#akitu

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Festivals in Ancient Mesopotamia

Festivals in ancient Mesopotamia honored the patron deity of a city-state or the primary god of the city that controlled a region or empire. The earliest, the Akitu festival, was first observed in Sumer in the Early Dynastic Period (2900-2334 BCE) and continued through the Seleucid Period (312-63 BCE) along with other religious celebrations.

Continue reading...

52 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fêtes de l'Ancienne Mésopotamie

Les fêtes de l'ancienne Mésopotamie honoraient la divinité protectrice d'une cité-État ou le dieu principal de la ville qui contrôlait une région ou un empire. La plus ancienne, la fête de l'Akitu, fut observée pour la première fois à Sumer au début de la période dynastique (2900-2334 av. J.-C.) et se poursuivit pendant la période séleucide (312-63 av. J.-C.) en même temps que d'autres célébrations religieuses.

Lire la suite...

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Festivales de la Antigua Mesopotamia

Los festivales de la Antigua Mesopotamia honraban a los patrones divinos de una ciudad estado o al dios principal de la ciudad que controlaba la región o el imperio. El más antiguo de todos es el festival Akitu, que se llevó a cabo por primera vez en Sumeria durante el periodo dinástico arcaico (2900-2334 a.C.) y siguió celebrándose durante el periodo seléucida (312-63 a.C.) además de otras celebraciones religiosas.

Lire la suite...

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

1er avril : le nouvel an assyrien, la plus ancienne fête du monde

Le Nouvel An assyrien (Kha b-Nisan ou Akitu) est célébré chaque année le 1er avril dans tous les pays où résident les Assyro-Chaldéens, tel qu’on les appelle en France.

Des habitants de la Mésopotamie se sont distingués de leurs voisins zoroastriens ou juifs, le jour où ils ont adopté le christianisme. Ils ont toujours formé une minorité opprimée, surtout depuis que la région a embrassé très majoritairement l’islam comme religion dominante et officielle. Pendant la Première Guerre mondiale, comme les Arméniens, ils ont subi un génocide qui aurait pu les faire disparaître si la diaspora n’avait pas pris le relais de la préservation de leurs particularismes. Ils ont presque disparu de Turquie, seules subsistent des communautés notables de chrétiens d’Orient dans le nord de l’Irak et de la Syrie ainsi qu’en Iran. Mais, on les retrouve aussi au Liban, en Jordanie, en Arménie, aux États-Unis, au Canada, en France, en Allemagne…

Pour cette nation sans État, la célébration du nouvel an est un élément identitaire fort. La date du nouvel an assyrien repose sur le fait que cette fête du printemps, à l’instar de Nowrouz, était fixée le 21 mars selon le calendrier julien. Dans l’Antiquité, le solstice du printemps était l’occasion de célébrer Tammouz, dieu de l’agriculture et Isthar, déesse nourricière, incarnation de la fertilité et de la fécondité. L’adoption du calendrier grégorien, l’a fait glisser au 1er avril. Les Assyriens, dont les racines sont très anciennes possèdent leur propre calendrier qui commence en l’an 4750 av. J.-C. De notre calendrier. De fait, ce 1er avril, les Assyro-Chaldéens entrent dans leur 6774e année. Ce qui fait de cette fête, la plus ancienne au monde.

Dans l'impossibilité de se regrouper, en raison de l'insécurité, dans leurs anciennes capitales de Babylone ou Ninive, les Assyriens parviennent à célébrer leur fête au Kurdistan, en Arménie ou surtout en diaspora. Cette fête est marquée par des défilés en costume traditionnels et des pique-niques, si le temps le permet. Cette fête d’origine païenne, appelée Akitu, durait autrefois 12 jours, du 20 mars au 1er avril du calendrier grégorien. C’est un marqueur identitaire des chrétiens d’Orient.

