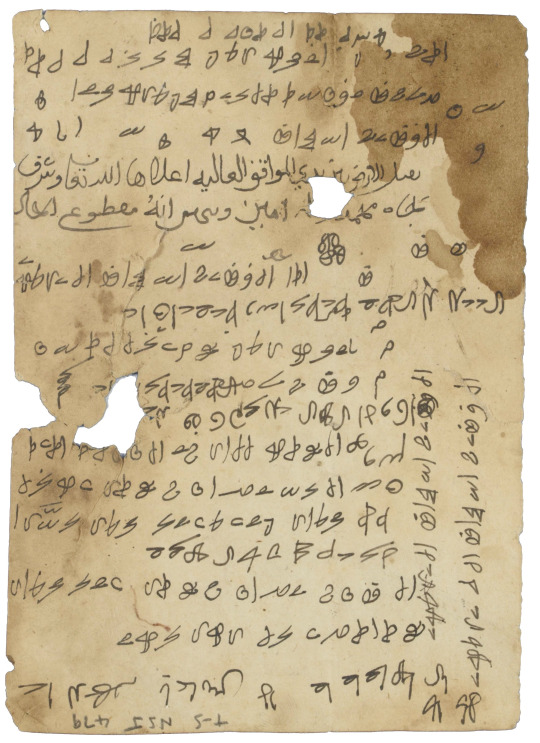

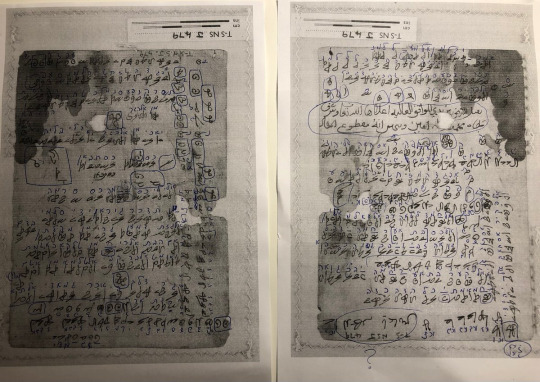

My job description at the Princeton Geniza Project is to look at uncatalogued or minimally catalogued documentary fragments, and while looking for these I came across T-S NS J479, a single page covered with strange symbols written in all directions. I’ve probably glanced at around 50,000 Genizah fragments by now, and I’ve never seen anything that looks like this.

What is it? Which language is it?

Most of it is written in what I think is a made-up code, though whether it was invented or borrowed by the writer, I don’t know. There’s also some Arabic and Hebrew script (the Arabic is a petition formula). At first glance one of the symbols reminded me of one from the Voynich manuscript, so that set me wondering whether the symbols were meaningful. I noticed the same set of around 22 symbols all in a row, written a number of times, and wondered if the letters could be assigned to an alphabet. As there are roughly 22, the Hebrew alphabet fits better than Arabic. The language seems to be Judaeo-Arabic though. I’ve annotated an image of the fragment showing the ‘translation’ of the cipher into Hebrew script.

Why do you think he wrote out the alphabet several times?

Maybe he was trying to work out his alphabet. Towards the end he’s a bit inconsistent with some of the symbols assigned to each Hebrew letter, so perhaps he was refining it. He also writes the cipher alphabet from left to right at one point, which was interesting to me.

We keep saying ‘he’ – do we know who the author was?

He writes his name – ‘al-faqīr Isḥāq al-Yahūdī’ – as well as two verses from the revered Sufi poem known as Qaṣīdat al-Burda by Al-Būṣīrī (fl. 13th century), so that helps to date the fragment somewhat. Here are the lines in Stetkevych's translation (Suzanne Pinckney Stetkevych, The Mantle Odes: Arabic Praise Poems to the Prophet Muhammad (Bloomington, IN, 2010), p. 92.):Was it the memory of those you loved at Dhū Salam / That made you weep so hard your tears were mixed with blood? Or was it the wind that stirred from the direction of Kāẓimah / And the lightning that flashed in the darkness of Iḍam?

It’s Mamluk or perhaps Ottoman era. There’s also some pornography. I’ve learned two different words for penis and all sorts of other terms while studying the text. It’s fairly graphic. It ends ‘all of this is lies’, so perhaps Isḥāq was covering his tracks in case his parents cracked his code! Kind of frivolous but also kind of interesting.

Do you know of any other ciphers that have been found in the Cairo Genizah?

