#ahhiyawa

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Ekwesh: some scholars see the Ekwesh as possible elements from Ahhiyawa, or even mainland Mycenaean Achaea, while Homer and Odysseus mention an Achaean attack upon the Nile delta.

#history#historyfiles#archaeology#near east#ancient world#ekwesh#ahhiyawa#mycenaeans#achaea#homer#odysseus#nile#bronze age#bronze age collapse

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

how much evidence do we have for making the ahhiyawa-mycenaean connection?

Great question!

The answer is a bit complicated - it’s less a matter of “quantity” and moreso likelihood.

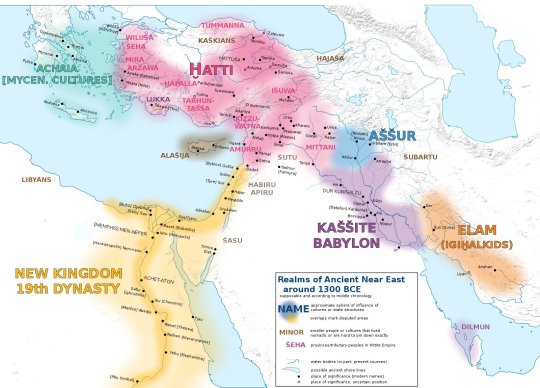

The question of whether or not Hittite references to Ahhiyawa are references to Mycenaean Greek palatial states is still a somewhat ongoing debate, and has been for about a century. For the purposes of this post I’m going to be referring back to two books I’ve read that give a pretty good rundown of the issue - The Ahhiyawa Texts (written by Beckman, Bryce, and Cline - three eminent scholars in studies around the Aegean & the Hittites) and The Cambridge Companion to the Aegean Bronze Age. These two books make use of a lot of previous scholarship that I recommend you check out as well, I’m just using them out of convenience here. In short, it’s a combination of both Hittite textual sources and ample archaeological evidence of Mycenaean interactions with Anatolia at this time.

On the matter of Hittite textual evidence, the connection is made based on linguistic grounds (Emil Forrer, as early as 1924, made a very hesitant suggestion that Ahhiyawa and Achaea sound incredibly similar) and deduction based on the limited geographic evidence provided by Hittite documents mentioning Ahhiyawa. Hawkins (1998) observed that the Hittites describe Ahhiyawa as “across the sea” from Assuwan territories (western Anatolia), a detail that simply cannot work if Ahhiyawa is located in Anatolia. Considering that Ahhiyawa is regularly discussed in conjunction with Hittite activities in the region, there is very little room for Ahhiyawa outside of Mycenaean Greek states (which are - barring the identification with Ahhiyawa - strikingly absent from Hittite sources). One Hittite king - Hattusili III - refers to an unnamed king of Ahhiyawa with the phrase “My Brother, the Great King, My Equal” - which is (in Late Bronze Age correspondence terms) putting this guy on the level of Egypt or Assyria, so it’s clear that the Hittites viewed Ahhiyawa as somewhat significant on the world stage.

The total absence of Mycenaeans from Hittite sources makes even less sense when considering archaeological evidence from the Late Bronze Age. Shipwrecks from this period (most notably, the Uluburun wreck which was most likely going west from Anatolia) point to ongoing trade between the Aegean, Anatolia, Egypt, and the Levant during the Late Bronze Age. Mycenaean pottery is also found frequently in western Anatolia (especially Miletus and Müskebi, which indicate the presence of Mycenaean cultural influence & burial practices). Mycenaean remains in Hittite territory itself are relatively sparse, but Tudhaliya IV also told the ruler of Amurru (another LBA state) to “let no ship of Ahhiyawa go to [Assyria],” and the Ahhiyawa regularly sheltered Anatolians fighting against the Hittites like Uhha-ziti during the reign of Mursili II, so it’s likely that the two regions weren’t exactly on great terms.

Personally, I think that the introduction to The Ahhiyawa Texts sums the issue up pretty well - “If the Mycenaeans are not the Ahhiyawans, then they are never mentioned by the Hittites. This, though, seems unlikely…. otherwise, we would have, on the one hand, an important Late Bronze Age culture not mentioned elsewhere in the Hittite texts (the Mycenaeans) and, on the other hand, an important textually attested Late Bronze Age “state” without archaeological remains (Ahhiyawa).” Alternative theories regarding Ahhiyawa's identification can't really account for this discrepancy, and there's been a gradual lack of dissent to the identification because it's simply the most likely option.

What Ahhiyawa constituted politically speaking, however, is an entirely separate can of worms that I will not touch with a ten-foot pole.

#you could not PAY me to ID an 'ahhiyawan state' on a map. i refuse. im using the word 'state' and 'territory' VERY liberally here#anyways unless someone can come up with a somehow MORE LIKELY option than 'its those guys. that theyre trading with. who have big palace'#achaea is probably gonna stay the main identification for ahhiyawa. probably. despite steiner's best efforts#important context to hittite diplomacy btw: beckman describes them in 'Hittite Diplomatic Texts' as INCREDIBLY paranoid#you were either with them... or you were their enemy... and. well. western anatolian states were Not Often with them#this also kinda requires a standard disclaimer on all hittite texts: theyre trying to conquer arzawa/assuwa. and very vague abt whats there#so like every scholar on hittite activities in the region has to play regional geography 'guess who' based on context clues#it helps MASSIVELY that some king of mira (tarkasnawa) left an inscription going THIS IS MY BORDER GUYS!!!#it didnt get translated until the 90s though because it got er eroded. but we appreciate u tarkasnawa that is indeed ur border#tagamemnon#the ahhiyawa question#late bronze age

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

thesis about the sea peoples you say? may i request an infodump about the sea peoples?

Heya!

So, basically in college (undergraduate) I got really obsessed with the questions around the Collapse of the Aegean Bronze Age, mostly because I wanted to set my big Magnum Opus historical fiction novel in that time, and the deeper I dug into the rabbit hole the more it appeared that no one, absolutely no one, actually knows why the civilizations around the Mediterranean all fell from a state of pretty sophisticated internationally-trading civilizations to literal Dark Ages (all except for Egypt which was substantially weakened and never really recovered), all at once around 1200-1100 BCE.