Un article de l'Almanach international des éditions BiblioMonde, 31 mars 2024

0 notes

Text

Isaiah 46: Incomparable God

Have you ever caught yourself saying, “Well, that is just life?” It is what it is. #Isaiah64 #IncomparableGod #Akitu

Have you ever caught yourself saying, “Well, that is just life?” It is what it is. I say it a lot, but after reading today’s passage, I have been weighing that phrase a little bit more thoughtfully. There is truth to it. Our planet has been loaded under a curse since the dawn of civilization. The first people who inhabited earth took a pivotal turn in the course of human history, which ushered…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

Les Assyriens célèbrent l'Akitu dans le nord de la Syrie

L’Akitu, nom donné à la fête du Nouvel An dans l’ancienne Mésopotamie, est l’une des plus anciennes fêtes du monde. Elle tire son nom du mot “orge”, emblème de la civilisation et de la vie florissante dans toute la région. Le 1er avril, les Assyriens du monde entier ont célébré la fête du printemps Akitu pour marquer le début de la nouvelle année. Les populations chrétiennes de la région…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Note

What would the Emperor think of Big D

He'd hate him, I think. Someone who refuses to listen to him, is as stubborn as him, and loudly shouts him down as an "OSSEOUS SPECTRE OF AKITUS PAST" or something

196 notes

·

View notes

Text

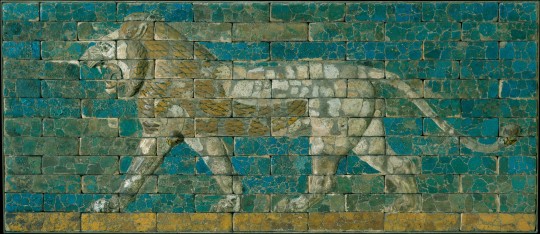

Panel with Striding Lion

Babylonian, ca. 604–562 BCE

The most important street in Babylon was the Processional Way, leading from the inner city through the Ishtar Gate to the Bit Akitu, or "House of the New Year's Festival." The Ishtar Gate, built by Nebuchadnezzar II, was a glazed-brick structure decorated with figures of bulls and dragons, symbols of the weather god Adad and of Marduk. North of the gate the roadway was lined with glazed figures of striding lions. This relief of a lion, the animal associated with Ishtar, goddess of love and war, served to protect the street; its repeated design served as a guide for the ritual processions from the city to the temple.

61 notes

·

View notes

Note

do you have any sources on the worship of the goddess inanna/Ishtar during the Seleucid/Hellenistic period to the Parthian period? i dont recall stumbling upon anything talking about her.

even though from what I've been reading mesopotamian deities were still popular (like bel-marduk in Palmyra and nabu in Edessa or shamash in hatra and mardin or sin in harran etc etc.. ) i dont recall reading anything about her or anything mention her worship (other than theories of the alabaster reclining figurines being depictions of her)

A good start when it comes to late developments in Mesopotamian religion is Religious Continuity and Change in Parthian Mesopotamia. A Note on the survival of Babylonian Traditions by Lucinda Dirven.

Hellenistic Uruk, and by extension the cult of Ishtar, is incredibly well documented and the most extensive monograph on this topic, Julia Krul’s The Revival of the Anu Cult and the Nocturnal Fire Ceremony at Late Babylonian Uruk, is pretty much open access (and I link it regularly here, and it's one of my to-go wiki editing points of reference as well); it has an extensive bibliography and the author discusses the history of research of the development of specific cults in Uruk in detail. The gist of it is fairly straightforward: her status declined because with the fall of Babylon to the Persians the priestly elites of Uruk decided it’s time for a reform and for the first time in history Anu’s primacy moved past the nominal level, into the cultic sphere, at the expense of Ishtar and Nanaya. Even the Eanna declined, though a new temple, the Irigal, was built essentially as a replacement; we know relatively a lot about its day to day operations. An akitu festival of Ishtar is also well documented, and Krul goes into its details. All around, I don’t think the linked book will disappoint you.

An important earlier work about the changes in Uruk in Paul-Alain Beaulieu’s Antiquarian Theology in Seleucid Uruk. There’s also Of Priests and Kings: The Babylonian New Year Festival in the Last Age of Cuneiform Culture by Céline Debourse which covers Uruk and Babylon, but there is less material relevant to this ask there. Evidence from Upper Mesopotamia and beyond is more fragmented so I’ll discuss it in more detail under the cut. My criticism of this take on the reclining figures is there as well.

