#ah yes modern literary analysis

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

goodbye Virgo season,

it’s been clarifying

•just Virgo things•

1) It’s interesting to think of Virgo through its essential existencial axis, Pisces; the wonder of reading exists for example, as a result of the forever-intertwined interaction between these two signs. Language itself and reading, understood as the mental translation of symbols to language, it’s a fascinating Mercurial manifestation. It is necessary to go through the diverse phases of learning how to work this translation out into our daily communication habits, before being able to truly connect with literature, which I believe works actively with imagination (ah yes, the Neptunian quality of it 👌🏼). It’s crazy to think (emotion coming from a Pisces ofc), how one of modern’s daily communicative obligations consists on the act of reading, but it’s only when we’ve truly dominated this when we can actually understand the channel it truly is, when it wakes up that little fantasy-moving motor in our heads which works between logics of the real world, and the one which can contradict it. The domination process, is very mucho the Virgo experience. Food for thought. Reading, from a literary point of view, quite literally makes us hallucinate new possible worlds and stories that would often wake this compassionate side of us, or this illusive (and yes delulu) side of us, which kinda’ makes the world go round. Where else would we escape to in order to get out of our daily routine? which usually responds to the Mercurial necessity of just basic reading.

2) Did you know KimK is ruled by her Virgo Jupiter which is exact ☌ her Midheaven at 28°? (this basically explains why she mainly got ridiculously famous bc of her family’s -especially her mom’s- dealings on a private experience of hers), and that she is a Virgo Venus’ ruled Libra? (on her 9th; an international beauty for sure). we can say a lot of things about her, and this astrologically fascinating yet controversial photoshoot, but we can’t say she hasn’t also worked her ass off for the reputation she now holds, the one of a very perfect looking lady.

3) Did you know Virgo rules chess?

4) also pets and small animals :)

5) THE virgo moodboard

6) MJ was a Virgo ofc, a truly fascinating one cause he was a also a Pisces moon and rising, meaning he worked actively through his whole life with this axis. he did have very interesting ideas about purity and a very mysterious and uncertain health condition 🤔

Diane and Wilt are sooo Virgo if you ask me.

7) Virgo rules critics. Michelle Visage is a Virgo sun a moon that’s no exception +she totally resembles Madonna and always looks perfect. It also rules boardgames that imply critical thinking such as chess, puzzles, dominoes, etc.

8) I will not elaborate on this one. It’s clear.

9) ♍︎ rules ants and humbling experiences; the ant meme is Virgo’s biggest, most satirically accurately funny manifestation of its energy if you ask me 🤭

10) Rory Gilmore’s such a Virgo 🤍

The sixth astrological house is related to Virgo since it is the house of health, fitness, systems, analysis, pets, work and organization habits, and of our sense of usefulness and service given.

The house of discipline.

Who would’ve thought the act of reading these mashed-up memes also required the Virgo-Pisces/Mercury-Neptune presence of it all explained in description no.1? Maybe just a Virgo.

0 notes

Text

My Critique of the Phrase "Eat the Rich" and why I wish people would stop saying it; an informal analysis

I haven't posted something like this in a couple years. I find it exhausting because I have so many other more important priorities in my life. But let's go!

Today's Paper: My Critique of the Phrase "Eat the Rich" and why I wish people would stop saying it; an informal analysis

TLDR: Stop promoting violence and use your words and thoughts more strategically.

TLDR #2: I'm struggling middle-class but eating people won't help.

[Introduction] Did you know one of the key focuses of my master's degree was Political/Economical Literary studies? Specifically Marxist Economical Theory and others like Karl Marx.

I intimately studied the passion of these writers and thought leaders. They shaped a lot of my worldview. I admired them.

So before you think I'm a Karl Marx Hater, you're wrong.

2. [Establish Context]

Did you know that the phrase "eat the rich" is believed to have originated from a bigger quote: "When the people shall have nothing more to eat, they will eat the rich", said by philosopher Rousseau during the time of The French Revolution?

While the phrase was originally a critique of the French Nobility, it came to represent the failures of the French Revolution overall that perpetuated poverty in the country. --->"With the monarch bloodily dispatched, the people had found they could eat neither rights nor freedom, and lacked sufficient bread to enjoy either." ( "How "Eat the Rich" Became the Rallying Cry for the Digital Generation". https://www.gq.com/story/eat-the-rich-digital-generation)

In other words, the motto "eat the rich" basically came to represent the failure of its own mission, and one that probably made the situation worse for awhile.

How ironic.

But I always think it's important to put quotes like this in their original context. Because without understanding history, it's easy to get caught up in the "echo chamber" of social media.

3. [Modern Application] Now let's focus on that first half of the sentence: "when the people shall have nothing more to eat."

Really read it.

"When the people have nothing more to eat."

Now, for modern application…

Does the distance between our wealth classes continue to grow? Yes.

Is our nation struggling? Yes.

Are we to the point of the French Revolution, where our population has exceeded food supply and widespread starvation is prevalent? No.

That isn't to say starvation isn't happening in our country. It is.

But it's not the majority. And to be clear, no amount of starvation is good, but I think most of us have access to food.

Good, healthy food? Maybe not.

The food we want? Maybe not.

But food nonetheless.

3b. [Modern Application Continued.]

Economy is incredibly complex.

And while so many people are quick to critique "the rich" and the "Big Industry" behind them, the truth is, our situation could be a lot worse without industry.

If you study the history of major employers or manufacturers, you can quickly discover the positive impacts an employer can have for the community - bringing jobs and wealth and an improved living condition to a community.

And when these companies have closed… Sometimes communities never recover.

Ever.

1,000's suddenly without jobs. without benefits.

Let me emphasize it again: Some of these communities have never recovered after Big Business left.

A strong workforce without an employer is… well, simply put: unemployed.

"But Xavier! Studies show that when a manufacturer leaves an area, it actually doesn't really impact the local economy that much!" ("Big plant closures and local employment": https://academic.oup.com/joeg/article/18/1/163/4079909)

Ah, touché.

Except this example has one problem: it points out that the reason those local economies DO recover is that the laid off employees get jobs at other local competitors in the same industry, or new companies to the same industry emerge to take the absent's place. Meaning it's still relying on industry to survive. And also the study is averaging 264 jobs lost per closure.

"Ok but this reliance on industry only happens in bad countries like the United States."

Me: lol nice try but that's a study in Spain.

Now what happens when a MAJOR employer leaves. Not just 264 jobs. Let's talk big numbers.

I'll use Volkswagen Chattanooga as an example. (not that VW is planning to close - i have no idea the state of the plant - but i know it was a leader in the VW Group so likelihood of that happening is probably very unlikely). I'm only using it as an example because it's a big employer I used to work at. That's it.

But let's imagine VW closes down in Chattanooga. Let's ballpark it and say 5,000 employees.

What would happen if VW would close?

This isn't 264 jobs. It's 5,000.

Suddenly without jobs or benefits or structure.

Not only would our economy take a hit, but so would our health. ("Association Between Automotive Assembly Plant Closures and Opioid Overdose Mortality in the United States" https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6990761/)

That to re-emphasize: economy is COMPLEX.

Think about it: how would a city offset that?

I doubt eating people would help.

And while I'm sure there are plenty of examples of countries where "big industry" aren't major players, that's not the case for the US in my eyes, and it would take a lot more than a midnight snack on a billionaire to change it.

4. [Conclusion: Don't Eat People] I hear this phrase, "eat the rich" often totally misused and out of context. People using it as a rallying cry for change and economic revolution.

But you're using a phrase associated with failure! ugh.

Do we need policies and people in place to make sure our communities are taken care of? Yes!

Do we need DIVERSIFED economies (i.e. making sure a community doesn't rely on two few industries as the foundation for their economy)? Yes!

Do we need fair wages? Yes!

Do we need to eat people?

I sure hope not because that's sounds disgusting and also dumb.