The Sea Peoples are the names of the only contemporary (Egyptian) account we have that names who might have been responsible if this collapse was due to an invasion. It's a popular theory because a viking-style invasion is a much sexier reason for a civilization to collapse so we all gather around it like moths to flame. But the thing is, there's a lot of contradictory evidence for and against and shading that hypothesis.

Suffice to say, literally no actually knows what happened and almost every answer comes up, "Some combination of these things, probably?"

But what makes the Collapse even more interesting from a modern perspective is that if there was a historical Trojan War (and I think there was) as fictionalized in the Iliad and the Odyssey (and Song of Achilles, for the Tumbrlistas), then it would have taken place within a generation of the entire civilization that launched the Trojan War crumbling to dust.

So like, if you're Telemachus, your dad Odysseus fights in the Trojan War, some even manage to get home, and then like... everything goes to shit. Catastrophically. And doesn't recover for 400 years.

Seriously, they lost the written word, like how to actually write things down and read them and it took 400 years to get it back. That's how fucked shit got during the Collapse of the Bronze Age.

So my thesis was asking: what if these two things were related? What if the Trojan War either led to the Collapse or it was part of the Collapse or it was a result of the Collapse? Because the timeline is so unknown and muddled that it really could be any of those and again, that's if the Trojan War isn't entirely fictional (which I don't think it is, but many academics disagree, it used to be a whole thing up until Schliemann dug it up, and many doubted it was ever a historical event even after that.)

Ok, so at the risk of writing 75 pages on this again, let me just say:

My conclusion (more of a hypothesis proposal ultimately since there are so many gaps in our knowledge) was that the Trojan War took place before the Collapse of the Bronze Age. But, it might have been launched in response to a wider breakdown in trades routes and resources, causing the Greeks to launch the campaign basically as a bid to replenish their own coffers because they were getting squeezed by what they didn't know was the first rumblings of a global domino effect.

Therefore, since taking out Troy didn't solve those larger trends and forces, they all went home and then got slammed by the REAL problem, which was all the people who had been displaced from further away by this rolling drought or invasion or whatever that was disrupting these delicate international trade routes.

But the Greeks might have been part of the Sea Peoples too! Our only record of the Sea Peoples is from the Egyptians in a highly propagandistic text which makes them sound like this big fearsome foe but that might have been because saying, "We slaughtered a bunch of desperate refugees at our border who were looking for shelter," didn't sound as cool. If the Greeks (or Achaeans or Ahhiyawa) got swept up in this slow-rolling collapse/displacement of people, then they absolutely could have been among those refugees who crashed against the shores of Egypt.

A lot of my evidence was based on looking at how Troy was sacked (it was stripped literally down the nails and there was a lot of evidence of a long-term siege, like what we read about in the Iliad) vs. how Mycenae (Agamemnon's city) or Pylos (King Nestor's city) was sacked, where they were burned and stuff was stolen but they weren't stripped, it looks more like a standard looting hit-and-run type thing. Which led me to believe that it was different turmoil that rocked Mycenae and Pylos than what led to the sacking of Troy, despite the fact these things happened within about 20 years of each other. (Helen being a made-up reason for a resource-driven war would only be the oldest trick in the book, as far as propaganda goes, after all.)

But really, the craziest detail I'll leave you with is: we just don't know! And then it gets weirder. Because the Hittites fell at the same time so the Hittites scholars say, "Nah, the Sea Peoples weren't Hittites, they were probably Greeks." And the GREEK scholars say, "It wasn't us, it was probably the Hittites or someone else. " and the EGYPTIAN scholars say, "Yeah it was someone north of Egypt, maybe the Hittites or the Greeks." and the LEVANT scholars say, "It wasn't from the Levant, we know what was going on there, it has to be from somewhere else."

Literally every single possible source of the Sea Peoples has the scholars who specialize in that location saying it's not them and it must be the guy next door.

It's maddening!

And then there's a big ol' gap around Bulgaria and the Black Sea because, oh yeah, the Soviet Union forbade archaeology in those areas to quash any local pride so those places that were behind the Iron Curtain are decades behind on scholarship that would allow them to say, "Oh hey, it was actually us! Yeah, the invaders came from Bulgaria and got pushed down by a famine." or something to that effect.

We also have some histories from the time saying that the Sons of Heracles returned not long after the Trojan War to lay Greece to waste! And it's really evocative and sounds like it fits what we've got of all these burned cities that happened right after Troy fell! Except that's in doubt now too!

The latest theory is that it was climate change that led to a massive drought. You can read about it in the latest and most popular book on the subject, 1177 BCE which I highly recommend because if it had existed when I wrote my thesis, I wouldn't have had to write it.

But I disagree with the conclusion! Or rather, I'm skeptical. Because very decade, the problems of the day have been hypothesized as being the cause of the Collapse. Like, in the 60s, there was a theory that maybe it was internal strife around a labor strike, like the French Revolution. And y'know when there's a world war, they think it's an invasion. And there was a theory that it was 'cuz of an earthquake (I think that one is nonsense, Mediterranean civilizations famously bounce back quickly from earthquakes.) And now that climate change is on our mind, I'm a little weary to see that it's the new theory because it feels way too much like we're just projecting our problems onto this giant question mark.

Was climate an aspect! I think so! I think it might have contributed to the break down in trade routes that made everyone in the Mediterranean really stressed out and hostile and warlike and led to a lot of displacement. I'm not sure if it's the only reason though and I think the book just kinda reiterates everyone else saying, "I think it was this but in the end, we just don't know, and it was probably a lot of things." which we've known for ages so it's just repeating all the same conclusions. *sigh*

... Like I said, I wrote my thesis on this so yeah, I could go on for a while lol.