The matter is briefly discussed in Personal Names in the Aramaic Inscriptions of Hatra by Enrico Marcato (p. 168; search for “Iššar” within the file for theophoric name attestations). References to a deity named ʻIššarbēl might indicate Ishtar of Arbela fared relatively well (for her earlier history see here and here) in the first centuries CE. The evidence is not unambiguous, though. This issue is discussed in detail in Lutz Greisiger’s Šarbēl: Göttin, Priester, Märtyrer – einige Probleme der spätantiken Religionsgeschichte Nordmesopotamiens. Theophoric names and the dubious case of ʻIššarbēl aside, there are basically no meaningful attestations of Ishtar from Hatra, but curiously “Ishtar of Hatra” does appear in a Mandaic scroll known as the “Great Mandaic Demon Roll”. According to Marcato this evidence should not be taken out of context, and additionally it cannot be ruled that we’re dealing with a case of ishtar as a generic noun for a goddess (An Aramaic Incantation Bowl and the Fall of Hatra, pages 139-140; accessible via De Gruyter). If this is correct, most likely Marten (the enigmatic main female deity of the local pantheon), Nanaya or Allat (brought to Upper Mesopotamia by Arabs settling there in the first centuries CE) are actually meant as opposed to Ishtar.

Joan Goodnick Westenholz suggested that Mandaic sources might also contain references to Ishtar of Babylon: the theonym Bablīta (“the Babylonian”) attested in them according to her might reflect the emergence of a new deity derived from Bēlet-Bābili (ie. Ishtar of Babylon) in late antiquity (Goddesses in Context, p. 133)

In addition to Marcato’s article listed above, another good starting point for looking into Mesopotamian religious “fossils” in Mandaic sources is Spätbabylonische Gottheiten in spätantiken mandäischen Texten by Christa Müller-Kessler and Karlheinz Kessler; Ishtar is covered on pages 72-73 and 83-84 though i’d recommend reading the full article for context. The topic is further explored here.

In his old-ish monograph The Pantheon of Palmyra, Javier Teixidor proposed that the sparsely attested local Palmyrene goddess Herta (I’ve also seen her name romanized as Ḥirta; it’s agreed that it’s derived from Akkadian ḫīrtu, “wife”) was a form of Ishtar, based on the fact she appears in multiple inscriptions alongside Nanaya (p. 111). She is best known from a dedication formula where she forms a triad with Nanaya and Resheph (Greek version replaces them with Hera and Artemis, but curiously keeps Resheph as himself). However, ultimately little can be said about her cult beyond the fact it existed, since a priest in her service is mentioned at least once.

I need to stress here that I didn’t find any other authors arguing in favor of the existence of a supposed Palmyrene Ishtar. Joan Goodnick Westenholz mentioned Herta in her seminal Nanaya: Lady of Mystery, but she only concluded that the name was an Akkadian loanword and that she, Resheph and Nanaya indeed formed a triad (p. 79; published in Sumerian Gods and their Representations, which as far as I know can only be accessed through certain totally legit means). Maciej M. Münnich in his monograph The God Resheph in the Ancient Near East doesn’t seem to be convinced by Teixidor’s arguments, and notes that it’s most sensible to assume Herta seems to be Nanaya’s mother in local tradition. He similarly criticizes Teixidor for asserting Resheph has to be identical with Nergal in Palmyrene context (pages 259-260); I’m inclined to agree with his reasoning, interchangeability of deities cannot be presumed without strong evidence and that is lacking here.

I’m not aware of any attestations from Dura Europos. Nanaya had that market cornered on her own. Last but not least: I'm pretty sure the number of authors identifying the statuettes you’ve mentioned this way is in the low single digits. The similar standing one from the Louvre is conventionally identified as Nanaya (see ex. Westenholz's Trading the Symbols of the Goddess Nanaya), who has a much stronger claim to crescent as an attribute (compare later Kushan and Sogdian depictions, plus note the official Seleucid interpretatio as Artemis for dynastic politics purposes), so I see little reason to doubt reclining figures so similar they even tend to have the same sort of gem navel decoration are also her, personally.

A great example of the Nanaya-ish statuette from the Louvre (wikimedia commons). To sum everything up: while evidence is available from both the south and the north, the last centuries BCE and first centuries CE were generally a time of decline for Ishtar(s); for the first time Nanaya was a clear winner instead, but that's another story...

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Gallery of Religious Festivals from Around the World

Religious festivals have featured as a central aspect of civilization for thousands of years, the earliest thought to be celebrations of the New Year and the concept of rebirth and new beginnings that accompanied it. The first such festival to be recorded is the Akitu festival at Babylon c. 2000 BCE.

The Akitu festival, a celebration of the New Year, evolved from the Sumerian celebration known as Zagmuk. Whether Zagmuk was the first such festival observed in the world is debated as there could have been others much older celebrated by the Indus Valley Civilization which are unknown as their script has not been deciphered. Most likely, as with dogs in the ancient world, religious festivals developed in various civilizations independently and were probably based on earlier, prehistoric, observances.