This is all just morning ramblings. But my point is: economy is complex. And boiling it down to "the rich" as the problem is too simple.

And I don't think eating them would help either

5. [Footnote]

People often think individuals who DEFEND "the rich", or "Big Industry" ARE rich.

And let me tell you what: I am definitely not rich. I'll probably never escape my debt.

But eating wealthier people doesn't solve anything for me.

Are rich people too rich? Idk. They have more money than me but I think it's more about taxation and salary caps, etc. And that's a huge economic discussion there as well.

All in all: Stop promoting violence and use your words and thoughts more strategically.

You're capable of positive change and we know our country needs it, but when you use these thoughtless phrases like this you may actually be negatively impacting your ability to implement said changes.

This is big topic. I could probably write an ACTUAL academic paper on it. But I'm lazy and ranting. So there's probably holes in my argument. But whatever. 💁♂️

0 notes

Text

@le-cat-nipp

Yes its not debate, because u are not willing to listen (i know u want to be right, but at the end of the day none of us prob is). U still repeat same argument over and over again, as ethan wasn't considerate for villagers, as he didn't try to safe them. And for lords? Oh boy how wrong u are. Ethan doesn't need to be considerate to them- they kidnapped and dismembered his daughter, yet u expect him to put up with their own issues.

He doesn't need to understand their reasons, neither they want him to, since all they do is tryin to stop him from getting his daughter back. Its not mother miranda doing- they participate in this at their own volition. Also lords didn't have any remorse of killing villagers, yet u called ethan inconsiderate while villagers were the ones, who suffers from lords.

U r talkin about nuances in ones character, yet u only see ethan in bad light basically cause he "didn't understand their pain". I'm not goin to discuss it any longer at this point. So please keep continue in antis or this debacle tag🙂👋

I don't know why I still spend my hard earned latin but fuck it, I like arguing.

hate to say this but right back at ya. I don't want to be right, because there is no right or wrong, because I'm not Capcom, you're not Capcom, neither of our opinions is worth a single corn chip and we're both free to discuss a work of fiction for what it is: a work of fiction. if anything, you keep contradicting yourself because you keep saying that I'm wrong and trying to make characters less evil. abso fucking lutely I am, putting them in perspective is the whole point? don’t know what you’re trying to get at.

I am also very much shining a light at Ethan in a different direction because just as you accuse me of looking at him in a negative light, you can’t seem to see any of the characters in a positive one. looking at the humanity and philosophy and the issues that being human entails is what we’ve been doing with fiction for eons.

I am quite literally telling you that I’m willingly and purposedly digging into Ethan’s character to see the bad parts, not the good ones. the good ones are obvious and not interesting. I like the gory bits.

you’re trying to protect a character you like, I get that. you’re also making an ass out of yourself in the process because you’re not really getting the whole picture. again, have fun with it. I don’t personally care if you think I’m wrong in my analysis. I’ve been having wonderful interactions with people who are bringing me their own views on the issue and it’s being really enriching, which is what I wanted in the first place.

the fact that you seem to think I’m an “anti” just cements the whole thing for me. protect your precious cinammon roll, this isn’t a fan club/hate club situation. it’s literary analysis. I’m not here to diss a fictional character, I’m here to appreciate the thought and detail that went into making him sound human. and I’m extending that same courtesy to all other characters.

I really don’t get why fandom gets so riled up when someone criticizes a character. y’all need better literature teachers. or to go outside and through the shocking discovery that people are not, in fact, archetypes and tropes.

#resident evil village#ethan winters#the ethan winters debacle#I feel like somewhere into the void#I am being watched either by philosophers or authors#and they're scratching their beards and going#ah yes modern literary analysis#truly fascinating hasn't changed a bit

7 notes

·

View notes

Link

Something strange happened to the news over the past four years. The dominant stories all resembled the scripts of bad movies—sequels and reboots. The Kavanaugh hearings were a sequel to the Clarence Thomas hearings, and Russian collusion was rebooted as Ukrainian impeachment. Journalists are supposed to hunt for good scoops, but in January, as the coronavirus spread, they focused on the impeachment reality show instead of a real story.

It’s not just journalists. The so-called second golden era of television was a decade ago, and many of those shows relied on cliff-hangers and gratuitous nudity to hold audience attention. Across TV, movies, and novels it is increasingly difficult to find a compelling story that doesn’t rely on gimmicks. Even foundational stories like liberalism, equality, and meritocracy are failing; the resulting woke phenomenon is the greatest shark jump in history.

Storytelling is central to any civilization, so its sudden failure across society should set off alarm bells. Culture inevitably reflects the selection process that sorts people into the upper class, and today’s insipid stories suggest a profound failure of this sorting mechanism.

…

Culture is larger than pop culture, or even just art. It encompasses class, architecture, cuisine, education, manners, philosophy, politics, religion, and more. T. S. Eliot charted the vastness of this word in his Notes towards the Definition of Culture, and he warned that technocratic rule narrowed our view of culture. Eliot insisted that it’s impossible to easily define such a broad concept, yet smack in the middle of the book he slips in a succinct explanation: “Culture may even be described simply as that which makes life worth living.” This highlights why the increase in “deaths of despair” is such a strong condemnation of our dysfunction. In a fundamental way, our culture only exists to serve a certain class. Eliot predicted this when he critiqued elites selected through education: “Any educational system aiming at a complete adjustment between education and society will tend to restrict education to what will lead to success in the world, and to restrict success in the world to those persons who have been good pupils of the system.”

This professional managerial class has a distinct culture that often sets the tone for all of American culture. It may be possible to separate the professional managerial class from the ruling elite, or plutocracy, but there is no cultural distinction. Any commentary on an entire class will stumble in the way all generalizations stumble, yet this culture is most distinct at the highest tiers, and the fuzzy edges often emulate those on the top. At its broadest, these are college-educated, white-collar workers whose income comes from labor, who are huddled in America’s cities, and who rise to power through existing bureaucracies. Bureaucracies, whether corporate or government, are systems that reward specific traits, and so the culture of this class coalesces towards an archetype: the striving bureaucrat, whose values are defined by the skills needed to maneuver through a bureaucracy. And from the very beginning, the striving bureaucrat succeeds precisely by disregarding good storytelling.

…

Professionals today would never self-identify as bureaucrats. Product managers at Google might have sleeve tattoos or purple hair. They might describe themselves as “creators” or “creatives.” They might characterize their hobbies as entrepreneurial “side hustles.” But their actual day-in, day-out work involves the coordination of various teams and resources across a large organization based on established administrative procedures. That’s a bureaucrat. The entire professional culture is almost an attempt to invert the connotations and expectations of the word—which is what underlies this class’s tension with storytelling. Conformity is draped in the dead symbols of a prior generation’s counterculture.

…

When high school students read novels, they are asked to identify the theme, or moral, of a story. This teaches them to view texts through an instrumental lens. Novelist Robert Olen Butler wrote that we treat artists like idiot savants who “really want to say abstract, theoretical, philosophical things, but somehow they can’t quite make themselves do it.” The purpose of a story becomes the process of translating it into ideas or analysis. This is instrumental reading. F. Scott Fitzgerald spent years meticulously outlining and structuring numerous rewrites of The Great Gatsby, but every year high school students reduce the book to a bumper sticker on the American dream. A story is an experience in and of itself. When you abstract a message, you lose part of that experience. Analysis is not inherently bad; it’s just an ancillary mode that should not define the reader’s disposition.

Propaganda is ubiquitous because we’ve been taught to view it as the final purpose of art. Instrumental reading also causes people to assume overly abstract or obscure works are inherently profound. When the reader’s job is to decode meaning, then the storyteller is judged by the difficulty of that process. It’s a novel about a corn beef sandwich who sings the Book of Malachi. Ah yes, a profound critique of late capitalism. An artist! Overall, instrumental reading teaches striving students to disregard stories. Cut to the chase, and give us the message. Diversity is our strength? Got it. Throw the book out. This reductionist view perhaps makes it difficult for people to see how incoherent the higher education experience has become.