Gideon Bohak has written about at least one cipher that he’s found in the Genizah, and Oded Zinger has found a letter in Arabic and Judaeo-Arabic with a portion in an incomprehensible cipher. Almost all the words begin with alef, which makes us think it’s not a straightforward substitution cipher. Amir Ashur pointed out that some merchants in the India Book use Coptic numerals to create a secret code that hasn’t yet been cracked. I put this fragment up on social media after I started working on it, and people offered up all sorts of interesting parallels. Arianna D’Ottone-Rambach shared her article on an encrypted Quran manuscript that I hadn’t known about, for example. I’m so excited to join the field when this spirit of collaboration is recognised and valued. If I can make a discovery that lets someone else discover something further, then that’s all the better.

Thanks, Alan!

Alan Elbaum is a Senior Researcher at the Princeton Geniza Project.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Semifinals: Match 51

[Image ID: Two pictures of gulls. The left is an ivory gull sitting on snow. The right is a Ross's gull walking on a grassy bank. /End ID]

The ivory gull (Pagophila eburnea) is a mid-sized gull that has a circumpolar distribution around the Arctic. They typically measure 40-43 cm (16-17 in) in length and 108-120 cm (42-47 in) in wingspan. They have a more pigeon-like shape than other gulls. Their plumage are completely white, and they have black legs and a thick blue bill with yellow tip. They feed on fish, crustaceans, rodents, eggs, and small chicks. They have been known to follow polar bears and other predators to scavenge on the remains of their kills. Because of their declining population, possibly due to illegal hunting or to decline in sea ice, they are listed as near threatened by the IUCN.

The Ross's gull (Rhodostethia rosea) is a small gull found in the high Arctic of northern North America, northeastern Siberia, and the Bering Sea. They typically measure 29-31 cm (11-12 in) in length and 90-100 cm (35-39 in) in length. They have a white head, black neck ring, white underparts with a pink flush, light grey upperparts and wings, red legs, and small black bill. They have a distinctive wedge-shaped white tail. They feed on small fish, crustaceans, and insects. They also eat biofilm, the mixture of plankton, microbes, and detritus that washes up on beaches and intertidal areas.

ivory gull image by Alan Schmierer

Ross's gull image by Tom Wilberding

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

^image: By ALAN SCHMIERER - https://www.flickr.com/photos/sloalan/16935159393/, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=57031708

Scaled Quail (Callipepla squamata)

The Scaled Quail, getting its wonderfully rhyming name from the scale-like feather patterns, is found in arid regions from the Southwestern United States to Central Mexico. Scaled Quails are opportunistic feeders and consume more grass seeds than other quail species. When they are disturbed, they hide in clumps of grass or in snakeweed.

#let me know if you guys think there's any way i could improve the formatting of the credit#i'd prefer to keep the full links in there but#if i could make it any more aesthetically pleasing do tell me! /gen#scaled quail#quails#quail#bird#birds#birding#tropical bird#tropical birds#callipepla squamata#birdwatching#bird of the day#birdoftheday#botd#bird facts#bird fact#bird fact of the day#daily facts#daily animal facts#daily bird facts#ornithology#bird lovers#birdlovers#birds of america#birds of mexico#cute birds#cute animals#animals

77 notes

·

View notes

Photo

California ground squirrel (Otospermophilus beecheyi)

Photo by Alan Schmierer

#california ground squirrel#otospermophilus beecheyi#otospermophilus#marmotini#xerinae#sciuridae#sciuromorpha#rodentia#glires#euarchontoglires#boreoeutheria#eutheria#mammalia#tetrapoda#vertebrata#chordata

29 notes

·

View notes

Link

The American Southwest provides a last stronghold for the yellow-billed cuckoo, which was officially listed under the Endangered Species Act as threatened in 2014. Photo by Alan Schmierer.

Excerpt from this story from the Earth Island Journal:

Some call the yellow-billed cuckoo the “rain crow,” based on a belief that its singing announces a coming storm. That’s just a myth, says Peter Tallman, an “opportunistic birder” and the only plumber for 100 miles in the southern New Mexico town where he lives. Work takes him through lots of backyards, where he pauses to listen or watch for the cuckoo’s characteristic swoop and spotted tail among the branches.