The following gallery presents only a small sample of worldwide religious festivals ranging from the Mesopotamian Akitu through the North American Sun Dance and Celtic Pagan sabbats designated by the Wheel of the Year. Those festivals still observed today adhere to the paradigm of the ancient rites in celebrating rebirth, renewal, and transformation.

Continue reading...

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mesopotamian Months

🌾 Some Notes 🌾

I cannot render these from screenshot to alt text / text ID, because the technology cannot read these texts correctly and often spouts out gibberish, my apologies.

Information on "normalizing" the languages LINK

For accuracy I maintained the notation of the book so vowels containing accent marks and the common Š which is pronounced like SH in shoe. Ĝ which is a tricky ng sound. Also some dotted consonants and Ḫ , but don't ask me how to pronounce those.

🌾My Source🌾

My two sources for this post are:

Festivals & Calendars of the Ancient Near East by Mark Cohen 2015

With some information coming from The Cultic Calendars of the Ancient Near East (LINK) by Mark Cohen 1993.

I tried to rely mainly on the 2015 book but I can't help but use some of the 1993 books since I've read it.

I'm positive there are other sources for months and such, but this is the most extensive and enjoyable— if I magically was an Assyriologist then I'd be able to use all the books references from so many other Assyriologists' assertions, papers, debatable concepts, and probably books, that I could read to further understand... alas I can't do that. So I stick to these books because calendars are generally neglected in Mesopotamian history books unless discussing specific reigns of King or Empires.

While neither have cuneiform in the book, it has extensive sign notation and references for those who know how to find cuneiform based on transliteration of signs. It is a very dense academic read, but some sections can be very useful for those who have at least some knowledge of university level reading.

🌾New Year🌾

The New Year takes place on the first crescent moon after the Spring Equinox.

The book mentions the Akiti festival Link (Akitu in Akkadian) the "New Year", often throughout the entire book, it also has an entire chapter for it on page 400, 1993. The origins of the Akiti can be found in page 125, 1993.

It seems religiously the "New Year" happened twice— the first crescent moon after the Spring Equinox & Fall equinox, to maintain prosperity for the coming 6 months. Most calendars month 1 starts in Spring. The original Akiti appears to be from Ur.

🌾City of Nippur's Calendar🌾

The amount of Mesopotamian calendars and month names is dizzying and worthy of a 400+ page book. However, it is Nippur's months that stood the test of time, continuing past the Sumerian language's death in the form of logograms/sumerograms.

Nippur served as the focal point for the religious life of the Sumerian cities and so it is understandable that its calendar would be the one to endure after the collapse of the Ur III empire. It became the official calendar under Isbi-Erra, who founded a kingdom with its capital at Isin after the collapse of Ur. Thereafter, the Sumerian writing of the Nippur month names or their abbreviation continued down to the end of the cuneiform tradition, but only as logograms for the month names of the Standard Mesopotamian calendar. (pp115, 2015)

Nippur's calendar dates all the way back to the 3rd millennium BCE while the full list of 12 names on a single tablet is known from Ur III (2112-2004 BCE) many of its months can be traced back to the Early Dynasty Period (approx 2900-2350 BCE). Its old to say the least.

🌀Months🌀

(pp116, 2015)

Bárazaggar

Ezemgusisù

Sigušubbaĝáĝar

Šunumun

Neiziĝar

Kiĝ -Inanna

Dukù

Apindua

Ganganè

Kùsu

Údduru

Šekinku

[Intercalary] Diri-šekiĝku

🌾"Southern Mesopotamian Sumerian" Calendar 🌾

This calendar arises in the 2nd millennium BCE (2000-1001 BCE) based on Nippur's

The third-millennium Sumerian calendar used at Nippur was adopted throughout much of southern Mesopotamia after the fall of Ibbi-Sin of Ur, an innovation perhaps of the first monarch of the new Isin dynasty, Išbi-Erra (2017-1985 BCE). It would remain in use until the reign of Samsuiluna of Babylon. Noting that Isin is but 18 miles south of Nippur and that, before Išbi-Erra established Isin as his capital, Isin was of relatively little political importance, it is quite conceivable that Isin utilized the prestigious Nippur calendar during the Ur IlI period. However, whether Išbi-Erra's actions were the imposition of the calendar already in use at Isin (i.e., the Nippur calendar)—thus the "victor's" calendar— or was a shrewd maneuver purposely utilizing the commonly revered Nippur calendar, the intent was the same: the economic and political unification of his new empire. The symbolism of Nippur as a unifying presence was not lost on the Isin monarchs, who made special efforts to participate in the rites at Nippur, as seen by Lipit-Istar's central role in the gusisu festival.