…

“Decadence” sounds incorrect since the word elicits extravagant and glamorous vices, while we have Lizzo—an obese antifertility priestess for affluent women. All our decadence becomes boring, cringe-inducing, and filled with HR-approved jargon. “For my Fulbright, I studied conflict resolution in nonmonogamous throuples.” Campus dynamics may partially explain this phenomenon. Camille Paglia has argued that many of the brightest left-wing thinkers in the 1960s fried their brains with too much LSD, and this created an opportunity for the rise of corporate academics who never participated in the ’60s but used its values to signal status. What if this dropout process repeats every generation?

…

The professional class tells a variety of genre stories about their jobs: TED Talker, “entrepreneur,” “innovator,” “doing well by doing good.” One of the most popular today is corporate feminism. This familiar story is about a young woman who lands a prestigious job in Manhattan, where she guns for the corner office while also fulfilling her trendy Sex and the City dreams. Her day-in, day-out life is blessed by the mothers and grandmothers who fought for equality—with the ghost of Susan B. Anthony lingering Mufasa-like over America’s cubicles. Yet, like other corporate genre stories, girl-boss feminism is a celebration of bureaucratic life, including its hierarchy. Isn’t that weird?

There are few positive literary representations of life in corporate America. The common story holds that bureaucratic life is soul-crushing. At its worst, this indulges in a pedestrian Romanticism where reality is measured against a daydream, and, as Irving Babbitt warned, “in comparison . . . actual life seems a hard and cramping routine.” Drudgery is constitutive of the human condition. Yet even while admitting that toil is inescapable, it is still obvious that most white-collar work today is particularly bleak and meaningless. Office life increasingly resembles a mental factory line. The podcast is just talk radio for white-collar workers, and its popularity is evidence of how mind-numbing work has become for most.

Forty years ago, Christopher Lasch wrote that “modern industry condemns people to jobs that insult their intelligence,” and today employers rub this insult in workers’ faces with a hideously infantilizing work culture that turns the office into a permanent kindergarten classroom. Blue-chip companies reward their employees with balloons, stuffed animals, and gold stars, and an exposé detailing the stringent communication rules of the luxury brand Away Luggage revealed how many start-ups are just “live, laugh, love” sweatshops. This humiliating culture dominates America’s companies because few engage in truly productive or necessary work. Professional genre fiction, such as corporate feminism, is thus often told as a way to cope with the underwhelming reality of working a job that doesn’t contribute anything to the world.

There is another way to tell the story of the young career woman, however. Her commute includes inspiring podcasts about Ugandan entrepreneurs, but also a subway stranger breathing an egg sandwich into her face. Her job title is “Senior Analyst—Global Trends,” but her job is just copying and pasting between spreadsheets for ten hours. Despite all the “doing well by doing good” seminars, the closest thing she knows to a community is spin class, where a hundred similar women, and one intense man in sports goggles, listen to a spaz scream Hallmark card affirmations.

…

The bureaucrat even describes the process of rising through fraudulence as “playing the game.” The book The Organization Man criticized professionals in the 1950s for confusing their own interests with those of their employers, imagining, for example, that moving across the country was good for them simply because they were transferred. “Playing the game” is almost like an overlay on top of this attitude. The idea is that personal ambition puts the bureaucrat in charge. Bureaucrats always feel that they are “in on the game,” and so develop a false sense of certainty about the world, which sorts them into two groups: the cynics and the neurotics. Cynics recognize the nonsense, but think it’s necessary for power. The neurotics, by contrast, are earnest go-getters who confuse the nonsense with actual work. They begin to feel like they’re the only ones faking it and become so insecure they have to binge-watch TED Talks on “imposter syndrome.”

These two dispositions help explain why journalists focus on things like impeachment rather than medical supply chains. One group cynically condescends to American intelligence, while neurotics shriek about the “norms of our democracy.” Both are undergirded by a false certainty about what’s possible. Professional elites vastly overestimate their own intelligence in comparison with the average American, and today there is nothing so common as being an elitist. Meanwhile, public discourse gets dumber and dumber as elitists spend all their time explaining hastily memorized Wikipedia entries to those they deem rubes.

…

The entire phenomenon of the nonconformist bureaucrat can be seen as genre inversion. Everyone today grew up with pop culture stories about evil corporations and corporate America’s soul-sucking culture, and so the “creatives” have fashioned a self-image defined against this genre. These stories have been internalized and inverted by corporate America itself, so now corporate America has mandatory fun events and mandatory displays of creativity.

In other words, past countercultures have been absorbed into corporate America’s conception of itself. David Solomon isn’t your father’s stuffy investment banker. He’s a DJ! And Goldman Sachs isn’t like the stuffy corporations you heard about growing up. They fly a transgender flag outside their headquarters, list sex-change transitions as a benefit on their career site, and refuse to underwrite an IPO if the company is run by white men. This isn’t just posturing. Wokeness is a cult of power that maintains its authority by pretending it’s perpetually marching against authority. As long it does so, its sectaries can avoid acknowledging how they strengthen managerial America’s stranglehold on life by empowering administrators to enforce ever-expanding bureaucratic technicalities.

…

Moreover, it is shocking that no one in the 2020 campaign seems to have reacted to the dramatic change that happened in 2016. Good storytellers are attuned to audience sophistication, and must understand when audiences have grown past their techniques. Everyone has seen hundreds of movies, and read hundreds of books, and so we intuitively understand the shape of a good story. Once audiences can recognize a storytelling technique as a technique, it ceases to function because it draws attention to the artifice. This creates distance between the intended emotion and the audience reaction. For instance, a romantic comedy follows a couple as they fall in love and come together, and so the act two low point will often see the couple breaking up over miscommunication. Audiences recognize this as a technique, and so, even though miscommunication often causes fights, it seems fake.

Similarly, today’s voters are sophisticated enough to recognize the standard political techniques, and so their reactions are no longer easily predictable. Voters intuitively recognize that candidate “debates” are just media events, and prewritten zingers do not help politicians when everyone recognizes them as prewritten. The literary critic Wayne Booth wrote that “the hack is, by definition, the man who asks for responses he cannot himself respect,” and our politicians are always asking us to buy into nonsense that they couldn’t possibly believe. Inane political tropes operate just like inane business jargon and continue because everyone thinks they’re on the inside, and this blinds them to obvious developments in how audiences of voters relate to political tropes. Trump often plays in this neglected space.

The artistic development of the sitcom can be seen as the process of incorporating its own artifice into the story. There is a direct creative lineage from The Dick Van Dyke Show, a sitcom about television comedy writers, to The Office, a show about office workers being filmed for television. Similarly, Trump often succeeds because he incorporates the artifice of political tropes. When Trump points out that the debate audiences are all donors, or that Nancy Pelosi doesn’t actually pray for him, he’s just pointing out what everyone already knows. This makes it difficult for other politicians to “play the game,” because their standard tropes reinforce Trump’s message. If the debates are just media spectacle events for donors, then applause lines work against you. It’s similar to breaking the fourth wall, while the rest of the cast nervously tries to continue with their lines. Trump’s success is evidence that the television era of political theater is ending, because its storytelling formats are dead.

In fact, the (often legitimate) criticism that Trump does not act “presidential” is the same as saying that he’s not acting professional—that he is ignoring the rules of bureaucratic advancement. Could you imagine Trump’s year-end review? “In 2020, we invite Donald to stop sending Outlook reminders that just say ‘get schlonged.’” Trump’s antics are indicative of his different route to power. Forget everything else about him: how would you act if you never had a job outside a company with your name on the building? The world of the professional managerial class doesn’t contain many characters, and so they associate eccentricity with bohemianism or ineptitude. But it’s also reliably found somewhere else.