What is true, Tallman notes after six decades of watching birds, two of them in the Southwest, is that yellow-billed cuckoos are almost always found in the forested areas along waterways. He knows that from walking through those bosques or stopping for lunch at a riverbank, places with a density reminiscent of their former numbers.

The American Southwest provides a last stronghold for the yellow-billed cuckoo, which was officially listed under the Endangered Species Act as threatened in 2014. This February, the US Fish and Wildlife Service published a list of proposed protected areas that trace the curls and curves of rivers and streams in Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Texas, and Utah. Some say these new protections for the yellow-billed cuckoo’s future could extend to some of the West’s most threatened rivers.

“This is a bird that depends on healthy rivers, and what may be turning out here is that the rivers also depend on saving this bird,” says Michael Robinson, a conservation advocate with the Center for Biological Diversity, which has long sought protections for the western population of yellow-billed cuckoo.

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Pleasing Fungus Beetle

Photographer: Alan Schmierer

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Melanitta

Surf Scoter by Alan Schmierer, in the Public Domain

PLEASE SUPPORT US ON PATREON. EACH and EVERY DONATION helps to keep this blog running! Any amount, even ONE DOLLAR is APPRECIATED! IF YOU ENJOY THIS CONTENT, please CONSIDER DONATING!

Name: Melanitta

Status: Extant

First Described: 1822

Described By: Boie

Classification: Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Galloanserae, Anseriformes, Anseres, Anatoidea, Anatidae, Merginae

Referred Species (all extant): M. americana (Black Scoter), M. nigra (Common Scoter), M. fusca (Velvet Scoter), M. deglandi (White-Winged Scoter), M. perspicillata (Surf Scoter)

Today’s dinosaurs are the Scoters, a group of fairly black seaducks with distinctive swollen bills (though all of the females are browner and more speckled in appearance). They form large flocks on the coasts, and actually take off together in these huge flocks. There are five living species, and for now, no extinct species are known.

Black Scoter by Peter Massas, CC BY-SA 2.0

The Black Scoter, also known as the American Scoter, is a near-threatened large sea duck, weighing near 1 kilogram and found primarily in tundra of North America and easternmost Siberia. They not only have a bulky shape, but a very bulky bill with a yellow hump. They breed in the farthest north part of their range, and can be found further south in the winter, even spending the season as far south as the Great Lakes. They dive for crustaceans and molluscs on the sea coasts, though when they venture into freshwater they primarily feed on insects and larvae, as well as fish eggs and some plants. Their flocks are tightly packed on the coastal waters, though they are less social in the breeding season. They lay eggs close to the sea or in the tundra, with 5 to 7 eggs at a time, and only the females incubate the eggs. The young are flightless for about three weeks after hatching, during which time their mother protects them.

Common Scoter by Jason Thompson, CC BY 2.0

The Common Scoter is a non-threatened seaduck, bulky in shape with large lumpy bills. The bills are black with yellow patches. They live in Northern Europe and Asia, found in the tundra environment during the summer for the breeding season, and occasionally found as far south as Morocco during the winter. They form huge, tightly packed flocks on the coast that take off and dive together. The males have no white on their bodies, which makes them distinct from other Scoter species. They lay nests near the sea or in the tundra, and feed primarily on crustaceans and molluscs. Though not threatened with extinction, certain populations in the United Kingdom are on a sharp decline.

Velvet Scoter by Vince, CC BY 2.0

The Velvet Scoter is a threatened species, with smaller populations than the previous two species. They live during the winter in temperate Europe and Asia, and they nest in the far north, like other Scoters. They make nests on the ground close to the sea, where they dive for crustaceans and mollusks. They are bulky, with primarily yellow bills, and white patches on the wings, while the females are more brown. They are very rarely spotted in their range.

White-Winged Scoter by Lea Blumin, CC BY 2.0

The White-Winged Scoter is a non-threatened species, weighing nearly 2 kilograms in some cases, making them an extremely heavy species of Scoter - in fact, probably the heaviest of all. They breed in Western and Northern Canada and Alaska, and spend the winters along both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts, even sometimes far north along those coasts. To get to their winter range, they’ll even migrate and rest along the great lakes. They are very similar to the Velvet Scoter, but are currently considered to be a different species. They Are often found in Asia as well, even as far south as China. They form tightly packed flocks, which disband for the breeding season. They lay 5 to 11 eggs in a nest near the sea or lakes and rivers, and incubate them for a month. The females can be aggressive towards one another during the breeding season, and the young stay with the mother for about three weeks; and then together without the mom for another three weeks. Like other species in this genus, they feed on molluscs and crustaceans in the ocean, and insects and other crustaceans in freshwater.