As merchants, scribes, and representatives of the government of the Isin Empire conducted business in the Diyala region, the official calendar may have followed, eventually being used simultaneously with (or perhaps even replacing) the local, northern calendars, so that when the First Dynasty of Babylon arose, it too was already using this Southern-Mesopotamian Sumerian calendar.

Although Amorite calendars were utilized by the Semitic centers farther to the north until about the twenty-first year of Samsuiluna of Babylon (1749-1712 BCE), the Southern-Mesopotamian calendar was used at these sites as well. Tablets from Mari dating to the first half of the eighteenth century BCE not only attest to the utilization of this Sumerian calendar, but indicate that these Sumerian month names were not merely logograms to express a Semitic month name, but were actually pronounced. (pp 233-234, 2015)

🌀Months🌀

(pp236, 2015)

Barazagĝar

Gusisá

Siga

Šunumun

Neiziĝar

Kin-Inana

Dukù

Apindua

Ganganè

Ab(a)èa

Šekinku

[Intercalary] Diri Šekinku

🌾"Standard Mesopotamian" Calendar🌾

This calendar is Akkadian— "Babylonian" is a dialect of Akkadian. Artificially evolved from the Southern Mesopotamian Calendar which itself naturally evolved from Nippur's Calendar— a legacy reaching all the way back through time to the Early Dynastic Period.

When, at the close of the third millennium BCE, the Southern Mesopotamian Sumerian calendar was imposed throughout southern Mesopotamia, quite likely by Išbi-Erra of Isin, the written Sumerian month names were not simply logograms for month names. This Southern Mesopotamian Sumerian calendar was an adaptation of the Sumerian Nippur calendar. Since Sumerian calendars had been in use in Sumer during the preceding Ur III period, and since the month names found in Sumer during this subsequent period were Sumerian, it is reasonable to suggest that this use of the Nippur Sumerian month names indicates the continuance of a written and oral Sumerian calendar tradition. Farther north, Amorite calendars were in use, while at Sippar, positioned on the border of the two cultural spheres, Sumerian and Semitic calendars were used interchangeably. Later, the written Southern-Mesopotamian Sumerian calendar month names were relegated to being simply logograms for the month names of the Standard Mesopotamian calendar. Eventually just the first cuneiform sign of the Southern-Mesopotamian Sumerian calendar month name was used as the month's logogram. (pp381, 2015)

▪️

Based on these peculiarities in the assignment of month names, the Standard Mesopotamian calendar may have been an artificial creation, a means to unify a divergent empire. It may have been difficult to perpetuate the use of a Sumerian calendar outside of southern Mesopotamia. However, the economic and political advantages of a single, standard calendar were as obvious in the second millennium BCE as they had been on a smaller scale hundreds of years earlier to Išbi-Erra of Isin. So, rather than select one particular city's calendar as the new Reichskalender a policy that might have alienated those cities on whom another city's calendar would have been imposed the Babylonian administration invented a hybrid Reichskalender, culling months from various calendars throughout the realm and beyond, thereby hoping to gain international acceptance. The use of Southern-Mesopotamian Sumerian month names as logograms for this new calendar is a clear signal that there was something "unnatural" about the development and imposition of this new calendar. The retention of the Southern-Mesopotamian Sumerian month names on written documents may have been a negotiating point to gain the acceptance of the former Sumerian cities with their proud scribaltraditions. Total imposition of non-Sumerian month names (written as well as spoken) on the scribes using the Southern-Mesopotamian calendar could have been counter-productive. The continuation of a written calendrical tradition that could be traced back to venerated Nippur may havebeen important to the scribal community, which was proud of its eclectic and ancient position in society. In summary, the Standard Mesopotamian calendar may have been conceived by Samsuiluna (or possibly Hammurabi), who felt the urgency to foster a sense of nationhood among the cities of his empire, many of which were in rebellion against him. Use of this new calendar spread without the use of military conquest, probably the facilitation of international commerce was the catalyst for eventual acceptance in places not under Babylonian control, such as Alalakh and Assyria. (pp385-386, 2015)