#ancient history#bronze age#collapse of the bronze age#sea peoples#lots of generalizations here for brevity so don't jump down my throat if you are also familiar with this era plz

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

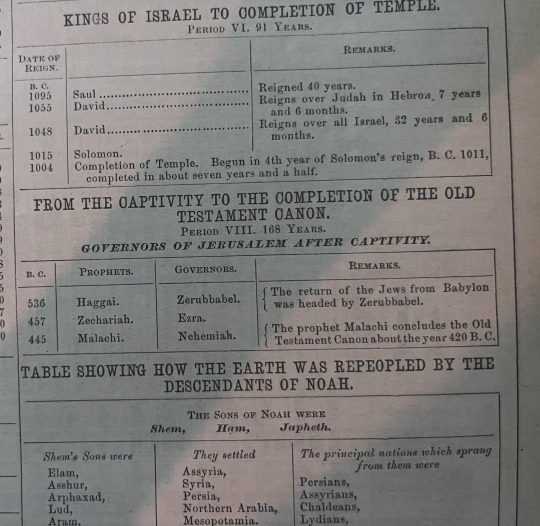

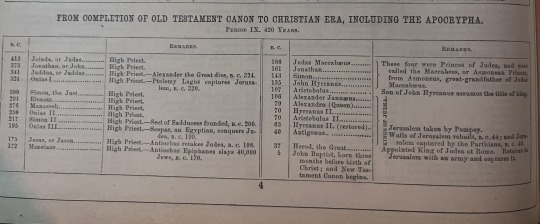

hi anni! I wanted to share some information from my family Bible from my mom’s mom’s side of the family that’s history section only goes up to 1877 when it talks about Russo-Turkish war staring. And the pictures might be horrible.

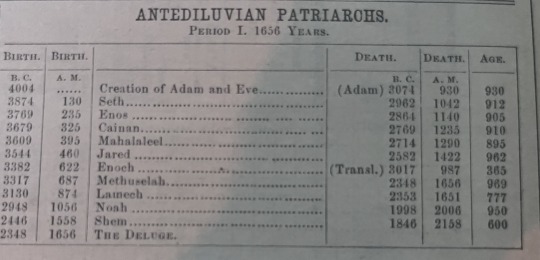

The antediluvian patriarchs apparently lived during the Neolithic era which just happened to be when us humans were first starting to use farming and we started to domesticate dogs, sheep, and cattle. It personally helps with me as I’m a historically accurate nerd when it comes to clothing and just searching up ‘Neolithic era’ clothing rather than ‘caveman’ clothing is much more specific. Enoch in Islam, Idris, was also apparently the first man who learned how to write with a pen.

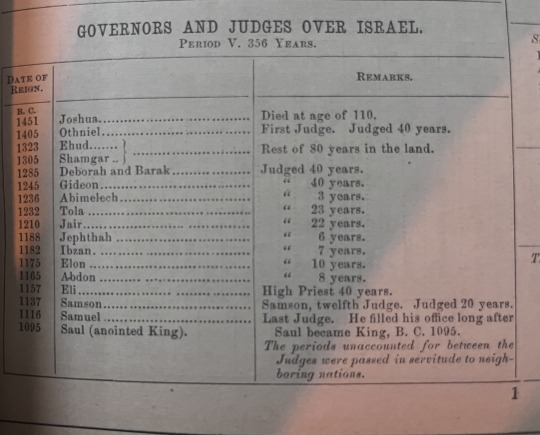

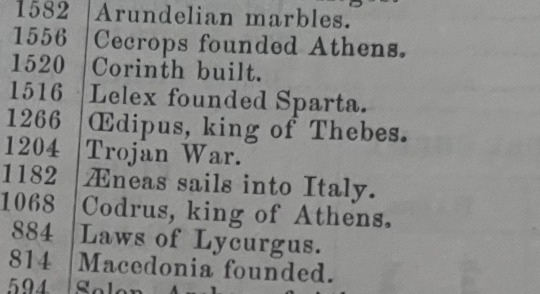

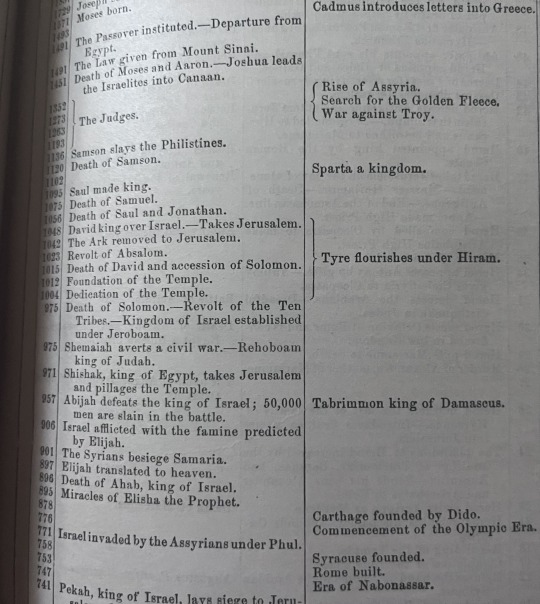

now, onto Greece! The Trojan war happened in around 1204 bc (Eratosthenes of Cyrene says it happened around 1194-1184 bc but judges still happens at the same time) which during that time, the judges Jair to Abdon were alive and the book of judges happening the same time Odysseus, Achilles and Patroclus, and hector were doing their stuff I just funny to me.

Troy was also a vassal of the Hittite empire, a major power in the Bronze Age by Uriah’s people, since 1400 bc. Troy was called Wilusa by the Hittites. Later, in 1240 bc, in a historical note called the Milawata letter mentions a ‘recently disposed pro-Hittite king of Wilusa’ which the king of the Hittite king Tudhailya IV intended to re-install as the king, who was named Walmu, was dethroned due to possible occupation of the raids by the Ahhiyawa people who most believe are homer’s early Mycenaean Greeks. During the Trojan war, the Hittite empire fractured and the Egyptian new kingdom fell into disarray , two of the major powers during the Bronze Age. I personally believe that might be a reason why in the Bible the tribes want a king (for safety and unity reasons) but I don’t know.

and here’s a timeline in the book with the year, the biblical event, and the non-biblical events: ⬇️

There were also two Jonathan’s in the era between the old and New Testament.