Small business owners are often loons, wackos, and general nutjobs. Unlike the professional class, their personalities vary because their job isn’t dependent on how others view them. Even when they’re wealthy or successful, they often don’t act “professional.” It requires tremendous grit and courage to own a business. They are perhaps the only people today who embody what Pericles meant when he said that the “secret to freedom is courage.” In the wake of coronavirus, small businesses owners stoically shuttered their stores and faced financial ruin, while politicians with camera-ready personas and ratlike souls tried to increase seasonal worker visas.

…

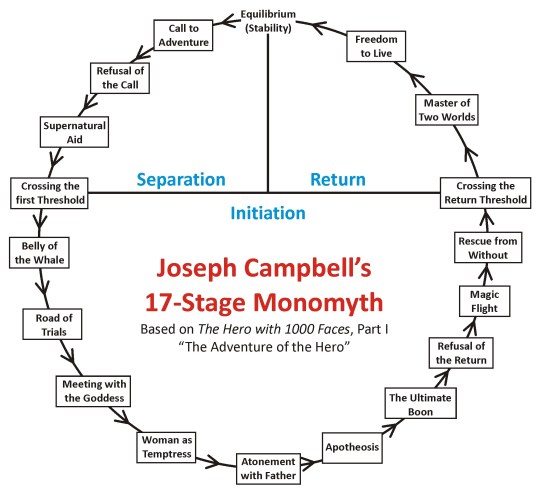

Ever since Star Wars, screenwriters have used Joseph Campbell’s monomyth to measure a successful story, and an essential act one feature is the refusal of adventure. For a moment, the universe opens up and shows the hero an unknown world of possibility, but the hero backs away. For four years, our nation has refused adventure, yet fate cannot be ignored. The coronavirus forces our nation to confront adventure. With eerie precision, this global plague tore down the false stories that veiled our true situation. The experts are incompetent. The institutions told us we were racist for caring about the virus, and then called for arresting paddleboarders in the middle of the ocean. Our business regulations make it difficult to create face masks in a crisis, while rewarding those who outsource the manufacturing of lifesaving drugs to our rival. The new civic religion of wokeness is a dangerous antihuman cult that distorts priorities. Even our Hollywood stars turn out to be ugly without makeup.

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

In your opinion, who does Cu Chulainn like more between Laeg and Ferdiad? And do you think Cu Chulainn is capable of choosing between them if forced to? Or does he just like them equally?

i don’t think you can really directly compare them, to be honest… he has such a different relationship with the both of them that it’s not an either/or situation. there are some texts, particularly later/early modern ones, that seem to be casting láeg slightly in the role of ‘fer diad replacement’, but that’s not how he comes across to me in the bulk of the material

if we have a look at them both individually… [this is super long so i’m putting it below a cut to save people’s dashboards. also yes i just did like 45 mins’ worth of literary analysis for a tumblr ask. why am i like this]

fer diad was cú chulainn’s companion / close friend / lover when he was very young, while training in alba with scáthach. they were extremely close, having trained and fought together over a substantial period of time, often in seemingly isolated situations. the text indicates that they shared a bed (which, obviously, doesn’t necessarily indicate that anything homoerotic is going on, but does lend itself to that interpretation).

they haven’t seen each other in several years.

they meet again now for what seems like the first time since their youth, and everything has changed. they’re on opposite sides of a war, both torn by their loyalties to their ruler and to their family (both have a familial connection to the person they’re fighting for). it’s a conflict between childhood (foster brother) and adult (family, land) loyalties, and the adult ones win out. despite this, they briefly recapture their childhood intimacy in between fighting each other, but only for the first two days, before even that proves too difficult to maintain in the face of the violence they’re forced to do one another.

(for the record, the way i personally elect to read their relationship is that when they were young they were extremely intimate and had a vaguely romantic relationship, but i don’t tend to read that as sexual because they are literal children. now, granted, this is somewhat anachronistic and inaccurate because, you know, this is cú chulainn we’re talking about, he supposedly sleeps with scáthach at that age even though he’s like six, but the texts which emphasise his closeness to fer diad – and his youth – don’t mention that aspect, so it has the feeling of a divergent tradition in which he’s a bit older. anyway point is i read them as romantic while they’re in training but then they meet again in the táin and cú chulainn is seventeen and fer diad is a bit older and it’s like. oh damn. oh. oh this is not a feeling i should be having about the guy i’m about to fight but. damn. and then they make out. that part’s sort of canon.)

so that’s his relationship with fer diad. it’s… messy and devastating and that’s where its power lies; it’s got this long period of separation in the middle during which they both grow up considerably which really shifts how they interact with each other, and then this catastrophic reunion under the worst of circumstances.

(bearing in mind a lot of this is extrapolated from how they talk to each other in flashbacks, because we don’t ever properly see their youth together)

láeg is cú chulainn’s closest friend throughout his life. it’s unclear where or when they met. one version of compert con culainn has them raised together, both nursed by láeg’s mother, which would mean láeg is probably not more than a year or so older than cú chulainn (since he’s still nursing when cú chulainn is born). other versions don’t mention this, and it’s not clear at what point they become close friends, but it happened at some point. it’s not even entirely clear what province láeg is from, although i think based on that one version of compert con culainn an argument could be made for leinster, which would explain why he’s not hit by the ulaid’s curse (unless charioteers don’t count).

láeg is at cú chulainn’s side throughout the táin. they’re alone there together for literally months. he’s cú chulainn’s servant, technically, but their relationship has some bizarre power dynamics going on (in the book of leinster MS, cú chulainn repeatedly calls him ‘a mo phopa’, which is a very… respectful/deferential way to refer to an older guy, not really what you’d expect. eDIL claims the term is occasionally used as a familiar way to address a social inferior, but honestly? i’m pretty sure they just put that in to explain cú chulainn using it for láeg. i’ve talked about this a few times on this blog, discussing other ways to interpret it, like ‘bro’, which would lean into the interpretation of láeg as cú chulainn’s surrogate older brother figure. alternatively he calls him ‘daddy’ which. you know. is cursed but also uncomfortably valid.)

they play fidchell together, which is like the medieval irish version of chess, and we learn that láeg wins about 50% of the time. given cú chulainn’s association with lug, who supposedly invented fidchell, this suggests that láeg is not only his equal, but also knows him very, very well – well enough to predict his moves.

láeg is with cú chulainn until he dies; he dies because he’s hit by a spear that was aimed at cú chulainn, who dies later in the same story. he’s in the majority of texts that cú chulainn is in (with a few notable exceptions that i’m working on identifying). he goes to the otherworld on cú chulainn’s behalf, at one point, which is pretty brave of him. cú chulainn trusts him and is closer to him than virtually anybody else. i don’t think we ever see him put that much faith in another person.

can you compare them? i don’t know. based on what he says in the táin, láeg was there when cú chulainn and fer diad were training together. he knows them both, and he knows how close they were. he tries to convince cú chulainn not to fight fer diad, because he knows it’ll destroy him. he’s the one who picks the grieving cú chulainn up and convinces him to stay alive afterwards. (at one point he has to literally tie cú chulainn to a bed to make sure he stays still long enough to heal from his wounds. láeg is the long-suffering mumfriend.)

it’s also worth mentioning here that in the stowe manuscript (and only the stowe MS), fer diad’s charioteer is named as idh mac riangabra, láeg’s brother. this name comes up elsewhere as being conall cernach’s charioteer, and since this is only in stowe i tend not to pay much attention to it, but it seems relevant here, because láeg and idh act as interesting foils for cú chulainn and fer diad. they end up fighting each other in their attempts to protect their masters – more specifically, they fight over the gae bolga, which láeg is attempting to pass to cú chulainn; idh is trying to stop him, in order to protect fer diad. in other words, we have two brothers whose loyalty to their masters is greater than their loyalty to each other, causing them to fight… which is more or less the exact position cú chulainn and fer diad have ended up in.