While the month names are written in Sumerian they are read as Akkadian. A 2nd millennium bilingual text of the month names was found (pp380, 2015):

Here is a "conversion" of the Akkadian part of the bilingual text to the normalized Akkadian names found on book page 303, 1993:

🌀Months Sumerian to Akkadian🌀

First is Sumerian -> Second is Akkadian

Barazaggar -> Nisannu

Gusisá -> Ayaru

Sigga -> Simānu

Šunumunna -> Tamūzu (alt: Du'uzu)

Neizigar -> Abu

Kin-Inana -> Ulūlu / Elūlu

Dukù -> Tašritu

Apindua -> Araḫsamnu / Markašan

Ganganna -> Kissilimu

Abbaè -> Ṭebētu

Udra -> Šabāṭu

Šekinku -> Addaru

Diri Šekinku -> Addaru [Intercalary]

The Hebrew calendar is an adaptation of the Standard Mesopotamian Calendar.

At some period during or after the Judean exile in Babylonia in the sixth century BCE, the Judeans adopted the Standard Mesopotamian calendar, as had the Nabateans, the Palmyrans, and other Aramaic-speaking peoples. Judaic writings as preserved in the Bible use the Standard Mesopotamian calendar only in books dating to the post-exilic period. (pp383-384, 2015)

The book gives a table of normalized Akkadian names and their Hebrew counterparts without vowels (except U apparently). This can help you understand where the Sumerian & Akkadian months would fall on our modern Gregorian Calendar, by looking up Gregorian to Hebrew date translation.

I am giving the normalized version of the Hebrew names, from Wikipedia Link, and adding in the book's table transliteration in small parentheses.

🌀Months Akkadian to Hebrew🌀

First is Akkadian -> Second is Hebrew; (subtext transliteration)

Nisannu -> Nisan (nysn)

Ayaru -> Iyar ('yr)

Simānu -> Sivan (sywn)

Du'uzu / Tam(m)uzu -> Tammuz (tmuz)

Abu -> Av ('b)

Ulūlu / Elūlu -> Elul ('lul)

Tašritu -> Tishrei (tšry)

Markašana -> Cheshvan or Marcheshvan (mrḫšvn)

Kissilimu -> Kislev (kslv)

Ṭebētu -> Tevet (ṭbt)

Šabāṭu -> Shevat (šbṭ)

Addaru -> Adar ('dr)

During leap years with an intercalary month, the last months become Adar 1 (Adar Aleph) and Adar II (Adar Bet)

🌾 Using the Akkadian or Sumerian Months🌾

Using the Hebrew Lunisolar Calendar due to its affinity with the Standard Mesopotamian Calendar / Babylonian calendar, we can trace our steps backwards. In 2025, January 1st happens on Tevet 1 in the Hebrew Calendar. Tevet in Akkadian is Ṭebētu which in the Standard Mesopotamian calendar's Sumerian translation is Abbaè.

So January 1st 2025 is Abbaè 1.

This won't help find a year but those seem to be based on the current reigning king at the time anyways.

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

Since no one thought of a holiday prompt... Hannibal and Will coming up with New Year's Resolution related to how fat Hannibal wants to be next year...

Even though he is already pretty big now (how you want to show it, it's completely up to you, but Hannibal is about 300-400 lbs?)

(long, long, long time reader, first time... prompter? But love your work)

Midnight is approaching, creeping softly in over the rounded dark peaks of the Atlantic, when Hannibal begins - in the warm tones of a shared joke and with an almost feline smirk on his face - “Tell me, Will…”

Will looks at him from the other end of the couch. An antique, crafted out of sturdy wood and draped in embossed velvet, it’s becoming something of a tight fit with both of them on it; the hot press of Hannibal’s hip (or the fat that covers it, at least) has had Will half-hard since they sat down.

“Yes?” Will asks, swirling his champagne. The stem of the flute is thin in his fingers. He could snap it with half an ounce more pressure, and that delicacy seems almost obscene when compared to the sheer solidity of Hannibal Lecter.

It has been a lovely evening. They discussed a party, but as much as Hannibal loves hosting, there is something sacred to the satin blackness in the grave of the old year. Another year together, another year free. Another year of indulgence, of excess and gluttony in every area. They worship alone at this altar, as they do so many others.