One of the advertisements of the book, in the book, was that it had 1500 illustrations and I wanted to share some!

David and Michal during the dancing naked incident and Michal looks like she’s SO ANNOYED and about to hit her head on that stone wall like she’s had enough of it all.

This is in the second book of Samuel illustration, and I think it’s David with Bathsheba and Solomon but idk if it actually is because it didn’t say.

and also here’s part of the Daniel illustration.

that’s all I’ve shared, I hope I got enough right history-wise and again, sorry this was SO long and sorry if you already knew some of their stuff!

This is genuinely some really cool stuff, especially who it shows the timeline and comparing to other non biblical historical events. I seriously need to read more about the Hettites. They were like one of the first major civilizations in the bronze age and I know barley anything about them.

130 notes

·

View notes

Note

Was the Trojan war real or based on true event from another war(s) close to the period

The Iliad it's said to blend myth with historical truth. While we don’t have proof that Achilles or Helen existed (Agamemnon is debated) ,archaeological evidence suggests that a war or series of conflicts did occur near the site of ancient Troy (modern-day Hisarlik in Turkey). Excavations by Heinrich Schliemann and later archaeologists uncovered layers of cities built atop each other, with one layer (Troy VIIa, around 1200 BCE) showing signs of destruction burning and weaponry, around the same time the Mycenaean Greeks were active. This supports the idea that a real conflict may have inspired Homer’s epic, possibly over control of trade routes through the Dardanelles.

Historians also note that during the Late Bronze Age (roughly 1300–1100 BCE), the eastern Mediterranean was full of tension. For example, in the Tawagalawa Letter, a Hittite king complains about hostilities involving Ahhiyawa and a ruler of Wilusa. It's not a record of the Trojan War per se, but it does confirm that Troy (or Wilusa) was a real place, important enough to cause friction between states.

These sources, combined with the archaeological destruction layer, suggest that the myth of the Trojan War might be a dramatized version of real power struggles or wars between Mycenaean Greeks and western Anatolian states. So, while the gods and heroes may be fictional, the war itself probably has roots in real historical events.

32 notes

·

View notes

Note

I remember quite a while back you discussed something about the use of words like Ahhiyawā and Wiluša and used them in your writing. (The hittie language?) I was wondering if you had links to anything of the sorts from your own blog or from the internet.

The Hittite language*, yes! (Also, anon, if I misunderstood what it was you were looking for, please come back ahah.)

I don't really have anything on my blog aside from what posts I've done talking about it in general. Wikipedia is an easy starting point if you just want to pick up some terms, going from the pages on the Hittites and their gods, say, to looking at the countries/areas extant in Anatolia in the Bronze Age and their names. It gives a good idea of what the Trojans might call the surrounding areas themselves, like with calling the Greek/Achaean sphere of influence Ahhiyawa.

Aside from having the Trojan characters call Apollo "Apaliunas" in speech, I haven't mapped any other Greek gods onto the Luwian or Hittite ones. (It hasn't really come up in my fics, but background/worldbuilding-wise I've added a couple Luwian gods to the ones the Trojans worship aside from the Olympian ones.) It doesn't feel right, and really, it's unnecessary. The closest is having Ganymede use one of Tarhunz's epithets for Zeus.

For books (which /cough can be found on the Internet with some searching), I've read a couple of Trevor Bryce's. He does talk about the identification of the site that has been called Troy with Bronze Age Anatolian Wilusa/(and possibly Taruwisa) ; The Trojans and their Neighbours, The Kingdom of the Hittites, and Life and Society in the Hittite World. That last one is especially good if you want to pick up some social/cultural ideas to apply to the Trojans! The first one is also definitely useful for the Troy connection. (Joachim Latacz's Troy and Homer : Towards a Solution of an Old Mystery might be another choice, the first half of his book lays out the development of the knowledge about if myth-Troy should really also be actual Anatolian/Hittite Troy/Wilusa, and he's systematic about it, but doesn't really talk about Hittite society or such.)

(*Language-wise, there's no certain proof what might have been the main/native language of the (real world) Trojans, but a Luwic dialect is probable. Luwian is related to Hittite.)

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

It should also be noted that Troy was most likely an independent multiethnic city state. It was in fact not exactly Hittite and it had both peasants and royalty that could lean to one or the other culture more, including Hittite, Luwian and, you guessed it, Greek. In fact, Paris’ actual name being Alexander might be a reference to the Trojan king Alaksandu (as called in Hittite texts), a name which according to linguists and historians can not be derived linguistically from the ancient Anatolian languages and is believed to be the Ancient Greek name Alexander. Furthermore, Troy’s independence is also indicated in the fact that Troy had conflicts with the Hittite empire too and in the Hittite texts it is written that such conflicts were supported by the Ahhiyawa (the Achaeans - the Greeks), which means that Troy would shift towards one power or another depending on what strategy suited it better at any given time or what the ancestry / culture of the royalty was, and also that Greeks already had some significant influence or activity in the general area. Besides, Ionians were arriving at Anatolia since 1900 BC. Therefore, some Trojans were of Greek ancestry.

In any case, Troy was almost certainly multiethnic and multilingual and Homer could have used that even more to his advantage while making the story relevant to Greek listeners. Everything foreign described in Ancient Greek literature is always considerably Hellenized or Hellenocentric. This in addition to emphasised similarities that Greeks and Trojans might have actually shared (certain deities, cultural practices, names, some level of lingual intelligibility, some ancestry from Greek settlers too) make them look almost indistinguishable in Homer’s texts.

Hey! I've seen all your posts about how Greek gods and characters in mythology should be depicted more like, you know, Greek people, and l just wanted to ask if you think the Trojans would look Greek too :) love your posts btw

Hello! 💙It's important to remember that the large majority of ancient Greeks didn't have a good idea of how people from far regions looked. The further back in history you go, the less they are exposed to other peoples. This is to preface that Greeks' references for foreigners were limited. And if someone was to be very different from the average Greek, they got their own special description in the narrative. (Like the warrior Memnon.)