Surf Scoter by Alan D. Wilson, CC BY-SA 2.5

The Surf Scoter is the last species in the genus, and a rather large one, weighing up to 1 kilogram in the males. The males are a very velvety black except for its beak, which is distinctively patterned with red, orange, white, and black. Their white patches on their heads make them very visually distinct from other Scoters. The females, however, are mottled brown, and less visually distinctive. THey spend the breeding season in Northern Canada and Alaska, and winter along the coasts of both oceans, even as far south as Mexico and Texas. They breed in boreal forests near northern freshwater lacks, which is different than other species. They breed during the summer and females protect the nests on their own, and though the mothers take care of the young at first, they abandon the young before they are able to fly. The offspring congregate in small groups, before going to the wintering grounds on their own and joining up with the adults.

Surf Scoter by Alan D. Wilson, CC BY-SA 2.5

It feeds primarily on ocean invertebrates, and they’ll form small groups during the breeding season to eat a lot of different types of freshwater invertebrates, though their primary food is still ocean invertebrates, especially crustaceans and molluscs. They do shift their diet depending on food availability, indicating opportunism in the species - both in terms of what they eat and where they eat, often switching habitats to find more food. They will even capture food and eat it whole. They migrate over a variety of routes, usually with females and juveniles sticking together and the males in their own group. There are estimated to be up to a million of these birds throughout the world.

Buy the author a coffee: http://ko-fi.com/kulindadromeus

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scoter

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_scoter

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Common_scoter

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Velvet_scoter

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/White-winged_scoter

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Surf_scoter

#melanitta#scoter#bird#dinosaur#duck#birblr#seaduck#black scoter#common scoter#velvet scoter#shite-winged scoter#surf scoter#melanitta americana#melanitta nigra#melanitta fusca#melanitta deglandi#melanitta perspicillata#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature#factfile#Dìneasar#דינוזאור#डायनासोर#ديناصور

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gyrocheilus patrobas

Photograph by Alan Schmierer

Red Bordered Satyrs (Gyrocheilus patrobas), family Nymphalidae, Yavapai county, Arizona, USA

photograph by Peter DeGennaro

#red boardered satyr#gyrocheilus patrobas#range: north america#family nymphalidae#subfamily satyrinae

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

BOTD: Green-tailed Towhee

Photo: Alan Schmierer

"A catlike mewing call in the bushes may reveal the presence of the Green-tailed Towhee. Fairly common in western mountains in summer, this bird spends most of its time in dense low thickets, where it forages on the ground. Like other towhees, it scratches in the leaf-litter with both feet as it searches for food. It sometimes wanders east in fall, and strays may show up at bird feeders in winter as far east as the Atlantic Coast."

- Audubon Field Guide

#birds#green tailed towhee#birds of north america#north american birds#sparrows#towhees#passerines#birds of the us#birds of mexico#birding#bird watching#birdblr#birblr#bird of the day#Pipilo chlorurus

52 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Antelope Jackrabbit (Lepus alleni)

The Antelope Jackrabbit of Arizona and Mexico uses its long legs to reach a top speed around 44 m.p.h., more than enough to escape a bobcat.

Antelope Jackrabbits are the biggest North American hare species, up to 22 inches long and as much as 9 lbs. Their giant white-tipped ears wave over their heads around 6 inches high, and might help Jackrabbits moderate their body temperature.

They prefer hilly grasslands over desert ecosystems, unlike other jackrabbit species of the Southwest. Antelope Jackrabbits bear their babies in shallow scrapes, but the babies don’t stay put long. The wide-eyed leverets can hop as soon as they’re born, and spend their hours quietly hiding while their mother forages, only feeding when she returns to quickly nurse at dawn and dusk. photograph by Alan Schmierer | Flickr

via: Peterson Field Guides

71 notes

·

View notes

Photo

October 6 Pelagic

I went on what will probably end up being my last-of-the-year pelagic birding trip out of Ventura Harbor last weekend. The sunrise was pretty. And the birds! The official lists are still being tabulated, but it looks good for 6 new county-year birds for me. It gets tricky because we were passing back and forth through Ventura and Santa Barbara County waters – and actually a tiny bit of LA County waters as well. Because of my county year list obsession I was more excited about the Santa Barbara birds than the Ventura birds. But they were all great.