“How much do you know about the history of New year’s resolutions?”

They had dinner, made together, constructed around three careful kills. Eight courses; twelve for Hannibal, portions doubled. Hannibal read to Will - The Iliad, of course, Will’s head on his lap and his free hand buried in his hair, stroking gently, gorging himself on touch in the same way he does now luxury, and food, and violence. They danced…although not for long. Hannibal is in shockingly excellent health, but even with the steel whipcord muscle that still lies beneath the thick layer of blubber he’s cultivated, 392 pounds (at last check-in, this morning; undoubtedly it’s more now) is an awful lot to move around. Now here they are in the low light of their sitting room, grandfather clock ticking as they watch the new year unearth itself before their very eyes from its chrysalis, buried in the belly of winter.

“I doubt my answer matters,” Will says dryly. “You’re going to tell me anyway.”

Hannibal has taken quite well to the life that they have built together. He lounges on the couch, still graceful but so much more relaxed, the straining coils inside him unwound and given slack. He is comfortable now wherever he is, and it is not just a feigned mask; if it were, he’d remove if with Will, and he does not. He carries the weight well, but he did always have the build for it. The broad shoulders and powerful torso, the height, the strength lying folded in jaw and hand and leg.

“One can trace the tradition’s roots all the way back to the Babylonian festival of Akitu,” Hannibal replies, proving Will right with no hesitation whatsoever. “Their new year began in spring, which only seems logical, doesn’t it? The beginning of the planting season, when the earth finally woke in earnest. When crops were sown, and kings were crowned, and promises were made to repay the debts taken on in past years.” He takes a sip of his own champagne. Will marvels at his tolerance, threshold for drunkenness higher than it ever was before. “The tradition was adopted by the Romans, but it was not until their embrace of the Julian calendar that the beginning of the year shifted to the depths of winter and then, with the spread of Christianity, it came to coincide with the close of Christmas. Knights in the Middle Ages took the opportunity to renew their vows to their lieges, their comrades, and the code of honor by which they all lived.” He tips his head, and smiles. “What vows will you take for the new year, Will? What will you resolve?”

“The same thing I have every year since you came into my life,” Will replies, and refills their glasses. “To survive you.”

Hannibal grins, wolfish teeth on display. His face has not been much affected by his weight gain. The jaw and cheekbones have softened, certainly, but…the points of them are still more than visible, proud and aristocratic.

A predator is at his most dangerous when he is desperate and starving, deprived either by himself or by circumstance. ButWill does not discount the danger of one even so tamed and fattened as Hannibal.

“Given where things are, don’t you think that’s a more appropriate resolution for me to make?” Hannibal asks.

“That’s your resolution, then?” Will drinks champagne. They had it shipped from France. A crate cost more than he used to make in six months. “To survive me?”

“No. I had something else in mind.”

“What?”

Hannibal draws his free hand lasciviously down over his own body. The ripe and overwrought swell of breast and belly, the spread of thigh and hip. All clothed in a perfect and flattering silk blend, red so deep it’s nearly black with a peacock’s sheen, a shirt in arterial claret, a tie Will gave him for his birthday. Riotous paisley in a pattern reminiscent of antlers.

“I’d like to weigh twice as much by next year.”

Despite his expensive tastes and caddisfly cocoon of luxury, Will knows that Hannibal, before he met him, prided himself on self-control so great it was pathological. Tiny portions. Rare kills. Cold showers and early mornings. In his camouflage, he had sewn himself into a skin of austerity so tight that even a deep breath was an indulgence.

Will cut his laces with neat and bloody teeth, and Hannibal’s world now is one defined by excess. He is swollen with it, quite literally.

Will shifts closer. His heart thunders in throat and groin. He knows Hannibal can smell his arousal.

“Will you ever have enough?” Will asks lowly. “Will you ever be satisfied, Hannibal? Or am I doomed to drown in the ocean of your greed?”

“Greed has served me quite well so far,” Hannibal replies calmly. “This life is a shining cathedral built upon the ashes and bones of my old one; and I could never have set the fire without the spark that came from my reaching again and again for that which was denied me.” He leans in, as the clock ticks down. The wide and well-fed expanse of his belly, still gurgling softly with digestion, swells against his waistcoat, gravity dragging it down; they will have to visit their tailor again soon. “And we both know how you love to swim.”