Of course, Troy/Ilion was very close to Greek areas in terms of latitude. There is almost no difference in geographical latitude, and the people of this area looked like Greeks anyway. It's the distance from the equator that makes people lighter or darker. But when they are the same distance from the equator they evolve similarly in skin tone over thousands of years because they have the same needs for sunlight. Trojans were so close to Greeks that the mixing with other peoples would have been similar. More Eastern peoples might have found their way easier to Ilion than to Greek areas, so there would a difference lie. But due to traveling distances, it wouldn't be very notable, I think, more so if these eastern areas were at the same latitude

But still, the Greeks didn't have much exposure to foreigners, and traveling to Ilion was a feat. From Argos to Ilion it's almost 1.000 kms and it would take 10 months to arrive there by land. Traveling by ship is faster but still not exactly easy, considering the travel to Ilion with the Greek ships was still a daring expedition for their time.

So it's logical to assume that the Greeks drew inspiration from their own people when making these foreign characters. In the text the Trojans are not differentiated in looks and some even have descriptions that show they were fair (whatever our ancients considered fair anyways). They share the customs and pantheon of the Greeks, albeit not being Greeks. Trojans and Greeks understand each other without translators, although their tribes would speak different languages historically. Paris' name is "Alexandros" ffs 😂This shows that the Greeks didn't have a good picture of Trojan (probably Hittite) culture and they didn't wish to delve that deep. It was just a story about a war with "the foreign peoples over there".

Drawing from native culture and appearances when depicting foreigners of other lands has been the go-to for people of old times. It's shown in the text and also in the ancient/medieval art of the native culture. The Persians and the Chinese making tales come to mind but I also imagine that if an ancient Yoruba tribe were to tell a tale of "a very beautiful prince from a faraway northern land" they would depict him as one of their own, and not like a north Egyptian or like an "white" Italian. It comes down to what nations the natives have been exposed the most. If this figure had been established through millennia looking like a native, I'd go by that when depicting them.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

forever going 2 be haunted by mycenaean basket vase

#WHAT THE FUCK WERE THEY DOING!!!!!!!!WHY!!!!!!!!!#I LITERALLY CANT STOP THINKING ABOUT IT. WHY WOULD THEY MAKE THE HANDLES LIKE THAT#GRRRRRRBARKBARKBARK#THIS IS WHY THE HITTITES CROSSED OUT THE KING OF AHHIYAWA'S NAME IN THAT ONE LIST OF GREAT KINGS

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

The first recorded instance of what would today be called paramilitary covert action: In the mid 13th century BC Tawagalawa Letter, Hittite King Hattusili III wrote to the king of Ahhiyawa (Mycenaean Greece) saying he knew he was supporting rebels in Hittite territory.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think - to throw in my thoughts here - the thing for me is that it's a balance between insisting the ruins we now call the site of mythical Troy totally wasn't (mythical) Troy and insisting it totally was. Because I sure am annoyed by the "DID THE TROJAN WAR ~REALLY~ HAPPEN???? and did this site experience a war at the time the Trojan war was said to happen??" sentiment (academic and non) whenever I see it around. Hilarious, but come on now. As we know it (even the most "realistic" of realistic versions) of course it didn't. Archaeological and what little textual history in Hittite sources that have been preserved do not agree, or would only put any sort of east-west/Hittite-Ahhiyawa conflict at Wilusa at much earlier than even the earliest timeline ancient scholars gave us, I believe.

On the other hand, the mythic reality of Greek myth is... very much embedded in their landscape. The springs, rivers, at least a number of the cities - they do and did exist, still now (if in ruins) and in Antiquity. Mythical Athens might not have existed, but the real-life Athens is still the physical "anchor" for the mythical city and the heroes attached to it.

The same goes for the location of Troy. Like, there was an agreement about and belief in where mythical Troy "had" been, and that's (as far as I understand it) is where the ruins of Wilusa is, pretty much.

But also, mythical Troy is of course a mythical construction. Mythical Troy didn't exist, but that doesn't mean the Ancient Greeks didn't imagine a very real physical location for it.

I don't know if it proves or confirms anything for me, personally, that that particular spot in the ancient Troad is where mythical Troy was. But given that very same "embedded in the landscape" quality, it feels... "important"(? something??) to have that spot to relate it to the physical location of Greece itself, etc.

i guess what i fundamentally don't understand about the "was troy real?"/"they found troy!" pop-culture media cycle is exactly WHAT does it prove or corroborate? in WHAT way would a place have been "the real troy"?

130 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi there! I’m fascinated by the Hittites and know a bit about them, but would like to know more. Are there any books you recommend? Thanks!

YES JOIN ME

Some of my favourite books are:

The Kingdom of the Hittites by Trevor Bryce

Life and Society in the Hittite World by Trevor Bryce

basically anything by Trevor Bryce, he’s great

marry me Trevor

1177 BC: The Year Civilisation Collapsed by Eric Cline

The Hittites and their World by Billie Jean Collins

I met Billie Jean Collins actually, she’s great too

well I didn’t exactly meet her, I sat next to her at a conference but it’s basically the same thing right?

The Hittites and their Contemporaries in Asia Minor by J. G. Macqueen (good but a bit outdated)

From Hittite to Homer by Mary Bachvarova

I actually did meet Mary Bachvarova properly and she’s amazing

we talked about tattoos, celiac disease and ancient conspiracy theories

anyway

Hittite Prayers by Itamar Singer

The Ahhiyawa Texts by Gary Beckman, Trevor Bryce and Eric Cline

Letters from the Hittite Kingdom by Harry Hoffner

Lastly, here are a few non-academic resources to get you into the mood:

I the Sun by Janet Morris

The Troy trilogy by David Gemmel

The 2003 documentary The Hittites

I hope that helps feed your interest!