(it’s not just loyalty that sets them against each other; it’s also shame, and honour, and the fact that medb has straight-up threatened to kill fer diad if he doesn’t, or at least, make him fight a whole group of other warriors, which amounts to the same thing. personally i think if he can hold cú chulainn off for three days and cú chulainn can fight like 30 people at once, fer diad is definitely in with a chance of surviving whatever medb throws at him, but maybe he’s better in one-on-one situations. certainly he doesn’t seem to think he can live through it, and in the stowe manuscript he explicitly laments that “medb will kill me with a host” if he doesn’t fight for her, so…)

that interpretation of the charioteers would place láeg’s bond with cú chulainn as the strongest of this mess of interpersonal relationships, i guess, but i think there are a lot of factors going on and none of them are really free to act on what they want – they’re doing what’s required of them (by society, by their rulers, whatever), no matter the personal cost. i don’t think you can really look at the táin and be like “ah yes, i know what cú chulainn wants, personally” because… do we? do we really? i think he wants a nap. láeg almost certainly does.

so, in the end, i’m not sure it comes down to a question of ‘liking’. if forced to choose, i think cú chulainn’s loyalty is to láeg. láeg’s loyalty is certainly to cú chulainn, despite knowing fer diad and understanding what he means to cú chulainn. they are… incredibly close, in a way that seems unusual for a warrior-charioteer pairing given what we see with others, but makes perfect sense if you read it that they grew up together from infancy, and i don’t think we ever see that bond being broken between them.

also, like, he never brutally murdered láeg, which is for sure a point in his favour, given that he… very much did eviscerate fer diad. that cannot be overlooked. that’s kind of an important point.

having said that, as a general rule, i don’t think he wants to make out with láeg. i can occasionally be persuaded to think otherwise, but i generally don’t read their relationship that way, whereas he canonically kisses fer diad.

(kissing in medieval irish lit is actually pretty rare? at some point i really want to do more research into any other scenarios in which there is kissing of any kind, because it doesn’t come up that much, and i feel like exploring those would allow for a more solid interpretation of comrac fir diad as either ‘nothing to see here, just regular homosocial intimacy in a warrior society’ or ‘huh, this is unusual. guess it must be gay’. reading it in conjunction with, say, medieval french lit would suggest the former, but in the context of medieval irish lit specifically… idk, i’m leaning towards the latter, but i need to do more research before i can state that categorically.)

tl;dr i think he has a very different relationship with them both that can’t directly be compared, but if forced to choose, would probably pick láeg.

did i need 1800 words to say that? probably not but here they are anyway

#laeg mac riangabra#cu chulainn#cu chulainn/laeg#fer diad#tain bo cuailnge#medieval irish#tc does academia#answered#rionaofblue#cu chulainn/fer diad#irish mythology

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Myriad Misadventures - Chapter 50

The Myriad Misadventures of a Midgardian Queen-In-Training - Chapter 50

AO3 | Previous | Next

Word Count: 1471

Pairing: Loki/Reader

Rating: T

Myriad Misadventures - Chapter 50

And so it comes to pass that you do return to the palace, after all. And it seems that people have taken notice. On Good Evening, America, they do a little rewind to some of the earlier moments filmed of the remaining contestants, and you’re surprised to see this included:

“Now, I’m not going to lie, Ashley—I’d almost forgotten about Little Miss (Y/N). As the only teen left in the competition, I didn’t think she was even old enough to be homecoming queen, let alone queen of an entire planet, but looking back, her interactions with the crowd at the train station really blew me away, let me tell you.” Footage plays of you with that little girl, and you’re shocked by how much younger you look on camera—was that really just a few years ago?—bending down to sign her notebook. “Isn’t that sweet?”

********************************************

You’d be lying if you said you didn’t fear things would be a bit awkward after your last conversation. But if anything, the opposite seems to have happened. Things are normal. Perhaps a bit too normal.

Like on your second day back, when he asks you for advice on a date with Irina. You must have stared at him for a full five seconds before shutting your jaw and thinking enough to give him a proper answer (horse-riding, of course).

You knew he considered you a friend, but this? Really?

And then the day after that, he invites you into his office for tea. And you find yourself wondering if this is maybe a date of your own, until you end up talking again about a date for one of the other girls. You wonder: is he trying to make you jealous? Or is he really just that oblivious?

Which option is worse?

There is a third option you’ve considered, which is that he’s giving you room to consider...well, consider the capacity in which you want to stay in the competition. Which, to be fair, is very sweet.

But that means he’s probably expecting you to make a decision. Soon.

So, again: which option is worse?

********************************************

On top of that, the return to the palace has done nothing to improve your friendships with the other girls. If anything, it just seems like it’s made them more conscious of the competitive element of the competition. Rosa’s outfits are more carefully coordinated than ever, and she’s perfected her already razor-sharp conversation skills. Rhea’s previously motherly air has taken on an edge that makes her seem even more formidable than before. Irina hasn’t changed much, actually—she keeps her head down and rides her horses and seems normal. But she’s here, and that alone is enough of a statement that she, like the others, doesn’t plan on going anywhere before the competition is done.

And you? You are determined to work harder than ever. Because if you’re going to choose to be here, you’re going to do this right.

(What is “this?” And how exactly do you plan to do it “right?” Unclear. But it’s good to have a sense of purpose all the same).

Etiquette classes continue; and of course you attend. But you find yourself drawn more than ever to the library. You try to study the basics of a foreign language or two—for when you’re no longer under the protection of a language spell. With some difficulty, you begin to reteach yourself the math and science you’ve missed or forgotten since high school. And you find that, if you mention an interest in a particular topic, a slew of modern books on the subject will appear on your usual corner table, neatly stacked, the next day. Computer science. Literary analysis. Ornithology, ichthyology, other “ologies” you’ve never heard of— you do your best to dabble in a bit of everything. In case, you know, you want to go to college. Once all this is through.

Honestly, it feels as though most things you do these days are on the assumption that you’ll be gone from the palace eventually. Definitely sooner, rather than later.

********************************************

“So the hair comb with the pearls for Rhea…”

He purses his lips, and walks around the board, frowning slightly. “You’re certain it won’t be overkill?”

It’s become a habit, this. Meeting in his office. Advising him on speeches, dates, and everything in between. And it’s easy, really. Light. Simple. Friends.

“I think love can take many forms. Friendship is one of them,” you always remember, and always you push the thought back. Sure, friendship is a form of love. He’s right. You know that.

It’s just not the form of love you’d hoped for.

“Overkill?” You look at him incredulously. “How so?”

“You yourself have told me numerous times that you found the initial provisions of jewelry and clothing to be excessive.”

You roll your eyes at that. “It’s a palace. Everything is excessive. Besides, this is practical: she never leaves her room without her hair done up. She’ll get a ton of use out of it.”

He holds up his hands in defeat. “I defer to the wisdom of my superior.”

“Superior? I like the sound of that.” You launch yourself off the front of the desk to walk around and sit in the head chair behind it. “So tell me, inferior, what else is on the agenda for tonight?”

He looks at the board again. It’s like an old-fashioned blackboard, with gift ideas for the three girls scrawled across it in both your handwriting and his (and smudgy in places, where you wrestled with the chalk). “The anniversary ball is in a little over a month, Lady Amara has been sent the options for the decoration schema, the tokens for Ladies Rhea, Rosa, and Irina have been selected…”

You push out your lower lip in a show of faux-disappointment. “What, and no gift for me?”

Instead of the chuckle you’re expecting, a small smile rises to his mouth. “As a matter of fact…”

Wait, what?

You’d been joking about the gift. And even if he did have a gift for you, you’d expect for him to present it to you at the anniversary ball alongside the other girls. Instead, you see him reach into his pocket and produce a small, slim rectangular box. He presents it to you.

“You didn’t have to,” you say, feeling suddenly guilty. He laughs at your tone.