They kiss, and it does feel like a renewal of vows. Hannibal tastes of salt and champagne. They toast, they drink. Distantly, there is a spray of fireworks, barely audible given the distance between their estate and the nearest village.

“Happy New Year, Will.”

“Happy New Year, Hannibal.”

#so glad to have you#hope you send in more prompts#ask#prompt#anon#hannibal nbc#hannigram#kink stuff#weight gain#feeder!will#fat!hannibal#feedee!hannibal#this is really more fluff than kink#sorry

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Easter PSA

If you run across a post about Easter and Ishtar, Babylon, rabbits, and red eggs...DON'T REPOST THAT SUCKER. It's wrong. And it goes around Every Damn Year with people getting suckered in by apparent homonyms that linguistically have nothing to do with each other.

(Yes, the Babylonian New Year Festival--called Akitu--was around the same time as Easter, but the word Easter doesn't owe anything to Ishtar or Akitu. A number of world cultures began the new year on the Spring Equinox. It makes sense when you think about it. Romans gave us the Winter Solstice. The Greeks had new year on the Summer Solstice. Cultures vary.)

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Rogues celebrating Akitu, the Babylonian-Assyrian new years.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

يصادف اليوم رأس السنة في بلاد الرافدين عيد الاكيتو ( Akitu Mesopotamian New Year

عيد أكيتو هو عيد رأس السنة البابلية و الآشورية .

الذي يعتبر اهم الاعياد في العراق القديم ، وأحد أقدم الأعياد والاحتفالات في التاريخ.

حيث يعود تاريخ هذا العيد وبدايته لمنتصف الألفية الثالثة قبل الميلاد في مدينة أور السومرية جنوب العراق.

ففي كل سنة كان سكان بلاد الرافدين يحتفلون بهذا العيد الذي يصادف في التقويم البابلي 1 نيسان كمحصلة للاعتدال الربيعي و زيادة مياه نهر دجلة وبعد اسبوعين من ذلك زيادة مياه نهر الفرات حيث تبدأ كل الاعمال الزراعية في هذا الموعد.

و كان هذا العيد يستقبل من قبل العراقيين القدماء بالفعاليات و الحفلات التن��رية و الغناء والرقص وكذلك النواح و البكاء في بعض طقوسه ، ويستمر الاحتفال بهذا العيد لمدة 12 يوم ( بالتقويم البابلي من 1 نيسان الى 12 نيسان ( حيث يبدأ في اول الاعتدال الربيعي اي في بداية الاعمال الزراعية.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

I traveled to a Festival in Ancient Mesopotamia, this artifact shows them with instruments and celebrating. The Akitu Festival is the earliest document Festival of this time in Sumer. Akitu Festivals were to legitimize the King's ruling! Akitu also included harvesting the food, and celebrating the New Year. They celebrated all kinds of events during these festivals including God's birthday, New Years, Harvest Festivals, and more. A big purpose of these festivals were also to maintain their relationship with God and the King to make sure the kingdom remained perfect and holy. The Gods were seen as the true monarchs of this time, while the King was the physical being who ruled. The way the maintained their King status they had remain good with the Gods, with that being said ways that this was shown was by military victories, big harvest, and great trades. Festivals were either political, religious, or seasonal. These festivals would also be combined in some cases. For example the seasonal festivals happened twice a year and they would harvest the food, the Assyrians would celebrate for twelve days and represent twelve different Gods. Seasonal festivals were part of Akitu, so the purpose was not only to harvest but a political purpose. It is said that Akitu is the oldest observance of a New Years celebration. There was also a celebration of Zagmuk which was the celebration of New Years, this became included with Akitu. Zagmuk was a holiday created not only for New Years but a historical victory Marduks victory over Tiamat. Tiamat created distruction and war, so the God Marduk defeated him and was celebrated, which created Zagmuk. The twelve days of Akitu are mainly to worship Marduk and it is still a practice now. Till this day Assyrians still celebrate Akitu, it is not exactly the same now but it has been a tradition since the early Mesopotamian days.

Mark, J. J. (2023, March 8). Festivals in Ancient Mesopotamia. World History Encyclopedia. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2185/festivals-in-ancient-mesopotamia/

Muhammed, S. (2014, August 31). Assyrian Wall Relief Depicting Musical Instruments. World History Encyclopedia. https://www.worldhistory.org/image/2996/assyrian-wall-relief-depicting-musical-instruments/

1 note

·

View note