71 notes

·

View notes

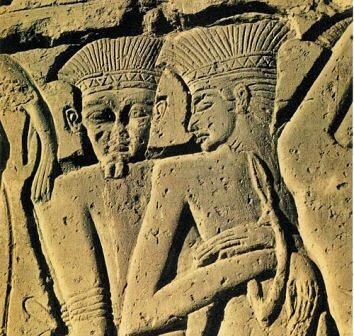

Photo

In the photo are Portraits of captured Philistines, referred to in Egyptian as Peleset, cover the walls of the Medinet Habu temple. One of the most famed people who lived in Canaan were the Philistines, or Palashtu. The Philistines were particularly famed for being enemies with the Israelites, however, they were much more than this. The Philistines themselves were not from Canaan originally. They appear to have come from somewhere west of Canaan, possibly Kaphtor (Crete) which is mentioned as the traditional first home of the Philistines. Disaster in Crete forced the Philistines and several other groups- including the Shekelesh, the Tjeker, the Lukka, the Ekwesh, the Deyen, the Weshesh, the Teresh, and the Sherden- out of their former homeland and across the sea in search of new land. These peoples together were referred to as the Sea Peoples, and it is they who destroyed several Canaanite cities in the north, including Alashiya in Kittim (Cyprus) and Ugarit in northern Canaan. They began to move south into Egypt, where the Philistines are known as attempting to establish colonies in the north. However, the Sea Peoples were driven out of Egypt and defeated by Pharaoh Ramses III. The Sea Peoples continued to search for their home elsewhere. The Sherden ended up in Cyprus and eventually in Sardinia. The Teresh ended up in the Anatolian city of Tarusha, as it was called by the Hittites, and known by the Greeks as Troy. They may also be ancestors of the Etruscans. The Lukka became the Lycians. The Shekelesh became the Sikils of Sicily, the Ekwesh became the Ahhiyawa Greeks. The Philistines though, settled in southern Canaan. The area that became known as Pelest was bordered in the south by desert, in the west by sea, in the north by the Yarqon River, but with no fixed border in the east.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

okay it took longer than 45 minutes because i got detoured into a bunch of other places.

and, because it is long, i'm putting it behind a cut so long post does not get any longer.

terminology i: regarding palaces. new world archaeology says that a palace is both a residence and a seat of political power, and has a wider public role. new world archaeology would hold that what most refer to as the minoan palaces are not palaces, during the major period of the minoan civilization. as to how the ‘monopalatial’ knossos worked during the latest of the late minoan periods (ib is around where i stop, but i can scurry my way through some of the linear b-administrated eras. precisely when that is is up for debate because we don’t know if the tablets we have are from one conflagration event or many), that’s also up for debate.

terminology, ii: regarding megaron. see heinrich schliemann and wilhelm döpfeld deciding that the great halls of the acropoleis of hisarlik/troy/wiluša and tiryns, despite being over a millennia apart in building date, are, in fact: temples! they are then joined by christos tsountas with a similar structure at mycenae, causing döpfeld to go whole-scale capital-r romantic and dubbing them ‘megaron’ instead.

okay! the thing is that minoan and mycenean centres were very different things. minoan ones are more like super luxe community centres and built out from a central gathering place with buildings set around it that evolved into the court-central complexes we know and love well (r i p floors of the 'residential quarter' you were trod upon by too many people), so it's a bunch of different buildings/rooms for administration, production, possibly residential, def. cultic activities stuck together by adding hallways—heterarchical instead of hierarchical. the central court is a unifier, the surroundings are ancillary (which, i know, sounds ridiculous and, honestly, to me: hysterical).

(any notion of hierarchy at knossos can trace back to the influence of james frazer, my mortal enemy, on evans, which resulted in the belief that knossos had some sort of priest-king.)

interestingly enough, evans’s decision to classify these complexes as palace-temples draws on the then-current research of religious centres in anatolia, such as hattuša, where the great temple, as we know it today, was initially thought to be the ‘lower palace’ given its placement below büyükkale hill, where we now know the palace actually was, in a very similar way to how the palace of mycenae is built upon the acropolis.

mycenaean centres were built to enforce hierarchy, and it can be seen in how they direct you to the megaron, to the throne room.

as for homer ‘greeking’ the trojans: he would have been most familiar with level 8, which was a city populated by a majority of greek immigrants by c. 700bce, who reused the citadel’s walls and probably destroyed the rest of the bronze age remains to put a new sanctuary of athena there and then schliemann did what schliemann did best: he fucked it up. he went ‘oh this doesn’t look old enough! can’t be from the bronze age!’ and kept digging, badly, until he ended up in level 2, which was built c. 2550bce.

his bad.

his extreme bad.

we know of contact between ahhiyawa and the hittites, involving wiluša, which is where we get the alaksandu treaty/milawata & al. letters from (c. 1280bce & 1240bce), and there’s definitely a case for the architectural similarities of anatolia and the aegean, along with with techniques and tools used to construct the lion gate of mycenae having their closest parallel in anatolia. much of the masonry at hattuša shows use of the same type of drill that is limited, in the mycenaean world, to the lion gate relief. actual artefacts themselves are far and few between, but we know that there had previously been minoan interest in miletos/millawanda and that interest was later taken over by the mycenaeans, and we can follow the claims of the tawagalawa letter that ahhiyawa was raiding western anatolia for slaves, and can see in linear b tablets names indicated origins in the troad.

now, ‘homeric’ troy wasn’t just hittite. troy was very likely luwian, the term used by the hittites for the people of western anatolia. problem with the luwians: what do we know about them, in the bronze age?

very little.

the layers that are called troy 6h and troy 7a (even though it seems they're actually all continuations of level 6 but popular terminology, alas) seem to be the ones concurrent with the mycenaean era and both of these layers were destroyed, c. 1300bce and 1180bce, respectively. and, despite there being pretty much a century and a half of excavations, only the citadel area has been excavated apart from what looks like some ruins slightly to the south that i don’t know the date of. but they were pretty

the outer terrace structures can provide some insight into how the buildings likely looked: two-storey houses for the most part, pillared megarons, yes. priam’s many-roomed house? no, despite there appearing to be a very sharp division in wealth between those who lived on the upper citadel versus those outside of its walls. i find it interesting that he’s given a courtyard as the central part of his palace rather than the typical mycenaean megaron. even the description of ‘chambers of polished stone’ puts me in mind of monumental minoan building, given the profusion of ashlar masonry within that style.

in fact, the way it’s described has me thinking specifically of the ‘little palace’ of knossos, if you ignore the 'unexplored mansion', which is neither unexplored nor, probably, actually a mansion.