My sister and brother-in-law came along and it was fun to share the obsession with them. M’Liz volunteers with the American Cetacean Society’s gray whale census, so she’s all about the marine mammals; her favorite part of the trip was when we cruised alongside a humpacked whale that rewarded us with a full-on out-of-the-water breach. Hugh Ranson was one of the people who got a photo of the breach in-progress.

I’ll talk about the new county year birds I saw after a cut to preserve your dash.

Note: Except as indicated, the photos below aren’t by me and don’t show the actual birds I saw. They’re photos I googled up that generous people have shared under a Creative Commons license.

#309: Pomarine Jaeger (Stercorarius pomarinus)

Photo by Martyne Reesman, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife

We saw several “poms” as we were heading out past Anacapa Island, and kept seeing them as we headed south into the “donut hole” (the circle of ocean around Santa Barbara Island that has been deemed part of Santa Barbara County for bird-listing purposes). One of the birds even had the breeding-plumage “spoons” (long central tail feathers with a twist at the end) that you can see in this photo. I’ve always wanted to see those!

#310: Craveri’s Murrelet (Synthliboramphus craveri)

Photo by Tom Benson

We saw (and heard, one time) a few pairs of these as we approached Santa Barbara Island. Later, on the trip home, we saw a few more pairs, then one trio that I assume was mom, dad, and a chick. They were all adorable.

#311: Least Storm-Petrel (Oceanodroma microsoma)

Photo by Alan Schmierer

This is a species that I saw, technically, but would not have been able to identify from the brief look I got if it weren’t for a boatload of experts shouting, “Least Storm-Petrel!” But with the benefit of their input I did notice that this storm-petrel was super tiny compared to the Black and Ashy Storm-Petrels we’d been seeing.

#312: Blue-footed Booby (Sula nebouxii)

Photo by Vince Smith

This was a biggee for me. I’ve always wanted to see one, and I knew one had been seen on the previous Island Packers pelagic trip (which I didn’t go on). Then one had been seen just a few days before our trip, hanging out at Santa Barbara Island with the big group of Brown Boobies that nested there this year, so we were hoping it would still be there. And… it was!

Hugh’s photo of the bird we saw is here. Here’s a shot from my phone of the upper deck after the excitement had started to wear off:

The Blue-footed Booby is actually in the shot; here it is cropped and arrowed:

Those other specks on the cliff are mostly Brown Boobies. It was a very booby day. 🙂

#313: Buller’s Shearwater (Puffinus bulleri)

Photo by Jamie Chavez

We saw one of these mixed in with the thousands of Black-vented Shearwaters and the few dozen Pink-footed Shearwaters we steamed through in Ventura County waters, so I was primed and on the lookout for another near Santa Barbara Island. No more showed up, though, and I was thinking I wouldn’t get to add one to the county list, when bam! One showed up right next to the boat, zipping by under the bow and giving a beautiful view of that “M” pattern on its upper wings and back. Yay!

These birds are amazing. They breed in New Zealand, then spend the year doing a huge clockwise circle around the Pacific Ocean. Dave Pereksta, the birder who organized this trip, said he thinks they’re the prettiest of the shearwaters. I think he’s right.

#314: Sabine’s Gull (Xema sabini)

Photo by Andy Reago & Chrissy McClarren

As we headed back toward the harbor I was happy with the birds I’d seen, and starting to settle into that tired-and-sitting-and-comparing-notes phase that all pelagic trips seem to end on, when the boat slowed unexpectedly. A kelp paddy to starboard had some terns on it… Common Terns, it turns out, which are great birds, though a species I already had for the county year list. But mixed in with them were two Sabine’s Gulls! 😀

Booby addendum:

I’m burying the lead, but the big news from the trip was the boobies: We saw all five booby species in a single day, which Dave Pereksta believes had not been done before in the ABA area:

A Masked Booby (my first ever) on Anacapa Island (Ventura County, alas)

A Red-footed Booby (also my first ever) that flew alongside the boat as we steamed south (also in Ventura County)

The aforementioned Brown Boobies on Santa Barbara Island

The Blue-footed Booby on Santa Barbara Island

A Nazca Booby that we chased down in a big group of shearwaters southeast of Santa Barbara Island (a great bird, and in the right county, but a species I already saw on a previous trip)

7 notes

·

View notes