“You might want to open it before feeling too bad,” he teases. You hesitate. “Go on.”

You slip the lid off the box and lift off a layer of pale green tissue paper to reveal… “Oh my God.”

“Do you like it?”

“You’re joking.”

“I’m afraid not.”

“It’s incredible.” You lift the fish fork out of the box and turn it over in your hand, regarding it with no small amount of amusement. “Did you make this out of solid gold or something? It’s so heavy. No, wait.” You point the fork at him, preventing him from speaking another word. “Don’t answer that. I don’t want to know.”

His cheeks are slightly pink, and his smile, though small, clearly reaches his eyes. “You like it?”

You bring the gift to your chest and tilt your head at him. “I love it. Love it. You should have given it to me before dinner. I would have loved to see the look on Lady Amara’s face.”

He tsks playfully. “I should have known you’d use my gift for evil.”

“Oh, hush. I’m sure, if anything, she’d just be pleased to see how dedicated I’ve become to my studies.” A yawn escapes, and you clap a hand rather ungracefully over your gaping mouth. He smirks. “Shut up,” you warn him.

He shrugs, lifting his hands (though the smirk stays exactly the same). “Not a word.”

“I suppose that’s my cue. See you at breakfast?” He nods. You head towards the door, when you hear him clear his throat behind you.

“Although…”

You turn to face him. “Although?”

“Well. Apparently there is supposed to be some sort of astronomical event happening tonight.” He jerks his head in the direction of the window. “A starfall.”

“What, like a meteor shower?”

“Is that the Midgardian term? Yes, I assume so.”

“Ah.” You pause, waiting for him to continue. “And?”

“And. Well, I wondered if you wouldn’t join me in the garden? Just for a short while, perhaps. Unless you wish to return to your room, which would be understandable, as well—”

“Yes.” You realize, with a burst of embarrassment, that you’re grinning. “A walk in the gardens sounds lovely.”

He stops rambling, then, and rewards you with a shy smile of his own. “Well, then. Shall we?”

He extends an elbow, just as he did that night on the beach. And you take it. "Okay."

You're both still smiling like idiots as you walk out the door.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Call of Cthulhu: an over long analysis

In trying to give any video game a fair review, one faces difficulties, because games try to be and to do such a varying range of things. I think this is especially true of Cyanide’s Call of Cthulhu. There are so many metrics by which one could measure the game. Is it engaging? Is it scary? Does it do what it does well;? Is it well made? Is it true to its Lovecraft source material? Is it true to its roleplaying game source material? Is it worth the price? If you are short of time, and I would not blame you if you were, then very quickly: yes; no; yes; depends what you mean but no; sort of; yeah and that depends but probably not. If you are not short on time, then let me explain myself (in very great detail) by taking these points in turn. It is difficult to appraise the game without spoilers, but I will warn you when they are coming. If you do not want them, skip to the next heading.

Is Call of Cthulhu engaging?

Yes. Not the most engaging game, mind, but its story, characters and general sense of intrigue carry the game. There are technical problems with the writing that I will deal with below, but those are the video game equivalents of bad grammar and spelling errors (of which, while we are on the subject, I noticed a bit in the subtitles and item descriptions). Despite the animation problems, also mentioned below, the characters are well fleshed out both through direct speech and context. The graphics are nothing sensational, but are definitely good enough to create a world you want to explore. One of my favourite things, though, is that the game does not treat you like an idiot, nor does it leave you behind. My problem with the few investigation-based games I have played before is that they are determined to leave no man behind, so they bash you around the head with everything that they have lying around. Call of Cthulhu does not do this. Cut-scenes and mandatory conversations make sure you know what is going on even if you are not paying attention to anything else that is around you, but if you are looking at the details in the world, even the ones that are not in any way highlighted by the big buttons that appear over everything that you can interact with, then you can start to piece together why things are happening, as opposed to just finding out that they are happening. Intelligence, time and exploration are rewarded with details, but none are essential for understanding the gist of the story. It is difficult to say much more without spoilers, so here are some SPOILERS:

While Officer Bradley was clearly the best character, standing out from most modern video game characters you see today by being wonderfully human, but not in a broken, flawed way, I want to prove my point about good characters by pointing to Charles Hawkins. While this character is never explicitly explained, we know he has been in on everything since the beginning. He is literally a wife-beating monster and definitely a villain of the piece. But he is also conflicted and caring. He genuinely wants what is best for Sarah, even if that means abusing her. He is a bad, angry man, but he is trying to do right. And the beauty is that the game never actually tells you this. It shows you. No one really ever says anything about Charles’s character, but reading into what he says and watching what he does really gives you a feel for his character. Which is impressive for a character with such little screen time.

Is Call of Cthulhu scary?

No. I do not play horror games so I am not the person to ask really. Or maybe I am the perfect person to ask. Either way, for what it is worth, I was not scared by this game. I hate being chased and a couple of sequences made me tense up in my chair, but I would not take that as a massive indication of anything. The same fear of being chased is what made me stop playing Mirror’s Edge and that game is very far from scary. In the game’s defense, however, jump scares are cheap and I hate them and this game seems to aswell. I counted exactly two and one of them was mostly just a creepy musical trill and the other one was so obviously coming it did not even startle me. So Kudos there.

Does Call of Cthulhu do what it does well?

Yes. What I mean by this is, if you boil the game down to what it actually is, it does that well. What that means, is that it is a very good walking simulator. If that is not what you want, do not play this game. This is a walking sim with some very light RPG elements and a few sections where, undoubtedly, someone higher up the chain came in and said “we need a stealth section!” or “we need a combat section!” or “we need a horror section!” or “we need an action section!” and the developers obliged, put in one instance of each and moved on. These sections, except maybe the fun but very basic stealth section, are by far the weakest parts of the game (oh my, that combat section!). The exceptions are the many puzzles, which, like the plot in general, do not treat you like an idiot. Except for one part of one, which honestly feels like the developers made a mistake (what is supposed to be the clue for where to look for the answer instead just straight up gives you the answer, despite the fact that all the stuff for actually reasoning out the answer is right there in the game!).

I only have one problem with the walking simulator nature of the game. There are a few sections which are clearly only there to pad out time. Most of the game is a pretty tight linear tour through the story, but occasionally you are given an adventure game style ‘puzzle’ that just boils down to, “walk around this area you have already walked around for ages until you find the thing that you have to poke to make the story progress”. Anyone who has played the game will know what I mean by ‘the bust bit’. And there is another section which might work as a horror piece, maybe, but just seemed to me to be “run around this same small area 5 or 6 times till we arbitrarily let you out”. ‘Lamps’ is the clue word for that one, if you’re curious as to what I mean. But these are nit-picks. Generally the game is an excellent walking simulator.

Is Call of Cthulhu well made?

That depends on what you mean. Games are hugely multifaceted, but what often differentiates a good game from a poor one is the ability of its developers to work to its strengths. It would be an unfair criticism of Indie darling Limbo to say that it had bad facial animations. It definitely did, but this is not a problem because the characters effectively have no faces. This seems like a facile point, but I think it is important to remember that Cyanide, the developers of Call of Cthulhu, have previously been known for the Styx games, a few Games Workshop titles, a buttload of cycling games and little else. Call of Cthulhu is not triple-A, but it’s not Indie either. The game, at least visually and narratively though, tries to do everything a triple-A title would attempt to do, as opposed to the usual Indie approach of making at least one aspect in some way minimalist. This is not an excuse, merely something to keep in mind as I say that the animation is some of the worst I have seen in games for a very long time. It’s not quite as funny as Mass Effect Andromeda’s, there is not quite enough going on for it to be quite as bizarrely broken. Dialogue lines would come out of characters whose mouths were shut, arms would constantly drift around like they had slightly confused minds of their own and I hope the ‘facial expressions’ were enjoying their trip to the uncanny valley.