Source-ry

Blackwell, Nicholas G. (2014). “Making the Lion Gate Relief at Mycenae: Tool Marks and Foreign Influence.” American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 118, no. 3, 2014, doi:10.3764/aja.118.3.0451

Bryce, Trevor. The Trojans and Their Neighbours. Taylor & Francis, 2006.

Driessen, Jan. “The Central Court of the Palace at Knossos.” Vol 12: Knossos: Palace, City, State, British School at Athens Studies, 2004, pp. 75–82, www.jstor.org/stable/40960768.

McEnroe, John C. Architecture of Minoan Crete. University of Texas Press, 2010.

Schoep, Ilse. “The Minoan “Palace-Temple” Reconsidered: A Critical Assessment of the Spatial Concentration of Political, Religious and Economic Power in Bronze Age Crete.” Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology, vol. 23, no. 2, 20 Jan. 2011, https://doi.org/10.1558/jmea.v23i2.219.

I'm trying to figure out exactly the planimetry of Troy royal palace (and generally housing system). It doesn't help the various translations sometimes use "house" and sometimes "room" (I guess because in the basic Ancient Greek house there was only one room, so "room" and "house" are indeed the same thing) Anyway, from what Homer says I think there is an inner courtyard with 62 rooms (50 for the sons, 12 for the daughter, on either side of the courtyard). As Homer uses the verb "sleep", they are more bedrooms. Given that the daily activities, included eating, would be communal in the megaron, it's easy to assume the private spaces would be only the ones for sleeping and night activities.

The word used is θαλαμος, meaning specifically "bedroom"

Later, however, both when Aphrodite brings Helen to Paris and when Hector orders Paris back to war, the translation says the "splendid house of Alexandros". The term used is δομος, house, home.

And later

Meaning Paris' house is that, a house, not merely a bedroom, given the mention of a courtyard and a hall (I guess the megaron).

So by my understanding, the sons (at least some) have their own houses, while also having bedrooms in the royal palace (I guess they act as guest rooms). Unless they are the same thing and Homer uses different words based on what the metric requires in that specific verse Please, enlighten me

#long post is long#me: yeah this'll only take a moment. *four hours later* oops. i got stuck in the little palace again.

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

I cannot stop thinking about this letter a Hittite king sent to the king of Ahhiyawa (whoever they thought of as "the" king in this case), complaining to him about the 7000 inhabitants from Lukka (Lycia) that had been taken to Ahhiyawa. (Pre...sumably over a longer period?) Some of them willingly (migration) most of them enslaved in raids/attacks, and just.

I'm imagining Atreus (partially because it's the funniest, partially because if you keep the classical dating of the Trojan War it would most probably be Atreus, but if not, rule of funny) sitting there on his throne like:

Atreus: Well, that's certainly unfortunate. Sucks to be him. >:)))

Unfortunate scribe, ready with clay tablet: My lord Atreus, I can't write that down to be sent to the king of Hattusa!

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hii,

I was wondering if you could tell me (if you know, of course) what the ancient Greeks of the Mycenaean times called themselves.

I was trying to look it up myself for a project but all the info I got was so inconclusive and one article went against the other and I'm honestly so confused.

I really wanted to answer this because I remember we talked about it in A' class in Gymnasio!! (Our History book also wrote a bit about that). We are almost sure, as we have very strong historical elements for speculation.

If you've read the Iliad and Odyssey in English, the Greeks (who came from the Mycenean culture at the time) are called "Achaeans" (Αχαιοί) and the region "Achaea" (Αχαΐα). So, that's probably how they called themselves as well.

The Hettites called the Myceneans "Ahiyawa" (Acheans) and wrote that they were a strong seafaring power. The Egyptians called them "Aqwavasa" or "Eqwesh". You might read the Indoeuropean "aqw-" sound/root hidden somewhere there, which means "water" (see the latin "aqua", the greek "acheron" etc). It is possible that the name "Achaeans" meant "those who come from the sea places". I don't have the time to research more on that but you can do some more reading on that if you want to see if it checks out.

In the Epics other collective names were also used, the most common being Danaans ("Δαναοί" is the Greek term) and Argeans / Argites / Argives / Argeioi. ("Αργείοι" is the Greek term).

Danaans were an earlier, different tribe than Achaeans, and when Achaeans came to the Peloponnese circa 2.000 BCE, they mixed. Danaans came to the region - possible Argos on the mainland the islands - after the "Pelasgoi" (Πελασγοί) the first inhabitants of the region. "Pelasgos" means "one from the open sea" so it's possible the Danaans had mostly gathered in the islands and other places near the sea. Danaans built Argos. But after their mix, Danaans and Achaeans were mostly the same, so the identifications came to be synonyms and used interchangeably by foreigners.

Egyptians called the Danaans "Denyen" and "Tanaju". Moreover, a list of the cities and regions of the Tanaju is also mentioned in this inscription; among the cities listed are Mycenae, Nauplion, Kythera, Messenia, and the Thebaid (region of Thebes).

Argos was a great power at the time and that's why you also see the Argeioi in the ancient texts. Before the Trojan war, they all gathered in Argos and sailed from there. It's possible the city was so powerful back then that it also became representative of the Greeks sometimes in the eyes of foreigners.

For the names of Achaeans these are two prominent sources: 1) Beckman Gary Michael, Cline Eric H., Bryce, R Trevor. (2012). «The Ahhiyawa Texts». Writings from the ancient world / Society of Biblical Literature, (28): 5. ISSN 1570-7008. 2) Jorrit Kelder. Ahhiyawa and the World of the Great Kings. A Re-evaluation of Mycenaean Political Structures, Talanta XLVI, 2012, X-X, σελ. 1.