The writing was a bit all over the place as well. Writing, mind, not story or character construction. There is a reasonable amount of choice in the game, but an annoyingly large number of the lines of dialogue do not seem to match up with the choices you make. In the first main scene, you can go straight into a conversation with someone and mention in one conversation branch that you know that a character is a big deal on Darkwater island, and then immediately choose another conversation option where you reveal you have never even heard of Darkwater island before. In a subsequent scene, a man told me he would meet me somewhere later, but then, when I got there, my character had several lines questioning why the man was there. There are numerous moments like this and it really takes you out of the experience every time it happens. A similar issue is present whenever you enter an enclosed space and your vision starts distorting. I only knew that this was a representation of the main character’s claustrophobia because the developers mentioned it in press releases. I did not notice any mention of it in the actual game.

A bit more nit-picky, but there are a few times when the game simply does not tell you something that would be useful to know. The most egregious of these is when they give you something which has limited uses but do not tell you either that it has limited uses or how many uses are left until you have used them all up. It is never a particularly large problem, but it would have been nice to know.

Still, looking at the game as a technical work, I must say that the graphics are nice. The art style has a Dishonored feel to it, which I personally have lots of time for. It is not quite as stylised, but the game is generally very pretty, which is a good thing too since you will spend a lot of time shoving your camera into every corner of it.

Is Call of Cthulhu true to its Lovecraftian source material?

Ah, the fun question. The answer really depends on how much of a deep dive you want to do. But before I jump in, it is important to note that the developers explicitly said their game was based on the table-top RPG, rather than Lovecraft’s stories. What follows, then, is a piece of literary critique (read: w**k) and not necessarily a criticism of the game. It will also be absolutely riddled with SPOILERS:

Call of Cthulhu gets a lot right about the common conception of the Lovecraftian aesthetic: the green tinge that permeates everything gives it a distinctly Cthulhu-y vibe, the rural town is a common motif of Lovecraft’s (the game is very Shadow Over Insmouth here) and Cthulhu as an entity is almost used well. As I said at the top, SPOILERS! Cthulhu actually shows up, for about one second, in one of the game’s four endings and is presented as an unstoppable, maddening, world-ending force. This is doing Cthulhu right. There is no fighting Cthulhu: once he has been awoken from his fhtagn, the world will crumble around him. The only hope one has is to prevent that from happening, so it is appropriate that, if it is allowed to happen, the game gives you no chance to resist. The game also takes a good approach to sanity and curiosity. Fuller is the character who most explores the concept of curiosity and it is shown to warp and twist him as it opens his mind to new possibilities. This fear of curiosity is at the heart of Lovecraft’s writings. The game also plays with sanity, another of Lovecraft’s main themes, although most of the mechanical implications of that are better discussed in relation to the Call of Cthulhu table-top RPG.

However, there is one thing that the game gets seriously wrong about Lovecraft. In those moments when the game is scary, the story itself is not one of cosmic horror. Much horror is about holding a mirror up to humanity. It is about showing and exploring our darker sides. Werewolves explore our animal nature, vampires (at least traditionally) were an exploration of sexuality, serial killers explore human psychopathy, zombies represent rampant consumerism. The monster, at the end of the day, is us. This is not the goal of cosmic horror. Lovecraft is not writing stories about people. His horror is metaphysical. “The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all of its contents” is how he begins his story The Call of Cthulhu and this one sentence, I think, underpins all of his work. His protagonists go mad not because they saw something scary, they go mad because they saw something they cannot explain. Their very understanding of reality is thrown out of whack and they are shown that the safe, pedestrian, societal lives they thought they were living were facades: the ignorance that our subconscious chooses for us to protect us from realisations about the universe and our tiny, utterly insignificant part in it. His entities are often not even evil, they are simply so alien and disinterested that we matter as much to them as ants matter to us. This is why Lovecraft was so revolutionary, he moved away from the traditionally biblical kind of horror where the monsters are manifestations of our own sins and turned instead to the secular world of science for his horrors. “The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little”, he continues in Call of Cthulhu, “but someday the piecing together of previously disassociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the light into the peace and safety of a new dark age”. I say again, Lovecraft is not telling stories about people. He is telling stories about the universe and our inability to understand or cope with it. The truth that science will one day unlock, Lovecraft seems to be suggesting, is that we do not matter at all. This is cosmic horror. But Call of Cthulhu (the video game, that is) seems to miss this. Pierce’s sanity (or insanity) progression comes the closest. I say more on this mechanic below, but the final choice that Pierce must make is the most Lovecraftian moment of the game.

There are four endings to the game, one default and three others unlocked through story actions, which is a system I like. On a very quick side note, I also really like how there is a save point just before the end, allowing you to go back instantly and replay the endings you did not choose, but only if you unlocked them (I unlocked three of the four endings on my first play-through). Suicide and accepting the ritual both present “go mad from the revelation” endings, each with a different but totally appropriate flavour of madness, while the ‘it’s over’ ending represents a flight back into a dark age, Pierce sticking fingers in his ears and yelling “la la la it’s all a dream!” I also like here that you have to unlock all but the ritual ending. I was annoyed with this ending until I found this out. The game does not really give you any reason to complete the ritual. The Leviathan and the cult have all clearly been bad the whole way through the game, there is not ever any good reason for Pierce to surrender at the last moment and perform the ritual. Having it as the default, though, makes this lack of motivation slightly more excusable, as it represents Pierce simply surrendering to what he has been told is his destiny, as opposed to having worked for the will to fight back in some way. The fourth ending, the counter ritual, is by far the poorest, which is a shame because it could so easily have been fixed. You know that Drake is planning something, but Pierce, or at least my Pierce, was never told exactly what that was. My Pierce would not logically even have known that there was a counter ritual, never mind how to do it and certainly never mind what it actually does (a point that I am still completely in the dark about). This is something, as far as I can tell, that the game never explains, even if you do choose this option. Just a little bit of exposition, probably delivered by Drake, would have cleared this all up.

But I digress. Call of Cthulhu is essentially a game about people. It is about a group of people who are more or less tricked by some powerful alien being into doing its bidding. And as I said above, it does this well. But in being about people and their struggles, it fails to focus on what Lovecraft himself actually focuses on. Now, a quick disclaimer: I do not know for a fact that Lovecraft was a racist and viewed minorities as ‘less human’ than white people (although there is evidence for this in his work), but I am going to assume this is the case, at least in some way, for what I am going to say. I think it is telling that most of the cultists in Lovecraft’s work are minorities, because this distances even his human villains from the (I think) exclusively white protagonists of his stories. This separation between the human and the alien is completely ignored in the sequences in which Pierce is visited by the Leviathan in prison. The fact that the Leviathan would take humanoid form and use human manipulation tactics to get Pierce to do what it wants is totally non-Lovecraftian. Where is the horror at our utter inconsequentiality here? Cthulhu is scary because it does not care about us, we matter so little there would be zero point in it or any of its ... associates (for want of a better word) attempting to use tactics to manipulate human kind. In The Call of Cthullhu (the story now, not the game), Cthullhu pretty much tells people to come and they just do. No need to take human form, no need to use psychological methods. Lovecraftian horrors use us like the dumb insects that, compared to them, we are.

Further the visions that haunt Pierce are visions of people, mostly, and the awful things that they do to each other. He questions his senses, but he never really questions his position in the universe or what it would actually mean if all the things that he is seeing were true. Lovecraft’s protagonists usually do believe what they see and this is what drives them mad, while Pierce is driven mad by questions about whether or not to believe what he sees. The biggest crime though, the moment that really made me feel that the developers had missed the point, is in the after-credits half of the ritual ending. Here we see the cultists all engaged in a murderous brawl, screaming with delirious madness as they punch and kick and bite each other while, presumably, Cthulhu gets on with the important job of destroying the world just off camera. But this is the wrong kind of madness. Sure, everyone would go mad as their understanding of reality snapped at the vastness and alien-ness (alienitude? alienosity?) of Cthulhu, but for all of them to just go kill-crazy? It doesn’t make sense. That does not seem to be the madness that comes of having your entire knowledge of reality shattered. It feels more like a madness that makes a flashy ending to a video game.

Is Call of Cthulhu true to its roleplaying game source material?

Yes, broadly. Firstly, I am not a CoC (which is what I’ll call the rolepaying Call of Cthulhu, because this is getting stupidly confusing) expert. I have played and run a few games, but it is not my main game. That being said, I think I know enough to say that Call of Cthulhu does a good job of translating CoC into a video game. Its plot is a little more big-leagues (bigly) and showy than your average CoC game, but that is fine. It’s the same thing that happens when a film is made from a TV series. And in this regard, Call of Cthulhu is hardly a huge offender. This might just be me, but I really like stories that know how to reign in their scale and Call of Cthulhu does a pretty good job of this. With the exception of one particular sub-plot (which is by no means overblown just a little elbowed in (the whole painting sub arc, btw)), everything is pretty well contained and not much is thrown in to escalate things to stupid levels as the game progresses.

Call of Cthulhu continues the well-practiced trend of CoC games of being incredibly linear, but while this is an actual problem for roleplaying games, where the only limitation is imagination, in a video game, which is fenced in by budget and deadline constraints, this linearity is not so much of a problem.

An area where Call of Cthulhu differs from CoC is in its use of skills. The skill list for 6th edition CoC (which is the edition I know, so don’t pester me about 7th ed) is over 50 skills long. Call of Cthulhu, on the other hand, has 7 skills. This means you never have those horrible moments where you absolutely NEED a successful library-use roll or else-you-will-all die-in-the-next-encounter-because-you-did-not-know-the-monster-is-weak-to-salt-but-you-put-all-your-points-into-Fast-Talk-so-I-guess-you-are-all-just-going-to-die-and-no-I-am-not-still-bitter. This, I feel, is an improvement. It could be argued that it reduces the scope for roleplaying, but with the limited conversation options and the actually quite well written and characterised Pierce, you are never going to be totally in control anyway. Call of Cthulhu is also paced very much like a CoC game as well, with slow, social information gathering at the beginning, ramping up to more action/horror moments later. This does make some of the skills more useless later on in the game, but this is not a major problem and a difficult one to avoid (and certainly one that CoC games usually fail to avoid). Also like CoC, there is, I think, a clearly right thing to do at character creation, but while in CoC it is because some skills (I’m looking at you, operate heavy machinery) are simply pointless, in Call of Cthulhu character gen is the only time you can use experience points to level up Occultism and Medicine, something you are definitely going to want to do and something the game does not do a good job of telling you.

CoC’s main selling point, as a system, is its sanity mechanic, something that Cyanide obviously spent a great deal of time looking at when making Call of Cthulhu. I have heard that some people did not think it was used well, but I have to disagree. Sadly though, to explain why I have to make liberal use of SPOILERS!

In CoC, sanity is effectively your character’s long-term health bar. Your sanity level sticks around from adventure to adventure with very little you can do to raise it if it falls. It is, in many ways, your character’s expiration date. It goes down whenever you see something Cthulhoid, but there is a random element to it. Clearly, this would not work for Call of Cthulhu, not in the same way anyway. If Call of Cthulhu were a CoC game, it would take at most three or four sessions, and that is not really fast enough for a character to melt completely into a gibbering puddle of insanity. So Call of Cthulhu does something very different and I think it does it very well.

At the beginning of the game, you have some control over your sanity being reduced. The most clear example of this is when you have the option of whether or not to read the Malleus Monstorum. But as the game continues, you have less and less choice over whether you get to see sanity-breaking stuff or not. It basically just happens to you. This means that really, your loss of sanity is almost 100% controlled by the game’s story. Therefore the moment that you break mechanically is also the moment that weird stuff starts happening, by necessity, in the story. Pierce starts to have visions, some of them obviously fake, some of them much more plausibly real, and because his sanity has broken we know that we are in a situation where we should be questioning everything, as opposed to earlier in the game when the lines were much more clear cut. This is a co-opting of mechanics by story, which I have not really seen before in a game. The game gives you something that appears to be in your control but then slowly and subtly takes it back. You could see this as a reduction in player autonomy, because it really is, but I think this fits very well with the themes of destiny and inevitability in the story. It also produces an organic way to show the deteriorating mental state of Pierce without it being exposition-y. If we had felt, right from the beginning, that the sanity bar had nothing to do with our own choices, the moment when Pierce breaks would have felt contrived. But by giving us that illusion of choice we are engaged with the progression of that sanity bar in a way that we would not be otherwise and when it finally shifts from stable to psychotic, we do not see this as a simple narrative move, we see this as an organic part of the story and the choices we made in it, even if really it is not. I also love how the sanity manifests itself. It is subtly done and I think interesting debates could be had about what is real and what is not (I have strong feelings about when the last time we really see Colden is, for example). A brilliant example of this is how we shoot Fuller in what is obviously a dream-scape and then come back to what we think is reality and find we have shot him there too. But this, itself, is also shown to be an illusion when, in one of the ending sequences, we hear him talking to a nurse. It is all very Inception-y and I really like it. It was a nice subversion of expectations, as I was expecting the sanity meter, as a player influenced mechanic, to be able to affect only aesthetic things and maybe minor story elements. I noticed this exactly once (a painting had blood spatters on it which disappeared when I approached), but the way the game takes control of the mechanic and allows it to have serious narrative impact, while a removal of player autonomy, was very refreshing.

Is Call of Cthulhu worth the price?

At time of writing, Call of Cthulhu is selling for £40. It is not worth that. You can go and pick up Divinity Original Sin 2, a game that is basically empirically perfect, for £10 less than that and get at the very least ten times as much play time out of it. Where the price point of Call of Cthulhu should be for you is something only you can decide. £15 seems like a more reasonable price point to me. What I look for is usually a strong enjoyment/hour ratio as opposed to a good hour/money ratio, and Call of Cthulhu has a very good enjoyment/hour ratio, but this is certainly helped by its short length. At the end of the day, I would say that whatever you would be willing to pay for two engaging, thoughtful, just below Hollywood tier films is probably the right price for Call of Cthulhu. Especially since the game has basically no replay value. In many ways it is very average, but if you have a thing for walking simulators or Lovecraftian worlds, then this game is a must buy for you. But maybe wait until the price has dropped.

#Call of Cthulhu#Cthulhu#Lovecraft#Game Review#Essay#Cosmic horror#Literary analysis#Roleplay#HashtagsHaveNoSpaces

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maiden, Mother, Crone: “The Battle for Mewni” and the triple goddess -- the agony of birth, the trial of motherhood, and the hard price of power.

Ah, at last!

Here we are at the other side of Star vs. the Forces of Evil's "The Battle for Mewni." Was it everything I thought it would be? Yes, I think so; it was even more than that. There's a lot to unpack in these episodes, and I plan to take my time in doing so. (But not too much time.)

This post will discuss Star, Moon, and Eclipsa and the connection they all have to a mythological concept called the triple goddess, with each of these characters representing one of the three archetypical aspects of the goddess -- Maiden, Mother, Crone. I will discuss the nature of each aspect, while touching upon the comparisons and contrasts we are meant to perceive by way of these analogues, and I will explain what I think the implications are of the triple goddess's presence.

This will be a long post.

First, Some Acknowledgements

This post owes a nod to my good friend @malthuswibble, whose post on reddit regarding possible symbolism and mythology behind the cauldron is probably more precise and insightful than anything I will ever post, and to reddit user celestialwolf157, who wrote an extensive analysis on Queen Moon which illustrates her shortcomings as a leader. My analysis will touch on some of the same ideas from these two essays, and I would strongly encourage you to not only read these posts but follow their writers as well.