Of course not all Achaeans lived in Argos, so they didn't have to self-identify as Argeioi. They could remember their Danaan origin and identify with that + the name of their town. Or they were just living in a smaller town and they self-identified with their Achaean origin + the name of their town. And it's possible that many Danaans lived in Argos. I don't recall any ancient texts talking about tensions between Danaans and Achaeans, or any discrimination like "Their family is Danaan and we are Achaeans so our children shouldn't marry." I think they just co-existed and merged without much fuss :P

For the origin story of Danaans in the region, you can read more by seeing the myth of Danaos. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Danaus

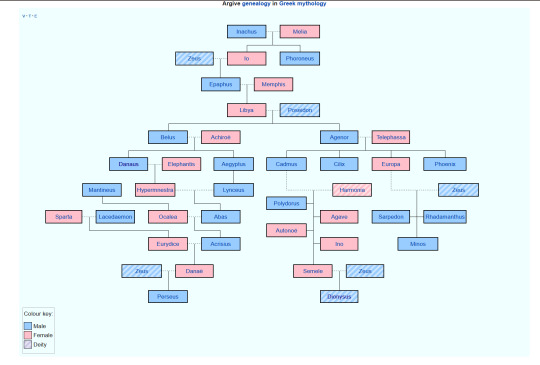

Greek "nations" and genera across the ages, the origins of the Danaans

This entry in wikipedia has very well concentrated all the genealogies and how the Greeks saw the creation of nations and lines across the ages.

**"Ethne" ("Ethnoi") are what I call in English "tribes" for better understanding. ("Ethnos" is singular.) It could also be translated as "ethnicities" (yes "ethnicity" comes from Greek) but in English this shows a bigger difference in cultural backgrounds than a "tribe". The ancient "ethnos" between the Greeks is more akin to the relationship different tribes of the same nation and ethnicity have. In modern times we call them "phylles" lit. "leaves" from different branches of the same tree or "genoi" (you'll know the English word genealogy from Greek). We rarely use the "ethnoi" word today but the ancients saw more differences between them than we see in them today so they kept a wider distinction.

In Greek mythology, the perceived cultural divisions among the Hellenes were represented as legendary lines of descent that identified kinship groups, with each line being derived from an eponymous ancestor. Each of the Greek ethne were said to be named in honor of their respective ancestors: Achaeus of the Achaeans, Danaus of the Danaans, Cadmus of the Cadmeans (the Thebans), Hellen of the Hellenes (not to be confused with Helen of Troy), Aeolus of the Aeolians, Ion of the Ionians, and Dorus of the Dorians.

Cadmus from Phoenicia, Danaus from Egypt, and Pelops from Anatolia each gained a foothold in mainland Greece and were assimilated and Hellenized. Hellen, Graikos, Magnes, and Macedon were sons of Deucalion and Pyrrha, the only people who survived the Great Flood; the ethne were said to have originally been named Graikoi after the elder son but later renamed Hellenes after Hellen who was proved to be the strongest. Sons of Hellen and the nymph Orseis were Dorus, Xuthos, and Aeolus. Sons of Xuthos and Kreousa, daughter of Erechthea, were Ion and Achaeus.

Obviously, one nation cannot come just from one man, and we don't have evidence that Danaans came from Egypt (only some vague linguistic traces because of their name). But it's not impossible. It's very likely that other ethne came from different regions (Egypt, Phoenicia, Anatolia) and slowly mixed with each other to create a more homogenized identity, as people settled more and more in agricultural environments. This early Hellenic identity of "Achaeans" we see for the first time in the Iliad when people from all these kingdoms with similar cultures united under a common cause.

It's important to not call "Danaans" Egyptians, though. At the point we see the peoples called "Danaans", they have developed the early Hellenized culture, distinct from the Egyptian culture of the time. They could potentially have been "Egyptians" a hundred generations back (if we believe their mythological origin story) but when we see them they are interchangeable with Achaeans. They didn't consider themselves Egyptians, and other locals didn't consider them Egyptians (or foreigners) either.

Egyptians don't "claim" the "Danaans" either. I think I should comment on that before any Americans go "Greeks came from Egypt, actually!" In fact, as I mentioned above, Egyptians named them "Denyen" or "Tanaju", like separate peoples from them, and mentioned the Greek cities they lived in.

Achaeans themselves were said to come from the north in 2.000 BCE, Dorians came from the North as well. (We don't know what North™ exactly 😂) Peloponnesians were Dorians but Macedonians were partly Dorians, too.

Achaea (Ἀχαΐα) still exists, btw! I mean... most of our ancient regions and cities still exist but it's nice to see the region kept such an old, really old name! Locator map of Achaia prefecture (Νομός Αχαΐας) in Hellas:

#ethne#ethnoi#tribes#Achaeans#mycenean#trojan war#the iliad#the odyssey#answered#hellenes#hellenismos#ancient greece#academia#classics#history

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

1. Sea people

When Hittite documents quited to mention the Great King of Ahhiyawa(Ahhiya) as the equal status to their own King, already the Mycenaean(that is, Ahhiyawa) civilisation would have fallen into desolation or more precisely been fragmented. Indeed, bit more later when the sea people prevailed to entire Aegean - East Mediterranean coasts, their fragmented political and military statues hardly made them appropriate to overcome the surging wave of immigration. And that very horde of serried immigrants made other bronze age kingdoms, such as Hittite, Ugarit, Egypt Middle kingdom, devastated. For, as one might expect, before the inventing of proper furnace for forging the iron, there would have been a few elites who could have armed as hoplite, which means that the war tactics of Bronze age was not that good for those clogged swarm of humans, for, unlike modern days, in that case, there would be very small difference between army men and peasants. In fact, as I wrote before, at first stage army was merely a bandit - like crowd of youth living around brink of civilisation. So that was happened that those swarm of immigrants defeated Kingdoms.

1 note

·

View note